Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded health care and medication insurance coverage through Medicaid expansion in select states. Expansion has the potential to increase the availability of health services to patients, including prescription medications. However, limited studies have examined how expansion affected prescription drug utilization and reimbursement.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare prescription drug utilization (number of prescriptions filled) and reimbursement trends between states that did and did not expand Medicaid coverage in 2014, while accounting for known effects of expansion on Medicaid enrollment.

METHODS:

We conducted a comparative interrupted time series using retrospective Medicaid state drug utilization data from 2011 to 2014. After inclusion/exclusion criteria, 8 states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 and 10 states that did not expand Medicaid were studied. Primary outcomes were changes in quarterly prescription drug utilization and quarterly total prescription drug reimbursement before and after expansion. To account for increases in enrollment in expansion states, secondary outcomes were per-member-per-quarter (PMPQ) utilization and reimbursement before and after expansion.

RESULTS:

Expansion states experienced a 1.4 million prescriptions per quarter and $163 million per quarter increase in utilization and reimbursement above the change in rates observed in nonexpansion states after expansion (P < 0.001). Specifically, 1 year after ACA implementation, expansion states used 17.0% more prescriptions and spent 36.1% more in reimbursement than the quarter preceding expansion. Expansion and nonexpansion states experienced significant drops in PMPQ prescriptions immediately after expansion (P < 0.001), but PMPQ prescriptions and reimbursement trends increased by the end of the postexpansion period in expansion states (P < 0.029 and P < 0.001, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS:

Study results suggest that Medicaid expansion offers vulnerable patients who were previously uninsured increased access to health care resources, specifically prescription drugs. Although this hypothesis would benefit from further testing, it aligns with previous studies that have shown that Medicaid expansion has led to increased access to coverage and care. While enrollment contributes to the increase in prescription utilization and reimbursement, the drop in PMPQ utilization suggests that the patients entering the program are healthier than existing patients. This shows that risk pooling is working. However, the increase in PMPQ reimbursement suggests that new enrollment may not be the only factor driving reimbursement changes. Factors such as changes in product mix, risk pool composition, and drug pricing and their effects on total and per-member reimbursement should be evaluated in future studies.

What is already known about this subject

Medicaid expansion mandated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has the potential to increase the availability of health services to patients, including prescription medications.

In the United States, prescription drug spending has recently received significant attention and scrutiny by lawmakers, payers, and the public because of an unprecedented increase in national prescription drug expenditures, largely driven by the introduction of expensive specialty products and significant price hikes in marketed products.

What this study adds

Study results suggest that Medicaid expansion offers vulnerable patients who were previously uninsured increased access to health care resources, specifically to prescription drugs.

This study demonstrates that the growth in prescription utilization and reimbursement resulting from Medicaid expansion are driven by enrollment growth.

Adjusting for enrollment shows that per-member-per-quarter (PMPQ) utilization declined, suggesting that risk pooling may be working; however, increases in PMPQ reimbursement suggest that enrollment is not the only contributing factor to this growth.

The U.S. Medicaid program provides insurance to low-income adults and children, as well as to those with disabilities. The program is administered by each state but is funded through state and federal funds. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated that all states expand Medicaid eligibility to all nonelderly adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level.1 However, in 2012 the Supreme Court ruled that Medicaid expansion is optional.2 As a result, by 2016, 31 states had expanded Medicaid, 1 state was considering expansion, and 19 states were not expanding.3

Studies have demonstrated that expansion has increased insurance enrollment in Medicaid and subsequently decreased the uninsurance rate.4 Medicaid expansion through the ACA also has the potential to increase the availability of health services to patients, including prescription medications. In 2014, Medicaid paid for approximately 10% of all U.S. retail prescription drugs.5,6 While prescription drugs account for only a small proportion of Medicaid spending (5.5% in 2014), they totaled $20 billion after rebates in fiscal year 2014.7,8 Historically, U.S. stakeholders paid limited attention to prescription drug spending because it comprised a small proportion of national health care expenditures compared with hospital or physician spending.9 However, prescription drug spending has recently received significant attention and scrutiny by lawmakers, payers, and the public because of an unprecedented increase in national prescription drug expenditures, largely driven by the introduction of expensive specialty products and significant price hikes in marketed products.10 Because of this increase in expenditures, there is rising interest in understanding the effect of national policies on prescription drug access and spending. Examining changes in prescription drug use within Medicaid is especially important because total prescription drug expenditures increased by 23% in 2014, the highest yearly spending rate increase in the program since 1990.8,10,11

Selective expansion of state Medicaid programs allows for rigorous evaluations of the effect of Medicaid expansion on health services use as a natural experiment. While many studies have examined the short-term effects of Medicaid expansion on rates of insurance coverage, there is limited evidence of Medicaid expansion’s effect on prescription drug utilization and reimbursement.8,10,12-14

The purpose of this study was to compare access to outpatient prescription drugs as measured by prescription utilization and reimbursement trends between states that expanded and did not expand Medicaid coverage in quarter 1 of 2014. Specifically, we estimated total and per-member-per-quarter (PMPQ) utilization and reimbursement of prescription drugs to identify effects overall and per enrollee.

Methods

Data

We used the Medicaid state drug utilization data from 2011 to 2014 with a preexpansion period from January 2011 to December 2013, as well as a postexpansion period from January 2014 to December 2014. This data source captures every state’s data—including data for Washington, DC—for outpatient drugs covered under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.15 State Medicaid programs are required to submit data quarterly to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as part of reporting requirements for its Drug Utilization Review Program.16 The data include utilization (number of prescriptions filled), reimbursement (total amount reimbursed), and National Drug Code (NDC) numbers for each drug at the state level from 1992 to the present (with about a 6-month lag).17 NDC numbers were mapped to generic drug names. Approximately 0.4% of NDC numbers by utilization and 0.08% of NDC numbers by reimbursement were unable to be mapped.

We measured quarterly state Medicaid enrollment through 2 resources. Before 2014, the Kaiser Family Foundation contracted with Health Management Associates to collect point-in-time state-level Medicaid enrollment during June and December of each year.18,19 Beginning in 2014, CMS began collecting and publicly reporting monthly Medicaid enrollment at the state level.20 To create a measure of quarterly enrollment for each state before 2014, we assumed that the June enrollment would be reflected in the first 2 quarters of the year, and the December enrollment would be shown in the last 2 quarters of the year. From 2014 on, we averaged enrollment across the corresponding months for each quarter.

Selection of States

States were categorized into expansion or nonexpansion categories based on whether they expanded Medicaid during quarter 1, 2014.3 We excluded states that expanded early or late (i.e., before or after quarter 1, 2014) or with state-level insurance reform (e.g., Massachusetts; n = 14) and those states with prescription drug managed care programs that did not report prescription drug utilization and reimbursement data through the Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review Program before 2011 (n = 7).21 States were also excluded if they experienced unexplained variation in data reporting (or had missing data in 1 or more quarters) because of data quality concerns (n = 6). Finally, states with missing enrollment data were excluded (n = 6). State selection criteria are summarized in Table 1. After exclusions, 8 expansion states and 10 control states were included in this study.

TABLE 1.

Expansion, Managed Care, and Managed Care Reporting Status and Inclusion/Exclusion for All States and Washington DCa

| Expansion Status | States that Were Early Expanders/Late Expanders or had State-Level Reform | States with Managed Care Programs that Did Not Report Prescription Drug Data Before 2011 | States with Inconsistent Drug Data (Unexplained Variation and Missing Data) | States with Missing Enrollment Data | States Included in the Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion states | • Alaska • California • Connecticut • District of Columbia • Indiana • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • New Hampshire • New Jersey • Pennsylvania • Washington |

• Hawaii • New Mexico • West Virginia |

• Arizona • Illinois • Oregon |

• Colorado • Montana • Nevada • North Dakota • Rhode Island |

• Arkansas • Delaware • Iowa • Kentucky • Maryland • New York • Ohio • Vermont |

| Nonexpansion states | • Texas • Wisconsin |

• Florida • Kansas • Mississippi • Virginia |

• Maine • North Carolina • South Dakota |

• South Carolina | • Alabama • Georgia • Idaho • Louisiana • Missouri • Nebraska • Oklahoma • Tennessee • Utah • Wyoming |

aExclusion criteria are not mutually exclusive but based on the first confirmed exclusion criteria.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were changes in quarterly prescription drug utilization as measured by number of prescriptions and quarterly total prescription drug reimbursement from 2011-2014. The total amount reimbursed was the amount reimbursed to pharmacies and did not incorporate Medicaid rebates paid to the state.17 To account for changes in enrollment as a result of Medicaid expansion, we also calculated changes in PMPQ utilization and reimbursement as secondary outcomes for this study. All dollars were inflation-adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical Analysis

We used comparative interrupted time series (CITS) with Newey-West standard errors to evaluate the pre/post effect of Medicaid expansion in quarter 1, 2014, in expansion and nonexpansion states on the outcomes of interest.22,23 CITS (comparable to a difference-in-differences modeling approach) provides an estimate of the effect of expansion by comparing trends before and after expansion in the intervention group (expansion states) and explicitly accounts for differences observed in a control group over the same period (nonexpansion states). In this model, we included an indicator for each quarter in the study period from 1 to 16 (representing quarter 1, 2011, to quarter 4, 2014); an indicator for whether a state expanded Medicaid; and a postexpansion trend from 13 to 16 representing the expansion period from quarters 1-4, 2014. We also adjusted all regression models for seasonality by including indicators for the season of the year (spring, summer, fall, or winter). Further model details and interpretations are included in Appendix A, and additional results are provided in Appendix B (both available in online article). STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used to conduct this analysis.

Results

Total Utilization and Reimbursement

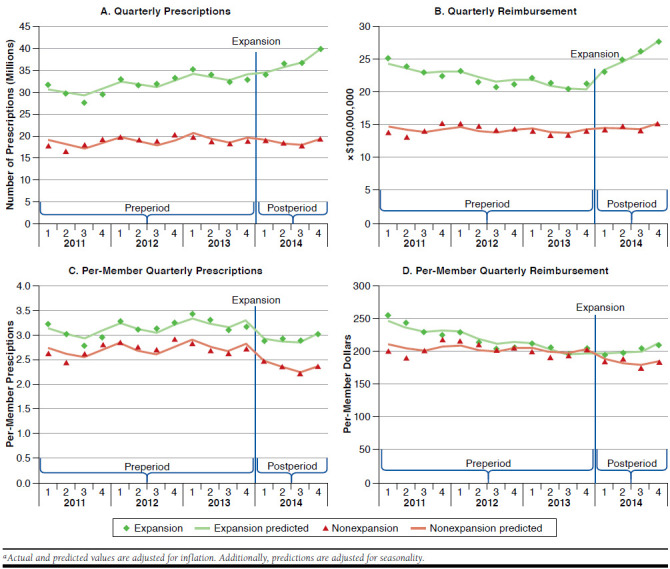

We begin by examining total prescription utilization and reimbursement to estimate the magnitude of the effect of Medicaid expansion. In the quarter before expansion (quarter 4, 2013), expansion states used about 33 million prescriptions, and nonexpansion states used about 19 million prescriptions (Figure 1A). After adjustment, expansion states had an increase in the predicted number of prescriptions by 17.0% in the fourth quarter of 2014 as compared with the fourth quarter of 2013. In contrast, nonexpansion states had a decrease of 2.0% in the predicted number of prescriptions over the same time period. Utilization trends were fairly parallel between expansion and nonexpansion states before the expansion period (P = 0.075). However, after expansion, expansion states experienced a steep increase in quarterly prescription utilization, while there was no change among nonexpansion states (Figure 1A). Specifically, the difference in the pre/post trends in expansion states was approximately 1.4 million prescriptions higher per quarter compared with nonexpansion states (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Expansion and Nonexpansion State Quarterly Trends in Utilization, Reimbursement, Per-Member Prescriptions and Per-Member Reimbursement (2011-2014)a

In the quarter before expansion, prescription reimbursement was approximately $2.1 billion in expansion states and $1.4 billion in nonexpansion states. When comparing changes in total prescription drug reimbursement from the last quarter of 2013 to the last quarter of 2014, we found that expansion states’ predicted reimbursements increased by 36.1% in contrast with a reduction of 6.3% in predicted reimbursement in nonexpansion states over the same period after adjustment.

Estimates from our interrupted time series model in Table 2 show that there was no statistically significant change in reimbursement in nonexpansion states between January 2011 and December 2014. In contrast, quarterly prescription reimbursements were decreasing in expansion states before expansion and increased in the period after expansion. Specifically, following Medicaid expansion, there was an immediate increase in reimbursement of approximately $285 million (P < 0.001), with subsequent increases of $163 million per quarter among expansion states relative to states that did not expand (P < 0.001; Figure 1B).

TABLE 2.

Changes in Quarterly Utilization, Reimbursement, Per-Member Utilization, and Per-Member Reimbursement by State Expansion Statusa

| Quarterly Utilization (Million Prescriptions) | P Value | Quarterly Inflation-Adjusted Reimbursement (USD Millions) | P Value | PMPQ Utilization | P Value | PMPQ Inflation-Adjusted Reimbursement | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline intercept in nonexpansion states | 18.986b (-0.845) | < 0.001 | 1468.440b (-58.741) | < 0.001 | 2.727b (-0.091) | < 0.001 | 212.100b (-7.038) | < 0.001 |

| Preexpansion trend in nonexpansion states | 0.169 (-0.100) | 0.106 | -1.969 (-6.718) | 0.771 | 0.018 (-0.011) | 0.126 | -0.680 (-0.815) | 0.413 |

| Expansion effect in nonexpansion states | -2.088c (-0.715) | 0.008 | 11.707 (-57.222) | 0.840 | -0.476b (-0.076) | <0.001 | -14.080 (-7.195) | 0.064 |

| Postexpansion trend change in nonexpansion states | 0.352 (-0.239) | 0.156 | 31.368 (-17.39) | 0.086 | -0.020 (-0.025) | 0.431 | -0.333 (-2.114) | 0.876 |

| Difference in baseline intercept in expansion states | 11.274b (-1.118) | < 0.001 | 996.537b (-72.549) | <0.001 | 0.376c (-0.117) | 0.004 | 39.490b (-8.493) | < 0.001 |

| Difference in preexpansion trend in expansion states | 0.266 (-0.142) | 0.075 | -29.891c (-8.614) | 0.002 | 0.008 (-0.015) | 0.578 | -3.699c (-0.995) | 0.001 |

| Difference in expansion effect in expansion states | 0.773 (-1.195) | 0.525 | 272.834b (-69.361) | 0.001 | -0.040 (-0.111) | 0.725 | 16.650d (-7.521) | 0.038 |

| Difference in postexpansion trend change in expansion states | 1.440b | < 0.001 | 162.767b | < 0.001 | 0.075d | 0.021 | 10.330b | < 0.001 |

aModels were also adjusted for seasonality. Model estimates were generated using comparative interrupted time series with Newey-West standard errors in parentheses.

bP < 0.001.

cP < 0.01.

dP < 0.05.

PMPQ = per member per quarter; USD = U.S. dollars.

PMPQ Utilization and Reimbursement

To examine the effect of the ACA on average reimbursement per patient, given the influx of new patients into Medicaid, we next examined PMPQ utilization and PMPQ reimbursement effects. In quarter 4, 2013, members in expansion states used approximately 3.17 prescriptions PMPQ, while members in nonexpansion state used approximately 2.74 prescriptions PMPQ. PMPQ utilization trends were similar between groups in the period before expansion (P = 0.578; Figure 1C). Both groups experienced drops in PMPQ utilization immediately after expansion (P < 0.001). However, PMPQ utilization began increasing in both groups by the end of 2014, with the difference in the pre/post trends being 0.075 PMPQ higher in expansion states than nonexpansion states (P = 0.021).

Similar to total reimbursement, PMPQ reimbursement was decreasing in the period before expansion and increased after the expansion period in expansion states (Figure 1D). The difference in trends in expansion states, before and after expansion, was statistically significant (P < 0.001). There was no difference over time in PMPQ reimbursement in nonexpansion states (P = 0.876). Furthermore, while there was a decrease in PMPQ reimbursement in the quarter immediately after expansion, it was not statically significant (P = 0.064). We also found that the difference in the pre/post trend in expansion states was approximately $10.33 higher reimbursement PMPQ compared with nonexpansion states (P < 0.001).

Discussion

We found that Medicaid expansion was associated with large increases in prescription drug use and reimbursement, which were partially driven by increased enrollment in Medicaid. Specifically, 1 year after ACA implementation, we estimated that in expansion states prescription drug use increased by 17.0%, and Medicaid reimbursement increased by 36.1%, compared with the quarter preceding expansion in the predictive model. In contrast, in nonexpansion states predicted use decreased by 2.0%, and predicted reimbursement grew by 6.3%.

In the period after expansion, the quarterly prescription trend remain unchanged from before the expansion period in nonexpansion states, which is unsurprising given that the population eligible for Medicaid did not change in these states, In contrast, the increased rate of prescriptions per quarter in the expansion states in the period after expansion suggests that Medicaid expansion offered new and vulnerable patients, who were previously uninsured, increased access to prescription drugs. Although this hypothesis could benefit from further testing, it aligns with previous studies that have shown that Medicaid expansion has led to increased access to coverage and care.4,14,24 Our specific findings, related to prescription drug use and reimbursement, also align with the findings from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiments, where patients who enrolled in Medicaid had higher prescription drug reimbursement than those who did not enroll in the first year.25,26 Access to prescription drugs is important, since it may result in downstream cost savings in other health services. For example, early and continuous human immunodeficiency virus care, one of the most vulnerable Medicaid subpopulations, can save up to $338,400 (discounted) over a lifetime.27 It is also estimated that every $1 spent on substance abuse treatment saves $4 in health care costs, offering states and the federal system a significant return on investment.28 Mirroring the utilization trends, quarterly reimbursement increased in expansion states and remained unchanged in nonexpansion states in the period after expansion compared with the period before the expansion.

By examining PMPQ utilization and reimbursement, we assessed the effect of the ACA on utilization and reimbursement while controlling for enrollment changes. The immediate decline in PMPQ utilization trends in expansion states in the quarter after expansion suggests that risk pooling is working with the introduction of new healthy patients into the program. Before expansion, PMPQ reimbursement trends were decreasing in nonexpansion states but increasing in expansion states, suggesting that enrollment is not the only factor contributing to this growth. Another factor may be changes in the product mix, for example, the introduction of new products such as sofosbuvir, the expensive cure for hepatitis C virus in late 2013.29 Additionally, there have been Medicaid price hikes in commonly used products such as insulin and albuterol.30,31 Evaluating the reimbursement and utilization drivers of Medicaid spending is an important topic for future work.

Similar to our analysis, previous studies and reports have estimated that Medicaid prescription expenditures increased by 24.3% in the whole population, 24.6% among expansion states, and 14.1% in nonexpansion states between 2013 and 2014.8,10 Furthermore, it has been estimated that expansion states and nonexpansion states increased the number of Medicaid prescriptions by 25.4% and 2.8%, respectively.12 This study adds to this growing body of literature by examining the effect of Medicaid expansion on prescription drug use and reimbursement trends over time.

Additionally, there are 3 methodological strengths to this study. First, in examining the effect of expansion, we limited the analyses to only states that expanded in 2014, since those states with earlier expansion or state-level reform may have had other state-level effects that could have influenced the outcomes of interest. Second, we examined the change in utilization and reimbursement trends over time, not just the total utilization and reimbursement before and after expansion, to support that the effects we saw after expansion were a result of this policy, accounting for history and maturation. Third, by using comparative interrupted time series methods, we accounted for time invariant unobservable variables when the pretrends were similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, thereby improving the internal validity of this study.

Limitations

Limitations of this work include potentially limited generalizability to states that were excluded from the analysis because of early expansion, managed care states that were not collecting rebates, or data quality concerns. Second, it is recommended that interrupted time series have at least 12 postintervention time periods. However, this study was limited to 4 quarters after expansion, given the limited time that the ACA had been in effect. Third, the parallel trends assumption may not have been met statistically for some outcomes in the period before expansion. However, visual examination of these trends demonstrates that the pretrends appear parallel, with the exception of PMPQ reimbursement. Fourth, the enrollment data used as the denominator for the PMPQ analyses came from 2 different data sources, which may cause measurement bias in assessing pre/post trends; however, this data use should not affect differences in trends between expansion and nonexpansion states. Finally, reimbursement data represented the total amount that Medicaid spent and did not account for rebates and other discounts.

Conclusions

Medicaid expansion led to early increases in use and reimbursement of prescription drugs in excess of what would be expected because of increased enrollment alone. Other factors, such as changes in risk pool, drug mix, and price hikes, may contribute to increased use and reimbursement of prescription drugs. These are topics that should be explored in future studies. Forthcoming studies should also consider looking at the effects of Medicaid expansion on health outcomes and the long-term effects of expansion on prescription drug reimbursement and utilization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Ashley Cole and Robert Overman for their assistance with data management and programming.

APPENDIX A. Comparative Interrupted Time Series (CITC) Model Comparing Outcomes Pre/Post Expansion in 2014 in Expansion Versus Nonexpansion States

| Regression Equation: Yt = β0 + β1Timet + β2Interventiont + β3Interventiont × Timet + β4Treatment + β5Treatment × Timet + β6Treatment × Intervention + β7Treatment × Interventiont × Timet + β8Quarter2 + β9Quarter3 +β10Quarter4 + Et | |

|---|---|

| Coefficient | Description21 |

| Control (nonexpansion states) | |

| Baseline intercept (B0) | The intercept, or starting level of the outcome variable |

| Pre-expansion trend (B1) | The slope, or trajectory of the outcome variable until the introduction of the intervention |

| Expansion (B2) | The change in the level of the outcome that occurs in the period immediately following the introduction of the intervention |

| Expansion-trend (B3) | The difference between pre- and postintervention slopes of the outcome |

| Treatment (expansion states) | |

| Baseline intercept (B4) | The difference in the level (intercept) of the outcome variable between treatment and controls prior to the intervention |

| Trend (B5) | The difference in the slope (trend) of the outcome variable between treatment and controls prior to the intervention |

| Expansion (B6) | The difference between treatment and control groups in the level of the outcome variable immediately following introduction of the intervention |

| Expansion-trend (B7) | The difference between treatment and control groups in the slope (trend) of the outcome variable after initiation of the intervention compared to pre-intervention (akin to a difference-in-differences of slopes) |

| Seasonality (reference category: quarter 1, January-March) | |

| Quarter 2 (B8) | April-June |

| Quarter 3 (B9) | July-September |

| Quarter 4 (B10) | October-December |

APPENDIX B. Changes in Quarterly Utilization, Reimbursement, Per-Member Utilization, and Per-Member Reimbursement by State Expansion Status: Full Modela

| Quarterly Utilization (Million Prescriptions) | P Value | Quarterly Inflation-Adjusted Reimbursement (USD Millions) | P Value | PMPQ Utilization | P Value | PMPQ Inflation-Adjusted Reimbursement | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline intercept in nonexpansion states | 18.986b (-0.845) | < 0.001 | 1468.440b (-58.741) | < 0.001 | 2.727b (-0.091) | < 0.001 | 212.100b (-7.038) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-expansion trend in nonexpansion states | 0.169 (-0.100) | 0.106 | -1.969 (-6.718) | 0.771 | 0.018 (-0.011) | 0.126 | -0.680 (-0.815) | 0.413 |

| Expansion effect in nonexpansion states | -2.088c (-0.715) | 0.008 | 11.707 (-57.222) | 0.840 | -0.476b (-0.076) | < 0.001 | -14.080 (-7.195) | 0.064 |

| Postexpansion trend change in nonexpansion states | 0.352 (-0.239) | 0.156 | 31.368 (-17.39) | 0.086 | -0.020 (-0.025) | 0.431 | -0.333 (-2.114) | 0.876 |

| Difference in baseline intercept in expansion states | 11.274b (-1.118) | <0.001 | 996.537b (-72.549) | < 0.001 | 0.376c (-0.117) | 0.004 | 39.490b (-8.493) | <0.001 |

| Difference in preexpansion trend in expansion states | 0.266 (-0.142) | 0.075 | -29.891c (-8.614) | 0.002 | 0.008 (-0.015) | 0.578 | -3.699c (-0.995) | 0.001 |

| Difference in expansion effect in expansion states | 0.773 (-1.195) | 0.525 | 272.834b (-69.361) | 0.001 | -0.040 (-0.111) | 0.725 | 16.650d (-7.521) | 0.038 |

| Difference in postexpansion trend change in expansion states | 1.440b (-0.316) | < 0.001 | 162.767b (-22.775) | < 0.001 | 0.075d (-0.03) | 0.021 | 10.330b (-2.397) | < 0.001 |

| Quarter 2 | -1.271d (-0.483) | 0.016 | -45.862 (-36.675) | 0.225 | -0.147c (-0.048) | 0.006 | -5.096 (-4.375) | 0.257 |

| Quarter 3 | -2.261c (-0.604) | 0.001 | 78.904d (-31.849) | 0.225 | -0.242b (-0.056) | < 0.001 | -8.358d (-3.61) | 0.031 |

| Quarter 4 | -1.347 (-0.714) | 0.073 | -28.852 (-44.021) | 0.519 | -0.121 (-0.072) | 0.104 | -1.211 (-5.278) | 0.821 |

aNewey-West standard errors are provided in parentheses under the estimate.

bP < 0.001.

cP < 0.01.

dP < 0.05.

PMPQ = per-member-per-quarter; USD = U.S. dollars.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 42 USC § 18001 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Federation of Independent Business et al. v Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services, et al., 567 US (2012). Available at: https://www.oyez.org/cases/2011/11-393. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 3.Kaiser Family Foundation.. State health facts. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. 2016. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/#notes. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 4.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S.. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: findings from a literature review. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 20, 2016. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-findings-from-a-literature-review/. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.. National Health Expenditure Table 16: Retail prescription drugs expenditures; levels, percent change, and percent distribution, by source of funds: selected calendar years 1970-2014. [Author analysis] Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation.. Health insurance coverage of the total population. 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.. National Health Expenditure Table 4. National health expenditures by source of funds and type of expenditures: calendar years 2008-2014. [Author analysis] Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 8.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.. Medicaid spending for prescription drugs. Issue Brief. January 2016. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Medicaid-Spending-for-Prescription-Drugs.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 9.Hartman M, Martin AB, Lassman D, Catlin A.. National health spending in 2013: growth slows, remains in step with the overall economy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):150-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, Catlin A.. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):50-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.. Medicaid payment for outpatient prescription drugs. Issue Brief. September 2015. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Medicaid-Payment-for-Outpatient-Prescription-Drugs.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 12.IMS Institute.. Medicines use and spending shifts: a review of the use of medicines in the U.S. in 2014. April 2015. Available at: https://www.redaccionmedica.com/contenido/images/IIHI_Use_of_Medicines_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 13.Garfield R, Damico A, Cox C, Claxton G, Levitt L.. New estimates of eligibility for ACA coverage among the uninsured. Kaiser Family Foundation. Updated January 2016. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/data-note-new-estimates-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-uninsured. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 14.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T.. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicaid.gov. Prescription drugs. 2014. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 16.Medicaid.gov. Drug utilization review. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/benefits/prescription-drugs/drug-utilization-review.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 17.Medicaid.gov. State drug utilization data. Web file structure and definitions. 2015. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 18.Snyder L, Rudowitz R, Ellis E, Roberts D.. Medicaid enrollment snapshot: December 2013. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 3, 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-snapshot-december-2013/. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 19.Snyder L, Rudowitz R, Ellis E, Roberts D.. Medicaid enrollment: June 2013 data snapshot. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 29, 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-june-2013-data-snapshot/. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 20.Medicaid.gov. Medicaid enrollment data collected through MBES. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-enrollment-data-collected-through-mbes.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General.. States’ collection of rebates for drugs paid through Medicaid managed care organizations. OEI-03-11-00480. September 2012. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-11-00480.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 22.Linden A. Conducting interrupted time series analysis for single and multiple group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15:480-500. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D.. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wherry LR, Miller S.. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al.. The Oregon experiment— effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. New Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al.. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schackman BR, Fleishman JA, Su AE, et al.. The lifetime medical cost savings from preventing HIV in the United States. Med Care. 2015;53(4):293-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ettner SL, Huang D, Evans E, et al.. Benefit-cost in the California treatment outcome project: does substance abuse treatment “pay for itself”? Health Serv Res. 2006;41(1):192-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Food and Drug Administration.. News release. FDA approves sovaldi for chronic hepatitis C. December 6, 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm377888.htm. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 30.Luo J, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS.. Trends in Medicaid reimbursements for insulin from 1991 through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1681-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiske CP, Ogbechie OA, Schulman KA.. Options to promote competitive generics markets in the United States. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2129-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]