Abstract

The general public continues to show increased interest and uptake of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) genetic testing. We conducted an online survey (N = 405) to assess genetics knowledge, interest, and outcome expectancy of DTC genetic testing before and after exposure to a sample DTC disclaimer message. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the relationship between previous genetic knowledge, attitudes and self-reported systematic processing of a sample DTC disclaimer message, outcome expectancies, and interest to pursue DTC genetic testing. Increased genetic knowledge and more positive attitudes towards DTC genetic testing were associated with increased self-reported systematic processing of the DTC disclaimer message. Further, self-reported systematic processing of the DTC disclaimer message was associated with greater interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing but did not predict outcome expectancies. As DTC genetic testing continues to gain in popularity and usage, additional research is imperative to better understand participants’ motivations and processing of the DTC disclaimer messages to improve the user experience.

Subject terms: Genetic testing, Human behaviour

Introduction

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) genetic testing had an estimated 100 million consumers as of 2021 [1]. Often DTC companies have disclaimer messages on their website to clarify the accuracy and utility of DTC genetic testing as well as discuss what information these tests can and cannot provide and ensure for limited liability. Even if DTC companies’ website disclaimer messages provide specific information such as false positive rate, analytical validity, and clinical utility, consumers may not read them or take into consideration what DTC genetic tests actually provide. Most DTC genetic testing companies provide information about an individual’s risk of developing a disease based on the presence or absence of a limited number of single nucleotide variants (SNVs). The SNVs that DTC genetic testing companies use are generally of high frequency in the general population, with a few of higher frequency only in certain ethnic populations. For example, according to one DTC website, the three BRCA pathogenic variants analyzed are common in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish decent and relatively rare in other populations [2]. Therefore, if a consumer’s DTC genetic test report is negative for those three specific BRCA pathogenic variants, it does not rule out other BRCA pathogenic variants. The fact that most pathogenic variants are rare but DTC genetic testing labs generally only assess SNVs of higher allele frequencies means that the clinical utility of the results for most common and rare (Mendelian) disease is limited. Additionally, SNVs are not necessarily the sole cause of disease, given that additional risk factors (e.g., environment) must also be factored into the risk equation. Clinical grade genetic tests must be ordered by a medical professional and include analytical validity assessments in their testing method [3]. The limited analytical validity, as well as the limited clinical utility of DTC genetic tests may be explained in the DTC companies’ website disclaimer messages, although often not written in a way that is readily understandable or intuitive to the general public.

Most DTC consumers are also not seeking guidance on how to best use DTC genetic test results for clinical care; in one study only 43 (4%) sought out genetic counseling after receiving DTC genetic test results [4]. Additionally, up to 62% of DTC consumers may utilize third-party vendors to further interrogate their “raw genomic” data for additional health information [5]. These findings are particularly concerning given up to 40% of predicted pathogenic variants reported on DTC genetic test reports are false positives [6]. This false positive rate could influence the medical decisions of individuals using DTC genetic test results, particularly if they do not fully understand associated risks and the need for a genetic professional’s assessment.

Collectively, this illustrates a concerning disparity between medical professionals and the general public regarding the utility and significance of DTC genetic test results, which could result in the misinterpretation and misuse of DTC genetic test results. There is a lack of research examining whether this disparity stems from a lack of consideration of DTC disclaimer messages. The aim of the current study is to assess whether general public knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about DTC genetic testing affect depth of processing of DTC disclaimer messages, and whether deeper processing of these disclaimer messages decreases interest in DTC genetic testing. Our investigation is rooted in the Heuristic Systematic Model (HSM) [7], which describes how individuals may form opinions and attitudes about messages to make decisions or judgements. The HSM posits that individuals process information in one of three ways: systematically, a detailed and more effortful processing mode; heuristically, a more limited processing mode; or a combination of these two modes [8].

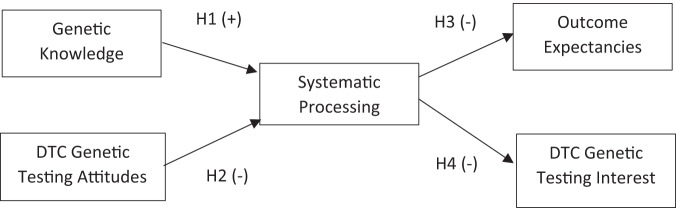

We hypothesized that individuals with greater genetics knowledge (H1: Fig. 1) and more negative attitudes towards DTC genetic testing (H2) would engage in deeper processing of a sample DTC disclaimer message. When individuals are motivated and interested in a message, and have an adequate understanding of its content, they are more likely to engage in deeper, more systematic processing [9]. We also expect that individuals with more negative attitudes about DTC genetic testing will engage in deeper processing of the DTC disclaimer message (H2) as the HSM posits that individuals seek correct and accurate beliefs [9]. As suggested by the HSM, individuals with negative attitudes towards DTC genetic testing who read a sample DTC disclaimer message are likely to process the information more systematically to better understand and reaffirm the accuracy of their beliefs [10]. Whereas individuals with more positive or neutral beliefs about DTC genetic testing are unlikely to have the same motivation, and, therefore, will engage with the DTC disclaimer message on a shallower, or more heuristic, level [10].

Fig. 1. Outline of study hypotheses.

Proposed model of the effects of disclaimer message processing on outcome expectancies and interest of DTC (direct-to-consumer) genetic testing. This figure outlines the hypothesized affects of genetics knowledge and DTC genetic testing attitudes on the level of self-reported systematic processing of the DTC disclaimer message and, subsequently, the affects that systematic processing has on participants' outcome expectancies and DTC genetic testing interest. Each arrow connecting the boxes is accompanied by a symbol showing which hypothesis the different variables are referring to and the proposed relationship between the variables; either (+, positive correlation) or (−, negative correlation). For example, in our first hypothesis (H1) we expect that greater genetics knowledge will be associated with an increase in self-reported systematic processing, designated by the (+). In contrast, in our fourth hypothesis (H4) we expect that greater systematic processing will lead to decreased DTC genetic testing interest, designated by the (−).

We further hypothesize that greater systematic processing of DTC disclaimer messages will be associated with decreased outcome expectancies regarding the utility of DTC genetic testing results (H3) and decreased interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing (H4). In a study of 836 participants conducted to predict the characteristics of individuals who are likely to have DTC genetic testing, individuals who scored lower on a general genetic knowledge survey were more interested in considering DTC genetic testing options [11]. Therefore, we expect that if participants engage in more systematic processing of the sample disclaimer messages, they will gain a better understanding of the limited utility that DTC genetic testing results have, which will decrease their original outcome expectancies. Additionally, we expect that deeper processing of the disclaimer message will be associated with decreased interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing because they understand the limited clinical utility [11].

Methods

Participants and procedures

We conducted an online survey to assess public knowledge, interest, and outcome expectancy of DTC genetic testing before and after being exposed to a sample DTC disclaimer message. This study was conducted as part of a larger parent study with the goal of understanding the effects of exposure to narrative messages promoting DTC genetic testing on interest in testing to identify the message frames that are most influential in this context. The parent study randomized participants into message conditions at study onset, but all participants were exposed to the same DTC disclaimer message and survey questions. All procedures were IRB approved.

Participants were recruited using Dynata, a U.S based online research panel provider. Study eligibility criteria included: age 18-plus, able to read and speak English, U.S. residency. There were no exclusion criteria. Incentives were offered in the form of points that could be redeemed for prizes.

After informed consent, participants completed a short online demographic survey (Time 1). Questions were asked to determine the participants’ genetics knowledge (Time 1) and relevant DTC genetic testing experience, interest, and attitudes. Immediately after, participants were randomized to one of the message conditions and asked to read one of four narrative messages about DTC genetic testing. Following message exposure, all participants were assessed on narrative recall and engagement, as well as attitudes, outcome expectancies, behavioral intentions, and interest regarding DTC genetic testing (Time 2). Then, participants were asked to read a sample DTC disclaimer message (Appendix A) that was paraphrased from the Genetics Home Reference website (April 30, 2019) entitled “What do the results of direct-to-consumer genetic testing mean?” We utilized a sample DTC disclaimer because an actual DTC disclaimer message was too long for this online survey setting. We rearranged the original Genetics Home Reference to include full sentences that further expanded on the limitations of DTC genetic testing, and the recommendation to see a genetic professional with questions about test results. Following the viewing of the sample DTC disclaimer message, participants were asked a series of questions regarding self-reported systematic processing of the message and their interest/willingness to undergo DTC genetic testing (Time 3).

Demographics

Demographic data collected included gender (1 = male, 0 = female), age (continuous from age 18 to 65+) and race/ethnicity (1 = non-Hispanic White, 0 = Black/African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multi-racial). Education was measured as the time spent in school on a scale from 1 = never attended school or only attended kindergarten to 6 = attended college for four or more years. The education variable was treated as a continuous variable per recent arguments [12].

DTC genetic testing experience

Two original items measured DTC genetic testing experience for the study participants and/or their partner or family members at baseline [13], including “Have you ever had a DTC genetic test?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No) and “Has your partner or any other family member ever had a DTC genetic test?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Systematic processing

Measures of self-reported systematic processing were from a previously validated scale [14] and were administered after viewing the DTC disclaimer message. Five items were measured from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and included items such as “While reading the paragraph I skimmed through” and “While reading the paragraph I tried to think about the importance of the information for my daily life”. Two items were reverse coded to match the direction of the other items. The mean of the items was used in the analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.74, M = 3.48, SD = 0.67).

Attitudes toward DTC genetic testing

Three items measuring attitudes towards DTC genetic testing were included based on theory of reasoned action measures (Ajzen, 1991). Based on a 1–10 semantic differential scale, participants were asked about the degree to which “receiving DTC genetic testing would be” worthless/valuable, harmful/beneficial, or not useful/useful; this was done before and after being exposed to the sample DTC disclaimer message. The mean of the three items at Time 2 (Cronbach’s α = 0.80; M = 7.43, SD = 2.50) and at Time 3 (M = 6.72, SD = 2.64) were used in the analyses.

DTC interest

An original item measured DTC genetic testing interest (“How interested are you in DTC genetic testing?”) before (Time 2) and after (Time 3) being exposed to the sample DTC disclaimer message. Responses ranged from 1 (not interested) to 5 (very interested). The mean of the items at Time 2 (M = 3.37, SD = 1.36) and Time 3 (M = 3.27, SD = 1.31) were used in the analyses.

Outcome expectancy

Outcome expectancy was measured using an item from an existing scale [15, 16]. Based on a 1 to 7 semantic differential scale, participants were asked if “getting a DTC genetic test would have” a lot more negatives than positives [1] or a lot more positives than negatives [7]. This item was asked at Time 2 (M = 5.14, SD = 1.51) and Time 3 (M = 5.06, SD = 1.55), following exposure to the DTC disclaimer message.

Genetics knowledge

We drew on a subset of relevant items used in the Impact of Personal Genetics (PGEN) study, which were chosen from several existing scales for use in a healthy population seeking DTC genetic testing [17]. Participants were asked nine genetic knowledge questions before being exposed to the DTC disclaimer message. The nine items were then scored as correct/incorrect and summed to create a knowledge score of 1–9 depending on how many questions the participants answered correctly. The mean was used in the analyses (M = 5.91, SD = 1.73).

Behavioral intentions

Two original items measured participants’ intention of learning more about and pursing DTC genetic testing. Responses ranged from 1 (not likely at all) to 6 (extremely likely). The participants were asked about their intention to search for more information regarding DTC genetic testing at Time 2 (M = 3.44, SD = 1.91) and their intention to pursue DTC genetic testing exposure at Time 2 (M = 3.25, SD = 1.13). Then, following exposure to the DTC disclaimer message at Time 3, participants were again asked about their intention of seeking more information (M = 3.34, SD = 1.24), as well as their intention to pursue DTC genetic testing (M = 3.16, SD = 1.20).

Statistical analysis plan

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and correlations) examined the data and demographic characteristics. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze the data because the models tested included both categorical (i.e., message condition) and continuous variables. All analyses controlled for message condition, age, gender, minority status, education level, and past DTC genetic testing experience.

Results

Sample characteristics

675 individuals accessed the online survey. However, some participants did not complete the online survey (N = 3); were not randomized to a condition or dropped out (N = 73); took less than five minutes to complete the survey (N = 138); failed a manipulation check (N = 55); or were younger than 18 (N = 1). Thus, our effective sample size was N = 405.

The unweighted mean age of participants was 46.91 years (SD = 15.13, Range = 18–65+ years of age). The majority were female (55.7%; n = 225) and non-Hispanic White (68.7%; n = 310). Over 40% (n = 166) attended college for four or more years. Over 15% (n = 64) of participants had DTC genetic testing prior to the study and 18% (n = 73) had a partner or other family member who had received DTC genetic testing. Before testing study hypotheses, we examined differences across message conditions on each of our model variables. As shown in Table 1, no differences were detected across conditions on systematic processing, outcome expectancies, or interest in DTC genetic testing (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Results. Analysis of covariance examining predictors of self-reported systematic processing, outcome expectancies, and interest in pursuing direct to consumer (DTC) genetic testing.

| Dependent Variablesa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Processing (T3) | Outcomes Expectancies (T3) | DTC Genetic Testing Interest (T3) | ||||

| Independent Variables | F (DF) | P | F (DF) | p | F (DF) | p |

| Message Condition | 1.54 (4) | 0.19 | 0.52 (4) | 0.724 | 2.20 (4) | 0.068 |

| Previous DTC Experiencea | 0.02 (1) | 0.882 | 4.25 (1) | 0.040* | 11.32 (1) | 0.001* |

| Ageb | 0.73 (1) | 0.395 | 4.18 (1) | 0.042* | 15.14 (1) | 0.000* |

| Malec | 0.48 (1) | 0.489 | 0.02 (1) | 0.890 | 0.27 (1) | 0.601 |

| Educationd | 0.00 (1) | 0.954 | 0.36 (1) | 0.548 | 5.55 (1) | 0.019* |

| Non-Hispanic Whitee | 10.04 (1) | 0.002* | 0.06 (1) | 0.804 | 0.16 (1) | 0.693 |

| Genetics Knowledge | 5.93 (1) | 0.015* | 3.8 (1) | 0.052 | 7.24 (1) | 0.007* |

| Attitudes Towards DTC Genetic Testing (T1)f | 59.64 (1) | 0.000* | 3.88 (1) | 0.050* | 0.91 (1) | 0.341 |

| Disclaimer Systematic Processing | - | - | 0.00 (1) | 0.967 | 17.67 (1) | 0.000* |

| Attitudes Towards DTC Genetic Testing (T3)g | - | - | 97.87 (1) | 0.000* | 15.13 (1) | 0.000* |

| Outcome Expectancy of DTC Genetic Testing | - | - | - | - | 33.40 (1) | 0.000* |

*Statistically significant findings (p < 0.05).

aYes/no response.

bContinuous variable.

c1 = male, 0 = female.

d1 (never attended school or only attended kindergarten) - 6 (attended college for four or more years) scale.

e1 = non-Hispanic White, 0 = Black/African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multi-racial.

fMeasured at Time 1 (Baseline).

gMeasured at Time 3 (following exposure to the sample DTC disclaimer message).

Predictors of self-reported systematic processing

Participants who identified as a race or ethnicity other than non-Hispanic White (M = 3.72, SD = 0.65) engaged in significantly more self-reported systematic processing of the DTC disclaimer message than non-Hispanic White participants (M = 3.52, SD = 0.68) (Table 1; β = 0.26, SE β = 0.08, p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant relationship was detected between genetics knowledge and systematic processing (β = 0.06, SE β = 0.02, p < 0.05); participants who had greater genetics knowledge scores at Time 2 self-reported that they processed the DTC disclaimer message more systematically (H1 supported). Lastly, a significant relationship was detected between DTC genetic testing attitudes and systematic processing (β = 0.11, SE β = 0.01, p < 0.05). Participants who reported more positive attitudes towards DTC genetic testing at Time 2 self-reported that they engaged in more systematic processing of the DTC disclaimer message (H2 unsupported).

Predictors of outcome expectancy of DTC genetic testing

We compared outcome expectancies for DTC genetic testing following exposure to the DTC disclaimer message (Time 3). There was a significant relationship detected between personal DTC genetic testing experience and outcome expectancies (Table 1; β = 0.35, SE β = 0.17, p < 0.05). Participants who previously had undergone DTC genetic testing (M = 5.63, SD = 1.41) reported greater outcome expectancies than those reporting no prior experience with DTC genetic testing (M = 5.03, SD = 1.53, p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant relationship was detected between age and outcome expectancy (β = −0.01, SE β = 0.01, p < 0.05), such that younger participants reported greater outcome expectancies than older participants after exposure to the disclaimer message.

Significant relationships were also detected between outcome expectancy and DTC genetic testing attitudes at Time 2 (β = −0.09, SE β = 0.05, p < 0.05) and at Time 3 (β = 0.43, SE β = 0.04, p < 0.05). Interestingly, attitudes measured at Time 2 were negatively related whereas attitudes at Time 3 were positively related, which may have been due to exposure to the message. Systematic processing and outcome expectancy were not significantly related (β = −0.00, SE β = 0.10, p > 0.05) (H3 unsupported).

Predictors of interest in DTC genetic testing

A significant relationship was detected between personal DTC genetic testing experience and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing (Table 1; β = 0.45, SE β = 0.13, p < 0.05). Participants who had previously undergone DTC genetic testing reported greater interest to pursue DTC genetic testing after being exposed to the DTC disclaimer message (M = 3.95, SD = 1.11) than those who reported no prior experience with DTC genetic testing (M = 3.11, SD = 1.31). Additionally, age and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing were significantly related (β = −0.02, SE β = 0.00, p < 0.05) with younger participants reporting greater interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing than older participants.

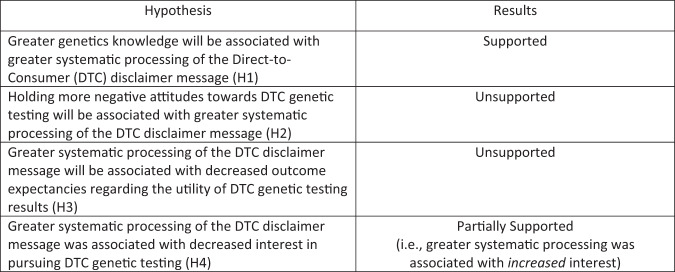

Education level and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing were related (β = 0.14, SE β = 0.06, p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant negative relationship was detected between genetics knowledge and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing (β = −0.10, SE β = 0.04, p < 0.05). Attitudes of DTC genetic testing at Time 3 and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing were positively related (β = 0.15, SE β = 0.04, p < 0.05). A significant positive relationship between systematic processing and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing also was detected (β = 0.33, SE β = 0.08, p < 0.05) (H4 partially supported). Lastly, a significant relationship was found between outcome expectancy at Time 3 and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing (β = 0.24, SE β = 0.04, p < 0.05). Figure 2 lists the hypotheses tested and associated result.

Fig. 2. Summary of hypotheses and associated results.

Study hypotheses and results. This figure summarizes each of the original study hypotheses and whether they were supported or unsupported after data collection and analysis as explained in the text.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to assess public knowledge, attitudes, outcome expectancies, and interest in DTC genetic testing before and after being exposed to a sample disclaimer message. We hypothesized that individuals with greater genetics knowledge (H1) and more negative attitudes towards DTC genetic testing (H2) will engage in deeper self-reported processing of DTC disclaimer messages. We further hypothesized that deeper processing of the DTC disclaimer message would be associated with decreased outcome expectancies (H3) and interest in DTC genetic testing (H4).

We found that individuals with higher genetic knowledge scores at Time 1 self-reported processing the DTC disclaimer message more systematically than those with lower genetic knowledge scores. This finding supports our hypothesis (H1) that individuals who have more knowledge about a topic will more actively engage in deeper processing of the content [9]. Participants who received higher genetic knowledge scores may have been more interested in genetics as a topic, and, therefore, may have better understood the content of the DTC disclaimer message, allowing for greater systematic processing.

Our second hypothesis (H2) was unsupported in that individuals who expressed more positive attitudes towards DTC genetic testing reported processing the DTC disclaimer message more systematically. We thought that participants with more negative attitudes towards DTC genetic testing would process the information more systematically to reaffirm their negative beliefs and/or limitations/risks [9]. However, the opposite proved to be true since positive attitudes imply greater interest and motivation to process the message systematically [9], which may help explain these results.

Our third hypothesis (H3) was unsupported in that there was no relationship between outcome expectancies and self-reported systematic processing. We expected systematic processing to be associated with a deeper understanding of the DTC disclaimer message content and, therefore, decreased outcome expectancies [3]. Since the sample DTC disclaimer message was short in length, and explicitly states the limitations of DTC genetic testing, we expected that those who fully understood the content would express lower outcome expectancies. Because positive attitudes towards DTC genetic testing were quite high, this may have overshadowed any limitations discussed in the DTC disclaimer message and, subsequently, their outcome expectancies did not waiver.

Lastly, our fourth hypothesis (H4) was partially supported with a significant relationship between self-reported systematic processing and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing, but not in the direction expected. We thought that individuals who use more systematic processing would report less interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing because they would understand the limitations and would, subsequently, report less interest in pursuing it [3], when the opposite proved to be true. In comparing H1 and H3, greater genetics knowledge scores were associated with greater systematic processing and more interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing. This finding directly contrasts with work by Stewart et. al who found that lower genetics knowledge was associated with more interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing options [11]. It is possible that other factors, such as prior interest or experience with DTC genetic testing, overshadowed the processing of the disclaimer message, or that participants with positive attitudes towards DTC genetic testing had a greater interest in pursuing it regardless of the disclaimer message. Indeed, strong attitudes, which can guide behavior, can be very difficult to change [18]. Furthermore, it is possible that individuals overestimated the amount of systematic processing they actually did due to a self-presentation bias. Additionally, participants who had previously undergone DTC genetic testing may have reported greater interest in testing after reading the disclaimer message to avoid cognitive dissonance; if they had already invested time and money into DTC genetic testing, they might have been hesitant to acknowledge the limitations of testing, as provided in the disclaimer message.

Overall, genetic knowledge seems to be a strong predictor of self-reported systematic processing of DTC disclaimer messages. Systematic processing of a message requires significant comprehension of the content in order to understand and scrutinize the relevant information and, subsequently, use all of the information presented to form an opinion [7]. There are multiple factors that may impact individuals’ prior knowledge of a message and whether they use systematic processing. First, systematic processing happens when individuals are motivated to do so, perhaps due to personal involvement with the content [19]. That is, the personal relevance of message contents may encourage more detailed message processing as compared to an individual without previous personal involvement [20]. Second, motivation about a message can also act as a predictor of knowledge, which can then lead to more systematic processing [9]. Therefore, if an individual is motivated to process and pay more attention to the message information, they are more likely to already have prior understanding of the content, allowing the use of systematic processing to comprehend and analyze the information [19]. Lastly, one’s ability to process, or the cognitive resources an individual has to process a message, is an important predictor of systematic processing, including literacy level [20]. That is, messages written at a lower literacy level may allow more readers to engage in more systematic processing when reviewing the message as this leads to more comprehension and knowledge gain [9].

To improve consumers’ experiences and increase their understanding of the limitations of DTC genetic testing, DTC genetic testing companies could consider modifying the reading level of their disclaimer messages to reach a wider range of consumers. A study done by Lachance et al. found that the quality of educational materials provided by 29 different DTC genetic testing companies varied widely in terms of their understandability by the general public, partly due to the differences in reading levels between the companies’ materials [21]. By decreasing the reading level, the disclaimer message and/or educational materials may be easier to understand and systematically process by consumers [20]. Having a more accessible disclaimer message may also help to build trust between the company and consumers. However, a study by Byron et al. investigating how individuals react to disclaimer messages regarding different kinds of cigarettes and perceptions on the level of risk found that many individuals simply ignore disclaimers, while others express doubt about the disclaimer messages or their accuracy [22]. This suggests that, even if a disclaimer message is written at a more accessible reading level, it still may not increase participants’ knowledge about the product. Nevertheless, efforts to further increase genetic knowledge within the general public may, in turn, make the disclaimer messages provided by DTC companies easier to understand and process systematically. At Time 1, the average genetic knowledge score of participants in our study was 5.91 out of 9.0. For comparison, the PGEN study from which our genetic knowledge survey was adapted showed that participants reported average genetic knowledge score of 8.51 out of 9.0 [17]. This genetic knowledge difference may be because the PGEN study participants were receiving DTC genetic testing, which was not a requirement for our study. Dougherty et al. acknowledged the deficiency of formal genetics education in the school system and the poor effect that has on the public understanding of basic genetics and proposed some alternatives to increasing general genetics knowledge, such as use of the media and the Internet [23]. Perhaps including more interactive pre- and post-test educational materials, at an appropriate reading level, on the DTC genetic testing websites could improve general genetics knowledge. If baseline genetic knowledge could be improved on a general public health level by implementing more genetics education in the school system and, more directly, by providing pre-test education modules on DTC genetic testing websites, perhaps consumers may be able to systematically process DTC disclaimer messages more effectively.

A number of novel study findings suggest further inquiry, such as the interaction between minority status, age, or education levels with self-reported DTC disclaimer processing and interest in pursuing DTC genetic testing. Additionally, study methodology could be expanded to include actual DTC disclaimer messages, and in relation to the DTC genetic testing consent process. Better understanding of the user consent process and what motivates individuals to read (or not to read) DTC disclaimer messages, may impact the process and, therefore, improve the overall experience and user outcomes.

Study limitations include that the majority of participants were white, non-Hispanic women, so results may not be generalizable to the general population. Of the original 675 survey participants, a significant percentage (40%) were excluded from analysis for multiple reasons (noted above). The study design also provided different conditions than what individuals may experience in the real world setting when seeking DTC genetic testing, as the disclaimer message stood alone. Therefore, study participants may have spent more time on the disclaimer message in the study context than in the real-world setting.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

MR: conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. SH: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing. AP: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing. KS: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing.

Funding

There was no specific funding associated with this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41431-023-01411-y.

References

- 1.Rosenberg J. As DTC genetic testing grows among consumers, insurers are beginning to get on board. Am J Manag Care. 2019 April 22, 2019.

- 2.23andME. Do You Speak BRCA? 2020. Available from: https://www.23andme.com/brca/.

- 3.Gollust SE, Hull SC, Wilfond BS. Limitations of direct-to-consumer advertising for clinical genetic testing. Jama. 2002;288:1762–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koeller DR, Uhlmann WR, Carere DA, Green RC, Roberts JS, Group PGS. Utilization of genetic counseling after direct-to-consumer genetic testing: findings from the impact of personal genomics (PGen) study. J Genet Counsel. 2017;26:1270–9. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0106-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moscarello T, Murray B, Reuter CM, Demo E. Direct-to-consumer raw genetic data and third-party interpretation services: more burden than bargain? Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2019;21:539–41. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandy-Connor S, Guiltinan J, Krempely K, LaDuca H, Reineke P, Gutierrez S, et al. False-positive results released by direct-to-consumer genetic tests highlight the importance of clinical confirmation testing for appropriate patient care. Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2018;20:1515–21. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaiken S, Liberman A, Eagly A. Heuristic and systematic processing within and beyond the persuasion context. Veleman J, Bargh J, editors. New York: Guildford; 1989.

- 8.Chaiken S. The heuristic model of persuasion. Zanna M, Olson J, Herman C, editors. Hillsdale, NJ 1987.

- 9.Hitt R, Perrault E, Smith S, Keating DM, Nazione S, Silk K, et al. Scientific message translation and the heuristic systematic model: insights for designing educational messages about progesterone and breast cancer risks. J Cancer Educ: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2016;31:389–96. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0835-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaiken S, Maheswaran D. Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity, and task importance on attitude judgment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66:460–73. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart KFJ, Kokole D, Wesselius A, Schols A, Zeegers MP, de Vries H, et al. Factors associated with acceptability, consideration and intention of uptake of direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a survey study. Public Health Genom. 2018;21:45–52. doi: 10.1159/000492960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robitzsch A. Why Ordinal Variables Can (Almost) Always Be Treated as Continuous Variables: Clarifying Assumptions of Robust Continuous and Ordinal Factor Analysis Estimation Methods. Frontiers in Education. 2020;5.

- 13.Papacharissi Z, Mendelson A. An exploratory study of reality appeal: uses and gratifications of reality TV shows. J Broadcasting Electron Media. 2007;51:355–70. doi: 10.1080/08838150701307152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen S, Chaiken S. The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. Chaiken S, Trope Y, editors. New York: Guilford;1999.

- 15.Afifi WA, Morgan SE, Stephenson MT, Morse C, Harrison T, Reichert T, et al. Examining the decision to talk with family about organ donation: applying the theory of motivated information management. Commun Monogr. 2006;73:188–215. doi: 10.1080/03637750600690700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahlor L. PRISM: a planned risk information seeking model. Health Commun. 2010;25:345–56. doi: 10.1080/10410231003775172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carere DA, Kraft P, Kaphingst KA, Roberts JS, Green RC. Consumers report lower confidence in their genetics knowledge following direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing. Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2016;18:65–72. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krosnick JA, Petty RE. Attitude strength: an overview. Attitude strength: antecedents and consequences. Ohio State University series on attitudes and persuasion, Vol. 4. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1995. p. 1–24.

- 19.Chaiken S, Maheswaran D. Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity and task importance on attitude judgment. J Per Soc Psycho. 1994;66:430–73. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eagly A, Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1993.

- 21.Lachance CR, Erby LA, Ford BM, Allen VC, Jr, Kaphingst KA. Informational content, literacy demands, and usability of websites offering health-related genetic tests directly to consumers. Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2010;12:304–12. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181dbd8b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byron MJ, Hall MG, King JL, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Reducing nicotine without misleading the public: descriptions of cigarette nicotine level and accuracy of perceptions about nicotine content, addictiveness, and risk. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:S101–S7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty MJ, Lontok KS, Donigan K. The critical challenge of educating the public about genetics. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014;2:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s40142-014-0037-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.