Abstract

Background:

Little is known about risk factors for repeated opioid overdose and fatal opioid overdose in the first year following nonfatal opioid overdose.

Methods:

We identified a national retrospective longitudinal cohort of patients aged 18–64 years in the Medicaid program who received a clinical diagnosis of nonfatal opioid overdose. Repeated overdoses and fatal opioid overdoses were measured with the Medicaid record and the National Death Index. Rates of repeat overdose per 1000 person-years and fatal overdose per 100,000 person-years were determined. Hazard ratios of repeated opioid overdose and fatal opioid overdose were estimated by Cox proportional hazards.

Results:

Nearly two-thirds (64.8%) of the patients with nonfatal overdoses (total n = 75,556) had filled opioid prescriptions in the 180 days before initial overdose. During the 12 months after nonfatal overdose, the rate of repeat overdose was 295.0 per 1000 person-years and that of fatal opioid overdose was 1154 per 100,000 person-years. After controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and region, the hazard of fatal opioid overdose was increased for patients who had filled a benzodiazepine prescription in the 180 days prior to their initial overdose (HR = 1.71, 95%CI: 1.46–1.99), whose initial overdose involved heroin (HR = 1.57, 95%CI:1.30–1.89), or who required mechanical ventilation at the initial overdose (HR = 1.86, 95%CI = 1.50–2.31).

Conclusions:

Adults treated for opioid overdose frequently have repeated opioid overdoses in the following year. They are also at high risk of fatal opioid overdose throughout this period, which underscores the importance of efforts to engage and maintain patients in evidence-based opioid treatments following nonfatal overdose.

Keywords: Opioid overdose, Risk factors, Opioid-related mortality

1. Introduction

The United States is confronting an unparalleled epidemic of opioid overdose deaths. Between 1999 and 2015, the number of opioid-related deaths in the US increased from 8048 to 33,091 (Center for Disease Control (CDC), 2016). There have also been substantial increases in opioid-related hospital admissions and emergency department visits (Weiss et al., 2017). In this context, attention has focused on identifying individuals at high risk for fatal opioid overdose because they present clinical opportunities for potentially lifesaving interventions (Naeger et al., 2016; Frazier et al., 2017).

Regular opioid users are at markedly increased risk of fatal opioid overdose (Darke et al., 2011). In a meta-analysis, regular or dependent opioid users had a standardized mortality rate ratio nearly fifteen times greater than demographically matched controls and overdose was the leading cause of death (Degenhardt et al., 2010). Among opioid dependent patients, nonfatal overdose poses particularly high short-term risks of mortality (Kelty and Hulse, 2017; Stoove et al., 2009). Following overdose, an Austrian cohort of opioid users was nearly 50 times more likely to die than matched community controls and most of their deaths involved opioids (Risser et al., 2001). After an overdose, there is also a substantial risk of repeat overdose (Larochelle et al., 2016; Hasegawa et al., 2014).

Much remains to be learned about which patients are at the greatest risk of fatal opioid overdose following a nonfatal overdose. From clinical and policy perspectives, adults with prescription opioid overdoses are a high priority population. Prescription opioids are involved in most opioid-related deaths (Center for Disease Control (CDC), 2016). Although prescription opioids and heroin are pharmacologically similar and heroin users frequently initiate nonmedical prescription opioid use before starting heroin (Peavy et al., 2012; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2015; Cicero et al., 2014), only around 4% (Muhuri et al., 2013; DEA, 2015) of nonmedical prescription opioid users start using heroin each year suggesting they are distinct though overlapping populations. There are also differences in their background characteristics (Unick and Ciccarone, 2017).

We examined risks of repeat opioid overdose including fatal opioid overdose during the first year following nonfatal overdose. The analysis was limited to Medicaid enrollees, a large insured population in the US, that is at high risk of fatal opioid overdose (Dunn et al., 2010). Because opioid overdose death rates in the US are higher for males than females and for white than black or Hispanic adults (Rudd et al., 2016), we anticipated similar gender and ethnic differences in risk of fatal overdose following nonfatal overdose. Because admissions for heroin overdoses compared to admissions for prescription opioid overdoses pose higher risks of in-hospital death (Hsu et al., 2017), we hypothesized that nonfatal heroin overdoses compared to prescription opioid overdoses would pose higher risks of future fatal overdose. We further hypothesized that fatal overdoses would be less strongly related to nonfatal overdoses preceded by opioid prescription fills than to overdoses without preceding opioid prescription fills which are presumably related to illicit opioid use.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sources of data

The opioid overdose cohort was extracted from 2001 to 2007 national (45 states, not including Arizona, Delaware, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island or the District of Columbia) Medicaid Analytic Extract data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Dates and cause of death information were derived from linkage to the National Death Index, which provides a complete accounting of state-recorded deaths in the US and is the most complete resource for tracing mortality in national samples (Wojcik et al., 2010).

2.2. Assembly of nonfatal opioid overdose cohorts

The cohort was restricted to adults aged 18 to 64 years with a clinical diagnosis of relevant poisoning codes (965.0X, E850.0X, E850.1X, E850.2X) (Larochelle et al., 2016) who were eligible for Medicaid services during the 180 days preceding the overdose (poisoning code). Patients with overdoses that were fatal (n = 165) were excluded from the cohort. The first eligible nonfatal overdose was selected and no patient contributed more than one observation. In analyses in which fatal opioid overdose was the outcome, the cohort was followed forward from their index date for 365 days, date of death from any cause, or end of available data, whichever came first. In analyses in which repeat (nonfatal or fatal) overdoses was the outcome, the cohort was followed forward for 365 days, first repeat overdose, death from any cause, or end of available data, whichever came first. For nonfatal opioid overdoses treated in outpatient or emergency department settings, the index date was the date of overdose treatment. For index overdoses treated in inpatient settings, the index date was date of hospital discharge from the associated inpatient admission. To distinguish new events, fatal and second nonfatal overdose events were defined as occurring > 1 day following the index overdose.

2.3. Fatal opioid overdose and repeated opioid overdose

Fatal opioid overdose included poisonings by and adverse effects of opioids (T40.0X), heroin (T40.1X), other natural and semi-synthetic opioids (T40.2X), methadone (T40.3X), synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4X), and unspecified narcotics (T40.6X) (Rudd et al., 2016). Repeated opioid overdose was defined as the first nonfatal or fatal opioid overdose occurring after the index opioid overdose.

2.4. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Based on Medicaid eligibility data, cohort members were classified by sex, age in years (18–34, 35–44, 45–64), and race/ethnicity: Hispanic; white, non-Hispanic (white); black, non-Hispanic (black); and other, non-Hispanic (other) including American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

Variables representing mental health diagnoses occurring on or within 180 days before the index nonfatal overdose included depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other non-substance use mental health disorders, substance use, drug use, opioid use, and alcohol use disorders as defined by ICD-9 codes (See supplemental materials). Separate variables defined medication assisted treatment (methadone through service codes (HCPCS H0020), buprenorphine prescriptions or naltrexone prescriptions), a chronic pain condition (Bohnert et al., 2016), use of mechanical ventilation at the index non-fatal overdose which defined “near fatal” events (Hasegawa et al., 2014), and a claims-based Charlson Comorbidity Score (Deyo et al., 1992) to measure medical comorbidity burden (Sharabiani et al., 2012). Index nonfatal overdoses were defined as occurring in the outpatient, emergency department, or inpatient setting with place of service codes. Pharmacy claims classified cohort members with respect to presence of filled prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers during the 180 days before index nonfatal overdose. A separate variable defined ≥1 filled opioid prescriptions during the 30 days before the index overdose.

In a separate analysis, the specific causes of death of the opioid-related decedents were characterized with respect to selected substance-related poisoning codes.

2.5. Analysis

For the nonfatal opioid overdose cohort, we first determined percentages by each demographic and clinical stratum overall and compared the characteristics with and without opioid prescriptions in the preceding 180 days. We then determined for each stratum, the number of patients, person-years of follow-up, number with ≥1 repeat overdose event within a year, and first repeat overdose rates per 1000 person-years of follow-up. We then determined corresponding stratified rates of opioid-related deaths per 100,000 person-years of follow-up. Cox proportional hazard models determined unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios of repeat (nonfatal or fatal) overdose and fatal opioid overdose during the follow-up period with each stratification variable as the independent variable of interest. Separate models were fit for patients who did and did not fill an opioid prescription in the 30 days before their index overdose. In separate models, a stratum by opioid prescription interaction term tested whether there were differences in the hazard of fatal opioid overdose across these two groups. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (RTI, Research Triangle Park, NC). In this large, exploratory study, no adjustments were made to the many P values for the multiple comparisons; therefore, the P values should be interpreted with caution.

3. Results

3.1. Patients with nonfatal opioid overdoses

Most of the patients with nonfatal overdoses were white, over 34 years old, or were women, consistent with the overall gender composition of Medicaid beneficiaries (Table 1). The most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders were drug use and depressive disorders. Nearly all patients with nonfatal overdoses had made an outpatient visit in the previous 180 days, most had filled a prescription for an opioid (64.8%) during that period, many (35.8%) during the 30 days before their overdose. Antidepressant (55.5%) and benzodiazepine (48.9%) prescriptions were also commonly filled during the 180 days before overdose.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of adults with non-fatal opioid overdoses overall and by recent opioid prescription.

| Characteristics | Total opioid overdoses % (N = 75,556) | Opioid Overdoses With Recent Opioid Prescriptions % (N = 48,999) | Opioid Overdoses Without Recent Opioid Prescriptions % (N = 26,557) | Unadjusted OR 95% CI (without recent opioid Rx reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–34 | 29.6 | 26.8 | 35.0 | 1.00 |

| 35–44 | 28.3 | 28.6 | 27.8 | 1.34 (1.29, 1.40) |

| 45–64 | 42.0 | 44.6 | 37.2 | 1.56 (1.51, 1.62) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 40.8 | 36.1 | 49.6 | 0.58 (0.56, 0.59) |

| Female | 59.2 | 63.9 | 50.4 | 1.00 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 7.9 | 6.1 | 11.2 | 0.46 (0.44, 0.49) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 71.1 | 75.4 | 63.2 | 1.00 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.7 | 15.1 | 22.5 | 0.56 (0.54, 0.58) |

| Other, non-Hispanica | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) |

| Any recent outpatient visit b | 92.6 | 97.4 | 83.8 | 7.41 (6.94, 7.90) |

| Recent chronic pain condition b | 58.9 | 72.5 | 33.8 | 5.15 (4.99, 5.32) |

| Recent clinical diagnoses b | ||||

| Mental healthb | 47.0 | 51.7 | 38.5 | 1.71 (1.66, 1.76) |

| Depression disorder | 21.6 | 24.2 | 16.9 | 1.56 (1.50, 1.62) |

| Anxiety disorder | 14.9 | 17.8 | 9.6 | 2.03 (1.94, 2.13) |

| Bipolar disorder | 9.5 | 10.3 | 7.9 | 1.34 (1.27, 1.42) |

| Schizophrenia | 6.6 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.96) |

| Other mental health | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 1.18 (1.10, 1.27) |

| Substance use | 38.4 | 37.8 | 39.4 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.96) |

| Drug use | 34.9 | 34.2 | 36.1 | 0.92 (0.89, 0.95) |

| Opioid use | 15.9 | 13.2 | 20.8 | 0.58 (0.56, 0.60) |

| Alcohol use | 11.8 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87) |

| Recent medication assisted treatment b | 2.4 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.52 (0.47, 0.57) |

| Recent prescription medications b | ||||

| Opioids | 64.8 | 100 | 0 | N/A |

| Opioids within 30 days | 35.8 | 50.9 | 0 | N/A |

| Benzodiazepines | 48.9 | 59.9 | 28.6 | 3.73 (3.61, 3.85) |

| Antidepressants | 55.5 | 66.9 | 34.5 | 3.84 (3.72, 3.97) |

| Antipsychotics | 25.6 | 28.8 | 19.6 | 1.66 (1.60, 1.72) |

| Mood stabilizers | 29.7 | 36.9 | 16.3 | 3.01 (2.90, 3.12) |

| Opioid overdose treatment setting | ||||

| Outpatient | 32.8 | 32.7 | 33.0 | 1.00 |

| Emergency department | 27.6 | 27.0 | 28.7 | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) |

| Inpatient | 39.6 | 40.3 | 38.3 | 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) |

| Opioid overdose drug | ||||

| Heroin | 19.8 | 12.4 | 33.6 | 0.28 (0.27, 0.29) |

| Prescription opioids | 80.2 | 87.6 | 66.4 | 1.00 |

| Near fatal event | 6.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | T score, p-value | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 0.32 (0.78) | 0.38 (0.86) | 0.20 (0.61) | 32.70 (< .0001) |

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days before the opioid overdose event.

Compared to those who did not fill opioid prescriptions in the 180 days before overdose, those filling opioid prescriptions tended to be older, white, and female. They were also more likely to have been recently diagnosed with a chronic pain disorder, depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder. In relation to patients without opioid prescriptions in the past 180 days, those with opioid prescriptions had nearly four times the odds of having filled a benzodiazepine prescription during this period and less than one-third the odds of having their index overdose involve heroin (Table 1).

3.2. One-year repeated opioid overdose

Among the nonfatal overdose cohort, 18.9% (14,263 of 75,556) had repeated opioid overdoses during the follow-up period (Table 2). After controlling for demographic characteristics, the hazard of repeated opioid overdose was greater for white than Hispanic or black patients and for men than women. The adjusted hazards of repeat overdose were also higher for patients with each of the recent clinical psychiatric diagnoses and for patients who had filled prescriptions for each class of psychotropic prescription. Patients whose overdose involved heroin were at higher risk of repeat overdose than those whose initial overdose involved prescription opioids.

Table 2.

Repeat opioid overdosesa among adult Medicaid patients during the first year following a nonfatal overdose.

| Group | Number of Patients N | Person-years at risk | First Repeat Overdose N | Unadjusted Repeat Overdose Rate (per 1000 person-yrs) | Hazard Ratio of Repeat Overdose (95%CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Repeat Overdoseb (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total | 75556 | 48343 | 14263 | 295 | N/A | N/A |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18–34 | 22399 | 13553 | 3853 | 284 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 35–44 | 21411 | 14222 | 4024 | 283 | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) |

| 45–64 | 31746 | 20568 | 6386 | 310 | 1.15 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 30866 | 19274 | 6095 | 316 | 1.09 (1.06, 1.13) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.13) |

| Female | 44690 | 29069 | 8168 | 281 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 5822 | 3788 | 928 | 245 | 0.80 (0.75, 0.86) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.86) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 52388 | 33107 | 10185 | 308 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13030 | 8656 | 2303 | 266 | 0.88 (0.84, 0.92) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) |

| Other, non-Hispanicc | 2439 | 1601 | 460 | 287 | 0.95 (0.87, 1.05) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) |

| Recent chronic pain condition d | ||||||

| Present | 44508 | 28346 | 9159 | 323 | 1.27 (1.23, 1.32) | 1.25 (1.21, 1.30) |

| Absent | 31048 | 19996 | 5104 | 255 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Any recent outpatient visit d | 69993 | 44809 | 13477 | 301 | 1.38 (1.28, 1.48) | 1.36 (1.26, 1.46) |

| Recent clinical diagnoses d | ||||||

| Mental health | 35526 | 22695 | 7431 | 327 | 1.23 (1.19, 1.28) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.27) |

| Substance use | 29011 | 17890 | 6504 | 364 | 1.37 (1.32, 1.42) | 1.38 (1.34, 1.43) |

| Drug use | 26353 | 16251 | 5961 | 367 | 1.36 (1.32, 1.41) | 1.38 (1.33, 1.43) |

| Opioid use | 11998 | 7277 | 2931 | 403 | 1.39 (1.33, 1.45) | 1.47 (1.40, 1.53) |

| Alcohol use | 8954 | 5462 | 1956 | 358 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25) |

| Recent MAT c | 1776 | 1054 | 377 | 358 | 1.15 (1.04, 1.28) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) |

| Recent prescription medications c | ||||||

| Opioids | 48999 | 31749 | 9681 | 305 | 1.14 (1.10, 1.18) | 1.13 (1.09, 1.17) |

| Opioids within 30 days | 27064 | 17997.2 | 5637 | 313 | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.17) |

| Benzodiazepines | 36952 | 23757 | 7803 | 328 | 1.27 (1.23, 1.31) | 1.25 (1.20, 1.29) |

| Antidepressants | 41926 | 27516 | 8510 | 309 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.21) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.20) |

| Antipsychotics | 19306 | 12727 | 4111 | 323 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) |

| Mood stabilizers | 22422 | 14728 | 4720 | 320 | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.18) |

| Opioid overdose treatment setting | ||||||

| Outpatient | 23531 | 14624 | 5176 | 354 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Emergency department | 19758 | 12546 | 3726 | 297 | 0.83 (0.80, 0.87) | 0.83 (0.79, 0.86) |

| Inpatient | 28402 | 18672 | 4569 | 245 | 0.70 (0.67, 0.73) | 0.70 (0.67, 0.73) |

| Opioid overdose drug | ||||||

| Heroin | 14970 | 9389 | 3206 | 342 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.22) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.27) |

| Prescription opioids | 60586 | 38954 | 11057 | 284 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Near fatal event | ||||||

| Present | 5179 | 3370 | 632 | 188 | 0.62 (0.57, 0.67) | 0.61 (0.56, 0.66) |

| Absent | 70377 | 44974 | 13631 | 303 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Includes fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses.

Adjusted HRs are from models that control for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days before the index opioid overdose event. MAT denotes medication assisted treatment.

Patients whose initial overdoses were treated in inpatient settings had the lowest risks of repeat overdose followed by patients who were treated in emergency departments while those who were treated in outpatient settings had the highest risks of repeat overdose. Near-fatal (requiring ventilation assistance) initial overdoses were also associated with lower risks of repeated overdose. In a post-hoc analysis, over three-quarters (79.3%) of patients whose initial overdoses were near fatal were treated in inpatient settings.

3.3. One-year opioid-related death

In the first 12 months following nonfatal opioid overdose, 1.0% (770 of 76,166) died of an overdose involving opioids (Table 3). In adjusted analyses, the hazard of fatal opioid overdose was higher for males than females, older than younger adults, and whites than other racial/ethnic groups. Initial nonfatal overdoses that were nearly fatal or included heroin were also associated with increased risk of subsequent fatal opioid overdose as were overdoses preceded by a filled prescription for a benzodiazepine and to a lesser extent overdoses preceded by filled prescriptions for antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or antidepressants.

Table 3.

Fatal opioid overdoses among adult Medicaid patients during the first year following a nonfatal overdose.

| Group | Number of Patients Na | Person-years at risk | Fatal Opioid Overdoses N | Unadjusted Fatal Opioid Overdose Rate (per 100k person-yrs) | Hazard Ratio of Fatal Opioid Overdose (95%CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Fatal Opioid Overdoseb (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total | 76166 | 66736 | 770 | 1154 | N/A | N/A |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18–34 | 22557 | 20257 | 165 | 814 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 35–44 | 21563 | 19322 | 251 | 1299 | 1.59 (1.31, 1.94) | 1.63 (1.33, 1.99) |

| 45–64 | 32046 | 27157 | 354 | 1304 | 1.58 (1.32, 1.91) | 1.64 (1.36, 1.99) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 31153 | 27107 | 380 | 1402 | 1.42 (1.24, 1.64) | 1.43 (1.24, 1.65) |

| Female | 45013 | 39629 | 390 | 984 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 5854 | 5212 | 37 | 710 | 0.53 (0.38, 0.74) | 0.58 (0.42, 0.82) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 52833 | 46130 | 615 | 1333 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13133 | 11575 | 79 | 682 | 0.51 (0.41, 0.65) | 0.50 (0.40, 0.63) |

| Other, non-Hispanicc | 2449 | 2189 | 14 | 640 | 0.48 (0.28, 0.82) | 0.57 (0.33, 0.97) |

| Recent chronic pain condition d | ||||||

| Present | 44867 | 38948 | 507 | 1302 | 1.37 (1.18, 1.59) | 1.26 (1.08, 1.48) |

| Absent | 31299 | 27788 | 263 | 946 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Any recent outpatient visit d | 70542 | 61784 | 714 | 1156 | 1.02 (0.78, 1.34) | 0.96 (0.73, 1.27) |

| Recent clinical diagnoses d | ||||||

| Mental healthd | 35799 | 31337 | 406 | 1296 | 1.26 (1.09, 1.45) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41) |

| Substance use | 29254 | 25662 | 345 | 1344 | 1.30 (1.13, 1.50) | 1.30 (1.12, 1.50) |

| Drug use | 26571 | 23337 | 304 | 1303 | 1.21 (1.05, 1.40) | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) |

| Opioid use | 12105 | 10695 | 141 | 1318 | 1.18 (0.98, 1.41) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.51) |

| Alcohol use | 9035 | 7910 | 128 | 1618 | 1.48 (1.23, 1.79) | 1.35 (1.11, 1.65) |

| Recent MAT d | 1792 | 1498 | 14 | 935 | 0.80 (0.47, 1.36) | 0.79 (0.47, 1.35) |

| Recent prescription medications d | ||||||

| Opioids | 49383 | 43491 | 532 | 1223 | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40) | 1.13 (0.96, 1.33) |

| Opioids within 30 days | 27144 | 24108.4 | 285 | 1182 | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) |

| Benzodiazepines | 37257 | 32439 | 497 | 1532 | 1.92 (1.66, 2.23) | 1.71 (1.46, 1.99) |

| Antidepressants | 42250 | 37537 | 482 | 1284 | 1.31 (1.13, 1.52) | 1.23 (1.06, 1.43) |

| Antipsychotics | 19441 | 17289 | 248 | 1434 | 1.36 (1.17, 1.59) | 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) |

| Mood stabilizers | 22601 | 19851 | 285 | 1436 | 1.39 (1.20, 1.61) | 1.30 (1.11, 1.51) |

| Opioid overdose treatment setting | ||||||

| Outpatient | 23664 | 21039 | 230 | 1093 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Emergency department | 19872 | 17428 | 181 | 1039 | 0.95 (0.78, 1.15) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) |

| Inpatient | 28744 | 24745 | 309 | 1249 | 1.14 (0.96, 1.35) | 1.05 (0.88, 1.25) |

| Opioid overdose drug | ||||||

| Heroin | 15093 | 13653 | 191 | 1399 | 1.29 (1.10, 1.52) | 1.57 (1.30, 1.89) |

| Prescription opioids | 61073 | 53083 | 579 | 1091 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Near fatal event | ||||||

| Present | 5360 | 4394 | 100 | 2276 | 2.11 (1.71, 2.60) | 1.86 (1.50, 2.31) |

| Absent | 70806 | 62343 | 670 | 1075 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

The analysis includes 610 patients who were excluded from repeat overdose analyses due to Medicaid eligibility criteria required of inpatient events.

Adjusted HRs are from models that control for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days before the index opioid overdose event. MAT denotes medication assisted treatment.

3.4. Opioid prescriptions and opioid-related death

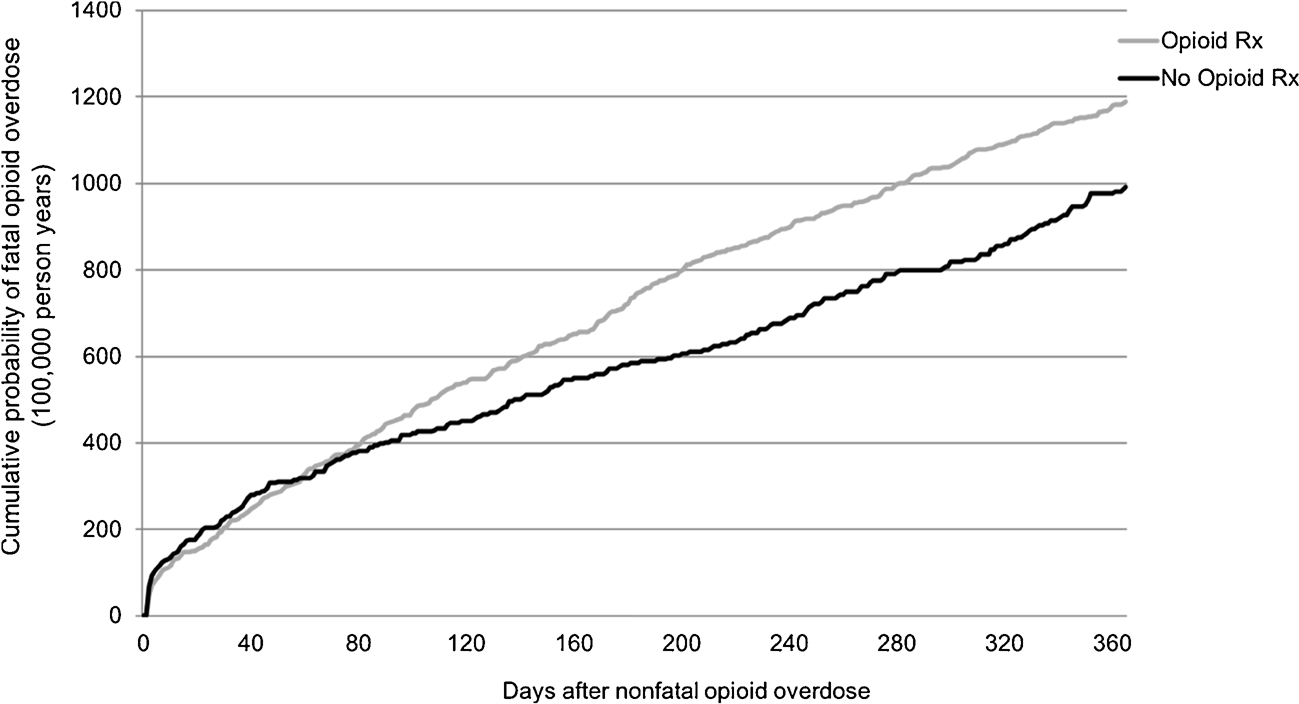

In relation to overdose patients without recent opioid prescriptions, those with opioid prescriptions in the 180 days before their initial overdose had a greater hazard of repeated overdose and fatal opioid overdose, though the latter association was not significant after controlling for background demographic characteristics (Tables 2 and 3). In both groups, the cumulative risk of fatal opioid overdose did not plateau during the first year following nonfatal overdose (Fig. 1). In adjusted models, the association between male sex and risk of overdose death involving opioids was significantly stronger among overdose patients with than without recent filled opioid prescriptions (Table 4). Similarly, the association between heroin-related overdose, substance use, drug use, and opioid use disorder diagnoses and risk of opioid-related deaths were each significantly stronger for patients who had filled than had not filled an opioid prescription during the 180 days before their initial overdose.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative probability of fatal opioid overdose of patients with and without recent opioid prescriptions during the 365 days after a nonfatal opioid overdose. Log-rank test for opioid prescription with fatal opioid overdose as outcome, ×2 = 5.42, df = 1, p = 0.02.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards regression models of fatal opioid overdose during year following opioid overdose events for adult Medicaid patients with and without recent opioid prescriptions.

| Characteristic | Total Adjusted HR (95% CI) | With Opioid Prescriptions Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Without Opioid Prescriptions Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Interaction P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–34 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| 35–44 | 1.63 (1.33, 1.99) | 1.56 (1.22, 1.99) | 1.67 (1.18, 2.38) | 0.20 |

| 45–64 | 1.64 (1.36, 1.99) | 1.48 (1.17, 1.87) | 1.93 (1.39, 2.67) | 0.86 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.43 (1.24, 1.65) | 1.62 (1.36, 1.93) | 1.11 (0.86, 1.45) | 0.007 |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.58 (0.42, 0.82) | 0.55 (0.34, 0.88) | 0.68 (0.42, 1.09) | 0.98 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.50 (0.40, 0.63) | 0.52 (0.39, 0.71) | 0.48 (0.33, 0.70) | 0.46 |

| Other, non-Hispanica | 0.57 (0.33, 0.97) | 0.75 (0.43, 1.31) | 0.15 (0.02, 1.08) | 0.06 |

| Recent chronic pain condition b | ||||

| Present | 1.26 (1.08, 1.48) | 1.24 (1.004, 1.53) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.57) | 0.77 |

| Absent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Any recent outpatient visit b | 0.96 (0.73, 1.27) | 0.67 (0.43, 1.04) | 1.03 (0.72, 1.48) | 0.26 |

| Recent clinical diagnoses b | ||||

| Mental healthb | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41) | 1.20 (1.003, 1.43) | 1.24 (0.95, 1.61) | 0.54 |

| Substance use | 1.30 (1.12, 1.50) | 1.38 (1.16, 1.64) | 1.11 (0.84, 1.46) | 0.02 |

| Drug use | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.32 (1.10, 1.57) | 1.05 (0.79, 1.39) | 0.02 |

| Opioid use | 1.24 (1.01, 1.51) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.74) | 1.02 (0.72, 1.44) | 0.03 |

| Alcohol use | 1.35 (1.11, 1.65) | 1.52 (1.20, 1.91) | 1.01 (0.68, 1.49) | 0.01 |

| Recent MAT c | 0.79 (0.47, 1.35) | 0.64 (0.29, 1.45) | 0.98 (0.48, 2.00) | 0.64 |

| Recent prescription medications b | ||||

| Benzodiazepines | 1.71 (1.46, 1.99) | 1.69 (1.38, 2.06) | 1.75 (1.34, 2.29) | 0.54 |

| Antidepressants | 1.23 (1.06, 1.43) | 1.32 (1.08, 1.61) | 1.05 (0.80, 1.38) | 0.19 |

| Antipsychotics | 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) | 1.37 (1.14, 1.64) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) | 0.14 |

| Mood stabilizers | 1.30 (1.11, 1.51) | 1.27 (1.06, 1.51) | 1.34 (0.98, 1.84) | 0.93 |

| Opioid poisoning treatment setting | ||||

| Outpatient | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Emergency department | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.23) | 1.04 (0.73, 1.48) | 0.49 |

| Inpatient | 1.05 (0.88, 1.25) | 1.06 (0.86, 1.30) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) | 0.63 |

| Opioid overdose drug | ||||

| Heroin | 1.57 (1.30, 1.89) | 1.83 (1.44, 2.33) | 1.47 (1.09, 1.99) | 0.002 |

| Prescription opioids | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Near fatal event | ||||

| Present | 1.86 (1.50, 2.31) | 1.59 (1.21, 2.08) | 2.60 (1.81, 3.73) | 0.09 |

| Absent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

Adjusted HRs are from models that control for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.

Includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

During 180 days before the index overdose event.

MAT denotes medication assisted treatment.

3.5. Fatal opioid overdoses

Methadone (31.8%) and to a lesser extent heroin (7.7%) poisoning was involved in a substantial percentage of fatal opioid overdoses. Nearly one-fifth (19.1%) of opioid overdose deaths also involved benzodiazepine poisoning, including 22.3% of opioid decedents with benzodiazepine prescription fills and 12.7% of those without benzodiazepine fills before their initial opioid overdose (p < .0001). Alcohol poisoning (4.6% vs. 7.7%, p = 0.01) and cocaine (14.5% vs 22.1%, p = 0.003) poisoning were significantly less commonly involved in fatal opioid overdoses of patients who had filled than those who had not filled an opioid prescription during the 180 days before their initial opioid overdose.

4. Discussion

In the 12 months following nonfatal opioid overdoses presenting for medical care, approximately 1% of patients died of drug overdoses involving opioids. Nonfatal overdose is therefore a significant risk for subsequent fatal overdose. The risk of fatal opioid overdose was roughly twice as high following nonfatal overdoses that required ventilation assistance. Other groups at higher risk for fatal overdose included patients with nonfatal opioid overdoses who were older in age, those who had recently been prescribed benzodiazepines, and those whose non-fatal overdoses involved heroin.

Nonfatal opioid overdoses, even when treated by health care professionals, pose a high risk of subsequent fatal overdose. The rate of opioid overdose mortality was nearly 200 times higher than the corresponding rate in the general population (6 per 100,000 person-years) (Rudd et al., 2016). Whether patients with nonfatal overdoses presented to emergency departments, outpatient settings, or inpatient settings had little bearing on their subsequent risk of fatal opioid overdose. The rate of opioid overdose mortality following nonfatal opioid overdose in this US sample (1154 per 100,000 person-years) resembles the rate of drug overdose deaths (1.20 per 100 person-years) reported from a cohort of adults following nonfatal heroin overdose in Melbourne, Australia (n = 4884) who were followed for a mean 2.24 years (Stoove et al., 2009).

As compared to nonfatal overdoses that did not require ventilation, those requiring ventilation had approximately twice the risk of subsequent fatal opioid overdose. In prior analyses of nonfatal opioid overdoses, patients requiring ventilation were more often diagnosed with chronic pulmonary disease, neurological disorders, and alcohol use disorder (Hasegawa et al., 2014). Comorbid medical conditions within this patient population, especially conditions compromising respiratory function, may increase future risk of fatal opioid overdose. In acute care settings, overdoses requiring mechanical ventilation have substantial risks of mortality related to hypoxemia (Pfister et al., 2016).

Because benzodiazepines potentiate opioid induced respiratory suppression (Horsfall and Sprague, 2017), it is not surprising that patients who had filled benzodiazepine prescriptions prior to their initial nonfatal overdose were at an increased risk of fatal opioid overdose and that these deaths disproportionately also involve benzodiazepine overdose. These findings are consistent with an earlier report linking benzodiazepine prescriptions to increased odds of nonfatal opioid overdose (Cochran et al., 2017). In the present study, 19.1% of opioid-related fatalities also involved benzodiazepines. This is lower than a corresponding percentage of opioid overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines in a study from San Francisco (27.5%) (Visconti et al., 2015) or from a national analysis of pharmaceutical overdose deaths (30.1%) (Jones et al., 2013). Nevertheless, these patterns suggest considerable caution should be exercised in prescribing benzodiazepines to patients with a history of opioid overdose.

Patients with nonfatal heroin overdoses were more likely to go on to have fatal opioid overdoses than were patients whose initial opioid overdoses did not involve heroin. Some of this increased risk may be related to vulnerabilities common to heroin users including high rates of hepatitis, excessive drinking, cigarette smoking, and other drug problems (Hser et al., 2001) as well as more dangerous opioid use related to seeking a more potent high through injection drug use (Lankenau et al., 2012). More recently, fentanyl and related contaminants in the heroin supply have posed additional mortality risks (Peterson et al., 2016).

Males and middle-aged patients with nonfatal overdoses were at greater risk of opioid-related death than their female and younger adult counterparts. These patterns recreate, within nonfatal opioid overdose populations, broad drug overdose mortality patterns seen in the general population (Rudd et al., 2016) and in the population of adults who use opioids (Blanco et al., 2016). As adults with problematic opioid use age, some develop complex health problems that predispose them to fatal overdose.

Most patients with nonfatal overdoses filled opioid prescriptions in the prior six months. Nearly three-quarters of these patients had been treated for non-cancer chronic pain, and over one-third had recently been diagnosed with a substance use disorder. These patients had higher risk of subsequent fatal opioid overdose than their counterparts who had not filled opioid prescriptions in the six months prior to their nonfatal overdose. Among those who filled opioid prescriptions, clinical diagnosis of substance use disorders and nonfatal heroin overdoses were strong predictors of subsequent fatal overdose. Associations between clinically recognized substance use disorders and fatal opioid overdose among patients receiving opioid prescriptions underscore the importance of coordinating general medical and substance use treatment of this patient population to help ensure safe pain management (Blanco et al., 2016). The relationship between risks associated with prescribed opioids and those associated with illicitly-obtained drugs is complex, and many individuals with overdoses may use both.

During the first 12 months following nonfatal opioid overdose, nearly one in five (18.9%) patients had a subsequent overdose. This percentage substantially exceeds prior estimates of repeat overdose from a large US all payer sample of patients with opioid overdoses presenting to emergency departments (7%) (Hasegawa et al., 2014) and a US sample of commercially insured patients treated in inpatient or emergency settings (7%) (Larochelle et al., 2016). The high risk of repeat overdose in the present sample may be partially explained by socioeconomic disadvantages (Nandi et al., 2006) and the high prevalence of health problems (Li et al., 2017; Ku et al., 2016; MACPAC, 2015) experienced by patients in the Medicaid program which is the primary insurer of people with low income in the US. In the present analysis, opioid overdoses initially treated in outpatient settings also accounted for nearly one-third of the sample and these patients were at higher risk of repeated overdose than overdoses treated in emergency or inpatient settings. In evaluating the public health impact of opioid overdose, it is important to consider all settings in which patients present.

This study has several limitations. First, our study is based on data from 2001 to 2007. Since then there have been changes in opioid and other drug use patterns; access to naloxone reversal; use of medication assisted treatment, including introduction of extended-release naltrexone; and new risks associated with fentanyl-contaminated heroin (Kandel et al., 2017). These changes have likely affected risks of opioid overdose deaths. Second, there is a potential for misclassification of opioid-related overdoses and deaths. Many overdoses do not present for medical care (Merchant et al., 2006) and some fatal opioid overdoses may not be captured on death certificates while others may be recorded as unspecified drug poisoning (Rhum, 2017). Third, different results might have been obtained if privately insured and uninsured patients with opioid overdoses were studied. Fourth, the analysis focused on characteristics that can be identified at initial overdose and does not examine effects of interventions following initial overdose. Fifth, residual confounding may influence the magnitude of associations between risk factors and outcomes. Finally, we have no means of measuring opioids acquired from illicit sources or ensuring that patients took medications as prescribed.

5. Conclusions

Adults who survive an opioid overdose are at high risk of subsequent fatal opioid overdose. Despite this risk, critical gaps exist in community treatment of opioid use disorder. In the six months preceding initial overdose, a substantially higher percentage of the patients were diagnosed with an opioid use disorder (15.9%) than received medication assisted treatment (2.4%). Following nonfatal opioid overdose, a substantial proportion of patients fill prescriptions for opioids (Frazier et al., 2017; Larochelle et al., 2016) and only a minority initiate medication-assisted treatment (Frazier et al., 2017). Beyond stabilizing patients following nonfatal opioid overdoses, clinicians have opportunities to engage patients following overdose recovery in medication-assisted treatment. A recent clinical trial demonstrated that initiating buprenorphine in the emergency department paired with linkage to ongoing treatment in primary care increased engagement of opioid dependent patients and lowered short-term use of illicit opioids (D’Onofrio et al., 2017). In light of persistent risks throughout at least a year following nonfatal opioid overdose, clinical priority should be given to interventions that help ensure patients are engaged and maintained in substance use treatment following nonfatal opioid overdoses.

Supplementary Material

Role of the funding sources

This research was supported by R01 DA019606 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, R18 HS023258 and U19 HS021112 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The funders had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. The views and opinions expressed in this submission are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the U.S. government.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.004.

References

- Blanco C, Wall MM, Okuda M, Iza M, Olfson M, 2016. Pain as a predictor of opioid use disorder in a nationally representative sample. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AS, Logan JE, Ganoczy D, Dowell D, 2016. A detailed exploration into the association of prescribed opioid dosage and overdose deaths among patients with chronic pain. Med. Care 54, 435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC), 2016. WONDER: Underlying causes of death, 1999–2015. [WWW Document]. (Accessed 28 November 2017). https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html.

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, 2014. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran G, Gordon AJ, Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Frazier W, Lobo C, Chang CH, Zheng P, Donohue JM, 2017. An examination of claims-based predictors of overdose from a large medicaid program. Med. Care 55, 291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Mills KL, Ross J, Teeson M, 2011. Rates and correlates of mortality amongst heroin users: findings from the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS), 2001–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 115, 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Buceelo C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Ali H, Hickman M, McLaren J, 2010. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction 106, 32–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA, 1992. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 45, 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Busch SH, Owens PH, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA, 2017. Emergency department?initiated buprenorphine for opioid dependence with continuation in primary care: outcomes during and after intervention. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 32, 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration, 2015. National drug threat assessment summary, 2014. Pub no. DEA-DCT-CIR-002–15. Department of Justince, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, Weisner CM, Silverberg MJ, Campbell CI, Psaty BM, Von Korff M, 2010. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier W, Cochran G, Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Gordon AJ, Chang CH, Donohue JM, 2017. Medication-assisted treatment and opioid use before and after overdose in Pennsylvania medicaid. JAMA 318, 750–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Brown DFM, Tsugawa Y, Camargo CA, 2014. Epidemiology of emergency department visits for opioid overdose: a population-based study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 89, 462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall JT, Sprague JE, 2017. The pharmacology and toxicology of the “holy trinity.”. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 130, 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD, 2001. A 33-year follow-up of narcotic addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DJ, McCarthy EP, Stevens JP, Mukamal KJ, 2017. Hospitalizations, costs and outcomes associated with heroin and prescription opioid overdoses in the United States 2001–12. Addiction 112, 1558–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ, 2013. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA 309, 657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler P, Wall M, 2017. Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug. Alc. Depend. 178, 501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelty E, Hulse GG, 2017. Fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose in opioid dependent patients treated with methadone, buprenorphine, or implant naltrexone. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Jackson Bloom J, Harocopos A, Treese M, 2012. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. Int. J. Drug Policy 23, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF, 2016. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 164, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Chinn CC, Fernandes R, Wang CMB, Smith MD, Ozaki RR, 2017. Risk of diabetes mellitus among medicaid beneficiaries in Hawaii. Prev. Chron. Dis. 14, E116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC), 2015. Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP. Chapter 4: Behavioral health in the Medicaid program–people, use, and expenditures. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. [WWW Document]. (Accessed 22 May 2018). https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Gelabert P, Guarino H, Jessell L, Teper A, 2015. Injection and sexual HIV/HCV risk behaviors associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids among young adults in New York City. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 48, 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant RC, Schwartzapfel BL, Wolf FA, Li W, Carlson L, Rich JD, 2006. Demographic, geographic, and temporal patterns of ambulance runs for suspected opiate overdose in Rhode Island, 1997–2012. Subst. Use Misuse 41, 1209–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies C, 2013. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Review. [WWW Document]. http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DataReview/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Naeger S, Mutter R, Ali MM, Mark T, Hughey L, 2016. Post-discharge treatment engagement among patients with an opioid-use disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 69, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi AK, Galea S, Ahern J, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D, Tardiff K, 2006. What explains the association between neighborhood-level income inequality and the risk of fatal over dose in New York City? Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 662–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy KM, Banta-Green CJ, Kingston S, Hanrahan M, Merrill JO, Coffin PO, 2012. “Hooked on” prescription-type opiates prior to using heroin: results from a survey of syringe exchange clients. J. Psychoactive Drugs 44, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AB, Gladden RM, Delcher C, Spies E, Garcia-Williams A, Wang Y, Halpin J, Zibbell J, McCarty CL, DeFiore-Hyrmer J, DiOrio M, Goldberger BA, 2016. Increases in fentanyl-related overdose deaths - Florida and Ohio, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Rep. 65, 844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister GJ, Burkes RM, Guinn B, Steele J, Kelley RR, Wiemken TL, Saad M, Ramirez J, Cavallazzi R, 2016. Opioid overdose leading to intensive care unit admission: epidemiology and outcomes. J. Crit. Care 35, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhum CJ, 2017. Geographic variation in opioid and heroin involved drug poisoning mortality rates. Am. J. Prev. Med. 53, 745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risser D, Honigschnabl S, Stichenwith M, Pfudl S, Sebald D, Kaff A, Bauer G, 2001. Mortality of opiate users in Vienna, Austria. Drug Alcohol Depend. 64, 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L, 2016. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Rep. 65, 1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A, 2012. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med. Care 50, 1109–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoove MA, Dietze PM, Jolley D, 2009. Overdose deaths following previous non-fatal heroin overdose: record linkage of ambulance attendance and death registry data. Drug Alcohol Rev. 28, 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unick GJ, Ciccarone D, 2017. US regional and demographic differences in prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose hospitalizations. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti AJ, Santos GM, Lemos NP, 2015. Opioid overdose deaths in the City and County of San Francisco: prevalence, distribution, and disparities. J. Urban Health 92, 758–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barret ML, Steiner CA, Bailey MK, O’Malley L, 2017. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009–2014. Statistical Brief #219, December 2016. [WWW Document]. . https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik NC, Huebner WW, Jorgensen G, 2010. Strategies for using the national death index and the social security administration for death ascertainment in large occupational cohort mortality studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.