Condensation.

Certain adverse childhood events are associated with greater symptom severity and worse health-related quality of life among women undergoing hysterectomy for uterine leiomyoma

Keywords: Fibroids, gynecological health, minority health, health disparities, psychosocial stress

Objective

Epidemiologic research suggests that psychosocial stress may increase fibroid risk,1, 2 but associations with symptom severity, which often influence clinical management decisions, have been underexamined. Our objective is to examine associations between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and symptom severity and symptom impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL) among women undergoing hysterectomy for treatment of their leiomyomas (fibroids).

Study Design

We recruited and consented 103 women from 2018–2021 into the Fibroids, Observational Research on Genes and the Environment (FORGE) study3 who were seeking evaluation of fibroids at the Medical Faculty Associates in Washington D.C. Eligible women were nonpregnant, premenopausal, ≥ 18 years of age, and intending to undergo hysterectomy at the George Washington University Hospital. Presence of fibroids was confirmed by pathology reports. GW Institutional Review Board approved the study. Participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. For exposure classification, we used an ACE module consisting of eight ACE categories related to child abuse and household challenges.4 Questions referred to experiences within the first 18 years of life. Responses were binary. We summed ACE categories to create a cumulative score (range 0–8); a higher score indicated greater exposure. For outcome classification, we used the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) 37-item questionnaire assessing the severity of symptoms and impact of symptoms on six HRQL categories for women undergoing surgery for fibroids.5 The five-level Likert scale responses were summed to create composite scores and standardized to a 0–100 scale; a lower symptom severity score indicated fewer symptoms, while a higher HRQL score indicated better quality of life. We ran quasi-poisson regressions (log-link) to examine associations between ACE scores and UFS-QOL composite scores adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and education (N=89). Statistical significance was set at the two-sided alpha of 0.05.

Results

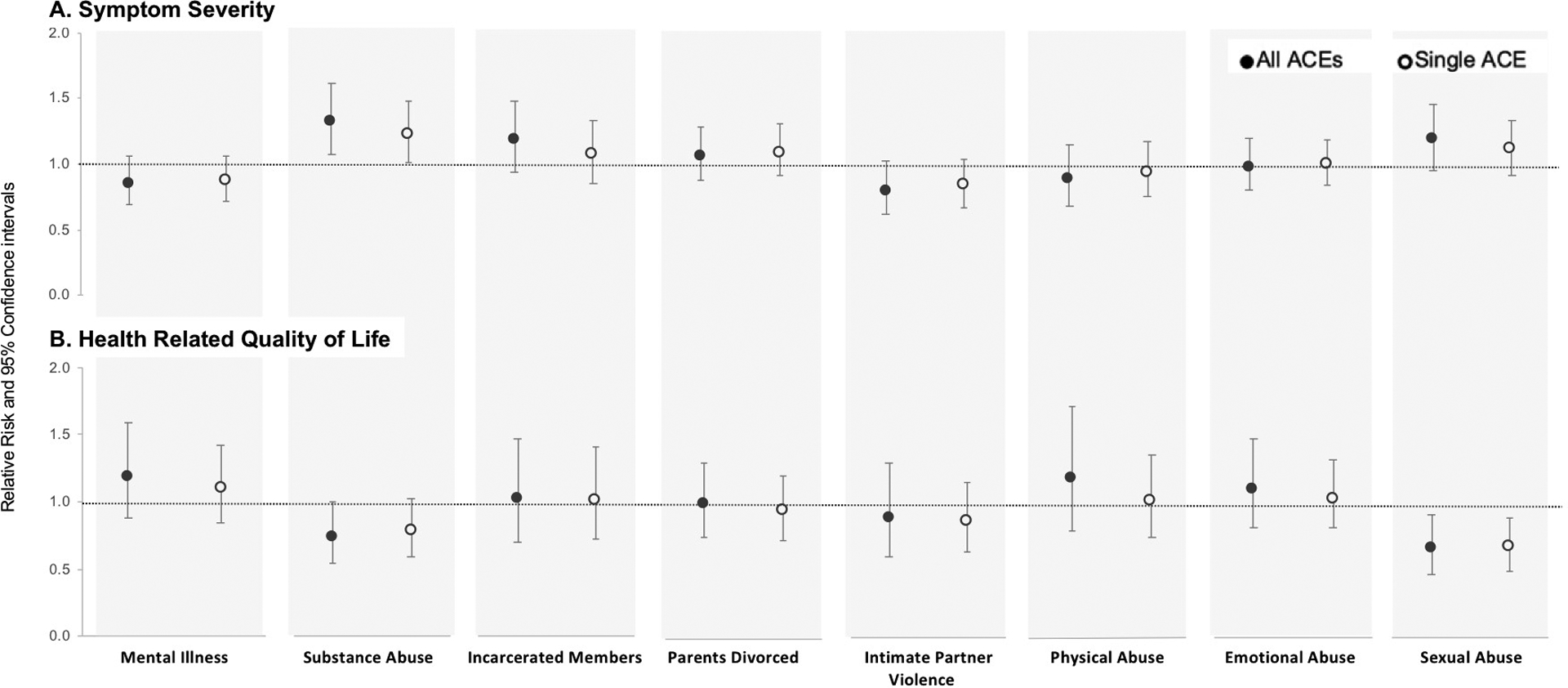

The majority of participants were Black (73%); about half had private insurance (55%) and a college degree (49%) (Supplemental Table S1). Cumulative ACE and symptom severity scores were higher among Black compared to non-Black women (p ≤ 0.03). Symptom severity also varied by education, with the most severe symptoms reported among those with the least education (p = 0.02) (Tables S2 and S3). In models that included all ACE categories, history of substance abuse in the household was associated with greater symptom severity (relative risk (RR) = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.61), and marginally associated with worse HRQL (RR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.00). History of sexual abuse was also associated with worse HRQL (RR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.92). Results were similar when we modeled each ACE category separately (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multivariable Relative Risks (RR) and 95% Confidence Intervals for Symptom Severity and Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) Composite Scores (Standardized) by ACE category. We presented RR estimates from one model adjusting for all eight ACES (black-filled circle) and from eight models adjusting for each ACE separately (open circle). A RR > 1.0 for symptom severity score indicated higher probability of worse symptoms, while a RR > 1.0 for the HRQL score indicated a higher probability of better quality of life. All models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and education. Statistical significance can be approximated if the 95% confidence intervals do not contain with the null RR value of 1.0 (gray line).

Conclusions

Our study adds to the growing evidence that early life exposures to chronic stress may influence gynecologic health, including symptom-related quality of life. These findings warrant replication due to study limitations including cross-sectional study design, potential recall bias on events that occurred in childhood, and the modest sample size. Nonetheless, our data point to the need to investigate how psychosocial stressors contribute to fibroid risk, including the disproportionate burden in Black women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge Dr. Gary Moawad, Dr. Maria (Vicky) Vargas, and Dr. Catherine Wu for assistance with participant recruitment. We acknowledge Roshni Rangaswamy, Samar Ahmad, Brianna VanNoy, Dan Dinh, Tahera Alnaseri, and Olivia Wilson who contributed to participant recruitment, data collection, and database management.

Sources of financial support:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Child Health and Development (R21HD096248), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001876, KL2TR001877), The George Washington University Milken School of Public Health, and The George Washington University Office of the Vice President for Research (Cross-disciplinary Research Fund). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: A.A.H. has provided consulting services to Abbvie, Allergan, Bayer, Myovant, MD Stem Cells, Novartis and OBS-EVA and reports no conflict of interest. In addition, A.A.H. holds a patent for Methods for novel diagnostics and therapeutics for uterine sarcoma (US Pat No. 9,790,562 B2). All other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rich-Edwards JW, Jun H-J, Hibert EN, Wright RJ. Self-reported abuse in childhood and risk of uterine leiomyoma: the role of emotional support in biological resiliency. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2011;22(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vines AI, Ta M, Esserman DA. The association between self-reported major life events and the presence of uterine fibroids. Women’s health issues. 2010;20(4):294–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zota AR, VanNoy BN. Integrating Intersectionality Into the Exposome Paradigm: A Novel Approach to Racial Inequities in Uterine Fibroids. Am J Public Health. 2020;(0):e1–e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1038–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou NG, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.