Abstract

Background and purpose

We examined functional outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy (MT) procedures following anterior circulation large vessel occlusion (ACLVO)-related acute ischemic strokes (AIS). Results were based on admission non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) studies, using the Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS) as standard metric.

Methods

Qualifying subjects were consecutive patients (N = 343) at a single center undergoing MT for ACLVO-related AIS. Each was grouped according to ASPECTS status on admission, determined from NCCT images by two physicians. Primary clinical endpoint was functional independence, assessed via modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 90 days. Secondary endpoints were vessel recanalization (i.e., modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction [mTICI] score), symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), and mortality.

Results

In this study population (mean age, 63.6 ± 12.6 years; women, 30.3%; median baseline National Institute of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score, 15.2 ± 4.5), patients were stratified by ASPECTS tier at presentation, either 0–5 (n = 50) or 6–10 (n = 293). Multivariate logistic regression showed a relation between ASPECTS values ≤ 5 and lesser chance of 90-day functional improvement (OR = 2.309, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.012–5.271; p = 0.047), once adjusted for age, baseline NIHSS score, diabetes mellitus, HbA1c concentration, D-dimer level, occlusive location, numbers of device passes, and successful recanalization.

Conclusions

ASPECTS values ≤ 5 correspond with worse long-term functional improvement (mRS scores > 2) in patients undergoing MT for ACLVO-related AIS. Other independent determinants of functional outcomes after MT are age, baseline NIHSS score, HbA1c concentration, and successful recanalization.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-023-01225-0.

Keywords: Mechanical thrombectomy, Stroke imaging, Acute ischemic stroke, CT, Outcomes

Introduction

Domestic and foreign studies have validated the Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS) as a standardized quantitative metric, reflecting the extent of infarction in instances of acute anterior circulation large vessel occlusion (ACLVO) [1, 2]. Recent reports have also demonstrated that this simple and reliable measure may serve to identify the most suitable patients for endovascular therapy and function as a prognostic index [3]. According to American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines, the standard of care in adult patients with ASPECTS values ≥ 6 and large-vessel occlusion is endovascular therapy [4, 5]. However, much of the research on mechanical thrombectomy (MT) has excluded patients with lower ASPECTS values (≤ 6 or 7), failing to fully address the prognostic utility of ASPECTS in MT-treated patients [6, 7]. Only a few of patients with low ASPECTS accepted MT; therefore, data about their clinical outcomes remain scarce. In addition, whether MT is beneficial in AIS patients with low ASPECTS remains uncertain. Hence, in the present study, we compared ASPECTS values of NCCT studies on admission with clinical consequences of MT (including successful recanalization, functional improvement, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [sICH], and mortality), hoping to facilitate the planning of MT procedures.

Methods

Patient selection

This was a single-center retrospective observational analysis of 343 consecutive patients with ACLVO-related AIS treated by MT between January 2016 and December 2022. The hospital's institutional review board approved our study protocol.

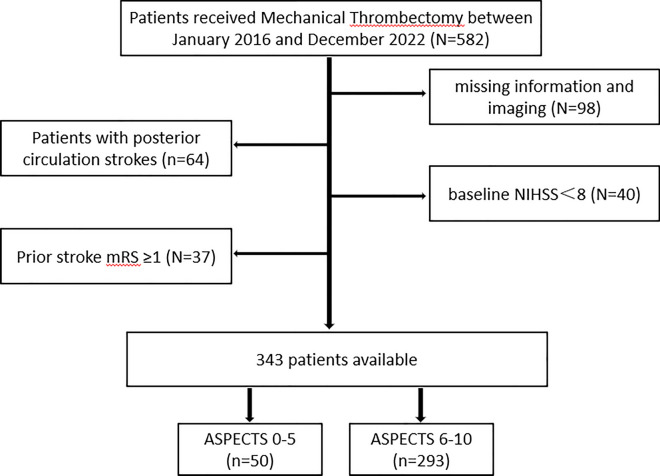

Eligible MT-treated subjects met the following inclusion criteria: (1) adult ≥ 18 years; (2) availability of non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) imaging done on admission; and (3) proximal anterior circulation occlusion involving internal carotid artery (ICA) or M1/proximal M2 branch of middle cerebral artery (MCA), as shown by computed tomography angiography (CTA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). The following were grounds for study exclusion: (1) prior severe stroke, with baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≤ 8 or baseline modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score ≥ 1; (2) hemorrhagic infarction on baseline CT; (3) other brain abnormalities, such as tumors or trauma (shown in Fig. 1); or (4) participants with incomplete data.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of patient selection

Data collection

We retrieved baseline patient characteristics (age and sex), medical history (including prior stroke, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation/flutter, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes mellitus), and lifestyle habits (current/prior tobacco use, alcohol intake), as well as clinical parameters on admission (ie, NIHSS score, diastolic [DBP] and systolic [SBP] blood pressure readings, glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1c] concentration, D-dimer level, and presence of hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign [HMCAS] or signs of early infarction on NCCT) and intravenous injection of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) from electronic medical records. Other clinical variables, including trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment (TOAST) classification, occlusive location, stroke-onset to puncture time, number of device passes, and use of balloon-guided catheter or angioplasty/stenting, were also recorded.

All NCCT studies were performed by Discovery CT 750 HD scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) at the following settings: tube voltage, 100 kV; tube current, 120 mA; collimator width, 40 mm; field of view, 25 cm; layer thickness, 5 mm; layer spacing, 5 mm. Two neuroradiologists blinded to clinical outcomes separately determined ASPECTS values for each patient. Inconsistencies were resolved by imaging reviews, reaching consensus decisions through discussion.

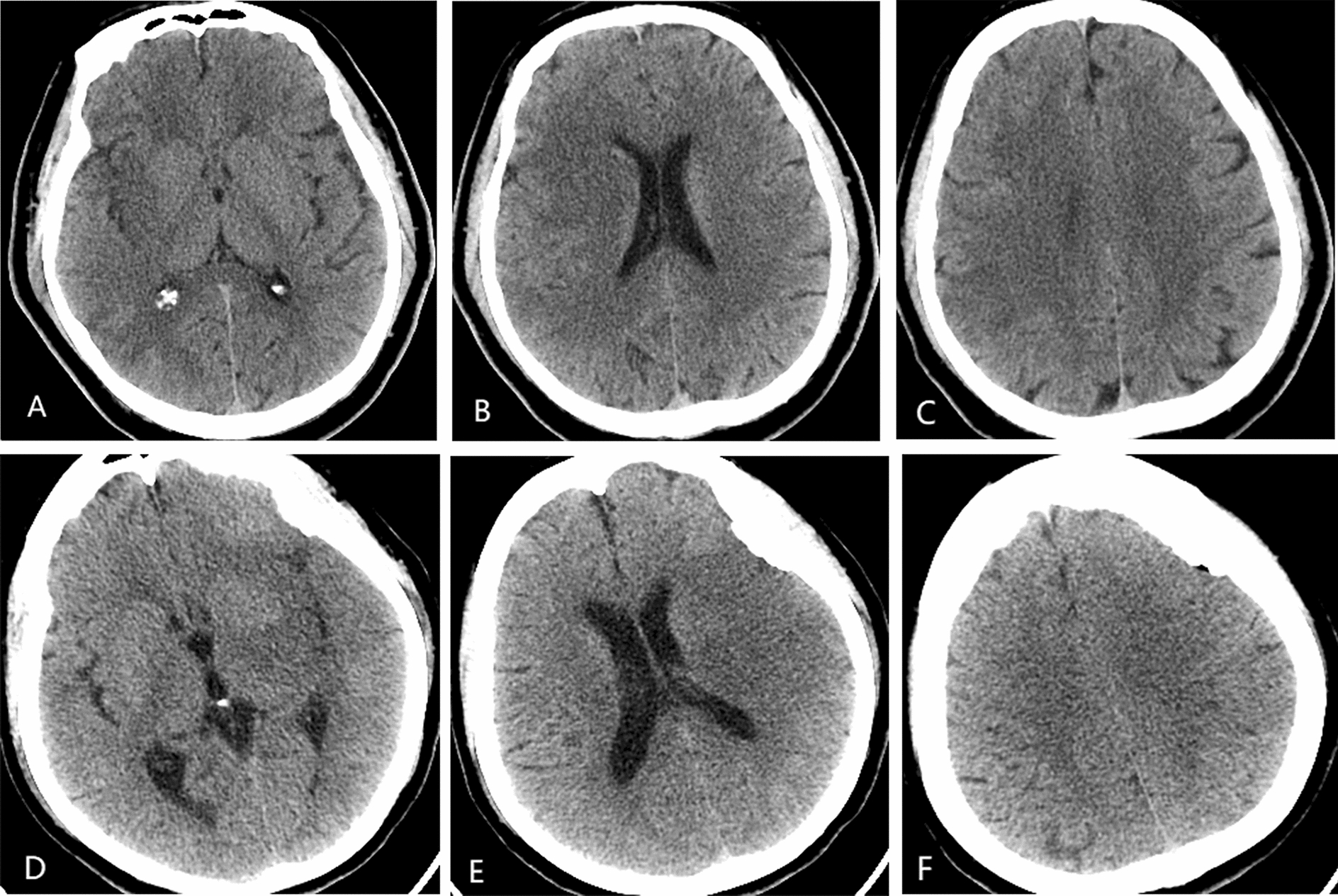

In ASPECTS determinations, MCA vascular supply has 10 defined territories [1], including seven regions of caudate nucleus and layers below (M1, M2, M3, insula [I], lenticular nucleus[L], caudate nucleus [C], and posterior limb of internal capsule [IC]) and three areas of cerebral cortex above the nucleus(M4, M5, and M6). Maximum score is 10 points, subtracting 1 point for each injured area (shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representative images of patients in ASPECTS tiers: A–C 56-year-old man with baseline ASPECTS of 6 (M1, M2, L, M6); baseline NIHSS score, 11; HbA1c, 9.22; mTICI score, 2b; and mRS score, 2. D–F 77-year-old woman with baseline ASPECTS of 4(M2, I, L, IC, M5, M6); baseline NIHSS score, 20; HbA1c, 5.38; mTICI score, 2b; and mRS score, 3. Middle cerebral artery (MCA), insula (I), lenticular nucleus (L), caudate nucleus (C), posterior limb of internal capsule (IC)

Clinical outcomes

The primary study endpoint was long-term functional independence, measured by mRS at 90 days. Outpatient follow-up or phone calls were used to assess patients functional independence by neurologists. Secondary endpoints were successful vascular reperfusion immediately following MT (ie, modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction [mTICI] score of 2b or 3)[8]; symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), indicated by ≥ 4-point decline in NIHSS score or CT evidence of hemorrhage within 24 h post-MT; and mortality [9].

Statistical analysis

All computations were driven by standard software (SPSS v22.6; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to determine normality of distributions. Continuous variables with non-normal distributions were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) values. Normally distributed continuous variables were subjected to Student’s t test, assesssing non-normal variables by Mann–Whitney U test and categorical variables by Fisher’s exact or χ2 test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis served to identify independent predictors of clinical outcomes. Results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), setting significance at p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

The 343 qualifying patients were grouped according to ASPECTS tier (0–5, 50; 6–10, 293). Mean age was 63.6 ± 12.6 years, and 96 (30.3%) were women. A summary of group parameters is provided in Table 1. Members of the low-scoring (0–5) group exhibited more extreme presentations than did high-scoring (6–10) group members (mean baseline NIHSS score: 18.1 ± 5.1 vs 14.6 ± 4.3; p < 0.001). Likewise, HMCAS positivity (78.0% vs 58.7%; p = 0.010) and signs of early infarction (90.0% vs 58.0%; p < 0.001) were significantly more prevalent in the low-scoring (vs high-scoring) group (Table 1; Additional file 1: Table S1)

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics, overall and by ASPECTS determinations

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 343) | ASPECTS0–5 (n = 50) | ASPECTS 6–10 (n = 293) | P value | |

| Age, y | 63.6 ± 12.6 | 61.1 ± 11.0 | 64.1 ± 12.8 | 0.058 |

| Female | 104(30.3) | 9(18) | 95(32.4) | 0.044a |

| Hypertension | 198(57.7) | 30(60) | 168(57.3) | 0.725 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 90(26.2) | 11(22) | 79(27) | 0.410 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 104(30.3) | 20(40) | 84(28.7) | 0.107 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 133(38.3) | 20(40) | 113(38.6) | 0.848 |

| Coronary artery disease | 67(19.5) | 8(16) | 59(20.1) | 0.495 |

| Current/prior tobacco use | 162(47.2) | 27(54) | 135(46.1) | 0.300 |

| Current/prior alcohol intake | 167(48.7) | 26(52) | 141(48.1) | 0.612 |

| TOAST classification | 0.678 | |||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 256(74.6) | 36(72) | 220(75.1) | |

| Cardioembolism | 79(23) | 12(24) | 67(22.9) | |

| Other determined etiology | 8(2.3) | 2(4) | 6(2) | |

| Prestroke | 77(22.4) | 11(22) | 66(22.5) | 0.934 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 15.2 ± 4.5 | 18.1 ± 5.1 | 14.6 ± 4.3 | < 0.001a |

| HMCAS | 211(61.5) | 39(78) | 172(58) | 0.010a |

| Signs of early infarction | 215(62.7) | 45(90) | 170(58) | < 0.001a |

| DBP on admission, mmHg | 82.8 ± 15.1 | 82.4 ± 14.6 | 82.9 ± 15.2 | 0.999 |

| SBP on admission, mmHg | 140.5 ± 25.1 | 135.1 ± 27.2 | 141.4 ± 24.5 | 0.052 |

| HbA1c, mmol/L | 6.3(5.7–8.0) | 6.7(5.7–8.0) | 6.3(5.7–8.0) | 0.354 |

| D-dimer, mmol/L | 1.3(0.7–3.1) | 1.7(0.9–3.8) | 1.3(0.7–2.9) | 0.192 |

| Occlusive location | 0.378 | |||

| ICA | 91(26.5) | 17(34) | 74(25.3) | |

| MCA M1 | 150(43.7) | 21(42) | 129(44) | |

| MCA M2 | 22(6.4) | 1(2) | 21(7.2) | |

| ICA + MCA | 80(23.3) | 11(22) | 69(23.5) | |

| IV tPA | 82(23.9) | 7(14) | 75(25.6) | 0.760 |

| Oneset to puncture, min | 412.0(233.5–609.0) | 422.5(280.7–545.5) | 410.0(227.0–615.0) | 0.918 |

| Device passes | 1.5(1–2) | 1.5(1–2) | 1.5(1–2) | 0.255 |

| Balloon-guided catheter | 80(23.3) | 10(20) | 70(23.9) | 0.548 |

| Angioplasty and stenting | 26(7.6) | 4(8) | 22(7.5) | 0.903 |

Significant values in bold

Data expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard devation values

aASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, TOAST Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, HMCAS hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign, DBP diastolic blood pressure, SBP systolic blood pressure, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery, IV tPA intravenous tissue plasminogen activator

Clinical outcomes

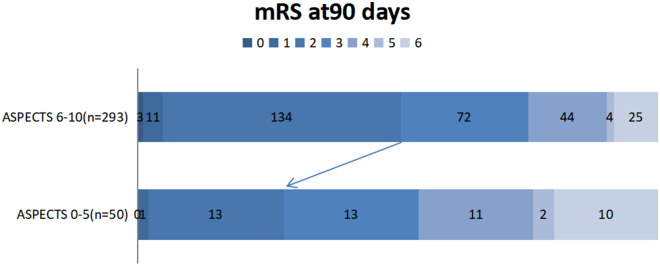

Clinical outcomes are shown by groups in Table 2. Unlike the high (6–10) ASPECTS tier, low-tier (0–5) members were less inclined to show good clinical outcomes (mRS scores 0–2) at 90 days (28.0% vs 50.5%; p = 0.038) (shown in Fig. 3), demonstrating higher rates of sICH (44.0% vs 21.8%; p < 0.001) and mortality (20.0% vs 8.5%; p = 0.013). However, successful reperfusion rates did not differ significantly in the two groups (78.0% vs 75.4%; p = 0.0695).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes of patients, overall and by ASPECTS determinations

| Outcomes | Patients, No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 343) | ASPECTS0–5 (n = 50) | ASPECTS 6–10 (n = 293) | ||

| mTICI score | < 0.001a | |||

| 0 | 25(7.3) | 7(14.0) | 18(6.1) | |

| 1 | 25(7.3) | 3(6.0) | 22(7.5) | |

| 2a | 35(10.2) | 2(4.0) | 32(10.9) | |

| 2b | 115(33.5) | 32(64.0) | 84(28.7) | |

| 3 | 143(41.7) | 6(12.0) | 137(46.8) | |

| Successful reperfusion | 259(75.5) | 38(76.0) | 221(75.4) | 0.695 |

| Symptomatic ICH | 86(25.1) | 22(44.0) | 64(21.8) | 0.001a |

| Good functional outcomes (mRS score < 2) at 90 days | 162(47.2) | 14(28.0) | 148(50.5) | 0.003a |

| 90-day mRS score | 3(2–4) | 3(2–4.5) | 3(2–4) | 0.038a |

| Mortality | 35(10.2) | 10(20.0) | 25(8.5) | 0.013a |

Significant values in bold

Data expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard devation values

aASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, mTICI modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction, mRS modified Rankin Scale, ICH intracranial hemorrhage

Fig. 3.

Functional outcomes (modified Rankin Scale [mRS]) at 90 days for two tiers of Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS)

Predictors of worse functional outcomes (mRS scores > 2)

Table 3 contains a listing of unfavorable prognosticators, including older age (p < 0.001), higher baseline NIHSS score (p < 0.001), histories of diabetes mellitus (p < 0.001), increased HbA1c concentration (p < 0.001), elevated D-dimer level (p = 0.006), occlusive location (p = 0.002), number of device passes(p = 0.001), successful reperfusion (p < 0.001), and initial ASPECTS value ≤ 5 (p = 0.017). In multivariate logistic regression, a relation between ASPECTS of ≤ 5 and worse functional outcome (mRS score > 2) at 90 days (OR = 2.309, 95% CI 1.012–5.271; p = 0.047) emerged, once adjusted for age, NIHSS score, diabetes mellitus, HbA1c concentration, D-dimer level, occlusive location, number of device passes, and successful reperfusion (Table 4).

Table 3.

Predictors of poor functional outcome at 90 days (univariate ordinal regression)

| Characteristic | OR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 1.062 | 1.041–1.084 | < 0.001a |

| Female | 1.30 | 0.818–2.067 | 0.267 |

| Hypertension | 1.136 | 0.740–1.745 | 0.559 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.574 | 1.545–4.287 | < 0.001a |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.790 | 0.498–1.252 | 0.315 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1.531 | 0.987–2.373 | 0.057 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.577 | 0.914–2.720 | 0.101 |

| Current/prior tobacco use | 0.715 | 0.467–1.094 | 0.122 |

| Current/prior alcohol intake | 0.669 | 0.437–1.025 | 0.065 |

| TOAST classification | 0.885 | 0.578–1.356 | 0.575 |

| Large artery atherosclerosis | |||

| Cardioembolism | |||

| Other determined etiology | |||

| Prestroke | 1.484 | 0.887–2.483 | 0.133 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 1.143 | 1.082–1.208 | < 0.001a |

| HMCAS | 0.857 | 0.554–1.326 | 0.489 |

| Signs of early infarction | 1.634 | 1.052–2.539 | 0.029* |

| DBP on admission | 0.988 | 0.974–1.002 | 0.090 |

| SBP on admission | 0.997 | 0.988–1.005 | 0.461 |

| HbA1c | 1.486 | 1.279–1.728 | < 0.001a |

| D-dimer | 1.144 | 1.040–1.259 | 0.006a |

| Occlusive location | 0.731 | 0.599–0.892 | 0.002a |

| ICA | |||

| MCA M1 | |||

| MCA M2 | |||

| ICA + MCA | |||

| IV tPA | 1.013 | 0.617–1.665 | 0.958 |

| Oneset to puncture, min | 0.999 | 0.999–1.000 | 0.086 |

| Device passes | 1.539 | 1.186–1.997 | 0.001a |

| Balloon-guided catheter | 0.783 | 0.474–1.292 | 0.338 |

| Angioplasty and stenting | 1.807 | 0.782–4.176 | 0.166 |

| Successful reperfusion | 0.324 | 0.189–0.555 | < 0.001a |

| Symptomatic ICH | 1.782 | 1.080–2.941 | 0.024a |

| ASPECTS ≤ 5 | 2.169 | 1.147–4.100 | 0.017a |

Significant values in bold

aTOAST Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, HMCAS hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign; DBP, diastolic blood pressure, SBP systolic blood pressure, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery, IV tPA intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, ASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model of poor functional independence (mRS score > 2 at 90d)

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASPECTS ≤ 5 | 2.309 | 1.012–5.271 | 0.047a |

| Age | 1.071 | 1.045–1.098 | < 0.001a |

| HbA1c | 1.391 | 1.160–1.669 | < 0.001a |

| Baseline NIHSS | 1.094 | 1.021–1.172 | 0.010a |

| Successful reperfusion | 0.313 | 0.157–0.626 | 0.001a |

Significant values in bold

aASPECTS Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Discussion

Present findings indicate that ASPECTS values ≤ 5 on admission NCCT studies reduce the likelihood of long-term functional independence and increase the odds of sICH and mortality after MT in patients with ACLVO-related AIS. On the other hand, higher ASPECTS values (6–10) herald significantly better clinical outcomes and carry less risk of death. These associations proved significant in multivariate regression analysis, with other independent predictors emerging as well.

ASPECTS is a simple and convenient, topographic method of semiquantitatively gauging early ischemic core infarct volume and is deemed strongly predictive of clinical outcomes in the setting of AIS [1]. Typically, it is a stipulation for enrollment in various randomized intravascular treatment trials. Because past efforts seemed to restrict the merits of MT to patients with ASPECTS values ≥ 6, subsequent clinical trials have tended to exclude those with lesser scores [6, 7, 10]. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of such studies undertaken by Phan et al. to explore ASPECTS as a basis for revascularization suitability has demonstrated the prognostic favorability of a higher (vs lower) ASPECTS status in the course of endovascular thrombectomy [10]. However, more and more efforts are showing that patients with lower ASPECTS values may well benefit from MT under certain conditions [11–14]. In a subgroup analysis of the MR CLEAN randomized phase 3 trial, patients with ASPECTS values of 5–7 were regarded as acceptable candidates for endovascular therapy, otherwise weighing potential treatment benefit and cost-effectiveness of endovascular therapy (in conjunction with various influential factors) at values of 0–4 [3]. An analysis from the STRATIS Registry, conducted by Zaidat et al. and aimed at impacts of age and low (0–5) ASPECTS status (ie, large infarcts) on MT outcomes, has also revealed better clinical outcomes and lower risk of death in patients < 65 (vs > 75) years of age [13].

When comparing our two ASPECTS tiers (0–5 vs 6–10), there was no significant difference in rates of successful recanalization (mTICI scores > 2b). Yet, 90-day functional outcomes in low-scoring patients were better if vessel recanalization was achieved. In MT-treated patients with low ASPECTS values (0–5), Kaesmacher et al. have similarly linked successful recanalization to better outcomes and safety profiles [12]. Results of a meta-analysis by Cagnazzo et al. also suggested that patients with ASPECTS values of 0–6 may benefit from MT, with successful recanalization not only heightening the probability of long-term functional improvement but also reducing sICH occurrences. Still, only about one of four patients with ASPECTS values of 4 retained functional independence after MT, and just 14% had favorable functional outcomes at ASPECTS values of 0–3 [11].

Above findings are compatible with ours, rates of functional independence, sICH, and mortality for the two ASPECTS tiers (0–5 vs 6–10) being significantly different. ASPECTS determinations ≤ 5 also strongly signaled worse 90-day clinical outcomes in our multivariable logistic regression model (Table 4). Ultimately, ASPECTS status is a measure of infarct size, an apparent correlate of functional outcomes after endovascular reperfusion therapy [15, 16]. At lower scores, patients simply have less salvageable volumes of brain tissue and larger infarct volumes, both for shadowing functional deficits.

Until now, identifying patients who might benefit most from endovascular therapy after strokes has remained a serious question. According to our data, younger age, lower baseline NIHSS score, lower HbA1c concentration, and successful recanalization are all independent predictors of favorable outcomes after MT, regardless of ASPECTS status. These parameters are also aligned with reported findings in a series of endovascular therapy recipients [13, 17–21].

For a variety of reasons, we did not examine diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) or CTA studies in this cohort. NCCT remains the most accessible and economical diagnostic tool for emergency use in patients with strokes, and it is often all that time allows. Moreover, symptom severity or existing contraindications may prohibit DWI or CTA scanning procedures.

There are several limitations of this study worth mentioning. First, this was a single-center endeavor, with a relatively sparse sampling of low-scoring patients (ASPECTS 0–5) that may have skewed the results. In addition, all ASPECTS determinations were based entirely on NCCT images; and given the scarcity of patients with the lowest of scores (ASPECTS 0–3), comparative analysis within the lower ASPECTS tier (4–5 vs 0–3) was not feasible. Whether the lowest scoring patients (0–3) actually benefit from MT remains a topic for further study. The findings provided herein must be corroborated as well by multicenter prospective studies that entail other methods of examination.

Conclusion

ASPECTS values ≤ 5 signal worse long-term functional status (mRS scores > 2) in patients with ACLVO-related AIS undergoing MT. Older age, elevated HbA1c concentration, and higher baseline NIHSS score are other independent risk factors for poor clinical outcomes, whereas successful recanalization is protective of functional independence.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes by ASPECTS 3–5 and ASPECTS 6–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaoqiu Li for help in collecting clinical data.

Abbreviations

- MT

Mechanical thrombectomy

- AIS

Acute ischemic strokes

- ACLVO

Anterior circulation large vessel occlusion

- NCCT

Non-contrast computed tomography

- ASPECTS

Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score

- mRS

Modified Rankin Scale

- sICH

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage

- mTICI

Modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction

- NIHSS

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

- ICA

Internal carotid artery

- MCA

Middle cerebral artery

- CTA

Computed tomography angiography

- DSA

Digital subtraction angiography

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- HMCAS

Hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign

- tPA

Tissue plasminogen activator

- TOAST

Trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment

Author contributions

JL and YD: the conception and design of the study. JL and JD: acquisition of data. JC, JL and LZ: analysis and interpretation of data. JL and YD: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. YD and BY: final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding

This work was supported by Application and Base Research Joint Program of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2022JH2/101500024), Project of Natural Science Foundation of Shenyang (Grant No. 20-205-4-044), Project of Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No.201602768) and Key Research and the Development Program of Liaoning Province, China (Grant No.2020JH2/10300119).

Availability of data and materials

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The Local Ethics Committee [the Institutional Review Board of the General Hospital of the Northern Theater Command] approved the study protocol and provided the reference number (Approval Number Y (2020) 012). Because the study was retrospective, the General Hospital of the Northern Theater Command Institutional Review Board does not require written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barber PA, et al. Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. Lancet. 2000;355(9216):1670–1674. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arne Potreck AF. Fatih Seker, Charlotte S Weyland, Sibu Mundiyanapurath, Sabine Heiland, Martin Bendszus and Johannes AR Pfaff, Accuracy and reliability of PBV ASPECTS, CBV ASPECTS and NCCT ASPECTS in acute ischaemic stroke a matched-pair analysis. Neuroradiol J. 2021 doi: 10.1177/19714009211015771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo AJ, et al. Effect of baseline Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score on safety and efficacy of intra-arterial treatment: a subgroup analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial (MR CLEAN) Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers WJ, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46–e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eskey CJ, et al. Indications for the Performance of Intracranial Endovascular Neurointerventional Procedures: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(21):e661–e689. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkhemer OA, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers GW, et al. Thrombectomy for Stroke at 6 to 16 Hours with Selection by Perfusion Imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, et al. Developing and predicting of early mortality after endovascular thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:1034472. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.1034472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salahuddin H, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy of M1 and M2 middle cerebral artery occlusions. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10(4):330–334. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phan K, et al. Influence of ASPECTS and endovascular thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. J NeuroInterv Surg. 2019;11(7):664–669. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cagnazzo F, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and ASPECTS </=6: a meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(4):350–355. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaesmacher J, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in ischemic stroke patients with alberta stroke program early computed tomography score 0–5. Stroke. 2019;50(4):880–888. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaidat OO, et al. Impact of age and alberta stroke program early computed tomography score 0 to 5 on mechanical thrombectomy outcomes: analysis from the STRATIS registry. Stroke. 2021;52(7):2220–2228. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyal N, et al. A multicenter study of the safety and effectiveness of mechanical thrombectomy for patients with acute ischemic stroke not meeting top-tier evidence criteria. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10(1):10–16. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo AJ, et al. MRI-based selection for intra-arterial stroke therapy: value of pretreatment diffusion-weighted imaging lesion volume in selecting patients with acute stroke who will benefit from early recanalization. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2046–2054. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivot JM, et al. Impact of diffusion-weighted imaging lesion volume on the success of endovascular reperfusion therapy. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2205–2211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal N, et al. Admission hyperglycemia and outcomes in large vessel occlusion strokes treated with mechanical thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10(2):112–117. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-012993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonetti DA, et al. Successful reperfusion, rather than number of passes, predicts clinical outcome after mechanical thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(6):548–551. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diprose WK, et al. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and outcome following endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(1):30–32. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan MA, et al. Endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke in nonagenarians compared with younger patients in a multicenter cohort. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9(8):727–731. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nogueira RG, et al. Predictors of good clinical outcomes, mortality, and successful revascularization in patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing thrombectomy: pooled analysis of the mechanical embolus removal in cerebral ischemia (MERCI) and multi MERCI trials. Stroke. 2009;40(12):3777–3783. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes by ASPECTS 3–5 and ASPECTS 6–10.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.