Abstract

BACKGROUND:

There is growing concern about appropriate disease management for peripheral artery disease (PAD) because of the rapidly expanding population at risk for PAD and the high burden of illness associated with symptomatic PAD. A better understanding of the potential economic impact of symptomatic PAD relative to a matched control population may help improve care management for these patients.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the medical resource utilization, costs, and medication use for patients with symptomatic PAD relative to a matched control population.

METHODS:

In this retrospective longitudinal analysis, the index date was the earliest date of a symptomatic PAD record (symptomatic PAD cohort) or any medical record (control cohort), and a period of 1 year pre-index and 3 years post-index was the study time frame. Symptomatic PAD patients and control patients (aged ≥ 18 years) enrolled in the MarketScan Commercial and Encounters database from January 1, 2006, to June 30, 2010, were identified. Symptomatic PAD was defined as having evidence of intermittent claudication (IC) and/or acute critical limb ischemia requiring medical intervention. Symptomatic PAD patients were selected using an algorithm comprising a combination of PAD-related ICD-9-CM diagnostic and diagnosis-related group codes, peripheral revascularization CPT-4 procedure codes, and IC medication National Drug Code numbers. Patients with stroke/transient ischemic attack, bleeding complications, or contraindications to antiplatelet therapy were excluded from the symptomatic PAD group but not the control group. A final 1:1 symptomatic PAD to control population with an exact match based on age, sex, index year, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was identified. Descriptive statistics comparing patient demographics, comorbidities, medical resource utilization, cost, and medication use outcomes were generated. Generalized linear models were developed to compare the outcomes while controlling for residual difference in demographics, comorbidities, pre-index resource use, and pre-index costs.

RESULTS:

3,965 symptomatic PAD and 3,965 control patients were matched. In both cohorts, 54.7% were male, with a mean age (SD) of 69.0 (12.9) years and a CCI score of 1.3 (0.9). Symptomatic PAD patients had more cardiovascular comorbidities than control patients (27.7% vs. 12.6% coronary artery disease, 27.1% vs. 15.9% hyperlipidemia, and 49.8% vs. 28.2% hypertension) in the pre-index period. Post-index rates of ischemic stroke, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and cardiovascular- or PAD-related procedures (limb amputations, endovascular procedures, open surgical procedures, percutaneous coronary intervention, and coronary artery bypass graft) were higher among symptomatic PAD patients versus control patients. All-cause annualized inpatient admissions (0.46 vs. 0.22 admissions), emergency department/urgent care days (0.27 vs. 0.22 days), and office visit days (12.5 vs. 10.2 days) were higher among symptomatic PAD versus control patients post-index. Annualized all-cause inpatient costs ($8,494 vs. $3,778); outpatient costs ($8,459 vs. $5,692); and total costs ($20,880 vs. $12,501) were higher among symptomatic PAD versus control patients post-index. Only 17.8% of symptomatic PAD patients versus 6.6% of control patients were on clopidogrel pre-index. In the post-index period, clopidogrel prescriptions in the symptomatic PAD population increased to 38.0%. Results were consistent in the regression models with the symptomatic PAD population having a higher number of all-cause post-index inpatient admissions, emergency department/urgent care days, office visit days, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, and total costs versus control patients (P ≤ 0.026).

CONCLUSIONS:

Symptomatic PAD patients have significantly higher medical resource use and costs when compared with a matched control population. As the prevalence of symptomatic PAD increases, there will be a significant impact on the population and health care system. The rates of use of evidence-based secondary prevention therapies, such as antiplatelet medication, were low. Therefore, greater effort must be made to increase utilization rates of appropriate treatments to determine if the negative economic and clinical impacts of symptomatic PAD can be minimized.

What is already known about this subject

Patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) have a high risk of lower-extremity limb amputations and are at increased risk of atherosclerotic complications.

Because of the high burden of illness associated with symptomatic PAD, there is growing concern about appropriate disease management.

Hospitalization rates and health care costs associated with symptomatic PAD are known to be high but have not been compared with a suitably matched patient population.

What this study adds

This study compared health care services and costs for symptomatic PAD patients with a suitably matched control population.

Symptomatic PAD was associated with higher health care utilization and costs when compared with the matched control population.

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common atherosclerotic condition characterized by arterial narrowing in the extremities. Patients with PAD may experience symptoms of acute or chronic limb ischemia, such as muscle cramping or numbness, rest pain, intermittent claudication (IC), ulcers, and gangrene (symptomatic PAD).1 Ultimately, symptomatic PAD may result in loss of lower extremity limbs. Compared with healthy controls, patients with symptomatic PAD have an increased risk of atherosclerotic complications associated with occlusion of coronary and cerebral arteries, such as ischemic stroke, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and death.2,3

The prevalence of symptomatic PAD is approximately 5.8% in individuals aged 40 or more years in the United States.4 However, the prevalence of PAD increases with age, and the risk of developing PAD is increased in patients with diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and patients who smoke.5 Therefore, the prevalence of symptomatic PAD in the United States will likely rise as the population ages, and the number of patients with risk factors for PAD continues to increase. Because of the rapidly expanding population at risk for PAD, and the high burden of illness associated with symptomatic PAD, there is growing concern about appropriate disease management.6

Loss of lower extremity limbs with subsequent decreased ambulation and productivity, as well as atherosclerotic complications, may have a profound impact on the clinical and economic burden associated with symptomatic PAD. Indeed, hospitalization rates and health care costs associated with symptomatic PAD in the United States are known to be high,7,8 but the burden of illness has not been well characterized compared with the general patient population. A better understanding of the potential clinical and economic impact of symptomatic PAD relative to a matched control patient population may help improve care management in these patients by advocating the use of appropriate medication and preventive services before the onset of limb ischemia. In addition, contrasting the costs associated with symptomatic PAD from other comorbid conditions is important to assess resource allocation. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the medical resource utilization, costs, and medication use for patients with symptomatic PAD relative to a matched control patient population.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective longitudinal database analysis, using the MarketScan Commercial and Encounters Database (MCED). The MCED is an employer-sponsored health care claims database that covers a broad geographic area of the United States, with a reported 29.1 million lives. Claims data from employers, health plans, and other carriers are fully integrated by the use of a unique assigned patient identifier, enabling patients to be followed as long as they remain with the same employer, even if they switch health plans. The MCED is HIPAA-compliant.

For the symptomatic PAD cohort, an individual’s first symptomatic PAD diagnosis and/or indicator of initial treatment from January 2006 through June 2010 was defined as the index event. For the control cohort, a patient’s first medical record from January 2006 through June 2010 was defined as the index event. The study time frame was a period of 1 year pre-index and 3 years post-index.

Symptomatic PAD Patient Selection

Patients included in the symptomatic PAD cohort were required to be aged ≥ 18 years with continuous enrollment for ≥ 1 year before and 3 years after the index event. Symptomatic PAD was defined as having evidence of IC and/or acute critical limb ischemia requiring medical intervention identified by records of at least 1 of the following: (a) primary symptomatic PAD diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] diagnosis of 440.2x [atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities], 440.4 [chronic total occlusion of artery of the extremities], 443.9 [peripheral vascular disease, unspecified], or 785.4 [gangrene]) with a pharmacy claim of cilostazol or pentoxifylline within 90 days before or after diagnosis; (b) hospitalization with a discharge diagnosis-related group (DRG) code of 299 (peripheral vascular disorders with major complications/comorbidities [W MCC]), 300 (peripheral vascular disorders W CC), and 301 (peripheral vascular disorders W/O CC/MCC); (c) a primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis (see above) on the same day as a record of a Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition (CPT-4) or ICD-9-CM procedure code for lower extremity amputation, open (surgical procedures), endovascular (angioplasty, peripheral revascularization [PRV] with or without stent replacement), and other symptomatic PAD interventional procedures.

Patients excluded from the analysis were those with unknown sex; those aged > 115 years; those who had a diagnosis of transient ischemic attack (TIA), stroke, or moderate or severe bleeding disorders in the pre-index period; or those who had a diagnosis of thrombocytopenia, platelet dyscrasias, or coagulation disorders at any time during the study period.

Control Patient Selection

Patients included in the control cohort were those with any medical record from January 2006 through June 2010 (first record is index event), and who were aged ≥ 18 years with continuous enrollment for ≥ 1 year before and 3 years after the index event. Patients excluded from the analysis were those with unknown sex, those aged > 115 years, or those who did not have continuous enrollment for 3 years post-index. Patients in the symptomatic PAD cohort were excluded from the control patient cohort.

Population Matching

The matching process was performed in 2 steps to limit the control population to a manageable number for comorbidity assessment. First, an exact matching algorithm based on exact age, sex, and index year on a 5:1 ratio (control:symptomatic PAD) was applied to the 2 cohorts. To ensure that symptomatic PAD patients were matched with control patients with a similar level of morbidity, in the second step of the process the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was computed for the patients identified in the matching algorithm. PAD was included in the CCI computation. Patients from the control cohort with CCI that matched exactly to the symptomatic PAD patients were selected. As a result, a final 1:1 control population with an exact match based on age, sex, index year, and CCI to the symptomatic PAD population was identified.

Assessments and Outcomes

Pre-index demographic and comorbidity information was collected for patients in both cohorts. Medical resource utilization was tracked during the pre-index and post-index periods and included the frequency of cardiovascular (CV)-related diagnoses of nonfatal ACS (ST segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], non-STEMI [NSTEMI], and unstable angina [UA]), nonfatal hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, and TIA. The frequency of CV- and PAD-related procedures was also tracked and encompassed coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with or without stent placement; lower limb amputation; open surgical procedures (endarterectomy, embolectomy, and bypass grafts); endovascular procedures (peripheral angioplasty, peripheral percutaneous interventions) with or without stent placement; and major bleeding complications (any bleeding episode that required treatment) as indicated by primary diagnostic ICD-9-CM record or CPT-4 record. The frequency of inpatient care including all-cause, PAD-related (worsening claudication, acute limb ischemia, urgent PRV), ACS-related, and stroke-related hospital admissions; all-cause and PAD-related emergency department (ED)/urgent care (UC) days; and all-cause and PAD-related office visit days were tracked during the pre-index and post-index periods.

Costs were tracked during the pre-index and post-index periods and adjusted to the 2013 medical care component of the Consumer Price Index. Costs captured for the symptomatic PAD and control cohorts were all-cause and PAD-related (i.e., treatment for IC, acute limb ischemia, amputation, or PRV) inpatient; outpatient (ED/UC and office visits); drug costs; and total costs.

Prescriptions of medications used to prevent thrombosis or that were indicated for secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events were tracked pre-index and post-index. Aspirin use cannot be tracked in the MCED so was not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of demographics, comorbidities, medical resource utilization, costs, and medication use between groups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Using the 1:1 matched population, outcome variables were also compared between groups using generalized linear models (GLM) where the models controlled for pre-index demographics, comorbidities, resource utilization, drug usage, and log of total pre-index costs. The GLM assumed negative binomial distributions for the models of integer outcomes (all-cause inpatient admissions, ED/UC days, and office visit days) and assumed gamma distributions for the models of cost outcomes (all-cause inpatient, outpatient, drug, and total costs). The variance inflation factor (VIF) was confirmed to be less than 5 for the independent variables included in these models.

Results

Patients

During the initial selection process, 16,663 symptomatic PAD patients and 5,809,590 control patients were identified (Figure 1). After 1:1 matching for age, sex, index year, and CCI, 3,965 symptomatic PAD and 3,965 control patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). In both cohorts, 54.7% were male, with a mean age (standard deviation [SD]) of 69.0 (12.9) years and a CCI score (SD) of 1.32 (0.9; Table 1). Symptomatic PAD patients had more CV comorbidities in the pre-index period than control patients (27.7% vs. 12.6% coronary artery disease, 27.1% vs. 15.9% hyperlipidemia, and 49.8% vs. 28.2% hypertension, respectively; Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient Selection and Matching

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Comorbidities in the Pre-index Period

| Control n = 3,965 | Symptomatic PAD n = 3,965 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 54.7 | 54.7 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.0 (12.9) | 69.0 (12.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score (SD) | 1.32 (0.9) | 1.32 (0.9) |

| Comorbidities, %a | ||

| Anemia | 4.0 | 5.3 |

| Aneurysm | 1.5 | 4.1 |

| Angina | 2.3 | 4.2 |

| Aortic stenosis | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| COPD | 5.6 | 10.3 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 7.6 | 10.7 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12.6 | 27.7 |

| Depression | 2.6 | 4.3 |

| Diabetes | 21.4 | 18.7 |

| GERD | 3.9 | 6.3 |

| Heart failure | 4.1 | 2.9 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 15.9 | 27.1 |

| Hypertension | 28.2 | 49.8 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Strokeb | 6.6 | 0.0 |

| Thromboembolic disease | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Valvular heart disease | 4.1 | 6.0 |

aOnly comorbidities with a statistically significant difference between cohorts are shown.

bBaseline stroke occurrence was excluded from the symptomatic PAD population.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; PAD = peripheral artery disease; SD = standard deviation.

Medical Resource Utilization

Post-index prevalence of ischemic stroke, NSTEMI, and UA were significantly higher for symptomatic PAD patients versus control patients (P < 0.05; Table 2). There was no significant difference between cohorts in the prevalence for STEMI or TIA. The frequency of patients with limb amputations, endovascular procedures, open surgical procedures, PCI, and CABG was significantly higher post-index for symptomatic PAD patients versus control patients (P < 0.001; Table 2). There was no significant difference between cohorts in the frequency of patients with procedures associated with bleeding events.

TABLE 2.

PAD-Related and Cardiovascular-Related Diagnoses and Procedures Prevalence During the 3-Year Post-index Period

| Control n = 3,965 | Symptomatic PAD n = 3,965 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnoses, % of patients | |||

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.208 |

| Ischemic stroke | 6.2 | 7.7 | 0.009 |

| NSTEMI | 2.5 | 3.4 | 0.029 |

| STEMI | 4.0 | 3.6 | 0.378 |

| UA | 4.8 | 6.4 | 0.002 |

| TIA | 6.1 | 6.6 | 0.381 |

| Procedures, % of patients | |||

| Amputation | 0.2 | 6.5 | < 0.001 |

| Endovascular | 0.4 | 14.0 | < 0.001 |

| Open surgical | 0.3 | 12.2 | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 10.5 | 15.2 | < 0.001 |

| CABG | 10.0 | 13.3 | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding complications | 27.4 | 29.2 | 0.085 |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; NSTEMI = non-STEMI; PAD = peripheral artery disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIA = transient ischemic attack; UA = unstable angina.

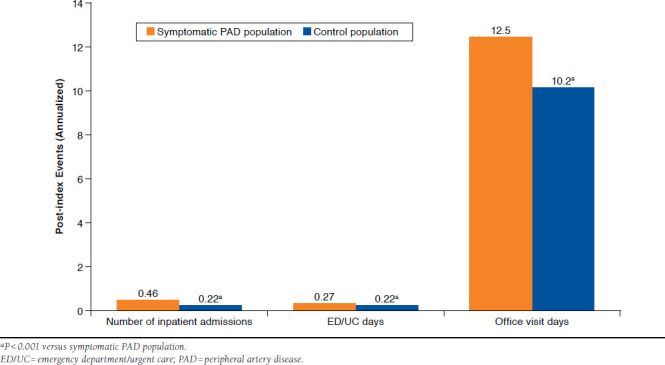

All-cause post-index annualized health care service events were significantly higher for symptomatic PAD patients versus control patients (P < 0.001; Figure 2). The average number (SD) of annualized inpatient admissions was 0.46 (0.53) versus 0.22 (0.37), respectively; the number of ED/UC days was 0.27 (0.66) versus 0.22 (0.49), and the number of office visit days was 12.5 (9.3) versus 10.2 (9.1; Figure 2). The numbers of post-index ACS-related and stroke-related annualized inpatient admissions in both cohorts were low (≤ 0.02) so were not significantly different between the symptomatic PAD and control populations.

FIGURE 2.

Annualized All-Cause Post-index Health Care Services

The descriptive statistics were supported by the GLM results, which produced statistically significant and directionally positive coefficients for the symptomatic PAD patients (all-cause post-index inpatient admissions, P < 0.001; ED/UC days, P = 0.005; office visit days, P = 0.026).

Costs

All-cause post-index annualized health care costs were significantly higher for symptomatic PAD versus control patients (P < 0.001; Figure 3). Inpatient costs were $8,494 versus $3,778, respectively; outpatient costs were $8,459 versus $5,692; drug costs were $3,927 versus $3,031; and total costs were $20,880 versus $12,501 (Figure 3). The total PAD-related annualized health care cost (SD) in the symptomatic PAD population was $4,006 ($6,762). The descriptive results were generally supported by GLM modeling, where all models demonstrated directionally positive coefficients for symptomatic PAD patients with statistically significant differences for all but the drug costs (all-cause post-index inpatient costs, P = 0.002; outpatient costs, P < 0.001; drug costs, P = 0.111; and total costs, P < 0.0 01).

FIGURE 3.

Annualized All-Cause Post-index Health Care Costs

Medication Use

Clopidogrel prescriptions in the pre-index period were significantly higher for symptomatic PAD versus control patients (17.8% vs. 6.6%, respectively; P < 0.001; Table 3). In the postindex period, clopidogrel prescriptions in the symptomatic PAD population increased to 38.0% (Table 3). Antithrombotic drugs or those indicated for secondary prevention of athero-thrombotic events in the pre-index and post-index periods were also significantly higher for symptomatic PAD versus control patients, albeit with low utilization rates among the symptomatic PAD patients in the post-index period (P < 0.001; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Medication Use in the Pre-index and Post-index Periods

| Medications, % of Patients | Pre-index | Post-index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n = 3,965 | Symptomatic PAD n = 3,965 | P Value | Control n = 3,965 | Symptomatic PAD n = 3,965 | P Value | |

| Clopidogrela | 6.6 | 17.8 | < 0.001 | 12.8 | 38.0 | < 0.001 |

| Claudication drugs | 0.9 | 33.7 | < 0.001 | 1.3 | 60.5 | < 0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 24.5 | 40.4 | < 0.001 | 38.9 | 54.2 | < 0.001 |

| Anticoagulant | 6.4 | 6.1 | 0.547 | 12.4 | 13.8 | 0.058 |

| ACE inhibitor | 25.6 | 33.7 | < 0.001 | 39.5 | 43.3 | < 0.001 |

| Other antiplatelet | 0.4 | 1.2 | < 0.001 | 1.4 | 2.5 | < 0.001 |

| ARB | 14.8 | 19.5 | < 0.001 | 22.1 | 26.1 | < 0.001 |

| Statin | 32.0 | 46.4 | < 0.001 | 48.0 | 63.9 | < 0.001 |

aPrasugrel and ticagrelor were not prescribed to any patients in the study cohorts during the pre-index period and were prescribed to only 6 patients during the post-index period.

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; PAD = peripheral artery disease.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective longitudinal analysis indicate that the health care resource and economic burden of symptomatic PAD is high compared with a control population matched for age, sex, index year, and comorbidity burden. Rates of ischemic stroke and ACS were significantly higher in the symptomatic PAD population, as were the frequency of patients with CV- and PAD-related procedures compared with the control population. Furthermore, the number of all-cause health care service events and all-cause costs were significantly higher in the symptomatic PAD population versus the control population. Not surprisingly, the use of antiplatelet therapy was significantly higher in symptomatic PAD patients compared with control patients.

In the current study, several of the tracked CV- and cerebrovascular-related events were significantly higher in symptomatic PAD patients versus control patients. These results are in agreement with a meta-analysis of data pooled from 16 different studies of patients with no history of coronary heart disease, where an ankle brachial index (ABI) of ≤ 0.90 added to the Framingham risk equation increased the risk of major coronary events (i.e., coronary death, nonfatal ACS) by approximately 2-fold.2 In addition, in a prospective observational study of 6,880 patients, after adjusting for comorbidities and history of CV or cerebrovascular events, the risk of CV-related events was increased by 64% and the risk of cerebrovascular-related events was doubled in patients with symptomatic PAD versus healthy controls.3

This study adds to the current knowledge by comparing all-cause health care services and costs for symptomatic PAD patients with a matched control cohort. Inpatient admission rates observed in this analysis indicate that hospitalization for symptomatic PAD patients occurred approximately every 2 years. The mean total annualized cost was $20,880 for symptomatic PAD patients, driven by nearly equal inpatient and outpatient costs. The results of the current study are in general agreement with previous studies that have demonstrated the high rates of hospitalizations and health care costs associated with PAD.7,9,10 In a managed care population in the United States, 35% of newly identified PAD patients were hospitalized during a follow-up period of at least 1 year, and the annualized PAD-related costs were $5,944 per patient.7 A 2008 registry study of U.S. patients showed that compared with patients with coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or asymptomatic PAD, patients with symptomatic PAD had the highest rate of annualized hospitalization-related costs.8,9 Based on these results, the annual cost in 2008 for vascular-related hospitalizations for symptomatic PAD in the United States was estimated to be > $21 billion.9

It is possible that the higher rates of CV disease burden in the symptomatic PAD cohort could account for the cost differential between the symptomatic PAD and control patients. However, a series of log-linked GLM models—assuming a gamma distribution for total costs, inpatient costs, drug costs, and outpatient costs controlling for cohort assignment (symptomatic PAD or control), baseline demographics, comorbidities, resource utilization, drug use, and log baseline costs—showed that baseline CV comorbidities were not significant drivers of these costs.

Current U.S. treatment guidelines recommend the use of antiplatelet therapy (either aspirin or clopidogrel) to prevent ACS, stroke, or vascular death events associated with atherosclerotic lower extremity symptomatic PAD.11 In this study, 17.8% and 38.0% of symptomatic PAD patients were receiving clopidogrel in the pre-index and post-index periods, respectively. The use of aspirin was not able to be tracked in the MCED database used for this analysis; therefore, the low proportion of patients using clopidogrel may be explained if the remaining patients were using aspirin. In addition, most of the generic clopidogrel formulations were not approved in the United States until 2012, and it is possible that utilization rates in this study may not be representative of current use, since improved access to a low-cost generic is now available. In the recent Trial to Assess the Effects of SCH 530348 in Preventing Heart Attack and Stroke in Patients with Atherosclerosis (TRA2oP-TIMI 50) secondary prevention trial, 88%, 37%, and 28% of patients with symptomatic PAD were on aspirin, a thienopyridine agent, or aspirin+thienopyridine agents, respectively, at baseline.12 Furthermore, a prospective, multicenter registry study that evaluated the characteristics of 940 patients hospitalized with lower extremity PAD found that only 82% of patients were on antiplatelet treatment at discharge.13 Collectively, these data indicate that the use of aspirin or thienopyridine agents as secondary prevention agents among symptomatic PAD patients is not optimal. However, a critical review of antiplatelet trials (aspirin, thienopyridines, dipyridamole, prostanoids, and cilostazol) for symptomatic PAD highlights the fact that mortality rates remain high with antiplatelet treatment, and there is little effect on outcomes after PAD-related procedures.14 Better treatment options are needed, particularly as the prevalence of symptomatic PAD increases and it becomes a greater burden on the population and health care resources.

Limitations

The general limitations of retrospective database analyses, such as the potential for miscoding diagnoses or resource utilization procedures, apply to this analysis. In addition, the database does not contain information on risk indicators associated with CV- and PAD-related events, such as body mass index, smoking status, or family history, nor is information on ABI available to more specifically identify symptomatic PAD patients. Reasons for loss of insurance coverage (i.e., death) were also not captured in the database. A factor that may have influenced the magnitude of the differences observed in this analysis was that patients with stroke/TIA, bleeding complications, or contraindications to antiplatelet therapy were excluded from the symptomatic PAD population but not from the control population.

Because of the matching process, conclusions may not be generalizable to the overall symptomatic PAD population, since the symptomatic PAD patients selected for the match were, on average, healthier than the nonmatching symptomatic PAD patients as measured by CCI and the comorbidities tracked in this study. However, symptomatic PAD patients had more CV comorbidities in the pre-index period than control patients. One explanation for this difference is that the CCI is a composite of various disease states and is weighted based on the impact of the disease condition on patient morbidity and mortality. Serious conditions are weighted more. For instance, CV and PAD conditions for the most part had a weight of 1, whereas renal disease, liver disease, diabetes, and malignancies had weights that ranged from 2 through 4. It is, therefore, conceivable that symptomatic PAD patients could have had more CV comorbidity than the control patients while having similar CCI scores. Another explanation is that PAD is an atherothrombotic disease with a high likelihood of CV atherothrombotic comorbidity such as coronary heart disease or ACS.

Conclusions

Symptomatic PAD patients have higher medical resource use and costs when compared with a matched control population. As the prevalence of symptomatic PAD increases, there will be a negative impact on population health and health care system expenditures. The rates of utilization of evidence-based secondary prevention therapies, such as thienopyridines, were lower compared with what evidence-based guidelines would recommend. Therefore, greater efforts must be made to treat symptomatic PAD and related comorbidities according to guidelines to minimize the negative clinical and economic impact of symptomatic PAD.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Erin P. Scott, PhD, of Scott Medical Communications. This assistance was funded by Merck & Co., Kenilworth, New Jersey. Manuscript review and editorial support were also provided by Alan T. Hirsch, MD, and Sue Duval, PhD, from the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis.

References

- 1. Shammas NW.. Epidemiology, classification, and modifiable risk factors of peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3(2):229-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration, Fowkes FG, Murray GD, et al.. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(2):197-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diehm C, Allenberg JR, Pittrow D, et al.. Mortality and vascular morbidity in older adults with asymptomatic versus symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2009;120(21):2053-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allison MA, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al.. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):328-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al.. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toscani MR, Makkar R, Bottorff MB.. Quality improvement in the continuum of care: impact of atherothrombosis in managed care pharmacy. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(6 Suppl A):S2-12; quiz S13-16. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/data/jmcp/Novsupp1.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Margolis J, Barron JJ, Grochulski WD.. Health care resources and costs for treating peripheral artery disease in a managed care population: results from analysis of administrative claims data. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(9):727-34. Available at: http://amcp.org/data/jmcp/research_727-734.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mahoney EM, Wang K, Keo HH, et al.. Vascular hospitalization rates and costs in patients with peripheral artery disease in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(6):642-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahoney EM, Wang K, Cohen DJ, et al.. One-year costs in patients with a history of or at risk for atherothrombosis in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(1):38-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malyar N, Furstenberg T, Wellmann J, et al.. Recent trends in morbidity and in-hospital outcomes of in-patients with peripheral arterial disease: a nationwide population-based analysis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(34):2706-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, et al.. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease (updating the 2005 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(19):2020-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonaca MP, Scirica BM, Creager MA, et al.. Vorapaxar in patients with peripheral artery disease: results from TRA2{degrees}P-TIMI 50. Circulation. 2013;127(14):1522-29, 29e1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cambou JP, Aboyans V, Constans J, et al.. Characteristics and outcome of patients hospitalised for lower extremity peripheral artery disease in France: the COPART Registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(5):577-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azarbal A, Clavijo L, Gaglia MA Jr.. Antiplatelet therapy for peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia: guidelines abound, but where are the data? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20(2):144-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]