Abstract

Patients with cancer demonstrate an increased vulnerability for infection and severe disease by SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 include comorbidities, uncontrolled disease, and current line of treatment. Although COVID-19 vaccines have afforded some level of protection against infection and severe disease among patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, decreased immunogenicity and real-world effectiveness have been observed among this population compared with healthy individuals. Characterizing and understanding the immune response to increasing doses or differing schedules of COVID-19 vaccines among patients with cancer is important to inform clinical and public health practices. In this article, we review SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with solid tumors, hematologic malignancies, and those receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplant or chimeric-antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

Keywords: chimeric-antigen receptor T-cell therapy, hematologic malignancies, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, solid tumors

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, the literature has demonstrated an increased vulnerability for infection and severe disease among patients with cancer [1, 2]. In patients with solid tumors, immune dysregulation may arise due to vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression inhibiting immune cell development and function [3]. From a large prospective cohort of patients with solid tumors, researchers found that age and sex rather than receipt of active chemotherapy were risk factors for severe COVID-19, similar to the general population [4]. In patients with hematologic malignancies, susceptibility for infection may relate to immunosuppression from their underlying disease and/or receipt of anticancer therapy [2, 5–7]. Other risk factors for COVID-19 infection or severe disease include comorbidities, status of disease (controlled vs uncontrolled), and current line of treatment ([neo]adjuvant, first line, or second line and beyond) [8–10]. In addition, recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) or chimeric-antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) are at high risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 disease due to dysregulation of immune cell populations via broad myelo- and lymphotoxicity from preparatory conditioning regimens and slow recovery of immunity and the impact of prior treatment regimens [6, 11, 12]. A higher immunodeficiency score index group, older age, and poor performance status have also been associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19 in patients following HSCT [13, 14].

The emergence of COVID-19 vaccines has afforded some level of protection against infection and severe disease among patients with cancer; however, decreased immunogenicity and real-world effectiveness was observed among patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies [6, 11, 15–17]. Thus, understanding and characterizing the immune response to increasing doses or differing schedules of COVID-19 vaccines among patients with cancer are important to better inform clinical and public health practices in this population moving forward. In this study, we review SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with solid tumors, hematologic malignancies, and those receiving HSCT or CAR-T.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BURDEN OF COVID-19 AMONG PATIENTS WITH CANCER AND THE IMPACT OF VACCINATION

Analyses from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences National COVID Cohort Collaborative identified 398 579 adult patients with cancer in the United States, 63 413 (15.9%) of whom had a COVID-19 diagnosis between January 1, 2020 and March 25, 2021 (vaccination status was not indicated but due to timing of the analysis, unvaccinated status can likely be assumed) [12]. COVID-19 was most prevalent in patients with skin (14.9%), breast (14.2%), prostate (12.3%), hematologic (12.3%), and gastrointestinal cancers (8.8.%) [12]. Between December 2019 and June 2020, the estimated global prevalence of COVID-19 among patients with cancer was 7% but ranged from 4% to 22% depending on the country and/or region [5].

Among patients with cancer, a current diagnosis of COVID-19 is associated with increased risk of mortality. A cohort study characterized COVID-19 outcomes in patients with active or previous malignancy from the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) database between March 17 and April 16, 2020, and identified 928 patients, 26% of whom had severe COVID-19 illness and 13% died [7]. In addition, before the availability of COVID-19 vaccines, a study in the United Kingdom reported a mortality rate of 30.6% in patients with cancer and COVID-19, citing COVID-19 as the cause of death in 92.5% of these cases [18]. Patients with hematologic malignancies, and those receiving autologous or allogeneic HSCT or CAR-T, are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 and COVID-19–related mortality relative to other cancer populations [6, 12, 14, 19]. For instance, in patients with hematologic malignancies and those receiving CAR-T, COVID-19–related mortality rates of up to 34% and 41% have been reported (before the availability of COVID-19 vaccines or when vaccination status was not reported, respectively), which is up to 40 times greater than the COVID-19 mortality rate for the general population, depending on the country and type of underlying hematologic malignancy [17, 20]. Overall, findings suggest that the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 is dependent on the type of cancer, with higher risk for patients with hematologic malignancies [20–24].

Breakthrough infections and severe outcomes are more likely to occur in COVID-19–vaccinated patients with cancer than in vaccinated individuals without cancer, with the highest risk in patients with hematologic malignancies and those receiving systemic antineoplastic agents (specifically during the delta and omicron wave) [23, 24]. Widespread uptake of COVID-19 vaccines has substantially reduced the mortality rate among patients with cancer [25, 26]. Overall, these results highlight the poor outcomes among patients with cancer infected with COVID-19, especially in patients with hematologic malignancies and those receiving CAR-T, and emphasize the importance of vaccination in this population.

SARS-CoV-2 VACCINE IMMUNOGENICITY STUDIES IN PATIENTS WITH CANCER

Humoral Immune Responses

Many studies have focused on SARS-CoV-2 antibody response to the receptor binding domain (RBD) or spike protein and have demonstrated that patients with cancer have lower COVID-19 vaccine seropositivity rates than the general adult population [27–29]. Although patients with solid tumors typically have higher seropositivity rates compared with patients with hematologic malignancies, or those undergoing HSCT or CAR-T, antibody levels are still lower than in individuals without cancer [30–33]. Furthermore, receipt of active cancer therapy can impact immune responses after COVID-19 vaccination (Table 1 [30, 34, 35]). In particular, B cell-depleting therapies (including cluster of differentiation [CD]-20 monoclonal antibodies) and the use of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors and Janus kinase inhibitors have been associated with reduced seropositivity rates [24, 30, 34–37]. In contrast, endocrine therapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors, proteasome inhibitors, and immunomodulatory drugs have not demonstrated an impact on seroresponse [30, 34, 35].

Table 1.

| Cancer Treatment | Impact of Treatment on RBD-Antibody Responsea | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine therapy | Low | … |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Low | TKIs used for the treatment of solid tumors do not appear to impair humoral responses to COVID-19 vaccination |

| Proteasome inhibitors | Low | … |

| Immunomodulatory drugs | Low | … |

| Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors | Low | … |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors | Low | … |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | Low-moderate | Most patients were able to mount an adequate antibody response after 2 doses of vaccines while receiving ICIs |

| Conventional chemotherapy | Low-moderate | Recent chemotherapy (28 days to within 6 months of vaccination) has been identified as a risk factor for lower serologic response |

| Corticosteroids | Low-moderate | Impact determined by corticosteroid dose; high-dose steroid use is a risk factor for reduced serologic response |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplant | Moderate | Serologic response is dependent on timing of vaccination relative to transplant and use of any concurrent immunosuppressive treatments |

| Janus kinase inhibitor | Moderate | Studies suggest lower antibody levels with ruxolitinib compared to non-JAKi-treated patients with MPN |

| Cluster of differentiation-20 | High | Timing of CD-20 treatment may impact seropositivity rates; lower antibody responses were observed in patients who received treatment <6 months before vaccination compared to those who were treated over 6–12 months |

| Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor | High | Low serologic response rates but higher cellular response rates |

| Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy | High | Rates of serologic response can remain low in patients >12 months after CAR-T therapy; studies suggest possible differences in response rates based on antibody targets (BCMA, CD-19) |

Abbreviations: BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; CD, cluster of differentiation; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; JAKi, Janus kinase inhibitor; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; RBD, receptor binding domain; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Low impact: ≥ 80% seropositive response rate; moderate impact: 50% to 80% seropositive response rate; high impact: ≤ 50% seropositive response rate.

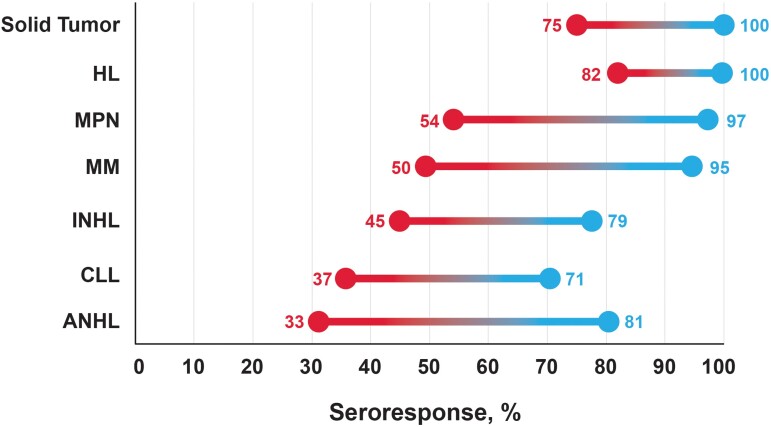

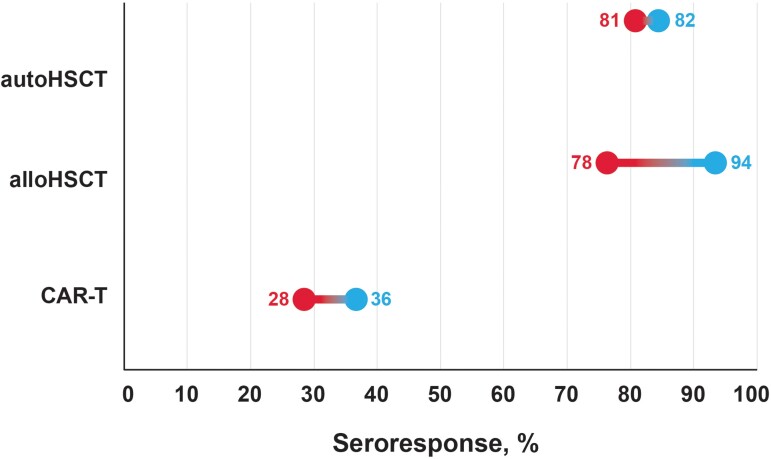

Specifically, in studies of patients with solid tumors, seropositivity ranged from 75% to 100% after 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccines that received emergency use authorization from the World Health Organization, including those who received mRNA vaccination (mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2) (Figure 1 [38–40] and Tables 2 [28, 30, 38, 39, 41–47] and 3 [30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–49, 51]) [38, 39]. Additional doses of the vaccine increased the seroresponse rates with a range of 83%–100% after dose 3% and 100% after dose 4 [38, 46, 47]. In patients with hematologic malignancies, a wide range of seropositivity rates have been reported because of populations with different underlying malignancies (Figure 1 [38–40]). Overall, rates ranged from 21% to 87% after dose 2, 14% to 96% after dose 3, and from 87% to 100% after dose 4 [30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–51]. Rates of seropositivity after 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccine were lowest in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (range, 33%–81%) and in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (range, 37%–71%), whereas patients with Hodgkin lymphoma had highest response rates (range, 82%–100%). Rates of seropositivity in patients receiving HSCT therapy ranged from 78% to 94% after dose 2 and from 58% to 90% after dose 3 (Figure 2 [16, 52–54]) [16, 38, 52–55]. CAR-T recipients had the lowest rates of seropositivity, ranging from 28% to 36% after dose 2 and from 25% to 40% after dose 3 (Figure 2 [16, 52–54]) [16, 53, 55, 56].

Figure 1.

Summary of the range of pooled antibody response rates after 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccines across hematologic malignancies [38–40]. Seroresponse rates will vary depending on other factors including disease treatment status, type of therapy, and timing of vaccination. Red represents the lowest seroresponse rate observed and blue represents the highest seroresponse rate observed. ANHL, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; INHL, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Table 2.

Vaccine Response in Patients With Solid Tumors

| Study | Number of Doses | Study Characteristics | Vaccine(s) | Cancer Type | Seropositivity Ratea | nAb Response | T-Cell Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becerril-Gaitan et al [28] | 1 | Meta-analysis including 35 studies (6 studies in patients with solid tumors) | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or CoronaVac | Solid tumors: type not specified | 45% | … | 78% (among 84 patients) |

| 2 | 95% | … | 60% (among 634 patients) | ||||

| Lee et al [41] | 1 | SLR (11 studies, including 827 patients with solid tumors) | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or CoronaVac | Solid tumors: type not specified | 55% | … | … |

| 2 | 90% | … | … | ||||

| Corti et al [30] | 2 | SLR (36 studies included) | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or CoronaVac | Solid tumors: type not specified | Overall, 85% Rangeb, 48%–100% |

… | … |

| Martins-Branco et al [42] | 2 | SLR and meta-analysis including 89 records reporting data from 30 183 patients | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | Solid tumors: type not specified | Overall, 94% Rangeb, 64%–99% |

… | 68% |

| Oosting et al [39] | 1 | Prospective study in 503 patients with solid tumors (VOICE Study) | mRNA-1273 | Bone/soft tissue Breast CNS Digestive tract Endocrine glands Female/male genital organs Head and neck Respiratory tract Skin Urinary tract |

Immunotherapy, 37% Chemotherapy, 32% Chemoimmunotherapy, 33% |

… | … |

| 2 | Immunotherapy, 93% Chemotherapy, 84% Chemoimmunotherapy, 89% |

… | Immunotherapy, 67% Chemotherapy, 66% Chemoimmunotherapy, 53% |

||||

| Debie et al [38] | 2 | Prospective study in 141 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies (B-VOICE Study) | BNT162b2 | Solid tumors: type not specified | Targeted/hormonal therapy, 97% Chemotherapy, 75% Chemoimmunotherapy, 100% Immunotherapy, 88% |

… | … |

| 3 | Targeted/hormonal therapy, 100% Chemotherapy, 83% Chemoimmunotherapy, 100% Immunotherapy, 88% |

… | … | ||||

| Su et al [43] | 2 | Prospective study in 51 patients with solid tumors | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | Prostate NSCLC Colorectal Urothelial Mesothelioma Renal cell Sarcoma SCLC |

53% | 59% | … |

| 3 | 96% | 97% | … | ||||

| Fendler et al [44] | 3 | Prospective study in 353 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies (CAPTURE study) | BNT162b2 | Solid tumors: type not specified | … | nAb to delta, 67% | 73% |

| Luangdilok et al [45] | 2 | Study of 131 patients with solid tumors who received homologous or heterologous dose 3 | CoronaVac/ChAdOx1 | Breast Colorectal Head and neck Hepatobiliary-pancreatic Esophagus/gastric Genitourinary Lung |

CoronaVac/ChAdOx1, 16% ChAdOx1/ChAdOx1, 10% |

… | … |

| 3 | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | CoronaVac/ChAdOx1, 91% ChAdOx1/ChAdOx1, 90% |

CoronaVac/ChAdOx1, 86% (omicron BA.2) ChAdOx1/ChAdOx1, 78% (omicron BA.2) |

… | |||

| Debie et al [46] | 3 (D 28) | Continuation of above B-VOICE study plus Tri-VOICE with 157 patients with cancer | BNT162b2 | Solid tumors: type not specified | Targeted/hormonal therapy, 98% Chemotherapy, 100% Immunotherapy, 100% |

… | … |

| 4 | Targeted/hormonal therapy, 100% Chemotherapy, 100% Immunotherapy, 100% |

… | … | ||||

| Ehmsen et al [47] | 3 | Study in 395 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | Breast Urological and gynecological Skin Thoracic Gastrointestinal Other |

99% | … | … |

| 4 | 100% | … | … |

Figure 2.

Summary of the range of pooled antibody response rates after 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccines in patients who received hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) [16, 52–54]. Seroresponse rates will vary depending on other factors including disease treatment status, type of therapy, and timing of vaccination. Red represents the lowest seroresponse rate observed and blue represents the highest seroresponse rate observed. alloHSCT, allogeneic HSCT; autoHSCT, autologous HSCT.

Additional vaccine doses can increase humoral immune response in patients with cancer who do not fully respond after 2 doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine and provide protection against new variants of concern (VOC). A wide range of seropositivity rates were reported, but most studies demonstrated that ≥40% of patients with cancer who did not respond to 2 vaccine doses, achieved seropositivity after an additional dose (Tables 2 [28, 30, 38, 39, 41–47] and 3 [30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–49, 51]). Furthermore, neutralization antibody (nAb) titers increased after additional doses of COVID-19 vaccines (Tables 2 [28, 30, 38, 39, 41–47] and 3 [30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–49, 51]). In patients with solid tumors, the percentage of patients with neutralizing responses against the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant increased from 47.8% to 88.9% after dose 3 [35]. Where measured, nAb response rates in patients with hematologic malignancies ranged from 52% to 60% after 2 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine and ranged from 62% to 100%, depending on the variant after dose 3 [40, 48, 49, 51]. Overall, additional doses (3 or 4) improved seroresponse and nAb rates, even in patients with cancer who did not respond after 2 doses.

Cellular Immune Responses

Humoral responses after vaccination are typically reported as a measure of protection against infection; however, cellular responses can also indicate the measure of protection against infection and are associated with severity of disease. Lower T-cell responses have been found to correlate with more severe outcomes from COVID-19 [32, 57]. T-cell responses have been observed after COVID-19 vaccination despite a poor humoral immune response, and, in some patients with hematologic malignancies, T-cell response rates after vaccination may be higher than humoral response rates [48, 58–60].

Studies suggest that cellular responses were variable among patients with cancer, with T-cell responses observed in 53% to 78% of patients with solid tumors, 33% to 86% of patients with hematologic malignancies, and 42% to 72% of HSCT/CAR-T recipients (Tables 2 [28, 30, 38, 39, 41–47], 3 [30, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–49, 51], and 4 [16, 38, 52–56]). In response to COVID-19 infection, Bange et al [61] demonstrated that a greater frequency of SARS-CoV-2-specific polyfunctional (interferon-γ, interleukin 2 producing) CD8+ T cells correlated with survival postinfection, highlighting their potential importance following vaccination. Furthermore, T-cell responses could be crucial for protection against new viral variants [35, 62–64].

Table 3.

Vaccine Response in Patients With Hematologic Malignancies

| Study | Number of Doses | Study Characteristics | Vaccine(s) | Cancer Type | Seropositivity Ratea | nAb Response | T-Cell Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gagelmann et al [40] | 1 | SLR and meta-analysis including 49 studies comprising 11 086 patients | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, or Ad26.COV2.S | Amyloidosis Lymphoma Myeloid Lymphoid Myelofibrosis CLL MM MPN NHL HL WM |

Overall, 37% | … | … |

| 2 | Overall, 64% Rangeb, 29%–87% |

52% | … | ||||

| Teh et al [48] | 1 | SLR and meta-analysis including 44 studies comprising 7064 patients | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, Ad26.COV2.S, or ChAdOx1 | Myeloma CLL Lymphoma Acute leukemia and MDS MPN and CML |

Rangeb, 37%–51% | 18%–63% | 33%–86% |

| 2 | Rangeb, 62%–66% | 57%–60% | 40%–75% | ||||

| Corti et al [30] | 2 | SLR (36 studies included) | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or CoronaVac | Multiple myeloma MDS MPN Lymphoma CLL |

54% | … | … |

| Martins-Branco et al [42] | 2 | SLR and meta-analysis including 89 records reporting data from 30 183 patients | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | NS | Overall, 60% Rangeb, 42%–78% |

… | 59% |

| Debie et al [38] | 2 | Prospective study in 141 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies (B-VOICE Study) | BNT162b2 | NS | Rituximab, 21% Rituximab, 14% |

… | … |

| 3 | … | … | |||||

| Uaprasert et al [34] | 2 | SLR and meta-analysis including 12 studies from 1479 patients | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | MM CLL NHL MPN HL MDS |

Overall, 68% Treated, 59% Nontreated, 80% |

53% | 67% |

| 3 | Overall, 41% Rangeb, 3%–83% |

… | |||||

| Greenberger et al [36] | 3 | N = 49 patients with B-cell malignancies | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | CLL NHL WM MM CLL+ marginal zone lymphoma Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease |

65% | … | … |

| Haggenburg et al [49] | 3 | Prospective cohort study in 584 patients with hematologic malignancies | mRNA-1273 | Lymphoma MM CLL CML AML and high-risk MDS MPN |

79% | WT, 100% Delta, 98% Omicron BA.1, 92% |

… |

| Sherman et al [50] | 3 | Prospective cohort study in 94 patients with lymphoid malignancies | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | CLL DLBCL MCL FL MZL HL Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma CNS lymphoma PLL T-LGL |

68% | … | … |

| Debie et al [46] | 3 (D 28) | Continuation of above B-VOICE study plus Tri-VOICE with 157 patients with cancer | BNT162b2 | NS | 96% | … | … |

| 4 | 100% | … | … | ||||

| Ehmsen et al [47] | 3 | Study in 395 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | CLL or SLL MM DLBCL FL MCL MZL Other |

80% | … | … |

| 4 | 87% | … | … | ||||

| Fendler et al [51] | 3 | Continuation of CAPTURE study with 80 patients with blood cancer | BNT162b2 | Lymphoma Myeloma CLL Acute leukemia MDS |

… | WT, 87% Delta, 72% Omicron BA.1, 62% |

T-cell responses against: WT CD4+, 59% WT CD8+, 56% Omicron CD4+, 31% Omicron CD8+, 34% |

| 4 | … | WT, 98% Delta, 78% Omicron BA.1, 79% |

T-cell responses against: WT CD4+, 81% WT CD8+, 56% Omicron CD4+, 59% Omicron CD8+, 44% |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CD, cluster of differentiation; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CNS, central nervous system; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; nAb, neutralizing antibody; NS, not specified; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PLL, prolymphocytic leukemia; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SFC, spot-forming cells; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; SLR, systematic literature review; T-LGL, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia; WM, Waldenström macroglobulinemia; WT, wild type.

Definitions for seropositivity varied across studies.

Range of seropositivity identified across studies.

Table 4.

Vaccine Response in Patients Who Received HSCT or CAR-T

| HSCT/CAR-T | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of Doses | Study Characteristics | Vaccine(s) | Cancer Type | Seropositivity Ratea | nAb Response | T-Cell Response |

| Einarsdottir et al [52] | 1 | 50 patients in Sweden with alloHSCT | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | AML ALL CLL Lymphoma MDS Myelofibrosis AA MM Thalassemia |

alloHSCT, 76% | … | 42% |

| 2 | alloHSCT, 94% | … | 72% | ||||

| Ge et al [16] | 1 | Meta-analysis including 27 studies comprising 2506 patients with alloHSCT, 286 patients with autoHSCT, and 107 patients with CAR-T | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, Ad26.COV2.S, or ChAdOx1 | Multiple | Overall, 62% Range, 17%–89% autoHSCT, 87% alloHSCT, 59% CAR-T, 20% |

… | … |

| 2 | Overall, 75% Range, 7%–97% autoHSCT, 82% alloHSCT, 79% CAR-T, 28% |

… | … | ||||

| 3 | Overall, 69% Range, 7%–97% autoHSCT, 63% alloHSCT, 82% CAR-T, 25% |

… | … | ||||

| Wu et al [53] | 1 | Meta-analysis including 44 studies comprising 3495 patients with alloHSCT, 1182 patients with autoHSCT, and 80 patients with either alloHSCT or autoHSCT, and 12 studies with 174 patients with CAR-T | mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, Ad26.COV2.S, or CoronaVac | NS | autoHSCT/alloHSCT, 41% | … | … |

| 2 | autoHSCT/alloHSCT, 81% CAR-T, 36% |

… | … | ||||

| 3 | autoHSCT/alloHSCT, 79% | … | … | ||||

| Shem-Tov et al [54] | 2 | 152 patients in Israel with alloHSCT | BNT162b2 | AML MDS MPN ALL NHL HL CLL AA |

alloHSCT, 78% | HSCT GMT, 116 Healthy individuals GMT, 428 |

… |

| Debie et al [38] | 2 | Prospective study in 141 patients with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies (B-VOICE Study) | BNT162b2 | NS | HSCT, 90% | … | … |

| 3 | HSCT, 90% | … | … | ||||

| Abid et al [55] | 3 | A total of 75 patients (alloHSCT, n = 30; autoHSCT, n = 26; CAR-T, n = 10) were included | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | NS | autoHSCT, 63% alloHSCT, 58% CAR-T, 40% |

… | … |

| Sesques [56] | 3 or 4 | 43 CAR-T patients in France | mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 | DLBCL FL Other NHL |

CAR-T, 18% | … | 42% |

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; alloHSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; autoHSCT, autogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; GMT, geometric mean titer; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; nAb, neutralizing antibody; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NS, not specified.

Definitions for seropositivity varied across studies.

Durability of the Immune Response

Humoral responses are generally less durable in patients with cancer than in healthy populations [65]. The reduced durability of COVID-19 vaccine-induced immunity may be attributed to a lack of memory cell formation in these populations, or possibly from ongoing B-cell depletion from certain therapies in B-cell hematologic malignancies [35, 65]. Binding and nAb waning are more often observed among patients with hematologic malignancies than those with solid tumors [37, 65]. A study in patients with cancer undergoing systemic treatment or HSCT observed that the anti-RBD response peaked 4 weeks after dose 2 of an mRNA vaccine and was sustained at 6 months after dose 2, although peak antibody levels in these patients were well below antibody concentrations observed in healthy participants [65]. The durability of immune responses after additional doses of COVID-19 vaccines is still under investigation and will be an important factor in timing and administration of boosters.

Approaches to Enhancing the Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Beyond Additional Doses

Increasing the number of vaccine doses administered to patients with cancer has demonstrated beneficial effects on both the humoral and cellular response; however, from a practical standpoint, it may not always be feasible to frequently administer doses in these patients, especially with ongoing active treatment. Additional strategies are needed to bolster the immune response in this population without solely relying on administering more doses. Alternative strategies that have been explored to enhance the immune response after COVID-19 vaccination include extending the interval between doses and using heterologous vaccination (administration of different vaccines, including those from different vaccine platforms). Note that a delayed interval dosing has been evaluated in a few studies of healthcare workers but not in cancer populations. Studies in healthcare workers found that extending the standard 3- to 6-week interval between the first and second doses of BNT162b2 to 6 to 14 weeks or 8 to 16 weeks significantly increased anti-RBD antibody titers, improved nAb responses to ancestral, alpha, beta, and delta strains, and enriched the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response [66, 67].

Use of a heterologous vaccine regimen can enhance humoral and cellular response in patients with cancer as well as healthy individuals. In particular, in patients with solid tumors who received a heterologous regimen of CoronaVac/ChAdOx1 vaccines for doses 1 and 2 followed by a third dose with an mRNA vaccine, seroresponse increased from 16% after dose 2 to 91% after dose 3 with significant increases in anti-RBD antibodies observed [45]. A study in patients with hematologic malignancies investigated the serologic response to a third dose of Ad26.COV2.S after 2 doses of BNT162b2 and observed a seroresponse in 31% of patients [68]. In immunocompetent individuals, a heterologous vaccine regimen increased nAb titers by a factor of 4 to 73 as well as increased spike-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, providing a robust and durable immune response [69]. These strategies offer several options to help enhance the immune response in patients with cancer and need to be further evaluated.

Careful consideration should be used when determining the number of doses, the interval between doses, and the type of vaccine administered regarding both the primary series (doses 1 and 2) as well as any subsequent additional doses (dose 3 and beyond). The development and availability of variant-updated booster vaccines can potentially expand the protection against SARS-CoV-2 VOC. The bivalent vaccines combining ancestral and an omicron variant strain have yet to be robustly evaluated in patients with cancer.

REAL-WORLD EFFECTIVENESS

Although patients with cancer generally develop a less robust immune response after vaccination against COVID-19 compared to individuals without cancer [35], the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 among patients with cancer is lower after completion of 2 doses of an mRNA vaccine, with or without additional doses, than in unvaccinated patients with cancer [23, 70]. Effectiveness of a third mRNA vaccine dose against breakthrough infections, symptomatic infections, COVID-19–related hospitalization, and mortality in patients with cancer was 59.1%, 62.8%, 80.5%, and 94.5%, respectively [71]. In a large, real-world study, the vaccine effectiveness (VE) of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 hospitalization in patients with cancer (before omicron variants became predominant) was estimated to be 75% [35]. Another study in the United Kingdom reported the VE of available COVID-19 vaccines against breakthrough infections in patients with cancer was similar to a control population shortly after dose 2 (65.5% vs 69.8%); however, VE at 3–6 months after dose 2 was lower in the cancer cohort than the control population (47.0% vs 61.4%) [72].

Consistent with observations in the general population, VE against VOCs have also decreased progressively in patients with cancer, although the reduction has been most prominent in patients with hematologic malignancies [35]. A study demonstrated 56% of patients with hematologic malignancies had neutralizing activity against the ancestral Wuhan strain but only 31% of patients had detectable antibody concentrations against the delta VOC after 2 vaccine doses [73]. Although mRNA COVID-19 vaccines offer some protection against breakthrough infections, the probability of these infections increases over time due to waning immunity. Breakthrough infections in patients with cancer often have a more severe course and a higher risk of mortality compared with a healthy population [35]. With the ever-evolving landscape of SARS-CoV-2 VOC and the impact of waning immunity, it remains vital to continue assessing the VE of COVID-19 vaccines, including the variant-updated bivalent vaccines, in patients with cancer.

SAFETY OF COVID-19 VACCINES IN PATIENTS WITH CANCER

Although patients with cancer were not included as the majority targeted population in the original registry trials of COVID-19 vaccines, the safety profile of these vaccines in immunocompromised populations has since been established [15]. At this time, there is no evidence to suggest that COVID-19 vaccines have a different safety profile in patients with cancer than in the general population, and patients receiving cancer therapies do not have an increased risk of immune-related adverse events (AEs) or graft-versus-host disease (hematologic malignancies) after administration of a COVID-19 vaccine [15, 35, 52]. Furthermore, no differences in vaccine-related AEs have been observed between hematologic or solid malignancies or between patients undergoing cancer treatment and those who were treatment naive [15]. The most common local and systemic side effects related to vaccination were pain at injection site, myalgia, and fatigue, which were mostly mild to moderate in severity. In patients receiving HSCT or CAR-T, common local reactions related to vaccination included pain and swelling and redness at the injection site; common systemic reactions included fever, chills, fatigue, myalgias, and arthralgias [16]. These events were generally mild and resolved within days. Overall, the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer is comparable to that of the general population and the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination greatly outweigh the risks for patients with cancer [35].

CONCLUSIONS

As COVID-19 continues to evolve, it is important to continually evaluate the immune response and real-world effectiveness of vaccination among immunocompromised individuals. Patients with cancer typically develop a less robust immune response after COVID-19 vaccination than individuals without cancer, resulting in higher risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 [35]. In general, lower immune responses are observed in patients with hematologic malignancies compared with patients with solid tumors [15]. However, cellular responses, which are associated with protection against severe disease, are higher than humoral response in some patients with hematologic malignancies and B-cell depletion, which highlights the ongoing importance of vaccination in these groups [52, 53].

In most severely immunocompromised patients, a 3-dose primary series of an mRNA vaccine is recommended followed by additional booster doses. Recommendations for bivalent vaccines vary by country and region. Administration of additional doses may induce stronger humoral and/or cellular responses in these vulnerable populations with preliminary evidence of translation to real-world effectiveness [71]. Although both humoral and cellular responses tend to increase with additional doses of vaccine, it is important to note that cellular responses can still occur in the absence of a humoral response and could offer protection against severe COVID-19 [59–61].

Adverse event rates related to vaccination are generally low in patients with cancer, demonstrating that these individuals can be safely vaccinated during active therapy [15]. Furthermore, patients with solid tumors can generally achieve humoral and cellular response rates that are similar to those responses in immunocompetent individuals [15, 35]. However, in some patient groups, low or nonexistent humoral response rates are observed, and additional preventative measures may be required [16, 38, 59, 74].

Future studies should focus on identifying correlates of protection for vaccinated individuals, especially among those with poor humoral responses. In addition, improved reporting of cellular responses in patients with cancer is needed to better understand the immune responses observed in this population. It would also be important to examine whether the immune response recovers during remission and to what extent. Finally, more data are needed on heterologous vaccination schedules and varied dosing intervals in immunocompromised populations. This review was limited in focus on the immunologic and clinical responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Additional studies on the immune response after variant-updated bivalent vaccines and vaccination in combination with COVID-19 therapeutics or other types of pre-exposure prophylaxis are needed in patients with cancer.

Contributor Information

Victoria G Hall, Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Benjamin W Teh, Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Notes

Acknowledgments . Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Lindsey Kirkland, PhD, of MEDiSTRAVA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines, funded by Moderna, Inc., and under the direction of the authors.

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “COVID-19 Vaccination in the Immunocompromised Population,” sponsored by Moderna, Inc.

References

- 1. Yang L, Chai P, Yu J, Fan X. Effects of cancer on patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 63,019 participants. Cancer Biol Med 2021; 18:298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fattore GL, Olivos NSA, Olalla JEC, Gomez L, Marucco AF, Mena MPR. Mortality in patients with cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection: results from the Argentinean Network of Hospital-Based Cancer Registries. Cancer Epidemiol 2022; 79:102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohm JE, Carbone DP. Immune dysfunction in cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002; 16:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee LY, Cazier JB, Angelis V, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1919–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kong X, Qi Y, Huang J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of cancer patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. Cancer Lett 2021; 508:30–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luque-Paz D, Sesques P, Wallet F, Bachy E, Ader F, Lyon HSG. B-cell malignancies and COVID-19: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29:332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1907–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Booth S, Curley HM, Varnai C, et al. Key findings from the UKCCMP cohort of 877 patients with haematological malignancy and COVID-19: disease control as an important factor relative to recent chemotherapy or anti-CD20 therapy. Br J Haematol 2022; 196:892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pagano L, Salmanton-Garcia J, Marchesi F, et al. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European Hematology Association Survey (EPICOVIDEHA). J Hematol Oncol 2021; 14:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Passamonti F, Cattaneo C, Arcaini L, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2020; 7:e737–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marchesi F, Salmanton-Garcia J, Emarah Z, et al. COVID-19 in adult acute myeloid leukemia patients: a long-term followup study from the European Hematology Association survey (EPICOVIDEHA). Haematologica 2022; 108:22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharafeldin N, Bates B, Song Q, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with cancer: report from the national COVID cohort collaborative (N3C). J Clin Oncol 2021; 39:2232–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ljungman P, de la Camara R, Mikulska M, et al. COVID-19 and stem cell transplantation; results from an EBMT and GETH multicenter prospective survey. Leukemia 2021; 35:2885–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sharma A, Bhatt NS, St Martin A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: an observational cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2021; 8:e185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Almasri M, Bshesh K, Khan W, et al. Cancer patients and the COVID-19 vaccines: considerations and challenges. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14:5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ge C, Du K, Luo M, et al. Serologic response and safety of COVID-19 vaccination in HSCT or CAR T-cell recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022; 11:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spanjaart AM, Ljungman P, de La Camara R, et al. Poor outcome of patients with COVID-19 after CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell malignancies: results of a multicenter study on behalf of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Infectious Diseases Working Party and the European Hematology Association (EHA) Lymphoma Group. Leukemia 2021; 35:3585–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee LYW, Cazier JB, Starkey T, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21:1309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shahzad M, Chaudhary SG, Zafar MU, et al. Impact of COVID-19 in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl Infect Dis 2021; 24:e13792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood 2020; 136:2881–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garcia-Suarez J, de la Cruz J, Cedillo A, et al. Impact of hematologic malignancy and type of cancer therapy on COVID-19 severity and mortality: lessons from a large population-based registry study. J Hematol Oncol 2020; 13:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malard F, Genthon A, Brissot E, et al. COVID-19 outcomes in patients with hematologic disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2020; 55:2180–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song Q, Bates B, Shao YR, et al. Risk and outcome of breakthrough COVID-19 infections in vaccinated patients with cancer: real-world evidence from the national COVID cohort collaborative. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40:1414–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mair MJ, Mitterer M, Gattinger P, et al. Enhanced SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in patients with hematologic and solid cancers due to omicron. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:444–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Mortality risk of COVID-19. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 26. Salmanton-Garcia J, Marchesi F, Glenthoj A, et al. Improved clinical outcome of COVID-19 in hematologic malignancy patients receiving a fourth dose of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: an EPICOVIDEHA report. Hemasphere 2022; 6:e789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang W, Zhang D, Li Z, Zhang K. Predictors of poor serologic response to COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2022; 172:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becerril-Gaitan A, Vaca-Cartagena BF, Ferrigno AS, et al. Immunogenicity and risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2022; 160:243–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kakkassery H, Carpenter E, Patten PEM, Irshad S. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with cancer. Trends Mol Med 2022; 28:1082–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corti C, Antonarelli G, Scotte F, et al. Seroconversion rate after vaccination against COVID-19 in patients with cancer-a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2022; 33:158–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Addeo A, Shah PK, Bordry N, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccines in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell 2021; 39:1091–8.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corradini P, Agrati C, Apolone G, et al. Humoral and T-cell immune response after three doses of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in fragile patients: the Italian VAX4FRAIL study. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:e426–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giuliano AR, Lancet JE, Pilon-Thomas S, et al. Evaluation of antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination in patients with cancer in Florida. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8:748–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uaprasert N, Pitakkitnukun P, Tangcheewinsirikul N, Chiasakul T, Rojnuckarin P. Immunogenicity and risks associated with impaired immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and booster in hematologic malignancy patients: an updated meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J 2022; 12:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fendler A, de Vries EGE, GeurtsvanKessel CH, et al. COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer: immunogenicity, efficacy and safety. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022; 19:385–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greenberger LM, Saltzman LA, Senefeld JW, Johnson PW, DeGennaro LJ, Nichols GL. Anti-spike antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination in patients with B cell-derived hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell 2021; 39:1297–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shapiro LC, Thakkar A, Campbell ST, et al. Efficacy of booster doses in augmenting waning immune responses to COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Debie Y, Vandamme T, Goossens ME, van Dam PA, Peeters M. Antibody titres before and after a third dose of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 2022; 163:177–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oosting SF, van der Veldt AAM, GeurtsvanKessel CH, et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy for solid tumours: a prospective, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2021; 22:1681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gagelmann N, Passamonti F, Wolschke C, et al. Antibody response after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in adults with hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 2022; 107:1840–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee A, Wong SY, Chai LYA, et al. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022; 376:e068632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martins-Branco D, Nader-Marta G, Tecic Vuger A, et al. Immune response to anti-SARS-CoV-2 prime-vaccination in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2022; doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04185-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Su E, Fischer S, Demmer-Steingruber R, et al. Humoral and cellular responses to mRNA-based COVID-19 booster vaccinations in patients with solid neoplasms under active treatment. ESMO Open 2022; 7:100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fendler A, Shepherd STC, Au L, et al. Immune responses following third COVID-19 vaccination are reduced in patients with hematological malignancies compared to patients with solid cancer. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:114–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luangdilok S, Wanchaijiraboon P, Pakvisal N, et al. Immunogenicity after a third COVID-19 mRNA booster in solid cancer patients who previously received the primary heterologous CoronaVac/ChAdOx1 vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2022; 10:1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Debie Y, van Dam PA, Goossens ME, Peeters M, Vandamme T. Boosting capacity of a fourth dose BNT162b2 in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2023; 179:121–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ehmsen S, Asmussen A, Jeppesen SS, et al. Increased antibody titers and reduced seronegativity following fourth mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:800–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Teh JSK, Coussement J, Neoh ZCF, et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with hematologic malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv 2022; 6:2014–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Haggenburg S, Hofsink Q, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. Antibody response in immunocompromised patients with hematologic cancers who received a 3-dose mRNA-1273 vaccination schedule for COVID-19. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8:1477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sherman AC, Desjardins M, Cheng CA, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 messenger RNA vaccines in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: immunogenicity and reactogenicity. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:e920–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fendler A, Shepherd STC, Au L, et al. Functional immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern after fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose or infection in patients with blood cancer. Cell Rep Med 2022; 3:100781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Einarsdottir S, Martner A, Waldenstrom J, et al. Deficiency of SARS-CoV-2T-cell responses after vaccination in long-term allo-HSCT survivors translates into abated humoral immunity. Blood Adv 2022; 6:2723–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu X, Wang L, Shen L, He L, Tang K. Immune response to vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and CAR T-cell therapy recipients. J Hematol Oncol 2022; 15:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shem-Tov N, Yerushalmi R, Danylesko I, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Br J Haematol 2022; 196:884–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Abid MB, Rubin M, Ledeboer N, et al. Efficacy of a third SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine dose among hematopoietic cell transplantation, CAR T cell, and BiTE recipients. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:340–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sesques P, Bachy E, Ferrant E, et al. Immune response to three doses of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cell immunotherapy recipients. Cancer Cell 2022; 40:236–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schrezenmeier E, Rincon-Arevalo H, Stefanski AL, et al. B and T cell responses after a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32:3027–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nguyen THO, Lim C, Lasica M, et al. Prospective comprehensive profiling of immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients on zanubrutinib therapy. EJHaem 2023; 4:216–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liebers N, Speer C, Benning L, et al. Humoral and cellular responses after COVID-19 vaccination in anti-CD20-treated lymphoma patients. Blood 2022; 139:142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Re D, Seitz-Polski B, Brglez V, et al. Humoral and cellular responses after a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Nat Commun 2022; 13:864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bange EM, Han NA, Wileyto P, et al. CD8(+) T cells contribute to survival in patients with COVID-19 and hematologic cancer. Nat Med 2021; 27:1280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cortes A, Casado JL, Longo F, et al. Limited T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine among patients with cancer receiving different cancer treatments. Eur J Cancer 2022; 166:229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Debie Y, Van Audenaerde JRM, Vandamme T, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 after third dose BNT162b2 following double-dose vaccination with BNT162b2 versus ChAdOx1 in patients with cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2023; 29:635–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tarke A, Sidney J, Methot N, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the total CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell reactivity in infected or vaccinated individuals. Cell Rep Med 2021; 2:100355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Khan QJ, Bivona CR, Martin GA, et al. Evaluation of the durability of the immune humoral response to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer undergoing treatment or who received a stem cell transplant. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8:1053–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hall VG, Ferreira VH, Wood H, et al. Delayed-interval BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination enhances humoral immunity and induces robust T cell responses. Nat Immunol 2022; 23:380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Payne RP, Longet S, Austin JA, et al. Immunogenicity of standard and extended dosing intervals of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Cell 2021; 184:5699–714.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Reimann P, Ulmer H, Mutschlechner B, et al. Efficacy and safety of heterologous booster vaccination with Ad26.COV2.S after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in haemato-oncological patients with no antibody response. Br J Haematol 2022; 196:577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Atmar RL, Lyke KE, Deming ME, et al. Homologous and heterologous COVID-19 booster vaccinations. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1046–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Choueiri TK, Labaki C, Bakouny Z, et al. Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections among patients with cancer following two and three doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: a retrospective observational study from the COVID-19 and cancer consortium. Lancet Reg Health Am 2023; 19:100445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee LYW, Ionescu MC, Starkey T, et al. COVID-19: third dose booster vaccine effectiveness against breakthrough coronavirus infection, hospitalisations and death in patients with cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2022; 175:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lee LYW, Starkey T, Ionescu MC, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 breakthrough infections in patients with cancer (UKCCEP): a population-based test-negative case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2022; 23:748–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fendler A, Shepherd STC, Au L, et al. Adaptive immunity and neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern following vaccination in patients with cancer: the CAPTURE study. Nat Cancer 2021; 2:1305–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fendler A, Au L, Shepherd STC, et al. Functional antibody and T cell immunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection, including by variants of concern, in patients with cancer: the CAPTURE study. Nat Cancer 2021; 2:1321–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]