Abstract

The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is a mandatory pay-for-performance program through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that aims to incentivize high-quality care, promote continuous improvement, facilitate electronic exchange of information, and lower health care costs. Previous research has highlighted several limitations of the MIPS program in assessing nephrology care delivery, including administrative complexity, limited relevance to nephrology care, and inability to compare performance across nephrology practices, emphasizing the need for a more valid and meaningful quality assessment program. This article details the iterative consensus-building process used by the American Society of Nephrology Quality Committee from May 2020 to July 2022 to develop the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MIPS Value Pathway (MVP). Two rounds of ranked-choice voting among Quality Committee members were used to select among nine quality metrics, 43 improvement activities, and three cost measures considered for inclusion in the MVP. Measure selection was iteratively refined in collaboration with the CMS MVP Development Team, and new MIPS measures were submitted through CMS's Measures Under Consideration process. The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP was published in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule and includes measures related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker use, hypertension control, readmissions, acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, and advance care planning. The nephrology MVP aims to streamline measure selection in MIPS and serves as a case study of collaborative policymaking between a subspecialty professional organization and national regulatory agencies.

Keywords: CKD, health policy

Introduction

Pay-for-performance (P4P) programs have proliferated in the United States with the goal of improving health outcomes and controlling rising health care costs.1–3 The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is a mandatory P4P program administered through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), authorized by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015.4,5 MIPS aims to incentivize high-quality care, promote continuous quality improvement, facilitate exchange of electronic information, and lower health care costs by assigning financial bonuses and penalties to participating clinicians on the basis of four performance categories: Quality, Promoting Interoperability, Improvement Activities, and Cost.6 Nephrology clinicians including physicians and advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) caring for Medicare beneficiaries are required to participate in MIPS, unless they are participating in a qualifying Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM) such as Kidney Care Choices.7 As the largest P4P program in the United States, with 954,664 clinicians (including 7310 nephrologists) participating in 2019, there is potential to harness MIPS to meaningfully improve kidney care delivery and associated clinical outcomes at a national scale.8

CKD is highly prevalent and results in large Medicare expenditures, particularly in its most advanced stages. Approximately 14.2% of patients with Medicare fee-for-service have diagnosed CKD, with annual per beneficiary spending exceeding $26,000 per year.9 Unfortunately, significant gaps remain in quality of care for patients with CKD, ranging from insufficient early identification and timely nephrology referral by primary care providers to missed opportunities to slow CKD and prepare for kidney replacement therapy. Only about half of all patients with CKD with albuminuria receive angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEi/ARB) therapy.10,11 Only half of Medicare beneficiaries with diagnosed CKD stage G4 or G5 saw a nephrologist in 2019, contributing to inadequate modality education, suboptimal dialysis access planning, delayed transplant referral and consideration for preemptive transplantation, and high rates of crash start dialysis.9,12 Despite these persistent gaps in quality of care, nephrologists perform very well in the MIPS program with over half of participants earning the highest possible score and over 90% of participants receiving a financial bonus.13 This discrepancy between nephrologist MIPS performance and observed clinical outcomes demonstrates the limitations in the current MIPS program structure to improve care for CKD.

P4P programs are effective in improving chronic disease care, with randomized clinical trials showing improved BP control and other cardiovascular processes of care.14,15 However, while a systematic review of 69 studies found that P4P programs were associated with short-term process of care improvements, longer-term effects on clinical outcomes were unclear.3 Several frameworks outline key design considerations for an effective P4P program, including (1) choosing domains within clinician control, (2) ensuring the program is easy to understand, (3) avoiding teaching to the test, and (4) involving clinicians in program design.1,16–18 The current MIPS program does not adequately incorporate these key considerations for kidney care. First, in 2022, nephrology clinicians had to select from a large menu of over 200 MIPS quality measures, most of which are not relevant to nephrology care.13 Second, the large number of measures adds to program complexity and administrative burden, favoring higher-resourced practices.19 Regulatory burden and administrative tasks are a major driver of burnout and increased practice costs.20,21 Third, MIPS currently allows nephrology clinicians to choose measures they are likely to score well on and limits the ability to compare across nephrology practices. Given these significant limitations in MIPS program design, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission urged CMS in 2018 to eliminate MIPS and transition to a simplified set of metrics.22

In response to this feedback, CMS has modified MIPS by creating the MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) program.23 MVPs have several guiding principles (Supplemental Exhibit 1). First, MVPs seek to streamline measure selection by providing a core measure set that is meaningful for a specialty or clinical condition.24 Second, MVP measures should follow CMS's Meaningful Measures framework, incorporating patient-centered quality measures, health equity–oriented measures, and digital quality measures.25 Finally, MVPs should serve as a gateway toward APM participation by including measures also found in these models (Supplemental Exhibit 2).

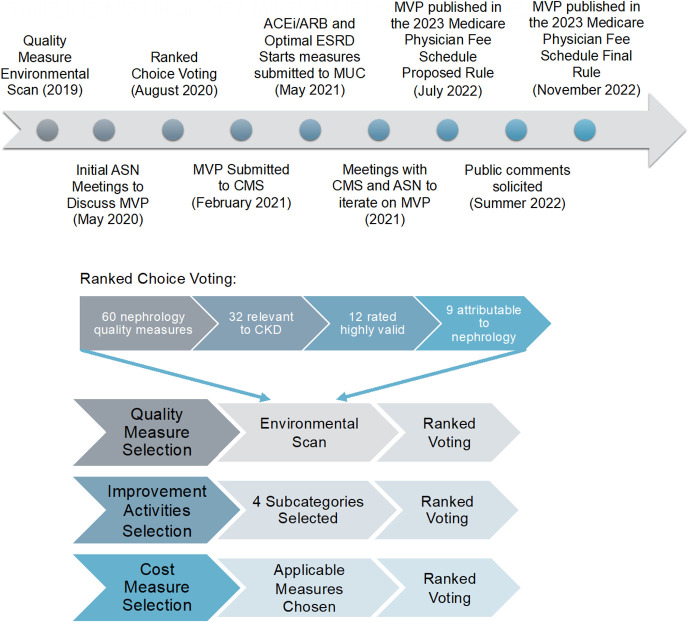

From May 2020 to July 2022, the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Quality Committee pursued a multistep consensus-building process to develop a nephrology MVP entitled Optimal Care for Kidney Health (Figure 1). This article details the MVP development process and our collaborative policymaking efforts with CMS. We also highlight limitations of the MVP and plans for future refinement.

Figure 1.

Overview of the MVP development process. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASN, American Society of Nephrology; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; MVP, MIPS Value Pathway. Figure 1 can be viewed in color online at www.jasn.org.

Methods

Initial Measure Selection

MVPs consist of performance measures in four categories: (1) Quality, (2) Improvement Activities, (3) Cost, and (4) Population Health and Promoting Interoperability category, the latter of which is consistent across all MVPs. We started with the quality measure environmental scan conducted in 2019, which systematically reviewed 60 quality measures from five national organizations.26 The ASN Quality Committee previously rated each quality measure according to five domains of validity as outlined by the American College of Physicians: importance, appropriate care, evidence base, specifications, and feasibility and acceptability.27 We defined validity as “the measure is correctly assessing what it is designed to measure, adequately distinguishing good and poor quality.”27

Among 60 quality measures, 32 were relevant to CKD (nondialysis); we included the 12 CKD quality measures highly rated by the committee and excluded three measures not attributable to nephrologists, leaving nine quality measures for MVP consideration. For Improvement Activities, the committee reviewed the list of 106 measures provided by CMS and ranked eight subcategories in order of importance to nephrology, leaving 43 measures for MVP consideration in the subcategories of Population Management, Care Coordination, Beneficiary Engagement, and Achieving Health Equity. In performance year 2019, only two cost measures were deemed relevant to nephrology: Total Per Capita Costs (TPCC) and Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary.6 An episode-based cost measure, Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis, was added to MIPS in performance year 2020.

Ranked-Choice Voting

Ranked-choice voting was used to select among the nine quality, 43 improvement activities, and two cost measures for inclusion in the nephrology MVP. Ranked-choice voting allows participants to select multiple items in their order of preference. The ASN Quality Committee comprises nephrologists with expertise in clinical nephrology (adult and pediatric), health care policy, quality measurement, and quality improvement. Before voting, the structure and guiding principles of MVPs were reviewed through virtual teleconferences, and a spreadsheet with each measure's description was circulated to the committee. Committee members were instructed to “Rank (drag and drop) the following measures, with 1 being the most important” for the nephrology MVP. Voting occurred through Qualtrics in August to September 2020. Measures were ordered from lowest to highest mean ranking. Full voting results are listed in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1. Three authors (SLT, SAS, MLM) also categorized measures into the six domains of health care quality as outlined by the Institute of Medicine: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity.28

Table 1.

Measures in the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP

| Measure ID | Measure Title | Description | Rationale for Inclusion in MVP | ASN Quality Committee Ranking | Measure Validity Ratinga or CMS Weightingb | IOM Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | ||||||

| Quality ID 001 NQF 0059 CMS eCQM ID: CMS122v10 |

Diabetes: HbA1c poor control (>9%)c | Percentage of patients aged 18–75 yr with diabetes who had hemoglobin A1c >9.0% during the measurement period. | Diabetes control reduces the risk of CKD progression, and diabetes control is suboptimal in the United States.46–49 | —d | Medium | Effective |

| Quality ID 482 | Hemodialysis vascular access: practitioner level long-term catheter ratec | Percentage of adult hemodialysis patient-months using a catheter continuously for 3 mo or longer for vascular access attributable to an individual practitioner or group practice. | Catheter use is associated with increased risk of bloodstream infections and mortality.50 | — | — | Safe |

| NQF 1662 | Adult kidney disease: ACE inhibitor or ARB therapye | Percentage of patients aged 18 yr and older with a diagnosis of CKD (stages 1–5, not receiving RRT) and proteinuria who were prescribed ACEi or ARB therapy within a 12-mo period. | ACEi/ARBs reduce the risk of kidney disease progression in individuals with CKD.51,52 | 1 | High | Effective |

| Quality ID 047 NQF 0326 |

Advance care plan | Percentage of patients aged 65 yr and older who have an advance care plan or surrogate decision-maker documented in the medical record or documentation in the medical record that an advance care plan was discussed, but the patient did not wish or was not able to name a surrogate decision-maker or provide an advance care plan. | Patients with advanced CKD face high morbidity and mortality, necessitating patient-centered advance care planning.53 | 8 | High | Patient-centered |

| Quality ID 110 NQF 0041 CMS eCQM ID: CMS147v11 |

Preventive care and screening: influenza immunization | Percentage of patients aged 6 mo and older seen for a visit between October 1 and March 31 who received an influenza immunization OR who reported previous receipt of an influenza immunization. | Patients with CKD are at increased risk of infections, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend influenza vaccination in this group.54 | 5 | High | Safe, effective |

| Quality ID 111 CMS eCQM ID: CMS127v10 |

Pneumococcal vaccination status for older adult | Percentage of patients aged 66 yr and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine. | Patients with CKD are at increased risk of infections, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend pneumonia vaccination in this group.54 | 4 | High | Safe, effective |

| Quality ID 130 CMS eCQM ID: CMS68v11 |

Documentation of current medications in the medical record | Percentage of visits for patients aged 18 yr and older for which the eligible professional or eligible clinician attests to documenting a list of current medications using all immediate resources available on the date of the encounter. | Patients with CKD often have polypharmacy, and medication reconciliation can avoid medication errors and adverse drug events.55,56 | 7 | High | Safe, effective |

| Quality ID 236 CMS eCQM ID: CMS165v10 |

Controlling high BP | Percentage of patients aged 18–85 yr who had a diagnosis of essential hypertension starting before and continuing into or starting during the first 6 mo of the measurement period and whose most recent BP was adequately controlled (<140/90 mm Hg) during the measurement period. | Hypertension control reduces risk of cardiovascular events and mortality.57,58 | 3 | High | Effective |

| Improvement activities | ||||||

| IA_AHE_3 | Promote use of PRO tools | Demonstrate performance of activities for employing PRO tools and corresponding collection of PRO data such as the use of PHQ-2 or PHQ-9, PROMIS instruments, patient-reported wound QoL, patient-reported wound outcome, and patient-reported nutritional screening. | Patients with kidney disease have high rates of comorbid depression and often have high symptom burden and decreased QoL. | 1f | High | Patient-centered |

| IA_BE_4 | Engagement of patients through implementation of improvements in patient portal | MIPS-eligible clinicians must provide access to an enhanced patient/caregiver portal that allows users (patients or caregivers and their clinicians) to engage in bidirectional information exchange. Examples of the use of such a portal include, but are not limited to brief patient re-evaluation by messaging; communication about test results and follow-up; communication about medication adherence, side effects, and refills; BP management for a patient with hypertension; blood sugar management for a patient with diabetes; or any relevant acute or chronic disease management. | Patients with kidney disease, as well as other dynamic health conditions, may particularly benefit from patient portals which provide direct access to EHR data and facilitate patient–provider communication. | Medium | Patient-centered, timely | |

| IA_BE_6 | Regularly assess patient experience of care and follow-up on findings | Collect and follow-up on patient experience and satisfaction data. This activity also requires follow-up on findings of assessments, including the development and implementation of improvement plans. To fulfill the requirements of this activity, MIPS-eligible clinicians can use surveys (e.g., consumer assessment of health care providers and systems survey), advisory councils, or other mechanisms. MIPS-eligible clinicians may consider implementing patient surveys in multiple languages, based on the needs of their patient population. | Regular collection and application of learnings from patient surveys can help to drive meaningful improvements in delivery of kidney care. | High | Patient-centered | |

| IA_BE_14 | Engage patients and families to guide improvement in the system of care | Engage patients and families to guide improvement in the system of care by leveraging digital tools for ongoing guidance and assessments outside the encounter, including the collection and use of patient data for return to work and patient QoL improvement. Platforms and devices that collect PGHD must do so with an active feedback loop, either providing PGHD in real or near real time to the care team, or generating clinically endorsed real or near real time automated feedback to the patient, including PROs. | Use of a digital platform that allows for bidirectional information exchange can enhance patient–clinician collaboration to improve outcomes between visits. | High | Patient-centered, timely | |

| IA_BE_15 | Engagement of patients, family, and caregivers in developing a plan of care | Engage patients, family, and caregivers in developing a plan of care and prioritizing their goals for action, documented in the EHR technology. | Consideration of patient, family, and caregiver goals and preferences when developing a treatment plan is necessary to ensure patient-centered kidney care. | Medium | Patient-centered | |

| IA_BE_16 | Promote self-management in usual care | To help patients self-manage their care, incorporate culturally and linguistically tailored evidence-based techniques for promoting self-management into usual care and provide patients with tools and resources for self-management. Examples of evidence-based techniques to use in usual care include goal setting with structured follow-up, teach-back methods, action planning, assessment of need for self-management (e.g., the patient activation measure), and motivational interviewing. Examples of tools and resources to provide patients directly or through community organizations include peer-led support for self-management, condition-specific chronic disease or substance use disorder self-management programs, and self-management materials. | Patients with kidney disease come from a diversity of cultural and educational backgrounds. When tailored to an individual's language preference and literacy level, evidence-based materials for self-management can be an effective resource for enhancing patient engagement. | Medium | Effective, equitable | |

| IA_CC_2 | Implementation of improvements that contribute to more timely communication of test results | Timely communication of test results defined as timely identification of abnormal test results with timely follow-up. | Timely communication of test results is essential for reducing harm associated with abnormal results. | Medium | Timely | |

| IA_CC_13 | Practice improvements for bilateral exchange of patient information | Ensure that there is bilateral exchange of necessary patient information to guide patient care, such as open notes, that could include one or more of the following: • participate in a health information exchange if available and/or • use structured referral notes. | Patients with kidney disease may have multiple clinicians on their care team. Use of technology that allows for secure sharing of health information can improve communication between all members of the care team. | Medium | Patient-centered | |

| IA_PCMH | Electronic submission of patient-centered medical home accreditation | Attestation of PCMH or comparable specialty practice that has achieved certification from a national program, regional or state program, private payer, or other body that administers patient-centered medical home accreditation and should receive full credit for the improvement activities performance category. | The PCMH model aims to promote comprehensive, coordinated, and accessible health care through a variety of patient-centered practice improvements. | N/A | Patient-centered | |

| IA_PM_11 | Regular review practices in place on targeted patient population needs | Implement regular reviews of targeted patient population needs, such as structured clinical case reviews, which include access to reports that show unique characteristics of MIPS-eligible clinician's patient population, identification of underserved patients, and how clinical treatment needs are being tailored, if necessary, to address unique needs and what resources in the community have been identified as additional resources. The review should consider how structural inequities, such as racism, are influencing patterns of care and consider changes to acknowledge and address them. Reviews should stratify patient data by demographic characteristics and health-related social needs to appropriately identify differences among unique populations and assess the drivers of gaps and disparities and identify interventions appropriate for the needs of the subpopulations. | Patients with kidney disease are disproportionately affected by racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities and inequities. Regular review of patient population needs may help to identify underserved patients and establish interventions that increase support and reduce disparities in health outcomes. | Medium | Effective, equitable | |

| IA_PM_14 | Implementation of methodologies for improvements in longitudinal care management for high-risk patients | Provide longitudinal care management to patients at high risk for adverse health outcome or harm that could include one or more of the following: • use a consistent method to assign and adjust global risk status for all empaneled patients to allow risk stratification into actionable risk cohorts. Monitor the risk-stratification method and refine as necessary to improve accuracy of risk status identification; • use a personalized plan of care for patients at high risk for adverse health outcome or harm, integrating patient goals, values, and priorities; and/or • use on-site practice-based or shared care managers to proactively monitor and coordinate care for the highest risk cohort of patients. | Patients with kidney disease are medically complex with multiple comorbid conditions. Risk stratification using validated risk scores coupled with care coordination can reduce the risk for adverse health outcomes. | Medium | Effective | |

| IA_PM_16 | Implementation of medication management practice improvements | Manage medications to maximize efficiency, effectiveness, and safety that could include one or more of the following: • reconcile and coordinate medications and provide medication management across transitions of care settings and eligible clinicians or groups; • integrate a pharmacist into the care team; and/or • conduct periodic, structured medication reviews. | Patients with kidney disease frequently have a high medication burden. Implementation of medication management practices, including periodic medication review and reconciliation by a pharmacist or other member of the care team, may reduce the risk of adverse safety events related to medications. | Medium | Safe, effective | |

| IA_PSPA_16 | Use of decision support and standardized treatment protocols | Use decision support and standardized treatment protocols to manage workflow in the team to meet patient needs. | Use of evidence-based decision support and standardized treatment protocols helps to ensure appropriateness and consistency of patient care while simultaneously streamlining provider workflow. | Medium | Effective | |

| Cost | ||||||

| COST_AKID_1 | Acute kidney injury requiring new inpatient dialysis | The acute kidney injury requiring new inpatient dialysis episode-based cost measure evaluates a clinician's risk-adjusted cost to Medicare for patients who receive their first inpatient dialysis service for acute kidney injury during the performance period. The measure score is the clinician's risk-adjusted cost for the episode group averaged across all episodes attributed to the clinician. This procedural measure includes costs of services that are clinically related to the attributed clinician's role in managing care during each episode from the clinical event that opens, or triggers, the episode through 30 d after the trigger. | Managing transitions of care after acute kidney injury requiring dialysis can reduce preventable health care spending. | — | N/A | Efficient |

| TPCC_1 | TPCC | The TPCC measure assesses the overall cost of care delivered to a patient with a focus on the primary care they receive from their provider(s). The measure is payment-standardized, risk-adjusted, and specialty-adjusted. | Delivering high-quality care for patients with kidney disease can address unmet medical needs and reduce preventable health care spending. | 1 | N/A | Efficient |

MVP, MIPS Value Pathway; ASN, American Society of Nephrology; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; IOM, Institute of Medicine; NQF, National Quality Forum; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; eCQM, electronic clinical quality measure; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PHQ-2, Patient Health Questionnaire-2; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QoL, quality of life; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System; EHR, electronic health record; PGHD, patient-generated health data; PCMH, patient-centered medical home; N/A, not applicable; TPCC, total per capita cost.

Quality measures were rated in Mendu ML, Tummalapalli SL, Lentine KL, et al. Measuring quality in kidney care: an evaluation of existing quality metrics and approach to facilitating improvements in care delivery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(3):602–614.

Improvement activities weighting from CMS from https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures.

Added by CMS.

— – not ranked or rated.

Submitted to MUC in May 2021.

Improvement activity ranking within subcategory.

Among 17 committee members, there were 15 (88%) respondents (SLT, SAS, YB, KFE, PSG, EG, NG, KLL, SQL, FL, SM, MS, DEW, SDB, MLM). The three highest ranked quality measures were ACEi/ARB Therapy, Optimal ESRD Starts, and Controlling High BP.29 Optimal ESRD Starts measures the percentage of patients with incident ESKD who receive a preemptive kidney transplant, initiate home dialysis, or initiate outpatient in-center hemodialysis using an arteriovenous fistula or graft. The highest ranked improvement activities measures in each subcategory were (1) implementation of methodologies for improvements in longitudinal care management for high-risk patients; (2) care coordination agreements that promote improvements in patient tracking across settings; (3) use of tools to assist patient self-management; and (4) promote use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) tools. Among cost measures, TPCCs were ranked ahead of Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary.

MVP Candidate Submission to CMS

Informed by committee rankings and MVP guiding principles, the initial nephrology MVP candidate was submitted to CMS in February 2021 using the CMS MVP Submission Template (Supplemental Exhibit 3). Several videoconference meetings were convened between the ASN Quality Committee and CMS MVP Development Team to discuss the relative merits of each measure. CMS recommended the addition of three quality, three improvement activities, and the Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis cost measure (Supplemental Exhibit 4). Two of the proposed quality measures, ACEi/ARB Therapy and Optimal ESRD Starts, were not currently approved for use in the MIPS program. ACEi/ARB Therapy is a Qualified Clinical Data Registry measure stewarded by the Renal Physicians Association, and Optimal ESRD Starts is stewarded by the Permanente Federation and used by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) in the Kidney Care Choices program, relevant to the goal of MVPs to promote alignment with advanced APMs.7,30,31

Measures under Consideration Process

Because the ASN Quality Committee ranked ACEi/ARB Therapy and Optimal ESRD Starts as highly important for CKD care, we worked with Renal Physicians Association and the Permanente Federation to submit these through the Measures Under Consideration (MUC) process in May 2021.32 This process allows for new measures to be considered for inclusion in traditional MIPS, MVPs, and other Medicare programs through federal rulemaking. Information about measure specifications, validity and reliability testing, and National Quality Forum endorsement was submitted through the CMS MUC Entry/Review Information Tool. In parallel, the National Quality Forum evaluated measures through the Measure Applications Partnership. The measure stewards and an ASN Quality Committee representative attended multiple videoconference meetings held by the National Quality Forum to vet these new measures. ACEi/ARB Therapy was accepted as a new measure within MIPS and the nephrology MVP.

Public Comments

The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP was published in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule in July 2022 (Supplemental Exhibit 5).33 CMS solicited feedback on the MVP from nephrology professional societies and other kidney stakeholders. Public comments were submitted to CMS through the regulations.gov website.34 Among 23,171 public comments in total, 35 contained the search term “optimal care for kidney health.” One author (SLT) reviewed the 35 comments and identified 13 that substantively discussed the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP. Text relevant to the MVP was extracted and circulated to three authors (SLT, SAS, MLM) who performed a topical survey of these qualitative comments, as described by Sandelowski and Barroso, to better understand stakeholder perspectives on the MVP.35 The three authors (SLT, SAS, MLM) met as a group and indexed content into three predetermined categories based on the valence of comments (supportive, conditionally supportive, not supportive of the MVP). Recommendations to add or remove specific quality measures were abstracted from the comments. We then inductively coded (labeled) concepts appearing in extracted comments and iteratively identified topics and subtopics describing stakeholder perspectives.35,36 An illustrative quotation was selected for each subtopic.

Results

Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP

The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP was published in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule in November 2022 (Supplemental Exhibit 6).37 The MVP includes eight quality measures, 13 improvement activities measures, two cost measures specific to nephrology, as well as the two population health and 16 promoting interoperability measures consistent across all MVPs (Table 1). Reporting on the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP will be optional in 2023 and may become mandatory after 2026. Nephrologists not exempt from MIPS may continue to report in traditional MIPS, an MVP, or as part of an MIPS APM (e.g., Medicare Shared Savings Program). Nephrology clinicians who elect to participate in the MVP will choose four (of 8) quality measures to report. For improvement activities, clinicians will choose two medium-weighted or one high-weighted measure to report in the MVP, or they can attest that they are part of a patient-centered medical home. Clinicians will choose one population health measure and report on the same promoting interoperability measures as in traditional MIPS (Supplemental Table 2). Both cost measures will be calculated for nephrology clinicians participating in the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP.

Quality measures in the MVP promote the use of evidence-based therapies (ACEi/ARB), chronic disease management (diabetes and BP control), vaccinations, medication reconciliation, and advance care planning (Table 1). Improvement activities measures in the MVP promote the use of PRO measures, patient engagement strategies (e.g., patient portals), assessing patient experience, population health management, and decision support. Cost measures include the Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis, which assesses spending during a 30-day acute kidney injury requiring dialysis episode of care.38 The MVP also includes the TPCC measure which captures Medicare Part A and Part B spending attributed to the patient's primary nephrologist.39

Public Comments

Public commenters included nephrology professional organizations, other specialty societies, pharmaceutical companies, health insurance representatives, and other key stakeholders. Overall, public comments were supportive of the MVP and emphasized the need to develop more kidney-specific measures. Measures should prioritize prevention and evidence-based treatments that can be applied across a range of medical specialties to enhance delivery of kidney care. Among the 13 comments discussing the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP, eight were supportive, two conditionally supportive, and three did not indicate whether they were supportive or not supportive of the MVP. Three commenters recommended adding the Kidney Health Evaluation Measure to incentivize annual eGFR and urine albumin/creatinine ratio monitoring among patients with diabetes. One commenter recommended adding the Chronic Care and Preventive Care Management for Empaneled Patients Improvement Activity, and another commenter recommended removing the Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Practitioner Level Long-term Catheter Rate measure.

Seven topics were identified from stakeholder comments: (1) patient-centeredness, (2) early CKD detection and management, (3) multidisciplinary care, (4) limitations of cost measures, (5) alignment with evidence-based guidelines, (6) alignment of measure sets, and (7) new measure development (Table 2). Commenters described the MVP as patient-centered, suggesting further ways to increase patient input and include more PRO performance measures in CMS programs. Stakeholders described the MVP as concordant with existing guidelines. In addition, there were recommendations for greater emphasis on early CKD detection and management by including kidney measures in primary care–focused MVPs and promoting interventions to delay CKD progression. Given the overlapping pathophysiology and multimorbidity of CKD with other conditions, commenters called for collaboration with cardiologists and endocrinologists. One commenter raised concerns about attributing the cost measures to nephrologists when there are a multitude of clinicians involved in patient care. Three commenters emphasized the importance of measure alignment across CMS programs and other payers. Commenters called for new measure development, highlighting the limited number of measures directly related to nephrology in MIPS.

Table 2.

Topical survey of public comments related to the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP

| Topic | Subtopic | Example Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-centeredness | Patient input into measure development | “We recommend that CMS explore ways to include more patient-centered measures in the MVPs such as those vetted by the CQMC with consumer input, measures of patient outcomes, patient-reported measures, as well as new approaches to the evaluation of patient experience.” |

| Patient-reported measures | “…we encourage CMS to explore ways to improve measurement of patient experience as well as to include additional patient-reported outcomes-based performance measures (PRO-PM) in both the ESRD QIP and the Merit-Based Payment System (MIPS)…” | |

| Patient education | “KDE [Kidney Disease Education] should be included in MIPS as an MVP or part of an MVP…incentivizing KDE usage is key to ensuring that patients receive the information they need to make informed decisions about dialysis modalities. Further, we know that patients who are educated earlier in the diagnosis process tend to have a smoother transition to dialysis care, as opposed to a “crash start” in the emergency room. In order to increase KDE usage, we suggest that CMS consider incentivizing utilization of the KDE benefit through MIPS, perhaps through an MVP.” | |

| Early CKD detection and management | Collaboration with primary care | “Future consideration may also include a new MVP that focuses on early detection and delayed progression of CKD as this MVP would reinforce this important role of…primary care clinicians…” |

| Screening | “…CMS reconsider the addition of the Kidney Health Evaluation quality measure to the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP and a more appropriate, primary care–focused MVP. Guidelines support annual screening for high-risk populations, including those with chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes. Including this measure in an MVP such as Optimizing Chronic Disease Management and a primary care–focused MVP would help promote this critical care process.” | |

| Interventions to delay progression | “…chronic kidney disease is a progressive disease where early identification and timely initiation of treatment, lifestyle modifications, and management of chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes control can slow disease progression.” | |

| Multidisciplinary care | Collaboration with specialty physicians | “…important role of both primary care clinicians and other specialist types including cardiologists and endocrinologists.” |

| Overlapping pathophysiology | “Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular complications are often the cause of death in patients with CKD. Optimizing care for kidney disease patients through this MVP has the potential to not only improve CKD outcomes, but may also improve the cardiovascular risk and outcomes for these patients.” | |

| Interprofessional collaboration | “Genetic factors are increasingly recognized as contributors to chronic kidney disease (CKD) risk, necessitating better access to genetic counseling and testing to detect risk or diagnosis earlier…The genetic counseling IA would improve referrals to genetic counselors for evidence-based services....” | |

| Limitations of cost measures | Attribution | “…concerned that the cost measures – Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis and Total Per Capita Cost – hold the nephrologist responsible when there are a multitude of providers involved in patient care...Patients requiring dialysis for AKI usually have multiple medical problems and complications, and multiple providers and consultants. For the vast majority of patients, the management of AKI accounts for only a small fraction of the inpatient cost of care. It is rare that the nephrologist has any substantial control over the total cost…. |

| Advance methods to measure value | “We also recommend CMS leverage the implementation of the MVPs to advance how value is measured…recommends consideration be given to cost measures that go beyond assessing whether there is waste in the system and that seek to promote clinically appropriate utilization of health care services…” | |

| Alignment with evidence-based guidelines | Guideline-concordant | “The proposed measures are consistent with recommendations of KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention…” |

| Alignment of measure sets | Alignment across CMS programs | “The current proposal to retain the standalone pneumococcal and flu measures for the Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP, and the standalone flu measure for the Advancing Rheumatology Patient Care MVP, is not consistent with CMS’ goal to promote alignment across measure sets.” |

| Alignment across payers | “We appreciate the continued alignment between the quality measures included in MVPs and the specialty core measure sets established by the Core Quality Measures Collaborative (CQMC)…” | |

| New measure development | Lack of nephrology quality measures | “…there are currently only a handful of measures directly related to nephrology in the MIPS measure set.” |

| New measures for pharmacologic management | “…we believe this measure set would be strengthened by the development and inclusion of a measure aimed at broader optimization of pharmacologic management targeting delayed progression of kidney disease” | |

| New measures for early CKD | “Key measure gaps that would better support the development of a more robust measure set include those related to screening, guideline-based diagnosis and evaluation practices and ongoing evaluation to delay disease progression.” |

CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Discussion

This article details the systematic voting and consensus-building process, whereby the ASN Quality Committee codesigned new nephrology regulatory policy in collaboration with CMS. The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP simplifies measure selection in MIPS to reduce administrative burden, ensures measures are more relevant to kidney care delivery, and facilitates meaningful comparisons across nephrology clinicians. Other strengths of the MVP include incorporating the six Institute of Medicine quality domains and six highly valid quality measures.

Our process serves as a case study of collaborative policymaking between nephrology professional organizations and regulatory agencies. Stakeholders frequently encounter poorly designed health care policy that is challenging to implement into practice. Feedback from clinician stakeholders to regulatory agencies is typically reactive rather than proactive. When stakeholders engage in collaborative policymaking with regulatory agencies, policy design and policy implementation may both improve.40,41 Other examples of collaborative policymaking in health care include the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee, collaboration between nephrology professional societies and CMS on Kidney Care Choices, and similar efforts to ours to construct an MVP for emergency medicine and other specialties.42,43

We encountered several challenges during MVP development. Our primary challenge is the lack of quality measures that capture aspects of CKD care, with no established and tested performance measures related to other agents to slow kidney disease progression such as sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, drugs with cardiovascular benefits such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, anemia management, mineral bone disease, kidney disease education, transplant referral, access planning, or CKD-related quality of life. A second challenge is that CMS retains authority on which measures to include or not include in the MVP. While ASN Quality Committee members provided subject matter knowledge on which measures were relevant to nephrology care, at times ASN and CMS had differing opinions on which measures should be included. Lastly and notably, the MVP development process was administratively complex, and the MUC process, which entails a 2-year process from submission to final rule announcement, caused substantial delays.44

The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP has several limitations. First, Optimal ESRD Starts remains an unapproved measure within MIPS (despite being a key measure in the CMMI Kidney Care Choices model), thus preventing its inclusion in the MVP. Optimal ESRD Starts will be submitted to CMS's MUC with the goal of including it in future years. Because facilitating advanced APM participation represents a stated goal of MVPs, CMS should ensure alignment with CMMI and accept CMMI measures into MIPS using an accelerated process. Second, unlike CMMI models, our MVP does not contain transplant-related measures to address the critical priority of early transplant referral and transplant access. Third, a major limitation was the lack of involvement from patients and other kidney community stakeholders (such as interdisciplinary care team members) in the MVP development. Public comments, patient engagement, and continued iteration of the MVP will be essential for its successful implementation. For example, submitting a PRO measure based on patient feedback should be prioritized in future iterations. Fourth, MVPs will be challenging to evaluate because of voluntary participation, lack of prespecified defined control groups, and therefore, confounding factors, so it may be unclear whether MVPs lead to any improvement over the current MIPS program. Mixed-method evaluations will prove valuable to assess nephrologist perceptions of this MVP and its effect on reporting burden. Dissemination of and education about the MVP will also be critical to encourage participation. There may be barriers to adoption if nephrologists continue to use traditional MIPS measures because of familiarity, prior investment in electronic health record functionality to facilitate traditional MIPS reporting, and established workflows to optimize performance on previously selected measures. It will be critical for CMS to support nephrology clinicians in small or rural practices, as well as those who care for disadvantaged patients, who score worse in traditional MIPS and may face greater challenges transitioning to MVPs.13,45 Finally, we did not incorporate measures designed to improve health equity in this version of the MVP, such as social needs screening measures. Given CMS's focus on alleviating racial and economic disparities in care delivery, we would advocate for equity-related measures in future iterations of the MVP.

Conclusions

The Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP represents a kidney care–specific quality, cost, and care delivery improvement measure set, which offers the opportunity to address gaps in CKD care at a national scale. The MVP represents an improvement over traditional MIPS by making it easier for nephrology clinicians to choose measures relevant to kidney care. The MVP financially incentivizes nephrology clinicians to increase the use of evidence-based therapies and improve chronic disease management with the goal of improving clinical outcomes for patients with kidney disease. MVPs require clinicians to report fewer measures than traditional MIPS, thereby reducing administrative burden.

The MVP creation involved the collaboration of ASN's Quality Committee with CMS, who has forecasted that the entire MIPS program will transition to MVPs. Future iteration is needed to ensure inclusion of newer measures reflective of emerging evidence, patient feedback, and health equity. Monitoring and evaluation will be crucial to assess the effect of the MVP on quality of care, costs, and administrative burden. The nephrology community must continue to take an active role in policymaking to ensure that P4P and other regulatory programs are optimized to improve kidney care delivery.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures

S.D. Bieber reports employer: Kootenai Health. During manuscript content development and revision, Dr. Y. Brahmbhatt has been employed by AstraZeneca and holds AstraZeneca stocks. Voting and review of measures by Dr. Y. Brahmbhatt was completed while employed at the Division of Nephrology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA. P.S. Garimella receives speaker fees from Otsuka Inc. and honoraria from Dialysis Clinic Inc. unrelated to the submitted work. E. Gould reports consultancy: Premier Inc.; ownership interest: Apple, Microsoft; research funding: Allena, AstraZeneca, Oxthera, Palladio; and advisory or leadership role: ASN Home Dialysis Steering Committee. Dr. N. Gupta serves on an advisory board of Fresenius Medical Care and received royalties from UpToDate. Dr. K.L. Lentine is a Senior Scientist of the SRTR, receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK120551 | R01DK120518), and is supported by the Mid-America Transplant/Jane A. Beckman Endowed Chair in Transplantation; Dr. K.L. Lentine is chair of the American Society of Transplantation Living Donor Community of Practice, a member of the ASN policy and Advocacy Committee, and a member of the NKF Transplant Advisory Committee; unrelated to this work, Dr. K.L. Lentine receives consulting fees from CareDx and speaker honoraria from Sanofi. S.Q. Lew receives consultation fee from Triomed. S.Q. Lew reports employer: George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates and Mitre; consultancy: Triomed; advisory or leadership role: Quality Insights: Medical Review Board, George Washington University: ACO Board of Director; and other interests or relationships: ASN: KHI member, ASN: Quality Committee member, ASN: KidneyX grant reviewer, ASN: COVID-19 home dialysis subcommittee, NIA: grant reviewer, NIH's Kidney Precision Medical Project: Data Safety Monitoring Board member, USFDA Gastroenterology and Urology Devices Panel of FDA's Medical Devices Advisory Committee. F. Liu reports consulting from Outset Medical, medical advisor to CVS/Accordant, and speakers bureau for AstraZeneca. F. Liu reports employer: the Rogosin Institute; consultancy: CVS/Accordant, Outset Medical; Speakers Bureau: AstraZeneca; and other interests or relationships: Outset Medical (PI for clinical study), CVS (PI for clinical study). M.L. Mendu reports advisory or leadership role: advisory board of New England Life Care. S. Mohan receives research funding from the NIH and the Kidney Transplant Collaborative, is a consultant for HSAG, chair of the CMS/HRSA ESRD Treatment Choices Collaborative, and Deputy Editor for Kidney International Reports. S. Mohan reports consultancy: eGenesis, HSAG; patents or royalties: Columbia University; advisory or leadership role: Deputy Editor of Kidney International Reports (ISN), Chair of UNOS, Data advisory committee, Member of SRTR Review Committee, Member of ASN Quality committee, National Faculty Chair ETCLC; and other interests or relationships: Research Funding from NIH (NIDDK, NIHMD, and NIBIB) and Kidney Transplant Collaborative. M. Somers reports consultancy: Alnylam, Dicerna, Horizon, Orfan Biotech, Precision Biosciences; research funding: BioPorto, Dicerna; and advisory or leadership role: NAPRTCS—Board of Directors and ASPN—President and Past President. S.L. Tummalapalli reports research funding: Scanwell Health and other interests or relationships: travel support through the Abbott Pharmaceuticals and International Society of Nephrology. D.E. Weiner reports research funding, all compensation paid to Tufts MC from Bayer (site PI), Cara (site PI), Vertex (site PI); advisory or leadership role: Co-Editor-in-Chief of NKF Primer on Kidney Diseases 8th Edition, Editor-in-Chief, Kidney Medicine, Medical Director of Clinical Research, Dialysis Clinic Inc., Member of ASN Quality and Policy Committees and ASN representative to KCP, Member of Scientific Advisory Board for National Kidney Foundation; and other interests or relationships: Member of Safety and Clinical Events Committee for “A Prospective, Multi-Center, Open-Label Assessment of Efficacy and Safety of Quanta SC+ for Home Hemodialysis” Trial (Avania CRO) and Member of Adjudications Committee of ProKidney REACT Trial (George Institute CRO). Mr. D.L. White is employed by the American Society of Nephrology. K. Erickson reports Consultancy: Acumen LLC, Boehringer Ingelheim; Honoraria: Dialysis Clinic, Inc., University of Missouri, Satellite Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, UC Irvine, Columbia University; Advisory or Leadership Role: AJKD - associate editor, CJASN - associate editor, American Society of Nephrology Public Policy Board's Quality Committee (member), Seminars in Dialysis - associate editor; and Other Interests or Relationships: research funding from Health Care Service Corporation's Affordability Cures grant, and travel funds from KDIGO. N. Gupta reports Consultancy: Fresenius Medical Care advisory board; Research Funding: Quanta; Patents or Royalties: UpToDate; Speakers Bureau: Baxters Speaker Bureau; and Other Interests or Relationships: Member of the ASN Quality Committee, and Member of ASN EPC, TDAT. K. Lentine reports Consultancy: CareDx, Inc.; Ownership Interest: CareDx, Inc.; and Speakers Bureau: Sanofi. E. Gould reports Consultancy: Premier Inc.; Ownership Interest: Apple, Microsoft; Research Funding: Oxthera, Astra Zeneca, Allena; Palladio; and Advisory or Leadership Role: ASN Home Dialysis Steering Committee. M. Somers reports Consultancy: Horizon, Alnylam, Dicerna, Orfan Biotech, Precision Biosciences; Research Funding: BioPorto, Dicerna; and Advisory or Leadership Role: NAPRTCS Board of Directors, ASPN President and Past President. S. Mohan reports Consultancy: eGenesis, HSAG; Patents or Royalties: Columbia University; Advisory or Leadership Role: Deputy Editor of Kidney International Reports (ISN), Chair of UNOS Data advisory committee, Member of SRTR Review Committee, Member of ASN Quality committee, National Faculty Chair of ETCLC; and Other Interests and Relationships: Research Funding from NIH (NIDDK, NIHMD and NIBIB), and Kidney Transplant Collaborative. Y. Brahmbhatt reports Employer: Astrazeneca, Chinook Therapeutics; Ownership Interest: Astrazeneca, Chinook Therapeutics; and Advisory or Leadership Role: Served on advisory boards as part of job function at Astrazeneca (not paid additionally for this). Y. Brahmbhatt reports Employer: Astrazeneca, Chinook Therapeutics; Ownership Interest: Astrazeneca, Chinook Therapeutics; and Advisory or Leadership Role: Served on advisory boards at Astrazeneca (unpaid). S. Mohan reports Consultancy: eGenesis, HSAG; Patents or Royalties: Columbia University; Advisory or Leadership Role: Deputy Editor Kidney International Reports (ISN), Chair UNOS, Data advisory committee, Member of SRTR Review Committee, Member of ASN Quality committee, National Faculty Chair ETCLC; and Other Interests or Relationships: Research Funding from NIH (NIDDK, NIHMD and NIBIB) and Kidney Transplant Collaborative. E. Gould reports Consultancy: Premier Inc.; Ownership Interest: Apple, Microsoft; Research Funding: Oxthera, Astra Zeneca, Allena, Palladio; and Advisory or Leadership Role: ASN Home Dialysis Steering Committee. K. Lentine reports Consultancy: CareDx, Inc.; Ownership Interest: CareDx, Inc.; and Speakers Bureau: Sanofi. K. Erickson reports Consultancy: Acumen LLC; Boehringer Ingelheim; Honoraria: Dialysis Clinic, Inc.; University of Missouri; Satellite Healthcare; Boehringer Ingelheim; UC Irvine; Columbia University; Advisory or Leadership Role: AJKD - associate editor; CJASN - associate editor; American Society of Nephrology, Public Policy Board's Quality Committee (member); Seminars in Dialysis - associate editor.; and Other Interests or Relationships: Receive research funding from Health Care Service Corporation's Affordability Cures grant, Received travel funds from KDIGO. N. Gupta reports Consultancy: Fresenius Medical Care advisory board; Research Funding: Quanta; Patents or Royalties: UpToDate; Speakers Bureau: Baxters Speaker Bureau; and Other Interests or Relationships: Member, ASN Quality Committee, Member ASN EPC, TDAT. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. S.L. Tummalapalli is supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS028684).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Catherine R. Butler for her methodological expertise. We also acknowledge all the members of the American Society of Nephrology Quality Committee for their policy and quality expertise.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mallika L. Mendu, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, David L. White.

Data curation: Scott D. Bieber, Yasmin Brahmbhatt, Kevin F. Erickson, Pranav S. Garimella, Edward Gould, Nupur Gupta, Krista L. Lentine, Susie Q. Lew, Frank Liu, Mallika L. Mendu, Sumit Mohan, Michael Somers, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, Daniel E. Weiner.

Formal analysis: Mallika L. Mendu, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Funding acquisition: Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Methodology: Mallika L. Mendu, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Project administration: Amy Beckrich, Mallika L. Mendu, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, David L. White.

Resources: Scott D. Bieber, Mallika L. Mendu, David L. White.

Supervision: Scott D. Bieber, Mallika L. Mendu, Daniel E. Weiner.

Validation: Sarah A. Struthers, Daniel E. Weiner.

Writing – original draft: Mallika L. Mendu, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Writing – review & editing: Amy Beckrich, Scott D. Bieber, Yasmin Brahmbhatt, Kevin F. Erickson, Pranav S. Garimella, Edward Gould, Nupur Gupta, Krista L. Lentine, Susie Q. Lew, Frank Liu, Mallika L. Mendu, Sumit Mohan, Michael Somers, Sarah A. Struthers, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, Daniel E. Weiner, David L. White.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/E466.

Supplemental Exhibit 1. MVP guiding principles reproduced from CMS.

Supplemental Exhibit 2. MIPS versus MVP structure reproduced from CMS.

Supplemental Table 1. Ranked-choice voting results.

Supplemental Exhibit 3. Initial nephrology MVP submission to CMS (February 2021).

Supplemental Exhibit 4. CMS feedback on MVP submission (February 2021).

Supplemental Exhibit 5. Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule (July 2022).

Supplemental Exhibit 6. Optimal Care for Kidney Health MVP in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule (November 2022).

Supplemental Table 2. Population Health and Promoting Interoperability Measures in the MVP foundational layer.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Making the Money Follow the Consensus in Nephrology Payment Reform,” on pages 1297–1299.

References

- 1.Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eijkenaar F, Emmert M, Scheppach M, Schöffski O. Effects of pay for performance in health care: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Policy 2013;110(2-3):115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendelson A Kondo K Damberg C, . The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341–353. doi: 10.7326/m16-1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin E, MaCurdy T, Bhattacharya J. The Medicare access and CHIP reauthorization act: implications for nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(9):2590–2596. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017040407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riaz S, Erickson KF. Early nephrologist performance in the merit-based incentive payment system: both reassurance and reason for concern. Kidney Med. 2021;3(5):699–701. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quality Payment Program. Explore Measures & Activities. Accessed August 6, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures?tab=qualityMeasures&py=2022 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Kidney Care Choices Model. Accessed August 7, 2022. https://innovation.cms.gov/media/document/kcc-py23-rfa [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quality Payment Program Resource Library. Quality Payment Program Experience Report; 2019. Accessed August 6, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/resource-library [Google Scholar]

- 9.System USRD. 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2021. https://adr.usrds.org/2021 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy DP, Drawz PE, Foley RN. Trends in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use among those with impaired kidney function in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(7):1314–1321. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018100971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CD Powe NR McCulloch CE, . Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use among hypertensive US adults with albuminuria. Hypertension. 2021;77(1):94–102. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.16281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan R, Akbari A, Brown PA, Hiremath S, Brimble KS, Molnar AO. Risk factors for unplanned dialysis initiation: a systematic review of the literature. Can J kidney Health Dis. 2019;6:205435811983168. doi: 10.1177/2054358119831684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tummalapalli SL Mendu ML Struthers SA, et al. Nephrologist performance in the merit-based incentive payment system. Kidney Med. 2021;3(5):816–826.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardach NS Wang JJ De Leon SF, . Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1051–1059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen LA Simpson K Pietz K, et al. Effects of individual physician-level and practice-level financial incentives on hypertension care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1042–1050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad DA, Perry L. Quality-based financial incentives in health care: can we improve quality by paying for it? Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):357–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogundeji YK, Sheldon TA, Maynard A. A reporting framework for describing and a typology for categorizing and analyzing the designs of health care pay for performance schemes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3479-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eijkenaar F. Key issues in the design of pay for performance programs. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(1):117–131. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0347-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khullar D, Bond AM, Qian Y, O’Donnell E, Gans DN, Casalino LP. Physician practice leaders’ perceptions of Medicare’s merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(12):3752–3758. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06758-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khullar D, Bond AM, O’Donnell EM, Qian Y, Gans DN, Casalino LP. Time and financial costs for physician practices to participate in the Medicare merit-based incentive payment system: a qualitative study. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(5):e210527. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanafelt TD Dyrbye LN Sinsky C, . Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crosson F, Bloniarz K, Glass D, Mathews J. MedPAC’s Urgent Recommendation: Eliminate MIPS, Take a Different Direction. Health Affairs Blog; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). Accessed November 1, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/mips-value-pathways [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crum E. Clinicians and payers expect to wait and see before embracing CMS MIPS value pathways. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(6 Spec No.):SP245–SP246. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2021.88735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Meaningful Measures 2.0: Moving from Measure Reduction to Modernization. Accessed August 6, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/meaningful-measures-framework/meaningful-measures-20-moving-measure-reduction-modernization#. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendu ML Tummalapalli SL Lentine KL, et al. Measuring quality in kidney care: an evaluation of existing quality metrics and approach to facilitating improvements in care delivery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(3):602–614. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019090869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLean CH, Kerr EA, Qaseem A. Time out—charting a path for improving performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1757–1761. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1802595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001. doi: 10.17226/10027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Quality Forum Quality Positioning System (QPS) Tool. Accessed August 7, 2022. https://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Quality Forum. Quality Positioning System. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor or Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) Therapy STEWARD: Renal Physicians Association. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://bit.ly/3U0hNqQ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain G, Weiner DE. Value-based care in nephrology: the kidney care choices model and other reforms. Kidney360. 2021;2(10):1677–1683. doi: 10.34067/KID.0004552021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pre-Rulemaking and Measures Under Consideration 2022 Frequently Asked Questions. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/pre-rulemaking-faq-2022-march-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CY 2023 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies Federal Register. Document Citation: 87 FR 45860. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/07/29/2022-14562/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2023-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Calendar Year 2023 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies, Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements, etc. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.regulations.gov/document/CMS-2022-0113-1871 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):905–923. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CY 2023 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies. Federal Register. Document Citation: 87 FR 69404. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/11/18/2022-23873/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2023-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis Measure Measure Information Form 2022 Performance Period. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/cost_specifications/2021-12-13-mif-ebcm-aki-new-hd.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): Total Per Capita Cost (TPCC) measure Information Form 2022 Performance Period. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/cost_specifications/2021-12-13-mif-tpcc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ansell C, Sørensen E, Torfing J. Improving policy implementation through collaborative policymaking. Policy Polit. 2017;45(3):467–486. doi: 10.1332/030557317x14972799760260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frankowski A. Collaborative governance as a policy strategy in healthcare. J Health Organ Manag. 2019;33(7/8):791–808. doi: 10.1108/jhom-10-2018-0313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gettel CJ Tinloy B Nedza SM, . The future of value-based emergency care: development of an emergency medicine MIPS value pathway framework. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022;3(2):e12672. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quality Payment Program. Explore MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). Accessed August 6, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-mips-value-pathways [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. A Day in the Life of a CMS Quality Measure. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.izsummitpartners.org/content/uploads/2018/07/QPMWG-CMS-QualityMeasures-2017-6-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khullar D, Schpero WL, Bond AM, Qian Y, Casalino LP. Association between patient social risk and physician performance scores in the first year of the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. JAMA. 2020;324(10):975–983. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong MG Perkovic V Chalmers J, . Long-term benefits of intensive glucose control for preventing end-stage kidney disease: advance-on. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(5):694–700. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in US adults, 1999–2018. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2219–2228. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa2032271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossing P Caramori ML Chan JC, . KDIGO 2022 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5):S1–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ravani P Palmer SC Oliver MJ, et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):465–473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brenner BM Cooper ME De Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–869. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa011161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie X Liu Y Perkovic V, et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(5):728–741. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ladin K Neckermann I D’Arcangelo N, et al. Advance care planning in older adults with CKD: patient, care partner, and clinician perspectives. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(6):1527–1535. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020091298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krueger KM, Ison MG, Ghossein C. Practical guide to vaccination in all stages of CKD, including patients treated by dialysis or kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):417–425. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall RK Blumenthal JB Doerfler RM, . Risk of potentially inappropriate medications in adults with CKD: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(6):837–845.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sommer J, Seeling A, Rupprecht H. Adverse drug events in patients with chronic kidney disease associated with multiple drug interactions and polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(5):359–372. doi: 10.1007/s40266-020-00747-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1511939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheung AK Chang TI Cushman WC, . KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2021;99(3):S1–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]