Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis. The primary symptom of OA—pain—increases the disease burden by negatively affecting daily activities and quality of life. Opioids are often prescribed for treating pain in patients with OA but have questionable benefit-risk profiles. There is limited evidence on the economic impact of pain severity and opioid use among patients with OA.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) evaluate the association of pain severity with health care resource utilization (HRU) and costs among patients with knee/hip OA and (b) characterize the association of opioid use with HRU and costs while controlling for pain severity.

METHODS:

Using deterministically linked health care claims data and electronic health records from the Optum Research Database, this retrospective cohort study included commercial and Medicare Advantage Part D enrollees who were diagnosed with knee/hip OA during the January 1, 2010-December 31, 2016 time period and had ≥ 1 pain score (11-point Likert scale: 0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain) between the first OA diagnosis date and October 2016. The index date was the date of the evaluated pain score; HRU and costs were observed over the 3-month postindex period. For patients with multiple pain scores, each episode required a 3-month post-index follow-up period. Generalized estimating equation models, adjusted for multiple observation panels per patient and baseline variables that may contribute to HRU and costs (age, sex, race/ethnicity, region, insurance type, integrated delivery network, body mass index, pain medication use, provider specialty, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and other select comorbid conditions), were used to estimate all-cause and OA-related costs expressed as per patient per month (PPPM). Comparisons were performed for moderate (score 4-6) and severe (score 7-10) pain episodes versus no/mild pain episodes (score 0-3) and those with baseline opioid use versus those without.

RESULTS:

Included were 35,861 patients with knee/hip OA (mean age 66.5 years; 64.7% women) who had 70,716 pain episodes (58% mild, 23% moderate, 19% severe, and 37.0% with baseline opioid use). When controlling for other potential confounding factors, moderate/severe pain episodes were associated with higher all-cause and OA-related HRU than mild pain episodes. Relative to mild pain episodes, moderate/severe pain episodes were also associated with significantly higher adjusted average all-cause PPPM costs ($1,876/$1,840 vs. $1,602), and OA-related PPPM costs ($550/$577 vs. $394; all P < 0.05). Baseline opioid use was associated with significantly higher all-cause PPPM costs versus no opioid use (mild, $1,735 vs. $1,492; moderate, $2,034 vs. $1,755; severe, $2,100 vs. $1,643, all P < 0.001), and a higher likelihood of incurring OA-related costs relative to those without (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

These results provide evidence of the economic impact of opioid use and inadequate pain control by demonstrating that increased pain severity and opioid use in patients with OA were independently associated with higher HRU and costs. Additional studies should confirm causality between opioid use and HRU and costs, taking into consideration underlying OA characteristics.

What is already known about this subject

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, and the presence of pain, which is the primary symptom of OA, increases the disease burden by interfering with daily activities and quality of life.

Clinical guidelines suggest evaluation of the benefit-risk profile for individual patients when prescribing opioids.

There is limited information on the economic impact of pain severity and opioid use among patients with OA.

What this study adds

Among patients with OA, higher levels of pain severity and use of opioids were associated with higher health care resource utilization and costs, with the greatest economic impact among those with severe pain using opioids.

There is a need for management strategies that reduce pain and health care resource utilization costs among patients with OA.

Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, has been estimated to affect approximately 31 million individuals in the United States.1,2 The prevalence of OA more than doubled between 1999 (6.6%) and 2014 (14.3%), which may be a result of the aging of the population and changes in lifestyle, such as obesity.2 OA is associated with a significant patient-reported burden, including reductions in function and health-related quality of life, and an economic burden due to substantial health care resource utilization (HRU) and costs, with higher burdens among those with more severe disease.3-6

Pharmacologic management of OA is symptomatically driven, with the goals of reducing pain, which is the primary symptom, and improving function.7 The presence of pain in patients with OA increases the disease burden by further interfering with daily activities and resulting in excess HRU and costs relative to OA patients without pain.8

Drugs from a variety of classes are used for the management of OA pain; opioids are one of the treatment options and are generally recommended for intense or refractory pain and for those who do not respond to first-line treatment or have contraindications to other analgesics.7,9 Although there is little evidence supporting their long-term effectiveness, there is a strong dose-dependent risk for serious harms.10 These harms, which include not only misuse, abuse, and dependence but also side effects that have been reported in approximately 20% of patients treated with opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain, can result in increased HRU and costs.10-12 Thus, the benefitharm profile for the individual patient has to be carefully evaluated by the prescribing physician.13

In contrast to the economic studies of opioid misuse/abuse, there is limited real-world evidence of the impact of pain severity and opioid use on HRU and costs among patients with OA. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to evaluate the association of pain severity with HRU and costs among patients with knee and/or hip OA and to characterize the association of opioid use with HRU and costs when controlling for pain severity. We hypothesized that patients with moderate to severe OA pain have higher HRU and costs than those with mild pain. Similarly, adjusting for pain severity, patients who used opioids would have higher HRU and costs relative to those who did not.

Methods

Data Source and Population

The study sample for this retrospective cohort study was derived from adult commercial and Medicare Advantage Part D enrollees with deterministically linked health care claims data and electronic health records (EHR) from the Optum Research Database. The integrated database is nationally representative of the United States and consists of enrollment, inpatient and outpatient medical claims, pharmacy claims, and laboratory results. In addition, clinical measures captured in EHR during routine clinical care were available. These measures included pain scores, enabling assessment of pain severity. All data are deidentified and are fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

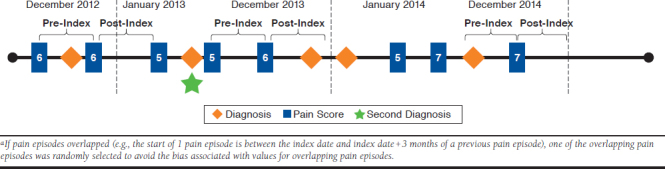

For inclusion, patients were required to have ≥ 2 claims for OA separated by ≥ 30 days during the study period (January 1, 2010-December 31, 2016) and ≥ 1 pain scores recorded on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain) between the diagnosis date and October 2, 2016. Claims for OA were for those with a diagnosis of OA in the knee or hip or diagnosis of OA unspecified plus diagnosis of pain in the knee or hip; all diagnoses were based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM) codes (Appendix A, available in online article). Because of the episodic nature of pain, pain episodes were created for patients based on their pain score records. The index date was the date of the evaluated pain score, and continuous enrollment for 3 months pre-index (baseline) and post-index (follow-up) was required for inclusion in the analysis; a 3-month time frame was used based on opioid-use guidelines that recommend evaluating the benefits and harms of therapy every 3 months or less.13 Patients could contribute multiple pain episodes, and in those cases, each episode required a 3-month post-index follow-up period. In the event that pain episodes overlapped (e.g., the start of 1 pain episode was between the index date and index date + 3 months of a previous pain episode), one of the overlapping pain episodes was randomly selected to avoid the potential for selection bias and bias associated with values for overlapping pain episodes (Appendix B, available in online article).

Patients were excluded if they had ≥ 1 medical claim during the study period with a diagnosis for any of the following comorbid conditions associated with the presence of pain and functional limitations and/or potential use of opioids that may reduce the ability to assess the outcomes of interest: pregnancy; malignancies; spinal cord tumor; and non-OA inflammatory disease, such as infectious arthritis, gout, Paget’s disease, pseudogout, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Outcomes

Data on all-cause and OA-related HRU were observed over the 3-month post-index period for the resource categories of hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient office visits, and other outpatient visits. OA-related HRU was defined as any claim having ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes (Appendix A) in the primary or secondary position. Combined health plan and patient paid amounts were analyzed. Allcause and OA-related health care costs were calculated and included pharmacy costs as well as costs for the above HRU categories. OA-related pharmacy costs included the following drugs: nonselective and selective prescription strength nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), duloxetine, glucosamine, acetaminophen, chondroitin sulfate, intraarticular corticosteroid injections, intra-articular hyaluronates, topical capsaicin, gabapentin, and pregabalin.7,14 All costs were adjusted to 2016 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.15

Statistical Analysis

All statistical comparisons controlled for within subject correlation inherent in the current study design. Unadjusted pairwise comparisons between categoric pain scores for binary measures were conducted using a Rao-Scott chi-square test, and for continuous measures, ordinary least squares regressions were used to produce P values estimated from robust standard errors.16 Estimates of all-cause and OA-related HRU and costs, expressed as per patient per month (PPPM; episode-level costs divided by 3 to account for the 3-month episode duration), were derived using generalized estimating equations, which adjusted for multiple observation panels per patient and variables that may contribute to HRU and costs. All models controlled for the same variables, including baseline age, sex, race, ethnicity, region, insurance type, integrated delivery network, body mass index, pain medication use, provider specialty, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and other select comorbid conditions. The log link along with the appropriate distribution for the measure (negative binomial for utilization and gamma for costs) were employed with an independent covariance structure. Comparisons versus mild (score 0-3) pain episodes were performed separately for moderate (score 4-6) and severe (score 7-10) episodes and for those with baseline opioid use versus those without. To estimate the impact of baseline opioid use on overall pain, regardless of severity level, the models were run with pain severity and baseline opioid use as 2 independent variables, and for impact at each level, an interaction term was included in the model. Incremental costs were estimated using the recycled prediction method, in which the average expenditures for each comparison group were derived based on the generalized estimating equations point-estimates for each beta and sampling routine.17 The 95% upper and lower confidence limits for the estimated mean costs (UCLM and LCLM, respectively) and cost differences and the P values were estimated with bootstrapped samples of 1,000 iterations with replacement.18

Results

Population

A total of 35,861 patients with knee/hip OA were identified who met all criteria for analysis (mean age 66.5 years; 64.7% women; Table 1). These patients had 70,716 pain episodes available for analysis, of which 57.6% of the episodes were of mild pain severity, 23.4% were moderate, and 19.1 % were severe. Overall, opioid use was reported for 37.0% of the pain episodes during the baseline period, with most of the use consisting of short-acting opioids (98.4% of episodes relative to 9.8% of episodes with long-acting opioid use).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | Patients (N = 35,861) | Total Pain Episodes (N = 70,716) | Episodes by Pain Severity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n = 40,697) | Moderate (n = 16,550) | Severe (n = 13,469) | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.5 (12.6) | 67.4 (12.5) | 69.0 (12.0)a,b | 65.3 (12.5)c | 64.9 (12.9) |

| Age group, years, n (%) | a,b | ||||

| 18-35 | 390 (1.1) | 616 (0.9) | 234 (0.6) | 186 (1.1) | 196 (1.5) |

| 36-40 | 453 (1.3) | 796 (1.1) | 287 (0.7) | 281 (1.7) | 228 (1.7) |

| 41-50 | 2,772 (7.7) | 4,907 (6.9) | 2,171 (5.3) | 1,415 (8.6) | 1,321 (9.8) |

| 51-64 | 11,938 (33.3) | 22,842 (32.3) | 11,803 (29.0) | 6,141 (37.1) | 4,898 (36.4) |

| 65-74 | 9,917 (27.7) | 19,424 (27.5) | 11,682 (28.7) | 4,300 26.0) | 3,442 (25.6) |

| ≥ 75 | 10,391 (29.0) | 22,131 (31.3) | 14,520 (35.7) | 4,227 (25.5) | 3,384 (25.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 23,199 (64.7) | 47,259 (66.8) | 26,244 (64.5)a,b | 11,234 (67.9)b | 9,781 (72.6) |

| Race, n (%) | a,b | b | |||

| Caucasian | 29,985 (83.6) | 59,640 (84.3) | 35,751 (87.9) | 13,754 (83.1) | 10,135 (75.3) |

| African American | 4,241 (11.8) | 8,395 (11.9) | 3,604 (8.9) | 2,116 (12.8) | 2,675 (19.9) |

| Other/unknown | 1,635 (4.6) | 2,681 (3.8) | 1,342 (3.3) | 680 (4.1) | 659 (4.9) |

| Ethnicity | a,b | b | |||

| Hispanic | 1,043 (2.9) | 2,025 (2.9) | 887 (2.2) | 532 (3.2) | 606 (4.5) |

| Not Hispanic | 32,912 (91.8) | 65,923 (93.2) | 38,411 (94.4) | 15,280 (92.3) | 12,232 (90.8) |

| Unknown | 1,906 (5.3) | 2,768 (3.9) | 1,399 (3.4) | 738 (4.5) | 631 (4.7) |

| Region, n (%) | a,b | b | |||

| Northeast | 1,908 (5.3) | 3,274 (4.6) | 1,750 (4.3) | 822 (5.0) | 702 (5.2) |

| Midwest | 20,312 (56.6) | 43,720 (61.8) | 27,552 (67.7) | 9,346 (56.5) | 6,822 (50.7) |

| South | 11,415 (31.8) | 19,472 (27.5) | 9,037 (22.2) | 5,331 (32.2) | 5,104 (37.9) |

| West | 2,218 (6.2) | 4,237 (6.0) | 2,352 (5.8) | 1,047 (6.3) | 838 (6.2) |

| Other | 8 (< 0.1) | 13 (< 0.1) | 6 (< 0.1) | 4 (< 0.1) | 3 (< 0.1) |

| Insurance type, n (%) | a,b | b | |||

| Commercial | 15,664 (43.7) | 28,631 (40.5) | 15,341 (37.7) | 7,714 (46.6) | 5,576 (41.4) |

| Medicare | 20,197 (56.3) | 42,085 (59.5) | 25,356 (62.3) | 8,836 (53.4) | 7,893 (58.6) |

| Integrated delivery network, n (%) | a,b | b | |||

| Yes | 30,206 (84.2) | 61,673 (87.2) | 36,628 (90.0) | 14,151 (85.5) | 10,894 (80.9) |

| No | 5,655 (15.8) | 9,043 (12.8) | 4,069 (10.0) | 2,399 (14.5) | 2,575 (19.1) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), n | 32.2 (8.0), 45,350 | 31.9 (7.8), 26,771a,b | 32.7 (8.1), 10,630 | 32.9 (8.6), 7,949 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | – | 0.51 (1.03) | 0.54 (1.07)a | 0.46 (0.96)c | 0.51 (1.01) |

| Baseline opioid use, n (%) | 26,162 (37.0) | 12,444 (30.6)a,b | 7,196 (43.5)b | 6,522 (48.4) | |

| Long-acting opioid | – | 2,553 (3.6) | 814 (2.0)a,b | 863 (5.2)c | 876 (6.5) |

| Short-acting opioid | – | 25,750 (36.4) | 12,286 (30.2)a,b | 7,066 (42.7)b | 6,398 (47.5) |

aP < 0.001 versus moderate.

bP < 0.001 versus severe.

cP < 0.05 versus severe.

SD = standard deviation.

Pain Severity

Statistically significant differences were observed across the pain severity episodes on all demographic variables (Table 1), including lower mean age and a higher proportion of women at higher pain severity levels. Among the clinical variables, body mass index was higher at moderate and severe pain levels relative to mild pain (both P < 0.001) and both long-acting and short-acting opioid use was higher at higher pain severity levels (P < 0.001).

Frequency of all-cause HRU was higher with moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes across resource categories except for outpatient visits, which was only significantly higher for moderate versus mild pain (Table 2). Relative to moderate pain episodes, severe pain episodes had significantly higher rates of all-cause ED visits and outpatient prescriptions (both P < 0.001) but a significantly lower rate of hospitalizations (P < 0.05). All-cause units of resource use PPPM were also higher with moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes. In particular, a longer length of stay and more units PPPM of ED visits and outpatient visits were observed with moderate and severe pain episodes compared with mild pain episodes (all P < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Episode-Level Health Care Resource Utilization, Stratified by Pain Severity

| Resource Category | Mild (n = 40,697) | Moderate (n = 16,550) | Severe (n = 13,469) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause resource use | |||

| Frequency of use post-index, % | |||

| ED visits | 23.7a,c | 30.4c | 38.5 |

| Outpatient visits | 97.3d | 97.9 | 97.6 |

| Hospitalizations | 9.9a,b | 11.7b | 11.0 |

| Outpatient prescriptions filled | 83.4a,c | 90.2c | 92.1 |

| Units used PPPM, mean (SD) | |||

| ED visits | 0.13 (0.36)a,c | 0.17 (0.42)c | 0.22 (0.48) |

| Outpatient visits | 1.91 (1.68)a,c | 2.10 (1.78) | 2.07 (1.69) |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 0.39 (2.13)b,d | 0.44 (2.17) | 0.46 (2.31) |

| OA-related resource use | |||

| Frequency of use post-index, % | |||

| ED visits | 1.2a,c | 1.9c | 3.3 |

| Outpatient office visits | 29.0a,c | 35.6c | 38.2 |

| Hospitalizations | 4.5a | 5.8c | 4.8 |

| Units used PPPM, mean (SD) | |||

| ED visits | 0 (0.04)a,c | 0.01 (0.06)c | 0.01 (0.10) |

| Outpatient visits | 0.20 (0.61)a,c | 0.28 (0.76) | 0.27 (0.64) |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 0.16 (1.32)b,d | 0.19 (1.42) | 0.20 (1.55) |

aP < 0.001 versus moderate.

bP < 0.05 versus severe.

cP < 0.001 versus severe.

dP < 0.05 versus moderate.

ED = emergency department; OA = osteoarthritis; PPPM = per patient per month; SD = standard deviation.

Although the rate of OA-related hospitalizations was highest in the moderate pain episodes (5.8% relative to 4.5% and 4.8% for mild and severe, respectively; both P < 0.001), the rates of use of other resource categories were statistically significantly higher among moderate and severe pain episodes compared with mild pain episodes (P < 0.05; Table 2). The units used PPPM were statistically significantly higher among moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes for all OA-related resource categories with the exception of inpatient stays in the severe category, as was the length of stay (all P < 0.05).

Mean unadjusted total all-cause resource costs PPPM were statistically significantly higher in moderate ($1,972) and severe ($1,918) pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes ($1,533; both P ≤ 0.001; Table 3). Although hospitalization costs were significantly higher with moderate ($846) and severe ($780) pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes ($576; both P ≤ 0.001), costs of outpatient visits were significantly higher for moderate ($736) relative to both mild ($658; P ≤ 0.001) and severe ($681; P < 0.05) episodes. All-cause pharmacy costs increased with greater pain severity, from $111 PPPM for mild pain episodes to $140 and $197 PPPM for moderate and severe pain episodes, respectively, with all pairwise comparisons showing statistical significance (P < 0.001). OA-related health care costs were statistically significantly higher in moderate and severe pain episodes, $610 and $544, respectively, compared with $400 for mild pain episodes (both P ≤ 0.001), with hospitalizations the main driver of these costs.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted Episode-Level Health Care Resource Utilization Costs, Stratified by Pain Severity

| Resource Category | Mean (SD) Cost (PPPM), $ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n = 40,697) | Moderate (n = 16,550) | Severe (n = 13,469) | |

| All-cause costs, total | 1,533 (3,644)a,b | 1,972 (4,631) | 1,918 (4,006) |

| ED visits | 62 (222)a,b | 80 (245)c | 104 (280) |

| Outpatient visits | 658 (1,299)a | 736 (2,145)d | 681 (1,258) |

| Hospitalizations | 576 (3,065)a,b | 846 (3,701) | 780 (3,286) |

| Pharmacy | 111 (624)a,b | 140 (730)b | 197 (973) |

| OA-related costs, total | 400 (2,025)a,b | 610 (2,443)d | 544 (2,287) |

| ED visits | 2 (33)b,c | 3 (44) | 4 (41) |

| Outpatient visits | 70 (367)a,b | 92 (424) | 84 (356) |

| Hospitalizations | 297 (1,933)a,b | 456 (2,317) | 394 (2,164) |

| Pharmacy | 9 (50)b,c | 24 (416)d | 35 (418) |

aP ≤ 0.001 versus moderate.

bP ≤ 0.001 versus severe.

cP < 0.05 versus moderate.

dP < 0.05 versus severe.

ED = emergency department; OA = osteoarthritis; PPPM = per patient per month; SD = standard deviation.

The generalized estimating equations regression analysis showed that significantly higher adjusted total all-cause health care costs PPPM were observed with moderate ($1,876; LCLM $1,818, UCLM $1,933; P < 0.001) and severe pain episodes ($1,840; LCLM $1,774, UCLM $1,906; P < 0.001) relative to mild pain episodes ($1,602; LCLM $1,567, UCLM $1,639). Estimated differences were $275 PPPM (LCLM $209, UCLM $341; P < 0.001) between mild and moderate pain episodes, and $239 PPPM (LCLM $160, UCLM $316: P < 0.001) between mild and severe pain episodes. For adjusted total OA-related health care costs PPPM for mild ($394; LCLM $375, UCLM $417), moderate ($550; LCLM $516, UCLM $590), and moderate pain episodes ($577; LCLM $533, UCLM $624), the estimated differences compared with mild pain episodes showed significantly higher costs of moderate and severe pain episodes, $156 PPPM (LCLM $114, UCLM $197) and $182 (LCLM $131, UCLM $233) PPPM higher, respectively (both P < 0.001).

Opioid Use

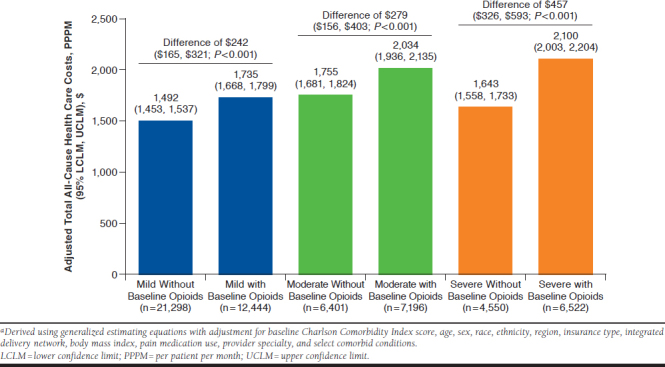

When stratified by baseline opioid use, adjusted total all-cause health care costs PPPM were higher among moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes among both opioid users and nonopioid users (Figure 1). Controlling for pain severity and other potential confounding factors (listed in Methods), baseline opioid use overall had significantly higher all-cause health care costs relative to no baseline pain prescription medication use (estimated cost ratio 1.18 [95% CI = 1.14-1.23]; P < 0.001). For comparisons at each severity level (Figure 1), the bootstrapped difference between those with and without baseline opioid use was $242 (LCLM $165, UCLM $321) for mild patients, $279 (LCLM $156, UCLM $403) for moderate patients and $457 (LCLM $326, ULCM $593) for severe patients (all P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted Total All-Cause Health Care Costs (PPPM) by Pain Severity and Opioid Usea

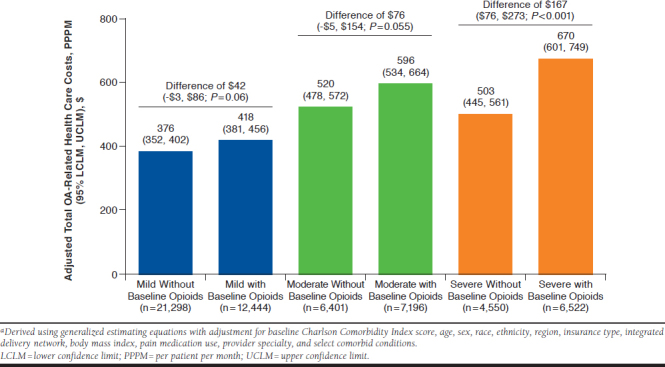

Adjusted total OA-related health care costs PPPM were higher among moderate and severe pain episodes with baseline opioid use relative to mild pain episodes, regardless of baseline opioid use (Figure 2). When controlled for pain severity, baseline opioid use was associated with a higher likelihood of incurring OA-related health care costs relative to no opioid use at baseline (odds ratio 1.25 [95% CI = 1.19-1.31]; P < 0.001). However, comparisons of baseline opioid use versus no opioid use within pain severity episodes showed that higher costs with baseline opioid use was statistically significant only for severe pain episodes, with a bootstrapped difference of $167 (LCLM $76, ULCM $273; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted Total OA-Related Health Care Costs (PPPM) by Pain Severity and Opioid Usea

Discussion

Although pain is the primary symptom of OA and results in higher HRU and health care costs associated with this disease,8 the economic impact of pain by level of severity has not been extensively studied.5 The current analysis is the first to provide real-world evidence of the economic burden associated with varying pain severity. The results suggest that in patients with OA, the presence of moderate or severe pain is associated with higher HRU and associated costs than among those with mild pain. Furthermore, the results of this study demonstrated that the use of opioids was also associated with a greater economic burden: higher health care costs were observed with baseline opioid use at each pain severity level and overall after adjusting for pain severity and other potential confounding factors.

Consistent with what may be expected for an OA population, the study sample in the current analysis was primarily female and an older demographic; however, there were statistically significant differences in demographics across the pain severity episodes. In particular, mean age was lower and the proportion of women was higher with increasing levels of pain severity, possibly reflecting differences in pain perception among different demographic subpopulations.19,20

The overall rate (37%) of pain severity episodes with baseline opioid use is similar to the previously reported high rate of use for this drug class in patients with OA,21-24 despite consistent evidence suggesting that the effectiveness of opioids for the management of OA pain is similar to that of NSAIDs.25,26 Baseline use of opioids was significantly higher in pain episodes of greater severity. Short-acting opioids use comprised the majority of opioid use (98.4% of pain episodes). Shortacting opioids are generally used as rescue pain medications or on an “as needed” basis and are considered safer than long-acting opioids, especially for older adults.27 However, the manner of their use in the current study (i.e., alone or in combination with other opioids or analgesics) was not determined.

During the 3-month post-index period, all-cause HRU was statistically significantly higher, both for rate of use and units used, among moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes across all resource categories except for other outpatient visits. Significantly higher OA-related HRU was generally observed with moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain episodes across resource categories. These patterns of HRU were paralleled by their associated unadjusted health care costs, both for all-cause and OA-related costs, and total health care costs were significantly higher for moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild. Notably, although OA-related pharmacy costs were also significantly higher for moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild, these costs were low ($9-$35 PPPM) and comprised only a small proportion of total OA-related costs, 2.3%-6.5%.

After adjusting for relevant baseline characteristics, the estimated total all-cause costs PPPM were substantial across all levels of severity, with incremental costs estimated to be significantly higher, by 17% and 15% with moderate and severe pain episodes, respectively, relative to mild pain episodes. Total all-cause costs, when annualized ($19,224-$22,512), are at the higher end of the range of total annual health care costs reported in a recent systematic review of the economic burden of OA28; however, the reported cost range in that review was broad ($1,442-$21,335). Total OA-related health care costs accounted for 25%-31% of all-cause costs, with incremental costs estimated to be significantly higher with moderate and severe pain episodes relative to mild pain by 39% and 46%, respectively. It was noted that although the unadjusted rates of both all-cause and OA-related hospitalizations were highest in moderate pain episodes, there was no significant difference in all-cause and OA-related health care costs between moderate and severe pain episodes.

When adjusted for relevant baseline characteristics and pain severity, baseline use of opioids was associated with significantly higher total all-cause health care costs at each pain severity level, with these opioid users also more likely, overall, to incur OA-related health care costs than those without baseline pain prescription medications. Higher health care costs associated with opioid use relative to no opioid use have previously been reported in patients with fibromyalgia,29,30 although some of that opioid use was long term. Our results are also consistent with the incrementally higher costs associated with opioid use in a nationally representative sample of patients with OA.31 It may be hypothesized that higher costs in patients using opioids are likely to result, at least in part, from additional health care–seeking behavior due to poorer outcomes in these patients, as also reported in the nationally representative sample.31

The use of opioids at baseline in 44% and 48% of moderate and severe pain episodes, respectively, may indicate potentially suboptimal pain management. However, the observed poorer outcomes in these cohorts may reflect, at least in part, common concerns associated with use of opioids, such as constipation, that may be exacerbated in an older population.32 In this regard, it should also be noted that opioid use in medically complex patients who are characterized by comorbid conditions and polypharmacy, both of which are common in the OA population, could potentially increase the risk of adverse events and drug-drug interactions.25 This in turn may lead to greater HRU and costs. Taken together, these observations reaffirm that while opioids remain an important component in the management of chronic noncancer pain, their use requires evaluation of their benefits and risks as currently recommended and consideration of the potential for higher HRU and costs.13 These factors may be especially relevant to the management of OA pain. Although increasing evidence suggests limited effectiveness of opioids in OA and an association of opioid use with greater functional impairment in subjects with OA that encompasses physical, social, and cognitive functions,3 there is limited real-world evidence of the economic impact of opioids.26,33 The association of opioid use with poorer outcomes and higher costs appears to be consistent with pain in OA that arises from multiple pathways and does not necessarily correlate with radiographic disease and suggests the need for effective and targeted pain management strategies.34

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. Although claims-based analyses, such as the current study, that rely on the use of diagnostic codes for cohort identification may be subject to errors in coding, the requirement of ≥ 2 diagnostic codes for OA was used to minimize such errors and to improve the accuracy of identifying patients with OA. However, use of ≥ 2 codes may also represent a form of selection bias, since it is possible that patients with OA and only 1 diagnostic code may have characteristics different from the currently evaluated population. Another form of selection bias is that the study included only patients who had pain scores available.

Other limitations were an inability to definitively attribute opioid prescribing to OA pain and lack of the ability to control for unobserved variables, including potential opioid tolerance or abuse and patient disease characteristics such as disease severity. Similarly, pain scores could not be definitively attributed to OA pain. Furthermore, because patients with joint surgery were not excluded, it is possible that pain and/or use of opioids may have overlapped with the surgery. Because the study evaluated HRU and costs over a 3-month time horizon, the long-term economic impact of pain severity/opioid use are still unknown. The large cohorts may also have resulted in statistically significant differences that are not necessarily clinically meaningful.

Finally, because the current study is a retrospective observational study, causality of pain severity and opioid use on HRU and costs cannot be determined because of confounding of unobserved factors. Thus, the findings should be interpreted as being associative.

Conclusions

This observational analysis demonstrated that compared with mild pain episodes, moderate or severe pain episodes were associated with significantly higher all-cause HRU and costs. Furthermore, when controlling for pain severity, opioid use at baseline was associated with significantly higher all-cause costs relative to no opioid use, with opioid users also more likely to incur OA-related health care costs than those without. These results provide evidence that opioid use has a measurable and significant economic impact and suggest the need for alternative pain management strategies that can alleviate pain symptoms while reducing total HRU use and costs among patients with OA. Additional studies should confirm causality between opioid use and HRU and costs, further accounting for underlying OA characteristics, and characterize the reasons for the higher HRU and costs among the OA patients who use opioids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge E. Jay Bienen, PhD, for medical writing support during development of this manuscript, and StemScientific (an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc) for editorial support.

APPENDIX A. International Classification of Diseases Codes Used for Identifying the Study Population

| Diagnosis | ICD-9-CM Code | ICD-10-CM Code |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis of the knee or hip | 715.x5, 715.x6 | M151, M152, M160, M1610, M1611, M1612, M162, M1630, M1631, M1632, M164, M1650, M1651, M1652, M166, M167, M169, M170, M1710, M1711, M1712, M172, M1730, M1731, M1732, M174, M175, M179 |

| Osteoarthritis unspecified | 715.00, 715.09, 715.10, 715.18, 715.20, 715.28, 715.30, 715.38, 715.80, 715.89, 715.90, 715.98 | M150, M150, M153, M158, M158, M159, M159, M1990, M1990, M1990, M1990, M1991, M1991, M1993, M1993 |

| Pain in the knee or hip | 719.45, 719.46 | M25551, M25552, M25559, M25561, M25562, M25569 |

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

APPENDIX B. Example of Analyzed Pain Episodesa

REFERENCES

- 1.Cisternas MG, Murphy L, Sacks JJ, Solomon DH, Pasta DJ, Helmick CG. Alternative methods for defining osteoarthritis and the impact on estimating prevalence in a US population-based survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(5):574-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J, Mendy A, Vieira ER. Various types of arthritis in the United States: prevalence and age-related trends from 1999 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):256-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotlarz H, Gunnarsson CL, Fang H, Rizzo JA. Insurer and out-of-pocket costs of osteoarthritis in the US: evidence from national survey data. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3546-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(7):437-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dibonaventura MD, Gupta S, McDonald M, Sadosky A, Pettitt D, Silverman S. Impact of self-rated osteoarthritis severity in an employed population: cross-sectional analysis of data from the national health and wellness survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadosky AB, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Lionberger DR. Relationship between patient-reported disease severity in osteoarthritis and self-reported pain, function, and work productivity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(4):R162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. . American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dibonaventura MD, Gupta S, McDonald M, Sadosky A. Evaluating the health and economic impact of osteoarthritis pain in the workforce: results from the National Health and Wellness Survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. . OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. . The effectiveness and risks of longterm opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of opioid adverse events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1046-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipman A, Webster L. The economic impact of opioid use in the management of chronic nonmalignant pain. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(10):891-99. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.10.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofat N, Harrison A, Russell MD, et al. . The effect of pregabalin or duloxetine on arthritis pain: a clinical and mechanistic study in people with hand osteoarthritis. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2437-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Measuring price change in the CPI: Medical care. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 16.Rao JNK, Scott AJ. The analysis of categorical data from complex surveys: chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1981;76:221-30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Estimating marginal and incremental effects on health outcomes using flexible link and variance function models. Biostatistics. 2005;6(1):93-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med. 2000;19(23):3219-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elboim-Gabyzon M, Rozen N, Laufer Y. Gender differences in pain perception and functional ability in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. ISRN Orthop. 2012;2012:413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrom C, Bair E, Maixner W, et al. . Demographic predictors of pain sensitivity: results from the OPPERA Study. J Pain. 2017;18(3):295-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct medical costs of patients with osteoarthritis in usual care: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2011; 14(4):497-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger A, Bozic K, Stacey B, Edelsberg J, Sadosky A, Oster G. Patterns of pharmacotherapy and health care utilization and costs prior to total hip or total knee replacement in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(8):2268-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):550-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright EA, Katz JN, Abrams S, Solomon DH, Losina E. Trends in prescription of opioids from 2003-2009 in persons with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(10):1489-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith H, Bruckenthal P. Implications of opioid analgesia for medically complicated patients. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(5):417-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. . Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):872-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. ; the American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie F, Kovic B, Jin X, He X, Wang M, Silvestre C. Economic and humanistic burden of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of large sample studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(11):1087-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Painter JT, Crofford LJ, Butler JS, Talbert J. Healthcare costs associated with chronic opioid use and fibromyalgia syndrome. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2014;6(6):e177-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margolis J, Masters ET, Cappelleri JC, Smith DM, Faulkner S. Evaluating increased resource use in fibromyalgia using electronic health records. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:675-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao X, Shah D, Gandhi K, et al. . Opioid use, pain interference with activities, and their associated healthcare costs and wage loss in a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized adults with osteoarthritis in the United States [abstract M15]. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(4-a Suppl):S88. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/pdf/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.issue-4-a. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webster LR. Opioid-induced constipation. Pain Med. 2015;16 (Suppl 1): S16-S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah D, Zhao X, Gandhi K, et al. . Opioid use, pain interference with activities, and their associated burden in a nationally representative sample of adults with osteoarthritis in the United States (U.S.): results of a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis [abstract 276]. Pain Med. 2018;19(4):893-94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrot S. Osteoarthritis pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(1):90-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]