Abstract

Recognizing multiple neuropathological entities in people with dementia improves understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, and expected outcomes from therapies. Care for the individual with dementia includes the evaluation and management of diseases associated with the aged brain, most commonly neurodegeneration and vascular brain injury (VBI). Terminology has evolved to keep pace with diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic advances, and autopsy studies have shown that multiple comorbid neuropathological entities are the rule, not the exception, especially in older individuals. With the advent of disease-modifying therapies, delivering dementia care requires an encompassing framework that allows clinicians to consider all of an individual’s underlying diseases and their contributions to symptom burden. A diagnostic approach, common co-occurring pathologies, and implications for current and future clinical care are reviewed.

Disambiguating Diagnoses in Dementia Care

People who present to a neurology clinic with cognitive, behavioral, or movement concerns are informed of having 1 or more than 1 diagnosis. Terms such as mild cognitive impairment, corticobasal syndrome, and Alzheimer disease (AD) all may be used accurately within a patient’s visit. Diagnostic terms can be confusing for both patients and health care providers. Educating patients on the relationships among diagnostic terms can increase illness understanding and provide a framework for ongoing discussion. A sample structured approach to diagnosis disclosure and documentation that includes 3 diagnostic categories—1) severity, 2) syndrome, and 3) etiology—is presented (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

A FRAMEWORK FOR DOCUMENTING DIAGNOSES

| The patient meets diagnostic criteria for the following, interrelated diagnoses: | |

|---|---|

| Severity | Normal cognition |

| Subjective cognitive impairment | |

| Mild cognitive impairment | |

| Dementia | |

| Syndrome | Amnestic single/multidomain syndrome |

| Traumatic encephalopathy syndrome | |

| Posterior cortical atrophy | |

| Primary progressive aphasia and its variants | |

| Behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | |

| Richardson syndrome | |

| Corticobasal syndrome | |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | |

| LATE (limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy) | |

| Etiologic | Alzheimer disease |

| Chronic traumatic encephalopathy | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |

| TDP-43 and its subtypes | |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | |

| Pick disease | |

| Corticobasal degeneration | |

| Argyrophilic grain disease | |

| Lewy body disease | |

| LATE-NC (limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy-neuropathologic change) | |

Severity refers to the degree to which symptoms are accompanied by measurable deficits and disruption of day-to-day function. When cognitive test performance remains within expectations for age, the term “subjective cognitive concerns” often is used. “Mild cognitive impairment“ refers to when test results fall below expectations but do not interfere with daily activities. “Dementia” is the term for when instrumental activities of daily living require assistance. A syndrome is defined by the pattern of symptoms reported in the history and the findings on neurologic examination, cognitive assessment, and structural neuroimaging. The syndrome is driven by the anatomy. The etiology is the predicted neuropathological diagnosis (or “disease”) that best accounts for the syndrome. In this way, the syndrome refers to “where” the disease is localized, and the disease refers to “what” the disease might be.

Clinical Reasoning Peers Through a Sometimes Foggy Lens

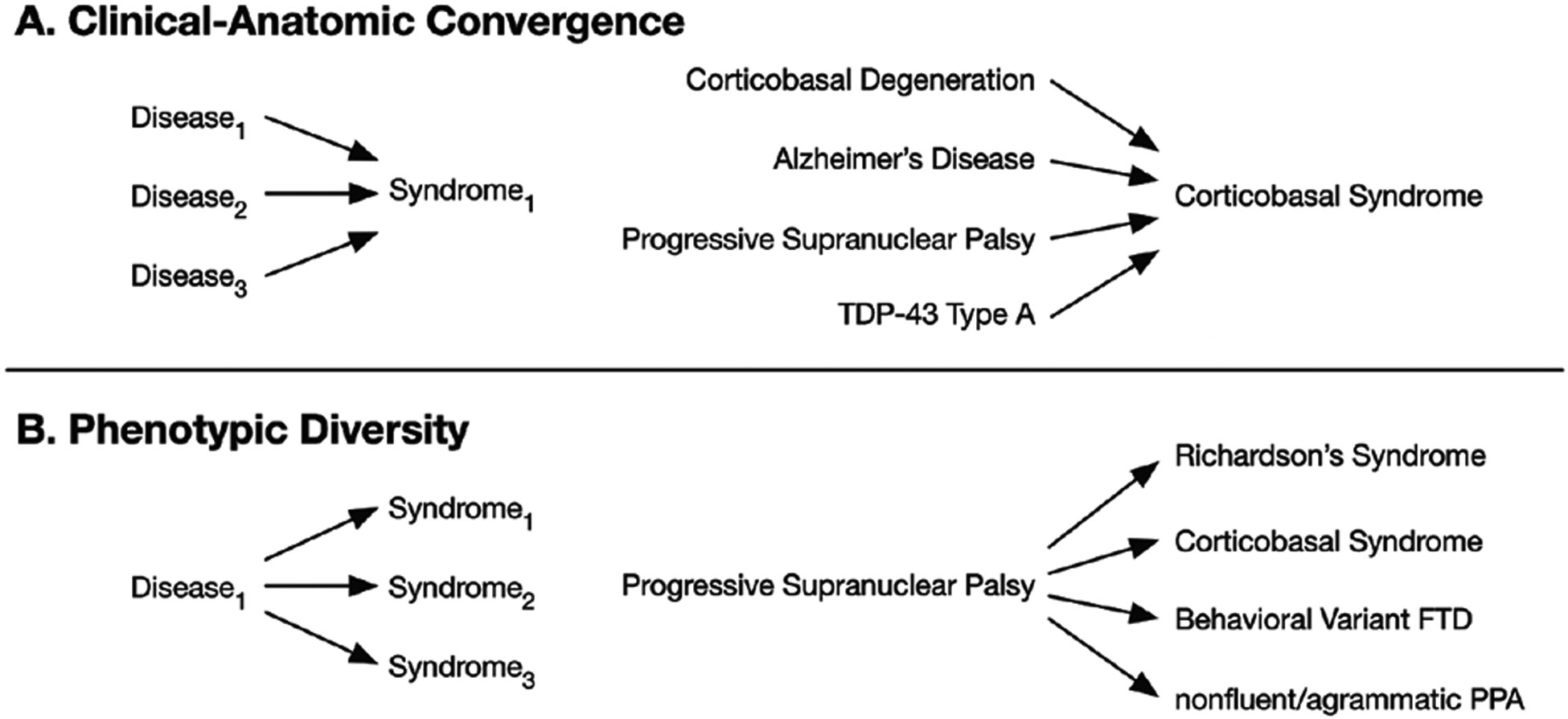

The syndromic diagnosis should prompt the clinician to consider an etiologic differential diagnosis. Each syndrome is associated with a list of possible causes resulting from the observation that multiple distinct diseases can converge on the same brain systems. This clinical–anatomic convergence (Figure 1) creates clinical uncertainty about which of the several possible causes may contribute to a given syndrome. In addition, each neurodegenerative disease can disrupt a finite number of specific neuroanatomic circuits, each associated with a specific clinical syndrome. This phenotypic diversity (Figure 1) further contributes to the absence of any perfect, one-to-one correspondence between a clinical syndrome and a neuropathological diagnosis. However, there are some common syndromes that predict the primary etiology well; for example, an amnestic syndrome for AD, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia for AD, posterior cortical atrophy for AD, or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) for Lewy body disease (LBD). Behavioral neurologists, who may be certified by the United Council of Neurologic Subspecialties, specialize in navigating syndromic diagnoses, such as the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, for which the etiologic differential diagnosis is lengthy. Molecular biomarkers for specific underlying proteinopathies are available clinically for AD and LBD and may be used to confirm their presence; however, most underlying causes cannot be measured directly, so the neurologist must base predictions on experience and available information in the literature.

Figure 1.

Relating syndrome and neuropathology. There is not a one-to-one correspondence between a dementia syndrome and a neurodegenerative disease. The syndrome reflects neuroanatomy, not etiology. The concepts of clinical–anatomic convergence (A) and phenotypic diversity (B) are demonstrated with some examples. FTD, frontotemporal dementia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

Accurate etiologic diagnosis can inform a patient’s prognosis and potential therapies. Specific discussion regarding prognosis, anticipatory guidance, and symptomatic therapies for all the different syndromes and their potential causes is beyond the scope of this review. Amyloid-lowering therapies are emerging for AD. Most are monoclonal antibodies targeting beta-amyloid.1 Early identification of AD proteins through molecular testing of cerebrospinal fluid or PET studies (using amyloid-binding tracers) allows for earlier referral for disease-modifying therapy, and the development of blood tests may increase earlier referrals from primary care clinics.

Etiologic prediction is complicated by the prevalence of copathology. Older people with cognitive impairment often have more than 1 neurodegenerative disease or VBI, or both, on autopsy.2–4 The prevalence of copathology is associated with increasing age; genetic factors, including APOE genotype3,5; and prolonged survival.6 In addition, early age at onset (ie, younger than 65 years) of AD pathology usually involves copathology,4 so neurologists will need to account for multiple pathologies for all individuals who present with cognitive impairment. Some of the more common combinations of neuropathologies have been described well, but more work is needed.

Amnestic Syndrome, AD, and Copathologies

An amnestic syndrome that localizes to mesial temporal lobe structures (parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus) is characterized by a relatively intact learning curve followed by impaired retrieval of verbal or visual information after a short delay because of impaired encoding and consolidation. The most common neurodegenerative cause is AD, although the differential diagnosis includes VBI, limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy–neuropathologic change (LATE-NC) with or without hippocampal sclerosis, and argyrophilic grain disease. However, a pure amnestic syndrome is less common and often reflects several early-stage pathological entities (AD, LATE-NC, argyrophilic grain disease) combining to undermine memory function before widespread dissemination of disease.

Cerebrovascular disease encompasses vessel wall disease, including atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), and VBI, defined as parenchymal injury from ischemia or hemorrhage, and the relationship among vascular disease, its risk factors, and AD pathology is well-documented.7 The seminal Nun Study showed that ischemic lacunes and larger infarcts alone are weakly correlated with poor cognition, but in the presence of AD pathology, they increase the risk for dementia.8 The amplifying effect of VBI has been replicated, and the independent contributions of vascular disease on cognition, including through neuroinflammatory pathways, are under investigation.9 In the new era of disease modifying therapy for AD, CAA has become a subject of intense interest because of its contribution to the risk for amyloid-related imaging abnormality (ARIA), a complication of anti–amyloid antibody therapy. A recent meta-analysis estimates the prevalence of CAA neuropathology in confirmed AD to be 48%, vs the estimated 5% to 7% in the cognitively normal older adult population.10 AD and CAA are associated with APOE ε4 genotype, and the APOE ε4 allele increases the risk for ARIA in a dose-dependent manner.1,11 In addition, evidence suggests that CAA independently contributes to cognitive decline beyond microhemorrhages and leukoencephalopathy.12

LATE-NC is strongly associated with advanced age and is present in 20% to 50% of individuals older than 80 years according to data from large autopsy studies.13 LATE-NC may result in an amnestic syndrome on its own, and in the presence of AD pathology, LATE-NC leads to faster and more severe decline than either LATE-NC or AD alone and in a dose-response manner by LATE-NC stage.14–17 Underscoring the contribution of LATE-NC, the contribution to cognitive decline is estimated to be nearly half of the contribution from AD.13

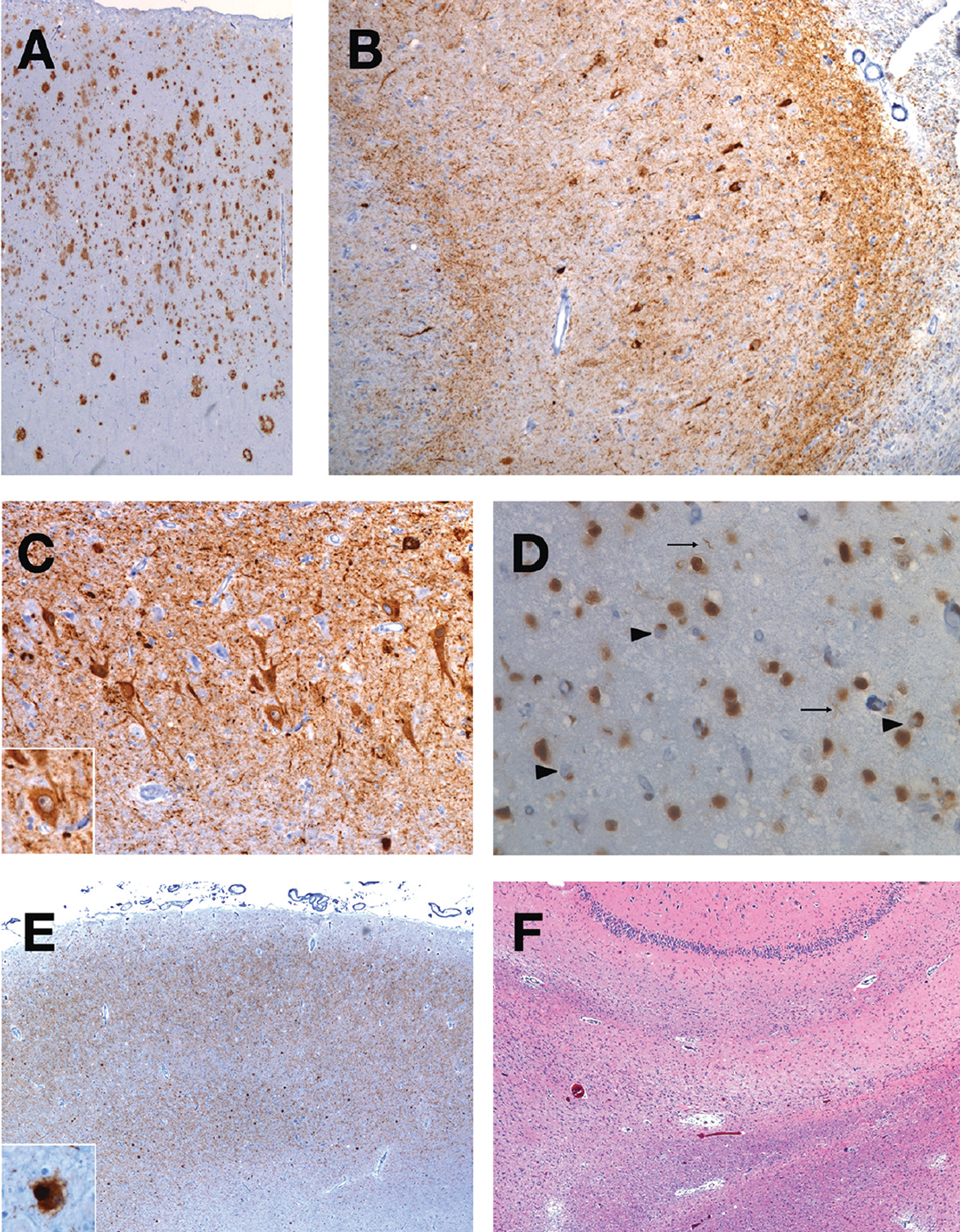

LBD pathology is prevalent in both early-onset and late-onset AD4,18 as well as in autosomal-dominant AD.19 When LBD accompanies well-developed AD, there is greater cognitive decline than seen with AD or LBD alone.20 However, only 2.1% of the LBD copathology cases were diagnosed antemortem in 1 study,20 owing to absence of the canonical features of DLB, such as visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, or parkinsonism, and perhaps a difficulty in determining whether attentional fluctuations were attributable to LBD.20,21 Amygdala-predominant LBD, being less widespread and therefore unlikely to manifest the core symptoms of DLB, also may have lesser pathophysiologic effect than when both AD and LBD are widespread and possibly synergistic.22–24 Further complicating etiologic differential diagnosis, AD, LBD, and LATE-NC may co-occur and be accompanied by other entities.4,25,26 Figure 2 illustrates the number of different pathologies that may be found in a single case of an amnestic syndrome.

Figure 2.

An illustrative case of the presence of many neuropathological entities. A single case of an 86-year-old woman from the UCSF Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank demonstrates the presence of multiple neuropathological diagnoses. She presented at 72 years of age with a late-onset, primary amnestic syndrome and later involvement of executive, language, and psychiatric domains. She developed mild parkinsonism and apraxia. Postmortem examination using immunohistochemistry revealed the hallmark amyloid-beta plaques (A) and neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads (B) of Alzheimer disease, shown here in the angular gyrus and hippocampus CA1 region, respectively. With an anti-tau antibody, the hippocampus CA2 region also showed diffuse, granular neurocytoplasmic inclusions (C) with perinuclear halos (inset), consistent with argyrophilic grain disease. In the entorhinal cortex, LATE-NC (limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy–neuropathological change) is present with immunohistochemistry for TDP-43 (D), which shows neurocytoplasmic inclusions (large arrows) and threads (small arrows). Alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry also shows Lewy body disease in the amygdala (E) that also was present in the substantia nigra (inset). On a hematoxylin & eosin stain of the hippocampus (F), a thin, astrogliotic, neuron-depleted subiculum is seen, indicating hippocampal sclerosis. Not depicted is the presence of vascular brain injury with microinfarcts, arteriolosclerosis, and mild cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Eight different neuropathological diagnoses were present in this case.

LBD, AD, and Other Copathologies

The Lewy body dimentias includes DLB and Parkinson disease dementia (PDD), differentiated by whether the most pronounced symptoms in the first year are cognitive (DLB) or motor (PDD, following an initial diagnosis of Parkinson disease). Although not always recognized, both are preceded by mild cognitive impairment27,28 and are characterized by executive dysfunction and visual processing difficulties. They often are accompanied by the more specific core phenotypic features of motor parkinsonism (required for PDD), attentional fluctuations, REM sleep behavior disorder, or visual hallucinations.29 Many of the more specific features reflect underlying LBD in distinct brainstem nuclei (eg, parkinsonism from substantia nigra LBD), but LBD pathology may be identified and staged by its presence in the brainstem, limbic structures, and neocortex30; however, there is considerable heterogeneity within the DLB syndrome,31 at least in part from the prevalence of AD copathology. In up to half of LBD cases, AD neuropathology also is observed,18,32 and an increased cortical tangle load is associated with worse cognition and presence of PDD compared with Parkinson disease without dementia.33–35 AD pathology also is associated with dysphoria in DLB.36 Furthermore, increasing LBD pathology load is associated independently and synergistically with AD pathology, with shorter survival time.37 In some individuals with mixed pathology, the absence of specific DLB features may lead a clinician to predict only AD, particularly when the AD tangle burden is high (ie, greater than Braak tangle stage IV).38–40

Other copathologies complicate the LBD landscape. In individuals with DLB or PD, atherosclerosis, infarcts, and small-vessel disease each is inversely correlated with the degree of LBD pathology.41 In addition, white matter hyper-intensity volume, as a marker for VBI, was positively correlated with visual hallucinations and gray matter atrophy but negatively correlated with parkinsonism and REM sleep behavior disorder.42 Together, these studies suggest that VBI may amplify underlying neocortical LBD, similar to the effect of VBI seen on AD pathology, but not brainstem LBD. In addition, CAA is observed in up to 2-thirds of people with LBD,26 and CAA burden is positively correlated with LBD stage (ie, increasing CAA is correlated with neocortical over brainstem LBD).41 LATE-NC copathology also is observed with LBD and is associated with greater LBD burden and the presence of AD copathology.13,25,26

Clinical Implications for Copathologies

Given their effects on a patient’s clinical course, copathologies should be considered in the neurologist’s etiologic differential because they affect prognosis and may influence anticipatory guidance. For example, a patient with an amnestic syndrome thought to be attributable to AD may benefit from an explanation of copathology if parkinsonian symptoms later develop. In another patient, the relative degree of small vessel disease may influence how much emphasis is placed on treating vascular risk factors and the expected outcomes of adherence: the rate of cognitive decline driven primarily by VBI may slow with aggressive risk factor modification. Therefore, establishing the absence of neurodegenerative diseases in a patient with VBI may enhance motivation and adherence.

In the disease-modifying era for AD, recognizing comorbid pathological entities will become central to managing expectations around treatment. The risk for symptomatic ARIA increases with the presence of CAA, and using the presence of lobar microhemorrhages as an imaging biomarker substantially underestimates CAA.10 Beyond predicting risk from therapy, the presence of copathology may alter expectations for benefit from amyloid-lowering treatment. Studies have not examined whether patients with LBD copathology have a positive response to amyloid-lowering therapy; therefore, if an amnestic syndrome is present in a person with positive AD biomarkers, the contribution of the amnestic syndrome to cognitive decline may remain if unaltered by amyloid removal. Biomarker testing for LBD is clinically available but not always covered by insurance, nor is it pursued routinely in neurology clinics.43,44 An individual with amnestic syndrome and positive AD biomarkers may have LATE-NC copathology, for which there is no available biomarker. In contrast, a hypothetical 70-year-old man with DLB has a 50% probability of receiving positive results on an amyloid PET study.45 If this individual were misdiagnosed, he might be treated with amyloid-lowering therapy. However, patients with LBD were excluded from clinical trials, so the risk profile in this population is unknown. The patient could be harmed without known potential for benefit. There is a growing appreciation for the need to account for copathologies in clinical trial design46; in a future where disease-modifying therapies are hoped to exist for more than one proteinopathy, a cocktail aimed at multiple targets might be used, analogous to current oncology practice. In the meantime, caution must be exercised, and a pathological entity should be targeted only if it provides the best explanation for a patient’s syndrome and clinical severity.

Summary

Evaluation of cognitive impairment from neurodegeneration and VBI involves the use of interrelated terms. Adopting a structured approach to term use promotes clarity of thought and communication with patients. Carefully describing a patient’s syndrome and additional symptoms enhances prediction of the underlying etiologies. Indeed, multiple etiologies is the rule, especially in older individuals, and considering patient heterogeneity in this light leads to a more thoughtful interpretation of available biomarkers. Weighing the relative contributions of each neuropathological entity to the patient’s clinical picture is required for the judicious use of current and potential future protein-targeting, disease-modifying therapies. Although behavioral neurologists will continue to provide expertise in interpreting complex clinical pictures, all neurologists are called to treat the aging population’s most common neurodegenerative diseases and their equally common copathologies with precision.

Disclosures

Dr. Fischer has no disclosures to report. He is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (T32-AG023481, PI Dr. Howard J. Rosen).

Dr. Seeley has no relevant disclosures to report.

The UCSF Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank is supported in part by the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P30-AG062422).

Contributor Information

D. Luke Fischer, Behavioral Neurology Clinical Fellow Memory and Aging Center Department of Neurology Weill Institute for Neurosciences University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA.

William W. Seeley, Memory and Aging Center Department of Neurology Weill Institute for Neurosciences University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini RE, Rodriguez RD, et al. Neuropathological diagnoses and clinical correlates in older adults in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karanth S, Nelson PT, Katsumata Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical phenotype of quadruple misfolded proteins in older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(10):1299–1307. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spina S, La Joie R, Petersen C, et al. Comorbid neuropathological diagnoses in early versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2021;144(7):2186–2198. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson JL, Lee EB, Xie SX, et al. Neurodegenerative disease concomitant proteinopathies are prevalent, age-related and APOE4-associated. Brain. 2018;141(7):2181–2193. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulthard EJ, Love S. A broader view of dementia: multiple co-pathologies are the norm. Brain. 2018;141(7):1894–1897. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease: the Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iadecola C, Smith EE, Anrather J, et al. The neurovasculome: key roles in brain health and cognitive impairment: a scientific state-ment from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. Published online April 3, 2023. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakel L, De Kort AM, Klijn CJM, Schreuder F, Verbeek MM. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(1):10–28. doi: 10.1002/alz.12366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salloway S, Chalkias S, Barkhof F, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in 2 phase 3 studies evaluating aducanumab in patients with early Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(1):13–21. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.4161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Gurol ME, et al. Emerging concepts in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2017;140(7):1829–1850. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Limbic-predominant Age-related TDP-43 Encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. 2019;142(6):1503–1527. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, et al. TDP-43 is a key player in the clinical features associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):811–824. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1269-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, et al. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer’s disease impact clinical features. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(5):697–709. doi: 10.1002/ana.24493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James BD, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Trojanowski JQ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 stage, mixed pathologies, and clinical Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Brain. 2016;139(11):2983–2993. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nag S, Yu L, Wilson RS, Chen EY, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology and memory impairment in elders without pathologic diagnoses of AD or FTLD. Neurology. 2017;88(7):653–660. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toledo JB, Cairns NJ, Da X, et al. Clinical and multimodal biomarker correlates of ADNI neuropathological findings. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:65. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leverenz JB, Fishel MA, Peskind ER, et al. Lewy body pathology in familial Alzheimer disease: evidence for disease- and mutation-specific pathologic phenotype. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(3):370–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malek-Ahmadi M, Beach TG, Zamrini E, et al. Faster cognitive decline in dementia due to Alzheimer disease with clinically undiagnosed Lewy body disease. PloS One. 2019;14(6):e0217566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roudil J, Deramecourt V, Dufournet B, et al. Influence of Lewy pathology on Alzheimer’s disease phenotype: a retrospective clinico-pathological study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(4):1317–1323. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchikado H, Lin WL, DeLucia MW, Dickson DW. Alzheimer disease with amygdala Lewy bodies: a distinct form of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(7):685–697. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000225908.90052.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorrentino ZA, Goodwin MS, Riffe CJ, et al. Unique alpha-synuclein pathology within the amygdala in Lewy body dementia: implications for disease initiation and progression. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0787-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swirski M, Miners JS, de Silva R, et al. Evaluating the relationship between amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein phosphorylated at Ser129 in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(5–8):77. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0077-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashi S, Iseki E, Yamamoto R, et al. Concurrence of TDP-43, tau and alpha-synuclein pathology in brains of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 2007;1184:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAleese KE, Walker L, Erskine D, Thomas AJ, McKeith IG, Attems J. TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and ageing. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(4):472–479. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeith IG, Ferman TJ, Thomas AJ, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2020;94(17):743–755. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Litvan I, Goldman JG, Troster AI, et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):349–356. doi: 10.1002/mds.24893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attems J, Toledo JB, Walker L, et al. Neuropathological consensus criteria for the evaluation of Lewy pathology in post-mortem brains: a multi-centre study. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141(2):159–172. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02255-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halliday GM, Holton JL, Revesz T, Dickson DW. Neuropathology underlying clinical variability in patients with synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(2):187–204. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0852-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin DJ, Hurtig HI. The contribution of tau, amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein pathology to dementia in Lewy body disorders. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism. 2018;8(4). doi: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irwin DJ, White MT, Toledo JB, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):587–98. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Weintraub D, et al. Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30291-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coughlin D, Xie SX, Liang M, et al. Cognitive and pathological influences of tau pathology in Lewy body disorders. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(2):259–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.25392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Oliveira FF, Miraldo MC, de Castro-Neto EF, et al. Associations of neuropsychiatric features with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of amyloidogenesis and neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively healthy people. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81(3):1295–1309. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferman TJ, Aoki N, Crook JE, et al. The limbic and neocortical contribution of alpha-synuclein, tau, and amyloid beta to disease duration in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisman D, Cho M, Taylor C, Adame A, Thal LJ, Hansen LA. In dementia with Lewy bodies, Braak stage determines phenotype, not Lewy body distribution. Neurology. 2007;69(4):356–359. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266626.64913.0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiraboschi P, Attems J, Thomas A, et al. Clinicians’ ability to diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies is not affected by beta-amyloid load. Neurology. 2015;84(5):496–499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferman TJ, Aoki N, Boeve BF, et al. Subtypes of dementia with Lewy bodies are associated with alpha-synuclein and tau distribution. Neurology. 2020;95(2):e155–e165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghebremedhin E, Rosenberger A, Rub U, et al. Inverse relationship between cerebrovascular lesions and severity of lewy body pathology in patients with Lewy body diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(5):442–448. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d88e63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira D, Nedelska Z, Graff-Radford J, et al. Cerebrovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and clinical phenotype in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;105:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bongianni M, Ladogana A, Capaldi S, et al. alpha-Synuclein RT-QuIC assay in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(10):2120–2126. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donadio V, Incensi A, Rizzo G, et al. A new potential biomarker for dementia with Lewy bodies: skin nerve alpha-synuclein deposits. Neurology. 2017;89(4):318–326. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ossenkoppele R, Jansen WJ, Rabinovici GD, et al. Prevalence of amyloid PET positivity in dementia syndromes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1939–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toledo JB, Abdelnour C, Weil RS, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: impact of co-pathologies and implications for clinical trial design. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(1):318–332. doi: 10.1002/alz.12814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]