Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The U.S. health care system is currently evolving from a volume-based care to a value-based care approach, which is in part supported by the introduction of patient support programs (PSP). For patients treated with adalimumab (ADA), the addition of a dedicated, trained nurse to the PSP (HUMIRA Complete, rolled out nationally in 2015) provides further emphasis on value-based care.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the effectiveness of the HUMIRA Complete PSP, including the Nurse Ambassador component, in a real-world setting for patients receiving ADA across a broad range of approved indications (rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa).

METHODS:

A longitudinal retrospective study was conducted using patient-level data from the HUMIRA Complete PSP data linked to the real-world, patient-level Symphony Health Solutions administrative claims database. Commercially insured patients were included who were aged ≥ 18 years with ≥ 2 diagnoses of an indicated disease who were biologically naive before initiating ADA or who had no claims for synthetic-targeted immune modulator therapy before their earliest ADA claim in the database between January 2015 and February 2017. The first claim had to have occurred in 2015 or later, and continuous medical and drug data coverage were required for ≥ 6 months before and ≥ 12 months after the first ADA claim and index date. PSP patients (with at least an initial and follow-up dedicated nurse call) were matched 1:1 to non-PSP patients based on pharmacy type, indication, and propensity score, estimated with covariates for age, sex, year of first ADA use, and baseline comorbidities. Adherence to ADA was compared using proportion of days covered along with discontinuation of ADA, defined as a gap in treatment greater than the previous days supply with no additional ADA claim, total costs, medical costs, and drug costs (2017 U.S. dollars) over 12 months. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized descriptively. Differences between cohorts were assessed using t-tests for adherence and costs and log-rank tests for discontinuation.

RESULTS:

2,268 patients (1,134 per group) were included. Baseline characteristics were similar between cohorts after matching. Participation in the PSP was associated with 29.3% higher ADA adherence (64.8% vs. 50.1%; P < 0.0001) and 22.0% lower ADA discontinuation rate (51.4% vs. 65.9%; P < 0.0001). Disease-related medical costs and all-cause medical costs were significantly lower by 35% ($10,162 vs. $15,511; P = 0.005) and 29.2% ($25,074 vs. $35,419; P = 0.0004), respectively, for PSP versus non-PSP patients. Total costs were also lower by 9% ($62,421 vs. $68,706; P = 0.056), and drug costs were 12.2% higher ($37,347 vs. $33,287; P = 0.0016).

CONCLUSIONS:

This retrospective study demonstrates that participation in the PSP augments value-based care by improving outcomes for patients with chronic diseases by helping them not only manage a complex treatment regimen but also lower annual health care costs.

What is already known about this subject

Many drug manufacturers have begun offering patient support programs (PSPs) to provide education and adherence support for patients.

Evidence has suggested that PSPs improve clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes for patients.

There is currently a paucity of real-world evidence on the effect of PSPs for patients receiving biologic therapies.

What this study adds

This study uses real-world data to evaluate patient outcomes associated with participation in a PSP for a biologic therapy.

This study provides evidence that participation in the unique and innovative adalimumab PSP adds significant value to the treatment of patients across a range of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases by lowering total medical costs and significantly increasing adherence to treatment.

Despite per capita expenditure in the United States being among the highest in the world, health care performance is not aligned.1-3 Health care costs rose from $1.2 trillion to $2.1 trillion between 1996 and 2013 and accounted for 17.3% of the national economy in 2015.4 In responding to these challenges, the U.S. health care system is increasingly shifting from volume-based to value-based care, a reimbursement strategy that is continuing to gain momentum across the health care spectrum, including payers, policymakers, and health professionals, following the introduction of the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act in 2008 and, subsequently, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010.3,5,6 This change in reimbursement from a volume-based approach enhances the 3 main pillars of the ACA: a more patient-centered approach with greater patient satisfaction, better health outcomes for patients, and, ultimately, improved health of the overall population.7,8

The changing approach to value-based care could be of particular benefit to patients with long-term chronic diseases who historically have high rates of abandonment (i.e., failure to initiate therapy or refill prescriptions, which can be higher with biologic therapies9-11), with rates of treatment adherence of approximately 40%.12 Due to the typically long-term management of chronic therapy, approximately half of patients do not take their medications as prescribed, leading to poor clinical outcomes and an increase in economic and societal burden of disease.13-16

Different strategies for improving patient outcomes, including education and motivational interview programs to allow behavioral modification, have been explored, are continuing to evolve, and have been proved to improve quality of life for patients with chronic diseases.17-19 More recently, the introduction of patient support programs (PSPs) has been adopted to provide education and communication to improve adherence in patients with chronic disease.20 Historically, PCPs have been self-management support programs, which included medication counseling, training, and virtual reminders to support patients and help improve medication-taking behavior.20 A targeted systematic review indicated that PSPs have a positive effect on clinical (e.g., medication adherence and persistence); humanistic (e.g., quality of life and function); and economic (e.g., cost or utilization-related) outcomes.20 However, this review was performed primarily in patients with diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, and cardiovascular disease and included many studies that evaluated the benefits of PSPs in a small clinical setting.

Although the evolution of biologic therapies has provided significant benefit to patients with chronic autoimmune disease, namely improved quality of life, reduced extra-articular complications, and, in some cases, clinical remission,21-24 payers face considerable challenges in delivering quality of care while at the same time reducing health care spending. Nonadherence rates across medications encompassing all disease conditions are around 25%,25 considerably lower than the average nonadherence rate for patients receiving antitumor necrosis factor therapies of between 28% and 52%.26 Improving patient adherence to biologics could reduce overall medical costs (despite an increase in drug costs) and make considerable advances in moving to a value-based care approach.27 Evaluation of the overall effect of PSPs on clinical and economic outcomes in patients with autoimmune diseases, which are often debilitating and have a significant effect on quality of life, is therefore needed.

HUMIRA Complete (adalimumab [ADA] PSP, AbbVie, North Chicago, IL) is a unique PSP offered by AbbVie, a manufacturer of ADA, at a national level across all ADA-approved indications (rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa). This program is designed to provide one-to-one, personalized support to increase medication adherence by behavior modification and provides the ability to evaluate a PSP on a large scale. Further, patient-level ADA PSP enrollment records have been linked directly to real-world claims data using a proprietary deidentification engine to generate universal patient identifiers, providing a unique opportunity to assess how patient outcomes are associated with participation in a PSP for the treatment of chronic diseases. Patients participating in the ADA PSP are assigned a dedicated Nurse Ambassador, a registered nurse trained to provide disease, product, and drug access education, in an effort to empower patients to adhere to their prescribed treatment plan.

Rolled out nationally in 2015, the team of Nurse Ambassadors include more than 400 registered nurses who provide unique, high-touch, coordinated care for ADA patients not replicated by other PSPs. The Nurse Ambassador supplements preexisting components of the PSP, including assistance navigating the insurance and financial assistance process; education on keeping ADA at the required temperature with resources for patients traveling short distances; and reminders to take medication through phone, text, and/or email. The current version of the ADA PSP has enrolled more than 300,000 patients since 2015. There is no fee associated with program enrollment.

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effect of the current PSP, including the Nurse Ambassador component, in a real-world setting by comparing adherence, discontinuation, and medical costs for patients participating in the comprehensive ADA PSP versus non-PSP participants, between January 2015 and February 2017 in a large, nationally representative sample of commercially insured patients who were receiving ADA treatment across a broad range of approved indications.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

In this longitudinal, retrospective cohort study, the ADA PSP data were linked to real-world, patient-level claims data from the Symphony Health Solutions (SHS) administrative claims database. The SHS database is a longitudinal collection of patient-level claims data that covers all U.S. payers and more than 280 million people in recent years. The SHS database contains patient-level data on medical and pharmacy claims from a large, geographically diverse set of electronic claims processors across the United States and includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes, dates of service, charge amounts, procedure codes, National Drug Code numbers, and pharmacy types.

For this study, claims were available from January 2006 through February 2017. PSP data are collected through an integrated coordinated care platform and include records of enrollment and use of PSP program elements, including Nurse Ambassador interactions. A proprietary deidentification engine (Synoma, Symphony Health, Phoenix, AZ) was used by each data provider to generate unique patient tokens based on identifiable information that was removed from the data provided to researchers, allowing for direct patient linking between the PSP records and claims. A series of pseudonymized patient tokens were created within the PSP data provider environment using a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)-compliant industry standard encryption engine allowed for linking of patient tokens across datasets. This provided an opportunity, which has not previously been explored, to evaluate how patient outcomes are associated with participation in a PSP for the treatment of chronic diseases.

Any risk associated with linked data content was evaluated by an external HIPAA statistician who certified patient anonymity of the resulting files. Because deidentification was conducted before providing claims to SHS and PSP records to researchers, and no identifiable protected health information was included in data used, this study was determined as exempt from institutional review board approval.

Study Population

Eligibility Criteria.

Patients from a commercial population were eligible for inclusion if they were aged ≥ 18 years, if they had initiated ADA treatment between January 2015 and February 2017, and if they had no claims for biologic or synthetic-targeted immune modulator therapy before their earliest ADA claim in the database. To ensure that patients with biologic or synthetic-targeted immune modulator treatment experience before initiating ADA were excluded, all claims from January 2006 through the first ADA claim were considered. Patients were also excluded if they had government-provided insurance, since they were ineligible for the financial assistance component of the PSP. The index date was defined as the date of PSP enrollment for PSP patients. The length of time between the initial ADA claim and PSP enrollment for PSP patients was used to calculate the index date for matched controls, as described below. The 6-month period before the index date was considered the baseline period, and the 12-month period beginning with the index date was considered the follow-up period.

Claims Criteria.

Each patient was required to have ≥ 2 claims at least 30 days apart with ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for any ADA indication (rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa). Further information on the codes is provided in the Appendix (available in online article). The first ADA claim must have occurred in 2015 or later, and evidence of continuous medical and drug data coverage was required for ≥ 6 months before and ≥ 12 months after the first ADA claim (or index date, if different).

SHS Data Coverage.

There was no enrollment or eligibility file for the SHS data; however, to mitigate concerns about data completeness, periods of continuous data coverage were required based on observed frequency of medical and drug claims using previously developed algorithms.28 These algorithms to determine data coverage were developed separately for medical and drug claims by assessing gaps in consecutive claims that were predictive of potentially incomplete data. Patients were considered to have continuous medical data coverage if the interval between any 2 consecutive medical claims was no more than 120 days apart during the study period, and patients were considered to have continuous drug data coverage if the interval between any 2 consecutive drug dispensing records was no more than 60 days apart during the study period.28 Other studies of adherence and clinical events using the SHS database have similarly defined periods of continuous data coverage for each patient based on the frequency of observed claims.29,30

Cohort Assignment and Matching Process.

Patients who met eligibility criteria were categorized into 2 cohorts: the PSP cohort and the non-PSP cohort. Patients who opted in to the PSP and engaged with a Nurse Ambassador through an initial and follow-up call were assigned to the PSP cohort, and the date of initial PSP opt-in was used as the index date. Patients who opted in to the PSP but did not follow through to engage with a Nurse Ambassador were excluded from the study. The non-PSP cohort included patients who did not opt in to any component of the PSP. PSP patients were matched 1:1 to non-PSP patients, based on use of a specialty/mail order or other pharmacy type for initial ADA claim, ADA indication, and propensity scores estimated using a logistic regression of opt-in to the PSP with covariates for age, sex, year of initial ADA claim, and specific comorbidities (Table 1). To construct a control cohort of non-PSP patients while limiting PSP sample loss, a nearest-neighbor matching process was used in which a single non-PSP patient was matched to each PSP patient.31 Matching with replacement was allowed to minimize bias from the matching process.32-34 The index date for a non-PSP patient was based on the time from ADA initiation to PSP opt-in for the matched PSP patient (e.g., if the PSP patient opted in to the program 5 days after ADA initiation, then the matched control was assigned an index date 5 days after his or her ADA initiation).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographic Information, Baseline Comorbidities,a and Baseline Costs

| PSP Cohort | Non-PSP Cohort | P Value b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patientsc | 1,134 | 1,134 | – |

| Age, years, mean ± SD (median) | 50.4 ± 11.5 (53.0) | 50.4 ± 12.4 (52.0) | 0.975 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 338 (29.8) | 331 (29.2) | 0.747 |

| Female | 796 (70.2) | 803 (70.8) | 0.747 |

| Time to opt-in, days, mean ± SD (median) | 2.5 ± 15.6 (0.0) | 2.5 ± 15.6 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Primary indication, n (%)d | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 469 (41.4) | 469 (41.4) | 1.000 |

| Crohn’s disease | 221 (19.5) | 221 (19.5) | 1.000 |

| Psoriasis | 162 (14.3) | 162 (14.3) | 1.000 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 150 (13.2) | 150 (13.2) | 1.000 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 76 (6.7) | 76 (6.7) | 1.000 |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | 23 (2.0) | 23 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 19 (1.7) | 19 (1.7) | 1.000 |

| Uveitis | 14 (1.2) | 14 (1.2) | 1.000 |

| Calendar year of index date, n (%) | |||

| 2015 (January-December) | 1,017 (89.7) | 1,013 (89.3) | 0.784 |

| 2016 (January-February) | 117 (10.3) | 121 (10.7) | 0.784 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ± SD (median) | 0.82 ± 1.03 (1.0) | 0.75 ± 1.01 (1.0) | 0.099 |

| Comorbidities, n (%)d | |||

| Hypertension | 333 (29.4) | 275 (24.3) | 0.006 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 251 (22.1) | 254 (22.4) | 0.880 |

| Diabetes mellitus, type 2 | 160 (14.1) | 143 (12.6) | 0.294 |

| Comorbidities, n (%)d | |||

| Depression | 134 (11.8) | 120 (10.6) | 0.351 |

| Sinusitis | 101 (8.9) | 96 (8.5) | 0.709 |

| Asthma | 71 (6.3) | 94 (8.3) | 0.063 |

| Other ischemic heart disease | 45 (4.0) | 46 (4.1) | 0.915 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 40 (3.5) | 40 (3.5) | 1.000 |

| All cancers | 40 (3.5) | 32 (2.8) | 0.338 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 29 (2.6) | 25 (2.2) | 0.582 |

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 20 (1.8) | 9 (0.8) | 0.040 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 13 (1.1) | 12 (1.1) | 0.841 |

| Skin cancer | 9 (0.8) | 9 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8 (0.7) | 5 (0.4) | 0.404 |

| Liver disease | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.3) | 0.205 |

| Atherosclerosis | 5 (0.4) | 9 (0.8) | 0.284 |

| Chronic renal disease | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0.102 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.025 |

| Lymphoma | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.317 |

| Baseline costs,e mean ± SD (median), $ | |||

| Total costs | 14,999 ± 26,324 (7,324) | 17,255 ± 32,904 (7,201) | 0.072 |

| Medical costs | 12,263 ± 25,296 (4,517) | 14,542 ± 31,947 (4,429) | 0.060 |

| Drug costs | 2,735 ± 4,450 (1,120) | 2,713 ± 6,579 (906) | 0.924 |

Data source: Symphony Health Solutions claims database, 2015-2017.

aComorbidities evaluated in the 6 months before index date.

bPSP cohort versus non-PSP cohort.

cMatched 1:1 with replacement.

dPrimary indication was based on the most recent autoimmune diagnosis before initiating adalimumab.

eCosts were evaluated in the 6 months before the index date and were calculated using the service charge for medical claims and the primary plan payment amount for prescriptions.

PSP = patient support program; SD = standard deviation.

Outcomes

The primary study outcomes were measures of adherence to and discontinuation of ADA and health care costs, including medical, drug, and total cost (medical and drug cost), during the 12-month period following the index date. Disease-related medical, drug, and total costs were also reported. Disease-related medical costs were calculated from claims with a diagnosis for the ADA indication of each patient and drug costs consisted of claims for biologic or synthetic-targeted immune modulator therapy.

Adherence was defined as the proportion of days covered: the sum of the number of days covered by the reported days supply of ADA pharmacy claims divided by the total number of days in the 12-month follow-up period. Discontinuation of ADA was measured with the discontinuation rate and time to discontinuation. Patients were considered to have discontinued ADA if they switched to another biologic medication or had an ADA treatment gap that exceeded the days of supply on their last ADA claim with no further ADA prescriptions during the 12-month follow-up period.

Health care costs were captured from billing transactions submitted to payers by hospitals, pharmacies, and physicians. For medical claims, these costs included service charges submitted to the payer; for pharmacy claims, these represented costs to the primary payer. All costs were adjusted to 2017 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index. Medical costs included emergency department, inpatient, physician (i.e., medical office); outpatient (e.g., hospital outpatient, laboratory, intermediate care facility); and other visits (e.g., home health, unknown), excluding biologic and synthetic-targeted immune modulator costs. Drug costs included biologic and synthetic-targeted immune modulator costs (abatacept, ADA, anakinra, apremilast, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, natalizumab, rituximab, secukinumab, tocilizumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab), covered by medical and pharmacy benefits and any other prescription costs.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the 6 months before the index date were summarized using descriptive statistics. Differences in baseline characteristics between the PSP and non-PSP cohorts were assessed using Student t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. For continuous variables, Welch’s t-test (or the Satterthwaite approximation) was used if the F test determined variances were unequal between groups.

ADA adherence and direct medical costs were compared between cohorts using t-tests. Time to ADA discontinuation was compared between cohorts using log-rank tests from Kaplan-Meier analysis. Statistical significance was based on a 2-sided alpha error level of 0.05 in all analyses. Univariate and Kaplan-Meier analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample

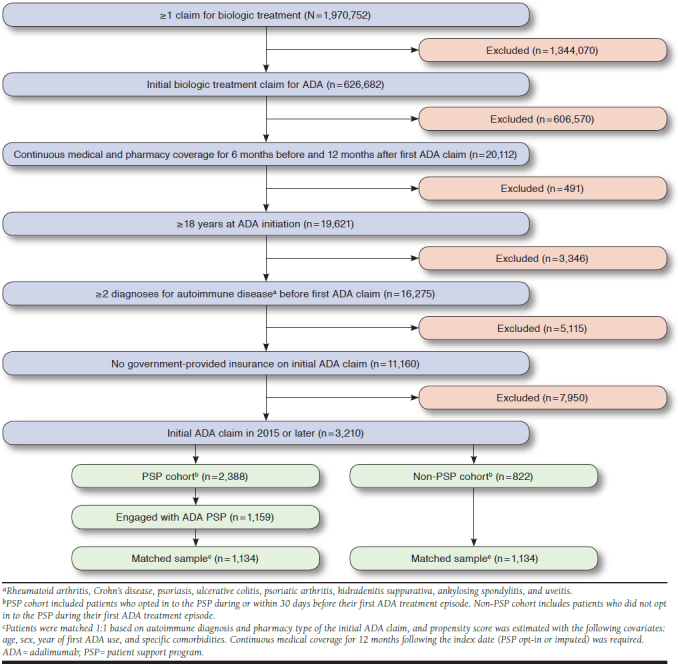

A total of 3,210 patients met the study inclusion criteria (Figure 1): 2,388 patients in the PSP cohort and 822 patients in the non-PSP cohort. Within the PSP cohort, 1,159 patients opted in to the Nurse Ambassador program and followed through with an initial and follow-up call, and 1,134 were matched to a non-PSP patient. Matching was conducted with replacement, in which the non-PSP patient with the nearest propensity score was selected for each PSP patient and a given non-PSP patient could be matched multiple times, resulting in a cohort of 1,134 non-PSP patients from the 822 unique non-PSP patients meeting the inclusion criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Selection of Study Population

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and were similar between the PSP and non-PSP cohorts. The mean age of the study population was 50.4 years, and approximately 70% of the patient population was female. The most common indications for ADA treatment in both cohorts were rheumatoid arthritis (41.4% of patients), Crohn’s disease (19.5%), psoriasis (14.3%), and ulcerative colitis (13.2%). Most patients in the PSP cohort (92%) had an opt-in date on or before the date of ADA initiation, and more than 98% of patients opted in to the program within 30 days of ADA initiation.

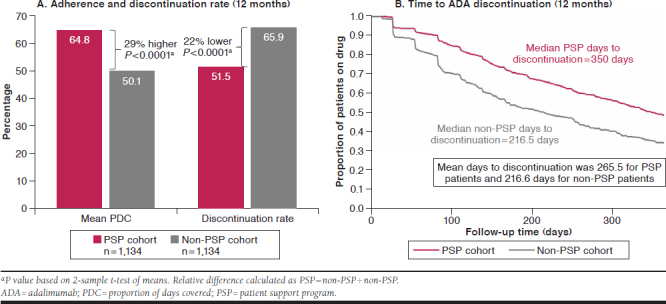

Adherence and Discontinuation

During the 12-month follow-up period, patients in the PSP cohort demonstrated significantly greater ADA adherence (64.8% vs. 50.1%, P < 0.0001; 29% greater) and lower discontinuation rates (51.4% vs. 65.9%, P < 0.0001; 22% lower) than patients in the non-PSP cohort (Figure 2A). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of PSP patients achieved the 80% adherence threshold than non-PSP patients (43.7% vs. 25.7%; P < 0.001). A lower proportion of PSP patients switched to another treatment (20.6% vs. 28.5%; P < 0.001) or discontinued treatment entirely (30.8% vs. 37.4%; P < 0.001) during the 12-month follow-up period. Patients in the PSP cohort remained on ADA treatment significantly longer than non-PSP patients; median number of days to ADA discontinuation was 133.5 days longer for PSP than non-PSP (350.0 vs. 216.5 days, P < 0.0001; 62% longer); mean number of days to ADA discontinuation was 48.9 days longer for PSP than non-PSP (265.5 vs. 216.6 days, P < 0.0001; 23% longer; Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Adherence, Discontinuation, and Time to Discontinuation

Health Care Cost

Health care costs at baseline were similar for PSP and non-PSP patients (Table 1); however, for the 12-month follow-up period, all-cause medical costs (excluding costs for biologics and synthetic-targeted immune modulators) were 29% lower for PSP than for non-PSP patients ($25,074 vs. $35,419; P < 0.001; Table 2). Disease-related medical costs were also significantly lower and total costs were lower for PSP than for non-PSP patients: 35% ($10,162 vs. $15,511; P = 0.005) and 9% ($62,421 vs. $68,706; P = 0.056), respectively (Table 2). The main driver of lower all-cause and disease-related medical costs in the PSP cohort was a statistically significant reduction in inpatient costs versus non-PSP patients ($3,687 vs. $7,799; P = 0.002, and $2,008 vs. $5,064; P = 0.003; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Costs in Study Perioda

| PSP Cohort | Non-PSP Cohort | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1,134 | 1,134 | – |

| Total costs (medical + drug), $ | 62,421 ± 73,221 (51,202) | 68,706 ± 82,701 (52,223) | 0.056 |

| Medical costs, $c | |||

| Overall | 25,074 ± 63,087 (8,544) | 35,419 ± 74,704 (11,053) | < 0.001 |

| Emergency department | 6,227 ± 39,405 (0) | 9,875 ± 44,277 (0) | 0.038 |

| Inpatient | 3,687 ± 18,589 (0) | 7,799 ± 40,437 (0) | 0.002 |

| Physician | 4,658 ± 13,502 (2,537) | 4,294 ± 5,954 (2,800) | 0.407 |

| Outpatient | 9,272 ± 22,648 (3,077) | 12,543 ± 22,677 (4,190) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 1,230 ± 8,743 (0) | 908 ± 5,094 (0) | 0.285 |

| Disease-related medical costs, $c,d | |||

| Overall | 10,162 ± 39,068 (1,698) | 15,511 ± 50,605 (1,974) | 0.005 |

| Emergency department | 4,093 ± 31,255 (0) | 5,365 ± 31,043 (0) | 0.331 |

| Inpatient | 2,008 ± 13,917 (0) | 5,064 ± 32,141 (0) | 0.003 |

| Physician | 1,428 ± 9,045 (697) | 1,455 ± 3,406 (685) | 0.925 |

| Outpatient | 2,348 ± 7,133 (145) | 3,398 ± 9,132 (194) | 0.002 |

| Other | 284 ± 4,314 (0) | 229 ± 4,003 (0) | 0.751 |

| Drug costs, $e | |||

| Overall | 37,347 ± 30,047 (38,936) | 33,287 ± 31,166 (28,681) | 0.002 |

| Disease-related (biologics and synthetic-targeted immune modulators)f | 32,315 ± 27,539 (34,829) | 28,347 ± 26,705 (23,775) | < 0.001 |

| Adalimumab | 27,335 ± 23,206 (25,457) | 21,905 ± 21,729 (16,527) | < 0.001 |

| Other biologics and synthetic-targeted immune modulators | 4,980 ± 17,469 (0) | 6,442 ± 18,618 (0) | 0.054 |

Data source: Symphony Health Solutions claims database, 2015-2017.

Note: All data are expressed as mean ± SD (median).

aCosts were evaluated over the 12-month period following the index date and were calculated using the service charge for medical claims and the primary plan payment for prescriptions.

bPSP cohort versus non-PSP cohort.

cExcluding biologic and synthetic-targeted immune modulator drug costs.

dIncludes costs from medical claims with a corresponding diagnosis of an autoimmune disease indication for each patient.

eIncluding biologic and synthetic-targeted immune modulator drugs covered by medical and pharmacy benefits, and any other prescription costs.

fIncluding abatacept, anakinra, apremilast, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, natalizumab, rituximab, secukinumab, tocilizumab, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab.

PSP = patient support program; SD = standard deviation.

All-cause emergency department costs were also significantly lower for PSP than non-PSP patients ($6,227 vs. $9,875; P = 0.038). In addition, all-cause and disease-related outpatient costs were lower for PSP than for non-PSP patients ($9,272 vs. $12,543; P < 0.001, and $2,348 vs. $3,398; P = 0.002, respectively). In alignment with increased treatment adherence and decreased rates of discontinuation, drug costs were 12.2% greater ($37,347 vs. $33,287; P = 0.002) for the PSP cohort compared with the non-PSP cohort (Table 2). Due to increased adherence, biologic and synthetic-targeted immune modulator drug costs were also 14.0% greater for PSP than for non-PSP patients ($32,315 vs. $28,347; P < 0.001), and ADA costs specifically were 24.8% greater ($27,335 vs. $21,905; P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study provides novel and valuable evidence and insights into the real-world benefits of PSPs to patients and payers using a national claims database. An innovative data-linking initiative provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the relationship between participation in a PSP and outcomes relevant to patients, providers, and payers in a large and diverse patient population. In previous studies of PSPs,20 smaller patient populations were reported, and there have been few reports of PSP use by patients with chronic diseases. In contrast, this was a large study with a geographically diverse patient population of approximately 2,000 patients, with a broad range of commercial health care plans and a range of autoimmune diseases treated with ADA.35 The longitudinal patient-level information on medical and pharmacy claims allows for the determination of the temporal relationship between PSP enrollment and outcomes using a matching methodology encompassing a wide variety of variables to construct cohorts of patients with similar baseline characteristics.

Given the shift in the U.S. health care system to value-based care, additional strategies need to be employed to increase patient engagement and self-management, particularly in longterm chronic diseases. As previously documented, PSPs are one such strategy now widely used across a range of diseases, and they have demonstrated their value in reducing health care costs while significantly improving quality of care and quality of life for patients.29 There is, however, a paucity of real-world evidence on the use of PSPs by patients receiving biologic therapies where an improvement in patient adherence will support efforts by health care providers, payers, and policymakers to deliver better quality of care while at the same time reducing overall health care costs.

The value of an earlier ADA PSP has been studied in patients treated between 2008 and 2014, predating the inclusion of the Nurse Ambassador component. This previous study demonstrated that participation in the traditional PSP was associated with greater adherence (14%), lower discontinuation rate (-14%), lower medical costs (-23%), and lower total costs (-10%), across a range of indications.27 The current study demonstrates the additional value of comprehensive coordinated care supported by the ADA PSP, as shown with significant changes in adherence (29% greater), discontinuation rate (22% lower), medical costs (29% lower), and total costs (9% lower), despite an increase in prescription costs of 12% across a range of indications. Therefore, although there may be an increase in drug costs associated with a PSP, the total cost associated with treating these indications is likely to be lower.

Limitations

Whereas this study has provided significant, real-world evidence for the value of the ADA PSP, there are some limitations of the SHS database and in the study design that should be noted. These results may not be generalizable to patients with government-funded insurance because they were excluded from this analysis. There also may have been differences in patient selection due to differing characteristics between patients who chose to opt in to the PSP versus those who did not, which were not observable in the data. SHS does not have an eligibility file, so we cannot be sure that we captured the full scope of health care usage for all patients. Although algorithms were used to determine data coverage, these were not validated for this study.

Not all providers participate in SHS, so visits to providers not captured by SHS were not observed in the analysis. This likely biases the costs for both cohorts downward, although it should be acknowledged that we do not know whether participation in SHS is correlated with patient participation in the PSP. To reduce the effect of missing visits, we implemented restrictive eligibility criteria, as previously described, that excluded a large portion of the available sample. Reimbursement data were not available, and service charges may not have accurately reflected final reimbursed amounts, which may overestimate actual costs; however, this should not cause bias in the relative changes found between cohorts.

The design of the study may also provide limitations that cause mismeasurement of the outcomes. Patients in the non-PSP cohort may have participated in assistance programs not captured in the data, which may have caused improved patient outcomes and ultimately caused an underestimation of the comparison of the PSP versus non-PSP cohorts. The contributions of specific components and the benefits of increased use of the PSP were not estimated, and analysis of patients who were excluded (e.g., those who received government-provided insurance) are areas of continued research.

Finally, this study focused on mean outcomes for a potentially heterogeneous patient population and did not examine the effect of the PSP in indication-specific subgroups, which is an interest of future research.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that participation in the unique and innovative ADA PSP adds significant value to the treatment of patients across a range of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases by lowering total medical costs and significantly increasing adherence to treatment. The value of the ADA PSP in specific patient subgroups or other payer populations may differ from the benefits found in this study and should be explored. Furthermore, the full extent of benefits that nontraditional PSP initiatives may offer to patients with other chronic diseases should be investigated in order to fully realize the potential of PSPs to augment value-based care approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by Fiona Woodward of JK Associates, a member of the Fishawack Group of Companies, and funded by AbbVie.

APPENDIX. ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Codes

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 720, 720.0, M45.x, M08.1 |

| Crohn’s disease | 555.x, K50.x |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | 705.83, L73.2 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 696.0, L40.5 |

| Psoriasis | 696, 696.1, 696.8, L40.x |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 714, 714.0, 714.8, 714.89, 714.9, M05.x, M06.x, M08.x |

| Ulcerative colitis | 556.x, K51.x |

| Uveitis | 360.01, 360.02, 360.03, 360.11, 360.12, 362.12, 362.18, 363.00, 363.01, 363.03, 363.04, 363.05, 363.06, 363.10, 363.11, 363.12, 363.13, 363.14, 363.15, 363.20, 363.21, 363.22, 364.0, 364.00, 364.01, 364.02, 364.03, 364.04, 364.05 364.1, 364.10, 364.11, 364.21, 364.22, 364.23, 364.24, 364.3, H20.0 |

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM=International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Value in health care: accounting for cost, quality, safety, outcomes and innovation. March 2009. Available at: https://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/IOM-value-issues-brief.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 2.Fraser I. Evaluating the impact of value-based purchasing: a guide for purchasers. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. May 2002. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/value/valuebased/evalvbp1.html. Accessed May 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Leadership Commitments to Improve Value in Health Care: Finding Common Ground: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieleman JL, Squires E, Bui AL, et al. . Factors associated with increases in U.S. health care spending, 1996-2013. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1668-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (P.L. 110-275). 2008. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-110publ275. Accessed April 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-148). 2010. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung K, Li M, Carlson JJ. Using performance-based risk-sharing arrangements to address uncertainty in indication-based pricing. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1010-15. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.10.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah NR, Hirsch AG, Zacker C, et al. . Predictors of first-fill adherence for patients with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(4):392-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. . New prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptions. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(5 Pt 1):1640-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, et al. . Primary nonadherence, associated clinical outcomes, and health care resource use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis prescribed treatment with injectable biologic diseasemodifying antirheumatic drugs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):209-18. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauffenburger JC, Franklin JM, Krumme AA, et al. . Predicting adherence to chronic disease medications in patients with long-term initial medication fills using indicators of clinical events and health behaviors. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(5):469-77. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. . Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. . Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bluett J, Morgan C, Thurston L, et al. . Impact of inadequate adherence on response to subcutaneously administered anti-tumour necrosis factor drugs: results from the Biologics in Rheumatoid Arthritis Genetics and Genomics Study Syndicate cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(3):494-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services. Enhancing health outcomes for chronic diseases in resource-limited settings by improving the use of medicines: the role of pharmaceutical care. May 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21523en/s21523en.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 18.Christie D, Channon S. The potential for motivational interviewing to improve outcomes in the management of diabetes and obesity in paediatric and adult populations: a clinical review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(5):381-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgopoulou S, Prothero L, Lempp H, et al. . Motivational interviewing: relevance in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(8):1348-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganguli A, Clewell J, Shillington AC. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:711-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr., et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. . American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):282-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Academy of Dermatology Work Group, Menter A, Korman NJ, et al. . Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6: guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):137-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wendling D, Joshi A, Reilly P, et al. . Comparing the risk of developing uveitis in patients initiating anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for ankylosing spondylitis: an analysis of a large U.S. claims database. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(12):2515-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fidder HH, Singendonk MMJ, van der Have M, et al. . Low rates of adherence for tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(27):4344-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer JB, Li Y, Herrera V, et al. . Treatment patterns and costs for anti-TNF-alpha biologic therapy in patients with psoriatic arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DT, Mittal M, Davis M, et al. . Impact of a patient support program on patient adherence to adalimumab and direct medical costs in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):859-67. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.16272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lafeuille MH, Grittner AM, Lefebvre P, et al. . Adherence patterns for abiraterone acetate and concomitant prednisone use in patients with prostate cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(5):477-84. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.5.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohayon MM, Black J, Lai C, et al. . Increased mortality in narcolepsy. Sleep. 2014;37(3):439-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuart EA, Ialongo NS. Matching methods for selection of subjects for follow-up. Multivariate Behav Res. 2010;45(4):746-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv. 2008;22(1):31-72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-1 matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(9):1092-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imbens GW. Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: a review. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(1):4-29. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stockl KM, Shin JS, Lew HC, et al. . Outcomes of a rheumatoid arthritis disease therapy management program focusing on medication adherence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(8):593-604. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.8.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]