This cross-sectional study examines data for Medicare beneficiaries who underwent elective, high-risk surgery in relation to a hospital market index to determine the association between market competition and surgical outcomes.

Key Points

Question

What is the association between hospital market competition and patient outcomes after high-risk surgery?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study involving 2 248 438 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent elective, high-risk surgery within high-competition vs low-competition hospital markets, there was no consistent association between degree of market competition and outcomes after surgery.

Meaning

Regulatory efforts to maintain hospital market competition may not achieve better postoperative outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Maintaining competition among hospitals is increasingly seen as important to achieving high-quality outcomes. Whether or not there is an association between hospital market competition and outcomes after high-risk surgery is unknown.

Objective

To evaluate whether there is an association between hospital market competition and outcomes after high-risk surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We performed a retrospective study of Medicare beneficiaries who received care in US hospitals. Participants were 65 years and older who electively underwent 1 of 10 high-risk surgical procedures from 2015 to 2018: carotid endarterectomy, mitral valve repair, open aortic aneurysm repair, lung resection, esophagectomy, pancreatectomy, rectal resection, hip replacement, knee replacement, and bariatric surgery. Hospitals were categorized into high-competition and low-competition markets based on the hospital market Herfindahl-Hirschman index. Comparisons of 30-day mortality and 30-day readmissions were risk-adjusted using a multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for patient factors (age, sex, comorbidities, and dual eligibility), year of procedure, and hospital characteristics (nurse ratio and teaching status). Data were analyzed from May 2022 to March 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Thirty-day postoperative mortality and readmissions.

Results

A total of 2 242 438 Medicare beneficiaries were included in the study. The mean (SD) age of the cohort was 74.1 (6.4) years, 1 328 946 were women (59.3%), and 913 492 were men (40.7%). When examined by procedure, compared with low-competition hospitals, high-competition market hospitals demonstrated higher 30-day mortality for 2 of 10 procedures (mitral valve repair: odds ratio [OR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.07-1.14; and carotid endarterectomy: OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.09) and no difference for 5 of 10 procedures (open aortic aneurysm repair, bariatric surgery, esophagectomy, knee replacement, and hip replacement; ranging from OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-1.00, for hip replacement to OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.94-1.26, for bariatric surgery). High-competition hospitals also demonstrated 30-day readmissions that were higher for 5 of 10 procedures (open aortic aneurysm repair, knee replacement, mitral valve repair, rectal resection, and carotid endarterectomy; ranging from OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02, for knee replacement to OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02-1.08, for rectal resection) and no difference for 3 procedures (bariatric surgery: OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.99-1.07; esophagectomy: OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.06; and pancreatectomy: OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99-1.01). Hospitals in high-competition compared with low-competition markets cared for patients who were older (mean [SD] age of 74.4 [6.6] years vs 74.0 [6.2] years, respectively; P < .001), were more likely to be racial and ethnic minority individuals (77 322/450 404 [17.3%] vs 23 328/444 900 [5.6%], respectively; P < .001), and had more comorbidities (≥2 Elixhauser comorbidities, 302 415/450 404 [67.1%] vs 284 355/444 900 [63.9%], respectively; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that hospital market competition was not consistently associated with improved outcomes after high-risk surgery. Efforts to maintain hospital market competition may not achieve better postoperative outcomes.

Introduction

Maintaining competition among hospitals is increasingly seen as important to achieving high-quality outcomes.1 While there is competition for many services provided by hospitals, high-risk elective surgery may be among the most affected by competition. Because these procedures are elective, patients have time to choose a location of care. Moreover, these specific operations also demonstrate rates of complications that vary based on the hospital where the procedure is performed.2

Whether or not hospital market competition is associated with outcomes after high-risk surgery is unknown. Prior assessments on medical conditions have demonstrated that hospital competition is associated with improved diabetes management and lower inpatient mortality for myocardial infarction.3,4 However, the impact of hospital market competition on surgical conditions is far less clear.5,6 For example, greater hospital competition was associated higher rates of inpatient mortality among patients undergoing kidney transplantation.7 In contrast, another study including only 20% of US hospitals identified multiple major surgical procedures where higher hospital competition was associated with lower mortality.8 The conflicting results of existing literature may be due to important limitations such as narrow selection of procedures or a limited sample of hospitals. As such, the relationship between hospital market competition and outcomes after surgery remains unclear.

In that context, we sought to evaluate how outcomes after high-risk surgery differed at hospitals in high- and low-competition markets in a nationally representative data set. We focused on a broad range of high-risk procedures with known high rates of complications that vary by location of care.2,9 We hypothesized that in a nationally representative claims database of these procedures, hospitals in high-competition markets would have better postoperative outcomes.

Methods

Data Sources

We obtained Medicare beneficiary claims data from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files (MEDPAR) between 2015 and 2018.10 This includes data on the beneficiaries’ index admission for a procedure as well as any subsequent hospitalization. Hospital characteristics were obtained from the Annual Survey of the American Hospital Association to obtain hospital characteristics.11 This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board and deemed exempt because it used secondary data. Data were analyzed from May 2022 to March 2023.

Hospital Market Competition Designation

To determine the market competition level of each hospital, we used the hospital market Herfindahl-Hirschman index.12,13 The hospital competition index assigns each hospital in the United States a value from 1000 to 10 000, with higher numbers indicating less hospital competition. The number is derived at the hospital level by squaring the market share of each hospital competing in the market and then summing the resulting numbers.11,12 Hospitals were categorized into high- and low-competition markets based on their hospital competition index value. Specifically, hospitals with a value of 2000 or lower were categorized as high competition and hospitals with a value between 8000 and 10 000 were categorized as low competition. We designated these thresholds to give us relatively even volumes of patient cohorts in both high- and low-competition groups. The hospital market Herfindahl-Hirschman index we used does not view other hospitals sites within the same hospital system as competitors.12,13 It also comprises data up to 2014, and our clinical data began in 2015.13 We made the assumption that during our study period (2015-2018), there were no significant changes in the index values because these market forces are fairly stable.

Identification of Procedures and Study Cohort

We selected elective procedures that could potentially be influenced by hospital market competition: specifically, procedures that are elective and that have known variation in outcomes based on the hospital where the procedure is performed.2,9 We excluded any patients who received these procedures under emergent or urgent conditions, to focus on elective procedures only.

We selected 10 procedures identified as elective and high-risk and that have variable outcomes across hospitals: carotid endarterectomy, mitral valve repair, open aortic aneurysm repair, lung resection, esophagectomy, pancreatectomy, rectal resection, hip replacement, knee replacement, and bariatric surgery.

Each cohort was identified using diagnosis-related group codes and procedure codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Manifestation.14 We then identified whether patients underwent their procedures at hospitals in high- or low-competition markets by linking the unique hospital identification number in MEDPAR with the respective hospital market Herfindahl-Hirschman index value.2,10

Outcome Variables

Our primary outcomes to compare surgical care at high-competition vs low-competition hospital markets were rates of 30-day mortality and 30-day readmissions.15,16,17 Thirty-day mortality was identified as death occurring within 30 days of the index operation. Mortality was determined 2 ways. First, in-hospital mortality was determined by vital status at the time of discharge. Second, the Medicare beneficiary denominator file was used to identify mortality occurring outside of the hospital within 30 days of the index operation.15 This method determined patients who died after discharge from their index admission or after transfer to another facility.

Thirty-day readmissions were defined as a claim for any hospital inpatient admission within 30 days after discharge of the index hospital stay, following a precedent in previous work using the MEDPAR file.3,10,15,18,19,20 Outcomes were evaluated for each individual procedure group.

Statistical Analysis

The first step of our analysis compared patient and hospital characteristics for high-competition and low-competition hospital markets. Patient characteristics included age, sex, race and ethnicity, preoperative comorbidities, admission type, distance and time traveled to the hospital for care, and postdischarge destination (eg, home, skilled nursing facility, transferred, hospice).14,21 Race and ethnicity data for Medicare beneficiaries were populated with data provided to the Social Security Administration using the categories Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native American, White, and other.22 Hospital characteristics were compared for high-competition and low-competition hospital markets, including ownership (for-profit and nonprofit), bed size, geography, teaching status, nurse ratio, surgical volume, and frequency of each of the 10 procedures. These comparisons were made using χ2 and Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

The second step of our analysis was to compare the rates of 30-day mortality and 30-day readmissions at high- vs low-competition hospitals. A multivariate logistical regression model was created for 30-day mortality and 30-readmissions as dependent variables. Our risk-adjustment models included multiple patient-level, operation-level, and hospital-level variables, including age, sex, comorbidities, dual eligibility status, year of procedure, nurse ratio, and teaching status. These risk-adjusted models were then used to calculate rates for the outcomes.

Finally, we tested multiple sensitivity analyses to better isolate the potential effect of hospital competition. Specifically, we repeated our above analysis after excluding rural hospitals, who often are the only source of care in their communities and are therefore less influenced by market competition. Additionally, we examined our outcomes stratified by patient complexity, as characterized by Elixhauser comorbidities, and travel distance. Lastly, we repeated our above analysis by insurance coverage, including patients who had Medicare Advantage. The findings of this analysis mirror those of the main analyses and are shown in eTables 1-4 in Supplement 1.

All reported P values were 2-sided, and a value less than .05 was used as the threshold for significance. All statistical analyses were completed with Stata version 17 (StataCorp).

Results

Our study cohort included 2 242 438 Medicare beneficiaries. The mean (SD) age was 74.1 (6.4) years, 1 328 946 were women (59.3%), and 913 492 were men (40.7%). Information about their comorbidities, procedures, and other characteristics is provided in Table 1.22 Among the 3166 hospitals in the cohort, 470 (14.8) were in high-competition markets and 1091 (34.5%) in low-competition markets.

Table 1. Patient-Level Characteristics Across High- and Low-Competition Hospital Markets.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | High competition | Low competition | P value | |

| No. of patients | 2 242 438 | 450 404 | 444 900 | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.1 (6.4) | 74.4 (6.6) | 74.0 (6.2) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 1 328 946 (59.3) | 269 872 (59.9) | 263 159 (59.2) | |

| Men | 913 492 (40.7) | 180 532 (40.1) | 181 741 (40.8) | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 18 960 (0.8) | 10 416 (2.3) | 1063 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Black | 136 107 (6.1) | 45 178 (10.0) | 17 440 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 23 476 (1.0) | 11 429 (2.5) | 2002 (0.4) | <.001 |

| Native American | 6688 (0.3) | 773 (0.2) | 2152 (0.5) | <.001 |

| White | 2 031 885 (90.6) | 372 309 (82.7) | 419 420 (94.3) | <.001 |

| Othera | 25 322 (1.1) | 10 299 (2.3) | 2823 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 1 601 376 (71.4) | 315 653 (70.1) | 317 973 (71.5) | <.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 198 171 (8.8) | 44 467 (9.9) | 33 106 (7.4) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 533 092 (23.8) | 106 087 (23.6) | 103 693 (23.3) | .006 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 410 841 (18.3) | 80 845 (17.9) | 78 015 (17.5) | <.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 422 833 (18.9) | 82 674 (18.4) | 81 476 (18.3) | .61 |

| Deficiency anemias | 210 332 (9.4) | 49 221 (10.9) | 37 392 (8.4) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 478 276 (21.3) | 96 992 (21.5) | 94 368 (21.2) | <.001 |

| Depression | 271 130 (12.1) | 48 672 (10.8) | 54 839 (12.3) | <.001 |

| Kidney failure | 231 052 (10.3) | 50 986 (11.3) | 39 297 (8.8) | <.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 116 993 (5.2) | 21 414 (4.8) | 24 117 (5.4) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 95 837 (4.3) | 18 482 (4.1) | 18 722 (4.2) | .01 |

| Weight loss | 25 127 (1.1) | 8033 (1.8) | 3151 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 145 991 (6.5) | 36 660 (8.1) | 23 697 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 22 123 (1.0) | 7259 (1.6) | 2700 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Valvular disease | 106 699 (4.8) | 22 657 (5.0) | 20 871 (4.7) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 33 615 (1.5) | 9076 (2.0) | 5232 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 95 145 (4.2) | 18 478 (4.1) | 19 441 (4.4) | <.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 66 100 (2.9) | 17 535 (3.9) | 9455 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Solid tumor | 24 709 (1.1) | 6175 (1.4) | 4024 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Psychoses | 24 935 (1.1) | 6137 (1.4) | 4153 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 229 916 (10.3) | 44 463 (9.9) | 50 717 (11.4) | <.001 |

| 1 | 530 302 (23.6) | 103 526 (23.0) | 109 828 (24.7) | <.001 |

| ≥2 | 1 482 220 (66.1) | 302 415 (67.1) | 284 355 (63.9) | <.001 |

| Discharge location | ||||

| Home | 1 723 941 (76.9) | 341 917 (75.9) | 336 288 (75.6) | <.001 |

| Skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation | 484 751 (21.6) | 104 724 (23.3) | 97 156 (21.8) | <.001 |

| Transferred | 6364 (0.3) | 1087 (0.2) | 1677 (0.4) | <.001 |

| Other | 25 941 (1.2) | 2254 (0.5) | 9545 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Hospice | 1441 (0.1) | 422 (0.1) | 234 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Type of operation | ||||

| Open aortic aneurysm repair | 132 697 (5.9) | 38 252 (8.5) | 14 374 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Bariatric | 28 625 (1.3) | 6468 (1.4) | 4024 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Carotid endarterectomy | 141 992 (6.3) | 23 283 (5.2) | 27 901 (6.3) | <.001 |

| Esophagectomy | 7787 (0.3) | 2603 (0.6) | 849 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Hip replacement | 631 845 (28.2) | 126 040 (28.0) | 127 521 (28.7) | <.001 |

| Knee replacement | 1 149 572 (51.3) | 209 531 (46.5) | 251 129 (56.4) | <.001 |

| Lung resection | 91 211 (4.1) | 25 321 (5.6) | 12 609 (2.8) | <.001 |

| Mitral valve repair | 17 344 (0.8) | 5331 (1.2) | 1835 (0.4) | <.001 |

| Pancreatectomy | 20 311 (0.9) | 8130 (1.8) | 1653 (0.4) | <.001 |

| Rectal resection | 21 054 (0.9) | 5445 (1.2) | 3005 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Travel distance, mean (SD), miles | 47.9 (173.0) | 56.1 (203.2) | 51.8 (182.0) | <.001 |

| Travel time, mean (SD), min | 53.4 (156.5) | 61.4 (184.5) | 56.8 (165.0) | <.001 |

| Travel distance, median (IQR), miles | 15.5 (7.3-32.4) | 13.7 (6.4-28.9) | 17.1 (6.9-35.5) | <.001 |

| Travel time, median (IQR), min | 25.0 (15.0-42.0) | 24.0 (15.0-39.0) | 26.0 (14.0-46.0) | <.001 |

| Travel time, min | ||||

| <30 | 1 279 085 (57.0) | 269 325 (59.8) | 236 216 (53.1) | <.001 |

| 30-60 | 558 784 (24.9) | 102 432 (22.7) | 119 314 (26.8) | <.001 |

| >60 | 404 569 (18.0) | 78 647 (17.5) | 89 370 (20.1) | <.001 |

| Dual eligibility | 187 864 (8.4) | 48 859 (10.8) | 36 948 (8.3) | <.001 |

This category has been defined by a modification of an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute; this beneficiary race code has no public specifications as to what this race category entails.22

Compared with low-competition hospitals, high-competition hospitals demonstrated higher 30-day mortality for 2 of 10 procedures (mitral valve repair: odds ratio [OR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.07-1.14; and carotid endarterectomy: OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.09) and no difference for 5 of 10 procedures (open aortic aneurysm repair, bariatric surgery, esophagectomy, knee replacement, and hip replacement; ranging from OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-1.00, for hip replacement to OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.94-1.26, for bariatric surgery) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thirty-Day Mortality Across High- and Low-Competition Hospital Markets.

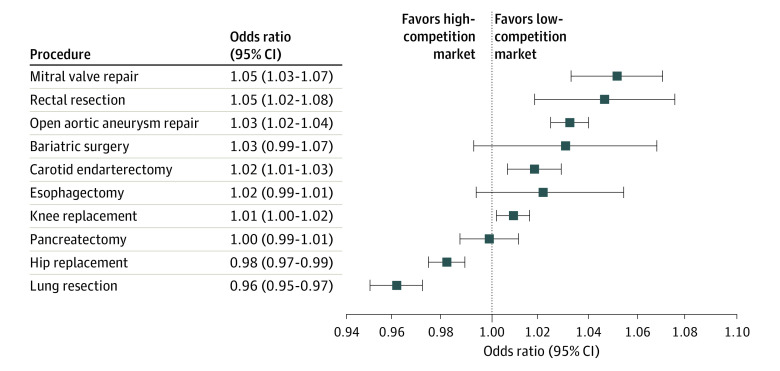

High-competition hospitals also demonstrated 30-day readmissions that were higher for 5 of 10 procedures (open aortic aneurysm repair, knee replacement, mitral valve repair, rectal resection, and carotid endarterectomy procedure; ranging from OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02, for knee replacement to OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02-1.08, for rectal resection) and no difference for 3 procedures (bariatric surgery: OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.99-1.07; esophagectomy: OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.06; and pancreatectomy: OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99-1.01) (Figure 2). The risk-adjusted rates for each outcome by procedure is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2. Thirty-Day Readmissions Across High- and Low-Competition Hospital Markets.

Table 2. Thirty-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Across High- and Low-Competition Hospital Marketsa.

| 30-d Outcome of procedure | Rate, % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI)b | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High competition | Low competition | |||

| Open aortic aneurysm repair | ||||

| Mortality | 2.7 (2.6-2.8) | 2.7 (2.6-2.8) | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | .22 |

| Readmissions | 13.1 (12.9-13.3) | 12.7 (12.5-12.9) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | <.001 |

| Bariatric surgery | ||||

| Mortality | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 0.3 (0.3-0.4) | 1.09 (0.94-1.26) | .25 |

| Readmissions | 5.0 (4.7-5.2) | 4.8 (4.6-5.1) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .12 |

| Esophagectomy | ||||

| Mortality | 6.8 (6.2-7.3) | 7.1 (6.5-7.7) | 0.99 (0.94-1.03) | .56 |

| Readmissions | 20.3 (19.4-21.2) | 19.9 (19.0-20.9) | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | .13 |

| Knee replacement | ||||

| Mortality | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) | .15 |

| Readmissions | 5.1 (5.1-5.2) | 5.0 (5.0-5.1) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .01 |

| Lung resection | ||||

| Mortality | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | 2.6 (2.5-2.7) | 0.88 (0.86-0.90) | <.001 |

| Readmissions | 10.2 (10.0-10.4) | 10.6 (10.4-10.8) | 0.96 (0.95-0.97) | <.001 |

| Mitral valve repair | ||||

| Mortality | 7.5 (7.1-7.9) | 6.8 (6.4-7.2) | 1.11 (1.07-1.14) | <.001 |

| Readmissions | 20.9 (20.2-21.5) | 20.0 (19.4-20.7) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | <.001 |

| Pancreatectomy | ||||

| Mortality | 4.5 (4.2-4.7) | 4.7 (4.4-5.0) | 0.93 (0.90-0.95) | <.001 |

| Readmissions | 23.4 (22.8-24.0) | 23.4 (22.8-24.0) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .86 |

| Rectal resection | ||||

| Mortality | 2.2 (2.0-2.4) | 2.4 (2.2-2.7) | 0.92 (0.86-0.98) | .01 |

| Readmissions | 19.5 (18.9-20.0) | 18.8 (18.2-19.4) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | .002 |

| Carotid endarterectomy | ||||

| Mortality | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 1.06 (1.03-1.09) | <.001 |

| Readmissions | 8.5 (8.3-8.6) | 8.3 (8.1-8.4) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | .002 |

| Hip replacement | ||||

| Mortality | 0.3 (0.3-0.4) | 0.3 (0.3-0.4) | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .09 |

| Readmissions | 5.8 (5.8-5.9) | 5.9 (5.4-6.0) | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | <.001 |

The cohort included Medicare beneficiaries from the fourth quarter of 2015 through 2018 who underwent elective complex procedures (mitral valve repair, open aortic aneurysm repair, lung resection, esophageal resection, pancreatic resection, rectal cancer surgery, hip replacement, knee replacement, carotid endarterectomy, and bariatric surgery).

The risk-adjustment model included procedure, year, age, sex, admission type, nurse ratio, teaching status, dual-eligibility status, and Elixhauser comorbidities. The Elixhauser comorbidities included hypertension, fluid and electrolyte disorders, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, deficiency anemias, hypothyroidism, congestive heart failure, depression, kidney failure, psychoses, valvular disease, coagulopathy, liver disease, neurological disorders, and peripheral vascular disease.

Significant differences existed between Medicare beneficiaries treated at hospitals located in high-competition vs low-competition markets. High-competition hospitals cared for older patients (mean [SD] age, 74.4 [6.6] years vs 74.0 [6.2] years, respectively). These high-competition hospitals also cared for more women (269 872 [59.9%] vs 263 159 [59.2%], respectively) and racial and ethnic minority individuals (those in the groups Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other; 77 322/450 404 [17.3%] vs 23 328/444 900 [5.6%], respectively; P < .001) than low-competition hospitals. High-competition hospitals also cared for more sick patients, defined by having 2 or more Elixhauser comorbidities (302 415/450 404 [67.1%] vs 284 355/444 900 [63.9%] for low-competition hospitals). More patients with dual eligibility for Medicare received care at high-competition hospitals (48 859/444 900 [10.8%] vs 36 948/444 900 [8.3%] for low-competition hospitals).

The most prevalent comorbidity among all observed Medicare beneficiaries in our study cohort was hypertension, and low-competition hospitals had more patients with this comorbidity (317 973/444 900 [71.5%] vs 315 653/450 404 [70.1%] in high-competition hospitals). The top 3 highest-volume procedures carried out at the hospitals in our study cohort were knee replacement, hip replacement, and open aortic aneurysm repair. Knee replacements (251 129 [56.4%] vs 209 531 [46.5%], respectively) and hip replacements (127 521 [28.7%] vs 126 040 [28.0%], respectively) were more likely to be carried out at low-competition hospitals vs high-competition hospitals. In contrast, open aortic aneurysm repair was more likely to be carried out at high-competition hospitals (38 252 [8.5%] vs 14 374 [3.2%] in low-competition hospitals).

High-competition hospitals differed in their discharge location as compared with low-competition hospitals. For example, high-competition hospitals were more likely to discharge their patients home or to a skilled nursing facility than low-competition hospitals. Patients treated at high-competition hospitals were also found to travel further distances and longer times to get to these hospitals than patients who received care at low-competition hospitals.

High-competition hospitals were more likely than low-competition hospitals to be nonprofit institutions (329/470 [70.0%] and 724/1091 [66.4%], respectively). High-competition hospitals also had more beds than low-competition hospitals (≥250 to <500 beds: 192 [40.9%] vs 93 [8.5%], respectively). Most high-competition hospitals were in the western part of the United States (168 [35.7%]) and were teaching hospitals (384 [81.7%]). In comparison, most low-competition hospitals were in the South (393 [36.0%]), and a little more than a third of these hospitals were teaching hospitals (423 [38.8%]). Low-competition hospitals had a higher median (IQR) nurse to staffing ratio of 11 (8-16) vs 8 (7-10) in high-competition hospitals (Table 3).

Table 3. Hospital-Level Characteristics Across High- and Low-Competition Hospital Marketsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | High competition | Low competition | ||

| No. of hospitals | 3166 | 470 | 1091 | |

| No. of patients | 2 242 438 | 450 404 | 444 900 | |

| Ownership | ||||

| For-profit | 546 (17.2) | 96 (20.4) | 135 (12.4) | <.001 |

| Nonprofit | 2152 (68.0) | 329 (70.0) | 724 (66.4) | |

| Other | 468 (14.8) | 45 (9.6) | 232 (21.3) | |

| No. of beds | ||||

| <250 | 2218 (70.1) | 183 (38.9) | 966 (88.5) | <.001 |

| ≥250 to <500 | 666 (21.0) | 192 (40.9) | 93 (8.5) | |

| ≥500 | 282 (8.9) | 95 (20.2) | 32 (2.9) | |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Northeast | 490 (15.5) | 93 (19.8) | 150 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Midwest | 938 (29.6) | 97 (20.6) | 335 (30.7) | |

| South | 1097 (34.6) | 112 (23.8) | 393 (36.0) | |

| West | 641 (20.2) | 168 (35.7) | 213 (19.5) | |

| Teaching hospital | 1797 (56.8) | 384 (81.7) | 423 (38.8) | <.001 |

| Nurse ratio (patient census/nurses), median (IQR) | 9 (7-13) | 8 (7-10) | 11 (8-16) | <.001 |

The cohort included Medicare beneficiaries from the fourth quarter of 2015 through 2018 who underwent elective complex procedures (mitral valve repair, open aortic aneurysm repair, lung resection, esophageal resection, pancreatic resection, rectal cancer surgery, hip replacement, knee replacement, carotid endarterectomy, and bariatric surgery).

Discussion

The present study has 2 principal findings that expand the current understanding of hospital competition and quality of surgical care. First, there was no consistent association between hospital competition and outcomes after high-risk surgery across the 10 high-risk procedures evaluated. Second, high-competition hospitals were found to care for older patients, more racial and ethnic minority patients, and those who had more comorbid conditions. Taken together, our findings challenge the common assumption that hospital competition may be good for care as it relates to complex surgical procedures.

Previous studies have raised concern about the difference in health status of the patient population cared for at high-competition vs low-competition hospitals.23,24 A study by Tang et al24 evaluating data for patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms in California found that hospitals in high-competition markets were more likely to treat patients who were older with higher preoperative risk of mortality. Another study evaluating hospital competition for patients requiring kidney transplantation found that high-competition hospitals were more likely to perform surgery on patients with more comorbidities and higher risk of poor outcomes.7 Similarly, another study conducted by Cerullo et al8 found that high-competition hospitals treated patients with more comorbidities and a high predicted score of mortality. Our present study extends beyond prior work by demonstrating a similar pattern of higher-risk patients at high-competition hospitals across a broad range of procedures in a nationally representative cohort.

Another important finding from this study was that high-competition hospitals had higher rates of 30-day mortality and 30-day readmissions for multiple procedures. While the exact mechanism underlying these findings is not clear, our data suggest at least 2 possibilities. First, hospitals in high-competition markets may be a destination site for patients with more comorbidities.23,25 In our study, patients undergoing care at hospitals in high-competition markets travel longer distances and times. Second, high-competition hospitals may have a lower threshold for offering surgical procedures that may not be offered in low-competition markets.23,25,26 As seen in the present study and others prior, high-competition hospitals are more likely to perform surgery on patients with higher risk of worse outcomes.

Previous work evaluating surgical care across high- and low-competition hospitals has been varied.6 For example, hospital competition has been evaluated for patients requiring kidney transplantation and found increased patient mortality, graft failure, and increased risk of poor outcomes.7 Another study conducted by Cerullo et al8 identified multiple major surgical procedures where competition was associated with lower mortality. They also found that high-competition hospitals were associated with lower rates of failure-to-rescue after complications from coronary artery bypass graft, colon resection, pancreatomy, and liver resection.8 Our present study brings more clarity to these prior conflicting results by demonstrating variation in outcomes across a broad range of procedures in high- and low-competition markets.

Limitations

The present study should be interpreted in the context of multiple limitations. First, the study cohort consists of Medicare beneficiaries, which may threaten the generalizability of the findings. However, by using Medicare data, we had one of the only sources of patient- and hospital-level identifiable information that was more geographically representative than those used in other evaluations. In addition, most of the procedures chosen are more common among older individuals in the United States, with the exception of bariatric surgery, a procedure targeted for quality measurement by third parties.20 Second, administrative Medicare claims data have known limitations to capture certain clinical outcomes. We mitigated this limitation by selecting 30-day mortality and 30-day readmissions rates as outcomes, which can be reliably captured using Medicare claims data.3,10,15,18,19,20 Third, the present study only used 1 measure of hospital market competition that may not entirely capture how market forces may influence surgical outcomes. To make our findings more robust, we applied risk-adjustment models to account for known confounders of the outcomes and carried out additional sensitivity analyses that demonstrated similar results.

Our findings have several important implications for multiple stakeholders interested in hospital competition and quality of care for high-risk surgery. For patients, our findings may help inform a more tailored approach to how they choose a surgeon. Specifically, hospital competition may have variable effects when choosing the ideal location for complex surgical care.27 Although these observed differences have statistical significance, they may not translate to clinical significance that would outweigh the other considerations when choosing a site of care.

Policy makers may also take these findings into consideration regarding efforts toward optimizing hospital competition. Because there was no clear association between hospital competition and improved outcomes, policy makers may not rely on hospital competition as a rationale for trying to improve care, especially as it pertains to surgical care.

Conclusions

This study did not identify evidence that hospital market competition was consistently associated with improved outcomes after high-risk surgery. Compared with hospitals in low-competition markets, hospitals located in high-competition markets cared for sicker patients. Efforts to understand and address any competition-related differences in surgical quality should investigate other factors that may affect quality of surgical care aside from hospital competition.

eTable 1. 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Across Non-Rural High and Low-Competition Hospital Markets

eTable 2. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Patient Complexity

eTable 3. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Travel Distance

eTable 4. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Insurance Type

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leapfrog Group . Complex adult and pediatric surgery. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://ratings.leapfroggroup.org/measure/hospital/2022/complex-adult-and-pediatric-surgery

- 3.Rogowski J, Jain AK, Escarce JJ. Hospital competition, managed care, and mortality after hospitalization for medical conditions in California. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):682-705. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00631.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler DP, McClellan MB. Is hospital competition socially wasteful?. Q J Econ. 2000;115(2):577-615. doi: 10.1162/003355300554863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gozvrisankaran G, Town RJ. Competition, payers, and hospital quality. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 1):1403-1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00185.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen Y-C. The effect of financial pressure on the quality of care in hospitals. J Health Econ. 2003;22(2):243-269. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler JT, Sethi RK, Yeh H, Markmann JF, Nguyen LL. Market competition influences renal transplantation risk and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;260(3):550-556. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerullo M, Chen SY, Gani F, et al. The relationship of hospital market concentration, costs, and quality for major surgical procedures. Am J Surg. 2018;216(6):1037-1045. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Marth NJ, Goodman DC. Regionalization of high-risk surgery and implications for patient travel times. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2703-2708. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Research Data Assistance Center . Medicare provider analysis and review (MEDPAR) file. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://resdac.org/cms-data/files/medpar

- 11.American Hospital Association . AHA annual survey database [registration required]. Accessed August 25, 2022. http://www.ahadataviewer.com/book-cd-products/AHA-Survey

- 12.Cummings M, YaleNews . A Yale economist on taming rising hospital prices while maintaining quality. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://news.yale.edu/2022/03/07/yale-economist-taming-rising-hospital-prices-while-maintaining-quality

- 13.Cooper Z, Doyle JJ, Graves JA, Gruber J. Do Higher-Priced Hospitals Deliver Higher-Quality Care? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2022. doi: 10.3386/w29809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim AM, Hughes TG, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of hospital critical access status with surgical outcomes and expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2095-2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1134-1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1303118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart JW II, Kunnath N, Dimick JB, Pagani FD, Ailawadi G, Ibrahim AM. Coronary artery bypass surgery amongst Medicare beneficiaries in health professional shortage areas. Ann Surg. Published online October 18, 2022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of hospital participation in a quality reporting program with surgical outcomes and expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2015;313(5):496-504. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheetz KH, Chhabra KR, Smith ME, Dimick JB, Nathan H. Association of discretionary hospital volume standards for high-risk cancer surgery with patient outcomes and access, 2005-2016. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1005-1012. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbach DR. Pledging to eliminate low-volume surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(15):1388-1390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1508472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care. 2004;42(4):355-360. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Research Data Assistance Center . Research Triangle Institute (RTI) race code. Accessed June 23, 2023. https://resdac.org/cms-data/variables/research-triangle-institute-rti-race-code

- 23.Kessler DP, Geppert JJ. The effects of competition on variation in the quality and cost of medical care. J Econ Manage Strategy. 2005;14(3):575-589. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9134.2005.00074.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang OY, Yoon JS, Durand WM, Ahmed SA, Lawton MT. The impact of interhospital competition on treatment strategy and outcomes for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(4):695-703. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyab258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaynor M, Town RJ. Competition in health care markets. In: Pauly M, McGuire T, Barros PP, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Elsevier Science & Technology Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siciliani L, Chalkley M, Gravelle H, eds; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies . Does provider competition improve health care quality and efficiency? Expectations and evidence from Europe. Published November 14, 2022. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/does-provider-competition-improve-health-care-quality-and-efficiency-expectations-and-evidence-from-europe [PubMed]

- 27.Mutter RL, Romano PS, Wong HS. The effects of US hospital consolidations on hospital quality. Int J Econ Bus. 2011;18(1):109-126. doi: 10.1080/13571516.2011.542961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Across Non-Rural High and Low-Competition Hospital Markets

eTable 2. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Patient Complexity

eTable 3. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Travel Distance

eTable 4. Comparison of 30-Day Mortality and 30-Day Readmissions Outcomes by Insurance Type

Data Sharing Statement