Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Reimbursement for the use of hepatitis B virus (HBV) treatments has not been previously reported for public payers.

OBJECTIVE:

To describe the number of users and total cost of HBV treatments over the last 16 years among residents of Ontario, Canada, who were covered by the public drug program.

METHODS:

We conducted a repeated cross-sectional study for HBV treatments reimbursed by the public drug program in Ontario from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2015. We projected total spending to 2020 based on current utilization trends.

RESULTS:

HBV drug users per year increased 30-fold, from 132 users in 2000 to 4,035 users in 2015. Total spending on HBV treatments increased 150-fold, from $136,368 annually in 2000 to $21.0 million in 2015. The spending on HBV agents is projected to increase by 65%, with an estimated drug cost of $34.6 million by 2020.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although not reimbursed as first-line therapy, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate has become the most commonly reimbursed HBV treatment and was associated with an increase in HBV treatment use and total spending. Results of this study found that rapid growth of HBV treatments led to a sustained increase in spending for public payers in Ontario.

What is already known about this subject

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a growing public health concern worldwide that may require chronic lifelong treatment.

Newer and more expensive oral treatment agents have been introduced to the market over the last 15 years.

HBV treatments are often available through prior authorization reimbursement programs to allow for more cost-effective use, but clinical guidelines often favor newer agents and do not account for cost-effectiveness.

What this study adds

This study examined the use of oral HBV treatments and forecasts their future use.

Study results showed that there has been a sharp increase in the number and cost of individuals using HBV treatment in Ontario, Canada, and treatment patterns have changed greatly over the study period with the introduction of new treatment options.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate had rapid uptake following its introduction to the formulary and has become the most common treatment even though it is listed as a second-line treatment option, possibly because of physician preference and clinical guideline recommendations.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global public health concern with an estimated 250 million people infected worldwide and 686,000 attributable deaths annually.1 HBV is estimated to have a chronic prevalence of 1% in Canada, with higher prevalence occurring among aboriginal peoples and immigrant populations.1 Treatment of HBV aims to prevent or reverse liver disease progression, minimize risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, decrease risk of transmission, and improve quality of life.2-4 Treatments are categorized into 2 groups: oral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF], and lamivudine) and injectable interferons (standard interferon and pegylated interferon). Oral treatments are often a lifelong therapy, while interferons are used as finite treatment regimens (usually over 48 weeks). Selection of treatment is complex and should take into account many factors, such as evidence of liver fibrosis; risk of liver disease progression; laboratory markers (HBV DNA, serology, and liver enzymes); host characteristics; and past treatment history.2-5

In Ontario, and similar to many payers worldwide,6 HBV treatments are available through a prior authorization reimbursement program (Table 1). A step-therapy approach is applied that is based on a combination of clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence, driving the use of less expensive agents as first-line therapy and escalating to more expensive therapies in the event of failure. For HBV, lamivudine is listed as the first-line treatment, with all other oral treatments reserved as second-line if lamivudine fails or after disease progression. Treatment is generally reserved for those with signs of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. With the introduction of newer oral agents over the last 15 years (e.g., TDF in 2004 and entecavir/adefovir in 2008) and clinical guidelines favoring newer agents, it is unknown how utilization trends have changed among publicly funded individuals in Ontario. The purpose of this study was to describe the use of oral HBV treatments and forecast their future use.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Prior Authorization Requirements for Oral Chronic Hepatitis B Treatments in Ontario

| Product | Criteria: Completed Annually (Except After Liver Transplant) |

|---|---|

| Adefovir |

|

| Entecavir |

|

| Lamivudine |

First-line Treatment

|

| Tenofovir |

|

Adapted from Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. EAP reimbursement criteria for frequently requested drugs. Updated September 1, 2017. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/pdf/frequently_requested_drugs.pdf. ALT = alanine aminotransferase.

Methods

We conducted a repeated cross-sectional study by examining prescription claims for HBV treatments that were reimbursed by the public drug program in Ontario from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2015. We set out to measure the total number of users, total medication cost, and market share of available oral HBV treatments annually over this period. We also projected total spending to 2020 based on utilization trends.

Users were included in each calendar year if they had 1 prescription dispensed for any oral HBV treatment. Users of HBV specific formulations (adefovir, entecavir, and lamivudine) were assumed to have used the treatment for HBV. HBV-specific treatments were defined as any formulation or dosage of drugs that were only indicated for the treatment of HBV. To limit TDF users to those with HBV, they had to meet 1 of the following criteria from the time of their first claim: (a) any hepatitis B diagnosis during health care visits (emergency department or hospital admissions) in the past 10 years, (b) receipt of an HBV-specific treatment in the past 10 years, or (c) no concurrent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatments.

All publicly funded drug claims were identified using the Ontario Drug Benefit database, which contains all prescriptions dispensed to eligible Ontario residents. Drug coverage is provided to Ontario residents with financial needs (due to high drug costs and/or low income); all residents aged 65 years and older; and those living in long-term care or in need of home care. The public program represents 23% of the Ontario population, with 49% of all HBV prescriptions paid for by the public drug program. Prescription claims for patients who receive medications through private coverage or who pay out of pocket are not captured in this database.6

We identified emergency department visits and hospital admissions data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and Discharge Abstract Database, respectively. These databases are linked by encoded health card numbers at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and are routinely used in drug research.

We fit the time series using a linear holt exponential smoothing model to forecast the total spending up to 2020 based on trends observed in the previous 16 years. This model accounts for a linear trend in the series and fits a smoothing function for forecasting. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Canada.

Results

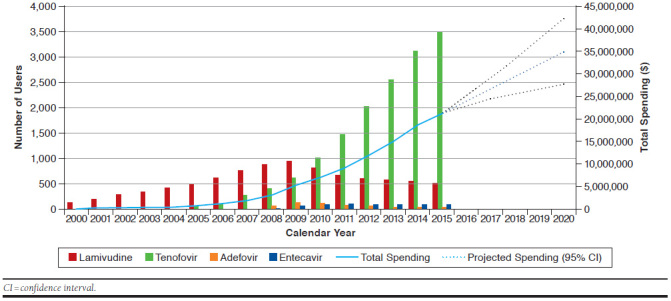

Over the 16-year study period, the number of HBV drug users per year increased 30-fold, from 132 users in 2000 to 4,035 users in 2015 (Figure 1). Over this time, total spending on HBV treatments increased similarly, rising from $136,368 annually in 2000 to $21.0 million in 2015. The largest increase in cost of HBV agents occurred following the introduction of TDF to the formulary in 2004, with spending nearly doubling from $489,293 to $816,531 between 2004 and 2005, respectively. Over the study period, the cost per user increased 4-fold, from $1,033 per user in 2000 to $5,198 per user in 2015. The spending on HBV agents is projected to increase by 65% between 2016 and 2020, with an estimated drug cost of $34.6 million by 2020.

FIGURE 1.

Number of Publicly Funded Chronic Hepatitis B Treatment Users and Total Spending in Ontario from 2000 to 2015

Over the study period, there was a large change in the market share of HBV drugs. Between 2000 and 2003, all HBV users were treated with lamivudine, since it was the only approved oral treatment available on the public drug formulary. Over the following 6 years, lamivudine remained the most common reimbursed oral treatment, but the prevalence of lamivudine use dropped from 88.3% in 2005 (n = 499) to 67.2% in 2009 (n = 950), while the prevalence of TDF use quickly increased from 12.2% (n = 69) to 43.7% (n = 618) over the same time period. Since 2010, TDF has been the most common HBV treatment among publicly funded users, increasing from 59.4% (n = 1,011) of users in 2010 to 86.3% (n = 3,484) of users in 2015. Entecavir (n = 24 in 2008 to n = 97 in 2015) and adefovir (n = 73 in 2008 to n = 40 in 2015) have seen relatively low rates of use over the entire study period.

Discussion

There has been a sharp and consistent growth in the number and cost of publicly funded individuals using HBV treatments in Ontario between 2000 and 2015. The HBV treatments used have also changed greatly over the study period with the introduction of new treatment options. In particular, TDF had rapid uptake following its introduction to the formulary in 2004 and was the most commonly used HBV treatment in 2015.

The results are surprising based on the listing of these agents on the Ontario public drug formulary. Growth of this drug class outpaced public drug spending growth over the same time period.7 Current listings of the agents have specific criteria that must be fulfilled in order to obtain treatment and were developed using clinical guideline recommendations and cost-effectiveness evidence. Use of TDF was high despite it being listed as a second-line treatment, with criteria only allowing reimbursement among patients with lamivudine failure or advanced fibrosis (F3 or F4), along with ALT and HBV DNA. Patients meeting any of these criteria would be eligible for TDF.

We expected the patterns observed in this study to reflect a number of confluent factors. First, because any HBV treatment can currently only be obtained for patients with evidence of fibrosis using invasive testing, physicians may prefer to wait to use TDF, which is more potent, has lower rates of resistance, and has a decreased chance of viral breakthrough in an already sick patient population.2-4 Second, approximately half of publicly funded HBV users in Ontario are born outside of Canada, and many have had previous treatment with other agents, such as lamivudine, which would lead to entecavir being contraindicated due to resistance patterns.6 Third, clinical guidelines recommend TDF and entecavir as first-line treatment options for HBV, which likely influences physician practice patterns despite different reimbursement requirements in Ontario’s public drug program.2-4 Some physicians may have accessed TDF outside of the hepatitis B program via HIV-facilitated prescriber programs allowing them earlier off-label access. These programs do not require submission of prior authorizations for the reimbursement of any HIV treatments, as long as the prescriber is a registered HIV prescriber.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations, and the results of the analysis must be interpreted in the context of its design. First, the analysis was limited based on the accuracy of the database in recording of International Classification of Diseases codes for HBV. No previous validation studies have been conducted to assess the validity of HBV diagnosis codes, and since some treatments can be used for alternate indications, there may have been some patients who were not captured or who had dual indications. To strengthen the confidence in our results for non-HBV specific treatments, we used a combination of previous diagnoses, hospitalizations for HBV, previous use of HBV-specific treatments, and ongoing HIV drug treatments to identify patients with HBV. Previous work using the same methodology and population found that less than 2% of HBV users had HIV coinfection.6

Second, we did not have detailed clinical information, such as viral level or fibrosis staging, that would provide insight into the severity of illness of users. Future work should explore the agreement of reimbursement criteria with actual disease severity and the changing severity of patient illness over time.

Finally, this study did not include prescription claims paid for by private insurers or out of pocket by patients. Thus, the results are only representative of the claims paid for by the Ontario Public Drug Programs (OPDP) and may not be generalizable to the entire Ontario population. Future work should attempt to measure all use in Ontario and explore the uptake of newer agents, such as tenofovir alafenamide, and the use of noninvasive testing for fibrosis. A better understanding of the interaction of the private and public drug systems may further elucidate the reasons for growth of public spending on this drug class.

Conclusions

The rate of HBV treatment reimbursed by the OPDP has experienced rapid and sustained growth over the 16-year study period, which has led to a large increase in spending that is projected to continue to grow. This growth appears to be driven by the introduction of novel treatments, with TDF becoming the most common treatment since its introduction to the formulary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brogan, in Ottowa, Ontario, for the use of its Drug Product and Therapeutic Class Database.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ.. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1546-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH.. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57(1):167-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6(3):531-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dienstag JL, Goldin RD, Heathcote EJ, et al. Histological outcome during long-term lamivudine therapy. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(1):105-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martins D, Tadrous M, Fernandes Ket al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B in Ontario. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. September 28, 2015. Available at: http://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Hep-B_Pepi-Report_Sept-28-2015.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2018.

- 7.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2016: A Focus on Public Drug Programs. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2016. [Google Scholar]