Abstract

BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death, with high morbidity worldwide. There is an urgent need to find reliable diagnostic biomarkers of CRC and explore the underlying molecular mechanisms. Exosomes are involved in intercellular communication and participate in multiple pathological processes, serving as an important part of the tumor microenvironment.

AIM

To investigate the proteomic characteristics of CRC tumor-derived exosomes and to identify candidate exosomal protein markers for CRC.

METHODS

In this study, 10 patients over 50 years old who were diagnosed with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma were recruited. We paired CRC tissues and adjacent normal intestinal tissues (> 5 cm) to form the experimental and control groups. Purified exosomes were extracted separately from each tissue sample. Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry was implemented in 8 matched samples of exosomes to explore the proteomic expression profiles, and differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were screened by bioinformatics analysis. Promising exosomal proteins were verified using parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) analysis in 10 matched exosome samples.

RESULTS

A total of 1393 proteins were identified in the CRC tissue group, 1304 proteins were identified in the adjacent tissue group, and 283 proteins were significantly differentially expressed between them. Enrichment analysis revealed that DEPs were involved in multiple biological processes related to cytoskeleton construction, cell movement and migration, immune response, tumor growth and telomere metabolism, as well as ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion and mTOR signaling pathways. Six differentially expressed exosomal proteins (NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL and TRIM28) were validated by PRM analysis and evaluated by receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis. The area under the ROC curve was 0.93, 0.96, 0.97, 0.78, 0.75, and 0.88 (P < 0.05) for NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL, and TRIM28, respectively, indicating their good ability to distinguish CRC tissues from adjacent intestinal tissues.

CONCLUSION

In our study, comprehensive proteomic profiles were obtained for CRC tissue exosomes. Six exosomal proteins, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL and TRIM28, may be promising diagnostic markers and effective therapeutic targets for CRC, but further experimental investigation is needed.

Keywords: Exosomes, Colorectal cancer, Data-independent acquisition, Parallel reaction monitoring, Biomarker

Core Tip: We innovatively combined high-throughput quantitative proteomics analysis with colorectal cancer (CRC) tissue-originated exosomes. The comprehensive proteomic signature of CRC tissue exosomes was described using data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry, which revealed a mass of differentially expressed exosomal proteins. Six promising exosomal proteins, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL and TRIM28, were verified by parallel reaction monitoring analysis and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. The results indicated that these exosomal proteins could become potential diagnostic markers and effective therapeutic targets for CRC.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant tumors have become the leading cause of death in China[1], and over 4.8 million new cancer cases and approximately 3.2 million cancer deaths occurred in 2022[2]. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common malignant tumors and is a serious threat to human health[3]. In China, CRC is common among both sexes and has caused a great burden, with the incidence rate and mortality rate showing significant upward trends in recent years[4,5]. Statistics from 2020 revealed that the number of CRC cases in China accounted for 28.8% of the total newly diagnosed CRC cases and 30.6% of CRC-related deaths worldwide. The 5-year survival rate for CRC patients is closely associated with the stage of the tumor at initial diagnosis, more than 90% for patients diagnosed in the early stage and lower than 10% for patients diagnosed in the advanced stage[6]. Early detection of CRC is critical. The earlier the diagnosis is, the greater the treatment benefits for the patient. Moreover, it is essential to thoroughly elucidate the malignant biological mechanism of CRC so that novel therapeutic targets for individualized treatment can be identified.

Liquid biopsy is an emerging and booming technology that has been applied for early cancer screening, stratified therapy and posttreatment recurrence monitoring and can broadly be categorized by the ability to analyze circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA, or extracellular vesicles (EVs)[7]. Exosomes are a subclass of extracellular vesicles with a relatively small size (30-150 nm in diameter) that are rich in a variety of nucleic acids (RNA, DNA), proteins and lipids[8]. In contrast to the other two types, exosomes can be actively released into body fluids by tumor cells at any stage of tumor development. Exosomes were initially recognized as cellular waste expelled outside the cell. With the rapid development of exosome extraction technology and in-depth research, researchers have found that exosomes are an important component of the tumor microenvironment. Exosomes play a critical role in intercellular communication and widely participate in the pathological processes of tumors, including the induction of proliferation, stimulation of angiogenesis, promotion of migration, and suppression of apoptosis and immune escape. Therefore, exosomes could be further developed as promising biomarkers for tumor diagnosis, treatment and prognostic assessment[9].

Based on a search of domestic and international literature, among the contents of exosomes, researchers have shown great interest in proteins and miRNAs. Proteins are the basis of life activity, and various pathological states of the body are often accompanied by protein dysfunction. Benefitting from the advancement in high-throughput liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and the construction of related instruments to measure proteins, proteomics has become an indispensable and important tool for studying biological processes at the protein level[10]. In this study, we aimed to find potential novel biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of CRC. A total of 10 CRC patients were recruited, and exosomes from CRC tissues and paired healthy tissues adjacent to CRC tumors were isolated. We implemented data-independent acquisition (DIA) MS to obtain quantitative data, screened for significant differential proteins using bioinformatics analysis, and utilized parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) for further validation. In summary, our research comprehensively compared the protein profiles of exosomes from CRC tissues and adjacent normal tissues and identified differentially expressed exosomal proteins that might contribute to the further development of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for CRC in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics and clinical sample collection

This research was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital. Written informed consent forms were signed by all patients. Patients over 50 years old who were pathologically diagnosed with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma at the Department of General Surgery, China-Japan Friendship Hospital from January 2021 to October 2021 were recruited; five male patients and five female patients were eventually selected. Primary CRC tumor tissues and healthy tissues 5 cm adjacent to the cancer foci were collected simultaneously; the former was defined as group CT, and the latter was defined as group NT. All tissue specimens were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen after removal and stored at -80 °C for subsequent study. The patient information is summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Exosome isolation by size-exclusion chromatography

The protocols for exosome extraction from tissues were modified and optimized based on the methodology by Vella et al[11]. Tissues were sectioned into small slices, dissociated and then filtered through a 70 μm filter to remove the residues, producing original tissue homogenates. Next, we performed differential centrifugation to isolate EVs. In brief, tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 4 °C at 300 × g for 10 min, 2000 × g for 10 min, and 10000 × g for 20 min in sequence. The collected supernatants were filtered slowly and gently through a 0.22 μm filter to further remove cell debris before centrifugation at 4 °C at 150000 × g for 2 h. The exosome pellet was resuspended in PBS and further purified with Exosupur columns (Echobiotech, China). Fractions were concentrated using Amicon 100 kDa ultrafiltration tubes (Merck, Germany) to obtain purified exosomes, which were stored at -80 °C.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

The nanoparticle size and exosome concentration were measured with a ZetaView PMX 110 (Particle Metrix, Germany). A video was recorded with time duration of 90 s, and the rate of frames per second was 30. A laser source with a wavelength of 405 nm was used to irradiate the exosome suspension at 25 °C. The scattered light of the nanoparticles was detected, and the concentration was calculated by counting the scattered nanoparticles. Moreover, by tracking the Brownian motion trajectory of the nanoparticles, the mean-square displacement of the nanoparticles per unit time was acquired; as a result, the nanoparticle size distribution could be determined.

Transmission electron microscopy

Purified exosomes (10 μL) were placed onto carbon-coated copper grids, incubated at room temperature for 10 min, washed with sterile distilled water and then negatively stained with 10 μL of 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min. Samples were observed and imaged under an H-7650 electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from the exosomes, and the protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, United States). Next, we denatured the proteins by adding 5 × SDS loading buffer to the protein solution. For Western blotting, the protein samples were loaded into 10% SDS-PAGE gels for electrophoretic protein separation and then transferred to a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane at 300 mA for 2 h. Cell lysate was set as the positive control, and 10 μg of total protein from the control was used to detect each signature marker. For exosome samples, 30 μg of total protein was loaded to detect each signature marker. The membrane was blocked in 3% BSA-TBST at room temperature for 30 min and further incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-mouse CD9 (1:1000), anti-mouse CD63 (1:200), anti-rabbit HSP70 (1:1000), anti-rabbit TSG101 (1:1000) and anti-rabbit calnexin (1:500). We then incubated the membrane with the following secondary antibodies: anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (1:10000) or anti-mouse HRP-conjugated (1:10000) for 40 min at room temperature. The protein immunolabels were visualized and captured with a Tanon4600 automated chemiluminescence image analysis system (Tanon, China).

Peptide preparation for mass spectrometry

The purified exosome samples were ground into powders with liquid nitrogen and lysed in lysis buffer, followed by intermittent sonication with a metal probe on ice. After sufficient lysis, the lysate mixture was centrifuged at 12000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. We collected the supernatant and quantified the protein concentration using a BCA protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein samples were reduced with 5 mmol/L DTT at 37 °C for 1 h and then alkylated with 10 mmol/L iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark for 45 min. The protein samples were diluted with 25 mmol/L NH4HCO3 and then treated with trypsin at a ratio of 1:50 (trypsin:protein) overnight at 37 °C. The enzymatic digestion reaction was terminated by adding formic acid to adjust the pH to less than 3.0. We desalinated the digested peptides with C18 desalting columns, which were activated by 100% acetonitrile and equilibrated with 0.1% formic acid. The samples were loaded onto the desalting columns, washed with 0.1% formic acid to remove impurities, and eluted with 70% acetonitrile. Finally, we collected the eluates and freeze-dried the desalted samples for storage.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Equal amounts of peptides were taken from each sample and mixed. The mixed sample was fractionated on a Rigol L3000 HPLC system using a C18 column and monitored at a UV wavelength of 214 nm. Buffer A (2% acetonitrile, ammonium hydroxide, pH 10.0) and buffer B (98% acetonitrile, ammonium hydroxide, pH 10.0) were used as mobile phases with gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. The eluates were collected in tubes at one-minute intervals and combined into 6 fractions, which were then vacuum dried and stored for further analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using the EASY-nLC 1200 Liquid chromatography system (Thermo Scientific, United States) coupled with the Orbitrap Eclipse mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, United States) and a Nanospray Flex ion source. Buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) and buffer B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) were used as mobile phases. The dried fraction samples and peptide samples were redissolved in 10 µL of buffer A, mixed with 0.2 μL of standard peptides (iRT kit, Biognosys, Switzerland), and then loaded onto a C18 nanotrap column. Peptide separation was performed with an analytical column eluted with the following gradient program: the starting conditions (6% buffer B) were held for 8 min. Then, the content of buffer B was increased from 6%-12% in 8 min, 12%-30% in 55 min, 30%-40% in 12 min, and 40%-95% in 1 min, then held at 95% buffer B for 10 min. Lastly, the concentration of buffer B was decreased from 95%-6% in 1 min.

Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode was used to build a spectral library. The MS full scan ranged from m/z 350 to 1500 at a resolution of 120000. Automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 4e5, and the maximum injection time was 50 ms. Precursor ions were fragmented using high-energy collision cleavage (HCD). MS/MS scans were conducted in top speed mode with an AGC of 5e4, a maximum injection time of 22 ms and a normalized collision energy of 30%. For DIA acquisition, the MS full scan ranged from m/z 350 to 1500 at a resolution of 120000. The maximum injection time was set to 50 ms. The MS/MS scan was conducted in top speed mode with AGC in standard mode and the maximum injection time set in auto mode. The normalized collision energy was 30%[12,13].

The DDA and DIA raw data files were imported directly into Spectronaut software for spectral library construction and subsequent data extraction. The search parameters were set as follows: trypsin/P was used as the cleavage enzyme, the maximum number of missed cleavage sites was set as 2, carbamidomethyl on cysteine was selected as the fixed modification, and oxidation on methionine and acetyl was selected as the variable modification. Identified proteins were filtered with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 1%.

Bioinformatics analysis

Data visualization was achieved based on R software (version 3.6). A Venn diagram was constructed using VennDiagram. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess the distribution and variation of the samples, generated using ggbiplot. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were visualized with a column chart and volcano map using ggplot2. The clustering heatmap of DEPs was generated using pheatmap. The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) database was used for protein classification. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment was performed for protein functional annotation and analysis. COG and enrichment analyses were visualized with ggplot2. Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) were used to assess and measure the diagnostic power of the candidate proteins in distinguishing CRC tissues from normal intestinal tissues, and plots were created using pROC.

PRM

The DEPs screened from the previous LC-MS/MS analysis were further validated using PRM analysis to eliminate false-positive proteins[14]. The procedures of protein extraction, enzymatic digestion and desalination were the same as those for DDA/DIA. Gradient elution was performed at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min, then fractions were collected and combined into three fractions. PRM analysis was performed using an Orbitrap Q Exactive HFX mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, United States) at a flow rate of 600 nL/min. The gradient was 8%-12% buffer B in 5 min, 12%-30% in 30 min, 30%-40% in 9 min, and 40%-95% in 1 min and holding at 95% buffer B for 15 min. The MS full scan ranged from m/z 350 to 1500 at a resolution of 120000 with an AGC of 3e6 and a maximum injection time of 80 ms. The MS/MS scan was conducted at a resolution of 15000 with an AGC of 5e4 and a maximum injection time of 45 ms. The normalized collision energy of fragmentation was set to 27%. The raw data were assessed by Skyline software for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of candidate peptides.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from LC-MS/MS analysis were processed by median normalization (MDN). A paired t test was used to compare the data and identify DEPs between the CRC group and the control group. Fold change (FC) cutoffs > 1.2 or < 1/1.2 were applied for screening. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was processed by SPSS software (Version 26.0).

Survival analysis

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) was applied to analyze patient survival based on gene expression. The median gene expression was selected as the group cutoff to separate the high expression cohort and low expression cohort. The log-rank test was used to compare survival times between the two cohorts mentioned above, and Kaplan–Meier plots were applied to show the differences in overall survival (OS) and disease free survival (DFS) between the cohorts.

RESULTS

Study strategy

We performed DIA analysis to explore promising biomarkers and PRM analysis to verify candidate proteins. Due to the limitation of tissue sampling, a total of 10 patients were recruited for the research. We paired CRC tissues (n = 10) and corresponding normal tissues 5 cm apart (n = 10), forming the experimental and control groups. General information and detailed clinical data, including the TNM stage, are listed in Supplementary Table 1. DIA analysis was performed for 8 of the 10 patients, and data from all 10 were used for PRM validation. Exosomes from both groups were isolated and enriched. Then, after exosome lysis and protein digestion, peptides were obtained and analyzed using DIA mass spectrometry. Following bioinformatics analysis of the proteomic data, the screened DEPs between the CRC group and control group were further validated by PRM.

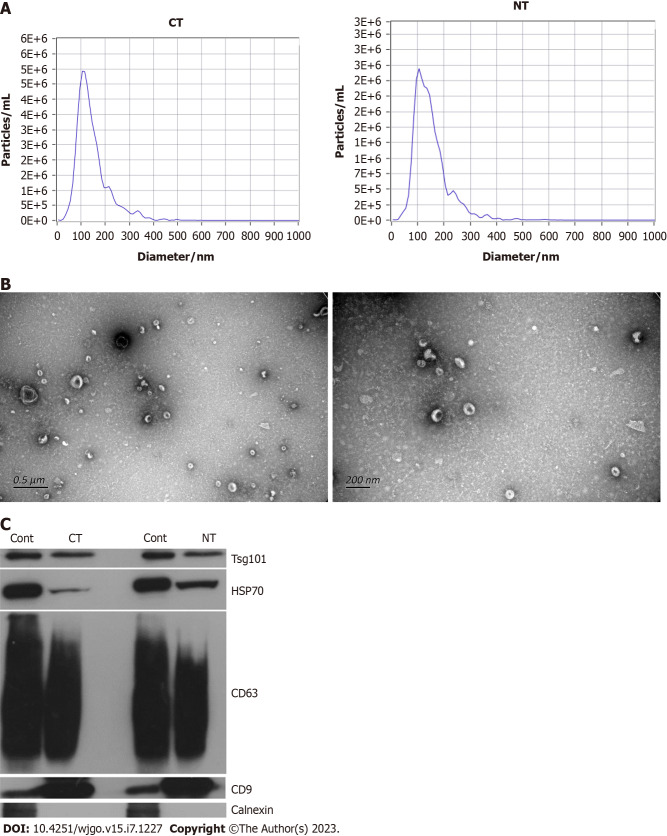

Characterization of the tissue exosomes

Exosomes were isolated from paired CRC tissues and adjacent healthy intestinal tissues. We determined the size distribution and particle concentration by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) analysis. The particle concentrations of the exosomes from the cancer tissues and adjacent tissues were 1.0E+11/mL and 1.1E+11/mL, respectively, with a very slight difference, as shown in Figure 1A. The results showed that exosomes derived from CRC tissues exhibited a mean size of 144.5 nm, and the mean size of the exosomes from the adjacent tissues was 148.3 nm (Figure 1A), which is consistent with the exosome size distribution. The morphology of the exosomes was visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 1B). The exosomes appeared cup- or round-like in shape by TEM, in accordance with typical exosome structures. Then, we detected the exosome-specific marker proteins TSG101, HSP70, CD9, CD63 and calnexin by Western blot analysis. A mixed cell lysate was used as a positive control. Figure 1C indicates that TSG101, HSP70, CD9 and CD63 exhibit high expression and that calnexin is absent, verifying the exosome isolation and concentration procedures. Characterization by NTA, TEM and Western blot analysis validated that the materials we extracted from the cancer tissues and adjacent tissues were of exosomal origin.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of tissue exosomes. A: Nanoparticle tracking analysis of colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; B: Transmission electron microscopy of normal intestinal exosomes observed at the scales of 0.5 μm and 200 μm; C: Western blot analysis of colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes, compared with the positive control. CT: Colorectal cancer tissues; NT: Normal intestinal tissues; Cont: Control.

Proteomic features of CRC tissue exosomes

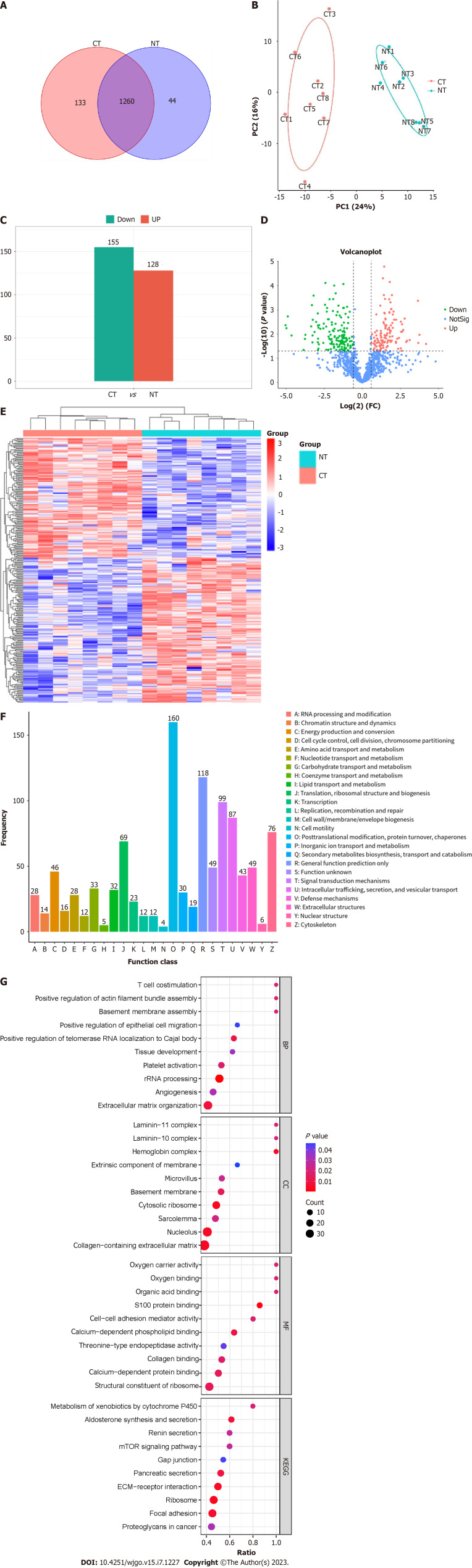

We performed label-free quantitative proteomics analysis with 8 paired samples to measure protein abundance and quantify protein expression. A total of 8425 peptides and 1565 proteins were initially screened in 8 CRC tissues and 8 paired normal intestinal tissues, and 1437 proteins were finally quantitatively detected. A total of 1393 proteins were identified in the CRC tissue group, 1304 proteins were identified in the adjacent healthy tissue group, and 1260 proteins were shared (Figure 2A). To better determine the connections and distinctions in all tissue samples, we performed global cluster analysis and PCA, as shown in Figure 2B. The protein expression profile of group CT was clearly distinguished from that of group NT. These results suggested that CRC tissue exosomes exhibit unique proteomic characteristics.

Figure 2.

Quantitative proteomic signature and bioinformatic analysis of colorectal cancer. A: The Venn diagram shows detected proteins in colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; B: Principal component analysis of colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; C: The bar chart shows 128 significantly upregulated proteins and 155 significantly downregulated proteins between colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; D: The volcano plot shows differentially expressed proteins between colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; E: The heat map shows differentially expressed proteins between colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; F: Clusters of Orthologous Groups analysis shows 25 categories constituted by all the detected exosomal proteins; G: Gene ontology analysis shows that differentially expressed proteins are involved in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions; Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes analysis shows that differentially expressed proteins are clustered in multiple pathways. CT: Colorectal cancer tissues; NT: Normal intestinal tissues; PC: Principal component; NotSig: COG: Clusters of Orthologous Groups; GO: Gene ontology; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes; ECM: Extracellular matrix.

To compare the DEPs between the CRC tissue group and adjacent normal intestinal tissue group, the screening criteria were set as follows: cutoff value of FC value larger than 1.2 or less than 1/1.2 and t test P value < 0.05. There were 283 proteins significantly differentially expressed in group CT samples compared to group NT samples, with 128 proteins significantly upregulated and 155 significantly downregulated (Figure 2C). The volcano plot in Figure 2D shows the overall differential exosomal protein expression profile between the CT samples and NT samples (FC > 1.2 or FC < 1/1.2, P value < 0.05). The 283 DEPs obtained from the two groups were subjected to cluster analysis (Figure 2E).

The COG database identified vertical homologous proteins and divided numerous proteins into a total of 26 different categories according to the similarity of the protein sequences. Each COG category represents a class of homologous proteins that descend from an ancestor and carry out the same function. In the current study, all the detected exosomal proteins constituted 25 COG categories, illustrated in detail with a bar chart in Figure 2F. Among all basic functions, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, signal transduction mechanisms, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport occupy a large proportion.

To further clarify the biological functions of the DEPs between CRC tissue exosomes and normal intestinal exosomes, GO annotation and enrichment analysis were performed at three levels, including molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP), for all 283 DEPs. Bubble diagrams were used to display partial significantly enriched pathways for the exosomal DEPs (P < 0.05, Figure 2G). Among them, the significantly enriched biological processes of the DEPs were extracellular matrix organization, angiogenesis, rRNA processing, platelet activation, tissue development, positive regulation of telomerase RNA localization to Cajal body, positive regulation of epithelial cell migration, basement membrane assembly, positive regulation of actin filament bundle assembly, and T cell costimulation. The clustered BP terms were principally related to the processes of cytoskeleton construction, cell movement and migration, immune response, tumor growth and telomere metabolism.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was then performed to further characterize the functional enrichment of DEPs. The results revealed that the pathways in which the DEPs between group CT and group NT were significantly enriched included those of ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, mTOR signaling pathway, proteoglycans in cancer, ribosome, pancreatic secretion, gap junctions, renin secretion, aldosterone synthesis and secretion, and metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450. The pathway of ECM-receptor interactions is of particular interest to our research, given the nature of exosomes in the tumor microenvironment[15]. Additionally, other pathways[16,17] that were found to be significant in our analysis are also relevant to the initiation and progression of CRC tumors.

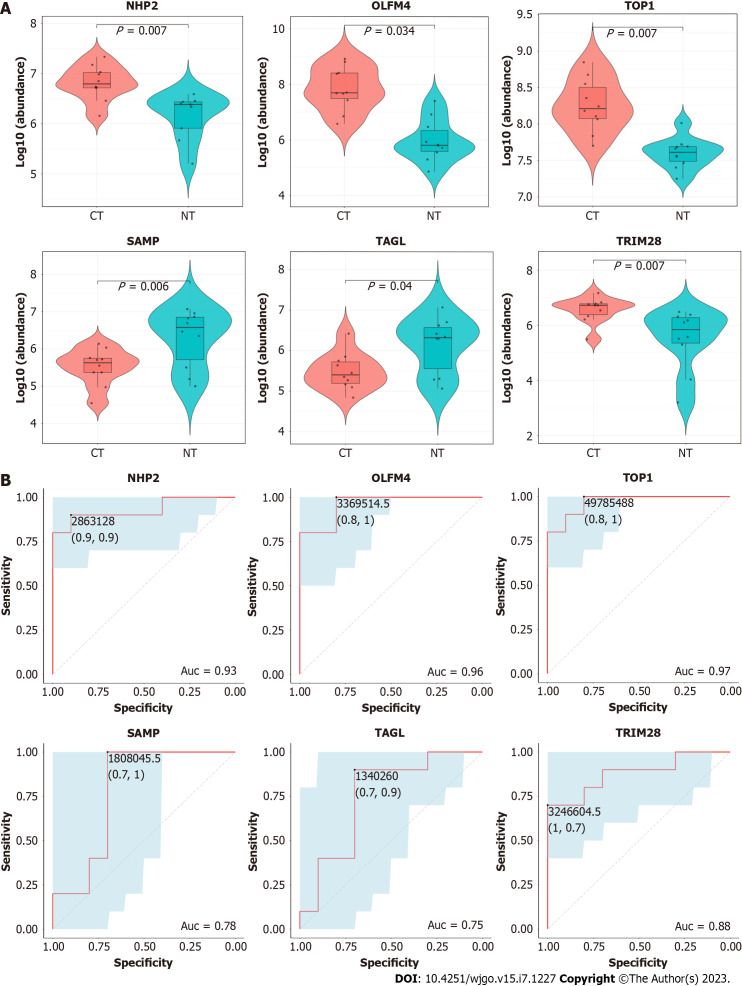

PRM validation of candidate proteins

To evaluate the authenticity of the DIA MS data, PRM was carried out with ten paired samples of CRC tissue and normal intestinal tissue (8 of which were identical to the DIA samples with an additional 2 new pairs). To screen candidate proteins for PRM validation, the filtration strategy was set as follows: the P value was screened from small to large; ROC analysis of DEPs was performed in 8 paired samples, and the AUC value needed to be greater than 80% (ROC analysis of candidates seen in Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, tumor-related literature in recent years was reviewed. Based on the above strategy and a brief literature review[18-20], we selected six DEPs of interest for qualification and validation. These proteins were as follows: H/ACA ribonucleoprotein complex subunit 2 (NHP2), olfactomedin-4 (OLFM4), DNA topoisomerase 1 (TOP1), serum amyloid P-component (SAMP), transgelin (TAGL), and tripartite motif-containing protein 28 (TRIM28). The expression levels of these proteins showed significant differences by PRM analysis, and the differential expression results from PRM were consistent with those from DIA. These data revealed that the following proteins were significantly upregulated in group CT compared to group NT: NHP2 (P = 0.007), OLFM4 (P = 0.034), TOP1 (P = 0.007), and TRIM28 (P = 0.007). In addition, the following proteins were significantly downregulated: SAMP (P = 0.006) and TAGL (P = 0.04) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Verification of candidate exosomal proteins. A: Parallel reaction monitoring analysis shows the upregulation of NHP2 (P = 0.007), OLFM4 (P = 0.034), TOP1 (P = 0.007), TRIM28 (P = 0.007), and the downregulation of SAMP (P = 0.006), TAGL(p=0.04) between colorectal cancer tissue exosomes and normal intestinal tissue exosomes; B: Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis shows that the area under curve of NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL, and TRIM28 are 0.93, 0.96, 0.97, 0.78, 0.75, 0.88, respectively (P < 0.05). CT: Colorectal cancer tissues; NT: Normal intestinal tissues; ROC: Receiver operating characteristic curve; AUC: Area under ROC curve; NHP2: H/ACA ribonucleoprotein complex subunit 2; OLFM4: Olfactomedin-4; TOP1: DNA topoisomerase 1; SAMP: Serum amyloid P-component; TAGL: Transgelin; TRIM28: Tripartite motif-containing protein 28.

Subsequently, we assessed the diagnostic power of these candidate proteins using ROC curves for all 10 paired samples. The AUC values of the six candidate proteins were NHP2 (AUC = 0.93), OLFM4 (AUC = 0.96), TOP1 (AUC = 0.97), SAMP (AUC = 0.78), TAGL (AUC = 0.75), and TRIM28 (AUC = 0.88). This result indicated that all candidates could easily distinguish CRC tissues from healthy tissues (Figure 3B).

Survival analysis

To investigate the relationship between candidate proteins and patient prognosis, OS and DFS were analyzed in the expression of genes corresponding to candidate proteins using GEPIA2. Except for the SAMP gene, prognosis-related data for the other five genes were found in the TCGA and GTEx databases. Survival analysis was carried out in the cohorts of a total of 270 CRC patients (Supplementary Figures 2-11). The analysis revealed that patients with high TAGL gene expression exhibited significantly decreased OS (P = 0.014) and significantly decreased DFS (P = 0.046), while patients with low TAGL gene expression showed a relatively good prognosis. The results for OS and DFS for the NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1 and TRIM28 genes showed no statistical significance (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The high morbidity and mortality of CRC are of concern. Early diagnosis of CRC can significantly improve patient prognosis and prolong survival time. Although there have been a number of studies focused on CRC, the exact molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Recently, the search for cancer biomarkers and exploration of pathogenesis have entered the era of multiomics, including genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics and proteomics[21]. Benefitting from objective and unbiased biomarker screening, high-throughput omics technologies provide a new perspective on the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of CRC. Proteomics is the best way to determine the physiological state of an organism. Through comprehensive protein and related functional profiling, proteomics clearly presents epigenetic information on and posttranslational modifications in CRC[22] and provides highly sensitive approaches for early tumor detection. Hundreds of clinical cohorts[23,24] have detected different proteomic signatures of CRC at different stages. With the support of the LC-MS/MS technique, DEPs are easy to identify and can serve as promising biomarkers for in-depth study as well as clinical application.

Proteomics has been carried out in different kinds of biological samples, such as serum, plasma, tissue, and feces; however, only a few studies have concentrated on the exosome level. Multiple studies have suggested that exosomes are closely related to the occurrence and development of tumors and play an important role in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor-derived exosomes can escape immune surveillance and mediate immune suppression[25], such as by carrying and releasing PD-L1 into the lymphatic system[26]. In addition, exosomes participate in cancer metastasis by regulating epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor angiogenesis and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling[27,28]. The contents and biological functions of exosomes remain to be explored, revealing a new direction to search for novel biomarkers and mechanisms of CRC at the exosome level. The strategy in our study was to directly obtain tissue specimens of CRC, rather than serum or plasma specimens, to acquire exosomes of definite tumor origin. Further experiments and analysis of CRC tissue-derived exosomes may provide a clearer understanding of CRC tumors.

In the present study, we identified 283 DEPs in CRC tissue exosomes compared to normal tissue exosomes and found that quite a few DEPs were involved in extracellular matrix organization. Moreover, focal adhesion and ECM-receptor interaction pathways were activated. These results suggest that exosomes may play a crucial role through the extracellular matrix. The ECM participates in the formation of the tumor microenvironment and regulates the processes of cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and invasion, as well as tissue morphogenesis[29]. As described in the results, the enrichment of DEPs involved in angiogenesis and tissue development apparently promoted tumor progression. The mTOR signaling pathway has been regarded as a significant regulatory mechanism of CRC. Other significantly enriched functions and pathways shown in this study are responsible for tumor development to a certain extent, which was consistent with what others have reported. Overexpression or activation of telomerase gives most cancer cells the ability to proliferate indefinitely, and telomerase activity is a key indicator for the early diagnosis of CRC and prognosis assessment[30]. Regulation of the abnormal immune response in CRC may become a potential target for immunotherapy[31]. In addition, we noticed that renin secretion as well as aldosterone synthesis and secretion were clustered in KEGG, which might be a clue regarding the activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Disorder of the latter is associated with poor prognosis of CRC, and accumulating evidence has demonstrated the therapeutic potential of these inhibitors in CRC[32].

Based on quantitative LC-MS/MS analysis, subsequent PRM verification and ROC measurements, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL and TRIM28 were recognized as critical cancer-promoting factors or cancer-suppressing factors with excellent diagnostic performance, making them promising diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets of CRC. TRIM28, which is also known as KRAB-associated protein 1 (KAP1) or transcription intermediary factor 1-beta (TIF1B), is a member of the tripartite motif (TRIM) family. TRIM28 has been reported to be aberrantly expressed in multiple types of cancer, such as lung, prostate, ovarian, breast, gastric and liver cancers, with its elevation in expression level typically correlated with aggressive clinical manifestation and poor OS[33-35]. Considered an oncogenic factor, TRIM28 plays an important role in tumorigenesis and progression[36]. Nevertheless, its expression level and pathogenesis in CRC remain unclear. In our study, TRIM28 was overexpressed in CRC tissue exosomes compared to adjacent healthy tissue exosomes. However, unfortunately, the expression level of the TRIM28 gene did not show prognostic relevance. Therefore, TRIM28 could be a potential target, although further experiments and perhaps larger samples are needed to explore its role in CRC. NHP2 is an indispensable component of the telomerase complex[37]. A previous study on CRC[18] reported that NHP2 expression was significantly associated with age, with high expression suggesting poor prognosis, and downregulating NHP2 inhibited the proliferation of CRC cells. OLFM4, also called GW112 or hGC-1, is highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract as a marker of intestinal stem cells. Previous studies have revealed that OLFM4 is upregulated in inflammatory bowel disease, gastric cancer, CRC, pancreatic cancer and gallbladder cancer[38]. This result suggested that OLFM4 is involved in anti-inflammation, cell adhesion, proliferation and apoptosis. TOP1 is a subclass of DNA topoisomerase enzymes that play a role in tumor pathogenesis by promoting DNA replication and cell division. TOP1 serves as an important target for anticancer therapy[39]. The TOP1 inhibitor irinotecan was developed years ago and has been among the first-line drugs in the treatment of advanced CRC. In addition to the above 4 upregulated proteins, there were two downregulated proteins in group CT vs group NT in the present study, namely, SAMP and TAGL. SAMP belongs to the pentraxin protein family and has been applied as a marker for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Recent research has implicated its good diagnostic efficacy in distinguishing Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis[40]. A preceding proteomic analysis[20] revealed that TAGL is downregulated in colon cancer tissues, similar to our results. However, other studies[41,42] have revealed that TAGL promotes tumor progression and invasion and is closely connected to a worse prognosis in advanced CRC, which is consistent with the present study. There is no definite evidence regarding TAGL at the exosome level, so its role in CRC tumorigenesis and development remains unclear, which provides a new area for further exploration.

In our study, high-throughput quantitative proteomics analysis and tissue-originated exosomes were innovatively combined. We comprehensively supplied valuable information on the proteomic characteristics of CRC tissue exosomes. The results provide a new and feasible perspective for future research on tissue exosomes. In vitro and in vivo experiments should be carried out to verify and further explore the definite mechanisms of tumor exosomal proteins that can be gradually translated to clinical applications from these laboratory data. Due to limitations caused by technical complexity and high costs, only 10 pairs of tissues were analyzed in this study. In the future, more matched samples and even single-cell omics could be included to reduce the impact of tumor heterogeneity and obtain more precise and valuable protein information.

CONCLUSION

In summary, comprehensive proteomic profiles of CRC tissues were described compared to normal tissues. The study provided proteomic evidence at the level of tissue exosomes as well as a foundation and direction for future research. Six exosomal proteins, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP, TAGL and TRIM28, were screened and identified and may be promising diagnostic biomarkers and effective therapeutic targets for CRC.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy in the world and has the second highest mortality rate. Early diagnosis can improve the prognosis of patients, so the search for biomarkers for CRC diagnosis is of clinical importance. Oncology research has entered the era of omics, in which proteomics is closely linked to the pathophysiological state of the human body, providing clear epigenetic information.

Research motivation

Although many studies have focused on CRC, the means of diagnosis and treatment have not improved significantly, and the specific molecular mechanisms of CRC remain unclear. Exploring the proteomic profile of CRC and searching for potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets is essential.

Research objectives

To comprehensively characterize the exosomal proteomic profile of CRC tissue and to search for promising exosomal proteins as diagnostic biomarkers for CRC.

Research methods

Exosomes were extracted from paired CRC tissues and paracancerous tissues for data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. Differentially expressed exosomal proteins were screened by bioinformatics analysis and validated by parallel reaction monitoring analysis. Receiver operating characteristic analysis and survival analysis were performed to detect the diagnostic ability and prognostic relevance of the candidate exosomal proteins.

Research results

The study identified 128 upregulated proteins and 155 downregulated proteins between CRC tissue exosomes and paracancerous tissue exosomes. Functional enrichment of proteins is closely associated with the extracellular matrix. The candidate exosomal proteins TRIM28, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP and TAGL could distinguish CRC tissues well from paracancerous tissues and are potential diagnostic biomarkers for CRC.

Research conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive exosomal proteomic characterization of CRC. The exosomal proteins TRIM28, NHP2, OLFM4, TOP1, SAMP and TAGL have the potential to be diagnostic biomarkers for CRC.

Research perspectives

Mining novel diagnostic biomarkers for CRC at the level of exosomes and proteomics to improve the detection rate of CRC.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital (No. 2018-116-K85).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 26, 2023

First decision: April 18, 2023

Article in press: May 25, 2023

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Belder N, Turkey S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ju JL

Contributor Information

Ge-Yu-Jia Zhou, Department of Gastroenterology, China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences), Beijing 100029, China; Graduate School, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Dong-Yan Zhao, Graduate School, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Teng-Fei Yin, Graduate School, Peking University China-Japan Friendship School of Clinical Medicine, Beijing 100029, China.

Qian-Qian Wang, Graduate School, Peking University China-Japan Friendship School of Clinical Medicine, Beijing 100029, China.

Yuan-Chen Zhou, Graduate School, Peking University China-Japan Friendship School of Clinical Medicine, Beijing 100029, China.

Shu-Kun Yao, Graduate School, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China; Department of Gastroenterology, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing 100029, China. shukunyao@126.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zou H, Li Z, Tian X, Ren Y. The top 5 causes of death in China from 2000 to 2017. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8119. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12256-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, Chen W. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:584–590. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei W, Zeng H, Zheng R, Zhang S, An L, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, Matsuda T, Bray F, He J. Cancer registration in China and its role in cancer prevention and control. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e342–e349. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl) 2021;134:783–791. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, Lu B, Luo C, Cai J, Lu M, Zhang Y, Chen H, Dai M. Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and screening of colorectal cancer: A comparison among China, Europe, and northern America. Cancer Lett. 2021;522:255–268. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu W, Hurley J, Roberts D, Chakrabortty SK, Enderle D, Noerholm M, Breakefield XO, Skog JK. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou B, Xu K, Zheng X, Chen T, Wang J, Song Y, Shao Y, Zheng S. Application of exosomes as liquid biopsy in clinical diagnosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:144. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He C, Zheng S, Luo Y, Wang B. Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics. 2018;8:237–255. doi: 10.7150/thno.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Wang W, Chen J. Recent progress in mass spectrometry proteomics for biomedical research. Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60:1093–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vella LJ, Scicluna BJ, Cheng L, Bawden EG, Masters CL, Ang CS, Willamson N, McLean C, Barnham KJ, Hill AF. A rigorous method to enrich for exosomes from brain tissue. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6:1348885. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1348885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillet LC, Navarro P, Tate S, Röst H, Selevsek N, Reiter L, Bonner R, Aebersold R. Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: a new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:O111.016717. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyring-Andersen B, Løvendorf MB, Coscia F, Santos A, Møller LBP, Colaço AR, Niu L, Bzorek M, Doll S, Andersen JL, Clark RA, Skov L, Teunissen MBM, Mann M. Spatially and cell-type resolved quantitative proteomic atlas of healthy human skin. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5587. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19383-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourmaud A, Gallien S, Domon B. Parallel reaction monitoring using quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer: Principle and applications. Proteomics. 2016;16:2146–2159. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Ren L, Li S, Li W, Zheng X, Yang Y, Fu W, Yi J, Wang J, Du G. The biology, function, and applications of exosomes in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:2783–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afzal O, Altamimi ASA, Mubeen B, Alzarea SI, Almalki WH, Al-Qahtani SD, Atiya EM, Al-Abbasi FA, Ali F, Ullah I, Nadeem MS, Kazmi I. mTOR as a Potential Target for the Treatment of Microbial Infections, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, and Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232012470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Chen J, Kuang Y, Cheng X, Deng M, Jiang Z, Hu X. A novel methylated cation channel TRPM4 inhibited colorectal cancer metastasis through Ca(2+)/Calpain-mediated proteolysis of FAK and suppression of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:5575–5590. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.70504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong Y, Liu Y, Wang T, Li Z, Gao L, Chen H, Shu Y, Li Y, Xu H, Zhou Z, Dai L. Age-Associated Proteomic Signatures and Potential Clinically Actionable Targets of Colorectal Cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2021;20:100115. doi: 10.1016/j.mcpro.2021.100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Praus F, Künstner A, Sauer T, Kohl M, Kern K, Deichmann S, Végvári Á, Keck T, Busch H, Habermann JK, Gemoll T. Panomics reveals patient individuality as the major driver of colorectal cancer progression. J Transl Med. 2023;21:41. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03855-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buttacavoli M, Albanese NN, Roz E, Pucci-Minafra I, Feo S, Cancemi P. Proteomic Profiling of Colon Cancer Tissues: Discovery of New Candidate Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21093096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ullah I, Yang L, Yin FT, Sun Y, Li XH, Li J, Wang XJ. Multi-Omics Approaches in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, Recent Updates and Future Perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/cancers14225545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalal N, Jalandra R, Sharma M, Prakash H, Makharia GK, Solanki PR, Singh R, Kumar A. Omics technologies for improved diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer: Technical advancement and major perspectives. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110648. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhardwaj M, Weigl K, Tikk K, Holland-Letz T, Schrotz-King P, Borchers CH, Brenner H. Multiplex quantitation of 270 plasma protein markers to identify a signature for early detection of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2020;127:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghazanfar S, Fatima I, Aslam M, Musharraf SG, Sherman NE, Moskaluk C, Fox JW, Akhtar MW, Sadaf S. Identification of actin beta-like 2 (ACTBL2) as novel, upregulated protein in colorectal cancer. J Proteomics. 2017;152:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiteside TL. Exosomes and tumor-mediated immune suppression. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1216–1223. doi: 10.1172/JCI81136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poggio M, Hu T, Pai CC, Chu B, Belair CD, Chang A, Montabana E, Lang UE, Fu Q, Fong L, Blelloch R. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell. 2019;177:414–427.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Sai B, Wang F, Wang L, Wang Y, Zheng L, Li G, Tang J, Xiang J. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3-induced EMT. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:40. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0959-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig N, Yerneni SS, Razzo BM, Whiteside TL. Exosomes from HNSCC Promote Angiogenesis through Reprogramming of Endothelial Cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:1798–1808. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y, Wang M, Zou Y, Jin L, Zhao Z, Liu Q, Wang S, Li J. Mechanisms of chemotherapeutic resistance and the application of targeted nanoparticles for enhanced chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20:371. doi: 10.1186/s12951-022-01586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao HY, He SM, Zhao CY, Wang Y, Sheng WJ, Zhen YS. Antitumor efficacy of a recombinant EGFR-targeted fusion protein conjugate that induces telomere shortening and telomerase downregulation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;226:1088–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia X, Mao Z, Wang W, Ma J, Tian J, Wang S, Yin K. Netrin-1 Promotes the Immunosuppressive Activity of MDSCs in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11:600–613. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabatabai E, Khazaei M, Parizadeh MR, Nouri M, Hassanian SM, Ferns GA, Rahmati M, Avan A. The Potential Therapeutic Value of Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28:71–76. doi: 10.2174/1381612827666211011113308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin JO, Lee GD, Nam SH, Lee TH, Kang DH, Yun JK, Lee PC. Sequential ubiquitination of p53 by TRIM28, RLIM, and MDM2 in lung tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:1790–1803. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00701-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong KW, Zhao JC, Song B, Zheng B, Yu J. TRIM28 protects TRIM24 from SPOP-mediated degradation and promotes prostate cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5007. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07475-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McAvera RM, Crawford LJ. TIF1 Proteins in Genome Stability and Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12082094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Tan S, Han Y, Huang L, Yang R, Hu Z, Tao Y, Oyang L, Lin J, Peng Q, Jiang X, Xu X, Xia L, Peng M, Wu N, Tang Y, Li X, Liao Q, Zhou Y. The role of tripartite motif-containing 28 in cancer progression and its therapeutic potentials. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1100134. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shay JW, Wright WE. Telomeres and telomerase: three decades of progress. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:299–309. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XY, Chen SH, Zhang YN, Xu CF. Olfactomedin-4 in digestive diseases: A mini-review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1881–1887. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i17.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talukdar A, Kundu B, Sarkar D, Goon S, Mondal MA. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: Challenges, progress and the road ahead. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;236:114304. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W, Wu L, Wu X, Li K, Li T, Xu B, Liu W. Combined analysis of serum SAP and PRSS2 for the differential diagnosis of CD and UC. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;514:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Zhang Y, Li Q, Wang Y. Transgelins: Cytoskeletal Associated Proteins Implicated in the Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:573859. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.573859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elsafadi M, Manikandan M, Almalki S, Mahmood A, Shinwari T, Vishnubalaji R, Mobarak M, Alfayez M, Aldahmash A, Kassem M, Alajez NM. Transgelin is a poor prognostic factor associated with advanced colorectal cancer (CRC) stage promoting tumor growth and migration in a TGFβ-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:341. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.