Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Managing and treating patients with multiple chronic conditions presents challenges on many levels. Pharmacist-delivered medication therapy management (MTM) services, mandated as part of the Medicare Part D drug benefit, are designed to help patients manage their chronic conditions and medications.

OBJECTIVE:

To identify factors that influence patient understanding and use of MTM services and potential strategies to educate individuals about MTM.

METHODS:

Participants who had at least 2 chronic conditions, were taking 2 or more prescription medications, and were aged 18 years or older were recruited from community-based settings to participate in focus groups. The focus groups aimed to identify participants’ perceptions and use of MTM services, barriers and facilitators to utilization, and medication problems. Participants were asked to complete a 14-item health care questionnaire and view a brief, 3-minute video introducing the topic of MTM before the group discussion. The health care questionnaire data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel. The focus group responses were transcribed and entered into the computer program ATLAS.ti for thematic analysis. Two independent reviewers qualitatively coded the discussion question responses; a third reviewer investigated discrepancies and facilitated consensus among the reviewers.

RESULTS:

Participants (N = 27) were mostly female (70.4%), college educated (62.9%), and had Medicare insurance (81.5%). Seven themes were identified: (1) new proposed names for MTM, (2) mechanisms to gain interest in and to promote the value of MTM, (3) familiarity with MTM, (4) pharmacists’ training and expertise in MTM, (5) experience with MTM, (6) reasons for nonparticipation in MTM, and (7) preferred method to learn about MTM. Participants did not understand the term “medication therapy management” and felt the interpretation of “therapy”’ differed between health care professionals and the public. Some participants used MTM services to learn about appropriate use of their medications, while others were unsure about their eligibility, associated costs, and how to access the services. Participants had limited pharmaceutical knowledge but felt pharmacist-provided MTM services were helpful. Participants were unfamiliar with pharmacists’ skills and training. Participants’ experiences with MTM services ranged from disregarding the invitation to participate to having pharmacists identify drug-drug interactions. Reasons for nonparticipation in MTM services included being unaware of their eligibility, failing to read excessive information from insurance companies, and being uncertain of the identity of the telephone caller. Preferred methods for learning more about MTM services included the Internet, e-mail, information availability at physician’s office, and television advertisements.

CONCLUSIONS:

These results suggest that the lay public remains largely unaware of MTM services and that the term “MTM” is not well understood. Clearly, tailored public health campaigns and patient engagement strategies are needed to promote MTM in chronic disease management, pharmacists as respected providers, and the importance of the prescriber-MTM pharmacist collaborative relationship in managing medications for patients with multiple chronic conditions.

What is already known about this subject

Managing and treating patients with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) is costly and constitutes a public health as well as a health care challenge.

Pharmacist-provided medication therapy management (MTM) services can help improve outcomes in patients with MCC.

A small percentage of patients who are eligible to receive pharmacist-provided MTM actually use the services.

What this study adds

Through the use of a 14-item health care questionnaire, this focus group study identified 7 MTM-related themes regarding patient perceptions and knowledge of MTM services.

Although the sample of patients with MCC was largely unaware and had limited knowledge of MTM services, it provided valuable insight regarding some of the reasons why patients underuse these services.

This study provided additional evidence to support the need for effective communication and engagement strategies to help patients understand what MTM is, who is eligible to receive it, and how to use these vital services to help manage their chronic conditions.

Chronic disease is a global problem.1 Managing and treating patients with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) is costly and constitutes a real public health challenge.2 More than two thirds (71%) of total U.S. health care expenditures are related to individuals with 1 or more chronic conditions—those who are more likely to take and have to manage multiple medications.3 QuintilesIMS, formerly the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, identified 6 areas requiring urgent attention to reduce health care costs and improve medication use, including medication nonadherence ($105 billion) and mismanaged polypharmacy in elderly patients ($1.3 billion).4 Pharmacist-provided medication therapy management (MTM) services can help address these problems.4,5 MTM encompasses a range of services offered by a pharmacist, including comprehensive medication reviews, disease support and coaching, medication safety surveillance, and prevention or wellness services.6

MTM services were mandated as part of the Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (also called the Medicare and Modernization Act [MMA]) of 2003 to help patients manage their chronic conditions and medications through their Medicare Part D drug benefits.7 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) set these program requirements for targeted Medicare beneficiaries who (a) have multiple chronic conditions, (b) take multiple medications, and (c) incur annual projected drug costs above a predetermined limit (new dollar limits are established for each calendar year).8 For 2010, CMS expanded the requirements for beneficiaries with the intent of increasing the number of individuals eligible for MTM services.8 Based on the evident need for these services, some states are now extending MTM services to Medicaid beneficiaries as well.

Moreover, MTM services are effective in reducing the number of medication-related problems and hospital readmission,9,10 while pharmacist-provided services, such as MTM and patient education, also decrease emergency department visits11 and health care costs.12,13 Yet, MTM services are underutilized, with only about 11% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in them.14 Despite the evidence supporting MTM’s effectiveness and the changes made by CMS to increase the number of beneficiaries enrolled in MTM programs, patients are still largely unaware of the available services and beneficial effects.15,16 Almost two thirds (60%) of patients surveyed were unaware of MTM services, and most (86%) had never received a medication action plan.16 Law et al. (2008) found that most patients surveyed felt they did not need MTM, yet more than half (58%) expressed the belief that pharmacists were good candidates for providing these services.15 Additionally, roughly one third (31%) of patients were willing to pay for MTM services,15 and more than half of those surveyed preferred to talk to a pharmacist or receive brochures to help them learn more about MTM services.16

To address these challenges, this project used a series of focus group sessions, conducted in various community-based settings, to identify individuals’ perceptions about and use of MTM services. The objectives were to (a) conduct a needs assessment (via focus groups) to elicit information regarding factors (perceptions, beliefs, barriers, promoters) that influence understanding and use of MTM services and (b) process focus group evaluation results to identify potential strategies to educate individuals about MTM services.

Methods

Study Design, Sample Population, and Recruitment

This project used a cross-sectional design to identify perceptions about and use of MTM services.

The sample population (N = 27) was composed of individuals from Tucson, Arizona, and surrounding areas. To participate in the project, individuals were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) have at least 2 chronic conditions, (b) take at least 2 prescription medications, and (c) be aged 18 years or older. All eligible individuals, regardless of their previous/current use or nonuse of MTM services, were encouraged to participate.

Participants from various community-based settings (i.e., community center, retirement community, and lifelong learning center) were recruited to maximize the potential for a diverse group of participants (e.g., age, health insurance status, and use/non-use of MTM services). The research team worked closely with staff at the participating sites to disseminate recruitment materials, depending on the organization’s preferred communication channels (e.g., community newspaper, group e-mail, and on-site).

The university’s institutional review board regarded this project as an evaluation.

Focus Group Sessions

A series of 3 focus group sessions were conducted between October 2014 and March 2015 at 3 community facilities. Each focus group consisted of 7-15 individuals, and each session lasted approximately 1 hour. Participants received no compensation for their time; however, light refreshments were provided at each session.

A focus group guide, designed specifically for this project, served to ensure consistency in procedures and reduce bias across the focus group facilitators and individual sessions. Two investigators (Warholak and Taylor) conducted the on-site focus groups and served as session facilitators. One or more notetakers documented participants’ responses to the discussion questions. Sessions were audio-recorded for transcription to identify key issues and comments and for verification purposes. All responses to the questionnaire items and discussion questions were anonymous.

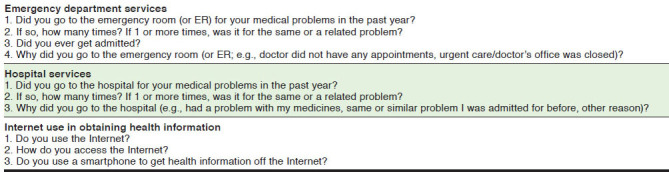

Health Care Utilization and Demographics Questionnaire

Participants were asked to complete the 14-item health care questionnaire at the beginning of the focus group session. The questionnaire elicited information regarding (a) health care utilization in the past year such as number of visits and reason for visits by facility type (emergency department, hospital; 4 items); (b) demographic information (e.g., gender, education level, health insurance status; 7 items); and (c) use of technology to obtain health-related information such as Internet use, type of device used to access the Internet, and smartphone use for accessing health information; 3 items). Figure 1 provides more detailed information.

FIGURE 1.

Questionnaire Items for Health Care Services and Internet Use

MTM Video

Participants viewed a brief, 3-minute video introducing the topic of MTM, presented by the director of a university-based medication management service. The video presented the following information: (a) definition of MTM, (b) identification of patients who can benefit from MTM, (c) purpose of MTM (e.g., to reduce adverse drug-related events and medication costs), and (d) recognition of pharmacists’ training and role in helping patients achieve their desired health outcomes.

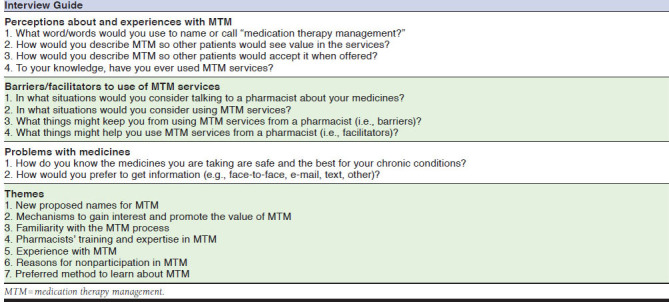

Discussion Questions

Discussion questions were designed specifically for this project by an interprofessional team of investigators, and the topics addressed were based on the relevant literature and expert opinion provided by 2 authors (Boesen and Martin) who have extensive experience managing a large national MTM program. The 10 discussion questions are included in Figure 2. Only 1 of the participants had used MTM services before participating in the focus group session. All responses to the discussion questions were anonymous. The transcription service Rev (https://www.rev.com/) was hired to transcribe the audiotaped sessions.

FIGURE 2.

Discussion Questions and Themes Identified During Focus Groups Eliciting Information About MTM Services

Data Analysis

The health care questionnaire data included descriptive statistics that were analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Transcribed responses from the focus groups were entered into ATLAS.ti, version 7 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) to conduct the thematic (qualitative) analysis. Two independent reviewers qualitatively coded the discussion question responses (Campbell and Fair). Discrepancies between the independent reviews were investigated by a blinded, third independent reviewer (Axon) who facilitated consensus among the reviewers. Response saturation—the point whereby no new ideas or information emerges—was achieved after the third focus group session; therefore, no additional focus group sessions were conducted.17

Results

A total of 27 individuals participated in the project. The majority were female (n = 19, 70.4%) and had Medicare insurance (n = 22, 81.5%); individual insurance was the next most commonly reported insurance type (n = 5, 18.5%). Roughly two thirds (n = 17, 62.9%) had a college degree or postgraduate/professional degree and were of Medicare age.

Most participants who replied to this questionnaire (n = 24, 88.9%) reported not using emergency department services in the past year; however, of those who did (n = 3, 11.1%), two thirds were subsequently hospitalized (n = 2, 66.7%). Only 1 participant (4.2%) reported being hospitalized in the past year, without previous emergency department use. Table 1 presents more specific sociodemographic and past-year health care utilization information.

TABLE 1.

Participant Responses to Survey Questions Regarding Sociodemographic Characteristics and Past-Year Health Care Utilization

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 27 (100.0) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 19 (70.4) |

| Male | 7 (25.9) |

| Not reported | 1 (3.7) |

| Education | |

| High school or equivalent | 6 (22.2) |

| Some college or technical training | 4 (14.8) |

| College graduate | 9 (33.3) |

| Postgraduate or professional degree | 8 (29.6) |

| Health insurance statusa | |

| Medicare | 22 (81.5) |

| Individual insurance | 5 (18.5) |

| Group insurance | 4 (14.8) |

| Health savings | 2 (7.4) |

| Other | 3 (11.1) |

| Not reported | 1 (3.7) |

| ED use in past year | |

| No | 24 (88.9) |

| Yes | 3 (11.1) |

| After ED use, admitted to hospital | |

| No | 1 (33.3) |

| Yes | 2 (66.7) |

| Hospitalized in past year | |

| No | 24 (88.9) |

| Yes | 2 (7.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (3.7) |

| Times hospitalized in past year | |

| 0 times | 24 (88.9) |

| 1 time | 2 (7.4) |

| Not reported | 1 (3.7) |

aThe numbers and percentages do not equal 100%, since some individuals reported having more than 1 type of insurance.

ED = emergency department.

Overall, participants reported relatively high use of the Internet (n = 21, 77.8%). When asked how they accessed the Internet (n = 21), some indicated that they used a computer (n = 12); others used a computer and a smartphone (n = 8); and 1 respondent used only a smartphone. Finally, of the 19 respondents to this question, 31.6% (n = 6) reported using the Internet to access health-related information, while most (n = 13, 68.4%) did not. Figure 1 shows specific questionnaire items.

For the focus group discussion, participants were asked a series of questions surrounding 3 major topic areas: perceptions and use of MTM; barriers and facilitators to use of MTM services; and problems with medicines. The 3 focus group sessions elicited 7 main themes: (1) new proposed names for MTM, (2) mechanisms to gain interest in and to promote the value of MTM, (3) familiarity with the MTM process, (4) pharmacist training and expertise in MTM, (5) experience with MTM, (6) reasons for nonparticipation in MTM, and (7) preferred method to learn about MTM. The 7 themes, accompanied by representative quotes from participants, are described in the following sections. Figure 2 lists specific discussion questions and themes generated from the focus group sessions.

Theme 1: New Proposed Names for MTM

Participants felt that the term “medication therapy management” was neither clearly understood nor meaningful to the general public. This rationale was provided: “It is very likely that in your department and your school the term medication therapy is very clearly understood, that it’s used on a regular basis. I really don’t (understand).” They also expressed that the word “therapy” has a different meaning to the public (i.e., physical therapy, psychotherapy) than to professionals.

Participants proposed several new names for MTM services and suggested integrating some common terms (e.g., “medication” and “management”). For instance, “managing multiple medications” was combined with reference to personalization of the service to meet the patient’s needs. Some suggested names included “medication management,” “multiple medication management,” and “personal or individual medication management.” The common rationale for these suggestions included: “Personal really is a powerful word there because you’re talking directly to the person.”

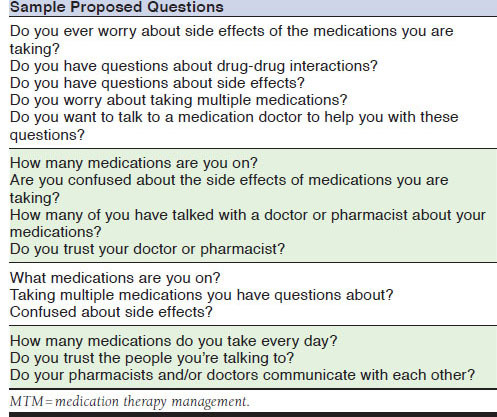

Theme 2: Mechanisms to Gain Interest in and to Promote the Value of MTM

Participants reported reasons why they were likely to use MTM services, such as wanting to speak to somebody to learn more about their medications and how to use them. For example, participants suggested educating patients about pharmacists’ extensive formal training and experience with medications. Participants expressed that this information might benefit those patients who felt that if the information did not come from a physician they would not use the service. They also expressed that patients would not use MTM if they did not know what it was. Finally, they recommended posing questions to spark the public’s interest in MTM. Figure 3 indicates specific questions offered by participants to prompt interest in MTM.

FIGURE 3.

Sample Questions Proposed by Focus Group Participants for the Public to Prompt Interest in Learning About MTM

Representative comments included: “I would welcome talking to somebody who’s independent of the physicians or the insurance company or the pharmaceutical that’s supplying the drugs” and “How does the public learn about this?” Participants recognized that MTM services can have beneficial effects in the future. A representative quote was “It does have a lot of downstream effects if it’s done well.”

Theme 3: Familiarity with the MTM Process

Participants were unclear about whether or not they were eligible or had to pay for the services, as well as how to proceed with the MTM process (e.g., making an appointment). Representative comments included: “Are you automatically eligible for it?”; “Is it a pay service?”; and “If we went up to our pharmacist and said that big long word, that we want that thing, we make an appointment because it takes a long time?”

Theme 4: Pharmacist Training and Expertise in MTM

Participants indicated that they had limited pharmaceutical knowledge, expressing uncertainty about the availability and equivalency of generic drugs versus branded drugs. Representative comments included: “Are generics the same?” and “What is the deal on insulin? I understand there is no generic insulin. Why is that?” In addition, some participants had limited understanding of the training and expertise of pharmacists in delivery of MTM services. A representative comment was “Do all pharmacists receive that training now?” However, others spoke positively about their perceptions of pharmacists providing MTM services. One participant stated, “I think there’s a role for pharmacists, and actually looking at therapy options and perhaps suggesting something different.”

Theme 5: Experience with MTM

Participants reported a range of experiences with MTM. At one extreme, participants reported disregarding notifications that they were eligible for the service. A representative comment was “An e-mail that says: “We have determined that you are eligible” goes to the trash.” Other participants described their experiences with MTM services more positively. In 1 example, a participant mentioned that MTM services were something that happened in the hospital, while others recalled a series of telephone consultations with a nurse from the insurance company. Specifically, another participant described how the pharmacist identified a drug interaction with his/her medication. A representative comment was “Sometimes the pharmacist will say: “This medicine and that one don’t get along, let me call your physician and suggest something different.”

Theme 6: Reasons for Nonparticipation in MTM

Participants commented on factors that made them less likely to use MTM services. Some examples of reasons for nonparticipation included lacking awareness of their eligibility to receive MTM services, receiving too much information from their insurance company so they never read it, and being unsure of the identity or legitimacy of the telephone caller. Representative comments included the following: “If it’s six pages like I get with every prescription, absolutely what you’re doing is killing trees; nobody is going to read that” and “How do they know you’re not Joe Schmoe calling about some friend on the street?”

Theme 7: Preferred Method to Learn About MTM

Participants reported their preferred method for learning more about the MTM services, which included the Internet, e-mail, having information available at the physician’s office, or advertisements on television or as a mass media campaign. Representative comments included: “Can you have that available at the doctors’ office that you could pick up and take home with you?” and “Are they going to give information that we could access ourselves through the Internet?”

Discussion

This study, while limited in scope, addresses the larger global challenge of helping patients effectively manage their chronic diseases and medications. Previous research indicates that MTM programs offered through Medicare Part D have existed for more than a decade, yet the public is still poorly informed of this benefit, and adoption of these services remains low.14 Participants in our study were also uninformed about what MTM involves and how they might benefit from it. Consequently, it is plausible that they might refuse MTM when offered. Clearly, further investigation is warranted to explore all of the reasons why individuals opt out of MTM services.

Some participants recognized, as a result of attending 1 of these focus group sessions, that they had been previously offered MTM services. Additionally, most participants said they would accept and use MTM services if offered to them in the future, now that they better understood the benefits. Thus, it is feasible that public education efforts regarding MTM might help shift patients’ understanding and subsequent acceptance and use of these services. Yet, bridging the health communication gap for vulnerable populations (e.g., seniors, Medicaid patients) is challenging.18 It is essential to engage patients and other stakeholders (e.g., advisory panel of experts) in a collaborative process to develop and evaluate appropriate (e.g., age, gender, culture, health literacy level)18,19 or patient-centered messaging20 to gain a better understanding of patients’ perspectives, potential barriers, and receptiveness to new information (i.e., MTM services)21 to facilitate dissemination. Equally important is for health care providers (e.g., prescribers, pharmacists) and public health educators to use terms that are meaningful to patients when describing MTM services. Patients in this study suggested terms such as “personalized medication services” or “multiple medication management” since they did not understand how the term “therapy” applied to medications. It is also important to integrate engagement strategies to help patients replace former behavior (e.g., nonparticipation in MTM) with a new, more desirable one (e.g., use of MTM) to promote acceptance and use of these services.21 Participants recommended the following communication channels to improve public MTM awareness: mass media campaigns, educational brochures, the Internet, computers, full-page newspaper advertisements, mass Medicare mailing, information offered by patient’s health care provider or pharmacist, and booths at annual health fairs.

Participants also lacked understanding of pharmacists’ training and their role in helping patients manage medications as part of MTM. These observations parallel other research findings that indicate the general public typically associates pharmacists with dispensing roles.22,23 However, a key component of MTM is service provision, separate from medication dispensing.24 While the pharmacists’ role on the interprofessional health care team is becoming more well recognized among health care professionals,25 it is evident that this information has not reached the lay public. Research shows that patients are more likely to participate in MTM services (i.e., have a comprehensive medication review) if they know that the pharmacist is collaborating with their prescribers.26 Thus, pharmacists should help patients better understand why these services are important and the pharmacist’s role in service provision. In fact, the authors believe that the pharmacy profession should engage in a nationwide advertising campaign about pharmacists’ training, abilities, and role in service provision to begin to shift the cultural perception that pharmacists just count pills.

Limitations

This project has several limitations. First, it used a cross-sectional design, which relies on providing data for a single point in time rather than over time. Therefore, it is impossible to determine whether perceptions of the participants and use of MTM services were maintained or diminished over time. Second, this project used a qualitative method (e.g., self-reported information in a group setting) to capture participants’ perceptions about and use of MTM services. Bias inherent to qualitative methods (e.g., participant self-selection, participant-social desirability response) may have occurred; however, the researchers took multiple measures (e.g., standardized focus group procedures and questions, confidentiality and anonymity of participant responses) to reduce potential bias. Third, the views of the focus group participants may not represent those of the broader patient population eligible for MTM services. Finally, the focus group sessions were only conducted in 1 geographic region and are not necessarily representative of the general population with regard to sociodemographic factors (e.g., education, employment status, health insurance status).

Conclusions

The results from this project suggest that the lay public remains unaware of this service and that the term “MTM” is not well understood. Thus, public health professionals, prescribers, pharmacists, and MTM program providers face multiple challenges in closing the gap in use of MTM services. It is critical that professionals appropriately describe MTM to help patients better understand this service, its benefits, and the pharmacist’s role in helping them manage their chronic diseases and medications. Finally, these results provide the foundation and important insight to facilitate development of strategies to promote MTM and engage the lay public in using these services.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: fact sheet . June 1, 2018. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The power of prevention: chronic disease…the public health challenge of the 21st century . 2009. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/2009-power-of-prevention.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 3.Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple chronic conditions chartbook: 2010 medical expenditure panel survey data. 2014. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/decision/mcc/mccchartbook.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 4.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Avoidable costs in U.S. healthcare: the $200 billion opportunity from using medicines more responsibly . June 2013. Available at: http://offers.premierinc.com/rs/381-NBB-525/images/Avoidable_Costs_in%20_US_Healthcare-IHII_ AvoidableCosts_2013%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2018.

- 5.American Pharmacists Association. Medication therapy management digest: pharmacists emerging as interdisciplinary health care team members . 2013. Available at: https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/MTMDigest_2013.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 6.American Pharmacists Association. Medication therapy management services . 2018. Available at: http://www.pharmacist.com/medication-therapy-management-services. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 7.U.S. Government Publishing Office. Public Law 108-173 - Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 . 2003. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-108publ173/content-detail.html. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2010 Medicare Part D medication therapy management (MTM) programs (fact sheet) . 2010. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/MTMFactSheet_2010_06-2010_ final.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 9.Iyer R, Coderre P, McKelvey T, et al. An employer-based, pharmacist intervention model for patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(4):312-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal A, Babbott S, Wilkinson ST. Can the targeted use of a discharge pharmacist significantly decrease 30-day readmissions? Hosp Pharm. 2013;48(5):380-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett MJ, Frank J, Wehring H, et al. Analysis of pharmacist-provided medication therapy management (MTM) services in community pharmacies over 7 years. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(1):18-31. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(2):203-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittayanukorn S, Westrick SC, Hansen RA, et al. Evaluation of medication therapy management services for patients with cardiovascular disease in a self-insured employer health plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(5):385-95. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson CF. Few Medicare beneficiaries receive comprehensive medication review services. 2014. Available at: http://avalere.com/expertise/managed-care/insights/few-medicare-beneficiaries-receive-comprehensive-medication-management-serv. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 15.Law AV, Okamoto MP, Brock K. Perceptions of Medicare Part D enrollees about pharmacists and their role as providers of medication therapy management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(5):648-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truong HA, Layson-Wolf C, de Bittner MR, Owen JA, Haupt S. Perceptions of patients on Medicare Part D medication therapy management services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(3):392–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock ME, Amankwaa L, Revell MA, Mueller D. Focus group data saturation: a new approach to data analysis. The Qualitative Report. 2016;21(11):2124-30. Available at: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss11/13. Accessed June 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhauser L, Rothschild B, Graham C, Ivey SL, Konishi S. Participatory design of mass health communication in three languages for seniors and people with disabilities on Medicaid. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2188-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koops van ‘t Jagt R, de Winter AF, Reijneveld SA, et al. Development of a communication intervention for older adults with limited health literacy: photo stories to support doctor–patient communication. J Health Commun. 2016;21(Suppl 2):69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Joint Commission. “What did the doctor say?” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety (Report) . 2007. Available at: https://www. jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/improving_health_literacy.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 21.Snyder LB, Hamilton MA, Mitchell EW, Kiwanuka-Tondo J, Fleming-Milici F, Proctor D. A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. J Health Commun. 2004;9(Suppl 1):71-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schommer JC, Gaither CA. A segmentation analysis for pharmacists’ and patients’ views of pharmacists’ roles. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(3):508-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown LM., Rashrash ME, Schommer JC. The certainty in consumers’ willingness to accept pharmacist-provided medication therapy management services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(2):211-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ai AL, Carretta H, Beitsch LM, Watson L, Munn J, Mehriary S. Medication therapy management programs: promises and pitfalls. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(12):1162-82. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.12.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avalere Health. Exploring pharmacists’ role in a changing healthcare environment . May 21, 2014. Available at: http://avalere.com/expertise/life-sciences/insights/exploring-pharmacists-role-in-a-changing-healthcare-environment. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 26.Duocette WR, Zhang Y, Chrischilles EA, et al. Factors affecting Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ decision to receive comprehensive medication reviews. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(5):482-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]