Abstract

Understanding and exploiting the redox properties of uranium is of great importance because uranium has a wide range of possible oxidation states and holds great potential for small molecule activation and catalysis. However, it remains challenging to stabilise both low and high-valent uranium ions in a preserved ligand environment. Herein we report the synthesis and characterisation of a series of uranium(II–VI) complexes supported by a tripodal tris(amido)arene ligand. In addition, one- or two-electron redox transformations could be achieved with these compounds. Moreover, combined experimental and theoretical studies unveiled that the ambiphilic uranium–arene interactions are the key to balance the stabilisation of low and high-valent uranium, with the anchoring arene acting as a δ acceptor or a π donor. Our results reinforce the design strategy to incorporate metal–arene interactions in stabilising multiple oxidation states, and open up new avenues to explore the redox chemistry of uranium.

Subject terms: Chemical bonding, Nuclear chemistry, Chemical bonding

Understanding and exploiting the redox properties of uranium is of great importance but stabilizing both low and high valent uranium ions in a preserved ligand environment remains challenging. Here, the authors report the synthesis and characterisation of a series of uranium(II–VI) complexes supported by a tripodal tris(amido)arene ligand.

Introduction

Uranium is the heaviest element abundant in nature. As an early actinide, uranium can exhibit multiple oxidation states and rich redox chemistry1,2. Understanding and exploiting the redox properties of uranium is not only pivotal for basic research3, but also pressing for the nuclear industry4–6, environmental sciences7–9, and catalysis10,11. Five oxidation states, uranium(II) to uranium(VI), are well established, with a recent addition of a molecular uranium(I) complex12. Typically, low and high-valent uranium ions need a distinct coordination environment and thus may undergo substantial ligand rearrangement upon redox transformations2,13,14. For example, bis(trimethylsilyl)amide ([N(SiMe3)2]–) has been shown to form uranium(II–VI) complexes, whereas the lability of [N(SiMe3)2]– results in a low structural rigidity and complicates the reaction outcomes under redox conditions15–17. On the other hand, chelating ligands with well-defined frameworks can provide a retained coordination environment, enabling a direct comparison of different oxidation states, and controllable redox transformations. Prominent examples include the tris(amido)amine [TrenTIPS]3–, the tris(aryloxide)tris(amine) [(AdArO)3tacn]3–, the bis(iminophosphorano)methanediide [BIPMTMS]2–, and the tris(aryloxide)arene [(Ad,MeArO)3mes]3– (Fig. 1a). These chelating ligands made possible the isolation of the first terminal uranium nitride complex18, a linear, O-coordinated η1-CO2 bound to uranium19, an arene-bridged diuranium single-molecule magnet20, and electrocatalytic water reduction21, respectively. Remarkably, these achievements were made through redox processes, underlining the power of uranium redox chemistry within a retained ligand framework.

Fig. 1. Selected chelating ligands previously reported and synthesis and molecular structures in this work.

a Selected chelating ligands capable of supporting multiple oxidation states of uranium. b Synthesis and molecular structures of uranium(II–VI) complexes 1–5 supported by [AdTPBN3]3–. The single crystal structures are shown in thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability. All hydrogen atoms, counterions, and lattice solvents are omitted for clarity. Atom (colour): U (green), N (blue), O (red), C of the anchoring arene (pink), C of others (grey).

Despite great success, no chelating ligand has been shown to support all five well-established oxidation states of uranium, uranium(II–VI). For instance, while the electron-rich [TrenTIPS]3–, [(AdArO)3tacn]3–, and [BIPMTMS]2– have previously been shown to support uranium(III–VI)22–25, the arene-anchored [(Ad,MeArO)3mes]3– was found to stabilise uranium(II–V)26,27. We anticipated that the ambiphilic nature of arenes28 might be utilized to balance the stability of low and high-valent uranium ions. It has been shown that weak π interactions exist between electrophilic uranium centres and neutral arenes29–31, while uranium–arene δ interactions play a big role in inverse-sandwich uranium arene complexes20,25,32–37, the stabilisation of unusual oxidation states26,38,39, and the implementation of uranium electrocatalysis21,27. Herein, we report the stabilisation of five oxidation states of uranium by a tris(amido)arene ligand through ambiphilic uranium–arene interactions, together with controlled redox transformations within this retained ligand framework.

Results

Synthesis and structural characterization

The pro-ligand 1,3,5-[2-(1-AdNH)C6H4]3C6H3 (H3[AdTPBN3], Ad = 1-adamantyl) was prepared on a gram scale following a protocol similar to N-aryl tris(amido)arene pro-ligands40. In contrast to the fluxional behaviour of N-aryl tris(amido)arenes, H3[AdTPBN3] exhibits a C3-syn structure with three nitrogen donors located at the same side of the 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene (TPB) backbone pointing inward (Supplementary Fig. 2). The pre-organized structure and improved crystallinity of [AdTPBN3]3– provide ease for work-up and crystallization. Figure 1b illustrates the synthetic access to uranium(II–VI) complexes supported by [AdTPBN3]3–. Deprotonation of H3[AdTPBN3] by KCH2Ph and subsequent salt metathesis with UI3(THF)4 yielded a uranium(III) complex (AdTPBN3)U (1). Reduction of 1 by potassium graphite (KC8) in the presence of 2,2,2-cryptand (crypt) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) generated a uranium(II) product [K(crypt)][(AdTPBN3)U] (2). On the other hand, oxidation of 1 by pyridine-N-oxide (C5H5NO) or N2O in toluene furnished a uranium(V) terminal oxo complex (AdTPBN3)UO (3). Furthermore, one-electron reduction or oxidation of 3 could be realized by KC8/crypt in THF or silver hexafluoroantimonate (AgSbF6) in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), to afford the corresponding uranium(IV) and uranium(VI) terminal oxo complexes, [K(crypt)][(AdTPBN3)UO] (4) and [(AdTPBN3)UO][SbF6] (5), respectively. These compounds were obtained in moderate to high yields and had good stability under inert atmosphere. For instance, no decomposition of the uranium(II) complex 2 in THF was observed even after prolong heating at 50 °C.

Compounds 1–5 were characterized by X-ray crystallography. The superpositions of the molecular structures (Fig. 2a) and key metrical parameters (Supplementary Table 1) of 1–5 reveal several features. Firstly, a ligand framework with a pseudo C3 symmetry is retained for all compounds, with the decrease of the average U–N distances from 2.477(3) Å in 2 to 2.274(3) in 5 as the oxidation states of uranium increase. On the other hand, the U–Ccentroid distances vary considerably, which peak in 4 and decrease upon reduction or oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 13). 2 exhibits the shortest U–Ccentroid distance of 2.18 Å, and the average C–C distance of the anchoring arene in 2 (1.417(6) Å) is statistically not distinguishable from that in H3[AdTPBN3] (1.399(2) Å) by the 3σ-criterion, consistent with a uranium(II) ion stabilised through δ backdonation26,38,39. 1 possesses a slightly longer U–Ccentroid distance of 2.34 Å, indicating weaker δ backdonation for the uranium(III) ion. For 3–5, the U–Ccentroid distances decrease as the oxidation states of uranium increase, from 2.69 Å in 4 to 2.57 Å in 3, and eventually to 2.49 Å in 5. Notably, the U–Ccentroid distance in 3 is close to the U–Ccentroid distances of 2.546(1)–2.581(3) Å in π-bonded neutral arene complexes of uranium29,30,41, but significantly shorter than the U–Ccentroid distances of 2.711(2) Å in another uranium(V) complex with an anchoring arene [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)U(O)(THF)]27. These structural features support our hypothesis that the anchoring arene may act as an additional ambiphilic ligand to balance the stabilisation of low-valent (II and III) and high-valent (V and VI) uranium ions. Furthermore, 3–5 represent the first trio of crystallographically authenticated uranium(IV–VI) terminal oxo complexes with the same supporting ligand. The U–O distances decrease as the oxidation states of uranium increase, from 1.874(4) Å in 4, to 1.829(2) Å in 3, and eventually to 1.818(2) Å in 5, in line with literature values23,27,42–44. The U–O stretching frequencies of 3–5 obtained from the infrared (IR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 24) are within the literature range for uranium terminal oxo complexes43,45–50. Moreover, the trend of U–O stretching frequencies of 3–5 is in line with the trend of the U–O bond distances, indicating the U–O bond strength increases as the oxidation state of uranium increases in this trio.

Fig. 2. Structural characterization and electrochemistry.

a Superpositions of molecular structures of 1‒5: C of the anchoring arene (magenta), O (pink), U(II) (red), U(III) (green), U(IV) (yellow), U(V) (sky blue), U(VI) (black). b Cyclic voltammograms of 1 (top) and 3 (bottom) at a scan rate of 200 mV/s in [nBu4N][PF6]/THF, with internal standard Fc*+/Fc* (Fc* = decamethylferrocene) labelled with *.

Electrochemistry and redox transformations

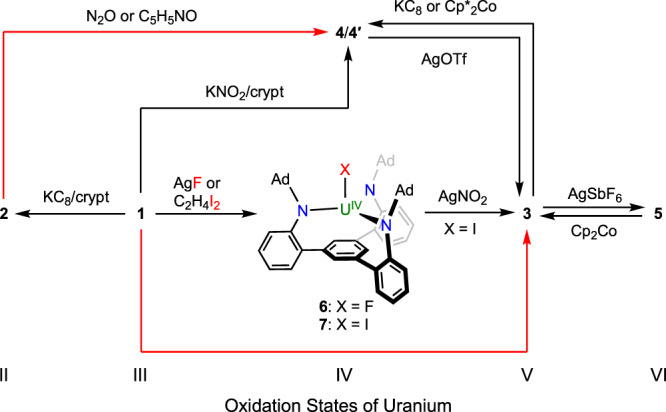

To further scrutinize the redox properties of these uranium complexes, electrochemical studies were carried out for 1 and 3. The cyclic voltammogram of 1 revealed two one-electron events (Fig. 2b top). The reduction event at half-wave potentials E1/2 = –2.40 V versus Fc+/Fc (Fc = ferrocene) was assigned to a UIII/UII redox couple. According to the Randles-Ševčík analysis (Supplementary Fig. 31), the UIII/UII redox event is reversible at various scan rates between 20 and 800 mV/s. The reduction potential of 1 is less negative than that of [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)U] (–2.495 V versus Fc+/Fc)51, in agreement with the higher stability of 2 than that of [K(crypt)][((Ad,MeArO)3mes)U]26. On the other hand, the oxidation event at E1/2 = –0.12 V was assigned to a UIV/UIII couple, indicating chemically accessible one-electron oxidation of 1. Indeed, treating 1 with excess silver fluoride or half an equivalent of 1,2-diiodoethane in toluene yielded (AdTPBN3)UF (6) or (AdTPBN3)UI (7), respectively. Intriguingly, further oxidation of 7 with silver nitrite resulted in the formation of 3, probably through a (AdTPBN3)U(ONO) intermediate48, and the release of NO gas during the reaction was verified by the characteristic formation of Co(TPP)(NO) (TPP = 5,10,15,20-teraphenylporphyrin) in the trapping experiment with Co(TPP) (see Supplementary Information section 1.3 for details). Moreover, 1 could also be converted to 4 by reacting with KNO2 in the presence of crypt, representing a rare example of one-electron oxidation from uranium(III) to a uranium(IV) terminal oxo complex52,53. The cyclic voltammogram of 3 showed two reversible one-electron events at E1/2 = –1.60 V and –0.16 V versus Fc+/Fc, assigned to UV/UIV and UVI/UV redox couples, respectively (Fig. 2b bottom). Based on these redox potentials, interconversions between 4 and 3 or 3 and 5 were realized by using appropriate oxidants (silver trifluoromethanesulfonate (AgOTf) or AgSbF6) or reductants (KC8 or Cp2Co, Cp = cyclopentadienyl). A variant of 4, [Cp*2Co][(AdTPBN3)UO] (4′), could also be obtained via reduction of 3 with a mild reductant Cp*2Co (Cp* = pentamethylcyclopentadienyl). Furthermore, two-electron oxidation of 2 to 4 could be accomplished by C5H5NO or N2O, expanding the underdeveloped multi-electron redox chemistry of uranium(II)39,54. A full picture of redox transformations of uranium ions within the retained ligand framework of [AdTPBN3]3– is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Redox transformations for 1–7.

Black arrows for one-electron processes and red arrows for two-electron processes.

Spectroscopic and magnetic studies

Various spectroscopic characterizations were performed to elucidate the electronic structures of this series of uranium complexes. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 shows an upfield resonance at –72 ppm assigned to the protons of the anchoring arene (Supplementary Fig. 49), characteristic for uranium–arene δ interaction33. On the contrary, 5 exhibits a deshielded resonance at 9.13 ppm for the corresponding arene protons (Supplementary Fig. 56), indicating π-donation from the anchoring arene to the uranium(VI) ion. The UV–Vis–NIR spectra were recorded in THF for compounds 1–7 (Fig. 4a). Notably, the absorption spectrum of 2 has broad and intense bands in the visible and near-infrared regions, which is similar to other uranium(II) complexes with a 5f 46d0 electronic configuration26,38, but different from 5f 36d 1 uranium(II) ions55. The ligand-to-metal charge transfer bands are mostly in the ultra-violet region for 4, but bathochromically shifted to visible and near-infrared regions for 3 and 5. While 3 and 4 exhibit characteristic f–f transitions in the near-infrared region for uranium(V) and uranium(IV) ions, respectively, 5 absorbs strongly over the entire range from 260–1600 nm with the absence of f–f transitions, analogous to other uranium(VI) terminal oxo complexes43,44. Since X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) has been shown to diagnostically identify the change of oxidation states for f-elements56, we obtained XPS spectra for 1–7 (Supplementary Figs. 81–87). The binding energies of uranium 4 f orbitals show an increasing trend, as the oxidation states of uranium increase (Supplementary Table 6).

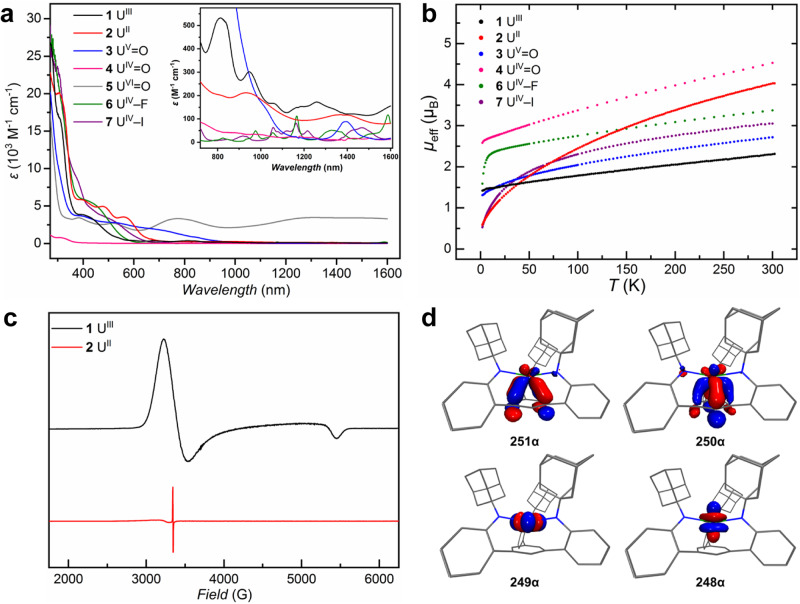

Fig. 4. Spectroscopic and magnetic studies and theoretical calculations.

a UV–Vis–NIR spectra of 1–7 with the inset showing the NIR region. b Magnetic moments as a function of temperature (2–298 K) for uranium(II–V) complexes. c X-band EPR spectra of 1 in toluene and 2 in THF at 10 K. d Kohn-Sham orbitals (isosurface = 0.05) of the four SOMOs of 2; hydrogens were omitted for clarity.

The electronic structures of these uranium complexes were further probed by superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry. Variable-temperature direct-current magnetic susceptibility data were collected under an applied magnetic field of 1 kOe for all compounds but diamagnetic 5 in solid state. The effective magnetic moments (μeff) as a function of temperature are shown in Fig. 4b. The μeff of 2 at 298 K is 4.02 μB, much higher than any previously reported uranium(II) complexes (2.2–2.8 μB at 300 K)26,38,39,57,58 and the theoretical value of 2.68 μB for a free 5f 4 ion with a 5I4 ground state. The high μeff of 2 may be attributed to the population of thermally accessible excited states, such as 5I5 with a theoretical value of 4.93 μB, because of strong bonding interactions between uranium and the anchoring arene. Upon lowering the temperature, the magnetic moments of 2 drop rapidly toward zero (μeff = 0.59 μB at 2 K), in line with other uranium(II) complexes26,38,57,58. While the temperature profiles of 1 and 3 are typical for uranium(III) and uranium(V), the high and low temperature magnetic moments of 4 (μeff = 4.53 μB at 298 K, and 2.58 μB at 2 K) are far exceeding the normal range of uranium(IV) ions59. Actually, to the best of our knowledge, both values of 4 are the highest in the literature for any single uranium(IV) ion. The presence of the strong axial oxo ligand and crystallographically three-fold symmetry may cause this anomalous magnetic behaviour of 4, as shown in a recent magnetic study on (UO[N(SiMe3)2]3)–60. Notably, 6 also exhibits unusually large magnetic moments at low temperature (μeff = 1.59 μB at 2 K), while 7 behave normally (μeff = 0.53 μB at 2 K). The decrease of low temperature magnetic moments for 4, 6, and 7 corresponds with the descending bond strengths of the axial oxo, fluoro, and iodo ligands. Furthermore, the X-band electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra for 1–3 were collected at 10 K (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 97). The EPR spectra of 1 and 3 exhibited well-resolved anisotropic, nearly axial signals, as expected for uranium(III) and uranium(V) complexes with approximate C3v symmetry26,61. Simulation of the EPR spectra gave g∥ value of 1.22 and g⊥ values of 1.98 and 2.07 for 1, and g∥ value of 1.33 and g⊥ values of 0.57 and 0.57 for 3, consistent with 4I9/2 ion and 2F5/2 ion with a magnetic doublet ground state, respectively. The EPR spectrum of 2 only showed a small signal at g = 2.00, which might be attributed to a radical impurity or solvated electrons (g = 2.0023). The absence of EPR response for 2 is consistent with the assignment of a 5f 4 electronic configuration26,38.

Theoretical calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations with scalar relativistic effects were performed on the full structures of 1–7 to probe their electronic structures, and in particular, the role of the anchoring arene in stabilising different oxidation states of uranium. The optimized structures match well with crystal structures. For 1, three singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMOs) are mainly composed of uranium 5f orbitals, as expected for a uranium(III) ion. Among them, SOMO and SOMO–1 have minor contributions from the anchoring arene, indicating weak δ backdonation from uranium to the arene (Supplementary Table 14 and Figure 98). The δ backdonation is more prominent in the SOMOs 251α and 250α of 2, featuring strong bonding interactions between uranium 5f orbitals and the π* orbitals of the anchoring arene, while the other two SOMOs, 249α and 248α, are predominantly uranium 5f orbitals (Fig. 4d). The calculation results are consistent with experimental evidences, supporting the description that 2 is a 5f 4 uranium(II) complex stabilised through δ backbonding with the anchoring arene. For 3–5, the composition analysis shows that while the uranium(IV) ion has few π interactions with the anchoring arene, the uranium(V) and uranium(VI) ions have appreciable π interactions with the anchoring arene (Supplementary Tables 16–18 and Figs. 100–102). These results are consistent with the elongated U–Ccentroid distance in 4 than 3 and 5. Notably, the uranium–arene interactions have some mixing with U–O interactions in 3 and 5, indicating possible inverse-trans-influence62–64. The natural localized molecular orbital (NLMO) analysis on U–O interactions shows one σ bond and two π bonds with increasing covalent character from uranium(IV) to uranium(VI) (Supplementary Tables 19–21 and Figs. 103–105), in line with the shortening of U–O distances. The multiple bonding character of U–O bonds is also supported by the Wiberg bond indexes, ranging from 1.52 to 1.93 (Supplementary Table 24). Other population analysis, including Mulliken atomic charges, spin populations, natural charges, and natural spin density (Supplementary Tables 25–28), gave similar pictures on the electronic structures of this series of uranium(II–VI) complexes.

To get a deeper insight on the uranium–arene interactions and their role in stabilising both low and high-valent uranium ions, extended transition state–natural orbitals for chemical valence (ETS–NOCV) calculations65 were carried out for 1–5, which were fragmented into the anchoring arene and the rest of the molecule. The σ, π, and δ-type uranium–arene interactions are calculated based on the symmetry of the NOCV pairs (Supplementary Tables 29–34). While the absolute values of stabilisation energies depend on the fragmentation and thus are arbitrary, the trend within a series is indicative of the relative strength of uranium–arene interactions. δ backdonation from uranium 5f orbitals to π* orbitals of the anchoring arene dominates in 1 and 2, whereas π donations from π orbitals of the anchoring arene to uranium-based orbitals gradually strengthen as the oxidation states of uranium increase. Overall, the trend of total stabilisation energies of uranium–arene interactions correlate well with the trend of U–Ccentroid distances for 1–5 (Supplementary Fig. 108). The ETS–NOCV analysis further confirms that the ambiphilic uranium–arene interactions play a significant part in stabilising both low and high-valent uranium ions.

Discussion

To summarize, a series of uranium(II–VI) compounds supported by a tripodal tris(amido)arene ligand were synthesized and characterised. Controlled two-way redox transformations could be readily achieved within the retained ligand framework. The electronic structures of these uranium complexes were scrutinized by structural, spectroscopic and magnetic studies together with DFT calculations, unveiling that the ambiphilic uranium–arene interactions play a pivotal role in stabilizing various oxidation states of uranium. The anchoring arene acts primarily as a δ acceptor for low-valent uranium ions and possesses increasing π donor characters as the oxidation states of uranium increase. The tripodal tris(amido)arene ligand framework capable of supporting five oxidation states of uranium will be an excellent platform to explore the redox chemistry of uranium, from installing multiply-bonded ligands to small molecule activation. Furthermore, the ligand design strategy disclosed here may be extended to other metals for supporting multiple oxidation states and enabling controllable redox transformations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22171008) and the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2018YFA0306003). We thank Dr. Jie Su for help with X-ray crystallography and Drs. Hui Fu and Xiu Zhang for help with NMR spectroscopy. The authors thank Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences and Peking University for financial support. C.D. thanks Peking University-BHP Carbon and Climate Wei-Ming PhD Scholars (No. WM202202) for support.

Author contributions

C.D. prepared and characterized the compounds. J.L. performed the theoretical calculations. R.S. and B.W. obtained and analysed the SQUID data. Y.W. and C.D. collected and analysed crystallographic and electrochemical data. P.F. and C.D. obtained the EPR data and performed simulations. B.W., S.G. and W.H. acquired fundings. W.H. supervised the study. C.D., J.L. and W.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all of the authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2245010–2245020. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Additional experimental, spectroscopic, crystallographic, and computational data are included in the Supplementary Information file. All other data are available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-40403-w.

References

- 1.Morss, L. R., Edelstein, N. M. & Fuger, J. The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements. 4th edn (Springer, 2011).

- 2.Löffler, S. T. & Meyer, K. in Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry III Series 3.13 - Actinides (eds Constable, E. C., Parkin, G & Que, L. Jr) 471–521 (Elsevier, 2021).

- 3.Liddle ST. The renaissance of non-aqueous uranium chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:8604–8641. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson, P. D. The Nuclear Fuel Cycle from Ore to Waste (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- 5.Natrajan LS, Swinburne AN, Andrews MB, Randall S, Heath SL. Redox and environmentally relevant aspects of actinide(IV) coordination chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014;266-267:171–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veliscek-Carolan J. Separation of actinides from spent nuclear fuel: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;318:266–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handley-Sidhu S, Keith-Roach MJ, Lloyd JR, Vaughan DJ. A review of the environmental corrosion, fate and bioavailability of munitions grade depleted uranium. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:5690–5700. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bargar JR, et al. Uranium redox transition pathways in acetate-amended sediments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:4506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219198110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newsome L, Morris K, Lloyd JR. The biogeochemistry and bioremediation of uranium and other priority radionuclides. Chem. Geol. 2014;363:164–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox AR, Bart SC, Meyer K, Cummins CC. Towards uranium catalysts. Nature. 2008;455:341–349. doi: 10.1038/nature07372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartline DR, Meyer K. From chemical curiosities and trophy molecules to uranium-based catalysis: developments for uranium catalysis as a new facet in molecular uranium chemistry. JACS Au. 2021;1:698–709. doi: 10.1021/jacsau.1c00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barluzzi L, Giblin SR, Mansikkamäki A, Layfield RA. Identification of oxidation state +1 in a molecular uranium complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:18229–18233. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c06519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ephritikhine M. Recent advances in organoactinide chemistry as exemplified by cyclopentadienyl compounds. Organometallics. 2013;32:2464–2488. doi: 10.1021/om400145p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gremillion, A. J. & Walensky, J. R. in Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry IV Series 4.05 - Cyclopentadienyl and Phospholyl Compounds in Organometallic Actinide Chemistry (eds Parkin, G., Meyer, K. & O’hare, D.) 185–247 (Elsevier, 2022).

- 15.Fortier S, Kaltsoyannis N, Wu G, Hayton TW. Probing the reactivity and electronic structure of a uranium(V) terminal oxo complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14224–14227. doi: 10.1021/ja206083p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker RJ. The coordination and organometallic chemistry of UI3 and U{N(SiMe3)2}3: synthetic reagents par excellence. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012;256:2843–2871. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modder DK, et al. Delivery of a masked uranium(II) by an oxide-bridged diuranium(III) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:3737–3744. doi: 10.1002/anie.202013473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King DM, et al. Synthesis and structure of a terminal uranium nitride complex. Science. 2012;337:717–720. doi: 10.1126/science.1223488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro-Rodriguez I, Nakai H, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL, Meyer K. A linear, O-coordinated η1-CO2 bound to uranium. Science. 2004;305:1757–1759. doi: 10.1126/science.1102602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills DP, et al. A delocalized arene-bridged diuranium single-molecule magnet. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halter DP, Heinemann FW, Bachmann J, Meyer K. Uranium-mediated electrocatalytic dihydrogen production from water. Nature. 2016;530:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature16530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King DM, et al. Isolation and characterization of a uranium(VI)–nitride triple bond. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:482–488. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosog B, La Pierre HS, Heinemann FW, Liddle ST, Meyer K. Synthesis of uranium(VI) terminal oxo complexes: molecular geometry driven by the inverse trans-influence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5284–5289. doi: 10.1021/ja211618v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills DP, et al. Synthesis of a uranium(VI)-carbene: reductive formation of uranyl(V)-methanides, oxidative preparation of a [R2C═U═O]2+ analogue of the [O═U═O]2+ uranyl ion (R = Ph2PNSiMe3), and comparison of the nature of UIV═C, UV═C, and UVI═C double bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10047–10054. doi: 10.1021/ja301333f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wooles AJ, et al. Uranium(III)-carbon multiple bonding supported by arene δ-bonding in mixed-valence hexauranium nanometre-scale rings. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2097. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Pierre HS, Scheurer A, Heinemann FW, Hieringer W, Meyer K. Synthesis and characterization of a uranium(II) monoarene complex supported by δ backbonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:7158–7162. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halter DP, Heinemann FW, Maron L, Meyer K. The role of uranium–arene bonding in H2O reduction catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:259–267. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rayón VM, Frenking G. Bis(benzene)chromium Is a δ-bonded molecule and ferrocene is a π-bonded molecule. Organometallics. 2003;22:3304–3308. doi: 10.1021/om020968z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cesari M, Pedretti U, Zazzetta Z, Lugli G, Marconi W. Synthesis and structure of a π-arene complex of uranium(III) - aluminum chloride. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1971;5:439–444. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)95960-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotton FA, Schwotzer W. Preparation and structure of [U2(C6Me6)2Cl7]+, the first uranium(IV) complex with a neutral arene in η6-coordination. Organometallics. 1985;4:942–943. doi: 10.1021/om00124a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreychuk NR, et al. Uranium(IV) alkyl cations: synthesis, structures, comparison with thorium(IV) analogues, and the influence of arene-coordination on thermal stability and ethylene polymerization activity. Chem. Sci. 2022;13:13748–13763. doi: 10.1039/D2SC04302E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaconescu PL, Arnold PL, Baker TA, Mindiola DJ, Cummins CC. Arene-bridged diuranium complexes: inverted sandwiches supported by δ backbonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6108–6109. doi: 10.1021/ja994484e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liddle ST. Inverted sandwich arene complexes of uranium. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015;293-294:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans WJ, Kozimor SA, Ziller JW, Kaltsoyannis N. Structure, reactivity, and density functional theory analysis of the six-electron reductant, [(C5Me5)2U]2(μ-η6:η6-C6H6), synthesized via a new mode of (C5Me5)3M reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14533–14547. doi: 10.1021/ja0463886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel D, et al. A formal high oxidation state inverse-sandwich diuranium complex: a new route to f-block-metal bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:10388–10392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold PL, Mansell SM, Maron L, McKay D. Spontaneous reduction and C–H borylation of arenes mediated by uranium(III) disproportionation. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:668–674. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mougel V, et al. Siloxides as supporting ligands in uranium(III)-mediated small-molecule activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12280–12284. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billow BS, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a neutral U(II) arene sandwich complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:17369–17373. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straub MD, et al. A uranium(II) arene complex that acts as a uranium(I) synthon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:19748–19760. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c07854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xin T, Wang X, Yang K, Liang J, Huang W. Rare earth metal complexes supported by a tripodal tris(amido) ligand system featuring an arene anchor. Inorg. Chem. 2021;60:15321–15329. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baudry D, et al. Arene uranium borohydrides: synthesis and crystal structure of (η-C6Me6)U(BH4)3. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989;371:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-328X(89)88022-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown JL, Fortier S, Lewis RA, Wu G, Hayton TW. A complete family of terminal uranium chalcogenides, [U(E)(N{SiMe3}2)3]− (E = O, S, Se, Te) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15468–15475. doi: 10.1021/ja305712m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt A-C, Heinemann FW, Lukens WW, Meyer K. Molecular and electronic structure of dinuclear uranium bis-μ-oxo complexes with diamond core structural motifs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11980–11993. doi: 10.1021/ja504528n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Löffler ST, Hümmer J, Scheurer A, Heinemann FW, Meyer K. Unprecedented pairs of uranium (IV/V) hydroxido and (IV/V/VI) oxido complexes supported by a seven-coordinate cyclen-anchored tris-aryloxide ligand. Chem. Sci. 2022;13:11341–11351. doi: 10.1039/D2SC02736D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arney DSJ, Burns CJ. Synthesis and structure of high-valent organouranium complexes containing terminal monooxo functional groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9840–9841. doi: 10.1021/ja00074a077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arney DSJ, Burns CJ. Synthesis and properties of high-valent organouranium complexes containing terminal organoimido and oxo functional groups. a new class of organo-f-element complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9448–9460. doi: 10.1021/ja00142a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zi G, et al. Preparation and reactions of base-free bis(1,2,4-tri-tert-butylcyclopentadienyl)uranium oxide, Cp′2UO. Organometallics. 2005;24:4251–4264. doi: 10.1021/om050406q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis AJ, Carroll PJ, Schelter EJ. Reductive cleavage of nitrite to form terminal uranium mono-oxo complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:511–518. doi: 10.1021/ja311057y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King DM, et al. Single-molecule magnetism in a single-ion triamidoamine uranium(V) terminal mono-oxo complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4921–4924. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenzweig MW, et al. A complete series of uranium(iv) complexes with terminal hydrochalcogenido (EH) and chalcogenido (E) ligands E = O, S, Se, Te. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:10853–10864. doi: 10.1039/C9DT00530G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.La Pierre HS, Kameo H, Halter DP, Heinemann FW, Meyer K. Coordination and redox isomerization in the reduction of a uranium(III) monoarene complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:7154–7157. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraft SJ, Walensky J, Fanwick PE, Hall MB, Bart SC. Crystallographic evidence of a base-free uranium(IV) terminal oxo species. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:7620–7622. doi: 10.1021/ic101136j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smiles DE, Wu G, Hayton TW. Synthesis of uranium–ligand multiple bonds by cleavage of a trityl protecting group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:96–99. doi: 10.1021/ja411423a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Modder DK, et al. Single metal four-electron reduction by U(II) and masked “U(II)” compounds. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:6153–6158. doi: 10.1039/D1SC00668A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacDonald MR, et al. Identification of the +2 oxidation state for uranium in a crystalline molecular complex, [K(2.2.2-Cryptand)][(C5H4SiMe3)3U] J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:13310–13313. doi: 10.1021/ja406791t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huh DN, et al. High-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of organometallic (C5H4SiMe3)3LnIII and [(C5H4SiMe3)3LnII]1– complexes (Ln = Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:16610–16620. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Windorff CJ, et al. Expanding the chemistry of molecular U2+ complexes: synthesis, characterization, and reactivity of the {[C5H3(SiMe3)2]3U}− anion. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22:772–782. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo F-S, et al. Isolation of a perfectly linear uranium(II) metallocene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:2299–2303. doi: 10.1002/anie.201912663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kindra DR, Evans WJ. Magnetic susceptibility of uranium complexes. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:8865–8882. doi: 10.1021/cr500242w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seed JA, et al. Anomalous magnetism of uranium(IV)-oxo and -imido complexes reveals unusual doubly degenerate electronic ground states. Chem. 2021;7:1666–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bart SC, et al. Carbon dioxide activation with sterically pressured mid- and high-valent uranium complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12536–12546. doi: 10.1021/ja804263w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Grady, E. & Kaltsoyannis, N. On the inverse trans influence. Density functional studies of [MOX5]n− (M = Pa, n = 2; M = U, n = 1; M = Np, n = 0; X = F, Cl or Br). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1233–1239 10.1039/B109696F (2002).

- 63.Denning RG. Electronic structure and bonding in actinyl ions and their analogs. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111:4125–4143. doi: 10.1021/jp071061n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.La Pierre HS, Meyer K. Uranium–ligand multiple bonding in uranyl analogues, [L=U=L]n+, and the inverse trans influence. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:529–539. doi: 10.1021/ic302412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitoraj MP, Michalak A, Ziegler T. A combined charge and energy decomposition scheme for bond analysis. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:962–975. doi: 10.1021/ct800503d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2245010–2245020. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Additional experimental, spectroscopic, crystallographic, and computational data are included in the Supplementary Information file. All other data are available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.