Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Administrative claims contain detailed medication, diagnosis, and procedure data, but the lack of clinical outcomes for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) historically has limited their use in comparative effectiveness research. A claims-based algorithm was developed and validated to estimate effectiveness for RA from data for adherence, dosing, and treatment modifications.

OBJECTIVE:

To implement the claims-based algorithm in a U.S. managed care database to estimate biologic cost per effectively treated patient.

METHODS:

The cohort included patients with RA aged 18-63 years in the Optum Research Database who initiated biologic treatment between January 2007 and December 2010 and were continuously enrolled 6 months before through 12 months after the first claim for the biologic (the index date). Patients were categorized as effectively treated by the claims-based algorithm if they met all of the following 6 criteria in the 12-month post-index period: (1) a medication possession ratio ≥ 80% for subcutaneous biologics, or at least as many infusions as specified in U.S. labeling for intravenous biologics; (2) no increase in biologic dose; (3) no switch in biologics; (4) no new nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; (5) no new or increased oral glucocorticoid treatment; and (6) no more than 1 glucocorticoid injection. Drug costs (all biologics) and administration costs (intravenous biologics) were obtained from allowed amounts on claims. Biologic cost per effectively treated patient was defined as total 1-year biologic cost divided by the number of patients categorized by the algorithm as effectively treated with that index biologic. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the total health care costs per effectively treated patient during the first year of biologic therapy.

RESULTS:

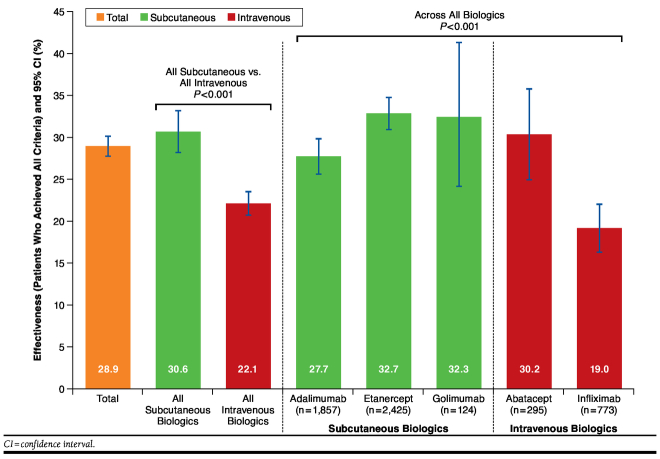

A total of 5,474 individuals were included in the analysis. The index biologic was categorized as effective by the algorithm for 28.9% of patients overall, including 30.6% for subcutaneous biologics and 22.1% for intravenous biologics. The index biologic was categorized as effective in the first year for 32.7% of etanercept (794/2,425), 32.3% of golimumab (40/124), 30.2% of abatacept (89/295), 27.7% of adalimumab (514/1,857), and 19.0% of infliximab (147/773) patients. Mean 1-year biologic cost per effectively treated patient, as defined in the algorithm, was lowest for etanercept ($43,935), followed by golimumab ($49,589), adalimumab ($52,752), abatacept ($62,300), and infliximab ($101,402). The rank order in the sensitivity analysis was the same, except for golimumab and etanercept.

CONCLUSIONS:

Using a claims-based algorithm in a large commercial claims database, etanercept was the most effective and had the lowest biologic cost per effectively treated patient with RA.

What is already known about this subject

Several biologics are approved for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but few randomized, head-to-head studies have compared the efficacy of 2 or 3 biologics in a given population.

Administrative claims contain detailed medication, diagnosis, procedure, and cost data for actual use of biologics in the commercially insured population, which is typically more heterogeneous than patients included in clinical trials, but the lack of information on clinical outcomes for RA has limited the use of administrative claims in comparative effectiveness research.

A claims-based algorithm that uses adherence, dosing, and treatment modifications to estimate biologic effectiveness (low disease activity or remission) for RA was validated in a Veteran’s Administration population and was further evaluated in a comparative effectiveness study that was linked to a commercial claims database.

What this study adds

This study used the validated algorithm to estimate the cost of effective biologic treatment from adjudicated claims in 5,474 patients with RA who received an approved biologic between 2007 and 2010.

Using the claims-based algorithm, mean 1-year biologic cost per effectively treated patient was lowest for etanercept ($43,935), followed by golimumab ($49,589), adalimumab ($52,752), abatacept ($62,300), and infliximab ($101,402).

These results support use of the validated claims-based effectiveness algorithm to estimate mean biologic cost per effectively treated patient for RA from claims data.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic condition characterized by inflammation of the joints, affects approximately 1.3 million adults in the United States.1 RA may lead to joint damage, chronic pain and stiffness, loss of function, and disability. The estimated burden of RA includes annual health care costs of $8.4 billion and total annual societal costs of $19.3 billion.2 Although there is no cure for RA, a number of effective treatment options are available. Treatment for RA usually is initiated with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as leflunomide or methotrexate.3,4 The 2012 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines recommend biologic therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics or the non-TNF biologics abatacept or rituximab for patients who have an inadequate response to methotrexate monotherapy or DMARD combination therapy or for early RA patients with moderate or high disease activity and features of poor prognosis.4 First-line biologic therapies—including abatacept,5 adalimumab,6 certolizumab pegol,7 etanercept,8 golimumab (in combination with methotrexate),9 infliximab (in combination with methotrexate),10 and tocilizumab11—have been shown to be effective in slowing the progression of structural damage and improving physical function in patients with moderately to severely active RA. Lack of response or loss of benefit warrants switching to a different biologic therapy, although little guidance exists as to which therapy is preferable to use as a second or subsequent agent.4

There is increasing interest in comparative effectiveness research (CER), particularly for head-to-head randomized clinical trials. However, there have been relatively few head-to-head prospective trials of biologics in RA,12-18 and most have not found one biologic to have superior efficacy over another. The recently published ADACTA study reported that tocilizumab treatment was associated with significantly greater reduction of the signs and symptoms of RA than adalimumab treatment, but each biologic was administered only as monotherapy.18 Moreover, results from clinical trials may have only limited applicability to clinical practice because patients with RA in clinical trials rarely mirror patients in the real world.19,20 In general, subjects in clinical trials have fewer comorbidities or concomitant treatments than patients in clinical practice, are more likely to be adherent and compliant to prescribed treatments, have more frequent follow-up visits and are more likely to attend those visits, and they receive different treatment.21 Detailed scales that are used to assess RA outcomes in clinical trials, such as Disease Activity Score 28 Joint (DAS-28) and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), are not widely used in clinical practice.22 Given the number of biologic therapies available with differing modes of administration, more CER in RA is needed to better inform decisions of clinicians and managed care professionals.

Although randomized controlled trials typically are the gold standard in CER, observational studies using large claims databases are attractive because they are relatively inexpensive to conduct, widely available, and offer a large volume of data on the actual treatment of patients in clinical practice. For example, health insurance claims routinely contain information on medication use, outpatient encounters, hospital discharges, and costs, and they are commonly used to evaluate safety and resource utilization. However, they do not typically include clinical outcome measures that can aid in quantifying effectiveness of RA medications.

A claims-based algorithm to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of biologics for RA was developed and validated against DAS-28 data from the national Veteran’s Administration Rheumatoid Arthritis (VARA) registry.23 The gold standard for effectiveness was measured at the visit closest to 1 year following the index visit in the VARA database and was defined as low disease activity (a DAS-28 score of ≤ 3.2) or improvement in DAS-28 score by > 1.2 units, with high adherence to therapy.23 The validation study did not consider patients with RA remission (a DAS-28 score of < 2.6) separately but included them within the group that had low disease activity. A subsequent analysis evaluated the algorithm by comparing commercial claims data with clinician review of outpatient medical records.24 This algorithm provides a validated method for CER using real-world data within this class of drugs.

The objectives of the analysis presented here were to apply the claims-based effectiveness algorithm to a dataset derived from a large health plan in the United States to estimate the effectiveness of commonly used biologics approved for first-line treatment of moderate-to-severe RA and to estimate biologic costs per effectively treated patient.

Methods

Data Source

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Optum Research Database, which contains medical and pharmacy claims with linked enrollment information from 1993. There were 24 million patients enrolled in a commercial health plan with a medical and pharmacy benefit for at least 1 day between 2007 and 2010. Underlying information in the database is geographically diverse across the United States and representative of the commercially insured population.

Study Sample

To be included in this analysis, patients were required to have a physician diagnosis of RA and receive a biologic that was approved for first-line treatment of moderate-to-severe RA (abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, or infliximab). Patients had at least 1 claim between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2010, for 1 of these biologics. Rituximab and tocilizumab were not included because they were not approved for first-line treatment of RA at the time of the analysis. Certolizumab pegol was excluded because of its small sample size (n = 53; < 1% of sample). The date of a patient’s first observed claim for a biologic of interest was considered the patient’s index date. Patients were required to have continuous enrollment in their plans with medical and pharmacy benefits for the 6 months preceding their index dates (the pre-index period) and the 12 months following their index dates (the post-index period). Patients needed to be aged 18 to 63 years (inclusive) as of their index dates to ensure that they had at least 1 full year of subsequent coverage in the commercial insurance plan before they were eligible for Medicare. A physician diagnosis of RA was confirmed by an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 714.0x during the pre-index period up to 30 days after the index date.

Patients were excluded from the study sample if they had a claim for 2 or more biologics on their index date. Patients with a medical claim with a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System Level II J-Code for a self-administered subcutaneously injected (SC) biologic were excluded because the days’ supply could not be determined and thus 1 of the algorithm criteria (high treatment adherence; see “Effectiveness” section) could not be evaluated for those claims. Patients with a pharmacy claim with a National Drug Code number for an intravenously infused (IV) biologic were excluded because the infusion date could not be determined. To identify new initiations of first-line biologic treatment, patients could not have a claim in the 6-month pre-index period for any biologic agent indicated for RA (abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, and tocilizumab). Patients were also excluded if at any time during the 6-month pre-index period through day 30 post-index, they had a diagnosis of another approved indication for biologics that are used for RA: plaque psoriasis (ICD-9-CM 696.1x), psoriatic arthritis (696.0x), ankylosing spondylitis (720.0x), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (714.3x), Crohn’s disease (555.xx), ulcerative colitis (556.xx), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (200.xx, 202.xx), or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (204.1x).

No patient identity or medical records were disclosed for the purposes of this study. The analysis included only de-identified patients; as such, institutional review board approval and patient consent were not required. All data were accessed using methods that were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness of the index biologic was evaluated for 1 year (12 months) following the index date using a claims-based algorithm that has been described in detail elsewhere.23 For this analysis, the algorithm classified a treatment as effective if the patient had all of the following 6 outcomes:

High adherence: For self-administered SC injections (adalimumab, etanercept, and golimumab), patients were considered to have high adherence if their medication possession ratio was ≥ 80%, calculated as the sum of total days of drug available divided by the 365-day post-index period. Start dates for medication claims that were filled early (i.e., while the patient still had medication from the prior claim) were pushed out until after the medication from the previous claim was set to run out. Patients were allowed to stockpile medication for a maximum of 14 days. The conventional threshold used for adherence is 80%, which is reasonable because it suggests very few days without the drug on hand and, consequently, fairly continuous medication usage. For the IV infusions (abatacept and infliximab), patients were considered to have high adherence if they received at least as many infusions as recommended by the U.S. prescribing information.

No increase in biologic dose: No increase in biologic dose from the first dose to the last dose, as follows—for etanercept, an increase to 50 milligrams (mg) twice weekly; for adalimumab, an increase to 40 mg once weekly; for infliximab, a 100 mg or greater increase or a number of infusions greater than 120% of the number expected; for abatacept, a 100 mg or greater increase; for golimumab, a 25 mg per week or greater increase; for certolizumab pegol, the criterion was not applicable.

No biologic switch: No switch from the index biologic to another biologic approved for use in patients with RA.

No new DMARD: No claim for a nonbiologic DMARD during the 12-month post-index period that the patient had not received during the 6-month pre-index period.

No new or increased oral glucocorticoids: Patients with no oral glucocorticoid prescriptions during the 6-month pre-index period did not initiate oral glucocorticoid treatment (≥ 30-day supply) during the 12-month post-index period. Patients who had received an oral glucocorticoid during the 6-month pre-index period did not increase the dose by ≥ 20% during months 7-12 of the post-index period.

Glucocorticoid injections: No more than 1 parenteral or intra-articular glucocorticoid joint injection on unique days > 90 days after the index date.

Biologic Costs

For each IV biologic, the actual health plan paid and patient paid amounts for all medical and pharmacy claims for that agent and the administration cost for each IV biologic were summed to determine the total cost of the biologic in the first year (365 days) after the index date. For each SC biologic, the total cost included only the medication cost because they are self-administered. Biologic cost per effectively treated patient was defined as follows:

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses of patient demographic and clinical characteristics were conducted for each treatment cohort. Effectiveness using the claims-based algorithm and costs were evaluated across first-line biologic treatments for RA that were administered SC (adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab) and those that were only administered IV (abatacept, infliximab) at the time of the analysis. For the percentage of patients who were categorized as effectively treated per the algorithm criteria, P values were calculated comparing (a) SC versus IV index biologics and (b) across all individual index biologics. For binomial comparisons, P values were calculated using Pearson’s chi-square test. For continuous comparisons, P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. A multivariable analysis was conducted to examine the possible influence of baseline characteristics on the predicted effectiveness of each index biologic. A logistic regression model estimated odds ratios for effectiveness (with 95% confidence intervals) and predicted percentage of patients effectively treated for each index biologic at 1-year post-index. Predicted percentages were calculated using the recycled predictions method.25 Covariates included age group, sex, geographic region, Charlson comorbidity score at index date, pre-index DMARD use, and pre-index total health care cost.

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the total health care costs per effectively treated patient during the first year of biologic therapy as per the previously shown calculation.

Results

Patient Demographics

A total of 5,474 individuals were included in the analysis (Table 1). The most commonly used biologic was etanercept (n = 2,425; 44.3%), followed by adalimumab (n = 1,857; 33.9%), infliximab (n = 773; 14.1%), abatacept (n = 295; 5.4%), and golimumab (n = 124; 2.3%; Table 2). Mean patient age was 48.6 years overall and was similar across cohorts. Most patients were female (77.8%), with a larger percentage of female patients in the abatacept cohort (83.7%) than in the other cohorts. The distribution of patients in the analyses who were from the geographic regions of Northeast, Midwest, South, and West was similar to the overall distribution of enrollees in the health plan, and the geographic distribution was similar across cohorts. Mean values for Charlson comorbidity scores at the index date were similar across cohorts and ranged from 1.27 to 1.47 (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Sample Attrition

| Reason for Attrition | Patients Excluded, n (%) | Patients Remaining, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis + 1 biologic on index date | 70,780 | |

| Not continuously enrolled 180 days prior to index | 24,322 (34.4) | 46,458 (65.6) |

| No rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis pre-index through 30 days after index | 27,950 (60.2) | 18,508 (39.8) |

| Other biologic indication diagnosisa | 2,405 (13.0) | 16,103 (87.0) |

| Any biologic in pre-index period | 7,047 (43.8) | 9,056 (56.2) |

| Not continuously enrolled 365 days after index date | 2,353 (26.0) | 6,703 (74.0) |

| Aged < 18 years on index date | 9 (0.1) | 6,694 (99.9) |

| Invalid demographics (other than age, gender, and region) | 11 (0.2) | 6,683 (99.8) |

| J-code for subcutaneous biologic or NDC number for intravenous biologic | 100 (1.5) | 6,583 (98.5) |

| Aged ≥ 64 years on index date | 735 (11.2) | 5,848 (88.8) |

| Invalid days’ supply, quantity, etc. | 130 (2.2) | 5,718 (97.8) |

| Index biologic was rituximab,b tocilizumab,b or certolizumab pegolc | 244 (4.3) | 5,474 (95.7) |

a See Methods section in this article.

b Not included because it was not approved for first-line treatment of rheumatoid arthritis at the time of the analysis.

c Not included because of small sample available for analysis.

J-code = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code for drugs administered other than by an oral method; NDC = National Drug Code.

TABLE 2.

Patient Demographics and Treatment Characteristics

| Parameter | Total (N = 5,474) | Subcutaneous Biologics | Intravenous Biologics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab (n = 1,857) | Etanercept (n = 2,425) | Golimumab (n = 124) | Abatacept (n = 295) | Infliximab (n = 773) | ||

| Age in years at baseline | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.6 (9.8) | 48.5 (9.6) | 48.2 (10.1) | 48.1 (10.3) | 49.7 (9.4) | 49.6 (9.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 4,258 (77.8) | 1,440 (77.5) | 1,881 (77.6) | 100 (80.7) | 247 (83.7) | 590 (76.3) |

| Male | 1,216 (22.2) | 417 (22.5) | 544 (22.4) | 24 (19.4) | 48 (16.3) | 183 (23.7) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||||

| Northeast | 371 (6.8) | 120 (6.5) | 175 (7.2) | 4 (3.2) | 28 (9.5) | 44 (5.7) |

| Midwest | 1,296 (23.7) | 424 (22.8) | 571 (23.6) | 26 (21.0) | 85 (28.8) | 190 (24.6) |

| South | 3,024 (55.2) | 1,045 (56.3) | 1,330 (54.9) | 77 (62.1) | 142 (48.1) | 430 (55.6) |

| West | 783 (14.3) | 268 (14.4) | 349 (14.4) | 17 (13.7) | 40 (13.6) | 109 (14.1) |

| Charlson comorbidity score at index date | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.35 (0.81) | 1.34 (0.76) | 1.35 (0.82) | 1.27 (0.60) | 1.47 (1.04) | 1.33 (0.80) |

| Pre-index DMARD use, n (%) | ||||||

| Any DMARD | 4,248 (77.6) | 1,484 (79.9) | 1,811 (74.7) | 106 (85.5) | 209 (70.9) | 638 (82.5) |

| Methotrexate | 3,354 (61.3) | 1,165 (62.7) | 1,403 (57.9) | 91 (73.4) | 154 (52.2) | 541 (70.0) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1,224 (22.4) | 432 (23.3) | 527 (21.7) | 24 (19.4) | 65 (22.0) | 176 (22.8) |

| Leflunomide | 685 (12.5) | 242 (13.0) | 301 (12.4) | 16 (12.9) | 41 (13.9) | 85 (11.0) |

| Sulfasalazine | 456 (8.3) | 148 (8.0) | 209 (8.6) | 11 (8.9) | 22 (7.5) | 66 (8.5) |

| Post-index DMARD use, n (%) | ||||||

| Any DMARD | 4,083 (74.6) | 1,451 (78.1) | 1,690 (69.7) | 99 (79.8) | 203 (68.8) | 640 (82.8) |

| Methotrexate | 3,175 (58.0) | 1,126 (60.6) | 1,294 (53.4) | 83 (66.9) | 143 (48.5) | 529 (68.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1,083 (19.8) | 388 (20.9) | 465 (19.2) | 21 (16.9) | 68 (23.1) | 141 (18.2) |

| Leflunomide | 676 (12.3) | 244 (13.1) | 296 (12.2) | 14 (11.3) | 42 (14.2) | 80 (10.3) |

| Sulfasalazine | 331 (6.0) | 111 (6.0) | 139 (5.7) | 6 (4.8) | 21 (7.1) | 54 (7.0) |

DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; SD = standard deviation.

A majority of patients received a DMARD during the 6-month pre-index period (77.6%) and the 12-month post-index period (74.6%). Claims for DMARD treatment were most commonly for methotrexate (61.3% pre-index and 58.0% post-index), followed by hydroxychloroquine (22.4% pre-index and 19.8% post-index), leflunomide (12.5% pre-index and 12.3% post-index), and sulfasalazine (8.3% pre-index and 6.0% post-index); the rank order was similar across biologics (Table 2).

Effectiveness

Overall, the algorithm classified first-line biologics as effective in 28.9% of patients. The proportion of patients by cohort who satisfied all 6 effectiveness criteria ranged from 19.0% for infliximab to 32.7% for etanercept. All 6 effectiveness criteria were satisfied in 30.6% of patients who received SC biologics and in 22.1% of patients who received IV biologics (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Effectiveness (As Assessed by the Claims-Based Algorithm)

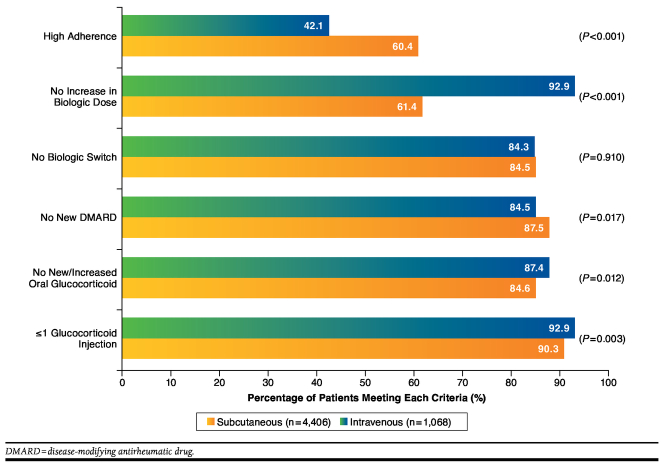

Achievement rates overall for the individual criteria, in descending order, were ≤ 1 glucocorticoid injection (92.4%), no new/increased oral glucocorticoid (86.9%), no increase in biologic dose (86.7%), no new DMARD (85.1%), no biologic switch (84.3%), and high adherence (45.7%; Table 3). Criterion achievement rates for all SC biologics combined and all IV biologics combined are shown in Figure 2. Compared with patients who initiated biologic treatment with IV biologics, those who initially received SC biologics were significantly more likely to meet the criteria for high adherence (60.4% vs. 42.1%; P < 0.001) or receive no new DMARD (87.5% vs. 84.5%; P = 0.017). A significantly greater proportion of patients who began biologic treatment with an SC biologic compared with an IV biologic met the criteria for no increased biologic dose (92.9% vs. 61.4%; P < 0.001), no oral glucocorticoid use (87.4% vs. 84.6%; P = 0.012), and ≤ 1 glucocorticoid injection (92.9% vs. 90.3%; P = 0.003). SC and IV biologics had similar rates for not switching biologics (84.3% vs. 84.5%; P = 0.910).

TABLE 3.

Percentage of Patients Meeting Each Algorithm Criterion by Biologic

| Algorithm Criterion | Percentage of Patients Meeting the Criterion, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 5,474) | Subcutaneous Biologics | Intravenous Biologics | ||||

| Adalimumab (n = 1,857) | Etanercept (n = 2,425) | Golimumab (n = 124) | Abatacept (n = 295) | Infliximab (n = 773) | ||

| High adherence | 45.7 (44.3-47.0) | 41.8 (39.6-44.1) | 42.2 (40.3-44.2) | 42.7 (33.9-51.9) | 48.8 (43.0-54.7) | 64.8 (61.3-68.2) |

| No increase in biologic dose | 86.7 (85.8-87.6) | 86.0 (84.3-87.6) | 97.8 (97.1-98.3) | 99.2 (95.6-100.0) | 92.5 (88.9-95.3) | 49.6 (46.0-53.1) |

| No biologic switch | 84.3 (83.4-85.3) | 83.7 (81.9-85.3) | 85.2 (83.7-86.6) | 77.4 (69.0-84.4) | 83.1 (78.3-87.2) | 85.2 (82.3-87.4) |

| No new DMARD | 85.1 (84.1-86.0) | 83.8 (82.1-85.5) | 84.8 (83.3-86.2) | 89.5 (82.7-94.3) | 85.4 (80.9-89.3) | 88.2 (85.7-90.4) |

| No new/increased oral glucocorticoid | 86.9 (86.0-87.8) | 87.1 (85.5-88.6) | 87.7 (86.3-89.0) | 87.9 (80.8-93.1) | 86.8 (82.4-90.4) | 83.7 (80.9-86.2) |

| ≤ 1 glucocorticoid injection | 92.4 (91.7-93.1) | 92.7 (91.5-93.9) | 93.2 (92.1-94.1) | 91.1 (84.7-95.5) | 90.9 (87.0-93.9) | 90.0 (87.7-92.1) |

CI = confidence interval; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of Patients Meeting Each Algorithm Criterion, Subcutaneous Versus Intravenous Biologics

Criterion achievement rates by medication cohort are shown in Table 3. Criterion achievement rates for concomitant treatments (no new DMARD, no oral glucocorticoid, and ≤ 1 glucocorticoid injection) were generally similar across individual biologics. Greater variation across biologics was seen in the criteria for high adherence, no increased biologic dose, and no biologic switch.

In the multivariable analysis (Table 4), patient age, region, baseline DMARD use, and baseline health care cost were each statistically significantly associated with effectiveness. In addition, the predicted effectiveness of each index biologic ranged from 18.6% for infliximab to 33.1% for etanercept. Because the predicted values from the multivariable analysis were comparable with the rates from direct application of the algorithm (Figure 1), the rates from the algorithm were used for the estimations of cost per effectively treated patient.

TABLE 4.

Predicted Effectiveness of Each Index Biologic: Multivariable Analysis

| Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P Value | Predicted Effectiveness (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index biologic | |||||

| Abatacept | 0.960 | 0.733 | 1.258 | 0.768 | 32.2 |

| Adalimumab | 0.751 | 0.656 | 0.859 | < 0.001 | 27.3 |

| Etanercept | Ref | – | – | – | 33.1 |

| Golimumab | 0.919 | 0.622 | 1.359 | 0.672 | 31.3 |

| Infliximab | 0.453 | 0.370 | 0.554 | < 0.001 | 18.6 |

| Age group in years | |||||

| 18-34 | 0.784 | 0.629 | 0.976 | 0.030 | – |

| 35-44 | 0.876 | 0.740 | 1.036 | 0.122 | – |

| 45-54 | 0.946 | 0.820 | 1.092 | 0.451 | – |

| 55-63 | Ref | – | – | – | – |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1.145 | 0.993 | 1.320 | 0.062 | – |

| Female | Ref | – | – | – | – |

| Geographic region | |||||

| Northeast | 1.575 | 1.249 | 1.984 | < 0.001 | – |

| Midwest | 1.217 | 1.052 | 1.408 | 0.008 | – |

| South | Ref | – | – | – | – |

| West | 1.301 | 1.092 | 1.549 | 0.003 | – |

| Charlson comorbidity score at index date | 0.937 | 0.857 | 1.024 | 0.150 | – |

| Pre-index DMARD use | 2.208 | 1.880 | 2.594 | < 0.001 | – |

| Pre-index total health care cost | 0.984 | 0.976 | 0.992 | < 0.001 | – |

CI = confidence interval; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; Ref = reference.

The results of the sensitivity analysis were consistent with those of the planned analysis. The rank order was the same in each analysis, except for golimumab and etanercept (golimumab 7% lower than etanercept for total estimated health care costs per effectively treated patient in the sensitivity analysis and etanercept 11% lower than golimumab for estimated biologic cost per effectively treated patient in the planned analysis). In both analyses, all other biologics had estimated costs per effectively treated patient that were at least 15% to 20% higher than those for etanercept.

Cost

One-year costs of the index biologic per patient (Table 5) were lower for the SC biologics (etanercept, $14,385; adalimumab, $14,601; golimumab, $15,997) than for the IV biologics (abatacept, $18,796; infliximab, $19,283). Administration cost was approximately $1,900 per patient annually for IV biologics.

TABLE 5.

Cost of Index Biologic in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Parameter | Subcutaneous Biologics | Intravenous Biologics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab (n = 1,857) | Etanercept (n = 2,425) | Golimumab (n = 124) | Abatacept (n = 295) | Infliximab (n = 773) | |

| Index biologic cost a | |||||

| Mean ($) | 14,601 | 14,385 | 15,997 | 16,861 | 17,396 |

| 95% CI ($) | (14,256-14,946) | (14,102-14,669) | (14,713-17,280) | (14,767-18,955) | (16,606-18,186) |

| Administration cost a | |||||

| Mean ($) | 0b | 0b | 0b | 1,934 | 1,888 |

| 95% CI ($) | (0-0) | (0-0) | (0-0) | (1,772-2,097) | (1,802-1,973) |

| Total cost a | |||||

| Mean ($) | 14,601 | 14,385 | 15,997 | 18,796 | 19,283 |

| 95% CI ($) | (14,256-14,946) | (14,102-14,669) | (14,713-17,280) | (16,653-20,938) | (18,449-20,118) |

| Patients categorized as effectively treated c | |||||

| n (%) | 514 (27.7) | 794 (32.7) | 40 (32.3) | 89 (30.2) | 147 (19.0) |

| Biologic cost per effectively treated patient | |||||

| Mean ($) | 52,752 | 43,935 | 49,589 | 62,300 | 101,402 |

| 95% CI ($) | (51,503-53,996) | (43,073-44,805) | (45,608-53,565) | (55,197-69,400) | (96,998-105,773) |

a Costs are rounded to the dollar for clarity.

b Subcutaneous biologics have no administration cost because they are self-administered.

c Patients who did not fail any of the 6 algorithm criteria throughout the 12-month post-index period.

CI = confidence interval.

The total cost of the index biologic, divided by number of patients who met all 6 algorithm criteria throughout the 12-month post-index period, yielded an estimate of the biologic cost per effectively treated patient for each biologic (Table 5). Using this estimate, the biologic cost per effectively treated patient was lower among patients treated with SC biologics (etanercept, $43,935; golimumab, $49,589; adalimumab, $52,752) than among patients treated with IV biologics (abatacept, $62,300; infliximab, $101,402).

Discussion

This analysis used a claims-based algorithm that examines various aspects of the treatment pathway including adherence, switching, dose escalation, use of a nonbiologic DMARD, and use of oral and injectable glucocorticoids23,24 to estimate treatment effectiveness among commercially insured patients with RA. Using this algorithm, effectiveness was observed in a greater proportion of patients initiating first-line treatment with SC biologics compared with IV biologics. Additionally, the average biologic cost per effectively treated patient was lower among patients who began treatment with a self-injectable medication. These results suggest that benefit designs for biologics that incentivize the use of products covered under medical benefits (IV biologics) over those that are covered under pharmacy benefits (SC biologics) could result in increased use of agents with a higher biologic cost per effectively treated patient.

Etanercept had both the greatest proportion of effectively treated patients according to the algorithm and the lowest total cost in the first year, resulting in the lowest estimated biologic cost per effectively treated patient. The other biologics had estimated costs per effectively treated patient that were between 13% and 131% higher than that for etanercept. The high biologic cost per effectively treated patient in the infliximab cohort resulted from it having both the lowest percentage of patients categorized as effectively treated and the highest total biologic cost. Although infliximab had more patients who met the high adherence criterion compared with the other biologics, this was offset by a high rate of biologic dose increases in the infliximab cohort. This may be explained in part by the large allowed dose range and dose adjustment recommendations in the labeling for adalimumab and infliximab,6,10 and with several previous reports that dose increases are more common with these TNF blockers than with etanercept.26-34 Because only the initial dose of the index biologic was considered in the evaluation of treatment effectiveness, it is possible that some of the subjects in whom the initial dose of infliximab was ineffective subsequently responded to the higher dose, which would have lowered the biologic cost per effectively treated patient for infliximab. The definition of dose increases for the IV biologics may have contributed to the high rate of dose increases for infliximab, but 92.5% of subjects did not have a dose increase for the other IV biologic, abatacept.

Overall, the findings of this analysis were similar to those of a recent CER review sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which found greater improvement in disease activity (50% improvement in the ACR Core Data Set measures [ACR50]) among patients who received etanercept than among patients who received abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, infliximab, rituximab, or tocilizumab.35

Randomized head-to-head clinical studies have not reported significant differences in efficacy between biologics in the management of RA,12-17 except for 1 study that reported significantly greater reduction of the signs and symptoms of RA with tocilizumab monotherapy than with adalimumab monotherapy.18 To date, these studies have been used to compare only 2, or at most 3, of the approved biologics. A retrospective claims database analysis is a less expensive, rapid, and pragmatic way to estimate costs and effectiveness across all available biologics in clinical practice. Effectiveness cannot be assessed directly from claims; thus, a proxy such as this algorithm is needed to assess effectiveness from claims data. In this study, first-line biologics for treatment of moderate-to-severe RA were classified by the algorithm as effective in less than one-third of patients (28.9%) at 1 year. This rate is consistent with at least 1 registry-based report and with the rate reported in the original validation of the algorithm.17,23 Higher efficacy rates are reported in the U.S. prescribing information for biologics, based on ACR20 or ACR50 criteria in randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies. These criteria include 20% (or 50%) improvement in tender and swollen joint counts and 20% (or 50%) improvement in 3 of 5 remaining ACR core set measures: patient and physician global assessments, pain, disability, and an acute-phase reactant.36,37 The rates of effectiveness according to the algorithm (both in this study and in the VARA validation study) were more consistent with efficacy reported for ACR70 (70% improvement in tender and swollen joint counts and 70% improvement in 3 of 5 remaining ACR core set measures37) in randomized clinical studies. A possible explanation for this finding is that the algorithm was validated against relatively stringent criteria of low disease activity (a DAS-28 score of < 3.2) or improvement in the DAS-28 score by > 1.2 units, with high adherence to therapy.23

The algorithm originally was validated in the VA system,23 which is one of the few health care systems that has both pharmacy and medical claims data that could be linked to a nested RA registry. The VA system is predominantly male, while the general RA population is predominantly female, which may limit generalizability. However, the high positive predictive value of the algorithm was also evaluated in a commercial claims database, and 76% of the patients in that study were female.24 Two recently published studies also used the algorithm and managed care databases to examine biologic effectiveness and costs in patients with RA, and the results of those studies were consistent with the findings of this study.38,39

This analysis examined biologic costs because there is a clear relationship between the cost and the effect of the index biologic, whereas total health care costs include many other costs unrelated to RA or effective biologic treatment. Even when other health care costs are directly related to the effective treatment of RA, it is difficult to establish cause and effect. Another issue with evaluating total health care costs in the first year per effectively treated patient is timing. A proper evaluation of the total costs associated with effective biologic therapy should look at the “downstream” costs after the biologic has been categorized as effective. Analysis of costs in subsequent years, after the index biologic was effective in the first year, was beyond the scope of this study. Despite these limitations, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the total health care costs per effectively treated patient during the first year of biologic therapy. The results of the sensitivity analysis were consistent with those of the planned analysis, although interpretation of this finding is complicated by the much smaller sample size for the golimumab group (n = 124) than for the etanercept group (n = 2,425).

Limitations

These results from a commercially insured population in the United States may not be generalizable to other populations.

Disease severity is not captured in medical claims, so it is not possible to determine if there was a selection bias that favored the use of certain biologics in patients who were more likely to achieve the effectiveness criteria with the algorithm and the use of other biologics in patients who were more likely to fail the criteria. During the period covered by the analysis, the formulary allowed equal access to each of the biologics, so it is unlikely that formulary design influenced utilization patterns. Additionally, several baseline characteristics were significant predictors of response, but a multivariable analysis that included those variables resulted in predicted rates of effectiveness for each biologic that were comparable with the rates from direct application of the algorithm.

Nonbiologic costs such as DMARD treatment, glucocorticoids, and laboratory monitoring and the costs of adverse events were not included in the analysis, but these costs would be expected to have a minor influence on the total cost of biologic therapy. Concomitant use of DMARDs generally was similar between biologics, and the costs of these drugs were not included because they are typically generic and inexpensive. Costs of adverse events attributable to a specific treatment cannot readily be distinguished from other health care costs in a claims database, and adverse events that resulted from biologic treatment would likely be similar between biologics.35

A patient needed to satisfy all 6 algorithm criteria for a biologic to be categorized as effective, and some of the individual criteria may have contributed to lower than expected rates of effectiveness. As previously described, the prescribing information for some biologic therapies recommends dose escalation as needed to manage RA, but the effectiveness algorithm does not permit dose escalation and does not assess effectiveness at the higher dose. Dose escalation of anti-TNF agents has shown only limited effectiveness in the long-term control of RA (mainly for infliximab and less so for other biologics).34,40,41 Similarly, approximately 15% of patients failed the criterion for increased corticosteroid doses, but in clinical practice, this may enable patients to achieve clinical endpoints without changing the dose of the biologic. Conversely, the low adherence criterion caused a substantial proportion of both SC and IV biologics to be classified as “not effective”; some patients may reduce the frequency of dosing or stop the medication when their symptoms improve (i.e., the medication is highly effective), yet the algorithm would categorize the biologic as “not effective.” Because the algorithm was previously validated and shown to have high sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value for evaluating the effectiveness of IV or SC biologic treatment in RA patients,23 any modification to address potential limitations would require further validation before the algorithm could be applied to cost analyses.

Conclusions

When a claims-based algorithm for biologic effectiveness in RA was applied to a large commercially insured population, etanercept was classified as the most effective biologic and had the lowest biologic cost per effectively treated patient. This study demonstrates the value of applying a transparent claims-based medication effectiveness algorithm to claims data to support findings from clinical trials and inform formulary decision makers by using data that are readily available in a population of interest. Additional research is warranted to determine if these findings apply to other patient populations (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid) and to other uses of biologics in RA such as secondline biologic treatment or longer-term biologic treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by Jonathan Latham (PharmaScribe, LLC, on behalf of Amgen Inc.) and Julie Wang (Amgen Inc.).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Immunex Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Amgen Inc., and by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc. in October 2009. Curtis has received consulting fees or honoraria from Roche/Genentech, UCB, Janssen, CORRONA, Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo, and AbbVie. Chastek and Becker are employees of Optum, which received consulting fees for conducting the study from Amgen Inc. Quach was a graduate intern at Amgen Inc. and Joseph was employed by Amgen at the time of this report. Yun has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Harrison and Collier are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc. Joseph is an employee and stockholder of Sanofi and a former employee and stockholder of Amgen Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.23177/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, Marynchenko M, Kidolezi Y, Cifaldi M. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the U.S. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-84. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.23721/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(5):625-39. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.21641/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ORENCIA (abatacept) for injection for intravenous use; for injection for subcutaneous use. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Revised December 2014. Available at: http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_orencia.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.HUMIRA (adalimumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Abbott Laboratories. Revised December 2014. Available at: http://www.rxabbott.com/pdf/humira.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CIMZIA (certolizumab pegol) for injection, for subcutaneous use; injection, for subcutaneous use. UCB, Inc. Revised October 2013. Available at: http://www.cimzia.com/assets/pdf/Prescribing_Information.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enbrel (etanercept) solution for subcutaneous use. Immunex Corporation. Revised November 2013. Available at: http://pi.amgen.com/united_states/enbrel/derm/enbrel_pi.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.SIMPONI (golimumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Janssen Biotech, Inc. Revised December 2014. Available at: http://www.simponi.com/shared/product/simponi/prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.REMICADE (infliximab) lyophilized concentrate for injection, for intravenous use. Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc. Revised January 2015. Available at: http://www.remicade.com/hcp/remicade/assets/hcp_ppi.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACTEMRA (tocilizumab) injection, for intravenous use; injection, for subcutaneous use. Genentech, Inc. Revised November 2014. Available at: http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/actemra_prescribing.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estellat C, Ravaud P. Lack of head-to-head trials and fair control arms: randomized controlled trials of biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):237-44. Available at: http://archinte.jamanet-work.com/article.aspx?articleid=1108719. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(8):1096-103. Available at: http://ard.bmj.com/content/67/8/1096.long. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):28-38. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.37711/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kume K, Amano K, Yamada S, Hatta K, Ohta H, Kuwaba N. Tocilizumab monotherapy reduces arterial stiffness as effectively as etanercept or adalimumab monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(10):2169-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):508-19. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1112072. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg JD, Reed G, Decktor D, et al. A comparative effectiveness study of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in biologically naive and switched rheumatoid arthritis patients: results from the U.S. CORRONA registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1134-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1541-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strand V, Sokolove J. Randomized controlled trial design in rheumatoid arthritis: the past decade. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):205. Available at: http://arthritis-research.com/content/11/1/205. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokka T, Pincus T. Most patients receiving routine care for rheumatoid arthritis in 2001 did not meet inclusion criteria for most recent clinical trials or american college of rheumatology criteria for remission. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1138-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brass EP. The gap between clinical trials and clinical practice: the use of pragmatic clinical trials to inform regulatory decision making. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(3):351-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaver TS, Anderson JD, Weidensaul DN, et al. The problem of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity and remission in clinical practice. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(6):1015-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Baddley JW, Yang S, et al. Derivation and preliminary validation of an administrative claims-based algorithm for the effectiveness of medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(5):R155. Available at: http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/5/R155. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JR, Chastek B, Becker L, et al. Further evaluation of a claims-based algorithm to determine the effectiveness of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis using commercial claims data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(2):404. Available at: http://arthritis-research.com/content/15/2/404. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Estimating marginal and incremental effects on health outcomes using flexible link and variance function models. Biostatistics. 2005;6(1):93-109. Available at: http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org/content/6/1/93.long. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert TD Jr, Smith D, Ollendorf DA. Patterns of use, dosing, and economic impact of biologic agent use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5(1):36. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/5/36. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal SK, Maier AL, Chibnik LB, et al. Pattern of infliximab utilization in rheumatoid arthritis patients at an academic medical center. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):872-78. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.21582/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger A, Edelsberg J, Li TT, Maclean JR, Oster G. Dose intensification with infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(12):2021-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etemad L, Yu EB, Wanke LA. Dose adjustment over time of etanercept and infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interface. 2005;18(4):21-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, Yang E, Cifaldi M. Retrospective claims data analysis of dosage adjustment patterns of TNF antagonists among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(8):2229-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and association with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up. JAMA. 2011;305(14):1460-68. Available at: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=896649. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moots RJ, Haraoui B, Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Differences in biologic dose-escalation, non-biologic and steroid intensification among three anti-TNF agents: evidence from clinical practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(1):26-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Fox KM, Wilson KL. Tumor necrosis factor blocker dose escalation among biologic naive rheumatoid arthritis patients in commercial managed-care plans in the 2 years following therapy initiation. J Med Econ. 2012;15(4):635-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schabert VF, Bruce B, Ferrufino CF, et al. Disability outcomes and dose escalation with etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a US-based retrospective comparative effectiveness study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(4):569-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donahue KE, Jonas D, Hansen RA, et al. Drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in adults: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 55. (Prepared by RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC025-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2012. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/203/1044/CER55_DrugTherapiesforRheumatoidArthritis_FinalReport_20120618.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(6):727-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Lange ML, Wells G, LaValley MP. Should improvement in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials be defined as fifty percent or seventy percent improvement in core set measures, rather than twenty percent? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1564-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis JR, Schabert VF, Harrison DJ, et al. Estimating effectiveness and cost of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: application of a validated algorithm to commercial insurance claims. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):996-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis JR, Schabert VF, Yeaw J, et al. Use of a validated algorithm to estimate the annual cost of effective biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ. 2014;17(8):555-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis JR, Chen L, Luijtens K, et al. Dose escalation of certolizumab pegol from 200 mg to 400 mg every other week provides no additional efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of individual patient-level data. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(8):2203-08. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.30387/abstract. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavelka K, Jarosova K, Suchy D, et al. Increasing the infliximab dose in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomised, double blind study failed to confirm its efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(8):1285-89. Available at: http://ard.bmj.com/content/68/8/1285.long. Accessed February 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]