Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Several systemic therapies are now approved for first- and second-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Although the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines offer physicians evidence-based recommendations for therapy, there are few real-world studies to help inform the utilization of these agents in clinical practice.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) describe the patterns of use associated with systemic therapies for mRCC among Humana members in the United States diagnosed with mRCC, (b) assess consistency with the NCCN guidelines for treatment, and (c) to describe the initial first-line therapy regimen by prescriber specialty and site of care.

METHODS:

This was a retrospective study using Humana’s claims database of commercially insured patients and patients insured by the Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plan. The study period was from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2013. Patients with mRCC were identified by ICD-9-CM codes 189.0/189.1 and 196.xx to 199.xx; all patients were between 18 and 89 years of age, had received systemic therapy for their disease, and were followed up for 180 days. Outcome measures included choice of initial systemic therapy, starting and ending doses, first-line treatment persistence and compliance, and choice of second-line therapy. Persistence was measured using time to discontinuation of first-line therapy and proportion of days covered (PDC; the ratio of [total days of drug available minus days of supply of last prescription] to [last prescription date minus first prescription date]). Compliance was measured using the medication possession ratio (MPR; the ratio of [total days supply minus days supply of last prescription] to [last prescription date minus first prescription date]).

RESULTS:

A total of 649 patients met all inclusion criteria; 109 were insured by commercial plans and 540 were insured by Medicare. The mean ± SD age of patients was 68.6 ± 9.4 years, and 68.6% were male; Medicare patients were older than commercial patients (71.7 ± 7.4 vs. 56.6 ± 9.1 years, respectively; P < 0.001). The most common comorbidities among the patient population were hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and heart disease. The majority of patients (68.6%) received an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) as their first line of therapy: 43.9% received sunitinib, 14.0% received sorafenib, 10.0% received pazopanib, and 0.6% received axitinib. Mean ± SD time to discontinuation of first-line TKI treatment was 169.1 ± 29.5 days with sunitinib, 160.3 ± 41.1 days with pazopanib, and 160.1 ± 41.4 days with sorafenib. Other first-line therapies included inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (19.7%) and the antivascular endothelial growth factor agent bevacizumab (9.4%). Among patients receiving mTOR inhibitors, 14.8% were started on temsirolimus and 4.9% were started on everolimus. The median starting and ending doses were the same for each drug except for sunitinib. Mean ± SD times to discontinuation of temsirolimus, everolimus, and bevacizumab were 171.8 ± 26.2, 137.0 ± 62.2, and 150.8 ± 56.0 days, respectively. Persistence on first-line regimen as measured by PDC was high (PDC ≥ 80%) for 89% of oral therapies and 77% of injectable therapies; first-line compliance was high (MPR ≥ 80%) for 77% of oral therapies and 68% of injectables. Among patients who received second-line therapy, the most common regimen was everolimus (29.2%), followed by bevacizumab (19.8%), temsirolimus (15.6%), and sunitinib (13.6%). Specialty codes obtained from the database provider identified internal medicine specialists and oncologists as the most common prescribers of TKIs and mTOR inhibitors.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patterns of use were similar for each of the prescribed systemic treatments for mRCC, and the majority of patients were highly persistent and compliant with first-line therapies. Time to treatment discontinuation was slightly longer with oral agents compared with injectable drugs.

What is already known about this subject

Several systemic therapies are now approved for the first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and are included in the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Kidney Cancer Guidelines.

Previous studies of patterns of use in patients with mRCC have focused on a limited number of drugs, primarily sunitinib and sorafenib.

What this study adds

This investigation helps fill a gap in the literature by examining patterns of use across all of the currently available therapies.

Our results indicate that patterns of treatment for mRCC were similar for each recommended or approved systemic therapy and that most patients were persistent and compliant.

Oral therapies were associated with modestly higher rates of treatment persistence and may be preferred over injectable agents.

Based on recent estimates, kidney cancer accounts for approximately 4% of all cancer diagnoses in the United States.1 This estimate includes more than 61,000 diagnosed cases and more than 14,000 expected kidney cancer deaths.1 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) makes up approximately 90% of all kidney cancers, and as a result of its often asymptomatic presentation, many patients have advanced or metastatic RCC (mRCC) at the time of diagnosis, which is associated with poor outcomes and short median survival.1-3

Our understanding of the biology of RCC has advanced in the last decade, and this has led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of several targeted therapies, which have replaced cytokine-based therapies as the first line of treatment in mRCC.4,5 The approved targeted therapies include inhibitors of angiogenesis such as the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib; the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor bevacizumab; and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus.

The large number of first-line and subsequent options for therapy has led to a fragmented treatment landscape. For first-line treatment of clear cell carcinoma, which accounts for up to 80% of RCC,6 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline recommendations include interleukin-2, sunitinib, bevacizumab plus interferon alfa, pazopanib, temsirolimus, and axitinib, although the latter is not FDA approved for first-line treatment.7 Recommendations for second-line treatment include all of the foregoing therapies as well as everolimus, which is only approved in the second-line setting. All of the approved systemic agents are associated with adverse events that may influence their use, and differences in patterns of use may be, in part, a consequence of the tolerability of the drugs.

In light of the growing number of first- and second-line options for treatment of mRCC, it is important to understand the real-world patterns of use of these agents, including treatment persistence and compliance. Although prior research into the treatment of mRCC assessed the real-world outcomes of individual drugs, no studies to date have reported a detailed description of patterns of use across the entire therapeutic landscape. In this paper, we describe the real-world patterns of use of first- and second-line therapies for mRCC among patients in the Humana claims database.

Methods

Study Design and Objectives

This descriptive, retrospective, observational, claims-based study of patterns of use in mRCC was based on an analysis of administrative data in the Humana claims database between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2013 (study period), which exclusively included patients who initiated systemic therapy for their disease during the observation period of July 1, 2007, to June 30, 2013. The index date was the date of the first medical claim for a systemic therapy for mRCC (following a diagnosis of mRCC); claims data were analyzed from 180 days before to 180 days after the index date because this was thought to be a suitable period based on previous studies conducted with similar designs.8,9

The primary objective of the study was to describe the patterns of treatment associated with systemic therapies for mRCC (as recommended by NCCN guidelines), including persistence and compliance with first-line and, where applicable, second-line therapies. A secondary objective was to describe the initial first-line therapy regimen by prescriber specialty and site of care.

Eligibility

Eligible patients were fully insured commercial or Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plan members and were 18 to 89 years of age as of the index date. Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plans are offered through commercial insurance companies, which are compensated by the U.S. federal government to provide benefits to enrollees. All patients had at least 2 claims with a primary diagnosis of RCC (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 189.0, malignant neoplasm of kidney, except pelvis; and/or 189.1, malignant neoplasm of renal pelvis) at least 30 days apart and occurring between July 1, 2007, and June 30, 2013. In addition, all patients had evidence of advanced or metastatic disease (ICD-9-CM 196.xx to 199.xx, secondary malignant neoplasm); at least 1 primary RCC diagnosis code must have been recorded before or on the same date as the claim with the diagnosis of metastatic disease. After diagnosis of mRCC, all patients must have initiated a systemic therapy and were continuously enrolled during the 180-day pre-index period through the 180-day post-index period. Patients who were Administrative Services Only members, residents of Puerto Rico, and plan members who had specifically opted out of participation in research studies were excluded.

Data Sources

The data sources for this study included enrollment, medical claims, and pharmacy claims from the Humana database. Enrollment data included member demographics and dates of coverage. Medical claims data included utilization, costs, outpatient visits, tests and procedures, emergency department visits, and hospital inpatient stays; the information recorded included ICD-9-CM codes, Current Procedural Terminology for tests and procedures, and J-codes for medications that require administration at a physician’s office. Pharmacy claims data included details of each prescription fill: specific medication by National Drug Code and Generic Product Identifier codes, fill date, quantity dispensed, and days supply. The study used a deidentified dataset, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by an internal Humana privacy board and by an independent institutional review board.

Outcomes

Outcomes assessed for the primary objective were initial systemic therapy for mRCC, starting and ending dose of initial therapy, time to initial dose change, switch in therapy (second-line therapy), time to switch in therapy, and persistence and compliance with first-line therapy. Persistence was defined as the time (days) between first paid claim to discontinuation; date of discontinuation was defined as the last day of supply for the last prescription filled.10 Patients without an observed discontinuation or switch in therapy were censored as of the last day of the 180-day post-index period; the censored time was calculated as the number of days between the index date and the date of censoring, which was always 180 days. Persistence was also calculated in terms of the proportion of days covered (PDC), defined as the ratio of number of days with drug on hand to the number of days in the time interval. A PDC value ≥ 80% was considered to be high persistence. Compliance was measured using the medication possession ratio (MPR), which represents the proportion of time during treatment that the patient was theoretically in possession of the medication, and is calculated as the number of days of medication supplied within the refill interval divided by the number of days in the refill interval. At least 2 paid claims were necessary to calculate MPR, and a gap in therapy of > 30 days between the last day of medication supplied by the previous paid prescription and the next fill date of the same medication was taken as therapy discontinuation. Any paid claims for the initial therapy following a switch in therapy were not included in the calculation of MPR. High compliance was defined as an MPR ≥ 80%.

Low income was determined by a database indicator that recorded whether a member was a participant in a low-income subsidy plan from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The categorization of medical specialty was reported from the claim record to the health plan in a variety of configurations, which were then mapped to standard categories for reporting in the study.

Patient characteristics assessed were age, sex, line of business within Humana’s membership (commercial or Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plan insurance), geographic location, Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index,11 RxRisk-V comorbidity score,12,13 low-income subsidy status, race and ethnicity, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, site of care, and prescriber specialty. The presence of individual comorbidities was determined from ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes from the 180-day continuous enrollment pre-index period.

Analyses

Continuous variables were described by means, standard deviation, median, and range. Categorical variables were described by patient counts and percentages. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate time to first-line treatment discontinuation.14 All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 and SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Population and Characteristics

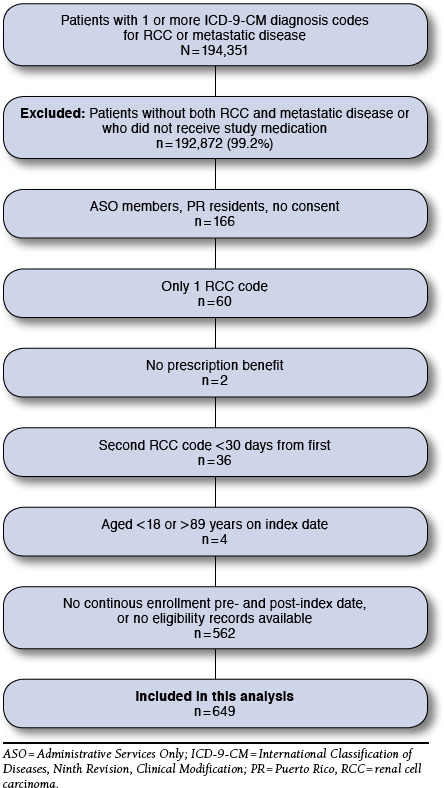

Among the patients in the Humana database with 1 or more primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for RCC and metastatic disease during the observation period between July 1, 2007, and June 30, 2013, a total of 649 patients met all of the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). The majority of eligible patients were male (68.6%) and were Medicare members (83.2%; Table 1). Patients in the Medicare group had higher comorbidity indices than those in the commercial group. Medicare patients were predominantly white, but the majority of values for race and ethnicity were missing. The proportion of the Medicare group with low income or dual eligibility (Medicare and Medicaid) was 6.7% and 6.9%, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Flowchart

TABLE 1.

Patient Baseline Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Commercial (n = 109) | Medicare (n = 540) | Total (N = 649) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 56.6 ± 9.1 | 71.1 ± 7.4 | 68.8 ± 9.4 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 74 (67.9) | 371 (68.7) | 445 (68.6) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | |||

| Midwest | 31 (28.4) | 140 (25.9) | 171 (26.3) |

| Northeast | 0 | 13 (2.4) | 13 (2.0) |

| South | 73 (67.0) | 336 (62.2) | 409 (63.0) |

| West | 5 (4.6) | 48 (8.9) | 53 (8.2) |

| Data not reported | 0 | 3 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | NA | 257 (47.6) | 257 (39.6) |

| Black | 17 (3.2) | 17 (2.6) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (1.3) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Asian | 3 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | |

| Other | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | |

| Missing | 253 (46.9) | 362 (55.8) | |

| Low income, n (%) | NA | 36 (6.7) | 36 (5.5) |

| Dual eligibility, n (%) | NA | 37 (6.9) | 37 (5.7) |

| DCI, mean ± SD | 7.7 ± 2.7 | 8.0 ± 3.3 | 7.9 ± 3.2 |

| RxRisk-V score, mean ± SD | 4.1 ± 2.7 | 5.1 ± 2.6 | 5.0 ± 2.6 |

DCI = Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index; NA = not available; SD = standard deviation.

Patterns of Use

The most common first-line systemic therapy was treatment with oral antiangiogenic TKIs, which were administered to 445 patients (68.6%). The most frequently used TKI was sunitinib (n = 285; 43.9%), followed by sorafenib (n = 91; 14.0%), pazopanib (n = 65; 10.0%), and axitinib (n = 4; < 1%). The next most common class of therapy was mTOR inhibitors (n = 128; 19.7%): 96 patients (14.8%) received temsirolimus and 32 patients (4.9%) received everolimus. Sixty-one patients (9.4%) received the anti-VEGF agent bevacizumab, and 15 patients (2.3%) received the cytokines interferon alfa (n = 14; 2.2%), and aldesleukin (n = 1; < 1%). This pattern of utilization was generally consistent with NCCN guidelines7 and was similar among commercial and Medicare patients. Because of the small numbers of patients treated with axitinib, interferon alfa, and aldesleukin, those patients were excluded from further analyses.

A total of 78 patients switched therapies within 180 days of the post-index observation period; overall, 243 patients received second-line therapy from the index date to the end of the study period. The most common second-line agent was everolimus (29.2%), followed by bevacizumab (19.8%), temsirolimus (15.6%), sunitinib (13.6%), pazopanib (11.5%), and sorafenib (10.3%).

Among oral agents, the median starting and ending doses were the same for each drug except for sunitinib, and no difference between median starting and ending doses was observed for the injectable agents (Table 2).15-20 Overall, mean time to first-line treatment discontinuation ranged from 137.0 days with everolimus to 171.8 days with temsirolimus. Among TKIs, there was no significant difference (chi-square P = 0.159) in mean time to discontinuation between sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib (169.1, 160.1, and 160.3 days, respectively). Among injectable agents, mean time to discontinuation was significantly shorter for bevacizumab than temsirolimus (150.8 vs. 171.8 days, respectively; chi-square P = 0.03). Some patient data were excluded from the dosing analysis because of small sample sizes or single administrations of study drugs. In particular, there were many exclusions in the bevacizumab group because bevacizumab is recommended to be administered in combination with interferon alfa, and a large portion of patient data was excluded because of the variation in claim sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Patterns of Use of First-Line Systemic Therapies for mRCC (N = 649)

| Medication | n | Median (Range) Starting Dose, mg | Median (Range) Ending Dose, mg | Days to First-Line Treatment Discontinuation, Days ± SD | n | Days to Switch in Therapy, Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injectable | ||||||

| Temsirolimus | 95 | 25.0 (12.5-50.0)a | 25.0 (12.5-50.0)a | 171.8 ± 26.2 | 6 | 102.7 ± 37.8 |

| Bevacizumab | 28 | 700.0 (650.0-900.0)b | 700.0 (650.0-900.0)b | 150.8 ± 56.0 | 3 | 20.7 ± 32.3 |

| Oral | ||||||

| Sunitinib | 282 | 33.3 (12.5-50.0)c | 25.0 (12.5-50.0)c | 169.0 ± 29.5 | 36 | 109.2 ± 46.3 |

| Sorafenib | 91 | 800.0 (800.0-800.0)d | 800.0 (800.0-800.0)d | 160.1 ± 41.4 | 12 | 81.8 ± 57.1 |

| Pazopanib | 62 | 800.0 (800.0-800.0)e | 800.0 (800.0-800.0)e | 160.3 ± 41.1 | 10 | 71.9 ± 28.0 |

| Everolimus | 32 | 10.0 (5.0-10.0)f | 10.0 (5.0-10.0)f | 137.0 ± 62.2 | 11 | 63.6 ± 47.4 |

aRecommended dose: 25 mg intravenous infusion once weekly.15

bRecommended dose: 10 mg/kg intravenous infusion every 2 weeks with interferon alfa.16

cRecommended dose: 50 mg once daily, 4 weeks on treatment followed by 2 weeks off.17

dRecommended dose: 400 mg twice daily.18

eRecommended dose: 800 mg once daily.19

fRecommended dose: 10 mg once daily.20

mRCC = metastatic renal cell carcinoma; SD = standard deviation.

Medication Persistence and Compliance

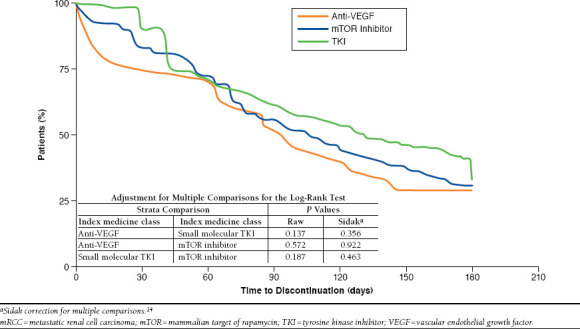

Persistence and compliance were high (PDC ≥ 80% and MPR ≥ 80%) in ≥ 60% of patients overall (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in compliance between oral and injectable agents; however, persistence was significantly higher with oral agents compared with injectables (P = 0.002). Compliance with oral therapy was highest for sunitinib (80.5%), followed by pazopanib (78.4%), everolimus (73.3%), and sorafenib (67.3%); the differences were not statistically significant. Values for persistence were similar: sunitinib, 91.0%; pazopanib, 88.0%; everolimus, 84.2%; and sorafenib, 81.8%. Persistence and compliance with injectable therapy were numerically higher for temsirolimus compared with bevacizumab, but the differences were not statistically significant. A Kaplan-Meier analysis of treatment persistence by drug class (TKI, anti-VEGF, and mTOR inhibitor) revealed no significant differences (Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Medication Compliance (MPR) and Persistence (PDC) for First-Line Therapies for mRCC (N = 476)

| Medication | MPR | PDC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare | Commercial | Total | Medicare | Commercial | Total | |||||||

| n | MPR ≥ 80% | n | MPR ≥ 80% | n | MPR ≥ 80% | n | PDC ≥ 80% | n | PDC ≥ 80% | n | PDC ≥ 80% | |

| Injectable | ||||||||||||

| Bevacizumab | 8 | 62.5% | 5 | 60.0% | 13 | 61.5% | 12 | 75.0% | 5 | 60.0% | 17 | 70.6% |

| Temsirolimus | 64 | 67.2% | 11 | 81.8% | 75 | 69.3% | 71 | 76.1% | 11 | 90.9% | 86 | 78.0% |

| P = 0.58a | P = 0.51a | |||||||||||

| Oral | ||||||||||||

| Everolimus | 12 | 75.0% | 3 | 66.7% | 15 | 73.3% | 15 | 80.0% | 4 | 100.0% | 19 | 84.2% |

| Pazopanib | 31 | 77.4% | 6 | 83.3% | 37 | 78.4% | 44 | 88.6% | 6 | 83.3% | 50 | 88.0% |

| Sorafenib | 49 | 65.3% | 6 | 83.3% | 55 | 67.3% | 59 | 81.4% | 7 | 85.7% | 66 | 81.8% |

| Sunitinib | 147 | 81.0% | 48 | 79.2% | 195 | 80.5% | 186 | 91.9% | 48 | 87.5% | 234 | 91.0% |

| P = 0.21a | P = 0.19a | |||||||||||

| Total injectable | 88 | 68% | 99 | 77% | ||||||||

| Total oral | 302 | 77% | 369 | 89% | ||||||||

| P = 0.75a | P = 0.002a | |||||||||||

aP values were calculated by chi-square test (P < 0.05 was considered significant).

MPR = medication possession ratio; mRCC = metastatic renal cell carcinoma; PDC = proportion of days covered.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier Analysis of mRCC First-Line Treatment Persistence by Therapeutic Class

Comorbidities

Overall, the most common comorbidities among the study population were hypertension (76.4%), dyslipidemia (56.9%), hyperlipidemia (56.8%), diabetes (38.4%), ischemic heart disease (25.7%), and other forms of heart disease (38.4%). There was no significant difference in the distribution of these comorbidities among the individual drugs.

Therapy by Specialty and Site of Care

First-line treatment regimens were analyzed by prescriber specialty and by site of care for injectable drugs. Database coding indicated that internal medicine specialists were the largest group of providers of oral drugs, and accounted for the majority of prescriptions for everolimus (78.1% of prescriptions), sorafenib (67.0%), sunitinib (63.5%), and pazopanib (58.5%). The second most common group of providers for oral drugs was identified as specialists in hematology/oncology (pazopanib, 23.1%; sunitinib, 17.2%; sorafenib, 16.5%; everolimus, 9.4%). Providers could potentially identify as internal medicine specialists because they possess both internal medicine and oncology specialty board certifications. Family practitioners or emergency medicine specialists were infrequent prescribers. Among injectable drugs, a large proportion of prescriptions were identified as being from other providers (bevacizumab, 62.3%; temsirolimus, 33.3%), although a substantial proportion of providers were identified as internal medicine specialists (bevacizumab, 21.3%; temsirolimus, 36.5%). Other providers included specialities that were not identified from the source and those that were identified but not in the specialty categories listed. Injectable drugs were primarily administered at a physician’s office; additionally, injectable drugs were administered in a hospital outpatient setting or at inpatient centers.

Discussion

This retrospective study examined medical and pharmacy claims data from patients treated with systemic therapies for mRCC between January 2007 and December 2013. The Humana claims database provided baseline demographic characteristics and drug utilization for members insured by both commercial plans and Medicare. Data were analyzed to evaluate real-world patterns of use across the broad landscape of systemic therapies approved in this setting.

The NCCN Kidney Cancer Guidelines are a valuable resource for clinicians as a summary of evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of RCC and mRCC. Our results demonstrate that among the study population of Humana patients with mRCC, providers selected first-line therapies that were generally consistent with past and present NCCN guidelines. Sunitinib and pazopanib fall into category 1, indicating that, based on high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that these interventions are appropriate. Temsirolimus is listed as category 1 for poor-prognosis patients, and although bevacizumab in combination with interferon alfa also falls into category 1, it appears that not all patients who received bevacizumab also received interferon alfa as per the label. However, there is no mechanism to confirm prescriptions from the database, and caution should be exercised in interpreting the results. Sorafenib, the second-most commonly prescribed TKI, and axitinib are included in category 2A, indicating uniform NCCN consensus based on lower-level evidence. Everolimus, which is not approved for first-line therapy of mRCC and is not recommended in that setting by the NCCN, was nevertheless prescribed to 4.9% of the overall patient population in our study.

Among second-line therapies, the majority of the chosen agents are classified as category 1 or 2A by the NCCN. However, nearly 20% of patients received bevacizumab and more than 15% received temsirolimus, interventions that lack uniform NCCN consensus in the second-line setting after TKI therapy (category 2B). Departures from NCCN guidelines may have implications for the quality of care being provided to mRCC patients, and future studies should evaluate patient outcomes in the context of the NCCN guidelines.

The median starting doses for all drugs except sunitinib were consistent with their respective approved dosing regimens. The median daily starting dose of sunitinib reported in this study (33.3 mg) was lower than the approved daily dose (50 mg). However, this observation is a consequence of the 4-weeks-on, 2-weeks-off dosing schedule and the method of calculating the starting dose from the initial prescription (multiplying the strength of the medication by the quantity dispensed and then dividing by the number of days supply).

The observed treatment durations were in general agreement with those of previous retrospective studies.9,21-23 Although not compared for statistically significant differences, a chart abstraction-based study of American community oncology clinics found the median duration of treatment for first-line sorafenib and sunitinib to be similar to our findings (5.9 months [177 days] and 5.5 months [165 days], respectively).21 In contrast, the mean times to discontinuation of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus were longer in our study than those reported by Hess et al. (2013): sorafenib 160.1 vs. 148.8 days; sunitinib, 169.1 vs. 143.5 days; and temsirolimus, 171.8 vs. 126.9 days.22 We also observed a longer mean time to discontinuation of pazopanib than was reported previously by Hackshaw et al. (2014): 160.3 vs. 112.2 days.9 Additionally, the proportions of first-line pazopanib patients in our study who were highly persistent (88.0%) and highly compliant (78.4%) were greater than those reported by Hackshaw et al. (highly persistent, 64.5%; highly compliant, 66.7%). However, as part of a global medical records review of patterns of use among advanced RCC patients receiving first-line angiogenesis inhibitors, Oh et al. (2014) reported treatment durations for patients in the United States that were substantially longer than those observed in our claims-based review: 7.8 months (234 days) for sunitinib, 8.1 months (243 days) for sorafenib, and 13.7 months (411 days) for bevacizumab.23 However, the discrepancy may result from the use of the 180 day post-index window specified in this study’s protocol. Future studies should examine whether higher levels of persistence, compliance, and duration of treatment result in improved patient outcomes.

Analysis of patterns of use by line of business (commercial vs. Medicare) revealed no substantial differences, even though Medicare patients were older and had higher comorbidity scores. Analysis of patterns of use by provider specialty revealed that the majority of prescribing providers were identified as internal medicine specialists, which was slightly surprising, although oncologists represented a substantial portion of providers. Care for mRCC patients receiving injectable drugs was largely provided at physician offices rather than hospital outpatient or inpatient centers. Future studies should explore these trends in prescribing and provision of care because they could influence how and where educational and interventional efforts should be focused.

Limitations

The study design imposes certain limitations. The 180-day post-index follow-up requirement is a potential source of time-dependent survivor bias. Because of censoring, analysis of time-to-event endpoints such as time to treatment switch or discontinuation may be confounded if switches or discontinuations occur after the follow-up. Another limitation is that treatment discontinuation may occur before completing the last prescription fill. In addition, a number of new agents were approved for the treatment of mRCC during the time period of the study. The trends observed in the current analysis may partly be a reflection of the availability of these agents and may not necessarily reflect the latest patterns of use.

There are several limitations associated with the use of administrative claims for the study of treatment practice patterns. Many clinical variables that provide information on disease severity, such as cancer stage at diagnosis, tumor size, and overall health status, are not available from administrative claims databases. For example, although approximately 80% of RCC is typically of clear-cell histology, that proportion could not be confirmed in our patient population from the available data. Also, in the absence of medical records, prescription refills or changes in therapy cannot be correlated with a new diagnosis or change in disease status. It was also not possible to determine whether or not a patient was enrolled in a clinical trial from Humana’s data. Additionally, the pharmacy claims data do not record prescriber directions; as described above, dosages were calculated based on the reported days supply in the claim, which could result in under- or over-reporting of daily or weekly dosing.

Other limitations common to studies using administrative claims data include errors in claims coding and missing data. No causal inference can be ascertained from this study, because it was an observational study using retrospective claims data for descriptive purposes only. Aspects of this study were prone to small sample sizes, precluding the use and meaningful interpretation of formal statistical comparisons. Although Humana is a large national health plan with members residing in a broad array of geographic regions, this study used data from Humana members only and the results may not be representative of the overall U.S. population.

Conclusions

In this retrospective, claims-based study of Humana members with mRCC, patterns of use of systemic therapies were similar for each of the agents studied, and prescribed therapies were consistent with NCCN guidelines. Although oral therapies had slightly longer times to discontinuation and higher compliance compared with injectable therapies, overall, the majority of patients demonstrated a high level of persistence and compliance with first-line treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Sinkins, PhD, ProEd Communications, for his medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Reference

- 1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 2. Diaz JI, Mora LB, Hakam A. The Mainz classification of renal cell tumors. Cancer Control. 1999;6(6):571-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(12):865-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Motzer RJ, Russo P. Systemic therapy for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2000;163(2):408-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhury S, Larkin JM, Gore ME. Recent advances in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and the role of targeted therapies. Eur J Cancer.2008;44(15):2152-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelson EC, Evans CP, Lara PN, Jr.. Renal cell carcinoma: current status and emerging therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(3):299-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, et al. Kidney cancer, version 3. 2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(2):151-59. Available at: http://www.jnccn.org/content/13/2/151.full.pdf+html. Accessed December 11, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DaCosta Byfield SA, McPheeters JT, Burton TM, Nagar SP, Hackshaw MD. Persistence and compliance among U.S. patients receiving pazopanib or sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective claims analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(6):515-22. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=19651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hackshaw MD, Nagar SP, Parks DC, Miller LA. Persistence and compliance with pazopanib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma within a U.S. administrative claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(6):603-10. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=18156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol.1992;45(6):613-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care.2003;41(1):84-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sloan KL, Sales AE, Liu C-F, et al. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care.2003;41(6):761-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62(318):626-33. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Torisel kit (temsirolimus) injection, for intravenous infusion only. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. February 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022088s018lbl.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 16. Avastin (bevacizumab) solution for intravenous infusion. Genentech. May 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125085s308lbl.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 17. Sutent (sunitinib malate) capsules, oral. Pfizer Labs. 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021938s028s029lbl.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 18. Nexavar (sorafenib) tablets, oral. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. November 2013. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021923s016lbl.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 19. Votrient (pazopanib) tablets, for oral use. GlaxoSmithKline. April 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022465s020lbledt.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 20. Afinitor (everolimus) tablets for oral administration. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. May 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022334s030lbl.pdf.. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 21. Feinberg BA, Jolly P, Wang S-T, et al. Safety and treatment patterns of angiogenesis inhibitors in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: evidence from U.S. community oncology clinics. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):786-94. Available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12032-011-9922-z. Accessed December 11, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hess G, Borker R, Fonseca E. Treatment patterns: targeted therapies indicated for first-line management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in a real-world setting. Clin Genitourin Cancer.2013;11(2):161-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oh WK, McDermott D, Porta C, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitor therapies for advanced renal cell carcinoma: toxicity and treatment patterns in clinical practice from a global medical chart review. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(1):5-16. Available at: http://www.spandidos-publications.com/ijo/44/1/5. Accessed December 11, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]