Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Preapproval information exchange (PIE) is the communication of clinical and health care economic information (HCEI) on therapies in development between U.S. population health decision makers (PHDMs) and drug manufacturers before regulatory approval. Early access to HCEI can help PHDMs plan budgets, inform formulary coverage decisions, and accelerate policy development to improve patient access to innovative health technologies. While recent FDA guidelines and proposed legislation aim to clarify definitions and execution of PIE, the level of U.S. PHDMs’ awareness and preferences for early engagement with investigational therapies is unclear.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) assess U.S. PHDMs’ current knowledge and perceptions of PIE and (b) identify their preferences for PIE, in order to shape future development of related guidelines and policy.

METHODS:

An expert panel of 5 U.S. PHDMs representing national and regional payers from integrated health plans, pharmacy benefit management, and specialty pharmacy organizations participated in a 2-round modified Delphi process. A targeted literature review of PIE was used to develop a web-based survey administered to the panel. Survey responses were grouped by consensus, with ≥ 80% agreement or disagreement as the threshold in round 1. In round 2, content experts moderated an inperson meeting where panelists deliberated and then revoted on round 1 nonconsensus topics.

RESULTS:

In the round 1 survey, the panelists reached consensus on 35 of 54 (65%) multiple-choice questions. In the round 2 face-to-face discussion, 19 nonconsensus questions were debated. One question was removed due to duplication, and consensus was achieved on 16 additional questions, with 2 items of nonconsensus remaining. Overall, consensus was achieved on 51 of 53 topics (96%). There was full consensus by the panelists that PIE should encompass new molecular entities and new indications of marketed therapies. Panelists completely agreed on the need for a legislative “safe harbor” for PIE. Four of five panelists reported that the value of PIE was high to PHDMs, and they expressed a strong preference for peer-to-peer conversations with manufacturers’ medical or outcomes liaisons for PIE. The main topic of nonconsensus was the optimal timing of PIE.

CONCLUSIONS:

This panel of U.S. PHDMs achieved consensus on the value of PIE to proactively budget, make informed formulary decisions, and develop pharmaceutical policy to facilitate patient access to new therapies. The PHDM panel’s preferences for PIE should be considered in legislative discussions and planning for future PIE by PHDMs and manufacturers. The full contribution of PIE to improving the U.S. health system can best be realized under a safe harbor that allows U.S. PHDM and manufacturer experts to engage in robust scientific and economic discourse. Additional research and broad stakeholder engagement is needed to advance the development of formal U.S. PIE guidelines.

What is already known about this subject

In the current environment, the majority of information exchange between U.S. population health decision makers (PHDMs) and manufacturers on new therapies occurs after approval, which delays the formulary decision process and affects patient access to drugs.

The AMCP Partnership Forum has established that early access and exchange of clinical and health care economic information between PHDMs and industry is supportive of accelerating the formulary decision process.

Existing legislation and regulations permit the exchange of some types of clinical information and health care economic information between manufacturers and PHDMs before FDA approval; however, ambiguity has increased uncertainty and inconsistent information-sharing practices across stakeholders.

What this study adds

A panel of experts from the PHDM community agreed that PIE has value and is needed to support efficiency and timeliness in planning budgets and formulary design when discussions include (a) new technologies and new indications for approved technologies, (b) peer-to-peer conversations with manufacturers’ medical or outcomes liaisons, and (c) proposed marketing and financial information from the manufacturer account management team.

The PHDM panelists held high expectations for financial information as a critical component of PIE, including disclosure of the projected wholesale acquisition cost price and price shift assumptions (listed and justified) that could be affected by a set of defined variables.

PHDMs cited 3 key drivers for prioritizing PIE discussions: (a) size of target patient population, (b) magnitude of the new budget impact, and (c) expected speed of regulatory approval.

As the U.S. health care system pivots from volume to value, U.S. population health decision makers (PHDMs), such as payers and health plans, have increasingly expressed a need for clinical and health economic information on pharmaceuticals before U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. In 1997, Congress passed the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA), which included Section 114 authorizing the communication of “health care economic information” (HCEI) generally between manufacturers and “a formulary committee or similar entity,” as long as the information “directly related to an approved indication” and was based on “competent and reliable scientific evidence.”1 The law was intended to offer manufacturers and PHDMs a “safe harbor” under which manufacturers and PHDMs could proactively discuss HCEI without fear of legal repercussions, provided that they do not violate the rules set out in the law.2 However, the wording in Section 114 is vague and open to interpretation, leaving manufacturers and PHDMs uncertain about the types of information that could be legally shared, the timing of information sharing, and the appropriate participants.

This need for information exchange is especially acute in the context of accelerated, targeted, or innovative therapies for which the FDA has created expedited approval pathways.3 Early access to clinical and health economic information before FDA approval can allow PHDMs to incorporate information on drugs in development or expanded indications of existing drugs into budgeting, formulary design, and patient access decisions.4 In addition, PHDMs can anticipate the incorporation of such information into guidelines versus current standard of care, thereby ensuring patient access at the time of regulatory approval.

In 2016, an Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Partnership Forum was held to address these issues and make recommendations to Congress and the FDA. The forum’s recommendations included clarification that preapproval information exchange (PIE) is intended as a bidirectional exchange between manufacturers and PHDMs, a request that the FDA and Congress provide a safe harbor allowing discussion of HCEI with PHDMs 12-18 months in advance of product approval to allow for budgeting and planning, and the provision of information to patients to support personal health care decisions.4

At the end of 2016, section 3037 of the 21st Century Cures Act amended FDAMA Section 114, seeking to clarify language and add flexibility on how to interpret the legality of HCEI exchanges. Section 3037 defined HCEI and sought to increase the transparency of health economic methodology and expand the audience for HCEI beyond formulary committees.5 In early 2017, the FDA issued a highly anticipated draft guidance clarifying some aspects but again leaving room for interpretation of others.6

On April 6, 2017, HR 2026, the Pharmaceutical Information Exchange Act was introduced into Congress by Representative Bret Guthrie.7 However, support for HR 2026 has not been universal. In a letter dated June 5, 2017, to the Energy and Commerce Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, a group of organizations, including Public Citizen, voiced opposition to HR 2026.8 These organizations expressed concerns that HR 2026 may promote off-label use of drugs and may disincentivize manufacturers from producing clinical data after launch if PHDMs accept the early outcomes and modeling information to make coverage decisions.

As new legislation and policies are under consideration, there is an urgent need to assess their potential effects and to recommend ways to operationalize PIE with appropriate safeguards to ensure that such information reaches intended entities, namely PHDMs.

There is a lack of research exploring U.S. PHDM perspectives regarding PIE to further its dialogue, development, and refinement. To this end, an expert panel of PHDMs convened to clarify definitions of PIE, assess current PIE processes between PHDMs and manufacturers, and identify U.S. PHDM preferences for future preapproval communication with manufacturers.

Methods

A study plan was developed to outline key steps in the research protocol. A list of 31 U.S. PHDM thought leaders was assembled, based on previous participation in health policy panels, publications, and projects. From that list, 5 PHDMs were recruited for an expert panel to ensure representation from different types of payer organizations (e.g., integrated health plans, pharmacy benefit management, and specialty pharmacy organizations); geographic regions; and availability. A targeted literature search identified relevant publications describing PIE, policy consensus development, and the modified Delphi method (an organized method for collecting views and information).4,9-11

A modified Delphi method consisting of 2 rounds was used to gather and analyze the data for this project. Round 1 was an online survey developed by investigators and content experts. The survey collected anonymous opinions from the 5 PHDM experts in November 2017. The literature suggests that a suitable minimum sample size is 7, but sample sizes as small as 4 have been used; that the decision regarding the number of panelists is empirical and pragmatic and takes into consideration time and expense; and that representation should be assessed more by the quality of the participants rather than the number.12-16

The questions in the survey were organized into 4 core domains: (1) definition of PIE, (2) value of PIE, (3) current utility of PIE, and (4) future improvement of PIE. The survey consisted of 54 multiple-choice and 7 open-ended questions (Table 1). The possible responses for 51 multiple-choice questions were strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree. The remaining 3 multiple-choice questions had answers based on a time frame. Each multiple-choice question contained a free-text box for respondents to provide rationales for their answers.

TABLE 1.

Round 1 Online Survey Questions

| Question Number | Question |

|---|---|

| Q1 | PIE stands for “preapproval information exchange.” |

| Q2 | On balance, PIE is most helpful to manufacturers. PIE would be most advantageous to manufacturers. |

| Q3 | PIE is intended to provide information to PHDMs on new molecular entities approaching NDA submission, or new indications being submitted for approval. |

| Q4 | PIE can provide health economic information, enabling value-based decision making by PHDMs. |

| Q5 | There is a need for a “safe harbor” for PIE dissemination. |

| Q6 | PIE may include budget impact and comparative effectiveness models as evidence. |

| Q7 | PIE allows for 2-way dialogue between PHDMs and manufacturers, including relevant clinical and economic outcomes for their populations. |

| Q8 | Our organization feels PIE benefits manufacturers more than it helps PHDMs. |

| Q9 | A PIE discussion between PHDMs and industry is important. |

| Q10 | Recognizing that NDA filing may occur up to a year before FDA approval, the most appropriate time for PIE before filing is: 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months. |

| Q11 | The most appropriate time frame for PIE before PDUFA date is: 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months. |

| Q12 | The primary audience for PIE is PHDMs at risk for the cost of providing access to health care for populations. |

| Q13 | On balance, among PIE recipients, PIE would be most advantageous to PHDMs. |

| Q14 | By helping PHDMs optimize formulary forecasting and rates, PIE provides improved patient management. |

| Q15 | PIE provides the ability to more accurately forecast health plan budgets to adjust premiums. |

| Q16 | PIE should be disseminated only to PHDMs. |

| Q17 | PIE should be disseminated to practicing physicians. |

| Q18 | PIE evidence requires a statistical comparison.a |

| Q19 | PIE would offer information on disease prevalence and member impact on health plans for formulary planning. |

| Q20 | PIE is nothing new. We already follow drugs in the pipeline and use the data for budget forecasting. |

| Q21 | PIE is needed for orphan drugs where there is limited data available at launch. |

| Q22 | PIE is NOT intended to promote off-label use of currently approved indications. |

| Q23 | The current research (i.e., horizon scanning) conducted by our organization provides the PIE we need for decision making. |

| Q24 | PIE is important for PHDMs for planning benefit design in the near term.a |

| Q25 | PIE on pipeline products is supportive for anticipating Medicare Part D coverage decisions. |

| Q26 | The value of PIE to our organization is high. |

| Q27 | Currently, our organization conducts PIE on the following schedule: monthly, quarterly, semiannually, annually. |

| Q28 | Information presented in PIE is perceived by my plans as reliable, similar to expectations for information provided under FDAMA Section 114. |

| Q29 | PIE should be restricted to new molecular entities only, with no prior approvals. |

| Q30 | Unsolicited requests for preapproval information from our organization provides sufficient information we need from manufacturers. |

| Q31 | PIE on a new indication of an approved product risks being considered off-label promotion. |

| Q32 | There are gaps between what preapproval information is currently available via preapproval unsolicited requests and what PHDMs need. |

| Q33 | In the future, I believe PIE will help improve PHDMs’ formulary decision making. |

| Q34 | PIE will address unmet informational needs for PHDMs. |

| Q35 | I anticipate that the future value of PIE as proposed will be high for our organization. |

| Q36 | PIE could anticipate future adherence/compliance considerations for investigational products. |

| Q37 | PIE can provide burden of illness data on investigational products. |

| Q38 | PIE can inform budget impact models on investigational products. |

| Q39 | Including prescribing physicians as recipients of PIE will promote off-label use and will increase the misperceptions of PIE. |

| Q40 | Manufacturer communication on products before approval including product information, approval timing, pricing, phasing, and targeting/marketing strategies should be within the scope of PIE. |

| Q41 | It is important to my plan that data on new uses for approved products is available as PIE. |

| Q42 | The appropriate choice of who presents PIE information would depend on what data are being presented. |

| Q43 | I prefer to receive clinical PIE information from the manufacturer’s medical organization (e.g., medical affairs representatives, health outcomes liaisons, managed care liaisons). |

| Q44 | I prefer to receive clinical PIE information from the manufacturer account management team. |

| Q45 | I prefer to receive clinical PIE information from the organization’s brand marketing/market access representatives. |

| Q46 | I prefer to receive health economic PIE information from the manufacturer’s medical organization (e.g., medical affairs representatives, health outcomes liaisons, managed care liaisons). |

| Q47 | I prefer to receive health economic PIE information from the manufacturer’s account management team. |

| Q48 | I prefer to receive health economic PIE information from the manufacturer’s brand marketing/market access representatives. |

| Q49 | I prefer to receive forecasting and marketing materials of PIE information from the manufacturer’s medical organization. |

| Q50 | PIE is of greater value for drugs that receive FDA breakthrough designation. |

| Q51 | PIE as proposed includes scientific and health economic information. I anticipate PIE as proposed will help address my organization’s needs. |

| Q52 | PIE should inform comparative effectiveness models on investigational products. |

| Q53 | Product information, approval timing, pricing, and targeting/marketing strategies are components of PIE information that would be useful to my plan. |

| Q54 | I prefer to receive forecasting and marketing materials of PIE information from the manufacturer’s account management or marketing team. |

| Q55 | Open-ended: PIE has been described as “preapproval information exchange” or “pharmaceutical information exchange.” Which do you think best describes PIE and why? |

| Q56 | Open-ended: From your perspective, what is your definition of PIE? |

| Q57 | Open-ended: What are the gaps between what is allowed by PIE and what payers need? |

| Q58 | Open-ended: What are your current unmet needs and challenges to effective forecasting? |

| Q59 | Open-ended: What is most valuable to you and your organization from PIE? |

| Q60 | Open-ended: In your view, why does your organization need to conduct PIE? |

| Q61 | Open-ended: If your organization is not conducting PIE, what discussions are you currently having that contribute to forecasting? |

aIn round 2, question #18 was omitted due to duplication, and question #24 was revised from “benefit design” to “formulary design” for clarity.

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; FDAMA = Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act; NDA = new drug application; PDUFA = Prescription Drug User Fee Act; PHDM = population health decision maker; PIE = preapproval information exchange.

Results from the survey were tabulated, and consensus was evaluated by grouping the responses into 2 dichotomous categories: agree and disagree. Consensus on agreement was defined as at least 4 answers of agree or strongly agree, and disagreement consisted of at least 4 answers of disagree or strongly disagree. Questions with ≥ 80% agreement or disagreement were considered to have reached consensus and were complete. Questions with < 80% agreement or disagreement were considered not in consensus. A summary of the anonymous responses to the survey was provided to all participants before round 2.

The second round consisted of an in-person panel discussion with respondents in December 2017. The in-person discussion reviewed the survey responses, focusing deliberations on questions for which consensus was not met. The 7 open-ended questions helped guide the discussion during the in-person meeting, which focused on clarification of the definitions and panelists’ interpretation of the wording used in some of the questions. In this meeting, respondents were required to resubmit their answers to the multiple-choice questions that had not achieved consensus in the first round, with their new responses based on the facilitated discussions with the other panel members. Voting in this round was done by paper ballots. Again, ≥ 80% was required to achieve consensus on agreement or disagreement. After voting for each domain was completed, the content expert (author Neumann) provided commentary and summarized the discussion. Following the meeting, an anonymized summary report of the panel discussions was produced.

Results

Five U.S. PHDMs participated in this study. They represented national and regional PHDMs from integrated health plans, pharmacy benefit management, and specialty pharmacy organizations that provided medical and/or pharmaceutical benefit coverage.

All panelists completed the round 1 web-based survey. Consensus was reached on 35 of 54 multiple-choice questions (65%). Across the 4 core survey domains, PHDMs expressed strongest consensus in core domain 3 (current utility of PIE) and core domain 4 (future improvement of PIE). The 19 non-consensus questions identified in round 1 were predominately from core domain 1 (definition of PIE) and core domain 2 (value of PIE). These were carried forward as questions for the round 2 in-person workshop phase of the modified Delphi process. In-person deliberation of nonconsensus questions resulted in the removal of 1 question due to duplication. In addition, PHDM discussion resulted in the revision of the wording in question 24, changing “benefit design” to “formulary design” for clarity. Further consensus was achieved on 16 questions in round 2. Overall, after both rounds of the process, consensus was achieved on 51 of 53 questions (96%; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of PHDM Responses to Survey Questions After Both Rounds of Voting

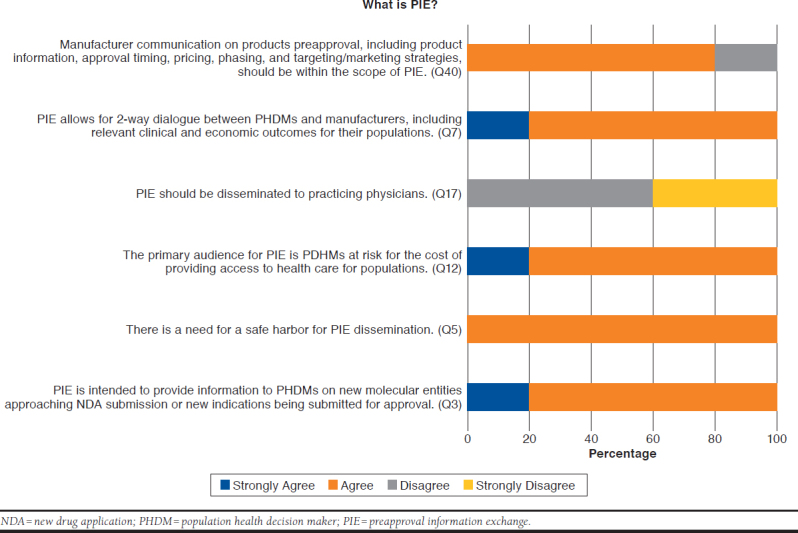

Figure 2 shows key points that panelists highlighted regarding the definition and utility of PIE. All panelists reported knowledge of PIE as an exchange of HCEI between PHDMs and manufacturers and reported various PIE experiences to date. There was full agreement that PIE is needed in the United States and that it should apply to new molecular entities and new indications of marketed therapies. All panelists agreed that PIE should encompass HCEI and detailed pricing projections, and panelists were unanimous in their call for a legislative safe harbor to facilitate transparent PIE discussions. Panelists reported broad consensus for peer-to-peer PIE conversations to ensure that appropriately skilled participants from PHDMs and manufacturers are engaged in the discussion. Most panelists indicated that PIE would not be most advantageous or helpful for manufacturers, but rather most advantageous and beneficial for PHDMs. There was 100% agreement that PIE was not intended for prescribing practitioners and that PIE should not be disseminated to practicing physicians.

FIGURE 2.

Views of Key Panelists on Definition and Scope of PIE

Figure 3 highlights key points from panelists regarding what they perceived as the value of and need for PIE. For the majority of panelists, the perceived value of PIE was high and thought to be important in helping PHDMs optimize formulary forecasting and rates, thereby improving patient management. Key value drivers of PIE were data maturity and the transparency of the investigational products’ HCEI, especially for therapies designed to treat conditions with high unmet need and high prevalence. One dissenting opinion on the value of PIE expressed skepticism that it would ultimately help reduce health care costs. All expert panelists agreed that PIE can address unmet informational needs for PHDMs. The majority of panelists agreed that PIE was not intended to promote off-label use of medications for indications not currently approved.

FIGURE 3.

Perceptions of Key Panelists on Value of and Need for PIE

Areas of nonconsensus included the optimal timing of PIE (Table 2). Other areas of concern raised by the expert panelists were the potential misperceptions of off-label promotion if PIE involved a new indication for a marketed product, the logistics of enforcing PIE policy, and the need for wider public education regarding appropriate context and scope of PIE discussions.

TABLE 2.

Questions of Nonconsensusa

| Question | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months | |

| Recognizing that an NDA filing may occur up to a year before FDA approval, the most appropriate time for PIE before filing is: | 60% | 0% | 40% | 0% | 40% | 20% | 40% | 0% |

| The most appropriate time frame for PIE before PDUFA date is: | 0% | 40% | 40% | 20% | 0% | 20% | 40% | 40% |

aReflects questions in which consensus was not achieved after both rounds of the Delphi process.

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NDA = new drug application; PDUFA = Prescription Drug User Fee Act; PIE = preapproval information exchange.

Discussion

The reality for most U.S. health plans is that budgets, formularies, and patient access decisions are typically being made 12-18 months before a new plan year begins. These forecasting and policy-setting activities are largely driven by Medicare Part D regulations. But the effect of these decisions may be broad because PHDMs are often responsible for public and private plan subscribers. In most cases, PHDMs are handicapped by information asymmetries when making outcomes and economic projections regarding drugs in development or drugs with expanded indications. Information gaps include those related to epidemiological and disease-specific characteristics, financial information, and rates of clinical and economic outcomes. The increased focus on value-based contracts also requires PIE to develop contracting scenarios that are ready to implement upon product launch. A lack of preapproval information can impede the proactive development of pharmaceutical policies, hindering expedient patient access to new innovations. Early information can also help assess potential product placement in future updates to guidelines versus current standards of care, as supported by published literature. The unpublished data presented through PIE will largely be related to pharmacoeconomics, modeling, and cost information.

Although these assumptions have been largely promulgated through proactive dialogue,4 consensus on the value of preapproval information across payer types and how such information exchange would be operationalized remains largely unknown. Our panel explored these critical areas through a modified Delphi process, which allowed for an initial reaction via an online survey and then the opportunity for in-person dialogue and exchange regarding areas of nonconsensus.

Previous independent surveys have evaluated the use and value of FDAMA Section 114. For example, in a 2013 study, U.S. health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) leaders for drug and device companies were surveyed to examine their views on the state of the field.17 Approximately 62% agreed that AMCP dossiers were useful to U.S. health plans, and 55% stated that FDAMA Section 114 was useful. These findings suggest strong recognition of the value of HEOR capabilities and communication at senior management levels and optimism about the field.17

We saw a similar sentiment in our initial survey results, with great interest in PIE and support of a framework to facilitate dissemination. Respondents stated that PIE engagement around clinical data and HCEI was specifically desired from manufacturer medical and scientific representatives (i.e., medical or outcomes liaisons) as opposed to commercial representatives.

Previous surveys queried respondents about the interpretation of FDAMA Section 114, exploring the FDA’s role in the information exchange.18 Similarly, our survey revealed a strong interest in a safe harbor that would allow for exchange to occur, as well as the need for oversight of these exchanges.

Finally, a panel of experts, similar to our Delphi panel round 2, was convened to debate the quality assessment of real-world data for decision making by health plans. The need for standardization of information exchange processes across health plans and decision makers was a significant point of consensus.19

In our combined approach, the value of PIE and the need for a legislative safe harbor for PIE was clearly identified. Considerations of the current PIE process and the future optimization of PIE benefited from the in-person discussion. The PHDM panelists held high expectations for financial information as a critical component of PIE, including disclosure of the projected wholesale acquisition cost price and pricing assumptions (listed and justified) that could be affected by a set of defined variables. PHDMs articulated a strong preference for simple sensitivity analyses, such as price bands, with full acknowledgement of inherent uncertainties before approval and commercialization.

An important lesson from the panel discussion was that not all new drugs will merit PIE discussions. The value of PIE will likely vary among drugs, depending on the size of the affected population, the drug’s cost and economic impact, and whether the new therapy will create new costs or simply shift costs in a crowded market. The value of PIE increases as a function of the prospective new budget impact. The budget impact of a new therapy for a large population may not be significant if payers are already providing multiple therapy options or if they have few of the affected population in their plans. Conversely, introducing a novel therapy for a small population at a high cost, or a new adjunctive therapy, could introduce a greater budget impact than the previous example increasing the value of PIE. When manufacturers plan a PIE discussion with PHDMs, they should consider the drug’s potential effect on relevant populations, overall new budget impact, price range projection, and the unmet needs in the indication as they decide on the level of PIE provided and the communication strategy of this information to the most relevant health plans.

One area of nonconsensus pertained to the optimal timing of PIE, which ranged from 3-12 months before FDA submission. While no consensus was achieved, panelists agreed that manufacturers should engage with PHDMs regarding investigational products with potential “high PIE value” earlier in this window. A related discussion focused on whether a new indication for an existing drug may be considered off-label promotion before launch. Without the enactment of a legislative safe harbor to discuss preapproval clinical and HCEI without fear of legal repercussions, panelists voiced concerns about the full utility of PIE.

On June 12, 2018, the FDA released a final guidance titled “Drug and Device Manufacturer Communications with Payors, Formulary Committees, and Similar Entities—Questions and Answers.”21 This guidance encompasses the agency’s guidelines on PIE requirements for manufacturers to discuss HCEI for unapproved products, as well as unapproved indications for existing products.21 The new guidance does not include a requirement for an intent to file but instead requires a statement that the product or indication has not been approved by the FDA and that the safety and effectiveness of the product or indication has not been established by the FDA. In addition, companies will be required to provide information on the stage of filing and any additional planned studies. While this guidance does not directly remedy the nonconsensus observed in this study pertaining to the optimal timing of PIE, compulsory disclosure of the product’s stage of filing and any additional planned studies may help PHDM audiences to plan and predict the expected product launch. Interestingly, the FDA guidance also covers health care economic communications related to medical devices, an area that was not discussed or considered in our Delphi panel approach.

The issue of safe harbor was not addressed by the recent FDA guidance, which reaffirms the need for legislative solutions such as HR 2026. Notably, a similar concern regarding off-label promotion was highlighted by the 2017 Public Citizen et al. letter to Congress in opposition to HR 2026.8 A key difference, however, is recognition by the PHDM panelists that PIE is communication between manufacturers and PHDMs, not between manufacturers and prescribers. This confusion among public policy stakeholders about the intended PIE audience and participants—PHDMs and manufacturers—highlights the need for a formal framework to standardize PIE.

A final point of legislative consideration was enforcement of PIE. Presumably the FDA would be responsible for codifying HR 2026 with respect to monitoring and enforcing adherence. We recommend broad stakeholder input (patients, PHDMs, and manufacturers) for the development of PIE regulations to ensure full transparency.

Limitations

While making important steps towards defining and preparing for new regulations on PIE, this study has limitations. First, the panel consisted of a small number of PHDMs who may not adequately represent the broader U.S. PHDM population. Second, while the combination of an anonymous web-based survey and a face-to-face meeting to discuss areas with less than 80% consensus was beneficial, a limitation was that a 2-step modified Delphi process was used. Multiple iterations of data gathering and syntheses have been previously recommended for full Delphi processes.20

Conclusions

A panel of 5 national and regional U.S. PHDMs agreed that PIE is valuable, needed, and should apply to new molecular entities and new indications of marketed therapies. This sample of U.S. PHDMs desired PIE with manufacturers as peer-to-peer discussions between appropriate experts encompassing clinical, scientific, health economic, and financial information. PIE aligns with PHDM goals of reducing uncertainty and risk exposure while improving forecasting. PHDMs were uncertain whether PIE would reduce overall costs; however, there was agreement that PIE supports ongoing efforts to manage health care costs.

Incorporation of these PHDM perspectives on PIE into ongoing legislative discussions and planning for future PIE by PHDMs and manufacturers is warranted. U.S. PHDMs unanimously agree that a legislation solution for PIE is required, since the full contribution of PIE to improving the U.S. health system can best be realized under a safe harbor that allows U.S. PHDMs and manufacturer experts to engage in robust scientific and economic discourse. Legislative action must allow for the proactive exchange of HECI before FDA filing and between manufacturers and PHDMs of payer organizations, formulary or technology review committees, and other such entities with expertise and responsibility for formulary coverage decisions or population health care management. Enacted legislation must also require that information exchange be truthful, not misleading, and based on competent and reliable scientific evidence related to the investigational product or investigational use of a drug or device. The appropriate allowance of PIE between professional peers based on reliable evidence is intended to address unmet informational needs, support efficient timing of PHDM review, and decrease uncertainty, aligning towards a common goal—improving our health care delivery system in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following panelists for their participation in this project: Steven G. Avey, MS, RPh, FAMCP, Vice President, Enterprise Specialty Clinical Solutions, Medimpact; Douglas S. Burgoyne, BSPharm, PharmD, FAMCP, President, VRx Pharmacy Services; H. Eric Cannon, PharmD, FAMCP, Assistant Vice President, Pharmacy Benefits, Select Health; Stanley E. Ferrell, RPh, BSPharm, MBA, Senior Director, Clinical Account Management, Express Scripts; and John Leonard Fox, MD, Associate Chief Medical Officer, Priority Health. The authors also thank medical writer Kelley J. P. Lindberg, of Blue Raven Services, for her editing and formatting assistance with this article. Funding for her services was provided by Millcreek Outcomes Group.

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 . Pub L 105-115, 111 Stat 2296. November 21, 1997. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-105publ115/pdf/PLAW-105publ115.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 2.AMCP Partnership Forum : FDAMA Section 114—improving the exchange of health care economic data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(7):826-31. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.7.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Fast track, breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, priority review. November 28, 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/approvals/fast/ucm20041766.htm. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 4.AMCP Partnership Forum : Enabling the exchange of clinical and economic information pre-FDA approval. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(1):105-12. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.16366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.21st Century Cures Act . Pub L 114-255,130 Stat 1033. December 13, 2016. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ255/PLAW-114publ255.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Drug and device manufacturer communications with payors, formulary committees, and similar entities—questions and answers; draft guidance for industry and review staff. Notice of availability. Docket No. FDA-2016-D-1307. January 19, 2017. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/19/2017-01011/drug-and-device-manufacturer-communications-with-payors-formulary-committees-and-similar. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 7.Pharmaceutical Information Exchange Act. HR 2016, 115th Cong, 1st Sess. (2017). Available at: https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr2026/BILLS-115hr2026ih.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 8.Public Citizen, Annie Appleseed Project, Association for Medical Ethics, et al. Letter to members of the U.S. House of Representatives, Energy and Commerce Committee. June 5, 2017. Available at: https://www.citizen.org/sites/default/files/2371.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- 9.Eubank BH, Mohtadi NG, Lafave MR, et al. Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafson DH, Shukla RK, Delbecq A, Walster GW. A. comparative study of differences in subjective likelihood estimates made by individuals, interacting groups, Delphi groups, and nominal groups. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1973;9(2):280-91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thangaratinam S, Redman CWE. The Delphi technique. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;7:120-25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linstone HA. The Delphi technique. In Fowles J, ed. Handbook of Futures Research. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1978:271-300. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell C. Myths and realities of the Delphi technique. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(4):376-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann PJ, Saret CJ. A. survey of individuals in U.S.-based pharmaceutical industry HEOR departments: attitudes on policy topics. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(5):657-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann PJ, Lin PJ, Hughes TE. US FDA. Modernization Act, section 114: uses, opportunities and implications for comparative effectiveness research. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(8):687-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brixner DI, Holtorf AP, Neumann PJ, Malone DC, Watkins JB. Standardizing quality assessment of observational studies for decision making in health care. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(3):275-83. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yousuf M. Using experts’ opinions through Delphi technique. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2007;12(4):1-8. Available at: https://pare-online.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=4. Accessed November 19, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Drug and device manufacturer communications with payors, formulary committees, and similar entities—questions and answers: guidance for industry and review staff. June 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM537347.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.