ChatGPT, a general purpose chatbot developed by OpenAI, has been widely reported to have the potential to revolutionize how people interact with information online.1 Like other large language models (LLMs), ChatGPT has been trained on a large text corpus to predict probable words from the surrounding context. ChatGPT, however, has received substantial popular attention for generating human-like conversational responses, and new developments are occurring rapidly. The initial release in November 2022 used the model generative pretrained transformers (GPT)-3.5, and a version based on GPT-4.0 was released in March 2023. Recent work has discussed applications of ChatGPT for medical education and clinical decision support.2–4 However, health care professionals should be aware of the drawbacks and limitations—and potential capabilities—of using ChatGPT and similar LLMs to interact with medical knowledge.

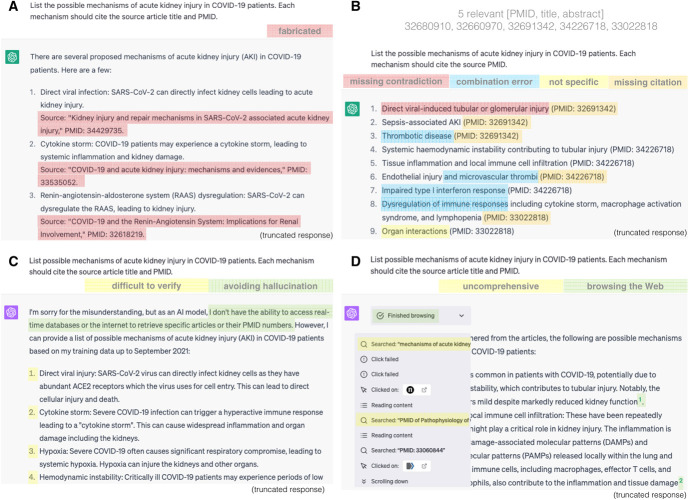

A significant issue with ChatGPT is its tendency to generate confident-sounding but fabricated responses, commonly known as “hallucination.” Although it can generate plausible-sounding text, ChatGPT does not consult any source of truth.1 Occasional incorrect or biased responses are, therefore, inevitable, and ChatGPT cannot faithfully cite sources to allow their evidence to be verified. For example, we prompted GPT-3.5–based ChatGPT to list possible mechanisms of AKI in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with references. ChatGPT produced a list of plausible mechanisms, each of which has been investigated in the literature (Figure 1A) but supported its claims with fabricated titles and irrelevant PubMed identifiers. ChatGPT using the GPT-4 model acknowledges that it cannot produce references and refuses to cite articles in the answer (Figure 1C)—a significant improvement—but leaves the difficult task of verification to the user. Consulting ChatGPT directly for medical information carries a significant risk of drawing incorrect conclusions, particularly for patients.

Figure 1.

Seeking information related to COVID-19 from ChatGPT. (A) ChatGPT-3.5 fabricates the references for its claims. (B) When prompted with the title and abstract of relevant articles, ChatGPT-3.5 can summarize the aspects requested, including some valid in-line references. However, many details are inaccurate: Related mechanisms are not correctly grouped, contradicting evidence is not mentioned, some citations are missing, and a listed mechanism is not specific. Note that the complete response mentioned only three of five articles. (C) ChatGPT-4 acknowledges its drawback and refuses to cite source articles in the response, which makes the verification more difficult. (D) ChatGPT-4 with the web browsing plug-in summarizes information from the search engine, but it only finds two relevant articles and fails to systematically answer the question. Responses were collected from GPT-3.5–based ChatGPT on March 14, 2023, and GPT-4–based ChatGPT on May 15, 2023.

However, LLMs such as ChatGPT may be better suited for text summarization than directly answering medical questions. Pilot studies have shown that LLMs can be effective at clinical reasoning, reading comprehension, and generating fluent summaries with high fidelity.5–7 Augmenting LLMs such as ChatGPT with a traditional literature search engine may therefore help address hallucination and enable the system to provide the user with comprehensive high-level summaries. For example, the new Bing provides ChatGPT-like interactive agents to help users create effective queries, identify relevant results, and summarize their content. In addition, ChatGPT recently introduced a plug-in that allows the model to search the web when generating responses (currently in limited beta test). Incorporating such features into medical literature search has the potential to streamline gathering and synthesizing evidence from the literature, improving patient care.

Unfortunately, summaries generated by current LLMs such as ChatGPT also contain inaccuracies,8 in addition to practical issues such as limitations on the length of input text. To illustrate these problems, we prompted ChatGPT (model 3.5) to identify possible mechanisms of AKI in patients with COVID-19, using five manually chosen articles on the pathophysiology of AKI in COVID-19. Although ChatGPT’s summary (Figure 1B) generally reflects the mechanisms of AKI discussed by the articles, the response lists symptoms from only three of the five input studies and misses some important mechanisms mentioned repeatedly, such as hypoxia. Moreover, some citations are missing, contradicting evidence is not mentioned, similar mechanisms are not correctly grouped, and one of the mechanisms listed is less specific than the source. We also prompted ChatGPT (model 4), with the web browsing plug-in, to answer the same question (Figure 1D). In this case, ChatGPT provides summaries with relevant citations. However, the response is based on only two articles, without synthesizing the evidence, and thus fails to answer the question systematically. Generally speaking, retrieval-augmented LLMs reduces users' control over sources, leading to results that may not align with the user's criteria for the best information (e.g., most up-to-date). Summaries generated by LLMs can miss important ideas discussed by the input sources or contain assertions unsupported by the input sources. Because imprecise or incomplete information can lead to incorrect clinical decisions and patient harm, content generated by current LLMs, including ChatGPT, must be verified for accuracy and completeness before use. Further research on the faithfulness of LLM-generated summaries and automatic verification tools is also warranted to realize the full potential of LLMs to streamline evidence gathering and synthesis from the medical literature.

Despite these limitations, the remarkable progress in AI and the rapid advancements in LLMs may have profound implications for medicine, from assisting medical education,2 to accelerating literature screening for systematic reviews,7,9 and supporting physicians in various clinical settings as generalist medical AI,4 among other possibilities. In addition to augmenting LLMs with retrieval results from a search engine, LLMs can also be taught to use biomedical domain-specific tools, such as the Web APIs of specialized databases, to provide improved access to biomedical information.10

In summary, although ChatGPT is not currently suitable for use as a literature search engine on its own, we envision that the proposed retrieve, summarize, and verify paradigm could greatly benefit biomedical information seeking. This approach leverages the impressive capability of LLMs to generate high-level summaries while minimizing the risk of directly using false or fabricated information by combining LLMs and search engines. It is important to note that although LLM technology is progressing rapidly, it has not yet matured enough for clinical use. Therefore, users must retain full responsibility for verifying the accuracy and reliability of its output.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program, National Library of Medicine.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program, National Library of Medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Qiao Jin, Zhiyong Lu.

Investigation: Qiao Jin, Robert Leaman.

Supervision: Zhiyong Lu.

Writing – original draft: Qiao Jin.

Writing – review & editing: Qiao Jin, Robert Leaman.

References

- 1.OpenAI: ChatGPT. Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue. Accessed November 30. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, Sillos C, De Leon L, Elepano C. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit Health. 2023;2:e0000198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SB, Lam K, ChatGPT. The future of discharge summaries? Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5(3):e107–e108. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moor M, Banerjee O, Abad ZSH, Krumholz HM, Leskovec J, Topol EJ. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature. 2023;616(7956):259–265. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal K Azizi S Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge [published online ahead of print December 26, 2022]. arXiv. 2022:221213138. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2212.13138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeblick K Schachtner B Dexl J, et al. ChatGPT makes medicine easy to swallow: an exploratory case study on simplified radiology reports [published online ahead of print December 20 2022]. arXiv. 2022:221214882. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2212.14882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaib C, Li ML, Joseph S, Marshall IJ, Li JJ, Wallace BC. Summarizing, simplifying, and synthesizing medical evidence using GPT-3 (with varying success) [published online ahead of print May 10, 2023]. arXiv. 2023:230506299. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2305.06299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu NF, Zhang T, Liang P. Evaluating verifiability in generative search engines [published online ahead of print April 19, 2023]. arXiv. 2023:230409848. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2304.09848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, Scells H, Koopman B, Zuccon G. Can Chatgpt write a good boolean query for systematic review literature search? [published online ahead of print February 3, 2023] arXiv. 2023:230203495. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2302.03495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Q, Yang Y, Chen Q, Lu Z. GeneGPT: augmenting large language models with domain tools for improved access to biomedical information [published online ahead of print April 19, 2023]. arXiv. 2023:230409667. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2304.09667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]