Abstract

This article has been corrected. Please see J Manag Care Spec Pharmacy. 23(5):601-04.

BACKGROUND:

Global pharmaceutical sales for anticancer drugs were $74.4 billion in 2014, ranking first for drugs by therapeutic class. Countries may differ substantially in the approval and coverage decisions for anticancer drugs.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the approval and coverage decisions for new anticancer drugs between the United States and 4 other countries: the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and Canada.

METHODS:

We identified all new anticancer drug indications approved by the FDA between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. For each country, we reviewed the organizations, processes, criteria, and special considerations used to make approval and coverage decisions for the drug indications approved. We further quantified and compared the variations across the 5 countries in the approval and coverage decisions as of June 30, 2014, for new anticancer drug indications.

RESULTS:

Of 45 anticancer drug indications approved in the United States between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, 67% (30) were approved by the European Medicines Agency, and 53% (24) were approved in Canada and Australia before December 31, 2013. The U.S. Medicare program covered all 45 drug indications, and as of June 30, 2014, the United Kingdom covered 87% (26) of those approved in Europe—58% (26) of the drug indications covered by Medicare. France, Canada, and Australia covered 42% (19), 29% (13), and 24% (11) of the drug indications covered by Medicare, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

Approval and reimbursement decisions vary substantially by country. The United States had the fewest access restrictions, and Australia was the most restrictive of the 5 countries that were examined.

What is already known about this subject

Previous studies have shown that 42% of anticancer drugs approved in the United States from 2004 to 2008 were approved in the United Kingdom, and 35% of anticancer drugs approved in the United States from 2000 to 2009 were approved in Australia.

The U.S. Medicare program covers anticancer drugs through its Part B and Part D components: Oncologic drugs that need to be administrated by physicians are generally covered by Part B with a fixed 20% coinsurance, and oral anticancer drugs are covered under Medicare Part D with varying coinsurance depending on plan formularies and benefit structures.

Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom use cost-effectiveness analyses explicitly, and France considers costs implicitly in its coverage decisions.

What this study adds

This study updates the previous country comparisons to cover the years 2009-2013 and expands the comparisons to France and Canada.

Among the 5 countries reviewed, the United States had the fewest access restrictions, and Australia had the most restrictions.

Countries using cost-effectiveness analyses explicitly are more restrictive in their coverage decisions.

Cancer is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2012 alone, there were 14 million new cancer cases worldwide, 8.2 million cancer-related deaths, and 32.6 million people living with cancer.1 Cancer treatment is costly. Anticancer drugs are estimated to account for 12% of total direct cancer care costs and 5% of total drug costs worldwide.2 In 2014, global pharmaceutical sales for anticancer drugs were $74.4 billion, ranking first in global sales for drugs by therapeutic class.3

Scientific understanding of cancer is growing rapidly and has led to a surge in new development of anticancer drugs. Approval and reimbursement decisions may vary substantially by country. Many national health care systems use strategies to rationally allocate scarce health care resources.4 For instance, the United Kingdom bases its coverage decisions on health technology assessments that include a cost-effectiveness analysis, that is, a drug is covered if it is below a prespecified cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). However, restricting access to anticancer drugs is highly controversial because of the lack of therapeutic alternatives for some types of cancer.

In this study, we compared the approval and coverage decisions for new anticancer drugs between the United States and 4 other countries: the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and Canada. These 4 countries were chosen because, compared with the United States, they accomplish better health outcomes—commonly measured by life expectancy, infant mortality, and percentage of population with multiple chronic conditions—with less than or about half of the total health care expenditures per capita in the United States.5 All 5 countries rely on a market economy and share similar political systems. France, the United Kingdom, and Australia often rank at the top based on measures such as efficiency and equity, but each has its unique way for allocating health care resources.5,6 Canada was also chosen for its geographic proximity to the United States. We reviewed the organizations, processes, criteria, and special considerations used by these countries to make approval and coverage decisions for new anticancer drug indications that were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. We further quantified and compared the variations across the 5 countries of the approval and coverage decisions for these new anticancer drug indications before June 30, 2014.

An Overview of the International Comparison of Anticancer Drug Approval and Coverage

United States.

In the United States, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research evaluates the safety and efficacy of new medications and makes decisions about whether a new drug should enter the U.S. market on the basis of safety, quality, and efficacy.7 Cost is not a criterion used for approving a new drug. For anticancer drugs, the FDA Office of Hematology and Oncology Drug Products facilitates the rapid review of promising new cancer therapies.

Once a new drug is approved by the FDA, public and private insurance programs separately evaluate the coverage decisions for their own covered patients. There are 3 main publicly funded insurance programs: Medicare covers the elderly and disabled; Medicaid covers the poor; and the Department of Veterans Affairs covers veterans. Medicare covers anticancer drugs through its Part B and Part D programs. Oncologic drugs that need to be administrated by physicians are generally covered by Part B, with a fixed 20% coinsurance after a deductible, and the law requires Medicare Part B to cover any drug used in an “anticancer chemotherapeutic regimen,” as long as the use is “for a medically accepted indication,” which includes off-label use—an indication not approved by the FDA but accepted by physicians as medically beneficial treatment.8 Oral anticancer drugs, which patients can obtain from a pharmacy, are covered under Medicare Part D, with varying coinsurance depending on plan formularies and benefit structures. For veterans, anticancer drugs are covered, as long as the drug is used for an approved indication. For individuals with commercial insurance covering prescription drugs, each insurance plan maintains a formulary, which is a list that indicates what prescription drugs are covered by the plan and the rate of copayments or coinsurance for the drugs.

United Kingdom.

During the study period, the United Kingdom was a member of the European Union, where the European Medicines Agency (EMA) appraises the safety and efficacy of new medications and supervises their entrance to and duration on the market in the European Union. The EMA applies its centralized procedure to determine which medications are approved to enter the market in all European Union member countries.

For the United Kingdom specifically, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) assesses the technologies referred by the U.K. Department of Health and issues coverage recommendations to the U.K. National Health Service (NHS).11 NICE recommendations are based on drug efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. NICE cost-effectiveness coverage threshold for cancer drugs is £50,000 (U.S. $74,500) per QALY, which is £12,000 (U.S. $17,880) per QALY higher than for the rest of the drug classes set at £38,000 (U.S. $56,620) per QALY.12 In addition, the Cancer Drugs Fund provides £200 million (U.S. $298 million) each year to cover anticancer drugs not covered by the NHS, and some pharmaceutical companies have negotiated patient access schemes with the NHS for drugs not recommended by NICE.13 These risk-sharing contracts allow patients to have access to some drugs not covered otherwise.14 Almost half of the drugs with currently approved patient access schemes are anticancer drugs.15

France.

After a drug is approved by the EMA to enter the European market, the French Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products must approve all medications for use in France.16

The Transparency Committee of the High Authority of Health recommends the coverage of new drugs on the market in France. The committee appraises the severity of the drug’s cancer indication; its effectiveness; its safety profile; whether it is intended to prevent, cure, or relieve symptoms; and how it compares to other drugs on the market.17 The National Union of Health Insurance Funds uses the determinations of the Transparency Committee, as well as the severity of the indication, to define the rate of permissible reimbursement benefits and fixed rate support care for the drug. Orphan drugs seen as irreplaceable and lifesaving receive 100% reimbursement, and this applies to many of the available cancer drugs on the List of Long-Term Afflictions.18

Australia.

The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration approves new drugs to enter the Australian market. The approval decision is based on the efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of a drug.19,20

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee is responsible for the coverage decisions in Australia after a drug is approved.21 A coverage decision is based on the efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of the drug as compared with other treatments currently covered for the same indication. There is no stated cost-effectiveness threshold, but the regularly implied level is AUD $50,000 (U.S. $39,000) per QALY.22 The only exception to this pathway for coverage is for orphan drugs, whose coverage is usually rejected by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee based on cost-effectiveness and is reconsidered under the Life Saving Drugs Program. Under this program, orphan drugs for rare and life-threatening forms of cancer are covered for eligible patients.

Canada.

Health Canada’s drug review process begins with its Therapeutic Products Directorate, a board of scientists that assesses the quality, safety, and efficacy of a drug and decides whether the benefits outweigh the risks of allowing the drug to enter and continue to be on the market.23

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health runs a Common Drug Review to rate the clinical and cost effectiveness of drugs for the purpose of recommending drugs to be covered by the provinces, but each province can make its own decision.24 The pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review evaluates oncology drugs based on clinical evidence and cost-effectiveness, recommends funding decisions, and includes suggested dosage and place in therapy.25 Then, the provinces make their respective coverage decisions independently on the basis of the information provided by the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review.

Methods

Identification of FDA-Approved New Oncology Drugs

We identified new drugs approved by the FDA for the treatment of any cancer between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, using the FDA (http://www.fda.gov/) and CenterWatch (http://www.centerwatch.com/) websites (Table 1). Previous researchers have shown that new drugs are approved more quickly in the United States, compared with European countries, so using the list of new drugs approved by the FDA provided the most updated list of new drugs.26,27 Our sample included active ingredients approved for new cancer indications between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. Pharmaceutical agents used to treat any chemotherapy-induced side effects or cancer-related pains were excluded. The final list included 41 unique drugs that were approved for 45 drug indications related to cancer. We also stratified the analyses by each drug’s route of administration: oral or injectable.

TABLE 1.

List of New Oncology Drugs Approved by the FDA, January 1, 2009-December 31, 2013

| Brand Name | Active Ingredient | Indication | Route of Administration | Approval Dates | Coverage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | EMA | Canada | Australia | United Kingdom | France | Canada | Australia | ||||

| Abraxane | Paclitaxel protein-bound particles | Non-small cell lung cancer | Injectable | October 2012 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Adcetris | Brentuximab vedotin | Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma | Injectable | August 2011 | October 2012 | February 2013 | December 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Afinitor | Everolimus | Renal cell carcinoma | Oral | March 2009 | August 2009 | Not Approved | August 2009 | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Afinitor | Everolimus | Advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | Oral | May 2011 | September 2011 | August 2011 | July 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Afinitor | Everolimus | Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer | Oral | July 2012 | July 2012 | January 2013 | February 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arzerra | Ofatumumab | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Injectable | October 2009 | April 2010 | August 2012 | Not Approved | Yes | No | No | NA |

| Avastin | Bevacizumab | Renal cell carcinoma | Injectable | July 2009 | January 2008 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Yes | No | NA | NA |

| Bosulif | Bosutinib | Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia | Oral | September 2012 | March 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Ye s | Ye s | NA | NA |

| Cometriq | Cabozantinib | Metastatic medullary thyroid cancer | Oral | November 2012 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Erivedge | Vismodegib | Basal cell carcinoma | Oral | January 2012 | July 2013 | August 2013 | May 2013 | Ye s | Ye s | Ye s | No |

| Erwinaze | Asparaginase Erwinia chrysanthemi | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Injectable | November 2011 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Folotyn | Pralatrexate | Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | Injectable | September 2009 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gazyva | Obinutuzumab | Previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Injectable | October 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gilotrif | Afatinib | Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR mutations | Oral | July 2013 | September 2013 | Not Approved | November 2013 | No | Ye s | NA | No |

| Halaven | Eribulin mesylate | Metastatic breast cancer | Injectable | November 2010 | March 2011 | March 2012 | August 2012 | Ye s | Ye s | Ye s | No |

| He re eptin | Trastuzumab | Gastric cancer | Injectable | October 2010 | January 2010 | August 2010 | September 2010 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Iclusig | Ponatinib | Chronic myeloid leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Oral | December 2012 | July 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Yes | No | NA | NA |

| Imbruvica | Ibrutinib | Mantle cell lymphoma | Oral | November 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Inlyta | Axitinib | Advanced renal cell carcinoma | Oral | January 2012 | September 2012 | August 2012 | July 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Istodax | Romidepsin | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | Injectable | November 2009 | Not Approved | Not Approved | August 2013 | NA | NA | NA | No |

| Jevtana | Cabazitaxel | Prostate cancer | Injectable | June 2010 | March 2011 | August 2011 | December 2011 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Kadcyla | Ado-trastuzumab | HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer | Injectable | February 2013 | November 2013 | October 2013 | September 2013 | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Kyprolis | Carfilzomib | Multiple myeloma | Injectable | July 2012 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Marchqibo | Vincristine | Ph-acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Injectable | August 2012 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mekinist | Trametinib | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations | Oral | May 2013 | Not Approved | August 2013 | Not Approved | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Perjeta | Pertuzumab | HER2+ metastatic breast cancer | Injectable | June 2012 | March 2013 | May 2013 | May 2013 | Ye s | Ye s | Ye s | No |

| Pomalyst | Pomalidomide | Relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma | Oral | February 2013 | August 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Ye s | No | NA | NA |

| Provenge | Sipuleucel-T | Hormone refractory prostate cancer | Injectable | May 2010 | September 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | No | No | NA | NA |

| Revlimid | Lenalidomide | Mantle cell lymphoma | Oral | June 2013 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Stivarga | Regorafenib | Metastatic colorectal cancer | Oral | September 2012 | September 2013 | April 2013 | November 2013 | Ye s | No | No | No |

| Stivarga | Regorafenib | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | Oral | February 2013 | Not Approved | April 2013 | Not Approved | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Sutent | Sunitinib | Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | Oral | May 2011 | December 2010 | Not Approved | March 2011 | Ye s | Ye s | NA | Yes |

| Sylatron | Peginterferon alfa-2b | Melanoma | Injectable | April 2011 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Synribo | Omacetaxine | Chronic or accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia | Injectable | October 2012 | Not Approved | Not Approved | Not Approved | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tafinlar | Dabrafenib | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation | Oral | May 2013 | September 2013 | August 2013 | August 2013 | No | No | No | Yes |

| Vandetanib | Vandetanib | Thyroid cancer | Oral | April 2011 | February 2012 | February 2012 | January 2013 | Ye s | Ye s | No | No |

| Votrient | Pazopanib | Renal cell carcinoma | Oral | October 2009 | June 2010 | August 2010 | June 2010 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Votrient | Pazopanib | Soft tissue sarcoma | Oral | April 2012 | August 2012 | August 2010 | May 2011 | Ye s | No | No | Yes |

| Xalkori | Crizotinib | ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer | Oral | August 2011 | October 2012 | May 2012 | September 2013 | Ye s | Ye s | No | No |

| Xgeva | Denosumab | Giant cell tumor of bone | Injectable | June 2013 | Not Approved | June 2011 | Not Approved | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Xtandi | Enzalutamide | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Oral | August 2012 | June 2013 | June 2013 | Not Approved | Yes | No | Yes | NA |

| Yervoy | Ipilimumab | Metastatic melanoma | Injectable | March 2011 | July 2011 | March 2012 | June 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Zaltrap | Ziv-aflibercept | Metastatic colorectal cancer | Injectable | August 2012 | February 2013 | Not Approved | April 2013 | Yes | Yes | NA | No |

| Zelboraf | Vemurafenib | BRAFm+ melanoma | Oral | August 2011 | February 2012 | March 2012 | May 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Zytiga | Abiraterone | Prostate cancer | Oral | May 2011 | September 2011 | July 2011 | March 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Sources: The FDA and CenterWatch websites were used to identify drugs approved by the FDA for the treatment of any cancer between the dates shown above (http://www.fda.gov/; http://www.centerwatch.com/).

Notes: The date December 31, 2013, was used as the end point for approval decisions, and June 30, 2014, was used as the end point for coverage decisions in non-U.S. countries. NA denotes not applicable because these drugs were not approved in other countries, so they were not covered.

EMA = European Medicines Agency; FDA =U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Identification of Approval Data for New Anticancer Drugs

The following websites were checked to obtain approval dates between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013: EMA (http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/) for the United Kingdom and France; the French Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products for France (http://agence-prd.ansm.sante. fr/php/ecodex/index.php); the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (http://www.tga.gov.au/) for Australia; and the Drug Product Database on the Health Canada website (http://webprod5.hc-sc.gc.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.jsp) for Canada.

Identification of Coverage Decision Data of New Anticancer Drugs

Between March and June 2014, we checked the following websites to collect coverage information for all approved drug indications in each country. We reviewed the British National Formulary websites to identify whether approved drugs were covered by the NHS.28 For drug coverage in France, we reviewed the Public Database of Medications and the Technical Agency for Hospital Information (Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation).29,30 We searched the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee’s website to determine whether a drug was covered in Australia.31 The pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review database was used to identify coverage data for the drugs approved in Canada.32 Because all the study drugs were approved and covered by Medicare in the United States, we used Medicare as a benchmark to compare with the other countries. We calculated the percentages of approved U.S. drugs that were approved, approved and covered, and approved but not covered in other countries. If a drug was approved before December 31, 2013, in other countries, it was defined as approved; if a drug was covered at the time of collecting these data, it was defined as covered.

Results

Before December 31, 2013, 67% (30) of those 45 drug indications were approved by the EMA and therefore available (but possibly not covered) in the United Kingdom, and France approved all 30 EMA-approved drug indications. In Canada and Australia, 53% (24) of the drug indications were approved.

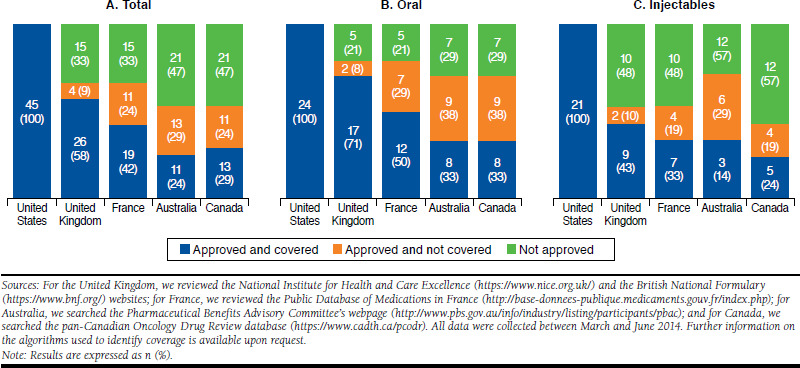

All these drug indications were covered by Medicare, with 23 covered in Medicare Part B and 22 covered in Medicare Part D. Figure 1 summarizes the percentage of drugs covered by Medicare that were approved and covered by other countries as of June 30, 2014, showing the total as well as stratifying by route of administration. The NHS covered 87% (26) of the 30 drugs approved in the United Kingdom, or 58% (26) of the 45 drug indications covered by Medicare. France covered 63% of the 30 drug indications approved in France, equivalent to 42% (19) of what Medicare covered, followed by Canada with 29% (13) and Australia with 24% (11) of what Medicare covered.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of Approval and Coverage Decisions in Other Countries as Percentages of Drugs That Were Approved in the United States and Covered by Medicare, by Route of Drug Administration

After stratifying by route of administration, we found that the coverage of oral anticancer drugs is less restrictive than the coverage of injections in all non-U.S. countries. Specifically, the United Kingdom covered 71% (17) of all oral anticancer drug-indications in our list, but only 43% (9) of the injectable anticancer drug-indications”

Discussion

We compared the approval and coverage decisions in 5 developed countries for 45 new cancer drug indications that were approved by the FDA between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. Medicare covered all 45 drug indications approved. The list of 5 countries in order from the most restrictive to the least restrictive is Australia, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Mason et al. (2010) compared the coverage decisions in the United States and the United Kingdom for 46 anticancer drugs approved by the FDA from 2004 through 2008.10 In our study, we updated the list of anticancer drugs approved between 2009 and 2013 and found that the proportion of covered medications increased from 42% as reported by Mason et al. to 58%. Wilson et al. (2011) compared the cancer drug coverage decisions of the United States and Australia for 34 drugs approved by the FDA between 2000 and 2009, and they found that 35% of the drugs approved by the FDA were approved and covered in Australia.33 During our study period, we found that the proportion of covered medications decreased from 35% to 24%.

Of the 5 countries we reviewed, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom used cost-effectiveness analyses explicitly in their coverage decisions. France considered cost implicitly and did not compare health gains against an explicit and rigid cost-effectiveness threshold. Use of cost-effectiveness in coverage decisions was relatively limited in the United States, as compared with the other 4 countries. Medicare has used cost-effectiveness analysis to inform its coverage decisions for preventive care services, but it does not and is unlikely that it will use explicit and rigid cost-effectiveness thresholds in coverage decisions for treatments, as in the United Kingdom.34 Nevertheless, allowing the flexible use of cost-effectiveness analysis to guide some reimbursement policies may be beneficial, especially for conditions with multiple treatment options and existing rigorous comparative effectiveness evidence. For example, there can be flexibilities in different thresholds for different subgroups, different conditions, how well patients respond to the treatment, and patient life expectancy.35 In fact, under the U.S. Affordable Care Act, the payment and integrated delivery models incentivize high-value cancer care, ranging from preventive screening, to value-based treatment, and to palliative care to end-of-life patients. For example, in the Medicare program, accountable care organization providers have incentives to use low-cost and high-value oncology care to manage their patients’ health.36

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, the results on the comparative coverage of anticancer drugs in 5 countries are not generalizable to other therapeutic classes. Coverage of anticancer drugs is likely to differ from other therapeutic classes because cancer is often a life-threatening illness. Second, we did not evaluate when manufacturers actually submitted the approval requests to the approval agencies of the different countries. If manufacturers did not submit to the EMA during the study period, we would not have been able to observe those approval dates. However, previous researchers have shown that manufacturers often submitted to the FDA and the EMA around the same time and submitted to Australian and Canadian agencies within 3 months after submission to the FDA.37 Third, we only reported whether a drug was covered in a specific country during our study period and did not report actual coverage dates because countries do not routinely report these dates. Finally, we did not compare cancer outcomes across countries.

Conclusions

Of 45 anticancer drug indications approved in the United States between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, 67% (30) were approved by the EMA, and 53% (24) were approved in Canada and Australia before December 31, 2013. As of June 30, 2014, in the United States, Medicare covered all 45 drug indications, while the United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Australia covered 58% (26), 42% (19), 29% (13), and 24% (11) of that number, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andre Lebrun for his excellent research assistance in collecting information on the approval and coverage of oncologics in Australia.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Cancer. Fact sheet. Updated February 2015. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 2.Khayat D. Innovative cancer therapies: putting costs into context. Cancer. 2012;118(9):2367-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statista . Top 20 therapeutic classes by global pharmaceutical sales in 2015 (in billion U.S. dollars). Available at: http://www.statista.com/statistics/279916/top-10-therapeutic-classes-by-global-pharmaceutical-sales/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 4.Roberts SA, Allen JD, Sigal EV. Despite criticism of the FDA review process, new cancer drugs reach patients sooner in the United States than in Europe. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(7):1375-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Commonwealth Fund . Mirror, mirror on the wall, 2014 update: how the U.S. health care system compares internationally. June 16, 2014. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 6.World Health Organization . The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . How drugs are developed and approved. Updated August 18, 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 8.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patients Equal Access Coalition . Oral chemotherapy access legislative map. 2016. Available at: http://peac.myeloma.org/oral-chemo-access-map/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 10.Mason A, Drummond M, Ramsey S, Campbell J, Raisch D. Comparison of anticancer drug coverage decisions in the United States and United Kingdom: does the evidence support the rhetoric? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(20):3234-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raftery J. Review of NICE’s recommendations, 1999-2005. Br Med J. 2006;332(7552):1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson B. Technology assessment for new oncology drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(1):6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health . The pharmaceutical price regulation scheme 2014. December 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/282523/Pharmaceutical_ Price_Regulation.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 14.Williamson S. Patient access schemes for high-cost cancer medicines. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):111-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . List of technologies with approved Patient Access Schemes. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice. org.uk/about/what-we-do/patient-access-schemes-liaison-unit/list-of-technologies-with-approved-patient-access-schemes. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 16.L’agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé . Conseil Scientifique. 2015. Available at: http://ansm.sante.fr/L-ANSM2/Gouvernance/Conseil-scientifique/(offset)/2. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 17.Haute Autorité de Santé . Reglement Interieure de la Commission de la Transparence (Rules of the Interior Committee). Updated April 6, 2016. Available at: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-01/ri_ct_version_07112012_vf_f.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 18.Santé-Médecine . Liste des affections de longue durée (ALD). 2014. Available at: http://sante-medecine.commentcamarche.net/faq/477-liste-des-affections-de-longue-duree-ald. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 19.Therapeutic Goods Administration . TGA basics. 2014. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/about/tga.htm#.UzHVmj45NJU. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 20.Therapeutic Goods Administration . About the work of the TGA - a risk management approach. August 15, 2011. Available at: http://www.tga.gov. au/about/tga-risk-management-approach.htm#.UzHWez45NJU. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 21.Simon SR, Rodriguez HP, Majumdar SR, et al. Economic analysis of a randomized trial of academic detailing interventions to improve use of anti-hypertensive medications. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9(1):15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics . Impact of cost-per-QALY reimbursement criteria on access to cancer drugs. December 2014. Available at: https://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Healthcare%20 Briefs/IHII_CPQ_Impact_on_Access_to_Cancer_Drugs.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 23.Morgan S, Mintzes B, Barer M. The economics of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription-only drugs: prescribed to improve consumer welfare? J Health Sev Res Policy. 2003;8(4):237-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health . CADTH Common Drug Review. 2014. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/about-cadth/what-we-do/products-services/cdr. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 25.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health . CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR). 2011. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/pcodr. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 26.>Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Braunstein JB, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Regulatory review of novel therapeutics — comparison of three regulatory agencies. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2284-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts SA, Allen JD, Sigal EV. Despite criticism of the FDA review process, new cancer drugs reach patients sooner in the United States than in Europe. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(7):1375-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.British National Formulary . Website. 2014. Available at: https://www. bnf.org/. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 29.Ministère des Affaires sociales et de la Santé . Base de données publique des médicaments. 2014. Available at: http://base-donnees-publique.medicaments.gouv.fr/index.php. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 30.Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation (Technical Agency for Hospital Information) . Liste des unités communes de dispensation prises en charge en sus. 2015. Available at: http://www.atih.sante. fr/liste-des-unites-communes-de-dispensation-prises-en-charge-en-sus. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 31.Australian Department of Health . Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. 2014. Available at: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 32.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health . CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review. 2014. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/pcodr. Accessed January 5, 2017.

- 33.Wilson A, Cohen J. Patient access to new cancer drugs in the United States and Australia. Value Health. 2011;14(6):944-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann PJ, Rosen AB, Weinstein MC. Medicare and cost-effectiveness analysis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1516-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness— the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta AJ, Macklis RM. Overview of accountable care organizations for oncology specialists. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):216-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science . The impact of the changing regulatory environment on the approval of new medicines across six major authorities 2004-2013. December 16, 2014. Available at: http://cirsci. org/sites/default/files/R&D%20Briefing%2055%2016122014.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.