Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Drugs for inflammatory conditions are one of the highest expenditure therapeutic classes for health plans. Published literature for adherence, persistence, nonadherence risk factors, and health care costs are incomplete for newer biologic agents.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) examine differences in adherence, persistence, switch patterns, and health care costs among high-cost specialty anti-inflammatory medications and (b) suggest risk factors for nonadherence in rheumatoid arthritis.

METHODS:

In this exploratory retrospective cohort study, we used medical and pharmacy claims from 1.2 million enrollees in commercial health plans administrated by Premera Blue Cross, the largest not-for-profit health plan in the Pacific Northwest. We included members with rheumatoid arthritis who used the following high-cost disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, apremilast, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, sekukinumab, tocilizumab, tofacitinib, and ustekinumab. Adherence was calculated via medication possession ratio. Persistence was calculated as the amount of days between the initial fill and final fill plus days supply. Switch rates for adalimumab and etanercept were calculated as the percentage of members who switched to another target drug during the observation period. Direct medical costs (total health care costs) and health care costs excluding specialty agents were calculated using the net allowable amount per claim for the duration of each therapy. Adherence, persistence, and costs of care were also examined for concurrent methotrexate use for the most used target drugs.

RESULTS:

The most commonly used drugs were abatacept (n = 47), adalimumab (n = 226), and etanercept (n = 252). Nonadherence in certain subgroups was associated with higher mean monthly health care costs, excluding specialty agents (etanercept cohort: +$1,063 for nonmethotrexate users; +$492 for nonadherent methotrexate users), but adherence was associated with higher total health care costs (+$883 for etanercept). Relative to specialty pharmacies, retail was associated with 9% higher nonadherence. Concurrent methotrexate use was associated with higher persistence (+307 and +192 days with adalimumab and etanercept). The most commonly switched-to drug after adalimumab/etanercept was abatacept (n = 39).

CONCLUSIONS:

This exploratory study raises signals suggesting that retail pharmacies may be associated with higher nonadherence; nonadherence may be associated with increased health care costs, excluding specialty agents; adherence may increase total health care costs; and methotrexate use may be associated with increased persistence. Future research should confirm these findings.

What is already known about this subject

Inflammatory conditions are one of the most expensive therapeutic classes for payers, with an average prescription costing $3,587.83.

Overall medication nonadherence for inflammatory conditions is approximately 40%.

Nonadherence can reduce therapy effectiveness, which can lead to disease progression, treatment escalation, wastage, and higher medical costs.

What this study adds

Findings from this study support the value of specialty pharmacies.

This study provides evidence that retail pharmacy use may be a nonadherence risk factor.

Study results add to the evidence that supports the concurrent use and adherence of methotrexate with biologic therapy.

Anti-inflammatory and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are the cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment. Conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs), such as methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine, are commonly used as first-line therapy. However, patients commonly fail cDMARDs or have severe initial disease and require biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) such as abatacept (ABT), adalimumab (ADA), anakinra (ANK), certolizumab (CTZ), etanercept (ETN), golimumab (GOL), infliximab (IFX), sekukinumab (SEK), tocilizumab (TCZ), ustekinumab (UST), and rituximab (RTX) or a newer small molecule treatment named tofacitinib (TOF). Combinations of a specialty RA agent and MTX have been shown to have superior outcomes than either alone.1-21 DMARDs have revolutionized RA treatment because of exceptional symptom control and slowed disease progression.1,22 However, newer DMARDs have high acquisition costs and are consequently included in specialty tiers.

Inflammatory conditions are one of the top therapeutic classes for drug spending, with a per member per year cost of $118 for employer-sponsored plans in 2016, an 11.3% increase from 2015 to 2016, and another 15.3% increase from 2016 to 2017.23,24 Adherence to chronic therapies is often suboptimal, with low adherence as one of the most important factors for poor outcomes and increased costs.25-27 The World Health Organization reports that < 50% of patients take medications as prescribed.27 Additionally, up to 30% of prescriptions are never filled in the United States, which costs $100-$300 billion annually.26-28 Nonadherence can lead to poor outcomes, dose escalation, additional medications, and switches, which can lead to unnecessary adverse events, delayed recovery, and higher societal costs.25,27,28

Studies suggest that nonadherence in RA can range from 41%-75%, but there is a lack of real-world evidence for newer agents, such as TOF, GOL, and CTZ.29-32 In general, our understanding of adherence, persistence, and spending in this class is incomplete. The objective of this retrospective claims analysis was to explore differences in adherence, persistence, switch patterns, cost of care, and potential risk factors associated with secondary nonadherence in RA for high-cost anti-inflammatory medications.

Methods

Study Design

As part of a quality improvement effort, we performed a retrospective claims analysis with pharmacy and medical claims from 1.2 million members enrolled in commercial plans with Premera Blue Cross, the largest not-for-profit health plan in the Pacific Northwest. This analysis was exploratory with no a priori hypotheses, so results may be ad hoc. The period of observation for the analysis was January 1, 2013-December 31, 2015.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 30 years (to exclude juvenile idiopathic arthritis) with a diagnosis of RA and with no target drug claims in the previous 6 months. RA patients were identified using the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) codes: 714.0 (ICD-9-CM), M05.00-M05.9 (ICD-10-CM), and M06.00-M06.9 (ICD-10-CM). In addition, we restricted the sample to patients with continuous enrollment for ≥ 1.5 years and ≥ 1 year of continuous use for any target drug in order to assess outcomes in a stable population with longer duration of use. We included drugs costing $600 or more per month per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition of a specialty tier drug. Drugs were identified via generic code numbers (GCNs) and J-codes: TCZ (35486, J3262); CTZ (23471, 99615, J0717); ETN (23574, 52651, 97724, 98398, J1438); ADA (18924, 37262, 97005, 99439, J0135); IFX (61501, J1745); RTX (unspecified, J9310); GOL (22533, 22536, 34697, 35001, J1602); SEK (37788, 37789, unspecified); ANK (14867, unspecified); ABT (30289, J0129); APR (36172, 36173, 37756, unspecified); UST (28158, 28159, J3357); and TOF (33617, unspecified). Unspecified GCN/J-codes are for drugs that were not available through the medical or pharmacy benefit at the time of analysis. We excluded patients with active cancer and claims for dental and otological/ophthalmological services, since these costs would be exorbitant independent of RA care, and since these patients may have had gaps in therapy or less frequent fills during the study period because of these potentially confounding medical reasons. We also excluded drugs used by less than 10 members.

Claims Parameters

We obtained member enrollment characteristics (gender, date of birth, drug name, date of service, and polychronic/multimorbidity member indicator); prescription claim characteristics (GCN, quantity, total days of therapy, pharmacy name, ingredient cost, and retail code); and medical claim characteristics (J-codes, total units, and allowable cost). Multimorbidity is defined as ≥ 2 chronic conditions. We identified specialty pharmacies by manually searching pharmacy names for those with specialty contracts during the time horizon of the analysis, specifically Accredo and Walgreens Specialty.

Analysis

Adherence was calculated using medication possession ratio (MPR): total days supply divided by total days of eligibility, with a maximum of 1.0.33 Total days supply was calculated by summing the days supply of each target drug. Total days of eligibility was the length of time between the index claim and the last claim plus its last days supply. Individuals were considered adherent if MPR was ≥ 0.8 and nonadherent if MPR was < 0.8.33,34 MPR was only calculated for pharmacy claims due to an inability to obtain days supply data for infused products. Adherence was also calculated separately for MTX use. Drug persistence was defined as the time length of therapy until discontinuation, switch, or end of the study with a gap period of > 90 days, which has been used in other RA analyses.35-37

We calculated total health care costs as the mean of all allowable costs for medical claims and pharmacy claims for each individual patient per 28 days. Because our drugs of interest were expected to comprise a large portion of total health care costs, we also calculated health care costs per member per month, excluding the cost for specialty RA agents, representing the total health care costs net of specialty RA agents.

Other analyses included switch sequence patterns, MTX use, and nonadherence factors. Switch sequences were based on index claims and examined which target drug members switched to/from an index target drug. Switch rates were calculated for ADA/ETN and were reported as either index (percentage switching from ADA/ETN only if ADA/ETN was the first specialty agent treatment) or overall rates. MTX use was target drug specific and was determined if a patient had any MTX claims during the persistence period for each target drug. Concurrent MTX use was examined because combinations of MTX and a specialty RA agent have reported superior outcomes to either alone and are now commonly recommended.1-21

For statistical analyses of costs, persistence, and nonadherence, a 2-sample t-test assuming unequal variances was used, since the means of 2 continuous data parameters were assessed. Statistical analysis of adherence in retail versus specialty pharmacy used a 2 × 2 contingency table chi-squared test due to the comparison of categorical 2-variable data. The only confounding variable assessed was concurrent MTX use for ADA/ETN (due to a limited sample size for other drugs) and was analyzed via data stratification.

Estimates with P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board research criteria considered this study a quality improvement project, not research, and did not require human subjects approval. Our results are not necessarily generalizable.

Results

Included in the analysis were 456 members (101 male and 355 female) and 6,943 claims; 78% of all claims were filled by females (Table 1). Most claims occurred for patients aged 45-65 years. The most used drugs by patient and claim count were ETN (38% of claims), followed by ADA (35%) and ABT (5%; Table 1). ANK, APR, and UST were used by less than 10 members and were excluded from this analysis.

TABLE 1.

Member Characteristics and Results

| Member Count (% Female) | Median Age, Years | Total Claims (% Female) | Percentage Adherent (MPR ≥ 0.8)a | Top Switched-to Drugb | ADA Switch Rate | ETN Switch Rate | Retail Pharmacy Adherence | Specialty Pharmacy Adherence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA overall | 456 (77.9) | 50 | 6,943 (78) | 77% | ABA (n = 39) | 35% (n = 79) | 34% (n = 85) | 70% (n = 166)c | 79% (n = 414)c |

| Drug Name | |||||||||

| ABT | ADA | CTZ | ETN | GOL | IFX | RTX | TOF | TCZ | |

| Patient count | 47 | 226 | 27 | 252 | 27 | 38 | 34 | 19 | 28 |

| Claim count | 358 | 2,434 | 330 | 2,639 | 222 | 308 | 170 | 153 | 301 |

| Adherence (%)d | 70 | 77 | 75 | 76 | 95 | – | – | 83 | 71 |

a Members using more than 1 target drug had more than 1 data point for adherence, 1 per target prescription drug.

b Reflects top switched-to drug, excluding ADA or ETN.

c Some RA patients filled their drugs at unspecified locations excluding them from the retail or specialty analysis.

d Adherence was only calculated for prescription drugs.

ABT = abatacept; ADA = adalimumab; bDMARD = biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CTZ = certolizumab; ETN = etanercept; GOL = golimumab; IFX = infliximab; MPR = medication possession ratio; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; RTX = rituximab; TCZ = tocilizumab; TOF = tofacitinib.

As shown in Table 1, the top switched-to drug after ADA or ETN was ABT (n = 39). The mean time to switch to any drug was 244 days from ADA and 292 days from ETN. Median time to switch from ETN to ADA was 358 days (n = 25) and from ADA to ETN was 336 days (n = 18). Overall switch rates for ADA and ETN were 35% and 34%, respectively. In addition, index switch rates for ADA and ETN were 25% and 26%.

Adherence and Persistence

Mean adherence to any specialty RA agent was 77%. As shown in Table 1, mean adherence for specialty agents filled at retail pharmacies was lower than adherence for medications filled at specialty pharmacies (70% vs. 79%, P = 0.02). When examining ETN, there were 14% more adherent members in the specialty versus retail setting (P = 0.02). Table 1 displays the complete results for mean adherence rates. There was no statistically significant difference in adherence for other drugs, and no overall association between MTX and adherence was observed.

For the most commonly used drugs (ADA/ETN), concurrent MTX users experienced longer persistence by 307 days with ADA (P < 0.0005) and 192 days with ETN (P = 0.05) versus non-MTX users. There was no persistence difference in retail versus specialty between adherent and nonadherent ADA/ETN users.

Cost of Care Per 28 Days

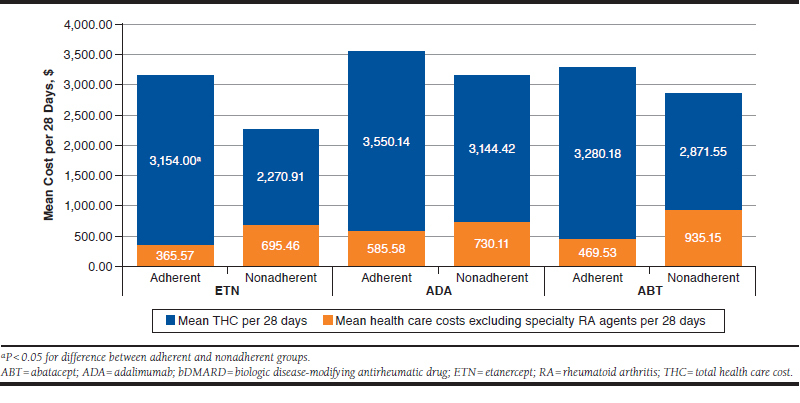

No differences were seen for health care costs excluding specialty RA agents between adherent and nonadherent patients for the most used drugs (ADA, ETN, and ABT; Figure 1). However, mean total health care costs was $883 higher for adherent members using ETN (P = 0.02) when excluding multimorbidity members.

FIGURE 1.

Non-Multimorbidity Adherence and Cost of Care for Top bDMARDs

Mean total health care costs for non-MTX users was $1,063 more with ETN (P = 0.02), compared with MTX users. In members already adherent to ADA/ETN, health care costs excluding specialty RA agents and adherence to MTX was also assessed. Patients nonadherent to MTX spent $492 more with ETN (n = 31, P = 0.05), with no difference in ADA users (n = 33, P = 0.57).

Among the most used drugs, only ETN patients filling at retail pharmacies had higher health care costs that excluded specialty RA agents versus specialty pharmacies. ETN users spent $503 more (P = 0.02) in retail versus specialty pharmacies.

Factors Associated with Nonadherence

Only the retail setting was associated with nonadherence. Patients obtaining medications in the retail setting were 9% more nonadherent versus patients obtaining medications in the specialty setting (P = 0.02). Gender, age, and multimorbidity were not significantly associated with adherence.

Discussion

In this exploratory retrospective cohort study of high-cost anti-inflammatory drugs in RA in a commercial health payer, we found potentially lower health care costs excluding specialty RA agents associated from MTX use, adherence to MTX, and specialty pharmacy use for those using ETN. We also identified a possible risk factor for nonadherence stemming from retail pharmacy use.

Age and gender trends match previous literature, with members predominantly female and aged approximately 50 years.38-40 The most common drugs were ADA and ETN, likely driven by Premera’s medical policy designating ADA and ETN as preferred formulary agents. This mimics market shares outside of Premera.23 However, market shares may change as evidence and policies move away from solely recommending sequential double tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) use before another specialty RA agent.1,41-49 The switch rates for ADA/ETN were similar to each other but were higher than those seen in other studies for ADA and ETN. Other publications cite ranges of around 11% for ETN and 18% for ADA.40, 50 However, 1 study did not reflect the U.S. population, and methodologies differed. The top nonpreferred switched-to drug was ABT, but significance is questionable since this only reflects 39 members, with most switches occurring to ADA/ETN (policy driven).

Nonadherence to any specialty RA agent was lower than in other U.S. insurance-based literature for inflammatory conditions.23 This may reflect a difference in Premera’s RA population but may also stem from an inclusion criterion that limited analysis to members with ≥ 1 year of use for any target drug, which may artificially increase adherence. MPR rates match other published adherence rates for ADA and ETN. However, a new study reported around 31%-36% RA adherence for TNFi over the first 2 years of therapy, conflicting with our observations. Although it did use MPR, this study included patients aged 18-29 years, which likely reduced adherence, since younger patients are known to be more nonadherent.37

It is important to note that this study also demonstrated an association between improved adherence and increased total health care costs. However, this trend matches other recently published literature.51 In the future, it is possible that additional biologic/biosimilar approvals may alleviate drug prices, mitigating any financial burden from improved adherence. Future research should examine if there is a trade-off between the higher drug costs from enhanced adherence and improved outcomes from a health care or societal perspective.

A recent study examining the effect of patient support programs with ADA reported slightly lower adherence rates compared with this study (67% for patient support programs and 59% for nonpatient support programs vs. 77%), but that study included more patients, combined various inflammatory conditions, and used different methodology.51 Adherence was observed to be higher in the specialty setting, matching proposed benefits of specialty pharmacies.52-54 That same study also found that the cohort of patient support programs had reduced direct medical costs, indirectly further supporting the cost-saving benefit of adherence to specialty agents in RA. Interventions that may drive the observed benefits of specialty pharmacies include education programs, coordinated mail-order service, care coordinators assisting with refill/cost management, and access to RA-trained pharmacists 24 hours a day.54

There was no difference in health care costs excluding specialty RA agents between nonadherent and adherent members using the most common drugs (ADA, ETN, and ABT). However, when limited to only members without multimorbidity, nonadherent individuals had higher health care costs, excluding specialty RA agents. One could speculate that additional comorbidities may lessen the financial ramifications of nonadherence to only RA medications, but such a hypothesis would need to be tested. Comorbidity stratification is warranted in future research.

The MTX analysis observed that MTX use alone was not associated with lower health care costs, excluding specialty RA agents, but adherence to MTX and ETN was associated with lower health care costs, excluding specialty RA agents, versus non-MTX users. This observation reaffirms a potential synergy of MTX and biologics in RA, which may be due to reduced antidrug antibodies and subsequent clearance.1-21

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. Although Premera Blue Cross is the largest health benefits provider in Washington State, because of the low prevalence of RA, we were still limited to a small sample. Since this was an exploratory analysis assessing multiple outcomes, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, so findings may be spurious. Future analyses would benefit from testing an a priori hypothesis and using larger member pools powered for statistical significance.

It is important to note that this is only 1 payer with 1 set of policies that prefers specific bDMARDs (ADA/ETN); policy preferences could affect results and limit generalizability. Furthermore, this analysis only included commercial members, further limiting generalizability.

Claims data have inherent limitations, since they provide a surrogate assessment for adherence (e.g., a filled prescription may not be administered). Moreover, claim data miss relevant clinical information (e.g., titrating regimens), which could affect results and prevent disease severity stratification. Future research would benefit from assessing additional parameters, such as regimen directions and disease severity metrics. This analysis was also unable to calculate adherence for medical claims due to unavailable days supply parameters for medical claims.

Conclusions

This study matches other cited age and gender trends in RA, suggests improved adherence from specialty pharmacies, and supports the value from concurrent MTX via improved persistence.22,30,36-40 For ETN users, this study suggests decreased health care costs (excluding specialty agents) from specialty pharmacy use, reduced total health care costs from concurrent MTX, and higher health care costs (excluding specialty agents) for non-MTX users or when adherent to ETN but nonadherent to MTX.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detert J, Pascal K. Biologic monotherapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biologics. 2015;9:35-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Hossain A, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Biologics or tofacitinib for rheumatoid arthritis in incomplete responders to methotrexate or other traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD012183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1081-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaneko Y, Atsumi T, Tanaka Y, et al. Comparison of adding tocilizumab to methotrexate with switching to tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to methotrexate: 52-week results from a prospective, randomised, controlled study (SURPRISE study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1917-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dougados M, Kissel K, Conaghan PG, et al. Clinical, radiographic and immunogenic effects after 1 year of tocilizumab-based treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis: the ACT-RAY study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(5):803-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuno H, Yoshida K, Ochiai A, Okamoto M. Requirement of methotrexate in combination with anti-tumor necrosis factoralpha therapy for adequate suppression of osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(12):2326-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab: relationship to anti-adalimumab antibodies and serum adalimumab concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):921-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Klareskog L, et al. Golimumab, a human antibody to tumour necrosis factor {alpha} given by monthly subcutaneous injections, in active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy: the GO-FORWARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):789-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kameda H, Kanbe K, Sato E, et al. Continuation of methotrexate resulted in better clinical and radiographic outcomes than discontinuation upon starting etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 52-week results from the JESMR study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1585-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kameda H, Ueki Y, Saito K, et al. Etanercept (ETN) with methotrexate (MTX) is better than ETN monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite MTX therapy: a randomized trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(6):531-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyrich KL, Symmons DP, Watson KD, et al. Comparison of the response to infliximab or etanercept monotherapy with the response to cotherapy with methotrexate or another diseasemodifying antirheumatic drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1786-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristensen LE, Kapetanovic MC, Gülfe A, et al. Predictors of response to anti-TNF therapy according to ACR and EULAR criteria in patients with established RA: results from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(4):495-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristensen LE, Saxne T, Nilsson JA, Geborek P. Impact of concomitant DMARD therapy on adherence to treatment with etanercept and infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a six-year observational study in southern Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(6):R174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2572-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, et al. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):22-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iannone F, Gremese E, Atzeni F, et al. Long-term retention of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy in a large Italian cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis from the GISEA registry: an appraisal of predictors. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(6):1179-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum MA, Koo D, Doshi JA. Measurement and rates of persistence with and adherence to biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2011;33(7):901-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabay C, Riek M, Scherer A, Finckh A; SCQM Collaborating Physicians. Effectiveness of biologic DMARDs in monotherapy versus in combination with synthetic DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis: data from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Registry . Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(9):1664-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahl K, Schuna AA. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: DiPiro J, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Express Scripts. 2016 drug trend report . Available at: http://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/drug-trend-report/previous-reports. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 24.Express Scripts 2017 drug trend report . Available at http://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/drug-trend-report/previous-reports. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 25.De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vera MA, Mailman J, Galo JS. Economics of non-adherence to biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(11):460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabaté E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf;jsessionid=AC9FED39F7F4630DF6896A04D8997A21?sequence=1. Accessed February 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Avoidable costs in U.S. healthcare: the $200 billion opportunity from using medicines more responsibly . June 2013. Available at: http://offers.premierinc.com/rs/381-NBB-525/images/Avoidable_Costs_in%20_US_Healthcare-IHII_AvoidableCosts_2013%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 29.Stolshek BS, Wade S, Mutebi A, De AP, Wade RL, Yeaw J. Two-year adherence and costs for biologic therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(8 Spec No.):SP315-SP321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, Gruben D, Bourret J, Koenig A. Primary nonadherence, associated clinical outcomes, and health care resource use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis prescribed treatment with injectable biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):209-18. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasma A, van’t Spijker A, Hazes JM, Busschbach JJ, Luime JJ. Factors associated with adherence to pharmaceutical treatment for rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(1):18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrold LR, Andrade SE. Medication adherence of patients with selected rheumatic conditions: a systematic review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;38(5):396-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fairman K, Motheral B. Evaluating medication adherence: which measure is right for your program? J Manag Care Pharm. 2000;6(6):499-504. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/pdf/10.18553/jmcp.2000.6.6.499. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee WJ, Briars L, Lee TA, Calip GS, Suda KJ, Schumock GT. Use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in children and young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(12):1201-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Blum MA, Von Feldt J, Hennessy S, Doshi JA. Adherence, discontinuation, and switching of biologic therapies in Medicaid enrollees with rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health. 2010;13(6):805-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calip GS, Adimadhyam S, Xing S, Rincon JC, Lee WJ, Anguiano RH. Medication adherence and persistence over time with self-administered TNF-alpha inhibitors among young adult, middle-aged, and older patients with rheumatologic conditions. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47(2):157-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tkacz J, Ellis L, Bolge SC, Meyer R, Brady BL, Ruetsch C. Utilization and adherence patterns of subcutaneously administered anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Ther. 2014; 36(5):737-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kern DM, Chang L, Sonawane K, et al. Treatment patterns of newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients from a commercially insured population. Rheumatol Ther. 2018;5(2):355-69 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu T, Mutebi A, Stolshek BS, Tan H. Cost of biologic treatment persistence or switching in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(8 Spec No.):SP338-SP345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottenberg J-E, Brocq O, Perdriger A, et al. Non–TNF-targeted biologic vs a second anti-TNF drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis in patients with insufficient response to a first anti-TNF drug. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1172-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manders SH, Kievit W, Adang E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of abatacept, rituximab, and TNFi treatment after previous failure with TNFi treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a pragmatic multi-centre randomised trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emery P, Gottenberg JE, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Rituximab versus an alternative TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed to respond to a single previous TNF inhibitor: SWITCH-RA, a global, observational, comparative effectiveness study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):979-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1114-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2793-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keystone El, Emery P, Peterfy CG, et al. Rituximab inhibits structural joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(2):216-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emery Pl, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1516-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrold LR, Reed GW, Shewade A, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with prior exposure to anti-TNF: results from the CORRONA registry. J Rheumatol. 2015. Jul;42(7):1090-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fleischmann R, van Adelsberg J, Lin Y, et al. Sarilumab and nonbiologic disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response or intolerance to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(2):277-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Degli Esposti L, Favalli EG, Sangiorgi D, et al. Persistence, switch rates, drug consumption and costs of biological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an observational study in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;9:9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin DT, Mittal M, Davis M, Johnson S, Chao J, Skup M. Impact of a patient support program on patient adherence to adalimumab and direct medical costs in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):859-67. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.16272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanson RL, Gannon MJ, Khamo N, Sodhi M, Orr AM, Stubbings J. Improvement in safety monitoring of biologic response modifiers after the implementation of clinical care guidelines by a specialty. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(1):49-67. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stockl KM, Shin JS, Lew HC, et al. Outcomes of a rheumatoid arthritis disease therapy management program focusing on medication adherence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(8):593-604. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/abs/10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.8.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tschida S, Aslam S, Khan TT, Sahli B, Shrank WH, Lal LS. Managing specialty medication services through a specialty pharmacy program: the case of oral renal transplant immunosuppressant medications. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(1):26-41. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/abs/10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]