Abstract

Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are chronic pathologies with a high incidence worldwide. They share some pathological mechanisms, including hyperinsulinemia, the production and release of hormones, and hyperglycemia. The above, over time, affects other systems of the human body by causing tissue hypoxia, low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress, which lay the pathophysiological groundwork for cancer. The leading causes of death globally are T2DM and cancer. Other main alterations of this pathological triad include the accumulation of advanced glycation end products and the release of endogenous alarmins due to cell death (i.e., damage-associated molecular patterns) such as the intracellular proteins high-mobility group box protein 1 and protein S100 that bind to the receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE) - a multiligand receptor involved in inflammatory and metabolic and neoplastic processes. This review analyzes the latest advanced reports on the role of RAGE in the development of obesity, T2DM, and cancer, with an aim to understand the intracellular signaling mechanisms linked with cancer initiation. This review also explores inflammation, oxidative stress, hypoxia, cellular senescence, RAGE ligands, tumor microenvironment changes, and the “cancer hallmarks” of the leading tumors associated with T2DM. The assimilation of this information could aid in the development of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to lower the morbidity and mortality associated with these diseases.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes; Cancer; Obesity; Advanced glycation end product receptor; Receptor for advanced glycation end products; Glycation end products, advanced

Core Tip: The receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE) is involved in every stage of the pathophysiological pathways that lead to the progression of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. This article provides a focused discussion on the stages of obesity leading to the development of metabolic diseases and provides a broad overview of the contribution of RAGE to the development of diabetes and cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity, diabetes, and cancer are chronic diseases, the prevalences of which have all increased in parallel, and are leading causes of death worldwide[1]. However, the forecasts for these health problems are not encouraging. For example, the prevalence of diabetes is estimated to increase by 2045, specifically in middle-income countries to 21.1%, in high-income countries to 12.2%, and in low-income countries to 11.9%. Meanwhile, the incidence of malignant neoplasms in people under 50 years of age is also rising[2,3].

Although esophageal adenocarcinoma has a direct link to obesity, and pancreatic cancer can debut with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), there is an evident connection between the three disorders. Moreover, there is confusion about their shared lifestyle risk factors, including sedentariness and consumption of highly processed foods[4-6]. Regarding the common pathological mechanisms of obesity, T2DM, and cancer, expansion of adipose tissue (AT) results in the production of excess estrogen, adipokines, and inflammatory molecules that can lead to systemic or localized low-grade inflammation. In addition, omental and visceral adiposity is related to hyperinsulinemia and increased levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)[7]. The metabolic abnormalities and lipo-glucotoxicity associated with insulin resistance and T2DM also cause an increase in inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. As a result, neoplastic processes can be triggered by T2DM and, likewise, obesity[8].

The pathogenic mechanisms that link obesity, T2DM, and cancer are complex and multifactorial. Because there is a notion of progression from obesity to T2DM towards cancer, our motivation for this review was to provide a detailed and up-to-date discussion on these mechanisms in the context of a single molecule known as the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). As such, this narrative review incorporates the conceptual framework and reports on findings extracted from two literature databases, the Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/) and PubMed, to provide a reflective discussion of RAGE’s implications for the progression of obesity to T2DM and from T2DM to cancer.

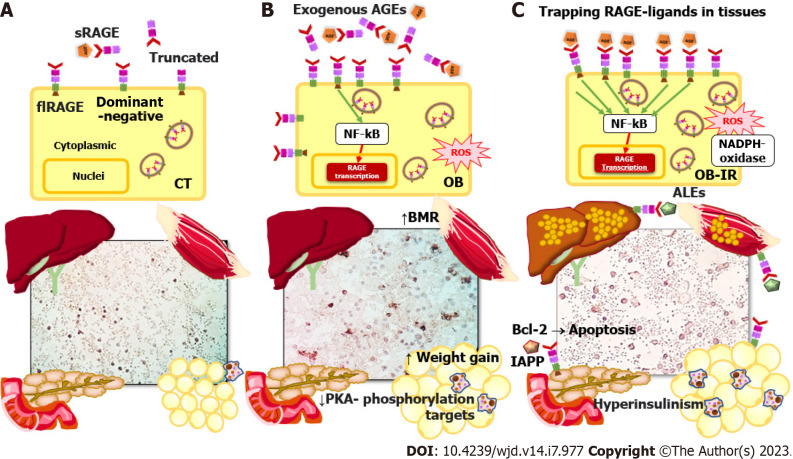

RAGE is an immunoglobulin superfamily member and a type I pattern-recognition receptor. It is also a sensitive environmental sensor with several endogenous and external ligands. Furthermore, it is a widely expressed modulator of inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways with vast metabolic implications[9]. RAGE isoforms include soluble forms (sRAGE) that act as decoy receptors, sequester circulating ligands, and attenuate membrane RAGE signaling[10]. Soluble forms derived from membrane-localized RAGE are released into the circulation by proteolytic cleavage (cRAGE), and endogenously secreted RAGE (esRAGE) is formed by alternative splicing. In addition to the sRAGE isoforms and the full-length membrane receptor (flRAGE) - the only isoform that participates in signal transduction, there are also the dominant-negative isoforms lacking the cytoplasmic tail and the truncated isoform lacking the V-type immunoglobulin domain[11] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Receptor for advanced glycation products signaling and molecular mechanisms involved in progression from obesity to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE)-ligand signaling in healthy control subjects, obese individuals (OB), and OB with insulin resistance is illustrated. A: Full-length, total soluble, dominant-negative (intracytoplasmic, lacking domain), and truncated (lacking a V-terminal) RAGE isoforms; B: Basal metabolic rate increase in muscle, decreased phosphorylation targets of protein kinase A, and weight gain (adipose tissue) are findings in obesity related to increased RAGE isoforms and ligands; C: The mechanism trapping RAGE-ligand in tissues involves translocation of cytoplasmic RAGE to the membrane, inflammation (nuclear factor-kappa B), and oxidative stress (NADPH-oxidase) in peripheral mononuclear blood cells, liver, muscle, pancreas, and adipose tissue. The B cell lymphoma-2 proto-oncogene mediates RAGE apoptosis signaling in pancreatic beta cells and leads to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Advanced glycosylation end products, advanced lipoperoxidation end products, and islet amyloid polypeptide (also known as amyloid) are RAGE ligands. RAGE: Receptor for advanced glycation products; CT: Control subjects; OB: Obese individuals; OB-IR: Obese individuals with insulin resistance; flRAGE: Full-length receptor for advanced glycation products; sRAGE: Soluble receptor for advanced glycation products; BMR: Basal metabolic rate; PKA: Protein kinase A; NF-kB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; PBMCs: Peripheral mononuclear blood cells; Bcl-2: B cell lymphoma-2; AGEs: Advanced glycosylation end products; ALEs: Advanced lipoperoxidation end products; IAPP: Islet amyloid polypeptide.

OBESITY AND T2DM

Initially, the function of RAGE was established in the context of chronic disease, specifically T2DM and its complications, in which persistent hyperglycemia triggers inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial damage[12,13]. However, there is more evidence that an increase in RAGE ligands is present in the early stages of metabolic dysfunction in obesity[14,15].

RAGE ligands

The most recognized ligands of RAGE are the advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) and lipid oxidation adducts (ALEs). These are taken in from diet or produced by endogenous metabolism through non-enzymatic and spontaneous Maillard-type reactions in which proteins and nucleic acids react with carbohydrates, lipids, or their intermediate metabolites[16,17].

Foods cooked by roasting, grilling, frying, drying, heating, or adding artificial colorants, salt, oil, or sugar are often present in ultra-processed foods to make them suitable to store[6]. In addition to those above, an increase in the diet’s caloric, fat, and glycemic indices leads to a significant rise in the levels of circulating AGEs. Some exogenous-derived food AGEs are Nδ-(5-hydro-5-methil-4-imidazolon-2-il)-ornithina (MG-H1), Nε-carboxyethyl lysine (CEL), and Nε-carboxymethyl lysine (CML), in addition to the precursor methylglyoxal[18-20].

The problem gets worse when an individual also consumes other substances like alcohol and tobacco. Cigarettes are a source of AGEs, and smoking them causes RAGE expression to rise, which is linked to airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and causes sRAGE to decrease in smoke-induced cardiovascular disease[21,22]. The increase in mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) caused by the RAGE pathway in smoke-exposed skeletal muscle is one of the hypothesized mechanisms in this regard[23]. In vitro, oral squamous cell carcinoma treated with cigarette smoke extract showed an increase in RAGE with a link to a rise in invasive ability[24]. Additionally, RAGE is elevated in alcoholic liver disease, affecting blood triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and alanine transaminase levels. RAGE also contributes to the accumulation of lipid droplets in the liver and modifies the expression of SREBP1, a transcription factor involved in lipid homeostasis[25].

Serum AGE accumulation from the diet can lead to cross-link formation that irreversibly changes endogenous proteins independent of glycemic control. Birukov et al[26] found that in people with prediabetes and T2DM, there were significant variations in the levels of AGEs in the skin. Additionally, AGE measurements in that study were related to factors such as waist circumference, glycated hemoglobin (commonly known as hemoglobin A1c) levels, C-reactive protein levels, and vascular stiffness. Further research is required to determine the sensitivity and accuracy of testing AGE accumulation and its relationship to disease status.

In addition to the above, other natural substances such as catechols, myeloperoxidase systems, and the polyol pathway are implicated in producing endogenous AGEs in obesity and states of insulin resistance[27,28]. Likewise, the link between AGEs in obesity and T2DM is the accumulation of lipids and their oxidized products. Thus, the accumulation of free fatty acids and subsequent ALE production aids in the progression of obesity to T2DM[29,30]. Oxidative stress promotes the lipoperoxidation of membranes and the production of metabolites such as 4-hydroxyl-trans2-nonenal, acrolein, aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA), and ketoaldehydes such as 4-oxo-trans-2-nonenal. These may start with obesity and insulin resistance and can result in the creation of endogenous ALEs like MDA-Lys[17,31,32]. Further studies are required on the mechanism by which the progression from obesity to T2DM is affected by the ALEs-RAGE interaction and their aldehyde precursors produced by lipid peroxidation.

In this regard, in obese subjects, RAGE induces migration of macrophages because of the rise in lipid peroxidation and the accumulation of ALEs in renal tissue that leads to kidney injury[33]. Patients with T2DM have high levels of ALE (MDA-Lys), which induces the activation and adherence of monocytes to endothelial cells by increasing the expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and activating the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) pathway causing inflammation[34]. Recent comprehensive reviews have addressed endogenous and exogenous AGE and ALE formation in obesity[17], T2DM, and cancer[28,35,36].

There is consistent evidence regarding how ultra-processed foods, ALEs, and AGEs disrupt the microbiota causing dysbiosis, the subsequent translocation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and endotoxemia[37,38]. Likewise, dysbiosis is related to obesity, low-grade inflammation, and the progression of insulin resistance and T2DM[39]. However, few publications implicate RAGE as an LPS ligand to mediate inflammatory processes in obesity[40]. This issue needs further investigation, and an exciting future research opportunity may focus on T2DM prevention with respect to the relationship between AGEs/ALEs, RAGE, and dysbiosis.

According to the most recent definitions, chronic low-grade inflammation begins when molecules and metabolites, resulting from altered cell function and structure and foods, stimulate receptors and activate their signaling cascades with dysregulated energy homeostasis. To this end, RAGE mediates danger signals to the body and metabolic stress characteristic of innate immune systems, since RAGE detects ligands from microbes via exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as LPS. Furthermore, damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) ligands are derived from endogenous sources such as high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), S100/calgranulins, amyloid deposits like β-amyloid peptide, and macrophage-1 antigen[41].

AGE and ALE metabolites can be considered DAMPs that are not derived from exogenous sources such as the diet, and the term “metabolism-associated molecular pattern” is proposed for these specific ligands. It is essential to differentiate between them and demonstrate that both endogenous and external components are involved in these responses[42]. An opportunity for experts in the field is to reach a consensus with respect to the classification of all exogenous and endogenous ligands for pattern-recognition receptors.

RAGE-trapping ligands

Several investigations in human subjects have found an association between obesity and low circulating AGE levels[43]. Complex detoxification and clearance kinetics of AGEs could lead to inconsistent study results. The concept of entrapment of AGE in tissues proposes that AGEs are no longer circulating because they are trapped in tissues as metabolic risks increase in individuals[44-46] (Figure 1C).

For instance, high RAGE expression in AT is implicated in its dysfunction and is evidence of a link between RAGE signaling and the progression of obesity to associated metabolic disorder. A high level of RAGE expression in human epicardial AT is related to its thickening, low glucose transporter type 4 expression, and high HMGB1 expression[47]. In this context, visceral omental AT and fetal membrane samples from women with gestational diabetes revealed higher levels of RAGE and the HMGB1 ligand, respectively[48]. RAGE signaling pathway proteins were also found to be expressed differently in omental and subcutaneous biopsies from obese people with healthy phenotypes. Subcutaneous AT showed a higher correlation between the RAGE signaling axis, inflammatory markers, and the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)[49]. A study with a murine RAGE (-/-) model demonstrated protection against inflammation and oxidative stress and protection against insulin resistance. Interestingly, this model showed that the most beneficial characteristics of RAGE knockout were found in female mice[50]. Additionally, RAGE is related to the adaptive thermogenesis function of brown AT through the decline in energy expenditure caused by a high-fat diet, possibly mediated via the accumulation of AGEs[51,52] (Figure 1B).

In addition to dysregulation in AT discussed above, chronic inflammation also plays a pivotal role in obesity-related insulin resistance that leads to metabolic dysfunction in the liver and muscle. Insulin resistance is characterized by alterations in insulin signaling in sensitive tissues, hyperinsulinemia with defects in glucose uptake in muscle and AT, impaired suppression of hepatic glucose production, and ectopic accumulation of fat in the muscle and liver through re-esterification of fatty acids from AT[53,54] (Figure 1C). To this end, an increase in AGE accumulation in liver biopsies has been linked to RAGE expression, lipid accumulation, and the degree of liver damage without association with the measurements of sRAGE and circulating serum AGEs[55,56]. These studies demonstrate how RAGE affects hepatic conditions caused by the accumulation of AGEs in tissue in non-alcoholic liver disease.

RAGE expression and the accumulation of AGEs are linked to weight gain, inflammation, and oxidative stress markers in human muscle tissue[57]. For instance, one study demonstrated that RAGE expression and the accumulation of AGEs in skeletal muscle in a fructose-supplemented murine model were related to alterations in the oral glucose tolerance test curve, increased triglycerides, inflammatory response, increased basal metabolic rate, and resting metabolic rate[58]. Moreover, chronic AGE exposure is linked to sarcopenia[59]. However, the implications of obesity- and T2DM-induced RAGE expression in muscle tissue are less well explored in humans[60].

Along with the mechanism of trapping excess RAGE ligands in tissues, it is known that the sRAGE form eliminates dangerous circulating ligands and functions as a competitive inhibitor of ligands that might bind to cellular RAGE, supported by studies in which sRAGE levels were found to be low[61-64]. The role of sRAGE in metabolic diseases is debatable because it depends on the degree of disease development and the levels of cell and tissue damage[65]. The cRAGE levels are initially high in acute conditions, triggered by cleavage of flRAGE, which increases its AGE-binding activity. The main variations of sRAGE are attributed to the production of cRAGE shedding by metalloproteinases[66] to compensate for the increase in AGEs in the early stages of low-grade inflammation[67-69]. As the concentration of sRAGE decreases, sequestration and competitive inhibition of ligands decrease and as such they can reach cellular flRAGE, leading to an inflammatory response and subsequent tissue damage[68-70] (Figure 1C).

In prediabetes, plasma levels of sRAGE and esRAGE are all negatively correlated with the HOMA-IR index of insulin resistance and MDA. This correlation matches their reduction as insulin resistance develops in an oxidative environment[67]. Another study with similar results comparing healthy people to those with prediabetes and T2DM found low levels of esRAGE and an inverse linkage with S100A12[71]. Miranda et al[62] showed that all RAGE isoforms were lower when grouped by pancreatic dysfunction (i.e., healthy controls, individuals with glucose intolerance, and those with T2DM). Thus, according to the above, the negative correlation of sRAGE with RAGE ligands or increase of the AGE/esRAGE index seems to be more related to individuals with obesity-related insulin resistance and early T2DM[72], and low cRAGE concentrations are a marker of aging[72,73]. Even the elevated AGE/esRAGE index could distinguish between those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease without T2DM and healthy individuals[74]. Further studies are needed to determine the precise interactions between sRAGE, esRAGE, cRAGE, and their ligands in these disease states.

Since sRAGE and resting energy expenditure are related, one of the most recent discoveries regarding the expression of soluble variants is sRAGE’s contribution to adaptive negative energy balance. In an investigation of the influence of sRAGE on the change in energy expenditure that occurs during weight loss, it was found that, under caloric restriction, adaptive changes arise that slow down energy expenditure. Specifically, after a 3-mo intervention for weight loss due to caloric restriction, energy expenditure increased by 52.6 kcal/d for each 100 pg/mL increase in basal sRAGE levels. Increases in esRAGE and cRAGE similarly translated to concomitant rises in energy expenditure, by 181.6 kcal/d and 56.1 kcal, respectively. This finding illustrates the potential impact of a RAGE feedback mechanism, in which a reduction in sRAGE could slow energy expenditure during weight loss[75]. Furthermore, one mechanism by which RAGE controls energy expenditure is through the suppression of adaptative thermogenesis in white and brown AT via the decline of β-adrenergic signaling in adipocytes blocking protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation targets[76].

Still more, the subcellular localization of RAGE can change, a process related to oligomerization in the membrane after RAGE interaction with ligands[77]. A previous study demonstrated increased localization of RAGE in the cell membrane, rather than the cytoplasm, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of obese individuals with insulin resistance compared with healthy individuals. As such, sRAGE correlates negatively with the HOMA-IR index and tissue damage markers[78] (Figure 1A-C). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells may provide an accessible platform to study the relationship between ligands and cellular RAGE, detect systemic inflammation, and relate these to tissue damage. The preceding argument needs to be tested by additional research.

In T2DM, the pancreas loses its ability to secrete enough insulin in response to meals. One of the mechanisms of pancreas failure is low-grade systemic inflammation. The activating signaling of RAGE in response to ligand binding results in RAGE autoregulation through the increase of its synthesis, which is mediated by NF-kB[79]. In vivo and in vitro models have shown that oxidative stress and inflammation are induced by AGE stimuli through NF-kB activation and the formation of ROS, respectively[80]. These events are evidenced by the increase in the inflammatory serum marker C-reactive protein, particularly in obesity[81]. Some antioxidants and drugs can modulate the AGEs-RAGE axis and the activation of NF-kB, leading to the reduction of lipid peroxidation products in obesity models[82-84].

RAGE expression in the pancreas may be an essential mechanism for the development of T2DM in humans, based on evidence from both in vitro and in vivo glycolipotoxicity studies[85-87]. In a rodent model of diet-induced hyperglycemia, endogenous AGE products are produced, and RAGE expression is observed in pancreatic islets[87]. RAGE inhibition prevented the increase of its expression, and decreased B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) expression and apoptosis of beta cells treated with glycation serum. However, RAGE inhibition did not restore the ability of the beta cells to secrete insulin in response to glucose[85]. RAGE endocytosis regulated by Rab31 ligand can inhibit apoptosis mediated by the pAkt/Bcl-2 pathway in beta cells treated with glycation serum[88]. In another study, the pancreas of db/db transgenic mice that lack the leptin receptor but express RAGE (+/+) have less beta cell mass and less apoptosis, is glucose intolerant, and has decreased insulin secretion. Likewise, when the MIN6 pancreatic beta cell line was treated with palmitate or oleate and leptin antagonists to induce RAGE expression, pancreatic damage occurred[86]. Another mouse model of diabetes induced by streptozotocin and a high-cholesterol diet treated with the water-soluble carotenoid crocin showed attenuated atrophic effects in pancreatic tissue and decreased blood glucose levels through decreases in the expression of RAGE and LOX-1[89].

DAMP/RAGE reports such as the activation of S100b/RAGE and the subsequent loss of beta cells by apoptosis via NADPH oxidase and the protection of sRAGE against amyloid deposition, beta cell loss, and glucose intolerance demonstrate that they interact[90,91]. All of these findings suggest that RAGE can lead to pancreatic failure and the progression of T2DM.

T2DM AND CANCER

Several studies have shown that the incidence of various malignancies increases in patients with T2DM. However, more rigorous statistical analyses of observational studies demonstrate a more significant association of T2DM with colorectal, pancreatic, hepatocellular, breast, and endometrial carcinomas. Even so, there are biases in these studies that make it challenging to study the confounding variables of T2DM leading to cancer[92]. A more recent study included statistical analysis of the “Mendelian randomization” studies to analyze genetic data from large-scale international consortia. Ultimately, it allowed to link a possible causal relationship between genetically predicted T2DM and endometrial and pancreatic cancer risks, and between the variable fasting insulin levels and breast cancer risk. In addition, numerous studies have demonstrated the impact of glycemic traits on the emergence of different malignancies, establishing a relationship between T2DM and cancer[93].

Metabolic and hormonal factors found in patients with obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM, such as hyperinsulinism, hyperglycemia, IGF-1, adipokines, and estrogens, all of which are closely related to inflammation and oxidative stress, function in the long-term as risk factors that support transformation to neoplastic cells in diabetic patients[94].

Estrogens

The increase in estrogen levels in obese patients is due to the positive regulation of the aromatase enzyme, encoded by CYP19A1 and secreted by cells of the tumor stromal microenvironment. The activation mechanisms are triggered in response to hypoxia, with activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), fat tissue hormones (e.g., adipokine leptin, which increases aromatase expression by phosphorylating serine at position 485 of AMPK and inhibiting the aromatase suppressor), and inflammation processes[95]. Estrogen receptors are transcriptional factors of DNA reprogramming that transduce extranuclear signals, resulting in the regulation of ion channels or kinase cascades such as PKC/PKA/PI3-K/MAPK. The metabolic effects of estrogen on both tumor and normal cells are survival, cell proliferation, and immunomodulation[96]. Estrogens are the most relevant risk factor for endometrial and breast cancers, especially in postmenopausal women. Recently, studies have shown that the microbiota is a source of estrogen-like compounds or estrogen mimics that could be involved in cancer progression[97].

Hyperinsulinism and IGF-1

The insulin receptor (IR) and insulin receptor substrate (IRS) are phosphorylated at Ser/Thr residues by inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, resulting in insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia[98]. Insulin induces proliferation in tissues not involved in metabolism. Binding to its receptor (i.e., IR) activates the RAS/RAF/MAPK kinase-dependent/ERK signaling pathways and increases cell survival and migration[99]. Another mechanism is mediated by IGF-1, a hormone structurally and functionally similar to insulin that binds to IR and its receptor (i.e., IGFR). This receptor, like IR, activates pathways that increase cell proliferation, and insulin enhances the liver’s production of IGF-1, elevating the mitogenic activity of cancer cells expressing the IGFR[7,100]. The nuclear protein HMGA1 contributes to the potentiation of insulin action. In addition, the HMGA1 protein overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancer cells functions in chromatin remodeling and gene expression regulation, indirectly promoting enhanced IR expression through the inhibitory effect on p53 expression, which usually keeps IR expression turned off.

Hyperglycemia

Although hyperglycemia is the primary cause of T2DM pathophysiological abnormalities, it also contributes to the development of cancer through several processes that either directly or indirectly harm DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins. The production of ROS, accumulation of mutations and inhibition of their repair, alteration of the immune system, alteration of metabolism, and activation of oncogenes and inactivation tumor suppressor genes are some of the carcinogenic effects that result from the formation of AGEs through non-enzymatic reactions and the subsequent activation of RAGE[101]. Endogenous AGEs are categorized according to their precursor as follows: Glyoxal (GO)-derived compounds including glyoxal lysine dimer, N7-(carboxymethyl)arginine, and CML; methylglyoxal-derived, including MG-H1, methylglyoxal lysine, argpyrimidine, and CEL; 3-deoxyglucosone-derived, including pyrraline, pentosidine, and deoxyglucosone lysine dimer; and derivatives of glucose, fructose, and glyceraldehyde that form DNA adducts or cross-link with lysine or arginine altering protein structure and function[102]. These non-enzymatic protein modifications elevate oxidative stress and inflammation by binding with cell surface receptors such as RAGE. Exogenous AGEs play a role in the progression of cancer in addition to endogenous AGEs[29,103,104]. The metabolism and pathogenic effects of endogenous and exogenous AGEs have recently been the subject of extensive reviews[105].

RAGE AND CANCER

RAGE, inflammation, and oxidative stress

Interactions between RAGE and its ligands in T2DM result in various cellular responses, including activation of signaling pathways that cause oxidative stress and inflammation, which in turn cause various pathophysiological effects such as apoptosis, autophagy[106], senescence, and osteogenic differentiation[107], remodeling processes of the extracellular matrix, and activation of fibroblasts significant in vascular, neuronal[108], and musculoskeletal processes[109]. AGEs in T2DM accumulate in the extracellular matrix, forming cross-links with type I collagen and allowing long-lasting activation of RAGE. This also initiates a complex signaling network that allows the formation of ROS, activates the signaling pathway through ERK1/2 which then phosphorylates and activates NF-kB, and directly induces inflammation. Another alternative signaling pathway to the AGE-RAGE/ERK1-2/PKC pathway involves Rap-1, which induces inflammation, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and oxidative stress[110].

RAGE and hypoxia

Hypoxia is frequent in solid malignant neoplasms due to the high proliferation of neoplastic cells, which does not allow rapid vascularization of neoplastic tissue so that the oxygen demand exceeds the supply. Another factor is the formation of new blood vessels that do not have the integrity of their vascular wall; a continuous outflow of blood results in tissue oxygenation deficiency[111]. Under these conditions, a series of genes regulated by HIF-1α are activated, allowing survival through the expression of genes that promote angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, lipid accumulation[112], inhibition of apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis. HIF-1α also promotes inflammation via NF-kB signaling in hypoxic environments. In this tumor niche with inflammation, hypoxia, and cell death, DAMPs activate the NF-kB pathway mediated by RAGE, thereby amplifying HIF-1α activity[113]. In this hypoxic setting, stromal cells are also affected by RAGE; this is the case in adipocytes, where the AGE/RAGE/NF-kB pathway is activated and prolongs the inflammatory and hypoxic processes. Other effects of hypoxia include the stimulation of cell adhesion mediated by MCP-1, chemotaxis, and the polarization of macrophages towards a proinflammatory phenotype, specifically through the RAGE/NF-kB pathway in tryptophan hydroxylase 1 monocytes[114].

RAGE, survival, and programmed cell death

Cell death is a physiological process that keeps tissues healthy by systematically removing damaged cells to prevent an immune response. Although necrosis is a kind of cell death, it is pathological and only happens when there has been a significant tissue injury coupled with an immune response. Non-pathological cell death can take many forms, including apoptosis, necroptosis, and autophagy[115]. RAGE is involved in all three death pathways and can be activated by AGEs, HMGB1, and S100. In normal tissues, both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways are activated[116], and ROS, NF-kB, and MAPK mediate the stimulation. High levels of ROS induce the apoptosis pathway, but if they are low, autophagy is activated. Reduced HMGB1 activates Beclin-1-mediated autophagy pathways, but if oxidized, it activates apoptosis[117].

RAGE promotes cancer cell autophagy, which eventually permits survival by utilizing nutrients through the catabolism of their cellular components in a blood-free environment with no access to external nutrients and hypoxia. RAGE-dependent signaling pathways that promote autophagy involve PI3K, NF-kB/Beclin-1, PKC, and/or RAF/p38-MAPK/ERK[118]. Likewise, in cancer cells, apoptosis is inhibited, which indirectly allows cell perpetuation and survival. The pathways that inhibit apoptosis start with the binding of HMBG1/RAGE, which induces the formation of ROS and activation of NF-kB; another pathway involves Akt and matrix metalloproteinase-9[119].

RAGE and senescent cells

Cell senescence is present in T2DM and cancer. Frequently occurring in tissues undergoing metabolic shock, chronic inflammation, or oxidative stress, cell senescence is a physiological response that aims to prevent genomic instability and the consequent DNA damage that leads to metabolic reprogramming. In addition, senescence relates to decreasing immune surveillance, thus facilitating cancer initiation and progression[109,119-121]. The same markers found in the carcinogenesis process discussed above, such as IGF, HIF-1α, AGEs, and RAGE, were discovered in a proteomics study looking for plasma proteins that indicate a senescence-related decline in health[122]. In a model of endothelial senescence induced by protein products of advanced oxidation, the presence of modified p53 at amino acid K386 by SUMOylation was associated with evasion of apoptosis[123].

RAGE ligands

RAGE aids in the removal of endotoxins and debris from apoptotic bodies during the processes of oxidative stress, hypoxia, and inflammation. Cellular damage occurs that causes the release of intracellular molecules that, outside the cell, behave as alarmins, specifically the S100 and HMBG1 proteins, also known as DAMPs, which act as endogenous RAGE ligands[124]. These proteins are also known as “moonlighting proteins” since they have various functions depending on their location. For example, when the HMGB1 protein locates inside the nucleus, it organizes chromatin[125]. In contrast, S100 is a protein that functions as a Ca2+ sensor[126], and like HMGB1, when located extracellularly, it functions as an alarmin. Tumor initiation and progression, as well as tissue damage, are significantly influenced by endogenous DAMP/RAGE ligand signaling. Numerous malignancies, including colorectal[127], hepatocarcinoma[128], pancreatic[129], breast, and endometrial cancers, overexpress HMGB1 and S100[35].

The primary ligands that bind to RAGE in cancer cells, such as AGEs, HMGB1, and S100, activate several signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt, ERK 1/2, JAK/STAT, Ras/MAPK, Rac/cdc42, p14/p42, p38, and SAP/JNK/MAPK, and transcription factors such as NF-kB, STAT3, HIF-1α, AP-1, and CREB[118,130], and thus activate a series of genes whose functions are essential in the initiation, promotion, and extension of various malignant neoplasms. These functions are known as “cancer hallmarks” and include cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, inhibition of tumor suppressor genes, evasion of immunity, increased survival, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, genomic instability due to failure to repair mutations, and metabolic dysregulation[35,124] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies published between 2018 and 2022 on receptor for advanced glycation products-ligands, related activated pathways, and cancer hallmarks in the most frequent neoplasms found in diabetic patients

|

Neoplasia

|

Ligands and signaling pathway

|

Molecule expressed

|

Cancer hallmarks

|

TS/AM/CL

|

Ref.

|

| Breast cancer | AGE/RAGE, ERK1/2; Akt, c-fos | IL-8/CXCR1/2 | Migration and invasion | CL; CAFs, TNBC (MDA-MB-231 cells) | Santolla et al[137] |

| HMGA1 | Cell proliferation, metastasis, and EMT | CL; TNBC (MDA-MB-231 and Hs578) | Shah et al[138] | ||

| HMGB1/RAGE | Motility, migration, invasion, and dysregulation of metabolism | TS; human breast cancer, AM; NOD/SCID mice, CL; human breast cancer cells (MCF-7, T-470, BT474, MDA-MB-231, ZR-75-30, BT549) and human fibroblast cells HFL1 | Chen et al[139] | ||

| HMGB1/PI3K/Akt | PD-L1 | Cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and T-cell apoptosis | CL; human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 P, MDA-MB-231 BM) | Amornsupak et al[140] | |

| HMGB1, PI3K/Akt, mTOR | HIF-1α, VEGF | Migration and angiogenesis | TS; human breast cancer CL; human breast cancer cells MCF-7 | He et al[141] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE | Downregulation of miR-205 | Cell growth, invasion, and EMT | TS; human breast cancer CL; TNBC (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-468) and NTNBC (MCF-7, MCF-10F) | Wang et al[142] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, ERK 1/2, CREB | Bone metastasis and neurite outgrowth of nervous system cells | AM; 4T1 mice CL; mouse breast cancer 4T1, primary rat nervous system cells DRG, rat DRG/mouse neuroblastoma hybrid cells F11, immortalized rat DRG neuronal cells 50B11 | Okui et al[143] | ||

| S100A14/RAGE, NF-kB | CCL2/CXCL5 | Migration, invasion, and lung metastasis | TS; human breast cancer and paired adjacent breast normal, metastatic lymph node, and non-metastatic lymph node AM; BALB/c, BALB/c, SCID beige, C57BL/6J, CMV-CreC57BL/6J, S200-/- and S100A14-/- PyMT mice CL; human breast cancer cells MCF7, MCF10A, T47D, SKBR3, BT549, MDA-MB-231, MCF10AT, MCFCA1h, MCFCA1α and mouse breast cancer cells 4T1 | Li et al[144] | |

| S100A7/RAGE, PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2, STAT3 | IGF-1 | Angiogenesis | CL; human breast cancer cells MCF-7, T47D, and HUVECs cells | Muoio et al[145] | |

| S100A7/RAGE, cPLA | PGE2, CD163+ | Immunosuppression, M2-macrophages, CD4+, CD8+, and T cells | AM; NOD SCID gamma mice CL; human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468 and mouse mammary cancer cells MVT-1 | Mishra et al[146] | |

| S100A8/A9-RAGE, FAK, Akt, Hippo-YAK | FLNA, CTGF, Cyr61 | Cell proliferation and migration | CL; HEK293T and TNBC (MDA-MB-23 and BT-549) | Rigiracciolo et al[147] | |

| LPS/S100A7/TLR4/RAGE | Migration and invasion | AM; orthotopic breast cancer C57BL/6 mice model CL; murine mammary cancer cells EO771, MTV-1, murine metastatic mammary cells EO.2, human breast carcinoma cells SUM 159, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 | Wilkie et al[148] | ||

| acHMGB1/RAGE, S100A4/RAGE, Gas6/AXL | CXCR4, CXCL12, CCL2, CD151 and α3β1-integrin | Cell proliferation, invasion, intravasation, and EMT | AM; murine orthotopic mammary cancer CL; human MSCs, geminin overexpressing breast tumors Gem197, Gem240, Gem256, Gem257 and Gem270 cells, CAFs, and M0- TAMs and M2-TAMs | Ryan et al[149] | |

| Colorectal cancer | S100A16 | Cancer prognostic marker | TS; human colorectal cancer | Sun et al[150] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE | PD-1 | Cancer prognostic marker | TS; human colorectal cancer CL; human colorectal cancer cells SW480, and SW620 | Huang et al[151] | |

| S100B/RAGE, NF-kB | VEGF-A | Proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis | CL; human colon cancer cells HCT116 | Zheng et al[152] | |

| IGF1R-Ras/RAGE-HMGB1, | Oncogenesis | TS; Human colorectal from diabetic patients | Niu et al[153] | ||

| AGEs/RAGE, KLF5 | MDM upregulation and RB and p53 downregulation | Cancer initiation and development | AM; diabetic mouse model and CL; human colon cancer cells HCT116 | Wang et al[154] | |

| TCTP, HMGB1/RAGE, NF-kB | Invasion and metastasis | TS; human colorectal AM; tumor xenografts BALB/c nude mice CL; human colon adenocarcinoma cells LoVo | Huang et al[155] | ||

| S100A9/RAGE/TLR4 | Arg-1, iNOS, IL-10 and ROS | Immune suppression and MDSC chemotaxis | TS; human colorectal cancer and normal colon CL; Human colorectal cells LoVo, and MDSCs | Huang et al[156] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, Kras/Yap1 | Cell proliferation | CL; human colorectal cancer cells HCT116 and SW480 | Qian et al[157] | ||

| S100B/RAGE, p38/pAkt/mTOR | VEGF-R2, iNOS, VEGF | Cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis | CL; human colon adenocarcinoma cells CaCo | Seguella et al[158] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, pERK1/2, pDRP1 | Cell viability, autophagy, and chemoresistance | TS; human colorectal AM; athymic nude BALBC/c mice CL; human colorectal cells SW480, SW620, and LoVo | Huang et al[159] | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | S100A9-TLR4/RAGE-ROS, | NET | Cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | TS; HBV+ and HBV-hepatocellular carcinoma AM; BALB/c mice and C57BL/6 mice CL; human liver cells QSG-7701, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2.2.15, mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells H22 and HUVEC cells | Zhan et al[160] |

| HMGB1/RAGE | Cell proliferation and tumor differentiation | TS; primary hepatocellular carcinoma | Ando et al[161] | ||

| HMGB1/RAGE, ATG7 | Cell proliferation, fibrosis, and autophagy | TS; mouse hepatocellular carcinoma AM; Atg7, RAGE, HMGB1 transgenic C57BL/6Jmouse | Khambu et al[128] | ||

| HMGB1/RAGE, JNK, OCT4/TGFb1 | miR-21, CD44 | Migration and invasion | TS; human hepatocellular carcinoma AM; BALB/c nu/nu mice CL; human hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2, HCCLM3, Huh7, SMMC7721 and MHCC97H | Li et al[162] | |

| S100A4/RAGE, b-catenin | OCT4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog (stem cell-associated genes) | Fibrosis and carcinogenesis | TS; human hepatocellular carcinoma AM; S100a4-EGFP, S100A4+/+GFP, S100A4-/- transgenic mice. CL; human hepatocellular carcinoma cells Huh7 and murine liver cancer cells Hep1-6 | Li et al[163] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, ERK1/2 | CXCL2, IL-8, TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-23-p19 | Macrophage activation and inflammation | AM; primary murine hepatocytes from male C57BI/6J mice, and primary murine splenocytes from male C57BI/CJ CC; murine hepatoma cells Hepa1-6 and Hep-56.1D, human hepatoma cells HepG2, RAW 264.7 macrophages and monocytic cells THP1 | Bachmann et al[164] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, NF-kB | circRNA 101368, miR-200a | Cell migration | TS; human hepatocellular carcinoma CL; human hepatocellular carcinoma cells HCCLM3, MHCC97L, SMMC7721, Hep3B, HepG2 cells, and normal hepatocyte cells THLE-3 | Li et al[165] | |

| Pancreatic cancer | RAGE | NET | Neutrophil autophagy | TS; human pancreatic carcinoma AM; Wild type C57BL6 mice and RAGE-/- C57BL6 mice, orthotopic pancreatic cancer model, CL; murine pancreatic cancer cells Panc02, MDSCs cells | Boone et al[166] |

| RAGE, PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Cell viability | CL; human pancreatic cancer cells MIA Paca-2, BxPC-3, AsPC-1, HPAC, PANC-1, MIA PacaGEMR | Lan et al[167] | ||

| RAGE, ERK1/2/Akt | Alpha 2 and alpha 1 integrin downregulation | Cell proliferation, invasion, and migration | CL; human pancreatic cancer cells Panc-1 | Swami et al[129] | |

| AGE/RAGE, TGFb1 | a-SMA, collagen 1, IL-6 | Fibrosis and EMT | TS; human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma AM; WT-C57BL/6 and RG-C57BL/6 mice CL; primary PSC, human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 | Uchida et al[168] | |

| HMGB1/RAGE, PI3K/Akt | Atg5, Beclin-1, LC3-II | Autophagia and apoptosis inhibition | CL; human pancreatic cancer cells MIA Paca-2 and MIA PacaGEMR | Chen et al[169] |

AGE: Advanced glycation end products; Akt: Protein kinase B; AM: Animal model; Arg-1: Arginase-1; ATG7: Autophagy related 7; CAFs: Cancer-associated fibroblasts; CCL2: CC-chemokine ligand 2; circRNA: Circular RNA; CL: Cell line; cPLA: Cytosolic phospholipase A2; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; CTGF: Connective tissue growth factor; CXCL: CXC motif chemokine ligand; CXCR: C-X-C Chemokine receptor; Cyr61: Cysteine-rich angiogenic 61; DRG: Dorsal rat ganglion; pDRP1: Phosphorylated dynamin-related protein 1; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ERK 1/2: Extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; FLNA: Filamin A alpha; HIF-1α: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; Gas6: Growth arrest-specific gene 6; HMG: High mobility group; acHMGB1: Acetylated high mobility group B1; HUVECs: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells; IGF-1: Insulin-like growth factor-1; JNK: Jun N-terminal kinase; KLF5: Kruppel-like factor 5; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MDA-MB-231 P: MDA-MB-231 Parental cells; MDA-MB-231 BM: MDA-MB-231 bone marrow; MDM: Mouse double minute 2 homolog; MDSCs: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells; MIA PacaGEMR: MIA Paca gemcitabine resistant; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells; mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin; NET: Neutrophil extracellular traps; NF-kB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; NTNBC: Non-triple-negative breast cancer; OCT-4: Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PD-L1: Programmed death ligand 1; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; PSC: Pancreatic stellate cell; Ras: Rat sarcoma virus; RB: Retinoblastoma; RAGE: Receptor for advanced glycation end products; S100: Soluble 100% protein; a-SMA: Alpha-smooth muscle actin; SOX2: SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2; STAT3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TAMs: Tumor-associated macrophages; TCTP: Translationally controlled tumor protein; TGFb1: Tumor growth factor beta 1; THP1: Human monocytic cell line derived from acute monocytic leukemia; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TNBC: Triple-negative breast cancer; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; TS: Tissue sample; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; Yap1: Yes associated protein 1.

RAGE and tumor microenvironment

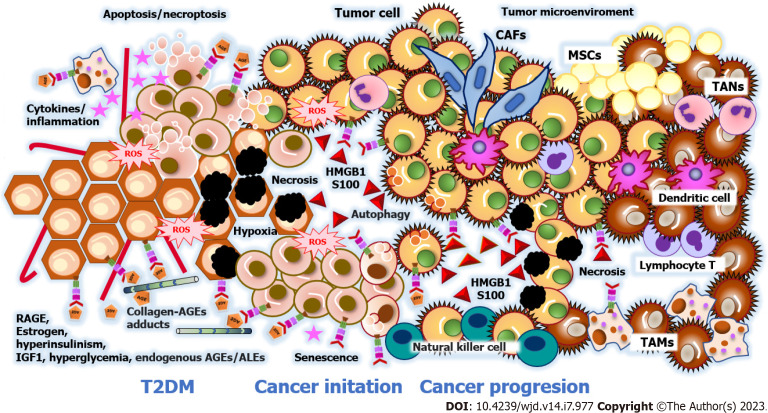

Tumorigenesis is the process by which healthy cells develop the capacity to become cancerous cells, which implies, in addition to genetic and epigenetic alterations in DNA, the formation of the tumor microenvironment. The tumor microenvironment is determined by the interaction between resident immune cells, mesenchymal stromal cells, and tumor cells, the paracrine signaling between them, and the anatomical niche built-up by the extracellular matrix and blood vessels. In addition to cancer-affected fibroblasts, the tumor microenvironment contains infiltrating tumor-associated macrophages that promote tumor survival[131,132]. The tumor microenvironment includes the extracellular matrix, blood vascular structures, and paracrine signaling between stromal cells and tumor cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tumor microenvironment in type 2 diabetes mellitus. In type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, elevated estrogen levels, hyperinsulinemia, insulin-like growth factor-1 levels, hyperglycemia, endogenous advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), and advanced lipoperoxidation end products (ALEs) promote cancer initiation and progression in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE) plays an essential role in the TME by promoting inflammation, oxidative stress, endotoxin clearance, senescence, and programmed cell death by binding to endogenous AGE/ALE ligands and damage-associated molecular patterns, primarily the high mobility group box 1 proteins and S100 proteins. To overcome a hypoxic and acidic microenvironment, tumor cells coordinate a metabolic program (Warburg effect), cell survival (senescence and cell death program), angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Tumor cells interact with resident immune cells and recruit mesenchymal stromal cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages, tumor-associated neutrophils. RAGE: Receptor for advanced glycation products; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients; IGF-1: Insulin-like growth factor-1; AGEs: Advanced glycosylation end products; ALEs: Advanced lipoperoxidation end products; HMGB1: High mobility group box 1 proteins; MSCs: Mesenchymal stromal cells; CAFs: Cancer-associated fibroblasts; TAMs: Tumor-associated macrophages; TANs: Tumor-associated neutrophils.

Recent studies have revealed that the involved cells and specialized three-dimensional structures are unique to each tumor by tissue[133-135]. Table 1 outlines the traits of the tumor microenvironment in hepatocarcinoma, colorectal, breast, and pancreatic cancers with RAGE implications. These findings demonstrate that RAGE promotes different adaptive phenomena for the survival, initiation, and progression of malignant tumors. Nevertheless, it is necessary to mention that RAGE overexpression varies in cancer related to T2DM because of the cellular heterogeneity of the neoplastic process. The Human Protein Atlas database shows RAGE detection rates in malignant cells by immunohistochemistry as follows: Hepatocarcinoma at 50%; pancreatic cancer at 33.3%; breast cancer at 25%; endometrial cancer at 16.6%; and colorectal cancer at 8.3%[136].

CONCLUSION

RAGE is an environmental sensor with complex and multiple functions involved in every stage along the patho-physiological pathways that lead to the progression of obesity, T2DM, and cancer. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze each of the processes that RAGE is involved in, as the assimilation of this information could help in developing more accurate diagnostic and treatment approaches. For instance, this review has highlighted how RAGE acts from the earliest stages of the initiation and development of obesity, T2DM, and cancer. Recognizing all participating RAGE isoforms in their tissue and cellular locations could predict the progression points and provide diagnostic markers. In this manner, we would also be able to distinguish between a patient who is obese, has a low grade of inflammation, and is on the frontline of developing T2DM or most likely to respond to nutritional intervention.

On the other hand, RAGE participates in the initiation of neoplastic processes. Since its presence indicates cellular senescence and the presence of cancer cells with more aggressive activity, it is not surprising related to a poor prognosis and has potential as a cancer biomarker to help predict patient outcomes. Since RAGE participates even in the first stages, it has potential as a preventive and immunomodulator for therapeutic purposes to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with the development of obesity, T2DM, and cancer. Inhibitors of RAGE may be helpful in the treatment of obesity and diabetes mellitus. Studies have shown that RAGE is overexpressed in AT. Obesity is well known to contribute to inflammation and insulin resistance, which are hallmarks of obesity and diabetes. RAGE inhibitors could reduce inflammation and improve insulin sensitivity in obesity and T2DM; however, the majority of RAGE inhibitor studies have focused on cancer treatment. Some RAGE inhibitors under study are cromolyn, RAP, RAGE peptide antagonist, and gefitinib. While there are currently no RAGE-specific therapies approved for use in humans, there are pre-clinical studies investigating the potential of RAGE inhibitors as a treatment for various diseases. We review herein the topically relevant literature, delimiting by process, organ, and tissue to provide a progressive and systemic overview. It should be read and generalized with caution, as there are still many gaps in the knowledge about RAGE since most studies are experimental-based (in mice) and cross-sectional studies (in humans).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge Ruelas-Cinco EC for providing some photographic images of RAGE immunocytochemistry in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from her thesis.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: January 9, 2023

First decision: January 17, 2023

Article in press: April 17, 2023

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pahlavani HA, Iran; Preziosi F, Italy; Srinivasu PN, India; Yang JS, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S

Contributor Information

Andrea Garza-Campos, Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias en Biología Molecular en Medicina, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico; Departamento de Biología Molecular y Genómica, Instituto de Investigación en Enfermedades Crónico-Degenerativas, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico.

José Roberto Prieto-Correa, Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias en Biología Molecular en Medicina, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico; Departamento de Biología Molecular y Genómica, Instituto de Investigación en Enfermedades Crónico-Degenerativas, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico.

José Alfredo Domínguez-Rosales, Departamento de Biología Molecular y Genómica, Instituto de Investigación en Enfermedades Crónico-Degenerativas, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico.

Zamira Helena Hernández-Nazará, Departamento de Biología Molecular y Genómica, Instituto de Investigación en Enfermedades Crónico-Degenerativas, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Jalisco, Mexico. zamirahelena@yahoo.com.mx.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. [cited 5 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1 .

- 2.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ugai T, Sasamoto N, Lee HY, Ando M, Song M, Tamimi RM, Kawachi I, Campbell PT, Giovannucci EL, Weiderpass E, Rebbeck TR, Ogino S. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:656–673. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de González A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2076–2083. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane MM, Davis JA, Beattie S, Gómez-Donoso C, Loughman A, O'Neil A, Jacka F, Berk M, Page R, Marx W, Rocks T. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13146. doi: 10.1111/obr.13146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts DL, Dive C, Renehan AG. Biological mechanisms linking obesity and cancer risk: new perspectives. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:301–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.080708.082713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Greevenbroek MM, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Obesity-associated low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: causes and consequences. Neth J Med. 2013;71:174–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuah YK, Basir R, Talib H, Tie TH, Nordin N. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and its involvement in inflammatory diseases. Int J Inflam. 2013;2013:403460. doi: 10.1155/2013/403460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP. Multiple levels of regulation determine the role of the receptor for AGE (RAGE) as common soil in inflammation, immune responses and diabetes mellitus and its complications. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2251–2263. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson BI, Carter AM, Harja E, Kalea AZ, Arriero M, Yang H, Grant PJ, Schmidt AM. Identification, classification, and expression of RAGE gene splice variants. FASEB J. 2008;22:1572–1580. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9909com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The biology of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clynes R, Moser B, Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Herold K, Schmidt AM. Receptor for AGE (RAGE): weaving tangled webs within the inflammatory response. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:743–751. doi: 10.2174/156652407783220714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Z, Zhu L, Wu J. RAGE signalling in obesity and diabetes: focus on the adipose tissue macrophage. Adipocyte. 2020;9:563–566. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2020.1817278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arivazhagan L, Popp CJ, Ruiz HH, Wilson RA, Manigrasso MB, Shekhtman A, Ramasamy R, Sevick MA, Schmidt AM. The RAGE/DIAPH1 axis: mediator of obesity and proposed biomarker of human cardiometabolic disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bettiga A, Fiorio F, Di Marco F, Trevisani F, Romani A, Porrini E, Salonia A, Montorsi F, Vago R. The Modern Western Diet Rich in Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): An Overview of Its Impact on Obesity and Early Progression of Renal Pathology. Nutrients. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/nu11081748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arivazhagan L, López-Díez R, Shekhtman A, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. Glycation and a Spark of ALEs (Advanced Lipoxidation End Products) - Igniting RAGE/Diaphanous-1 and Cardiometabolic Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:937071. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.937071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemet I, Varga-Defterdarović L, Turk Z. Methylglyoxal in food and living organisms. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:1105–1117. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poulsen MW, Hedegaard RV, Andersen JM, de Courten B, Bügel S, Nielsen J, Skibsted LH, Dragsted LO. Advanced glycation endproducts in food and their effects on health. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;60:10–37. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheijen JLJM, Clevers E, Engelen L, Dagnelie PC, Brouns F, Stehouwer CDA, Schalkwijk CG. Analysis of advanced glycation endproducts in selected food items by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: Presentation of a dietary AGE database. Food Chem. 2016;190:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson AB, Stogsdill JA, Lewis JB, Wood TT, Reynolds PR. RAGE and tobacco smoke: insights into modeling chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:301. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad K, Dhar I, Caspar-Bell G. Role of Advanced Glycation End Products and Its Receptors in the Pathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke-Induced Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Angiol. 2015;24:75–80. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon OS, Decker ST, Zhao J, Hoidal JR, Heuckstadt T, Sanders KA, Richardson RS, Layec G. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is involved in mitochondrial function and cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;195:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman S, Mick M, Hall P, Mejia C, Sue S, Abdul Wase B, Nguyen MA, Whisenant EC, Wilcox SH, Winden D, Reynolds PR, Arroyo JA. Cigarette smoke extract induces oral squamous cell carcinoma cell invasion in a receptor for advanced glycation end-products-dependent manner. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126:33–40. doi: 10.1111/eos.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Qin M, Zhong W, Liu C, Deng G, Yang M, Li J, Ye H, Shi H, Wu C, Lin H, Chen Y, Huang S, Zhou C, Lv Z, Gao L. RAGE promotes dysregulation of iron and lipid metabolism in alcoholic liver disease. Redox Biol. 2023;59:102559. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birukov A, Cuadrat R, Polemiti E, Eichelmann F, Schulze MB. Advanced glycation end-products, measured as skin autofluorescence, associate with vascular stiffness in diabetic, pre-diabetic and normoglycemic individuals: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:110. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwara Y, Kiyota N, Tsurushima K, Yoshitomi M, Mera K, Sakashita N, Takeya M, Ikeda T, Araki T, Nohara T, Nagai R. Natural compounds containing a catechol group enhance the formation of Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine of the Maillard reaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson MM, Requena JR, Crowley JR, Thorpe SR, Heinecke JW. The myeloperoxidase system of human phagocytes generates Nepsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine on proteins: a mechanism for producing advanced glycation end products at sites of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:103–113. doi: 10.1172/JCI3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twarda-Clapa A, Olczak A, Białkowska AM, Koziołkiewicz M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/cells11081312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryder E, Pedreañez A, Vargas R, Peña C, Fernandez E, Diez-Ewald M, Mosquera J. Increased proinflammatory markers and lipoperoxidation in obese individuals: Inicial inflammatory events? Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra S, Mishra BB. Study of Lipid Peroxidation, Nitric Oxide End Product, and Trace Element Status in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with and without Complications. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2017;7:88–93. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.205813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaganjac M, Tirosh O, Cohen G, Sasson S, Zarkovic N. Reactive aldehydes--second messengers of free radicals in diabetes mellitus. Free Radic Res. 2013;47 Suppl 1:39–48. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.789136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iacobini C, Menini S, Ricci C, Scipioni A, Sansoni V, Mazzitelli G, Cordone S, Pesce C, Pugliese F, Pricci F, Pugliese G. Advanced lipoxidation end-products mediate lipid-induced glomerular injury: role of receptor-mediated mechanisms. J Pathol. 2009;218:360–369. doi: 10.1002/path.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanmugam N, Figarola JL, Li Y, Swiderski PM, Rahbar S, Natarajan R. Proinflammatory effects of advanced lipoxidation end products in monocytes. Diabetes. 2008;57:879–888. doi: 10.2337/db07-1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palanissami G, Paul SFD. RAGE and Its Ligands: Molecular Interplay Between Glycation, Inflammation, and Hallmarks of Cancer-a Review. Horm Cancer. 2018;9:295–325. doi: 10.1007/s12672-018-0342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Dongen KCW, Kappetein L, Miro Estruch I, Belzer C, Beekmann K, Rietjens IMCM. Differences in kinetics and dynamics of endogenous versus exogenous advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and their precursors. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022;164:112987. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.112987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyte JM, Gabler NK, Hollis JH. Postprandial serum endotoxin in healthy humans is modulated by dietary fat in a randomized, controlled, cross-over study. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:186. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0357-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Peng Y, Shen Y, Zhang Y, Liu L, Yang X. Dietary polyphenols: regulate the advanced glycation end products-RAGE axis and the microbiota-gut-brain axis to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022:1–27. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2076064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmée E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrières J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Wu J, Guo X, Huang X, Huang Q. RAGE Plays a Role in LPS-Induced NF-κB Activation and Endothelial Hyperpermeability. Sensors (Basel) 2017;17 doi: 10.3390/s17040722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritz G. RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Wang Y, Antony V, Sun H, Liang G. Metabolism-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs) Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020;31:712–724. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turki Jalil A, Alameri AA, Iqbal Doewes R, El-Sehrawy AA, Ahmad I, Ramaiah P, Kadhim MM, Kzar HH, Sivaraman R, Romero-Parra RM, Ansari MJ, Fakri Mustafa Y. Circulating and dietary advanced glycation end products and obesity in an adult population: A paradox of their detrimental effects in obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:966590. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.966590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz HH, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. Advanced Glycation End Products: Building on the Concept of the "Common Soil" in Metabolic Disease. Endocrinology. 2020;161 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqz006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaens KH, Goossens GH, Niessen PM, van Greevenbroek MM, van der Kallen CJ, Niessen HW, Rensen SS, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Blaak EE, van Zandvoort MA, Bierhaus A, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG. Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine-receptor for advanced glycation end product axis is a key modulator of obesity-induced dysregulation of adipokine expression and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1199–1208. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sebeková K, Krivošíková Z, Gajdoš M. Total plasma Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine and sRAGE levels are inversely associated with a number of metabolic syndrome risk factors in non-diabetic young-to-middle-aged medication-free subjects. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:139–149. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dozio E, Vianello E, Briganti S, Lamont J, Tacchini L, Schmitz G, Corsi Romanelli MM. Expression of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products in Epicardial Fat: Link with Tissue Thickness and Local Insulin Resistance in Coronary Artery Disease. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2327341. doi: 10.1155/2016/2327341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santangelo C, Filardi T, Perrone G, Mariani M, Mari E, Scazzocchio B, Masella R, Brunelli R, Lenzi A, Zicari A, Morano S. Cross-talk between fetal membranes and visceral adipose tissue involves HMGB1-RAGE and VIP-VPAC2 pathways in human gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:681–689. doi: 10.1007/s00592-019-01304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz HH, Nguyen A, Wang C, He L, Li H, Hallowell P, McNamara C, Schmidt AM. AGE/RAGE/DIAPH1 axis is associated with immunometabolic markers and risk of insulin resistance in subcutaneous but not omental adipose tissue in human obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021;45:2083–2094. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00878-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du Z, Wu J, Feng Z, Ma X, Zhang T, Shu X, Xu J, Wang L, Luo M. RAGE displays sex-specific differences in obesity-induced adipose tissue insulin resistance. Biol Sex Differ. 2022;13:65. doi: 10.1186/s13293-022-00476-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song F, Hurtado del Pozo C, Rosario R, Zou YS, Ananthakrishnan R, Xu X, Patel PR, Benoit VM, Yan SF, Li H, Friedman RA, Kim JK, Ramasamy R, Ferrante AW Jr, Schmidt AM. RAGE regulates the metabolic and inflammatory response to high-fat feeding in mice. Diabetes. 2014;63:1948–1965. doi: 10.2337/db13-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding YS, Malik N, Mendoza S, Tuchman D, Del Pozo CH, Diez RL, Schmidt AM. PET imaging study of brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity in mice devoid of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) J Biosci. 2019;44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.da Silva Rosa SC, Nayak N, Caymo AM, Gordon JW. Mechanisms of muscle insulin resistance and the cross-talk with liver and adipose tissue. Physiol Rep. 2020;8:e14607. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li M, Chi X, Wang Y, Setrerrahmane S, Xie W, Xu H. Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:216. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Priken K, Tapia G, Cadagan C, Quezada N, Torres J, D'Espessailles A, Pettinelli P. Higher hepatic advanced glycation end products and liver damage markers are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Nutr Res. 2022;104:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaens KH, Niessen PM, Rensen SS, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Driessen A, Wolfs MG, Hofker MH, Bloemen JG, Dejong CH, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG. Endogenous formation of Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine is increased in fatty livers and induces inflammatory markers in an in vitro model of hepatic steatosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de la Maza MP, Uribarri J, Olivares D, Hirsch S, Leiva L, Barrera G, Bunout D. Weight increase is associated with skeletal muscle immunostaining for advanced glycation end products, receptor for advanced glycation end products, and oxidation injury. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:1041–1048. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rai AK, Jaiswal N, Maurya CK, Sharma A, Ahmad I, Ahmad S, Gupta AP, Gayen JR, Tamrakar AK. Fructose-induced AGEs-RAGE signaling in skeletal muscle contributes to impairment of glucose homeostasis. J Nutr Biochem. 2019;71:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dozio E, Vettoretti S, Lungarella G, Messa P, Corsi Romanelli MM. Sarcopenia in Chronic Kidney Disease: Focus on Advanced Glycation End Products as Mediators and Markers of Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9040405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riuzzi F, Sorci G, Sagheddu R, Chiappalupi S, Salvadori L, Donato R. RAGE in the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9:1213–1234. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basta G, Sironi AM, Lazzerini G, Del Turco S, Buzzigoli E, Casolaro A, Natali A, Ferrannini E, Gastaldelli A. Circulating soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products is inversely associated with glycemic control and S100A12 protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4628–4634. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miranda ER, Somal VS, Mey JT, Blackburn BK, Wang E, Farabi S, Karstoft K, Fealy CE, Kashyap S, Kirwan JP, Quinn L, Solomon TPJ, Haus JM. Circulating soluble RAGE isoforms are attenuated in obese, impaired-glucose-tolerant individuals and are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;313:E631–E640. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00146.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Momma H, Niu K, Kobayashi Y, Huang C, Chujo M, Otomo A, Tadaura H, Miyata T, Nagatomi R. Higher serum soluble receptor for advanced glycation end product levels and lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Japanese adult men: a cross-sectional study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaki M, Kamal S, Kholousi S, El-Bassyouni HT, Yousef W, Reyad H, Mohamed R, Basha WA. Serum soluble receptor of advanced glycation end products and risk of metabolic syndrome in Egyptian obese women. EXCLI J. 2017;16:973–980. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Biswas SK, Mohtarin S, Mudi SR, Anwar T, Banu LA, Alam SM, Fariduddin M, Arslan MI. Relationship of Soluble RAGE with Insulin Resistance and Beta Cell Function during Development of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:150325. doi: 10.1155/2015/150325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hudson BI, Dong C, Gardener H, Elkind MS, Wright CB, Goldberg R, Sacco RL, Rundek T. Serum levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products and metabolic syndrome: the Northern Manhattan Study. Metabolism. 2014;63:1125–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang M, Que Y, Shen X. Correlation of the plasma levels of soluble RAGE and endogenous secretory RAGE with oxidative stress in pre-diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:422–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prasad K. Is there any evidence that AGE/sRAGE is a universal biomarker/risk marker for diseases? Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;451:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s11010-018-3400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erusalimsky JD. The use of the soluble receptor for advanced glycation-end products (sRAGE) as a potential biomarker of disease risk and adverse outcomes. Redox Biol. 2021;42:101958. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prasad K, Khan AS, Bhanumathy KK. Does AGE-RAGE Stress Play a Role in the Development of Coronary Artery Disease in Obesity? Int J Angiol. 2022;31:1–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1742587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Pino A, Urbano F, Zagami RM, Filippello A, Di Mauro S, Piro S, Purrello F, Rabuazzo AM. Low Endogenous Secretory Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Products Levels Are Associated With Inflammation and Carotid Atherosclerosis in Prediabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1701–1709. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sabbatinelli J, Castiglione S, Macrì F, Giuliani A, Ramini D, Vinci MC, Tortato E, Bonfigli AR, Olivieri F, Raucci A. Circulating levels of AGEs and soluble RAGE isoforms are associated with all-cause mortality and development of cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:95. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01535-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scavello F, Tedesco CC, Castiglione S, Maciag A, Sangalli E, Veglia F, Spinetti G, Puca AA, Raucci A. Modulation of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products isoforms and advanced glycation end products in long-living individuals. Biomark Med. 2021;15:785–796. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2020-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palma-Duran SA, Kontogianni MD, Vlassopoulos A, Zhao S, Margariti A, Georgoulis M, Papatheodoridis G, Combet E. Serum levels of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and the decoy soluble receptor for AGEs (sRAGE) can identify non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in age-, sex- and BMI-matched normo-glycemic adults. Metabolism. 2018;83:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Popp CJ, Zhou B, Manigrasso MB, Li H, Curran M, Hu L, St-Jules DE, Alemán JO, Vanegas SM, Jay M, Bergman M, Segal E, Sevick MA, Schmidt AM. Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (sRAGE) Isoforms Predict Changes in Resting Energy Expenditure in Adults with Obesity during Weight Loss. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6:nzac046. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hurtado Del Pozo C, Ruiz HH, Arivazhagan L, Aranda JF, Shim C, Daya P, Derk J, MacLean M, He M, Frye L, Friedline RH, Noh HL, Kim JK, Friedman RA, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. A Receptor of the Immunoglobulin Superfamily Regulates Adaptive Thermogenesis. Cell Rep. 2019;28:773–791.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Popa I, Ganea E, Petrescu SM. Expression and subcellular localization of RAGE in melanoma cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;92:127–136. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2013-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruelas Cinco EDC, Ruíz Madrigal B, Domínguez Rosales JA, Maldonado González M, De la Cruz Color L, Ramírez Meza SM, Torres Baranda JR, Martínez López E, Hernández Nazará ZH. Expression of the receptor of advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) and membranal location in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in obesity and insulin resistance. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019;22:623–630. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2019.34571.8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li J, Schmidt AM. Characterization and functional analysis of the promoter of RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16498–16506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yan SD, Schmidt AM, Anderson GM, Zhang J, Brett J, Zou YS, Pinsky D, Stern D. Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9889–9897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Corica D, Aversa T, Ruggeri RM, Cristani M, Alibrandi A, Pepe G, De Luca F, Wasniewska M. Could AGE/RAGE-Related Oxidative Homeostasis Dysregulation Enhance Susceptibility to Pathogenesis of Cardio-Metabolic Complications in Childhood Obesity? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:426. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia B, Zhu R, Zhang H, Chen B, Liu Y, Dai X, Ye Z, Zhao D, Mo F, Gao S, Wang XD, Bromme D, Wang L, Wang X, Zhang D. Lycopene Improves Bone Quality and Regulates AGE/RAGE/NF-кB Signaling Pathway in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3697067. doi: 10.1155/2022/3697067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pereira ENGDS, Araujo BP, Rodrigues KL, Silvares RR, Martins CSM, Flores EEI, Fernandes-Santos C, Daliry A. Simvastatin Improves Microcirculatory Function in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Downregulates Oxidative and ALE-RAGE Stress. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14030716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]