Abstract

There is a critical need for high-quality and accessible treatments to improve mental health. Yet, there are indications that the research being conducted by contemporary marriage and family therapy (MFT) scholars focuses less on advancing and disseminating clinical interventions than in previous decades. In this article, we describe challenges to increasing rigorous clinical research in MFT. We use systems mapping and the intervention-level framework to identify strategic goals designed to drive innovation in clinical research in the field. It is our hope this article encourages dialog and action among MFT stakeholder groups to support clinical science that will improve the health and functioning of families.

Marriage and family therapy (MFT) has played an important role in advancing treatments that improve the mental health and functioning of individuals and families. In the 1950s and 1960s, when psychoanalytic interventions were common, novel theoretical approaches such as strategic, intergenerational, experiential, structural, and others were developed (Shields, Wynne, McDaniel, & Gawinski, 1994). Additional models such as cognitive behavioral (Baucom & Epstein, 1990; Jacobson, 1981), emotionally focused (Greenberg & Johnson, 1988; Johnson, 1996), solution focused (de Shazer, 1991), and narrative (White & Epston, 1990) therapy surfaced in the 1980s and 1990s. Since 2000, major contributions have included new iterations of early approaches (e.g., Dattilio, 2009; Henggeler, Clingepeel, Brondino, & Pickerel, 2002; Szapocznik & Hervis, 2005), and the dissemination and adaptation of existing approaches (e.g., Johnson & Wittenborn, 2012; Monson et al., 2012). While this body of work is impressive, there are indications that current research conducted by contemporary MFT scholars focuses less on advancing and disseminating clinical interventions than in previous decades. For example, the majority of rigorous clinical research in couple and family therapy during the past few decades has not involved investigators within the discipline of MFT (Sprenkle, 2002, 2012). In doctoral programs, it is common for students to complete dissertation research on nonclinical questions answered with existing datasets, leaving the next generation of scholars without the critical skillset needed to advance family therapy.

Over the past several decades, the landscape of health care has changed dramatically to prioritize evidence-based practices. Breakthrough science has led to substantial declines in rates of mortality from conditions such as AIDS, heart disease, and certain cancers (e.g., leukemia; Bray, Ren, Masuyer, & Ferlay, 2012; Insel, 2013), and suicide has been prioritized as the next condition in dire need of improved treatment (National Institute of Mental Health, 2018). There is no doubt that clinical research, including the development and dissemination of treatments, must be prioritized to meet the demand for mental health services. Unfortunately, it is not evident that MFT scholars will play an active role at the cutting edge of the clinical research enterprise. If the discipline of MFT is going to contribute to resolving the crisis in mental health care, more investigators must commit to leading programs of clinical research, and MFT organizations, such as the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT), must provide the structural support necessary for investigators to be successful. Otherwise, the future relevance of the discipline is in question.

In this article, we describe the need for a collective effort in MFT to develop and disseminate effective interventions to improve the mental health and functioning of families. The primary goal of this article is to describe challenges and propose strategies for producing more impactful clinical research in the field of MFT. We discuss challenges and solutions from a systemic perspective and recognize the shared responsibility required to make meaningful change. We hope this article will ignite conversation and spawn collaborative initiatives to strengthen family-based clinical research that will ultimately increase the development and dissemination of interventions that improve the lives of individuals and families.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM AND IDENTIFYING SOLUTIONS

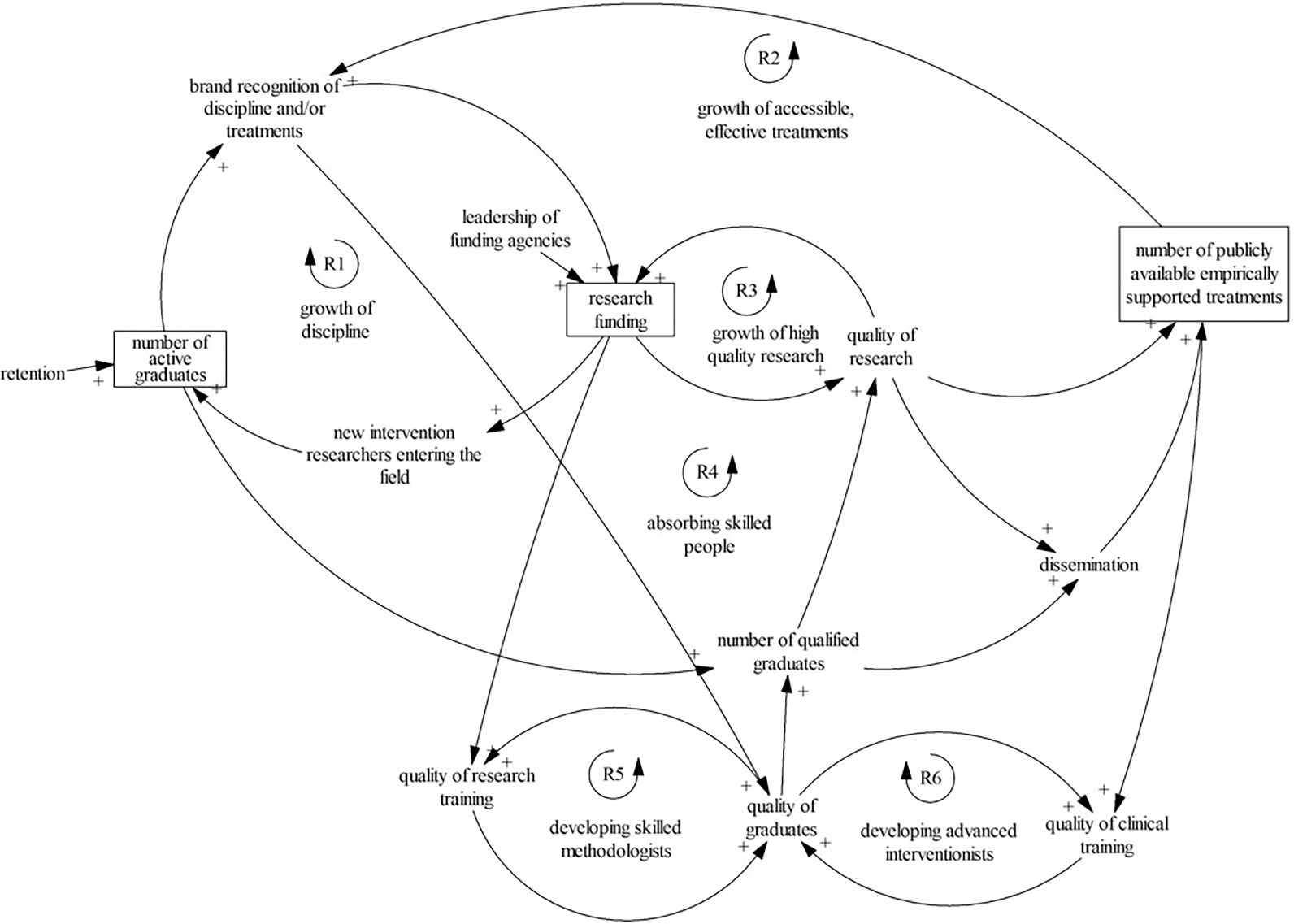

To better understand how to accelerate innovation in MFT clinical research in order to create more potent and widely available interventions, we turn to an approach called system dynamics. System dynamics is a method for examining complex and persistent problems (Sterman, 2006). One useful tool for understanding problems through this paradigm is causal loop diagramming. Such a diagram maps out the variables and related feedback loops that give rise to specific behaviors in a system. Causal loop diagrams can be informed by a variety of sources, including the empirical literature or interviews that reveal participants’ mental models of a system. Once a causal map is developed, useful intervention strategies can be discovered. According to Meadows (2009), “We change paradigms by building a model of the system, which takes us outside the system and forces us to see it whole” (p. 164). In that spirit, through discussions with one another, and informed by the empirical literature, we created a causal loop diagram that maps out the variables and feedback loops that identify paths to improvements in the quality and accessibility of family interventions. The causal loop diagram (Figure 1) is provided to illustrate our conceptualization of how clinical research can be increased in MFT and to offer a rationale for our suggested path forward. In other words, we provide the diagram to “show our work” and illustrate the worldview that informed our recommended solutions. To interpret the model, it is important to note a few basic ideas. While the model may appear static, it portrays dynamics that occur over time; it also represents causal processes, not correlations. The mapping of variables indicates the mechanisms by which one variable affects another, though each variable ultimately has an influence on all other variables in the systemic model. Of course, all models are simplifications of real-world processes, and this model is no different. Other exogenous processes exist outside the boundary of this model.

Figure 1.

Causal loop diagram of the dynamics of clinical research in MFT.

The model provided a method for identifying leverage points, or key strategies that can stimulate innovations in clinical research in MFT. To gain insights from the model, we used the Intervention-Level Framework (ILF; Johnston, Matteson, & Finegood, 2014), which provides a structure for estimating the potential impact of a given strategy within a system. The ILF focuses on several levels of intervention, two of which pertain directly to the current discussion. One level involves shifts in the fundamental organization of the structure of a system; change at this level is highly effective but is often the most difficult to implement. The second involves changes to the structural elements, such as the actions of individual investigators. While change at this level is easier to execute, it tends to make less of an overall impact. The ILF framework is a valuable tool because it requires one to consider the rules that govern the system, in addition to the individual players in a system, since change at both levels is needed to create meaningful and sustainable (i.e., second-order) change (Meadows, 2009). We used the causal loop diagram and ILF to systematically consider barriers and strategies to increase rigorous clinical research in the field of MFT. This approach kept us focused on the processes relevant to the change we seek and prevented us from straying into a more general critique of the field. The strategies developed through this process are described next, beginning with the most potent.

CHANGE AT THE LEVEL OF SYSTEM STRUCTURE

The structure of a system or paradigm is one of the most difficult, yet powerful, points of intervention (Johnston et al., 2014); these deeply held beliefs serve to maintain the structure of systems. To identify and understand the fundamental values of a system, it is useful to consider its historical context. The field of MFT was conceived by interdisciplinary clinical scholars in reaction to the prevailing views on the family’s role, or lack thereof, in mental health care at the time (Shields et al., 1994). Resources for developing and maintaining the new discipline were directed toward gaining credibility, and indicators of the success of these initiatives included the existence of rigorous degree programs and the right to licensure in every state. Maintaining an unwavering focus on the expansion of the practice of MFT has undoubtedly benefited the discipline, yet it could be argued that doing so has impeded progress in the science of MFT. We argue that the resources being invested in the science of MFT are inadequate to support clinical innovations in family therapy. Resources must become better balanced within two key areas: the national organization and doctoral education. We refer to AAMFT specifically, though we recognize that other MFT organizations could be valuable contributors to the MFT research agenda.

Transforming the Goals of the AAMFT

Professional organizations have a variety of goals. A primary goal of the AAMFT has been to establish and promote the profession of marriage and family therapy. If the field is to flourish, however, future initiatives must support the expansion of the science of MFT, particularly clinical research. These goals are not at cross-purposes. Instead, better MFT clinical research will benefit the profession. For example, while developing and documenting effective MFT treatments can help to strengthen the quality of care, this empirical evidence also strengthens advocacy efforts and further contributes to the business case for third-party payers. In this way, investing in MFT clinical research promotes both the science and profession of marriage and family therapy. In the following section, we propose five areas in which AAMFT could make a positive impact on MFT clinical research, which includes supporting: (a) scholarly communities, (b) seed funding, (c) dissemination initiatives, (d) advocating for federal funding, and (e) research with ethnic and racial minorities.

Scholarly communities.

The general empirical literature overwhelmingly shows that belonging to a community of scientists is associated with greater scientific impact. In a study of 19.9 million scientific articles over five decades, research produced by teams received significantly more citations—the preferred proxy for scientific impact—than solo authored publications (Wuchty, Jones, & Uzzi, 2007). Increased collaboration also leads to more opportunities to secure funding for research. One study found that collaborative networks have a stronger influence on scholars’ chances for securing research funding than the publications they produce or the citation rates of their publications (Edabi & Schiffauerova, 2015). Collaborations are also known to promote scientific breakthroughs. In an analysis of more than half a million patent inventions, findings showed that individuals working alone were more likely to have poor outcomes and less likely to have breakthrough inventions when compared with collaborative teams (Singh & Fleming, 2010). Still other research found a significant relationship between collaboration and scientific productivity (Lee & Bozeman, 2005).

One way to support the scientific collaborations investigators need to be successful is through organizational infrastructure that establishes connections among scholars. A review of other professional organizations shows that they often play a key role in connecting scholars and building communities of scientists through task forces or other similar groups. Task forces have successfully been used to define the field, review the state of research and identify gaps, strategically plan future research, and develop clinical practice guidelines (Ritvo et al., 1999; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2017). Other methods of support include special interest groups, networking opportunities, and extensive opportunities to present and discuss research at national conferences (e.g., research symposiums, roundtables). While AAMFT provides some support for connecting researchers, current resources are limited. The AAMFT Research and Education Foundation has organized research conferences in the past for active researchers to connect, but the events have not occurred consistently enough to make an impact.

One change that recently passed through an AAMFT membership vote—the introduction of topical interest networks—could provide a new method for engaging and connecting scholars. AAMFT’s topical interest networks have the potential to resemble what other organizations often term special interest groups. A special interest group (SIG) is a valuable mechanism for connecting scholars interested in a specific problem. SIGs promote networks that give investigators a competitive advantage in grant funding and scholarship, reduce the burden of locating collaborators for new projects, and provide an opportunity for the exchange of new ideas. For example, the first author belongs to several SIGs focused on depression and/or suicide that are composed of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) officials. These groups aim to connect researchers, identify knowledge gaps and funding priorities, and develop new collaborative projects. The fourth author is involved in a similar group focused on global mental health.

We envision an AAMFT topical interest network focused on clinical research as a valuable tool; such a group would need three key elements to be successful. First, the group would require a sustainable organizational structure. This would include a governance and funding mechanism to ensure the group is able to sustain itself. Too often, these efforts have not succeeded due to lack of a clear organizational structure to secure its future. Second, such a group would need to be attractive to senior funded intervention scholars interested in MFT clinical research in order to engage them into the group to provide leadership. Third, a clinical research interest group would need to provide significant opportunities for members to interact with each other in meaningful and intellectually stimulating ways. Such stimulation would be a strong force for creativity and could generate significant ideas and opportunities for future clinical studies.

Seed funding for research.

Seed funding plays an instrumental role in establishing a leading program of research. In order to be competitive for federal awards, it is essential that investigators have pilot data to support their proposed research. It is also advantageous for academics to seek funding that will provide additional time for research (e.g., course reduction), in order to dedicate time to writing a competitive grant proposal. Other ways in which seed money could promote clinical research is through support for grant editing and expert reviews of grant applications from external investigators. Seed money does not need to be a large amount, but enough to gather pilot data or to assist faculty in securing a course release to write a competitive proposal. The second author, for example, received over two million dollars in federal grant funding based on pilot data collected using two small pots of seed money ($5,000 and $25,000), and the first author was awarded a grant from the NIH as a result of a small grant that reduced her teaching load one semester to allow time to prepare a successful application. The American Psychological Association and the Society for Psychotherapy Research are examples of organizations that offer such funding opportunities to members. AAMFT could play a significant role in the future of clinical research by allocating resources for this purpose.

Disseminate research findings.

Marriage and family therapy interventions have a large body of literature supporting their effectiveness (see Sprenkle, 2012). However, evidence-based MFT practices have not been widely adopted and sustained by individual clinicians or supported by policy makers (Dattilio, Piercy, & Davis, 2014); thus, there is a pressing need for AAMFT to offer ongoing dissemination and implementation support for effective MFT interventions. It is alarming that medical interventions (i.e., drugs) continue to be widely used as the first treatment of choice for many mental health conditions despite evidence and clinical guidelines for the safety and effectiveness of psychotherapy (American Psychiatric Association, 2010; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009). Consider children with ADHD, for example. Parent-administered behavioral therapy is the evidence-based first line of treatment recommended for young children and should be strongly considered instead of, or in some cases in addition to, ADHD medications for children through the elementary school years (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011). Yet, medications such as Adderall or Ritalin are often relied on exclusively. This is just one example where AAMFT could help to address this situation by actively disseminating the findings of MFT clinical research studies.

Marriage and family therapies are in a unique position to contribute to and benefit from dissemination initiatives (e.g., Withers, Reynolds, Reed, & Holtrop, 2017). An ideal location to begin the dissemination of findings from clinical research is at professional meetings. It is important to note that discussion resulting from presentations feeds back into the research through improvements made as a result of colleagues’ recommendations. A highly effective method to share cutting-edge clinical findings is through brief presentations in research symposia selected by scholars with expertise in the field. Unfortunately, the current 2- to 3-hr format of AAMFT conference workshops is not conducive to this process, and the selection of workshops by AAMFT staff has resulted in a lack of focus on cutting-edge science. The current “research discussion” format also falls short of this purpose, because scheduling these presentations at inconvenient times or in congested spaces leads to poor attendance and a noisy atmosphere that is not conducive to scientific discussion. Two strategies to improve this would be to create an AAMFT scientific review committee, consisting of MFT scholars, to help select deserving scientific abstracts, and to incorporate brief research symposia workshops (e.g., 1 hr) in which several researchers would present their individual findings on a related topic.

Critical dissemination initiatives must also take place outside of professional meetings. To begin, AAMFT could help convene a task force of scholars to develop empirically based practice guidelines; guidelines should be posted online for consumers, clinicians, and policymakers. Second, AAMFT has been very successful in advocating for reimbursement for services provided by licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs), and these advocacy efforts must be expanded to fully benefit the integration of science into practice. More on advocacy is discussed in the next section. Third, AAMFT could spearhead an advertising campaign that informs consumers about the MFT interventions available for treating common problems. Drug companies have reaped huge profits from well-crafted marketing strategies, yet behavioral interventions are rarely advertised. For example, what if an advertisement for couple therapy targeted Facebook users after they changed their relationship status to “it’s complicated”? Implementing these solutions would involve some challenges, as funding and resources would need to be re-allocated. Yet concerted, strategic efforts to better disseminate MFT-relevant interventions could ultimately have a meaningful, positive impact on the field.

Advocating for federal funding.

American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy actively advocates to fund the practice of MFT (e.g., to support reimbursement for LMFTs). We argue that it is equally as critical for AAMFT to advocate to fund the science of MFT by interfacing with government organizations (e.g., Administration for Children and Families, National Institutes of Health), insurance companies (e.g., Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation grants program), and other funding sources. The American Psychological Association (APA) has a long history of advocating for federal funding in support of research in behavioral and social sciences (Kaplan, Bennet Johnson, & Clem Kobor, 2017). We are unaware of similar campaigns in AAMFT’s history. Of course, APA is better poised to advocate given its larger membership and financial resources, but there are still meaningful actions that AAMFT could take. One area of research in which funding is particularly scarce is clinical research involving couples. The lack of federal funding available for research in this area is surprising when you consider the substantial impact of one’s partner on key health behaviors linked to morbidity and mortality, such as smoking, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and social support (Kaplan et al., 2017; Lewis & Butterfield, 2007; Oxford Health Alliance, 2017). If federal funding allocations for clinical research in MFT are to increase, it will require well-coordinated campaigns in partnership with other organizations with similar interests. Identifying and developing relationships with well-positioned advocates could support this process, building on AAMFT’s success in securing a legislator and advocate for mental health care as a plenary speaker for the 2014 annual conference. In addition to persuading Congress and directors of federal agencies, strategies that raise awareness of the effects of relationships on health among the public may also be useful. Op-Eds in the New York Times or other outlets could play a major role in engaging the public to put pressure on federal agencies and foundations to support the development and implementation of novel interventions.

Support for research addressing mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minorities.

A final way we suggest in which AAMFT can help strengthen MFT clinical science is through support for research addressing mental health disparities among racial/ethnic minorities. AAMFT has made great strides in recent years promoting culturally competent practice. These advances must dovetail with a commitment to MFT clinical research focused on racial/ethnic minorities to ensure an appropriate body of research to support effective practice with diverse populations.

The efforts undertaken by AAMFT through the Minority Fellowship Program (MFP) funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) are essential for the future of the MFT field because the ultimate goal of this initiative is to prepare the next generation of MFT practitioners and scholars committed to offering clinical services and conducting research with ethnic minorities and diverse populations. Once these professionals graduate, however, there is concern they will not transition into a context that offers the resources and mentoring required to maintain an active focus on minority populations. Currently, if an early career MFT scholar wants to commit to a program of applied research with minority populations, the best resources for formal training and ongoing support can only be found outside our primary organization. There is a need for AAMFT to expand programs and organizational resources to nurture and support early career scholars focused on minority populations through active programs of mentoring, networking, and funding support.

The efforts of peer organizations can provide ideas for feasible and effective initiatives. For example, Family Process Institute and the American Psychological Association offer annual funding competitions to support students and early career professionals with a commitment to serve underrepresented populations. These funds also serve as seed money that allows researchers to establish reputations, gather pilot data, and obtain publications, all of which are essential in the further acquisition of larger funding. The Society for Prevention Research has permanent standing committees focused on mentoring early career scholars and professionals focused on ethnic minority populations. In addition to having an active presence in the annual meeting of the organization through a series of social and scholarly events (e.g., symposia, poster sessions), these committees have infrastructure focused on providing continuous networking and mentoring opportunities to their members throughout the year. The AAMFT Research and Education Foundation may provide a means for supporting such initiatives for MFT clinical researchers, but its trustees will need to carefully consider strategic dispersion of funds that results in impactful results for racial/ethnic minorities.

Rigorous Clinical Research Training in MFT Doctoral Degree Programs

In addition to transforming the goals of our national organization, advancing MFT clinical research at the level of system structure will also require changes to MFT doctoral education. In the past, various factors played a role in de-emphasizing education in clinical research in doctoral degree programs. For instance, postmodern epistemology made important contributions to MFT, but the theoretical tension between postmodern thinking and positivistic science created an era in which empirical findings were less valued by some. This influenced the design of degree programs, dissertations, and instruction provided in courses.

Current COAMFTE accreditation standards provide a structure in which individual programs have vast flexibility in adapting curricula to incorporate the advanced clinical and methods training needed by the next generation to develop robust expertise in clinical research. We propose several strategies for preparing MFT clinical scholars. First, doctoral programs need to attract and inspire talented students who are motivated to conduct clinical research. While an excellent group of students are found in COAMFTE accredited training programs, it is our experience that high-quality applicants oriented toward research are often lost to other fields of study or select nonclinical research topics. It will be important to inspire interest in MFT among students early in their academic trajectories—an approach that has been successful for STEM disciplines (Yilmaz, Ren, Custer, & Coleman, 2010), and then to translate this inspiration into conducting clinical studies. MFT training programs or organizations may consider hosting a “relationship science week” for undergraduate students or at local high schools where they facilitate activities and offer educational materials to students about the science of healthy relationships. AAMFT could engage MFT scholars to help create a relationship week curricula that could be disseminated by MFT programs. MFT faculty could also work to increase representation of their discipline at job fairs and graduate recruiting activities by liaising with advising offices within their universities or local high schools. The first author attends job fairs sponsored by local schools for student recruitment purposes.

Second, doctoral programs must offer more opportunities for students to engage in rigorous clinical research. This means MFT investigators need to carry out clinical research through which students can gain hands-on learning experiences. Training programs that do not provide these opportunities will be less likely to produce effective clinical researchers. This is not an easy task, of course, since federal funding to support rigorous family therapy research has become increasingly competitive. However, family clinical scholars in other fields are successfully competing for awards. Receiving structural support from AAMFT could result in more opportunities for MFT faculty that could then provide additional hands-on learning opportunities for students and could help faculty to gather the pilot data needed to complete competitive federal grant applications.

Third, students need opportunities to gain expertise in evidence-based interventions. While more attention is being paid to evidence-based practice in graduate education, this is typically limited to learning about evidence-based interventions and falls short of providing training in the intervention necessary to lead a program of clinical research (Dattilio et al., 2014). Decreasing seminar and practicum time spent on foundational MFT approaches that lack empirical evidence to focus on the most current evidence-based interventions will be essential to the future success of the field. Within practice settings, this process is called de-implementation. De-implementation is a process of replacing interventions without empirical support or with findings that indicate an intervention is ineffective or harmful with modern evidence-based interventions, and it is gaining increasing support across clinical disciplines (Prasad & Ioannidis, 2014). To support this shift in MFT, it may be useful to engage in a train-the-trainer approach by providing opportunities for graduate faculty and supervisors to receive training in an evidence-based model. The train-the-trainer approach has been effective in other efforts to train psychotherapy educators, but would require faculty buy-in and financial support from institutions (Nakamura et al., 2014). In addition, doctoral educators could explore developing hybrid courses that combine students and faculty from multiple programs and allow them to receive training in an evidence-based intervention from off-site experts (Withers et al., 2017).

Fourth, students need to receive advanced methods training that is relevant to clinical research. To meet this goal, at our university, we require MFT students to enroll in an advanced intervention research methods course in which students gain methods instruction pertinent to clinical research, and then apply those skills in class by developing, implementing, and evaluating a brief intervention. Students then disseminate the findings in a publishable manuscript. This course is part of a series of advanced methods and statistics courses.

Finally, after providing the requisite education, MFT doctoral programs must encourage students to pursue clinical research for the dissertation requirement. Similar to accounts from others (e.g., Stith, 2014), it is our experience that a sizable proportion of dissertations do not examine clinical interventions, but instead tend to align with family studies research or focus on examinations of ourselves—such as studies on MFT training processes (e.g., Sprenkle, 2010). Dissertation research provides an intensive learning experience and a bridge to early scholarship as an independent investigator. Increasing students’ engagement in clinical research is a critical method for increasing the likelihood that graduates will continue to engage in and contribute to MFT clinical research.

CHANGE AT THE LEVEL OF INDIVIDUAL INVESTIGATORS

Up to this point, our focus has been on strategies for enhancing clinical research in MFT that focus on change at the level of system structure. This is because change at one level is generally not feasible without concurrent change at another level, and it is immensely challenging for an individual investigator to become a productive clinical research scholar unless the shift is supported within broader contexts. We now turn to ideas for increasing novel clinical research at the level of individual investigators. Our discussion will focus on the following strategies for individual investigators: (a) engage in and sustain rigorous programs of clinical research, (b) study problems of global and national priority, (c) seek interdisciplinary collaborations, and (d) develop advanced methods expertise.

Engage in Rigorous and Sustained Programs of Intervention Research

The most obvious method for advancing clinical research in MFT is for more independent investigators to orient their programs of research toward clinical interventions. There are several promising areas of research that need attention. To begin, it remains important for future research to experiment with novel intervention approaches. For example, a common psychotherapy treatment paradigm involves a 50-min weekly meeting in a clinician’s office, but this type of structure has more to do with current insurance reimbursement and business models than empirical evidence. There are many research questions related to the structure, timing, and dosing of interventions that beg answers (Kazdin & Rabbitt, 2013). Technology also offers opportunities for advancing conventional MFT clinical practice. An exemplar of one emerging treatment for substance use uses smartphone technology to reduce rates of drug use and risk of relapse (Gustafson et al., 2014). Through a creative use of a smartphone application, clinicians and patients work together to implement strategies for reducing risk factors, increasing supports, and targeting environmental triggers that may lead to relapse. When the smartphone senses that a patient is physically close to an area in which he or she used or bought drugs, the phone implements a series of steps to persuade the patient to leave (e.g., an image of the patient’s daughter may appear or a mental health specialist may call). While the use of technology to intervene is not new, the fastpaced development of affordable technologies makes it a prime area for future innovation in MFT clinical research.

Of course, developing and manualizing a new intervention requires extensive time and effort to become familiar with the relevant basic science, understand the current body of existing interventions for a problem, design and refine treatment protocols through ongoing trials, and address important dimensions related to efficacy, effectiveness, dissemination, and implementation (Czajkowski et al., 2015). Needless to say, clinical research is a challenging endeavor. To be successful, researchers need considerable institutional support, a sustained stream of funding, and an array of collaborators—including access to strong research mentors and co-investigators within their discipline as well as willing interdisciplinary collaborators. One success story in clinical research on family therapy comes from the body of work on brief strategic family therapy (e.g., Horigian, Anderson, & Szapocznik, 2016). Decades of research, from pilot to implementation, have resulted in an effective family-based treatment for youth with behavior problems that is widely available in the community.

In addition, dissemination and implementation science provides a promising avenue for MFT clinical research (see Withers et al., 2017). Engaging in this area of research would allow MFTs to contribute toward finding solutions to better integrate evidence-based practices into real-world clinical settings. This research-practice gap remains a problem across many disciplines. In biomedical research, for example, basic science rarely translates into clinical practice. In a review of leading journals (e.g., Science, Nature, Journal of Experimental Medicine), the authors found that of articles clearly indicating a promising clinical therapeutic application, only one in four articles resulted in a published trial of the intervention and only one in ten is used in routine clinical practice (Contopoulos-Ioannidis, Ntzani, & Ioannidis, 2003). Important opportunities, therefore, exist for MFTs to develop a program of research in this area. MFT has a long history of investing in community-based research, and more recently, the funding priorities of the NIH and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) established by Congress in 2010 has brought increased attention to this focus. In particular, agencies have responded to the gaps between public health, research, and clinical practice by making a significant investment in dissemination and implementation science. NIH-sponsored conferences and training programs, as well as several current NIH funding announcements focus on addressing this gap.

Study Problems of National and Global Priority

To strengthen MFT clinical research, it is important to remain attentive to addressing problems of national and global priority. Health disparities research represents one critical area of focus (Merikangas et al., 2011). Yet while our MFT training curricula strongly emphasize issues of diversity, we currently play an insular role with regard to the generation of cutting-edge scholarship and research related to health and mental health disparities. A recent review of leading MFT journals concluded that only 28% of articles addressed at least one aspect of diversity as a primary issue (Seedall, Holtrop, & Parra-Cardona, 2014). Findings also indicated that “the vast majority of scholarly work being published in the field of MFT is still focused on majority groups, rather than those most at risk for experiencing stigma, social inequality, and marginalization” (Seedall et al., 2014, pp. 145–146). Thus, MFT tends to lag behind other fields in our research contributions to these areas. Moreover, MFT investigators maintain only a marginal presence in terms of membership and active participation with national and international research organizations leading the way in the field of health and mental health disparities research (e.g., Global Mental Health Summit, Society for Prevention Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities). Through increased engagement with organizations that offer training programs on disparities issues and a sustained commitment to building capacity in this area, there is great opportunity for MFTs to make critical contributions to the health disparities field through clinical intervention research.

A second priority area is global health problems. Systemic thinkers have important skills for reducing the burden of some of the most complex and challenging problems across the globe (Sprenkle, 2012). It is helpful for researchers to closely follow epidemiological findings and the prioritization of major public health problems among key agencies (e.g., NIH). For example, the World Health Organization website provides an up-to-date list of major global health problems (World Health Organization, 2017). Of the global problems ranked highly among those most burdensome today, such as conflict, suicide, depression, inequality, relational disharmony, trauma, and heart disease (World Health Organization, 2017), MFT researchers have the potential to make valuable contributions.

Consider hepatitis and HIV as two examples of global public health problems flagged by the World Health Organization. Infection from hepatitis results in approximately 1.45 million deaths each year, and 37 million people are infected with HIV (World Health Organization, 2017). Both hepatitis and HIV can be spread by contact with blood or bodily fluids, unsafe injections or transfusions, mother to child transmission, or sexual contact. In addition, hepatitis can be spread through contaminated water and food. Now, consider how MFTs could play an instrumental role in preventing these routes of transmission by supporting protective family processes that facilitate safe health practices including safe sexual health, allow for obtaining and adhering to medications, and protect children through effective parenting (e.g., Pequegnat & Bray, 2012).

A quick review of NIH Reporter (NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, 2017) results using the search terms “family-based” and “HIV” indicates that funding to evaluate family-based interventions for HIV has mostly been awarded to investigators in other disciplines. Such projects include: behavioral family therapy for substance abuse and HIV risk; HIV prevention interventions that promote couple communication, intimacy, and trust; and a family group intervention for adolescents living with HIV. These NIH funded studies use couple and family approaches to intervene in one of the largest health crises in history, yet few MFT researchers are involved in these advances (e.g., Serovich & Mosack, 2003). The field of MFT will continue to miss opportunities to contribute if we remain inattentive to global health issues.

Collaborate Across Disciplines

Marriage and family therapy originated as a multidisciplinary field that was informed by thinkers from diverse disciplines (Shields et al., 1994). However, like many other fields, MFT has been challenged by siloed thinking which can stifle innovation and lessen the impact of findings. Understanding diverse literatures and working with investigators and community partners from divergent fields can lead to mutual enrichment and novel ideas for strengthening the development and evaluation of interventions. Increased collaboration also expands opportunities to secure funding for research. One study found that collaborative networks have a stronger influence on a scholar’s chances for securing research funding than the publications they produce or the citation rates of their publications (Edabi & Schiffauerova, 2015). While team science is not without challenges (Hall et al., 2012), the level of complexity that is feasible for research endeavors with collaborative teams is beyond that of single investigators or siloed teams (Wuchty et al., 2007).

Engaging in multidisciplinary research is a strategy that could increase the impact of MFT investigators’ programs of research. One example of a multidisciplinary partnership comes from the first author’s work modeling the dynamics of adult depression. This line of research is focused on developing a method for personalizing treatment, a current need in clinical research. The project included a multidisciplinary team of academics with expertise in couple and family therapy, psychology, management, engineering, public health, and economics. The team developed a system dynamics simulation model that was used to determine optimal treatments for a given patient profile (Hosseinichimeh, Rahmandad, Jalali, & Wittenborn, 2016; Wittenborn, Rahmandad, Rick, & Hosseinichimeh, 2016). For an example of an effective cross-disciplinary partnership involving the second author, see Dalack et al. (2010).

Develop Advanced Research Methods and Statistics Expertise

Developing advanced methodological skills is instrumental to engaging in rigorous MFT clinical research. Historically, however, a desire to engage in patient-centered care and an inclination to favor postmodern epistemologies have led many to erroneously conclude that scientific research cannot be used to appropriately guide clinical practice. It is also true that in the past, methodologies did not exist for effectively examining complex, system processes, but this is no longer the case. While perspectives on science have slowly changed across decades, the damage caused by de-valuing science continues to be felt today. There is a critical need to develop a new generation of methodologists in MFT.

To build capacity among MFT investigators in advanced methodological skills, we recommend the following actions as initial steps. First, a train-the-trainer model could help train educators in advanced methods and statistics. Such an approach could be carried out at a system-wide or individual level. AAMFT, or other MFT national organizations, could incorporate a methods track at national conferences or offer weeklong intensive sessions. Over the course of multiple days, attendees could either get refreshed on common topics or learn about new techniques in research methods. An initial strategy might be to support faculty to attend MFP statistics and methods workshops at AAMFT, or to offer a preconference institute on advanced statistics for MFT research. In addition, individual investigators could attend some of the short course offerings across the country to refresh and build on skills. Workshops through Mplus, Todd Little’s Stats Camp, Statistical Horizons, and the inter-university consortium for political and social research (ICPSR) are good places to begin. Doctoral programs could consider joining forces and hiring an expert to offer online training and consultation to MFT graduate educators. To supplement these efforts, investigators would also need access to colleagues or statistical consultants to provide consultation on an as-needed basis. It is common to encounter obstacles when engaging in advanced analyses and having supportive resources in place to troubleshoot problems when they arise is vital to success.

CONCLUSION

While we acknowledge challenges facing the field of MFT, we recognize we are not alone in these struggles and that many other disciplines are facing similar issues. Indeed, we are quite hopeful for the future. We recognize that our suggested path forward requires significant commitment and resources shared across stakeholders, and that some of our ideas suggest unexplored territories for creating change within the discipline. It is our hope this article begins a new dialog for advancing the next era of clinical research in MFT. But, more than dialog, we hope it ignites action—action among MFT stakeholder groups to support and engage in science that will improve care for the millions of people suffering from mental illness.

Contributor Information

Andrea K. Wittenborn, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, MI.

Adrian J. Blow, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Kendal Holtrop, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

José R. Parra-Cardona, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; Steve Hicks School of Social Work, University of Texas, Austin, TX.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2011). ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 128, 1007–1022. 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2010). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Retrieved on November 16, 2017, from http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1667485.

- Baucom DH, & Epstein N (1990). Cognitive-behavioral marital therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, & Ferlay J (2012). Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Epidemiology, 132, 1133–1145. 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ntzani E, & Ioannidis JP (2003). Translation of highly promising basic science research into clinical applications. The American Journal of Medicine, 114, 477–484. 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, et al. (2015). From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychology, 34, 971–982. 10.1037/hea0000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalack GW, Blow AJ, Valenstein M, Gorman L, Spinner J, Marcus S et al. (2014). Working together to meet the needs of Army National Guard Soldiers: An academic-military partnership. Psychiatric Services, 61, 1069–1071. 10.1176/appi.ps.61.11.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattilio FM (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with couples and families: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dattilio FM, Piercy FP, & Davis SD (2014). The divide between “evidenced-based” approaches and practitioners of traditional theories of family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40, 5–16. 10.1111/jmft.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edabi A, & Schiffauerova A (2015). How to receive more funding for your research? Get connected to the right people!. PLoS ONE, 10, e0133061. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS, & Johnson SM (1988). Emotionally focused therapy for couples. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, et al. (2014). A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 566–572. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KL, Stokols D, Stipelman BA, Vogel AL, Feng A, Masimore B, et al. (2012). Assessing the value of team science: A study comparing center- and investigator-initiated grants. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 157–163. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingepeel WG, Brondino MJ, & Pickerel SG (2002). Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy on drug and abuse in serious juvenile offenders: A progress report from two outcome studies. Family Dynamics of Addiction Quarterly, 1, 40–51. 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horigian VE, Anderson AR, & Szapocznik J (2016). Taking brief strategic family therapy from bench to trench: Evidence generation across translational phases. Family Process, 55, 529–542. 10.1111/famp.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinichimeh N, Rahmandad H, Jalali MS, & Wittenborn AK (2016). Estimating the parameters of system dynamics models using indirect inference. American Journal of System Dynamics Review, 32, 156–180. 10.1002/sdr.1558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T (2013, January). Thomas Insel: Toward a new understanding of mental illness [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/thomas_insel_toward_a_new_understanding_of_mental_illness

- Jacobson NS (1981). Behavioral marital therapy. In Gurman AS & Kniskern DP (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy (pp. 556–591). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM (1996). Creating connection: The practice of emotionally focused marital therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, & Wittenborn AK (2012). New research findings on emotionally focused therapy: Introduction to special section. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38, 18–22. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LM, Matteson CL, & Finegood DT (2014). Systems science and obesity policy: A novel framework for analyzing and rethinking population-level planning. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 1270–1278. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Bennet Johnson S, & Clem Kobor P (2017). NIH behavioral and social sciences research support: 1980–2016. American Psychologist, 72, 808–821. 10.1037/amp0000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Rabbitt SM (2013). Novel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illness. Clinical Psychological Science, 1, 170–191. 10.1177/2167702612463566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, & Bozeman B (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35, 673–702. 10.1177/0306312705052359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, & Butterfield RM (2007). Social control in marital relationships: Effect of one’s partner on health behaviors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 298–319. 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows DH (2009). Thinking in systems: A primer. Sterling, VA: Earthscan. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCSA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson C, Fredman S, MacDonald A, Pukay-Martin N, Resick P, & Schnurr P (2012). Effects of cognitive-behavioral couple therapy for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 308, 700–709. 10.1001/jama.2012.9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Selbo-Bruns A, Okamura K, Chang J, Slavin L, & Shimabukuro S (2014). Developing a systematic evaluation approach for training programs within a train-the-trainer model for youth cognitive behavior therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 53, 10–19. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2009). Depression in adults: Recognition and management. Retrieved November 16, 2017, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90. [PubMed]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2018). The push for suicide prevention. Retrieved April 23, 2018, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/messages/2016/the-push-for-suicide-prevention.shtml

- NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools. (2017, June 3). Retrieved June 6, 2017, from https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm

- Oxford Health Alliance. (2017). About Us. Retrieved November 16, 2017 from http://www.oxha.org/

- Pequegnat W, & Bray JH (2012). HIV/STD prevention interventions for couples and families: A review and introduction to the Special Issue. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1, 79. 10.1037/a0028682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad V, & Ioannidis JP (2014). Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implementation Science, 9, 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo R, Al-mateen C, Ascherman L, Beardslee W, Hartmann L, Lewis O, et al. (1999). Report of the psychotherapy task force of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 8, 93–102. https://doi.org/10079457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedall RB, Holtrop K, & Parra-Cardona JR (2014). Diversity, social justice, and intersectionality trends in C/CFT: A content analysis of three family therapy journals, 2004–2011. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40, 139–151. 10.1111/jmft.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serovich JM, & Mosack KE (2003). Reasons for HIV disclosure or nondisclosure to casual sexual partners. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 70–80. https://doi.org/12627744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Shazer S (1991). Putting difference to work. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Shields CG, Wynne LC, McDaniel SH, & Gawinski BA (1994). The marginalization of family therapy: A historical and continuing problem. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 20, 117–138. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1994.tb01021.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, & Fleming L (2010). Lone inventors as sources of breakthroughs: Myth or reality? Management Science, 56, 41–56. 10.1287/mnsc.1090.1072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle DH. (Ed.) (2002). Effectiveness research in marriage and family therapy. Alexandria, VA: The American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle DH (2010). The present and future of MFT doctoral education in research-focused universities. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36, 270–281. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle DH (2012). Intervention research in couple and family therapy: A methodological and substantive review and an introduction to the special issue. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38, 3–29. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterman JD (2006). Learning from evidence in a complex world. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 505–514. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM (2014). What does this mean for graduate education in marriage and family therapy? Commentary on “The divide between ‘evidenced–based’ approaches and practitioners of traditional theories of family therapy”. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40, 17–19. 10.1111/jmft.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Hervis O (2005). Brief strategic family therapy (NIDA Manual Series). Retrieved February 11, 2005, from http://www.nida.nih.gov/TXManuals/bsft/BSFTIndex.html

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2017). Retrieved June 6, 2017, from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/

- White M, & Epston D (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Withers MC, Reynolds JE, Reed K, & Holtrop K (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in marriage and family therapy: An introduction and call to the field. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 13, 183–197. 10.1111/jmft.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenborn AK, Rahmandad H, Rick J, & Hosseinichimeh N (2016). Depression as a systemic syndrome: Mapping the feedback loops of major depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine, 46, 551–562. 10.1017/S0033291715002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. Retrieved November 16, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254610/1/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wuchty S, Jones BF, & Uzzi B (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316, 1036–1038. 10.1126/science.1136099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M, Ren J, Custer S, & Coleman J (2010). Hands-on summer camp to attract K–12 students to engineering fields. IEEE Transactions on Education, 53, 144–151. 10.1109/TE.2009.2026366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]