Abstract

Cutaneous immune-related adverse events are frequently associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) administration in cancer patients. In fact, these monoclonal antibodies bind the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 and programmed cell death-1/ligand 1 leading to a non-specific activation of the immune system against both tumoral cells and self-antigens. The skin is the most frequently affected organ system appearing involved especially by inflammatory manifestations such as maculopapular, lichenoid, psoriatic, and eczematous eruptions. Although less common, ICI-induced autoimmune blistering diseases have also been reported, with an estimated overall incidence of less than 5%. Bullous pemphigoid-like eruption is the predominant phenotype, while lichen planus pemphigoides, pemphigus vulgaris, and mucous membrane pemphigoid have been described anecdotally. Overall, they have a wide range of clinical presentations and often overlap with each other leading to a delayed diagnosis. Achieving adequate control of skin toxicity in these cases often requires immunosuppressive systemic therapies and/or interruption of ICI treatment, presenting a therapeutic challenge in the context of cancer management. In this study, we present a case series from Italy based on a multicenter, retrospective, observational study, which included 45 patients treated with ICIs who developed ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid. In addition, we performed a comprehensive review to identify the cases reported in the literature on ICI-induced autoimmune bullous diseases. Several theories seeking their underlying pathogenesis have been reported and this work aims to better understand what is known so far on this issue.

Keywords: immunotherapy, anti PD-1, anti PD-L1, cutaneous irAE, bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus pemphigoides, pemphigus, mucous membrane pemphigoid

1. Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have represented an innovation in the treatment of several malignancies since the approval of ipilimumab in 2011 (1). These are monoclonal antibodies targeting the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) or programmed cell death-1/ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) which are involved in the negative regulation of T-cell immune function. This binding causes the failure of the tumoral evasion mechanisms, and, consequently, an increased triggering of the immune system against cancer. However, this immune activation is non-specific and it can affect many different organ systems leading to the so-called immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in up to 70% of treated patients, such as pneumonitis, colitis, endocrinopathies, and myocarditis (2).

The skin is the most involved organ being affected in approximately 30% of patients treated with anti PD-(L)1 and 50% with anti CTLA-4 drug, respectively (3, 4). Furthermore, patients who develop a cutaneous irAE (cirAE) need close monitoring for signs or symptoms of extracutaneous ones as it may be a predictive factor (5). It has been proposed to divide the cirAEs into four histopathological categories which are inflammatory, immunobullous, keratinocyte changes and melanocyte changes. The inflammatory ones are the most frequent and appear as maculopapular, lichenoid, psoriatic and eczematous eruptions (6). Even though the development of cirAEs has been associated with an increased survival and tumor response (7–9) their prognostic significance remains unclear (10).

Immunobullous eruptions have been increasingly reported in the literature mostly linked to anti PD-1/PD-L1 drugs. The estimated overall incidence varies from 1 to 5% (11, 12), with bullous pemphigoid (BP) being the most commonly observed phenotype. Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) have also been described in association with ICIs, albeit uncommonly. Bullous irAEs represent a therapeutic challenge for clinicians because they might result in significant morbidity and mortality if untreated. Moreover, immunosuppressive systemic therapies and/or ICI interruption are often required to reach adequate control of the cutaneous involvement resulting in a worsening of the cancer prognosis (11).

Herein, we reported our Italian case series about ICI-induced autoimmune blistering disorders, especially ICI-BP. In addition, we conducted a comprehensive review of bullous cirAEs to compare our data with the cases already described and to better understand what is known so far on this issue.

2. Materials and methods

This is a case series based on a national multicenter, retrospective, observational cohort including all patients treated with ICIs and developed an immunobullous cirAE during treatment or up to 12 months after discontinuation. Data were collected from 14 Italian hospitals between September 2021 and February 2023, after the institutional review board approval obtained from the ethic committee of the Turin University hospital. Information reported included patient demographics (age, sex), oncology history, ICI therapy, cirAE presentation and severity, histopathological findings, direct and indirect immunofluorescence (DIF/IIF), antibodies detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), cirAE treatment, and tumor outcome. No patient identifiable data were used. The immunobullous cirAE diagnosis had to be supported by at least one positive test including histopathological examination, DIF, IIF or ELISA. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) ver. 5.0 was used to identify skin toxicity severity. Quantitative values were expressed as the median value and range.

Moreover, we performed a comprehensive review of the English-language medical literature about immunobullous cirAE. We used the databases PubMed, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science. Search strategy identified articles with the terms “bullous pemphigoid,” “lichen planus pemphigoides,” “pemphigus,” and “mucous membrane pemphigoid” combined with “cancer immunotherapy,” “immune checkpoint inhibitors,” “nivolumab,” “pembrolizumab,” “cemiplimab,” “ipilimumab,” “avelumab,” “atezolizumab,” “durvalumab.” The search involved all fields including title, abstract, keywords, and full text. Articles without available full text or with limited and inconsistent data from individual patients were excluded. We considered papers published by January 2023.

3. Immunobullous cirAEs–comprehensive review

3.1. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced BP and MMP

BP is characterized by subepithelial blister formation and inflammation with abundant eosinophils. Autoantibodies targeting two structural proteins of the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ), BP antigen 1 (BPAG1 or BP230 antigen) and BPAG2 (or termed BP180 antigen), are involved in the pathogenesis (13). Its prevalence is increasing due to several factors such as the growing exposure to novel drug classes that might be implicated in eliciting the disease as the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors and ICIs (13, 14). The reported incidence of BP as a cirAE varies between 0.3% and 3.8% across different studies (15–17).

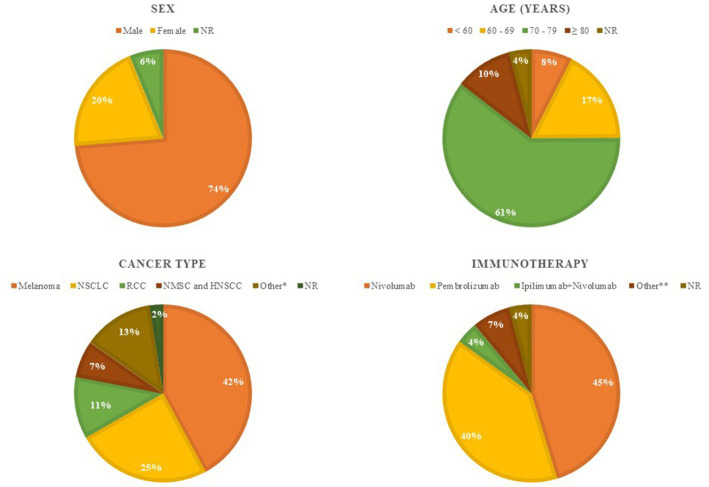

We collected the available data from 373 patients affected by ICI-induced BP and mainly published as case reports, case series and reviews (15, 16, 18–49). The collected information is summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. The pie charts reported in Figure 1 identify the demographic and cancer characteristics. Men more frequently develop ICI-BP [275 of 373 (74%)] especially in the VII decade of life [226 of 373 (61%)]. The most common primary tumors were melanoma [157 of 373 (42%)] and NSCLC [92 of 373 (25%)], and anti PD-1 drug was the most frequently associated with this cirAE since nivolumab was implicated in 45% of cases (169 of 373) and pembrolizumab in 40% (148 of 373). Table 1 reports the details regarding ICI-BP features, as well as its management and the tumor outcome. The median time interval between ICI initiation and BP onset was 26 weeks (2–209). Although most BP cases developed during the administration of immunotherapy, 25 patients experienced BP onset after ICI discontinuation with a median interval of 9 weeks. According to the CTCAE ver. 5.0, among 202 patients with sufficient information, 43% (86 of 202) was affected by more than 30% of the body surface area and the mucosal involvement was reported in 20% of cases (76 of 373). Diagnosis of BP was established by biopsy and histopathological examination in 250 of 373 patients (67%). In several cases, additional tests confirmed the diagnosis including DIF (220 of 249 patients tested), IIF (107 of 144 patients tested), as well as ELISA and/or immunoblotting for BP180/BP230 autoantibodies. The levels of BP180 autoantibodies were elevated in 121 of the 172 patients tested (70%), while BP230 autoantibody levels were increased in only 27 of the 136 performed cases (20%). Immunotherapy was permanently discontinued after BP development in 49% of patients (182 of 373), and the most used treatment was systemic corticosteroids [231 of 373 (62%)] followed by tetracycline-class antibiotic associated or not with niacinamide/nicotinamide [140 of 373 (38%)]. Regarding the tumor outcome, among patients with available information (n = 218), 32% (n = 68) had stable disease, 23% (n = 51) had a complete response, 23% (n = 51) had progression disease, and 22% (n = 48) had a partial response.

Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 373 ICI-induced BP cases identified among published articles. These pie charts report overall patient demographic [sex and age] and tumor characteristics [tumor type and immunotherapy]. *Other tumor type: urothelial cancer [n = 14], Merkel cell carcinoma [n = 4], colorectal cancer [n = 3], endometrial carcinoma [n = 2], breast cancer [n = 2], esophageal/gastric cancer [n = 2], mesothelioma [n = 2], prostate cancer [n = 2], thymoma [n = 1], hepatocellular carcinoma [n = 1], intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [n = 1], brain pinoblastoma [n = 1], glottic cancer [n = 1], salivary gland cancer [n = 1], peripheral T-cell lymphoma [n = 1], cervical cancer [n = 1], anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [n = 1]. **Other immunotherapy: cemiplimab [n = 7], durvalumab [n = 5], atezolizumab [n = 5], ipilimumab [n = 3], bintrafusp alfa [n = 4], tislelizumab [n = 1], avelumab [n = 1]. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; BP, bullous pemphigoid; NR, not reported; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 1.

Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of the 373 ICI-induced BP cases identified among published articles.

| Features | All patients (N = 373) | Features | All patients (N = 373) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time interval between ICI initiation and BP onset, median in weeks (min - max)A | 26 (2–209) | Adjustment of ICI regimen | No. |

| Mucosal membrane involvement | No. | Discontinued before BP onset, No., median interval in weeks between ICI interruption and BP onset | 25, 9 |

| Yes | 76 | Discontinued after BP onset | 182 |

| No | 226 | Temporarily discontinued then resumed | 21 |

| NR | 71 | Continued without interruption | 76 |

| Highest CTCAE grade B | No. | NR | 69 |

| G1 | 33 | Treatments used for BP | No. |

| G2 | 83 | Topical steroid alone or no treatment | 93 |

| G3 | 69 | Systemic steroid | 231 |

| G4 | 17 | Tetracycline-class antibiotic alone, in association with niacinamide/nicotinamide | 93, 47 |

| Unable to determine | 161 | Dapsone | 18 |

| Histopathologic examination | No. | Dupilumab | 15 |

| Yes | 250 | Omalizumab alone, in association with IVIG | 14, 2 |

| No | 34 | Methotrexate | 16 |

| NR | 89 | Rituximab alone, in associationa with IVIG, in association with plasma exchange | 14, 3, 1 |

| DIF | No. | IVIG | 9 |

| Positive | 220 | Mycophenolate mofetil | 8 |

| Negative | 29 | Azathioprine | 3 |

| Not performed | 23 | Infliximab | 1 |

| NR | 101 | Acitretin | 1 |

| IIF | No. | Hydroxychloroquine | 1 |

| Positive | 107 | Ciclophosphamide | 1 |

| Negative | 37 | NR | 23 |

| Not performed | 124 | Cancer outcome | No. |

| NR | 105 | PD | 51 |

| BP180 autoantibody | No. | SD | 68 |

| Positive | 121 | PR | 48 |

| Negative | 51 | CR | 51 |

| Not measured | 35 | NR | 155 |

| NR | 166 | ||

| BP230 autoantibody | No. | ||

| Positive | 27 | ||

| Negative | 109 | ||

| Not measured | 46 | ||

| NR | 191 |

This table summarizes the information about the latency of BP development and its CTCAE grade, diagnostic findings (histopathology, DIF, IIF, BP180 and BP230 autoantibodies), and management. AMedian time interval between ICI initiation and BP onset was calculated considering the weeks published in the article, or an estimation when the authors reported the number of treatment cycles/months. BHighest ICI-BP grade is according to CTCAE ver. 5 (bullous dermatosis) and, if not reported by authors, was estimated from available clinical information; in 10 patients the grade reported was based on BPDAI score (mild in n = 2, moderate in n = 2, and severe in n = 6). ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; BP, bullous pemphigoid; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; BPDAI, Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index; NR, not reported; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progression disease.

MMP is a pemphigoid disease with predominant mucosal involvement and cicatricial healing of its lesions. It is characterized by the production of autoantibodies directed against the C-terminal domain of BP180 combined or not with reactivity against the BP180-NC16A epitope. Other target antigens, such as BP230, laminin 332 a6b4-integrin and type VII collagen, have been identified (50). The oral cavity and conjunctiva are the most involved sites, following by nasopharynx and genitalia. The involvement of larynx, esophagus, and trachea can give life-threatening complications due to cicatricial strictures (51). Skin lesions can be present but are often confined to the face and scalp (52).

Among published literature, we identified 10 patients (5 males and 5 females), with an average age of 69 years (47–84 years), affected by ICI-induced MMP (33, 50, 52–58). Their characteristics are reported in Supplementary Table S1. Pembrolizumab was the mainly culprit ICI [6 of 10 (60%)] with a median time to onset since first administration of 33 weeks (3–66 weeks). MMP manifestations are generally classified according to the severity of the disease into low risk, defined as oral mucosa involvement with or without skin lesions, and high-risk, when any other site is involved resulting more frequently in cicatricial sequelae (58). Among this small case series, 80% of patients could be classified as low risk (33, 50, 52, 54–57) according to reported clinical information, while 20% as high risk (53, 58) considering the upper respiratory mucosa involvement that in one case required the tracheostomy due to laryngeal stenosis (53).

3.2. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced LPP

LPP was previously considered to be a variant of lichen planus (the so-called bullous LP) or BP. In fact, it would seem to be a distinct autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease characterized by the presence of autoantibodies targeting BP180 and a relatively benign course (59). The first clinical manifestation in both LPP and bullous LP is pruritic violaceous polygonal papules and plaques. Blisters and erosions appear later and mainly on the extremities. In LPP, bullous lesions typically develop both on unaffected and affected skin, while in bullous LP they appear on a previous lichenoid lesion (60). This clinical distinction does not occur in all cases making it necessary for the diagnosis the detection of anti BP180 autoantibodies as they are present in LPP but not in bullous LP. Indeed, it has been hypothesized that lichenoid inflammation itself may promote the development of an autoimmune response against DEJ in LPP, exposing several antigens due to extensive apoptosis of the basal epidermis. On the other hand, blisters occur in bullous LP as the result of a massive vacuolar degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal–epidermal separations (59). An association between the development of LPP and drugs or pre-existing medical conditions has been previously reported. In recent years, rare cases of anti-PD-1/PD-L1-induced LPP have been documented and we identified a total of 23 cases (11, 33, 61–77).

These patients are 13 females (57%) and 10 males (43%), with a median age of 66 years (12–87 years), older than that found in the classic type (median age of 46 years) (59). Complete data are reported in Supplementary Table S2. They received immunotherapy to treat especially lung cancer [9 out of 23 (39%)], melanoma [5 out of 23 (22%)] and renal cell/urothelial cancer [4 out of 23 (17%)]. Administered drugs included mainly pembrolizumab [12 out of 23 (52%)] and nivolumab [8 out of 23 (35%)]. In all reported cases, LPP began as a lichenoid dermatitis with or without blisters and with an average onset time of about 17 weeks (1 week–2 years) since the ICI initiation. In about 61% of patients (14 out of 23), the eruption was widespread affecting the trunk, upper and lower limbs. Mucosal involvement was reported in less than half of the patients [9 out of 23 (39%)], in most cases as erosive mucositis. Five cases did not manifest BP features to clinical (bullous lesions) and histological (subepidermal blisters containing eosinophils, perivascular mixed infiltrate) evaluation, therefore the diagnosis was made thanks to ELISA or immunoblotting. These tests revealed the presence of autoantibodies targeting BP180 in all the 16 patients tested. Treatment with immunotherapy was interrupted after LPP development in 16 patients (70%) and temporarily discontinued in 4 patients (17%). Local, oral and/or intravenous corticosteroids with a wide range of doses were the first-line therapy in all cases while 8 patients (35%) required other systemic therapies. Among patients with available data about tumor outcome (n = 15), 10 patients had progression disease at the last follow-up visit or died due to cancer, 4 patients had stable disease, while only one patient had a complete response.

3.3. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced PV and paraneoplastic pemphigus

Pemphigus is a group of life-threatening and rare blistering diseases characterized by the production of autoantibodies directed against intercellular adhesion molecules. These autoantibodies induce epidermal acantholysis leading to the formation of intraepidermal blisters that clinically manifest as flaccid bullae, erosions, pustules on the skin and/or mucosal erosions (78).

PV is the most common form, and it is associated with the production of autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) and 3 (Dg3) (78). In several cases, it may be induced by drugs belonging to thiol, phenol, and non-thiol non-phenol classes, which may contribute to the development of acantholysis through several mechanisms (79). A few cases of pemphigus developed de novo or found to be aggravated upon introduction of immunotherapy have also been reported (78, 80–83) and we summarized their characteristics in Supplementary Tables S3, S4.

The immune mechanism that leads to the breakdown of tolerance in PV during therapy with ICIs are not fully understood. Schoenberg et al. described the case of a patient affected by ICI-PV and in whom investigation of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing revealed three class II HLA alleles (DQB1*0302, DQA1*0301, and DRB1*04) associated with genetic susceptibility for pemphigus (81). This suggests that ICIs could unmask a genetic susceptibility stimulating the immune system and leading to the PV clinical expression. Furthermore, PV could be triggered in cancer patients by concomitant factors such as immunotherapy and radiotherapy (80, 84). Two cases of pre-existing PV recurred during immunotherapy have also been reported (82, 83). Patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases have been excluded from the ICIs clinical trials due to the flare risk. Nevertheless, immunotherapy should not necessarily be ruled out in these patients as most relapses have been reported to be mild (85). Krammer et al. described the case of a PV-flare occurred during nivolumab therapy after a remission period of several years and resolved within 8 weeks of treatment with prednisolone tapering and methotrexate without requiring immunotherapy discontinuation (82). Therefore, a case of pre-existing pemphigus foliaceus not relapsed during ICI therapy has also been reported (86).

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another type of pemphigus whose clinical hallmark is recalcitrant and painful mucositis, which may be accompanied by polymorphic cutaneous eruptions as blisters, erosions, and lichenoid lesions. It is characterized by the production of autoantibodies against various target antigens, mainly envoplakin and periplakin (87), and occurs in the setting of occult or confirmed neoplasms, mostly lymphoproliferative disorders (up to 84% of reported cases) (88). There are also few cases of PNP occurred during immunotherapy (89–91) whose features suggest a relation between its onset and the oncological therapy instead of the cancer (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). In fact, it has been described in the setting of epithelial origin-carcinomas treated with ICIs, while they account for less than 10% of the classic PNP cases (88). Furthermore, McNally et al. reported a patient treated with pembrolizumab due to a urothelial carcinoma who developed PNP without evidence of active tumor. PNP is almost always associated with an active neoplasm, and it has rarely been reported in patients who are either in remission or have no detectable underlying neoplasm (90). Also the close temporal relation between ICI initiation and PNP onset suggests a triggering role of immunotherapy as reported in a patient who developed it after 3 months of pembrolizumab therapy due to a 10-year history of a SCC of the tongue (89).

4. Results–Italian case series

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the patients reported in our case series. These are 45 cases, 41 males (91%) and 4 females (9%), with a median age of 74 years (range 46–90). In all cases, they developed an ICI-induced BP while they were receiving the cancer treatment. The ICI identified were mainly nivolumab [28 of 45 (62%)] and pembrolizumab [11 of 45 (25%)], in the remaining cases combination ipilimumab with nivolumab, cemiplimab, spartalizumab, and atezolizumab were reported [6 of 45 (13%)]. They were used for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [18 of 45 (40%)], melanoma [12 of 45 (27%)], colorectal adenocarcinoma [5 of 45 (11%)], renal clear cell carcinoma [5 of 45 (11%)], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [4 of 45 (9%)], urothelial carcinoma [1 of 45 (2%)], and in 73% of cases they were stage IV (33 of 45). The median time to onset of cutaneous symptoms after ICI initiation was 35 weeks (range 4–260), while the median time to BP diagnosis was 48 weeks (range 5–286). In 19 patients (42%) pruritus without any cutaneous eruption was the first clinical manifestation, while bullous lesions appeared since the beginning in 9 patients (20%). The mucosal involvement was reported in 8 patients (18%). According to CTCAE grading for bullous dermatitis, BP affected more than 30% of the body surface in 40% of patients (G3 and G4 in 18 of 45 cases). Skin biopsy for histopathological examination was performed in 28 patients (62%) and it confirmed the diagnosis in all cases, while DIF and IIF were carried out in 31 (69%) and 26 (58%) patients, respectively, showing positive results in all cases. The ELISA for BP180 autoantibody was performed in 42 cases and was positive in 30 patients (66%), while the ELISA for BP230 autoantibody was carried out in 41 cases and was positive in 15 patients (33%). The first-line therapy of the cutaneous toxicity was topical steroids in 4 patients (9%), topical and systemic steroids in 41 (91%). In 18% of cases (n = 8) a second-line therapy was needed such as doxycycline (n = 5) and dapsone (n = 3). One patient required a third-line therapy with dupilumab. Immunotherapy was permanently discontinued for 17 patients (38%), while it was temporarily held for 16 patients (36%) of which about 50% (n = 7) experienced a relapse after rechallenging with the same ICI. The median time between the BP diagnosis and the control of symptoms was 9 weeks (range 1–68) in the 38 patients (84%) with a partial or complete response. In the remaining 16% (n = 7) the ICI-BP was refractory to the treatment. Tumor response of the 36 cases with available data revealed that 9 patients (20%) had a complete or partial response, 16 (36%) had stable disease, and 11 (24%) had progression disease.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 45 patients collected in our national multicenter cohort.

| Characteristics | All patients (N = 45) | Characteristics | All patients (N = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ICI-BP diagnosis | ||

| Sex, No. (%) male/female | 41 (91)/4 (9) | Histopathologic examination | No. (%) |

| Age (years), median (range) | 74 (46–90) | Yes | 28 (62) |

| Tumor type | No. (%) | No | 17 (38) |

| NSCLC | 18 (40) | DIF | No. (%) |

| Melanoma | 12 (27) | Yes | 31 (69) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | 5 (11) | No | 14 (31) |

| Renal clear cell carcinoma | 5 (11) | IIF | No. (%) |

| HNSCC | 4 (9) | Yes | 26 (58) |

| Urothelial carcinoma | 1 (2) | No | 19 (42) |

| Tumor stage | No. (%) | BP180 autoantibodies | No. (%) |

| Stage IV | 33 (73) | Positive | 30 (66) |

| Stage III | 9 (20) | Negative | 12 (27) |

| Other or NR | 3 (7) | Not performed | 3 (7) |

| Immunotherapy | No. (%) | BP230 autoantibodies | No. (%) |

| Nivolumab | 28 (62) | Positive | 15 (33) |

| Pembrolizumab | 11 (24) | Negative | 26 (58) |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab | 2 (5) | Not performed | 4 (9) |

| Cemiplimab | 2 (5) | ICI management | No. (%) |

| Spartalizumab | 1 (2) | ICI temporarily held | 16 (36) |

| Atezolizumab | 1 (2) | BP flare after rechallenged with the same ICI | 7 (16) |

| ICI-BP features | Median (range) | ICI permanently discontinued | 17 (38) |

| Time to symptoms onset after ICI initiation (weeks) | 35 (4–260) | ICI-BP management | |

| Time to BP diagnosis after ICI initiation (weeks) | 48 (5–286) | First line therapy | No. (%) |

| First manifestations | No. (%) | Topical costicosteroid | 4 (9) |

| Pruritus without other manifestations | 19 (42) | Topical corticosteroid + systemic corticosteroid | 41 (91) |

| Eczematous eruption | 11 (24) | Second line therapy | No. (%) |

| Bullous lesions | 9 (20) | Doxycycline | 5 (11) |

| Urticarial eruption | 7 (16) | Dapsone | 3 (7) |

| Mucositis | 3 (7) | Third line therapy | No. (%) |

| Papular lesions | 1 (2) | Dupilumab | 1 (2) |

| Mucosal membrane involvement | No. (%) | ICI-BP response | No. (%) |

| No | 37 (82) | Partial to complete resolution | 38 (84) |

| Yes | 8 (18) | Refractory symptoms | 7 (16) |

| CTCAE grade | No. (%) | Tumor response | No. (%) |

| 1 | 12 (27) | CR or PR | 9 (20) |

| 2 | 15 (33) | SD | 16 (36) |

| 3 | 17 (38) | PD | 11 (24) |

| 4 | 1 (2) | NR | 9 (20) |

All patients developed ICI-induced BP. The information reported is about patients’ demographics, primary cancer, immunotherapy, and ICI-induced BP. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; BP, bullous pemphigoid; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NR, not reported; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progression disease.

5. Discussion

Bullous autoimmune dermatoses are an uncommon cirAE whose prevalence is challenging to determine because it varies among several studies. Nevertheless, it is well known to be more infrequent than inflammatory eruptions or vitiligo (6, 92) since its reported incidence rates are less than 5% (11, 93). The exact underlying pathogenesis of bullous cirAEs has not fully understood but it potentially involves both the innate and adaptive immune systems.

In the tumor microenvironment, anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies enhance exhausted T effector cells function leading to immune activation against cancer. The lysis of tumoral cells releases numerous antigens whose presentation by antigen presenting cells causes the abnormal priming of both cytotoxic T lymphocytes and T helper 1 (Th1) cells. These mechanisms interfere with the immune tolerance resulting in the attack even against self-tissues (6). It is not surprising that lichenoid skin reaction is one of the most common cirAEs because this Th1-polarized reaction can cause intense interface dermatitis. It has been proposed that the lichenoid inflammation might expose antigens in the basal layer, making them targets for antibody development. In fact, research has demonstrated a role for T-cell trigger in enhancing the humoral response as well as a T-cell independent PD-1+ B-cell activation resulting in an aberrant antibodies production (94, 95). This theory could also explain why BP is the most common ICI-induced bullous dermatosis. In fact, the hemidesmosomes (BP180 and BP230) at the DEJ are more exposed than the desmogleins or other intercellular adhesion molecules to antibodies formation following the interface damage. In addition, the substantial male predominance among patients affected by ICI-induced BP, unlike classic BP, it could be associated with some sex-associated molecular differences. Indeed, it has been reported a higher tumor mutational burden and the presence of more immunogenic neoantigens in male patients with melanoma, so this may contribute to an increased incidence of irAE such as ICI-BP (96).

BP180 is normally expressed by undifferentiated keratinocytes of the basal layer, and it is ceased as they migrate upwards and differentiate in the epidermis. For this reason, it is expressed in SCC as a hallmark of de-differentiation (97). Therefore, it can also be detected in cells of neural crest origin as in proliferating melanocytes with an undifferentiated phenotype. Sequencing of COL17A1 from melanoma cDNA has revealed a series of aberrations that cause the post-translational degradation of the ectodomain and so its deficiency (98). Consequently, the endodomain accumulates in tumor cells, which has been associated with an invasive phenotype. This aberrant expression of BP180 is an accessible target for in vitro immunotherapy (99). These findings suggest that targeting of BP180 on tumor cells by the activated immune system could lead to a cross-reactive immunogenicity against the DEJ and the development of BP (100). The “same-antigen theory” could also explain ICI-induced PNP in patients affected by SCC as it is a cancer arising from keratinocytes and expressing autoantigens routinely identified in PNP (91). Moreover, anti-BP180 auto-antibodies in the sera of melanoma patients have been reported to be significantly higher than in the sera of healthy, at both early and advanced stages of disease, and this correlates with a higher probability for these patients to develop BP during anti-PD1 therapy (101).

The immunotherapy could also unmask a genetic susceptibility to develop bullous autoimmune disorders activating the immune system and leading to the clinical expression. The HLA-DQB1*03:01 allele which has been associated to BP has been found in higher frequencies in melanoma patients (102).

Data collected in our case series have confirmed what has already been described in the literature on ICI-induced BP. Unlike classic-BP, it has a male predominance (103) and this has been assumed to be associated with gender effects on immunotherapy activity (96). Drug-induced pemphigoid, as well as ICI-BP, is characterized by a younger age of onset (104) compared to the classic type whose incidence increases significantly over 80 years (105). BP-like eruption has been reported most frequently in patients receiving anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies for melanoma and NSCLC. It is not a class effect of these drugs but their mechanism of action close to peripheral tissues may be related to an increased reactivity against cutaneous self-antigens (106). ICI-BP appears later than other cirAEs (17, 107) and it is often preceded by a longer prodromal phase than classic BP characterized by persisting pruritus and/or non-specific dermatitis. In fact, it has a significantly longer delay from symptom onset to diagnosis than the classic one despite having similar delays from symptom onset to dermatology referral (47). Even though ICI-BP seems to have some peculiar clinical features, this does not reflect significant differences regarding histopathologic and DIF findings (35). Given the moderate-to-severe clinical presentation (17) and delayed diagnosis, management of ICI-BP often necessitates discontinuation of immunotherapy and treatment with oral/intravenous corticosteroids to control the cutaneous toxicity. Although several studies have suggested an association between the development of ICI-BP and improved cancer outcomes (7, 46, 48), the heterogeneity of information collected in this paper does not allow for confirmation of this theory. Future studies should evaluate the best tumor response in patients with ICI-BP based on cancer types and treatment modalities.

6. Conclusion

Bullous autoimmune dermatoses have gained increasing interest among cirAEs induced by anti PD-1/PD-L1 autoantibodies. Among the published literature, ICI-induced BP is the most frequently described, while LPP, MMP and pemphigus are reported anecdotally. There are several theories which try to clarify their underlying pathogenesis without a complete success. It potentially involves both the innate and adaptive immune systems, the cross-reactivity immunogenicity, the genetic susceptibility, and other unknown factors. The clinical presentation of these bullous cirAEs can vary, posing a challenge for prompt recognition and appropriate treatment. Immunossuppressive therapy and/or discontinuation of immunotherapy are often necessary for management. Dermatological referral is necessary to establish as soon as possible an appropriate therapeutic algorithm to control the cutaneous toxicity avoiding a negative impact on cancer outcome.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MM, SR, and PQ contributed to conception and design of the study and organized the database. MM and MAc contributed to literature search. MM, MR, AMa, GZ, FM, EA, RM, EC, AP, GG, PSo, CS, MC, LP, DF, RB, PSe, PV, MT, MAr, CV, AMi, RS, ED, and BM contributed to collection of the case series based on the national multicentre cohort. MM wrote the manuscript. MR, AMa, GZ, EA, EC, SR, and PQ contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to SIDeMaST Italian group of Immunopathology and task force TICURO for collaborating on this manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1208418/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Cameron F, Whiteside G, Perry C. Ipilimumab: first global approval. Drugs. (2011) 71:1093–104. doi: 10.2165/11594010-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boland P, Pavlick AC, Weber J, Sandigursky S. Immunotherapy to treat malignancy in patients with pre-existing autoimmunity. J Immunother Cancer. (2020) 8:e000356. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000356, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han Y, Wang J, Xu B. Cutaneous adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2021) 163:103376. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dika E, Ravaioli GM, Fanti PA, Piraccini BM, Lambertini M, Chessa MA, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects during ipilimumab treatment for metastatic melanoma: a prospective study. Eur J Dermatol. (2017) 27:266–70. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2017.3023, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson LL, Krasnow NA, Chang MS, Yoon J, Li EB, Polyakov NJ, et al. Patterns of cutaneous and noncutaneous immune-related adverse events among patients with advanced Cancer. JAMA Dermatol. (2021) 157:577–82. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0326, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seervai RNH, Sinha A, Kulkarni RP. Mechanisms of dermatological toxicities to immune checkpoint inhibitor cancer therapies. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2022) 47:1928–42. doi: 10.1111/ced.15332, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang K, Seo J, Tiu BC, Le TK, Pahalyants V, Raval NS, et al. Association of Cutaneous Immune-Related Adverse Events with Increased Survival in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy. JAMA Dermatol. (2022) 158:189–93. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5476, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson LL, Chang MS, Polyakov NJ, Blum AE, Josephs N, Krasnow NA, et al. Prognostic significance of cutaneous immune-related adverse events in patients with melanoma and other cancers on immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2022) 86:886–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shreberk-Hassidim R, Aizenbud L, Lussheimer S, Thomaidou E, Bdolah-Abram T, Merims S, et al. Dermatological adverse events under programmed cell death-1 inhibitors as a prognostic marker in metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15747. doi: 10.1111/dth.15747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelin E, Maronese CA, Dri A, Toffoli L, Di Meo N, Nazzaro G, et al. Identifying candidates for immunotherapy among patients with non-melanoma skin Cancer: a review of the potential predictors of response. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:3364. doi: 10.3390/jcm11123364, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel J, Totonchy M, Damsky W, Berk-Krauss J, Castiglione F, Sznol M, et al. Bullous disorders associated with anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapy: a retrospective analysis evaluating the clinical and histopathologic features, frequency, and impact on cancer therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2018) 79:1081–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosche C, Owen JL, Sadowsky LM, Choi JN. Bullous dermatoses secondary to anti-PD-L1 agents: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. (2019) 25:45817. doi: 10.5070/D32510045817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu SD, Chen WT, Chi CC. Association between medication use and bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. (2020) 156:891–900. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1587, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kridin K, Cohen AD. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2021) 85:501–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.048, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Said JT, Liu M, Talia J, Singer SB, Semenov YR, Wei EX, et al. Risk factors for the development of bullous pemphigoid in US patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. JAMA Dermatol. (2022) 158:552–7. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0354, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi CR, Otto TS, Thompson LL, Chang MS, Reynolds KL, Chen ST. Methotrexate in the treatment of immune checkpoint blocker-induced bullous pemphigoid. Eur J Cancer. (2021) 159:34–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.032, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wongvibulsin S, Pahalyants V, Kalinich M, Murphy W, Yu KH, Wang F, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for the development of cutaneous toxicities in patients treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors: a United States population-level analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2022) 86:563–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.094, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Correia C, Fernandes S, Soares-de-Almeida L, Filipe P. Bullous pemphigoid probably associated with pembrolizumab: a case of delayed toxicity. Int J Dermatol. (2022) 61:e129–31. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15796, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshina D, Hotta M. Intravenous immunoglobulin for pembrolizumab-induced bullous pemphigoid-like eruption: a case report. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15948. doi: 10.1111/dth.15948, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Povilaityte E, Gellrich FF, Beissert S, Abraham S, Meier F, Günther C. Treatment-resistant bullous pemphigoid developing during therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2021) 35:e591–3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17321, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun JSW, Chan OB, Goh M, Mc Cormack CJ. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a case series of 13 patients. Aust J Dermatol. 64:131–7. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huynh LM, Bonebrake BT, DiMaio DJ, Baine MJ, Teply BA. Development of bullous pemphigoid following radiation therapy combined with nivolumab for renal cell carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e28199. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028199, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruni M, Moar A, Schena D, Girolomoni G. A case of nivolumab-induced bullous pemphigoid successfully treated with dupilumab. Dermatol Online J. (2022) 28:57396. doi: 10.5070/D328257396, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molle MF, Capurro N, Herzum A, Micalizzi C, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Self-resolving bullous pemphigoid induced by cemiplimab. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15466. doi: 10.1111/dth.15466, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotera N, Weilg P, Heleno C, Ferrari-Gabilondo N. A case of bullous pemphigoid associated with Nivolumab therapy. Cureus. (2022) 14:e24804. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mari R, Guerin M, Vicier C, Walz J, Bonnet N, Pignot G, et al. Durable disease control and refractory bullous pemphigoid after immune checkpoint inhibitor discontinuation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:984132. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.984132, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pop SR, Strock D, Smith RJ. Dupilumab for the treatment of pembrolizumab-induced bullous pemphigoid: a case report. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15623. doi: 10.1111/dth.15623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarado SM, Weston G, Murphy MJ, Stewart CL. Nivolumab-induced localized genital bullous pemphigoid in a 60-year-old male. J Cutan Pathol. (2022) 49:468–71. doi: 10.1111/cup.14183, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Sui D, Wang D, Zhang L, Wang R. Case report: a rare case of Pembrolizumab-induced bullous pemphigoid. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:731774. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.731774, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klepper EM, Robinson HN. Dupilumab for the treatment of nivolumab-induced bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. (2021) 27:27(9). doi: 10.5070/D327955136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Said JT, Talia J, Wei E, Mostaghimi A, Semenov Y, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Impact of biologic therapy on cancer outcomes in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2023) 88:670–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1186, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi W, Yamada K, Kumagai K, Kono M. Dyshidrosiform pemphigoid due to nivolumab therapy. Eur J Dermatol. (2021) 31:411–2. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2021.4052, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawsar A, Edwards C, Patel P, Heywood RM, Gupta A, Mann J, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor-associated bullous cutaneous immune-related adverse events: a multicentre observational study. Br J Dermatol. (2022) 187:981–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21836, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bur D, Patel AB, Nelson K, Huen A, Pacha O, Phillips R, et al. A retrospective case series of 20 patients with immunotherapy-induced bullous pemphigoid with emphasis on management outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2022) 87:1394–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niebel D, Wilsmann-Theis D, Bieber T, Berneburg M, Wenzel J, Braegelmann C. Bullous pemphigoid in patients receiving immune-checkpoint inhibitors and psoriatic patients-focus on clinical and histopathological variation. Dermatopathology (Basel). (2022) 9:60–81. doi: 10.3390/dermatopathology9010010, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jendoubi F, Sibaud V, Meyer N, Tournier E, Fortenfant F, Livideanu CB, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with Grover disease: a specific toxicity of anti-PD-1 therapies? Int J Dermatol. (2022) 61:e200–2. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16068, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schauer F, Rafei-Shamsabadi D, Mai S, Mai Y, Izumi K, Meiss F, et al. Hemidesmosomal reactivity and treatment recommendations in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid-a retrospective, monocentric study. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:953546. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.953546, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grünig H, Skawran SM, Nägeli M, Kamarachev J, Huellner MW. Immunotherapy (Cemiplimab)-induced bullous pemphigoid: a possible pitfall in 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. (2022) 47:185–6. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003894, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amber KT, Valdebran M, Lu Y, De Feraudy S, Linden KG. Localized pretibial bullous pemphigoid arising in a patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2018) 16:196–8. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13411_g, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearlman R, Badon H, Whittington A, Brodell RT, Ward KHM. The iso-oncotopic response: immunotherapy-associated bullous pemphigoid in tumour footprints. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2022) 47:1379–81. doi: 10.1111/ced.15177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asdourian MS, Shah N, Jacoby TV, Reynolds KL, Chen ST. Association of Bullous Pemphigoid with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in patients with Cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. (2022) 158:933–41. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chatterjee T, Rashid TF, Syed SB, Roy M. Bullous pemphigoid associated with Pembrolizumab therapy for non-small-cell lung Cancer: a case report. Cureus. (2022) 14:e21770. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21770, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cosimati A, Rossi L, Didona D, Forcella C, Didona B. Bullous pemphigoid in elderly woman affected by non-small cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: a case report and review of literature. J Oncol Pharm Pract. (2021) 27:727–33. doi: 10.1177/1078155220946370, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan CX, Pisano CE, DeSimone MS, Nambudiri VE. A 72-year-old man with nonhealing facial erosions and bullae. JAAD Case Rep. (2022) 27:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.026, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shalata W, Weissmann S, Itzhaki Gabay S, Sheva K, Abu Saleh O, Jama AA, et al. A retrospective, single-institution experience of bullous pemphigoid as an adverse effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14:5451. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215451, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Juzot C, Sibaud V, Amatore F, Mansard S, Seta V, Jeudy G, et al. Clinical, biological and histological characteristics of bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy: a national retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2021) 35:e511–4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molina GE, Reynolds KL, Chen ST. Diagnostic and therapeutic differences between immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced and idiopathic bullous pemphigoid: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. (2020) 183:1126–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson CA, Singer S, Chen T, Puleo AE, Lian CG, Wei EX, et al. Bullous pemphigoid after anti-programmed death-1 therapy: a retrospective case-control study evaluating impact on tumor response and survival outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2022) 87:1400–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto H, Ito T, Ichiki T, Yamada Y, Oda Y, Furue M. The clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and their outcomes. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:728. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040728, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zumelzu C, Alexandre M, Le Roux C, Weber P, Guyot A, Levy A, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid, bullous pemphigoid, and anti-programmed Death-1/ programmed death-ligand 1: a case report of an elderly woman with mucous membrane pemphigoid developing after Pembrolizumab therapy for metastatic melanoma and review of the literature. Front Med (Lausanne). (2018) 5:268. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du G, Patzelt S, van Beek N, Schmidt E. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. (2022) 21:103036. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fässler M, Rammlmair A, Feldmeyer L, Suter VGA, Gloor AD, Horn M, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid and lichenoid reactions after immune checkpoint inhibitors: common pathomechanisms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2020) 34:e112–5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16036, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bezinelli LM, Eduardo FP, Migliorati CA, Ferreira MH, Taranto P, Sales DB, et al. A severe, refractory case of mucous membrane pemphigoid after treatment with Pembrolizumab: brief communication. J Immunother. (2019) 42:359–62. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000280, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duan S, Zhang X, Wang F, Shi Y, Wang J, Zeng X. Coexistence of oral mucous membrane pemphigoid and lichenoid drug reaction: a case of toripalimab-triggered and pembrolizumab-aggravated oral adverse events. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2021) 132:e86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.05.012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durmus Ö, Gulseren D, Akdogan N, Gokoz O. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient treated with nivolumab for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Dermatol Ther. (2020) 33:e14109. doi: 10.1111/dth.14109, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haug V, Behle V, Benoit S, Kneitz H, Schilling B, Goebeler M, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. (2018) 179:993–4. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16780, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sibaud V, Vigarios E, Siegfried A, Bost C, Meyer N, Pages-Laurent C. Nivolumab-related mucous membrane pemphigoid. Eur J Cancer. (2019) 121:172–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.030, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lagos-Villaseca A, Koshkin VS, Kinet MJ, Rosen CA. Laryngeal mucous membrane pemphigoid as an immune-related adverse effect of Pembrolizumab treatment. J Voice. (2023) S0892-1997:00429–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, Baican A. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. (2022) 63:165–71. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus Pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1389. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01389, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyle MM, Ashi S, Puiu T, Reimer D, Sokumbi O, Soltani K, et al. Lichen planus Pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. (2022) 44:360–7. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000002139, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ee S, Liang MW, Tee SI, Wang DY. Lichen planus pemphigoides after pembrolizumab immunotherapy in an older man. Ann Acad Med Singap. (2022) 51:804–6. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2022134, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindner AK, Schachtner G, Tulchiner G, Staudacher N, Steinkohl F, Nguyen VA, et al. Immune-related lichenoid mucocutaneous erosions during anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma - a case report. Urol Case Rep. (2019) 23:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manko S, Côté B, Provost N. A case of durvalumab-induced lichenoid eruption evolving to bullous eruption after phototherapy: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. (2021) 9:2050313X2199327. doi: 10.1177/2050313X21993279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mueller KA, Cordisco MR, Scott GA, Plovanich ME. A case of severe nivolumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a child with metastatic spitzoid melanoma. Pediatr Dermatol. (2023) 40:154–6. doi: 10.1111/pde.15097, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qian J, Kubicki SL, Curry JL, Jahan-Tigh R, Benjamin R, Heberton M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced rash in a patient with angiosarcoma. JAAD Case Rep. (2022) 29:21–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.08.030, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shah RR, Bhate C, Hernandez A, Ho CH. Lichen planus pemphigoides: a unique form of bullous and lichenoid eruptions secondary to nivolumab. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 35:e15432. doi: 10.1111/dth.15432, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sugawara A, Koga H, Abe T, Ishii N, Nakama T. Lichen planus-like lesion preceding bullous pemphigoid development after programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitor treatment. J Dermatol. (2021) 48:401–4. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15693, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wat M, Mollanazar NK, Ellebrecht CT, Forrestel A, Elenitsas R, Chu EY. Lichen-planus-pemphigoides-like reaction to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. J Cutan Pathol. (2022) 49:978–87. doi: 10.1111/cup.14299, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshida S, Shiraishi K, Yatsuzuka K, Mori H, Koga H, Ishii N, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides with antibodies against the BP180 C-terminal domain induced by pembrolizumab in a melanoma patient. J Dermatol. (2021) 48:e449–51. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmidgen MI, Butsch F, Schadmand-Fischer S, Steinbrink K, Grabbe S, Weidenthaler-Barth B, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2017) 15:742–5. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13272_g, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strickley JD, Vence LM, Burton SK, Callen JP. Nivolumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Cutis. (2019) 103:224–6. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sato Y, Fujimura T, Mizuashi M, Aiba S. Lichen planus pemphigoides developing from patient with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. (2019) 46:e374–5. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14906, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okada H, Kamiya K, Murata S, Sugihara T, Sato A, Maekawa T, et al. Case of lichen planus pemphigoides after pembrolizumab therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. J Dermatol. (2020) 47:e321–2. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15461, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwon CW, Murthy RK, Kudchadkar R, Stoff BK. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. (2020) 6:1045–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.03.007, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Senoo H, Kawakami Y, Yokoyama E, Yamasaki O, Morizane S. Atezolizumab-induced lichen planus pemphigoides in a patient with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Dermatol. (2020) 47:e121–2. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kerkemeyer KLS, Lai FYX, Mar A. Lichen planus pemphigoides during therapy with tislelizumab and sitravatinib in a patient with metastatic lung cancer. Australas J Dermatol. (2020) 61:180–2. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13214, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buquicchio R, Mastrandrea V, Strippoli S, Quaresmini D, Guida M, Filotico R. Case report: autoimmune pemphigus vulgaris in a patient treated with Cemiplimab for multiple locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:691980. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.691980, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brenner S, Goldberg I. Drug-induced pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. (2011) 29:455–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ito M, Hoashi T, Endo Y, Kimura G, Kondo Y, Ishii N, et al. Atypical pemphigus developed in a patient with urothelial carcinoma treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. (2019) 46:e90–2. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schoenberg E, Colombe B, Cha J, Orloff M, Shalabi D, Ross NA, et al. Pemphigus associated with ipilimumab therapy. Int J Dermatol. (2021) 60:e331–3. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15405, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krammer S, Krammer C, Salzer S, Bağci IS, French LE, Hartmann D. Recurrence of pemphigus vulgaris under Nivolumab therapy. Front Med (Lausanne). (2019) 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00262, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clawson RC, Tabata MM, Chen ST. Pemphigus vulgaris flare in a patient treated with nivolumab. Dermatol Ther. (2021) 34:e14871. doi: 10.1111/dth.14871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. (2018) 310:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s00403-017-1790-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leonardi GC, Gainor JF, Altan M, Kravets S, Dahlberg SE, Gedmintas L, et al. Safety of programmed Death-1 pathway inhibitors among patients with non-small-cell lung Cancer and preexisting autoimmune disorders. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:1905–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.0305, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maeda T, Yanagi T, Imafuku K, Kitamura S, Hata H, Izumi K, et al. Using immune checkpoint inhibitors without exacerbation in a melanoma patient with pemphigus foliaceus. Int J Dermatol. (2017) 56:1477–9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13713, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1259. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01259, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaplan I, Hodak E, Ackerman L, Mimouni D, Anhalt GJ, Calderon S. Neoplasms associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus: a review with emphasis on non-hematologic malignancy and oral mucosal manifestations. Oral Oncol. (2004) 40:553–62. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.09.020, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen WS, Tetzlaff MT, Diwan H, Jahan-Tigh R, Diab A, Nelson K, et al. Suprabasal acantholytic dermatologic toxicities associated checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a spectrum of immune reactions from paraneoplastic pemphigus-like to Grover-like lesions. J Cutan Pathol. (2018) 45:764–73. doi: 10.1111/cup.13312, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McNally MA, Vangipuram R, Campbell MT, Nagarajan P, Patel AB, Curry JL, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus manifesting in a patient treated with pembrolizumab for urothelial carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. (2021) 10:82–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.012, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yatim A, Bohelay G, Grootenboer-Mignot S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Alexandre M, Le Roux-Villet C, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus revealed by anti-programmed Death-1 Pembrolizumab therapy for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis Suppurativa. Front Med (Lausanne). (2019) 6:249. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00249, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burzi L, Alessandrini AM, Quaglino P, Piraccini BM, Dika E, Ribero S. Cutaneous events associated with immunotherapy of melanoma: a review. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:3047. doi: 10.3390/jcm10143047, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strauss J, Heery CR, Schlom J, Madan RA, Cao L, Kang Z, et al. Phase I trial of M7824 (MSB0011359C), a bifunctional fusion protein targeting PD-L1 and TGFβ, in advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. (2018) 24:1287–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2653, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 interactions for cancer immunotherapy. Onco Targets Ther. (2012) 1:1223–5. doi: 10.4161/onci.21335, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Good-Jacobson KL, Szumilas CG, Chen L, Sharpe AH, Tomayko MM, Shlomchik MJ. PD-1 regulates germinal center B cell survival and the formation and affinity of long-lived plasma cells. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:535–42. doi: 10.1038/ni.1877, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ye Y, Jing Y, Li L, Mills GB, Diao L, Liu H, et al. Sex-associated molecular differences for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:1779. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15679-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stelkovics E, Korom I, Marczinovits I, Molnar J, Rasky K, Raso E, et al. Collagen XVII/BP180 protein expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin detected with novel monoclonal antibodies in archived tissues using tissue microarrays and digital microscopy. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2008) 16:433–41. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318162f8aa, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Krenacs T, Kiszner G, Stelkovics E, Balla P, Teleki I, Nemeth I, et al. Collagen XVII is expressed in malignant but not in benign melanocytic tumors and it can mediate antibody induced melanoma apoptosis. Histochem Cell Biol. (2012) 138:653–67. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0981-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Franzke CW, Bruckner P, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Collagenous transmembrane proteins: recent insights into biology and pathology*. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:4005–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400034200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsiogka A, Bauer JW, Patsatsi A. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. (2021) 101:3740. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shimbo T, Tanemura A, Yamazaki T, Tamai K, Katayama I, Kaneda Y. Serum anti-BPAG1 auto-antibody is a novel marker for human melanoma. PLoS One. (2010) 5:e10566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010566, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee JE, Reveille JD, Ross MI, Platsoucas CD. HLA-DQB1*0301 association with increased cutaneous melanoma risk. Int J Cancer. (1994) 59:510–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590413, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. The growing incidence of bullous pemphigoid: overview and potential explanations. Front Med (Lausanne). (2018) 5:220. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00220, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Verheyden MJ, Bilgic A, Murrell DF. A systematic review of drug-associated bullous pemphigoid. Acta Derm Venereol. (2020) 100:5716. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alpsoy E, Akman-Karakas A, Uzun S. Geographic variations in epidemiology of two autoimmune bullous diseases: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res. (2015) 307:291–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-014-1531-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. (2016) 39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, Wu J, Leung DYM, Moy AP, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 83:1255–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.