Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 allows the purchase of health insurance through special marketplaces called “health exchanges.” The majority of individuals enrolling in the exchanges were previously uninsured, older, and sicker than other commercially insured members. Early evidence also suggests that exchange plan members use more costly specialty drugs compared with other commercially insured members.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) examine patient characteristics and specialty drug use for common chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) among exchange plan members compared with other commercially insured members and (b) explore variations in specialty drug use within exchange plans by metal tiers (bronze, silver, gold, and platinum), as well as across local markets.

METHODS:

This analysis included adults aged ≥ 18 years who were enrolled in exchange plans (exchange population) and other commercial health plans (nonexchange population). The primary outcome was the likelihood of using specialty drugs prescribed to treat common CIDs, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis. The adjusted likelihood of using CID specialty drugs was calculated from logistic regression controlling for prevalence of CIDs and other health risk factors.

RESULTS:

A total of 931,384 exchange plan members and 2,682,855 nonexchange plan members were included in the analysis. Compared with the nonexchange population, the exchange population was older, more likely to be female, had more comorbid conditions, but filled fewer prescriptions. The 2 groups were similar in terms of CID prevalence. The observed likelihood of CID specialty drug use was 20.0% lower in the exchange versus the nonexchange populations (341 users per 100,000 exchange members vs. 427 users per 100,000 nonexchange members; P < 0.001). Within the exchange population, the observed likelihood of CID specialty drug use was 132 per 100,000 bronze plan members (69.1% lower than nonexchange); 326 per 100,000 silver plan members (23.5% lower than nonexchange); 579 per 100,000 gold plan members (35.6% higher than nonexchange); and 672 per 100,000 platinum plan members (57.5% higher than nonexchange). All differences were statistically significant at P < 0.001. There were also large differences by local market, ranging from 49.1% lower to 75.8% higher CID use in the exchange population than in the nonexchange population. After adjustment, the exchange population was 16.6% less likely to use CID specialty drugs than the nonexchange population (P < 0.001). Large variation in specialty drug use within the exchange plan metal tiers was reduced. After adjustment, the higher use of CID specialty drugs among the exchange population in certain local plans was no longer statistically significant.

CONCLUSIONS:

Members insured through exchange plans were older and sicker than those with nonexchange plans, but they did not use more CID specialty drugs compared with the nonexchange population. Large variations were seen among the exchange plan metal tiers and by local markets, which were often related to the risk profiles of exchange plan enrollees.

What is already known about this subject

Members enrolled in exchange plans are older and sicker than those in other commercial plans, with the majority previously uninsured.

Members enrolled in exchange plans have higher overall health care use and spending than members in other commercial plans.

Specialty drugs are a small but costly drug category, and the few studies that have explored specialty drug use among the exchange population have shown higher use and spending for those drugs and a faster growth trend than among other commercial plan members.

What this study adds

Members enrolled in exchange plans had lower specialty drug use for common chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) relative to other commercial plan members.

Study results quantified the variations in CID specialty drug use between the exchange and other commercial plan populations across local markets, as well as across metal tiers within exchange plans.

With the introduction of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), individuals can purchase health insurance plans through federal- or state-run health insurance marketplaces called “health exchanges.” Enrollment in exchange plans increased from 8 million people in 2014 to 12.7 million in 2016 before dipping slightly to 12.2 million in 2017.1 Nearly 6 in 10 exchange plan members were previously uninsured, and they tended to be older and sicker than those with commercial insurance purchased outside the exchanges,2-4 prompting reports of higher overall costs for insuring this population.2

Specialty medications—loosely defined as high-cost drugs that are usually manufactured using advanced biotechnology and require special handling or administration (e.g., infusions)—are used for the treatment of complex conditions, such as rheumatologic conditions, psoriasis, cancer, growth hormone deficiency, and multiple sclerosis.5,6 Management of specialty drugs has been challenging for health insurers even among commercially insured populations because multiple high-cost agents become available in this category each year.7-9 Used by only 1%-2% of the population, specialty drugs accounted for more than one third of overall drug spending in the United States in 2014.5,10 While growth in spending for nonspecialty drugs has remained flat in recent years, spending for specialty drugs has risen at an alarming rate, with an increase of nearly 18% in 2015 alone, a trend that is expected to continue.5,10

Early evidence suggests that increases in specialty drug use by exchange plan members outpaced increases by those with commercial health insurance plans. Between March 2014 and March 2015, spending for specialty drugs increased 24% for the exchange population compared with 8% for the commercial plan population.11 Express Scripts, a leading pharmacy benefits manager, reported that between January and July 2014, exchange plan members were 8.7% more likely to fill prescriptions for specialty drugs and thus had 32.8% more per-member-per-month spending for specialty drugs than commercial plan members.12 However, another recent study found that there was no statistically significant difference in specialty drug spending when comparing exchange plan members with other commercially insured groups after adjusting for population demographics (age, sex, and geographic region),3 suggesting that speculation about the exchange population being undisciplined users of health care or having significant pent-up demand might be unwarranted.

Our study builds on previous evidence by supplementing specialty drug use accrued through pharmacy claims with claims billed through medical benefit and incorporating additional population-level characteristics, such as disease prevalence, into the analysis. We compared exchange plan members with other commercially insured members with respect to their adjusted likelihood of using specialty drugs for common chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs), such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis. We focused on specialty drugs used to treat common CIDs because they are among the most used and fastest growing categories of specialty drugs.13 We also analysed the variations in specialty drug use across different metal tier types and local markets.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective observational study using medical and pharmacy claims data from January 2014 to June 2015, which were the early years of exchange plan availability in the marketplace. Data were obtained from the HealthCore Integrated Research Environment, which consists of claims and eligibility data from Anthem health plans in 14 states.

This study was exempt from institutional review board review, since the researchers only accessed a limited dataset in full compliance with relevant provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Patient Population

The study included adults aged 18 years or older who were enrolled in an exchange plan or other commercial health plan. Exchange plans were defined as ACA-compliant health plans with a metal designation (platinum, gold, silver, or bronze) purchased through public or private exchanges. Members with such plans were grouped as the “exchange population.” Members in other fully insured commercial plans (excluding Medicare or Medicaid) were grouped as the “nonexchange population.”

The index date was defined as the earliest date in medical or pharmacy claims with a code for a CID specialty drug between July 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015 (the intake period; see Appendix A for the list of medications, available in online article). For members without claims for a CID specialty drug, a proxy index date was randomly assigned within the intake period. The average length of enrollment within the intake period was similar between the 2 groups (308 days for the exchange population and 306 days for the nonexchange population). All members were required to have at least 6 months of continuous enrollment in medical and pharmacy benefits before the index date to capture baseline characteristics.

Study Measures

The outcome measures were unadjusted and adjusted likelihood of using specialty drugs that are generally prescribed to treat common CIDs (Appendix A). Members who had at least 1 specialty drug claim of interest billed through either medical or pharmacy benefits during the intake period were designated as specialty drug users.

The baseline characteristics included prevalence of each CID (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis), using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes (Appendix B, available in online article); age; gender; comorbidity burden (defined by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index14 [ECI]); distinct Generic Product Identifier-8 medication count; number of outpatient visits; previous use of nonspecialty drugs to treat common CIDs; out-of-pocket (OOP) patient cost; and total health care spending (OOP patient cost and plan-paid cost). These characteristics were assessed during the 6 months before the index date.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics between the exchange and nonexchange plan populations were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Differences within the 4 exchange metal tiers were compared using a trend test for both types of variables. Descriptive measures associated with specialty drug use were provided as counts, percentages, and relative differences (RD) between the 2 groups (exchange vs. nonexchange populations).

To calculate the adjusted likelihood of specialty drug use, logistic regression models controlling for baseline characteristics (prevalence of each CID, age, gender, comorbidity burden, previous use of nonspecialty drugs for CIDs, and OOP patient cost) were used. Results were reported as counts, RD between the 2 groups, and odds ratios (ORs). The model with an exchange plan indicator as the independent variable was used to compare the likelihood of specialty drug use between the exchange and nonexchange populations. The model with an exchange plan product indicator (metal tier) as the independent variable was used to compare the likelihood of specialty drug use in the 4 exchange plan metal tiers compared with nonexchange plans.

Subanalysis was conducted within 5 local plans where exchange plan members had higher (10% or more) specialty drug use than nonexchange plan members. The threshold for significance was set at 0.05 for 2 sample comparisons, and Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the threshold for significance for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 931,384 members enrolled in exchange plans and 2,682,855 members in nonexchange plans who met the study criteria (Table 1). We observed significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 study populations. Compared with the nonexchange population, exchange plan members were older (mean age 45 years vs. 43 years, respectively, P < 0.001) and more likely to be female (52.7% vs. 49.0%, respectively, P < 0.001). Exchange plan members also had more comorbid conditions (mean ECI 0.57 vs. 0.54, respectively, P < 0.001) but filled a lower number of prescription drugs (mean count 2.3 vs. 2.5, respectively, P < 0.001) than nonexchange plan members. Prevalence of CIDs was similar between the 2 groups (1.41% exchange vs. 1.42% nonexchange, P = 0.705). For specific CIDs, exchange plan members had slightly higher prevalences of rheumatoid arthritis (0.48% vs. 0.45%, respectively, P = 0.001) and ulcerative colitis (0.24% vs. 0.22%, respectively, P = 0.001) and lower prevalences of Crohn’s disease (0.20% vs. 0.22%, respectively, P = 0.002) and psoriasis (0.47% vs. 0.50%, respectively, P < 0.001). Exchange and nonexchange plan members had similar prevalences of ankylosing spondylitis (0.04% vs. 0.05%, respectively, P = 0.187) and psoriatic arthritis (0.11% vs. 0.12%, respectively, P = 0.055). Previous use of nonspecialty drugs to treat common CIDs was lower among exchange plan members (18.3% vs. 20.4%, respectively, P < 0.001). Also, baseline health service utilization was lower among the exchange population than the nonexchange population. Outpatient visits per 1,000 enrollees was 4.8 among the exchange population and 5.2 among the nonexchange population (P < 0.001). Total health care spending was similar between the 2 groups ($2,792 exchange vs. $2,783 nonexchange, P = 0.633), and OOP patient cost was slightly higher among the exchange population ($527 exchange vs. $524 nonexchange, P = 0.013).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Exchange and Nonexchange Populations

| Characteristics | Exchange Plans n = 931,384 | Nonexchange Plans n = 2,682,855 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean, years (SD) | 45.0 (13.5) | 42.7 (14.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age category, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 18-44 | 411,397 (44.2) | 1,405,059 (52.4) | |

| 45-64 | 510,668 (54.8) | 1,194,535 (44.5) | |

| ≥65 | 9,319 (1.0) | 83,261 (3.1) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 490,649 (52.7) | 1,315,442 (49.0) | < 0.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 0.57 (1.1) | 0.54 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 647,288 (69.5) | 1,880,309 (70.1) | |

| 1-3 | 257,677 (27.7) | 733,876 (27.4) | |

| ≥4 | 26,419 (2.8) | 68,670 (2.6) | |

| Distinct GPI-8 medication count, mean (SD) | 2.3 (3.2) | 2.5 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic inflammatory conditions, n (%) | 13,157 (1.41) | 38,043 (1.42) | 0.705 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4,436 (0.48) | 12,059 (0.45) | 0.001 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 399 (0.04) | 1,240 (0.05) | 0.187 |

| Crohn’s disease | 1,849 (0.20) | 5,797 (0.22) | 0.002 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2,218 (0.24) | 5,867 (0.22) | 0.001 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1,006 (0.11) | 3,107 (0.12) | 0.055 |

| Psoriasis | 4,343 (0.47) | 13,335 (0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Previous use of nonspecialty drugs for CIDs, n (%) | 170,394 (18.3) | 546,983 (20.4) | < 0.001 |

| Outpatient visits per 1,000 enrollees, mean (SD) | 4.8 (8.9) | 5.2 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket patient cost, mean (SD), $ | 527 (1,167.3) | 524 (1,109.6) | 0.013 |

| Total health care spending, mean (SD), $ | 2,792 (15,330.8) | 2,783 (13,901.8) | 0.633 |

CID = chronic inflammatory disease; GPI = Generic Product Identifier; SD = standard deviation.

The largest proportion of the exchange population (42.8%) enrolled in silver plans; 30.2% enrolled in bronze plans; 21.4% enrolled in gold plans; and 5.7% enrolled in platinum plans (Table 2). Members who were enrolled in higher tier metal plans had higher prevalence of CIDs (any CID, as well as each specific CID); higher likelihood of using nonspecialty drugs for CIDs; and more comorbid conditions, prescription fills, outpatient visits, and total health care spending compared with members enrolled in the next lower tier metal plans (e.g., silver vs. bronze, gold vs. silver). For example, prevalence of any CID was 0.7% for bronze, 1.5% for silver, 2.0% for gold, and 2.4% for platinum (trend test P < 0.001). Mean ECI was 0.3 for bronze plans, 0.7 each for silver and gold, and 0.8 for platinum (trend test P < 0.001). Members enrolled in gold plans were most similar to average nonexchange plan members in terms of age (mean age 43.6 years gold plans, 42.7 years nonexchange plans) and gender (51.1% female gold plans, 49.0% female nonexchange plans). Those members who were enrolled in silver plans were most similar to average nonexchange plan members in terms of prevalence of CIDs (prevalence of any CIDs 1.5% silver plans, 1.4% nonexchange plans); previous nonspecialy drug use for CIDs (19.8% silver plans, 20.4% nonexchange plans); health care utilization (mean number of prescription fills 2.5 in both groups, outpatient visits 5.1 per 1,000 enrollees silver plans, and 5.2 per 1,000 enrollees nonexchange plans); and spending (total spending $2,963 silver plans, $2,783 nonexchange plans).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Exchange and Nonexchange Plan Members, by Metal Tier

| Exchange Plans | Nonexchange Plans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronze | Silver | Gold | Platinum | ||

| Sample size, n (%) | 280,829 (30.2) | 398,415 (42.8) | 199,458 (21.4) | 52,682 (5.7) | 2,682,855 (100) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 45.2 (13.5) | 45.7 (13.5) | 43.6 (13.4) | 44.2 (13.4) | 42.7 (14.1) |

| Age category, n (%) | |||||

| 18-44 | 121,467 (43.3) | 166,398 (41.8) | 98,445 (49.4) | 25,087 (47.6) | 1,405,059 (52.4) |

| 45-64 | 157,688 (56.2) | 228,556 (57.4) | 97,778 (49.0) | 26,646 (50.6) | 1,194,535 (44.5) |

| ≥65 | 1,674 (0.6) | 3,461 (0.9) | 3,235 (1.6) | 949 (1.8) | 83,261 (3.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 145,179 (51.7) | 215,916 (54.2) | 101,886 (51.1) | 27,668 (52.5) | 1,315,442 (49.0) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.1) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 224,674 (80.0) | 262,975 (66.0) | 128,127.0 (64.2) | 31,512 (59.8) | 1,880,309 (70.1) |

| 1-3 | 52,748 (18.8) | 121,838 (30.6) | 64,397.0 (32.3) | 18,694 (35.5) | 733,876 (27.4) |

| ≥4 | 3,407 (1.2) | 13,602 (3.4) | 6,934.0 (3.5) | 2,476 (4.7) | 68,670 (2.6) |

| Distinct GPI-8 medication count, mean (SD) | 1.4 (2.2) | 2.5 (3.3) | 3.0 (3.6) | 3.4 (3.8) | 2.5 (3.2) |

| Chronic inflammatory conditions, n (%) | 2,027 (0.7) | 5,939 (1.5) | 3,921 (2.0) | 1,270 (2.4) | 38,043 (1.4) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 636 (0.23) | 2,086 (0.52) | 1,328 (0.67) | 386 (0.73) | 12,059 (0.45) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 52 (0.02) | 186 (0.05) | 123 (0.06) | 38 (0.07) | 1,240 (0.05) |

| Crohn’s disease | 214 (0.08) | 758 (0.19) | 640 (0.32) | 237 (0.45) | 5,797 (0.22) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 321 (0.11) | 979 (0.25) | 668 (0.33) | 250 (0.47) | 5,867 (0.22) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 142 (0.05) | 464 (0.12) | 305 (0.15) | 95 (0.18) | 3,107 (0.12) |

| Psoriasis | 792 (0.28) | 1,953 (0.49) | 1,214 (0.61) | 384 (0.73) | 13,335 (0.5) |

| Previous use of nonspecialty drugs for CIDs, n (%) | 32,374 (11.5) | 78,909 (19.8) | 45,860 (23) | 13,251 (25.2) | 546,983 (20.4) |

| Outpatient visits per 1,000 enrollees, mean (SD) | 2.8 (6.3) | 5.1 (9.1) | 6.1 (10.2) | 7.5 (12.0) | 5.2 (9.1) |

| Out-of-pocket patient cost, mean (SD), $ | 527 (1,398.6) | 501 (1,073.8) | 603 (1,054.2) | 434 (837.3) | 524 (1,109.6) |

| Total plan allowed costs, mean (SD), $ | 1,617 (12,513.7) | 2,963 (15,762.6) | 3,552 (16,717.9) | 4,883 (19,214.3) | 2,783 (13,901.8) |

CID = chronic inflammatory disease; GPI = Generic Product Identifier; SD = standard deviation.

Likelihood of Specialty Drug Use

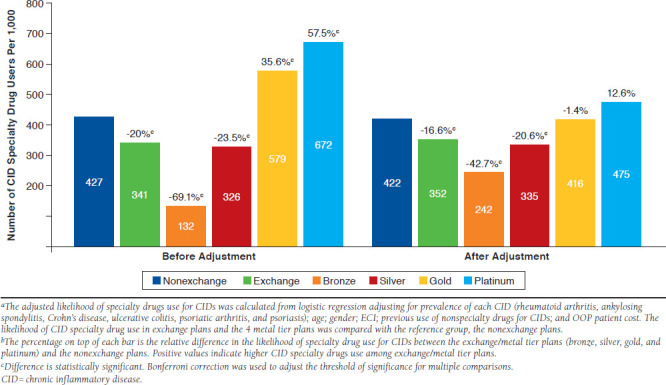

The unadjusted likelihood of using CID specialty drugs in the exchange population was 20.0% lower than in the nonexchange population, with 341 users per 100,000 exchange plan members versus 427 users per 100,000 nonexchange plan members (OR = 0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.77-0.83; P < 0.001; Figure 1). The difference in unadjusted likelihood of CID specialty drug use between the exchange and nonexchange populations varied significantly by metal plan tiers. The likelihood of CID specialty drug use was 132 per 100,000 members in bronze plans (69.1% lower than nonexchange plans); 326 per 100,000 members in silver plans (23.5% lower than nonexchange plans); 579 per 100,000 members in gold plans (35.6% higher than nonexchange plans); and 672 per 100,000 members in platinum plans (57.5% higher than nonexchange plans). All differences were statistically significant at P < 0.001.

FIGURE 1.

Specialty Drugs Use for CIDs by Exchange and Nonexchange Populations and by Metal Plan Before and After Adjustmenta,b

After adjustment for member baseline characteristics, the likelihood of CID specialty drug use was 352 per 100,000 exchange plan members versus 422 per 100,000 nonexchange plan members (Figure 1). The relative difference between the exchange and nonexchange populations in likelihood of CID specialty drug use was slightly reduced after adjustment but remained statistically significant (-20.0% before adjustment to -16.6% after adjustment; adjusted odds ratio = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.71-0.79; P < 0.001, where higher positive RD signifies greater use among the exchange population). In contrast, the large variation in likelihood of CID specialty drug use by metal plan was greatly reduced after adjustment. Members enrolled in gold and platinum plans had similar likelihood of CID specialty drug use compared with the nonexchange population after adjustment (gold plan RD -1.4%, P = 0.552; platinum plan RD 12.6%, P = 0.008). The RD in the likelihood of CID specialty drug use decreased from -69.1% before adjustment to -42.7% after adjustment for bronze plan members when compared with nonexchange plan members but was still statistically significant (P < 0.001). The RD in the likelihood of CID specialty drug use changed slightly for silver plans before and after adjustment compared with nonexchange plans (RD before adjustment -23.5%, P < 0.001; RD after adjustment -20.6%, P < 0.001).

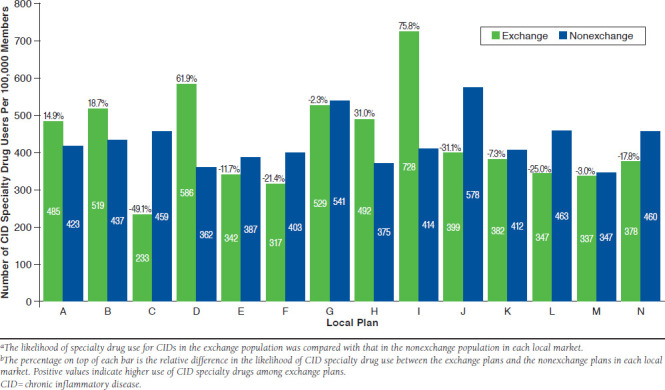

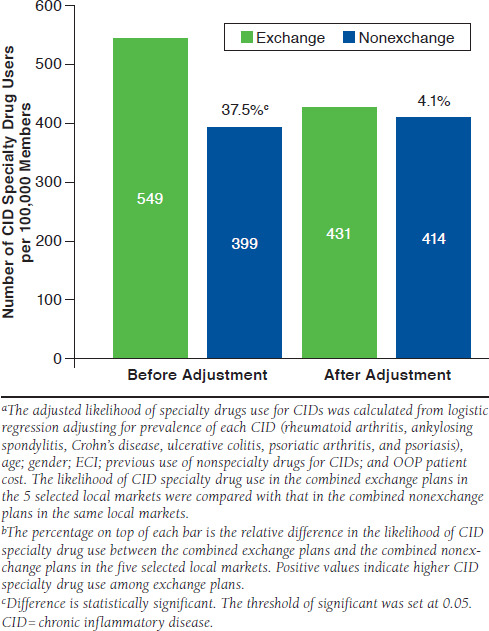

We also observed large variations in the likelihood of CID specialty drug use by local market (Figure 2). The RD in the likelihood of using CID specialty drugs between the exchange and nonexchange populations ranged from -49.1% to 75.8%. Five of the 14 local plans had much higher (10% or more) use of specialty drugs in the exchange population than in the nonexchange population. The RD decreased from 37.5% to 4.1% among the 5 highest-use local plans and became statistically nonsignificant after adjustment (before adjustment P < 0.001; after adjustment P = 0.191; Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Local Plan Variation in CID Specialty Drugs Usea,b

FIGURE 3.

CID Specialty Drug Use Rate by Exchange and Nonexchange Members Within Selected Local Plans Before and After Adjustmenta,b

Discussion

This real-world study focused on specialty drugs primarily prescribed to treat common CIDs because these agents are among the most used and expensive category of specialty drugs. We found that the exchange population was 20.0% less likely to use CID specialty drugs compared with the nonexchange population, and this trend remained after accounting for baseline characteristics, such as prevalence of each specific CID, age, gender, comorbid conditions, previous use of nonspecialty drugs for CIDs, and OOP patient cost. To our knowledge, no other research to date has presented the adjusted medication use in the exchange population after accounting for population risk factors such as disease prevalence, comorbidity, or health care utilization. In addition, we presented the magnitude of the variations in specialty drug use by exchange plan metal tier and by local market. For example, the likelihood of CID specialty drug use was 5.1 times higher for exchange members enrolled in platinum plans compared with those enrolled in bronze plans. Furthermore, the likelihood of CID specialty drug use varied widely among local plans, ranging from 75.8% higher to 49.1% lower in the exchange population compared with the nonexchange population. After adjustment, however, the observed variations were considerably diminished.

Our study found that the exchange population was less likely to have any specialty drug fills for CIDs than the nonexchange population. Although a 2014 report by Express Scripts found that, overall, exchange plan members filled 8.7% more specialty drugs compared with nonexchange plan members, that result may have been driven primarily by use for conditions other than CIDs. For example, prescriptions for human immunodeficiency virus treatments accounted for more than 50% of specialty drugs fills among exchange plan members compared with 20% among nonexchange plan members.12

Our results are consistent with a previous study by Donohue et al. (2015),3 which reported less medication use (including traditional and specialty drugs) among the exchange population for most major chronic disease categories. We also found that exchange plan members remained less likely to have any specialty drug fills for CIDs than nonexchange plan members after risk adjustment.

It is less clear why the exchange population was less likely to fill medications. Less generous benefit designs of exchange plans (such as higher cost sharing) may have discouraged medication use to a certain extent. Another explanation might be that alternative, nonspecialty pharmacological treatments for CID that patients might be trying first—for example, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as methotrexate, steroids, or immunosuppressants—are used more commonly among the exchange population, since they are more likely to be new to insurance coverage and potentially are in the process of trying nonspecialty, less costly options first.

Because we observed that exchange plan members were actually less likely to use nonspecialty drugs for CIDs than nonexchange plan members, we concluded that the benefit design theory might be more plausible. Further studies evaluating total use and cost by specific condition among exchange members can provide useful insight into whether this speculation holds true.

In the subanalysis of 5 selected local plans where the exchange population was much more likely to use CID specialty drugs, we applied risk adjustment to assess the potential effectiveness of utilization management practices. In this analysis, the relative difference changed from moderate (37.5%) to minimal (4.1%) after adjustment, indicating limited opportunities for managing utilization by health plans.

The wide variations in baseline characteristics and ultimately in the use of specialty drugs by metal tier may reflect patient self-selection, where sicker patients tend to enroll in more generous plans. In our study, members enrolled in platinum plans had 2.4 times the comorbid conditions, 2.5 times the number of prescription fills, 3.3 times the prevalence of any CIDs, and incurred 3.0 times higher total health care spending than members in bronze plans. The substantial differences in the likelihood of using CID specialty drugs across the 4 metal tiers were largely reduced after adjusting for CID prevalence and other health status factors.

Similarly, the variation in use of CID specialty drugs between exchange and nonexchange plans across local plans was highly correlated with their population risk profiles. We observed that in local plans where the prevalence of CIDs was higher among exchange plan members, the likelihood of specialty drug use was always higher in the exchange plans (correlation: 0.86, P < 0.001; data not shown).

More interestingly, we observed that the magnitude of variation in CID specialty drug use across different local plans within the exchange population was much larger than that within the nonexchange population. The rate ratio of using CID specialty drugs was 3.12 when comparing the highest utilization plan to the lowest local utilization plan within the exchange population; that rate ratio was smaller, at only 1.67, within the nonexchange population. The magnitude of variation in use across plans among the exchange population could present a challenge for insurance companies to correctly project and price out future health care needs and costs for the exchange population. Further studies are needed to look into the extent of variations in use and cost for specialty drugs within exchange plans.

Because more than half of the exchange population was previously uninsured,4 there is little information on their health status and health needs. The early experience under the ACA offers a unique opportunity to conduct in-depth assessments of this population. Further studies are needed to investigate the use and cost for other specialty drug subsets to better understand whether the tendency for reduced use of specialty drugs among the exchange population is consistent across different drugs types after risk adjustment and whether benefit design plays a similarly important role, as it did in our study.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations to consider. First, our results are subject to bias because of unmeasured confounders, such as benefit design, formulary differences, income, subsidies, and disease severity. For example, coinsurance rates for high-cost specialty drugs in exchange plans are higher than cost sharing in commercial plans, and the exchange population may face other restrictions on access above and beyond high specialty drug cost sharing (e.g., narrow physician/hospital networks).15 This limitation served to bias our results in the exchange population downward.16

Second, while we accounted for previous nonspecialty drug use for CIDs in the analysis, it was apparent that these drugs were used for disease indications other than CIDs, given the high-use rate of these drugs in our study population. This situation could have potentially biased our results but with minimal influence (we compared the results with and without adjustment for this variable; data not shown).

Third, the requirement of 6 months continuous enrollment may have introduced bias, since it likely resulted in a disproportionate exclusion of members in exchange plans. Fourth, our findings are based on the use of specialty drugs for a specific group of conditions (CIDs) and might not be generalizable to differences in overall specialty drug use.

Finally, our analysis is based on data from Anthem plans in 14 states and may not necessarily be representative of all commercially insured members across the United States, although the 14 plan states are geographically dispersed.

Conclusions

Members insured through exchange plans were older and sicker than those members with nonexchange plans, but they did not use more CID specialty drugs compared with other commercially insured members. Large variations were seen within the 4 metal tiers of exchange plans, with the majority of the variation related to the risk profiles of exchange plan enrollees. Large variation was also seen between exchange and nonexchange plans by local market.

APPENDIX A. Specialty Drugs Mostly Prescribed for Chronic Inflammatory Diseases

| Drug Name |

|---|

| Abatacept |

| Adalimumab |

| Alefacept |

| Anakinra |

| Apremilast |

| Belimumab |

| Canakinumab |

| Certolizumab pegol |

| Etanercept |

| Golimumab |

| Infliximab |

| Rilonacept |

| Secukinumab |

| Tocilizumab |

| Tofacitinib citrate |

| Ustekinumab |

| Vedolizumab |

APPENDIX B. CID Diagnosis Description and Codes

| CID | ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Code |

|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 714.0x, 714.1x, 714.2x |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 720.0x |

| Crohn’s disease | 555.xx |

| Ulcerative colitis | 556.xx |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 696.0x |

| Psoriasis | 696.1x |

CID = chronic inflammatory disease; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Health insurance marketplaces 2017 open enrollment period. Final enrollment report: November 1, 2016-January 31, 2017. March 15, 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2017-Fact-Sheet-items/2017-03-15.html. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 2.Blue Cross Blue Shield Association . The health of America report. Newly enrolled members in the individual health insurance market after health care reform: the experience from 2014 and 2015. March 20, 2016. Available at: https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/newly-enrolled-members-individual-health-insurance-market-after. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 3.Donohue JM, Papademetriou E, Henderson RR, et al. Early marketplace enrollees were older and used more medication than later enrollees; marketplaces pooled risk. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1049-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamel L, Norton M, Levitt L, et al. Survey of non-group health insurance enrollees. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 19, 2014. Available at: http://kff. org/health-reform/report/survey-of-non-group-health-insurance-enrollees/. Accessed November 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tu H, Samuel DR. Limited options to manage specialty drug spending. Res Brief. 2012;22:1-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UnitedHealth Center for Health Reform & Modernization . The growth of specialty pharmacy: current trends and future opportunities. Issue brief. April 2014. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/~/media/uhg/pdf/2014/unh-the-growth-of-specialty-pharmacy.ashx. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 7.The growing cost of specialty pharmacy—is it sustainable? AJMC.com. February 18, 2013. Available at: http://www.ajmc.com/payer-perspectives/0218/the-growing-cost-of-specialty-pharmacyis-it-sustainable. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 8.Herrick DM. Specialty drugs and pharmacies. National Center for Policy Analysis. Policy report no. 355. May 22, 2014. Available at: www.ncpa.org/pdfs/st355.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CVS Health . Specialty pipeline: blockbusters on the horizon. Insights executive briefing. Issue 5. 2016. Available at: http://insights.cvshealth.com/sites/default/files/cvs-health-insights-executive-briefing-specialty-pipeline-blockbusters-on-the-horizon-march-2016.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 10.Express Scripts . Express Scripts 2015 drug trend report. March 2016. Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0ahUKEwim6MHRjPHXAhVJ5WMKHZFqA7IQFgg0MAE& url=https%3A%2F%2Flab.express-scripts.com%2Flab%2F~%2Fmedia%2Fe2 c9d19240e94fcf893b706e13068750.ashx&usg=AOvVaw05w9WK7XFt9CQ-sMnzDY_H. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 11.Express Scripts . Exchange pulse report, June 2015. July 1, 2015. Available at: http://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/publications/exchange-pulse-public-exchanges-report-june-2015. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 12.Express Scripts . Exchange pulse report, October 2014. October 13, 2014. Available at: ab.express-scripts.com/lab/publications/exchange-pulse-public-exchanges-report-october-2014. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 13.Blue Cross Blue Shield Association . The health of America report. The growth in specialty drug spending from 2013 to 2014. May 2016. Available at: https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/Specialty-Rx-HoA-Report.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 14.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoonveld E, Coyle B, Markham J. Impact of ACA on the dinner-for-three dynamic. Clin Ther. 2015;37(4):733-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam S, Chen X, Richards T, Ruggieri AP, Sylwestrzak G.. Specialty drug use among ACA members: the case of chronic inflammatory diseases. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(10-a Suppl):S81 [Abstract M18]. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/abs/10.18553%2Fjmcp.2016.22.10-a.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]