Abstract

The plant proliferation is linked with auxins which in turn play a pivotal role in the rate of growth. Also, auxin concentrations could provide insights into the age, stress, and events leading to flowering and fruiting in the sessile plant kingdom. The role in rejuvenation and plasticity is now evidenced. Interest in plant auxins spans many decades, information from different plant families for auxin concentrations, transcriptional, and epigenetic evidences for gene regulation is evaluated here, for getting an insight into pattern of auxin biosynthesis. This biosynthesis takes place via an tryptophan-independent and tryptophan-dependent pathway. The independent pathway initiated before the tryptophan (trp) production involves indole as the primary substrate. On the other hand, the trp-dependent IAA pathway passes through the indole pyruvic acid (IPyA), indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), and indole acetamide (IAM) pathways. Investigations on trp-dependent pathways involved mutants, namely yucca (1–11), taa1, nit1, cyp79b and cyp79b2, vt2 and crd, and independent mutants of tryptophan, ins are compiled here. The auxin conjugates of the IAA amide and ester-linked mutant gh3, iar, ilr, ill, iamt1, ugt, and dao are remarkable and could facilitate the assimilation of auxins. Efforts are made herein to provide an up-to-date detailed information about biosynthesis leading to plant sustenance. The vast information about auxin biosynthesis and homeostasis is consolidated in this review with a simplified model of auxin biosynthesis with keys and clues for important missing links since auxins can enable the plants to proliferate and override the environmental influence and needs to be probed for applications in sustainable agriculture.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03709-6.

Keywords: Epigentic, Concentrations, Yucca, IPyA, IAOx, IAM

Introduction

Auxins play an essential role in determining the response of the plant to the environment and in the maneuvers of adaptation to stressful conditions. Variation in auxin levels not only changes the plant phenotype, but also influences flowering and fruiting (Zhao 2018), grain development and grain filling process (Zhang et al. 2021), and sepal retention and development (Fatima et al. 2021). Symplastic communication and its association with local auxin biosynthesis suggest that root stem cells are essential players in activating the auxin biosynthesis process (Zhao 2018). Sustainable agriculture and changes in plant responses to climate change may facilitate the storage of information on auxin homeostasis and biosynthesis by identifying appropriate molecular manipulations for improved yield (Korver et al. 2018). Local auxin maintenance via biosynthesis to develop adventitious meristem and aerial meristem is reported (Wang and Jiao 2018; Nadzieja et al. 2018). Auxin production in diploid microsporocyte is necessary and sufficient for early stages of pollen development (Yao et al. 2018). Auxins are essential for plant development and are widely involved in cell division and elongation, tropisms, apical dominance, senescence, flowering, and stress response (Di et al. 2015). Evidence from various mutant investigations suggests that strict auxin homeostasis is necessary for plant growth and development. Recent research on auxin shows the role of auxin in the various developmental growths of plants.

The auxin can play an essential role in the opening and closing of the water lily (Ke et al. 2018). Auxin fine-tuning at the flower meristem terminus in gynoecium development plays a central role (Yamaguchi et al. 2017; Bai et al. 2018). Additionally, the specificity of tryptophan-dependent auxin responses is coordinated in wood formation (Brackmann et al. 2018). Seed size and starch synthesis in Pisum sativum are controlled by auxin concentration (McAdam et al. 2017a). The auxin amounts affects the leaf veins that in turn influences photosynthesis (Kneuper et al. 2017; McAdam et al. 2017b). Topical application of a minor amount of auxins results heat tolerance and shows changes in reproductive functions of rice plants (Zhang et al. 2018a).

Auxin biosynthesis, primarily Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis, takes place by multiple pathways, namely tryptophan (Trp)-dependent and -independent pathways, whereas the conversion of Trp to IAA via different pathways is named after its downstream intermediate, including indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPyA), and indol-3-acetamide (IAM) (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2018). Recently, analysis of sequencing data shows that the primary auxin biosynthesis pathway of the IPyA pathway in terrestrial plants shows similarity with green algae. This sequence similarity shows conservation of genes associated with auxin biosynthesis (Morffy and Strader 2020). Studies related to auxin biosynthesis over 70 years have still many missing links (Kasahara 2016). In the twenty-first century, extensive researches are performed to understand auxins, especially the biosynthesized IAA and its transport, and also factors associated with the local maxima/minima to maintain its homeostasis and morphogenetic programs for plant development. A significant number of known genes in auxin biosynthesis, transport, conjugation, and degradation are also studied. These genes are interconnected through the mechanism of feedback loops related to auxin as well as crosstalk with different phytohormone pathways (Qin et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2017a; Quint et al. 2016; Skalický et al. 2018).

Different types of auxins and the variable amounts across the plant kingdom

The nanomolar concentration (~ 10–80 ng/gfw) of auxins is sufficient for normal functioning but is influenced by abiotic stress (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 1) (Korver et al. 2018). Auxins are unevenly distributed in plants, biosynthesized, accumulated, and they in turn determine the final fate for proliferation.

Table 1.

Changes in the developmental profile of and Oryza sativa, Pisum sativum and Arabidopsis thaliana on mutation in TAA and YUCCA genes family

| Plant | Mutants | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa | taa1 | Lack of crown root development | Zhang et al. (2018a, b) |

| oscow1 | Water deficiency in the plant | Woo et al. (2007) | |

| Three-fold lower in root-to-shoot ratio | |||

| Three-fold lower transpiration rate | |||

| OsYUCCA1 | Abnormal growth in leaf, root and stem development | Yamamoto et al. (2007) | |

| 2.5-fold increase in IAA level | |||

| Gravitropism disturbance | |||

| Induced hairy root production | |||

| OsYUCCA1antisense | Dwarfism in shoot elongation | Yamamoto et al. (2007) | |

| Inhibition in root formation and elongation | |||

| fish bone(fib) | Small leaves with large lamina joint angles, | Yoshikawa et al. (2014) | |

| Abnormal vascular development and organ identity, | |||

| Small panicles, | |||

| Defects in root development and two-fold reduction in internal IAA levels | |||

| Change in polar auxin transport activity and auxin sensitivity | |||

| Pisum sativum | tar2-1 | Seed wrinkling due to impaired starch synthesis | McAdam et al. (2017a) |

| 1.5-fold reduced starch content | |||

| 60% reduction in seed size | |||

| PsYUC1(crd) | 20% reduction in minor vein density | McAdam et al. (2017b) | |

| Significant reduction in leaf gas exchange | |||

| 50% and 80% reduction in IAA and IAAsp level respectively, in the apical tissue | |||

| Petunia | floozy(fzy) | Fail to develop secondary veins in leaves and bracts | Tobeña-Santamaria et al. (2002) |

| Decreased apical dominance in the inflorescence | |||

| Zea mays | sparse inflorescence1(spi1) | 50% reduced of branches number | (Gallavotti et al. 2008) |

| An eight-fold decrease in spikelet number | |||

| 10% reduction in plant height | |||

| 7% reduction in leaf number | |||

| Reduction in kernels production of over the tip of ears | |||

| Reduction in kernel number | |||

| Fewer spikelet pair | |||

| Defective apical inflorescence meristem | |||

| vanishing tassel2 (vt2) | 50% reduction in plant height | Phillips et al. (2011) | |

| 35% reduction in leaf number | |||

| Significant reduction in tassel length, ears length, branch number, kernel number, spikelet number and ears number | |||

| Arabidopsis thaliana | SUPERMAN (sup) | Auxin accumulation, at the boundary between whorl 3 and 4 due to auxin transport | Xu et al. (2018) |

| Auxin reduction in the center of the floral meristem due to inactivation of YUC1 and YUC4 | |||

| taa1 | Disrupts root hair elongation under low phosphorus | Bhosale et al. (2018) | |

| yuc4 | Reduced floral organ size | Xu et al. (2018) | |

| yuc1yuc4 | Defects in all four whorls of floral organs | Cheng et al. (2006), Xu, et al. (2018) | |

| No functional reproductive organs were ever observed | |||

| Flowers in lacked specific floral organs | |||

| Fewer veins in leaves than wild type | |||

| Decreased numbers of stamen and carpel | |||

| Reduction in floral organ size | |||

| yuc1yuc4yuc6 | Floral defects in all four whorls | ||

| yuc1yuc2yuc4 | |||

| yuc1D | IAA levels were not affected | Mashiguchi et al. (2011) | |

| IAA-Glu levels increased by 6.8 time | |||

| yuc1yuc4yuc6yuc10yuc11 | Absence of hypocotyls and root meristem | Cheng et al. (2006), Wang et al. (2015) | |

| Disruption in embryogenesis and auxin biosynthesis | |||

| lacked a hypophysis (cells that later develop into a root meristem) | |||

| yuc1yuc4yuc10yuc11 | Fail to make the basal part of the embryo | Cheng et al. (2007) | |

| yuc1yuc2yuc4yuc6 | Inflorescence meristem was often very small | Cheng et al. (2006), Mashiguchi et al. (2011) | |

| No flower buds were visible except for some cylinder-like structures at early stages of development | |||

| Produce every type of the floral organ, but not every flower had all types of organs | |||

| The level of IPA increased 1.5 times | |||

| yuc1 yuc2 yuc6 | The level of IPA was increased significantly (1.8 times) in the buds | Mashiguchi et al. (2011), Won et al. (2011) | |

| Elevated levels of IPA | |||

| yuc2yuc6 | Shorter stamens | Cheng et al. (2006), Yao et al. (2018) | |

| The late anthers of maturation rarely produced any pollen | |||

| Microspore development arrests before PMI (pollen mitosis I) and fail to produce viable pollen | |||

| yuc3 yuc5 yuc7 yuc8 yuc9 | A very severe auxin-deficient phenotype in roots | Chen et al. (2014), Tsugafune et al. (2017) | |

| Very short and agravitropic roots | |||

| YUC6ox | Elongated hypocotyls and petioles | Mashiguchi et al. (2011) | |

| Root growth inhibition | |||

| Enhanced lateral root and adventitious root formation | |||

| IPA levels were 33% reduced and increased IAA, IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu level |

Auxins facilitate the dynamic changes in translational and transcription activities. The role of auxin is an essential chemical for plant maintenance and proliferation, embryogenesis, and organogenesis, playing a role in various tropisms and gametes formation (Ke et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018). Auxin synthesized in young leaves and roots (Ljung et al. 2005), shoot tip and root tip (Liu et al. 2017b) is transported to the required location via the polar auxin transport (PAT) mechanism (Liu et al. 2017b; Ljung et al. 2001, 2005; Solanki and Shukla 2015). Three active forms of auxin have been identified in the plant kingdom: phenyl-acetic acid (PAA), 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid (4-CL-IAA), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA).

The phenyl-acetic acid (PAA) biosynthesis in Pisum sativum uses the substrate aromatic amino acid the phenylalanine using phenyl-pyruvate pathway (Cook et al. 2016). PAA targets the auxin-responsive gene in the same way as IAA targets TIR1/AFB (Transport Inhibitor Response 1/Auxin Signaling F-box proteins) (Sugawara et al. 2015). Quantification of IAA and PAA using basic paper chromatography and gas–liquid chromatography techniques in shoots of tomato, sunflower, pea, barley, and corn showed the IAA:PAA ratio as 1:6, 1:4, 1:5, 1;4, and 1:5 respectively (Sauer et al. 2013; Simon and Petrasek 2011). PAA was higher in younger shoots than in mature shoots (Simon and Petrasek 2011).

Auxin derivatization and the discovery of 4-Cl-IAA in Pisum sativum (Karcz and Burdach 2002) and its absence in Arabidopsis thaliana are reported (Tivendale et al. 2012). The unusual formation of 4-Cl-IAA is associated with the chlorination of tryptophan, leading to 4-Cl-trp and 4-Cl-IAA (Tivendale et al. 2012). This conversion is processed by aminotransferases enzymes (Tivendale et al. 2012; Phillips et al. 2011). The indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) was discovered in synthetic form which showed root initiation in different plant species (Strader and Bartel 2011). Endogenously, IBA has been found in potato plants (Sauer et al. 2013). The IBA formation is validated in cypress, pea, carrot, maize, Arabidopsis, and tobacco. In Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings, 25–30% of the IBA accounts for total Auxin concentration (Sauer et al. 2013). IBA is the modified and storage form of IAA (Supplementary Table 1). Structurally IBA contains two additional CH2 groups in the side chain compared to the IAA (Strader and Bartel 2011; Zolman et al. 2008). IBA applications exogenously to plants could induce rooting (Strader and Bartel 2011). The isn mutant shows defective root formation compared to the mutant of IAA, which suggests that IBA plays an important role in the rooting initiation (Rampey et al. 2004; Zolman et al. 2008). Thus IBA role in the root initiation was validated independently by Rampey et al. and Zolman et al., providing selective responses of the auxin IBA.

Historically speaking, IAA was first discovered by Haagen-Smit et al. (1946) in Zea mays. He provided crucial evidence for its important role of auxin in plant growth and development. In this review, we focus on IAA and provide information on connective links wherein different modes of auxin formation for plant maintenance are given. An effort has been made to tabulate and provide precise references for auxin biosynthesis. This work would enable the reader to identify the scientific gaps for auxin biosynthesis.

Quantitatively, the amount of IAA in plants varies at different stages of growth. In addition, the amount of IAA in root, shoot, and stem was measured by GC/MS, GC–SIM–MS HPLC–MS/MS, and HPLC techniques. Detailed studies of IAA (ng/gfw) grown at different temperatures are reported (Zhao et al. 2002). IAA amount was also analyzed on different days in the presence or the absence of tryptophan (trp) (Normanly et al. 1993). Novak et al. (2012) analyzed the effect of post-vernalization (Supplementary Table 1). Immature seeds of Helleborus niger show the highest concentration of 1300 ng/gfw IAA (Pencik et al. 2009). The 18-day-old root of individual plants like Tropaeolu majus showed 119 ng/gfw versus 17.5 ng/gfw for Pisum sativum (Ludwig-Muller and Cohen 2002; Quittenden et al. 2009). These evidences provide dynamic nature of auxins biosynthesis and that these could be modified by giving various treatments.

Changes in auxin concentration observed after germination show a close association with plant requirements. In the model plant, A. thaliana IAA, vernalized seeds show 74.8 ng/gfw and 61 ng/gfw in 5-day- and 2 ng/gfw in 12-day-old plant (Supplementary Table 1). Detailed data for different ages of seedlings of A. thaliana given in (Supplementary Fig. 1) show an interesting profile for IAA accumulation (Novak et al. 2012). This study provides the quantities of IAA after germination, also IAA synthesized by the meristematic tissues is distributed and shows reduction along with the growth of plants, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Interestingly, the increase after 4 days is followed by a reduction on 7 days post germination as could be seen by a 2.5-fold is seen. It may be noted that the amounts show a surge to 20 ng/gfw, 61 ng/gfw, and 42 ng/gfw till fourth day followed by a reduction and a basal level for 9 days, 11 days, 12 days, 14 days, and 22 days post germination where the amounts seen are 12 ng/gfw, 16 ng/gfw, 2.1 ng/gfw, 11.2 ng/gfw, and 15 ng/gfw, respectively. These data are interesting as they provide factual quantification of IAA in model plants Arabidopsis.

Quantitatively estimated amount of IAA in different plants is reported in Oryza sativa (Kojima et al. 2009), Helleborus niger (Pencik et al. 2009), Pisum sativum (Quittenden et al. 2009), and Tropaeolum majus (Ludwig-Muller and Cohen 2002). The amount of IAA present in different plants and organs is low, with a maximum concentration in immature seed or the pericarp. Varying amounts of IAA may be related to different rates of IAA biosynthesis. Changes in auxin concentration determine the gradient in the root, shoot, and organs where local auxin concentration plays a vital role in developmental outcomes. The auxin biosynthesis is primarily processed through an tryptophan-independent and tryptophan-dependent pathway, and its homeostasis via ester and amide conjugates is consolidated and described step by step below.

Important biosynthetic pathways of auxin biosynthesis

Biosynthesis of IAA by tryptophan-dependent pathway

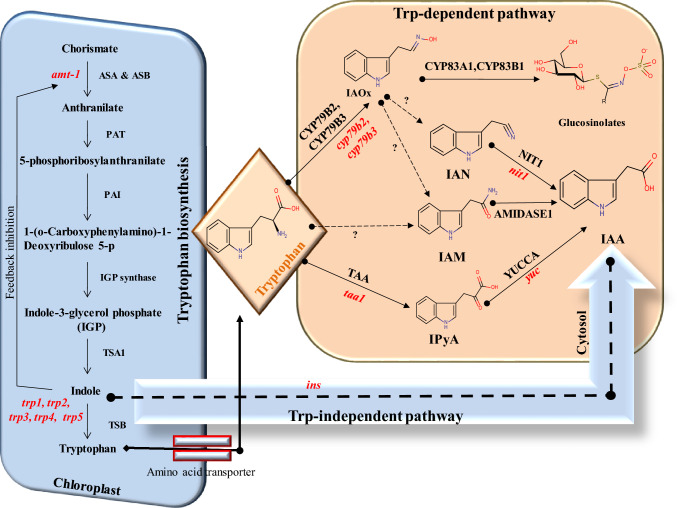

The IAA precursor tryptophan is produced in chloroplasts (Fig. 1) and it is transported to the cytoplasm. Here, the IAA is produced. The details of subcellular auxin location of auxin biosynthesis pathways are given by Casanova-Saez et al. (2021) and Skalický et al. (2018). Quantitatively, a 13-day-old A. thaliana was grown under low light and high light conditions without tryptophan. This result showed only 25 ng/gfw and 21 ng/gfw IAA accumulation (Normanly et al. 1993). In plants, tryptophan biosynthesis in the chloroplast is initiated by two enzymes ASA and ASB (anthranilate synthase alpha and beta, respectively). These convert chorismate to anthranilate. The anthranilate formed by the enzyme phosphoribosyl anthranilate transferase is than converted to 5-phosphoribosyl anthranilate. This moiety is used as a substrate by the enzyme phosphoribosyl anthranilate isomerase. Once it reaches indole, it shows negative indole feedback and competes with the chorismate for active sites. The final step in tryptophan synthesis is the conversion of indole to tryptophan. The biocatalyst tryptophan synthase performs the conversion (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2) (Barczak et al. 1995). Tryptophan undergoes further enzymatic catalysis to produce indole pyruvic acid (IPyA), indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), and indole acetamide (IAM) intermediates. IAM and IPyA produce IAA through the catalytic activity of the enzymes amidase1 and YUCCA (YUC), respectively. However, IAOx undergoes multiple reactions to produce IAM/IAN/glucosinolates (Fig. 1). The quantification of the IPyA and IAM biomolecules yields 13.1 ng/gfw and 1.6 ng/gfw, respectively, in 7-day-old A. thaliana seedlings. The reported level of IAOx is 1.7 ng/gfw, IAM is 9.9 ng/gfw, and IPyA is 3.8 ng/gfw in 14-day-old seedlings (Supplementary Table 3). The proof for the chorismate to anthranilate is by anthranilate synthase (Fig. 1) involving the amt-1 mutant. The anthranilate synthase increases the production of auxin conjugates (Niyogi and Fink 1992) (Supplementary Table 4). A three-fold increase in soluble tryptophan is noted in a trp-4 trp-5 mutant (Li and Last 1996). Feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase could accumulate blue fluorescent anthranilate compounds in the trp-1 mutant (Rose et al. 1992, 1997). Another prominent mutant trp2 and trp3 in A. thaliana shows nineteen to thirty-six times higher IAA accumulation (Supplementary Table 4) (Last et al. 1991; Normanly et al. 1993). IAA biosynthesis orange pericarp (orp) mutant Zea mays shows an auxotrophic nature of the mutant. It shows a 50-fold increase in IAA conjugates caused by β-gene duplication (Wright et al. 1991). Interestingly, there is evidence for the role of sugar on tryptophan during maize kernel development. Another mn1 mutant disrupts tryptophan biosynthesis (Le et al. 2010). IAA formation from tryptophan occurs by three stable intermediates associated with three different pathways of tryptophan to IAA conversion via IPyA, IAOx, and IAM.

Fig. 1.

Trp-dependent and -independent pathways for auxin biosynthesis (Solid arrows are used to demarcate pathways with identified substrates and enzymes, and dashed arrows are product only). The red color and italics text indicate the mutant form. Abbreviations: Includes Anthranilate synthase α (ASA), Anthranilate synthase β (ASB), Phosphoribosylanthranilate transferase (PAT), Phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase (PAI), Tryptophan synthase α (TSA), Tryptophan synthase β (TSB), Indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), Indole-pyruvic acid (IPyA), Indole acetamide (IAM), Indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN), Tryptophan aminotransferase of Arabidopsis (TAA), Nitrolases family (NIT1), anthranilate synthase (amt-1), tryptophan synthase 1 (trp1), tryptophan synthase 2 (trp2), tryptophan synthase 3 (trp3), tryptophan synthase 4 (trp4), tryptophan synthase 5 (trp5), tryptophan aminotransferase of arabidopsis (taa1), YUCCA (yuc), cytochrome P450 (cyp79b2 and cyp79b3), Nitrilase family (nit1) and indole synthase (ins)

Tryptophan to IAA biosynthesis involving IPyA sub-route

The IPyA sub-route from tryptophan to IAA is highly conserved (Dai et al. 2013; Mashiguchi et al. 2011; Won et al. 2011; Stepanova et al. 2011; Zhao 2018), and this is functionally characterized in A. thaliana (Dai et al. 2013; Mashiguchi et al. 2011; Stepanova et al. 2011; Won et al. 2011), Oryza sativa (Kakei et al. 2017; Woo et al. 2007; Yamamoto et al. 2007; Yoshikawa et al. 2014), Zea mays (Gallavotti et al. 2008; Phillips et al. 2011), Brachypodium distachyon (Pacheco-Villalobos et al. 2013), petunias (Tobena-Santamaria et al. 2002), Marchantia polymorpha (Eklund et al. 2015), and many other species (Liu et al. 2012, 2014). Increased auxin biosynthesis via the TAA/YUC pathway provided evidence for crown root development via the YUC-Auxin-WOX11 module in rice YUCCA (Zhang et al. 2018b). Tryptophan is converted to IPyA by the enzyme TAA1 (Tryptophan Aminotransferase of Arabidopsis 1) (Fig. 1). Recently, phosphorylation of TAA1 on threonine at position 101 in the presence of cofactor pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) was identified as an on/off switch for auxin biosynthesis (Wang et al. 2020). The increase in TAA1 production shows an increase in IPyA formation (Mashiguchi et al. 2011). However, this does not show a simultaneous increase in IAA. This exciting finding suggests a role for the YUC enzyme in controlling IAA production. Multiple mutations in the YUC gene show developmental changes associated with auxin biosynthesis (Table 1). The cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (cngc2) mutant showed reduced gravitropism due to auxin signaling defects. A loss-of-function mutation at TAA1 and YUC6 showed a suppressed phenotype of the cngc2 mutant. These data suggest the close relationship between CNGC2 and the TAA-YUC-dependent auxin biosynthesis pathway (Chakraborty et al. 2021). The details of YUC in the IPyA pathway of auxin biosynthesis were succesfully found using reverse genetics and its expression pattern in A. thaliana (Table 1). The YUC gene in A. thaliana (Dai et al. 2013) is associated with the generation of a transcriptome encoding a flavin monooxygenase-like enzyme (Mano and Nemoto 2012). This enzyme localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (Staswick et al. 2005) shows interesting feature where specific combinations of eleven predicted YUC genes, resulted in developmental and diverse aspects of plant growth. The single, double, and multiple yuc mutants show decreased IAA production (Table 1). The SUPERMAN (sup) mutant was reported by Xu’s group (Xu et al. 2018). It showed reduced activity of YUC1 and YUC4 with concomitant increase in auxin levels, with facilitation of stem cells preservation floral. The yuc1,4 mutation showed defects in all four whorls and no functional reproductive organ. The triple mutant of yuc1,4,6 and yuc1,2,4 also has a flower defect (Table 1) (Cheng et al. 2006). The yuc1,2,4,6 lacks a flower bud and exhibits a reduced cylindrical structure at an early stage of its development. Interestingly, this mutant produces all types of floral organs, but not all flowers have functional organs (Cheng et al. 2006; Mashiguchi et al. 2011). The yuc1,6 mutant exhibited shorter stamens, late anther maturation and microspores arrested before pollen mitosis (Cheng et al. 2006; Yao et al. 2018). The yuc3,5,7,8,9 mutant produces concise, agravitopic roots formation (Table 1) (Cheng et al. 2007; Tsugafune et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2014). The yuc6ox inhibits root growth and enhances lateral and adventitious root formation (Mashiguchi et al. 2011). The yuc4,6,10,11 mutant shows the absence of root meristem and the yuc1,2,4.6 mutant shows a small inflorescence meristem (Mashiguchi et al. 2011; Cheng et al. 2006). The yuc1,2,4,6 mutant shows a 1.5-fold increase in IPyA, while yuc1,2,6 shows a 1.8-fold increase in IPyA level in the bud (Mashiguchi et al. 2011; Won et al. 2011). Trp-dependent IPyA pathways are found in many plant species and depend on TAA1 and YUC enzymatic reactions. While TAA1 phosphorylation is an essential feature for the initiation of IAA biosynthesis, the concentration of different YUC genes is responsible for different developmental changes.

Tryptophan to IAA biosynthesis involving IAOx sub-route

Tryptophan is converted into the IAOx intermediate using the enzymes cytochrome p450, CYP79B2 and CYP79B3 (Fig. 1) (Zhao et al. 2002). Mutation study on IAOx formation shows impaired IAA biosynthesis, besides IAOx, and could be converted into three different products, such as IAN (auxin precursor) (Bak et al. 1998), IAM (auxin precursor) (Pollmann et al. 2002), and glucosinolates (plant defense compounds) (Mikkelsen et al. 2004). The IAOx pathway of auxin biosynthesis shows the conversion of tryptophan to IAN, which is converted to IAA by enzyme nitrilases. Mutation study in A. thaliana for nit1 shows insensitivity to IAN and negatively influences the conversion of IAN to IAA (Normanly et al. 1993). The NIT1ox mutants show shorter primary roots, increased number of lateral roots, 2.3 times more IAA, and 3.5 times more IAN (Lehmann et al. 2017). Quantification of IAN in different parts of the plant has been assessed in Supplementary Table 5 (Ribnicky et al. 2002; Park et al. 2003; Pencik et al. 2018), and accumulation is maximum in the young embryo seedlings. The maximum amount of IAN found in a 7-day-old seedling of A. thaliana compared with Avena sativa (Supplementary Table 5). IAOx can also produce active auxin via the IAM pathway (Normanly et al. 1997; Korasick et al. 2013). It mainly relies on the NIT1 enzymatic reaction to contribute to the active auxin pool. These pathways are also crucial for the development plant immunity through the production of glucosinolates.

Tryptophan to IAA biosynthesis involving IAM sub-route

The IAM intermediate can synthesize IAA directly by tryptophan or via IAOx intermediate (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). This is illustrated by the study of cyp79b2 cyp79b3 mutants, feeding on IAOx producing IAM (Fig. 1) (Sugawara et al. 2009). A decrease in the level of IAM leads to a decrease in the IAA (Hull et al. 2000). These observations suggest that IAM is also produced by involving the IAOx intermediate. IAM is converted into active IAA by the enzymatic reaction of the enzyme amidase1 (Pollmann et al. 2003). The above mechanisms also highlight that IAM is produced in plants by IAOx-dependent or IAOx-independent intermediates (Zhao et al. 2001). The IAM pathways have been less studied than the IPyA and IAOx pathways of trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis. Studies on tryptophan mutants show that the concentration of auxin in the plant is maintained in its absence through trp-independent pathways.

Biosynthesis of IAA by tryptophan-independent biosynthesis

Normanlly et al. (1993), using a labeled tryptophan precursor, demonstrated that IAA is not only produced by the trp-dependent pathway but also by an alternative trp-independent pathway (Fig. 1) (Wang et al. 2015; Normanly et al. 1993). IAA is produced directly from indole-3 glycerol (IGP), or indole found in the trp-independent pathway (Normanly et al. 1993). Indole synthase (INS) localized in the cytosol catalyzes the production of IAA in the trp-independent pathway (Fig. 1) (Wang et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2008). The null mutation causes a decrease in IAA activity, affects early embryonic development. The isotope labeling experiment could not provide much information about the trp-independent pathway because IAA production is highly localized. Although auxin is produced from tryptophan, the IPyA precursor is more pronounced than tryptophan. Thus, differences between tryptophan and IAA by isotope experiment are reported by authors that can only be explained by the trp-independent pathway (Normanly et al. 1993). The critical evaluation of evidence of the trp-independent pathway has been explained by (Nonhebel 2015). The IAA synthesized via this pathway is responsible for the development of the axis (apical and basal) and maintenance of plant growth (Wang et al. 2015). The change in the trp-independent and trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis pathways of the plant mainly depends on the environmental factors and growth phase of the plant. Auxin biosynthesis takes place at the root tip, shoot tip, and leaf. The plant maintains the auxin pool through auxin homeostasis, which is mainly processed by the inactive and storage conjugates of auxin via an ester and amide-related process. The hydrolysis of conjugates provides the immediate active auxin for plant growth and development.

Evidences of the role of epigenetic and transcriptional factors in the regulation of auxin biosynthesis

Several transcription factors and epigenetic regulators have been identified over the past decade. These play central roles in auxin homeostasis by controlling auxin production during developmental processes and environmental fluctuations (Casanova-Sáez et al. 2021). An understanding is developed regarding the epigenetic machinery coordinated toward auxin biosynthesis and inactivation for auxin homeostasis in plants (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2019). The auxin is located at the transcriptional level and its role is to inhibit the transcription factors AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs (ARFs). Briefly, genes transcribing ARFs could be divided into three regions: (1) N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD), (2) middle region (MR), and (3) C-terminal dimerization domain (CTD). DBD and CTD are conserved, and MR is not conserved in ARFs (Okushima et al. 2005; Shen et al. 2010; Guilfoyle and Hagen 2007; Li et al. 2016). The functionally important MR provides a model for the direction of transcriptional activation and repression (Shen et al. 2010; Ulmasov et al. 1997). The AuxRE is a promoter sequence of the early auxin-responsive genes in the plants. These transcriptional processes of auxin on the AuxRE to their regulatory regions in auxin-responsive genes are modulated through epigenetic processes and maintain the auxin maxima/minima to balance metabolism, transport, and signaling (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2019). In Arabidopsis thaliana, nearly 130 genes facilitate by modulating a few groups: (1) enzymes catalyzing chemical modifications of DNA or (2) histones, (3) Polycomb Group (PcG) and Polycomb-related proteins, (4) chromatin remodelers, and (5) protein and RNA molecules that participate in RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) (Rothbart and Strahl 2014; Leyser 2017; Pikaard and Mittelsten Scheid 2014). Auxin affects chromatin dynamics. The ARF–Aux/IAA–TPL complex binds to the AuxRE and recruits histone deacetylase complex (HDAC), promoting chromatin compactness (Yamamuro et al. 2016). The evidences also confirm that in the presence of auxin, degradation of Aux-IAA is observed, leading to the recruitment by ARFs of histone acetyltransferases. It influences the opening of chromatin in the target gene (Yamamuro et al. 2016). There are evidences for the role of ARF5 in the chromatin-remodeling ATPases BRAHMA (BRM) and SPLAYED on genes involved in flower primordium initiation, such as FILAMENTOUS FLOWERING, TARGET OF MONOPTEROS 3, and AINTEGUMENTA. This process of chromatin unlocking initiates binding of transcription factors and histone acetyltransferases (Wu et al. 2015). On the other hand, ARF3 and ARF4 repress SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (STM) via histone deacetylation, which is involved in flower initiation at the reproductive stage meristem (Chung et al. 2019). Auxin biosynthesis is controlled by inhibitory feedback mechanisms and maintains homeostasis in the cell (Qin et al. 2019; Skalický et al. 2018). Local site and time- or tissue-specific auxin requirements depend on dynamic “on” and “off” switches of the biosynthetic machinery, which are driven by epigenetic processes (Casanova-Sáez et al. 2021). Studies of the histone repressive mark H3K27me3 are done where the differential pattern of this variant in genes plays a crucial role in auxin biosynthesis, transport, and signaling between meristematic and differentiated cells and between leaves and derived callus (He et al. 2012). The YUC1 and the YUC4 play a key role in early auxin-mediated de novo root regeneration and showed a correlation with decrease levels of H3K27me3 around their promoter regions (Chen et al. 2016). Additionally, Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN 1 (LHP1), is found to be directly involved in YUC gene promoters and maintain their expression as needed (Rizzardi et al. 2011).

Transport of auxins across the plants

Plants synthesize auxin primarily at the shoot tip of a plant necessary for whole plant organogenesis, another hormone synthesis. This is transported by phloem or cell-to-cell flow (Feraru and Friml 2008; Petrásek and Friml 2009). This cell-to-cell flux of auxin transportation, its distribution asymmetrically, produces a gradient between the cells. Since 1970s, the chemiosmotic hypothesis was formulated by Ruberry, Sheldrake, and Sheldrake, in the twenty-first century (Rubery and Sheldrake 1974; Abel and Theologis 2010). The cytosol has a higher pH (7) rather than extracellular space (5.5). This pH gradient enables dissociation of IAAH in the cell (Vieten et al. 2007; Kramer and Ackelsberg 2016). The IAAH complex from the extracellular space to the cell which is high pH (alkaline)—to dissociate the IAAH complex and to generate IAA− and H+ ions. The IAA− molecule is charged, so it cannot be transported passively out of the cell. This is called auxin trapping (Vieten et al. 2007; Vanneste and Friml 2009; Kramer and Ackelsberg 2016). Auxin transport through transmembrane protein involvement is essential for the maintenance of local auxin concentrations. It is regulated by several transporters, including PIN-FORMED (PIN) transporters (Adamowski and Friml 2015), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (Zhu et al. 2016), and AUXIN1 (AUX1)/LIKE AUXIN1 (LAX) importers (Tan et al. 2021). The trapped auxin is transported by a carrier protein. The PIN proteins and the process are active and directional. So the auxin flow direction depends on PIN proteins’ localization on the plasma membrane. These proteins are divided into two subfamilies based on localization: plasma membrane localized and endoplasmic reticulum (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2018). The PLETHORA genes PLT3, PLT5, and PLT7 maintain the high levels of PIN1 protein expression at the periphery of the meristem (Prasad et al. 2011). The domains of PLT expression required for spiral phyllotaxis are involved with modulation of local auxin biosynthesis in the central region of the shoot apical meristem (SAM), which underlies phyllotactic transitions (Pinon et al. 2013).

The plasma membrane contains influx carrier AUX1(LAX) protein (Vieten et al. 2007), facilitating in the transport of dissociated IAA− (via PIN protein into extracellular space or no transported IAA into the cell). It has been reported that AUX1 is always located at the opposite side of the PIN1 on the same cell (Reinhardt et al. 2003). This polar distribution function of auxin requires evidence. However, the arrangement of AUX1 and PIN1 receptors could facilitate unidirectional auxin flow. AUX/LAX sequences identified broadly within the Viridiplantae provide evidences for the role of auxin efflux machinery in plant evolution (Swarup and Péret 2012). These protein families are reported to have two subfamilies: one has the AUX1 and LAX1 genes, and another has the LAX2 and LAX3 genes (Yue et al. 2015).

The MDR/PGP transporter (multi-drug-resistant/P-glycoprotein) (Vieten et al. 2007) belongs to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein family. The Arabidopsis thaliana abcb1 mutants showed significantly lower auxin transport and enhanced auxin-deficient phenotype, such as altered reproductive structures (Blakeslee et al. 2007). The functional analysis of ABCB gene expression levels with polar auxin transport in carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus L.) genotypes enables to provide evidence for polar auxin transport in the adventitious rooting of stem cuttings (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2018). The ABC protein family has essential role in auxin efflux and influx. The PGP transporter asymmetrically is located on the cell membrane. There the PGP1 is responsible for auxin efflux and PGP4 for influx (Vieten et al. 2007; Geisler et al. 2005; Santelia et al. 2005). These constitute prominent protein families of transporters (Verrier et al. 2008; Lane et al. 2016).

The Arabidopsis INDETERMINATE DOMAIN (IDD) transcription factors, IDD14, IDD15, and IDD16, are involved in auxin biosynthesis and transport (Cui et al. 2013). The mutants (gain-of-function) IDD genes showed small and transversally down-curled leaves, whereas mutants (loss-of-function) showed pleiotropic phenotypes in aerial organs. The altered leaf shape flower development, fertility, and plant architecture and defects in gravitropic responses show impact on vegetative and reproductive systems. The IDD genes target YUC5, TAA1, and PIN1 and promote auxin biosynthesis and its transport (Cui et al. 2013). This suggests important roles of IDD—roles in the auxin accumulation, responsible for organ morphogenesis and gravitropic responses in plants.

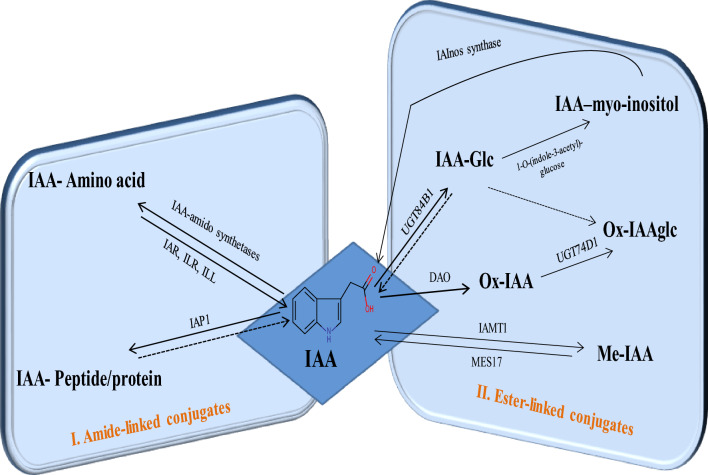

Evidenced of stored auxins in inactive form and its utilization by plants

Auxins are available in small amounts in free, inactive, and storage forms in the plants. Its concentration at a cellular level depends on the combined result of its transport, biosynthesis, and assimilation using pathways of IAA, involving oxidation and conjugation (Casanova-Sáez et al. 2022). The inactivation of auxin plays a vital role in plant development, for several enzymes have been implicated in auxin inactivation (Hayashi et al. 2021). The IAA-glucose, an auxin conjugate, is 1.5 times higher in amount than non-dormant seed of A. thaliana after 6 h of water imbibition (Bai et al. 2018). These results suggest that auxin conjugates could undergo hydrolysis to IAA by hydrolysis (Ljung et al. 2001; Bai et al. 2018). The working model is associated with the conjugated auxins that are maintained. These could provide auxin pool by conversion to active auxin (Woodward and Bartel 2005; Bajguz and Piotrowska 2009; Ludwig-Muller 2011). Free IAA accounts for 25% of the total amount of IAA in the plant. The IAA (~ 75%) is present in conjugate form (Ludwig-Muller 2011). The interesting finding on the conjugates on auxin homeostasis shows temporary storage and permanent inactivation of auxin (LeClere et al. 2002). The conjugated auxins present in the seed (Bai et al. 2018) are essential, and the degradation pathway is understood (Korasick et al. 2013). IAA is selectively conjugated with a different protein, amino acid, and sugar (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 6 and 8). This includes broadly two types of conjugates, namely ester-linked and amide-linked, reviewed in details.

Fig. 2.

IAA assimilation post-synthesis, I. Amide-linked II. Ester-linked conjugates. Solid arrows indicate pathways with identified enzymes and dashed are possible multiple steps. Abbreviations: includes UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGT84B1 and UGT74D1), IAA attached to a protein (IAP1), IAA carboxymethyltransferase1 (IAMT1), IAA-Leucine Resistant1 (ILR 1), IAA–Alanine Resistant 3 (IAR 3), METHYL ESTERASE 17 (MES17) and Dioxygenase for auxin oxidation (DAO)

Ester-linked IAA conjugates

There are evidences for the availability of auxins by simple hydrolysis of ester-linked conjugates leading to an increase in bioactive auxin pool (Woodward and Bartel 2005). There are four different types of IAA-ester conjugates characterized in A. thaliana. These include IAA-glucose (IAA-Glc), ox-IAA, methyl-IAAester (MeIAA), and oxIAA-glucose (OxIAA-Glc) (Supplementary Table 6). Among these four ester-linked conjugates, Ox-IAA-Glc content amount is maximum, followed by IAA-Glc, Ox-IAA, and MeIAA conjugates in A. thaliana. Additionally, some non-specific IAA-esters are also found in A. thaliana (Normanly et al. 1993; Tam et al. 2000) and Nicotiana tabacum (Sitbon et al. 1993). The details are tabulated and given in Supplementary Table 6. Among, ester-linked IAA-conjugated moieties, OxIAA-Glc form 688.9 ± 192.2 (ng/gfw), are present in 7-day-old seedlings of A. thaliana (Kai et al. 2007). The development of ester-linked conjugates of IAA took place mainly using three different enzymes, namely UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT), IAA carboxyl methyltransferase 1 (IAMT), and Dioxygenase for auxin oxidation (DAO).

The UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) family catalyzes the transfer of uridine-diphosphate-activated monosaccharides to different compounds, such as anthocyanins (Yonekura-Sakakibara et al. 2012), cell wall components (Lin et al. 2016), fatty acids (Rocha et al. 2016), flavonoids (Liet al. 2018), glucosinolates (Grubb et al. 2014), and phenylpropanoids (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021; Sinla-padech et al. 2007). It has been studied in detail in A. thaliana, where more than 100 UGT proteins are identified (Yuet al. 2017). These are grouped based on the function in different categories. This includes A-N group (Li et al. 2001; Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2017), group L contained the UGTs (UGT84B1, UGT74E2, and UGT74D1) responsible for glycosylation of IAA (Fig. 2) (Tanaka et al. 2014). UGTs could in turn regulate the metabolism of different phytohormones by glycosylation of the bioactive form. UGT71B6 (abscisic acid), UGT73C5 and UGT73C6 (brassinosteroids), UGT85A1, UGT76C1 and UGT76C2 (cytokinins), UGT76E1 (jasmonic acid), and UGT89A2 and UGT76D1 (salicylic acid) are evidenced (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021). In A. thaliana, IAA linkage to glucose is performed by the enzyme UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGT84B1) (Aoi et al. 2020; Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021). The most abundant inactive IAA form is the IAA-glucose (IAA-glc) conjugate (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021). The study of recombinant UGT84B1, UGT84B2, UGT75B1, UGT75B2, and UGT74D1 was used to validate the glycosylate IAA, and other auxins. These included indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), and naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) in vitro (Jackson et al. 2001; Jin et al. 2013). The UGT84B1 showed the most robust IAA glycosyltransferase activity (Jackson et al. 2001). The overexpression showed higher levels of IAA and IAA-glc and phenotype of auxin accumulating mutants example wrinkled and curling leaves (Jackson et al. 2002). IAA-Glc conjugates to active IAA via IAA-myoinositol (Fig. 2) and IAA-Glc to IAA-myoinositol are catalyzed by I-O-(indole-3-acetyl)-glucose. The conversion of IAA-myoinositol to IAA is catalyzed by I-O-(indole-3-acetyl)-glucose:myo-inositol indoleacetyl transferase (IAInos synthase) (Jakubowska and Kowalczyk 2005; Woodward and Bartel 2005; Korasick et al. 2013).

In Zea mays, the enzyme indole-3-acetate beta-glucosyltransferase, product of IAGLU gene, is responsible for the formation of IAA-ester-linked conjugates (Szerszen et al. 1994). The ugt mutant results in 85% reduction in Ox-IAA-glc and a 2.5-fold increase in Ox-IAA formation (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7). The metabolism of IAA by glycosylation of oxIAA at differential and developmental stages has been noticed in UGT84B1, UGT74D1, and UGT76E3456 glycosyltransferases (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021). Here, involvement of UGT84B1 and UGT74D1 in modulating IAA levels throughout plant development where glycosylation IAA and oxIAA is involved. A novel UGT subfamily responsible for mediating the oxIAA glycosylation and modulating skotomorphogenic growth in A. thaliana is known (Mateo-Bonmatí et al. 2021).

Fig. 3.

Biochemical and effect of auxin assimilation in the mutants associated with Amide-linked (I) and Ester-linked (II) conjugates formation and hydrolysis. The upward and downward arrow represents the increases and decreases the level of the IAA conjugates. Abbreviations: includes IAA-leucine resistant1 (ilr1), IAA–alanine resistant 3 (iar3), indole-3-acetate beta-glucosyl transferase (iaglu), dwarf in light 1 (dlf1), upright rosette (uro), superroot (sur), and Gretchen Hagen 3.5 (wes1)

IAMT catalyzes the conversion of IAA to MeIAA to control auxin homeostasis in plants (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2018). It is an evolutionary member of the SABATH family (Zhao et al. 2008). IAMT1 catalyzes the formation of MeIAA where S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) interacts with IAA and facilitates the formation of MeIAA (Fig. 2) (Zhao et al. 2007; Zubieta et al. 2003), and it is de-methylated by methylesterase17 (MES17) (Yang et al. 2008). The iamt-D mutant exhibits a hyponastic leaf phenotype in A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 7) (Qin et al. 2005)—the expression level of the IAMT1 gene and its association with leaf curvature. The MeIAA form is more potent than IAA in inhibiting hypocotyl elongation, the ability to induce lateral roots, but weaker in inducing root hairs in A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 7) (Li et al. 2008).

The important molecules of auxins are catabolized by oxidation. Here the role of DAO1 enzyme is involved with the oxidation of IAA to OxIAA. Later, completion of reaction is by the conjugation of glucose and amino acid to OxIAA (Fig. 2) (Zhang et al. 2016; Porco et al. 2016). Two paralogs of DAO1 and DAO2 have been reported in genome of the A. thaliana (Zhang et al. 2016; Porco et al. 2016; Lakehal et al. 2019). In most cell types of A. thaliana, auxin accumulation signals both reactive oxygen species (ROS) and an irreversible 2-oxindole-3-acid acid catabolic product (OxIAA) (Peer et al. 2013). This influences IAA oxidation, auxin homeostasis, and plant growth (Zhang et al. 2016; Porco et al. 2016). In rice, DAO encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent-Fe (II) dioxygenase enzyme (2OGFe (II)), catalyzes the formation of IAA to form OxIAA (Zhao et al. 2013), identified the DAO1 dioxygenase irreversibly oxidation of IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu to 2-oxindole-3-acetic acid-aspartate (oxIAA-Asp) and oxIAA-Glu. The hydrolysis of inaction oxIAA in A. thaliana by ILR1 is also studied (Hayashi et al. 2021). Confirmatory information about the dao mutation affects release of pollens from anthers, and pollen fertility and rice parthenocarpic seed are observed (Supplementary Table 7). In A. thaliana, studies on the dao mutant show phenotype changes in inflorescence, root and leaves, and significant reduction in Ox-IAA conjugates (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7) (Zhang et al. 2016; Porco et al. 2016). Mutant studies of DAO1 (dao1-1 and dao1-2D) show unaffected level of IAA, tryptophan, for the downstream product of anthranilate and IAOx. However, the IAA generates intermediate including IAM, IPyA, and IAN which showed differences from the wild type in A. thaliana (Porco et al. 2016). These results also support alternative trp-independent pathways for auxin biosynthesis in plants. The dao1-1 mutants show 95% less oxIAA. The dao1 loss-of-function mutant plants exhibit altered morphology, including larger cotyledons, delayed sepal opening, elongated pistils, increased lateral root density, and reduced fertility in the primary inflorescence stem (Zhang et al. 2016). In contrast, the dao1-2D mutant shows an increase in oxIAA level and a decrease in stature with shorter leaves and inflorescence stems. DAO2 shows weak expression in the root apices seedling. This information suggests that the oxidation of IAA by DAO1 is the major auxin catabolic process in Arabidopsis. IAA oxidation at the tissue-specific level plays a crucial role in plant development and morphogenesis (Zhang et al. 2016).

Amide-linked IAA conjugates

The amide-linked IAA conjugates play a crucial role in IAA deactivation and maintain the auxin pool maintenance. As they are made available, adduct hydrolysis conjugates are reported in Supplementary Table 8. IAA amide-linked peptide and protein conjugates are found in Pisum sativum, A. thaliana, and strawberry (Park et al. 2010, 2006; Walz et al. 2002) and a suggestion to be present in Avena sativa (Percival and Bandurski 1976), Fragaria vesca (Park et al. 2006) and Phaseolus vulgaris (Bialek and Cohen 1986). In vivo inhibition of 19 IAA-L-amino acid conjugates affects the root elongation, and in vitro hydrolysis rates in A. thaliana (LeClere et al. 2002).

The IAA amino acid conjugates of some amino acids like Asp, Glu bank auxin to IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu, these are hydrolyzed by enzyme like ILR1/ILL amidohydrolases (A. thaliana) (Hayashi et al. 2021). The IAA amino acid conjugates inhibit (more than 50%) root elongation, including IAA-Asn, -Gln, -Glu, -Gly, -Met,-Ser, -Thr, and -Tyr, while the conjugates of IAA-Asp, -Cys, -His, -Ile, -Lys, -Pro, -Trp, and -Val, show less than 50% inhibition (LeClere et al. 2002). The hydrolysis of IAA conjugates is on root growth. Information about different mutants was integrated to assess conjugate formation (Fig. 3). The different mutants associated with different IAA amino acid linkages provide insights into the level of IAA amino acid conjugate (Supplementary Table 9). The enzyme associated is IAA-amido synthetase which is produced by the Gretchen Hagen 3 (GH3) gene. The precise auxin levels and their homeostasis are achieved by conjugating amino acid to an excess of IAA from a GH3 family. Cano et al. (2018) showed the presence of a competitive inhibitor of the GH3 enzyme, adenosine-5ʹ-[2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl] phosphate (AIEP), could improve rooting in stem cuttings of Dianthus caryophyllus. The endogenous auxin homeostasis could in turn be regulated by the GH3 proteins (Cano et al. 2018). The knock-out mutant (gh3oct) of the group II GH3 pathway showed an improved root architecture playing role in withstanding osmotic stresses and drought tolerance in A. thaliana. Here, an association with increased IAA levels is reported (Casanova-Sáez et al. 2022). Auxin homeostasis is maintained by several GH3 genes encoding IAA-amido synthetases responsible for the conjugation of excess IAA with amino acids (Fig. 2) (Fu et al. 2011; Peat et al. 2012). A large number of GH3 paralogs which are nineteen in A. thaliana, only 8 of them proved to have activity against IAA (Staswick et al. 2005), and the nine mutants of A. thaliana reported so far have different morphological characteristics (Supplementary Table 9) (Sun et al. 2010; Guo et al. 2004; Kong et al. 2017; Nakazawa et al. 2001; Takase et al. 2004), thirteen paralogs in Oryza sativa (Terol et al. 2006). The dfl, wes-1 and sur mutants showed high IAA-Asp conjugate in A. thaliana and affect negatively apical dominance (Staswick et al. 2005; Park et al. 2007a, b; Barlier et al. 2000). The other conjugates included IAA-Ala, IAA-Leu, and IAA-Glu levels, show reduction in wes-1, wes-1-D and uro mutants (Fig. 3).

The hydrolysis of amide-linked auxin conjugates is processed by amido-hydrolases enzymes produced by the ILR (IAA-Leucine-resistant), IAR (IAA-Alanine-resistant) and ILL (IAA-Leucine-resistant-like) genes. The insufficient level of active auxin causes the abnormal plant phenotype (Fu et al. 2011; Cheng et al. 2006, 2007; Park et al. 2007a, b). The mutant-based study shows that the reduced sensitivity of IAA amino acid conjugates in the root growth inhibition assay suggests the specific group of amido-hydrolases (Fig. 2), which is responsible for the hydrolysis of conjugated to produce active IAA and maintains auxin homeostasis (Bartel and Fink 1995; LeClere et al. 2002; Sanchez Carranza et al. 2016). Mutants generated so far include ILR, IAR, and ILL in A. thaliana and influence developmental changes (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 10) (Lasswell et al. 2000; Davies et al. 1999; LeClere et al. 2004; Bartel and Fink 1995). The single, double, and multiple mutants of iar, ilr, and ill show resistance or insensitivity to the IAA amino acid conjugates (Supplementary Table 10) (Magidin et al. 2003; Rampey et al. 2004) and changes in the root phenotype of A. thaliana. IAA amide yielded 580–860 ng/gfw more than the other conjugates in the amino acid reported in Supplementary Table 8.

Amide-linked amino acid conjugates, including IAA-Glu and IAA-Asp, are the predominant conjugates to A. thaliana (Kai et al. 2007; Novak et al. 2012), and these are irreversible conjugates. It inactivates excess IAA to maintain auxin homeostasis (Ostin et al. 1998; Porco et al. 2016). In the dao1 and gh3 mutant line, the IAA metabolite levels prove that conjugation and catabolism maintain auxin homeostasis (Porco et al. 2016). The dao mutant leads to the upregulation of the GH3.3 genes, responsible for increasing IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu levels to maintain auxin homeostasis (Porco et al. 2016). The GH3 protein exhibits faster enzyme kinetics (10,000 times higher) than the in vitro DAO1 enzyme assay (Staswick et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2016). Furthermore, DAO1 is constitutively highly expressed in most tissues to temporarily shut down active IAA. Interestingly, in an experiment with A. thaliana, the estimated enzyme level depended on IAA concentration and IAA adduct formation. This can be exemplified by low 0.5 mM IAA complexes via the OxIAA pathway, which produce a small portion of the conjugate. In the case of a higher IAA concentration level (5 mM), IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu conjugates have been identified (Ostin et al. 1998).

Ester-linked conjugates are responsible for IAA storage and can provide immediate auxin supply in plant growth. To date, the information could be summarized and tabulated. Ester and amide-linked auxin conjugates maintain auxin homeostasis of active auxin pool for growth and development at different stages. The optimal growing conditions of plant development follow one of the partial pathways of auxin biosynthesis at different stages (Zhao 2018; Korasick et al. 2013).

Evidences from abiotic stress conditions and their influence on auxin biosynthesis

Sub-optimal growing conditions (floods, droughts, air pollution, nutrient deficiency, and exposure to toxic ions) destabilize crop yields. Population growth is a significant challenge for food security (Mickelbart et al. 2015; Korver et al. 2018). The plants can survive in these conditions through stress adaptation loci that can provide specific solutions to the changing environment (Mickelbart et al. 2015).

Under abiotic stress conditions, genes related to tryptophan biosynthesis are up-regulated in A. thaliana (Tzin and Galili 2010). IAOx, an auxin biosynthesis intermediate, is converted into IAN and glucosinolates. These act in plant defense responses to biotic stress (Hansen and Halkier 2005; Mikkelsen et al. 2004; Pedras et al. 2002). Reduced light availability due to dense foliage, the plant extends hypocotyls, stems, and petioles and develops hyponastic leaves (Casal 2012; Franklin 2008; Hersch et al. 2014). The de novo auxin biosynthesis leads to phenotypic changes under stress conditions via the PIF (phytochrome-interacting factor) family of helix–loop–helix transcription factors, which bind to the YUC gene to produce auxin (Hornitschek et al. 2012; Li et al. 2012; Michaud et al. 2017). An improved phototropism in shade (Goyal et al. 2016) is associated with rapid local biosynthesis of auxin by the YUC trigger via the PIF-YUC module (Fig. 1).

The PIF overexpression study shows enhanced phototropism. The YUC3 gene induced in pif4pif5pif7 shows triple mutants phototropism. These results suggest that the PIF-YUC module is an essential regulatory step for phototropism (Goyal et al. 2016). Recently, UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT76F1) has been identified in A. thaliana, which is involved in auxin homeostasis through glucosylation of the major auxin precursor (IPyA). It produces IPyA glucose conjugates (IPyA-Glc). The IPyA-Glc is negatively regulated by the involvement of the transcription factor PIF4 and is essential for light- and temperature-dependent hypocotyl growth (Chen et al. 2020). This information suggests that IPyA-Glc is involved in auxin biosynthesis and homeostasis as well as help in the plant adaption to the growing environment.

The effect of temperature on plant morphogenesis and architectural changes is called thermomorphogenesis (Raschke et al. 2015; Erwin et al. 1989). The phenotype shows hypocotyl elongation (Gray et al. 1998) and hyponastic leaves (Zanten et al. 2009) in A. thaliana. Thermomorphogenesis interact the PIF-YUC. Investigation on the pif4 mutant demonstrates hypocotyls prolongation at high temperatures (Franklin et al. 2011; Press et al. 2016; Proveniers and van Zanten 2013; Quint et al. 2016). Phytochrome B (phyB) is the temperature sensor (Song et al. 2017; Legris et al. 2016) interacting with PIF4 when a temperature change occurs. Thus, free concentrations of PIF4 activate auxin biosynthesis by directly targeting auxin biosynthetic genes, including TAA1, YUC8, and CYP79B2 (Fig. 1 and Table1) (Franklin et al. 2011; Sun et al. 2012). The effect of phytohormone cytokinins (CKs) and abscisic acid (ABA) on auxin biosynthesis is responsible for the sustainability of plants under various stress (Xu et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2011; Ljung 2013).

The local auxin biosynthesis ensures plant sustainability in metal-contaminated soil. The YUC3, YUC5, YUC7, YUC8, and YUC9 genes are expressed under Al-induced stress conditions. PIF4 interacts with YUC5, YUC8, and YUC9 to produce local auxin biosynthesis by the PIF-YUC module at the root of the apex transition zone (Liu et al. 2016).

The nutrient deficiencies negatively affect plant growth, especially for the phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N). Plant root system architecture (RSA) shows modification to maintain the state of nutrient deficiencies (Koevoets et al. 2016; Bhosale et al. 2018). In P deficiency, strigolactones phytohormone enhance the expression of TIR1 (auxin receptor) (Mayzlish-Gati et al. 2012) to increase auxin sensitivity leading to changes in morphogenesis (promoting the formation of the lateral root) (Ruyter-Spira et al. 2011). In A. thaliana, the limiting condition of P results in an increase in the number of lateral roots, which is an increase by 50%, and stimulates root hair in the axr2 mutant (hairless) with an exogenous supply of IAA (Bates and Lynch 1996). Hairs with long roots produce high yield, while short roots are less-resistant low-P yield in barley (Gahoonia and Nielsen 2004).

In maize, there are a deeper root system and fewer crown roots under nitrogen deficiency (Saengwilai et al. 2014). Here, the NRT1.1 transporter responsible for nitrate uptake from soil also transports auxins (Solanki and Shukla 2015). These NRT1.1 under the nitrogen stress, modulate both auxin levels and meristematic activity in the root have been demonstrated in A. thaliana. Under nitrogen stress, many NRT1.1 transporters are reported (Mounier et al. 2014).

Drought stress also shows distinct changes in RSA due to the auxin distribution in the root through polar auxin transport and bending of plant organs toward positive gravitropism of the primary root (Koevoets et al. 2016). The angle of the growing roots determines whether the RSA grows shallow or deep (Rosquete et al. 2013). Correlation between root and drought tolerance has been observed in Oryza sativa (Kato et al. 2006) and Triticum aestivum (Manschadi et al. 2008). The Deeper Rooting1 (DRO1) gene influences the downward curvature of roots due to the change in auxin distribution in rice, which shows high yield under drought stress (Uga et al. 2013). Abiotic stress in the environment is a general phenomenon that affects the plant growth. Still, the plant can manage it by modulating the biosynthesis of auxin in priority, after which the defense mechanism is activated for the sustainability of the plant.

Conclusions and utilization of auxin biosynthesis for sustainable agriculture

Site for auxin biosynthesis occurs independently in the root tips, shoot tips, and young leaves. It influences auxin maxima and minima through the polar auxin transport mechanism by the involvement of PIN proteins. Trp-dependent and -independent pathways enable auxin biosynthesis and its homeostasis. Additionally, IAA-Glc among amide-linked conjugates can deliver IAA via myo-inositol pathways. Oxidation of auxin adduct by DAOs plays pivotal role in regulation of auxin homeostasis. The GH3 genes maintain the auxin concentration for the growth and the development of the plants.

The first trp-dependent pathway precursor tryptophan occurs in the chloroplast and has negative feedback. Tryptophan is a precursor to IAOx, IPyA, and IAM. The IPyA pathway through the TAA1/YUC genes converts tryptophan to IAA conversion and is the most critical pathway between the three sub-pathways (IAOx, IPyA, and IAM) for active auxin biosynthesis. The YUC has eleven isoforms, and their different mutants provide insight into auxin biosynthesis. The unfavorable durability of the plant depends on the rapid local biosynthesis of auxin by the PIF-YUC module. Phytochrome B detects heat, releases attached PIF, and activates IAA accumulation by overexpression of TAA1, YUC8, and CYP79B2, resulting in plant morphogenesis. Some of the questions remain unanswered, such as the enzymes involved in the conversion of tryptophan to IAM, IAOx to IAM, and IAOx to IAN, which could lead to a comprehensive understanding of auxin biosynthesis. Recent evidences from epigenetics and information processed from various plants clearly show the diversity of pattern of mode of accumulation and assimilation. Sustainable agriculture under climate change conditions could be improved and auxin biosynthesis, and factors affecting it could be twitched for improving yield and auxins determine plants survival under biotic and abiotic stress and plasticity. Auxin biosynthesis inputs for smart agriculture provide insights into the possible modulating step to improve root and shoot pluripotency under adverse growing conditions to achieve sustainable food for all.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This research was funded by Department of biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology (BT/PR11797/AGR/36/608/2009).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abel S, Theologis A. Odyssey of auxin. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2010;2(10):a004572. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamowski M, Friml J. PIN-dependent auxin transport: action, regulation, and evolution. Plant Cell. 2015;27(1):20–32. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoi Y, Hira H, Hayakawa Y, Liu H, Fukui K, Dai X, Tanaka K, Hayashi K-i, Zhao Y, Kasahara H. UDP-glucosyltransferase UGT84B1 regulates the levels of indole-3-acetic acid and phenylacetic acid in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;532(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai B, Novak O, Ljung K, Hanson J, Bentsink L. Combined transcriptome and translatome analyses reveal a role for tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis in the control of DOG1-dependent seed dormancy. New Phytol. 2018;217(3):1077–1085. doi: 10.1111/nph.14885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajguz A, Piotrowska A. Conjugates of auxin and cytokinin. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(8):957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak S, Nielsen HL, Halkier BA. The presence of CYP79 homologues in glucosinolate-producing plants shows evolutionary conservation of the enzymes in the conversion of amino acid to aldoxime in the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides and glucosinolates. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38(5):725–734. doi: 10.1023/A:1006064202774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barczak AJ, Zhao J, Pruitt KD, Last RL. 5-Fluoroindole resistance identifies tryptophan synthase beta subunit mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1995;140(1):303–313. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlier I, Kowalczyk M, Marchant A, Ljung K, Bhalerao R, Bennett M, Sandberg G, Bellini C. The SUR2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes the cytochrome P450 CYP83B1, a modulator of auxin homeostasis. PNAS. 2000;97(26):14819–14824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260502697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel B, Fink GR. ILR1, an amidohydrolase that releases active indole-3-acetic acid from conjugates. Science. 1995;268(5218):1745–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.7792599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TR, Lynch JP. Stimulation of root hair elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana by low phosphorus availability. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;19(5):529–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00386.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhosale R, Giri J, Pandey BK, Giehl RFH, Hartmann A, Traini R, Truskina J, Leftley N, Hanlon M, Swarup K, Rashed A, Voß U, et al. A mechanistic framework for auxin dependent Arabidopsis root hair elongation to low external phosphate. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1409. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03851-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialek K, Cohen JD. Isolation and partial characterization of the major amide-linked conjugate of indole-3-acetic acid from Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plant Physiol. 1986;80(1):99–104. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee JJ, Bandyopadhyay A, Lee OR, Mravec J, Titapiwatanakun B, Sauer M, Makam SN, Cheng Y, Bouchard R, et al. Interactions among PIN-FORMED and P-glycoprotein auxin transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(1):131–147. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackmann K, Qi J, Gebert M, Jouannet V, Schlamp T, Grunwald K, Wallner ES, Novikova DD, et al. Spatial specificity of auxin responses coordinates wood formation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):875. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03256-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Sánchez-García AB, Albacete A, González-Bayón R, Justamante MS, Ibáñez S, Acosta M, Pérez-Pérez JM. Enhanced conjugation of auxin by GH3 enzymes leads to poor adventitious rooting in carnation stem cuttings. Front Plant Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ. Shade avoidance. Arabidopsis Book. 2012;10:e0157. doi: 10.1199/tab.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Sáez R, Mateo-Bonmatí E, Ljung K. Auxin metabolism in plants. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a039867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Sáez R, Mateo-Bonmatí E, Šimura J, Pěnčík A, Novák O, Staswick P, Ljung K. Inactivation of the entire Arabidopsis group II GH3s confers tolerance to salinity and water deficit. New Phytol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/nph.18114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Toyota M, Moeder W, Chin K, Fortuna A, Champigny M, Vanneste S, Gilroy S, Beeckman T, Nambara E, Yoshioka K. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 2 modulates auxin homeostasis and signaling. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/508572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Dai X, De-Paoli H, Cheng Y, Takebayashi Y, Kasahara H, Kamiya Y, Zhao Y. Auxin overproduction in shoots cannot rescue auxin deficiencies in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55(6):1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tong J, Xiao L, Ruan Y, Liu J, Zeng M, Huang H, Wang J-W, Xu L. YUCCA-mediated auxin biogenesis is required for cell fate transition occurring during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(14):4273–4284. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Huang X-X, Zhao S-M, Xiao D-W, Xiao L-T, Tong J-H, Wang W-S, Li Y-J, Ding Z, Hou B-K. IPyA glucosylation mediates light and temperature signaling to regulate auxin-dependent hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. PNAS. 2020;117(12):6910–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000172117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20(13):1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(8):2430–2439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y, Zhu Y, Wu M-F, Simonini S, Kuhn A, Armenta-Medina A, Jin R, Østergaard L, Gillmor CS, Wagner D. Auxin response factors promote organogenesis by chromatin-mediated repression of the pluripotency gene SHOOTMERISTEMLESS. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):886. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08861-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SD, Nichols DS, Smith J, Chourey PS, McAdam EL, Quittenden L, Ross JJ. Auxin biosynthesis: are the indole-3-acetic acid and phenylacetic acid biosynthesis pathways mirror images? Plant Physiol. 2016;171(2):1230–1241. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui D, Zhao J, Jing Y, Fan M, Liu J, Wang Z, Xin W, Hu Y. The Arabidopsis IDD14, IDD15, and IDD16 cooperatively regulate lateral organ morphogenesis and gravitropism by promoting auxin biosynthesis and transport. PLOS Genet. 2013;9(9):e1003759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Mashiguchi K, Chen Q, Kasahara H, Kamiya Y, Ojha S, DuBois J, Ballou D, Zhao Y. The biochemical mechanism of auxin biosynthesis by an Arabidopsis YUCCA flavin-containing monooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(3):1448–1457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies RT, Goetz DH, Lasswell J, Anderson MN, Bartel B. IAR3 encodes an auxin conjugate hydrolase from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1999;11(3):365–376. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di D-W, Zhang C, Luo P, An C-W, Guo G-q. The biosynthesis of auxin: how many paths truly lead to IAA? Plant Growth Regul. 2015;78:275–285. doi: 10.1007/s10725-015-0103-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund DM, Ishizaki K, Flores-Sandoval E, Kikuchi S, Takebayashi Y, Tsukamoto S, Hirakawa Y, Nonomura M, Kato H, Kouno M, et al. Auxin produced by the indole-3-pyruvic acid pathway regulates development and gemmae dormancy in the liverwort marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell. 2015;27(6):1650–1669. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin JE, Heins RD, Karlsson MG. Thermomorphogenesis in Lilium longiflorum. Am J Bot. 1989;76(1):47–52. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1989.tb11283.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima M, Ma X, Zhou P, Zaynab M, Ming R. Auxin regulated metabolic changes underlying sepal retention and development after pollination in spinach. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02944-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraru E, Friml J. PIN polar targeting. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(4):1553–1559. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.121756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA. Shade avoidance. New Phytol. 2008;179(4):930–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Lee SH, Patel D, Kumar SV, Spartz AK, Gu C, Ye S, Yu P, Breen G, Cohen JD, Wigge PA, Gray WM. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. PNAS. 2011;108(50):20231–20235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110682108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Yu H, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S. Rice GH3 gene family: regulators of growth and development. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6(4):570–574. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.4.14947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahoonia TS, Nielsen NE. Barley genotypes with long root hairs sustain high grain yields in low-P field. Plant Soil. 2004;262(1–2):55–62. doi: 10.1023/B:PLSO.0000037020.58002.ac. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallavotti A, Barazesh S, Malcomber S, Hall D, Jackson D, Schmidt RJ, McSteen P. Sparse inflorescence1 encodes a monocot-specific YUCCA-like gene required for vegetative and reproductive development in maize. PNAS. 2008;105(39):15196–15201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805596105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M, Blakeslee JJ, Bouchard R, Lee OR, Vincenzetti V, Bandyopadhyay A, Titapiwatanakun B, Peer WA, Bailly A, et al. Cellular efflux of auxin catalyzed by the Arabidopsis MDR/PGP transporter AtPGP1. Plant J. 2005;44(2):179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A, Karayekov E, Galvao VC, Ren H, Casal JJ, Fankhauser C. Shade promotes phototropism through phytochrome B-controlled auxin production. Curr Biol. 2016;26(24):3280–3287. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WM, Ostin A, Sandberg G, Romano CP, Estelle M. High temperature promotes auxin-mediated hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. PNAS. 1998;95(12):7197–7202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb CD, Zipp BJ, Kopycki J, Schubert M, Quint M, Lim EK, Bowles DJ, Pedras MS, Abel S. Comparative analysis of Arabidopsis UGT74glucosyltransferases reveals a special role of UGT74C1 in glucosinolatebiosynthesis. Plant J. 2014;79:92–105. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G. Auxin response factors. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(5):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Yuan Z, Sun Y, Liu J, Huang H. Characterizations of the uro mutant suggest that the URO gene is involved in the auxin action in Arabidopsis. Acta Bot Sin. 2004;46(7):846–853. [Google Scholar]

- Haagen-Smit AJ, Dandliker WB, Wittwer SH, Murneek AE. Isolation of 3-indole acetic acid from immature corn kernels. Am J Bot. 1946;33:118–120. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1946.tb10354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen BG, Halkier BA. New insight into the biosynthesis and regulation of indole compounds in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2005;221(5):603–606. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Ki, Arai K, Aoi Y, et al. The main oxidative inactivation pathway of the plant hormone auxin. Nat Commun. 2021;12:6752. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Chen X, Huang H, Xu L. Reprogramming of H3K27me3 is critical for acquisition of pluripotency from cultured Arabidopsis tissues. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(8):e1002911–e1002911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch M, Lorrain S, de Wit M, Trevisan M, Ljung K, Bergmann S, Fankhauser C. Light intensity modulates the regulatory network of the shade avoidance response in Arabidopsis. PNAS. 2014;111(17):6515–6520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320355111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P, Kohnen MV, Lorrain S, Rougemont J, Ljung K, Lopez-Vidriero I, Franco-Zorrilla JM, et al. Phytochrome interacting factors 4 and 5 control seedling growth in changing light conditions by directly controlling auxin signaling. Plant J. 2012;71(5):699–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull AK, Vij R, Celenza JL. Arabidopsis cytochrome P450s that catalyze the first step of tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(5):2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RG, Lim EK, Li Y, Kowalczyk M, Sandberg G, Hoggett J, Ashford DA, Bowles DJ. Identification and biochemical characterization of an Arabidopsis indole-3-acetic acid glucosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(6):4350–4356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RG, Kowalczyk M, Li Y, Higgins G, Ross J, Sandberg G, Bowles DJ. Over-expression of an Arabidopsis gene encoding a glucosyltransferase of indole-3-acetic acid: phenotypic characterisation of transgenic lines. Plant J. 2002;32(4):573–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska A, Kowalczyk S. A specific enzyme hydrolyzing 6-O(4-O)-indole-3-ylacetyl-beta-D-glucose in immature kernels of Zea mays. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S-H, Ma X-M, Han P, Wang B, Sun Y-G, Zhang G-Z, Li Y-J, Hou B-K. UGT74D1 Is a Novel Auxin Glycosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Gunneras SA, Petersson SV, Tarkowski P, Graham N, May S, Dolezal K, Sandberg G, Ljung K. Cytokinin regulation of auxin synthesis in Arabidopsis involves a homeostatic feedback loop regulated via auxin and cytokinin signal transduction. Plant Cell. 2010;22(9):2956–2969. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai K, Horita J, Wakasa K, Miyagawa H. Three oxidative metabolites of indole-3-acetic acid from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(12):1651–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]