To the Editor:

On July 25th 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mpox (monkeypox) a public health emergency of international concern.1 To date, the virus has primarily impacted gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM),2 which had many of their advocates concerned about GBMSM being blamed for mpox. An alarming homophobic discourse on social media emerged, including the use of Twitter hashtags #gaypox, #fagpox, and #pridepox. Although the scapegoating of GBMSM is not new,3 such homophobic discourse on the internet likely reinforces hateful stereotypes of GBMSM as diseased and deviant.

When HIV was identified in the early 1980s, researchers called the virus GRID—gay-related immunodeficiency4—an expression of stigma that hampered an effective public health response. Forty years after the first diagnosis, stigma remains one of the most intractable challenges to fighting HIV.5 This historical lens is crucial as we examine the mpox pandemic and the accompanying online homophobic discourse.

Social media platforms can play a powerful role in spreading online hate, or aggressive and offensive language against a particular group (e.g., homophobic narratives). Online hate persists more visibly, commonly, and explicitly on the internet due to conditions of online anonymity and beliefs in “digital freedom of speech” that reduce social accountability.6 Social media platforms can also vicariously expose individuals to hateful content (e.g., racist or homophobic videos and photographs) and information that illuminates the systemic oppression (e.g., racism and homophobia) in Western societies.6 The online polarization of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor is a major example of how social media facilitates traumatizing discourse around anti-Black racism.

Similarly, homophobic cyberaggression and content, which spread hateful narratives against GBMSM, are likely to have a costly impact—cyberhate has been linked with offline violence5 and negative mental health outcomes.6 We analyzed Twitter data to examine the potential increase in homophobic and mpox-related online hate that coincided with the global mpox outbreak during the summer of 2022. Twitter was chosen as it is a leading microblogging social media platform that allows observation of polarizing and trending themes in online narratives.

The current analysis was exempt from institutional review board review as it was conducted using a publicly available social media database. From a large public Twitter database,7 we sampled the text of 10% of tweets posted between January 2022 and October 2022 (N = 105,913,149). A search algorithm was used to detect all mpox-related and homophobic tweets (for complete details, see the Supplementary Data S1). Table 1 gives the number of tweets in each category by month. The number of mpox-related and homophobic tweets was normalized by the total number of tweets by month to visualize the trend in each category.

Table 1.

Total Tweets, mpox-Related Tweets, and Homophobic Tweets Per Month

| Month | Total No. of tweets | mpox-related tweets | Homophobic tweets |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 12,058,680 | 39 | 320 |

| February | 11,211,970 | 21 | 256 |

| March | 12,387,960 | 22 | 253 |

| April | 12,172,370 | 15 | 321 |

| May | 12,343,739 | 1,499 | 300 |

| June | 11,576,464 | 593 | 291 |

| July | 11,323,890 | 2,195 | 351 |

| August | 10,836,850 | 1,548 | 292 |

| September | 7,522,201 | 169 | 173 |

| October | 4,479,025 | 52 | 109 |

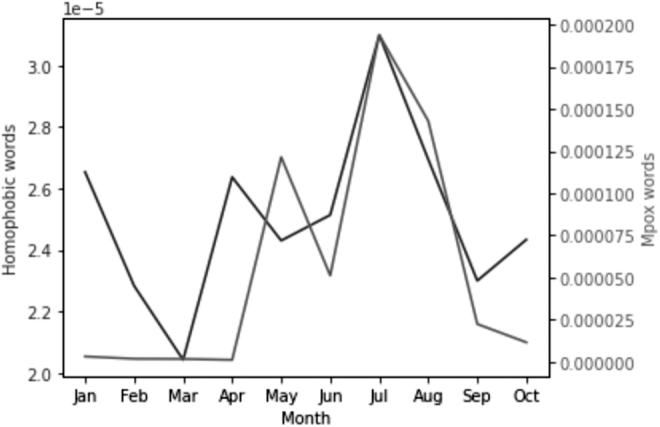

Figure 1 visualizes an uptick in homophobic terms on Twitter coinciding with the global emergence of mpox. The trend in the number of tweets with homophobic terms mirrors the trend in the number of tweets with mpox-related terms. Both trends have peaks in July.

FIG. 1.

Trend of monthly mpox-related and homophobic posts on Twitter, January 2022 through October 2022. Line starting at bottom from left depicts the number of tweets using at least one mpox-related search term (right y-axis) and the line starting at top from left depicts the number of tweets using at least one homophobic search term (left y-axis), normalized by the total number of tweets for each month.

Although the results cannot be generalized across social media platforms, Twitter data showed a polarizing trend in homophobic and mpox-related online hate against GBMSM. It is important to approach online homophobia as a structural issue. Similar to the multilevel framework of online anti-Black racism,8 the far-reaching network of online homophobia including mpox stigma can be conceptualized as a structural and digital inequity that may be a driver of health disparities among GBMSM.

This online discourse can influence government and technology policies and practices that reflect anti-GBMSM biases such as homophobic miseducation, mis/disinformation, online heterosexism, and homophobic privacy violation. In turn, these forces may exacerbate biases in health care provision and resource allocation for GBMSM health.

Much like the stigmatization of GBMSM during the HIV epidemic that prevented them from receiving effective health care,5 mpox stigma, amplified by social media, may bring adverse outcomes. This stigma is likely to persist even after the mpox outbreak is contained. At the individual level, this process might worsen the psychosocial and physiological stressors already faced by GBMSM and could increase their distrust and underutilization of health care services. In the next sections we describe considerations for clinical practice, policy, and research to address GBMSM health with respect to mpox.

Clinicians are rapidly learning to diagnose and treat mpox, which to date has primarily affected GBMSM.2 Clinicians working with GBMSM to diagnose and treat mpox and other infections that may be acquired through sexual contact will need to talk openly and nonjudgmentally about sexuality and sexual behavior. Although challenging, this is essential for providing patient-centered care and for contact tracing efforts that will prevent mpox spread among GBMSM and the public. To facilitate honest disclosures on behalf of GBMSM, clinicians should present LGBTQ+ focused or friendly content (e.g., public health posters featuring GBMSM, rainbow pin on a lab coat, etc.) in their offices and clinics.

Rather than focusing on sexual orientation when attending to GBMSM, clinicians should emphasize the behaviors that increase the risk of contracting mpox (e.g., direct contact with mpox rash, sex, and skin-to-skin contact2) and discuss harm reduction approaches (e.g., getting vaccinated and asking sexual partners about mpox exposure). Individualized counseling and education about safer sex practices might also be offered if indicated. Clinicians also must be aware of the stigma forming around mpox and screen for co-occurring mental health issues and make appropriate referrals, when necessary.

The U.S. government's strategy to address mpox has included bolstering testing, contact tracing, and both pre- and postexposure prophylaxis for mpox. All these strategies and future efforts may be hurt by online homophobic discourse, which could further exacerbate the considerable challenges faced by clinicians and public health. The online homophobic discourse around mpox could skew policymakers' perception that the general public is not at risk for contracting mpox, might discourage GBMSM from getting tested as a way to avoid stigma, or could limit the development or distribution of mpox vaccines.

Within the context of the current anti-LGBTQ+ political landscape across the country,9 there are examples of policymakers using social media to minimize mpox and stigmatize GBMSM.10 Public health messaging about mpox should focus on GBMSM as the population most at risk while confronting the notion that mpox is a “gay disease.” As progress is made in containing the mpox crisis, messaging should particularly focus on countering the mpox stigma and the larger homophobic societal norms. For example, messaging could emphasize how mpox is spread beyond sex while showing images of many kinds of people who had, or could contract, mpox.

As with the rampant spread of anti-Asian hate during COVID-19, researchers should explore the nature of mpox-based stigma and in general online homophobia. Studies could assess how GBMSM respond to mpox and online hate across various environments (e.g., through apps and offline among peers). The development of psychometrically sound measures that assess online homophobia is also imperative to assess the impact on the mental and behavioral health of GBMSM. Qualitative studies can provide valuable insight into the mental health and advocacy needs of GBMSM.

In addition, given our U.S. focus, more research examining mpox-based stigma and online homophobia in international contexts is required. Finally, research shows that online hate targets minority groups,6 and intersectional evidence (e.g., compounding stigma associated with homophobia, racism, and diseases that can be transmitted through intimate contact including mpox) should be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, our Twitter data analysis suggests that the mpox crisis may have further catalyzed online hate and stereotyping against GBMSM. The polarization of such hate can negatively affect the well-being of GBMSM at individual and systemic levels, specifically in the areas of health, mental health, and health care service. We provided recommendations for research, clinical practice, public health messaging, and policies for collective advocacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.J.C. contributed to this article under the support of a RISE fellowship with the National Institutes of Health (R25GM061222).

Authors' Contributions

All authors are aware and have confirmed their contribution and authorship on this article. B.T.H.K. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. C.H. was involved in data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. M.B. carried out data curation, formal analysis, and visualization. C.J.C. was in charge of formal analysis, and writing—review and editing. I.W.H. took charge of conceptualization, supervision, methodology, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Nuzzo JB, Borio LL, Gostin LO. The WHO declaration of monkeypox as a global public health emergency. JAMA 2022;328(7):615–617; doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. . Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—April–June 2022. New Engl J Med 2022;387(8):679–691; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med 2015;38(1):1–8; doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altman LK. New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials. The New York Times: New York, NY; 1982. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/1982/05/11/science/new-homosexual-disorder-worries-health-officials.html [Last accessed: July 30, 2022].

- 5. Brent RJ. The economic value of reducing the stigma of HIV/AIDS. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013;13(5):561–563; doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.832207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keum BT, Miller MJ. Racism in digital era: Development and initial validation of the Perceived Online Racism Scale (PORS v1. 0). J Couns Psychol 2017;64(3):310–324; doi: 10.1037/cou0000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steinert-Threlkeld ZC. Twitter as Data. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Volpe VV, Hoggard LS, Willis HA, et al. . Anti-Black structural racism goes online: A conceptual model for racial health disparities research. Ethn Dis 2021;31(Suppl 1):311–318; doi: 10.18865/ed.31.S1.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, et al. . The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. Am J Public Health 2010;100(3):452–459; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bollinger A. Marjorie Taylor Greene says Americans should “mock” monkeypox since it affects gay men. LGBTQ Nation: San Francisco, CA; 2022. Available from: https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2022/07/marjorie-taylor-greene-says-americans-mock-monkeypox-since-affects-gay-men [Last accessed: July 30, 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.