Abstract

Background

Cognitive functioning is increasingly assessed as a secondary outcome in neuro-oncological trials. However, which cognitive domains or tests to assess, remains debatable. In this meta-analysis, we aimed to elucidate the longer-term test-specific cognitive outcomes in adult glioma patients.

Methods

A systematic search yielded 7098 articles for screening. To investigate cognitive changes in glioma patients and differences between patients and controls 1-year follow-up, random-effects meta-analyses were conducted per cognitive test, separately for studies with a longitudinal and cross-sectional design. A meta-regression analysis with a moderator for interval testing (additional cognitive testing between baseline and 1-year posttreatment) was performed to investigate the impact of practice in longitudinal designs.

Results

Eighty-three studies were reviewed, of which 37 were analyzed in the meta-analysis, involving 4078 patients. In longitudinal designs, semantic fluency was the most sensitive test to detect cognitive decline over time. Cognitive performance on mini-mental state exam (MMSE), digit span forward, phonemic and semantic fluency declined over time in patients who had no interval testing. In cross-sectional studies, patients performed worse than controls on the MMSE, digit span backward, semantic fluency, Stroop speed interference task, trail-making test B, and finger tapping.

Conclusions

Cognitive performance of glioma patients 1 year after treatment is significantly lower compared to the norm, with specific tests potentially being more sensitive. Cognitive decline over time occurs as well, but can easily be overlooked in longitudinal designs due to practice effects (as a result of interval testing). It is warranted to sufficiently correct for practice effects in future longitudinal trials.

Keywords: Adult, Cognition, Cognitive evaluation, Glioma, Meta-analysis

Key Points.

- Normalized cognitive scores of glioma patients are below average on multiple tasks.

- Specific tests are more sensitive to detect cognitive decline throughout treatment.

- To detect treatment-related decline, attention is required for practice effects.

Importance of the Study.

Long-term cognitive sequelae can severely impact the quality of life in glioma patients after their multimodal treatment. However, evidence on which cognitive tests to implement in clinical routine to detect these cognitive problems is still lacking. In this meta-analysis (after screening 7098 articles), we investigated the longer-term test-specific cognitive outcomes in adult glioma patients, involving 4078 patients. Moreover, we performed meta-regression analyses to investigate the role of practice effects. Based on these outcomes, we provide recommendations on the use of specific test materials, raw versus standardized scores, and future trial designs to standardize follow-up protocols in this population. To the best of our knowledge, such test and score specificity was never reported before, nor was information provided on repeated test assessments. However, uniformization and correction for practice effects for multiple test materials will be crucial to moving forward in our understanding of cognitive outcomes in glioma patients.

Gliomas are the most common type (ie, 70%) of malignant primary brain tumors.1 Due to improvements in the existing multimodal treatments, patients’ survival rates have increased in the last decades. Consequently, the aspects of the patients’ functioning and well-being are becoming more important, including health-related quality of life and cognitive functioning. The prevalence of cognitive impairment in adult World Health Organization (WHO) glioma (grade 1–3) patients has been estimated at 27%–83%.2 The large variability in these prevalence numbers is partly due to heterogeneous study designs and populations, various cognitive tests that were used, and inconsistent definitions of impairment across trials. Furthermore, by investigating general cognitive impairment one could neglect the granularity of cognitive outcomes (and domain or test specificity) and individual patient profiles. More specifically, cognitive sequelae in glioma patients can consist of specific problems in memory, attention, executive functioning, processing speed, perception, and language.3 Although cognitive functioning is increasingly assessed as secondary outcome in neuro-oncological clinical trials, and guidelines for optimal management of cognitive deficits in brain tumor patients have been proposed earlier (eg, ICCTF, EANO, NCCN, and IPCG), evidence for test specificity in glioma patients is still lacking.4

Meta-analyses can be used to address this question. To date, few meta-analyses exist which assess the cognitive outcome data of the existing literature in glioma patients. Ng et al. investigated cognitive outcomes up to 6 months post-surgery with data from 11 studies.5 In this meta-analysis, glioma surgery appeared to be beneficial for the domains of complex attention, language, learning, and memory, while it could negatively affect executive functioning, both immediately after surgery and at 6 months follow-up. Lawrie et al. focused on cognitive outcomes after radiotherapy in a subset of glioma patients (based on 9 studies) who were tested at least 2 years after radiotherapy.6 They concluded that radiotherapy may increase the risk of long-term cognitive side effects, but the data remained insufficient to estimate the magnitude of the risk. Although these meta-analyses provided valuable initial insights, data between 1 and 2 years after therapy were neglected. However, other studies have clearly shown that cognitive impairment in fluency, working memory, and verbal memory can already be observed at 1-year follow-up after radiotherapy.7 Furthermore, test scores were grouped into domains, which does not provide information on test specificity and sensitivity to detect more subtle cognitive changes. Additionally, the existing meta-analyses did not analyze the impact of potential practice effects. These occur when patients get more familiar with a test due to memory of the content, or application of more efficient strategies after repeated testing procedures. Methods for limiting these effects include alternate forms/parallel versions of tests, reliable change index or standardized regression-based change scores and having longer interval periods.8 If studies included in meta-analyses do not analyze the role of practice effects, the meta-analysis may overestimate certain cognitive outcomes. Finally, in recent years, the number of studies reporting cognitive outcomes in glioma patients have increased dramatically, resulting in a larger number of cognitive data that were not included in previous meta-analyses.

Meta-analyses on cognitive outcomes in non-CNS cancer types, mostly breast cancer, after chemotherapy showed that these cancer patients performed worse than controls mostly on cognitive domains of memory, attention, and executive function. In longitudinal trials, patients improved over time, but potential practice effects were not taken into account.9–11

In this study, we aim to further improve our insight into longer-term cognitive outcomes in the adult glioma population. Herein, we will solely focus on objective cognitive functioning, as measured with neuropsychological tests in the research context. Given the previously mentioned existing gaps, we aim to report on test-specific cognitive outcomes after 1-year follow-up. To study both cognitive changes within patients over time and compare cognitive outcomes of patients versus controls/norms at 1-year follow-up, we will perform separate meta-analyses for both designs (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional, respectively). Furthermore, we report on how previous clinical studies dealt with practice effects in glioma patients specifically and aim to investigate the potential role of these practice effects in the research setting, based on the longitudinal studies, which were largely neglected so far in previous reviews. Based on these findings, we intend to aid in the development of clearer recommendations for improving future clinical trials.

Methods

Literature Search

A comprehensive literature search (see Supplementary Material 1 for the protocol) was performed on July 19, 2021, using the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Library, and PsycArticles databases. The search string consisted of 3 main components, including a range of glioma-, cognition-, and treatment-related keywords (see Supplementary Material 1). Articles covering each of these three topics and being published between January 01, 1990 and July 19, 2021 were selected to cover the literature of the past 2 decades.

Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of the articles were independently screened in Rayyan12 by 2 independent reviewers (A.V. and C.S.). Disagreement was resolved by consensus. Studies were included if they reported an investigation of (1) adults, defined as subjects of 18 years and older, (2) who had a diagnosis of a WHO grade 1–4 glioma, (3) with a sample size of more than 5 subjects, (4) in which subjects received cancer treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy), and (5) cognitive outcome scores were reported with validated cognitive tests (objectively assessed by an independent assessor) at least 1 year after the treatment for cross-sectional studies and at least 1-year post-baseline in longitudinal studies. Only original studies were eligible. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: Studies in a non-English language, intervention, or rehabilitation studies to improve cognitive outcomes. Detailed information from all included studies was summarized in tables containing study characteristics (author, year, and design), characteristics of the study population (sample size, age, gender, tumor histology, and grade), cognitive tests that were used, timing of assessments, whether or not potential practice effects were accounted for and in which way, and main findings. Tables were created separately per design (ie, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies). Quality assessment was performed by the risk of bias assessment in individual studies (see Supplementary Material 2 and 3).

Design and Extraction of Data for Analyses

Two separate datasets were constructed. First, to investigate cognitive changes after 1 year in a sufficient and maximally homogenous sample, test scores at baseline (pretreatment) and after 1 year (maximum of 24 months) follow-up were included in a dataset for longitudinal studies. In this dataset, the moderator interval testing (yes vs. no) was also included, to be able to investigate potential practice effects. This interval testing was defined as “additional cognitive testing between baseline and 1-year post-treatment.”

For randomized controlled trials randomizing between 2 nonexperimental treatment arms (eg, procarbazine-lomustine-vincristine (PCV) and temozolomide), both treatment arms were included but not compared. When the patients were randomized between an experimental and nonexperimental treatment, only the treatment arm that received treatment considered as standard clinical care was included.

Second, to investigate cognitive status compared to healthy controls, the patient and control/normative data (healthy controls) assessed at 1 year or more posttreatment (no maximum) were included in a dataset for cross-sectional studies. By selecting these timepoints, we targeted the maximal amount of available data and the potential dropout effects were minimized.

Scores from specific cognitive tests were extracted in a dataset if at least 2 studies reported scores of a similar test within the same design (ie, longitudinal/cross-sectional) and reporting method (ie, raw/z-scores). These collected values were either means and standard deviations of raw test scores (eg, raw accuracy rates, response times), or means and standard deviations of normalized test scores, represented by z-scores, which are standardized scores based on test-specific norm tables or healthy control groups.

In case of missing data, the data were requested from the corresponding author(s) by email. If the same data were presented in multiple reports, they were included only once in the analyses.

Statistical Analyses: Meta-analyses

Based on both raw- and z-scores in longitudinal (change over time) and cross-sectional (patients vs. controls assessed at one-time point) designs, separate random-effects meta-analyses for each cognitive test were performed. The random-effects model was selected to take between-study heterogeneity in true effect size into account, and to be able to generalize the results to the population of studies. For these analyses, Hedges’ g standardized mean differences and corresponding sampling variances (for each cognitive test) were calculated based on the equations of Borenstein13 and Hedges14 (see Supplementary Material 3). Effect sizes were interpreted based on the rules-of-thumb of Cohen15 and findings were reported if effects were of moderate or high size. Next, we will describe the 2 different approaches for the specific study designs (longitudinal and cross-sectional).

First, for longitudinal analyses, a Pearson’s correlation of r = 0.5 was assumed to compute Hedges’ g and its sampling variance as exact correlations were underreported in studies. If sample sizes differed between baseline versus follow-up, we used the harmonic mean of the sample size at both measurements. In order to check for potential practice effects, a meta-regression analysis with a moderator for interval testing (yes vs. no) was performed for the longitudinal datasets (see Supplementary Material 3).

Second, for studies with a cross-sectional design without a control group but with reported z-scores (based on published norms), these mean normalized test scores were compared to a standard value of 0.

Between-study heterogeneity was quantified by the between-study variance (estimated with the restricted maximum likelihood estimator) and the I2-statistic (ie, percentage of total variance that can be attributed to between-study variance16). The Q-test17 was used to test the null hypothesis of no between-study heterogeneity. The classification of Higgins et al. was used to evaluate the degree of heterogeneity.16

Additionally, equal effect meta-analyses were fitted as sensitivity analyses. All meta-analyses were also repeated including only the low-risk-of-bias studies as a validity check (see Supplementary Material 3).

Practice Effects

To analyze the potential practice effects, a meta-regression analysis with a moderator for interval testing (yes vs. no) was performed for the longitudinal datasets. In this analysis, the effect sizes of time effects in patients who had no assessment during the interval were denoted by b0, while differences in time effects in patients who had interval testing versus patients who did not, were estimated as b1. Hence, these parameters (b0 and b1) are summed to interpret the effect of change in the group of patients with interval testing.

Tumor Grade Sub-analysis

To explore potential differences in cognitive outcomes between low-grade glioma (LGG) and high-grade glioma (HGG) patients, a subgroup analysis was performed on the raw test scores, with the variable “majority HGG patients” (ie, >50% patients with HGG) as a moderator of the regression analysis. In this analysis, effect sizes of studies including mostly LGG patients were denoted by b0 and differences in effects with HGG studies (compared to b0) were denoted by b1.

All hypotheses were tested using α = 0.05. We refer to Supplementary Material 3 for the R script.

Results

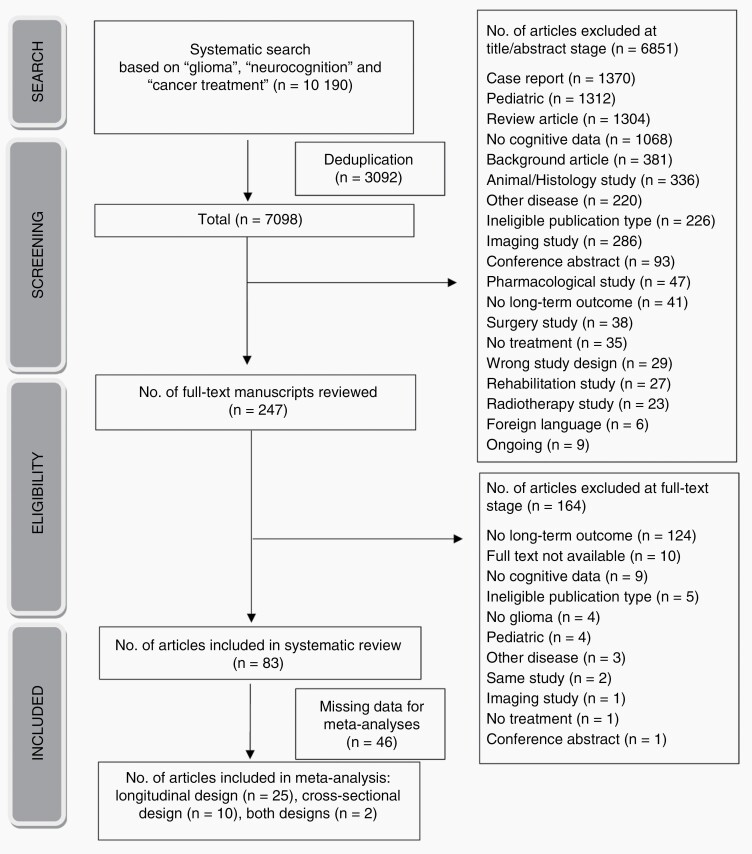

For the results of study selection and risk of bias, we refer to Supplementary Material 4. In Figure 1, a flowchart of the selection process of the included studies, is shown.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection process of the included articles.

Of all 83 studies, 37 studies were included in the meta-analysis, including 25 studies with longitudinal design (Table 1; Figure 2B),

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies with longitudinal design

| Authors | N | Age range and gender | Glioma/tumor subtype | Treatment | Neuropsychological tests and correction for practice (P) | Time points of testing (number of interval tests < 12m) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archibald et al.18 | 25 | 18–63years 12 male, 13 female |

HGG | Surgery, RT and adjuvant CT | WAIS, WMS, ROCF, SRT TMT B, Monroe-Sherman Reading Comprehension, Design, Fluency – P: Not available | BL: 1–63 months after diagnosis FU: 6 monthly or yearly interval, with the last test at 68–102 months after diagnosis (1) |

At baseline, the greatest impairment was observed in verbal memory and sustained attention. Verbal learning and flexibility in thinking had the greatest chance to decline over time. |

| Armstrong et al.19 | 26 | 18–69years 15 male, 11 female |

Glioma WHO grades 1–2, pineal and pituitary tumour, non-invasive meningioma | WBRT after surgical biopsy, resection, or no surgical intervention. | Praxis, Finger Tapping Test, Bells Test, Auditory Selective Attention Test, Visual Continuous Performance Test, Sentence Repetition Test, COWAT, Animal Naming Test, PASAT, DSST, Digit Span, Word Span Test, RAVLT, Road Map Test, Visual Pursuits Test, ROCF, Visual Memory Span Test, BVRT, Biber Figure Learning Test, WCST- P: alternate forms | BL: 6 weeks after surgery, before RT FU: every year (until year 6) (0) |

5 years after WBRT, patients showed cognitive decline in visual memory. Motor function, attention and executive functioning, language, verbal memory, information processing speed and visuospatial abilities did not deteriorate or even improved. |

| Bian et al.20 | 18 | 18–65years 10 male, 8 female |

HGG | Surgery, RT and CT | MMSE, MoCA- P: not available | BL: Before RT FU: Post-RT, at 3,6,9, and 12 months post-RT (3) |

No significant changes in cognitive functioning before treatment or at follow-up was observed. |

| Brown et al.21 | 187 | >18years 105 male, 82 female |

Supratentorial LGG | Tumor resection and RT: 50.4Gy or 64.8Gy | MMSE- P: not available | BL: study entry FU: at 1,2 and 5 years (0) |

The minority of patients had a decrease in MMSE score. Most patients showed an increase. Recall and serial sevens showed more difficulties than other tests. |

| Brown et al.22 | 1244 | 18–84years 692 male, 552 female |

HGG, gliosarcomas | RT and nitrosourea-based CT | MMSE – P: not available | BL: after surgery FU: at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months (1) |

The tumor itself was the main cause of cognitive deterioration. |

| Butterbrod et al.23 | 263 | Mean age: 53.2 years 164 male 99 female |

Glioma WHO grade 2–4 | Surgery and/or RT and/or CT | CNS Vital Signs, Digit Span, Letter Fluency- P: Standardized regression-based change scores | BL: 1 day before surgery FU: 3 and 12 months after surgery (1) |

No significant effect of ε4 carrier status or interaction between time (T0–T12) and carrier status on any of the tests in the whole sample nor in the sample receiving adjuvant treatment. |

| Carbo et al.*,24 | 28 | Mean age: 37 years, 22 male, 6 female |

Glioma, cavernoma, cavernous hemangioma, MTS | Surgery | Categoric Fluency, RAVLT, SCWT, LDST- P: not available | BL: 3 months before surgery FU:12 months post-surgery (0) |

Patients’ cognitive performance did not change significantly between baseline and post-surgery (group level) |

| Corn et al.25 | 209 | 20–82years 139 male, 70 female |

Supratentorial GBM | Surgery, CT and RT | MMSE- P:RCI | BL: Before RT FU: at 4, 8 and 12 months after RT (2) |

Cognitive function seemed to deteriorate over time, although cognitive impairment was more significant when the scores were adjusted for age and education. |

| Gondi et al.*,26 | 18 | 19–82years 10 male, 8 female |

LGG, pituitary adenomas, vestibular schwannomas, meningiomas | Fractioned stereotactic RT | NART, WAIS, BNT, Token Test, Judgment of Line Orientation, Facial Recognition Test, Hooper Visual Organization Test, WMS-III, TMT, SCWT- P: standardized regression-based change scores | BL: Before RT FU: 12 and 18 months after RT(0) |

A correlation was observed between fraction dose to the bilateral hippocampi and memory impairment in the long-term. |

| Gui et al.27 | 30 | 35–87 years 16 male, 14 female |

GBM | Surgery, RT (NPC niche sparing) and TMZ | TMT A&B, COWAT, Coding, HVLT-R- P: Not available | BL: Before RT/CT FU: at 6 and 12 months after RT (1) |

Lower doses to the hippocampi and the SVZ may reduce deterioration of verbal memory (HVLT-R) |

| Hartung et al.28 | 22 | 21–67 years 11 male, 11 female |

LGG | Surgery and/or RT and/or CT | TMT, SCWT- P:RCI | BL: Before surgery FU: 3–18 months after surgery (0) |

Disconnection of the lateral part of the dorsal stream might be correlated specifically with impaired set-shifting (changes in TMT) and not with inhibition (no changes in Stroop Task) |

| Hendriks et al.29 | 59 | 18–67years 34 male, 25 female |

Gliomas WHO grade 1–3 | Surgery and/or RT and/or CT | Digit Span, SCWT, TMT, DSST, ROCF, RAVLT, Location Learning Test, Memory Comparison Test, Categoric and Phonemic Word Fluency Test, BADS- P:not available | BL: 1 week before surgery FU: 1 year post-surgery (0) |

Six patients showed cognitive improvement in working memory. Ten patients showed cognitive decline in attention, 9 in information processing speed, 7 in visual construction, 6 in both visual and verbal memory, and 4 in both working memory and executive functioning. The right hemisphere was the most vulnerable region for cognitive decline after surgery. |

| Jaspers et al.30 | 29 | 30–50years 18 male, 11 female |

LGG | Surgery and RT | RAVLT- P: Standardized regression-based change scores | BL: Before treatment FU: 18 months after treatment (0) |

Older patients and patients with a tumor in the left hemisphere of the brain had more risk for developing cognitive decline 18 months after treatment. |

| Laack et al.31 | 20 | >18years 14 male, 6 female |

LGG | Surgery and localized RT (50.4Gy or 64.8Gy) | MMSE, WAIS-R, RAVLT, BVRT, TMT, SCWT, COWAT- P: not available | BL: Before RT FU: Median of 18 months after RT (0) |

At 1.5 years after treatment, no significant cognitive decline was observed in the high-, neither in the low-dose group. |

| Moretti et al.32 | 34 | Mean age: 46 years | Glioma, cerebral lymphoma, and craniopharyngioma | Surgery or biopsy and RT (30–45Gy or 45–65Gy) | MMSE, Digit Span, Categoric and Phonemic Word Fluency, Mental and Written Calculation and Analogies.-P: Not available | BL: Mean scores before surgery and before RT FU: 12 months after RT (0) |

Cognitive decline is related to the total radiation dose, the volume of the irradiated brain and the individual fraction size. < 35Gy: no cognitive impairment > 35Gy: cognitive decline |

| Moretti et al.7 | 114 | Mean age: 45.2 years | GBM, WHO grade 2 gliomas, craniopharyngiomas, cerebral lymphomas, AC WHO grade 2–3, anaplastic patterns | Surgery or biopsy and/or RT and/or CT | MMSE, Digit Span, Semantic and Phonemic Fluency, Mental Calculation, Analogies- P:not available | BL: before surgery FU: after RT and 3,6 and 12 months after RT (3) |

A cognitive and behaviour decline was observed in patients exposed to significant RT doses, 30–65 Gy. This decline was similar to what was typically observed in sVAD (dysexecutive functions, apathy, and gait alterations), but with a more rapid onset and with an overwhelming effect |

| Norrelgen et al.33 | 27 | 17–56years 17 male, 10 female |

Gliomas WHO grade 2–3, cavernoma, GBM | Awake surgery | TROG-2, BNT, MBT, Token test, BeSS, Word Fluency (FAS, Animals, and Verbs), AQT, DLS, LS- P: Not available | BL: 3 weeks before surgery (mean) FU: 3 and 12 months post-surgery (1) |

Overall high-level language ability was not significantly affected postoperatively at 3 and 12 months. However, semantic word fluency deteriorated postoperatively at 3 and 12 months follow-up, indicating a decline in processing speed of verbal material postoperatively. |

| Prabhu et al.34 | 287 | 22–79years 158 male, 129 female |

Low-risk LGG, High-risk LGG |

Surgery and RT with or without CT (PCV) | MMSE- P: Not available | BL: before RT FU: at year 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (0) |

The majority of patients did not show cognitive decline. |

| Reijneveld et al.35 | 477 | >18 years | LGG | RT vs. TMZ | MMSE- P: Not available | BL: Before treatment FU: Every 3 months after treatment up until 36 months (3) |

Three years after treatment, no differences in cognitive functioning were established between the group who was treated with RT and the group who was treated with TMZ. |

| Sarubbo et al.36 | 12 | 19–63years 8 male, 4 female |

LGG | Awake surgery | MMSE, Laiacona-Capitani Naming Test, Token Test-P: Not available | BL: Before surgery FU: each follow-up for 3 years, no time points defined(unknown) |

Cognitive functioning did not worsen in this cohort, and even improved in two patients. Language did not decline in any of the patients. |

| Sherman et al.37 | 20 | 22–56years 13 male, 7 female |

LGG | Surgery (or biopsy) and proton RT | WAIS-III, BNT, ANT, CPT-II, TMT A&B, COWAT, HVLT, BVMT- P:RCI | BL: before RT FU: at 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months post-RT (0) |

Cognitive stability or improvement in visuo-spatial abilities and executive functioning was observed. Improvement in verbal memory was greater in patients with left-sided tumors. |

| Torres et al.38 | 22 | >18years 11 male, 11 female |

Glioma, meningioma, adenoma, ependymoma | Surgery and RT | Shipley Institute of Living Scale, SRT, 10/36 Spatial Recall Test, LDST, Digit Span, TMT-P: not available | BL: before RT FU: at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-RT (2) |

Cognitive functioning did not decline in the first 2 years after RT, but a mild improvement in recall and verbal memory was observed. |

| Vigliani et al.39 | 33 | 24–49years 12 male, 5 female |

LGG or anaplastic AC | Surgery (or biopsy) with or without RT and/or CT | SCWT, WAIS, Reaction Time, Verbal and Visual Span, RPM, WMS, Word and Design Series, ROCF—P: Not available | BL: After surgery, before RT FU: at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months after RT (1) |

Attention and memory were impaired within 6 months after RT. However, no cognitive decline was observed 1-2 years after RT. The risk of cognitive decline was higher in older patients than in young adults. |

| Wang et al.40 | 289 | >18years | Anaplastic ODG | RT with or without CT (PCV) | MMSE-P: Not available | BL: Before RT/CT FU: at 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, 44,50,56, 62, 68, and 74 months (0) |

No difference in scores on the MMSE between 2 groups (RT+PCV or RT alone) High MMSE scores predicted a lower risk of death. Tumor progression caused cognitive decline. |

| Wang et al.41 | 229 | >18years 135 male, 94 female |

HGG | Surgery and RT and CT | MoCa- P: Not available | BL: After surgery, pre-RT FU: at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months after RT (3) |

67% of patients showed cognitive impairment, statistically significant at 9 months follow-up. Unmethylated MGMT promoter methylation, and residual tumor volume >5.58cm3 were independent risk factors for cognitive impairment |

| Weller et al.42 | 141 | 18–70 years | GBM | Surgery, RT and CT (TMZ or TMZ-lomustine) | TMT A and B, WAIS Digit Span (forward/backward), COWAT, Verbal Fluency, Regensburger Wortflüssigkeitstest, MMSE- P:RCI | BL: Before RT FU: Every 3 (MMSE) and 6 months (NOA07 battery) until 48 months (3 and 1) |

Differences in MMSE were in favour of the TMZ group but were not clinically relevant. No significant difference between the groups in any subtest of the cognitive test battery was observed. |

| Yavas et al.43 | 43 | 18–69years 27 male, 16 female |

LGG | Surgery (or biopsy) and RT | MMSE-P: Not available | BL: after surgery, before RT FU: at 3,6,12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after RT (2) |

Recall score (MMSE) declined in the first 3 years after treatment. Anti-epileptic drugs had a negative effect on cognitive functioning. |

Note. WHO = World Health Organization; LGG = low-grade glioma; HGG = high-grade glioma; AC= astrocytoma; ODG= oligodendroglioma; GBM = glioblastoma multiforme; MTS = mesial temporal sclerosis; RT = radiotherapy; WBRT = whole brain radiation; CT = chemotherapy; PCV = procarbazine, lomustine and vincristine; TMZ = temozolomide; ANT = Auditory naming test; AQT = A Quick Test of Cognitive Speed; BADS = Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome; BeSS = Behavioral and Emotional Screening System; BNT = Boston Naming Test; BVMT = Brief visuospatial memory test; BVRT = Benton Visual Retention Test; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; CPT-II = Conner’s continuous performance test (Second edition); DLS = Diagnostiskt material för analys av läs- och skrivförmåga; DSST = Digit Symbol Substitution test; HVLT(-R) = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (-Revised); LDST = Letter-digit substitution Test; LS = Klassdiagnoser för högstadiet och gymnasiet – Läs- & skrivdiagnostik (LS); MBT= Months Backwards Test; MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NART = National Adult Reading Test; PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; (R)AVLT = Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test; ROCF= Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; RPM = Raven Progressive Matrices; SCWT = Stroop Color and Word Test; SRT = Buschke Selective Reminding Test; TMT = Trail Making Test; TROG-2= Test for reception of Grammar-2; WAIS(-R) = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Revised); WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale; P = practice effects; RCI= Reliable Change Index; BL = baseline; FU = follow-up; NPC = neural progenitor cell; SVZ = subventrical zone; sVAD = subcortical vascular dementia..*: included in both longitudinal and cross-sectional meta-analyses.

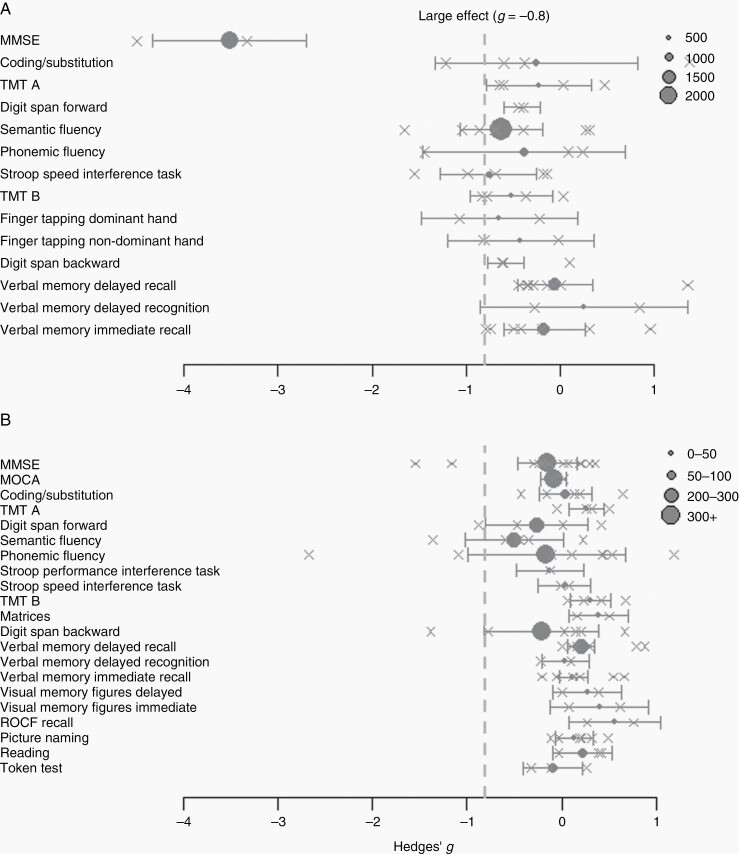

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the meta-analyses per cognitive test. Panel (A) demonstrates the effect sizes for cross-sectional studies. Panel (B) shows the effect sizes for longitudinal studies. The gray dotted line represents the cutoff for largest effect sizes (hedges g of >−0.8) towards impairment in glioma patients The number of included patients per analysis is represented by the size of the circles. The crosses indicate the effect sizes per included study.

10 studies with cross-sectional design (Table 2; Figure 2A), and 2 studies with both designs. Detailed characteristics of the remaining 44 studies with missing data for analyses are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies with cross-sectional design

| Authors | N | Age range & gender | Glioma/tumor subtype | Treatment | Neuropsychological tests | Time between tests | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bompaire et al. (2018)44 | 40 | Mean age: 59 years 15 male, 25 female |

WHO grade 2 and 3 glioma, GBM | RT with or without CT | MMSE, Digit Span, Fluencies, Dementia Rating Scale, Free Recall Test | FU: >6 months after RT—compared to normative data | Verbal episodic memory and concentration was impaired in (nearly) all patients. In addition, 6 patients had storage impairment. Thirty-four patients had an executive dysfunction, pathological phonemic and semantic fluencies and impaired short-time and working memory. |

| Boone et al. (2016)2 | 27 | 36–51years 17 male, 10 female |

AC, ODG, OAC and ependymoma | Surgery, RT, CT | MMSE, RPM, Token Test, BNT, Albert Cancellation Test, ROCF, Digit and Spatial Span, SRT, Doors and People Test, DSST, SCWT, TMT, Categoric and Phonemic Word Fluency Test, Modified Card Sorting Test, BADS | FU: median 3 years after treatment—compared to normative data | In half of the patients psychomotor speed, executive functioning, oral expression, long-term and short-term verbal memory and visual construction were impaired. |

| Carbo et al. (2017)*,24 | 28 | Mean age: 37 years, 22 male, 6 female |

Glioma, cavernoma, cavernous hemangioma, MTS | Surgery | Categoric Fluency, RAVLT, SCWT, LDST | FU:12 months post-surgery—compared to normative data | Patients’ cognitive performance did not change significantly between baseline and post-surgery (group level) |

| Cayuela et al. (2019)45 | 48 | >18years 30 male, 18 female |

WHO grade 2–3 ODG | RT and CT | HVLT, ROCF, COWAT, TMT, MMSE | FU: compared 2–5 years, 6–10 years and >10 years after treatment | Five years after treatment, patients showed severe cognitive impairment. Ten years after treatment, significant more impairment was observed in visual memory and in executive functioning. |

| Correa et al.46 | 40 | 23–59years 25 male 15 female |

LGG | RT (12) and CT (5) or no treatment | Digit Span, BTA, TMT A&B, SCWT, Categoric and Phonemic Word Fluency, Auditory Consonant Trigrams, HVLT, BVMT, Grooved Pegboard Test, BNT, Line Orientation Test | FU: median 38 months after diagnosis—compared treatment vs. no treatment | Treated patients scored significantly lower on psychomotor functioning and visual memory than non-treated patients and scored not-significantly lower on attention, executive functioning, verbal memory, and language. |

| Gondi et al.*,26 | 18 | 19–82years 10 male, 8 female |

LGG, pituitary adenomas, vestibular schwannomas, meningiomas | Fractioned stereotactic RT | NART, WAIS, BNT, Token Test, Judgment of Line Orientation, Facial Recognition Test, Hooper Visual Organization Test, WMS-III, TMT, SCWT | FU: 12 and 18 months after RT—compared to control group | A correlation was observed between fraction dose to the bilateral hippocampi and memory impairment in the long-term. |

| Haldbo-Classen et al.47 | 78 | 20–79 years 47 male, 31 female |

Glioma WHO grade 2–3, meningioma, pituitary adenoma, medulloblastoma | Surgery or biopsy, RT and/or CT | TMT A&B, SCWT, WAIS-IV Coding and Digit Span, HVLT-R, COWAT, PASAT (3 Seconds) | FU: median time since RT 4.6 years—compared to normative data | High RT dose to the left hippocampus was associated with impaired verbal learning and memory. RT dose to the left hippocampus, temporal lobe, frontal lobe and total frontal lobe were associated with verbal fluency impairment and doses to the thalamus and the left frontal lobe with impaired executive functioning. |

| Klein et al.48 | 195 | 24–81years 120 male, 75 female |

LGG | Surgery or biopsy with or without RT | NART, Line Bisection Test, Facial Recognition Test, Judgment of Line Orientation Test, LDST, VVLT, WMT, SCWT, Categoric Word Fluency test, CST | FU: 1–22 years after treatment—compared to NHL/CLL and healthy control group | Both irradiated and non-irradiated LGG patients had a significant cognitive decline, suggesting the tumor itself could be responsible. In RT-conditions, fraction dose is responsible for the degree of cognitive decline. |

| Kocher et al.49 | 80 | 28–81 years 50 male, 30 female |

GBM, anaplastic AC/ODG | Surgery or biopsy and/or RT and/or CT | TMT A&B, Corsi Block-Tapping Test, DemTect (Supermarket, Number Transcoding, Digit Span, Word List Immediate and Delayed Recall) | FU: 1–114 months after initiation of treatment— compared to control group | Glioma patients performed significantly worse in the majority of cognitive domains. The observed cognitive impairment was mainly associated with reduced connectivity in the left inferior parietal lobule DMN node, resulting in a lowered performance in attention, executive function, language processing, verbal/visual (working) memory, and by the reduced connectivity of the left lateral temporal cortex DMN node, leading to reduced performance in language and verbal episodic memory |

| Kocher et al.50 | 121 | 25–80 years 73 male 48 female |

HGG | Surgery or biopsy and/or RT and/or CT | TMT, DemTect (Supermarket, Number Transcoding, Digit Span, Word List Immediate and Delayed Recall) | FU: 1–214 months after therapy—compared to control group | Scores of 9/10 cognitive tests were significantly lower in patients vs. controls, and affected 10%–47% of the patients with a clinically relevant deficit. |

| Solanki et al.51 | 9 | 14–60years 5 male, 4 female |

GBM | Surgery and adjuvant CT and RT | Finger Tapping, DSST, Color Trail Test, ANT, N-back Test, Spatial Span Test, Tower of London, AVLT, ROCF | FU: at least 3 years after diagnosis—compared to normative data | Impairment in psychomotor speed (dominant side), information processing speed, sustained attention, planning abilities and long‑term memory was observed. |

| Taphoorn et al.52 | 41 | 18–66years 24 male 17 female |

AC, ODG | Surgery (or biopsy) with or without RT | AVLT, WISC Mazes, Categoric Fluency Test, D2-test, Benton Facial Recognition Test, Judgement of Line Orientation Test, SCWT | FU: 12–147 months after diagnosis—compared to control group (NHL/CLL) | More cognitive disturbances in both LGG groups, however no significant differences between the groups with and without RT |

Note. WHO = World Health Organization; LGG = low-grade glioma; HGG = high-grade glioma; AC= astrocytoma; OAC= oligo-astrocytoma; ODG= oligodendroglioma; GBM = glioblastoma multiforme; MTS = mesial temporal sclerosis; RT = radiotherapy; CT = chemotherapy; ANT = Auditory naming test; BADS = Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome; BNT = Boston Naming Test; BTA = Brief Test of Attention; BVMT = Brief visuospatial memory test; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; CST = Concept Shifting Test; DSST = Digit Symbol Substitution test; HVLT(-R) = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (-Revised); LDST = Letter-digit substitution Test; MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; NART = National Adult Reading Test; PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; (R)AVLT = Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test; ROCF= Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; RPM = Raven Progressive Matrices; SCWT = Stroop Color and Word Test; SRT = Buschke Selective Reminding Test; TMT = Trail Making Test; VVLT = Visual verbal learning test; WAIS(-R) = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Revised); WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale; WMT = working memory task; BL = baseline; FU = follow-up; L= longitudinal design; CS: cross-sectional design; NHL: non-hodgkin lymfoma, CLL: chronic lymphatic leukaemia; DMN = default mode network; *: included in both longitudinal and cross-sectional meta-analyses.

Of all studies that reported information on methods for correction for practice effects, 30% (k = 8/27) applied correction for practice effects (11% standardized regression-based change scores (k = 3),23,26,30 4% alternate testing forms (k = 1),19 15% reliable change index (k = 4),25,28,37,42 respectively). Fifty-one percent reported whether they had corrected scores for covariates (age, education, and/or gender). Regarding molecular features, only 19% of the studies reported details on IDH mutation of the tumor (k = 3/10 cross-sectional and k = 4/27 longitudinal studies).

Cognitive scores of 21 out of 37 studies (56.8%) were readily available and extracted from the papers. Data from the remaining studies (43.2%) were requested. Tests included cognitive screening instruments (MMSE, MOCA), tests measuring processing speed (coding/substitution, TMT A), attention span (digit span forward), working memory (digit span backward), verbal learning and memory (word list learning eg, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test [HVLT]), visual learning and memory immediate and recall (object/figure learning, ROCF copy, and recall), executive functioning (semantic fluency, phonemic fluency, Stroop performance or speed interference task), logical reasoning (matrices), fine motor skills (finger tapping for dominant and non-dominant hand), and language (reading, token test). We focused on the results with moderate–high effect sizes in the paragraphs below

Longitudinal results: Change in cognitive performance over time

Results of the longitudinal random-effects model can be found in Table 3. Longitudinal data were available in 27 studies, covering 21 different cognitive tests, with posttreatment measurement of cognitive functioning at a median of 12 months posttreatment.

Table 3.

Results of (random-effects) meta-analysis of longitudinal studies reporting mean raw test scores

| Test | k | Est. (SE) | 95% CI | z-value (P) | (SE) | 95% CI | Q-value (P) | -statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 14 | 1658 | −0.112 (0.153) | (−0.413;0.188) | −0.732 (.464) | 0.301 (0.129) | (0.145;0.825) | 210.962 (<.001)* | 96.8 |

| MOCA | 2 | 214 | −0.085 (0.068) | (−0.218;0.048) | −1.257 (.209) | 0 (0.039) | (0;6.688) | 0.237 (.627) | 0 |

| Coding/substitution | 5 | 75 | 0.039 (0.141) | (−0.238;0.316) | 0.277 (.782) | 0.033 (0.070) | (0;1.240) | 6.730 (.151) | 33.3 |

| TMT A | 5 | 135 | 0.205 (0.097) | (0.014;0.396) | 2.101 (.036)* | 0.007 (0.034) | (0;0.389) | 4.152 (.386) | 13.6 |

| Digit span forward | 4 | 228 | −0.266 (0.275) | (−0.804;0.273) | −0.967 (.334) | 0.265 (0.246) | (0.062;4.409) | 39.252 (<.001)* | 91.9 |

| Semantic fluency | 5 | 280 | −0.502 (0.265) | (−1.021;0.017) | −1.895 (.058) | 0.322 (0.248) | (0.101;2.657) | 88.992 (<.001)* | 92.9 |

| Phonemic fluency | 8 | 368 | −0.164 (0.425) | (−0.998;0.669) | −0.386 (.699) | 1.389 (0.773) | (0.575;5.977) | 238.937 (<.001)* | 97.6 |

| Stroop performance interference task | 2 | 48 | −0.118 (0.140) | (−0.392;0.157) | −0.841 (.400) | 0 (0.057) | (0;0.022) | 0.002 (.969) | 0 |

| Stroop speed interference task | 2 | 46 | 0.027 (0.142) | (−0.252;0.306) | 0.190 (.850) | 0 (0.060) | (0;3.741) | 0.088 (.767) | 0 |

| TMT B | 5 | 125 | 0.238 (0.116) | (0.011;0.464) | 2.056 (.040)* | 0.019 (0.047) | (0;0.665) | 5.880 (.208) | 29.1 |

| Matrices | 2 | 42 | 0.388 (0.161) | (0.073;0.704) | 2.411 (.016)* | 0.003 (0.082) | (0;58.835) | 1.061 (.303) | 5.7 |

| Digit span backward | 6 | 258 | −0.212 (0.309) | (−0.817;0.394) | −0.685 (.494) | 0.523 (0.362) | (0.176;3.333) | 105.579 (<.001)* | 93.9 |

| Verbal memory delayed recall | 8 | 263 | 0.188 (0.065) | (0.061;0.315) | 2.907 (.004)* | 0.002 (0.016) | (0;0.414) | 10.025 (.187) | 5.7 |

| Verbal memory delayed recognition | 2 | 98 | 0.035 (0.127) | (−0.214;0.284) | 0.273 (.785) | 0.009 (0.073) | (0;52.255) | 1.199 (.274) | 16.6 |

| Verbal memory immediate | 8 | 192 | 0.129 (0.071) | (−0.009;0.268) | 1.832 (.067) | 0 (0.020) | (0;0.271) | 6.601 (.472) | 0 |

| Visual memory figures delayed | 2 | 88 | 0.271 (0.183) | (−0.087;0.629) | 1.482 (.138) | 0.035 (0.110) | (0;79.131) | 1.810 (.178) | 44.8 |

| Visual memory figures immediate | 3 | 109 | 0.335 (0.188) | (−0.033;0.703) | 1.784 (.074) | 0.066 (0.107) | (0;3.392) | 5.752 (.056) | 63.1 |

| ROCF recall | 2 | 40 | 0.562 (0.244) | (0.083;1.042) | 2.300 (.021)* | 0.060 (0.175) | (0;>100) | 1.926 (.165) | 48.1 |

| Picture naming | 6 | 119 | 0.134 (0.103) | (−0.067;0.336) | 1.309 (.191) | 0.013 (0.039) | (0;0.248) | 5.581 (.349) | 21.1 |

| Reading | 3 | 51 | 0.219 (0.162) | (−0.099;0.536) | 1.351 (.177) | 0.022 (0.080) | (0;2.463) | 2.527 (.283) | 26.9 |

| Token test | 3 | 52 | −0.095 (0.158) | (−0.404;0.214) | −0.601 (.548) | 0.020 (0.075) | (0;3.385) | 2.857 (.240) | 27.0 |

Note. K = number of included studies, = total number of included patients in a meta-analysis, Est. (SE) = Average effect size estimate and standard error, CI = confidence interval, z-value (P) = z-value and two-tailed P-value to test the null-hypothesis of no effect. (SE) = estimated between-study variance in true effect size using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator and corresponding standard error, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the between-study variance obtained with the Q-profile method,53Q-value (P) = Q-statistic and p-value to test the null-hypothesis of no between-study variance. -statistic = percentage of variance that can be attributed to between-study variance.

* indicates a P-value <.05. Tests with moderate effect sizes are indicated in bold.

The majority of studies used the MMSE screening instrument (14 out of 27 studies, 51.9%), and phonemic fluency and verbal memory tests (8 out of 27 studies, 29.6%) in their follow-up.

A longitudinal change (1–2 years posttreatment) of moderate effect size was found with an increase in ROCF recall (est = 0.562, 95% CI = 0.083; 1.042) and a decrease in semantic fluency (est = −0.502, 95% CI = −1.021; 0.017). Across all tests, significant between-study heterogeneity (93.9 < I2 < 97.6) was detected in 5 out of 21 tests.

Results of the sensitivity analyses showed that the observed effect sizes were robust. Furthermore, findings were confirmed in the equal-effect model (Supplementary Table S3), with again a moderate effect size for increase in ROCF recall (but somewhat smaller effect size for decrease in semantic fluency, est = −0.434). After excluding high-risk of bias studies, effect sizes were consistently small (0.120 < est < 0.388), which can be related to high variability, the low number of remaining studies, but also lower bias in these studies (Supplementary Table S4).

Longitudinal z-scores were reported for nine cognitive tests in 2 to 3 studies. Standardized scores of patients declined over time for digit span backward (z-difference = −0.081) and showed relative improvement over time for the remaining tests (coding, phonemic fluency, TMT A, TMT B, picture naming, immediate verbal memory, and delayed verbal memory; 0.052 < z-difference < 11.334; Supplementary Table S5). These findings were robust based on the sensitivity analyses. Based on the equal-effect model, all findings were confirmed but coding additionally showed a decline over time (z-difference = −0.135; Supplementary Table S6). Findings remained stable after excluding high-risk bias studies (Supplementary Table S7), albeit based on merely 2 studies per test (and only available for 4 tests).

Finally, the meta-regression model including the moderator of additional practice (patients who received interval testing: yes or no) showed that changes in raw scores of MMSE, digit span forward, semantic and phonemic fluency, and immediate visual memory figures differed between patients with versus patients without interval testing with moderate effect sizes (Table 4). More specifically, patients without interval testing showed declines of moderate size in MMSE (b0 = −0.630, 95% CI = −1.485; 0.225), phonemic fluency (b0 = −0.765, 95% CI = −2.103; 0.574), digit span forward (b0 = −0.878, 95% CI = −1.585; −0.172) and semantic fluency (b0 = −0.868, 95% CI = −1.63; −0.106) versus stability in patients with interval testing. Furthermore, patients without interval testing showed relatively stable scores of immediate visual memory figures (b0 = 0.121), while patients with interval testing showed moderate increases of 0.620 (b0 + b1). These findings were confirmed in the equal effect model. As longitudinal z-scores were only reported in a maximum of 3 studies, meta-regression analysis using the moderator interval testing was not performed for z-scores.

Table 4.

Results of meta-regression of longitudinal studies with moderator to study practice effects in studies reporting mean raw test scores

| Test | k | k1 | b0 (SE) | 95% CI b0 | z-value (P) b0 | b1 (SE) | 95% CI b1 | z-value (P) b1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 14 | 9 | 1658 | −0.630 (0.436) | (−1.485;0.225) | −1.444 (.149) | 0.603 (0.482) | (−0.341;1.547) | 1.252 (.211) |

| Coding/substitution | 5 | 2 | 75 | 0.039 (0.207) | (−0.366;0.444) | 0.187 (.852) | 0.037 (0.370) | (−0.689;0.763) | 0.100 (.920) |

| TMT A | 5 | 2 | 135 | 0.037 (0.135) | (−0.228;0.302) | 0.274 (.784) | 0.300 (0.174) | (−0.041;0.642) | 1.725 (.085) |

| Digit span forward | 4 | 3 | 228 | −0.878 (0.360) | (−1.585;−0.172) | −2.437 (.015)* | 0.826 (0.428) | (−0.014;1.665) | 1.928 (.054) |

| Semantic fluency | 5 | 3 | 280 | −0.868 (0.389) | (−1.630;−0.106) | −2.233 (.026)* | 0.615 (0.504) | (−0.372;1.602) | 1.221 (.222) |

| Phonemic fluency | 8 | 5 | 368 | −0.765 (0.683) | (−2.103;0.574) | −1.120 (.263) | 0.960 (0.864) | (−0.733;2.653) | 1.111 (.266) |

| TMT B | 5 | 2 | 125 | 0.210 (0.196) | (−0.174;0.595) | 1.072 (.284) | 0.080 (0.297) | (−0.502;0.661) | 0.268 (.789) |

| Digit span backward | 6 | 3 | 258 | −0.428 (0.460) | (−1.330;0.474) | −0.930 (.353) | 0.441 (0.653) | (−0.840;1.721) | 0.675 (.500) |

| Verbal memory delayed recall | 8 | 4 | 263 | 0.054 (0.118) | (−0.177;0.285) | 0.456 (.648) | 0.224 (0.150) | (−0.070;0.518) | 1.493 (.135) |

| Verbal memory immediate | 8 | 4 | 192 | 0.089 (0.109) | (−0.125;0.302) | 0.812 (.417) | 0.070 (0.143) | (−0.210;0.351) | 0.492 (.623) |

| Visual memory figures immediate | 3 | 1 | 109 | 0.121 (0.168) | (−0.209;0.451) | 0.718 (.473) | 0.499 (0.209) | (0.090;0.908) | 2.390 (.017)* |

| Picture naming | 6 | 1 | 119 | 0.004 (0.108) | (−0.208;0.215) | 0.033 (.974) | 0.320 (0.220) | (−0.111;0.751) | 1.454 (.146) |

| Reading | 3 | 2 | 51 | 0.392 (0.301) | (−0.198;0.982) | 1.302 (.193) | −0.254 (0.372) | (−0.983;0.474) | −0.684 (.494) |

Note: The effect sizes of time effects in patients who had no interval testing (ie, b0) are interpreted based on Cohen’s rules-of-thumb15. Differences in time effects in patients who did have additional interval testing (vs. the ones who did not) (ie, b1) are summed with this baseline time effect to interpret the effect sizes of change in the patients who had additional interval testing (again based on Cohen’s rules-of-thumb). CI = confidence interval, k = number of included studies in the analysis, k1= number of studies that had additional test assessments between baseline and follow-up, = total number of included patients in a meta-analysis, SE = standard error, * indicates a p-value <.05. Tests of moderate or high effect size are indicated in bold for estimates of b0 and underlined for b0+b1.

Based on the subgroup analysis comparing longitudinal studies with majority of LGG (k = 76/n = 108) versus HGG patients (k = 32/n = 108), a more profound cognitive decline of at least moderate effect size was observed in the performance of digit span forward (b1 = −0.867) and backward (b1 = −0.911), semantic (b1 = −0.704) and phonemic fluency (b1 = −0.809), and MMSE (b1 = −0.514) in HGG patients, while the opposite effect was encountered for coding/substitution (b1 = 0.698) (see Supplementary Table S13).

Cross-sectional results; status of cognitive performance

Cross-sectional data of patients versus controls (or norm data) at follow-up at least 1 year posttreatment (Mdn = 36.5 months) were available in 12 studies, covering 14 different test materials. Six out of these twelve studies included a control group (Table 2); all other used (published) normative data to derive z-scores. Results of the random-effects model based on cross-sectional raw scores can be found in Table 5. For cross-sectional comparisons between patients and controls (or norms), most studies provided data on semantic fluency and verbal memory tests (8 out of 12 studies, 66.7%).

Table 5.

Results of (random-effects) meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies reporting mean raw test scores

| Test | k | Est. (SE) | 95% CI | z-value (P) | (SE) | 95% CI | Q-value (P) | -statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 2 | 2008 | −3.513 (0.417) | (−4.330;−2.695) | −8.425 (<.001)* | 0.132 (0.952) | (0;>100) | 1.244 (.265) | 19.6 |

| Coding/substitution | 4 | 890 | −0.256 (0.548) | (−1.330;0.817) | −0.468 (.640) | 1.082 (0.980) | (0.263;17.144) | 35.802 (<.001)* | 93.4 |

| TMT A | 4 | 538 | −0.227 (0.287) | (−0.789;0.335) | −0.791 (.429) | 0.270 (0.268) | (0.054;3.953) | 23.659 (<.001)* | 88.0 |

| Digit span forward | 2 | 402 | −0.410 (0.100) | (−0.607;−0.214) | −4.087 (<.001)* | 0 (0.030) | (0; 10.317) | 0.062 (.803) | 0 |

| Semantic fluency | 8 | 2511 | −0.628 (0.223) | (−1.066;−0.190) | −2.809 (.005)* | 0.345 (0.213) | (0.123;1.711) | 70.037 (<.001)* | 91.5 |

| Phonemic fluency | 3 | 938 | −0.388 (0.551) | (−1.469;0.692) | −0.705 (.481) | 0.822 (0.913) | (0.173;33.907) | 35.186 (<.001)* | 92.9 |

| Stroop speed interference task | 5 | 642 | −0.763 (0.261) | (−1.275;−0.251) | −2.922 (.003)* | 0.268 (0.240) | (0.051;2.779) | 19.993 (<.001)* | 83.9 |

| TMT B | 4 | 538 | −0.521 (0.223) | (−0.958;−0.084) | −2.335 (.020)* | 0.145 (0.161) | (0.016;2.226) | 13.638 (.003) | 79.5 |

| Finger tapping dominant hand | 2 | 625 | −0.650 (0.425) | (−1.483;0.183) | −1.530 (.126) | 0.156 (0.511) | (0;>100) | 1.761 (.184) | 43.2 |

| Finger tapping non-dominant hand | 2 | 625 | −0.424 (0.395) | (−1.197;0.350) | −1.074 (.283) | 0.107 (0.440) | (0;>100) | 1.523 (.217) | 34.3 |

| Digit span backward | 3 | 426 | −0.583 (0.099) | (−0.778;−0.388) | −5.873 (<.001)* | 0 (0.030) | (0;6.613) | 2.370 (.306) | 0 |

| Verbal memory delayed recall | 8 | 1410 | −0.056 (0.203) | (−0.455;0.342) | −0.277 (.782) | 0.258 (0.175) | (0.072;1.321) | 34.857 (<.001)* | 87.1 |

| Verbal memory delayed recognition | 2 | 513 | 0.251 (0.561) | (−0.848;1.351) | 0.448 (.654) | 0.585 (0.893) | (0.079;>100) | 13.601 (<.001)* | 92.6 |

| Verbal memory immediate | 8 | 1410 | −0.172 (0.220) | (−0.603;0.259) | −0.782 (.435) | 0.312 (0.205) | (0.097;1.471) | 44.979 (<.001)* | 88.9 |

Note. k = number of included studies, = total number of included patients in a meta-analysis, Est. (SE) = Average effect size estimate and standard error, CI = confidence interval, z-value (P) = z-value and two-tailed P-value to test the null-hypothesis of no effect. (SE) = estimated between-study variance in true effect size using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator and corresponding standard error, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the between-study variance obtained with the Q-profile method (Viechtbauer, 2007),53Q-value (P) = Q-statistic and P-value to test the null-hypothesis of no between-study variance. -statistic = percentage of variance that can be attributed to between-study variance. * indicates a P-value <.05. Tests with moderate or high effect sizes are indicated in bold.

Of the 14 cross-sectional tests, lower performance in patients compared to controls was observed with moderate effects sizes in 6 different tests (−3.513 < est < −0.521), including the digit span backward (est = −0.583, 95% CI = −0.778 ;−0.388), semantic fluency (est = −0.628, 95% CI= −1.066; −0.190), Stroop speed interference task (est = −0.763, 95% CI = −1.275; −0.251), and TMT B (est = −0.521, 95% CI = −0.958; −0.084), finger tapping dominant hand (est = −0.650, 95% CI = −1.483; 0.183) and large effect sizes in MMSE (est = −3.513, 95% CI = −4.330; −2.695). These effect sizes were confirmed in the equal-effect model (Supplementary Table S8). After excluding high-risk bias studies, all abovementioned effects remained of moderate size (Supplementary Table S9).

Compared to the longitudinal studies, heterogeneity across studies, was higher in the cross-sectional studies, reaching significance in 9 out of 12 test scores (79.5 < I2 < 93.9).

Z-scores were available in 4 cross-sectional studies for 10 tests where the performance of patients was lower than the norm on 8 tests (coding, TMT A, TMT B, semantic fluency, phonemic fluency, picture naming, verbal memory immediate, and delayed recall), which ranged between −0.083 < z < −0.991 (Supplementary Table S10), These findings were confirmed in the equal-effect model (Supplementary Table S11). Since all cross-sectional studies using z-scores were defined as low risk for bias, no additional validity analysis was performed.

Based on the subgroup analysis comparing cross-sectional studies with majority of LGG (k = 59/n = 94) versus HGG patients (k = 35/n = 94), a more severe cognitive impairment of at least moderate effect size was observed on the performance of digit span backward (b1 = −0.718), semantic (b1 = −0.538) and phonemic fluency (b1 = −1.662), TMT A (b1 = −1.022) and B (b1 = −0.766) in HGG compared to LGG patients, while the opposite effect was encountered for coding/substitution (b1 = 2.221) (see Supplementary Table S14).

Discussion

Scientific evidence supporting future guidelines on cognitive follow-up in glioma patients was not quantitively summarized before. In this study, we aimed to summarize the available data on longer-term outcomes of specific cognitive tests for this population. In general, we can conclude that after taking additional interval testing (potential practice effects) into account, patients’ performance in clinical trials remained stable or declined over time (pretreatment vs. 12–24 months follow-up), and that after at least 1 year, patients scored lower than controls on several cognitive tests, and worse than the norm on most of them.

More specifically, based on moderation analyses of the longitudinal data, decline in performance of medium and large effect sizes were found for MMSE, digit span forward, semantic and phonemic fluency in patients who had no interval testing, while these scores remained stable in patients who did. Thus, practice effects may have masked the cognitive decline in performance on these tests over time. This suggests specific cognitive decline in immediate attention and verbal fluency, which can sometimes be subtle, and therefore easily overlooked, certainly if no correction for interval assessment (ie, more practice) is performed. Similarly, scores improved for immediate visual memory (of figures) if patients had interval testing, but remained stable if they did not. By contrast, in the initial longitudinal model, in which no covariate for interval testing was included, such decline was only encountered for semantic fluency, while improvement was also found for visual memory (ROCF recall). Hence, if there is no correction for interim practice effects, the impact of treatment could be largely underestimated in longitudinal trials.54–56 Unfortunately, across the existing longitudinal studies, 8 out of 27 studies (30%) reported whether and how they applied corrections for practice effects. We also note that although we evaluated practice effects of additional assessments within the interval between pretreatment and follow-up, such effects may also already have occurred in the case of assessment at these 2 timepoints only,56 which can be related to instruction knowledge. This may have resulted in a too-optimistic perspective regarding cognitive change over time-based on the longitudinal studies. For longer intervals, it becomes even more challenging to differentiate practice effects from actual changes and within-person variability. Although practice effects can partly explain the lack of encountered cognitive decline, it should be noted that many patients have cognitive impairment already before treatment. The tumor itself and its related stress already have a substantial impact on baseline cognitive functioning.48,57 Therefore, effects of change over time may be smaller if measured from baseline (when cognitive performance is already low) to 1 or 2 years follow-up, as compared to the size of the deviation from the norm only at a single longer-term follow-up timepoint. The tumor effects of infiltration, compression, and edema can further disrupt the neural connections and affect specific cognitive functions.3,58 While treatment (including surgery) and tumor control could thus (temporarily) improve the patient’s cognitive functioning,5 this may occur without full restoration of patients’ prior functioning level due to permanent damage. The tumor location and type, as well as the extent of surgery59–61 and other treatments, are considerable factors influencing the patient’s cognitive risk profile.

When comparing patients to controls at least 1-year posttreatment (median 36.5 months, maximum of 22 years) in the cross-sectional dataset, patients showed lower raw mean scores with moderate effect sizes than controls on several tests including the MMSE, digit span backward, semantic fluency, Stroop speed interference task, TMT B and finger tapping. The majority of available z-scores were also lower than the norm for coding, TMT A & B, semantic and phonemic fluency, picture naming, and verbal memory (immediate and delayed recall). Notably, larger effect sizes and more significant results values were observed in the cross-sectional designs compared to the longitudinal designs, indicating that the scores of patients deviate substantially from the norm, while medium-sized declines in scores over one (maximum of 2) year(s) with a median of 12 months were only found semantic fluency. Hence, it could be the case that decline over time on certain cognitive tasks occurs only later than 1-year post-baseline. In previous studies, patients with LGGs showed stable cognitive function 6 years after radiotherapy, but worse functioning after 12 years.62,63 Given that in the longitudinal studies, we focused on the time point of 1 to 2 years follow-up, we cannot address the question of later delayed cognitive decline at this point. A nonlinear pattern of short-term improvement and subsequent decline in scores could be treatment-related (eg, short-term improvement post-surgery5 and long-term decline post-radiation6).

Our results are particularly interesting since this is the first work analyzing scores from individual tests in a meta-analysis, which could be more sensitive and more specific to detect subtle cognitive function changes than cognitive domains as included in previous meta-analyses.5,6 Furthermore, due to the increase in the number of studies, we included a larger sample size (4078 patients with gliomas (37 studies) compared to 2406 patients (9 studies) and 313 patients (11 studies) by Lawrie et al.,6 and Ng et al.,5 respectively). Other strengths are that we consulted multiple databases, and included data between 1 and 2 years (or more) after therapy. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that considered the role of practice effects in cognitive test scores of glioma patients, which showed the importance of correcting for such effects in longitudinal studies.

To increase our knowledge of incidence, severity, individual risk factors, and causes of cognitive deficits in glioma patients, future trials with larger sample sizes and consistent timing and use of materials are needed. Based on the results of these meta-analyses, we would encourage clinical trials with longitudinal designs to implement a core test battery at least including a digit span forward, semantic, and phonemic fluency test to detect cognitive decline, while correcting for practice. Methods to limit the impact of practice effects, such as alternate forms/parallel versions or having longer interval periods, should be considered,8,55 to help decrease memorization of specific test items and to better detect cognitive decline over time. Other methods to correct for practice effects (including memory for test procedures) are, calculating reliable change indices that specifically correct for practice effects (eg, Chelune 199364) and standardized regression-based change scores.8,65 Ideally, reliable change index scores are calculated based on standardized scores at baseline and follow-up (incorporating age, sex, and education in the normative data). However, for the calculation of this index, longitudinal normative data (ie, healthy controls) from repeated testing is required. For each of these steps and choices in designs of future studies or trials, neuropsychology expertise is required, which should consistently be embedded in international multidisciplinary neuro-oncology groups.

If longitudinal trials focus on acute effects (within 1 year), we recommend to use similar test materials as recommended for (1 year) follow-up (ie, digit span forward, semantic and phonemic fluency), to measure evolution over time. It is highly important for such interim repeated measures to always use alternative forms, to limit practice effects.

Based on our results, consideration of practice effects certainly holds for the MMSE, digit span forward, semantic and phonemic fluency, for which moderate declines were found if potential practice effects of interim assessment(s) were taken into account (as moderator), as well as for visual memory tasks (ROCF and figures), which can improve, if this is not taken into account.66 Surprisingly, in contrast to the immediate attention digit span forward task, such a practice effect was not found for the working memory digit span backward task. On the one hand, this could be explained by the increased executive load of the backward task which may outweigh the practice effects. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that the working memory of patients is more affected from baseline onwards (as can be seen in the cross-sectional results), potentially leading to a smaller practice effect.

However, longitudinal normative data or acquisition from controls are required to optimally correct for practice on group or individual level (eg, in case of using Reliable Change Indices66).

The preferred and most sensitive measures to estimate deviations from the norm based on raw scores, appeared to be digit span backward, semantic fluency, Stroop speed interference task, TMT B, and finger tapping, which could therefore be recommended to be implemented in cross-sectional studies. In case of using standardized z-scores, fewer differential effects between the tasks were found. Surprisingly, we did not find verbal memory (word list learning) to be sensitive to change nor group differences in these meta-analyses. This could possibly be explained by memory issues that already exist at baseline in glioma patients.67 Furthermore, tumors can possibly lead to reduced learning effects for verbal memory in patients compared to controls, masking true impairment or existing decline in verbal memory over time.

We would recommend not to focus on screening instruments only (eg, MMSE), as these tests appear to be moderately sensitive to practice, possibly insensitive to subtle changes, not tailored to oncological populations (but rather to aging-related neurological diseases),68,69 unspecific and heterogeneous across studies.

The preferred reporting strategy for the interpretation of impairment would be using z-scores.70 However, the number of studies reporting z-scores appeared to be limited (k ≤3 for longitudinal designs, 2 ≤k≤8 for cross-sectional designs). Furthermore, available normative data are often region specific and outdated, restraining international studies and collaborations. (Inter)national datasets of the most frequently used cognitive tests, assembled by multicenter collaborative efforts, are thus essential to obtain high-quality cognitive data.

Based on our findings, recommendations for future trials are provided in the summary box below. The proposed test selection covers a minimal core battery to assess important cognitive outcomes, based on the measures that were most consistently sensitive in previous glioma trials. Additional cognitive subtests might be needed to address other domains of functioning or specific hypotheses. Moreover, a focused but adequately broad cognitive test battery, which also includes cognitive domains of memory and executive function, would be advised to use. This would enable us to optimally capture possible cognitive impairment or changes over time in glioma patients.

Uniform cognitive outcome data would allow the community to develop prediction models to estimate the risk of cognitive decline at individual level.30,71 These models could help pave the path toward patient-tailored care.

While this study certainly has its merits, a few limitations need to be noted. First, computerized tests were excluded from the analyses, as their instructions and required skills can be different from traditional pen-and-paper tasks, which would complicate pooling of these data. Second, even though multiple effect sizes were of moderate size, we need to be aware that only a few studies provided data for each analysis of subtests (for raw test scores: 2 ≤ k ≤ 0.14, median k = 4, for z-scores: 2 ≤ k ≤ 8, median k = 2 for longitudinal and k = 4 cross-sectional design), since we performed a separate analysis for each test. Third, significant heterogeneity (with large confidence intervals) was noted across studies, which is inherent in the domain of cognitive outcomes in neuro-oncological patients. For instance, even in the case of k = 14 studies reporting on MMSE scores, confidence intervals were very wide with significant heterogeneity (eg, I2 = 96.8). Our results provide additional insights into the possible impact of standard glioma treatments on neurocognitive functioning, compared to existing large-scale interventional trials in other neuro-oncological patients (eg, brain metastases), which for instance show improvements in memory (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test) and executive functioning (TMT), but not on fluency tasks (COWA) after hippocampal sparing radiotherapy.72 More trials will be required for possible meta-analyses on beneficial effects of interventions. Cognitive outcomes can also be influenced by many confounding factors that we did not take into account (tumor location/size, neurosurgical procedures, the radiation dose, medication (eg, anticonvulsants), volume, fractionation, adjuvant chemotherapy, and possible complications (eg, hydrocephalus, endocrine problems), and time of follow-up4,6). The variety in follow-up intervals in the cross-sectional studies was wide, ranging from 1 year to maximum of 22 years after baseline. In the longitudinal analysis, this variety was restricted by only including the outcomes reported between 12 and 24 months after therapy. By including the moderator for additional practice (measured as interval testing yes vs. no), we aimed to study the impact of additional practice effects. However, interval testing is only a rough measure of the actual practice a patient had. As abovementioned, different approaches in correction for practice could have been used as well. Moreover, we cannot exclude potential relationships between the number of assessments in a study and its main research question or population. For instance, the expected prognosis of patients could affect decisions on the selected design. More specifically, the shorter expected lifespan in HGGs, could motivate researchers to add interim assessments, or to select shorter intervals between the assessments.

Also, tumor grade could be an important confounding factor.73 It was evidenced that HGGs are associated with stronger decreases in cognitive performance compared to LGGs, which affect cognition to a lesser extent than HGGs.73 Based on the additional subgroup analysis (majority of LGG vs. HGG patients), we confirm this effect for most tests. Hence, even though the majority of patients were diagnosed with LGGs, we cannot exclude the results of the main analysis to be partly driven by larger effects in studies including a majority of HGG patients. We also note that the analyses taking tumor grade into account, were based on fewer studies per test (k ranging from 3 to 14), so the meta-analytic estimates have wide confidence intervals and results should therefore be interpreted with much caution. Moreover, since the WHO classification of gliomas changed in 2021,74 this former classification based on grade is clinically not very meaningful anymore. The more significant prognostic factor nowadays is the IDH1 and IDH2 mutational status Unfortunately, this information was only available in a minority of studies (k = 3/10 cross-sectional45,49,50 and k = 4/27 longitudinal studies20,27,30,42). The available data to date remain insufficient to perform meaningful subgroup analyses concerning the other confounding factors. Furthermore, we could not statistically test and correct for selection bias (only assessments that were repeatedly reported were analyzed) or publication bias (studies with significant results might have higher chances to be published) due to the small number of studies per meta-analysis. Finally, our results can partly be driven by a few large cohort studies. Many more large-scale studies and data-sharing agreements are required to validate our findings in future research.

Recommendations for Future Trials:

Longitudinal trials:

-

Include as a minimal core set*:

Digit span forward

Semantic and phonemic fluency test

-

Limit practice effects by:

using alternate forms

calculating standardized regression-based scores/RCI

recruiting longitudinal normative data

Cross-sectional trials:

-

Include as a minimal core set*:

Digit span backward

Semantic fluency test

Stroop speed interference task

TMT B

Finger tapping

-

Expand this set for complete assessment of*:

a specific tool (eg, TMT A)

additional cognitive domains (e.g. memory, executive function)

-

Controls.

Recruit healthy controls matched for age, gender, and education

(certainly, if no updated and regional norms are available)

Preferred reporting strategies:

-

Use of norms

Cite and report means and SDs of used norms per test

-

Definition of impairment

Use cutoff of Z<-2 for one specific test, and Z<-1.5 for the combination of tests

Conclusion

Cognitive functioning is a commonly affected outcome in glioma patients after multimodal therapy with a substantial impact on patients’ health-related quality of life. Based on our findings, digit span backward, semantic fluency, Stroop interference test, TMT B and finger tapping might be most sensitive to estimate cognitive longer-term impairment in glioma patients versus controls. Longitudinal declines over time were found in digit span forward, semantic, and phonemic fluency scores, albeit more subtle and only after taking potential practice effects into account. These tests could therefore be valuable to measure potential decline over time in longitudinal designs, when adjusting for practice. Uniformization, and correction for practice effects for multiple test materials will be crucial to move forward in our understanding of cognitive outcomes in glioma patients. With a successful adaptation of this standard, earlier detection of cognitive impairment or decline could be accomplished, and large datasets and prediction models could be developed to guide patient-tailored follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Emilie Bartsoen, MSc, (EB) for her assistance in risk of bias assessments and in the screening of abstracts.

Contributor Information

Laurien De Roeck, Department of Oncology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Radiation Oncology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Brain and Cognition, Leuven Brain Institute (LBI), KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Céline R Gillebert, Department of Brain and Cognition, Leuven Brain Institute (LBI), KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Centre for Translational Psychological Research (TRACE), Hospital East-Limbourg, Genk, Belgium.

Robbie C M van Aert, Department of Methodology and Statistics, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Amber Vanmeenen, Department of Brain and Cognition, Leuven Brain Institute (LBI), KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Martin Klein, Department of Medical Psychology, Amsterdam UMC location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Martin J B Taphoorn, Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; Department of Neurology, Haaglanden Medical Center, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Karin Gehring, Department of Cognitive Neuropsychology, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands; Department of Neurosurgery, Elisabeth-TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Maarten Lambrecht, Department of Brain and Cognition, Leuven Brain Institute (LBI), KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Oncology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Radiation Oncology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Charlotte Sleurs, Department of Brain and Cognition, Leuven Brain Institute (LBI), KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Oncology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Department of Neurosurgery, Elisabeth-TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Funding

LDR is supported by a strategic basic research PhD fellowship from the Flemish Foundation of Scientific Research (FWO-Vlaanderen, SB/1SE5722N). CS was supported by a senior postdoctoral fellowship from the Flemish Foundation of Scientific Research (FWO-Vlaanderen, grant no. 12Y6122N) during the data acquisition and analysis phase of this work.

Author Contribution

The review was conceptualized by LDR, CRG, AV, ML, and CS. AV, CS, and LDR have performed the screening and selection of the articles. Design of the statistics and meta-analyses were defined by LDR, CRG, RVA, KG, and CS. RVA performed and LDR, RVA, KG, and CS interpreted the statistical analyses. LDR and CS wrote the initial version of the manuscript. All coauthors (LDR, CRG, RVA, AV, MK, MT, KG, ML, and CS) have substantially contributed to the reviewing and editing of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Ohgaki H. Epidemiology of brain tumors. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:323–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boone M, Roussel M, Chauffert B, le Gars D, Godefroy O.. Prevalence and profile of cognitive impairment in adult glioma: A sensitivity analysis. J Neurooncol. 2016;129(1):123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morshed RA, Young JS, Kroliczek AA, et al. A neurosurgeon’s guide to cognitive dysfunction in adult glioma. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsons MW, Dietrich J.. Assessment and management of cognitive symptoms in patients with brain tumors. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2021;41:e90–e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ng JCH, See AAQ, Ang TY, et al. Effects of surgery on neurocognitive function in patients with glioma: A meta-analysis of immediate post-operative and long-term follow-up neurocognitive outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;141(1):167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawrie TA, Gillespie D, Dowswell T, et al. Long-term neurocognitive and other side effects of radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, for glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8(8):CD013047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]