Abstract

Background

Given the increasing prevalence of wildfires worldwide, understanding the effects of wildfire air pollutants on human health—particularly in specific immunologic pathways—is crucial. Exposure to air pollutants is associated with cardiorespiratory disease; however, immune and epithelial barrier alterations require further investigation.

Objective

We sought to determine the impact of wildfire smoke exposure on the immune system and epithelial barriers by using proteomics and immune cell phenotyping.

Methods

A San Francisco Bay area cohort (n = 15; age 30 ± 10 years) provided blood samples before (October 2019 to March 2020; air quality index = 37) and during (August 2020; air quality index = 80) a major wildfire. Exposure samples were collected 11 days (range, 10-12 days) after continuous exposure to wildfire smoke. We determined alterations in 506 proteins, including zonulin family peptide (ZFP); immune cell phenotypes by cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF); and their interrelationship using a correlation matrix.

Results

Targeted proteomic analyses (n = 15) revealed a decrease of spondin-2 and an increase of granzymes A, B, and H, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1, IL-16, nibrin, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, C1q TNF-related protein, fibroblast growth factor 19, and von Willebrand factor after 11 days’ average continuous exposure to smoke from a large wildfire (P < .05). We also observed a large correlation cluster between immune regulation pathways (IL-16, granzymes A, B, and H, and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1), DNA repair [poly(ADP-ribose) 1, nibrin], and natural killer cells. We did not observe changes in ZFP levels suggesting a change in epithelial barriers. However, ZFP was associated with immune cell phenotypes (naive CD4+, TH2 cells).

Conclusion

We observed functional changes in critical immune cells and their proteins during wildfire smoke exposure. Future studies in larger cohorts or in firefighters exposed to wildfire smoke should further assess immune changes and intervention targets.

Key words: Wildfire exposure, air pollution, proteomics, immune cells, mass cytometry, zonulin, IL-16, granzyme, PARP-1

Introduction

Wildfires describe uncontrolled vegetation fires from forest, grassland, brushland, or combustible vegetation and can cause significant damage to the environment, infrastructure, and human life. With climate change, wildfire events are becoming more extreme in terms of burned area, duration, and intensity. Wildfires add significantly to air pollution and greenhouse gases, further exacerbating climate change and possibly leading to a reinforcing feedback loop.1 Extensive wildfires took place in Turkey, Greece, Russia, and California in 2021, and were linked to global warming and climate change.2 Also, in California, severe wildfires are becoming more commonplace. While studies of wildfire smoke and its health effects are limited compared to the literature on ambient air pollution, research has shown both short- and long-term negative health effects from wildfire smoke exposure.3

Wildfire smoke can contain carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, particulate matter (PM), complex hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, aldehydes, toxic metals such as Pb, Hg, and As, micro- and nano-scale plastics, trace minerals, and several other toxic, inflammatory, and carcinogenic compounds.4 The health impacts of wildfire smoke vary depending on the magnitude of the toxic pollution, the fuel source, the chemical makeup, and the combustion condition phases of the smoke. Fine and ultrafine particles are small enough to reach pulmonary alveoli and access the bloodstream, thus aggravating the respiratory, neurologic, and cardiovascular system symptoms and also affecting fetal growth.5 Wildfire smoke also has been shown to disrupt the skin epithelial barrier and may indirectly contribute to tissue inflammation in many chronic noncommunicable diseases, as proposed by the epithelial barrier hypothesis.6,7 The data are scarce, and metabolic and immune alterations after air pollution inhalation specific to wildfire smoke require further investigation.

A proposed mechanism suggests that many of the adverse health effects are mediated through immunologic changes induced by smoke. Previous investigations have shown that Toll-like receptors, reactive oxygen species, and aryl hydrocarbon receptors are activated in wildfire smoke exposure.8,9 We have previously evaluated immune changes in children aged 7 to 8 years after wildfire exposure and found lower levels of TH1 cells, which modulate immune responses, compared to children exposed to smoke from a prescribed burn.10 Moreover, a retrospective analysis of participants exposed to wildfire smoke showed that such exposure increased 2 key proinflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and IL-1β) compared to controls.11 Also, our group previously published data showing increases in immune biomarkers and DNA methylation of immunoregulatory genes during wildfire smoke exposure.12, 13, 14

In this study, we assessed the impact of wildfire smoke exposure on the immune system (determined by high-throughput proteomics and immune cell phenotyping) before and during exposure to wildfire smoke. Furthermore, we explored possible associations with epithelial barrier disruption by quantifying zonulin, which plays an important pathogenic role in a variety of diseases by regulating tight junctions,15 which have been correlated with inflammatory pathways.16

Zonulin constitutes a family of structurally related proteins called the zonulin family peptides (ZFPs).17 Zonulin can be secreted by the liver, intestine, lung, and several other tissues. It circulates in the blood and binds to receptors on epithelial cells.18 Most studies have been performed in the gut, but research is open to other epithelial barriers. Zonulin binds to its target, protease-activated receptor 2, and transactivates the epidermal growth factor receptor, which regulates epithelial barriers. The activation of these 2 receptors decreases transepithelial electrical resistance, thus suggesting increased barrier permeability.19 Abnormal zonulin secretion has been described in many diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, diabetes, and mental disorders.20 In addition, it has been reported that there is a potential link between high zonulin levels and coronavirus disease 2019 severity.21

The institutional review boards at Stanford University approved the protocol of this study (approval 51427). We conducted experiments on cryogenically stored plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from 15 participants collected before (October 2019 to March 2020; air quality index [AQI] = 37) and during (August 2020; AQI = 80) a major wildfire. Exposure samples were collected 11 days (range, 10-12 days) after continuous exposure to wildfire smoke from a large wildfire in the San Francisco Bay area (Table E1). We conducted plasma proteomic analyses, peripheral blood mononuclear cell CyTOF, and plasma zonulin family peptide (ZFP) measurements on each sample.

Results and discussion

Proteomic changes during wildfire smoke exposure

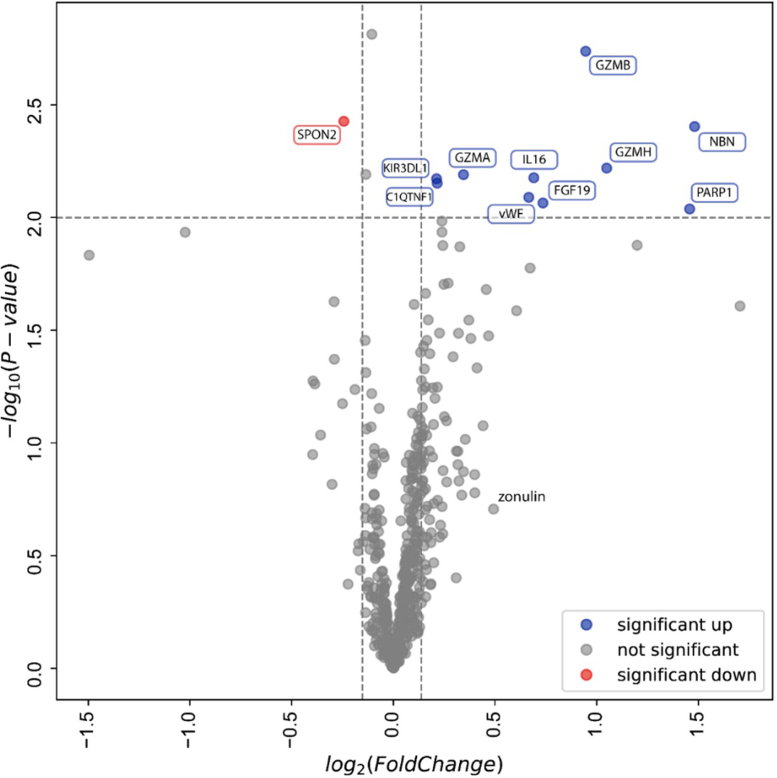

Targeted proteomic analyses by proximity extension assay considered the differential protein expression analysis across baseline versus during wildfire exposure (n = 15). Of 506 biomarkers, the results revealed a decrease of spondin-2 and increases in complement C1q TNF-related protein, fibroblast growth factor 19, granzymes A, B, and H, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, nibrin, poly(ADP-ribose) 1 (PARP-1), and von Willebrand factor during exposure (P < .05) (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Proteomic changes during wildfire exposure. Volcano plot of statistical significance (y-axis) against average fold changes in protein concentration (506 proteins) before and during wildfire exposure (x-axis). Horizontal dotted line represents threshold for statistically significant changes (defined as P < .01). Vertical dotted lines reflect cutoffs for fold changes; proteins at left side of left cutoff decreased by >10%, whereas proteins at right side of right cutoff increased by >10%. Red and blue dots show proteins that decreased or increased, respectively. C1QTNF1, Complement C1q TNF-related protein 1; FGF-19, fibroblast growth factor 19; GZMA/B/H, granzyme A/B/H; KIR3DL1, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1; NBN, nibrin; SPON2, spondin-2; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Mass cytometry by time of flight

When considering different immune cell phenotypes and subsets, our analysis showed that natural killer (NK) cells and regulatory T cells marginally increased during exposure (P = .078), as shown in Table I. We did not observe any significant changes in T cells, B cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, or type 2 innate lymphoid cells.

Table I.

CyTOF and ZFP data in 14 subjects before and during wildfire exposure

| Characteristic | Before exposure | After exposure | Fold change |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched pairs | Fold change | ||||

| T cells (CD3+) (%) | 52.5 (33.7-61.9) | 51.1 (41.8-58.9) | 0.98 (0.85-1.33) | .80 | .46 |

| CD4+ cells (%) | 32.4 (14.7-52.4) | 32.8 (18.5-0.52) | 0.98 (0.79-2.10) | .86 | .32 |

| TH1 cells (%) | 9.1 (4.4-15.8) | 9.1 (5.9-15.7) | 0.87 (0.63-2.50) | .62 | .52 |

| TH2 cells (%) | 1.0 (0.01-3.3) | 0.8 (0.05-3.7) | 1.22 (0.67-24.3) | .099 | .18 |

| Regulatory T cells (%) | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) | 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | 1.09 (0.66-2.77) | .15 | .078 |

| CD8+ cells (%) | 12.9 (5.6-20.6) | 12.7 (4.4-20.8) | 0.97 (0.79-1.74) | .91 | .59 |

| CD4−/CD8− cells (%) | 3.4 (1.5-8.6) | 3.3 (1.8-8.9) | 0.91 (0.56-1.39) | .91 | .68 |

| B cells (%) | 6.9 (2.8-9.1) | 6.0 (2.9-8.6) | 0.99 (0.69-1.83) | .78 | .62 |

| NK cells (%) | 10.8 (5.5-23.5) | 13.6 (5.9-23.2) | 1.11 (0.84-1.46) | .16 | .078 |

| ILC2s (%) | 0.17 (0.05-0.57) | 0.2 (0.04-0.9) | 1.07 (0.37-2.69) | .51 | .20 |

| Dendritic cells (%) | 0.3 (0.1-0.8) | 0.2 (0.1-0.6) | 1.11 (0.46-2.23) | .98 | .48 |

| Monocytes (%) | 13.9 (8.3-26.0) | 14.9 (11.3-20.0) | 1.07 (0.57-2.39) | .83 | .36 |

| ZFP (ng/mL) | 2.78 (0.25-4.96) | 3.62 (0.25-4.95) | 1.00 (0.52-12.5) | .41 | .18 |

Values are presented as medians (10th-90th percentiles). Sample size was 14 (1 subject was excluded from analysis because of lower total cell counts). ILC2, type 2 innate lymphoid cell.

Zonulin family peptide

Zonulin has been suggested to be a potential factor in human lung pathophysiology.22 Studies have suggested that it may be involved in the disassembly of tight junctions in the lungs in cases of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.23 In addition to increased lung permeability, increased intestinal permeability has also been implicated in other lung diseases like asthma.24,25 In this study, we measured levels of ZFP as a marker for intestinal permeability, and we found no significant increase during exposure (Table I). However, ZFP was correlated with immune cell phenotypes (naive CD4+ and TH2 cells). Some asthmatic patients have been found to have increased levels of serum zonulin, and about 40% have increased intestinal permeability.26 These findings suggest that both lung and intestinal mucosa may be routes through which specific antigens can access the immune system and lead to lung inflammation. Fig E3 (available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org) shows the correlation heat map between ZFP and proteins and Fig E4 (also in the Online Repository) for the correlation heat map between ZFP and immune cell types.

Effects of wildfire smoke

Overall, the difference in air quality due to wildfire smoke exposure was determined by AQI, as per the US Environmental Protection Agency guideline definition, shown in Fig E1 in the Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org. We found significant changes in protein expression and immune cell types associated with wildfire smoke exposure. This preliminary small-cohort study suggests that smoke exposure due to wildfire smoke air pollution may be associated with increases of multiple markers, potentially affecting both short- and long-term health.

The effects of smoke and air pollution on the immune system are thought to be mediated by oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and immune-mediated injury while releasing proinflammatory and vasoactive factors that could contribute to cardiorespiratory pathology.27, 28, 29 Our current findings show that wildfire exposure is associated with markers heavily involved in inflammatory processes as well as immune responses (with links to respiratory inflammation, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), DNA repair, and hemostasis (Table II).

Table II.

Pathways of proteins with significant change during wildfire exposure

| Change | Pathway | Protein | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins that increased | Hemostasis | C1QTNF1 | Suppresses platelet activation and aggregation; stimulates aldosterone secretion. |

| vWF | Maintains hemostasis; promotes adhesion of platelets to sites of vascular injury by forming molecular bridges between subendothelial collagen matrix and platelet–surface receptor complex. | ||

| Growth factor | FGF-19 | Suppresses bile acid biosynthesis; stimulates glucose uptake in adipocytes; member of heparin-binding growth factor family of proteins. | |

| Immune regulation | GZMA | Protease that mediates pyroptosis and targets cell death by cytotoxic T cells and NK cells. | |

| GZMB | Protease that mediates pyroptosis and targets cell death by cytotoxic T cells and NK cells; thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. | ||

| GZMH | Cytotoxic chymotrypsin-like serine protease; probably necessary for target cell lysis in cell-mediated immune responses. | ||

| IL-16 | Cytokine-mediated immune response: stimulates migratory response in CD4+ lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils. | ||

| KIR3DL1 | Role in regulation of immune response (NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity). | ||

| DNA damage/repair | NBN | DNA integrity and genomic stability; component of MRE11-RAD50-NBN complex, which plays a crucial role in cellular response to DNA damage and maintenance of chromosome integrity. | |

| PARP-1 | Poly-ADP-ribosyl transferase with key role in DNA repair and methylation. | ||

| Protein that decreased | Growth factor | SPON2 | Cell adhesion protein; essential in initiation of innate immune response; represents unique pattern-recognition molecule for microbial pathogens. |

Threshold for statistically significant changes was P < .001. C1QTNF1, Complement C1q TNF-related protein 1; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FGF-19, fibroblast growth factor 19; GZMA/B/H, granzyme A/B/H; KIR3DL1, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1; NBN, nibrin; SPON2, spondin-2; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

We used CyTOF to measure immune cell expression to associate cellular expression with wildfire exposure on unsorted cells. A uniform manifold approximation and projection (aka UMAP), shown in Fig E2 in the Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org, highlights the different immune cell clusters predicted using FlowSOM from the given marker panel. These clusters belong to different cell types that were further evaluated for their association with changes in each relevant protein marker and ZFP during wildfire exposure. In cases of lung injury or inflammation, the integrity of the tight junctions may be compromised, leading to increased permeability of the airway walls and infiltration of immune cells, including NK cells. In summary, we found that NK and regulatory T-cell frequencies were marginally affected by acute exposure to wildfire air pollution.

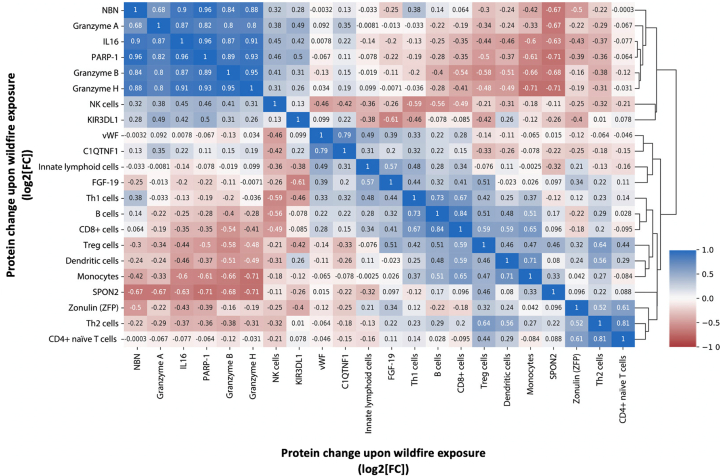

Correlation matrix between changes in identified proteins, cell phenotypes, and ZFP

On the basis of the correlation matrix findings (Fig 2), changes in immune cell phenotypes mostly clustered together; however, ZFP was associated with immune cell phenotypes showing significant correlations with naive CD4+ and TH2 cells. ZFP is a gut permeability marker that has been linked to obesity, diabetes, high body mass index, and even severe coronavirus disease 2019.16,30 Our findings further support the notion that ZFP is associated with immune responses and could play a role in signaling inflammation after skin barrier disruptions.15 However, a study using our ELISA kit found it targets a group that may be structurally and functionally related to zonulin rather than a known precursor.31 Nevertheless, the data from that study also indicated that the protein concentrations measured were associated with obesity and metabolic traits, warranting the need for further studies.

Fig 2.

Pearson correlation matrix between changes in identified proteins, change in ZFP, and change in immune cell phenotypes during wildfire exposure. Values represent absolute Pearson r correlation coefficients between log2-transformed fold changes. Blue and red indicate direct and reverse correlations, respectively. C1QTNF1, Complement C1q TNF-related protein 1; FGF-19, fibroblast growth factor 19; GZMA/B/H, granzyme A/B/H; KIR3DL1, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1; NBN, nibrin; SPON2, spondin-2; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

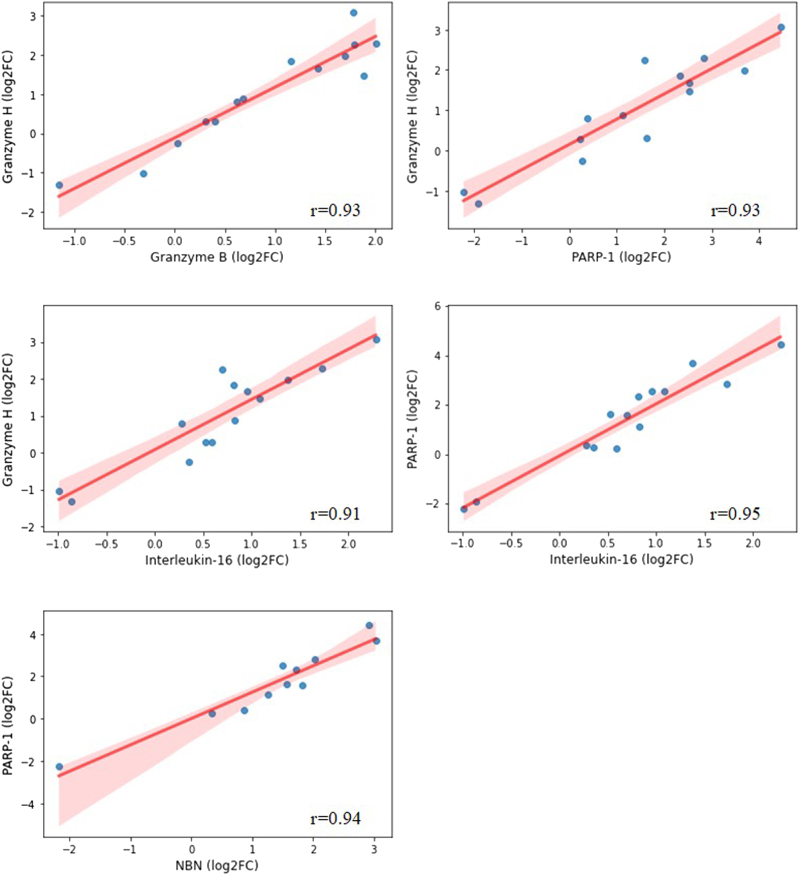

The largest cluster included protein changes that suggest a correlation between immune regulation pathways (IL-16, granzymes A, B, and H, and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1), DNA repair (PARP-1, nibrin), and NK cells. The cytotoxic activity of NK cells is mediated by the release of granzymes, and the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1 receptor has functional consequences in terms of NK cell recognition of targets, thus inducing apoptosis.32,33 Fig 3 shows the correlation plots between the changes with the highest R coefficients.

Fig 3.

Scatterplots for strongly correlated changes in proteins that increased during wildfire exposure (Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.90). Log2FC, Log2-transformed fold change; NBN, nibrin.

In cell-culture experiments, the release of IL-16 in response to coarse PM (PM2.5-10) suggests that pollution particles may promote antigen presentation and recruitment of T-helper lymphocytes.34 Another study showed that PM enhances the activation of caspases followed by the activation of PARP-1 in bronchial epithelial cells, triggering apoptosis.35 Furthermore, T cells stimulated with PM2.5 in the presence of macrophages present elevated granzyme expression.36 This might explain our findings of increased IL-16, PARP-1, and granzyme levels.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to comprehensively immunophenotype the same group of participants before and during exposure to wildfire smoke. Also, the timing of the wildfire exposure was consistent (11 days; range, 10-12 days). There are limitations to the broad-based conclusions we can draw because of our small sample size (n = 15). AQI was based on the daily average using the same continuous ambient monitoring station for all participants, which assumes that all participants were exposed to the same amount of wildfire smoke.

The fold changes in the cell types and the proteins of interest on wildfire exposure were not significantly different between participants with and without asthma (P > .05 for all comparisons), except potentially for complement C1q TNF-related protein 1 (P = .051). The small sample size does not permit adequate investigation of the association between asthma and outcomes; for this, further research is warranted. Also, within-subject studies are susceptible to bias because an individual’s initial physiologic outcome value can influence the extent and direction of postintervention responses; however, we only quantitated biological markers, so it is unlikely that the Hawthorne effect could be inducing these types of significant changes in their immune markers. Even with these limitations, we found significant differences over time. Further studies in cohorts exposed to wildfire smoke will be needed to test longitudinal immune changes during and after wildfire smoke exposure.

Footnotes

Supported by the Air pollution disrupts Inflammasome Regulation in HEart And Lung Total Health (AIRHEALTH) National Institutes of Health grants National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute P01HL152953 and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences R01ES032253; the Sean N. Parker Foundation; David A. Crown, PhD; the Naddisy Foundation; the Li family; the Barakett family; the Evergreen Foundation; the Binn Foundation; and the Hill Family Foundation.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Agache I., Sampath V., Aguilera J., Akdis C.A., Akdis M., Barry M., et al. Climate change and global health: a call to more research and more action. Allergy. 2022;77:1389–1407. doi: 10.1111/all.15229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansoor S., Farooq I., Kachroo M.M., Mahmoud A.E.D., Fawzy M., Popescu S.M., et al. Elevation in wildfire frequencies with respect to the climate change. J Environ Manage. 2022;301 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G., Guo Y., Yue X., Tong S., Gasparrini A., Bell M.L., et al. Mortality risk attributable to wildfire-related PM2.5 pollution: a global time series study in 749 locations. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5:e579–e587. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00200-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akdi C.A., Nadeau K.C. Human and planetary health on fire. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:651–652. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00776-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolhuter K., Arora M., Kovacic J.C. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: can the Australian bushfires and global COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 convince us to change our ways? BioEssays. 2021;43 doi: 10.1002/bies.202100046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadadu R.P., Grimes B., Jewell N.P., Vargo J., Young A.T., Abuabara K., et al. Association of wildfire air pollution and health care use for atopic dermatitis and itch. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:658–666. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akdis C.A. Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:739–751. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black C., Gerriets J.E., Fontaine J.H., Harper R.W., Kenyon N.J., Tablin F., et al. Early life wildfire smoke exposure is associated with immune dysregulation and lung function decrements in adolescence. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:657–666. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0380OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson M.D., Semmens E.O., Dumke C., Quindry J.C., Ward T.J. Measured pulmonary and systemic markers of inflammation and oxidative stress following wildland firefighter simulations. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:407. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prunicki M., Kelsey R., Lee J., Zhou X., Smith E., Haddad F., et al. The impact of prescribed fire versus wildfire on the immune and cardiovascular systems of children. Allergy. 2019;74:1989–1991. doi: 10.1111/all.13825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prunicki M.M., Dant C.C., Cao S., Maecker H., Haddad F., Kim J.B., et al. Immunologic effects of forest fire exposure show increases in IL-1β and CRP. Allergy. 2020;75:2356–2358. doi: 10.1111/all.14251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prunicki M., Miller S., Hopkins A., Poulin M., Movassagh H., Yan L., et al. Wildfire smoke exposure is associated with decreased methylation of the PDL2 gene. J Immunol. 2020;204(1 suppl) 146.17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prunicki M., Stell L., Dinakarpandian D., de Planell-Saguer M., Lucas R.W., Hammond S.K., et al. Exposure to NO2, CO, and PM2.5 is linked to regional DNA methylation differences in asthma. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10:2. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilera J., Han X., Cao S., Balmes J., Lurmann F., Tyner T., et al. Increases in ambient air pollutants during pregnancy are linked to increases in methylation of IL4, IL10, and IFNγ. Clin Epigenetics. 2022;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13148-022-01254-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fasano A. Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1258:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasano A. All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases. F1000Res 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Fasano A. Zonulin measurement conundrum: add confusion to confusion does not lead to clarity. Gut. 2021;70:2007–2008. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohlsson B., Orho-Melander M., Nilsson P.M. Higher levels of serum zonulin may rather be associated with increased risk of obesity and hyperlipidemia, than with gastrointestinal symptoms or disease manifestations. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:582. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripathi A., Lammers K.M., Goldblum S., Shea-Donohue T., Netzel-Arnett S., Buzza M.S., et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16799–16804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906773106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X., Memon A.A., Palmér K., Hedelius A., Sundquist J., Sundquist K. The association of zonulin-related proteins with prevalent and incident inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-02075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giron L.B., Dweep H., Yin X., Wang H., Damra M., Goldman A.R., et al. Plasma markers of disrupted gut permeability in severe COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.686240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romem A., Lammers K., Iacono A.T., Tulapurkar M.E., Dranchenberg C., Hasday J.D., et al. Lung epithelium, submucosal glands and smooth muscle. American Thoracic Society; New York: 2012. Zonulin—a novel player in human lung pathophysiology; p. A4266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sturgeon C., Fasano A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2016;4 doi: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1251384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benard A., Desreumeaux P., Huglo D., Hoorelbeke A., Tonnel A.B., Wallaert B. Increased intestinal permeability in bronchial asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hijazi Z., Molla A., Al-Habashi H., Muawad W., Sharma P. Intestinal permeability is increased in bronchial asthma. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:227–229. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.027680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fasano A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:151–175. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brook R.D., Rajagopalan S., Pope C.A., III, Brook J.R., Bhatnagar A., Diez-Roux A.V., et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadley M.B., Vedanthan R., Fuster V. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a window of opportunity. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:193–194. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rückerl R., Schneider A., Breitner S., Cyrys J., Peters A. Health effects of particulate air pollution: a review of epidemiological evidence. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23:555–592. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.593587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiorito S., Soligo M., Gao Y., Ogulur I., Akdis C.A., Bonini S. Is the epithelial barrier hypothesis the key to understanding the higher incidence and excess mortality during COVID-19 pandemic? The case of Northern Italy. Allergy. 2022;77:1408–1417. doi: 10.1111/all.15239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheffler L., Crane A., Heyne H., Tönjes A., Schleinitz D., Ihling C.H., et al. Widely used commercial ELISA does not detect precursor of haptoglobin2, but recognizes properdin as a potential second member of the zonulin family. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:22. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper M.A., Fehniger T.A., Caligiuri M.A. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Connor G.M., Guinan K.J., Cunningham R.T., Middleton D., Parham P., Gardiner C.M. Functional polymorphism of the KIR3DL1/S1 receptor on human NK cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:235–241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker S., Soukup J. Coarse (PM2.5-10), fine (PM2.5), and ultrafine air pollution particles induce/increase immune costimulatory receptors on human blood–derived monocytes but not on alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2003;66:847–859. doi: 10.1080/15287390306381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamdar O., Le W., Zhang J., Ghio A., Rosen G., Upadhyay D. Air pollution induces enhanced mitochondrial oxidative stress in cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3601–3606. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Q.Y., Huang D.Y., Zhang H.J., Wang S., Chen X.F. Exposure to particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) induced macrophage-dependent inflammation, characterized by increased Th1/Th17 cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;50:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.