Abstract

Objective:

The passage of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and other subsequent restrictive immigration policies have created fear among Latino immigrants. This study examines whether fear of immigration enforcement is socially significant among older (50+ years) foreign-born Latino individuals in the United States without citizenship or permanent residence, and whether disapproval of immigrant enforcement policies is directly associated with fear of immigration enforcement among this older population.

Method:

Data used in the analysis come from 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2013 national Latino surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center. Cross-sectional regression models are used to estimate the probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement in the Latino samples, as well as to examine the association between disapproval and fear of immigration enforcement.

Results

The study finds that the predicted probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement among foreign-born individuals aged 50 and over without citizenship or permanent residence are not negligible. Moreover, the study finds evidence of a direct association between the disapproval of enforcement measures and fear of immigration enforcement. Discussion: Restrictive immigration measures have implications for conditions of fear and other stressors affecting the well-being of older immigrants.

Keywords: older Latino immigrants, fear of immigration enforcement, migration and health risks

Introduction

In this article, we examine whether fear of immigration enforcement among older Latino immigrants (aged 50 and over) is a relevant social issue in the context of restrictive immigration policies since the 1990s. Fear of immigration enforcement may have implications for the well-being of older migrants, given the findings of prior research that indicate widespread worry among Latino immigrants about deportations (e.g., see Lopez, Taylor, Funk, & Gonzalez-Barrera, 2013). Research has found that the enactment in 1996 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) has (a) placed migrants at greater risk for arrest, detention, and deportation, (b) created fear and tension among immigrants, (c) and restricted access to health care resources for some immigrants and their families (Hagan, Rodriguez, Capps, & Kibiri, 2003; Lopez et al., 2013; Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004).

Our theoretical perspective views migration as being more than the movement of individuals seeking economic gain. For many migrants, especially the undocumented, migration can be laden with dangers across the migratory spaces and during settlement in the new country. Many of the millions of undocumented Latinas and Latinos who have journeyed to the United States in the past few decades, for example, have faced physical and psychological health dangers, and even death, in encounters with criminal actors, corrupt police, and stringent enforcement policies during and after the migration (Donnelly & Hagan, 2014; Eschbach, Hagan, Rodriguez, Leon, & Bailey, 1999; Rodriguez, 2007). Moreover, some forced migrants travel with physical wounds or psychosocial trauma produced by violent events in their home countries (Arbona et al., 2010; Martin-Baro, 1989; Urrutia-Rojas & Rodriguez, 1997). From this perspective of health risks associated with migration, we join with other studies (e.g., Alarcón et al., 2016; Torres & Wallace, 2013) that seek to understand the health conditions and vulnerabilities of Latino immigrants associated with structural restrictions and dangers in the environments where migrants travel and settle. In this article, we address health risks and pressures brought to bear on older Latino immigrants by restrictive immigration policy.

Migrants older than 50 years constitute small percentages of immigrant populations. However, in the aggregate, they are large numbers of people who are mainly concentrated in immigrant communities, often in urban centers. Older immigrants are not necessarily persons who migrated at older ages. They also include persons who have aged in the seemingly permanent unauthorized population of an estimated 11.1 million immigrants in the country (Krogstad, Passel, & Cohn, 2016). The 11.1 million population of unauthorized migrants includes younger migrants who are aging into older migrants in highly precarious political and policy conditions. It is important to gain a sense of the population significance of 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants, of whom 52% are from Mexico (Krogstad et al., 2016). Eleven million people is roughly the population sizes of Rwanda, Somalia, and Haiti, and larger than the population sizes of Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and Uruguay. If the 11.1 million unauthorized migrants were a Central American country, they would be the second largest Central American country, second only to the Guatemalan population of 16.0 million (Population Reference Bureau, 2016).

Immigration Policy Background

For the greatest part of U.S. history, restrictive measures have characterized the immigration policies of the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Barred Zone Act of 1917, the National Origins Quota Act of 1924—all illustrate exclusionist tendencies of U.S. immigration policy (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2016). While the early history of the country’s development depended significantly on immigration for labor and businesses, not all national origins were equally accepted. Under immigration quota polices adopted in the 1920s, immigrants from northern and western Europe were favored, while immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were limited to much smaller numbers, and Asian immigration was banned altogether. To save a large part of its labor force from exclusion, agribusiness lobbied successfully to prevent the placing of Mexicans (and other Latin Americans) in the quota system (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2016).

It was not until 1965 that the U.S. government repealed the immigration quota system through amendments made to the Immigration and Nationality Act, which is the immigration statue of the country. The 1965 amendments introduced a new policy of preference categories based on family relationships and immigrant specialties as the means to regulate immigration. While unauthorized immigration surged primarily from Mexico after the 1964 termination of a labor importation program of temporary Mexican workers, in 1986 Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) to provide amnesty and legalization to unauthorized migrants who had lived continuously in the country for 5 years, for which 3.1 million immigrants applied (U.S. Department of Labor, 1992).

Congress again increased opportunities for immigration, and temporary legal presence in the United States, through the Immigration Act of 1990. This act increased the immigration cap from 270,000 to 675,000, created a visa lottery for 55,000 “diversity immigrants” annually, created new admission nonimmigrant categories for temporary workers, authorized the U.S. Attorney General to issue temporary protected status to undocumented migrants with deportation orders to countries experiencing social or natural calamities, and repealed measures to exclude immigrants and temporary migrants for political or ideological reasons (U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1997).

The passage of IIRIRA in 1996, however, dramatically reversed 25 years of congressional immigration legislation favorable to immigrants. Passed by Congress in the context of rising unauthorized immigration in the mid-1990s, IIRIRA provisions included (a) increasing the number of offenses for which noncitizen migrants could be deported, (b) making deportable offenses retroactive without limit, (c) drastically reducing the discretionary power of immigration judges to cancel deportation, (d) requiring mandatory detention for most deportable cases, and (e) changing the criterion for cancelation of deportation from the previous criterion of hardship to “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” for family members (Hagan, Eschbach, & Rodriguez, 2008). In addition, IIRIRA provided funding to elevate border enforcement, increase the number of Border Patrol agents, and construct physical barriers on the southwestern border. The pressure on immigrant communities increased with the passage of two additional laws in 1996 affecting immigrants and their families. PRWORA created restrictions of 5 years for new legal immigrants to participate in federally funded welfare support, and excluded unauthorized immigrants from welfare support altogether (Kullgren, 2003). The Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act strengthened the immigration enforcement power of the U.S. government by adding to IIRIRA’s new powers to reduce judicial review of deportation (Hagan et al., 2008). Clearly, the 1996 restrictive immigration policies renewed an immigrant enforcement intensity not seen since the massive government roundups of unauthorized migrants in the late 1940s and early 1950s, which terminated with Operation Wetback in 1954 (Hagan, Leal, & Rodriguez, 2015).

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, immigration became increasingly linked to national security, and not surprisingly subsequent congressional actions further elevated the enforcement power of the federal government. The USA PATRIOT Act passed in October 2001 increased the administrative power to detain and deport immigrants. The establishment of the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, included the Bureau of Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE), which was given the primary mission of enforcing the restrictive measures of IIRIRA. ICE became a national deportation police force that separated families and instilled fear and tension in immigrant communities throughout the country (Cardoso, Hamilton, Rodriguez, Eschbach, & Hagan, 2016; Dreby, 2010; Hagan et al., 2008; Menjívar, Abrego, & Schmalzbaur, 2016; Zayas, 2015).

Older Immigrants

International migrants are mostly young adult people (Lundquist, Anderton, & Yaukey, 2015). Consequently, relatively little is studied about older migrants, that is, individuals aged 50 and over. Older persons do not migrate as much as younger people for several reasons. They are ether past the prime of their income-earning years, or have retired and thus lessened their role as family providers. Yet, while older migrants do not constitute a major part of migrant streams, their presence is documented in studies of migration flows and they constitute significant numbers in immigrant populations.

The periodic migrant surveys (Encuestas Sobre Migracion en la Frontera Norte de México/EMIF) conducted by Mexican government and research agencies of Mexican migrants at the northern and southern borders of Mexico find sizable numbers of persons aged 50 and over migrating to the United States (Secretaría de Gobernación [SEGOB], 2013). The 2011 EMIF calculated that 87,507 persons aged 50 and over were part of the Mexican migrant stream of 317,105 headed to the United States that year, and estimates for 2013 give about 74,000 Mexican migrants aged 50 years and over headed to the United States. According to this survey, Mexican females aged 55 to 59 migrated more than the males of the same age cohort (SEGOB, 2013).

Concerning the immigrant population in the United States, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that among Latino immigrants, 21% were aged 55 and over in 2010–2014, and among Mexican immigrants 17% were in this age group (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). In 2013, the Migration Policy Institute reported that 663,600 (6%) of the 11.1 million unauthorized population in the United States were aged 55 and over (Capps, Fix, Van Hook, & Bachmeier, 2013).

As mentioned above, these sizable figures are not entirely due to the arrival of older migrants. The figures of older immigrants also represent the aging of immigrants residing in the country. A study by the Pew Research Center finds that the share of the unauthorized immigrant population that has been in the United States for 10 or more years is rising. In 2000, 35% of the unauthorized population had been in the country for 10 or more years, and, by 2012, 62% had been in the country for 10 or more years (Passel, Cohn, Krogstad, & Gonzalez-Barrera, 2014). Moreover, 21% had been in the United States for 20 years or more.

Concerning unauthorized immigrants, the hardening of border control has locked unauthorized immigrants inside the country who in earlier years of less rigid border enforcement would have returned home periodically (Massey, 2006). Consequently, every young unauthorized immigrant is a potential older immigrant if the unauthorized immigrant can avoid deportation. But survival from detection for deportation does not remove the stress and depression that can come from long-term separation from the family (Arbona et al., 2010).

Fear and Stress in Immigrant Populations

The implementation of immigration enforcement measures beginning in the mid-1990s brought sudden fear and stress to Latino immigrant populations (e.g., see Hagan, Rodriguez, & Castro, 2011; Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004; Salas, Ayón, & Gurrola, 2013). Even legal immigrants and U.S. citizens worried about negative impacts as the restrictive measures of IIRIRA and other new immigration legislation affected legal immigrants in addition to unauthorized migrants, and as IIRIRA indirectly affected U.S. citizens living in families with noncitizen immigrants in the United States. The sudden toughing of immigration law, and the new administrative regulations to arrest and detain more immigrants than ever before, contrasted sharply with the previous liberal immigration measures of the preceding two decades.

From 42% to 57% of U.S.- and foreign-born Latinos have reported worrying about deportation in national Latino surveys of the Pew Research Center in the years 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2013 (Pew Research Center, 2016). Not surprisingly, foreign-born Latinos report worrying about deportation in greater percentages than U.S.-born Latinos. The foreign-born category of Latinos contains noncitizen immigrants who are vulnerable to deportations, as only U.S. citizens are not deportable. Moreover, in 2013, the percentage of noncitizen Latinos who reported worrying “a lot” about deportations was 2.2 times greater than the percentage of foreign-born Latinos who are U.S. citizens, that is, 68% to 31%, respectively (Lopez et al., 2013).

Results of surveys of IIRIRA effects in five Texas cities, that is, El Paso, Hidalgo, Houston, Fort Worth, and Laredo, during 1997–1998, found immigrant communities in stress, and more so in the interior cities of Houston and Fort Worth than in the border sites of Laredo, Hidalgo, and El Paso where residents experience immigration enforcement as part of daily life given that the sites are in an international border zone (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004). The surveys of 100 interviews of Mexican-origin respondents in each of the five cities found immigrants shying away from health and medical facilities after the implementation of IIRIRA (Capps, Hagan, & Rodriguez, 2004; Hagan et al., 2003). In Houston and Fort Worth, health care workers reported that more immigrant women were having babies at home with midwives than before the passage of IIRIRA. In Houston, a mobile clinic director told of older Latinos changing their identity from the previous designation of “Hispanic” to “white” on medical intake forms. (Hagan et al., 2003).

The enactment of IIRIRA included more resources for enforcement resources, which increased the number of Border Patrol agents and immigration investigators. Consequently, federal immigration agents became more visible in communities, and according to reported statements the agents became more aggressive. In Houston, half of the respondents reported seeing more immigration agents involved in such activities as raids of day-laborer street corner pools and workplaces. A disproportionately larger percentage of respondents in the three border survey sites of Laredo, Hidalgo, and El Paso reported being stopped and questioned by Border Patrol agents than in the two interior sites of Houston and Fort Worth (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004).

Another study, a nonrandom survey on acculturative stress and psychological well-being conducted with 416 Mexican and Central American documented and undocumented immigrants in two major Texas cities, provided specific empirical measures of the degree of stress experienced in the environments of IIRIRA policy implementation (Arbona et al., 2010). Undocumented immigrant respondents reported greater difficulties with family separation than legal immigrants, but both undocumented and legal immigrants reported similar levels of fear of deportation, and only fear of deportation uniquely predicted acculturative stress related to carrying out both external and internal family functions (Arbona et al., 2010). Undocumented men reported significantly higher levels of fear of deportation than undocumented women, and 80% of undocumented migrants reported avoiding at least one activity (e.g., going to a public park) due to fear of deportation, while only 32% of legal immigrants gave a similar response. The authors of the acculturative stress study summarize their findings of immigration enforcement impacts as follows:

Fear of deportation, in addition to being a source of stress and anxiety, may discourage undocumented immigrants from seeking help for employment, health, and language skills difficulties they encounter . . . further compounding the stress they experience related to immigration-related challenges.

(Arbona et al., 2010, p. 377)

The participation of state and local police departments in immigration enforcement, which was first made possible by Section 287(g) of IIRIRA, added to the enforcement pressures facing Latino populations. Section 287(g) added another layer of immigration enforcement by providing federal training for state and local police departments that wanted to partner with federal immigration enforcement. In addition to the involvement of state and local police in immigration enforcement, state legislatures and local governments have passed many measures to restrict undocumented immigrants in their jurisdictions. In just 2010 and 2011, state legislatures passed 164 laws to restrict immigrants (Gordon & Raja, 2012). The combined weight of federal, state, and local measures placed great stress on immigrant populations, causing many immigrants to become fearful for the security and safety of their families (e.g., see Hagan et al., 2011; Hardy et al., 2012). Included in the immigrant families are older immigrants whose welfare can be affected by the threat of deportation or by the deportation of an income-earning household member.

Enactments of new restrictive laws are invariably passed with the assertion that the measures protect the economic health and security of jurisdictions (e.g., see U.S. Department of Homeland Security [U.S. DHS], 2015, 2017), even when research is not offered to support the claim. The policy makers do not consider consequent effects of the enacted measures on the mental health conditions of families, including small children, torn apart by apprehensions and deportations (Zayas, 2015).

Older immigrants, especially Latino immigrants, may be more vulnerable to the stress of heightened immigration enforcement. One study using a national representative sample of 7,345 older persons in the United States has found that elderly immigrants report “poorer physical and mental health outcomes than non-immigrant elderly,” in contrast to the well-established Hispanic Paradox (Lum & Vanderaa, 2010, p. 750). Research also indicates that less acculturated elderly Hispanics are more likely to be depressed than more acculturated elderly immigrants (Mui & Kang, 2006), and thus fear of heightened enforcement can add to an already problematic mental health condition, although the relationship between acculturation and mental health among immigrants has not been clearly established (Lum & Vanderaa, 2010).

According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, the political context and public policy directly and indirectly influence health by affecting social conditions through which the structural determinants of health function (WHO, 2008). Using this WHO perspective, a study conducted with 1,493 Latino respondents found that respondents who worried that a friend or family member could be deported were 1.6 times more likely (p < .01) than respondents who did not have a similar worry to respond needing to seek help for emotional problems of anxiety, sadness, or nervousness, after controlling for individual variables (Vargas, Sanchez, & Juárez, 2017). Moreover, Latino respondents who viewed their state as having an anti-immigrant environment were also 1.6 times (p < .05) more likely to say they needed to look for help to deal with anxiety, sadness, or nervousness (Vargas et al., 2017).

Research Focus

In the analysis below, we examine whether the fear of immigration enforcement is socially significant among older foreign-born individuals without citizenship or legal permanent residence. It is reasonable to expect that fear of immigration enforcement among older immigrants is lower compared to the fear of younger immigrants, who are likely more exposed to enforcement measures at work, or less experienced in avoiding these measures. Nevertheless, lower fear of immigration enforcement may not be negligible among older immigrants. Fear of immigration enforcement can restrict access to health care resources as some migrants worry about detection or apprehension if they try to access health care in public agencies (Hagan et al., 2003). This fear also may have a negative impact on the well-being and quality of life of older immigrants (Becerra, Quijano, Wagaman, Cimino, & Blanchard, 2015).

In this article, we also examine whether the disapproval of immigrant enforcement policies is directly associated with fear of immigration enforcement. This hypothesized association would indicate whether the disapproval of immigration policies—another possible determinant of health and wellbeing (Vargas et al., 2017)—crystallizes in fear.

Data and Method

The data used in this analysis come from the Pew Research Center: the 2007, 2008, and 2010 rounds of the Pew National Survey of Latinos and the 2013 Pew Survey of Hispanics. These annual telephone surveys include adult Latino respondents residing in the United States with a telephone (either landline or cellular phone). Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish. Overall response rates were low (below 50%). However, these surveys are still informative of Latinos in the United States due to their unique questions about disapproval and fear of immigration enforcement, and U.S. Citizen and permanent residence status. In this study, we used cross-sectional regression models to estimate the probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement among foreign-born individuals without citizenship or legal permanent residence by age group as well as the association between disapproval and fear of immigration enforcement. We applied sampling weights to these surveys to obtain nationally representative profiles of Latino adults in the United States.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable measures whether respondents are afraid of immigration enforcement. Particularly useful in our analysis is a question included in every year of the Pew National Survey of Latinos about fear of deportation (Lopez et al., 2013). The question reads,

Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported? Would you say that you worry a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

We created a binary dependent variable by collapsing options “a lot” and “some,” and options “not much” and “not at all.”

Independent Variables

We created binary variables for age by collapsing individuals aged 18 to 29, 30 to 49, 50 to 64, and 65 and over. We also created a binary variable for U.S. citizens and permanent residents using the questions “Were you born on the island of Puerto Rico, in the United States, or in another country?” “Are you a citizen of the United States?” and “Earlier you said you are not a citizen of the U.S. Do you have a green card or have you been approved for one?” This variable distinguishes U.S. citizens and permanent residents (individuals with green cards) versus individuals who do not have these statuses.

Moreover, we created binary variables that indicate whether respondents disapprove of immigration enforcement measures. These variables refer to respondents that at least disapprove of one of the immigration enforcement questions mentioned below included in the questionnaire every year. We used the questions as follows: From the Pew survey of Latinos in 2007, 2008 and 2010 we used, “Do you approve or disapprove of workplace raids to discourage employers from hiring undocumented or illegal immigrants?,” from the 2007 survey we used, “Do you approve or disapprove of states checking for immigration status before issuing driver’s licenses?,” from the 2008 survey we used, “Do you approve or disapprove of a requirement that employers check with a federal government database to verify the legal immigration status of any job applicant they are considering hiring?,” as well as, “Do you approve or disapprove of the criminal prosecution of employers who hire undocumented immigrants?,”from the 2010 survey we used, “Do you approve or disapprove building more fences on the nation’s borders,” and “Do you approve or disapprove increasing the number of border patrol agents,” and from the 2013 Pew Hispanic survey we used, “Please tell me if you approve or disapprove increasing enforcement of immigration laws at U.S. borders.” We acknowledge that these questions likely capture distinct dimensions of disapproval of immigration enforcement. Nonetheless, we opted to create yearly binary variables due to our choice of methods.

In addition, we included several control variables to account for the potential influence of unobserved confounding variables. We added a binary variable that indicates whether respondents have children under 18 living in their households (except in the 2013 survey). Adults with young dependents are likely more afraid than adults with no dependents, especially if parents and children are undocumented (Salas et al., 2013). Moreover, we included a binary variable that measures whether respondents lived in the United States 10 years or more (only significant in 2013), and a binary variable that indicates whether Spanish is the dominant language of the respondent as measures of acculturation (Lum & Vanderaa, 2010). The Spanish dominant variable is not the same in every year. This variable was created using an aggregated proficiency measure included in the survey, which was obtained with different questions about language use in 2007 and 2010. These questions were not included in the 2008 and 2013 Pew Latino surveys. Instead, we used language spoken during the interview as a proxy for Spanish dominant. Furthermore, we added binary variables for human and material capital: educational attainment (high school or less, some college or technical school, and college degree or more) and household income (less than US$30,000, US$30,000 to less than US$50,000, and US$50,000 or more). We also added binary variables for region (Northeast, North Central, South, and West).1

Analytic Plan

In this study, we used two different cross-sectional regression models for binary dependent variables. We used seemingly unrelated bivariate probit regression models to examine whether there is evidence of reverse causation between disapproval and fear of immigration enforcement. These recursive simultaneous equations models with correlated errors are useful to predict together disapproval and fear of immigration enforcement using bivariate dependent variables (Greene, 2003). We created binary variables for disapproval of immigration enforcement—the dependent variables of the second equations—because of this methodological choice under the assumption that these variables capture at least certain aspects of disapproval of immigration enforcement. We found evidence of significant correlations between the errors of the equations in the 2008 and 2010 Pew surveys. However, we found no evidence of significant correlations between the errors for 2007 and 2013. Alternatively, we fitted logistic regression models predicting fear of immigration enforcement, and treated disapproval of immigration enforcement as an exogenous variable in the 2007 and 2013 Pew surveys.

We opted to fit cross-sectional regression models instead of pooling the data because the variables for disapproval of immigration enforcement and Spanish as a primary language are not the same over the years. We chose the regression models presented in Table 1 after comparing each model with alternative regression models fitted with the same yearly data using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).2 These yearly differences in data characteristics likely account for our different model specifications by year (see Table 1). We are particularly interested in estimating the probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement among foreign-born individuals without citizenship or legal permanent residence by age group, and in examining whether the association between fear and different measures of disapproval of immigration enforcement is positive and significant.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics (Weighted Percentages) for the Variables Used in the Analysis.

| 2007 (n= 1,979) |

2008 (n= 1,988) |

2010 (n= 1,342) |

2013 (n=693) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of immigration enforcementa | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

|

| ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18 to 29 | 14.51 | 15.61 | 11.80 | 18.73 | 14.63 | 15.37 | 15.27 | 14.73 |

| 30 to 49 | 18.63 | 24.49 | 17.95 | 24.98 | 18.30 | 25.60 | 21.33 | 21.24 |

| 50 to 64 | 6.87 | 8.18 | 8.47 | 6.52 | 9.18 | 8.13 | 10.61 | 6.47 |

| 65 and over | 6.52 | 5.19 | 6.41 | 5.15 | 5.08 | 3.72 | 6.35 | 4.00 |

| Do not disapprove immigration enforcement | ||||||||

| Measures | 13.91 | 5.48 | 10.62 | 3.81 | 10.01 | 3.02 | 41.97 | 31.34 |

| Disapprove immigration enforcement measuresb | 32.63 | 47.99 | 34.01 | 51.56 | 37.18 | 49.80 | 11.59 | 15.10 |

| Not a U.S. citizen/permanent resident | 4.37 | 14.69 | 3.38 | 16.57 | 2.76 | 13.18 | 8.48 | 24.09 |

| U.S. citizen and permanent resident | 42.16 | 38.77 | 41.25 | 38.81 | 44.43 | 39.63 | 45.07 | 22.35 |

| No children under 18 living in household | 26.70 | 23.82 | 26.55 | 25.49 | 26.80 | 23.27 | Unavailable | |

| Children under 18 Living in Household | 19.83 | 29.65 | 18.08 | 29.89 | 20.38 | 29.55 | ||

| Spanish is not a primary language | 36.18 | 24.02 | 32.64 | 17.99 | 37.32 | 24.67 | 38.79 | 19.92 |

| Spanish as a primary languagec | 10.35 | 29.44 | 11.99 | 37.39 | 9.86 | 28.14 | 14.76 | 26.53 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 7.68 | 7.03 | 7.91 | 6.51 | 7.00 | 7.35 | 8.30 | 6.50 |

| North Central | 3.45 | 4.12 | 3.83 | 3.87 | 4.00 | 3.61 | 4.77 | 3.39 |

| South | 16.05 | 20.41 | 16.92 | 19.97 | 18.17 | 19.09 | 17.78 | 17.89 |

| West | 19.36 | 21.90 | 15.98 | 25.03 | 18.01 | 22.76 | 22.71 | 18.67 |

| Did not live in the United States 10 years or more | 5.19 | 13.77 | 3.72 | 15.56 | 2.67 | 8.95 | 4.62 | 5.59 |

| Lived in the United States 10 years or mored | 15.70 | 27.32 | 14.80 | 27.26 | 15.67 | 29.71 | 17.14 | 26.17 |

| Educational attainmentd | ||||||||

| High school or less | 27.45 | 39.69 | 23.34 | 43.23 | 25.30 | 38.01 | 28.97 | 34.80 |

| Some college, technical school | 10.46 | 9.05 | 12.79 | 6.59 | 14.18 | 9.51 | 15.70 | 7.73 |

| College degree or more | 7.38 | 3.18 | 7.06 | 3.35 | 7.31 | 4.86 | 8.89 | 3.92 |

| Incomed | ||||||||

| Less than US$30,000 | 19.15 | 29.37 | 16.87 | 33.55 | 15.65 | 25.63 | Unavailable | |

| US$30,000 to less than US$50,000 | 7.38 | 9.92 | 7.37 | 8.75 | 9.49 | 8.98 | ||

| US$50,000 or more | 12.34 | 5.36 | 12.45 | 3.77 | 12.41 | 6.27 | ||

Note. The sum of the percentages of all the categories of each variable equals 100% except when indicated. This table also includes the percentages of variables that were not included in every regression analysis.

We collapsed options “not at all” and “not much” (category “No” in the table), and options “some” and “a lot” (category “Yes” in the table).

This variable is not the same in every year. It is a binary variable that includes different measures each year (see the “Data and Method” section).

This variable is not the same in every year. It is a variable based on a set of questions about language use in the 2007 and 2010 analyses. We used language spoken during the interview as a proxy for Spanish dominant in the 2008 and 2013 analyses.

The sum of the percentages of all the categories of these variables does not equal 100% due to the omitted category “missing values,” except in educational attainment in 2013 (one missing value removed for the analysis).

Results

Table 1 presents weighted percentages of the variables used in the analyses. As the table shows, individuals aged 30 to 49 are overall more afraid of immigration enforcement, except in 2013 (no difference). Except in 2008 and 2013, individuals aged 18 to 29 are slightly more afraid of immigration enforcement. These descriptive results match our initial expectation: Fear of immigration enforcement is relatively higher among younger immigrants. Differences in fear of immigration enforcement among other age groups are not as great in magnitude.

Table 2 presents selected coefficients of cross-sectional regression models predicting fear of immigration enforcement. We found some evidence of significant (and marginally significant) differences in fear of immigration enforcement by age group (noteworthy in 2010 and 2013), as well as significant (and marginally significant) coefficients of interaction terms between age and disapproval of immigration enforcement (noteworthy in 2008 and 2010). Overall, these findings follow the logic of our original expectations: Younger adults are more afraid of immigration enforcement compared to older immigrants. Younger adults are possibly more afraid because they are likely more exposed to these measures, or less experienced in avoiding these measures.

Table 2.

Selected Coefficients of Cross-Sectional Regression Models Predicting Fear of Immigration Enforcement.

| Variables |

2007 |

2008 |

2010 |

2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression model | Logistic | Bivariate probit | Bivariate probit | Logistic |

|

| ||||

| Agea | ||||

| 30 to 49 | −0.059 (0.15) | 0.225 (0.23) | −0.467* (0.24) | 0.633* (0.29) |

| 50 to 64 | 0.143 (0.19) | 0.376 (0.25) | −0.725* (0.33) | −0.703* (0.35) |

| 65 and over | −0.418† (0.23) | 0.229 (0.27) | −0.110 (0.15) | −0.862* (0.34) |

| Aged 30 to 49 × Disapprove Immigration Enforcement Measures | - | −0.389 (0.25) | 0.587* (0.24) | — |

| Aged 50 to 64 × Disapprove Immigration Enforcement Measures | - | −0.854** (0.27) | — | — |

| Aged 65 and Over × Disapprove Immigration Enforcement Measures | — | −0.539† (0.28) | - | - |

| Disapprove Immigration Enforcement Measuresb (Reference: Approve these measures) | 0.904*** (0.17) | 2.175*** (0.25) | 1.752*** (0.20) | 0.509† (0.26) |

| U.S. citizen and permanent resident (Reference: Not a U.S. citizen/permanent resident) | −0.542** (0.17) | −0.339*** (0.10) | −0.562*** (0.14) | −1.610*** (0.31) |

| Aged SO to 64 × U.S. Citizen and Permanent Resident | — | — | 0.600† (0.33) | — |

| Children under 18 Living in Household (Reference: No children living in household) | 0.429** (0.13) | 0.209** (0.08) | — | Unavailable |

| Spanish as a primary languagec (Reference: Spanish is not the primary language) | 1.013*** (0.13) | 0.617*** (0.09) | 0.399*** (0.11) | — |

| Regiond | ||||

| Northeast | — | −0.291** (0.11) | — | — |

| North Central | — | −0.127 (0.17) | — | — |

| South | — | 0.021 (0.08) | — | — |

| Lived in the United States 10 years or moree (Reference: Less than 10 Years) | — | — | — | 0.955* (0.39) |

| Educational attainmentf | ||||

| Some college, technical school | −0.160 (0.16) | — | — | −0.548* (0.27) |

| College degree or more | −0.640*** (0.19) | — | — | −0.507 (0.35) |

| Incomeg | ||||

| US$30,000 to less than US$50,000 | 0.238 (0.18) | −0.091 (0.1 1) | −0.225* (0.1 1) | Unavailable |

| US$50,000 or more | −0.494** (0.19) | −0.355** (0.12) | −0.375** (0.12) | |

| Intercept | −0.532* (0.27) | −1.590*** (0.26) | −0.970*** (0.24) | 0.850* (0.37) |

| n | 1,979 | 1,988 | 1,342 | 693 |

Note. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Dashes indicate that variables were not included in the model because they were statistically insignificant. We only present the coefficients of the first equations in the 2008 and 2010 analyses. We used age, U.S. citizen/permanent resident, region, Spanish as a primary language, educational attainment, and income as regressors that predicted the disapproval of immigration enforcement measures in 2008 (second equation). Moreover, we used age, Spanish as a primary language, U.S. citizen/permanent resident, and have a partner (versus married, widowed, divorced, separated, never married) as regressors that predicted the disapproval of immigration enforcement in 2010 (second equation).

Reference: Aged 18 to 29.

This variable is not the same in every year. It is a binary variable that includes different measures each year (see the “Data and Method” section).

This variable is not the same in every year. It is a variable based on a set of questions about language use in the 2007 and 2010 analyses. We used language spoken during the interview as a proxy for Spanish dominant in the 2008 and 2013 analyses.

Reference: West.

Estimated coefficient of category “missing values” is omitted from the table.

Reference: High School or Less. Estimated coefficient of category “missing values” is omitted from the table except in the 2013 model (one missing value removed for the 2013 analysis).

Reference: Less than US$30,000. Estimated coefficient of category “missing values” is omitted from the table.

p < . 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

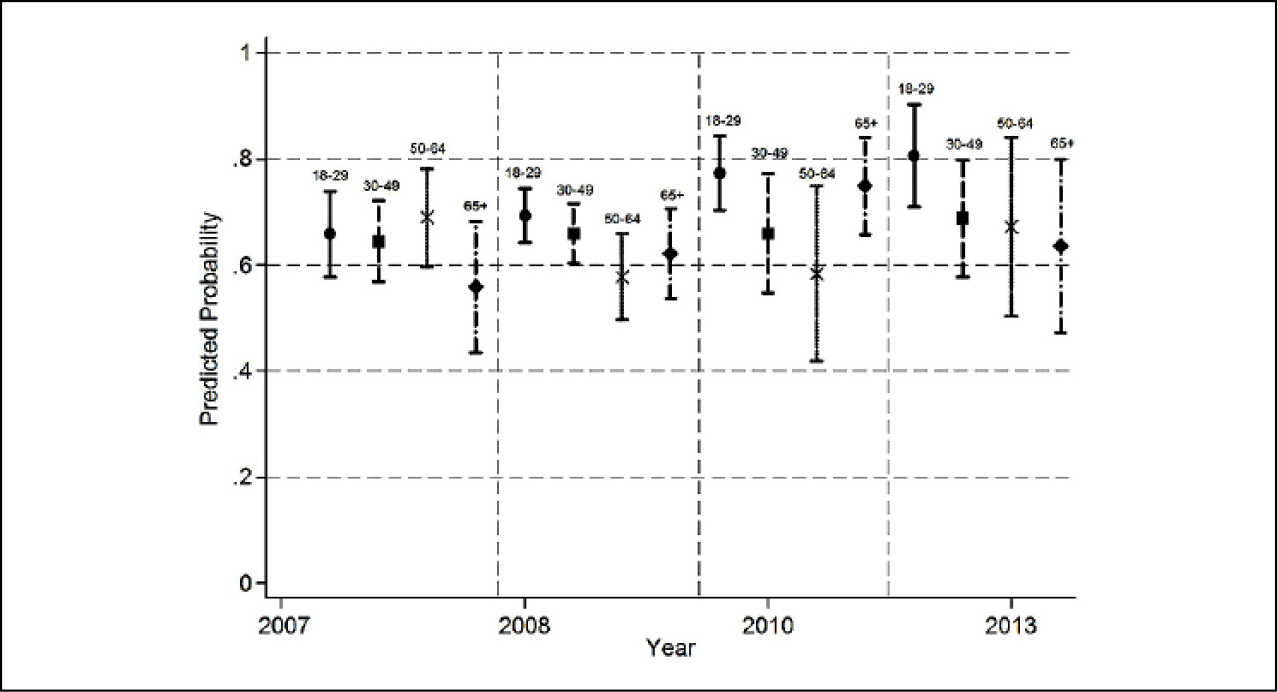

Regardless of these differences, the predicted probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement by age group among foreign-born individuals without citizenship or permanent residence, depicted in Figure 1, are noteworthy. In 2007, for instance, the probability of fearing immigration enforcement of foreign-born individuals without citizenship or permanent residence is .56 for individuals aged 65 and over. In 2008 and 2010, these probabilities are .58 for individuals aged 50 to 64. In 2007, the probability of fearing immigration enforcement of foreign-born individuals without citizenship or permanent residence is .56 for individuals aged 65 and over. These are the lowest predicted probabilities.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of fearing immigration enforcement by age among foreign-born individuals without citizenship or permanent residence.

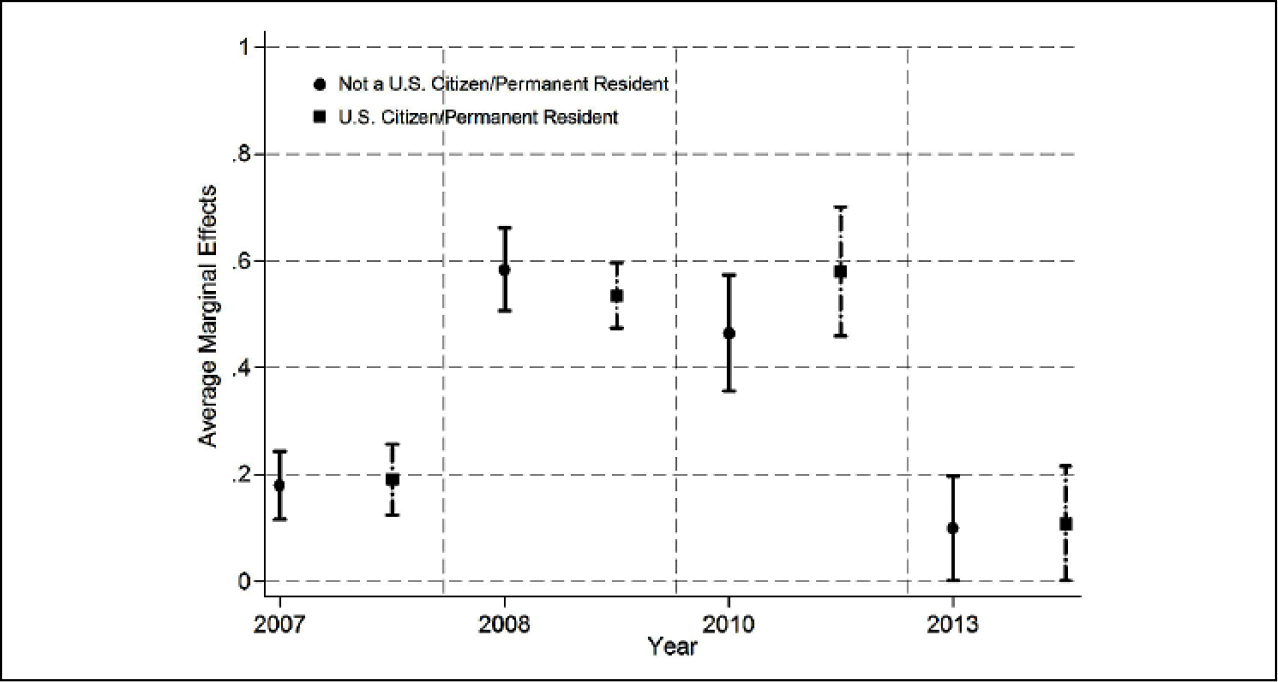

Moreover, we found evidence of a direct association between the disapproval of different immigration enforcement measures (by year) and fear of immigration enforcement. This association is positive and significant (marginally significant in 2013) even when we found evidence of reverse causation (using the 2008 and 2010 data). This association suggests that the disapproval of enforcement likely contributes to the crystallization of fear. Although the coefficients presented in Table 2 are useful to identify whether the associations of the independent variables and fear of immigration enforcement are positive or negative, they are not comparable in magnitude. Alternatively, Figure 2 depicts the average marginal effects of the disapproval of different immigration enforcement measures (by year) on fear of immigration enforcement. These estimates vary by year, and are notably higher in the 2008 and 2010 bivariate probit models. These variations reveal how these yearly different variables likely refer to different dimensions of disapproval of immigration enforcement.

Figure 2.

Average marginal effects of different measures of disapproval of immigration enforcement on fearing immigration enforcement by citizenship/permanent residence status.

Limitations

A key limitation of the analysis is that nonresponse could have biased the estimates presented due to the low response rates of the Pew Latino surveys in 2007, 2008, 2010 and 2013. This is a common challenge for contemporary telephone survey research due to the growing unwillingness of the public to participate in these surveys. However, several studies point out that nonresponse does not necessary introduce substantial biases into the analyses (Keeter, Kennedy, Dimock, Best, & Craighill, 2006; Massey & Tourangeau, 2013; Oropesa, Landale, & Hillemeier, 2016; Pew Research Center, 2012). Furthermore, it is necessary to point out that the significant coefficients in our regression models only suggest meaningful associations between fear of immigration enforcement and the independent variables. These results do not support specific explanations about the direction of the association (the causal nature of the association).

In addition, the regression models presented in Table 2 do not have the same specification each year. In certain cases, we did not include the variable in the final model according to the BIC. In other cases, we did not include the variable because it was not available for a specific year. Similarly, the data do not offer the same variables for disapproval of immigration enforcement every year. Regardless of these limitations, our goal was to take advantage of the available data to point out that fear of immigration enforcement is also noteworthy among older immigrants without citizenship or legal permanent residence.

Discussion

The probabilities of fear of immigration enforcement among foreign-born individuals presented in this study reveal that, regardless of significant differences by age, older Latino immigrants are afraid of immigration enforcement. Consequently, it is necessary to build on recent studies on health and immigration (e.g., Becerra et al., 2015; Vargas et al., 2017) and analyze whether fear of immigration enforcement has a distinct and significant impact on the health and well-being of older undocumented Latino immigrants. Empirical examinations of this topic will require that health surveys of immigrants include questions that measure fear of immigration enforcement, and differentiate individuals with U.S. citizen and legal permanent residence status. The operationalization of the variable fear of immigration enforcement should include behavioral measures (e.g., “Have you stopped doing certain activities to reduce possible detection by the authorities?” and “How often do you talk about immigration enforcement with friends or family members?”). In addition, efforts should be made to include and perhaps even oversample immigrant respondents without citizenship or visas in health surveys.

It also would be useful to gather data on disapproval of immigration enforcement. Disapproval may have a direct impact on the health and wellbeing of immigrants as well as an indirect effect mediated by fear of immigration enforcement. Evidence of the impact of disapproval on well-being would serve to problematize and challenge anti-immigrant policies, and the discourses and beliefs that support these policies. It would be preferable to use several questions in surveys to gather data for the creation of scales keeping in mind that the disapproval of immigration enforcement is likely multidimensional.

Increased Risk for Older Immigrants

Fear of immigration enforcement is a logical outcome of the implementation of IIRIRA given that this law raised annual deportations from about 50,000 in 1995 to more than 400,000 by 2012 (U.S. DHS, 2016, Table 39). IIRIRA especially increased the risk of deportation for older migrants through its retroactive measure of making deportations applicable to immigration violations that occurred even before its enactment in 1996 and through its reclassification of many previously nondeportable offenses to aggregated felonies, which are grounds for removal. Through these new measures, many noncitizen legal immigrants in their sixties, seventies, and older faced deportation for offenses they committed and pled guilty to decades earlier at a time when the offenses were not deportable. Some migrants pled guilty in plea deals in which they were sentenced to probation with no jail time, and some of these cases involved getting arrested for small amounts of marijuana (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004). The IIRIRA-impact survey in the five Texas cities received family reports of losing elderly family members to deportations to Mexico decades after the deported family member had completed serving sentences for offenses (Rodriguez & Hagan, 2004).

According to recent data (Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, 2016), as a category immigrants aged 50 and over account for only 5% of deportations, but in absolute numbers they have numbered between 13,000 and 16,000 annually, and hundreds of these elderly deportees have been age 70 and older. The numbers of older immigrants at risk of deportation because they have unauthorized status in the United States will remain substantial and likely grow as the unauthorized immigrant population of some 11.1 million continues to age. From our theoretical perspective, this population will age with risks to mental health as enforcement becomes more aggressive under the Trump administration (U.S. DHS, 2017).

Risk of being deported is not the only IIRIRA-related threat to the security of many older migrants. The removal of other members of a family, especially income earners, can affect the stability of the rest of the household, including older immigrants. Research conducted among deported immigrants in El Salvador in 2002 found that among the sample of 300 deported immigrants 25% had lived in multigenerational households with some arrangements involving older migrants, for example, parents, aunts, or uncles (Hagan et al., 2008). Among the deported immigrants who had lived in the United States for over 5 years, 70% had lived in households with members of an older generation.

Deportation of a family household member can have a serious impact on older immigrants should they depend on the family household for survival. The sharply rising numbers of deportations to more than 400,000 by 2012 (U.S. DHS, 2016, Table 39), involves large numbers of immigrants that are important sources of social capital for their families and communities. Analysis of the sample of 300 deported migrants in El Salvador found that many had been key sources of social capital needed to help connect families and communities to mainstream institutions (Hagan et al., 2008). A third of the sample had settled in the United States for more than 10 years, and among these 67% had legal status in the United States when arrested, 64% were fluent in English, 94% had been employed, and 74% had incomes ranging from US$14,400 to more than US$46,000 per year (Hagan et al., 2008). The deportation of immigrants with substantial levels of social capital thus creates “collateral damage” for families and communities left behind (Hagan et al., 2015).

The question may be raised why older migrants do not return to their home country if they are facing problematic and restrictive policy situations in the United States. The EMIF surveys in Mexico find that at least a quarter of the returning migrants are age 50 or older, and the majority of these are males. While Mexico does not have a vastly improved economy with abundant chances for upward social mobility and prosperity, it does appear to offer social and economic alternatives to living in the United States under enforcement pressures (Wheatley, 2017). The same is not true for most countries in Central America, particularly El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Populations in these Central American countries face daily problems with violent crimes and restricted chances for economic prosperity, thus, for many Central American immigrants in the United States, returning to their home countries is not a favorable alternative to stressful enforcement conditions in the United States (International Crisis Group, 2016; United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees, 2015).

Restrictions for Health Care Access

Given that migrants tend to be young and that foreign-born Latinos are often reported to have favorable health conditions (Vega, Rodriguez, & Gruskin, 2009), the argument could be made that access to health care should not be a major issue regarding older members of Latino immigrant populations. The Legalized Population Survey administered in 1989 among former unauthorized migrants enables a view of health care usage among the older Mexican immigrants, that is, those aged 50 and over (U.S. Department of Labor, 1989). Only 8% of the 149 Mexican immigrants aged 50 and over in the sample reported having been hospitalized in the year prior to the survey. Ten different reasons were given for being hospitalized, with “treatment for long-term illness” receiving the highest frequency with three respondents. When the 149 Mexican immigrants aged 50 and over were asked about their usual place for health or medical care in the United States before applying for amnesty and legalization, only two responses registered more than 10% of the subsample: doctor’s office or a private clinic (43%) and never used health care services in the United States (28%). Hospital outpatient clinics and community family health centers ranked third place with 7% each, although 11% of the female respondents cited community family health centers as their usual place for health care (U.S. Department of Labor, 1989). These findings suggest that, while older unauthorized immigrants do not have a high rate of health care usage, they have not completely disappeared from the health care sector. Moreover, their numbers are likely to grow as age cohorts in the long-term unauthorized immigrant population continue to advance through the life course in the United States.

In the study of IIRIRA impacts in five Texas cities, community health directors and survey respondents reported that immigrants feared health care providers would share information with police and immigration officials, and that this fear kept many immigrants away from public health care services, including legal immigrants who lived in mixed-status households with unauthorized immigrant family members (Hagan et al., 2003). This fear was not unfounded. In several cases, public hospitals did attempt to share information of immigrant patients with federal officials, as this information was seen by hospital staff as useful for the Department of State and the Immigration service to determine immigration eligibility and to determine whether an immigrant had become a public charge, which are grounds for denial of citizenship. In El Paso, one public hospital shared a list with the U.S. consular office in Ciudad Juárez in Mexico of immigrants who had received medical services without paying for them (Hagan et al., 2003). In Houston, a public hospital official offered a printout to visiting Immigration service officials of persons who had not paid for medical services they received at the hospital and thus were considered unauthorized immigrants.

An investigation by a team of legal and immigration experts and immigrant advocates in 1998 revealed many cases across the country where immigrants had gone without much-needed medical attention because they feared being reported by health facilities as a public charge to federal officials and consequently expelled from the country or restricted from future citizenship (Schlosberg & Wiley, 1998). In the 2000s, concerns for the ethics of health care facilities grew to include hospital deportations, that is, cases where hospitals took the initiative to repatriate poor, nonpaying patients to their countries with or without the consent of the patients. After hundreds of such cases were reported, in 2014, The New England Journal of Medicine published an article, “Undocumented Injustice? Medical Repatriations and the End of Health Care,” to examine a new ethical problem in immigrant health care (Young & Lehmann, 2014). This collective research supports our findings and argument that migrants encounter health risks and restrictions within the context of policy enforcement, including through actions undertaken by health care agencies not charged with enforcement.

Two cases of medical emergency of immigrants in Houston observed by two of the coauthors of this article illustrate how not having medical insurance and being an unauthorized immigrant can delay seeking medical care to the point of near death. In one case, Guatemalan brothers of a young immigrant man passing blood from advanced stomach cancer offered to pay cash to a highly reputable hospital for his medical care, but the hospital insisted that their brother needed to have health insurance to be admitted for treatment. The brothers then took the ill brother to a charity hospital where they were told a bed was not available. Feeling dejected and suffering in pain the young immigrant decided to return to Guatemala, where he died shortly after arriving.

In the second case, an unauthorized immigrant daughter from Mexico finally managed to gain the attention of community nurses to help her immigrant mother who was stricken in bed suffering from an advanced stage of spinal cancer. Because the mother was an unauthorized immigrant without insurance needing acute care, the nurses felt she had few or no chances of being admitted by a large county public hospital already overcrowded with poor patients. Instead, the nurses helped her get admitted into a small suburban hospital from where she was then transferred to the county hospital through an emergency room entrance, bypassing the restrictive, intake screening at the main entrance. The mother spent a lengthy spell receiving treatment at the hospital, but finally returned to Mexico with very little expectation of survival.

These two cases represent drastic situations in which being an immigrant and not having health insurance, or having unauthorized status, restricted prompt access to critically needed medical care. The time lost in seeking hospital care because of fear or lack of access to health care probably would not have made a difference for the final outcomes of the two immigrants given the seriousness of their illnesses, but pain medication and other relief could have provided some comfort in their acute conditions.

Conclusion

We opened this presentation with the theoretical perspective that international migration transpires across social and policy conditions that produce health risks for many immigrants, especially for undocumented Latino migrants. Most evident in this regard is the U.S. border policy of redirecting unauthorized border crossers at the southwest border to desolate areas, costing the lives of thousands of migrants who have perished from heat exposure or other dangers in the deserts since the 1990s (De León, 2015; Eschbach et al., 1999). The health risks of migration do not just affect the young, who make up the largest numbers of migrants; pressures and risks of immigration enforcement also impact older immigrants. Older Latino immigrants residing in the United States also fear the possibility of deportation, but at lower levels than younger immigrants. As described above, older immigrants constitute approximately one fifth of all foreign-born in the country, one third of all Latino immigrants, and over 660,000 of the 11.1 million unauthorized population in the country. The replenishment of immigration from Latin America, along with the aging of America’s immigrant population, reproduces the age cohorts of older Latino immigrants in the country.

Restrictive immigration measures enacted since the 1990s have created an atmosphere of distress in which many immigrants live precarious lives fearing for the security of themselves and their families. In these environments, immigrants and their families curtail family activity, sometimes withdrawing from needed institutional assistance, such in health care, for fear that they could be apprehended and deported or cause the deportation of a family member (Hagan et al., 2003). Moreover, many immigrant families live with the stress and anxiety of not knowing what the future will bring regarding family security, a situation that will become more precarious as the Trump administration increases enforcement activity.

Restrictive immigration policies pressure aging Latino immigrant populations, and within these population older immigrants can face considerable stress. The stress can come from being a dependent in an immigrant family and thus being at risk of having an income earner in the family deported. In this situation, older immigrants who are not U.S. citizens may advance into their later years not looking forward to a comfortable retirement, but to the possibility of family separation or even a forced repatriation to the country of origin, where in some cases few close relatives remain, as some family members may be residing in the United States.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We also controlled for sex (female), marital status, and other measures for time living in the United States in alternative regression models not presented in this study. The coefficients of these variables were statistically insignificant.

Differences between values of these model-fit statistics are useful to find the model that receives most support from the data. Lower values of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) with at least a different of six indicate better fit (Fox, 2008).

References

- Alarcón RD, Parekh A, Wainberg ML, Duarte CS, Araya R, & Oquendo MA (2016). Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3, 860–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, & Wiesner M (2010). Predictors of acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32, 362–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra D, Quijano LM, Wagaman MA, Cimino A, & Blanchard KN (2015). How immigration enforcement affects the lives of older Latinos in the United States. Journal of Poverty, 19, 357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Fix M, Van Hook J, & Bachmeier JD (2013). A demographic, socioeconomic, and health coverage profile of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/demographic-socioeconomic-and-health-cover-age-profile-unauthorized-immigrants-united-states [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Hagan J, & Rodriguez N (2004). Implementing immigration and welfare reform in Texas. In Kretsedemas P & Aparicio A (Eds.), Immigrants, welfare reform, and the poverty of policy (pp. 229–249). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JB, Hamilton ER, Rodriguez N, Eschbach K, & Hagan J (2016). Deporting fathers: Involuntary transnational families and intent to remigrate among Salvadoran deportees. International Migration Review, 50, 197–230. [Google Scholar]

- De León J (2015). The land of open graves: Living and dying on the migrant trail. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly R, & Hagan JM (2014). Dangerous journeys. In Lorentzen LA (Ed.), Hidden lives and human rights: Understanding the controversies and tragedies in undocumented immigration (pp. 71–106). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J (2010). Divided by borders: Mexican migrants and their children. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K, Hagan J, Rodriguez N, Leon RH, & Bailey S (1999). Death at the border. International Migration Review, 33, 430–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J (2008). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon I, & Raja T (2012, March/April). 164 anti-immigration laws passed since 2010? A MoJo analysis. Mother Jones. Retrieved from http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/03/anti-immigration-law-database

- Greene WH (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Eschbach K, & Rodriguez N (2008). U. S. deportation policy, family separation, and circular migration. International Migration Review, 42, 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Leal D, & Rodriguez N (2015). Deporting social capital: Implications for immigrant communities in the United States. Migration Studies, 3, 370–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Rodriguez N, Capps R, & Kibiri N (2003). The effects of recent welfare and immigration reforms on immigrants’ access to health care. International Migration Review, 37, 444–463. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Rodriguez N, & Castro B (2011). Social effects of mass deportations by the United States government, 2000–2010. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34, 1374–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, & Henley E (2012). A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1250–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Crisis Group. (2016). Easy prey: Criminal violence and central American migration (Latin America Report N°57). Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/057-easy-prey-criminal-violence-and-central-american-migration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Keeter S, Kennedy C, Dimock M, Best J, & Craighill P (2006). Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a National RDD Telephone Survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70, 759–779. [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, Passel JS, & Cohn D (2016). 5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/03/5-facts-about-illegal-immigration-in-the-u-s/ [Google Scholar]

- Kullgren JT (2003). Restrictions on undocumented immigrants’ access to health services: The public health implications of welfare reform. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1630–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Taylor P, Funk C, & Gonzalez-Barrera A (2013). Views about unauthorized immigrants and deportation worries. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/12/18/3-views-about-unauthorized-immigrants-and-deportation-worries/ [Google Scholar]

- Lum TY, & Vanderaa JP (2010). Health disparities among immigrant and nonimmigrant elders: The association of acculturation and education. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 12, 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist JH, Anderton DL, & Yaukey D (2015). Demography: The study of human population (4th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Baro I (1989). Political violence and war as causes of psychological trauma in El Salvador. Journal of La Raza Studies, 2, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS (2006, April 4). The wall that keeps illegal workers in. The New York Times, The Opinion Pages. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/04/opinion/the-wall-that-keeps-illegal-workers-in.html [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, & Tourangeau R (2013). Where do we go from here? Nonresponse and social measurement. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645, 222–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, Abrego LJ, & Schmalzbaur LC (2016). Immigrant families. Malden, MA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mui AC, & Kang S-Y (2006). Acculturation stress and depression among Asian immigrant elders. Social Work, 51, 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS, & Hillemeier MM (2016). Legal status and health care: Mexican-origin children in California, 2001–2014. Population Research and Policy Review, 35, 651–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D, Krogstad JM, & Gonzalez-Barrera A (2014). As growth stalls, unauthorized immigrant population becomes more settled. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/09/03/as-growth-stalls-unauthorized-immigrant-population-becomes-more-settled/ [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2012). Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2016). Datasets: National survey of Latinos, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/category/datasets/ [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. (2016). 2016 world population data sheet. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/pdf16/prb-wpds2016-web-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N (2007). Mexican and central Americans in the present wave of U.S. immigration. In Falconi JL & Mazzoti JA (Eds.), The other Latinos: Central and South Americans in the United States (pp. 81–100). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, & Hagan J (2004). Fractured families and communities: Effects of immigration reform in Texas, Mexico and El Salvador. Latino Studies, 2, 328–351. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, & Hagan J (2016). US policies to restrict immigration. In Leal D & Rodriguez N (Eds.), Migration in an era of restriction (pp. 27–38). Basel, Switzerland: Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- Salas LM, Ayón C, & Gurrola M (2013). Estamos Traumados: The effect of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg C, & Wiley D (1998). The impact of INS public charge determinations on immigrant access to health care. Los Angeles, CA: National Health Law Program. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Gobernación (Ministry of the Interior). (2013). Encuestas Sobre la Migracion en las Fronteras Norte de Mexico, 2011. Retrieved from https://www.colef.mx/emif/resultados/publicaciones/publicacionesnte/pubnte/EMIF%20NORTE%202011.pdf

- Torres JM, & Wallace SP (2013). Migration circumstances, psychological distress, and self-rated physical health for Latino immigrants in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 1619–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. (2016). ICE deportation: Gender, age, and country of citizenship. New York, NY: Syracuse University. Retrieved from http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/350/ [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. (2015). Women on the run: First-hand accounts of refugees fleeing El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Washington, DC: The UN Refugee Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia-Rojas X, & Rodriguez N (1997). Unaccompanied migrant children from central America: Sociodemographic characteristics and experiences with potentially traumatic events. In Ugalde A & Cardenas G (Eds.), Health and social services among international labor migrants: A comparative perspective (pp. 151–166). Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). 2014 American Community Survey (ACS), 5-year estimates. Washington, DC: American Fact Finder. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2015). Priority enforcement program—How DHS is focusing on deporting felons. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/blog/2015/07/30/priority-enforcement-program-–-how-dhs-focusing-deporting-felons [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2016). 2014 yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_yb_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2017). Enforcement of the immigration laws to serve the national interests (Memorandum). Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/17_0220_S1_Enforcement-of-the-Immigration-Laws-to-Serve-the-National-Interest.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. (1989). The Legalized Population Survey. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu/LPS/LPSpage.htm [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. (1992). Immigration Reform and Control Act: Report of the Legalized Alien Population. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002590134 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. (1997). 1995 statistical yearbook of the immigration and naturalization service. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, & Juárez M (2017). Fear by association: Perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 42, 459–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega W, Rodriguez MA, & Gruskin E (2009). Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiologic Reviews, 31, 99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley C (2017). Driven “home”: Stories of voluntary and involuntary reasons for return among migrants in Jalisco and Oaxaca, Mexico. In Roberts B, Menjívar C, & Rodriguez N (Eds.), Deportation and return in a border-restricted world: Experiences in Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (pp. 67–86). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health). Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43943/1/9789241563703_eng.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Young MJ, & Lehmann LS (2014). Undocumented injustice? Medical repatriation and the ends of health care. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas L (2015). Forgotten citizens: Deportation, children, and the making of American exiles and orphans. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]