Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide and has a substantial impact on people’s health and quality of life. CVD also causes an increased use of health care resources and services, representing a significant proportion of health care expenditure. Integrating evidence-based community pharmacy services is seen as an asset to reduce the burden of CVD on individuals and the health care system.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) identify community pharmacy evidence-based services designed to help prevent CVD and (b) provide fundamental information that is needed to assess their potential adaptation to other community pharmacy settings.

METHODS:

This review used the DEPICT database, which includes 488 randomized controlled trials (RCT) that address the evaluation of pharmacy services. Articles reviewing these RCTs were identified for the DEPICT database through a systematic search of the following databases: MEDLINE, Scopus, SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), and DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals). The DEPICT database was reviewed to identify evidence-based services delivered in the community pharmacy setting with the purpose of preventing CVD. An evidence-based service was defined as a service that has been shown to have a positive effect (compared with usual care) in a high-quality RCT. From each evidence-based service, fundamental information was retrieved to facilitate adaptation to other community pharmacy settings.

RESULTS:

From the DEPICT database, 14 evidence-based community pharmacy services that addressed the prevention of CVD were identified. All services, except 1, targeted populations with a mean age above 60 years. Pharmacy services encompassed a wide range of practical applications or techniques that can be classified into 3 groups: activities directed at patients, activities directed at health care professionals, and assessments to gather patient-related information in order to support the previous activities.

CONCLUSIONS:

This review provides pharmacy service planners and policymakers with a comprehensive list of evidence-based services that have the potential to be adapted to different settings from which they were originally implemented and evaluated in order to reduce the burden of CVD.

What is already known about this subject

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide and has a substantial impact on people’s health, quality of life, and health care costs.

Community pharmacists are highly accessible health care professionals at the primary care level, who have been shown to have a positive impact on the control of cardiovascular risk factors when providing patient-centered services.

What this study adds

This review provides health service planners and policymakers with a comprehensive list of 14 evidence-based community pharmacy services that can be adapted to other community pharmacy settings in order to include pharmacists as part of the strategies to reduce the burden of CVDs.

This review found that the description of pharmacy services must be improved in order to facilitate the translation of evidence-based services into practice.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide and has a substantial impact on people’s health and quality of life. CVD also causes increased use of health care resources and services, representing a significant proportion of health care expenditure.1,2 Reducing the burden of CVD is a major public health challenge, which requires interventions that address the major and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors and associated risk behaviors.3 Individual interventions at the primary health care level are seen as the most efficient approach to reverse the progression of CVD, prevent long-term complications, and reduce the use of health care resources and health care expenditure.4 Identifying and adopting primary care interventions designed to reduce the burden of CVD is a priority for health policy decision makers.5 Evidence-based interventions—those interventions based on the best scientific evidence and have been shown to be effective following rigorous scientific evaluation—are particularly relevant.6,7

Adapting evidence-based interventions to settings or populations for which they were not originally developed presents unique challenges. Intervention Mapping is a consolidated framework for health program planning that helps planners address challenges presented by adapting an evidence-based intervention to a new setting or population, as well as furthering its implementation and evaluation.6,8,9 According to Intervention Mapping, the decision to adopt an evidence-based intervention requires fundamental information from the original intervention to understand how a particular problem was addressed in a particular context and group of individuals. Such information will then be used to evaluate whether the evidence-based intervention can help address the specific problems or needs in a planner’s own context, whether it fits the particular circumstances of the new context, or how it can be tailored to fit the characteristics of the new setting or population.

The fundamental information regarding an evidence-based intervention encompasses a definition of the population for whom the intervention is intended (i.e., end-beneficiaries); a comprehensive description of the intervention; and a description of the contextual circumstances that may influence the delivery, implementation, and/or overall effect of the intervention. A comprehensive description of an evidence-based intervention goes beyond defining the activities that target the end-beneficiaries to also include a description of those activities that target the behaviors of the agents in the environment. Environmental agents are individuals who directly deliver the intervention (i.e., service providers); who can interact with the providers and have an influence on the problem (e.g., other health care professionals); or who can affect the implementation or sustainability of the intervention (e.g., organization/health system managers). Moreover, for each of the intervention’s activities, Intervention Mapping puts special emphasis on the description of some essential elements, such as theoretical methods, practical applications, processes, and materials, that are used to cause changes in the determinants of the behaviors of the end-beneficiaries and environmental agents.

Community pharmacists are highly accessible medication experts who have been shown to have a positive impact on the control of cardiovascular risk factors when providing patient-centered services.10,11 Integrating evidence-based community pharmacy services is seen as a valuable way to achieve better cardiovascular care at the primary health care level.12 Intervention Mapping may assist pharmacy service planners to adapt, implement, and evaluate such services and so overcome existing implementation challenges in pharmacy prac-tice.13 Although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses addressing the impact of cardiovascular community pharmacy services have been conducted,14-16 there is no detailed list of those services that have been evaluated through a high-quality research study and been shown to have had a positive impact on any health-related outcome (i.e., social, health, behaviors, and determinants of behaviors). Having an exhaustive description of these evidence-based services can enable pharmacy service planners to assess their suitability and adaptability for enhancing cardiovascular care within other community pharmacy settings. Thus, the objectives of this systematic review were to (a) identify evidence-based community pharmacy services designed to prevent CVD and (b) provide the fundamental information that is needed to assess their potential adaptation to other community pharmacy settings.

Methods

This review used the database of the DEPICT Project (Descriptive Elements of Pharmacist Intervention Characterization Tool), which is a multicenter research program that develops, refines, and applies a tool designed to systematically characterize the components of clinical pharmacy services (i.e., the DEPICT tool).17,18 A clinical pharmacy service is a service in which pharmacists provide patient care to optimize medication therapy management and encourage health, wellness, and disease prevention in any health care setting.19 A comprehensive database consisting of any randomized controlled trial (RCT), including individually and cluster RCTs, that assesses the impact of a clinical pharmacy service on any type of health-related outcome was set up as part of the DEPICT Project. Briefly, the articles included in the DEPICT database have been identified through 2 procedures. First, an overview of systematic reviews assessing the impact of clinical pharmacy services was conducted to identify 49 systematic reviews, comprising a total of 269 RCTs.20 Second, a systematic search of the literature was performed to November 30, 2014, in MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), and DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) without using time limits. All the articles identified through these procedures were subjected to a 2-step selection process using 8 systematic exclusion criteria. A comprehensive description of the methods used to set up the DEPICT database, including the search strategies and the eligibility criteria, is available on the project website (http://www.depictproject.org/methods.htm) and in Appendix A (available in online article). At the time of this review, the DEPICT database included 569 articles, which addressed 488 RCTs that evaluated a clinical pharmacy service. Of those, 131 articles were related to the community pharmacy setting.

Article Screening and Review

Titles and abstracts of the 131 articles were independently screened by 2 reviewers (authors Sabater-Hernández and Sabater-Galindo) to identify those services that are intended to prevent CVDs due to atherosclerosis (e.g., ischemic heart disease, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease4) and/or improving a cardiovascular risk factor that contributes to the process of atherosclerosis (e.g., tobacco use; physical inactivity; unhealthy diet that is rich in salt, fat, and calories; harmful use of alcohol; raised blood pressure; raised blood glucose; raised blood lipids; and overweight/obesity4). Services that targeted any behavioral or environmental cause of such risk factors or the determinants of those causes (i.e., factors that can influence patient behaviors) were also retained in the screening process. Any disagreements between the reviewers were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Full-text articles were then reviewed for evidence-based community pharmacy services intended to prevent CVDs. An evidence-based intervention was defined as an intervention that was shown to be effective after rigorous scientific evalua-tion.6 Based on this definition, a community pharmacy service was considered an evidence-based service if (a) it had been tested by at least 1 RCT; (b) it was shown to have had a positive effect compared with usual care; and (c) the methodological quality of the trial had been established as high quality (or low risk of bias) after critical appraisal. Since the DEPICT database only includes RCTs, the positive effect of the service and the high methodological quality of the RCT were the 2 main criteria that were considered for article inclusion in this review.

A positive effect of the service was adjudicated when statistically significant differences between groups (i.e., intervention vs. comparator) were found in at least 1 of the primary outcome variables at the end of the study. According to the ultimate goal of this review (i.e., provide pharmacy service planners and policymakers with a list of evidence-based services that can be adapted to the community pharmacy setting to enhance cardiovascular care), studies reporting a neutral (i.e., no significant differences between groups) or a negative effect of a pharmacy service (i.e., comparison group showed to be superior) were excluded, since they do not provide strong evidence for such a service to be adapted to other community pharmacy settings. Similarly, studies that did not report the results of a statistical test to assess the differences between groups or that reported significant differences between groups but only in secondary outcome variables (i.e., they were not the primary target of the intervention) were also excluded. The 2 reviewers involved in the screening also conducted this process. Disagreements between the reviewers were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Methodological Quality

To assess the methodological quality of the studies with positive effects, the citations for each study were checked in Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to identify previously published systematic reviews (and meta-analyses) in which these studies were included. Then, the results of those systematic reviews that used an acknowledged tool to assess the methodological quality of RCTs were checked (i.e., tool whose fundamentals, characteristics, development, and validation had been addressed in an existing publication; this excludes ad hoc quality assessment tools). Studies that were classified as high methodological quality or low risk of bias by at least 1 systematic review were included in this review. Risk of bias in those studies that were not addressed, or whose methodological quality was not reported by a previous systematic review, was determined by an independent reviewer (author Lopes) using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.21 Articles were included if a low risk of bias was established.

Data Extraction

Data from the articles were extracted by 1 reviewer who had experience in community pharmacy service development and evaluation (author Sabater-Hernandez). The first version of a data extraction tool was developed based on criteria outlined by Intervention Mapping with regard to adapting health programs to other settings or populations.6 To extract relevant data, this tool used the following parameters: (a) the characteristics of the population for whom the service was intended; (b) the contextual circumstances that may influence the delivery, implementation, and/or overall effect of the intervention; and (c) all activities targeting patients and environmental agents (e.g., community pharmacists, allied health care professionals, and pharmacy managers), including the theoretical methods, practical applications, processes, and materials that were used to cause changes in the behaviors of such individuals. The initial version of the tool was tested using a sample of 5 articles and further adapted according to the available information in pharmacy practice articles. The general structure and items included in the final version of the tool are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Structure of Data Extraction Tool and Included Items

| Structure | Items |

| Basic information about community pharmacy service | Benefits of the service (compared with control group) Country Intervention length Visit pattern Time consumed |

| Definition of target population | Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria Cardiovascular profilea |

| Description of community pharmacy service | Practical applications or techniques directed at patients and/or other health care professionals to motivate, support, and/or sustain changes in patient behavior or health care practice Assessments performed by the service provider to gather patient-centered information and support the service’s activities |

| Strategies and interventions to support implementation and sustainability of community pharmacy service | As reported by each study’s authors |

| Contextual circumstances that influence delivery, implementation, and/or overall effect of community pharmacy service | As reported by each study’s authors |

aAccording to the classification of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases established by the World Health Organization.4

Results

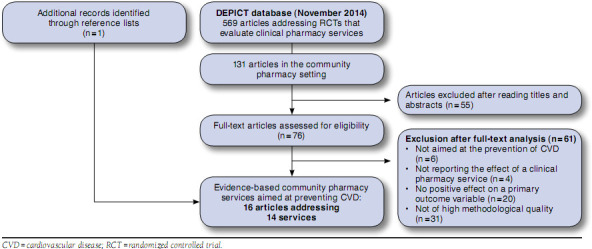

After screening titles and abstracts of the 131 community pharmacy-based articles included in the DEPICT database, 76 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). The kappa index for the agreement between the reviewers showed an acceptable agreement (Kappa = 0.83; 95% confidence interval = 0.73-0.92). Of the 76 full-text articles, 61 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded: 10 articles were outside the scope of this review; 20 articles did not show a positive impact of the community pharmacy service on a primary outcome variable; and 31 articles were not assessed as high methodological quality (or low risk of bias). As a result, 16 articles (15 derived from the DEPICT database and 1 study protocol22 retrieved from the reference lists) that addressed 14 evidence-based community pharmacy services intended to prevent CVD were included in this review.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of Systematic Review Articles

Table 2 shows the variety of outcomes (e.g., social, health, and behavioral) and process indicators and groups at risk of CVDs targeted by the evidence-based community pharmacy services. Based on their primary objectives, the purpose of 8 services was improving the control of a specific cardiovascular risk factor in a group of patients affected by such a risk factor (5 in diabetes11,23-26 and 3 in hypertension27-29). Another 3 services were meant to enhance patient adherence to a certain treatment (2 focusing on statins in patients with dyslipid-emia30,31 and 1 addressing loop-diuretics in patients with heart failure32); 1 service was aimed at smoking cessation33; and 1 more at enhancing the management of dyslipidemia in patients at high risk of coronary heart disease.34,35 Finally, Amariles et al. (2012, 2008) described the broadest service, intended to help improve blood pressure and total cholesterol in a wide group of patients at moderate or high risk of CVDs.10,22 Remarkably, all services except 1 targeted populations with a mean age above 60 years,33 and 3 services were shown to have had an impact on 2 or more cardiovascular risk factors simul-taneously.10,11,23

TABLE 2.

At-Risk Populations and Benefits Addressed by Evidence-Based Community Pharmacy Services Designed to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease

| Study | Population at Riska | Benefits of Service (Indicators) | ||||

| Social | Health | Patient Behaviors | Determinants of Behavior | Environmental Conditions and Behaviors of Environmental Agents | ||

| Ali M, et al.23 | Individuals with type 2 diabetes, HbAlc > 7%, under oral hypoglycemic treatment (100%); age: 66.4 (SD: 12.7) | HbA1cb; FCG levels; hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia episodes; SBP levels; HDL-C levels; health status | Knowledge about diabetes; beliefs about medicines | |||

| Amariles P, et al. 10,22 | Individuals with moderate or high cardiovascular risk (100%); hypertension (88.0%); uncontrolled hypertension (67.1%); dyslipidaemia (71.3%); uncontrolled dyslipidaemia (57.6%); overweight/obese (80.7%); age: 63.0 (SD: 8.3) | BP controlb; TC controlb; SBP levels; TC levels | ||||

| Bouvy ML, et al.32 | Individuals with heart failure under treatment with loop diuretics (100%); myocardial infarction (56.8); age: 69.1 (SD: 10.2) | Adherence to loop diureticsb | ||||

| Eussen SR, et al.30 | New users of statins (100%); unhealthy diet (53.0); physical inactivity (62.0); age: 60.2 (SD: NS) | Adherence to statinsb | ||||

| Fornos JA, et al.11 | Individuals with type 2 diabetes under oral hypoglycemic treatment (100%); age: 62.4 (SD: 10.5) | HbA1cb; FCG levels; SBP levels; TC levels; DRP | Knowledge about diabetes | |||

| G arcao JA, et al.27 | Individuals with primary hypertension under antihypertensive treatment (100%); uncontrolled hypertension (76.0%); age: 66.5 (SD: 8.2) | BP controlb; SBP and DBP levelsb | ||||

| Krass I, et al.24 | Individuals with diabetes, HbA1c above normal threshold, under oral hypoglycemic treatment or insulin (100%); hypertension (70.0%); dyslipidemia (61.0%); age: 62.0 (SD: 11.0) | Patient’s quality of lifec | HbA1c levelsb | |||

| Maguire TA, et al.33 | Smokers, expressing a wish to stop smoking; age: 42.0 (SD: NS) | Cease smokingb | ||||

| Mehuys E, et al.25 | Individuals with type 2 diabetes, under oral hypoglycemic treatment; overweight/obese (100%); age: 63.0 (SD: NS) | FPG on targetb | Self-management activities’1 | Knowledge about diabetes | Satisfactory adjustments in oral hypoglyce-mic treatment | |

| Sarkadi A, et al.26 | Individuals with diabetes, under oral hypo-glycemic medication or insulin for less than 2 years (100%); age: 66.4 (SD: 7.9) | HbA1c levelsb,e | ||||

| Sookaneknun P, et al.28 | Individuals with primary hypertension under antihypertensive treatment (100%); uncontrolled hypertension (77.1%); age: 63.2 (SD: 9.3) | SBP and DBP levelsb | Adherence to antihypertensive treatment; practice regular exercise | |||

| Tsuyuki RT, et al. 34,35 | Individuals at high risk of coronary heart disease (with previous CVD or diabetes with 1 or more cardiovascular risk factor; 100%); age: 64.2 (SD: 12.2) | Cholesterol risk management | ||||

| Vrijens B, et al.31 | Individuals under treatment with atorvastatin (100%); age: 61.9 (SD: 9.9) | Adherence to statinsb | ||||

| Zillich AJ, et al.29 | Individuals with uncontrolled hypertension under antihypertensive treatment (100.0%); dyslipidaemia (50%); age: 64.0 (SD: 11.1) | DBP levelsb | ||||

aOnly those conditions in which prevalence in the study sample was higher than 50% are mentioned.

bPrimary outcome variable as specified by the study authors.

cEQ-5D health-state scores.

dPhysical exercise and foot care.

eImprovements in HbAlc levels were observed 1 year after the end of the intervention but not immediately after its delivery (intervention length: 1 year).

fAccording to study authors’ definition, cholesterol risk management addressed: performing fasting cholesterol panel, addition of cholesterol-lowering medication, adjustments in treatment.

BP = blood pressure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; DRP = drug-related problems; FCG = fasting capillary glucose; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; HbAlc = hemoglobin Alc; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NS = not specified; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SD = standard deviation; TC = total cholesterol.

Community pharmacy services encompassed a wide range of practical applications or techniques that can be classified into 3 broad groups: (1) activities directed at patients; (2) activities directed at health care professionals; and (3) assessments to gather patient-related information in order to support the previous activities (Table 3). Regarding the first 2 groups of activities, Table 3 shows a list of all the practical applications or techniques that were used in the analyzed services to motivate, support, and/or sustain changes in patient behaviors or in health care practice (i.e., changes in the management of health problems by other health care professionals). Appendix B (available in online article) provides a comprehensive description of the different techniques used by each particular service. As shown in Table 3, “pharmacists providing one-on-one information or instructions to patients” was reported by 13 out of 14 services (the remaining service did not approach individual patients26). Regularly, pharmacy services techniques that targeted patients, such as providing patients “with written information on the assessments included by the service” or “with support material to facilitate behavioral changes,” which half of the services reported. Nine out of 14 services included techniques directed at other health care professionals. Of those 9 services, only 1 clearly reported discussions between pharmacists and physicians for collaboration in developing patient treatment plans.29 The more comprehensive services were those designed by Krass et al. (2007; enhancing glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes24) and Bouvy et al. (2003; increasing adherence to diuretics in patients with heart failure32), which comprised all 5 techniques to target individual patients along with at least 1 technique directed at other health care professionals. On the other hand, Maguire et al. (2001) reported the “simplest” service (aimed at smoking cessation) that included 2 techniques to target patients and did not approach other health care professionals.33 A number of assessments were routinely performed as part of the pharmacy services to support decisions and actions made by service providers (Table 3). Overall, these assessments encompassed a wide spectrum of variables, including health outcomes (e.g., blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, lipid profile, and drug-related problems); health care processes (e.g., adequacy of treatment and need of new drugs); patient behaviors (e.g., medication use process, adherence to treatment, and lifestyle habits); and determinants of patient behaviors (e.g., knowledge, beliefs, and concerns). The most repeated assessment was adherence to treatment (9 of 14 services) followed by drug-related problems (6 of 14 services). Ali et al. (2012),23 Fornos et al. (2006),11 and Amariles et al.10,22 reported the more comprehensive services that addressed a wide variety of variables and included the largest number of health outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Practical Applications or Techniques Delivered as Part of Community Pharmacy Services to Encourage and Support Changes in Patient Behaviors and Health Care Practice

| Numbera | |

| Targeting Patients | |

| Pharmacists providing one-on-one information or instructions to patients regarding health problems; correct use/administration of medicines (including adverse effects, interactions, precautions); adherence to treatment; risk/healthy behaviors; self-management; or self-monitoring/self-report. This also includes reinforcement to make an idea, an attitude, patient’s knowledge, or a behavior stronger.10-11-22-25-27-35 | 13 |

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service.23-24-30-32-34-35 | 7 |

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behavioral changes (e.g., monitoring devices, adherence-aid devices, and patient diary).24-25,28,29,31,32 | 7 |

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results derived from the assessments performed as part of the service.24,28,30-32 | 5 |

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals and follow-up plans; developing mutual treatment plans.10,22,24,26,32,33 | 5 |

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions.26 | 1 |

| Targeting Health Care Professionals | |

| Pharmacists providing relevant information about patient’s current status and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals (e.g., add new medicines, suspend a medication, change a medication, change dose or frequency of medicines, or make adjustments according to clinical guidelines).10,11,22-24,26,27,29,32,34,35 | 9 |

| Pharmacists requesting that other health care professionals perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status.34,35 | 1 |

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals.29 | 1 |

| Assessments Performed by Service Providers to Support Their Decisions and Actions | |

|

Health outcomes: BP (community pharmacy),10,11,22,23,27-29 BP (home),29 BG (community pharmacy),11,23 BG (home),24-26 HbA1c,11, 23 hypo- and hyperglycemic episodes,23 TC,10,11,22,23,30,34,35 TG,11,23,30 HDL-C,11,23,30 LDL-C,11,23,30 BMI,10,11,22,23,27 albumin-creatinine ratio,11 global cardiovascular risk,10,22 health status,23 adverse drug reactions,10,22,27,28,32 drug-related problems(b)10,11,22,24,27,28,30 |

12 |

| Health care processes (i.e., environmental factors): adequacy of treatment,(c)10,11,22-24,33 adjustments in treatment plan,(d)10,11,22,34,35 request of assessment tests(e)10,22,34,35 | 6 |

| Patient behaviors: medication use/administration process,10,22,23,32 adherence to treatment,10,11,22,25,28-32,34,35 lifestyle habits,(f)10,11,22,23,25,26,28 self-monitoring/self-care,24,25 attend appointment with physician34,35 | 12 |

| Determinants of patient behaviors: knowledge (medicines),10,11,22,28 knowledge (health problems),10,11,22,23,25 beliefs/concerns (medicines),10,22,23 beliefs/concerns (health problems),10,22 causes of nonadherence (i.e., any cause)30,32 | 7 |

aNumber of services for which each technique was reported (out of 14).

bThe term drug-related problems was used with different meanings and, depending on the study authors, included the assessment of health outcomes (e.g., adverse effect); environmental factors (e.g., adequacy of treatment); or patient behaviors (e.g., correct use of medicines).

cAssessing the appropriateness of pharmacological treatments according to guidelines (evidence-based recommendations) with respect to individual patient characteristics (clinical conditions) or to the use of concomitant treatments (interactions, precautions, contraindications). Also includes assessing the need for new drugs.

dAssessing whether other health professionals made the required changes in pharmacological treatment.

eAssessing whether other health professionals requested additional laboratory tests to further assess the patient’s health status.

fAssessing 1 or more risk lifestyle factors (i.e., actual status or adherence to recommendations), including smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and harmful use of alcohol.

BG = blood glucose; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; HbAlc = hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC = total cholesterol; TG = triglycerides.

In addition to the description of practical applications or techniques used by community pharmacy services, the authors of these studies provided arbitrary information regarding the strategies and interventions to support the implementation and sustainability of the service. This information, when provided, was principally concerned with a broad description of the interventions directed to the service providers (i.e., community pharmacists; Table 4). Similarly, the contextual circumstances that can affect the provision, implementation, and/or overall effect of community pharmacy services were scarcely reported. Table 5 shows a summary of the complete set of factors reported in all articles concerning these contextual circumstances.

TABLE 4.

Strategies and interventions Directed at Service Providers to Support implementation and Sustainability of Community Pharmacy Services

|

TABLE 5.

Contextual Circumstances Affecting Provision, Implementation, and/or Overall Effect of Community Pharmacy Services

|

Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive list of 14 evidence-based community pharmacy services that have the potential to be adapted to other community pharmacy settings for enhancing cardiovascular care. Therefore, it represents a valuable source of information for pharmacy service planners and policymakers to postulate community pharmacists as part of the solution to reduce the burden of CVD. In general, the community pharmacy services included in this review were aimed at primary (i.e., prevent severe pathogenesis and experience of a first episode of CVD) and secondary prevention (i.e., prevent recurrence in patients with previous history of CVD) of CVD in advanced aged populations. No services aimed at preventing the onset of cardiovascular risk factors, or at early detecting and treating those factors, came up as part of this review. Special attention should be paid to those pharmacy services that reported a simultaneous positive impact on several outcomes.10,11,23

To initially assess the feasibility of adapting the analyzed services to a new setting, planners and decision makers must have a clear idea about the relevant cardiovascular needs and groups at risk that require attention in their particular contexts. With this in mind, and considering the health problems and target populations addressed by the evidence-based community pharmacy services presented in this review (Table 1), planners can evaluate whether any of these services could be used in addressing their needs. Further, to make a final decision to adopt a particular service, the feasibility and implications of adapting the service to the new setting should be assessed.6 For this purpose, it is important to consider the description of the pharmacy service, which should outline not only the activities delivered by the service providers, but also any other activity related to the implementation of the service.

As previously reported by other authors,17,18 the description of pharmacy services in studies reporting the impact or outcome evaluation of such services is limited to a few paragraphs in the Methods sections. When the protocols of those impact studies are available (2 of which were identified by this review22,34), some extra information can be obtained. The descriptions reported in the analyzed articles focused mainly on the activities (i.e., practical applications or techniques) that pharmacy service providers delivered to patients, including the assessments used to support the decisions and actions of the service providers. Beyond the description of those practical techniques, the articles reported limited or no information about the processes and materials of the services, the interventions used in the implementation of the services, or the contextual circumstances in which the services were trialed. The lack of comprehensive descriptions of evidence-based services clearly restricts the analysis required to make a decision about adapting them to other settings, which limits their translation into practice. As a result, the information in this review will allow planners to initially evaluate whether the analyzed services can be adapted to their contexts, but it is not enough to make a final decision. For this latter purpose, additional information from the study authors will be required.36

The information regarding materials (e.g., educational material, measurement tools, and guidelines to support pharmacy practice) and processes (e.g., methods for assessing variables, appointment schedules, intended actions at each appointment, and delivery channels) of the services examined were scarce and not systematically reported by the authors of the studies reviewed here. For example, some authors summarized the main activity of a service intended for patients as “pharmacist delivered an educational message at each follow-up visit,” without any further explanation about the content of the educational message, its immediate intention, or any educational material that was used.31 Another issue that limited the description of pharmacy services was the use of broad terms with multiple or unclear meanings, such as “drug-related problems” (DRP). According to the literature, this term can mean the assessment of health outcomes (e.g., adverse effect); environmental factors (e.g., appropriateness of treatment); or patient behaviors (e.g., correct use of medicines).37 Consequently, terms with multiple meanings need to be precisely defined in order to clearly understand what was assessed.

Theoretical methods are the general techniques for influencing changes in the determinants of individual behavior, such as knowledge, self-efficacy, or awareness.6 Examples of theoretical methods for changing patient behavior are tailoring, reinforcement, skills training, self-monitoring of behavior, and goal setting. However, theoretical methods were not consistently reported in the articles analyzed for this review nor were the determinants that were targeted to be changed. For example, all pharmacy services included educational sessions for patients, and some studies reported the general content of such sessions. However, explanations by study authors seldom addressed the immediate determinants to be changed by such sessions (e.g., awareness, knowledge, attitude, and skill development) or the underlying theoretical principles that were used to achieve such changes. Such inconsistent descriptions of underlying mechanisms for change hinders the understanding of how a pharmacy service is expected to address a problem and cause change, so it is difficult to adapt that service to circumstances or requirements of new settings or populations.

The description of pharmacy services was more inconsistent, or nonexistent in some cases, for those interventions directed at other health care professionals or at supporting the implementation and sustainability of the service (e.g., interventions intended for pharmacy service providers or pharmacy administrators). Similarly, the contextual circumstances in which pharmacy services were delivered were poorly and inconsistently described, which reduces the awareness of key factors that can influence the delivery and implementation and/or sustainability of the service and that should be taken into account when adapting such services to other settings.

More description of evidence-based community pharmacy services is required to enhance translation of those services into practice. Because of the large amount of information that must be reported in order to comprehensively describe pharmacy services, it is recommended to separate this type of information from impact or outcome evaluations of services. Ideally, theoretical descriptions of pharmacy services must be complemented with practical or experimental information that can facilitate their adaptation to new settings. In this regard, a few services reported some promising information about barriers and facilitators to service provision or utilization,33 time consumed,23,29,35 or service costs.38,39

Limitations

This review may be affected by some known limitations of pharmacy practice research, including the inadequate description of pharmacy services, the restricted number of high-quality studies, and the poor quality assessment systems adopted by some systematic reviews.40 Although the DEPICT database has been created by following rigorous search and selection procedures of the scientific literature, it is possible that some studies have been ignored. This systematic review was restricted to high-quality RCTs that showed a positive impact on their primary outcome variables. These criteria were purposely decided upon in order to achieve the highest level of evidence to facilitate decision making regarding the adoption of evidence-based pharmacy services. It is likely that some services incorporated more practical applications than those declared by the study authors. For example, Tsuyuki et al. (1999, 2002) mentioned that pharmacists measured patients’ total cholesterol levels and entered the values in patient information booklets.34,35 It seems logical that the pharmacists and patients discussed these results; however, the authors did not mention this as part of the process.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides pharmacy service planners and policymakers with a comprehensive list of 14 evidence-based community pharmacy services that could be adapted to other community pharmacy settings in order to reduce the burden of CVD. The information provided in this review focuses on the health needs and at-risk populations targeted by the services, as well as on the activities performed by the service providers. This focus allows for an initial evaluation to assess whether the evidence-based community pharmacy service has the potential to be adapted to other community pharmacy settings. However, further information is required from the reviewed studies in order to make final decisions about service adaptation and implementation. The description of pharmacy services must be improved in order to facilitate the translation of evidence-based services into practice. Finally, we strongly encourage pharmacy practice researchers to design and implement high-quality RCTs for inclusion in future reviews of evidence-based community pharmacy services designed for the prevention of CVD.

Appendix A. Literature Search Strategies and Eligibility Criteria Used to include Articles in DEPICT Database

| Literature Search Strategies | |

| Overview of systematic reviews | MEDLINE: systematic review*[Title/Abstract] OR meta-analysis[Publication Type] OR meta-analysis[Title/Abstract] OR systematic literature review[Title/Abstract] OR “cochrane database syst rev”[Journal] OR (search*[Title/Abstract] AND (medline OR embase OR peer-review* OR literature OR “evidence-based” OR pubmed OR ipa OR “international pharmaceutical abstracts”)) AND (pharmacist*[Title/Abstract] OR pharmacists[MeSH Terms]) AND hasabstract NOT (letter[Publication Type] OR “newspaper article”[Publication Type] OR comment[Publication Type]) |

| Primary search of the literature | MEDLINE: (randomized controlled trial[Publication Type] OR controlled clinical trial[Publication Type] OR random allocation[MeSH Terms] OR (random*[Title/Abstract] AND (control*[Title/Abstract] OR trial[Title/Abstract])) AND hasabstract AND (pharmacist*[Title/Abstract] OR pharmacists[MeSH Terms] OR “pharmaceutical care”[Title/Abstract] OR “clinical pharmacy”[Title/Abstract]) NOT (systematic review*[ Title/Abstract] OR meta-analysis[Publication Type] OR meta-analysis[Title/Abstract] OR letter[Publication Type] OR newspaper article[Publication Type] OR comment[Publication Type]) Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR random allocation OR (random* AND (controlled OR trial)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (pharmacist* OR pharmacists) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (systematic review* OR meta-analysis OR letter OR newspaper article OR comment) DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals): (all: random*) AND (all: pharmacist*) SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online): (controlled OR random OR trial) AND (pharmacist OR pharmacists OR pharmaceutical) |

| Eligibility Criteria | |

|

Target: any randomized controlled trial (including individual and cluster randomized controlled trials) that assesses the impact of a clinical pharmacy service on any type of health-related outcome. The exclusion criteria included the following:

| |

Appendix B. Practical Applications or Techniques Applied at Each Community Pharmacy Service To Encourage and Support or Sustain Changes in Patient Behavior and Health Care Practice

| Part 1 | Ali M, et al.1 | Amariles P, et al.2,3 | Bouvy ML, et al.4 | ||

| Targeting patients | |||||

| Pharmacists providing one-on-one information or instructions to patient | Correct use of medicines, including adherence to treatment | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Health problem | Complications of diabetes | CVD; risk factors; treatment goals for TC and BP | |||

| Risk behaviors | PA, HD, SC | PA, HD, SC | |||

| Self-management | Recognition and treatment of hypo- and hyperglycemia; identification of adverse effects | ||||

| Self-monitoring/self-report | |||||

| Support by educational booklets | Mentioned, but not referenced | Reference provided | Not mentioned | ||

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service | All health outcomes assessed at each appointment | Adherence to pharmacological treatment | |||

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behavioral changes | Adherence aid devicea | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results of the assessments included by the service | Adherence to pharma-cological treatment | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals, follow-up plans, developing mutual treatment plans | Yes (treatment plan, follow-up plan) | Changes in loop diuretic schedule | |||

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions | |||||

| Targeting health care professionals | |||||

| Pharmacists providing relevant information and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals | General practitioners, nutritionist3 | Physicians (BP and TC results and treatment recommendations) | General practitioners (report of adherence sessions with patients) | ||

| Pharmacists requesting that other health care professionals perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status | |||||

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals | |||||

| Part 2 | Eussen SR, et al.5 | Fornos JA, et al.6 | Garcao JA, et al.7 | ||

| Targeting patients | |||||

| Pharmacists providing one-to-one information or instructions to patients | Correct use of medicine, including adherence to treatment | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Health problem | Acute and chronic complications of diabetes; foot care | ||||

| Risk behaviors | PA, HD, SC | PA, HD, SC | |||

| Self-management | |||||

| Self-monitoring/self-report | Blood glucose monitoring | ||||

| Support by educational booklets | Mentioned, but not referenced | Not mentioned | Mentioned, but not referenced | ||

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service | Lipid profile (TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C) | ||||

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behavioral changes | |||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results of the assessments included by the service | Lipid levels and adherence to pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals, follow-up plans, developing mutual treatment plans | |||||

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions | |||||

| Targeting health care professionals | |||||

| Pharmacists providing relevant information and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals | General practicionerb | Physician (treatment recommendations) | |||

| Pharmacists requesting that other health care professionals perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status | |||||

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals | |||||

| Part 3 | Krass I, et al.8 | Maguire TA, et al.9 | Mehuys E, et al.10 | ||

| Targeting patients | |||||

| Pharmacists providing one-to-one information or instructions to patients | Correct use of medicine, including adherence to treatment | Yes | Yes (hypoglycemic medication) | ||

| Health problem | Food care | Overall view of the health problem (diabetes) and its complications | |||

| Risk behaviors | PA, HD, SC, AC | SC | PA, HD, SC | ||

| Self-management | Treatment of hypo- and hyperglycemia | Reminder to visit the physician for eye and foot examinations | |||

| Self-monitoring/self-report | Blood glucose monitoring | Blood glucose monitoring | |||

| Support by educational booklets | Mentioned, but not referenced | Reference provided | Not mentioned | ||

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service | Glycemic control | ||||

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behavioral changes | Blood glucose monitora | Blood glucose monitora | |||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results of the assessments included by the service | Glycemic control | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals, follow-up plans, developing mutual treatment plans | Yes (treatment goals) | Yes (initiate nicotine replacement therapy) | |||

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions | |||||

| Targeting health care professionals | |||||

| Pharmacists providing relevant information and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals | Physicianb | ||||

| Pharmacists requesting that other health care professionals perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status | |||||

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals | |||||

| Part 4 | Sarkadi A, et al.11 | Sookaneknun P, et al.12 | Tsuyuki RT, et al.13,14 | ||

| Targeting patients | |||||

| Pharmacists providing one-to-one information or instructions to patient | Correct use of medicine, including adherence to treatment | Yes | Yes | ||

| Health problem | Factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension; hypertension complications | Major coronary heart disease risk factors; general strategies to prevent coronary heart disease | |||

| Risk behaviors | PA, HD, SC, AC | ||||

| Self-management | Make an appointment with primary care physician | ||||

| Self-monitoring/self-report | Self-report: dietary habits, physical exercise, medication intake, unusual symptoms | ||||

| Support by educational booklets | Mentioned, but not referenced | A reference provided; other materials mentioned, but not specified | |||

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service | Total cholesterol levels | ||||

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behaviors | Examples of lifestyle change (video); examples of typical faults with diet and treatment; information about diabetes complications (educational booklet) | Patient diary/self-report | |||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results of the assessments included by the service | Hypertension control | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals, follow-up plans, developing mutual treatment plans | Yes (follow-up visits) | ||||

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions | Healthy dietary habits, physical exercise, self-monitoring, diabetes treatment | ||||

| Targeting health care professionals | |||||

| Pharmacists providing relevant information and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals | Physician (treatment recommendations) | Primary care physician (medication history, coronary heart disease risk factors, TC, and treatment recommendations) | |||

| Pharmacists requesting that other health care professionals perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status | Cholesterol panel | ||||

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals | |||||

| Part 5 | Vrijens B, et al.15 | Zillich AJ, et al.16 | |||

| Targeting patients | |||||

| Pharmacists providing one-to-one information or instructions to patients | Correct use of medicine, including adherence to treatment | Yes | Yes | ||

| Health problem | Overall view of the health problem (hypertension) and its complications | ||||

| Risk behaviors | PA, HD, SC | ||||

| Self-management | |||||

| Self-monitoring/self-report | Home BP monitoring; self-report: hospitalizations; emergency room visits; physician visits | ||||

| Support by educational booklets | Mentioned, but not referenced | A reference provided; other materials mentioned, but not specified | |||

| Patients provided with written information derived from the assessments performed as part of the service | Adherence to pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Patients provided with support material to facilitate behaviors | Adherence aid devicea | Home BP monitora; patient diary/self-report | |||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing the results of the assessments included by the service | Adherence to pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Pharmacists and patients discussing and agreeing on goals, follow-up plans, developing mutual treatment plans | |||||

| Pharmacists facilitating patient group discussions | |||||

| Targeting health care professionals | |||||

| Pharmacists providing relevant information and/or treatment recommendations to other health care professionals | Physicians (home BP and treatment recommendations) | ||||

| Pharmacists requesting other health care professionals to perform clinical analysis to further evaluate patient’s health status | |||||

| Pharmacists discussing and agreeing on treatment plans with other health care professionals | Physician (adjustments in antihypertensive treatment) | ||||

aDevice details provided by the individual study authors.

bIndividual study authors declared that patients were referred to a health care professional as part of the service, but they did not clearly state what information was given. AC = alcohol consumption; BP = blood pressure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HD = healthy diet; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PA = physical activity; SC = smoking cessation; TC = total cholesterol; TG = triglycerides.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster V, Kelly BB, eds.. Promoting Cardiovascular Health in the Developing World: A Critical Challenge to Achieve Global Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celermajer DS, Chow CK, Marijon E, et al. . Cardiovascular disease in the developing world: prevalences, patterns, and the potential of early disease detection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1207-16. Available at: http://content.onlinejacc.org/article.aspx?articleID=1305793. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B, eds.. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard SL, Lux L, Lohr KN.. Healthcare Delivery Models for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. London: The Health Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, et al. . Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, et al. . Using the collaborative intervention planning framework to adapt a health-care manager intervention to a new population and provider group to improve the health of people with serious mental illness. Implement Sci. 2014;9:178. Available at: http://www.implementationscience.com/content/9/1/178. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillison F, Greaves C, Stathi A, et al. . ‘Waste the Waist’: the development of an intervention to promote changes in diet and physical activity for people with high cardiovascular risk. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):327-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amariles P, Sabater-Hernández D, García-Jiménez E, et al. . Effectiveness of Dader Method for pharmaceutical care on control of blood pressure and total cholesterol in outpatients with cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk: EMDADER-CV randomized controlled trial. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(4):311-23. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/abs/10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.4.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fornos JA, Andres NF, Andres JC, et al. . A pharmacotherapy follow-up program in patients with type-2 diabetes in community pharmacies in Spain. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(2):65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George J, McNamara K, Stewart K.. The roles of community pharmacists in cardiovascular disease prevention and management. Australas Med J. 2011;4(5):266-72. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3562935/. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabater-Hernández D, Moullin JC, Hossain LN, et al. . Intervention Mapping for developing pharmacy-based services and health programs: a theoretical approach. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(3):156-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blenkinsopp A, Anderson C, Armstrong M.. Systematic review of the effectiveness of community pharmacy-based interventions to reduce risk behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease. J Public Health Med. 2003;25(2):144-53. Available at: http://jpubhealth.oxfordjournals.org/con-tent/25/2/144.full.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheema E, Sutcliffe P, Singer DR.. The impact of interventions by pharmacists in community pharmacies on control of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(6):1238-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans CD, Watson E, Eurich DT, et al. . Diabetes and cardiovascular disease interventions by community pharmacists: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(5):615-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Correr CJ, Melchiors AC, de Souza TT, et al. . A tool to characterize the components of pharmacist interventions in clinical pharmacy services: the DEPICT project. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):946-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotta I, Salgado TM, Felix DC, et al. . Ensuring consistent reporting of clinical pharmacy services to enhance reproducibility in practice: an improved version of DEPICT. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(4):584-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotta I, Salgado TM, Silva ML, et al. . Effectiveness of clinical pharmacy services: an overview of systematic reviews (2000-2010). Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):687-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amariles P, Faus MJ, Jimenez-Martin J, et al. . [Effect of the Dader Method for pharmaceutical care on the cardiovascular risk of patients with cardiovascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease (EMDADER-CV): methods and general results]. Ars Pharm. 2008;49(Suppl 1):7-24. [Article in Spanish]. Available at: http://farmacia.ugr.es/ars/ars_web/. Accessed April 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali M, Schifano F, Robinson P, et al. . Impact of community pharmacy diabetes monitoring and education programme on diabetes management: a randomized controlled study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(9):e326-33. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03725.x/full. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krass I, Armour CL, Mitchell B, et al. . The Pharmacy Diabetes Care Program: assessment of a community pharmacy diabetes service model in Australia. Diabet Med. 2007;24(6):677-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehuys E, van Bortel L, De Bolle L, et al. . Effectiveness of a community pharmacist intervention in diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(5):602-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkadi A, Rosenqvist U.. Experience-based group education in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(3):291-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcao JA, Cabrita J.. Evaluation of a pharmaceutical care program for hypertensive patients in rural Portugal. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(6):858-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sookaneknun P, Richards RM, Sanguansermsri J, Teerasut C.. Pharmacist involvement in primary care improves hypertensive patient clinical outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(12):2023-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zillich AJ, Sutherland JM, Kumbera PA, Carter BL.. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study). J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1091-96. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1490290/. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eussen SR, van der Elst ME, Klungel OH, et al. . A pharmaceutical care program to improve adherence to statin therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(12):1905-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vrijens B, Belmans A, Matthys K, et al. . Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(2):115-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, et al. . Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study. J Card Fail. 2003;9(5):404-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maguire TA, McElnay JC, Drummond A.. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention based in community pharmacies. Addiction. 2001;96(2):325-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Teo KK, et al. . Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP): a randomized trial design of the effect of a community pharmacist intervention program on serum cholesterol risk. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(9):910-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Teo KK, et al. . A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol risk management: the Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP). Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1149-55. Available at: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=211442. Accessed April 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salgado TM, Correr CJ, Moles R, et al. . Assessing the implementability of clinical pharmacist interventions in patients with chronic kidney disease: an analysis of systematic reviews. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(11):1498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pintor-Marmol A, Baena MI, Fajardo PC, et al. . Terms used in patient safety related to medication: a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(8):799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crealey GE, McElnay JC, Maguire TA, O’Neill C.. Costs and effects associated with a community pharmacy-based smoking-cessation programme. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;14(3):323-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simpson SH, Johnson JA, Tsuyuki RT.. Economic impact of community pharmacist intervention in cholesterol risk management: an evaluation of the study of cardiovascular risk intervention by pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(5):627-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melchiors AC, Correr CJ, Venson R, Pontarolo R.. An analysis of quality of systematic reviews on pharmacist health interventions. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(1):32-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Appendix B References

- 1.Ali M, Schifano F, Robinson P, et al. . Impact of community pharmacy diabetes monitoring and education programme on diabetes management: a randomized controlled study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(9):e326-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amariles P, Faus MJ, Jimenez-Martin J, et al. . [Effect of the Dader Method for pharmaceutical care on the cardiovascular risk of patients with cardiovascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease (EMDADER-CV): methods and general results]. Ars Pharm. 2008; 49(Suppl 1):7-24. [Article in Spanish]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amariles P, Sabater-Hernandez D, Garcia-Jimenez E, et al. . Effectiveness of Dader Method for pharmaceutical care on control of blood pressure and total cholesterol in outpatients with cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk: EMDADER-CV randomized controlled trial. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(4):311-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, et al. . Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study. J Card Fail. 2003;9(5):404-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eussen SR, van der Elst ME, Klungel OH, et al. . A pharmaceutical care program to improve adherence to statin therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(12):1905-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fornos JA, Andres NF, Andres JC, et al. . A pharmacotherapy follow-up program in patients with type-2 diabetes in community pharmacies in Spain. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(2):65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcao JA, Cabrita J.. Evaluation of a pharmaceutical care program for hypertensive patients in rural Portugal. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(6):858-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krass I, Armour CL, Mitchell B, et al. . The Pharmacy Diabetes Care Program: assessment of a community pharmacy diabetes service model in Australia. Diabet Med. 2007;24(6):677-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maguire TA, McElnay JC, Drummond A.. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention based in community pharmacies. Addiction. 2001;96(2):325-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehuys E, van Bortel L, De Bolle L, et al. . Effectiveness of a community pharmacist intervention in diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(5):602-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkadi A, Rosenqvist U.. Experience-based group education in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(3):291-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sookaneknun P, Richards RM, Sanguansermsri J, Teerasut C.. Pharmacist involvement in primary care improves hypertensive patient clinical outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(12):2023-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Teo KK, et al. . Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP): a randomized trial design of the effect of a community pharmacist intervention program on serum cholesterol risk. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(9):910-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Teo KK, et al. . A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol risk management: the Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP). Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1149-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrijens B, Belmans A, Matthys K, et al. . Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(2):115-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zillich AJ, Sutherland JM, Kumbera PA, Carter BL.. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study). J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1091-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]