Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Ezetimibe is recommended by clinical practice guidelines as a second-line therapy for lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, but little is known about its use and effectiveness in real-world populations.

OBJECTIVE:

To understand the real-world impact of adding or switching to ezetimibe on LDL-C goal achievement in patients with clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH).

METHODS:

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with an LDL-C measurement available between January 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, were identified using the Inovalon MORE2 database; this included commercial, health insurance exchange, Medicare Advantage, and managed Medicaid patients. The index date was the date of the first LDL-C measurement. Patients were required to have evidence of clinical ASCVD or probable HeFH based on ICD-9-CM codes and ≥ 1 outpatient pharmacy claim for a statin in the 1-year pre-index period, as well as continuous medical and pharmacy coverage for 1 year pre- and post-index. Patients who added ezetimibe to existing statin therapy or switched to ezetimibe within 90 days post-index LDL-C measurement were identified in order to replicate the typical time a clinician takes to assess the use of ezetimibe. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who met the LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL within the follow-up period. LDL-C goal achievement was evaluated by baseline LDL-C level groupings: < 70 mg/dL, 70-99 mg/dL, 100-129 mg/dL, or ≥ 130 mg/dL; and across 4 patient diagnosis categories: all patients, ASCVD only, probable HeFH only, and ASCVD and probable HeFH. Descriptive analyses were reported. Categorical variables were summarized as the number of and corresponding percentage of patients. Continuous variables were presented as the mean and SD of the number of observations and median and range where appropriate.

RESULTS:

Of 125,330 patients who met selection criteria, mean age was 70.1 (SD = 9.9) years and mean LDL-C baseline was 90.7 (SD = 34.0) mg/dL. Over one half of patients (70%) were receiving statin therapy. Within the post-index time frame, 1.05% (n = 1,309) of patients added or switched to ezetimibe. Of these, 26% achieved LDL-C goal during the 90-day follow-up (59.5% did not achieve goal and 14.4% did not have a follow-up lab value). Therapeutic targets were reached by 30% of patients with baseline LDL-C levels of 70-99 mg/dL; 14% of those with baseline LDL-C of 100-129 mg/dL; and 7% of those with baseline LDL-C of ≥ 130 mg/dL. Achievement of LDL-C goals also varied by baseline diagnosis category.

CONCLUSIONS:

The addition of or switch to ezetimibe therapy was associated with a relatively small percentage of LDL-C goal achievement (< 70 mg/dL) in patients with clinical ASCVD and/or HeFH, even among patients with baseline LDL-C between 70 and 99 mg/dL. To provide superior individualized care for patients with hyperlipidemia, there is a potential role for newer therapies in lipid lowering, such as PCSK9 inhibitors, in appropriate high-risk populations.

What is already known about this subject

Fewer than one third of patients receiving lipid-lowering medication for elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels are achieving LDL-C < 70 mg/dL.

While current guidelines recommend the addition of ezetimibe as a second-line therapy for LDL-C lowering, previous research suggests that ezetimibe may be insufficient to achieve treatment goals, even when added to maximally tolerated statin therapy.

What this study adds

Only 29% of patients met LDL-C goals at baseline.

With the addition of ezetimibe, LDL-C goals were met by an additional 7%-30% of patients; baseline LDL-C level predicted the likelihood of goal achievement.

In a real-world setting, adding ezetimibe therapy to statins, or switching to ezetimibe therapy, resulted in a small percentage of patients achieving LDL-C goals, indicating a potential need for more effective second-line therapies for patients who do not achieve LDL-C goals with statin use.

Approximately 34% of adults in the United States have elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C > 130 mg/dL) levels. However, less than one half of these individuals are receiving LDL-C-lowering treatment. Among patients receiving treatment, even fewer (29%) are achieving LDL-C goals.1 In a recent study, it was found that about 63% of high-risk patients on statin therapy alone do not achieve LDL-C targets.2 Patients with high cardiovascular risk or familial hypercholesterolemia may also be challenged to meet cholesterol goals; these patients often require additional pharmacotherapy to manage elevated LDL-C.3

The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines on the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend statin use for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in adults with elevated LDL-C levels.4 Four major groups are recommended to receive statin therapy: all patients with clinical ASCVD, independent of LDL-C levels; patients with primary LDL-C elevations > 190 mg/dL; patients with diabetes without clinical ASCVD, aged 40 to 75 years, who have LDL-C levels between 70 and 189 mg/dL; and patients without clinical ASCVD or diabetes with LDL-C 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk > 7.5%. The ACC/AHA guidelines further recommend the following target LDL-C reductions from untreated baseline levels after initiating statin therapy: a ≥ 50% reduction in LDL-C for high-intensity statin therapy or a 30%-50% reduction in LDL-C for moderate-intensity statin therapy.4 The more recently published ACC Expert Consensus Pathway recommends that patients also consider achieving an LDL-C < 70 mg/dL.5 Current guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) also recommend a specific LDL-C target of < 70 mg/dL.6

For patients unable to achieve anticipated reductions in LDL-C levels with statins alone, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend the addition of second-line therapy, currently ezetimibe.4 Ezetimibe is indicated for use in patients with nonfamilial hyperlipidemia, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH), or mixed hyperlipidemia and in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and phytosterolemia.7,8 In clinical trials, ezetimibe has been shown to reduce LDL-C levels by an additional 15%-24% when added to statin therapy, and it is commonly prescribed for patients who require LDL-C lowering beyond statins.8,9 Ezetimibe has also been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk when added to statin therapy in patients with elevated LDL-C.9 Unfortunately, many patients may not achieve treatment goals even when ezetimibe is added to maximally tolerated statin therapy.3,10-13

This retrospective analysis of administrative claims and clinical laboratory data was conducted to characterize the real-world use of ezetimibe in patients with clinical ASCVD and/or HeFH previously on statin therapy and to understand the impact of adding or switching to ezetimibe on LDL-C goal achievement.

Methods

Data Source

Data for this analysis were obtained from the Inovalon Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry (MORE2 Registry). This health care data warehouse contains information derived from more than 11.7 billion medical events generated by more than 137 million unique members nationwide. The registry represents a significant mix of commercial, health insurance exchange, Medicare Advantage, and managed Medicaid patients.14 Among the data collected for this database are patient demographics, enrollment information, diagnoses, procedures, outpatient prescription pharmacy claims, and laboratory results, including LDL-C levels. The data window for this study was from January 1, 2012, through June 30, 2015.

Patient Selection and Time Periods

The study cohort included patients aged ≥ 18 years who had at least 1 claim that included an available LDL-C value (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes [LOINC] codes 13457-7, 18262-6, 2089-1, or 55440-2) during the period of January 1, 2013, through June 30, 2014. Their first such claim was designated as their index claim and defined their index date. Patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy coverage (no more than a 30-day gap) for the 1-year pre-index and 1-year post-index periods and to have at least 1 outpatient pharmacy claim for statin drugs (either monotherapy or combination therapy), excluding statin-ezetimibe combination therapy, and diagnosis codes showing evidence of clinical ASCVD (per ACC/AHA criteria)4 and/or probable HeFH (per the National Lipid Association Algorithm)15 during the 1-year pre-index period.

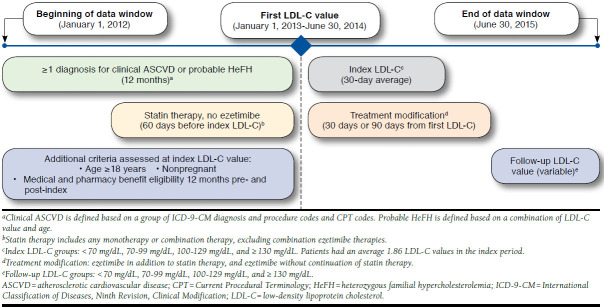

ASCVD diagnosis was defined using claims data including International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes and ICD-9-CM and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT-4) procedure codes (listed in Appendix A, available in online article). Probable HeFH was defined using a combination of patient age at index and their highest LDL-C level at index or in the pre-index period that met one of the following criteria: LDL-C ≥ 250 mg/dL for patients aged ≥ 30 years; LDL-C ≥ 220 mg/dL for patients aged 20-29 years; and LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL for patients aged < 20 years.15 Patients were excluded if they had any claims related to pregnancy within 5 years of the pre- and post-index periods. An overview of the analysis structure is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline Analysis for Describing LDL-C Levels Among Statin Users After Adding or Switching to Ezetimibe

The index period was the 30-day period following the index date. The baseline period was defined as the year before and including the index period. The follow-up period included the time from the index LDL-C value plus 90 days until the end of the available data.

Study Measures

In addition to baseline demographic and patient characteristics, this study included patient data on index LDL-C, which was the mean of all LDL-C levels within the 30-day index period, and the effect of treatment modification (i.e., the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy or the switch from statin to ezetimibe therapy) within the 90-day post-index period. Patients who added ezetimibe to statin therapy were required to have ≥ 1 claim for statin monotherapy and ≥ 1 claim for ezetimibe during the 90-day post-index period, with no claims for ezetimibe in the 60-day pre-index period. Patients who switched from statin therapy to ezetimibe had no claims for statin monotherapy and ≥ 1 claim for ezetimibe during the 90-day post-index period, with no claims for ezetimibe in the 60-day pre-index period.

The primary study outcome was the proportion of patients whose first LDL-C level in the follow-up period met the LDL-C treatment goal of < 70 mg/dL.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to present patient characteristics and outcomes. Categorical variables were summarized as the number of and corresponding percentages of patients. Continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the number of observations and, where appropriate, the median and range. Outcome measures were classified based on index LDL-C level (< 70 mg/dL, 70-99 mg/dL, 100-129 mg/dL, ≥ 130 mg/dL) and 4 patient groups (all patients, ASCVD only, probable HeFH only, ASCVD and probable HeFH). This report presents outcome measures data for all patients included in the study. Additional cohort data tables, which show outcomes for patients with specific conditions (clinical ASCVD only, probable HeFH only, or clinical ASCVD and probable HeFH), can be found in Appendix B (available in online article). All analyses were performed using R programming version 3.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

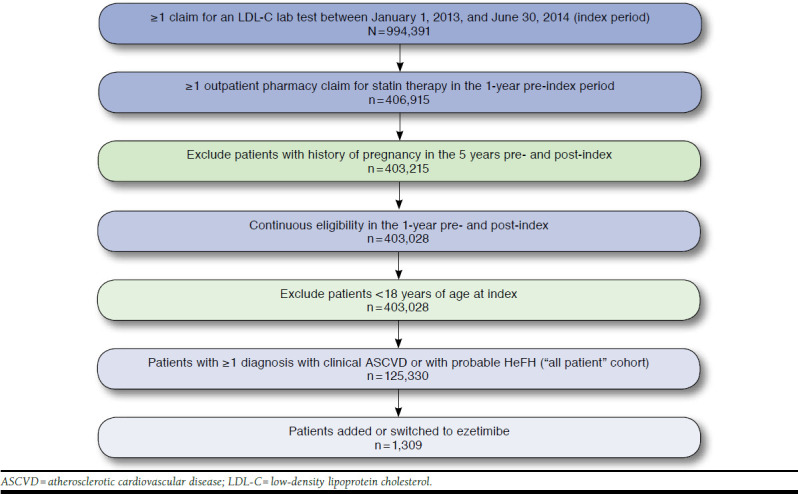

A total of 125,330 patients met the patient selection criteria for clinical ASCVD and/or probable HeFH and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis (i.e., those patients meeting clinical criteria and having claims for statin monotherapy or combination therapy [without ezetimibe]). Of these patients, 124,279 had clinical ASCVD only, 666 had probable HeFH only, and 385 had clinical ASCVD and probable HeFH (collectively, the “all patients” cohort). Patient selection is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Patient Selection

Baseline patient demographics are listed in Table 1. The mean patient age was 70.1 (SD = 9.9) years with 74% of patients aged ≥ 65 years or older. The patient population was 52% female and 52% Caucasian, and 83% of patients were enrolled in Medicare. Patients were primarily concentrated in the Northeast (42%) and South (40%; all in the United States).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Demographics for All Patients (N = 125,330), for Patients in the All Patients Cohort, and by Index LDL-C Level

| Index LDL-C | Alla | < 70 mg/dL | 70-99 mg/dL | 100-129 mg/dL | ≥ 130 mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 125,330 | 35,947 | 49,466 | 25,004 | 14,730 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 70.1 (9.9) | 70.79 (9.7) | 70.62 (9.7) | 69.54 (10.0) | 68.02 (10.9) |

| Female, % | 51.6 | 42.4 | 51.0 | 58.1 | 65.6 |

| Race or ethnicity, % | |||||

| Asian | 6.1 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 6.7 |

| Black | 21.9 | 19.7 | 21.4 | 23.2 | 26.3 |

| Caucasian | 52.1 | 57.6 | 54.4 | 47.3 | 41.0 |

| Hispanic | 14.5 | 10.1 | 13.5 | 18.5 | 20.6 |

| Other/unknown | 5.4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.4 |

| Geographic region, % | |||||

| Midwest | 10.5 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 7.4 |

| Northeast | 41.8 | 43.0 | 41.1 | 40.8 | 43.4 |

| South | 39.7 | 37.2 | 39.7 | 42.4 | 42.0 |

| West | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.3 |

| Payer type, % | |||||

| Commercial | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.3 |

| Medicaid | 5.8 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 10.2 |

| Medicare | 82.9 | 84.1 | 83.9 | 82.0 | 78.4 |

| Other | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Data source: Inovalon MORE2 Registry.

aThis category may include patients whose values are non-numerical and therefore not contained in the stratified LDL-C categories. Excluding patients whose values are non-numerical results in N = 125,147 (this population is also used in the therapy modification analysis).

LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SD = standard deviation.

Baseline clinical characteristics and patient treatment status during the 60-day pre-index period are shown in Table 2. The mean (SD) pre-index LDL-C for all patients was 90.7 (34.0) mg/dL. Within this cohort, 29% of patients had LDL-C < 70 mg/dL, 39% had LDL-C between 70 and 99 mg/dL, 20% had LDL-C between 100 and 129 mg/dL, and 12% had LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL. Patients with clinical ASCVD had a mean (SD) baseline LDL-C of 89.7 (31.4) mg/dL, patients with probable HeFH had a mean (SD) baseline LDL-C of 224.7 (61.7) mg/dL, and patients with both clinical ASCVD and probable HeFH had mean (SD) baseline LDL-C of 196.2 (86.9) mg/dL. The majority of patients had statin therapy claims in the 60-day pre-index period (70%); 35% received high-intensity and 35% received low-/medium-intensity statins.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics and Treatment in the 60-Day Pre-Index Period for Patients in the All Patients Cohort and by Index LDL-C Level

| Index LDL-C | Alla | < 70 mg/dL | 70-99 mg/dL | 100-129 mg/dL | ≥ 130 mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 125,330 | 35,947 | 49,466 | 25,004 | 14,730 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD) | 90.72 (34.0) | 58.87 (17.5) | 85.93 (13.8) | 111.13 (15.1) | 149.82 (35.4) |

| CCI, mean (SD) | 1.99 (1.9) | 2.19 (2.0) | 1.95 (1.9) | 1.86 (1.9) | 1.82 (1.8) |

| Diabetes, % | 59.0 | 66.7 | 57.8 | 54.0 | 52.3 |

| Clinical ASCVD, % | |||||

| ACS | 8.6 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 7.6 |

| History of MI | 26.9 | 31.6 | 27 | 23.2 | 21.1 |

| Angina | 15.9 | 16.4 | 15.8 | 15.5 | 15.1 |

| PAD | 53.0 | 53.5 | 53.3 | 53.0 | 50.5 |

| IS | 9.6 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.4 |

| IS/TIA | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| TIA | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 9.0 |

| Pre-index (60 days) statin intensity, % | |||||

| Low/medium | 35.0 | 31.6 | 38.3 | 39.1 | 25.8 |

| High | 35.5 | 45.3 | 36.5 | 27.5 | 22.2 |

| Combination | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Data source: Inovalon MORE2 Registry.

aThis category may include patients whose values are non-numerical and therefore not contained in the stratified LDL-C categories. Excluding patients whose values are non-numerical results in N = 125,147 (this population is also used in the therapy modification analysis).

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; IS = ischemic stroke; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI = myocardial infarction; PAD = peripheral artery disease; SD = standard deviation; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Ezetimibe therapy modification outcomes for all patients during the 90-day treatment modification follow-up time frame are shown in Table 3. Within the 90-day post-index time frame, 1.05% (n = 1,309) of patients added or were switched to ezetimibe. Fewer than 1% of all patients (n = 1,170; 0.93%) added ezetimibe to statin therapy during the 90-day post-index period, and even fewer (n = 139, 0.11%) switched to ezetimibe during that time frame. Overall, 26.1% of patients with either an ezetimibe addition or switch achieved the LDL-C goal (LDL-C < 70 mg/dL) during the 90-day treatment modification follow-up (59.5% did not achieve goal and 14.4% did not have a follow-up lab value). During this time frame, more patients who added ezetimibe to statin therapy achieved LDL-C goals compared with patients who switched from statin to ezetimibe therapy: 28% and 14%, respectively. Among patients who added ezetimibe to statin therapy and achieved LDL-C goal, the percentage who met the target varied by baseline LDL-C. For patients with baseline LDL-C levels of 70-99 mg/dL, 100-129 mg/dL, and ≥ 130 mg/dL, therapeutic targets were reached by 30%, 14%, and 7%, respectively, during the 90-day treatment modification follow-up period. In addition, the percentage of patients who met LDL-C goals by adding ezetimibe to statins varied by diagnosis group. LDL-C goals were achieved by 27% of patients with ASCVD only, 4% of patients with HeFH only, and 6% of patients with both ASCVD and HeFH (as would be expected given the higher LDL-C values in HeFH patients; data available in Appendix B).

TABLE 3.

Ezetimibe 90-Day Therapy Modification Outcomes for Patients in the All Patients Cohort and by Index LDL-C Level

| Index LDL-C | All | < 70 mg/dL | 70-99 mg/dL | 100-129 mg/dL | ≥ 130 mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 125,147 | 35,947 | 49,466 | 25,004 | 14,730 |

| Addition of ezetimibe to statins, n (%) | 1,170 (0.9) | 264 (0.7) | 315 (0.6) | 286 (1.1) | 305 (2.1) |

| Achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 27.5 | 62.1 | 29.5 | 15.0 | 7.2 |

| Did not achieve LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 58.3 | 25.8 | 55.6 | 71.3 | 77.0 |

| No follow-up lab value (%) | 14.2 | 12.1 | 14.9 | 13.6 | 15.7 |

| Switch to ezetimibe within 90 days post-index, n (%) | 139 (0.1) | 14 (0.0) | 27 (0.1) | 32 (0.1) | 66 (0.4) |

| Achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 14.4 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 6.3 | 4.5 |

| Did not achieve LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 35.7 | 51.9 | 87.5 | 75.8 | 69.8 |

| No follow-up lab value (%) | 15.8 | 21.4 | 14.8 | 6.3 | 19.7 |

| Addition of or switch to ezetimibe within 90 days post-index, n (%) | 1,309 (1.0) | 278 (0.8) | 342 (0.7) | 318 (1.3) | 371 (2.5) |

| Achieved LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 14.4 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 6.3 | 4.5 |

| Did not achieve LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (%) | 69.8 | 35.7 | 51.9 | 87.5 | 75.8 |

| No follow-up lab value (%) | 14.4 | 12.6 | 14.9 | 12.9 | 16.4 |

Data source: Inovalon MORE2 Registry.

LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Among patients who switched from ezetimibe to statin therapy, the percentage of patients meeting LDL-C targets varied by baseline LDL-C. For patients with LDL-C levels of 70-99 mg/dL, 100-129 mg/dL, and ≥ 130 mg/dL, therapeutic targets were reached by 33%, 6%, and 4%, respectively, during the 90-day treatment modification follow-up period. Switching from statin to ezetimibe therapy resulted in 15% of patients in the ASCVD only cohort achieving LDL-C goals; no patients in the HeFH only or ASCVD and HeFH cohorts achieved the LDL-C goal (data available in Appendix B).

Discussion

In this study of patients with clinical ASCVD and/or HeFH who received statin therapy to lower LDL-C levels, the addition of or switch to ezetimibe therapy was associated with a small percentage of LDL-C goal achievement (< 70 mg/dL), even in patients with lower baseline LDL-C. While the highest levels of goal achievement were seen in patients with lower baseline LDL-C values (between 70 and 99 mg/dL), only 30% of these patients met the LDL-C goal. Furthermore, the level of goal achievement decreased as baseline LDL-C increased, with goal achievement seen in only 15% and 7% of patients with baseline LDL-C of 100-129 mg/dL and ≥ 130 mg/dL, respectively. This reflects the modest LDL-C reduction that ezetimibe provides. In patients with higher LDL-C values, such as in HeFH, it is unlikely that treatment goals can be achieved with the addition of or switch to ezetimibe.

Based on these observed therapeutic gaps, there is a clear need for more effective therapies to lower LDL-C and maximize cardiovascular benefits for high-risk patients, such as those with clinical ASCVD or probable HeFH, who do not meet LDL-C goals with statin treatment alone. In clinical trials, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors have been shown to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%-60% or more.6 Given this high efficacy, PCSK9 inhibitors may fill the LDL-C-lowering gap for patients who do not respond to statins and/or ezetimibe.3,16 Professional societies such as the ACC have already supported PCSK9 inhibitors for LDL-C lowering in high-risk patients. In a recent report from the ACC, an expert committee recommended that a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered as a second-line therapy for patients with ASCVD and extremely high baseline LDL-C (≥ 190 mg/dL) who have experienced a < 50% LDL-C reduction with statins.5

Clinicians should determine which patients will receive the highest benefit from available therapeutic options and individualize the choice of statins and secondary treatments based on patient characteristics.17 Based on the current study results, patients with lower baseline LDL-C (between 70 and 99 mg/dL) are more likely to experience LDL-C goal achievement with ezetimibe compared with those with higher baseline LDL-C (100-129 mg/dL or ≥ 130 mg/dL).

Limitations

Study limitations include the potential for miscoding in medical claims databases and the lack of a formal chart review of these data to confirm diagnosis and clinical outcomes. This limitation may have been partially mitigated, however, by the geographic and payer diversity of the claims database used because miscoding errors are likely to be equally distributed. It should be noted, however, that laboratory results are only available for approximately 20%-30% of patients in the MORE2 Registry database. Additionally, this study applied an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL to measure the effectiveness of ezetimibe rather than a percentage reduction in LDL-C.4 However, this LDL-C goal is still recognized in the ESC/EAS guidelines6 and the recent ACC Expert Consensus Pathway,5 and many physicians still follow this recommendation. This goal may be especially difficult to reach for HeFH patients. Lastly, this study did not evaluate adherence. While data were available for prescription-filling, no data were available on how regularly medication was taken; as such, the effect of potential nonadherence on patient nonresponse to treatment is unknown. We also found that a large proportion of patients were prescribed low-/medium-intensity statins, and it is not clear why these patients are not maximizing statin therapy. The study found a small proportion of patients who switched to or added ezetimibe (~1%). However, we know that in real-world patients, the percentage of subjects on ezetimibe is relatively low. It was only approximately 5% in the FOURIER cardiovascular outcomes trial of evolocumab in patients with ASCVD.17

Conclusions

This retrospective analysis of administrative claims and clinical laboratory data showed that patients with LDL-C higher than 100 mg/dL are unlikely to achieve goals of < 70 mg/dL with ezetimibe; this was particularly evident in patients with baseline LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL. While ezetimibe may be appropriate for some patients not achieving LDL-C goal on statin therapy, routine use of ezetimibe before advancing to more efficacious lipid-lowering therapy would still leave many patients with elevated LDL-C levels. To provide superior individualized care for patients with hyperlipidemia, there is a role for newer therapies in lipid lowering, such as PCSK9 inhibitors, in appropriate high-risk populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Aimee Spevak and Caitlin Rothermel (MedLitera, on behalf of Amgen) and Tim Peoples (Amgen) provided medical writing assistance.

APPENDIX A. Procedure and Diagnosis Codes Used to Define the Study Population

| Code Type | Codes | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 411.1x, 411.8x | Acute coronary syndrome |

| CPT | 33140, 33141, 33508, 33510, 33511, 33512, 33513, 33514, 33516, 33517, 33518, 33519, 33521, 33522, 33523, 33530, 33533, 33534, 33535, 33536, 33572, 35500, 35572, 35600, 00566, 00567, 92920, 92921, 92924, 92925, 92928, 92929, 92933, 92934, 92937, 92938, 92941, 92943, 92944, 92973, 92975, 92977, 92980, 92981, 92982, 92984, 92995, 92996 | History of coronary revascularization |

| HCPCS | C9600, C9601, C9602, C9603, C9604, C9605, C9606, C9607, C9608, G0290, G0291, S2205, S2206, S2207, S2208, S2209, S2220 | History of coronary revascularization |

| ICD-9-CM Px | 00.45, 00.46 | History of coronary revascularization |

| ICD-9-CM Px | 00.47, 00.48, 00.66, 17.55, 36.06, 36.07, 36.01, 36.02, 36.03, 36.04, 36.05, 36.09, 36.10, 36.11, 36.12, 36.13, 36.14, 36.15, 36.16, 36.17, 36.19, 36.20, 36.31, 36.32, 36.33, 36.34, 36.39 | History of coronary revascularization |

| MS-DRG | 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251 | History of coronary revascularization |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 410.xx, 411.0x, 412.xx | History of myocardial infarction |

| MS-DRG | 280, 281, 282, 283, 284, 285 | History of myocardial infarction |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 413.xx | Stable or unstable angina |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 250.70, 250.71, 250.72, 250.73, 362.30, 362.31, 362.32, 362.33, 433.00, 433.10, 433.20, 433.30, 433.80, 433.90, 434.00, 434.10, 434.90, 440.0x, 440.1x, 440.2x, 440.3x, 440.4x, 440.8x, 440.9x, 443.9x, 444.xx, 445.xx | Peripheral artery disease |

| CPT | 34051, 34101, 34111, 34201, 34203, 34812, 34820, 34833, 34834, 34900, 35011, 35013, 35021, 35022, 35045, 35131, 35132, 35141, 35142, 35151, 35152, 35302, 35303, 35304, 35305, 35306, 35311, 35321, 35351, 35355, 35361, 35363, 35371, 35372, 35381, 35450, 35452, 35454, 35456, 35458, 35459, 35470, 35471, 35472, 35473, 35474, 35475, 35480, 35481, 35482, 35483, 35484, 35485, 35490, 35491, 35492, 35493, 35494, 35495, 35511, 35512, 35516, 35518, 35521, 35522, 35523, 35525, 35526, 35531, 35533, 35535, 35536, 35537, 35538, 35539, 35540, 35541, 35546, 35548, 35549, 35551, 35556, 35558, 35560, 35563, 35565, 35566, 35570, 35571, 35582, 35583, 35585, 35587, 35612, 35616, 35621, 35623, 35626, 35631, 35632, 35633, 35634, 35636, 35637, 35638, 35641, 35645, 35646, 35647, 35650, 35651, 35654, 35656, 35661, 35663, 35665, 35666, 35671, 35875, 35876, 35879, 35881, 35883, 35884, 35903, 37184, 37185, 37186, 37201, 37202, 37205, 37206, 37207, 37208, 37209, 75960, 75962, 75964, 93668 | Peripheral artery revascularization |

| ICD-9-CM Px | 00.55, 38.10, 38.13, 38.14, 38.18, 39.50, 39.51, 39.52, 39.71, 39.73, 39.90 | Peripheral artery revascularization |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 433.x1, 434.x1 | Ischemic stroke |

| HCPCS | G8600, G8601, G8602 | Ischemic stroke |

| MS-DRG | 061, 062, 063 | Ischemic stroke |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | V12.54 | Stroke/transient ischemic attack |

| HCPCS | G8837 | Stroke/transient ischemic attack |

| ICD-9-CM Dx | 362.34, 435.0x, 435.1x, 435.2x, 435.3x, 435.8x, 435.9x | Transient ischemic attack |

| MS-DRG | 069 | Transient ischemic attack |

CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; Dx = diagnosis; HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; MS-DRG = Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group; Px = procedure.

APPENDIX B. Baseline Patient Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Treatment Before Index LDL-C Measurement by Index LDL-C Level

| Index LDL-C (mg/dL) | Clinical ASCVD Only | HeFH Only | Clinical ASCVD and HeFH | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alla | <70 | 70-99 | 100-129 | ≥ 130 | Alla | < 70 | 70-99 | 100-129 | ≥ 130 | Alla | < 70 | 70-99 | 100-129 | ≥ 130 | |

| Number of patients | 124,279 | 35,871 | 49,389 | 24,889 | 13,952 | 666 | 20 | 33 | 74 | 534 | 385 | 56 | 44 | 41 | 244 |

| Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 70.21 (9.86) | 70.81 (9.65) | 70.62 (9.66) | 69.56 (9.99) | 68.40 (10.56) | 60.00 (13.8) | 61.30 (11.1) | 63.12 (9.9) | 62.89 (13.2) | 59.38 (14.1) | 65.49 (10.59) | 64.23 (9.43) | 65.82 (9.77) | 68.27 (9.04) | 65.25 (11.18) |

| Female, % | 51.5 | 42.4 | 51.0 | 58.1 | 65.1 | 72.2 | 55.0 | 69.7 | 63.5 | 74.3 | 67.0 | 48.2 | 68.1 | 51.2 | 73.7 |

| Diabetes, % | 59.0 | 66.7 | 57.7 | 54.0 | 52.9 | 36.6 | 75.7 | 54.5 | 40.5 | 33.3 | 65.5 | 94.6 | 79.5 | 65.9 | 56.1 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD) | 89.68 (31.41) | 58.77 (17.10) | 85.84 (13.51) | 110.93 (14.69) | 144.76 (25.19) | 224.73 (61.71) | 144.45 (62.41) | 150.33 (39.99) | 155.92 (34.42) | 241.76 (53.03) | 196.23 (86.94) | 94.95 (58.93) | 138.87 (39.12) | 148.73 (42.15) | 237.81 (74.29) |

| CCI, mean (SD) | 1.99 (1.89) | 2.19 (1.96) | 1.95 (1.87) | 1.86 (1.85) | 1.85 (1.83) | 0.94 (1.46) | 1.60 (1.88) | 1.24 (1.37) | 1.28 (1.79) | 0.86 (1.39) | 2.19 (1.97) | 2.70 (2.19) | 1.98 (1.73) | 2.44 (2.50) | 2.08 (1.84) |

| Race or ethnicity, % | |||||||||||||||

| Asian | 6.1 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 14.8 | 8.0 | 5.8 | 0 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 5.7 |

| Black | 21.9 | 19.7 | 21.5 | 23.2 | 26.4 | 21.6 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 18.5 | 23.3 | 22.5 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 36.4 | 27.8 |

| Caucasian | 52.1 | 57.5 | 54.3 | 47.3 | 41.0 | 43.2 | 78.5 | 54.2 | 50.0 | 40.1 | 55.3 | 85.5 | 79.3 | 39.4 | 43.7 |

| Hispanic | 14.5 | 10.1 | 13.5 | 18.5 | 20.9 | 12.6 | 7.1 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 13.9 | 12.4 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 9.1 | 17.1 |

| Other | 5.4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 14.3 | 8.3 | 11.1 | 14.7 | 4.0 | 0 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 5.7 |

| Geographic region, % | |||||||||||||||

| Midwest | 10.5 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 9.8 | 6.6 |

| Northeast | 41.8 | 43.1 | 41.1 | 40.7 | 43.5 | 41.1 | 20.0 | 48.5 | 44.6 | 40.8 | 35.1 | 8.9 | 20.4 | 51.2 | 41.0 |

| South | 39.7 | 37.1 | 39.6 | 42.4 | 42.0 | 40.4 | 60.0 | 33.3 | 43.2 | 39.9 | 52.5 | 89.3 | 65.9 | 39.0 | 43.9 |

| West | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 15.2 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 9.1 | 0 | 8.6 |

| Payer type, % | |||||||||||||||

| Commercial | 11.1 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 31.7 | 10.0 | 18.2 | 27.0 | 33.9 | 9.9 | 1.8 | 9.1 | 2.4 | 13.1 |

| Medicaid | 5.8 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 21.2 | 8.1 | 15.4 | 9.3 | 0 | 2.27 | 4.9 | 13.5 |

| Medicare | 83.0 | 84.0 | 83.9 | 82.0 | 79.6 | 53.5 | 80.0 | 60.6 | 64.9 | 50.6 | 80.8 | 98.2 | 88.6 | 92.7 | 73.4 |

| Other | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical ASCVD, % | |||||||||||||||

| ACS | 8.6 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 9.1 | 12.2 | 6.1 |

| History of MI | 27.0 | 31.5 | 27.0 | 23.3 | 21.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41.0 | 82.1 | 52.3 | 46.3 | 28.7 |

| Angina | 15.9 | 16.5 | 15.8 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.8 | 3.6 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 18.9 |

| PAD | 53.3 | 53.6 | 53.4 | 53.2 | 52.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.2 | 32.1 | 45.5 | 36.6 | 49.6 |

| IS | 9.6 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.9 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 19.5 | 11.1 |

| IS/TIA | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 11.4 | 14.6 | 12.7 |

| TIA | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.9 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 12.2 | 10.7 |

| Pre-index (60 days) statin intensity, % | |||||||||||||||

| Low/medium | 35.1 | 31.6 | 38.2 | 39.2 | 26.5 | 25.8 | 35.0 | 27.2 | 21.6 | 26.0 | 20.5 | 48.2 | 18.2 | 24.4 | 13.9 |

| High | 35.6 | 45.3 | 36.5 | 27.4 | 22.0 | 51.2 | 55.0 | 63.6 | 56.8 | 49.4 | 38.2 | 41.1 | 59.1 | 53.7 | 31.1 |

| Combination | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Outcomes | |||||||||||||||

| Add ezetimibe to statins | 1,132 (3.2) | 263 (0.7) | 313 (0.9) | 285 (0.8) | 271 (0.8) | 21 (3.2) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (3.7) | 17 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (2.4) | 14 (5.7) |

| Achieved < 70 mg/dL | 28.3 | 62.4 | 29.4 | 15.1 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Did not achieve < 70 mg/dL | 57.5 | 25.5 | 55.6 | 71.2 | 76.4 | 81.0 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | 80.0 | 82.4 | 0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 85.7 |

| Switch to ezetimibe | 132 (0.4) | 14 (0.0) | 27 (0.1) | 32 (0.1) | 59 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.6) |

| Achieved < 70 mg/dL | 15.2 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Did not achieve < 70 mg/dL | 71.2 | 35.7 | 51.9 | 87.5 | 79.7 | 66.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 66.7 | 25.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25.0 |

Data source: Inovalon MORE2 Registry.

aThis category may include patients whose values are non-numerical and therefore not contained in the stratified LDL-C categories.

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; HeFH = heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; IS = ischemic stroke; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI = myocardial infarction; PAD = peripheral artery disease; SD = standard deviation; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karalis DG, Victor B, Ahedor L, Liu L.. Use of lipid-lowering medications and the likelihood of achieving optimal LDL-cholesterol goals in coronary artery disease patients. Cholesterol. 2012;2012:861924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman MJ, Stock JK, Ginsberg HN; PCSK9 Forum. PCSK9 inhibitors and cardiovascular disease: heralding a new therapeutic era. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015;26(6):511-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, et al. 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non-statin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(1):92-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:281-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25): 2387-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1489-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussbaumer B, Glechner A, Kaminski-Hartenthaler A, Mahlknecht P, Gartlehner G.. Ezetimibe-statin combination therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(26):445-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruckert E, Giral P, Tellier P.. Perspectives in cholesterol-lowering therapy: the role of ezetimibe, a new selective inhibitor of intestinal cholesterol absorption. Circulation. 2003;107(25):3124-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, et al. Achievement of dual low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein targets more frequent with the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin and associated with better outcomes in IMPROVE-IT. Circulation. 2015;132(13):1224-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avellone G, Di Garbo V, Guarnotta V, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term ezetimibe/simvastatin treatment in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Int Angiol. 2010;29(6):514-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermaak W, Pinto X, Ponsonnet D, et al. Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: coadministration of ezetimibe plus atorvastatin. Atheroscler Suppl. 2002;3(2):230-31 [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inovalon. MORE2 Registry Database: how we help. Available at: http://www.inovalon.com/howwehelp/more2-registry. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- 15.Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ. Familial hypercholesterolemias: prevalence, genetics, diagnosis and screening recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3 Suppl):S9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergeron N, Phan BA, Ding Y, Fong A, Krauss RM. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibition: a new therapeutic mechanism for reducing cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2015;132(17):1648-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]