Abstract

Aromatic maturity parameters were evaluated via closed-system pyrolysis experiments using a Mesozoic lacustrine source rock from the Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin, thereby ensuring a uniform source. Pulverized rock aliquots (200 mg) were reacted with water at temperatures ranging from 250 to 550 °C at 5 °C/min, and the aromatic fractions of expelled oil and extracts of the solid residue were analyzed by GC–MS. The experiments showed that the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the oil and extractable organic matter (EOM) of source rock had different evolutionary characteristics. With the increase in the thermal evolution degree, the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the EOM showed the characteristics of ″increased early (Ro < 0.80), unchanged middle (Ro = 0.80–2.00%), decreased lately (Ro > 2.00%)″. While the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the expelled oils continuously increased, as the Ro values increased from 0.62 to 2.39%, the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons gradually increased from 8 to 46%. With increased maturity, the relative abundance of 1–3-ring aromatic hydrocarbons continuously decreased, as observed in the phenanthrene homologs. Meanwhile, the relative abundance of 4+-ring aromatic hydrocarbons continuously increased, as seen in chrysene homologs. It was suggested that the effects of maturity on the composition of aromatic hydrocarbons might not be sufficiently obvious. The effective application range of the alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters (2-/1-methylnaphthalenes, (2,6- + 2,7-)/1,5-dimethylnaphthalenes, 2,3,6-/(1,4,6- + 1,3,5-) trimethylnaphthalenes, and (2,3,6- + 1,3,7-)/(1,4,6- + 1,3,5- + 1,3,6-) trimethylnaphthalenes) and the alkyldibenzothiophene maturity parameters (4-/1-methyldibenzothiophenes, 4,6-/(1,4- + 1,6-) dimethyldibenzothiophenes, and (2,6- + 3,6-)/(1,4- + 1,6-) dimethyldibenzothiophenes) was 0.84–2.06% Ro. The alkylphenanthrene-related maturity parameters had a wide application range for lacustrine source rocks with an Ro < 2.06%. These parameters included 1.5 × (2- + 3-)/(phenanthrene +1- + 9-) methylphenanthrenes, 3 × 2-/(phenanthrene + 1- + 9-) methylphenanthrenes, (2- + 3-)/(1- + 9-) methylphenanthrenes, 2-/1-methylphenanthrenes, (3- + 2-)/(1- + 2- + 3- + 9-) methylphenanthrenes, 2-/(1- + 2- + 3- + 9-) methylphenanthrenes, and 2,7-/1,8-dimethylphenanthrenes. In addition, the effective applicable range of the methylnaphthalene-related maturity parameter 3-/1-methylchrysenes was an Ro value less than 1.79%. The results clarified the validity scope of some aromatics’ maturity parameters and provided a theoretical basis for the scientific application of these parameters.

1. Introduction

Maturity is an important parameter to characterize the effectiveness of the hydrocarbon generation of source rocks and also an important index to determine the properties of oils.1,2 Commonly used methods to evaluate the maturity include the vitrinite reflectance method (Ro method) and the maximum peak temperature of the rock pyrolysis method (Tmax method).3,4 However, these methods have certain limitations in their application because they are often unable to evaluate the maturity of the oils and the Ro method cannot be adapted to marine source rocks due to the lack of vitrinite.5 Biomarkers are ubiquitous in organic matters, and isomerization of biomarker compounds can exhibit an obvious response to maturity. Thus, they can be used as effective indicators for the maturity evaluation of source rocks and oils.3 In particular, compared with saturated hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons have the characteristics of a stronger biodegradation resistance, a higher content, and a wider distribution.6,7 Many aromatic maturity parameters have been established by previous studies, but their application has not yet been proven effective.3,8−10 This may be due to the fact that controlling factors on the distribution of aromatic hydrocarbons are very complex, and these parameters thus have their own respective effective ranges of application.4 At the same time, previous understandings of the effective application ranges of these parameters have differed widely.4,11,12 For example, Chakhmakhchev et al.13 believed that the parameter MDR (4-/1-methyldibenzothiophene) could indicate maturity over a wide range. Zhou et al.14 observed that this parameter was mainly affected by salinity in the early thermal evolution stage, in addition to maturity. Lacustrine source rocks are widely distributed, especially in the Mesozoic formations of northern China. Lacustrine deposits are a field of interest for petroleum exploration and exploitation in China, with several large oil fields having been discovered in these lacustrine basins—including the Ordos, Songliao, and Bohaiwan, among others.15−19 Comparing these with marine source rocks, the heterogeneity of lacustrine source rocks is stronger and their influencing factors on aromatic maturity parameters are more complex. The same is true for oils generated by lacustrine source rocks.20−22 However, previous studies on aromatic maturity parameters have largely focused on application; the validity and mechanism have seldom been considered.

The applicability of some aromatic hydrocarbons parameters has been explored, but the samples were basically mixed samples from multilayers in a certain area in previous studies,4,11 so the impurity of samples had a certain impact on the results. Pyrolysis simulation experiments made it possible to study the hydrocarbon generation and hydrocarbon expulsion characteristics of the source rocks. They also provided an effective way to study, in depth, the evolutionary mechanisms of molecular markers.23−26 By analyzing the experimental solid residues and hydrocarbon products, an immature-to-over-mature thermal evolution sequence could be established, and the evolutionary characteristics and validity of aromatic parameters could be studied.27−31 Moreover, in comparing mixed source rock/oil samples in a certain area, as has occurred in some studies, the samples obtained from thermal simulation experiments were wholly the same type, making end-member analysis possible.

In this study, high-temperature and high-pressure pyrolysis simulation experiments were carried out. The samples were Mesozoic lacustrine source rocks from the Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin. Additionally, the vitrinite reflectance (Ro) of the experimental solid residues was measured, and the aromatic hydrocarbon fractions from the extracts and expelled oils were analyzed using the GC–MS method. Based on these data, we then discuss the validity of some aromatic maturity parameters.

2. Geological Settings

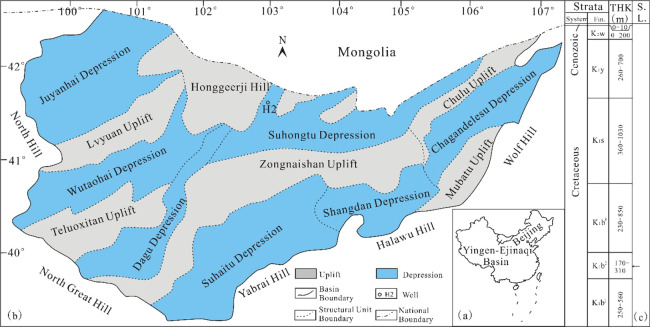

The Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin is a Mesozoic-Cenozoic rift-related basin located on the northeastern border of Inner Mongolia, China (Figure 1a). The basin was developed on Precambrian crystalline block or Paleozoic folded basement.32−36 Since the Mesozoic, the basin has experienced four evolution stages: Triassic–Early Middle Jurassic transtensional fault-induced subsidence, Late Jurassic compressional uplift-induced denudation, Early Cretaceous extensional rifting, and Late Cretaceous Paleogene subsidence.34 The Suhongtu Depression (longitude 102°05′ to 106°00′ and latitude 40°50′ to 41°50′), located in the northern part of the Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin, is a second-order structural unit of the basin (Figure 1b).19,37 The sedimentary fill in the Suhongtu Depression contains the Lower Cretaceous Bayingobi formation (K1b), Suhongtu formation (K1s), Yingen formation (K1y), Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai formation (K2w), and Cenozoic covering succession. The Bayingobi formation can be divided into three members, namely, the first member of the Bayingobi formation (K1b1), the second member of the Bayingobi formation (K1b2), and the third member of the Bayingobi formation (K1b3), from bottom to top, respectively (Figure 1c).19,33,37 K1b2 was deposited in deep-lake to semi-deep-lake environments, so it mainly formed fine-grained sediments. Moreover, the water environment at that time was brackish and weak reduction-weak oxidation, as it can be seen from Figure 2a that the source rocks generally have a high gammacerane content. Therefore, K1b2 formed the main source rocks in the basin.38−41 The lithology of the source rocks was mainly dark gray-to-black lime mudstone. The thickness of the effective source rock was 0–303 m, and it distributed throughout the sag (Figure 2b). The maturity of source rocks varied greatly (Figure 2b), as the Ro values at the high part and center of the sag were 0.51 and 1.75%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Generalized map showing the location (a), structural unit division (b), and stratigraphic column (c) of the Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin (sample locations are plotted on the map. Fm.: formation; THK: thickness; S.L.: sampling locations).

Figure 2.

Mass chromatograms of terpanes (a), contour map of the thickness and Ro (b), and the core photo (c) of the source rock in K1b2 in the Hari Sag, which is also the photo of the sample in our study.

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Samples

The samples in our study were collected from well H2 in the Hari Sag of the Suhongtu Depression; it developed in K1b2. The depth of the sample is 1062 m, the lithology is dark gray lime mudstone, and the photo of one sample is shown in Figure 2c. The previous testing and analysis data of the sample were as follows: total organic carbon content (TOC) of the sample was 6.05%; the Rock-Eval parameters S1 + S2 value (hydrocarbon generation potential) and Tmax value were 14.34 mg/g and 436 °C, respectively; the chloroform bitumen “A” content was 0.3355%; the δ13CPDB value of the chloroform bitumen “A” was −28.4‰; the hydrogen index (HI) was 222 mgHC/gTOC; the H/C (hydrogen/carbon atomic ratio) and O/C (oxygen/carbon atomic ratio) of kerogen are 0.97 and 0.19, respectively; and the kerogen Ro is 0.56%. According to the Geochemical Evaluation Standard of Terrestrial Hydrocarbon Source Rock,42 the sample was a type II2 kerogen (Figure 3a,b) and a low-mature source rock with extremely high organic matter abundance.

Figure 3.

HI versus OI cross plot (a) and HI versus Tmax cross plot (b), showing the type of organic matter of the sample (HI represents the hydrogen index, OI represents the oxygen index, and Tmax represents the maximum peak temperature of the rock pyrolysis. Data shown in the figure include several other samples from the same formation, the red circle is the sample from the H2 well, and the black circles are samples from other wells. Organic matter type identification criteria are based elsewhere40).

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Closed-System Pyrolysis Simulation Experiments

Pyrolysis simulation experiments were carried out in a closed system, with the aim of obtaining the exact same type of source rock samples and absolutely homologous oil samples with different maturity levels. The experiments were completed by the Key Laboratory of Petroleum Geochemistry of Exploration and Development Research Institute of CNPC. The experimental process was based on a published method.43 In order to ensure a complete hydrocarbon generation reaction, the sample was crushed to less than 80 mesh and mixed evenly. The weight of each pulverized sample used at every temperature point was 200 mg. The sample was put into high-temperature and high-pressure reactors, and a certain amount of distilled water was added; the approximate ratio of sample to water was 5:1. Subsequently, the reactors were sealed and put into the heating furnace to carry out the hydrocarbon generation and expulsion thermal simulation experiments. Ten target temperatures were set: 250, 300, 350, 375, 400, 425, 450, 475, 500, and 550 °C. Each reactor was heated from room temperature to the target temperature at a heating rate of 5 °C/min, and the target temperature was maintained for 24 h. After the experiments, the hydrocarbon discharge valves were opened, and the liquid hydrocarbon products expelled from samples were collected and cooled with distilled water. After that, liquid hydrocarbon, in distilled water, was extracted with dichloromethane and recorded as expelled oil 1. After the reactors were cooled, they were opened and experimental solid residues were collected. The experimental solid residues, at different temperatures, represented the source rock samples with different maturity levels. Finally, the liquid hydrocarbon on the reactor’s inner wall, the pipeline, and the hydrocarbon discharge valve were cleaned and the contents were collected using dichloromethane and recorded as expelled oil 2. The total amount of the expelled oil was the sum of expelled oil 1 and expelled oil 2.

3.2.2. Soxhlet Extraction and Hydrocarbon Separation

Approximately 30–40 mg of each experimental solid residue sample was extracted in a Soxhlet apparatus for 72 h using a solvent mixture of dichloromethane and methanol (93:7 v:v). The extractable organic matter (EOM, also the name of the extracts) from each residue sample was obtained. If dichloromethane was used as a solvent for the extraction experiment, we designated the obtained EOM chloroform bitumen, A, in this study.

Separation operations were carried out on 10 expelled oils and 10 extracts using a packed silica gel and neutral alumina column. The saturated hydrocarbon fraction was eluted by n-hexane, the aromatic hydrocarbon fraction was eluted by a mixture of dichloromethane and n-hexane (2:1, v/v), and the polar (non-hydrocarbon and bitumen) fraction was eluted by methanol.

3.2.3. Vitrinite Reflectance Measurement

Kerogens were separated from 10 extracted residues using physical and chemical methods, and the kerogen samples were prepared. We then took a small amount of kerogen to make optical films—the method was to mix the kerogen with a consolidation agent for curing and molding, grind it with sandpaper, and polish it with polishing liquid. After drying, the optical films were placed under reflected light in a ZEISS Axio microscope prepared for Ro determinations. The Ro measurement system was a TIDAS PMT IV photometer and MSP200 testing software. The object of the tests was to obtain vitrinite in kerogens. In order to ensure the accuracy of the data, at least 30 measurements, in most cases, were carried out for each sample and the average value was taken as the vitrinite reflectance of the sample.

3.2.4. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Analysis

The aromatic hydrocarbon fractions of 10 oils and 10 extracts were analyzed by the GC–MS method using the specific experimental methods elsewhere.40 GC–MS analyses were performed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (GC) coupled with an Agilent 5977A mass spectrometer (MS) system. An Agilent HP-5 (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.5 μm) fused silica capillary column was used. The GC oven temperature was initially maintained at 50 °C for 2 min, then raised to 310 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min, and finally maintained for 18 min. The carrier gas was helium, and the constant current mode was adopted with a 1 mL/min flow rate. The scanning mode of the mass spectrometer was set to full scan (Full Scan) and multi-ion detection (MID).

4. Results

4.1. Maturity

The measured Ro values of 10 experimental solid residues are listed in Table 1. When temperatures increased from 250 to 550 °C, the values of Ro ranged from 0.62 to 2.39%. Therefore, a thermal evolution sequence of source rocks from low-mature to over-mature was established. The quantitative characterization to their maturity was not possible for the oils, but the oil should have had a similar thermal evolution degree to its source rock at the same temperature. In this study, the Ro values of experimental solid residues were used to quantitatively characterize the maturity of the corresponding discharged oils.

Table 1. Ro Data of Residual Samples.

|

Ro (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | temperature (°C) | maximum | minimum | average | number of samples measured |

| 1 | 250 | 0.659 | 0.501 | 0.60 | 31 |

| 2 | 300 | 0.664 | 0.514 | 0.61 | 31 |

| 3 | 350 | 0.895 | 0.562 | 0.75 | 36 |

| 4 | 375 | 1.086 | 0.732 | 0.84 | 39 |

| 5 | 400 | 1.321 | 1.022 | 1.12 | 39 |

| 6 | 425 | 1.627 | 1.262 | 1.45 | 35 |

| 7 | 450 | 1.941 | 1.624 | 1.79 | 30 |

| 8 | 475 | 2.095 | 1.629 | 1.83 | 39 |

| 9 | 500 | 2.362 | 1.767 | 2.06 | 30 |

| 10 | 550 | 2.661 | 2.193 | 2.39 | 35 |

4.2. Content of EOM

Figure 4 shows the relationship between Ro and chloroform bitumen “A” contents. When the values of Ro of the source rocks increased from 0.62 to 2.39%, the content of chloroform bitumen “A” decreased from 0.2382 to 0.0290%. The results showed a gradually decreasing EOM content in the source rocks with increasing maturity, and the relationship between them presented a power function. The decrease in EOM may have been due to hydrocarbon expulsion. As observed in the whole process of the thermal simulation experiments, the hydrocarbon generation rates of the source rocks continued to increase. An inverse relationship was observed between the increasing trend of hydrocarbon generation rates and the decreasing trend of chloroform bitumen “A” contents, indicating a certain internal relationship between them. Most likely, with increased maturity, more EOM was converted into hydrocarbons and expelled from the source rock. At the same time, the increase in hydrocarbon generation rates was significantly greater than the decrease in chloroform bitumen “A” contents. Hydrocarbons were not only generated from EOM, but kerogen also contributed to hydrocarbon generation, to a degree.

Figure 4.

Chloroform bitumen “A” content and hydrocarbon generation rate versus Ro plot, showing variations in EOM and hydrocarbon generation during thermal evolution.

4.3. Relative Abundance of Aromatic Hydrocarbons

As shown in Figure 5, with the increase in the thermal evolution degree, the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the group composition of source rocks and oils showed different evolutionary characteristics. The relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in source rocks showed a characteristic designated as ″increased early, unchanged middle, decreased lately″. Essentially, abundance increased with increasing maturity in the early stage (Ro < 0.80%), did not significant change in the middle stage (Ro = 0.80–2.00%), and decreased slightly in the late stage (Ro > 2.00%). Increases in the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the early stage could have been due to the polycondensation of aromatic hydrocarbons.44 Furthermore, the decrease in the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the later stage could have been due to the condensation of aromatics, because in the process of condensation, some small molecular compounds will be lost, resulting in the reduction in the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons. Wei et al.45 suggested that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons might be condensed into compounds with larger groups and finally into coke at high temperatures. However, the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the group composition of the oils changed relatively simply (Figure 5b) because the relative abundance of aromatics continuously increased with the increase in maturity.

Figure 5.

Group composition contents versus the Ro plot showing changes in the relative abundance of aromatic hydrocarbons in the group composition of the extracts (a) and discharged oils (b).

4.4. Bulk Composition of the Aromatic Hydrocarbons

There were as many as 109 kinds of aromatic compounds detected in the extracts and oils. These compounds were divided into 14 series, namely, naphthalenes, biphenyls, dibenzofurans, fluorenes, phenanthrenes, dibenzothiophenes, fluoranthenes, benzofluorene, pyrenes, benzofluoranthenes, benzoanthracene, chrysenes, benzopyrenes, and perylene. The peak areas of each series were calculated, and the areas of each series were normalized. This was used to determine the relative abundance of each series in aromatic compounds, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance variation of the aromatic homologs in extracts of solid residue (a) and oils (b) during thermal evolution (Tem.: temperature, A: naphthalenes (including naphthalene, methylnaphthalenes, ethylnaphthalenes, dimethylnaphthalenes, trimethylnaphthalenes, and tetramethylnaphthalenes), B: biphenyls (including biphenyl and methylbiphenyls), C: dibenzofurans (including dibenzofuran, methyldibenzofurans, and dimethyldibenzofurans), D: fluorenes (including fluorene and methylfluorenes and dimethylfluorenes), E: phenanthrenes (including phenanthrene, methylphenanthrenes, ethylphenanthrenes, and dimethylphenanthrenes), F: dibenzothiophenes (including dibenzothiophene, methyldibenzothiophenes, ethyldibenzothiophene, and dimethyldibenzothiophenes), G: fluoranthenes (including fluoranthene and methylfluoranthenes), H: benzofluorenes (including benzo[a]fluorene and benzo[b]fluorene), I: pyrenes (including pyrene and methylpyrenes), J: benzofluoranthenes (benzo[ghi]fluoranthene and benzo[b]fluoranthene), K: benzoanthracene (benzo[a]anthracene), L: chrysenes (including chrysene and methylchrysenes), M: benzopyrenes (benzo[e]pyrene and benzo[b]pyrene), N: perylene (including only perylene)).

We observed that phenanthrenes accounted for the largest proportion of aromatic hydrocarbons; the maximum relative abundances of phenanthrenes in aromatic hydrocarbons were as high as 71.66 and 63.03% in extracts and oils, respectively. Phenanthrenes were followed by fluoranthenes, pyrenes, and chrysenes, with maximum relative abundances of 13.79, 26.46, and 15.32%, respectively, in the aromatic hydrocarbons of the extracts, and 14.52, 22.87, and 8.63%, respectively, in oils. The relative abundance of naphthalenes in the extracts was significantly higher than that in the oils; the former was 0.08–2.65%, while the latter was 0.10–20.21%. This was the largest observed difference in bulk composition of aromatic hydrocarbons between the extracts and the oils. This phenomenon could have been due to fractionation; in comparison with other aromatic compounds, low-molecular-weight aromatic hydrocarbons such as naphthalenes were more easily discharged in the process of hydrocarbon generation and expulsion, resulting in the relative abundance of naphthalenes in the oils as compared to extracts.

As shown in Figure 6, the relative abundance of each aromatic series showed a similar variation characteristic during the process of thermal evolution, both in extracts and the oils. With increases in maturity, phenanthrenes, naphthalenes, and dibenzothiophenes exhibited gradual decreases in relative abundance. Fluorenes, fluoranthenes, benzofluorenes, pyrenes, benzofluoranthenes, benzoanthracene, chrysenes, and benzopyrenes exhibited continuously increasing relative abundances. Biphenyls, dibenzofurans, and perylene exhibited lower relative abundances and little variation.

Some scholars have contended that maturity has a great influence on the bulk composition of the aromatic hydrocarbons.6,46 As for oils/source rocks with lower maturity levels, the relative abundances of high-molecular-weight aromatic hydrocarbons, such as 4-ring and 5-ring aromatics, were higher. However, if the oils/source rocks exhibited higher maturity levels, the relative abundances of relatively low-molecular-weight aromatic hydrocarbons, such as 2-ring and 3-ring aromatic hydrocarbons, were dominant. However, the results in our study showed that the relative abundances of the 1–3-ring aromatic hydrocarbons (such as dicyclic naphthalenes, tricyclic phenanthrenes, and dibenzothiophenes) decreased significantly with the increase in maturity. Meanwhile, the relative abundances of the 4+-ring aromatic hydrocarbons (such as tetracyclic benzopyrene, etc.) increased significantly with increases in maturity. These results were contrary to previous understandings, and so, it was suggested that the effect of maturity on the bulk composition of aromatic hydrocarbons might not be sufficiently obvious. Other factors, such as biological sources and the depositional environment, might exceed the control of maturity.

5. Discussion

Methylation, isomerization, and demethylation of aromatic compounds are mainly controlled by thermodynamics. Thus, with the increase in the thermal evolution degree, α-position substituents may migrate to the β-position because β-positions have a greater relative stability in thermodynamics. Consequently, the relative abundances of β-type isomers increase continuously, but the relative abundances of α-type isomers decrease continuously. The content ratios of β-type isomers to α-type isomers can be used as maturity parameters.4,14,46−48 Based on these principles, more than 20 kinds of maturity parameters related to aromatics have been established by previous researchers.4,8,9,13,49−56 Although these parameters exist in great numbers, they can be divided into alkylnaphthalenes, alkylphenanthrenes, alkyldibenzothiophenes, and methylchrysenes (Table 2). According to the principle of the parameters established, the values of these parameters should show a continuous upward trend with increases in the maturity.

Table 2. Summary Table of Aromatic Maturity Parameters Established by Previous Researchers.

| parameter category | abbreviation | m/z | calculation formula | references | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alkylnaphthalenes | methylnaphthalene (MN) | MNR | 142 | 2-MN/1-MN | (49)−51 |

| dimethylnaphthalene (DMN) | DNR-1 | 156 | (2,6-DMN + 2,7-DMN)/1,5-DMN | ||

| DNR-2 | 156 | 2,7-DMN/1,8-DMN | |||

| DNR-3 | 156 | 2,6-DMN/1,8-DMN | |||

| DNR-4 | 156 | 1,7-DMN/1,8-DMN | |||

| DNR-5 | 156 | 1,6-DMN/1,8-DMN | |||

| trimethylnaphthalene (TMN) | TMNr | 170 | 2,3,6-TMN/(1,4,6-TMN + 1,2,5-TMN) | (52)−54 | |

| TMNr1 | 170 | 2,3,6-TMN/(1,4,6-TMN + 1,3,5-TMN) | |||

| TMNr2 | 170 | (2,3,6-TMN + 1,3,7-TMN)/(1,4,6-TMN + 1,3,5-TMN + 1,3,6-TMN) | |||

| TMNr3 | 170 | 1,3,7-TMN/(1,3,7-TMN + 1,2,5-TMN) | |||

| tetramethylnaphthalene (TeMN) | TeMNr | 184 | 1,3,6,7-TeMN/(1,3,6,7-TeMN + 1,2,5,7-TeMN) | ||

| pentamethylnaphthalene (PMN) | PMNr | 198 | 1,2,4,6,7-PMN/(1,2,4,6,7-PMN + 1,2,3,5,6-PMN) | ||

| alkylphenanthrenes | methylphenanthrene (MP) | MPI1 | 192 | 1.5 × (2-MP + 3-MP)/(P + 1-MP + 9-MP) | (8) |

| MPI2 | 192 | 3 × (2-MP)/(P + 1-MP + 9-MP) | |||

| MPI3 | 192 | (2-MP + 3-MP)/(1-MP + 9-MP) | |||

| MPR | 192 | (2-MP)/(1-MP) | (9) | ||

| F1 | 192 | (3-MP + 2-MP)/(1-MP + 2-MP + 3-MP + 9-MP) | |||

| F2 | 192 | 2-MP/(1-MP + 2-MP + 3-MP + 9-MP) | |||

| dimethylphenanthrene | DPR | 206 | (2,6-MP + 2,7-MP)/(1,6-MP + 2,10-MP) | ||

| DPR2 | 206 | 2,7-MP/1,8-MP | |||

| alkyldibenzothiophenes | methyldibenzothiophene (MDBT) | MDR | 198 | 4-MDBT/1-MDBT | (55) |

| MDBI | 198 | 4-MDBT/DBT + 1-MDBT + 2-MDBT + 3-MDBT + 4-MDBT | (56) | ||

| dimethyldibenzothiophene (DMDBT) | DMDBT1 | 212 | 4,6-DMDBT/1,4-DMDBT | (13),55 | |

| DMDBT2 | 212 | 2,4-DMDBT/1,4-DMDBT | |||

| DMDBT3 | 212 | 2,6-DMDBT/1,4-DMDBT | |||

| DMDBT4 | 212 | 4,6- DMDBT/(1,4- DMDBT + 1,6-DMDBT) | |||

| DMDBT5 | 212 | (2,6-DMDBT + 3,6-DMDBT)/(1,4-DMDBT + 1,6-DMDBT) | |||

Based on test analysis data, 16 aromatic maturity parameters were calculated. Other parameters could not be calculated because the related compounds were not detected or because certain compounds were quantified integrally. The correlation between these parameters and Ro was analyzed, and the validity of these parameters for lacustrine source rocks/oils was discussed.

5.1. Validity of Alkylnaphthalene-Related Maturity Parameters

Naphthalenes are compounds fused by two benzene rings sharing two carbon atoms (Figure 7a). In naphthalenes, the steric hindrance effect of the α-position is relatively larger, so the thermal stability levels of α-position methylnaphthalenes are relatively poor. Their thermal stability may decrease with the increase in maturity. However, the steric hindrance effect of the β-position is relatively smaller, and thus, once β-type isomers are formed, they have good relative thermal stability.47,57,58 Therefore, the content ratio of the β-type isomers (with better thermal stability) to α-type isomers (with poor thermal stability) can be used as a maturity parameter and can reflect maturity changes in sedimentary organic matter.3,11,59 These parameters include methylnaphthalene-related parameters, dimethylnaphthalene-related parameters, trimethylnaphthalene-related parameters, tetramethylnaphthalene-related parameters, and pentamethylnaphthalene-related parameters (Table 2).

Figure 7.

Parent structures of common aromatic hydrocarbons: (a) naphthalene, (b) phenanthrene, (c) dibenzothiophene, and (d) chrysene.

It was observed from the chromatograms of naphthalenes that the compound categories of 10 extracts and 10 oils were the same and the peak types were quite similar (Figure 8). This indicated that the results of the GC–MS analyses were reliable, and the data could be used for applicability studies of aromatic maturity parameters in lacustrine source rocks or oils. At the same time—except for the early stage (e.g., extract 1–extract 3 and oil 1–oil 3) and late stage (e.g., residue sample extract 10 and discharged oil 10) of the pyrolysis simulation experiments—the relative abundance of naphthalene compounds at other temperature points presented regular changes with increased degrees of thermal evolution. This indicated that the maturity parameters of alkylnaphthalenes were not applicable at all to maturity but had a certain scope of application.

Figure 8.

Chromatograms of naphthalenes in the extracts of solid residue and discharged oils (sample information is the same as that shown in Figure 6).

Five alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters (MNR, DNR-1, TMNr1, TMNr2, and TMNr3) were calculated in this study. Additionally, their correlations with Ro were analyzed, which could directly reflect the application effectiveness of these parameters (Figure 9a–e). The results showed that, in the early stage of thermal evolution (Ro < 0.84%), whether for lacustrine source rocks or for oils, these parameters had a negative correlation with Ro, did not change significantly, or fluctuated slightly. This indicated that these parameters were not applicable to lacustrine source rocks/oils at this stage. This phenomenon was also reported in the research of Chen et al. and Wang et al.11,27 Meanwhile, at the mature to highly mature stage (Ro = 0.84–2.06%), these parameters had a good positive correlation with Ro, indicating that these parameters were valid at this stage. However, at the over-mature stage (Ro > 2.06%), most parameters, e.g., MNR, DNR-1, TMNr1, and TMNr2, decreased rapidly with the increase in Ro, indicating that it had no correlation to maturity. Wang et al.27 pointed out that isomerization, methylation, and demethylation played an important role in the distribution of alkylnaphthalenes in source rocks and that isomerization and methylation played a dominant role at a relatively low thermal maturity stage while demethylation played a leading role at a relative high maturity. However, alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters were mainly based on the principle of isomerization and methyl rearrangement. When a higher maturity level was presented, demethylation dominated the concentration of naphthalenes, invalidating some parameters in this case. The conclusion that alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters were not applicable at the over-mature stage was reported in previous studies, such as Wang et al.,3 who suggested that the upper limit of the effective application of some alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters was 2.00% Ro.

Figure 9.

Parameters versus Ro plots showing the validity of the aromatic hydrocarbon-related maturity parameters: (a) MNR versus Ro, (b) DNR-1 versus Ro, (c) TMNr1 versus Ro, (d) TMNr2 versus Ro, (e) TMNr3 versus Ro, (f) MPI1 versus Ro, (g) MPI2 versus Ro, (h) MPI3 versus Ro, (i) MPR versus Ro, (j) F1 versus Ro, (k) F2 versus Ro, (l) DPR2 versus Ro, (m) MDR versus Ro, (n) DMDBT4 versus Ro, (o) DMDBT5 versus Ro, and (p) MCH1 versus Ro.

Specifically, the parameter TMNr3 showed a continuous positive correlation with Ro even at the over-mature stage. This showed that this parameter had a wider application range than other parameters and was still applicable at the over-mature stage to lacustrine source rocks or oils.

5.2. Validity of Alkylphenanthrene-Related Maturity Parameters

The same isomerization also exists in the alkylphenanthrenes. It makes the α-position substituents migrate to the β-position in the process of thermal evolution, considering that the β-position is relatively more thermodynamically stable than the α-position (Figure 7b). Therefore, the content ratio of the β-type isomers to α-type isomers can be used as a maturity parameter.3,4,8,9,60 These parameters mainly include the methylphenanthrene-related parameters and dimethylphenanthrene-related parameters (Table 2). These parameters have been widely used in maturity evaluations of source rocks or oils, but disputes still persist as to their applicable range.61

It was also observed from chromatograms of phenanthrenes that the compound categories in 10 extracts of residual samples and 10 oils were the same—and that the peak types were also very alike (Figure 10). This confirmed that the GC–MS analysis results of phenanthrenes were reliable. Meanwhile, in addition to the late stage of thermal simulation experiments (e.g., extract 10 and oil 10), the relative content of phenanthrene compounds at other temperature points showed regular changes, indicating that the maturity parameters of alkylphenanthrenes had better application effects. However, a certain scope of application must also be considered.

Figure 10.

Chromatograms of phenanthrenes in the extracts of solid residue and discharged oils (sample information is the same as that shown in Figure 6).

Based on observations of the correlation between the seven calculated alkylphenanthrene-related maturity parameters (MPI1, MPI2, MPI3 MPR, F1, F2, and DPR2) and Ro (Figure 9f–l), these parameters seemed to have a wider range of application, suggesting that the alkylphenanthrene-related parameters have a useful application to lacustrine source rocks/oils. When the Ro values were equal to 0.60–2.06%, the parameters MPI1, MPI2, MPI3, MPR, F1, and F2 had a continuous positive correlation with Ro and showed good applicability. This conclusion was also consistent with previous understandings. For example, Wang et al.3 believed that using parameters such as MPI1, MPI2, MPI3, MPR, F1, F2, and MPR could effectively evaluate the maturity of organic matter when the Ro values ranged from 0.65 to 2.00%. Chen et al.62 believed that there was a good positive correlation between methylphenanthrene-related parameters and maturity when the Ro values ranged from 0.50 to 1.80%. However, the values of the parameter DPR2 did not change significantly when the Ro values were 0.60–0.84% and only showed a positive correlation with Ro when the Ro values were equal to 0.84–2.06%, indicating that the applicable range of this parameter might be narrower. In fact, this parameter only demonstrated good applicability during the mature–high-mature stage (Ro = 0.84–2.06%). At the over-mature stage (Ro > 2.06%), all the alkylphenanthrene-related parameters decreased rapidly with the increase in Ro, demonstrating that it was not effective in maturity evaluation. It could be similar to alkylnaphthalenes, as the distribution of compounds was also dominated by demethylation in the over-mature stage,27 resulting in the invalidity of some parameters.

5.3. Validity of Alkyldibenzothiophene-Related Maturity Parameters

Due to their stronger thermal stability and high resistance to biodegradation, alkyldibenzothiophenes are more advantageous in maturity evaluations.11,52,63 The molecular structures of alkyldibenzothiophenes are symmetric (Figure 7c), and the content ratios of some methyldibenzothiophene, dimethyldibenzothiophene, and trimethyldibenzothiophene isomers can be used as maturity parameters because of the great differences in their thermal stability during thermal evolution.13,14,55,56 Wang et al.64 believed that the alkyldibenzothiophene-related maturity parameters had a wide range of applications and could be applied to oils in different maturity stages, especially as applied to high-mature and over-mature oils that lacked effective molecular parameters. However, Zhou et al.14 believed that some alkyldibenzothiophene-related parameters were greatly affected by sedimentary environments at the low–medium maturity stages and had no indicative significance on maturity. Wu et al.65 thought that the parameter MDR (4-/1-methyldibenzothiophene) should be used within an appropriate maturity level and be considered in combination with actual geological conditions. Their reasoning for this rested upon the fact that this parameter, generally speaking, first increased with increases in maturity and then decreased. The turning point appeared at 1.49% Ro.

The alkyldibenzothiophenes detected from the 10 extracts and 10 oils fell into the same category and had quite similar peak types, revealing that the GC–MS data were also reliable (Figure 11). At the same time, except for the early stage (e.g., extract 1–extract 3 and oil 1–oil 3) and late stage (e.g., extract 10 and oil 10) of thermal simulation, the relative abundance of alkyldibenzothiophenes at other temperature points showed regular changes with increases in maturity. This indicated that the maturity parameters of alkyldibenzothiophenes were not applicable to the whole evolution process but had a certain scope of application.

Figure 11.

Chromatograms of dibenzothiophenes and chrysenes in the extracts of solid residue and oils (sample information is the same as that shown in Figure 6).

Based on the test analysis data, the alkyldibenzothiophene-related maturity parameters MDR, DMDBT4, and DMDBT5 were calculated (Figure 9m–o). These parameters also demonstrated good positive correlation at the mature to high-mature stage (Ro = 0.84–2.06%), indicating good applicability at this stage. However, these parameters had a negative correlation with Ro at the low-mature to early-mature stage (Ro < 0.84%), showing that the parameters were not applicable at this stage. At the same time, these parameters decreased rapidly with the increase in Ro at the over-mature stage (Ro > 2.06%), revealing that they were not indicative of maturity.

This study further verified that the alkyldibenzothiophene-related maturity parameters could not effectively be used at the low-mature and high-mature stages. It was only at the mature to over-mature stage (Ro = 0.84–2.06%) that these parameters became effective. Chen et al.11 considered that the effective application range of the dimethyldibenzothiophene-related parameters of lacustrine source rocks was Ro = 0.50–2.35%. Thus, the results in this study were close to previous findings. Comparatively, the effective range of application, as determined herein, was more representative than previous findings. This may be attributable to the fact that the samples in the preceding research were source rocks from different strata of a certain area, applied as a whole.11 On the other hand, the samples obtained from thermal simulation experiments in this study were source rocks of wholly the same type and absolutely homologous oil samples.

5.4. Validity of Alkylchrysene-Related Maturity Parameters

The degree of research applicability of alkylchrysene-related maturity parameters was relatively low; the most commonly used parameters were solely based on methylchrysene (MCH). There were four isomers of methylchrysenes, namely, 1-MCH, 2-MCH, 3-MCH, and 4-MCH. Similarly, according to differences in molecular thermal stability (Figure 7d), the parameter MCH1 (3-MCH/1-MCH) was established. It was believed that the four isomers of methylchrysene underwent isomerization with increases in thermal evolution, and 3-MCH/1-MCH was more sensitive to the maturity of organic matter. Thus, it exhibited an increasing trend along with increasing maturity.4,66 This study showed that the value of MCH1 first increased and then decreased as maturity increased. The value reached a maximum when the Ro value was equal to 1.79% (Figures 9p and 11). The findings indicated that the effective application range of the methylnaphthalene maturity parameter MCH1 was an Ro value below 1.79%.

6. Conclusions

Based on pyrolysis simulation experiments, the application effectiveness of the aromatic maturity parameters of source rocks and oils was discussed. The following conclusions are drawn.

-

(1)

With increases in the degree of thermal evolution, the relative abundances of aromatic hydrocarbons in extracts of source rocks showed characteristics expressed as ″increased early, unchanged middle, decreased lately″, while the relative abundances of aromatic hydrocarbons in oils continuously increased.

-

(2)

With increased maturity, the relative abundances of 1–3-ring aromatic hydrocarbons continuously decreased, as observed in the phenanthrene homologs. Meanwhile, the relative abundances of 4+-ring aromatic hydrocarbons continuously increased, as seen in chrysene homologs. These results showed that the influence of maturity on the macrocomposition of aromatic hydrocarbons may not have been sufficiently obvious.

-

(3)

The effective application range of the alkylnaphthalene-related maturity parameters MNR, DNR-1, TMNr1, and TMNr2, and the alkyldibenzothiophene-related maturity parameters MDR, DMDBT4, and DMDBT5, was 0.84–2.06% Ro. The alkylphenanthrene-related maturity parameters MPI1, MPI2, MPI3, MPR, F1, F2, and DPR2 demonstrated a wide application range and a strong effect upon lacustrine source rocks and oils. Except for the over-mature stage, all these parameters could be effectively used at other thermal evolution stages (Ro < 2.06%). In addition, the effective application range of the methylnaphthalene-related maturity parameter MCH1 was at Ro less than 1.79%.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42272160, 41872144) and the Yanchang Petroleum Group Co., Ltd. Innovation Fund (ycsy2020jcxjB-03). The authors also appreciate the Yanchang Petroleum Group Co., Ltd. for providing access to core samples.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Hakimi M. H.; Lotfy N. M.; El Nady M. M.; Makled W. A.; Ramadan F. S.; Rahim A.; Qadri S. M. T.; Lashin A.; Radwan A. E.; Mousa D. A. Characterization of Lower Cretaceous organic-rich shales from the Kom Ombo Basin, Egypt: Implications for conventional oil generation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 241, 105459 10.1016/j.jseaes.2022.105459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siyar S. M.; Zafar M.; Jahandad S.; Khan T.; Ali F.; Ahmad S.; Fnais M. S.; Abdelrahman K.; Ansari M. J. Hydrocarbon generation potential of Chichali Formation, Kohat Basin, Pakistan: A case study. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. 2021, 33, 101235 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.101235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. J.; Zhang H.; Li S. Y.; Wen L. Maturity parameters selection and applicable range analysis of organic matter based on molecular markers. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2018, 37, 202–211. 10.19509/j.cnki.dzkq.2018.0427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Guo X. W.; He S. Analysis on validity of maturity parameters of biomarkers: a case study from source rocks in Yitong Basin. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ., Nat. Sci. Ed. 2016, 31, 23–31. 10.3969/j.issn.16734)64X.2016.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. J. Application of the vitrinite-like maceral reflectance measuring method for the marine hydrocarbon source rocks in east Tarim. Pet.Geol. Oilf. Dev. Daqing 2016, 35, 33–36. 10.3969/J.ISSN.10003754.2016.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T.; Hou D. J.; Cao B.; Chen X. D.; Diao H. Characteristics of Aromatic geochemistry in light oils from Xihu sag in East China Sea basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2017, 35, 182–191. 10.14027/j.cnki.cjxb.2017.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H. Y.; Zhao J.; Liu H. S.; Zhong G. J.; Ma W. Y.; Xue P.; Lu W. K.; Chen D. Y. Prediction of oil and gas reservoir traps by aromatic hydrocarbons from seabed sediments in Chaoshan depression. South China Sea. Acta Pet. Sin. 2018, 39, 528–540. 10.7623/syxb201805004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Welte D. H.; Willsch H. Geochemical study on a well in the Western Canada Basin: relation of the aromatic distribution patter to maturity of organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1982, 46, 1–10. 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90285-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kvalheim O. M.; Christy A. A.; Telnaes N.; Bjørseth A. Maturity determination of organic matter in coals using the melhylphenanthrene distribution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1987, 51, 1883–1888. 10.1016/0016-7037(87)90179-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grotheer H.; Robert A. M.; Greenwood P. F.; Grice K. Stability and hydrogenation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during hydropyrolysis (HyPy) – Relevance for high maturity organic matter. Org. Geochem. 2015, 86, 45–54. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. J.; Zhang J. Q.; Niu L. Y.; Gao Y. W.; Zhao C. C.; Wang X. D. Applicability of aromatic parameters in maturity evaluation of lacustrine source rocks: a case study of Mesozoic source rocks in Yingenr Ejinaqi Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2020, 41, 928–939. 10.7623/syxb202008003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. N.; Zhang Z. N.; Wu Y. D.; Su L.; Xia Y. Q.; Wang Z. x.; Zheng Y. W. Evolution patterns and their significances of biomarker maturity parameters-a case study on liquid hydrocarbons from type II source rock under HTHP hydrous pyrolysis. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ., Nat. Sci. Ed. 2015, 36, 573–580. 10.11743/ogg20150406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakhmakhchev A.; Suzuki M.; Takayama K. Distribution of alkylated dibenzothiophenes in petroleum as a tool for maturity assessments. Org. Geochem. 1997, 26, 483–489. 10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00022-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. J.; Guan P.; Wu Y. X.; Liu P. X.; Ding X. N.; Tan Y.; Pang L. Characterization on the composition of dibenzothiophene series in saline lacustrine sediments in western Qaidam basin and its environmental implications. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2018, 29, 908–920. 10.11764/j.issn.1672-1926.2018.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. F.; Wang Y. C.; Cao J. Cretaceous source rocks and associated oil and gas resources in the world and China: A review. Pet. Sci. 2014, 11, 331–345. 10.1007/s12182-014-0348-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Chang X. C.; Sun Y. Z.; Shi B. B.; Qin S. J. Investigation of fluid inclusion and oil geochemistry to delineate the charging history of Upper Triassic Chang 6, Chang 8, and Chang 9 tight oil reservoirs, Southeastern Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 113, 104–115. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. J.; Liu Z. J.; Bechtel A.; Sachsenhofer R. F.; Jia J. L.; Meng Q. T.; Sun P. C. Organic matter accumulation in the upper cretaceous qingshankou and nenjiang formations, Songliao basin (NE China): implications from high-resolution geochemical analysis. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 102, 187–201. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhang J. L.; Liu Y.; Shen W. L.; Chang X. C.; Sun Z. Q.; Xu G. C. Organic geochemistry, distribution and hydrocarbon potential of source rocks in the paleocene, lishui sag, east China sea shelf basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 107, 382–396. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi K.; Ren Z. L.; Chen Z. P.; Cui J. P. Characteristics and controlling factors of lacustrine source rocks in the Lower Cretaceous, Suhongtu depression, Yin-E basin, Northern China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 127, 104943 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.104943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N. B.; Freeman K. H.; Pancost R. D.; White T. S.; Mitchell G. D. The character and origin of lacustrine source rocks in the Lower Cretaceous synrift section, Congo basin, west Africa. AAPG Bull. 2004, 88, 1163–1184. 10.1306/02260403069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Justwan H.; Dahl B.; Isaksen G. H. Geochemical characterization and geneticorigin of oils and condensates in the South Viking Graben, Norway. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2006, 23, 213–239. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2005.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keym M.; Dieckmann V.; Horsfield B.; Erdmann M.; Galimberti R.; Kua L. C.; Leith L.; Podlaha O. Source rock heterogeneity of the upper Jurassic Draupne formation, north Viking Graben, and its relevance to petroleum generation studies. Org. Geochem. 2006, 37, 220–243. 10.1016/s0140-6701(06)81537-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X.-H.; Pang X.-Q.; Li M.-W.; Li Z.-M.; Zhao L. Hydrocarbon generation from lacustrine shales with retained oil during thermal maturation. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 1478–1490. 10.1007/s12182-020-00487-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. J.; Jin Q. Hydrocarbon generation from Carboniferous-Permian coaly source rocks in the Huanghua depression under different geological processes. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 1540–1555. 10.1007/s12182-020-00513-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Xiao X.; Cheng P.; Wang M.; Tian H. The relationship between oil generation, expulsion and retention of lacustrine shales: Based on pyrolysis simulation experiments. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107625 10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He M.; Wang Z. Y.; Moldowan M. J.; Peters K. Insights into catalytic effects of clay minerals on hydrocarbon composition of generated liquid products during oil cracking from laboratory pyrolysis experiments. Org. Geochem. 2022, 163, 104331 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2021.104331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Huang H.; He C.; Li Z.; Zheng L. Methylation and demethylation of naphthalene homologs in highly thermal mature sediments. Org. Geochem. 2022, 163, 104343 10.1016/J.ORGGEOCHEM.2021.104343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. X.; Huang H. P. Bulk and molecular composition variations of gold-tube pyrolysates from severely biodegraded Athabasca bitumen. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 1527–1539. 10.1007/s12182-020-00484-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Liao Y.; Shi Q.; Hsu C. S.; Jiang B.; Peng P. Origin of polar organic sulfur compounds in immature crude oils revealed by ESI FT-ICR MS. Org. Geochem. 2018, 121, 36. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E.; Hackley P. C.; Thomas J. J.; Pomerantz A. E. Suppression of vitrinite reflectance by bitumen generated from liptinite during hydrous pyrolysis of artificial source rock. Org. Geochem. 2018, 125, 220. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y.; Wu Y.; Zhao Y.; Cao X.; Ma L. Hydrogen isotopic characteristic of hydrocarbon gas pyrolyzed by herbaceous swamp peat in hydrous and anhydrous thermal simulation experiments. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2018, 3, 67–72. 10.1016/j.jnggs.2018.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Liu Z.; Guo W.; Chen H. Characteristics and comprehensive utilization potential of oil shale of the Yin’e basin, Inner Mongolia, China. Oil Shale 2015, 32, 293–312. 10.3176/oil.2015.4.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z.; Liu G.; Cao Z.; Guo D.; Wang P.; Tang G. Geochemical characteristics, depositional environment, and controlling factors of Lower Cretaceous shales in Chagan Sag, Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin. Geol. J. 2018, 53, 1308. 10.1002/gj.2958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Liu R.; Liu Z.; Li L.; Wu X.; Zhao K. Influence of palaeoclimate and hydrothermal activity on organic matter accumulation in lacustrine black shales from the Lower Cretaceous Bayingebi Formation of the Yin’e Basin, China. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 2020, 560, 110007 10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y.; Wang H.; Fan T.; Zhang H.; Yang R.; Li Y.; Long S. Rift-related sedimentary evolution and its response to tectonics and climate changes: A case study of the Guaizihu sag, Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 195, 104370 10.1016/j.jseaes.2020.104370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Dai S.; Pan B.; Wang L.; Peng D.; Wang H.; Zhang X. The palynoflora of the Lower Cretaceous strata of the Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin in North China and their implications for the evolution of early angiosperms. Cretaceous Res. 2014, 48, 23–38. 10.1016/j.cretres.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Ren Z. L.; Xia B.; Zhao X. Y.; Tian T.; Huang Q. T.; Yu S. R. The Lower Cretaceous source rocks geochemical characteristics and thermal evolution history in the HaRi Sag Yin-E Basin. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 1304–1313. 10.1080/10916466.2017.1327969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J.; Yang X.; Wang L. Petroleum Systems of Chagan Depression, Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin Northwest China. J. China Univ. Geosci. 2005, 17, 55–64. 10.1016/S1002-0705(06)60007-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Huang Z.; Yin Y.; Guo H.; Zhang P. Sedimentology and geochemistry of Cretaceous source rocks from the Tiancao Sag, Yin’e Basin, North China: Implications for the enrichment mechanism of organic matters in small lacustrine rift basins. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 204, 104575 10.1016/j.jseaes.2020.104575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Gao Y.; Liu H.; He Y.; Ma F.; Meng J.; Zhao C.; Han C. Geochemical characteristics of Lower Cretaceous source rocks and oilsource correlation in Hari sag Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2018, 39, 69–81. 10.7623/syxb20180106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Ma F.; Xiao G.; Zhang Y.; Gao Y.; Wang X.; Han C. Oil-sources rock correlation of Bayingebi Formation in Hari sag Yingen-Ejinaqi Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2019, 40, 900–916. 10.11743/ogg20190418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SY/T 5735–1995. Geochemical evaluation standard of terrestrial hydrocarbon source rock.

- Liang M.; Wang Z.; Zhang J. Geochemical Characteristics of Steranes and Tepanes in Lacustrine Quality Source Rocks by Thermal Simulation Experiment. Bull. Miner. Rock Geochem. 2015, 34, 968–973. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-2802.2015.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. Y.; Liu W. H.; Chen J. F. Characteristics of liquid hydrocarbon in thermal pyrolysis experiment for coal of Tarim Basin, China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2004, 15, 355–359. 10.11764/j.issn.1672-1926.2004.04.355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C. Y.; Zhang B.; Hu G. Y.; Shuai Y. H.; Chen Y.; Zhang J.; Liu Y. E. Evolution characteristics and molecular analysis of molecular markers in pyrolysis from source rocks. Geochemistry 2021, 14, 602–611. 10.19700/j.0379-1726.2021.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Chen J.; Guo W. Geochemical characteristics of aromatic hydrocarbon in crude oil and source rocks from Nai 1 block of Naiman depression Kailu Basin. Geochimica 2013, 42, 262–273. 10.19700/j.0379-1726.2013.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P. Formation mechanism of alkylated naphthalene in petroleum hydrocarbon and its geochemistry significance. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2008, 27, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vuković N.; Životić D.; Mendonça Filho J. G.; Kravić-Stevović T.; Hámor-Vidó M.; de Oliveira Mendonça J.; Stojanović K. The assessment of maturation changes of humic coal organic matter - Insights from closed-system pyrolysis experiments. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 154-155, 213–239. 10.1016/j.coal.2016.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Willsch H.; Leythaeuser D.; Teichmüller M. Aromatic components of coal: relation of distribution pattern to rank. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1982, 46, 1831–1848. 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90122-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Leythaeuser D.; Teichmüller M. Relationship between rank and composition of aromatic hydrocarbons for coals of different origins. Org. Geochem. 1984, 6, 423–430. 10.1016/0146-6380(84)90065-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander R.; Kagi R. I.; Rowland S. J.; Sheppard P. N.; Chirila T. V. The effects of thermal maturity on distributions of dimethylnaphthalenes and trimethylnaphthalenes in some Ancient sediments and petroleums. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1985, 49, 385–395. 10.1016/0016-7037(85)90031-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Welte D. H.; Willsch H. Maturity parameters based on aromatic hydrocarbons: Influence of the organic matter type. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 51–63. 10.1016/0146-6380(86)90008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Aarssen B. G. K.; Bastow T. P.; Alexander R.; Kagi R. I. Distributions of methylated naphthalenes in crude oils: indicators of maturity, biodegradation and mixing. Org. Geochem. 1999, 30, 1213–1227. 10.1016/S0146-6380(99)00097-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M. Application of aromatic compounds as maturity indicators in source rocks and crude oils. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1988, 5, 224–236. 10.1016/0264-8172(88)90003-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Wang T.-G.; Shi S.; Zhu L.; Fang R. Oil maturity assessment using maturity indicators based on methylated dibenzothiophenes. Pet. Sci. 2014, 11, 234–246. 10.1007/s12182-0140336-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z.; Zhang D.; Zhang C.; Chen J. Methyldibenzothiophenes distribution index as a tool for maturity assessments of source rocks. Geochimica 2001, 30, 242–247. 10.19700/j.0379-1726.2001.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. F.; Zhang M.. Oil and gas geochemical; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing; 2018. p. 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina K.; Suzuki N. Methylated naphthalenes as indicators for evaluating the source and source rock lithology of degraded oils. Org. Geochem. 2018, 124, 46–62. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Huang H.; Zheng L. Thermal maturity parameters derived from tetra-, penta-substituted naphthalenes and organosulfur compounds in highly mature sediments. Fuel 2021, 288, 119626 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard R. E.; Polissar P. J.; Savage H. M. Organic thermal maturity as a proxy for frictional fault heating: Experimental constraints on methylphenanthrene kinetics at earthquake timescales. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 151, 103–116. 10.1016/j.gca.2014.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cassani F.; Gallango O.; Talukdar S.; Vallejos C.; Ehrmann U. Methylphenanthrene maturity index of marine source rock extracts and crude oils from the Maracaibo Basin. Org. Geochem. 1988, 13, 73–80. 10.1016/0146-6380(88)90027-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Bao J. P.; Liu Z. Q.; Wang L. Q.; Deng K.; Wang Y. P.; Qi W. Z.; Gao X. F.; Jin C. H. Relationship between methylphenanthrene index, methylphenanthrene ratio and organic thermal evolution: Take the northern margin of Qaidam Basin as an example. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2010, 37, 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Chakhmakhchev A.; Suzuki N. Saturate biomarkers and aromatic sulfur compounds in oils and condensates from different source rock lithologies of Kazakhstan Japan and Russia. Org. Geochem. 1995, 23, 289–299. 10.1016/0146-6380(95)00018-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; He F.; Li M.; Hou Y.; Guo S. Alkyl dibenzothiophenes: Molecular marker tracers for reservoir charging pathways. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2005, 176–182. 10.1007/BF03183429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Qi W.; Luo Q.; Chen Q.; Shi S.; Li M.; Zhong N. Experiments on the generation of dimethyldibenzothiophene and its geochemical implications. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2019, 41, 260–267. 10.11781/sysydz201902260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. W.; Wang T. G.; Li M. J.; Song D. F.; Shi S. B. The distribution of chrysene and methylchrysenes in oils from wells ZS5 and ZS1 in the Tazhong Uplift and its implications in oil-to-source correlation. Geochimica 2016, 45, 451–461. 10.19700/j.0379-1726.2016.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]