Abstract

Objective:

To describe patterns in the enforcement of the US Food and Drug Administration’s current compliance check program.

Methods:

Data on retail violation rates (RVR) resulting from compliance checks were analyzed. Novel methods were developed to quantify violations and unify data on retail location and violation type.

Results:

As of July 2013, 42 states and 3 US territories conducted compliance checks. Ninety-six percent of warning letters and 100% of Civil Monetary Penalties addressed sales to minors. RVRs varied significantly over time (OR = 1.15) and between states (ICC = 0.18).

Conclusions:

The compliance checks database makes it possible to examine how retail enforcement is unfolding over time and place. Results reveal an emphasis on youth access violations, presenting opportunities for research on regulations designed to reduce youth access.

Keywords: Food and Drug Administration, point-of-sale, compliance checks, Synar, retail violation rate

Passage of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) in June 2009 provided the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with a number of tools to prevent and reduce tobacco use in the United States (US). A key feature of this law is that it granted the FDA enforcement authority to ensure appropriate implementation down to the level of the tobacco retailer.1 The FSPTCA imposed several rules with direct effects on the retail environment, including banning flavored cigarettes, requiring larger warning labels for smokeless tobacco products,2 prohibiting marketing of cigarettes as “light,” “low,” or “mild,”2 and reissuing the 1996 FDA rules restricting sales and tobacco product advertising and marketing to youth.3

Similar to the protocol established and implemented by the FDA from 1997 to 2000,4 the FDA began issuing state enforcement contracts to conduct compliance checks of tobacco retailers under the Enforcement Action Plan for Promotion and Advertising Restrictions in June 2010.5 Retailers whose compliance checks result in a violation of one or more federal laws and regulations generally receive warning letters for first-time violations, with the FDA issuing civil money penalties for violations found on subsequent inspections.6 Whereas warning letters are considered the FDA’s “principal means of achieving prompt voluntary compliance,”5 administrative legal action against a retailer in the form of a Civil Monetary Penalty Complaint can result in the imposition of a fine of up to $15,000 for a single violation with a maximum of $1,000,000 for all violations adjudicated in a single proceeding.5

The growing database of FDA tobacco retailer compliance check outcomes provides a longitudinal record of federal point-of-sale tobacco control policy implementation, as well as a framework to evaluate and disseminate information about its effectiveness. The FDA conducted 191,294 compliance checks between 1997 and 2000,4 and an interactive Web portal called “Compliance Checker” was established that tobacco control stakeholders could use to access information about the results of the compliance check program.4 A similar number of compliance checks (189,594) were completed as of July 31, 2013, and 41 of the 42 states conducting compliance checks between 2010 and 2013 also were doing so between 1997 and 2000. The similarity of timing (3 years), location, and number of inspections conducted provides an important opportunity to contrast the results of these FDA inspection programs conducted over a decade removed. The fact that state-based Synar inspections also were being conducted during these windows of time provides an additional point of reference regarding the illicit sale of tobacco to youth.

During the first period in which the 1996 FDA rules were implemented, studies documented retailer compliance at the state and national levels, identified variables associated with tobacco sales to youth, and recommended best practices based on lessons learned.4,8 Raw data on compliance checks completed since 2010 are publicly available for download from an FDA website,7 as well as a map feature that can display local compliance check outcomes.7 Yet, at the 5-year anniversary of the FSPTCA, few studies have examined the retailer compliance with tobacco marketing and sales restrictions. One study reported high retailer compliance in 2 neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio9 and one in North Carolina;10 in addition, a report from the FDA highlights the agency’s enforcement activities from 2009 through September 2013.11

Documenting implementation of the FDA Enforcement Action Plan for Promotion and Advertising Restrictions is an important metric for evaluating the state and national impact of the FSPTCA and guiding future regulatory policy. Whereas the dates of enactment of these laws are well publicized, examination of the fidelity with which they have been implemented down to the local level is needed to assess their true impact on tobacco marketing. Nationwide enforcement of the law is unfolding dynamically over time and place, as compliance patterns interact with local policy environments and the evolving landscape of product marketing and availability. Systematic examination of this complex process presents a formidable research challenge. Similar challenges have made identification of factors driving compliance with state-level Synar youth access laws difficult,12,13 with some work demonstrating that illicit sales violations are associated with a range of factors, including tobacco outlet retail category, geographic location and marketing practices, as well as the surrounding socio-contextual environment.14,15 Despite these similar challenges, there has been no research to date comparing FDA and Synar compliance checks and how they were implemented.

The purpose of this study was to provide detailed information on the FDA’s retailer compliance checks at the national and state levels over the first 3 years following enactment of the FSPTCA, including description of patterns in retailer violations by violation type, and assessment of temporal and spatial trends in these data. Given the similarity between the current FDA inspection program and the work conducted by both the FDA and Synar programs between 1997 and 2000, this paper also compares current and historic retailer violation rates between the FDA and Synar compliance check programs.

METHODS

FDA Compliance Check Program

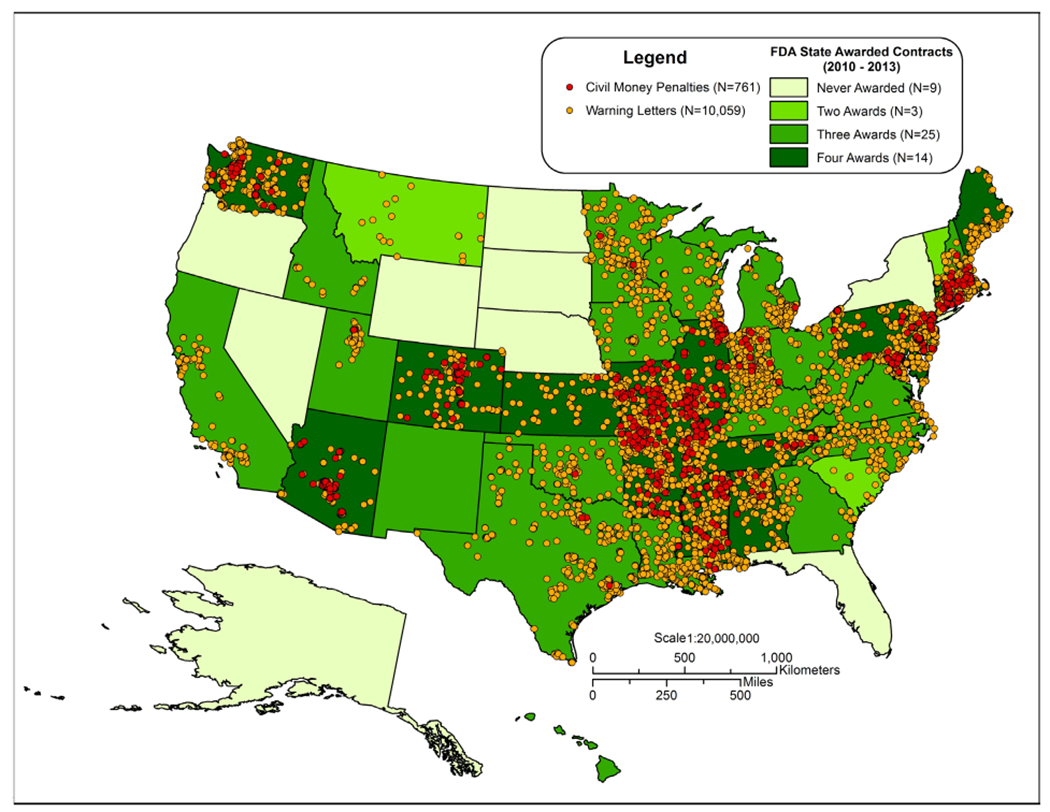

The FSPTCA authorizes the FDA to contract with states, US territories, and Indian tribes to assist with compliance and enforcement activities. Since 2010, 42 states (including the District of Columbia) and 3 US territories have received state contracts for over $91 million to conduct retailer compliance checks.16 Enforcement contracts were awarded to a total of 15 states in fiscal year 2010, 37 states in 2011, 40 states in 2012, and 41 states in fiscal year 2013 (Figure 1). Four states (North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Wyoming) had not received a contract by July, 2013, either as part of the present program or the FDA compliance check program run between 1997-2000.4 Another group of 5 states (Alaska, Florida, Nebraska, Nevada, New York) contracted with the FDA during 1997-2000, but did not hold an FDA contract by July 2013. The FDA issued another request for proposals in 2013 to provide additional states, territories, or Indian tribes the opportunity to work with the FDA on compliance checks,17 along with a separate request for proposals from private firms to conduct compliance checks in the 9 states and other jurisdictions that have not yet established a contract with FDA,18 similar to the supplemental program run by the University of Idaho to conduct inspections in North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, and Wyoming between 1997 and 2000.4 Alaska, Florida, Louisiana, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming, and the US Virgin Islands all were awarded contracts in 2014 to a third-party named Information Systems and Networks Corporation. Of these states, Louisiana and Utah previously held an FDA contract that subsequently expired.

Figure 1.

FDA State Contract Awards and National Distribution of Warning Letters and Civil Monetary Penalties, October, 2010 – July 31, 2013

FDA compliance check efforts are supported by a strategic partnership between the FDA youth-sales inspection program and the existing Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA) Synar program.19 The Synar program supports enforcement of a youth tobacco-sales prohibition in all 50 States and 9 jurisdictions (including Washington, DC) via unannounced inspections across a representative sample of tobacco outlets. The strategic partnership between FDA and SAMHSA allows groups holding contracts from both inspection programs to coordinate their efforts, and in some circumstances, apply results of inspections toward fulfillment of the reporting requirements of both agencies.19

FDA compliance check inspections include supervised youth purchase attempts that are based on methods similar to ones used by Synar inspection teams. Accompanied by program staff and a police officer who wait outside, a volunteer under age 18 enters each randomly pre-selected store and attempts to purchase a pack of cigarettes. In addition, FDA compliance check officials use mobile devices to document compliance with the current set of federal regulations being actively enforced by FDA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Federal Regulations Related to Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco, Number of Warning Letters and Number of Civil Money Penalties Citing Violations, by Type and Year – United States, October 12, 2010 to July 31, 2013

| Federal regulation | Description | Number of warning letters (Civil Money Penalties) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total | ||

| 1140.10 | Each manufacturer, distributor, and retailer is responsible for ensuring that the cigarettes or smokeless tobacco it manufactures, labels, advertises, packages, distributes, sells, or otherwise holds for sale comply with all applicable requirements under this part. | 24 (0) |

407 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

431 (0) |

| 1140.14(a) | No retailer may sell cigarettes or smokeless tobacco to any person younger than 18 years of age. | 24 (0) |

1165 (6) |

4091 (360) |

2560 (280) |

7840 (646) |

| 1140.14(b)(1) | Except as otherwise provided in 1140.16(c)(2)(i) and in paragraph (b)(2) of this section, each retailer shall verify by means of photographic identification containing the bearer’s date of birth that no person purchasing the product is younger than 18 years of age. | 22 (0) |

778 (5) |

2916 (220) |

1598 (187) |

5314 (412) |

| 1140.14(b)(2) | No such verification is required for any person over the age of 26. | 22 (0) |

779 (0) |

209 (0) |

0 (0) |

1010 (0) |

| 1140.14(c) | Except as otherwise provided in 1140.16(c)(2)(ii), a retailer may sell cigarettes or smokeless tobacco only in a direct, face-to-face exchange without the assistance of any electronic or mechanical device (such as a vending machine). | 0 (0) |

147 (1) |

310 (26) |

144 (21) |

601 (48) |

| 1140.14(d) | No retailer may break or otherwise open any cigarette or smokeless tobacco package to sell or distribute individual cigarettes or a number of unpackaged cigarettes that is smaller than the quantity in the minimum cigarette package size defined in 1140.16(b), or any quantity of cigarette tobacco or smokeless tobacco that is smaller than the smallest package distributed by the manufacturer for individual consumer use. | 0 (0) |

19 (0) |

77 (9) |

76 (9) |

172 (18) |

| 1140.14(e) | Each retailer shall ensure that all self-service displays, advertising, labeling, and other items, that are located in the retailer’s establishment and that do not comply with the requirements of this part, are removed or are brought into compliance with the requirements under this part. | 0 (0) |

344 (1) |

138 (34) |

0 (1) |

482 (36) |

| Self-service displays | 0 | 180 | 106 | 0 | 286 | |

| Advertising | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |

| Labeling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other items | 0 | 157 | 31 | 0 | 188 | |

| 1140.16(b) | Except as otherwise provided under this section, no manufacturer, distributor, or retailer may sell or cause to be sold, or distribute or cause to be distributed, any cigarette package that contains fewer than 20 cigarettes. | 0 (0) |

10 (0) |

4 (1) |

2 (1) |

16 (2) |

| 1140.16(c) | Vending machines, self-service displays, mail-order sales, and other “impersonal” modes of sale | 0 (0) |

183 (1) |

688 (77) |

425 (55) |

1296 (133) |

| 1140.16(d)(1) | Except as otherwise provided under this section, no manufacturer, distributor, or retailer may sell or cause to be sold, or distribute or cause to be distributed, any cigarette package that contains fewer than 20 cigarettes. | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0) |

1 (1) |

4 (1) |

| 1140.34(b) | No manufacturer, distributor, or retailer may offer or cause to be offered any gift or item (other than cigarettes or smokeless tobacco) to any person purchasing cigarettes or smokeless tobacco in consideration of the purchase thereof, or to any person in consideration of furnishing evidence, such as credits, proofs-of-purchase, or coupons, of such a purchase. | 0 (0) |

10 (0) |

10 (0) |

0 (0) |

20 (0) |

|

| ||||||

| Total |

24

(0) |

1734

(8) |

5122

(415) |

3169

(337) |

10049

(759) |

|

FDA Compliance Check Data

The FDA continuously updates its compliance check database, making all new data available for download once a month. In 2010, Legacy established a geographic information system (GIS) platform for internal monitoring of the FDA retail compliance checks and outcomes. The data are imported as comma-separated values to the Legacy GIS platform from the FDA Center for Tobacco Products website.7 Each line of data describes either a single compliance check or a notification of a Civil Monetary Penalty. Both civil monetary penalties and compliance checks that identified one or more violations are associated with a URL link to a related document describing the time, date, place, and details of all violations observed. Unlike these violation documents, the raw data do not include a unique identifier for each store, nor the date the inspection was completed; only the date that a decision was made about the inspection is provided. To track repeat inspections, each line of data was read into a separate record and unique store names were created from the name and address provided.

Compliance Check Warning Letter Documents

Warning letters issued to retailers following their first compliance check violation are provided as a URL linking the data record to an HTML warning letter. All links were validated and manually corrected when necessary. Once validated, a custom script was used to automatically download each HTML document. Once each warning letter was downloaded, a customized text analysis script was used to extract dates and statutes violated. Several variations of this script were developed to accommodate individual styles of bullet points, paragraphs and phrasing, apparently due to manual production of each letter via word processing software.

Compliance Check Civil Monetary Penalty Documents

Civil Money Penalties are issued after a second compliance check violation, but not necessarily for repeated infringement of the same statute(s). Civil Monetary Penalty letters often included details on statute violations identified at the first violation (ie, in the initial warning letter), as well as violations that were observed at subsequent compliance checks. This required that each Civil Monetary Penalty document be scanned for statute violations, to differentiate between repeat versus new offenses noted only in the Civil Monetary Penalty document. Unlike the URL links to the warning letters, Civil Monetary Penalty documents are provided as PDF files. A script was written to download these files and convert the PDF into a text document, extracting relevant data via text analysis similar to that used for the warning letters. In addition to the data collected from the warning letter files, data extracted from Civil Monetary Penalty documents included recent violations and the amount of the fine.

Violations of Statute 1140.14e

Any warning letter that referenced a violation of statute 1140.14e required further review, as multiple violation subtypes fell under this statute (Table 1). The many combinations of the violation subtypes that could be found in any single letter precluded development of a reliable pattern-matching script to extract this information. Thus, each letter needed to be reviewed by a person who could identify each of the specific violation subtypes listed in the letter under 1140.14e (ie, advertising, labeling, and other items; Table 1). To accomplish this, a custom crowdsourcing platform based on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk system was employed.20 A pattern-matching script highlighted text relevant to 1140.14(e) within these letters and this text was displayed to multiple independent raters who were each asked to identify the violation subtypes cited in the text, with check-boxes for each subtype provided to the right of the relevant passage. This task was run repeatedly until there was at least 90% consensus among the raters as to the subtype.

Geographic Location of Each Compliance Check

The addresses for all FDA compliance checks (N = 189,594) were batch geocoded by utilizing the street address locator in Environmental Systems Research Institute’s (ESRI) ArcGIS Online geocoding services.21 A batch geocoding match was obtained for approximately 90% (N = 170,963) of the FDA compliance check addresses. All tied and unmatched addresses were manually geocoded following the batch geocoding results to ensure the completeness of the spatial dataset. To ensure the spatial accuracy of the dataset, all matched addresses that received a score < 85 (N = 149) during the batch geocoding processes were ortho-verified to ensure their spatial accuracy. Any addresses that were not accurately located (N = 226) were ortho-rectified to their correct spatial location. The final spatial dataset of FDA compliance checks was imported into the GIS database.

The data used in these analyses is publicly available via the Legacy Tobacco Viewer, a tool that allows for the examination of changes in FDA compliance check inspections over time. The tool is integrated with Legacy’s GIS portal, which allows users to explore how compliance check inspections may be associated with a range of other factors. Users can quickly zoom to their local area and bookmark their preferences as they overlay various data sources and visualize the results.22

Statistical Analyses

Following creation of the comprehensive database, bivariate analyses were conducted to examine implementation of compliance checks over time and place, the number of compliance checks with no violation, warning letters issued, and Civil Money Penalties issued over time, and the number of warning letters and Civil Money Penalties issued by violation type. Following established reporting standards for the SAMHSA Synar program,23 we report the retail violation rate (RVR) by state, ie, the proportion of all inspections conducted that produced a violation. Mixed-effect logistic regression was used to investigate the link between the probability of an FDA compliance check violation (given an inspection), the year the inspection was completed, and the state in which the inspection took place, accounting for clustering of inspections within states and over time. Mean comparison t-tests were used to evaluate factors that only vary at the state-level, such as the overall retail violation rate observed by FDA and Synar inspectors in each state.

RESULTS

Compliance Check Outcomes

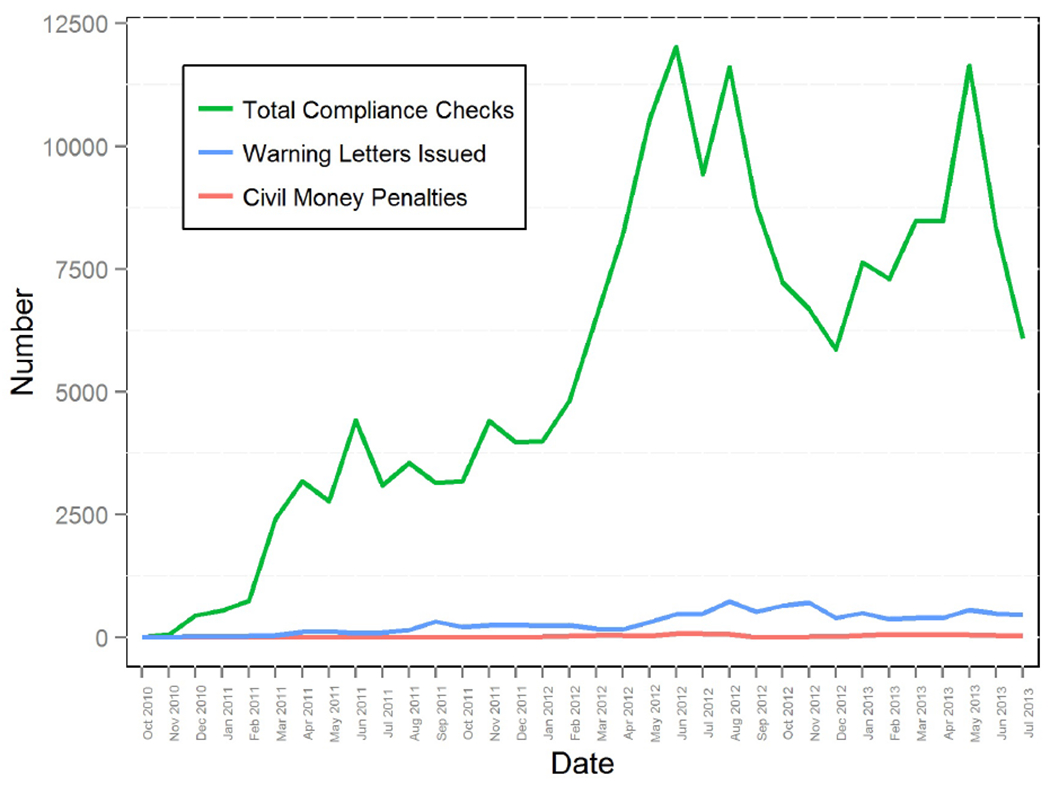

As of July 31, 2013, FDA enforcement officers had conducted 189,594 compliance checks (Figure 2). FDA compliance checks have resulted in 10,059 warning letters issued to retailers for first-time violations and 761 Civil Monetary Penalty notifications for subsequent violations. Among the 10,059 warning letters that have been issued, 96% (N = 9691; Figure 1) of violations cited were related to prohibition of sales to minors (Table 1). Table 1 presents a description of the tobacco-related federal regulations cited in the current sample of warning letters and the number of violations of each type. Of the retailers receiving warning letters, the predominant violations were for sales to youth (1140.14(a) and 1140.14 (b)(1)) and failure to sell tobacco products in a face-to-face exchange (1140.14(c)). There were 35 warning letters citing violation of the ban on flavored cigarettes and 83 letters citing violation related to modified risk tobacco products, including the ban on “light,” “low,” and “mild” pack descriptors. Of the 761 Civil Monetary Penalties issued, 100% included violations for underage sales.

Figure 2.

Number of Compliance Checks, Warning Letters, Civil Monetary Penalties over Time

Retail Violation Rates

Since the inception of the FDA compliance check program in 2010, the aggregated retail violation rate (RVR) has been 6% (SD = 0.05; Median = 0.04), substantially lower than the 26% RVR observed between October 1997 and March 2000, when FDA conducted about the same number of compliance checks (N = 191,294) across 48 states, including all but one (Wisconsin) of the 42 that are conducting compliance checks under the current program.4

As was the case in 1997-2000,4 both the frequency of inspections and RVR have varied significantly from state to state (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, RVRs have changed significantly each year since 2010, the result of an expanding number of states conducting inspections, along with slightly different inspection methods employed within each state. Specifically, results reveal significant variation in RVR over time and among states, such that the odds that a compliance check results in a violation has increased by 15% (OR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.11-1.18) over each the first 4 years, with differences in RVR among states accounting for 18% of the total variation (ICC = 0.18; 95% CI:0.12-0.26). These findings suggest that whereas the RVR in most states is growing, RVR in others is stable or in some cases declining, although the overall pattern is complex and difficult to characterize with predictive models alone.

Table 2.

Violations by State and by Type, October 12, 2010 to July 31, 2013

| (a) Labeling and advertising | (b) Underage Sales | Both (a) & (b) | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%; RVR) |

| AL | 0 (0) | 285 (96.94) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.06) | 294 (3.33) |

| AR | 0 (0) | 353 (95.15) | 0 (0) | 18 (4.85) | 371 (7.83) |

| AZ | 0 (0) | 326 (93.14) | 0 (0) | 24 (6.86) | 350 (11.73) |

| CA | 0 (0) | 108 (93.91) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.09) | 115 (1.89) |

| CO | 0 (0) | 436 (92.18) | 1 (0.21) | 36 (7.61) | 473 (8.75) |

| CT | 0 (0) | 602 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 602 (14.37) |

| DC | 0 (0) | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 70 (10.09) |

| DE | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (2.17) |

| GA | 0 (0) | 51 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 51 (3.01) |

| IA | 0 (0) | 55 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 55 (1.31) |

| ID | 0 (0) | 13 (86.67) | 0 (0) | 2 (13.33) | 15 (1.8) |

| IL | 2 (0.38) | 493 (94.63) | 5 (0.96) | 21 (4.03) | 521 (13.64) |

| IN | 0 (0) | 506 (99.41) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.59) | 509 (3.9) |

| KS | 0 (0) | 93 (88.57) | 1 (0.95) | 11 (10.48) | 105 (1.89) |

| KY | 0 (0) | 93 (97.89) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.11) | 95 (1.91) |

| LA | 0 (0) | 368 (99.19) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.81) | 371 (5.32) |

| MA | 0 (0) | 520 (96.12) | 3 (0.55) | 18 (3.33) | 541 (4.34) |

| MD | 0 (0) | 259 (93.84) | 0 (0) | 17 (6.16) | 276 (5.44) |

| ME | 0 (0) | 77 (92.77) | 0 (0) | 6 (7.23) | 83 (0.95) |

| MI | 0 (0) | 395 (99.75) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.25) | 396 (11.73) |

| MN | 0 (0) | 236 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 236 (4.1) |

| MO | 1 (0.08) | 1234 (95.51) | 2 (0.15) | 55 (4.26) | 1292 (18.31) |

| MS | 0 (0) | 547 (93.19) | 0 (0) | 40 (6.81) | 587 (4.53) |

| MT | 0 (0) | 19 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (3.56) |

| NC | 0 (0) | 179 (99.44) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.56) | 180 (7.25) |

| NH | 0 (0) | 55 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 55 (7.61) |

| NJ | 0 (0) | 601 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 601 (8.43) |

| OH | 0 (0) | 50 (94.34) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.66) | 53 (7.89) |

| OK | 0 (0) | 100 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (4.49) |

| PA | 0 (0) | 541 (94.09) | 0 (0) | 34 (5.91) | 575 (4.34) |

| RI | 0 (0) | 123 (97.62) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.38) | 126 (3.56) |

| SC | 0 (0) | 23 (95.83) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.17) | 24 (0.93) |

| TN | 2 (1.15) | 164 (94.25) | 2 (1.15) | 6 (3.45) | 174 (4.29) |

| TX | 0 (0) | 363 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 363 (5.32) |

| UT | 0 (0) | 94 (98.95) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.05) | 95 (3.74) |

| VA | 0 (0) | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50 (6.59) |

| WA | 0 (0) | 766 (97.08) | 1 (0.13) | 22 (2.79) | 789 (9.51) |

| WI | 0 (0) | 82 (98.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 83 (11.22) |

| WV | 0 (0) | 87 (94.57) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.43) | 92 (4.76) |

|

| |||||

| Total | 5 (0.05) | 10450 (96.58) | 15 (0.14) | 350 (3.23) | 10820 (6.05) |

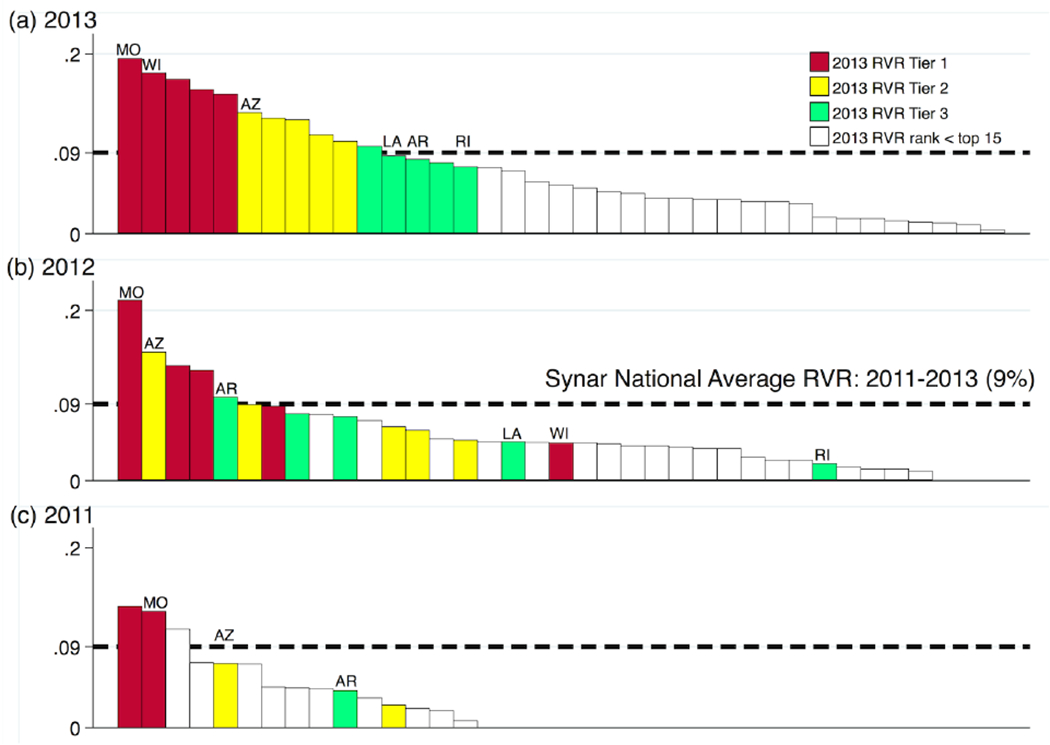

Figure 3 illustrates some of these trends, presenting the distribution of state RVRs across 2011-2013, the national average Synar RVR for 2011-2013,23 and highlighting groups of states with the highest RVRs in 2013. Figure 3 does not include 2010 because only one state (Mississippi) conducted enough compliance checks in 2010 (N = 506) to register an RVR (4.9%). Figure 3 excludes annual RVRs that are based on fewer than 50 compliance checks in each year, as in the small number of cases this occurred (eg, N = 5 in 2012) it was due to either a very small number of privately conducted inspections in states that do not currently have an FDA contract, or to the early initiation of a program recently awarded a contract, and thus, the small samples do not provide a representative estimate of what would have been the annual RVR for that state.

Figure 3.

FDA State Retailer Violation Rates (RVR): 2011-2013

Figure 3 presents 3 groups of 5 states that are categorized into RVR “tiers” corresponding to their relative ranking in 2013 RVR Tier 1 is comprised of the 5 states with the highest RVR in 2013, Tier 2 is comprised of states ranked 6 through 10, and Tier 3 is comprised of states ranked 11 through 15. This approach makes it possible to visualize the degree to which the states with high relative RVRs were stable over time. Tier 1 (red bars) includes Missouri, Wisconsin, Connecticut, Michigan, and Illinois; Tier 2 (yellow bars) includes Arizona, Ohio, Washington, North Carolina, and Maryland; and Tier 3 (green bars) includes New Jersey, Louisiana, Arkansas, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. Hollow white bars in Figure 3 correspond to the remaining states with lower relative RVR in 2013. Working backward from each of the 3 FDA RVR tiers observed in 2013 (Panel a), Figure 3 visualizes the presence of states within each tier among the RVR distributions observed in 2012 (Panel b) and 2011 (Panel c). The fact that 10 of the 15 states conducting compliance checks in 2011 were not included among the 2013 RVR tiers indicates that these states either maintained a stable, relatively lower RVR, or in some cases had a reduced RVR (eg, Colorado, ranked third with an RVR of 10.9% in 2011). Other states maintained an elevated RVR across years (eg, Missouri), indicated by red bars in all 3 panels of Figure 3, or an increasing RVR (eg, Arizona and Arkansas), which kept them among the top RVR tiers even as new state programs were launched.

Because over 95% of FDA compliance violations have been related to sales to minors, it is instructive to consider contemporary Synar rates. Comparing the overall FDA RVR to the corresponding Synar RVR reveals that they were essentially the same between 1997 and 2000, when the aggregated Synar RVR was observed to be 26.5%; the 2010-2013 FDA RVR of about 6% is somewhat lower than the Synar RVR, which has consistently hovered around 9% for the last 3 years.23 Using the national 2010-2013 Synar RVR as a reference point, Figure 3 indicates that the number of states with an FDA RVR greater than or equal to the national Synar RVR increased from 3 in 2011, to 5 in 2012, and then to 11 in 2013. A corresponding paired mean comparison analysis indicated that annual Synar and FDA RVRs were not equivalent within states (p < .05).

DISCUSSION

Five years after implementation of the FSPTCA, this is the first study to provide national and state-level data on the status of the FDA retail compliance check program. As of 2013, 41 states held contracts to conduct retailer compliance checks; this increased to 43 (including the District of Columbia) states in 2014.16 In contrast to the initial implementation of FDA compliance checks from 1997 through 2000 that focused exclusively on age identification checks and underage sales, the FDA’s current program extends to enforce recent rules, including the ban on flavored cigarettes and “light,” “low,” or “mild” pack descriptors. Results indicate that the nationwide FDA RVR is relatively low (6% of all inspections), and that the vast majority of warning letters are related to youth access violations (96% of all violations), rather than violations of the rules put in place after passage of the FSPTCA in 2009. Fittingly, the RVRs observed during both FDA compliance check programs have paralleled those observed by the national Synar program, although this correspondence does not appear at the state-level, where FDA and Synar RVRs are often significantly different.

Overall, FDA RVRs have increased each year of the program, but RVRs varied significantly from state-to-state, and it appears that the rise in overall RVR has been driven by increases among those states that were already observing relatively higher RVRs (Figure 3). Looking at the absolute number of bars present in each year, Figure 3 makes it clear that the number of states completing compliance checks and observing violations jumped significantly between 2011 (Figure 3, Panel (c); N = 15) and 2012 (Figure 3, Panel (b); N = 34), but that this number only increased slightly in 2013 (Figure 3, Panel (a); N = 37). Almost all 15 states within the higher RVR tiers in 2013 were also among those with a relatively higher RVR in 2012, and most observed a considerable increase in RVR from 2012 to 2013. This indicates that the overall rise in the 2013 RVR was due to increasing RVR among states already observing higher rates, and that most states with lower RVR in 2011 and 2012 maintained lower rates in 2013. A small number of noteworthy exceptions witnessed more significant jumps in RVR between 2012 and 2013; for example, the RVRs in Wisconsin (2012 RVR = 4.4%) and Rhode Island (2012 RVR = 1.9%) rose significantly in 2013, moving both of these states within Tier 1 (WI RVR = 17.8%) and Tier 3 (RI RVR = 7.4%), respectively (Figure 3).

The FDA’s point-of-sale compliance and enforcement database represents a valuable resource for tobacco control stakeholders, though challenges remain in making maximal use of these data. First, it is difficult to enumerate and identify tobacco retailers without a central national database or via state-level tobacco licensing.24 Second, the presentation of information on violations within the warning letters or Civil Money Penalty documents limits the ability of casual users to be able to document trends in the types of violations occurring from the national to the local level, or even at a single establishment. Finally, specific violation types include multiple subtypes not codified in the warning letter (ie, 1140.14(e)). Novel methods developed in this study address all of these issues. Geocoding of the retailer data, generation of an automated process to extract data on violations and civil money penalties from text files, and crowdsourcing the classification of the 1140.14(e) violations made it possible to merge these complex data into a single database.

Limitations

A limitation on the inference that can be drawn from analysis of FDA youth sales inspections is that violation rates are compiled at the level of the retailer, not the individual purchase attempt level, so the data cannot be used to estimate actual rates of underage tobacco sales. Actual underage sales would need to account for highly variable sales volume levels between retailers, as well as self-selection effects as youths seek out outlets known to sell to minors. Similarly, compliance check outcome data are not necessarily representative of changes in point-of-sale practices over time; rather, they reflect the gradual roll-out of FDA enforcement protocols and priorities. Moving forward, agent-based models currently under development will make it possible to simulate population dynamics and consumer movement patterns, as well as the point-of-sale product and marketing landscape, and thus address the link between compliance check inspections, point-of-sale practices, and youth access outcomes.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

Although the dates of enactment of the statutes associated with the FDA Enforcement Action Plan for Promotion and Advertising Restrictions have been well publicized, the dynamic way these laws have been implemented down to the local level has been far less clear. The database of FDA tobacco retailer compliance checks provides documentation of this complex process, making it possible to disseminate information about the way the law is unfolding over time and place. This is important for many reasons; chief among them is that it provides the FDA, the US Congress, and other stakeholders with a means for evaluating reach and enforcement of tobacco regulatory policies. Given the strong emphasis on youth access violations, future work may inform regulations designed to reduce illicit sales to minors. For example, great promise from new “Tobacco 21” laws restricting the sale of tobacco products to persons younger than 21 years of age will require careful evaluation,25 and national FDA youth sales inspections may provide a framework for natural experiments as additional municipalities adopt similar restrictions. The FDA database also provides the tobacco control community with information on the tobacco industry’s rapid adaptation to these policies at the point of sale. Though the current study showed few violations related to the ban on flavored cigarettes or on reduced harm pack descriptors, understanding how federally-mandated changes to tobacco products and their marketing are countered by the tobacco industry through the retail environment will inform future FDA efforts and ensure the maximum possible effect of these laws on population health.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by internal seed funding from the American Legacy Foundation, and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Cancer Institute and Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (NIH - R01DA034734). We also wish to thank Charles Carusi (Westat) for his contribution to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statements

This work did not involve any human subjects.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Thomas R. Kirchner, Global Institute of Public Health, New York University, New York, NY.

Andrea C. Villanti, The Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at Legacy, Washington, DC.

Michael Tacelosky, Survos, Washington, DC.

Andrew Anesetti-Rothermel, The Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at Legacy, Washington, DC.

Hong Gao, The Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at Legacy, Washington, DC.

Jennifer Pearson, The Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at Legacy, Washington, DC.

Ollie Ganz, American Legacy Foundation, Department of Research and Evaluation, Washington, DC.

Jennifer Cantrell, American Legacy Foundation, Department of Research and Evaluation, Washington, DC.

Donna M. Vallone, American Legacy Foundation, Department of Research and Evaluation, Washington, DC.

David B. Abrams, The Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at Legacy, Washington, DC.

References

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration. Overview of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information (Tobacco) 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Tobacco-Products/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm246129.htm. Accessed April 9, 2012.

- 2.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Vol HR 1256 C.F.R.2010.

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration. Timeline Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information (Tobacco) 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm237395.htm. Accessed April 9, 2012.

- 4.Natanblut SL, Mital M, Zeller MR. The FDA’s enforcement of age restrictions on the sale of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001;7(3):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration. Enforcement action plan for promotion and advertising restrictions. Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information (Tobacco) 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm271744.htm. Accessed April 9, 2012.

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. Compliance check inspections of tobacco product retailers. Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information(Tobacco) 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Guidance-ComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm232109.htm. Accessed April 9, 2012.

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration. Compliance check inspections of tobacco product retailers (through 10/31/2013). 2013. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/oce/inspections/oce_insp_searching.cfm. Accessed November 11, 2013.

- 8.Clark PI, Natanblut SL, Schmitt CL, et al. Factors associated with tobacco sales to minors: lessons learned from the FDA compliance checks. JAMA. 2000;284(6):729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frick RG, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Tobacco advertising and sales practices in licensed retail outlets after the Food and Drug Administration regulations. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose SW, Myers AE, D’Angelo H, Ribisl KM. Retailer adherence to Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, North Carolina, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. Compliance and Enforcement Report, 2014:1–28. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm396171.htm. Accessed January 3, 2015.

- 12.Glantz SA. Preventing tobacco use--the youth access trap. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(2):156–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemson DH, Moats HL, Watkins BX, et al. Laying down the law: reducing illegal tobacco sales to minors in central Harlem. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):936–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widome R, Brock B, Noble P, Forster JL. The relationship of point-of-sale tobacco advertising and neighborhood characteristics to underage sales of tobacco. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35(3):331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchner TR, Villanti AC, Cantrell J, et al. Tobacco retail outlet advertising practices and proximity to schools, parks and public housing affect Synar underage sales violations in Washington, DC. Tob Control. 2014:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration. States awarded FDA tobacco retail inspection contracts. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/ResourcesforYou/ucm228914.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco retail inspections. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/tobaccoProducts/Resourcesforyou/StateLocalTribalandTerritorialGovernments/ucm248083.htm. Accessed December 16, 2013.

- 18.Convenience Store Decisions Staff. FDA seeks retail inspectors. Convenience Store Decisions. 2013. Available at: http://www.csdecisions.com/2013/08/16/fda-seeks-retail-inspectors/. Accessed November 11, 2013.

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Food and Drug Administration. A strategic partnership. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/UCM284343.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2013.

- 20.Ilakkuvan V, Tacelosky M, Ivey KC, et al. Cameras for public health surveillance: a methods protocol for crowd-sourced annotation of point-of-sale photographs. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3(2):e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ArcGIS. United State street locator (mature support). 2013. Available at: http://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=6a17e2a980c042ec9a0e5848b1b52699. Accessed November 11, 2013.

- 22.Legacy. Point-of-Sale Tobacco Viewer. 2013. Available at: http://gis.americanlegacy.org/LegacyTobaccoViewer/.Accessed January 3, 2015.

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Tobacco Sales to Youth. FFY 2013 Annual Synar Reports, 2013:1–8. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/synar/annual-reports. Accessed January 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Angelo H, Fleischhacker S, Rose SW, Ribisl KM. Field validation of secondary data sources for enumerating retail tobacco outlets in a state without tobacco outlet licensing. Health Place. 2014;28:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winickoff J, Gottlieb M, Mello M Tobacco 21 – an idea whose time has come. N Engl J Med, 2014;370(4):295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]