Significance

Biased ligand pharmacology seeks to develop agents that can activate a subset of a receptor’s signaling capabilities. The β2AR (β2-adrenergic receptor) exhibits pleiotropic signaling and efforts to develop biased ligands have focused on agents that selectively activate either the canonical Gs pathway or β-arrestin pathway. Here we have identified a biased allosteric modulator that selectively inhibits β-arrestin interaction with the β2AR without affecting β-agonist-promoted cAMP production. This allosteric modulator attenuates functional desensitization of the β2AR in airway smooth muscle, augmenting the ability of β-agonists to sustain bronchorelaxation and inhibition of cell migration under conditions of chronic β-agonist treatment. This work thus identifies an allosteric modulator capable of effecting Gs-biased β2AR signaling and suggests the clinical utility of biased ligand identification.

Keywords: cell signaling, asthma, G protein–coupled receptor, biased signaling, negative allosteric modulator

Abstract

Catecholamine-stimulated β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) signaling via the canonical Gs–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–PKA pathway regulates numerous physiological functions, including the therapeutic effects of exogenous β-agonists in the treatment of airway disease. β2AR signaling is tightly regulated by GRKs and β-arrestins, which together promote β2AR desensitization and internalization as well as downstream signaling, often antithetical to the canonical pathway. Thus, the ability to bias β2AR signaling toward the Gs pathway while avoiding β-arrestin-mediated effects may provide a strategy to improve the functional consequences of β2AR activation. Since attempts to develop Gs-biased agonists and allosteric modulators for the β2AR have been largely unsuccessful, here we screened small molecule libraries for allosteric modulators that selectively inhibit β-arrestin recruitment to the receptor. This screen identified several compounds that met this profile, and, of these, a difluorophenyl quinazoline (DFPQ) derivative was found to be a selective negative allosteric modulator of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR while having no effect on β2AR coupling to Gs. DFPQ effectively inhibits agonist-promoted phosphorylation and internalization of the β2AR and protects against the functional desensitization of β-agonist mediated regulation in cell and tissue models. The effects of DFPQ were also specific to the β2AR with minimal effects on the β1AR. Modeling, mutagenesis, and medicinal chemistry studies support DFPQ derivatives binding to an intracellular membrane-facing region of the β2AR, including residues within transmembrane domains 3 and 4 and intracellular loop 2. DFPQ thus represents a class of biased allosteric modulators that targets an allosteric site of the β2AR.

Conventional G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) drug discovery strategies frequently investigate only the endogenous ligand binding or orthosteric site of a receptor (1, 2). Molecules targeting this site in the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) typically promote the full complement of β2AR signaling and regulatory protein interactions similar to the endogenous ligands epinephrine and norepinephrine, which includes G protein activation, receptor phosphorylation, β-arrestin interaction, and receptor internalization. Targeting the orthosteric site consequently couples the therapeutic and iatrogenic effects of β-agonists. Moreover, molecules targeting the orthosteric site may suffer from poor receptor subtype selectivity, often leading to off-target side effects. Allosteric ligands of GPCRs can overcome the limitations associated with targeting only the orthosteric site of a receptor and have the ability to bias GPCR signaling (3, 4). Additionally, the discovery of biased ligands that would uncouple these events is frequently excluded by experimental design (i.e., single endpoint measurements) and is complicated by confounding influences of system biases (i.e., nonphysiological cell background and overexpression of target receptor) (1). These problems were considered in the experimental design for the identification and characterization of compounds described in the present work.

The β2AR is a central therapeutic target in multiple diseases, and the ability to bias β2AR signaling offers the possibility of a more refined, effective treatment. In the management of obstructive lung disease, β-agonists are effective in relaxing contracted airway smooth muscle (ASM) to increase airway patency and the ability to breathe (5). However, chronic use of β-agonists can lead to a loss of therapeutic response and promote severe adverse effects (6). Recent studies have implicated β-arrestins as contributing to a pro-inflammatory and pathogenic effect of β-agonists in murine models of asthma (7–9) and that strategies to bias β2AR signaling toward the Gs–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–PKA pathway may attenuate the harmful effects of β-agonists while maintaining therapeutic response (3, 8–11). We and others recently corroborated the potential beneficial effects of Gs selective activation by identifying a set of Gs-biased β-agonists that were able to protect human ASM (HASM) cells from agonist-induced desensitization in vitro (12, 13).

To identify allosteric modulators promoting Gs-biased signaling through the β2AR, small-molecule libraries were screened in the presence of the β-agonist isoproterenol (ISO) to identify compounds that would selectively inhibit β-arrestin recruitment to the receptor. This screen identified a difluorophenyl quinazoline (DFPQ) derivative, which was found to be a selective, negative allosteric modulator (NAM) of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR without inhibiting β2AR coupling to Gs. DFPQ effectively inhibits agonist-promoted phosphorylation and internalization of the β2AR and protects against the functional desensitization of β-agonist-mediated regulation in airway cells and tissue. The effects of DFPQ were also specific to the β2AR with minimal effects on β-arrestin recruitment to the β1AR. Molecular modeling and mutagenesis studies support DFPQ binding to the residues within transmembrane domains 3 and 4 and intracellular loop 2 of the β2AR. The ability of DFPQ to mitigate β2AR desensitization was reflected in functional assays in a greater ability of β-agonists to 1) relax contracted ASM upon rechallenge after chronic agonist treatment; and 2) inhibit ASM cell migration, two functions of ASM shown to be PKA-dependent (14, 15). This work establishes the potential clinical utility of biased allosteric modulator identification for the β2AR and provides insight into the mechanism of β-arrestin biased negative allosteric modulation of the receptor.

Results

Identifying Small-Molecule Allosteric Modulators of the β2AR.

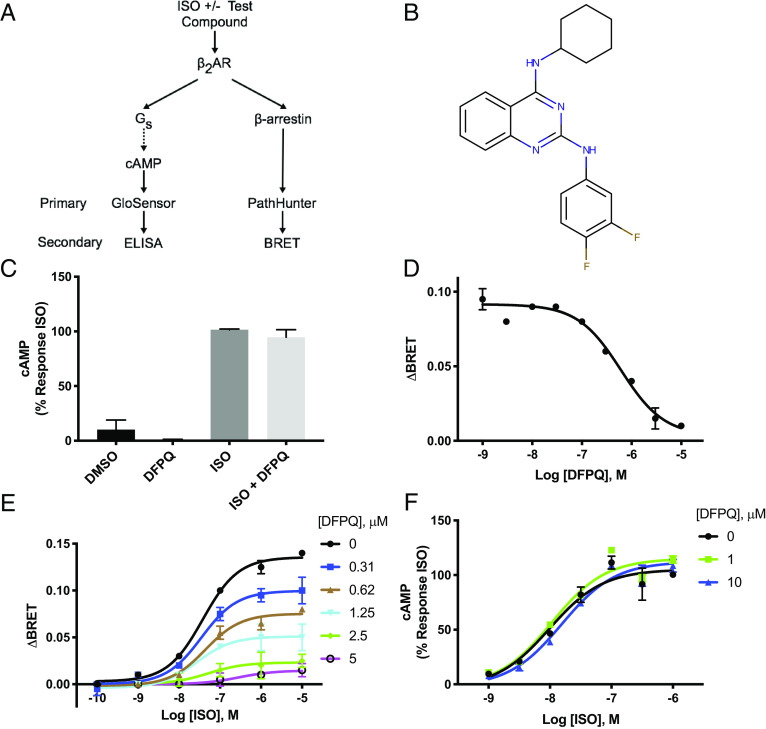

In an effort to identify small-molecule allosteric modulators of the β2AR, compounds were screened in orthogonal primary and secondary assays for cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production and β-arrestin2 recruitment to the β2AR. In primary screens, cells expressing β2AR were stimulated with the β-agonist ISO in the presence or absence of 10 μM test compounds and evaluated for cAMP production using the GloSensor™ assay and β2AR/β-arrestin2 association using the PathHunter™ ADRB2 assay. Hits from primary screening were then titrated in GloSensor and PathHunter assays in order to identify compounds capable of inhibiting ISO-promoted β-arrestin2 recruitment in a dose-dependent manner with minimal effect on cAMP production. The most potent compounds displaying NAM activity in the primary screens were further characterized by competitive ELISA to measure cAMP production and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to analyze β-arrestin2 recruitment to the β2AR. The orthogonal nature of the detection methods used for primary and secondary screening allowed us to confirm compound-induced phenotypes and rule out false positives arising from assay artifacts. This assay schema is summarized in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Identifying small-molecule allosteric modulators of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR. (A) Schematic of screening methodologies for cAMP production and β-arrestin binding. Cells were treated with ISO ± test compounds. The primary high throughput screen utilized a luciferase-based cAMP biosensor, GloSensor (Promega), and an enzyme complementation-based assay, PathHunter (DiscoveRx). Independent secondary screening utilized a cAMP ELISA and a BRET assay for β-arrestin recruitment. (B) Structure of DFPQ. (C) Secondary screen for cAMP production by ELISA. HEK 293 cells stably expressing β2AR were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO (negative control) or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min and then stimulated with or without 1 μM ISO for 10 min. Cells were lysed and cAMP production was measured. Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 3. (D) Dose–response curve for DFPQ as measured by BRET. HEK 293 cells cotransfected with β-arrestin2-GFP10 and β2AR-RlucII were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO (negative control) or the indicated concentrations of DFPQ for 30 min. Cells were incubated with Coelenterazine 400a for 2 min and then stimulated with 1 μM ISO. Data for the dose–response curve was taken 12 min post-ISO addition. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 3. (E) HEK 293 cells cotransfected with β-arrestin2-GFP10 and β2AR-RLucII were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of DFPQ for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with Coelenterazine 400a for 2 min and then stimulated with the indicated concentrations of ISO. Data for dose–response curves were taken 12 min post-ISO addition and are the mean ± SEM, n = 3. (F) HEK 293 cells stably expressing β2AR were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO (negative control), 1 μM DFPQ, or 10 μM DFPQ and stimulated with the indicated concentrations of ISO for 10 min. Cells were lysed and cAMP production was measured by ELISA. Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 3.

Primary screening of diverse small-molecule libraries totaling more than 152,000 compounds identified 578 compounds that scored as either β-arrestin NAMs or positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of ISO-stimulated cAMP production. Titration of these hits confirmed 57 compounds that displayed biased inhibition of ISO-mediated β-arrestin2 recruitment to the β2AR relative to ISO-stimulated cAMP production. These compounds represented three distinct chemical scaffolds with quinazoline derivatives being the most populated class. Compounds that demonstrated the desired signaling properties were further investigated in secondary assays. The most potent of these compounds, a (m, p‐difluorophenyl) quinazoline derivative (DFPQ) (Fig. 1B), selectively inhibited β-arrestin2 binding in the primary and secondary screens with no effect on ISO-stimulated cAMP production (Fig. 1C) and potent inhibition of β-arrestin binding to the β2AR with an IC50 of ~0.6 μM (Fig. 1D). This signaling profile was maintained for pharmacologically distinct β-agonists including the full agonist BI-167107 and the partial agonist salmeterol (SALM) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–C). Thus, our screening identified DFPQ as a biased modulator of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR.

To further confirm an allosteric mechanism of action, we used a combination of functional assays to pharmacologically profile the interaction of DFPQ with the β2AR. Typically, functional readouts of NAMs would be expected to demonstrate a decreased maximal response to an orthosteric agonist in the presence of increasing concentrations of the modulator. We evaluated these properties for ISO dose–response curves in cells treated with increasing concentrations of DFPQ. In order to incorporate the biased nature of the effects of DFPQ on β2AR signaling, these experiments were performed for both β-arrestin recruitment and cAMP production. Using β-arrestin recruitment as a functional readout, ISO dose–response curves demonstrate the classical decreased response typical of NAMs at increasing concentrations of DFPQ (Fig. 1E). Global curve fitting and Schild analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D) of these data demonstrate noncompetitive inhibition supporting an allosteric mechanism of action for this response. Notably, increasing concentrations of DFPQ up to 10 μM have no effect on ISO dose–response curves using cAMP production as a functional readout (Fig. 1F), while higher concentrations cause some inhibition with an IC50 of ~50 μM (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). In addition, 10 μM DFPQ treatment in the absence of ISO had no effect on basal cAMP production or β-arrestin recruitment (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). Furthermore, DFPQ had no effect on ISO-dependent activation of purified Gs by the β2AR as assessed by radiolabeled GTPγS binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). These results show that in the presence of ISO and DFPQ, the efficacy for β-arrestin recruitment is diminished, while efficacy for Gs activation is unaffected. This suggests that DFPQ is a β-arrestin biased NAM.

Receptor Specificity of DFPQ.

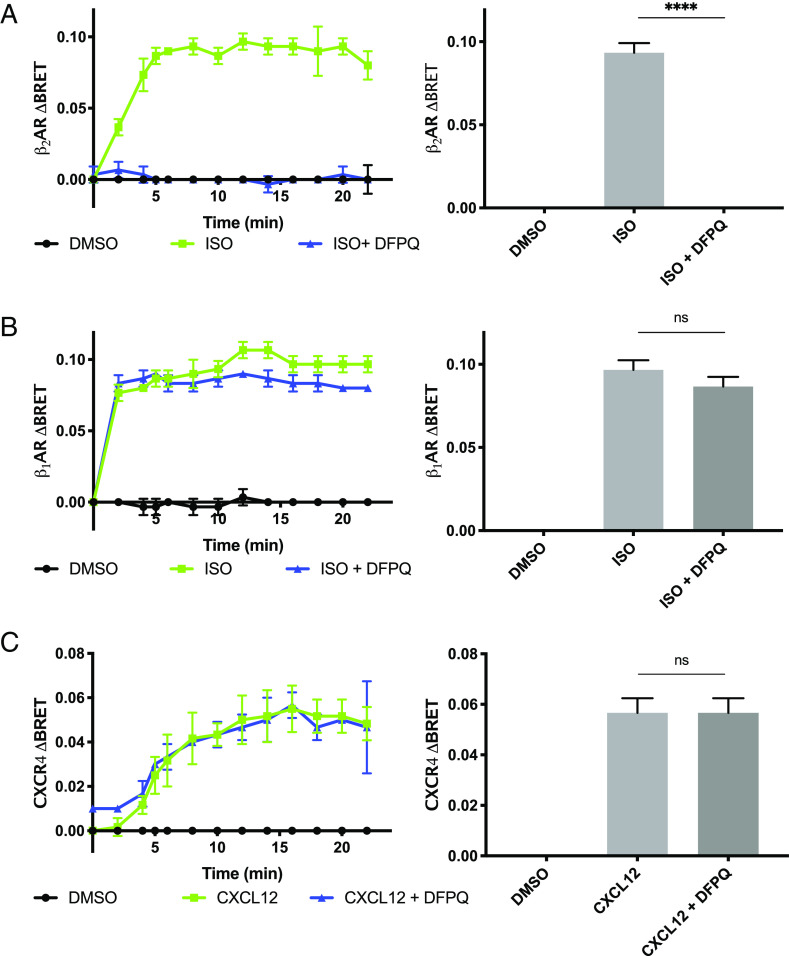

Therapeutic compounds often have undesirable side effects due to off-target interactions (16). A goal of investigating β2AR allosteric modulators is the potential high degree of receptor specificity that can be achieved when targeting domains outside of the endogenous ligand-binding site. Domains that have not coevolved with receptor family members for binding endogenous ligands are less conserved and can therefore be used to chemically discriminate between related receptors (17). To evaluate receptor specificity, we used a BRET assay to compare the effect of DFPQ on β-arrestin interaction with the β2AR, β1AR, and CXCR4. Evaluating both the peak BRET signal and extended time course for agonist-promoted β2AR/β-arrestin2 interaction shows that β-arrestin2 recruitment to the β2AR is fully inhibited by 10 μM DFPQ over the measured time course (Fig. 2A). In contrast, β-arrestin2 interaction with the β1AR, the most homologous GPCR to the β2AR, is inhibited approximately 10% by 10 μM DFPQ (Fig. 2B). Additionally, there was no effect of DFPQ on β-arrestin2 interaction with the unrelated chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that DFPQ is highly selective for the β2AR and is acting through a receptor-specific mechanism rather than broadly inhibiting β-arrestin interaction with GPCRs.

Fig. 2.

GPCR specificity of DFPQ. HEK 293 cells were cotransfected with β-arrestin2-GFP10 and either β2AR-RlucII (A), β1AR-RlucII (B), or CXCR4-RlucII (C) for 48 h and cells were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO (negative control) or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with Coelenterazine 400a for 2 min and stimulated with 1 μM of the indicated agonist. Cells were read every 2 min post agonist addition. One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was performed to compare the means of each treatment group. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 3. ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant

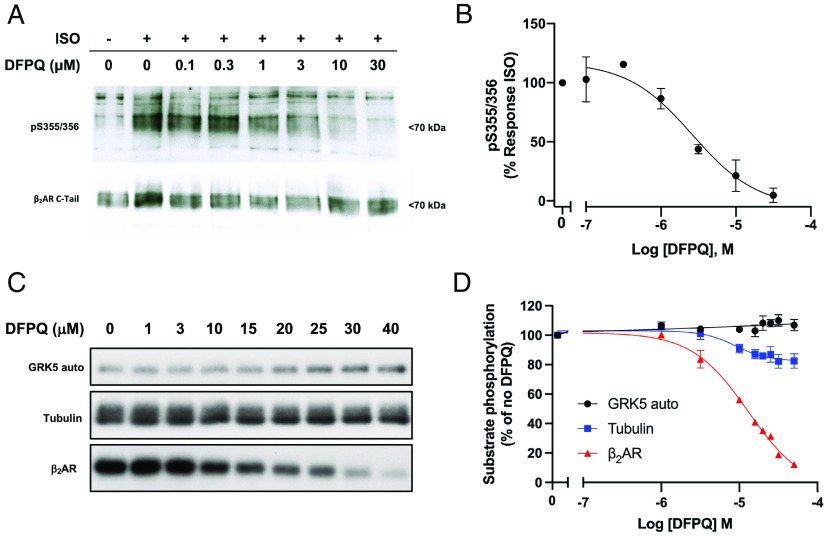

DFPQ Inhibits GRK-Mediated Phosphorylation of the β2AR.

It has been established that GPCR kinases (GRKs) play a role in orchestrating biased agonism at the β2AR as receptor phosphorylation is a prerequisite for the recruitment of β-arrestin (18). To investigate the mechanistic role of β2AR phosphorylation by GRKs on the observed signaling phenotype demonstrated by DFPQ, we next evaluated the effect of DFPQ on agonist-promoted phosphorylation of the β2AR. In-cell phosphorylation of the β2AR was examined in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing FLAG-tagged β2AR and was monitored using a phospho-specific antibody targeting pSer355/356, a primary site of GRK6-mediated phosphorylation in the β2AR (19). The cells were stimulated with ISO in the presence of a range of DFPQ concentrations. Treatment with ISO alone induced robust phosphorylation of the β2AR, while DFPQ effectively inhibited ISO-stimulated phosphorylation with an IC50 of 2.6 ± 1.0 μM (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

DFPQ inhibits GRK-mediated phosphorylation of the β2AR. (A) Representative time course of agonist promoted phosphorylation of the β2AR. HEK 293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO or indicated concentrations of DFPQ for 30 min and then stimulated with 1 μM ISO for 10 min. Cells were lysed and the FLAG-β2AR was immunoprecipitated. Phosphorylation at serine 355 and 356 was analyzed by western blot using a pSer355/356 antibody while total β2AR was measured using a β2AR C-terminal antibody. The western blot is representative of at least three experiments. (B) Densitometric quantification for concentration–activity curve-fitting from panel A is shown. Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 3. (C) A representative autoradiograph of GRK5 autophosphorylation and GRK5-mediated phosphorylation of tubulin and the β2AR in the presence of 1 μM ISO and the indicated concentration of DFPQ. The apparent small increase in GRK5-autophosphorylation was not consistent across the three replicates, as shown by the average quantification in panel D. (D) In vitro phosphorylation data from three experiments were quantified and are shown as a percentage of no DFPQ. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3. Concentration–activity curves were generated by fitting the western blot densitometric data to the logistic equation log(inhibitor) vs. response (three parameters) while data from autoradiography were fit using the logistic equation log(inhibitor) vs. response (four parameters, variable slope). All curves were generated using GraphPad Prism.

To determine whether the inhibition of GRK-mediated phosphorylation of the β2AR in cells could be a function of inhibiting GRK catalytic activity, the effect of DFPQ on GRK5-mediated autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of a nonreceptor substrate such as tubulin were measured in vitro. We specifically selected GRK5 due to its higher in vitro catalytic activity compared to other GRKs, and GRK5-mediated 32P incorporation into the different substrates upon DFPQ treatment was measured using autoradiography. The analysis showed that GRK5 autophosphorylation was unaffected by DFPQ, while phosphorylation of tubulin was impacted negligibly (Fig. 3 C and D). In contrast, we also evaluated the effect of DFPQ on agonist-promoted phosphorylation of purified β2AR by GRK5 and found that DFPQ inhibited phosphorylation, albeit with an IC50 of 18 ± 3 μM (Fig. 3 C and D).

These results suggest that DFPQ is likely stabilizing a conformation of the β2AR that is unfavorable for GRK-mediated phosphorylation while also demonstrating that DFPQ has no direct effect on GRK catalytic activity. The disruption of β2AR phosphorylation by DFPQ likely contributes to the observed β-arrestin bias of this compound.

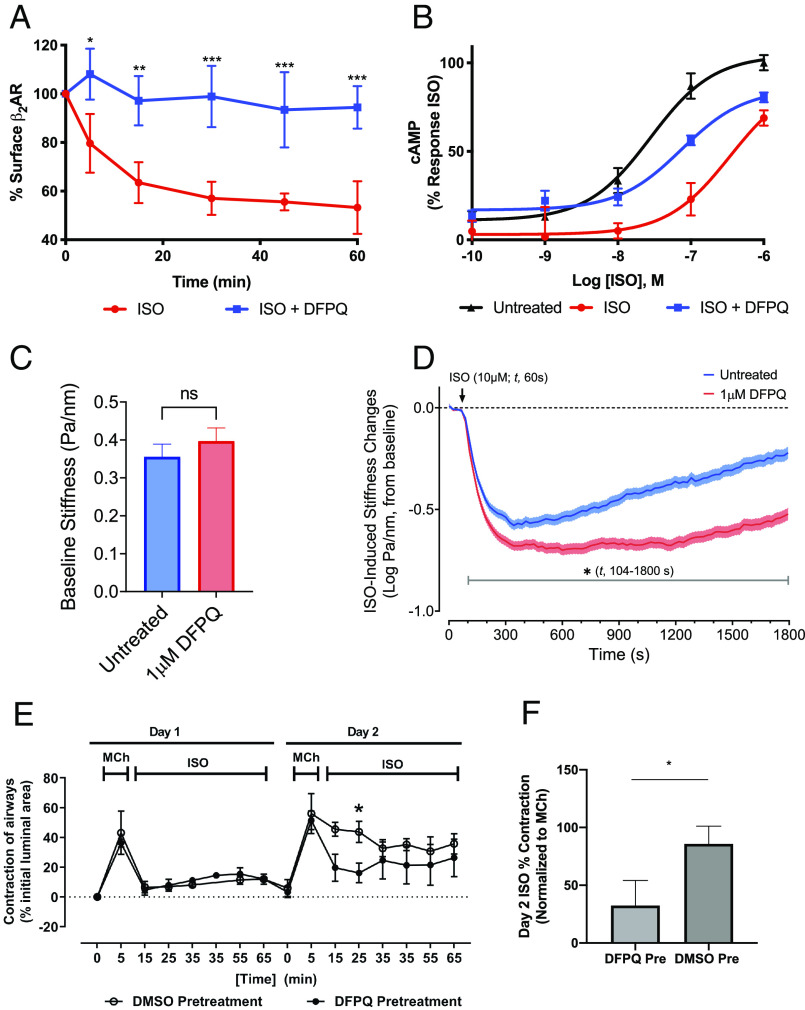

DFPQ Treatment Antagonizes Agonist-Promoted β2AR Internalization and Desensitization.

β-arrestin binding to the β2AR is essential for agonist-promoted internalization of the receptor (20). To evaluate the ability of DFPQ to modulate β2AR internalization, cell surface expression of FLAG-tagged β2AR was measured by ELISA post-ISO stimulation. ISO induced a rapid decrease in cell surface expression of the β2AR sustained over a 60-min time-course, while agonist-induced internalization of the receptor was completely inhibited by DFPQ (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

DFPQ inhibits internalization of the β2AR and protects from agonist-induced desensitization in cell and tissue models. (A) Effect of DFPQ on agonist-promoted internalization of the β2AR. HEK 293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were preincubated with 0.1% DMSO or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min and then stimulated with 10 μM ISO for up to 60 min. Cells were fixed and receptor surface expression was measured by ELISA. These data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 (B) HEK 293 cells were desensitized by incubating with 1 μM ISO ± 10 μM DFPQ, washed with PBS, then stimulated with ISO at the indicated concentrations for 10 min. Cells were lysed and cAMP production was measured by ELISA. Cells incubated with DFPQ during desensitization were protected from reduced response to agonist after wash. Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3. (C) Comparison of the stiffness in HASM cells following a 30 min pretreatment with (n = 473 individual cell measurements) or without (n = 463 individual cell measurements) 1 μM DFPQ. Histograms are represented as geometric mean ± 95% CIs. (D) Functional desensitization of the β2AR was studied by pretreating HASM cells with or without 1 μM DFPQ for 30 min, followed by relaxation over a 30 min period induced by 10 μM ISO. Data are collected at every 1.3 s (t, 0 to 1,800 s) and presented as estimated mean ± SE (n = 463 to 473 cell measurement per treatment). (E) Murine precision cut lung slices were contracted with 1 μM methacholine for 5 min and then incubated overnight with 1 μM ISO ± 1 μM DFPQ. Airway slices were washed, recontracted with methacholine, and incubated with ISO for 1 h (n = 4 airways). Airway contractility was measured by the luminal area of bronchioles by microscopy at various times. (F) Bar graphs represent normalized ISO-promoted relaxation from methacholine contraction on day 2 of treatment at the 25 min time point from 4 airways. Statistical significance (*) in panels E and F were assessed using an unpaired t test, P < 0.05.

To evaluate whether DFPQ can inhibit agonist-induced desensitization of the β2AR, we established an in-cell desensitization assay to monitor cAMP response after sustained agonist treatment. HEK 293 cells were stimulated with ISO for 30 min in the presence or absence of DFPQ, washed, and then restimulated with various doses of ISO to generate dose–response curves for cAMP production. Relative to a control-generated from cells that were not pretreated with ISO, a 15-fold right-shift in the ISO EC50 was observed (29 ± 6 nM in control vs. 432 ± 140 nM in ISO pretreated cells) (Fig. 4B). Addition of 10 μM DFPQ during the 30 min ISO pretreatment largely protected against this desensitization (EC50 = 74 ± 5 nM). Taken together, these data demonstrate that DFPQ effectively attenuates agonist-induced desensitization and internalization of the β2AR.

ASM Function Is Protected from Desensitization by DFPQ Treatment.

The pathophysiology of asthma is complex and multifactorial (21). In order to examine the observed protective effects of DFPQ on β2AR desensitization in a physiologically relevant system, we recapitulated in-cell desensitization experiments in primary HASM cells and mouse airway tissue.

In HASM cell experiments, ISO-mediated cellular relaxation was evaluated in the presence or absence of DFPQ, using magnetic twisting cytometry (MTC) (22). For these studies, HASM cells were pretreated with or without 1 μM DFPQ for 30 min. Preincubation with DFPQ had little effect on HASM cell stiffness, confirming the lack of activity in the absence of the agonist (Fig. 4C). To evaluate agonist-promoted functional desensitization of the β2AR, ISO-induced HASM cell relaxation was continuously monitored for 30 min. Peak relaxation was observed after ~4 to 5 min, and this was followed by a gradual loss of relaxation over the remaining time course (Fig. 4D). Compared with untreated cells, however, cells that were pretreated with DFPQ showed significantly greater ISO-induced relaxation that was evident within ~44 s after agonist addition (Fig. 4D). Most strikingly, the extent of HASM cell relaxation was prolonged and largely sustained through 30 min with DFPQ treatment (Fig. 4D).

In mouse airway experiments, the muscarinic receptor agonist methacholine was used to contract mouse ASM. The contraction was rapidly reversed by treatment with ISO in the presence or absence of DFPQ (Fig. 4E, day 1). The following day, and after chronic (overnight) exposure to ISO, airway tissues were washed, rechallenged with methacholine and again treated with ISO and airway contractility measured. In this ex vivo model for agonist-induced desensitization of response, ISO-mediated reversal of airway contraction was significantly desensitized on day 2 but was largely preserved in the DFPQ pretreated tissue relative to control (Fig. 4E). DFPQ shows significant protection from desensitization up to 25 min post-ISO challenge on day 2 (Fig. 4F). This result is consistent with the observed biochemical and cell data, and suggests that DFPQ can effectively mitigate β2AR desensitization in a physiologically relevant system.

We further investigated the effects of DFPQ on β-agonist regulation of primary HASM cell migration using a scratch assay. HASM migration is believed to contribute to deleterious airway remodeling that leads to irreversible lung resistance in chronic asthma (23, 24). The Gs–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–PKA signaling axis is inhibitory to this HASM migration (15). At 24 h postscratch (T0), HASM cells incubated with 20 ng/mL platelet-derived growth factor (DMSO control) migrated into the scratched area while addition of ISO partially inhibited migration (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The effect of ISO was significantly enhanced in the presence of 1 μM DFPQ (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). We also evaluated the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (FSK) and the β-agonist salmeterol in this assay and found that both inhibited migration and that the effect of salmeterol was significantly enhanced in the presence of 1 μM DFPQ (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). These data demonstrate that DFPQ enhances Gs-dependent effects of β-agonists in primary HASM cells. Collectively, results from our studies of HASM function suggest that β-arrestin-biased NAMs such as DFPQ may serve as a potential adjunct therapy to improve β-agonist treatment of asthma.

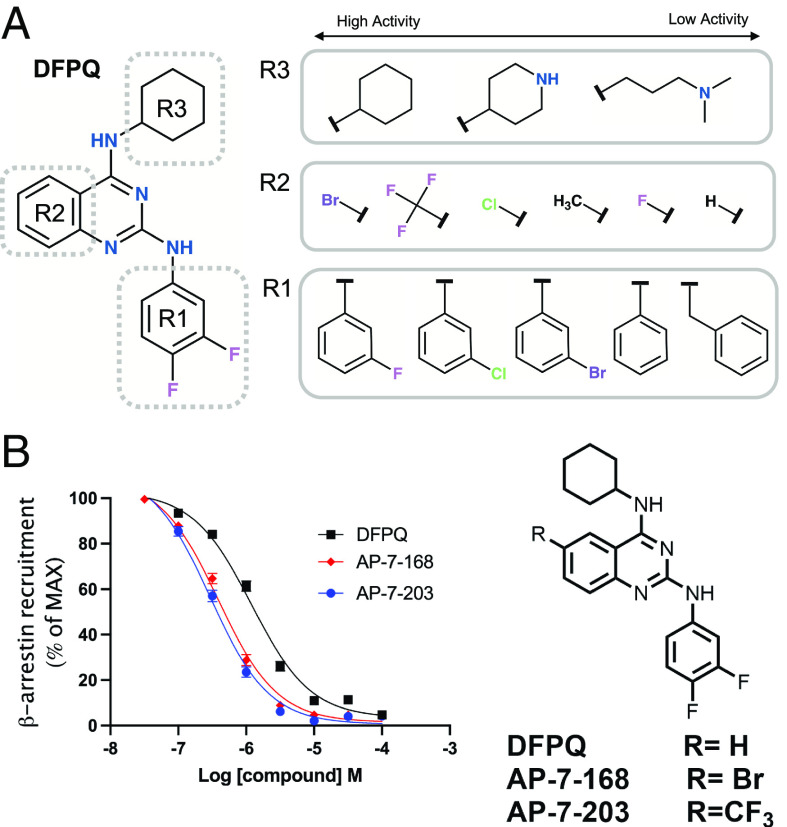

Structure–Activity Relationship of Quinazolines and Inhibition of β-Arrestin Recruitment.

To assess structure–activity relationships of DFPQ, chemically related quinazoline structures present in the primary compound library were evaluated by dose–response analysis using the screening assays shown in Fig. 1A. General trends from this analysis are represented in Fig. 5A. From these studies, it was determined that R1 substitutions of the difluorophenyl head group modulated efficacy and affinity (SI Appendix, Table S1). The most important substituent for efficacy is the para-fluoro moiety at the 4 position of the phenyl group with 4-fluorophenyl substitution demonstrating the highest efficacy for inhibition of β-arrestin recruitment. An unmodified phenyl ring is ~10-fold less potent, while chloro substituents of the phenyl group also show a significant decrease in efficacy particularly at the meta position. Most substitutions of the phenyl ring with other groups also significantly reduced potency. R3 substitutions of the cyclohexane group were determined to be a potential driver of signaling bias; however, R3 substitutions containing the difluorophenyl head group were poorly represented in the library, making direct comparisons difficult. Nevertheless, all substitutions of the cyclohexane reduced potency and all had reduced β-arrestin bias. R2 substitutions of the quinazoline ring scaffold were also poorly represented in the library although addition of a methyl or chloro to the quinazoline at position 7 reduced potency.

Fig. 5.

SAR of quinazolines in inhibition of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR. (A) Functional groups for which substitutions were present either in the screening or from medicinal chemistry. Representative structures for R1, R2, and R3 substitutions ranked from high to low activity for inhibition of β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR are shown. (B) Concentration–activity curves for inhibition of ISO-induced β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR by DFPQ, a bromo-derivative of DFPQ (AP-7-168), and a trifluoromethyl-derivative of DFPQ (AP-7-203). Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 9. The chemical structures of AP-7-168 and AP-7-203 are shown.

To try to improve the potency of DFPQ, we synthesized several additional derivatives. We found that addition of a Br, Cl, or F3C to the 6-position of the quinazoline ring enhanced the affinity of these compounds ~5- to 10-fold compared to the parent compound, while the addition of a methyl had no effect (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. 5A). Thus, the most potent compounds identified were a 2,4-diamino-6-bromo-quinazoline (AP-7-168) and 2,4-diamino-6-trifluoromethyl-quinazoline (AP-7-203) containing a cyclohexyl at the 4 position and difluorophenyl at the 2 position (Fig. 5D). A comparison of DFPQ and these compounds inhibiting ISO-mediated β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR is shown (Fig. 5B).

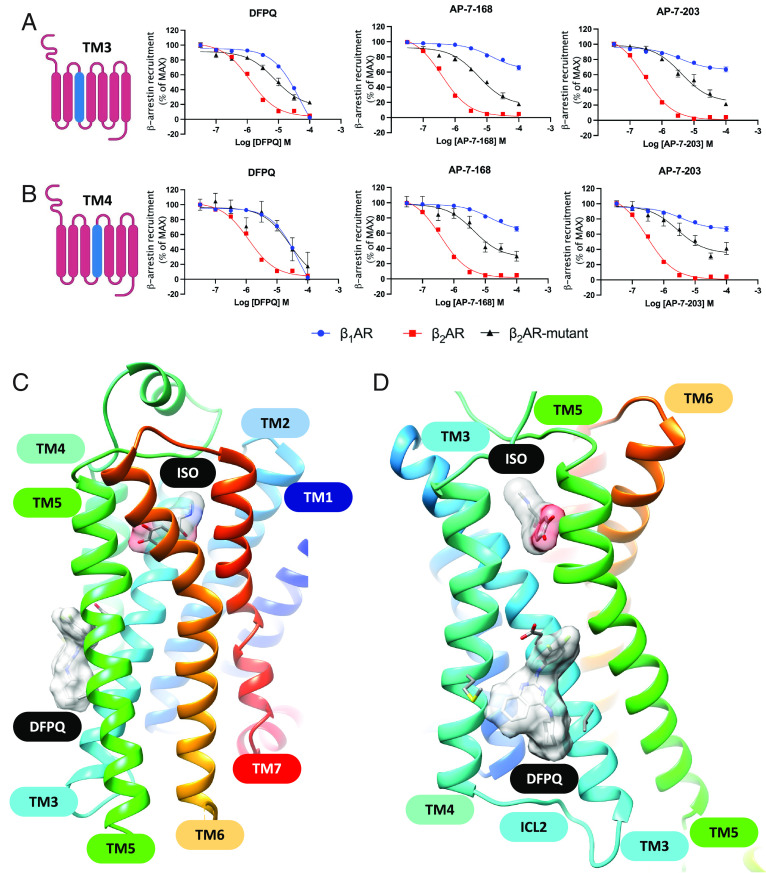

Interaction of DFPQ Derivatives with an Allosteric Site in the β2AR.

To better understand the binding site of DFPQ on the β2AR, we performed mutagenesis studies using chimeras that swapped various regions of the β2AR with the corresponding region of the β1AR. Since DFPQ shows minimal activity at the β1AR (Fig. 2B), we used this as a starting point for identifying key regions underlying this difference. The domains that were swapped included extracellular loop 1 (ECL1), ECL2, ECL3, ECL1/2, ECL1/3, ECL2/3, transmembrane domain 2 (TM2), TM3, TM4, TM5, TM6, TM7, and intracellular loop 1 (ICL1), ICL2, and ICL3. Concentration-activity studies were then performed and showed that DFPQ inhibits β-arrestin binding to the β2AR with an IC50 of ~400 nM while binding to the β1AR was inhibited with an IC50 of ~10 μM. While most of the chimeras had a minimal effect on DFPQ inhibition of β-arrestin binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), the TM3 and TM4 chimeras almost completely shifted the dose response to that of the β1AR, while the ICL2 swap reduced inhibition several-fold (Fig. 6 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table S2). Interestingly, a few of the chimeras such as ECL1 and TM5 appeared to be more effectively inhibited by DFPQ compared to the β2AR. We also evaluated the ability of the 6-bromo and 6-trifluoromethyl DFPQ derivatives to inhibit β-arrestin binding to the β2AR, β1AR, and chimeras. Surprisingly, the bromo and trifluoromethyl derivatives were much more selective for the β2AR vs β1AR compared to DFPQ with less than 50% inhibition observed at 100 μM. This enhanced our ability to dissect the role of the various receptor regions involved in binding. Here, we saw ~50% reduced affinity for the ICL2 chimera, while the TM3 and TM4 swaps had ~10-fold loss of binding (Fig. 6 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5 and Table S2). To exclude the possibility that the observed effects were impacted by nonfunctional chimeras, we tested the ability of the TM3, TM4, and ICL2 chimeras to recruit β-arrestin upon stimulation with ISO compared to WT. While TM3 and ICL2 chimeras didn’t show any difference compared to WT β2AR, TM4 chimeras had no difference in potency but displayed an ~70% reduced efficacy (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Table S4). Taken together, DFPQ appears to be primarily binding to residues in TM3 and TM4 with potential interaction with ICL2.

Fig. 6.

Identification of a DFPQ binding site on the β2AR. Concentration–activity curves for DFPQ-, AP-7-168- and AP-7-203-mediated inhibition of β-arrestin recruitment to the β1AR and β2AR compared with chimeras generated by swapping TM3 (A) or TM4 (B) from the β1AR into the β2AR. Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 3. (C and D). Two views of the best docking model for DFPQ bound to the β2AR at a site between TM3 and TM4. ISO and DFPQ are shown as a molecular surface.

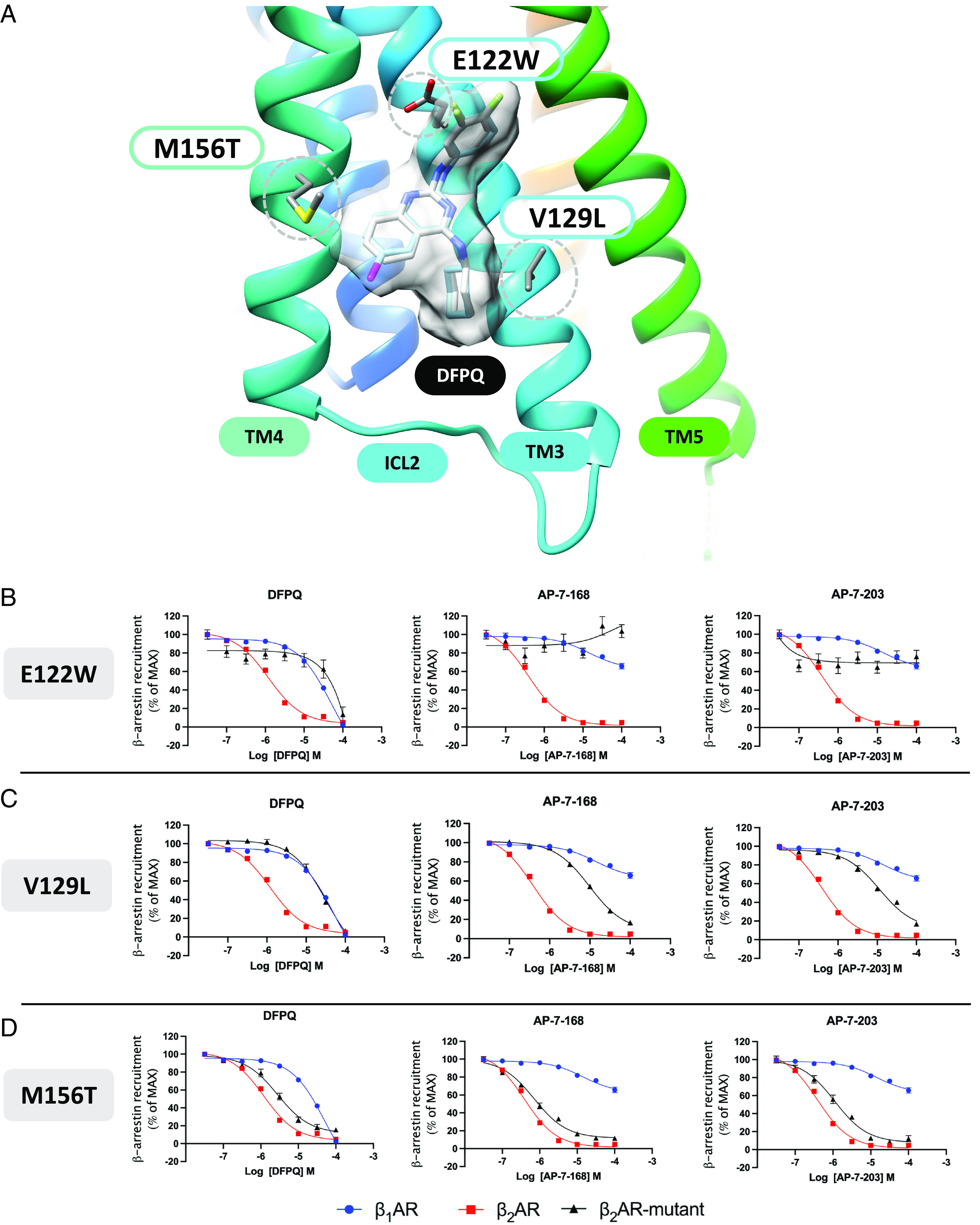

To better understand the specific residues that contribute to DFPQ binding, we performed site-directed mutagenesis targeting residues in TM3, TM4, and ICL2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Analysis of an extensive series of β2AR point mutants showed the largest shifts for some individual residues within TM3 and TM4, defining an intracellular membrane-facing small-molecule binding site. Molecular modeling studies were undertaken to compare the predicted binding mode geometries with the mutagenesis data. Using a CHARMM-based molecular receptor docking approach, the lowest energy binding modes of DFPQ and structurally related derivatives were determined using an unbiased conformational search and the receptor conformation from the reference crystal structure, here preferred because it illustrates the β2AR bound to a quinazoline-related NAM (25).

The consensus binding mode geometry for the series of derivatives is shown in Fig. 6 C and D, where the binding site is formed between TM3, TM4, and ICL2. In the model, carbons 5 to 8 of the fused quinazoline ring form hydrophobic contacts with TM4, notably with the side chain of M156 as shown in Fig. 7A. The 4-amino cyclohexyl substituent of DFPQ forms hydrophobic contacts with TM3 most notably with V129. The 2-amino phenyl substituent forms primarily hydrophobic interactions involving TM3 where the para-fluoro group binds in proximity to the hydrophobic side chains of V210 and P211. One of the most important protein–ligand interactions observed in the consensus binding mode is that DFPQ and derivatives form an electrostatic interaction between the quinazoline 2-amino group and the carboxylic acid side chain of E122 on TM3. This structural feature of the model is supported by the mutagenesis data, as the E122W mutant shows the largest effect followed by V129L and M156T (Fig. 7 B–D). The E122W point mutant structurally abrogates the electrostatic interaction and the pharmacophore position for the 2-amino aromatic substituent. This key electrostatic interaction between the 2-amino and E122 is also corroborated by experimental structure–activity relationship data in that a 2N-methyl derivative of DFPQ, which would abrogate this electrostatic interaction with the side chain of E122, is found to exhibit minimal NAM activity (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 7.

Model of NAM interaction and effect of β2AR mutation on NAM-mediated inhibition of β-arrestin recruitment. (A) Best molecular model of DFPQ showing key residue contacts in the β2AR identified by mutagenesis. The all-atom consensus model of DFPQ is shown in gray. The β2AR residue side chains are shown for the three mutations E122W, V129L, and M156T with the strongest effects on NAM activity. Concentration–activity curves for inhibition of ISO-induced β-arrestin recruitment by DFPQ, AP-7-168, and AP-7-203 at the β1AR and β2AR were compared with mutants of residues E122 (B); V129 (C) and M156 (D) of the β2AR. Data are normalized to 1 μM ISO and are the mean % ± SEM, n = 3.

To better understand the high specificity of the NAMs for the β2AR vs. the β1AR, we made several point mutants where the β2AR residue was replaced by the corresponding residue from the β1AR. In these studies, the V129L and M156T substitutions had the largest effect on binding, while other substitutions including C125V in TM3, F133L in ICL2, and V152G, I153L, L155C, and Q170L in TM4 had no significant effect (SI Appendix, Figs. S7–S9 and Table S3). In addition, alanine substitution of V126 in TM3 also had no significant effect on NAM binding. Thus, V129 and M156 in the β2AR play a significant role in mediating the receptor subtype specificity of DFPQ.

Of note, while the responses for the E122W and V129L mutations are nearly identical for the derivatives, there is an obvious structure-based difference in response for the M156T mutant (Fig. 7 B–D). The docking model provides good agreement with these observations from mutagenesis as the predicted protein-ligand interactions involving E122W and V129L are identical, as there are no corresponding changes in compound structure at the 2-amino or 4-amino substituents. On the other hand, the M156 side chain forms important hydrophobic contacts with C8 and C7 of the quinazoline ring and is in close proximity with changes in compound structure for the series of C-6 substituents (H), (Cl), (Br), and (CF3) (Fig. 5A). As the C-6 substituent (CF3) for AP-7-203 forms a larger number of hydrophobic contacts with the hydrophobic side chain of M156, the model rationalizes how the M156T mutation may result in a greater loss of NAM activity for AP-7-203 (CF3) compared to Br or H substituents. The hydrophobic environment of the 2-amino aromatic substituent also rationalizes SAR data for large bulky or hydrophilic substitutions at the para or meta positions. Similarly, the hydrophobic environment of the 4-amino cyclohexyl substituent had important hydrophobic contacts with V129 of TM3, and numerous R-group substitutions at this 4-amino group were also found to strongly affect signaling bias, where the cyclohexyl substituent results in the greatest NAM activity (SI Appendix, Table S1). Similar to the chimera studies, we also tested the ability of E122W, V129L, and M156T to recruit β-arrestin upon stimulation with ISO and compared these to WT β2AR. V129L and M156T mutations did not affect efficacy or potency while E122W showed a minimal decrease in efficacy and potency compared to WT β2AR (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 and Table S4).

In summary, our collective mutagenesis, molecular modeling, and SAR studies suggest that DFPQ interacts with an allosteric binding site formed between TM3 and TM4 where three mutations with the strongest responses (E122W, V129L, and M156T) help to define the binding site and receptor subtype specificity.

Discussion

It is now understood that simple on/off models of receptor activation do not capture the full complement of GPCR signal transduction. As a result, single endpoint measurement in drug discovery efforts for GPCR-targeted therapeutics necessarily excludes information about receptor signaling or regulation that may be relevant to side-effect profiles for a receptor ligand (26). A single GPCR may couple to multiple G proteins, interact with multiple kinases and arrestins, and have other binding partners that modulate signaling and/or regulate receptor expression (27). A therapeutic effect may be downstream of a measured endpoint, while harmful side effects may be downstream of other signaling events or protein-protein interactions (28). Interactions with downstream transducers/effectors of GPCR signaling are coupled to conformational changes in the receptor (29–36), and experimental techniques such as NMR spectroscopy (37) and hydrogen deuterium exchange in aqueous solution (38) have shown that GPCRs constantly explore conformational space. The concept of biased signaling suggests that a receptor can be stabilized in a conformation that selectively promotes receptor activation toward specific downstream effectors or one that prevents subsequent interactions with regulatory proteins. Thorough profiling of receptor signaling with respect to physiological response provides an avenue toward identifying ligands that promote therapeutic responses and minimize interactions with effectors that promote harmful side effects. The potential value of this approach to discovery has been previously explored for several GPCRs including μ-opioid, cannabinoid, and dopamine receptors (39–41).

In the work described here, we examine β2AR-mediated Gs activation, GRK phosphorylation, and β-arrestin interaction. Studies from our lab and others have shown that cAMP production through Gs is the primary mediator of ASM relaxation while GRK phosphorylation and β-arrestin recruitment promote the desensitization of response to β-agonists and the subsequent internalization of the β2AR (4). β-arrestins have also been implicated in eliciting an inflammatory response in the airway (42). For these reasons, molecules that bias β2AR signaling toward Gs without promoting β-arrestin recruitment would hold potential clinical utility for reversing airway constriction in asthma attacks without the side effects currently observed for balanced β-agonists. The effects of test compounds on cAMP production and β-arrestin interaction in the presence of the balanced agonist ISO led to the identification of DFPQ, a potent and selective β-arrestin-biased NAM for the β2AR. We found that in the presence of ISO, DFPQ was able to antagonize GRK-mediated phosphorylation and β-arrestin interaction with the β2AR without inhibiting cAMP production. Moreover, when examined in functional assays, the effects of DFPQ interaction on the β2AR demonstrated the hallmarks of allostery. Mutagenesis studies and molecular modeling suggest that DFPQ interacts with a domain of the β2AR that is topologically distinct from the orthosteric binding site.

In our studies, we have found a high degree of selectivity of DFPQ to inhibit β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR compared with the β1AR. This selectivity is ~40-fold for DFPQ and over 1,000-fold for the 6-bromo and 6-trifluoromethyl quinazoline derivatives of DFPQ (Fig. 6). Use of β2AR/β1AR chimeras demonstrates that this specificity is primarily mediated by residues in TM3, TM4, and ICL2, while molecular modeling identified a possible allosteric binding pocket where DFPQ interacts with the β2AR (Fig. 6). To identify specific residues involved in NAM binding, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of the β2AR. This analysis supports a role for residues E122 and V129 in TM3 and M156 in TM4 in DFPQ binding (Fig. 7). Residue E122 is an important driver of receptor deactivation since it interacts with DFPQ and when mutated, abrogates the NAM activity. DFPQ also interacts with residue V129 in TM3 which is adjacent to the DRY motif, a hallmark of GPCR activation (43–45). Indeed, the DRY motif helps to keep the receptor in an inactive conformation by forming a salt bridge with residues in TM6. Therefore, by virtue of interaction with V129, DFPQ may help to stabilize a conformation of the receptor that is not favorable for β-arrestin recruitment while not impacting Gs activation.

Previous studies have identified several allosteric modulators for the β2AR. These include Gs-biased PAMs and NAMs identified using an in silico ligand competitive saturation computational method (46), an unbiased NAM and PAM from screening of DNA-encoded libraries (47–49), and an unbiased NAM from in silico docking and chemical optimization (25). The latter study is particularly relevant to our work and identified the compound AS408 as a NAM for both ISO-mediated cAMP production and β-arrestin recruitment to the β2AR. Molecular dynamics and crystallization studies showed AS408 binds in a pocket created by TM3 and TM5 and interacts with residues E122 in TM3 and V206 and S207 in TM5, a region in close proximity to a conformational hub formed by P211, I121, and F282 that is rearranged upon receptor activation. Interestingly, AS408 is structurally related to DFPQ since both share a quinazoline ring as the main pharmacophore. However, DFPQ and AS408 contain different groups at the 2-amino (R1) and 4-amino (R3) positions of the quinazoline, with DFPQ having a difluorophenyl in place of a phenyl at the R1 position and a cyclohexyl in place of a H at the R3 position (Fig. 5). We have found that the difluorophenyl enhances affinity ~5- to 10-fold while the cyclohexyl is essential for the β-arrestin biased NAM activity of DFPQ (SI Appendix, Table S1). Thus, the absence of bias for AS408 might be due to the lack of a substituent at the 4-amino position on the quinazoline. In addition, AS408 contains a bromine at position 6 of the quinazoline ring and we have found that modification at this position in DFPQ enhances the overall affinity 5- to 10-fold (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Table S1).

The work identifying Gs-biased PAMs is also of interest since these compounds augment β-agonist-induced relaxation of contracted HASM cells and bronchodilation of contracted airway tissue (46). Mutagenesis studies support a role for residues R131 in ICL2, Y219 in TM5, and F282 in TM6 in the PAM function. Screening DNA-encoded libraries identified a β2AR NAM (Cmpd-15) and a PAM (Cmpd-6) that are unbiased for effects on agonist-induced cAMP generation and β-arrestin recruitment. Cmpd-15 binds in an allosteric pocket created by the cytoplasmic regions of TM1, 2, 6, and 7 and sterically blocks Gs and β-arrestin recruitment to the agonist-occupied receptor. Interestingly, while Cmpd-6 is chemically and structurally different from DFPQ, the allosteric binding pocket identified by crystallization is formed by TM3, ICL2, and TM4, similar to the proposed binding pocket of DFPQ. Cmpd-6 stabilizes the α-helical conformation of ICL2, which is a key structural feature of G protein recruitment to the β2AR. By virtue of this structural and functional determinant, Cmpd-6 behaves as a PAM for both G protein and β-arrestin recruitment. In our studies, a β2AR/β1AR chimera that swaps ICL2 showed a significant loss of DFPQ-mediated NAM activity (SI Appendix, Figs. S3–S5), suggesting a possible conformational change of ICL2 induced by DFPQ interaction. This, together with the different chemical structures, might explain the divergence in the pharmacology of DFPQ and Cmpd-6, although both allosteric modulators share closely-related binding pockets. Interestingly, the crystal structure of Cmpd-6 bound to the β2AR revealed that Cmpd-6 is at the interface between the protein receptor and the lipidic membrane. This geometry is also suggested for DFPQ by our molecular modeling and correlates with the high hydrophobicity that both allosteric modulators possess.

β-agonists are effective drugs in the management of asthma but have limitations. Chronic β-agonist use by asthmatics can promote tachyphylaxis including a loss of bronchoprotective effect (50, 51), promote airway hyperresponsiveness (52), worsen asthma control (53), and has historically been associated with major safety concerns (54, 55). In addition, β-arrestins have been shown to be critical in the pathogenesis of asthma (42, 56, 57). Studies utilizing in vivo and ex vivo asthma models of allergic lung inflammation have shown that β-arrestin2 knockout is protective from mucin production, airway hyperresponsiveness, and immune cell infiltration. Thus, compounds that inhibit β-arrestin interaction with the β2AR like DFPQ could hold a clinical advantage by mitigating deleterious arrestin-dependent effects. In this study, we demonstrate that DFPQ is able to inhibit agonist-induced internalization of the β2AR and that DFPQ is protective against agonist-induced desensitization in both in vitro cell and ex vivo tissue models. Furthermore, DFPQ enhances the PKA-dependent inhibition of HASM migration in primary cells, which may address airway remodeling in the pathogenesis of asthma. For these reasons, DFPQ could be an attractive lead molecule that can be further developed toward an improved class of asthma therapeutics. Additionally, DFPQ can be used to better describe the molecular mechanisms of biased signaling through the β2AR and the diverse signaling profiles propagated by β2AR ligands. Indeed, crystallization of the receptor bound to DFPQ may give structural insights about the molecular mechanisms of the allosteric action of the molecule as well as its biased behaviors, paving the way to fine-tuning β2AR pharmacology.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

GloSensor™ cells (Promega) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 200 µg/mL Hygromycin B. PathHunter™ ADRB2 cells (DiscoveRx) were maintained in Ham’s F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 300 µg/mL G418 and 100 µg/mL blasticidin. HEK 293 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 12.5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2. HEK 293 cells stably overexpressing β2AR included 250 μg/mL G418. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

High-Throughput Assay for cAMP Production.

First, 6,250 GloSensor™ cells in 25 µL of culture medium were plated per well in sterile, white, tissue-culture-treated 384-well plates and allowed to attach overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Then, 0.25 µL of orthogonally compressed libraries from the Lankenau Chemical Genomics Center (LCGC) were transferred into plates using a high-density replication tool and allowed to incubate with cells for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were removed from the incubator, 25 µL of CO2-independent medium (Thermo-Fisher) plus 10% FBS and 4% GloSensor™ cAMP reagent (Promega) was added to each well and plates were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature for 2 h. ISO was added to each well to a final concentration of 1 µM, and luminescence was determined in kinetic mode at room temperature (23 to 25 °C) on a PolarStar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech). Response was analyzed relative to forskolin (7 µM) and alprenolol (1 µM) as positive and negative controls, respectively.

High-Throughput Assay for β-Arrestin Recruitment to β2AR.

First, 5,000 PathHunter™ ADRB2 cells in 20 µL of cell plating medium (DiscoveRx) were plated per well in sterile, white, tissue-culture treated 384-well plates and allowed to attach overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Then, 0.25 µL of orthogonally compressed libraries from the LCGC were transferred into plates using a high-density replication tool and allowed to incubate with cells for 1 h at 37 °C. ISO (5 µL of 5 µM stock in cell plating medium) was added to each well to a final concentration of 1 µM, and cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Plates were removed from the incubator, and 12.5 µL of PathHunter™ detection solution was added to each well. Plates were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. Luminescence was determined at room temperature (23 to 25 °C) on a PolarStar Optima plate reader. Response was analyzed relative to vehicle (DMSO) and alprenolol (1 µM) as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Screening Data Analysis and IC50 Determination.

Negative control signal was subtracted from all data and responses were normalized relative to full response (positive control minus negative control). Relative assay bias was calculated from the ratio of normalized cAMP and arrestin recruitment responses. Wells from orthogonally-compressed libraries displaying Gs-bias (NAMs of arrestin recruitment and PAMs of cAMP production, excluding inverse agonists) were deconvoluted to identify compounds for follow-up analysis (58). Candidate compounds were titrated from 10 µM to 10 nM concentration in half-logarithmic steps in GloSensor™ and PathHunter™ assays in order to determine IC50 values for cAMP production and β-arrestin recruitment. Compounds displaying confirmed Gs-bias were progressed to secondary screening.

cAMP Measurement.

HEK 293 cells stably overexpressing β2AR were seeded in poly-L-lysine coated 24-well plates and incubated at 37 °C. Cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min prior to stimulation with indicated concentrations of ISO for 10 min. Cells were then lysed in 0.1 M HCl for 20 min at room temperature. cAMP levels were measured using the Caymen Chemical Cyclic AMP EIA kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of β-Arrestin2 Binding to the β2AR Using BRET.

HEK 293 cells were transfected with pcDNA-β-arrestin2-GFP10 and pcDNA3-β2AR-RlucII, pcDNA3-β1AR-RlucII, or pcDNA3-CXCR4-RlucII using X-tremegene HP9 complexed in serum-free optiMEM. Twenty four h after transfection, cells were replated at 100,000 cells per well in an opaque, poly-L-lysine coated 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Cells were then pretreated with 0.1% DMSO or DFPQ for 30 min followed by the addition of Coelenterazine 400a and agonist stimulation. BRET was measured using a Tecan Infinite F500 microplate reader. BRET ratios were calculated as the light emitted by the GFP10 acceptor divided by the total light emitted by the RLucII donor.

In-Cell β2AR Phosphorylation.

HEK 293 cells stably overexpressing FLAG-β2AR were seeded into poly-L-lysine coated 6-well plates and incubated at 37 °C. Cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO or indicated concentrations of DFPQ for 30 min prior to stimulation with 1 μM ISO for 10 min. Cells were then lysed on ice, scraped, and sonicated. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using rabbit polyclonal anti-FLAG and Protein G agarose beads. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot using a β2AR C-terminal tail or phospho-specific antibody.

In Vitro Kinase Assay.

The effect of DFPQ on GRK5 activity was determined using a radiometric assay. Briefly, purified C-terminally strep-tagged GRK5 (50 nM) was incubated for 10 min at 30 °C with either no substrate (to evaluate GRK5 autophosphorylation), tubulin (0.5 µM) or purified β2AR (0.5 µM) reconstituted into bicelles with PIP2, in a reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 30 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 100 μM [γ32P]ATP (1,000 to 2,000 cpm/pmol), and 1 µM ISO. DFPQ concentration was varied from 0 to 50 μM. Reactions were quenched with SDS sample buffer, and samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue (Sigma-Aldrich), dried, exposed to autoradiography film, and 32P-labeled proteins were excised and counted to determine the amount of phosphate transferred. Reaction rates were normalized to the substrate phosphorylation in the absence of DFPQ.

Receptor Internalization.

HEK 293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were seeded into poly-L-lysine coated 24-well plates and incubated at 37 °C. Cells were pretreated with 0.1% DMSO or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min prior to stimulation with 1 μM ISO for 0 to 60 min. Cells were then fixed on ice and processed for cell surface ELISA with polyclonal anti-FLAG primary antibody, anti-rabbit HRP secondary antibody, and incubation with [2,2′-Azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)-diammonium salt] (ABTS). Absorbance was then measured on a plate reader at 405 nm.

Functional Desensitization in HEK 293 Cells.

HEK 293 cells were seeded in poly-L-lysine coated 24-well plates and incubated at 37 °C. Cells were incubated with 0.1% DMSO or 10 μM DFPQ for 30 min prior to stimulation with 1 μM ISO for 30 min. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with various concentrations of ISO for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were then lysed in 0.1 M HCl for 20 min at room temperature and cAMP levels were measured using the Caymen Chemical Cyclic AMP EIA kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

MTC.

Changes in cell stiffness were measured in isolated HASM cells using forced motions of functionalized beads anchored to the cytoskeleton through cell surface integrin receptors, as previously described (22). An increase or decrease in stiffness is considered an index of single-cell contraction and relaxation, respectively. For these studies, serum-deprived, post-confluent cultured HASM cells were plated at 30,000 cells/cm2 on plastic wells (96-well Removawell, Immulon II, Dynetech Laboratories Inc, Chantilly, VA, USA) coated with type I collagen (VitroCol; Advanced BioMatrix, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 500 ng/cm2, and maintained in serum-free media for 24 h at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. To evaluate functional desensitization of the β2 AR, in-real time, ISO-induced stiffness changes were monitored continuously for 30 min in the presence or absence of DFPQ. HASM cells were pretreated with or without 1 μM DFPQ for 30 min. Following 30 min preincubation, cell stiffness was measured for 60 s, and after ISO addition (10 μM, t = 60 s), stiffness was continuously measured for the next 1740 s (data were collected at every 1.3 s intervals). Cell stiffness is expressed as Pascal per nanometer (Pa/nm) and, for each cell, stiffness was normalized to its baseline stiffness prior to ISO stimulation.

Measurement of Airway Contractility.

For ex vivo evaluation, lungs were harvested from mouse strain C57BL/6 (10 to 16 wk old). Tracheotomy was performed for cannulation to gain access to lungs. The thoracic cavity was exposed to detach lung tissue from the diaphragm to allow for space for lungs to expand. Warm molten low melting point agarose (2 to 4% w/v, ~ 1 mL total volume) was injected into murine lungs through the cannula using a 1 mL syringe. Lungs were monitored for appropriate inflation. Following this, ~ 0.2 mL of air was injected into the expanded lungs, and mice were placed at 4 °C for 30 to 45 min to allow for agarose to solidify. At the end of incubation, the lung tissue was excised and the left lung lobe was processed for generation of lung tissue slices using an OTS-5000 tissue slicer. On day 1, airway tissue was contracted with 1 μM methacholine and then relaxed with 1 μM ISO ± 1 μM DFPQ overnight. On day 2, tissue was washed, recontracted with methacholine, and then rechallenged with ISO. The luminal airway area was monitored by light microscopy over the indicated time course and images were collected at various time points indicated in the results. Images were analyzed post hoc using ImageJ.

Molecular Modeling.

Molecular docking was performed using the program CHARMM for an all-atom force field potential energy description of the protein–ligand complexes (59, 60). The lowest energy binding modes of DFPQ and related derivatives were determined using an unbiased conformational search and the receptor conformation from a reference crystal structure (25) that includes the β2AR bound to a quinazoline-related NAM. Flexible-receptor docking for DFPQ and the DFPQ derivatives were performed while the receptor was bound to the orthosteric agonist BI-167107 or ISO using protocols outlined previously for docking GPCR allosteric modulators (61).

Pharmacological Screening of β2AR Mutants.

HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with β1AR-Rluc, β2AR-Rluc, or mutant β2AR-Rluc and β-arrestin 2-GFP in a 96-well plate using Metafectene Pro (Biontex, München, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Forty-eight hours after transfection, media were removed, and cells were incubated with increasing concentrations (30 nM to 100 μM) of NAM for 30 min, followed by addition of 1 μM ISO in the presence of 5 μM DBC for 20 min. Signals at 395 nm and 530 nm were recorded in an Infinite F500 plate reader. Results from concentration/activity curves are shown as mean ± SEM from six independent experiments. For normalization, we first subtracted the basal signal (wells stimulated with PBS in the absence of ligand) from each stimulated well, and the values of all replicates were then divided by the mean of ISO-alone induced responses and multiplied by 100 for any given read-out.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis.

All statistical analyses were produced using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, unless otherwise stated in the figure legend. To obtain values for Imax (or Emax) and IC50 (or EC50), data from SI Appendix, Figs. S3–S10, were fitted using the function log (inhibitor) versus response (three parameters) of the nonlinear curve fitting in GraphPad Prism. In those cases where the model reported an “ambiguous” result due to poor curve fitting and large uncertainty, values for Imax and IC50 were reported as “not determined.” The statistical comparison shown in SI Appendix, Tables S2–S4 was assessed by the t test with Welch's correction, and P values were considered significant when <0.05. For MTC studies, we applied the linear mixed effect model to control for random effects from repeated measurements in the same deidentified nonasthma donor lung-derived HASM cells, using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). To satisfy the normal distribution assumptions associated with the linear mixed effect model, stiffness data were converted to a log scale before analyses. Unless otherwise noted, stiffness data are presented as Estimated Mean ± SE, and two-sided P values <0.05 were considered to indicate significance at every collected data (t, 0 to 1,800 s at 1.3 s intervals).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably overexpressing the β2AR were a gift from Dr. Mark von Zastrow, pcDNA-β-arrestin2-GFP10 and pcDNA3-β2AR-RlucII were provided by Dr. Michel Bouvier, purified β2AR was provided by Dr. Brian Kobilka, purified Gs was provided by Dr. Greg Tall, β2AR/β1AR chimeras were provided by Drs. Jillian Baker and Stephen Hill, and some HASM cells were provided by Dr. Reynold Panettieri. This research was supported by NIH awards R35 GM122541 (J.L.B.), R01 HL136219 (J.L.B., C.P.S.), P01 HL114471 (J.L.B., S.S.A., C.P.S., R.S.A., R.B.P.), R01 HL58506 (R.B.P.), R01 AI161296 (R.B.P., J.L.B.), T32 GM100836 (M.I.), F31 HL139104 (M.I.), and T32 ES007148 (Jordan Lee).

Author contributions

M.I., F.D.P., N.H., K.E.K., D.L., P.A.N.R., S.S.A., J.M.S., R.B.P., R.S.A., C.P.S., and J.L.B. designed research; M.I., F.D.P., N.H., K.E.K., D.L., P.A.N.R., L.A.S., K.Z.R., A.P.N., Justin Lee, Jordan Lee, G.C., and R.S.A. performed research; P.A.N.R., P.S.D., M.R., and J.M.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; M.I., F.D.P., N.H., K.E.K., A.P.N., S.S.A., R.B.P., R.S.A., C.P.S., and J.L.B. analyzed data; and M.I., F.D.P., N.H., K.E.K., D.L., P.A.N.R., M.R., S.S.A., J.M.S., R.B.P., R.S.A., C.P.S., and J.L.B. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

A patent on the reported compounds was submitted by several of the authors (M.I., N.H., J.M.S., R.S.A., C.P.S., and J.L.B.) in 2022.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.D.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Additional primary data sources supporting the study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Klein Herenbrink C., et al. , The role of kinetic context in apparent biased agonism at GPCRs. Nat. Commun. 7, 10842 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quirce S., Bobolea I., Barranco P., Emerging drugs for asthma. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 17, 219–237 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christopoulos A., Advances in G protein-coupled receptor allostery: From function to structure. Mol. Pharmacol. 86, 463–478 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr R., et al. , Development and characterization of pepducins as Gs-biased allosteric agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 35668–35684 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande D. A., Penn R. B., Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signaling in asthma. Cell. Signal. 18, 2105–2120 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazzola M., Page C. P., Rogliani P., M. G., Matera, β2-agonist therapy in lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187, 690–696 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker J. K. L., et al. , β-Arrestin-2 regulates the development of allergic asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 566–574 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thanawala V. J., et al. , β-Blockers have differential effects on the murine asthma phenotype. British J. Pharmacol. 172, 4833–4846 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forkuo G. S., et al. , Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors attenuate the asthma phenotype produced by β2-adrenoceptor agonists in phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-knockout mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 55, 234–242 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wootten D., Christopoulos A., Sexton P. M., Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: Implications for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 630–644 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dror R. O., et al. , Activation mechanism of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18684–18689 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Pascali F., et al. , β2 -Adrenoceptor agonist profiling reveals biased signalling phenotypes for the β2 -adrenoceptor with possible implications for the treatment of asthma. Br. J. Pharmacol. 179, 4692–4708 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D., et al. , Identification and characterization of an atypical Gαs-biased β 2 AR agonist that fails to evoke airway smooth muscle cell tachyphylaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2026668118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan S. J., et al. , β-agonist-mediated relaxation of airway smooth muscle is protein kinase A-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23065–23074 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncharova E. A., et al. , β 2-adrenergic receptor agonists modulate human airway smooth muscle cell migration via vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein. Am. J. Res. Cell Mol. Biol. 46, 48–54 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bologna Z., Teoh J., Bayoumi A. S., Tang Y., Kim I., Biased G protein-coupled receptor signaling: New player in modulating physiology and pathology. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 25, 12–25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters M. C., van Westen G. J. P., Li Q., IJzerman A. P., Importance of the extracellular loops in G protein-coupled receptors for ligand recognition and receptor activation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32, 35–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi M., et al. , G protein–coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) orchestrate biased agonism at the β2 -adrenergic receptor. Sci. Signal. 11, eaar7084(2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobles K. N., et al. , Distinct phosphorylation sites on the β2-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of β-arrestin. Sci. Signal. 4, ra51 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohout T. A., Lin F. S., Perry S. J., Conner D. A., Lefkowitz R. J., Beta-Arrestin 1 and 2 differentially regulate heptahelical receptor signaling and trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1601–1606 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddox L., Schwartz D. A., The pathophysiology of asthma. Annu. Rev. Med. 53, 477–498 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An S. S., et al. , An inflammation-independent contraction mechanophenotype of airway smooth muscle in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 294–297.e4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salter B., Pray C., Radford K., Martin J. G., Nair P., Regulation of human airway smooth muscle cell migration and relevance to asthma. Respir. Res. 18, 1–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakash Y. S., et al. , An official American thoracic society research statement: Current challenges facing research and therapeutic advances in airway remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195, e4–e19 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., et al. , An allosteric modulator binds to a conformational hub in the β2 adrenergic receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 749–755 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenakin T., Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 336, 296–302 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokolina K., et al. , Systematic protein-protein interaction mapping for clinically relevant human GPCRs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13, 918 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenakin T., The effective application of biased signaling to new drug discovery. Mol. Pharmacol. 88, 1055–1061 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai Q., Zhang Y., Ban Y., Liu H., Yao X., Computational study on the different ligands induced conformation change of β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. PLoS One 8, e68138 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heifetz A., et al. , Toward an understanding of agonist binding to human Orexin-1 and Orexin-2 receptors with G-protein-coupled receptor modeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 52, 8246–8260 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang X., et al. , Molecular dynamics simulations on SDF-1α: Binding with CXCR4 receptor. Biophys. J. 84, 171–184 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nygaard R., et al. , The dynamic process of β2-adrenergic receptor activation. Cell 152, 532–542 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tautermann C. S., Seeliger D., Kriegl J. M., What can we learn from molecular dynamics simulations for GPCR drug design? Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 111–121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tikhonova I. G., Selvam B., Ivetac A., Wereszczynski J., McCammon J. A., Simulations of biased agonists in the β2 adrenergic receptor with accelerated molecular dynamics. Biochemistry 52, 5593–5603 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilar S., Karpiak J., Berk B., Costanzi S., In silico analysis of the binding of agonists and blockers to the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 29, 809–817 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss D. R., et al. , Conformation guides molecular efficacy in docking screens of activated β-2 adrenergic G protein coupled receptor. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1018–1026 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J. J., Horst R., Katritch V., Stevens R. C., Wüthrich K., Biased signaling pathways in β2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science 335, 1106–1110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West G. M., et al. , Ligand-dependent perturbation of the conformational ensemble for the GPCR β2 adrenergic receptor revealed by HDX. Structure. 19, 1424–1432 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy D. P., et al. , The second extracellular loop of the adenosine A1 receptor mediates activity of allosteric enhancers. Mol. Pharmacol. 85, 301–309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morales P., Goya P., Jagerovic N., Emerging strategies targeting CB2 cannabinoid receptor: Biased agonism and allosterism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 157, 8–17 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urs N. M., Peterson S. M., Caron M. G., New concepts in dopamine D2 receptor biased signaling and implications for schizophrenia therapy. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 78–85 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker J. K. L., DeFea K. A., Role for β-arrestin in mediating paradoxical β2AR and PAR2 signaling in asthma. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 16, 142–147 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ballesteros J. A., et al. , Activation of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor involves disruption of an ionic lock between the cytoplasmic ends of transmembrane segments 3 and 6. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29171–29177 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rovati G. E., Capra V., Neubig R. R., The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: Beyond the ground state. Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 959–964 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valentin-Hansen L., et al. , The arginine of the DRY motif in transmembrane segment III functions as a balancing micro-switch in the activation of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31973–31982 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah S. D., et al. , In silico identification of a β2-adrenoceptor allosteric site that selectively augments canonical β2AR-Gs signaling and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2214024119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahn S., et al. , Allosteric “beta-blocker” isolated from a DNA-encoded small molecule library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1708–1713 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn S., et al. , Small-molecule positive allosteric modulators of the β2-adrenoceptor isolated from DNA-encoded libraries. Mol. Pharmacol. 94, 850–861 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X., et al. , Mechanism of β2AR regulation by an intracellular positive allosteric modulator. Science 364, 1283–1287 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhagat R., Kalra S., Swystun V. A., Cockcroft D. W., Rapid onset of tolerance to the bronchoprotective effect of salmeterol. Chest 108, 1235–1239 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newnham D. M., Grove A., McDevitt D. G., Lipworth B. J., Subsensitivity of bronchodilator and systemic β2 adrenoceptor responses after regular twice daily treatment with eformoterol dry powder in asthmatic patients. Thorax 50, 497–504 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor D. R., The β-agonist saga and its clinical relevance: On and on it goes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179, 976–978 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salpeter S. R., Buckley N. S., Ormiston T. M., Salpeter E. E., Meta-analysis: Effect of long-acting β-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths. Ann. Intern. Med. 144, 904–912 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sears M. R., Adverse effects of β-agonists. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110, S322–S328 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donohue J. F., Safety and efficacy of β agonists. Respir. Care 53, 618–622 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hollingsworth J. W., et al. , Both hematopoietic-derived and non-hematopoietic-derived β-arrestin-2 regulates murine allergic airway disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 43, 269–275 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thanawala V. J., et al. , β2-Adrenoceptor agonists are required for development of the asthma phenotype in a murine model. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 48, 220–229 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donover P. S., et al. , New informatics and automated infrastructure to accelerate new leads discovery by high throughput screening (HTS). Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 16, 180–188 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu G., Robertson D. H., Brooks C. L., Vieth M., Detailed analysis of grid-based molecular docking: A case study of CDOCKER–A CHARMm-based MD docking algorithm. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1549–1562 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armen R. S., Chen J., Brooks C. L., An evaluation of explicit receptor flexibility in molecular docking using molecular dynamics and torsion angle molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2909–2923 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sakkal L. A., Rajkowski K. Z., Armen R. S., Prediction of consensus binding mode geometries for related chemical series of positive allosteric modulators of adenosine and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Comput. Chem. 38, 1209–1228 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Additional primary data sources supporting the study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.