Abstract

During the past decade, payment models for the delivery of health care have undergone a dramatic shift from focusing on volume to focusing on value. This shift began with the Affordable Care Act and was reinforced by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which increased the emphasis on payment for delivery of quality care. Today, value-based care is a primary strategy for improving patient care while managing costs.

This shift in payment models is expanding beyond the delivery of health care services to encompass models of compensation between payers and biopharmaceutical manufacturers. Value-based contracts (VBCs) have emerged as a mechanism that payers may use to better align their contracting structures with broader changes in the health care system. While pharmaceuticals represent a small share of total health care spending, it is one of the fastest-growing segments of the health care marketplace, and the increasing costs of pharmaceuticals necessitate more flexibility to contract in new ways based on the value of these products. Although not all products or services are appropriate for these types of contracts, VBCs could be a part of the solution to address increasing drug prices and overall drug spending.

VBCs encompass a variety of different contracting strategies for biopharmaceutical products that do not base payment rates on volume. These contracts instead may include payment on the achievement of specific goals in a predetermined patient population and offer innovative solutions for quantifying and rewarding positive outcomes or otherwise reducing payer risk associated with pharmaceutical costs.

To engage national stakeholders in a discussion of current practices, barriers, and potential benefits of VBCs, the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) convened a Partnership Forum on Advancing Value-Based Contracting in Arlington, Virginia, on June 20-21, 2017. The goals of the VBC forum were as follows: (a) agree to a definition of a VBC for facilitating discussion with key policy makers and regulators; (b) determine strategies for advancing the development and utilization of performance benchmarks; (c) identify best practices in evaluating, implementing, and monitoring VBCs; and (d) develop action plans to mitigate legal and regulatory barriers to VBCs.

More than 30 national and regional health care leaders representing health plans, integrated delivery systems, pharmacy benefit managers, employers, data and analytics companies, and biopharmaceutical companies participated. Speakers, panelists, and stakeholders attended the forum and explored the current environment for VBCs, identified challenges to the expansion of VBCs, offered potential solutions to those challenges, and developed an action plan for addressing selected challenges. The forum recommendations will be used by AMCP to establish a coalition of organizations to seek broader acceptance of VBCs in the marketplace and by policymakers. The recommendations will also help AMCP provide tools and resources to stakeholders in managing VBCs.

During the past decade, payment models for the delivery of health care have undergone a dramatic shift from focusing on volume to focusing on value. This shift began with the Affordable Care Act and was reinforced by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which increased the emphasis on payment for delivery of quality care. Today, value-based care is a primary strategy for improving patient care while managing costs.

This shift in payment models is expanding beyond the delivery of health care services to encompass models of compensation between payers and biopharmaceutical manufacturers. Value-based contracts (VBCs) have emerged as a mechanism that payers may use to better align their contracting structures with broader changes in the health care system. While pharmaceuticals represent a small share of total health care spending, it is one of the fastest-growing segments of the health care marketplace, and the increasing costs of pharmaceuticals necessitate more flexibility to contract in new ways based on the value of these products. Although not all products or services are appropriate for these types of contracts, VBCs could be a part of the solution to address increasing drug prices and overall drug spending.

VBCs encompass a variety of different contracting strategies for biopharmaceutical products that do not base payment rates on volume. These contracts instead may include payment on the achievement of specific goals in a predetermined patient population and offer innovative solutions for quantifying and rewarding positive outcomes or otherwise reducing payer risk associated with pharmaceutical costs.

To engage national stakeholders in a discussion of current practices, barriers, and potential benefits of VBCs the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) convened the Partnership Forum “Advancing Value-Based Contracting,” which was held June 20-21, 2017, in Arlington, Virginia. The goals of the VBC forum were as follows:

Agree to a definition of a VBC for facilitating discussion with key policy makers and regulators

Determine strategies for advancing the development and utilization of performance benchmarks

Identify best practices in evaluating, implementing, and monitoring VBCs

Develop action plans to mitigate legal and regulatory barriers to VBCs

More than 30 national and regional health care leaders participated, representing health plans, integrated delivery systems, pharmacy benefit managers, employers, data and analytics companies, and biopharmaceutical companies. Attendees explored the current environment for VBCs, identified challenges to the expansion of VBCs, offered potential solutions to those challenges, and developed an action plan for addressing selected challenges.

The Current Marketplace

Many VBCs have been implemented in the marketplace, but only a small number of these contracts have been reported publicly. Stakeholders are still experimenting with different types of VBCs to assess which are best suited for various patient segments in a specific drug class or disease state, and many remain challenged by operational and regulatory barriers.1-3

Forum participants stressed that there must be trust among health care providers, payers, and manufacturers. All stakeholders must be able to build trust that the data will be shared and interpreted in a collaborative and unbiased manner and that the data will not be used inappropriately.

Findings from a 2017 survey of AMCP members (N = 65) were presented at the forum. Results regarding implementation of VBCs by manufacturers and payers are shown in Table 1. These results indicate that payers and manufacturers have experienced some success with VBCs and have ongoing interest in the continuity of these contracts.

TABLE 1.

Integration of VBCs by Payers and Manufacturers

| Payers (%) | Manufacturers (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| All survey respondents (select 1 response) | N = 35 | N = 30 |

| Currently have a VBC in place | 20 | 33 |

| Interested in instituting a VBC in the future | 61 | 50 |

| Have a VBC pending | 11 | 13 |

| Don’t know/not interested | 9 | 3 |

| Survey respondents with at least 1 VBC (select all that apply) | N = 7 | N = 10 |

| Have 5 or more VBCs | 71 | 40 |

| Have renewed at least 1 VBC | 86 | 80 |

| Top 3 outcomes used in VBC | ||

| Measures of compliance | 100 | 60 |

| Improvement in clinical outcome | 71 | 70 |

| Avoidance of resource use | 71 | 60 |

VBC = value-based contract.

The most prevalent barriers to implementing VBCs cited by payers were a perceived lack of evidence that they reduced pharmaceutical spending, an inability to obtain outcomes data during the contract period, and uncertainty about budgets to manage contracts. For manufacturers, key barriers included challenges in obtaining accurate data and outcomes metrics, limits on their ability to discuss information outside of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved labeling, and other legal and regulatory barriers. Barriers that were considered high impact and high urgency for manufacturers included the need to create a safe harbor from the Anti-Kickback Statute and an exception to or clarification of Medicaid best price requirements. These barriers will be discussed in depth later in this proceedings document.

Regarding factors that are important for the success of VBCs, payers and manufacturers cited the need for simple, easily measurable outcomes as the most important factor, followed by risk sharing between the manufacturer and the payer. Other factors that were commonly cited included the need to have a sufficiently sized patient population, flexibility in the type of contract, and a reasonable time frame for the contract.

Defining Value-Based Contracting

There are currently several definitions of VBC being used in the marketplace. Forum participants reviewed a draft definition of VBC prepared by AMCP staff and definitions that have been published by other entities. This definition will help to support AMCP efforts to advocate for process improvements and regulations to optimize integration of VBCs in the marketplace. The consensus definition of VBC agreed upon by the participants is as follows: “A value-based contract is a written contractual agreement in which the payment terms for medication(s) or other health care technologies are tied to agreed-upon clinical circumstances, patient outcomes, or measures.” Participants also supported several guiding principles that shape the definition (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Defining Value-Based Contracting

| Definition | A value-based contract is a written contractual agreement in which the payment terms for medication(s) or other health care technologies are tied to agreed-upon clinical circumstances, patient outcomes, or measures |

| Guiding principles |

|

Rationale for VBC Definition Terminology

Participants engaged in substantive discussion regarding several components of the definition. Throughout this discussion, participants aimed to craft language that would be broad enough to capture an array of VBCs and be flexible and adaptable enough to allow for innovation as the contracting environment and health care marketplace evolve.

Regarding whether the term being defined should be an “outcomes-based contract” or a “value-based contract,” participants noted that while many contracts focus specifically on patient outcomes or clinical measures, there are other potential measures of value. Value could include both financial benefits and clinical benefits. Participants ultimately determined that the term “value” should be the focus of the definition so that the discussion of VBCs could encompass a wider range of contracts and noted that outcomes-based contracts are a component of VBCs. Participants ultimately determined that the overarching term “value-based contracting” should be used for contracts that may have a diverse set of outcome endpoints (such as those discussed in the section “Defining and Measuring Outcomes and Metrics”).

Participants considered the different terms for the potential entities that could enter into VBCs, including “payers,” “biopharmaceutical manufacturers,” “life sciences companies,” “providers,” and “risk-bearing entities.” (They intently considered whether patients are appropriate parties to a VBC; some suggested that this would be possible in the future but agreed that substantial evolution in the marketplace and stakeholder capabilities would be needed to make such arrangements possible.) The participants decided to omit defining the specific entities involved in a VBC to allow for inclusion of future or innovative contacting models.

The products addressed by the VBC (e.g., medications, devices, diagnostics, services) were also thoughtfully debated. Participants considered including terms such as “therapeutic or diagnostic product” and “health solution.” They notably wanted to ensure that the definition would encompass not only medications but also diagnostic products, potential interventions such as the implementation of mobile health (mHealth) technologies, and services that may be provided to the patient (e.g., adherence support). They selected the term “health care technologies” as a broad category to include these potential options.

The discussion also focused on outcomes or measures to use to describe the contracts and the terminology to address these outcomes. Participants reached agreement to use the phrase “clinical circumstances, patient outcomes, or measures” to encompass a wide range of potential metrics and allow for flexibility in contact design, including indication-specific pricing.

Finally, whether to use the language “financial term” or “payment” was a subject of debate. Participants sought to select language that would be broad enough to encompass various forms of compensation and the potential for the payment to be zero if the product did not perform as projected. The consensus that arose from this discussion was that “payment terms” was adequately broad to capture various types of compensation (or lack thereof).

Identifying Solutions to VBC Marketplace Challenges

Participants stressed that there must be trust among health care providers, payers, and manufacturers. All stakeholders must be able to build trust that the data will be shared and interpreted in a collaborative and unbiased manner.

Stakeholders face strategic and operational challenges related to VBCs. These challenges include decisions regarding several variables and functions, including the following:

Which health care technologies and/or services are appropriate for VBCs?

Which VBC types should be used for which types of health care technologies and/or services?

Which patient populations should be included in a VBC using which health care technologies and/or services?

How should VBC and provider incentives be aligned?

Which outcomes and metrics are best for different patient populations?

Is there capacity to collect and analyze data?

Can a reduction in the total cost of care be demonstrated?

Participants discussed these challenges, explored practical experiences, and brainstormed solutions to advance the use of VBCs.

The Benefits of Different Types of VBCs for Various Health Care Technologies and Patient Populations

Strategic fit, both clinical and operational for the entities involved, is important for the success and sustainability of VBCs. Successful VBCs must be carefully designed to provide benefits to all parties (including the manufacturer, payer, and patient). There are several variables that must be considered when determining what type of VBC structure will best align the VBC with market needs.

A number of factors can help determine whether a health care technology is appropriate for a VBC and which type of VBC aligns best with which market segment. These include how crowded or differentiated the marketplace is, the clinical uncertainty associated with a health care technology, and the patient population.

Participants were asked to consider different types of VBCs and explore a variety of factors that would affect different types of contracts. Their insights are provided in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Participant Recommendations for Aligning Contract Types that May Evolve into a VBC

| Contract Types that May Evolve into a VBC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Sharing | Coverage with Evidence Generation | Shared Accountability Model | Bundled Service | |

| Brief summary of contract requirements | Manufacturer charges less for the cost of therapy for patients or populations with suboptimal results or missed health outcomes | Manufacturer is financially liable or upside may be based on real-world evidence outcomes (e.g., from registries, active surveillance, claims) | Incorporates services that support a patient throughout their care transitions that aim to optimize their outcomes | Manufacturers offer additional patient services with the product |

| Key stakeholders | Payers, manufacturers, integrated delivery networks, future payers, employers, patients (potentially in the future) | Patients, advocacy groups, manufacturers, payers, health care providers | Manufacturers, providers, payers | Payers, manufacturers, specialty pharmacies |

| Key considerations | Level of complexity: Variable Appropriate for any therapeutic area Real-world evidence requirements

|

Level of complexity: High Appropriate for medications/devices/diagnostics that are approved with limited evidence (e.g., following an accelerated drug approval process)

Data generated may drive formulary placement and future management decisions Example treatment area: Duchenne muscular dystrophy or comparison of biologics vs. biosimilars |

Level of complexity: Undetermined May be based on diagnosis, research and goals, tools/services/solutions Nonbranded tools or services/solutions may be developed for the broader marketplace and incorporated into the contracts Payers advance the service to the provider, and the provider drives patient outcomes and monitors Adherence-based outcome as a measure Example: Mobile health apps |

Level of complexity: High Not viable in current marketplace due to legal and regulatory complexities (e.g., best price implications). Instead, services should be provided as a separate contract. “Suite of contracts” can achieve same aim Potentially narrows the eligible population Example treatment area: Diabetes |

A1c = hemoglobin A1c; EMR = electronic medical record; VBC = value-based contract.

In general, participants recommended that stakeholders begin experimenting with contracts that are less labor-intensive to identify data sourcing, collection and reporting challenges, legal issues, and sources of value to guide more widespread expansion. Some participants suggested having toolkits that are based on organizational goals and analytic/data capabilities that would be helpful as a starting point for discussions with other external stakeholders.

Defining and Measuring Outcomes and Metrics

One of the greatest challenges with a VBC is selecting appropriate outcomes to measure and determining how much value to assign to various outcomes. Measure selection can quickly become highly complex and variable based on the drug, patient population, and expected outcomes. But forum stakeholders consistently recommended that VBCs keep measurements simple. Outcomes should be easily measurable, clinically relevant, and associated with financial and/or clinical improvements. Examples of outcomes that could be measured in VBCs include the following:

Health care utilization rates (e.g., inpatient hospitalizations, observation stays, emergency department visits)

Hard clinical endpoints (e.g., myocardial infarctions, cardiovascular composite endpoints, deaths)

Cancer-free survival, progression-free survival

Cure rates

Adverse event rates

Laboratory values (e.g., hemoglobin A1c [A1c] for patients with diabetes)

Quality of life, activities of daily living (i.e., patient-reported outcomes)

Medication adherence

Medication persistence

Participants engaged in a robust discussion regarding whether adherence is an outcome measure for a VBC. The general consensus was that VBCs could include supports designed to improve adherence and, if possible, other outcome measures should be used for determining value. When beneficial outcomes take a year or more to determine, then adherence may be a preferable contract endpoint. Participants identified 2 options for addressing adherence in VBCs (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Options for Incorporating Adherence Supports in VBCs

| Options | ||

|---|---|---|

| Consider Whole Population with an Adherence Support Program | Base Contract on Patients Who Are Adherent | |

| Type of interventions | VBC includes adherence programs to support patients based on need Programs could provide patient incentives (e.g., movie tickets), address social determinants that affect health, and offer more comprehensive wraparound services, such as incorporation of behavioral and mental health services, transportation supports, housing assistance |

Include parameters in the contract for defining which patients are adherent and persistent, including thresholds for being included in the contract and strategies for measuring adherence/persistence |

| Advantages | Maximizes the population of patients who potentially benefit from the medication | Less costly to implement |

| Disadvantages | More costly to implement | Only reaches a subset of the potential population and limits the benefit that can be derived from the medication |

VBC = value-based contract.

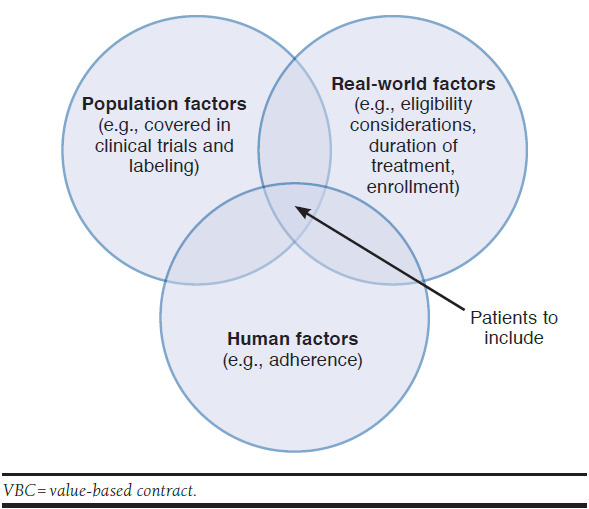

Participants also explored population-level endpoints compared with patient-level endpoints. Population-level endpoints, such as an average A1c for patients with diabetes, are more appropriate for large populations. Patient-specific endpoints (i.e., those that assess the outcomes for an individual patient and are reconciled on a patient-by-patient basis) are more appropriate for infrequently occurring events or small affected populations that still have meaningful spend, such as in rare diseases (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Factors to Consider when Selecting the Patient Population to Analyze for a VBC

Data Collection and Analysis

Following the selection of measures for a VBC, stakeholders must identify data that will be used for validating whether the outcome is achieved. Factors to consider include the sources of data, how it will be collected, and how it will be analyzed. Participants also noted that it will be important to define the patient populations that are included in the data analysis and ensure that the patient’s diagnosis and treatment are aligned with the data needed for the contract (Figure 1).

Participants identified several potential sources for the data, including results from laboratory tests, claims data, electronic health records, prior authorization systems, and patient-reported data from wearable mHealth devices.

Once the sources of data are defined, stakeholders must agree on a process for aggregating and analyzing the data in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Participants noted that developing the infrastructure necessary to perform these functions may require substantial resources, but this component of VBC implementation will become more efficient as the market matures.

Contract Duration and Timelines

Because most patients are enrolled with payers on an annual basis, there are important implications for stakeholders when developing contracts for outcomes that take longer to emerge. For example, prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes is an outcome that takes several years to demonstrate. On the other hand, there are some new medications, particularly those that are designated as orphan drugs, that can cost more than $100,000/patient but offer benefits to the patient that are long-lasting. Thus, while all the medication cost occurs in one year, the benefits extend for many years, and therefore timelines for VBCs may vary accordingly.

Participants offered several strategies for constructing VBCs that accommodate these realities. Surrogate and escalating endpoints could be used to align outcomes with the allotted time period. (Surrogate endpoints are short-term markers that are a valid proxy for a clinical endpoint; escalating endpoints build on each other over multiple time periods.)

Regarding single-use expensive products with long-term payoffs, participants stated that, given current models for third-party payers, it is likely that payers will be asked to pay the entire amount shortly after the therapy is administered. As more single-use expensive products become available, alternative payment models will need to be explored to address the societal affordability of these products.

Addressing Legal and Regulatory Barriers: Creating an Action Plan

FDA-specific federal rules and regulations need to be revised to enable payers and manufacturers to engage more broadly in VBCs. Specific federal requirements that represent some of the most important barriers include the Anti-Kickback Statute and the best price requirement of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. (The average manufacturer price [AMP] calculation may also be affected by VBCs.)

Addressing the Federal Anti-Kickback Statute

The Anti-Kickback Statute makes it a criminal offense to knowingly and willfully provide something of value with the intent to induce the purchase of items or services payable by a federal health care program. Because the statute is relatively broad and vague, Congress has created statutory exceptions and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has created numerous exemptions and regulatory safe harbors to prevent the application of the statute to various activities. Additional changes to the legal and regulatory infrastructure, including additional safe harbors, must be implemented to encourage broader adoption of VBCs.

To address this barrier, participants recommended that AMCP advocates for the creation of a new safe harbor or exception for VBCs, either through a proposal to OIG or through the development of new legislation. They recommended ensuring that a wide range of services be included in the safe harbor, including wraparound services provided to patients (e.g., adherence services, mHealth products provided to the patient, transportation for patient care visits, analytics, waived out-of-pocket costs) and to health care providers (e.g., a bundled service that would include compensation for a certified diabetes educator to deliver services at the provider’s practice site.)

As an alternative, participants suggested requesting clarification of existing federal rules for VBCs rather than seeking the development of new laws and regulations. They also recommended that AMCP develop a white paper to address these issues.

Addressing the Medicaid Best Price Rule

In order for their medicines to be covered by Medicaid, manufacturers are required to provide Medicaid programs with a rebate that is the greater of 23.1% of the AMP or AMP minus the best price.4 Additional statutory or negotiated rebates are often also negotiated. If a VBC includes a large discount or rebate for individuals who are considered treatment failures, the price paid for the treatment of an individual patient could set a new lowest best price, thereby increasing the rebate paid to all state Medicaid agencies. This requirement makes it challenging for manufacturers to write contracts in which they could potentially risk resetting their best price and increasing rebates paid for all Medicaid patients.

Participants noted a need for clarity in how manufacturers are interpreting the best price formula. One proposed accommodation would be asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to create an exception from the Medicaid best price rule for VBCs. It would be important to evaluate the consequences of such an exemption to understand the impact on Medicaid programs (and to avoid increasing costs to taxpayers).

Further discussion is recommended to explore potential solutions and devise an action plan, including development of a white paper.

Conclusions

Larger-scale implementation of VBCs may help justify pharmaceutical costs, ensuring the amount ultimately paid is linked to the value a product provides. For manufacturers, VBCs may assist with aligning contracting strategies with broader shifts occurring in the marketplace that emphasize compensation for value rather than volume. For payers, VBCs provide assurance that the financial cost is linked to tangible probability of a positive outcome. Although some VBCs have already been implemented, the evolution to value-based contracting is just beginning, and many barriers must be addressed to advance this contracting strategy. Participants in the AMCP forum supported several strategies and approaches for removing barriers. They offered a range of recommendations for developing infrastructures to support VBCs and strategies for designing contracts that would strategically align with the needs of the marketplace and utilize metrics that are available and represent meaningful outcomes.

Participants developed a consensus definition for VBC that is broad enough to encompass a variety of differing contract types and flexible enough to allow for future innovation. Having an agreed-upon definition will be integral for advocacy efforts that are designed to address legal and regulatory challenges. The federal Anti-Kickback Statute and Medicaid best price reporting requirements were identified as the primary barriers to the expansion of VBCs that require advocacy efforts. Participants strongly encouraged adapting these requirements to encourage broader adoption of VBCs. They concluded by offering robust support for advocacy efforts that will be designed to support the transformation of manufacturer contracting to improve the delivery of evidence-based health care. Guidance provided during the forum will be instrumental in crafting the tools and strategies necessary to help stakeholders make the shift to a value-based system.

These forum recommendations will be used by AMCP to establish a coalition of organizations to seek broader acceptance of VBCs in the marketplace and by policymakers. The recommendations will also help AMCP provide tools and resources to stakeholders in managing VBCs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The AMCP Partnership Forum “Advancing Value-Based Contracting” was moderated by Susan Winckler, BSPh, JD, President, Leavitt Consulting and Chief Risk Management Officer, Leavitt Partners. This proceedings document was prepared by Judy Crespi Lofton, MS, President, JCL Communications.

Forum Participants

JOSHUA S. BENNER, PharmD, ScD, President and CEO, RxAnte; MARTIN BICK, Executive Director, Strategic Pricing, Economics and Contracting, Bristol-Myers Squibb; JOEL V. BRILL, MD, FACP, Chief Medical Officer, Predictive Health; DIANA BRIXNER, RPh, PhD, Executive Director, Pharmacotherapy Outcomes Research Center, University of Utah College of Pharmacy; DOUGLAS BROWN, RPh, MBA, Vice President, Account Management, Pharmacy Pricing and Value Based Solutions, Magellan Rx Management; AMBROSE CARREJO, PharmD, Director, Pharmaceutical Contracting and Strategic Purchasing, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals; TIM CERNOHOUS, PharmD, PhD, Director of Ambulatory Pharmacy Services, Essentia Health; JOSEPH COPPOLA, Managing Director, Life Sciences Commercial Strategy & Operations Practice, Deloitte Consulting; VAN CROCKER, JR., President, Healthagen Outcomes, Division of Aetna; ROBERT DIRENZO, RPh, Managing Director, Specialty Solutions and Analytics, Evolent Health; MICHELLE DROZD, Deputy Vice President, Policy and Research, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America; AMY M. DUHIG, PhD, Vice President, Global Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Xcenda; PAUL EITING, Senior Manager, Value-Based Policy, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association; DAVID EVANS, Director, US Pricing and Value Based Contracting Strategy, Merck; JOHN FOX, MD, MHA, Associate Chief Medical Officer, PriorityHealth; MARY ELIZABETH GATELY, JD, Partner, DLA Piper; STEPHEN GEORGE, PharmD, MS, RPh, Senior Consultant, Milliman; PATRICK GLEASON, PharmD, FCCP, FAMCP, BCPS, Senior Director, Health Outcomes, Prime Therapeutics; JASON HARRIS, Manager, Public Policy, National Health Council; DOROTHY HOFFMAN, MPP, Director, Healthcare Transformation and Policy Partnerships, Eli Lilly; SCOTT HOWELL, DO, MPH, CPE, Medical Director, Heritage Provider Network; TOM HUBBARD, Vice President, Policy Research, Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEHI); MICHAEL H. JAMES, JD, CEO, Healthcare Consulting; JAMES KENNEY, RPh, MBA, Manager, Specialty and Pharmacy Contracts, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care; VINSON C. LEE, PharmD, MS, FCPhA, FAMCP, Director, Reimbursement, Access & Value, Amgen; GREG LOW, RPh, PhD, Director, MGPO, Pharmacy Quality and Utilization Program, Massachusetts General Hospital; STEPHEN NORTHRUP, MPA, Founding Partner, Rampy Northrup; ROBIN TURPIN, PhD, Value Evidence Lead, Takeda; HARRY VARGO, RPh, MBA, Head of Value Based Contracting, Pharmacy, Aetna; MIKE WASCOVICH, PharmD, MBA, RPh, Senior Director, Pharmacy Services, Premier; KIMBERLY WESTRICH, MA, Vice President, Health Services Research, National Pharmaceutical Council; KIMBERLY WILLIAMS, PharmD, BCPS, Program Director, Specialty Pharmacy, CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield; and ERIK ZBRANAK, MBA, Director, Portfolio Contracting and Innovation, Novo Nordisk.

AMCP Staff: REGINA BENJAMIN, JD, Director, Legislative Affairs; SUSAN CANTRELL, RPh, CAE, Chief Executive Officer; MARY JO CARDEN, RPh, JD, Vice President, Government & Pharmacy Affairs; JUDY CRESPI-LOFTON, MS, Writer, JCL Communications; CHARLIE DRAGOVICH, BSPharm, Vice President, Strategic Alliances and Corporate Services NEAL LEARNER, Media Relations and Editorial Director; NOREEN MATTHEWS, BSN, MBA, Program Management, American Medical Communications; MARK MILLIGAN, Vice President, Finance; TERRY RICHARDSON, PharmD, BCACP, Director, Product Development; SOUMI SAHA, PharmD, JD, Director, Pharmacy and Regulatory Affairs; PUNEET SINGH, PharmD, Education Program Manager; and TRICIA LEE WILKINS, PharmD, MS, PhD, Director, Pharmacy Affairs.

CORRESPONDENCE: Charlie Dragovich, BSPharm, Vice President, Strategic Alliances and Corporate Services, Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, 675 N. Washington St., Alexandria, VA 22314. Tel.: 703.684.2610; E-mail: cdragovich@amcp.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eli Lilly and Company, Anthem . Promoting value-based contracting arrangements. January 29, 2016. Available at: https://lillypad.lilly.com/WP/wp-content/uploads/LillyAnthemWP2.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 2.Deloitte . Journey to value-based care. Insights and implications from Deloitte’s 2015 health plans executive interviews. 2015. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-lshc-journey-to-value-based-care-final.pdf. Accessed } October 5, 2017.

- 3.Network for Excellence in Health Innovation . Rewarding results: moving forward on value-based contracting for biopharmaceuticals. March 2017. Available at: http://www.nehi.net/publications/76-rewarding-results-moving-forward-on-value-based-contracting-for-biopharmaceuticals/view. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. For state technical contacts . Value based purchase arrangements and impact on Medicaid. Release No. 176. July 14, 2016. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Prescription-Drugs/Downloads/Rx-Releases/State-Releases/state-rel-176.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.