Abstract

The BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mouse displays elevated repetitive motor behaviors. Treatment with the partial M1 muscarinic receptor agonist, CDD-0102A, attenuates stereotyped motor behaviors in BTBR mice. The present experiment investigated whether CDD-0102A modifies changes in striatal glutamate concentrations during stereotyped motor behavior in BTBR and B6 mice. Using glutamate biosensors, change in striatal glutamate efflux was measured during bouts of digging and grooming behavior with a 1 s time resolution. Mice displayed both decreases and increases in glutamate efflux during such behaviors. Magnitude of changes in glutamate efflux (decreases and increases) from dorsomedial and dorsolateral striatum were significantly greater in BTBR mice compared to those of B6 mice. In BTBR mice, CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) administered 30 min prior to testing significantly reduced the magnitude change in glutamate decreases and increases from the dorsolateral striatum and decreased grooming behavior. Conversely, CDD-0102A treatment in B6 mice potentiated glutamate decreases and increases in the dorsolateral striatum and elevated grooming behavior. The findings suggest that activation of M1 muscarinic receptors modifies glutamate transmission in the dorsolateral striatum and self-grooming behavior.

Keywords: Striatum, acetylcholine, glutamate, muscarinic, biosensor, autism

Introduction

Restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs) represent one of two diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders (ASD).1 RRBs involve a range of behaviors that can include compulsive-like stereotypies, circumscribed interests, and cognitive rigidity that involves a resistance to change. Current pharmacological treatments to reduce these features are only modestly effective.2,3 Efforts to develop improved individualized therapeutic approaches for RRBs are constrained by a lack of knowledge about their causes from biochemical to neural systems and in the integration of knowledge across these levels of analysis.

Rodent models afford an opportunity to unravel abnormalities at a neural circuit and neurochemical level that contribute to RRBs in ASD. Like RRBs observed in ASD individuals, BTBR mice exhibit elevated stereotyped motors behaviors.4−9 Further, BTBR mice also exhibit striatal abnormalities that are related to stereotyped motor behaviors comparable to abnormalities in the striatum related to RRBs in ASD.10−13 Less clear is what striatal subregions may contribute to stereotyped motor behaviors with some findings suggesting they may result from altered dorsolateral striatal (DLS) function,14 while other studies suggest that dorsomedial striatal (DMS) abnormalities may underlie stereotyped, repetitive behaviors.15 Further unknown are the neurochemical mechanisms in the specific striatal circuitry that lead to RRBs. There is increasing evidence that an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling may be a common pathophysiology underlying ASD.16,17 Related, several studies have used proton magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy to examine concentrations of the major excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, in the frontal cortex and striatum of individuals with ASD and rodent models of autism.18−21 In rodent models, frontal cortex glutamate concentrations have been examined in BTBR mice, valproic acid-treated mice, 15q11-13 duplication mice, Shank3 knockout mice, as well as neuroligin 3 knock in mice and neuroligin 3 knockout rats.21 A significant glutamate change in frontal cortex is only observed in the neuroligin 3 models. In relation to the striatum, there have been mixed results in ASD subjects with no change in glutamate concentration,18 an increase in glutmate,19 and a decrease in glutamate20 reported. In the BTBR mouse model of autism an increase in both striatal glutamate and GABA is observed.21 MR spectroscopy is a powerful technique for measuring neurotransmitter concentrations in brain areas, but still unclear is how glutamate signaling may dynamically change in specific brain circuitry. This is particularly critical to understand because glutamatergic transmission may be differentially modulated across striatal subregions.22

Muscarinic cholinergic receptor stimulation can modify both glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling in the brain.23 Thus, targeting muscarinic receptors may be an effective approach for modifying altered glutamate and/or GABAergic signaling that underlies an autism phenotype. A recent study in BTBR mice examined the effects of the partial M1 muscarinic agonist CDD-0102A on digging behavior in the nesting removal test.24 Acute and subchronic treatment as well as an intrastriatal infusion of CDD-0102A attenuated elevated digging behavior in BTBR mice. More specifically, systemic injections of CDD-0102A at a 1.2 mg/kg dose significantly attenuated elevated self-grooming behavior and digging behavior.24 In all cases, CDD-0102A at the 1.2 mg/kg dose reduced stereotyped motor behavior in BTBR mice without affecting overall locomotor activity, indicating that the drug effect at 1.2 mg/kg was selective to the stereotyped motor behavior. This contrasts with the effect of higher doses that tended to reduce locomotor activity in both B6 and BTBR mice. Furthermore, the CDD-0102A effect on self-grooming behavior was blocked by a selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist.24 One possibility is that stimulation of M1 muscarinic receptors may modify glutamate transmission in striatal circuits, in part, to reduce stereotyped motor behaviors.

The present experiment determined whether glutamate efflux differentially changes in the dorsolateral and/or dorsomedial striatum during stereotyped motor behaviors (digging and self-grooming) in BTBR mice compared to that of C57Bl/6J (B6) mice. In addition, the present study examined whether CDD-0102A treatment (1.2 mg/kg) alters striatal glutamate efflux in real-time during the expression of stereotyped motor behaviors.

Results and Discussion

Histology

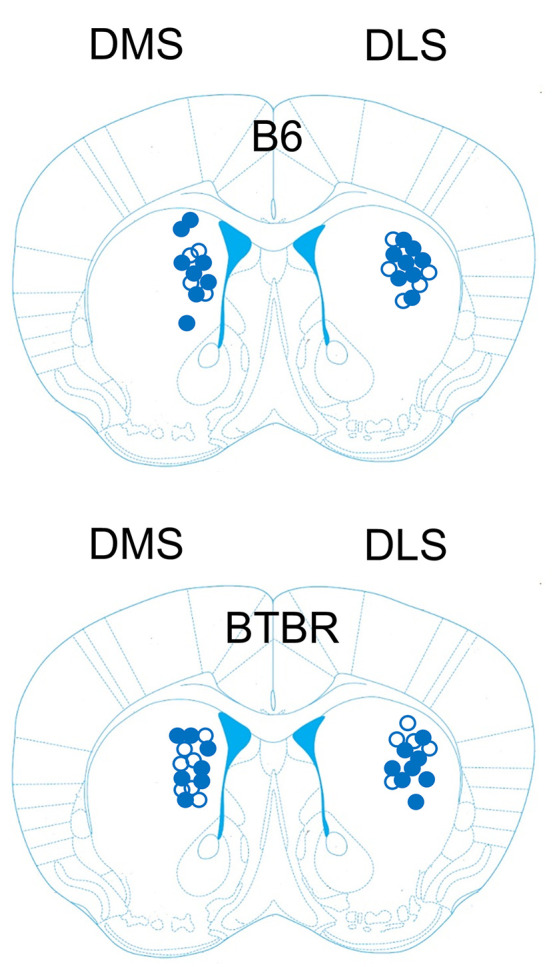

Figure 1 displays the biosensor placements in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial striatum for both strains of mice that were included in the neurochemical and behavioral analyses. Three B6 mice were excluded from the neurochemical and behavioral analyses because of biosensor placements that were dorsal located in the overlying cortex. Three BTBR mice were also excluded from the neurochemical and behavioral analyses because of biosensor placements too ventral located in the nucleus accumbens or ventrolateral striatum.

Figure 1.

Biosensor electrode placements in the dorsal striatum of B6 and BTBR mice included in the neurochemical and behavioral analyses. Mouse brain section reproduced with permission from Paxinos G.; Franklin K. B.. Paxinos and Franklin’s The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, compact 5th ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2019.(48) The black circles (●) represent biosensor placements for mice receiving saline treatment. The open circles (○) represent biosensor placements for mice receiving CDD-0102A treatment (1.2 mg/kg).

Testing

A mouse was restrained, and a glutamate biosensor was inserted through a guide cannula aimed at the dorsolateral or dorsomedial striatum. A mouse was then placed in a rectangular-shaped acrylic container that contained bedding from their home cage along with 15 g of crinkle-cut paper. A mouse was left undisturbed for 3 h to allow biosensor equilibration. After the equilibration period, a mouse received an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of either saline or CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) and placed back into the rectangular-shaped acrylic container for an additional 30 min of habituation. This dose was chosen because a recent study showed this was the most effective dose in reducing stereotyped motor behaviors in BTBR mice.24 After habituation, crinkle-cut paper was removed and stereotyped motor behavior (both self-grooming and digging in bedding material) along with glutamate efflux was recorded for 20 min (see Figure 2 for experimental timeline and Methods for detailed information).

Figure 2.

Timeline of experimental design illustrating the order of the procedures for biosensor recordings combined with behavioral testing. The biosensor was first calibrated and demonstrated to be sensitive and selective to varying concentrations of glutamate. Subsequently, a biosensor was inserted into the dorsal striatum and allowed to equilibrate in the brain for 3 h. After equilibration, a mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of saline or CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg). Thirty minutes after injection the nesting material was removed from the home cage and bouts of digging and grooming were measured along with glutamate efflux for 20 min. Finally, the biosensor was removed from the brain and a postcalibration of the biosensor was conducted.

Glutamate Changes in Dorsolateral Striatum during Stereotyped Motor Behavior

To assess whether different patterns of glutamate efflux from the dorsolateral striatum were associated with a self-grooming bout and/or digging bout, enzyme-mediated biosensor technology was used to measure changes in glutamate concentration during behavior. For the test session, a behavioral bout had to occur for a minimum of 3 s to be considered for neurochemical analysis. The glutamate concentration during the entire duration of a behavioral bout was compared to the glutamate concentration for the 3 s just prior to the initiation of the behavioral bout. Because comparable changes in glutamate were observed during digging and self-grooming bouts within and between mice, the two behaviors were combined to conduct a single analysis for both decrease and increase glutamate changes. In the dorsolateral striatum (Figure 3A), analysis of the glutamate concentration changes during behavioral bouts revealed a significant event (decrease or increase) × strain (B6 or BTBR) × treatment (saline or CDD-0102A) interaction, F1,337 = 34.40, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analyses revealed that saline-treated BTBR mice during behavioral bouts exhibited a significantly greater magnitude change in glutamate concentration compared to that of saline-treated B6 mice for both glutamate decreases (p < 0.001) and increases (p < 0.001). In addition, CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) treatment compared to that of saline treatment in B6 mice significantly augmented the magnitude change in glutamate concentration for decreases during behavior (p = 0.033), but the elevated change for increases in glutamate concentrations was not significantly different than saline during behavior (p = 0.129). In contrast, CDD-0102A treatment compared to that of saline treatment in BTBR mice significantly reduced the magnitude of changes in glutamate concentrations for both decreases (p < 0.001) and increases (p = 0.046).

Figure 3.

Glutamate changes in the dorsolateral striatum during stereotyped motor behavior. (A) Saline-treated B6 and BTBR mice exhibited both decreases and increases in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior with the magnitude change significantly greater in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice. CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally significantly reduced the decreased and increased changes in glutamate for BTBR mice, while the drug significantly increased the magnitude change in B6 mice. **P < 0.001 vs B6-Saline, #P < 0.05 vs BTBR-Saline. CDD = CDD-0102A 1.2 mg/kg. (B) The mean decrease in glutamate concentration across the 3 s preceding a behavioral bout (baseline) and first 3 s of a behavioral bout B6 and BTBR mice. BTBR controls had significantly greater decreases in glutamate efflux vs B6 controls. CDD-0102A treatment reduced the magnitude decrease at second 3 in BTBR mice and significantly potentiated decrease in the first 2 s in B6 mice. (C) The mean increase in glutamate concentration across the 3 s preceding a behavioral bout (baseline) and the first 3 s of a behavioral bout in B6 and BTBR mice. BTBR controls had significantly greater increases in glutamate efflux vs B6 controls. CDD-0102A treatment in BTBR mice significantly attenuated the glutamate increases in the first 3 s of a bout. (D) Mean decrease in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior for short duration and long duration bouts. Short and long bouts were defined as being less than or equal to/greater than the median for that condition, respectively. Changes in glutamate concentration did not differ between short and long bouts within a treatment for both strains. (E) Mean increase in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior for short duration and long duration bouts. Changes in glutamate concentration did not differ between short and long bouts within a treatment for both strains.

To examine whether the differences in glutamate efflux during stereotyped motor behavior emerged early in a bout, an analysis was conducted examining changes in glutamate efflux across the 3 s baseline period and the first 3 s of a behavioral bout. The analyses of decreases and increases in dorsolateral striatal glutamate concentrations are shown in Figure 3B and Figure 3C, respectively. For decreases, the analysis indicated there was a significant strain × treatment × time interaction, F5,1122 = 5.35, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the decrease in glutamate efflux was significantly greater across the beginning 3 s of a bout in BTBR mice injected with saline compared to that of B6 mice injected with saline (p < 0.001). CDD-0102A injection in BTBR mice led to a similar decrease in glutamate efflux during the initial second of a behavioral bout compared to that of BTBR saline-injected mice (p > 0.05) and approached significance during second 2 (p = 0.065), and the decrease in glutamate efflux at 3 s was significantly reduced compared to that of BTBR saline-injected mice (p = 0.0051). In B6 mice, CDD-0102A treatment significantly magnified the decrease in glutamate concentration during the first 2 s of a behavioral bout compared to that of saline treatment (p < 0.05) but not at the third second (p > 0.05).

The analysis for increases in glutamate concentrations during the initial 3 s of a bout (Figure 3C) also revealed a significant strain × treatment × time interaction, F5,900 = 6.99, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the increase in glutamate efflux was significantly greater across the beginning 3 s of a bout in BTBR mice injected with saline compared to that of B6 mice injected with saline (p < 0.001). In BTBR mice, CDD-0102A treatment significantly attenuated the increase in glutamate efflux during each of the first 3 s of a behavioral bout compared to that of saline treatment (p < 0.01). In B6 mice, the difference between drug and saline-treated mice was not significant in the first 3 s of a behavioral bout (p > 0.05).

Another possibility is that the differences in the glutamate concentration change may be principally related to the duration of the behavioral bout. To determine this, a subsequent analysis was conducted in which the median duration of bouts was calculated for each condition, with bouts separated into short duration bouts (less than the median) and long duration bouts (at or greater than the median). The median scores for all groups are shown in Table 1. For decreases in glutamate concentration during behavioral bouts (Figure 3D), there was no significant main effect for bout, F1,183 = 0.06, p > 0.05, indicating that the change in glutamate efflux was similar for short and long duration bouts. There was a significant strain × treatment interaction, F1,183 = 22.05, p < 0.0001 reflecting that BTBR mice injected with saline had significantly greater behaviorally induced glutamate decreases for both short and long duration bouts compared to those of saline-injected B6 mice. For increases in glutamate concentration during behavioral bouts (Figure 3E), a similar pattern appeared in which there was not a significant main effect for bouts, F1,146 = 0.70, p > 0.05. There was a significant strain × treatment interaction, F1,146 = 13.70, p < 0.001 reflecting that the increases in glutamate concentration during behavior were attenuated by CDD-0102A in BTBR mice, yet potentiated by CDD-0102A in B6 mice. Taken together, the results indicate that decreases or increases in glutamate concentration during a behavioral bout were similar for short and long duration bouts within the various groups.

Table 1. Median Bout Duration under Each Condition and Mean Short Bout Duration and Mean Long Bout Duration in Each Condition.

| strain | subregion | treatment | event | median bout duration (s) | mean (SEM) short bout duration (s) | mean (SEM) long bout duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | dorsolateral | saline | decrease | 10 | 6.52 ± 0.31 | 21.81 ± 1.86 |

| B6 | dorsolateral | saline | increase | 9 | 5.67 ± 0.29 | 20.78 ± 2.82 |

| B6 | dorsolateral | CDD | decrease | 19 | 8.85 ± 0.96 | 56.90 ± 9.61 |

| B6 | dorsolateral | CDD | increase | 18 | 9.70 ± 1.07 | 40.92 ± 9.58 |

| BTBR | dorsolateral | saline | decrease | 18.5 | 8.55 ± 1.08 | 44.00 ± 5.84 |

| BTBR | dorsolateral | saline | increase | 13.5 | 7.00 ± 0.77 | 63.45 ± 11.93 |

| BTBR | dorsolateral | CDD | decrease | 14 | 5.71 ± 0.67 | 44.14 ± 10.31 |

| BTBR | dorsolateral | CDD | increase | 8 | 5.00 ± 0.60 | 27.23 ± 10.43 |

| B6 | dorsomedial | saline | decrease | 9 | 5.87 ± 0.24 | 19.27 ± 1.88 |

| B6 | dorsomedial | saline | increase | 8 | 5.32 ± 0.19 | 17.37 ± 1.65 |

| B6 | dorsomedial | CDD | decrease | 12 | 7.80 ± 0.47 | 50.43 ± 8.49 |

| B6 | dorsomedial | CDD | increase | 10.5 | 7.27 ± 0.74 | 38.13 ± 6.70 |

| BTBR | dorsomedial | saline | decrease | 11 | 6.41 ± 0.36 | 41.24 ± 6.29 |

| BTBR | dorsomedial | saline | increase | 14 | 6.86 ± 0.63 | 35.00 ± 5.13 |

| BTBR | dorsomedial | CDD | decrease | 21.5 | 9.00 ± 1.31 | 42.47 ± 4.35 |

| BTBR | dorsomedial | CDD | increase | 12 | 6.06 ± 0.53 | 28.40 ± 4.18 |

Glutamate Changes in Dorsomedial Striatum during Stereotyped Motor Behavior

In the dorsomedial striatum, changes in glutamate concentrations were greater in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice (Figure 4A). However, CDD-0102A treatment had no effect on glutamate concentration changes during stereotyped motor behavior in B6, as well as in BTBR mice. The analysis of the glutamate concentration changes revealed a significant event × strain interaction, F1,397 = 36.84, p < 0.0001, reflecting that the magnitude of change in glutamate efflux was significantly greater in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice. There was also a significant event × treatment interaction, F1,397 = 6.39, p = 0.012 whereby CDD-0102A treatment enhanced decreases in glutamate concentration across both strains.

Figure 4.

Glutamate changes in the dorsomedial striatum during stereotyped motor behavior. (A) Saline-treated B6 and BTBR mice exhibited both decreases and increases in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior with the magnitude change significantly greater in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice. CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally did not affect glutamate changes in either strain. **P < 0.001 vs B6-Saline. CDD = CDD-0102A 1.2 mg/kg. (B) The mean decrease in glutamate concentration across the 3 s preceding a behavioral bout (baseline) and the first 3 s of a behavioral bout B6 and BTBR mice. BTBR controls had significantly greater decreases in glutamate efflux vs B6 controls. (C) The mean increase in glutamate concentration across the 3 s preceding a behavioral bout (baseline) and the first 3 s of a behavioral bout in B6 and BTBR mice. BTBR controls had significantly greater increases in glutamate efflux vs B6 controls. (D) Mean decrease in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior for short duration and long duration bouts. Short and long bouts were defined as being less than or equal to/greater than the median for that condition, respectively. Changes in glutamate concentration did not differ between short and long bouts within a treatment for both strains. (E) Mean increase in glutamate during stereotyped motor behavior for short duration and long duration bouts. Changes in glutamate concentration did not differ between short and long bouts within a treatment for both strains.

Examining the first 3 s of a behavioral bout revealed a similar pattern of findings compared to measuring the entire bout duration for both decreases (Figure 4B) and increases (Figure 4C) in glutamate efflux. For decreases, the analysis revealed that all main effects (time, strain, and treatment) were significantly different (p < 0.01). In addition, there was a significant time × strain interaction, F5,1242 = 3.16, p = 0.0078, reflecting that decreases in glutamate concentrations were significantly greater during the first 3 s of a behavioral bout period in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice.

Similar to that observed with decreases in glutamate concentration, increases in glutamate concentration showed a greater magnitude change during the initial 3 s of a bout in BTBR mice versus B6 mice. The analysis indicated that all main effects were significantly different (p < 0.01). In addition, there was a significant time × strain interaction, F5,1140 = 7.18, p < 0.0001, whereby BTBR mice displayed significantly greater glutamate increases during the behavioral bout than those of B6 mice. There was also a significant time × treatment interaction, F5,1140 = 2.43, p = 0.034, reflecting that CDD-0102A treatment led to greater glutamate efflux during the behavioral bout compared to that of baseline.

An analysis was conducted to examine whether differences in glutamate concentration change during stereotyped motor behavior occurred due to the duration of the behavioral bout. For decreases in glutamate concentration during behavioral bouts (Figure 4D), there was no significant main effect for bout, F1,203 = 0.51, p > 0.05, nor a bout interaction with other factors (strain and treatment) [p > 0.05]. For increases in glutamate concentration during behavioral bouts (Figure 4E), a similar pattern of results was observed in which there was no significant main effect for the bout, F1,186 = 0.01, p > 0.05, nor a bout interaction with other factors (p > 0.05). Thus, similar to that observed from the dorsolateral striatum, the results indicate that decreases or increases in glutamate concentration during a behavioral bout were similar for short and long duration bouts across all groups.

CDD-0102A Effects on Stereotyped Motor Behavior

The results from the 20 min behavioral test following ip injections of CDD-0102A are shown in Figure 5A. Mice from each strain that received the same treatment with a biosensor in the dorsomedial or dorsolateral striatum were combined into a single group, as a systemic injection had a similar effect on behavior irrespective of biosensor location (see Figure S1A,B). Saline-treated B6 mice exhibited digging behavior (∼160 s) for about 1 min longer than grooming behavior (∼100 s). In contrast, saline-treated BTBR mice displayed a greater amount of grooming behavior (∼265 s) than digging behavior (∼50 s). In B6 mice, CDD-0102A treatment reduced digging behavior but increased grooming behavior. In BTBR mice, CDD-0102A slightly increased digging behavior but reduced grooming behavior by half. The analysis revealed a significant strain × treatment × behavior interaction, F1,98 = 38.81, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analyses revealed that grooming time in saline-treated BTBR mice was significantly greater than that of saline-treated B6 mice and digging time in saline-treated BTBR mice (p < 0.01). CDD-0102A treatment compared to saline treatment in B6 mice significantly increased grooming duration (p < 0.01). Further, in B6 mice, CDD-0102A significantly reduced digging time compared to that of saline treatment (p = 0.042). CDD-0102A treatment compared to saline treatment in BTBR mice significantly reduced grooming time (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

CDD-0102A effects on stereotyped motor behavior. (A) CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) significantly reduced grooming behavior in BTBR mice while significantly increasing grooming behavior in B6 mice. **P < 0.001 vs B6-Saline, ##P < 0.01 vs BTBR-Saline. (B) CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) effect on mean grooming bout duration. BTBR mice had higher mean grooming bout durations than B6 mice. CDD-0102A treatment did not affect mean bout duration. (C) CDD-0102A effect on total number of grooming bouts. Drug treatment significantly increased the total number of grooming bouts in B6 mice and significantly decreased the total number of grooming bouts in BTBR mice. **P < 0.001 vs B6-Saline, #P < 0.05 vs BTBR-Saline.

As the drug affected the total time spent self-grooming in both B6 and BTBR mice, subsequent analyses were conducted to determine whether CDD-0102A treatment affected the average grooming bout time and/or number of grooming bouts. The results from the mean duration of grooming bouts for the various groups are shown in Figure 5B. CDD-0102A treatment led to an increase in grooming bout duration for B6 mice, but the drug did not affect bout duration in BTBR mice. However, a two-way ANOVA indicated that the only significant effect was for strain, F1,45 = 7.46, p = 0.009, reflecting that grooming bout duration was higher in BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice. For the total number of grooming bouts (Figure 5C), the analysis indicated there was a significant strain × treatment interaction, F1,49 = 19.64, p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analyses indicated that in B6 mice, CDD-0102A treatment significantly increased the number of grooming bouts compared to saline treatment (p < 0.01). Conversely, in BTBR mice, CDD-0102A treatment significantly reduced the number of grooming bouts compared to that following a saline injection (p = 0.021). Thus, the predominant effect of CDD-0102A on grooming time in both strains was through changes in the number of grooming bouts.

Conclusions and Discussion

The present experiments demonstrate that glutamate concentrations from the dorsal striatum lead to both decreases and increases in glutamate concentrations during stereotyped motor behavior. The specific stereotyped motor behaviors measured included digging and self-grooming which are commonly observed to be elevated in mouse models of autism.11,14,24 Neither the direction nor the magnitude of change in glutamate concentration was related to the specific behavior expressed (digging or self-grooming). In addition, neither the direction nor magnitude of change was related to behavioral bout duration. The dynamic changes in striatal glutamate concentrations during stereotyped motor behavior are comparable to dynamic changes in rat hippocampus for glutamate and GABA during various behaviors using biosensor technology.25 A past study using in vivo microdialysis found that glutamate efflux from the dorsolateral striatum in deer mice selectively increased during stereotyped motor behavior, i.e., jumping and grooming, particularly when rearing behavior preceded the jumping and grooming behavior.14 One possibility is that the difference in a unidirectional change in dorsolateral striatal glutamate versus bidirectional change observed in the present study is due to a difference in mouse strains used. An alternative possibility is that the biosensor technique used in the present study has 1 s resolution and thus provides a clear temporal separation between the initiation and termination of a stereotyped motor behavior, thereby more definitively identifying dynamic changes in glutamate concentration than in vivo microdialysis methods afford. Future studies using the biosensor approach to examine glutamate changes from the striatum, as well as other brain areas, in additional mouse models of autism could help elucidate whether comparable changes in glutamate output occur during stereotyped motor behavior.

While both B6 and BTBR mice displayed decreases and increases in glutamate concentrations during stereotyped behavior, the magnitude of changes was significantly greater in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial striatum for BTBR mice compared with that of B6 mice. This pattern suggests that glutamate signaling in these areas is dysregulated in BTBR mice. Despite the greater magnitude of changes in glutamate concentration, a systemic injection with the partial M1 muscarinic agonist CDD-0102A significantly dampened the magnitude of change in the BTBR dorsolateral striatum but not the dorsomedial striatum. A past study that selectively ablated striatal cholinergic interneurons in the dorsal striatum found this led to increased stereotyped motor behavior and perseverative responding in mice.26 The same loss of striatal cholinergic interneurons resulted in significantly enhanced evoked responses from the dorsolateral striatum when stimulating premotor and prelimbic cortical areas, but the same cortical stimulation did not affect evoked responses when recording from the dorsomedial striatum.26 Thus, loss of striatal cholinergic interneurons increased stereotyped motor behavior and altered corticostriatal functional connectivity selectively in the dorsolateral striatum. Related to the present findings, BTBR mice may have altered functional connectivity from cortical areas that project to the dorsolateral striatum due to compromised striatal cholinergic interneuron activity, leading to dysregulated glutamate signaling and stereotyped motor behaviors. Further, stimulating M1 muscarinic receptors with M1 muscarinic partial agonists like CDD-0102A may be able to concomitantly attenuate the dysregulated glutamate signaling in the dorsolateral striatum and stereotyped motor behavior.

For BTBR mice compared to that of B6 mice, baseline muscarinic receptor activity may be lower in striatal circuits that leads to increased stereotyped motor behaviors in which a partial M1 muscarinic agonist such as CDD-0102A enhances muscarinic receptor activity to more effectively modulate striatal glutamate efflux and affect stereotyped motor behavior. Because of the possible differences in baseline muscarinic receptor responses, an effective dose of CDD-0102A, i.e., 1.2 mg/kg, in BTBR mice may not be effective in B6 mice.

In contrast to BTBR mice, CDD-0102A treatment in B6 mice led to greater decreases and increases in dorsolateral striatal glutamate efflux during stereotyped motor behavior. This was unexpected as a recent experiment showed that CDD-0102A 1.2 mg/kg, as used in the present study, did not significantly affect digging or grooming behavior in B6 mice when nesting material was removed.24 However, it became clear that mice being restricted of movement with the biosensor apparatus changed the phenotype for both mouse strains. More specifically, when mice are untethered in the nesting removal test, the predominant behavior expressed is digging behavior with a minimal amount of self-grooming behavior exhibited.24,27 In the current study, B6 controls displayed self-grooming behavior that approached a total of 2 min in duration, while BTBR controls exhibited self-grooming behavior for approximately 4 min. Treating B6 mice with CDD-0102A magnified the glutamate changes selectively in the dorsolateral striatum during behavioral bouts and shifted mice to express self-grooming behavior significantly more than digging behavior. This combined pattern was comparable to that observed with saline-treated BTBR mice, particularly when measuring glutamate efflux from the dorsolateral striatum. One possibility is that the pattern observed in B6 mice resulted from an interaction of stress and M1 muscarinic receptor activation. This is because stress can increase stereotyped motor behavior15,28,29 and either decreasing or increasing cholinergic signaling in the dorsolateral striatum interacts with stress to affect stereotypies. A future experiment could further investigate this idea by determining whether a selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist has the opposite effects of CDD-0102A in these conditions. In addition, to more completely characterize the effects of M1 muscarinic receptor activity on glutamate efflux and behavior, it will be important to examine in future studies a range of CDD-0102A doses in B6 and BTBR mice.

Although both decreases and increases in striatal glutamate efflux occurred during behavioral bouts in all groups, for most bouts a decrease or increase did not last for the entire bout but would fluctuate, to varying degrees, across the behavioral bout. At the same time, when stereotyped motor behavior had an accompanying decrease or increase in glutamate efflux, the direction change emerged early in a bout when examining the first 3 s of a bout. This was the case for all groups, including CDD-0102A effects on glutamate efflux changes in the dorsolateral striatum for both mouse strains. Thus, the initial direction change in striatal glutamate efflux during a behavioral bout was reflective of the direction of change for the overall bout duration.

Glutamate content in the striatum can originate from various cortical and thalamic inputs30 but also from interneurons.31 It is unclear to what degree the various sources of glutamate contribute to the neurochemical signal detected by the biosensor. Previous results have shown that stimulation of corticostriatal synapses can lead to increased glutamate efflux while stimulation of thalamostriatal synapses produces decreases in glutamate output.32 Another study stimulating distinct thalamic inputs to the striatum found opposite effects on paired-pulse ratios,30 suggesting that different inputs may lead to decreases or increases in glutamate transmission in the striatum. Taken together, this raises the possibility that specific inputs from the cortex and/or thalamus to the striatum may lead to increases or decreases in glutamate efflux that predominate during the expression of stereotyped motor behavior.

A different but potentially complementary explanation for why decreases and increases in striatal glutamate content occurred during stereotyped motor behavior may be related to the mouse activity during the baseline period. In particular, mice during a baseline period (3 s prior to initiation of stereotyped motor behavior) were either stationary, turning, moving, or coming back down from rearing. These behaviors during baseline recording periods were observed for bouts that resulted in decreases and increases in glutamate efflux, suggesting that the behavior a mouse transitioned from was not predictive of the change in glutamate direction.

The present results suggest that activation of M1 muscarinic receptors with CDD-0102A modifies glutamate efflux in the dorsolateral striatum to affect self-grooming behavior. Because M1 muscarinic receptors are expressed in both cerebral cortex and thalamus,33,34 one possibility is that CDD-0102A principally acts in these brain areas to affect dorsolateral striatal glutamate efflux. Muscarinic cholinergic receptor stimulation of cerebral cortex increases synchronization in local cortical circuits among both pyramidal neurons and interneurons that are blocked by a M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist.23 Related to the CDD-0102A effect in BTBR mice, M1 muscarinic receptor activation may dynamically synchronize excitatory inputs to the striatum that originate from the cortex and/or thalamus to attenuate changes in glutamate efflux during self-grooming behavior. An alternative is that CDD-0102A principally affects striatal activity directly to influence glutamate efflux and self-grooming behavior. This is because a previous study found that direct injection of CDD-0102A into the dorsal striatum attenuates stereotyped motor behavior24 and M1 muscarinic receptors are highly expressed on medium spiny output neurons. Moreover, M1 muscarinic receptor activation enhances synchronization of a large number of medium spiny neurons.35 This modification of striatal output activity may ultimately regulate the excitatory input to the dorsolateral striatum to change the expression of self-grooming behavior. Still another possibility is that CDD-0102A stimulates M1 muscarinic receptors along multiple nodes in cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic networks to concomitantly regulate striatal glutamate signaling and stereotyped motor behavior.

While a CDD-0102A injection significantly reduced self-grooming time in BTBR mice, the drug did not affect the average duration of a self-grooming bout. Conversely, CDD-0102A increased self-grooming time in B6 mice. Although not statistically significant, the average duration of a self-grooming bout doubled in B6 mice. Consistent across both strains is that the drug significantly affected the number of bouts. Specifically, CDD-0102A treatment significantly enhanced the number of grooming bouts in B6 mice and decreased the number of grooming bouts in BTBR mice. This finding may relate to the partial agonist properties of CDD-0102A. A partial agonist would enhance muscarinic cholinergic activity under conditions where baseline activity is low yet suppress muscarinic cholinergic activity in conditions when such activity is elevated. Further, this pattern of results might suggest that M1 muscarinic receptors play a role in setting a “threshold” for the initiation of a self-grooming bout. In the case of BTBR mice, CDD-0102A dampening the magnitude change in dorsolateral striatal glutamate efflux may not reduce bout duration if initiated but instead decrease the probability that a bout occurs.

CDD-0102A acts at the orthosteric site of the M1 muscarinic receptor. Drugs that selectively target the allosteric site for M1 muscarinic receptors also exist that have the potential of effectively treating core features in ASD.36,37 Importantly, there are different positive allosteric modulators selective for the M1 muscarinic receptor.36,38 The impact of allosteric modulation can be complicated, however, by the type of allosteric modulator. If a positive allosteric modulator works mainly by increasing the affinity (and thus potency) of acetylcholine, it may be more effective under conditions where muscarinic receptor activity is high. If a positive allosteric modulator works mainly by increasing the efficacy (maximal responses) of acetylcholine, it may elevate acetylcholine responses in systems with low baseline activity yet have minimal effects in systems with higher levels of activity. These different mechanisms of positive allosteric modulators can help elucidate the muscarinic receptor pathophysiology underlying behavioral deficits, as well as provide different options for most effectively treating disorders affected by M1 muscarinic receptor dysfunction.

The present study found that increasing M1 muscarinic receptor stimulation dynamically affected striatal glutamate efflux. The idea that an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling in the brain may underlie autism has garnered significant attention.16,17 The hypothesis might suggest that glutamate efflux is either increased or decreased with expression of a repetitive motor behavior but not both. Because significant changes in both decreases and increases in striatal glutamate efflux were observed in the BTBR mouse model of autism, the findings suggest that homeostatic mechanisms may be compromised leading to elevated stereotyped motor behavior.16 Moreover, stimulation of M1 muscarinic receptors attenuated the magnitude of the bidirectional change in striatal glutamate efflux, along with repetitive motor behavior in BTBR mice. These results suggest that activating M1 muscarinic receptors improves a functional homeostasis16 in the striatum and related circuitry to affect repetitive motor behaviors.

Subchronic treatment with CDD-0102A also attenuates repetitive motor behaviors.24 Future studies that investigate how subchronic treatment with CDD-0102A and other M1 muscarinic agonists or positive allosteric modulators impact striatal glutamate efflux and repetitive behaviors could help determine whether repeated dosing produces similar or distinct effects as compared to acute treatment. In addition, dorsomedial striatal glutamate efflux in BTBR mice is also dysregulated compared to that of B6 mice despite CDD-0102A treatment not modifying dorsomedial striatal glutamate efflux during repetitive motor behaviors. However, there is significant evidence that the dorsomedial striatum supports behavioral flexibility39−42 and M1 muscarinic receptors in the dorsomedial striatum play a role in behavioral flexibility.43,44 In addition, BTBR mice exhibit behavioral flexibility impairments comparable to ASD individuals4,5,7,45 and CDD-0102A treatment can alleviate the behavioral flexibility deficit in BTBR mice.24 Thus, dysregulated glutamate signaling in the dorsomedial striatum of BTBR mice may contribute to a behavioral flexibility deficit in which treatment with CDD-0102A may concomitantly modify dorsomedial striatal glutamate efflux and behavioral flexibility impairment. Overall, a more comprehensive investigation of how stimulating M1 muscarinic receptors affects brain glutamate signaling during a range of autism-like behaviors can advance an understanding of whether targeting M1 muscarinic receptors is an effective therapeutic strategy for alleviating RRBs in ASD.

Methods

Subjects

Experiments were conducted with male and female C57BL/6J (B6) along with male and female BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice (10–12 weeks of age). Mice were bred in the laboratory with initial breeders acquired from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were individually housed in plastic cages (28 cm wide × 17 cm long × 12 cm high) in a humidity (32%) and temperature (23 °C) controlled room and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:30 a.m.). Animal care and experiments were followed in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois Chicago.

Surgical Procedure

Biosensor technology was used to measure the real-time change of glutamate release in the dorsal striatum of freely moving mice. Mice aged 8–10 weeks received stereotaxic surgery to implant a cannula aimed at the dorsomedial or dorsolateral striatum.

Prior to surgery, each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). A plastic guide cannula was stereotaxically implanted aimed at the dorsomedial striatum (0.8 mm anterior to the bregma, +1.8 mm lateral, 1.2 mm below the skull) or the dorsolateral striatum (0.8 mm anterior to the bregma, +2.3 mm lateral, 1.2 mm below the skull). A grounding screw attached to a headmount connector (Pinnacle Technology, Lawrence, KS, USA) was inserted slightly anterior to the interaural line. The guide cannula and head mount connector were secured in place with dental cement. To minimize pain or discomfort, mice received subcutaneous administration of meloxicam after surgery and for 2 days subsequently. Mice were allowed at least 8 days to recover prior to the start of glutamate biosensor recording with behavioral testing.

Behavioral Testing with Biosensor Recording

The glutamate biosensor (model 7004, Pinnacle Technology Inc., Lawrence, KS, USA) description and setup have been reported in detail previously.46 Before biosensor insertion, each biosensor was calibrated in vitro to verify the glutamate sensitivity and interference rejection from ascorbic acid. Subsequently, a mouse was restrained and the biosensor inserted through the guide cannula. A mouse was then placed in a rectangular-shaped acrylic container (22 cm W × 32 cm L × 32 cm H) that contained approximately 120 g of Sani-chips bedding (Teklad 7090, Madison, WI, USA) from the home cage of the mouse and 15 g of crinkle-cut paper nesting material (The Andersons, Maumee, OH, USA). Data acquisition started after insertion of the biosensor. The sensor signal was processed by the Sirenia software system for data acquisition, storage, and analysis as part of the Pinnacle biosensor system. Changes in glutamate concentration were recorded as current (nA) every second. A mouse was left undisturbed for 3 h to allow biosensor equilibration. After the equilibration period, a mouse received an ip injection of either saline or CDD-0102A (1.2 mg/kg) and placed back into the rectangular-shaped acrylic container for an additional 30 min of habituation. CDD-0102A is the hydrochloride salt of 3-ethyl-5-(1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazole. It was synthesized using slight modifications of methods reported previously.47 The sample was provided by Dr. William S. Messer, Jr. from the University of Toledo. The dose was chosen based on a previous study showing that 1.2 mg/kg CDD-0102A significantly reduced digging and grooming behavior in BTBR mice.20 Directly preceding the 20 min behavioral test, 120 g of additional fresh bedding was added to the rectangular-shaped acrylic container, and the nesting material was removed. Then stereotyped motor behavior (i.e., digging and grooming) and glutamate activity were recorded for 20 min in vivo. Digging was defined as a mouse repetitively moving their forepaws or hind legs into the bedding to displace it underneath the body or to the side. Grooming included any of the following: paw/tail/genital licking, snout/face/head washing, body grooming, or scratching body with any limb. Two different individuals scored the durations of digging and grooming bouts for all mice: one during the experimental test and one subsequently using the video recording. Any discrepancies in scoring a bout were reexamined together to resolve scoring differences. Scorers were not blind to the treatment. After completion of the experiment, the biosensor was calibrated again to ensure continued sensitivity to glutamate while rejecting ascorbic acid.

For the dorsolateral striatal study, the following groups were included: (1) B6 saline, n = 8; (2) B6 CDD-0102A, n = 5; (3) BTBR saline, n = 8, and (4) BTBR CDD-0102A, n = 5. In the dorsomedial striatal study, the groups were as follows: (1) B6 saline, n = 8; (2) B6 CDD-0102A, n = 5; (3) BTBR saline, n = 7, and (4) BTBR CDD-0102A, n = 7.

Histology

Following the completion of the experiment, mice received a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). Mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline followed by neutral buffered formalin (10%). Fixed brains were sectioned on a cryostat (40 μm), and sections containing the biosensor tract were identified under light microscopy with assistance from a mouse brain atlas.48

Data and Statistical Analyses

A linear regression analysis was applied to determine the current to glutamate conversion factor. Glutamate concentrations were calculated based on postcalibration data. To determine the glutamate response during digging or self-grooming behavior, the baseline current value (calculated by averaging the 3 s period immediately prior to digging or self-grooming behavior) was subtracted from the value during the duration of a digging or self-grooming bout. A bout had to occur for a minimum of 3 s to be included in the analysis. For a small number of bouts, a mouse’s headmount tapped against a wall of the cage, causing a rapid deflection of the glutamate signal. These bouts were not included in the glutamate concentration analyses but still included in the behavioral analyses. All analyses for glutamate concentrations, raw glutamate data, and behavioral data are available at DOI: doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6597052.. A three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to determine whether there were significant differences in glutamate concentration changes among strain, treatment, and event (decrease vs increase in glutamate) factors. A separate three-way ANOVA was conducted for biosensors in the dorsolateral striatum and dorsomedial striatum. To determine if there were differences between strains and/or treatment on the duration of a stereotyped motor behavior bout, the median bout duration was determined for each group with bouts shorter than the median considered short bouts and bouts at the median or longer considered long bouts. A three-way ANOVA examined whether there were significant differences in glutamate concentration across strain, treatment, and bout duration. Separate three-way ANOVAs were conducted for decreases and increases in glutamate concentration in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial striatum. In addition to the glutamate measurements, the total time a mouse spent digging and grooming was calculated. A three-way ANOVA determined whether there were significant differences among strain, treatment, and behavior type (grooming or digging). Separate two-way ANOVAs were conducted to elucidate whether there were significant differences across strain and treatment for the average grooming bout duration and total grooming bouts. Post-hoc tests using a Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons were used to determine the significance between specific groups for the analyses described above.

To determine whether changes in glutamate concentration during a behavioral bout emerged during the first 3 s, a three-way ANOVA with repeated measures examined changes in glutamate concentration across the 3 s baseline period and the first 3 s of a bout differed by strain and/or treatment. Separate analyses were conducted for decreases and increases in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial striatum. Post-hoc Tukey tests were conducted to determine whether specific groups significantly differed at specific time points.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roberto Ocampo for technical assistance in carrying out the experiments. We thank Dr. Mitchell F. Roitman for suggestions on data analyses. This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (Grant HD084953).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00260.

Additional results comparing digging behavior (Figure S1A) and grooming behavior (Figure S1B) for mice with a biosensor in the dorsomedial striatum vs dorsolateral striatum (PDF)

Author Contributions

Pamela Teneqexhi contributed to stereotaxic surgery, testing of experimental animals, histology, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Alina Khalid contributed to histology, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Khalin E. Nisbett contributed to stereotaxic surgery, testing of experimental animals, data analysis, and histology. Greeshma A. Job contributed to stereotaxic surgery, testing of experimental animals, and data analysis. William S. Messer contributed to development of the experimental design, and writing of the manuscript. Michael E. Ragozzino contributed to development of experimental design, data analysis, histology, and writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Dr. William S. Messer holds patents for the use of muscarinic agonists in the treatment of neurological disorders and is the founder and president of Psyneurgy Pharmaceuticals LLC. Dr. Michael Ragozzino holds a patent for use of muscarinic agonists in the treatment of neurological disorders.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Chemical Neuroscience special issue “Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Amercian Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Chaulagain A.; Pedersen S. A.; Lydersen S.; Leventhal B. L.; Szatmari P.; Skokauskas N.; et al. Pharmacotherapy of restricted/repetitive behavior in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 121. 10.1186/s12888-020-2477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. S.; Nasir M.; Farhat L. C.; Kook M.; Artukoglu B. B.; Bloch M. H. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2021, 60 (1), 35–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz A. M.; Ragozzino M. E.; Mosconi M. W.; Shrestha S.; Cook E. H.; Sweeney J. A. Reduced behavioral flexibility in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology 2013, 27, 152–160. 10.1037/a0031721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo D. A.; Jones J. H.; Sweeney J. A.; Ragozzino M. E. Differences in BTBR T+ tf/J and C57BL/6J mice on probabilistic reversal learning and stereotyped behaviors. Behav Brain Res. 2012, 227, 64–72. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. L.; Tolu S. S.; Barkan C. L.; Crawley J. N. Repetitive self-grooming behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism is blocked by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 976–989. 10.1038/npp.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo D. A.; Cuevas L.; Dunn J. T.; Sweeney J. A.; Ragozzino M. E. The adenosine A2A receptor agonist, CGS 21680, attenuates a probabilistic reversal learning deficit and elevated grooming behavior in BTBR mice. Autism Research 2018, 11, 223–233. 10.1002/aur.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo D. A.; Oliver B.; Pahua A.; Hitchcock K.; Bykowski A.; Tice D.; Musleh A.; Ryan B. C. Serotonin 6 receptor blockade reduces repetitive behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2021, 200, 173076. 10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coretti L.; Cristiano C.; Florio E.; Scala G.; Lama A.; Keller S.; Cuomo M.; Russo R.; Pero R.; Paciello O.; Mattace Raso G.; et al. Sex-related alterations of gut microbiota composition in the BTBR mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45356. 10.1038/srep45356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrisciano F.; Locci V.; Dong E.; Nicoletti F.; Guidotti A.; Grayson D. R. Altered Expression and in vivo Activity of mGlu5 variant a Receptors in the striatum of BTBR mice: Novel insights into the pathophysiology of adult idiopathic forms of autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 2354. 10.2174/1567202619999220209112609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones B. A.; Pitcher M. N.; Fleming W. T.; Libby A.; Diethorn E. J.; Haye A. E.; Gould E.; et al. Perineuronal nets in the dorsomedial striatum contribute to behavioral dysfunction in mouse models of excessive repetitive behavior. Biol. Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2022, 2, 460. 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal W. G.; Langen M.; van Dijk S.; Mensen V. T.; Durston S. DRD3 gene and striatum in autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 2015, 206, 431–432. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E.; Anagnostou E.; Chaplin W.; Esposito K.; Haznedar M. M.; Licalzi E.; Buchsbaum M.; et al. Striatal volume on magnetic resonance imaging and repetitive behaviors in autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 226–232. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti M. F.; Watson C. J.; Kennedy R. T.; Yang M.; Lewis M. H. Behavior-related alterations of striatal neurochemistry in a mouse model of stereotyped movement disorder. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2004, 77, 501–507. 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden J. R.; Lacey C. J.; Lee T.; Bowden H. A.; Graybiel A. M. Severe drug-induced repetitive behaviors and striatal overexpression of VAChT in ChAT-ChR2-EYFP BAC transgenic mice. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8, 57. 10.3389/fncir.2014.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. B.; Valakh V. Excitatory/inhibitory balance and circuit homeostasis in autism spectrum disorders. Neuron 2015, 87, 684–698. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.; Lee J.; Kim E. Excitation/inhibition imbalance in animal models of autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 838–847. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S. D.; Shaw D. W.; Artru A. A.; Richards T. L.; Gardner J.; Dawson G.; Posse S.; Dager S. R. Regional brain chemical alterations in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Neurology 2003, 60, 100–107. 10.1212/WNL.60.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan T. H.; Abdelrahman H. M.; Abdel Fattah N. R.; El-Masry N. M.; Hashim H. M.; El-Gerby K. M.; Abdel Fattah N. R. Blood and brain glutamate levels in children with autistic disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder 2013, 7, 541–548. 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horder J.; Lavender T.; Mendez M. A.; O’Gorman R.; Daly E.; Craig M. C.; Lythgoe D. J.; Barker G. J.; Murphy D. G. Reduced subcortical glutamate/glutamine in adults with autism spectrum disorders: a [(1)H]MRS study. Translational Psychiatry 2013, 3, e279. 10.1038/tp.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horder J.; Petrinovic M. M.; Mendez M. A.; Bruns A.; Takumi T.; Spooren W.; Barker G. J.; Künnecke B.; Murphy D. G. Glutamate and GABA in autism spectrum disorder—a translational magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in man and rodent models. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 106. 10.1038/s41398-018-0155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H. H.; Mulcare S. P.; Hilário M. R.; Clouse E.; Holloway T.; Davis M. I.; Costa R. M.; et al. Dynamic reorganization of striatal circuits during the acquisition and consolidation of a skill. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 333–341. 10.1038/nn.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S.; Kawaguchi Y. Slow synchronized bursts of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (0.1–0.3 Hz) by cholinergic stimulation in the rat frontal cortex in vitro. Neuroscience 2001, 107, 551–560. 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athnaiel O.; Job G. A.; Ocampo R.; Teneqexhi P.; Messer W. S. Jr; Ragozzino M. E. Effects of the partial M1 muscarinic cholinergic receptor agonist CDD-0102A on stereotyped motor behaviors and reversal learning in the BTBR mouse model of autism. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 25, 64–74. 10.1093/ijnp/pyab079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty P. T.; Hossain I.; Gong C.; Ponder K. A.; Pati S.; Arumugam P. U.; Murray T. A. Novel microwire-based biosensor probe for simultaneous real-time measurement of glutamate and GABA dynamics in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12777. 10.1038/s41598-020-69636-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos Y. V.; Braz B. Y.; Beccaria J. P.; Murer M. G.; Belforte J. E. Compulsive social behavior emerges after selective ablation of striatal cholinergic interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 2849–2858. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3460-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacivita E.; Niso M.; Stama M. L.; Arzuaga A.; Altamura C.; Costa L.; Desaphy J. F.; Ragozzino M. E.; Ciranna L.; Leopoldo M. Privileged scaffold-based design to identify a novel drug-like 5-HT7 receptor-preferring agonist to target Fragile X syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112395. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.; Kobets A.; Du J. C.; Lennington J.; Li L.; Banasr M.; Duman R. S.; Vaccarino F. M.; DiLeone R. J.; Pittenger C. Targeted ablation of cholinergic interneurons in the dorsolateral striatum produces behavioral manifestations of Tourette syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 893–898. 10.1073/pnas.1419533112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.; Li L.; Pittenger C. Ablation of fast-spiking interneurons in the dorsal striatum, recapitulating abnormalities seen post-mortem in Tourette syndrome, produces anxiety and elevated grooming. Neuroscience 2016, 324, 321–329. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunnicutt B. J.; Jongbloets B. C.; Birdsong W. T.; Gertz K. J.; Zhong H.; Mao T. A comprehensive excitatory input map of the striatum reveals novel functional organization. eLife 2016, 5, e19103. 10.7554/eLife.19103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley M. J.; Gittis A. H.; Oldenburg I. A.; Balthasar N.; Seal R. P.; Edwards R. H.; Lowell B. B.; Kreitzer A. C.; Sabatini B. L. Cholinergic interneurons mediate fast VGluT3-dependent glutamatergic transmission in the striatum. PloS One 2011, 6, e19155. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J.; Peterson J. D.; Surmeier D. J. Corticostriatal and thalamostriatal synapses have distinctive properties. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6483–6492. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0435-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert F. J.; Tran L. P. Regional distribution of M1, M2 and non-M1, non-M2 subtypes of muscarinic binding sites in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990, 255, 1148–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli L. A.; Levey A. I. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Progress in Brain Research 2004, 145, 59–66. 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Reid L.; Tecuapetla F.; Vautrelle N.; Hernandez A.; Vergara R.; Galarraga E.; Bargas J. Muscarinic enhancement of persistent sodium current synchronizes striatal medium spiny neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2009, 102, 682–690. 10.1152/jn.00134.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Seager M. A.; Wittmann M.; Jacobson M.; Bickel D.; Burno M.; Jones K.; Graufelds V. K.; Xu G.; Pearson M.; McCampbell A.; Gaspar R.; Shughrue P.; Danziger A.; Regan C.; Flick R.; Pascarella D.; Garson S.; Doran S.; Ray W. J.; et al. Selective acti-vation of the M1muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allo-steric potentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 15950–15955. 10.1073/pnas.0900903106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. T.; van der Westhuizen E. T.; Langmead C. J.; Tobin A. B.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A.; Valant C. Opportunities and challenges for the development of M1 muscarinic receptor positive allosteric modulators in the treatment for neurocognitive deficits. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 10.1111/bph.15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S. P.; Dickerson J. W.; Cho H. P.; Xiang Z.; Maksymetz J.; Remke D. H.; Lv X.; Doyle C. A.; Rajan D. H.; Niswender C. M.; Engers D. W.; et al. M1-positive allosteric modulators lacking agonist activity provide the optimal profile for enhancing cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1763–1771. 10.1038/s41386-018-0033-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. M.; Ragozzino M. E. Contralateral disconnection of the rat prelimbic cortex and dorsomedial striatum impairs cue-guided behavioral switching. Learning & Memory 2014, 21, 368–379. 10.1101/lm.034819.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino M. E.; Mohler E. G.; Prior M.; Palencia C. A.; Rozman S. Acetylcholine activity in selective striatal regions supports behavioral flexibility. Neurobiology of learning and memory 2009, 91, 13–22. 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañé A.; Theobald D. E.; Robbins T. W. Selective lesions of the dorsomedial striatum impair serial spatial reversal learning in rats. Behavioural brain research 2010, 210, 74–83. 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren H. S.; Wickens R.; Tait D. S.; Brown V. J.; Dunnett S. B. Lesions of the dorsomedial striatum impair formation of attentional set in rats. Neuropharmacology 2013, 71, 148–153. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool M. F.; Patel S.; Talati R.; Ragozzino M. E. Differential involvement of M1-type and M4-type muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the dorsomedial striatum in task switching. Neurobiology of learning and memory 2008, 89, 114–124. 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzavos A.; Jih J.; Ragozzino M. E. Differential effects of M1 muscarinic receptor blockade and nicotinic receptor blockade in the dorsomedial striatum on response reversal learning. Behavioural brain research 2004, 154, 245–253. 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo D. A.; Rivera E.; Cook E. H. Jr; Sweeney J. A.; Ragozzino M. E. 5HT2A receptor blockade in dorsomedial striatum reduces repetitive behaviors in BTBR mice. Genes, Brain and Behavior 2017, 16, 342–351. 10.1111/gbb.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor E.; Aillon D. V.; Gabbert S.; Harmon H.; Johnson D. A.; Wilson G. S.; Petillo P. A. Simultaneous real-time measurement of EEG/EMG and L-glutamate in mice: A biosensor study of neuronal activity during sleep. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2011, 656, 106–113. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar P. G.; Durant G. J.; Fang Z.; Abuh Y. F.; el-Assadi A. A.; Ngur D. O.; Periyasamy S.; Hoss W. P.; Messer W. S. Jr Design, synthesis, and neurochemical evaluation of 5-(3-alkyl-1,2,4- oxadiazol-5-yl)-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidines as M1 muscarinic receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 842–847. 10.1021/jm00059a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G.; Franklin K. B.. Paxinos and Franklin’s the Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Academic Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.