Abstract

Ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot osteoarthritis (OA) is most commonly posttraumatic and tends to become symptomatic in younger patients. It often results from instability due to insufficiency of supportive soft tissue structures, such as ligaments and tendons. Diagnostic imaging can be helpful to detect and characterize the distribution of OA, and to assess the integrity of these supportive structures, which helps determine prognosis and guide treatment. However, the imaging findings associated with OA and instability may be subtle and unrecognized until the process is advanced, which may ultimately limit therapeutic options to salvage procedures. It is important to understand the abilities and limitations of various imaging modalities used to assess ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot OA, and to be familiar with the imaging findings of OA and instability patterns.

Keywords: Ankle, Hindfoot, Midfoot, Cone-beam computed tomography, MRI, Osteoarthritis, Instability

Introduction

Ankle pain is reported in 9–15% of the general adult population and is often associated with osteoarthritis (OA) [1, 2]. OA of the ankle has an estimated prevalence of 1%. Unlike knee and possibly hip OA, which tend to be idiopathic, ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot OA are usually posttraumatic, and about 70% of patients with ankle OA report an antecedent trauma with resultant instability [3]. Other etiologies, including OA superimposed on rheumatoid arthritis (RA), idiopathic OA, and OA secondary to arthroplasty or arthrodesis of adjacent joints due to biomechanical load transfer, comprise most of the remaining 30% of cases [4]. Patients with symptomatic ankle and foot OA also tend to be younger than those with knee or hip OA. The reported prevalence of symptomatic, radiographically-visible OA in patients younger than 50 years of age is up to 3.4%, and up to 9.2% in professional athletes [5, 6].

The goals of OA treatment are to reduce pain, restore maximum function, and optimize biomechanical loads. Diagnostic imaging has become an increasingly important tool to characterize the distribution and degree of OA [7]. Furthermore, imaging can help assess osseous alignment as well as the integrity of supportive soft tissue structures, such as tendons and ligaments, which can be associated with patterns of instability and OA [8]. Imaging findings may facilitate diagnosis and help guide optimal treatment strategies. Therefore, it is important to understand the various imaging modalities used in diagnosing ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot OA and findings that may suggest specific patterns of instability and soft tissue insufficiency.

Diagnostic Imaging

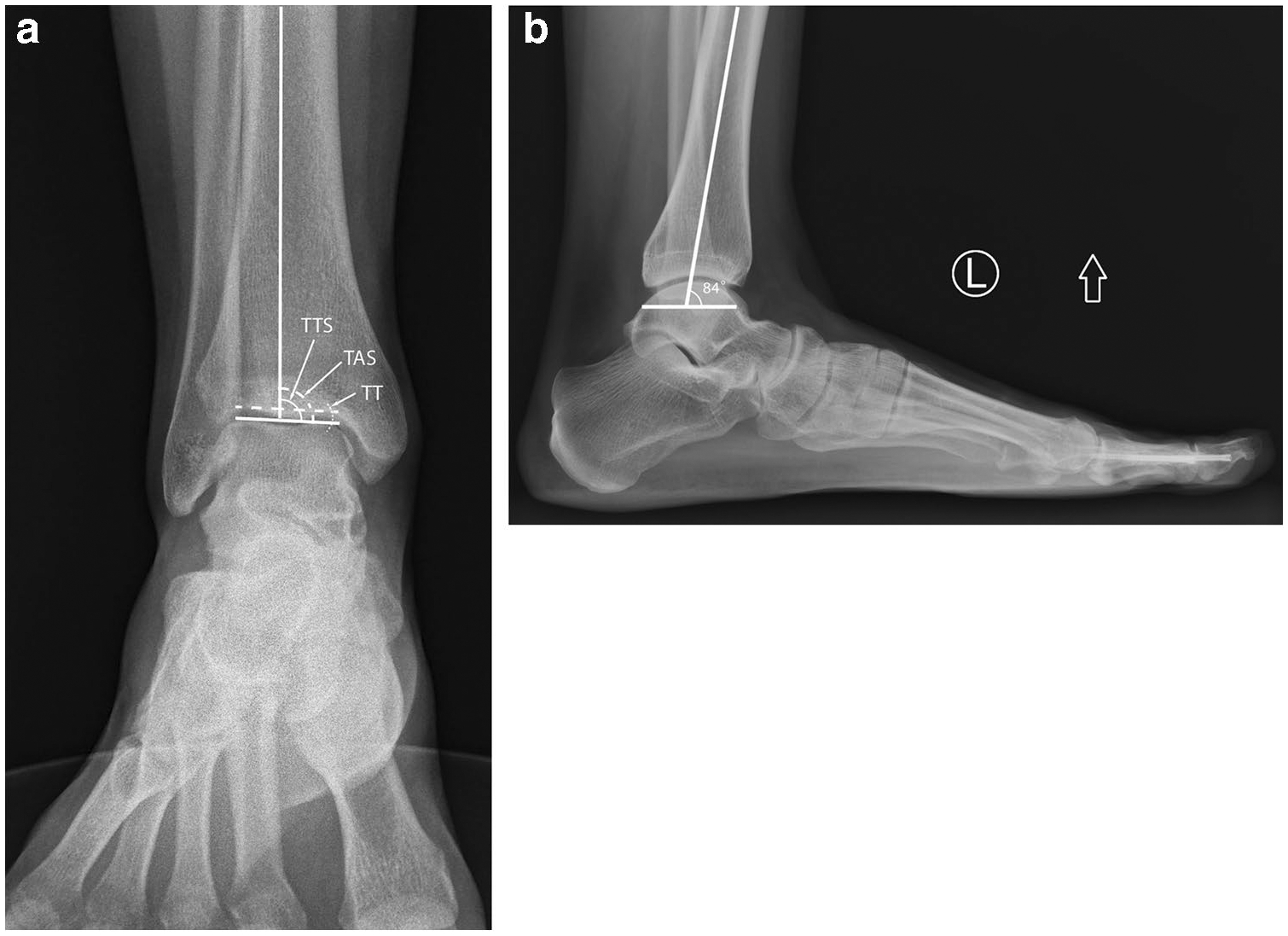

Several imaging modalities, including conventional radiography (CR), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound (US), and bone scintigraphy, have been used to diagnose and characterize OA, quantify chondral loss, and detect osseous malalignment, which can be associated with instability. MRI and US in particular are useful in examining soft tissue structures that preserve ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot stability [9]. Initial assessment of ankle and foot pathology begins with CR, generally with weight-bearing to assess osseous alignment during physiologic stresses. Radigraphy is widely available and can be done quickly and reproducibly, which allows for serial comparisons to detect progressive malalignment and joint space narrowing (JSN) (Fig. 1). Radiography is less prone to metal-related artifacts compared with MRI and CT and can be helpful to assess for orthopedic hardware malalignment or other complications [10].

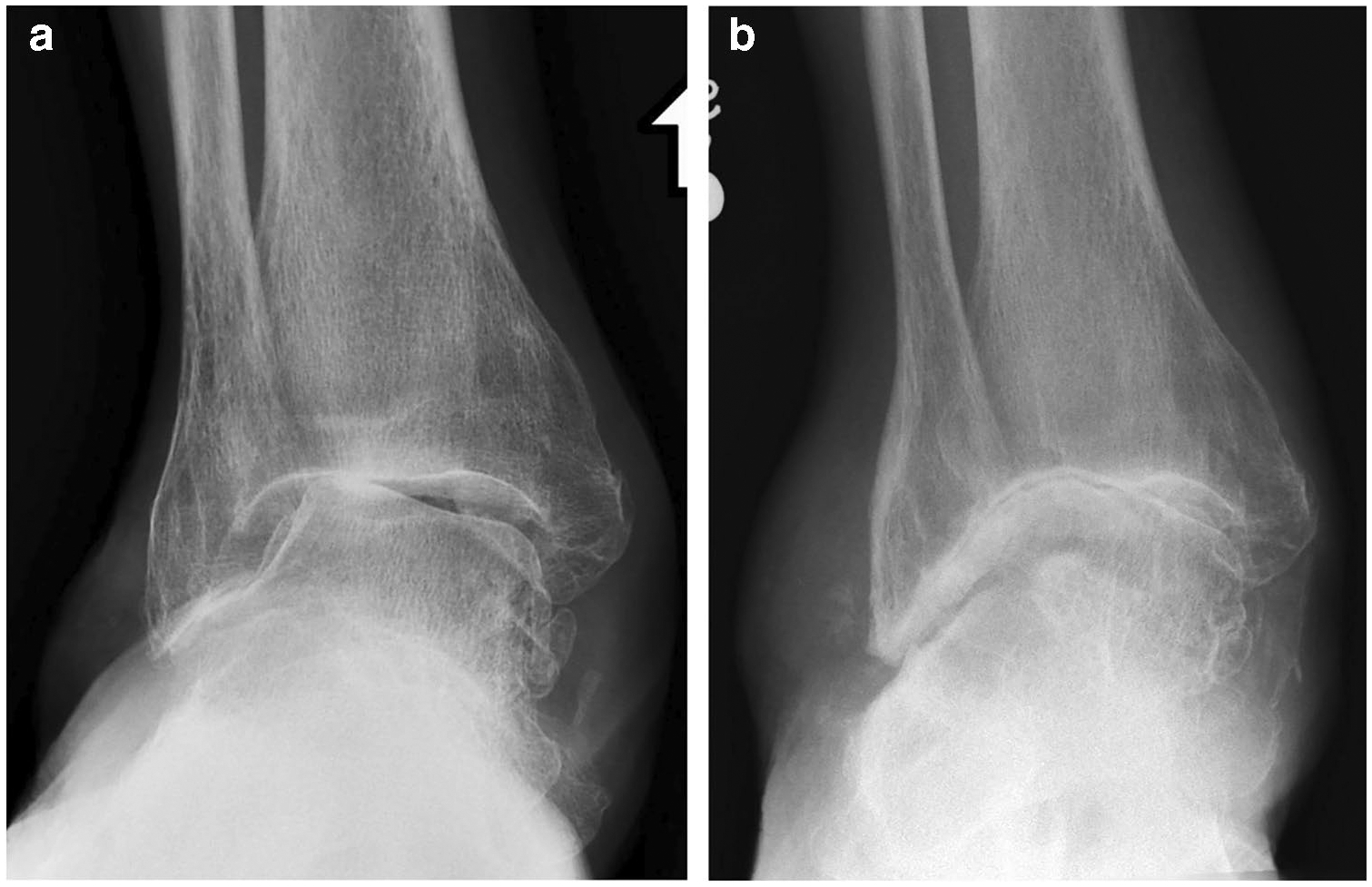

Fig. 1.

A 65-year-old male patient with history of chronic pes planovalgus deformity, ankle pain, and stiffness had an AP weightbearing radiograph a showing moderate osteoarthritis (OA) of the ankle joint with valgus instability, including lateral predominant joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and marginal osteophytes. Six years later, the patient presented with worsening pain and decreased range of motion. b Subsequent AP weight-bearing radiograph demonstrates progressive OA with worsening joint space narrowing and marked osseous remodeling resembling a ball-and-socket joint morphology

Stress radiography and fluoroscopy are frequently used to detect malalignment patterns that are not visible on routine imaging. In addition to weight-bearing radiographs, common stress views include anteroposterior (AP) ankle stress imaging with a laterally-directed force on the hindfoot either with manual manipulation or by gravity, which may reveal medial tibiotalar or distal tibiofibular diastasis in the setting of deltoid or syndesmotic ligament injuries, medially directed force on the hindfoot which may indicate lateral ligamentous complex insufficiency (Fig. 2), and sagittal stress imaging, in which anteriorly directed force on the heel resulting in anterior talar dome subluxation with respect to the tibial plafond indicates anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) insufficiency (Fig. 3) [11].

Fig. 2.

A 29-year-old female patient with right lateral ankle pain and instability after several ankle sprains had an AP weight-bearing radiograph of the ankle (not shown) demonstrating normal tibiotalar alignment and preserved ankle joint space. A subsequent AP radiograph with varus stress on the hindfoot shows mild medial tibiotalar OA (white arrowhead) with varus angulation of the talus, resulting in lateral tibiotalar joint space widening (black arrowhead). There is medially directed force on the hindfoot (large white arrow) during the stress view. These findings are consistent with lateral ligamentous complex insufficiency

Fig. 3.

A 74-year-old male patient with history of repetitive left ankle sprains, pain, and sensation of instability had a lateral ankle radiograph showing mild tibiotalar OA with posterior tibial plafond marginal osteophytes (white arrowhead) and anterior talar dome subluxation. Normally, the talar dome is centered on the tibial plafond and the arcs of curvature are parallel, resulting in a uniform joint space with joint congruence. In this case, the anterior subluxation of the talus causes posterior tibiotalar widening of 4 to 5 mm (black line), called the anterior drawer sign, which indicates anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) insufficiency. Occasionally, stress imaging with an anteriorly directed force may be helpful to detect anterior talar dome subluxation. On this radiograph, the large white arrow demonstrates the direction of force during stress imaging

While there are several benefits of CR in assessing ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot pathology, this technique results in planar 2-dimensional (2D) representations of complex 3-dimensional (3D) anatomic structures, leading to an overlap of osseous structures that can obscure pathology. Advanced imaging modalities use cross-sectional anatomical depictions to detect, characterize, and accurately localize more subtle abnormalities. In particular, CT provides rapid, contiguous, and thin-section stacks of cross-sectional images that can be reformatted in different planes to better delineate osseous anatomy and alignment. CT has high contrast resolution between bone and soft tissue, and high spatial resolution, making it an excellent modality to detect articular surface fractures, subchondral bone plate irregularity and JSN, and other signs of osteochondral damage [12]. Although metal used in many orthopedic constructs may result in a significant beam-hardening artifact, newer techniques such as iterative metal artifact reduction (IMAR) and dual-energy CT can reduce artifacts and improve visualization of bone and soft tissue surrounding the devices [13, 14].

Unlike radiography, traditional whole-body CT systems have not allowed weight-bearing. One of the most significant advancements in foot and ankle imaging over the last 10 years has been the routine clinical use of cone-beam CT (CBCT), which is a small footprint, self-shielded device that generates thin-section axial imaging of the ankle/hindfoot or forefoot that can be performed with weight-bearing, and the acquired images can be reformatted in other planes or used to obtain 3D reformatted images to better characterize osteoarticular relationships prior to therapeutic planning. Unlike CR, CBCT can also produce radiograph-like planar images without parallax and may produce more accurate and reproducible depictions of osseous alignment. CBCT also has high spatial resolution and high bone-to-soft tissue contrast resolution that provides excellent trabecular detail (Fig. 4). Finally, CBCT systems have metal artifact-suppressing techniques that help better characterize anatomy around orthopedic devices [15].

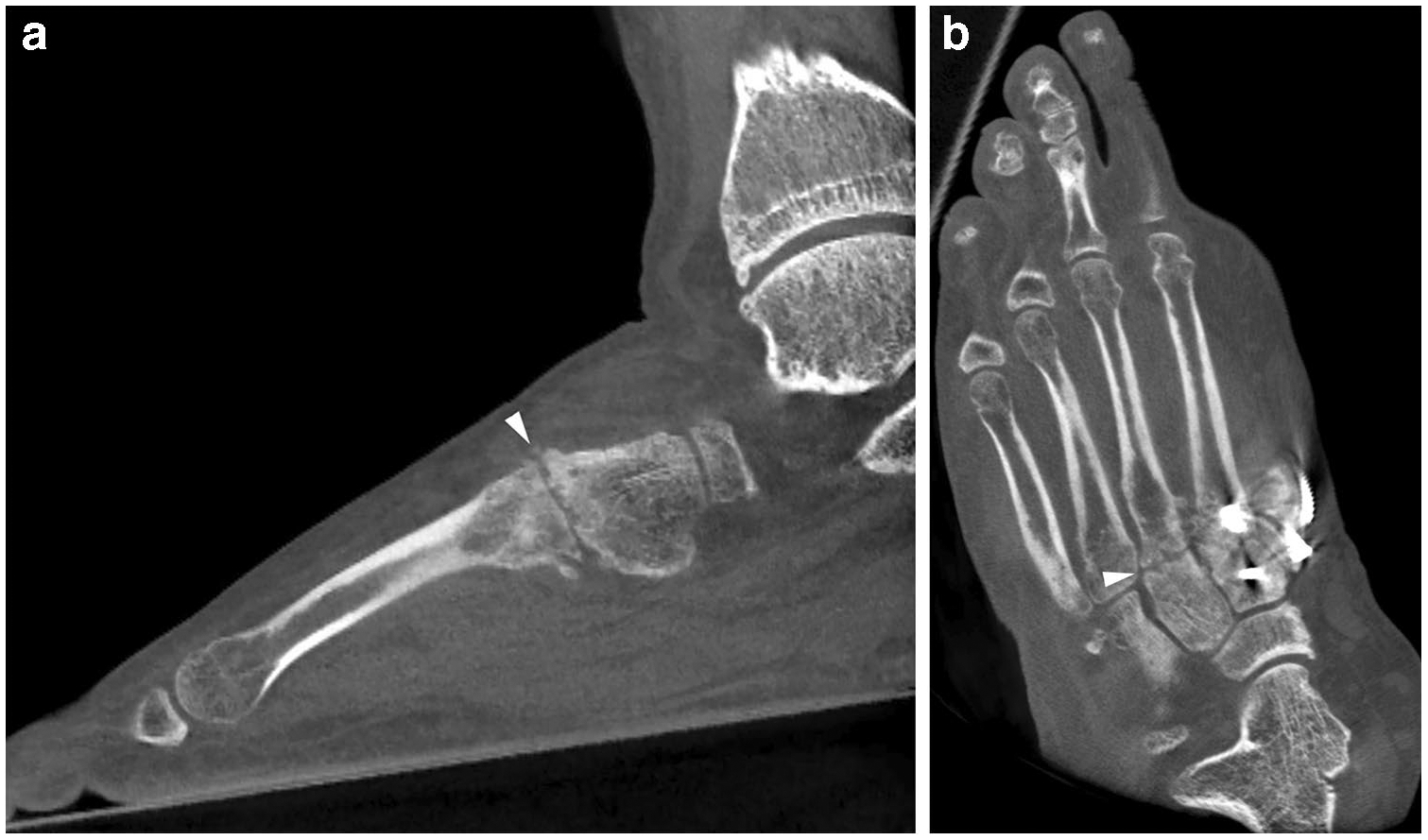

Fig. 4.

A 44-year-old female patient with chronic dorsal left midfoot pain and remote history of injury had radiographs and subsequent CBCT. Weight-bearing CBCT sagittal reformatted image of the hindfoot and midfoot in bone windows shows moderate dorsal first tarsometatarsal (TMT) OA (arrowhead) that was not visible radiographically (not shown). There is excellent cortical and trabecular spatial resolution although the soft tissues appear grainy and indistinct. The distal forefoot could not be included in the imaged field-of-view

CBCT systems have a few drawbacks. First, many alignment measurements reported on weight-bearing radiographs have not been validated yet for CBCT, so a direct comparison between these modalities may not be appropriate until these investigations have been performed. Furthermore, the soft tissue contrast is relatively poor, making it difficult to detect soft tissue swelling, effusions and fluid collections, and muscle atrophy. The imaged field-of-view is smaller than whole-body CT systems. Since it is frequently not possible to image the entire foot and ankle at one time, the technologist may need to determine whether to completely image the hindfoot/midfoot or the forefoot/midfoot based on the clinical indication [16].

MRI has high contrast resolution and is the modality of choice to evaluate injuries to the static and dynamic soft tissue stabilizers at each joint. Routine MRI often uses a combination of 2D spin echo techniques, including nonfat-saturated (NFS), high spatial resolution techniques, such as T1-weighted (T1W) and proton density-weighted (PDW) pulse sequences, which are better at characterizing surface contour, caliber, and alignment of the bones and supportive soft tissues; and fluid-sensitive, fat-saturated (FS) techniques, such as T2-weighted (T2W) and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences, which are sensitive to bone marrow edema (BME) and soft tissue edema that can indicate recent or ongoing injuries [17]. It is important to interpret the MRI in conjunction with the clinical history, since certain types of instability may produce particular patterns of soft tissue and osteoarticular damage.

In addition to assessing soft tissue pathology, MRI can diagnose and determine the degree of ankle and hindfoot OA, including the presence of osteophytes, intra-articular bodies, and synovitis, which can be associated with ankle impingement, and subchondral bone marrow lesions deep to areas of hyaline cartilage loss, which can represent independent pain generators. 3-Tesla (3 T) systems with dedicated coils tailored to the anatomy of interest are preferred over lower field strength scanners for improved assessment of hyaline cartilage due to their ability to produce higher signal-to-noise ratios that translate to higher spatial resolution. This improves the ability to separate the articulating surfaces of hyaline cartilage and to detect surface chondral loss and heterogeneity, which can indicate degeneration or chondral injury [18]. As a result, MRI has become better at characterizing cartilage defects and osteochondral lesions (OCLs), which serve as precursors to OA (Fig. 5). T2W thin-section gradient echo (GRE) sequences have been used to give a detailed anatomic assessment of the cartilage. However, GRE sequences may have limited utility compared with spin-echo sequences since GRE sequences often suffer from limited soft tissue contrast, and susceptibility artifact from mineralized cortex and bone trabeculae may obscure osseous pathology [19].

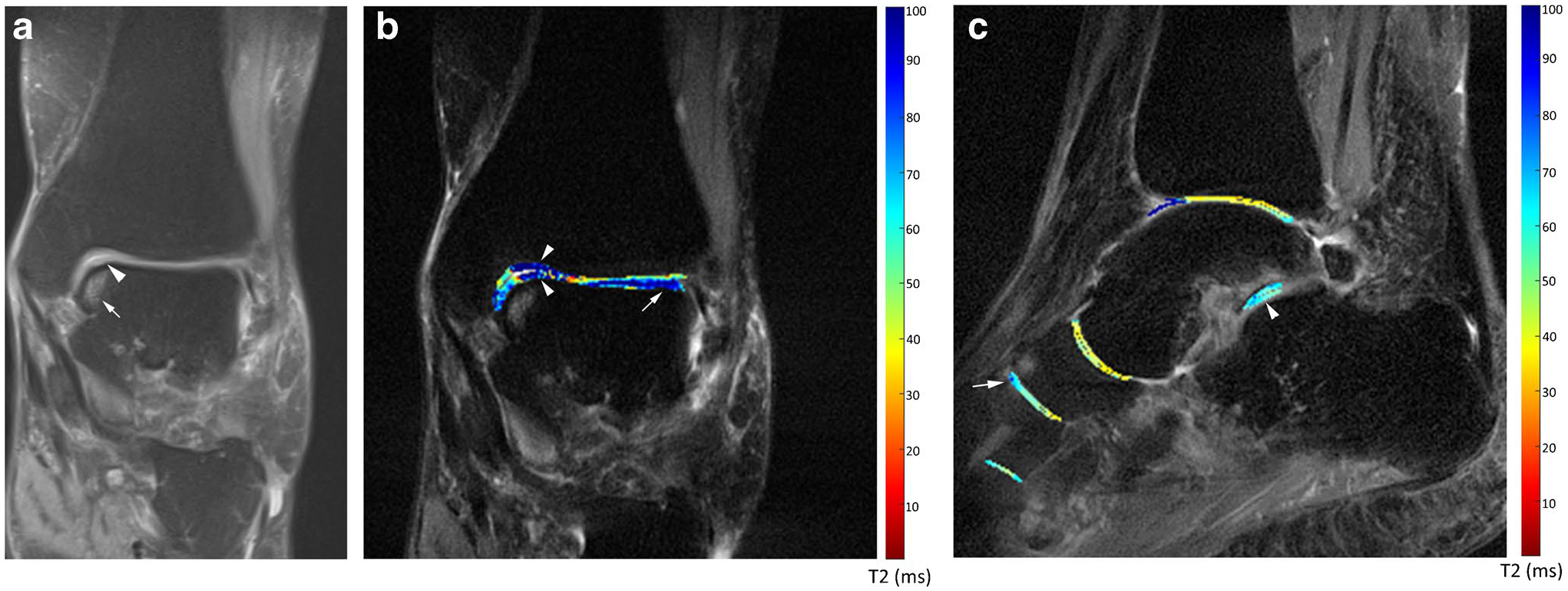

Fig. 5.

A 20-year-old female patient with remote severe ankle sprain and chronic medial right ankle pain. a Sagittal T1W nonfat-saturated (NFS) MR image of the hindfoot shows low signal along the equator of the medial talar dome in the area of an osteochondral lesion (arrowhead), indicating sclerosis. There is subchondral bone plate irregularity and subtle flattening, along with an anterior talar neck osteophyte. b Coronal T2W fat-saturated (FS) MR image of the hindfoot demonstrates moderate grade chondral loss overlying the medial talar dome osteochondral injury (arrowhead). c A slightly more lateral sagittal STIR MR image of the hindfoot shows a 4-mm posterior tibiotalar joint recess intra-articular body (arrowhead) that was not apparent radiographically

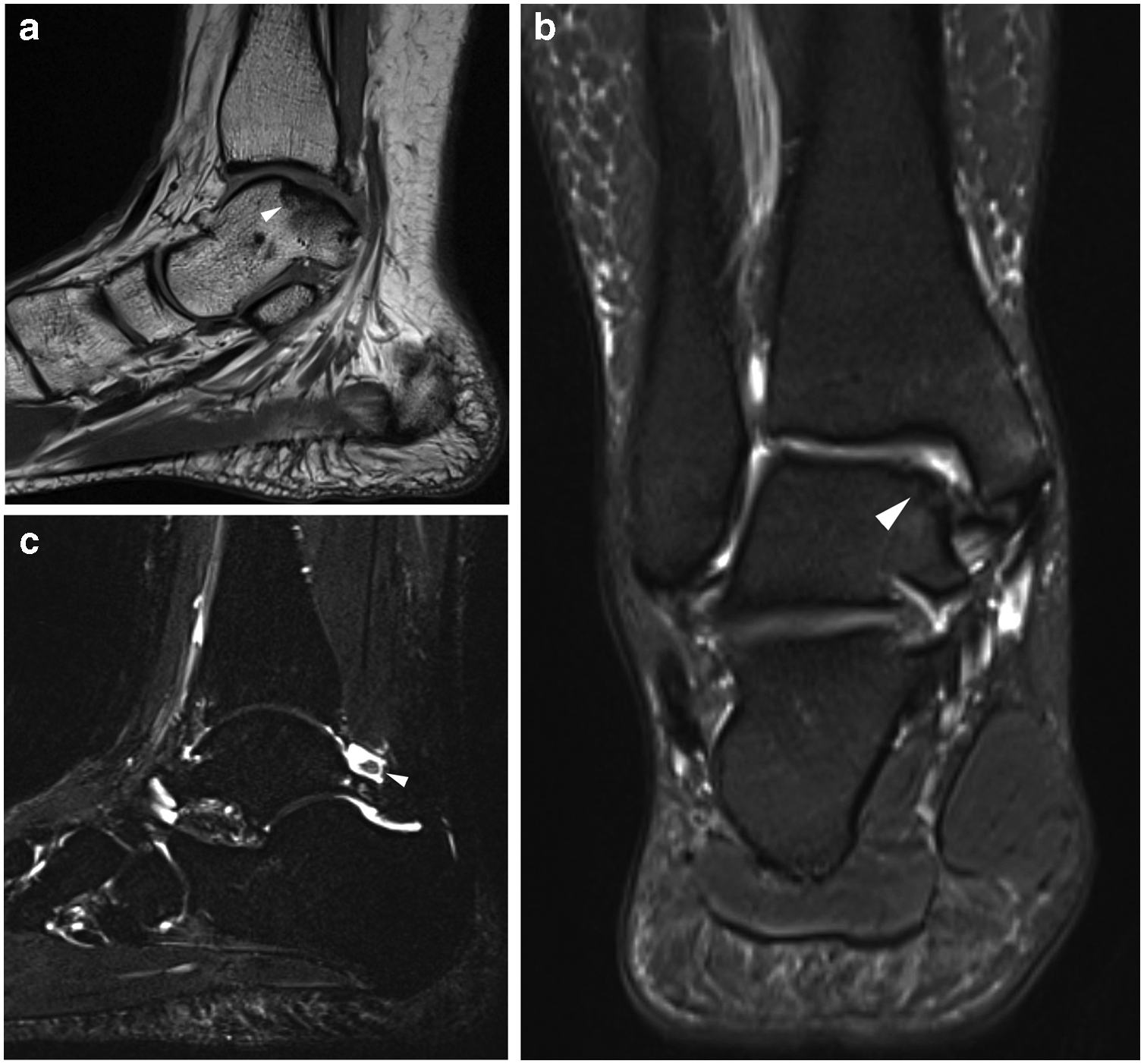

Cartilage mapping techniques, such as T2 mapping, T1 rho mapping, and delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI (dGEMRIC), are largely investigational but can be used in special clinical scenarios to detect areas of early cartilage damage. Chondral mapping techniques require specialized software on higher field strength systems such as 3 T scanners. When used for clinical purposes, T2 mapping may be the most practical since the software required to perform this technique may be more ubiquitous clinically than T1 rho mapping, and dGEMRIC requires intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast followed by a delay prior to imaging (Fig. 6) [20].

Fig. 6.

A 64-year-old female asymptomatic volunteer underwent T2 mapping of the ankle, hindfoot and midfoot. a Coronal PDW FS image of the hindfoot demonstrates medial talar dome chondral heterogeneity at its equator (arrowhead), with underlying subchondral bone marrow edema (BME) (arrow). b The coronal T2 map overlay of the same region on the T2W FS image shows chondral degeneration particularly of the medial talar dome and tibial plafond (arrowheads) in the region of the medial talar dome subchondral BME, with a predominantly dark blue color corresponding to elevated T2 values close to 100 ms as indicated on the side color bar. There is additional chondral degeneration along the lateral talar dome (arrow), which is not well seen on the coronal PDW image. The normal articular cartilage has a range of colors from orange to green corresponding to T2 values of approximately 35 to 50 ms and is best illustrated over the central and lateral tibial plafond. Please note there are lighter blue and green colors in the cartilage of the medial talar dome and tibial plafond. While this could reflect lesser chondral degeneration, the region overlying the talar dome directly overlies the subchondral marrow edema, and this heterogeneity could partially be related to collagen fiber anisotropy within the cartilage. c Sagittal T2 color map overlay on a T2W FS image of the ankle, hindfoot and midfoot shows chondral degeneration of the posterior subtalar joint (arrowhead), with predominantly light blue color corresponding to T2 values between 60 and 70 ms and associated posterior talar facet subchondral marrow edema. Similar chondral degeneration is suggested at the visible naviculocuneiform joint with dorsal navicular subchondral BME (arrow) and at the TMT joint

Direct MRI or CT arthrography has been used sparingly with the advent of high-resolution MRI on 3 T and higher field-strength units and compositional cartilage imaging. Arthrography techniques can be used to better characterize the stability of an in situ osteochondral fragment, better visualize surface chondral lesions, confirm intra-articular bodies that are outlined by contrast, and evaluate synovial proliferation in patients with impingement syndromes. Arthrography can also assess the distensibility of the joint capsule, which may be decreased in patients with arthrofibrosis or increased in patients with capsular/ligamentous tears and insufficiency (Fig. 7). However, arthrography is semi-invasive, requires joint puncture, and increases examination time [21].

Fig. 7.

A 14-year-old male patient sustained a right ankle twisting injury while playing soccer. Coronal T1W FS MR arthrographic image of the ankle through the talar dome shows a medial talar dome osteochondral injury. There is suggestion of partial thickness chondral loss over the osteochondral fragment (arrow) without convincing full-thickness loss. There is an intermediate signal curvilinear band in the subchondral bone of the osteochondral injury (arrowhead) that is lower in signal than the bright signal of the dilute gadolinium solution used for arthrography, likely reflecting granulation tissue. No convincing evidence for instability of the osteochondral fragment is present. The detection of instability is critical, since its presence would confirm the appropriateness of surgical intervention

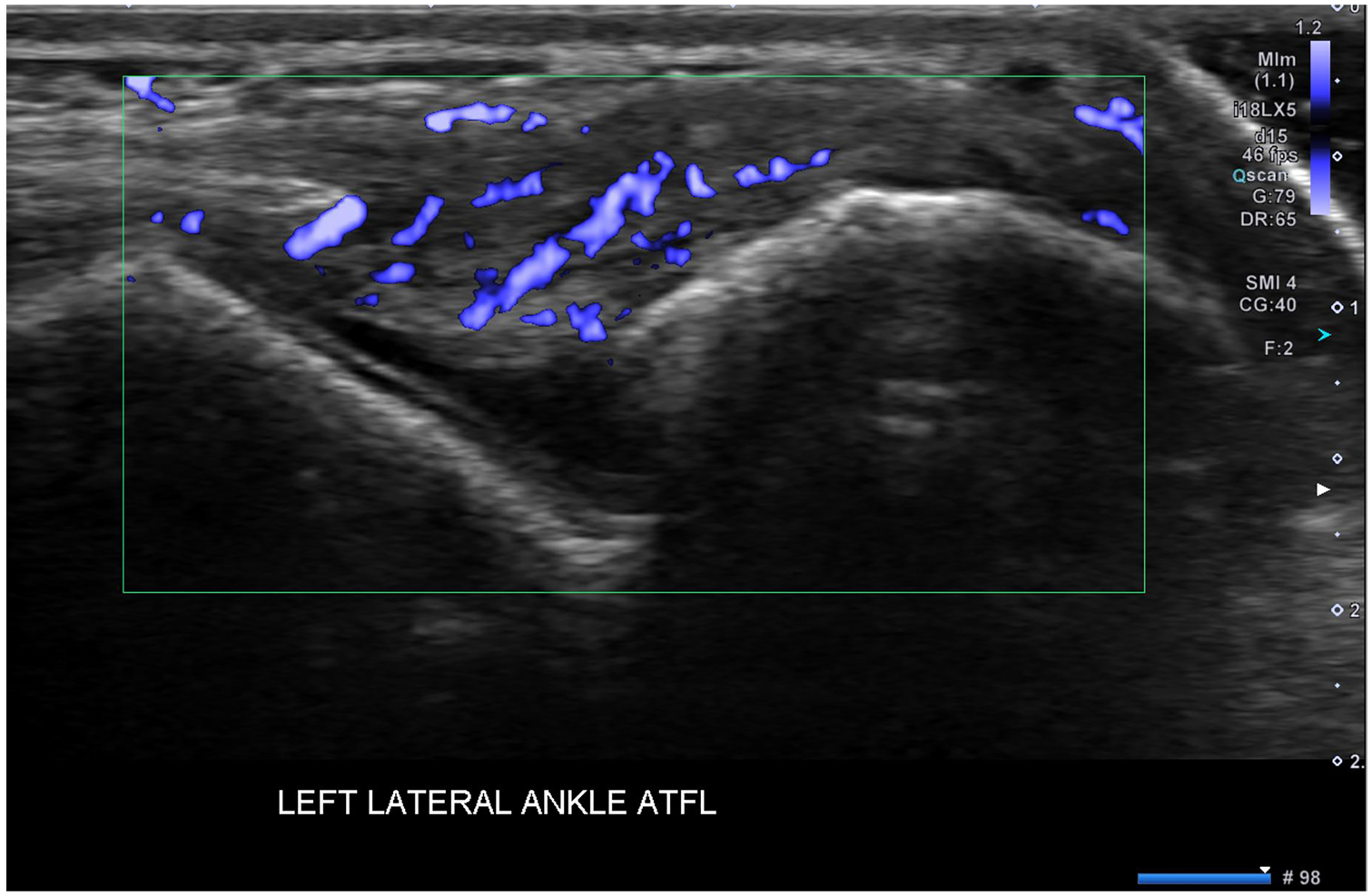

US is most helpful prior to the onset of significant OA in assessing the integrity of tendons and ligaments around the ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot and can help identify insufficiency and tearing, soft tissue impingement, and subluxation of the bones and soft tissues utilizing real-time dynamic stress maneuvers (Fig. 8) [22]. Additionally, US provides real-time, direct visualization of needle placement for targeted percutaneous injections and aspirations. In many American-based practices, musculoskeletal US is performed by subspecialist sonographers and interpreted by musculoskeletal radiologists or clinicians, such as rheumatologists. In other parts of the world, physicians commonly perform and interpret these studies, which can impact patient workflow. However, US may be more widely available than MRI and can be quickly obtained during the patient’s clinical visit.

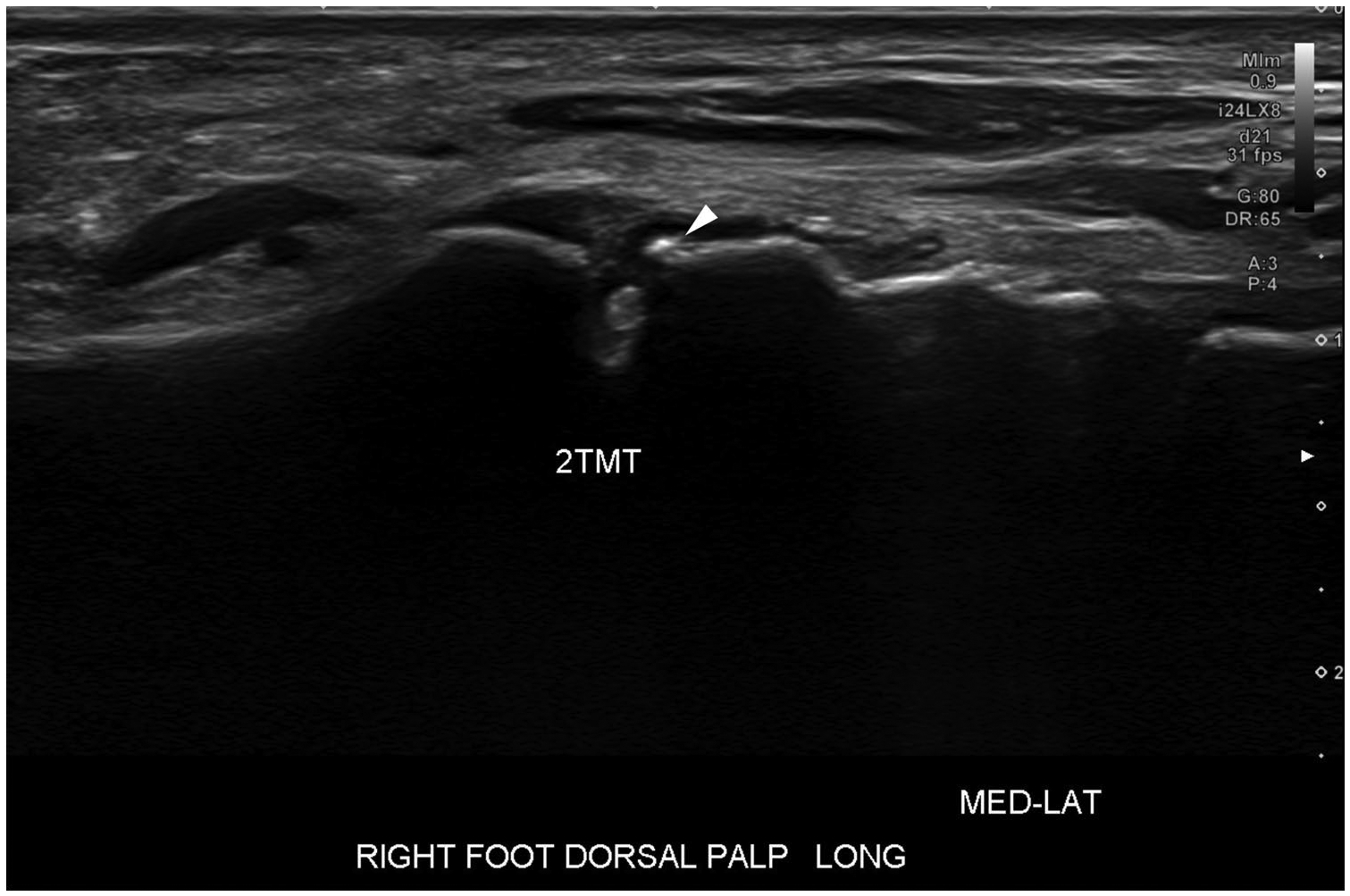

Fig. 8.

A 32-year-old male patient presented with persistent right lateral ankle pain after an inversion injury while playing basketball 6 months prior. Initial radiographs showed only mild soft tissue swelling over the lateral malleolus (not shown). Microvascular ultrasound (US) Doppler image of the ATFL shows fusiform thickening of the mid-substance of the ligament with extensive intra-ligamentous and periligamentous vascularity, indicating hyperemia and attempted healing

Although US is less helpful to directly characterize intra-articular abnormalities, such as chondral loss and subchondral bone pathology, it can identify synovial proliferation and active synovitis on Doppler imaging, which can be present in OA or inflammatory arthropathies. In OA, areas of synovial hyperemia on Doppler imaging are often more symptomatic. Additionally, US can be used to detect juxta-articular erosions and communicating cyst-like changes. The degree and distribution of synovitis along with the presence of juxta-articular erosions can help distinguish OA from inflammatory arthropathies [23]. Some authors have reported that US is more sensitive in detecting early signs of OA, including the development of marginal osteophytes in some of the small joints in the hindfoot and midfoot than radiography (Fig. 9) [24]. While US is not as sensitive as MRI in detecting erosions and subchondral cyst-like changes, it is probably similar to MRI in its ability to detect and characterize the degree of synovitis. US shear wave elastography is an emerging technique that enables the assessment of the intrinsic tissue properties with potential added value in the evaluation of the ankle and foot tendons and ligaments [25, 26].

Fig. 9.

A 58-year-old female patient presents with focal right dorsal midfoot pain, stiffness, and swelling over the second tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. Radiographs of the foot did not show an explanation for the patient’s symptoms. Long-axis greyscale US image of the second TMT joint shows a very small dorsal middle cuneiform marginal osteophyte that could not be visualized radiographically (arrowhead). Color Doppler imaging of the same joint did not show synovial hyperemia (not shown), suggesting this represented bland synovial proliferation

Bone scintigraphy is very sensitive in detecting areas of increased bone turnover. As a result, it can be used to distinguish more symptomatic areas of OA from quiescent areas, which can help target treatment. However, bone scintigraphy is not specific for any pathology, and the diagnosis of symptomatic OA should occur in context with other imaging. Additionally, scintigraphy has a poor spatial resolution, which may make it difficult to localize areas of increased radiotracer uptake. Newer CT techniques, such as single photon emission CT (SPECT) and SPECT/CT fusion techniques, have been used to better assign areas of increased radiotracer uptake to specific anatomic structures (Fig. 10) [27]. As high-resolution MRI scanners have become more available, bone scintigraphy is used less often to detect and characterize ankle and foot OA. Areas of BME on fat-saturated, fluid-sensitive MRI sequences often correspond to areas of increased radiotracer uptake on scintigraphic studies, allowing MRI to more easily localize abnormalities and improve diagnostic specificity.

Fig. 10.

A 64-year-old female with BMI of 39 kg/m2 had chronic bilateral dorsal midfoot pain, left greater than right. The patient does not recall prior trauma. a DP radiograph of the left foot demonstrates multifocal areas of midfoot osteoarthritis, most pronounced at the second and third tarsometatarsal joints and the medial naviculocuneiform joint (arrowheads). b AP delayed image from a 3-phase Tc-99 m-MDP bone scintigraphy of both feet show bilateral midfoot radiotracer uptake primarily involving the middle column, left greater than right (arrowheads). There is a much less radiotracer uptake on the left at the naviculocuneiform joint (arrow), suggesting that it may be less active. c Sagittal T1W NFS MR image of the left hindfoot shows typical findings of midfoot osteoarthritis involving the dorsal second tarsometatarsal joint, with marginal osteophytes and subchondral marrow replacement (white arrowhead), consistent with radiographic sclerosis. The Lisfranc ligament complex appeared intact (not shown). Note small foci of subchondral bone marrow signal alteration at the talar dome and tibial plafond with a small posterior osteophyte (long black arrows) consistent with early OA, superimposed on a remote healed posterior malleolus fracture (short black arrow)

Specific Joints

Ankle

The ankle joint articular surfaces are generally congruent, conferring great stability that primarily allows motion from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion, with lesser degrees of inversion/eversion, and internal/external rotation. The ankle and hindfoot are bounded by a number of static and dynamic stabilizers [3].

Medially, the fan-shaped deltoid ligament is divided into superficial and deep layers and resists lateral talar and calcaneal translation and valgus angulation. Components of the deep deltoid ligament join with the plantar calcaneonavicular (spring) ligament and are static stabilizers of the midfoot arch, preventing excessive talar head plantar flexion (Fig. 11a). The posterior tibialis tendon (PTT) is an important dynamic stabilizer of the medial midfoot (Fig. 11b) [28].

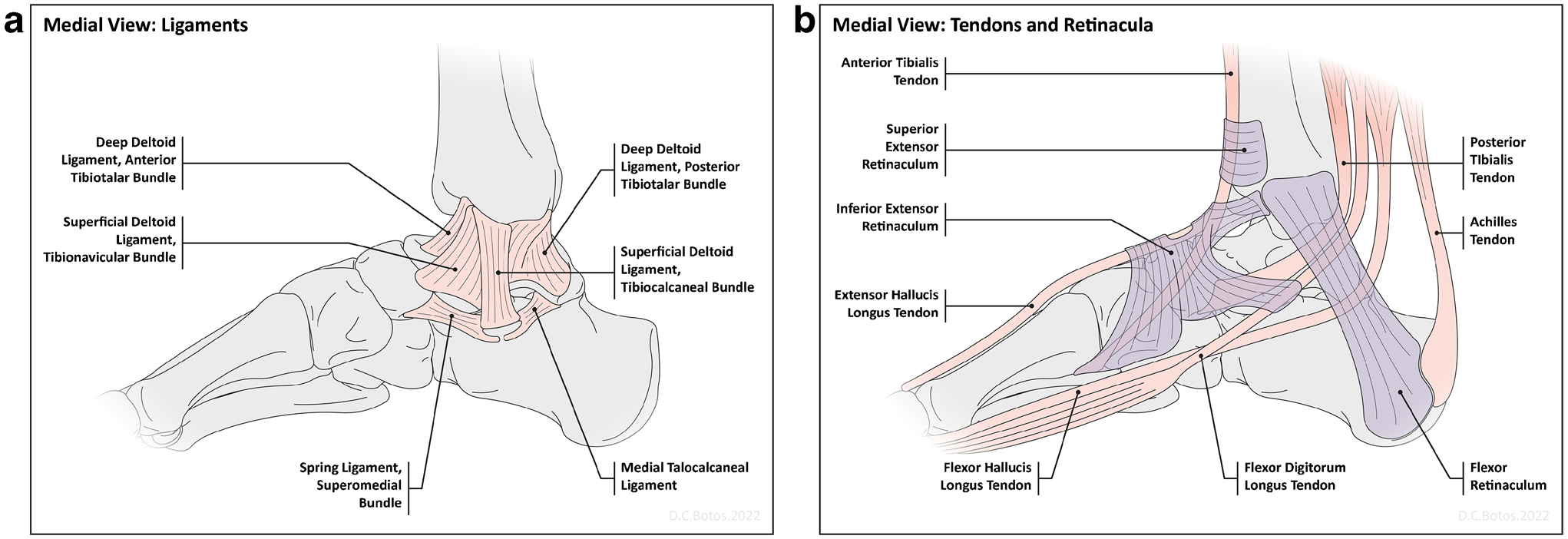

Fig. 11.

Diagrams of the major medial static and dynamic ankle stabilizers. a A diagram of the medial ligaments of the ankle and hindfoot shows the relationships of the major ligaments. The superficial bundle of the deltoid ligament fans out from the medial malleolus and has a number of components. For clarity, only the tibionavicular and the tibiocalcaneal components are shown here. The deep deltoid ligament is primarily composed of the anterior and posterior tibiotalar bundles, as shown. The calcaneonavicular, or spring ligament has three components, the superomedial, medioplantar oblique and inferoplantar lateral bundles. Only its most medial and strongest component, the superomedial bundle, is shown here. b A diagram of the medial ankle tendons shows the relationship between the three flexor tendons, which course posterior to the medial malleolus. The posterior tibialis tendon is a major ankle stabilizer and primarily inserts on the navicular tuberosity. The flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus tendons cross over one another in the plantar hindfoot, often called the master knot of Henry

Laterally, the ankle and hindfoot are stabilized by the ATFL, posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (Fig. 12a). The ATFL primarily resists anterior translation and varus angulation in plantarflexion, while the CFL bridges the ankle and subtalar joints, preventing ankle adduction and talar varus angulation especially when the ankle is dorsiflexed. The PTFL is very strong and rarely injured. These ligaments are supported by the peroneal muscles and tendons, which are important lateral dynamic stabilizers and antagonists of the PTT (Fig. 12b) [29].

Fig. 12.

Diagrams of the major lateral static and dynamic ankle stabilizers. a A diagram of the lateral ligaments of the ankle and hindfoot shows the relationships of the major ligaments. The three most commonly injured ligaments are the anterior talofibular ligament, the calcaneofibular ligament and the anterior tibiofibular, or syndesmotic ligament. The anterior talofibular ligament may be composed of 1–3 separate bundles. b A diagram of the lateral ankle tendons shows the relationship between the peroneal tendons, which course posterior to the lateral malleolus and are stabilized by superior and inferior peroneal retinacula. The peroneus brevis is a major antagonist to the posterior tibialis tendon and inserts on the fifth metatarsal tuberosity, while the peroneus longus courses around the lateral and plantar surface of the cuboid and has several insertions in the plantar medial midfoot with the majority of fibers inserting on the medial cuneiform and first metatarsal base

Ankle OA can be related to a single injury or repeated injuries resulting in instability. Given the high association with prior trauma, ankle OA becomes symptomatic 5–10 years earlier than hip or knee OA on average [30, 31]. Two main patterns of ankle instability, varus and valgus instability, are often associated with recognizable imaging findings [32].

Varus instability predominates. It results from inversion injury and affects the lateral stabilizers. It can be associated with attenuation of the ATFL and CFL, and cervical ligament of the subtalar joint, along with contracture of the deltoid ligament [7, 29]. Varus instability places great stress on the peroneal tendons, leading to muscular weakness and tendon insufficiency [33, 34]. These factors contribute to medial talar translation, internal rotation, and varus talar tilting, which shifts the mechanical axis of the talar dome and causes accelerated chondral loss, OCLs, often along the medial talar dome, and OA [7].

Initial radiographic assessment includes AP, mortise, and lateral weight-bearing radiographs of the ankle centered on the tibiotalar joint or talar body [35]. On an AP weight-bearing ankle radiograph, there are several reported measurements that can be useful to detect instability prior to the development of symptomatic OA. Several of the most common measurements and their normal values are reviewed in Fig. 13 [7, 36].

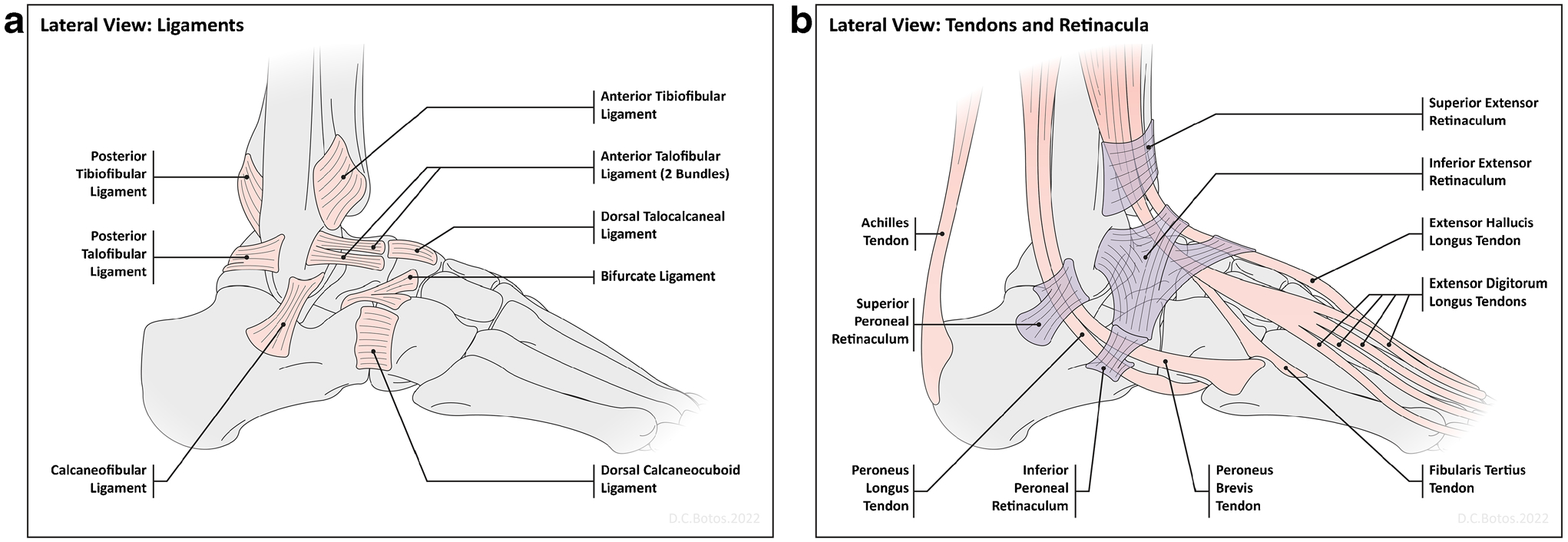

Fig. 13.

Normal radiographic measurements of the distal tibia and tibiotalar osteoarticular relationships. a On an AP weightbearing radiograph of the right ankle, the tibial anterior surface (TAS) angle (dashed curve), formed by the mechanical axis of the tibia (solid vertical line) and the tangent of the tibial plafond (dashed line), normally measures 93° + / − 3°. A varus tilt is diagnosed if the tibial anterior surface angle measures less than 90°. The tibiotalar surface (TTS) angle (solid curve), formed by the mechanical axis of the tibia (solid vertical line) and tangent to the talar dome (solid horizontal line), normally measures 87.2° + / − 2.8°, and a TTS angle of less than 84.4° is considered abnormal. Finally, the talar tilt (TT) or tibiotalar angle (dotted curve) is formed by taking tangents of the talar dome (solid horizontal line) and tibial plafond (dashed horizontal line). Normally, these surfaces should be parallel, and the tibiotalar angle should measure no greater than 2°. b On the lateral weightbearing radiograph of the ankle, the tibial lateral surface angle, which is formed by the mechanical axis of the tibia and a line connecting the anterior and posterior margins of the talar dome should measure 83° + / − 3.6°

Once OA has developed, typical radiographic findings include cartilage loss leading to JSN, subchondral cyst-like changes and sclerosis, and marginal osteophytes (Fig. 14) [37]. Ultimately, anterior tibiotalar osteophytes can result in anterior synovitis and ankle impingement, which limits dorsiflexion and leads to progressive dysfunction [29]. Holzer et al. reported a modified Kellgren-Lawrence scoring system for general ankle OA that correlates well with clinical symptoms [Table 1] [38]. However, varus instability shifts the biomechanical load of the tibiotalar joint medially. Takakura et al. reported a medial-predominant OA-specific staging system associated with this instability pattern [Table 2] [39].

Fig. 14.

A 62-year-old male patient presented with history of repeated severe right ankle sprains and medial greater than lateral ankle pain. Coronal reformatted image from a weight-bearing CBCT shows advanced medial tibiotalar osteoarthritis (short arrow). There is varus angulation of the talus with medial malleolar osseous remodeling. The contact point has shifted to the medial talar body. Corticated ossifications distal to the medial and lateral malleoli are consistent with prior fractures (long arrow). There is a developing pseudarthrosis between the lateral talar process and calcaneal sulcus (arrowhead)

Table 1.

Holzer modified Kellgren-Lawrence scale for ankle osteoarthritis

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Osteophytes of doubtful meaning on the medial or lateral malleolus, rare tibial sclerosis, joint space width unimpaired |

| 2 | Definite osteophytes on the medial malleolus, joint space width unimpaired |

| 3 | Definite osteophytes on the medial and/or lateral malleolus, moderate (< 50%) joint space width narrowing |

| 3a | Talar tilt < 2° |

| 3b | Talar tilt > 2° |

| 4 | Definite osteophytes on medial and lateral malleoli as well as tibiotalar joint margins, severe (> 50%) to complete joint space narrowing, constant tibiotalar sclerosis |

Table 2.

Takakura staging system for medial ankle osteoarthritis

| Stage | Radiographic osteoarthritis signs |

|---|---|

| 1 | No joint space narrowing, but early sclerosis and osteophyte formation |

| 2 | Narrowing of the joint space medially |

| 3 | Obliteration of the joint space with subchondral bone contact medially |

| 4 | Obliteration of the whole joint space with complete bone contact |

Advanced imaging techniques, such as weight-bearing CBCT are used to supplement radiographs by improving visualization of articular surfaces, OCLs, and osseous malalignment [16]. MRI can assess early findings of OA, including subchondral BME and chondral loss, and is the modality of choice to identify and characterize radiographically-occult OCLs (Fig. 15) [40]. Griffith et al. reported an MRI grading system for OCLs that accounts for findings such as chondral fracture, osteochondral separation, and subchondral collapse, which helps determine OCL stability and guide therapeutic decision-making [Table 3] [18]. Moreover, MRI can detect lateral ligamentous complex attrition and peroneal tendinopathy in the setting of varus instability [9]. Surgical stabilization and treatment of OCLs are indicated in patients with symptomatic ankle instability in the setting of medial talar OCLs or tibiotalar subchondral BME to minimize the risk of end-stage OA.

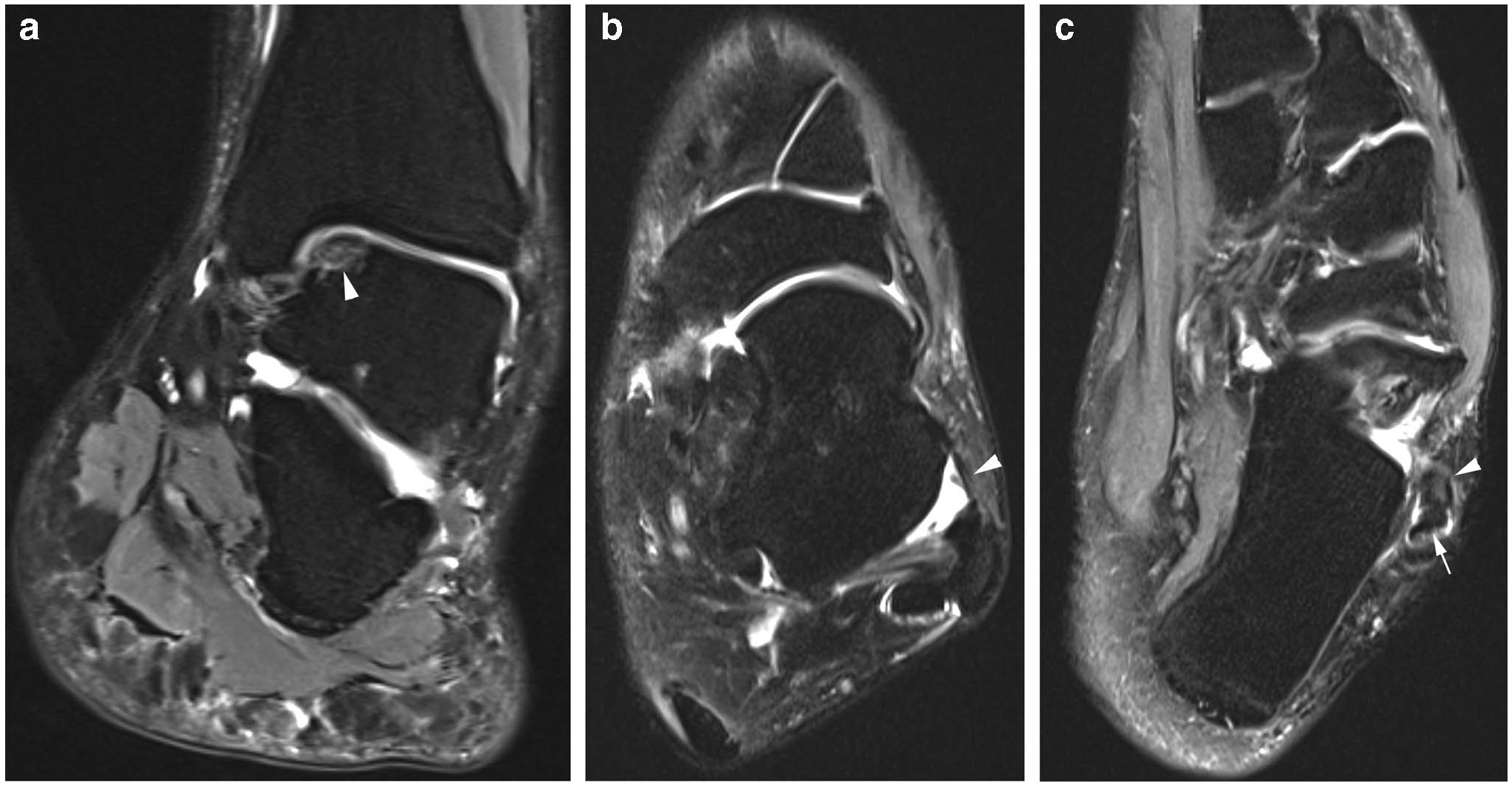

Fig. 15.

A 26-year-old female patient with recurrent left ankle sprains and instability presenting with medial ankle pain and sensation of lateral instability underwent an MRI. a Coronal T2W FS MR image of the hindfoot shows a radiographically occult medial talar dome osteochondral injury with an in situ fragment (arrowhead). The fragment is mildly edematous and there is chondral fissuring at the osteochondral margin. Although there is suggestion of varus angulation of the calcaneus, this study is not performed with weight-bearing and varus angulation should be confirmed with weightbearing radiography or CBCT. b Axial T2W FS MR image of the ankle shows moderate thinning of the ATFL, consistent with attrition (arrowhead). c A slightly more inferior axial T2W FS MR image shows mild peroneus brevis tendon thickening and intermediate signal (arrowhead), consistent with severe tendinopathy. The peroneus longus tendon is slightly irregular as well (arrow), suggesting tendinopathy. Varus hindfoot alignment may place greater stress on the peroneal tendons, resulting in tendinopathy and tenosynovitis. Hindfoot alignment views are very useful in this setting and should be performed to guide the surgeon in performing the appropriate bony correction in addition to the ligament/tendon/cartilage reconstruction

Table 3.

Griffith MRI classification of talar dome osteochondral lesions

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1a | Bone marrow change (edema, cystic change) with no collapse of subchondral bone area, no osteochondral junction separation and intact cartilage |

| 1b | Similar to grade 1a though with cartilage fracture |

| 2a | Variable collapse of subchondral bone area with osteochondral separation though intact cartilage |

| 2b | Similar to grade 2a though with cartilage fracture. This is an unstable lesion with level of instability related to extent of cartilage fracture |

| 3a | Variable collapse of subchondral bone area with no osteochondral separation + / − variable cartilage hypertrophy |

| 3b | Similar to grade 3a though with cartilage fracture |

| 4a | Separation within or at edge of bone component with intact overlying cartilage |

| 4b | Similar to grade 4a though with cartilage fracture. This is an unstable lesion with level of instability related to extent of cartilage fracture |

| 5 | Complete detachment of osteochondral lesion. This is an unstable lesion |

The second major type of instability is valgus instability with medial ligamentous complex insufficiency. This is less common than varus instability, since eversion injuries producing medial ligament sprains are less frequent, and isolated deltoid ligament injuries represent only 3–4% of all ankle sprains. With spring ligament failure, there is an increased load on the PTT, leading to progressive tendinopathy and subsequent failure. Insufficiency of the ligaments and PTT can result in instability and articular cartilage wear [28, 32]. Radiographically, there is talar valgus angulation that can be seen on weight-bearing AP radiographs of the ankle, with a talar tilt angle of greater than 2° [36]. This shifts the tibiotalar contact area laterally to a narrower region, leading to accelerated cartilage loss, talar dome OCLs, and subsequent tibiotalar OA (Fig. 16) [28].

Fig. 16.

A 67-year-old female patient with history of prior ankle fracture status post-surgical fixation. The patient has had medial and lateral ankle pain and decreased range of motion and underwent weight-bearing CBCT. Coronal reformatted CBCT image of the ankle seen in bone window shows the lateral shifting of the tibiotalar contact (arrowhead), with focal bone-on-bone apposition and subchondral cyst-like changes. The talar tilt angle measures 4°

With the progressive failure of the medial static and dynamic stabilizers, there may be associated calcaneal valgus angulation, with a talocalcaneal angle of more than 40° on dorsoplantar (DP) weight-bearing foot radiographs. Normally, this angle measures between 25 and 40°. Additional findings of hindfoot valgus and loss of the medial midfoot arch on weight-bearing radiographs include the following: a decreased calcaneal inclination angle (< 18°); excessive talar head plantar flexion, with an increasing talar-metatarsal (Meary) angle on lateral weight-bearing radiographs (> 4°); and excessive forefoot abduction on AP radiograph of the foot with at least 30% uncoverage of the medial talar articular surface at the talonavicular joint (Fig. 17) [41, 42].

Fig. 17.

A 33-year-old male patient presents with left medial midfoot arch collapse, progressive ankle and foot pain, and decreased range of motion. a CBCT weight-bearing coronal reformatted image of the ankle seen in bone window shows findings of valgus instability with valgus angulation of the talus and lateral predominant joint space narrowing and OA (arrowhead). Additionally, on a lateral weight-bearing radiograph of the foot, b there are findings of medial midfoot arch collapse, including excess talar head plantar flexion with a talar-metatarsal angle measuring 35° (measured angle), pes planus, with a calcaneal inclination angle measuring 0°. On a DP weight-bearing radiograph of the foot, there is forefoot abduction with excessive medial talar head uncoverage (not shown). c On an axial PDW NFS MR image of the hindfoot, there is a thickened, ill-defined deep deltoid ligament (arrow) and the posterior tibialis tendon (PTT) is thinned and frayed (arrowhead), related to either partial tendon tear or attritional tendinosis. Valgus instability and medial midfoot arch collapse often places greater stress on the PTT, which can result in tendon degeneration

MRI can detect abnormalities of the medial soft tissue supporting structures suggesting valgus instability, prior to the development of OA. Injury to the superficial deltoid ligament usually occurs at the tibio-periosteal junction, and MRI may show surrounding soft tissue or BME, partial ligamentous detachment or delamination, or complete ligament tearing. In chronic injury, the ligament often appears thickened at its tibial attachment with associated traction bone spurs. Injury of the deep deltoid ligament usually involves its mid-substance and is associated with loss of the normal striated appearance [43]. There may be flexor tenosynovitis, or an abnormal caliber of the PTT, with tendon thinning representing attritional tendinosis or partial tearing (Fig. 17) [44]. Hindfoot correction with bony and soft tissue correction would be considered aggressively in the setting of early deltoid ligament tearing to prevent late ankle valgus deformity and rapid ankle OA.

Surgical treatments of ankle OA are divided into joint-preserving and joint-sacrificing techniques. Joint preserving surgeries include osteochondral resurfacing, distraction arthroplasty, arthroscopic debridement, and periarticular corrective osteotomies. Joint sacrificing surgeries include total ankle arthroplasty and arthrodesis [8], the details of which are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Subtalar joint

The hindfoot consists of the subtalar and the midtarsal joints. The subtalar joint is primarily composed of the talocalcaneal joint and can be divided into anterior and posterior segments. The anterior component involves the talar head articulation with the anterior and middle facets of the calcaneus, and the spring ligament. The posterior component involves the articulation of the posterior calcaneal facet and the posterolateral inferior talar facet [45].

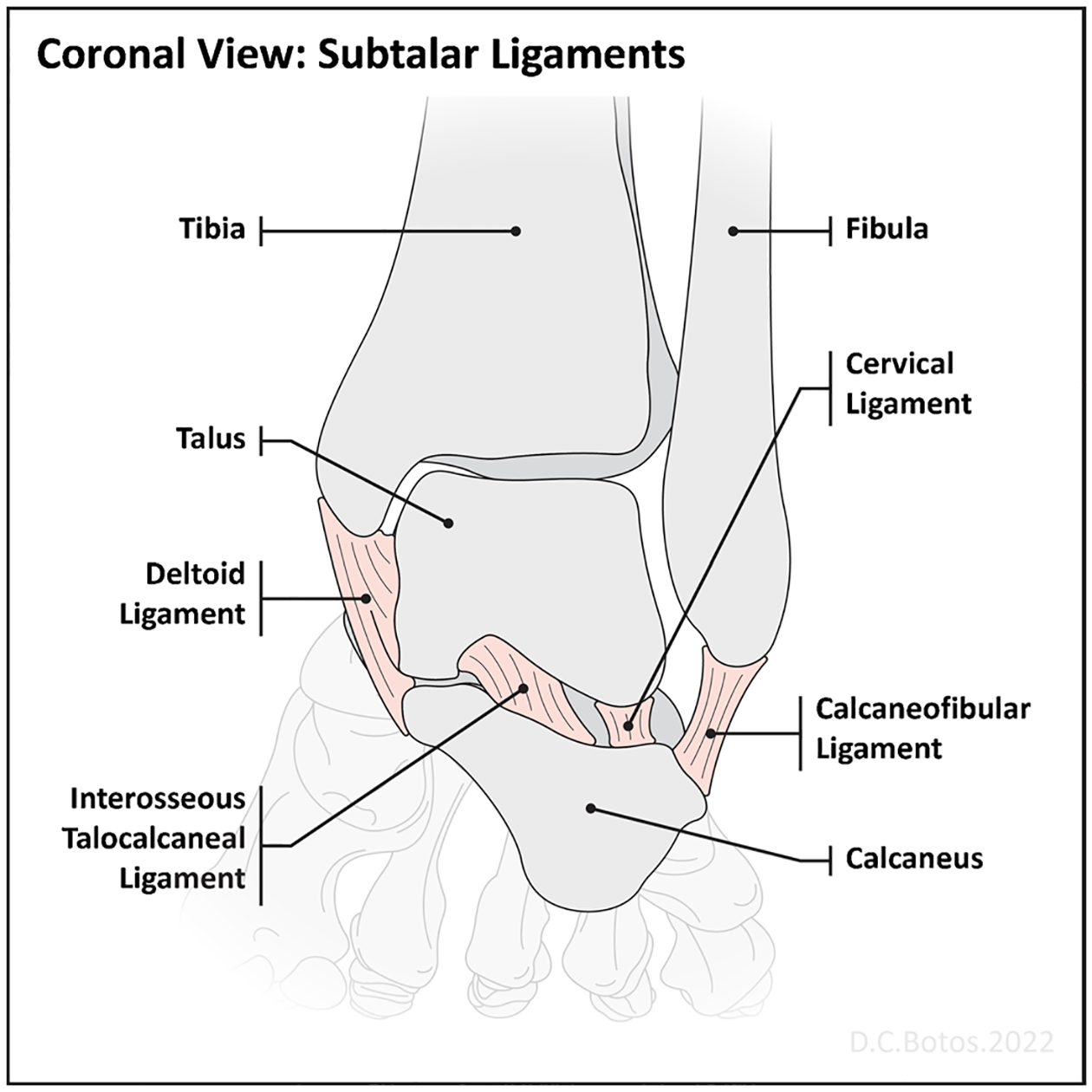

The subtalar joint is primarily supported by the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament (ITCL), the cervical ligament, and the roots of the extensor retinaculum (Fig. 18). The ITCL is the primary static stabilizer of the subtalar joint and is located most medially within the sinus tarsi and calcaneal sulcus. The fascicles of the inferior extensor retinaculum are often seen extending into the lateral sinus tarsi. While their role in stabilizing the subtalar joint is less well established, they may help resist ankle inversion and eversion [46].

Fig. 18.

A coronal diagram of the subtalar joint shows the relationship of the major ligaments from medial to lateral. The interosseous talocalcaneal ligament is the strongest ligament and located more medially, deep to the deltoid ligament, while the cervical ligament and the extensor retinacular roots (not shown) are more lateral and deep to the calcaneofibular ligament

Subtalar OA is most commonly posttraumatic and may be due to acute talar or calcaneal fractures, often with subtalar dislocations or instability [47]. Other etiologies, such as OA following RA, should be considered in the absence of prior trauma [48]. Subtalar OA due to instability is commonly associated with tibiotalar OA [49]. Patients may have a history of acute inversion injury or several repetitive injuries that lead to a sensation of instability, pain, stiffness, and swelling, which are worse with athletic participation and when walking on uneven ground. The cervical ligament may be injured along with the lateral ankle ligamentous complex during inversion injuries. The ITCL may require greater force before it becomes insufficient [50].

Initial imaging includes AP, lateral, and mortise weight-bearing radiographs of the ankle as well as a hindfoot alignment view. Early/mild instability may be difficult to detect on these projections, and the Brodén view in which the ankle is maximally dorsiflexed and supinated to stress the subtalar joint may help detect subtle instability (Fig. 19) [51]. Instability on this view can be diagnosed with excessive subtalar tilt or greater than 7 mm of posterior joint diastasis [46]. Weight-bearing CBCT can also detect mild osseous malalignment, while MRI can assess the integrity of the ITCL and cervical ligament and the status of the articular cartilage (Fig. 20) [52, 53]. Impingement of the lateral talar process and the angle of Gissane in severe flatfoot deformity presenting with BME at both bony surfaces should not be confused with subtalar OA if the remaining posterior facet is normal.

Fig. 19.

A 51-year-old female patient had ORIF for a depressed intra-articular calcaneal fracture after falling from a roof. Brodén view performed following surgery shows fracture extension to the posterior calcaneal facet with articular surface step-off (arrowhead) and diastasis medially. The lateral radiograph of the ankle (not shown) could not adequately depict this appearance due to overlapping osseous structures

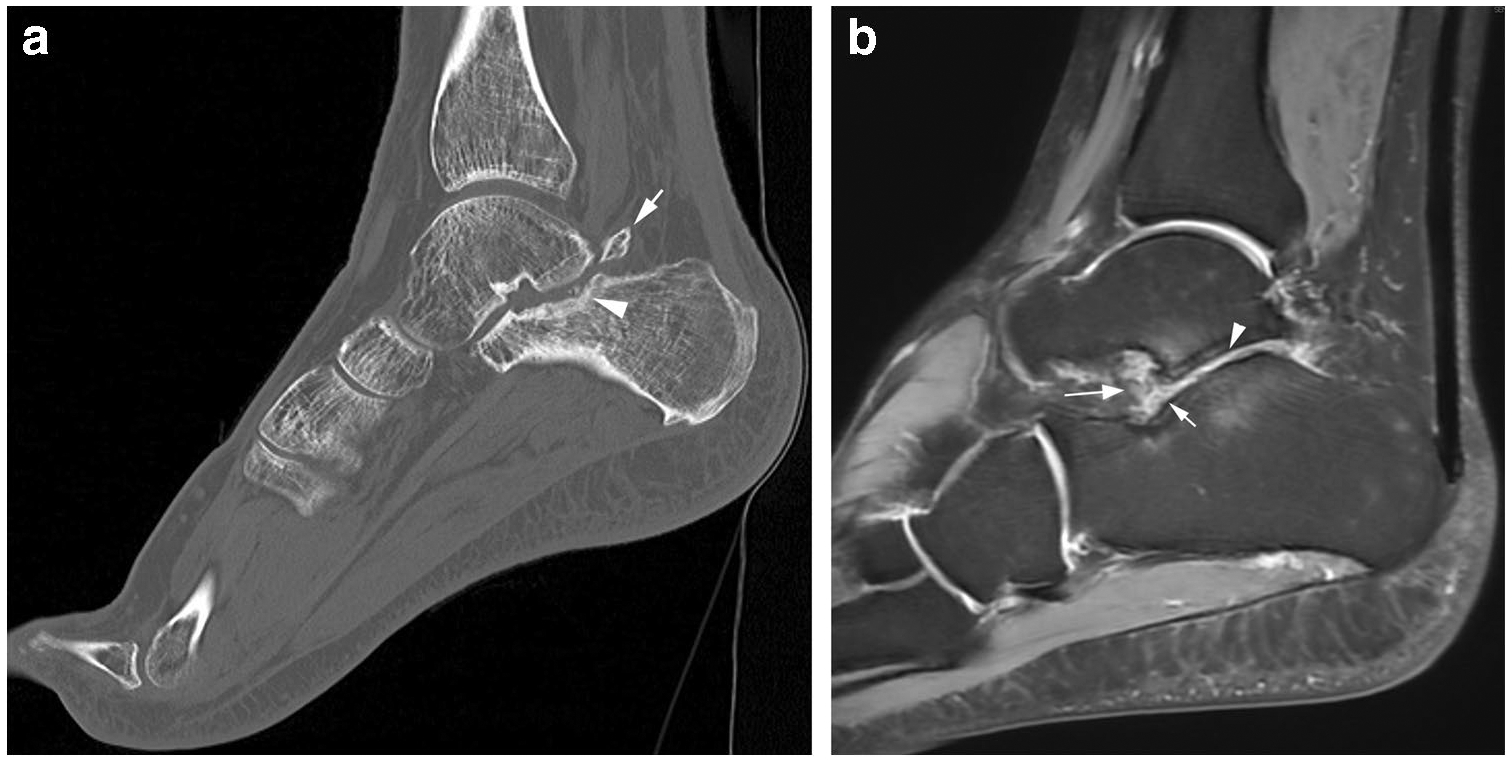

Fig. 20.

A 41-year-old male patient had a right ankle twisting injury with pain and swelling. The patient was initially diagnosed with a lateral ligamentous complex injury but the symptoms in the hindfoot persisted. Preliminary lateral radiograph of the foot (not shown) demonstrated a small posterior subtalar joint intraarticular body, indicating chondral loss, with the joint not well seen. a Sagittal CT reformatted image of the posterior subtalar joint shows posterior calcaneal facet subchondral plate irregularity with two punctate intra-articular ossific fragments (arrowhead) in addition to the larger posterior joint recess intra-articular body (arrow). b Sagittal PDW FS MR image of the hindfoot reveals posterior subtalar osteoarthritis, with reciprocal subchondral BME, hyaline cartilage loss (arrowhead), and mild synovitis (shorter arrow). Additionally, the cervical ligament is ill-defined and edematous, and partially torn (longer arrow)

Surgical treatment of isolated subtalar instability focuses on stabilizing the lateral ligamentous complex, which may involve direct ligamentous repair along with tendon graft augmentation or even reconstruction, when necessary, and correction of any contributing osseous abnormalities. However, isolated subtalar OA failing conservative management often requires subtalar arthrodesis [49].

Midtarsal (Chopart’s) joint

The midtarsal joint is composed of 2 separate articulations, the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. The talonavicular joint is stabilized by the dorsal talonavicular ligament and the calcaneonavicular component of the bifurcate ligament arising from the anterior process of the calcaneus. The calcaneocuboid articulation is supported by the dorsal calcaneocuboid ligament, the short and long plantar foot ligaments, and the calcaneocuboid component of the bifurcate ligament. The calcaneocuboid articulation is further supported by the plantar components of the spring ligament [54].

Midtarsal joint OA is usually posttraumatic, often occurring with athletic participation. It may occur following high-energy midtarsal fracture-dislocations or lower-energy sprains. Injuries at this joint may be initially overlooked, particularly in the setting of additional ankle injuries, and failure to adequately treat these injuries can result in chronic instability and pain. Midtarsal joint injuries are most commonly associated with ankle inversion and plantar flexion resulting in dorsal and lateral distraction of the bifurcate, dorsal talonavicular, and dorsal calcaneonavicular ligaments; and possibly osseous avulsions, especially involving the anterior calcaneal process [55, 56].

Alternatively, ankle eversion can lead to plantar/medial ligament injuries, including the inferoplantar lateral component of the spring ligament, which can be associated with a navicular tuberosity fracture, and short and long plantar ligament injuries. This can be associated with the traction of the PTT and compression of the calcaneocuboid joint [57].

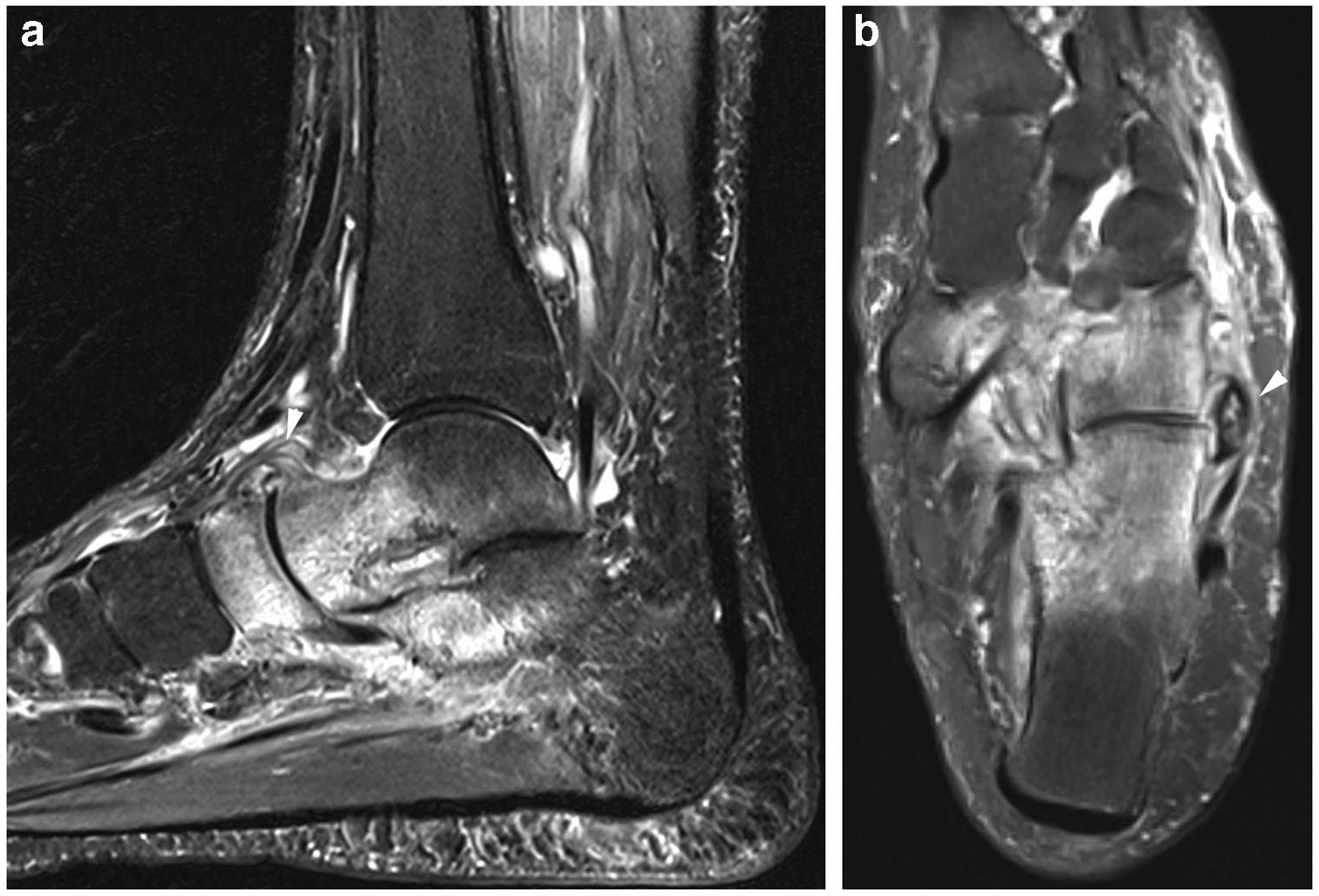

Imaging starts with radiography to assess the degree and distribution of OA. This includes DP, lateral, and internally-rotated oblique radiographs of the foot with weight-bearing to look for avulsion fractures of the dorsal talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints as well as the anterior calcaneal process. The internally-rotated oblique view best depicts osteochondral injuries, JSN, and osteophytes at the calcaneocuboid joint. AP varus stress radiography may reveal an enlarged calcaneocuboid angle (< 10°), indicating instability [54]. MRI can directly detect cartilage loss, subchondral BME, and subchondral cyst-like changes; and the status of the bifurcate, dorsal talonavicular, and dorsal calcaneocuboid ligaments (Fig. 21) [58].

Fig. 21.

A 44-year-old female patient had a fracture of the left ankle anterior calcaneal process radiographically and underwent subsequent MRI to assess for midtarsal joint injury. a A sagittal STIR MR image of the hindfoot demonstrates a pronounced post-traumatic arthropathy of the midtarsal joint, including intense BME of the talar head, navicular, and anterior calcaneal process. There is partial tearing of the dorsal talonavicular ligament (arrowhead), which appears edematous. b Axial T2W FS MR image of the hindfoot demonstrates significant thickening and periligamentous edema around the lateral calcaneocuboid joint capsule (arrowhead), which appears partially detached from the cuboid base and could contribute to calcaneocuboid instability

Triple arthrodesis is much more commonly performed than isolated talonavicular or calcaneocuboid arthrodesis to treat symptomatic midtarsal OA. Although arthrodesis is often successful, it can lead to OA in neighboring joints [59].

Midfoot

The midfoot is composed of the tarsometatarsal (TMT), or Lisfranc, joints, the intercuneiform, cubocuneiform, and naviculocuneiform joints [60]. The TMT joints are often divided into 3 functional columns, the medial column, consisting of the first TMT joint; the middle column, composed of the second and third TMT joints; and the lateral column, which consists of the fourth and fifth TMT joints. The TMT joints, particularly the medial and middle columns, are greatly stabilized by the osteoarticular morphology and numerous ligaments. The most well-developed of these is the Lisfranc ligament complex, which is a strong stabilizer between the first and second TMT joints [61, 62].

Midfoot OA can be idiopathic, posttraumatic following Lisfranc fracture/dislocation, secondary to inflammatory or metabolic arthropathies such as RA or gout, or neuropathic arthropathy, or follow hindfoot fusion with the transfer of stress to the midfoot joints [60]. Patients with midfoot OA present with chronic pain in the dorsal midfoot, and progressive deformity leading to loss of balance and increased risk of falling. There is a greater incidence with aging and in people with higher body mass index, which may be more often associated with pes planus, resulting in generally greater loading along the dorsum of the midfoot joints. Additionally, the middle column is the most rigid, which likely contributes to the higher rate of OA at the second and third TMT joints, while the lateral column is relatively flexible, particularly during the toe-off phase of gait, which may also protect the fourth and fifth TMT joints from OA [63]. Finally, some patients may develop a midfoot break, which is a hypermobile midfoot segment that often arises with decreased hindfoot mobility [64].

Imaging includes weight-bearing DP, lateral, and oblique radiographs, and possibly a non-weight-bearing lateral radiograph to determine whether there is a midfoot break at the TMT, naviculocuneiform, or talonavicular levels [60]. A midfoot-specific radiographic grading system has been developed to assess the degree and distribution of OA [Table 4] [65]. Weight-bearing CBCT in a small patient population has been shown to improve the detection of OA findings, and CT can be helpful to characterize posttraumatic deformities or fracture fragments (Fig. 22) [66]. MRI can also help to determine the degree and location of OA but is more useful in assessing the status of supporting structures, like the Lisfranc ligament complex [62]. The accurate denotation of subchondral BME and subchondral cysts can help guide the surgeon to determine which joints require arthrodesis.

Table 4.

Menz radiographic classification of osteoarthritis in the foot

| Osteophytes (0–3) | None (0) |

| Small (1) | |

| Moderate (2) | |

| Large (3) | |

| JSN (0–3) | None (0) |

| Definite (1) | |

| Severe (2) | |

| Joint fusion (3) |

• JSN, joint space narrowing

• Assessment performed on DP and lateral radiographs of 1st MTP, 1st TMT, 2nd TMT, naviculocuneiform joint and TNJ, the 5 most common joints for OA in the foot

• Score of 2 or more on either projection is considered significant OA for that joint

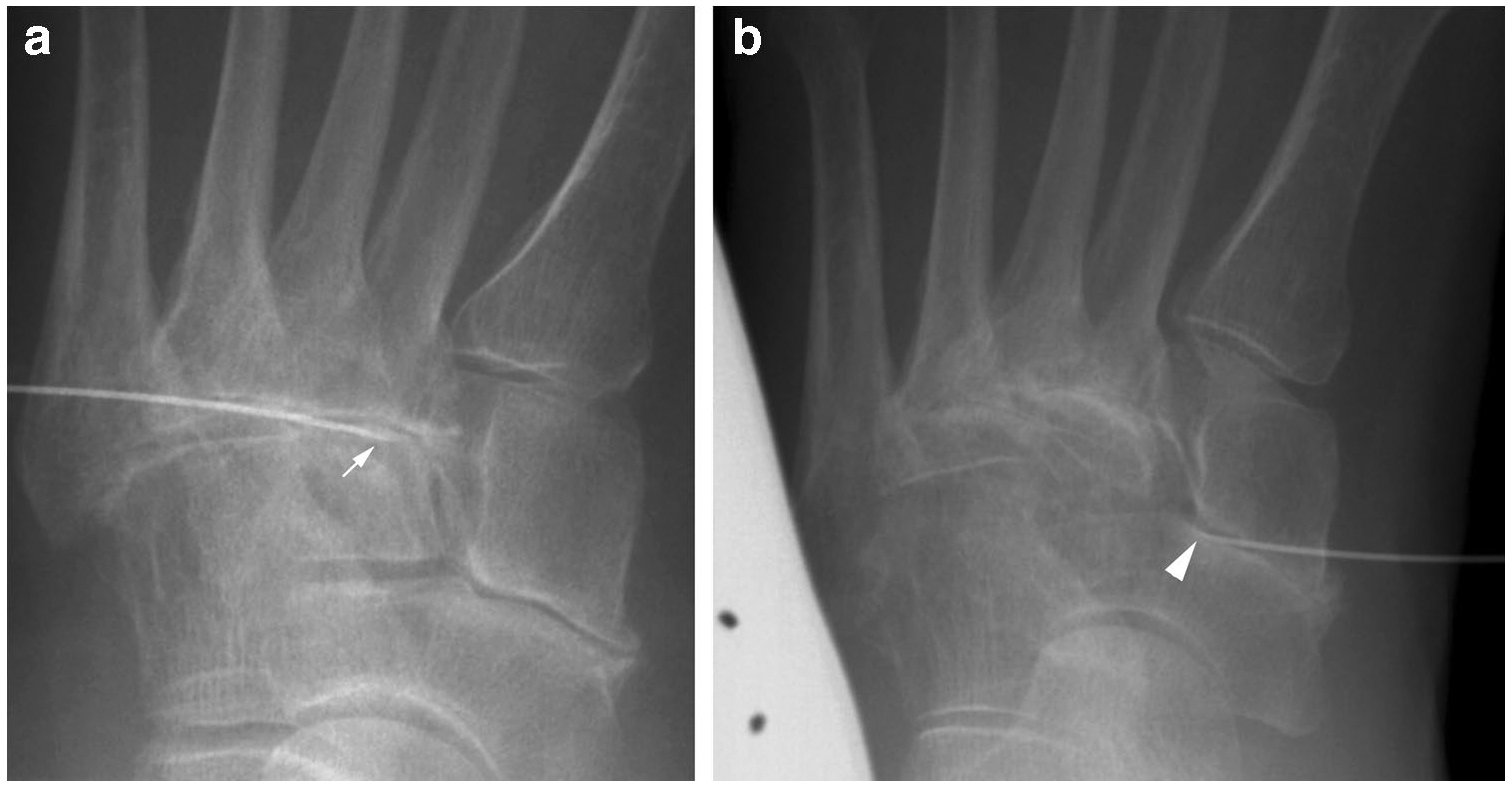

Fig. 22.

A 46-year-old male patient had a right midfoot injury with subsequent OA at the Lisfranc joint. Radiography of the foot shows first and second TMT OA (not shown). a A sagittal reformatted weightbearing CBCT image of the second ray shows moderate OA of the second TMT joint (arrowhead). b Subsequent weightbearing CBCT of the midfoot was performed after ORIF of the first and second TMT joints. An axial reformatted image through the midfoot along the metatarsal axes revealed ankylosis of the second TMT joint. However, there is additional moderate third TMT OA (arrowhead), corresponding to patient’s pain that localized to this joint following surgery

In the setting of polyarticular midfoot OA, there may be confusion clinically about whether a particular joint is a pain generator. In these cases, bone scintigraphy utilizing SPECT or SPECT/CT may be helpful to identify areas of active radiotracer uptake, which more likely correspond to pain generators [67]. Some institutions use fluoroscopically-guided TMT injections with a local anesthetic to determine whether a particular joint is a pain generator (Fig. 23). However, the TMT joints may communicate with one another, limiting the usefulness of this technique [68].

Fig. 23.

A 66-year-old female patient had chronic midfoot pain and OA primarily at the second TMT and navicular-medial cuneiform joints (NCJ). The treating physician was not sure whether either joint or both joints were pain generators and performed targeted injections at each joint a week apart. a DP fluoroscopic image of the midfoot shows the tip of a 20-gauge needle (arrow) located over the second TMT joint using a dorsal approach. b A subsequent DP fluoroscopic image of the midfoot demonstrates the tip of a 20-gauge needle (arrowhead) located over the NCJ. The patient received substantial relief with injection over the second TMT joint but only mild relief with injection into the NCJ, suggesting the TMT was the main pain generator

Surgical treatment commonly involves arthrodesis of the medial and middle columns when the patient has failed conservative management. Symptomatic lateral column OA is difficult to treat due to this joint’s mobility, and arthrodesis can lead to nonunion or stress injuries. Some institutions have performed interposition arthroplasty rather than arthrodesis [60].

OA associated with pre-existing congenital or acquired conditions

Pes cavovarus, or elevation of the longitudinal arch of the foot, may be idiopathic, due to hindfoot trauma or neuromuscular conditions, such as cerebral palsy or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. If this condition is untreated, it may result in valgus ankle instability with subsequent medial ankle OA, peroneal tendinopathy, and anteromedial ankle impingement. There are several treatments to address this condition, including tendon lengthening and transfers, and osteotomies. However, arthrodesis may be required for symptomatic OA [69]. Although rare, coalitions can be seen in the setting of a cavus deformity, and imaging should assess for them since this condition would require a realignment arthrodesis rather than an osteotomy.

Congenital vertical talus results from talonavicular dislocation with dorsal navicular displacement. This is associated with dorsolateral ankle and Achilles tendon contractures, along with joint capsular contractures, which causes calcaneal plantar flexion and forefoot dorsiflexion and produces the classic “rocker-bottom deformity.” If left untreated, it can lead to progressively fixed tarsal remodeling and deformity, worsening pain, and functional limitation, such as “peg-leg” gait abnormality. At this stage, triple arthrodesis may be the only treatment option as a salvage procedure [70, 71].

Although clubfoot is often synonymously used with talipes equinovarus, it also includes talipes calcaneovalgus and meta-tarsus varus abnormalities. It may be idiopathic or associated with a number of neuromuscular conditions, primarily affecting the tibiotalar and subtalar joints which may be associated with subtalar subluxation. Untreated cases may result in gait dysfunction due to abnormal foot biomechanics, limb length shortening, and increased joint stiffness, which can progress to tibiotalar and talonavicular joint OA [72].

Charcot or neuropathic arthropathy is the result of microvascular insults and peripheral neuropathies, initially leading to a strong inflammatory response that can mimic infection. In the foot, it most commonly affects the TMT and midtarsal joints. Later, as the inflammatory response subsides, many of the classic imaging findings in hypertrophic neuropathic arthropathy, such as disorganization, fragmentation, and joint destruction are seen. In advanced cases, the collapse of the longitudinal arches may create a rocker-bottom deformity with forefoot abduction and hindfoot valgus. Surgical treatment at this stage can be difficult and consists of exostectomies of protuberant bone, osteotomies, or fusion [73].

Conclusion

The ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot have complex anatomy and biomechanical loads that allow fine balance while walking on uneven terrain. Single or repetitive trauma and injury to the osteoarticular units and stabilizing soft tissue structures can result in instability, OA, deformity, loss of function, and decreased quality of life. Diagnostic imaging is an important tool to detect findings of instability and osteoarthritis and assess its severity, and recognizing patterns of OA and instability can guide therapy. Thus, it is important to understand the imaging modalities used to characterize ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot OA along with the imaging findings associated with various patterns of stability failure.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. David Botos for providing the illustrations.

Funding

Dr. Maria I. Altbach is a co-investigator on NIH grant R01CA245920.

References

- 1.Picavet HS, Schouten JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC(3)-study. Pain. 2003;102(1–2):167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn JE, Link CL, Felson DT, Crincoli MG, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(5):491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snedeker JG, Wirth SH, Espinosa N. Biomechanics of the normal and arthritic ankle joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2012;17(4):517–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, et al. Epidemiology of ankle arthritis: report of a consecutive series of 639 patients from a tertiary orthopaedic center. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:44–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray C, Marshall M, Rathod T, Bowen CJ, Menz HB, Roddy E. Population prevalence and distribution of ankle pain and symptomatic radiographic ankle osteoarthritis in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0193662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paget LDA, Aoki H, Kemp S, et al. Ankle osteoarthritis and its association with severe ankle injuries, ankle surgeries and health-related quality of life in recently retired professional male football and rugby players: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e036775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alajlan A, Santini S, Alsayel F, et al. Joint-preserving surgery in varus ankle osteoarthritis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(8):2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorbachova T, Melenevsky YV, Latt LD, Weaver JS, Taljanovic MS. Imaging and treatment of posttraumatic ankle and hindfoot osteoarthritis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salat P, Le V, Veljkovic A, Cresswell ME. Foot imaging in foot and ankle instability. Ankle Clin. 2018;23(4):499–522.e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byers GE 3rd, Berquist TH. Radiology of sports-related injuries. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1996;25(1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost SC, Amendola A. Is stress radiography necessary in the diagnosis of acute or chronic ankle instability? Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(1):40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LiMarzi GM, Scherer KF, Richardson ML, et al. CT and MR imaging of the postoperative ankle and foot. Radiographics. 2016;36(6):1828–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Do TD, Sutter R, Skornitzke S, Weber MA. CT and MRI techniques for imaging around orthopedic hardware. Rofo. 2018;190(1):31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickle J, Walstra F, Duggan P, Ouellette H, Munk P, Mallinson P. Br Dual-energy CT characterization of winter sports injuries. J Radiol. 2020;93(1106):20190620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godoy-Santos AL, Bernasconi A, Bordalo-Rodrigues M, Lintz F, Lôbo CFT, Netto CC. Weight-bearing cone-beam computed tomography in the foot and ankle specialty: where we are and where we are going - an update. Radiol Bras. 2021;54(3):177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter M, de Cesar NC, Lintz F, Barg A, Burssens A, Ellis S. The assessment of ankle osteoarthritis with weight-bearing computed tomography. Foot Ankle Clin. 2022;27(1):13–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorbachova T Magnetic resonance imaging of the ankle and foot. Pol J Radiol. 2020;18(85):e532–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith JF, Lau DT, Yeung DK, Wong MW. High-resolution MR imaging of talar osteochondral lesions with new classification. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(4):387–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crema MD, Roemer FW, Marra MD, et al. Articular cartilage in the knee: current MR imaging techniques and applications in clinical practice and research. Radiographics. 2011;31(1):37–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae WC, Ruangchaijatuporn T, Chung CB. New techniques in MR imaging of the ankle and foot. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2017;25(1):211–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber MA, Wünnemann F, Jungmann PM, Kuni B, Rehnitz C. Modern cartilage imaging of the ankle. Rofo. 2017;189(10):945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ergün T, Peker A, Aybay MN, Turan K, Muratoğlu OG, Çabuk H. Ultrasonography vıew for acute ankle ınjury: comparison of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance ımaging. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022. 10.1007/s00402-022-04553-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serban O, Bădărînză M, Fodor D. The relevance of ultrasound examination of the foot and ankle in patients with rheumatoid arthritis - a review of the literature. Med Ultrason. 2019;21(2):175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nevalainen MT, Pitkänen MM, Saarakkala S. Diagnostic performance of ultrasonography for evaluation of osteoarthritis of ankle joint: comparison with radiography, cone-beam CT, and symptoms. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(5):1139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taljanovic MS, Gimber LH, Becker GW, et al. Shear-wave elastography: basic physics and musculoskeletal applications. Radiographics. 2017;37(3):855–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimber LH, Daniel Latt L, Caruso C, et al. Ultrasound shear wave elastography of the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments in healthy subjects. J Ultrason. 2021;21(85):e86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nathan M, Mohan H, Vijayanathan S, Fogelman I. Gnanasegaran G The role of 99mTc-diphosphonate bone SPECT/CT in the ankle and foot. Nucl Med Commun. 2012;33(8):799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hintermann B, Ruiz R. Biomechanics of medial ankle and peritalar instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2021;26(2):249–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnel F, Toullec E, Mabit C, Tourné Y, Sofco. Chronic ankle instability: biomechanics and pathomechanics of ligaments injury and associated lesions. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(4):424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown TD, Johnston RC, Saltzman CL, Marsh JL, Buckwalter JA. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: a first estimate of incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(10):739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delco ML, Kennedy JG, Bonassar LJ, Fortier LA. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the ankle: a distinct clinical entity requiring new research approaches. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(3):440–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corte-Real N, Caetano J. Ankle and syndesmosis instability: consensus and controversies. EFORT Open Rev. 2021;6(6):420–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss JE, Forsberg JA, Lippert FG 3rd. Chronic lateral ankle instability and associated conditions: a rationale for treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(10):1041–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Mohrej OA, Al-Kenani NS. Chronic ankle instability: current perspectives. Avicenna J Med. 2016;6(4):103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tourné Y, Besse JL, Mabit C, Sofcot. Chronic ankle instability. Which tests to assess the lesions? Which therapeutic options? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(4):433–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau BC, Allahabadi S, Palanca A, Oji DE. Understanding radiographic measurements used in foot and ankle surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(2):e139–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraus VB, Kilfoil TM, Hash TW 2nd, et al. Atlas of radiographic features of osteoarthritis of the ankle and hindfoot. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(12):2059–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holzer N, Salvo D, Marijnissen AC, et al. Radiographic evaluation of posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the ankle: the Kellgren-Lawrence scale is reliable and correlates with clinical symptoms. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(3):363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takakura Y, Tanaka Y, Kumai T, Tamai S. Low tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the ankle. Results of a new operation in 18 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(1):50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guimarães JB, da Cruz IAN, Nery C, Silva FD, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talar dome: an up-to-date approach to multimodality imaging and surgical techniques. Skeletal Radiol. 2021;50(11):2151–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flores DV, Mejía Gómez C, Fernández Hernando M, Davis MA, Pathria MN. Adult acquired flatfoot deformity: anatomy, biomechanics, staging, and imaging findings. Radiographics. 2019;39(5):1437–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vulcano E, Deland JT, Ellis SJ. Approach and treatment of the adult acquired flatfoot deformity. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(4):294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mengiardi B, Pinto C, Zanetti M. Medial collateral ligament complex of the ankle: MR imaging anatomy and findings in medial instability. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2016;20(1):91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez FM, Harmouche E, Robertson DD, et al. Tenosynovial fluid as an indication of early posterior tibial tendon dysfunction in patients with normal tendon appearance. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48(9):1377–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bartoníček J, Rammelt S, Naňka O. Anatomy of the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2018;23(3):315–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barg A, Tochigi Y, Amendola A, Phisitkul P, Hintermann B, Saltzman CL. Subtalar instability: diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(2):151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rammelt S, Bartoníček J, Park KH. Traumatic injury to the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2018;23(3):353–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan PS, Kong KO. Int natural history and imaging of subtalar and midfoot joint disease in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheum Dis. 2013;16(1):14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersen LB, Stauff MP, Juliano PJ. Combined subtalar and ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007;12(1):57–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephens AR, Grujic L. Post-traumatic hindfoot arthritis. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34(Suppl 1):S32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brodén B Roentgen examination of the subtaloid joint in fractures of the calcaneus. Acta radiol. 1949;31(1):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colin F, Horn Lang T, Zwicky L, Hintermann B, Knupp M. Subtalar joint configuration on weightbearing CT scan. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(10):1057–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez-Ben R Imaging of the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Clin. 2015;20(2):223–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walter WR, Hirschmann A, Alaia EF, Tafur M, Rosenberg ZS. Normal anatomy and traumatic injury of the midtarsal (chopart) joint complex: an imaging primer. Radiographics. 2019;39(1):136–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Czajka CM, Tran E, Cai AN, DiPreta JA. Ankle sprains and instability. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98(2):313–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu SH, Jason WJ. Lateral ankle sprains and instability problems. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13(4):793–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Main BJ, Jowett RL. Injuries of the midtarsal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57(1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walter WR, Hirschmann A, Tafur M, Rosenberg ZS. Imaging of Chopart (Midtarsal) Joint complex: normal anatomy and post-traumatic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(2):416–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ebalard M, Le Henaff G, Sigonney G, et al. Risk of osteoarthritis secondary to partial or total arthrodesis of the subtalar and midtarsal joints after a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(4 Suppl):S231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurup H, Vasukutty N. Midfoot arthritis- current concepts review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(3):399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ulbrich EJ, Zubler V, Sutter R, Espinosa N, Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M. Skeletal Ligaments of the Lisfranc joint in MRI: 3D-SPACE (sampling perfection with application optimized contrasts using different flip-angle evolution) sequence compared to three orthogonal proton-density fat-saturated (PD fs) sequences. Radiol. 2013;42(3):399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siddiqui NA, Galizia MS, Almusa E, Omar IM. Evaluation of the tarsometatarsal joint using conventional radiography, CT, and MR imaging. Radiographics. 2014;34(2):514–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnold JB, Marshall M, Thomas MJ, Redmond AC, Menz HB, Roddy E. Midfoot osteoarthritis: potential phenotypes and their associations with demographic, symptomatic and clinical characteristics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(4):659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maurer JD, Ward V, Mayson TA, et al. Classification of midfoot break using multi-segment foot kinematics and pedobarography. Gait Posture. 2014;39(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menz HB, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB, Zammit GV, Cicuttini FM. Osteoarthritis radiographic classification of osteoarthritis in commonly affected joints of the foot. Cartilage. 2007;15(11):1333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steadman J, Sripanich Y, Rungprai C, Mills MK, Saltzman CL, Barg A. Comparative assessment of midfoot osteoarthritis diagnostic sensitivity using weightbearing computed tomography vs weightbearing plain radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2021;134:109419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verhoeven N, Vandeputte G. Midfoot arthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(4):255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berlet GC, Hodges Davis W, Anderson RB. Tendon arthroplasty for basal fourth and fifth metatarsal arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23(5):440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacobs AM. Pes Cavus Deformity: anatomic, functional considerations, and surgical implications. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38(3):291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wirth T Congenital vertical talus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2021;26(4):903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller M, Dobbs MB. Congenital vertical talus: etiology and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(10):604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallander H, Saebö M, Jonsson K, Bjönness T, Hansson G. Low prevalence of osteoarthritis in patients with congenital clubfoot at more than 60 years’ follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11):1522–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doorgakant A, Davies MB. An approach to managing midfoot charcot deformities. Foot Ankle Clin. 2020;25(2):319–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]