Abstract

Background:

Parent-child interactions are linked to childhood obesity. Music enrichment programs enhance parent-child interactions and may be a strategy for early childhood obesity prevention.

Objective:

We implemented a 2-year randomized, controlled trial to assess the effects of a music enrichment program (music, n=45) vs. active play date control (control, n=45) on parent-child interactional quality and infant weight status.

Methods:

Typically developing infants aged 9-to 15-months were enrolled with a primary caregiver in the Music Together® or a play date program. Participants attended once per week group meetings for 12 months and once per month group meetings for an additional 12 months. Parent-child interaction was measured using the Parent Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA) at baseline, month 6, 12, and 24. We used a modified intent-to-treat mixed model regression to test group differences in parent-child interactions and Weight for length z-score (zWFL) growth trajectories were modeled.

Results:

There were significant differential group changes across time for negative affect during feeding (group*month; p = 0.02) in that those parents in the music group significantly decreased their negative affect score compared with the control group from baseline to month 12 (music change = −0.279 ± 0.129; control change = +0.254 ± 0.131.; p = 0.00). Additionally, we also observed significant differential group changes across time for parent intrusiveness during feeding (group*month; p = 0.04) in that those parents in the music group significantly decreased their intrusiveness score compared with the control group from month 6 to month 12 (music change = −0.209 ± 0.121; control change = 0.326 ± 0.141; p = 0.01). We did not find a significant association between any of the changes in parental negative affect and intrusiveness with child zWFL trajectories.

Conclusion:

Participating in a music enrichment program from an early age may promote positive parent-child interactions during feeding, although this improvement in the quality of parent-child interactions during feeding was not associated with weight gain trajectories.

Keywords: Infant obesity, parenting, enriched environment, music

1. Introduction

The quality of parent-child interactions in early childhood has enduring effects on social-emotional and academic competence into adulthood.1 Various aspects of parent-child interactions, including warmth/sensitivity, negative affect or harshness, and intrusive parental behaviors have been predictive of an array of developmental outcomes.1,2 Warm/sensitive parenting behaviors, including positive tone of voice and responsiveness to child needs are beneficial to cognitive development and self-regulation ability.3,4 On the other hand, harshness, characterized by behaviors such as negative affect, angry tone of voice, and disapproval, as well as intrusiveness, characterized by interrupting and directing the child, are associated with poor developmental outcomes and increased obesity risk.5,6 Maternal and environmental factors such as depression and socioeconomic status (SES) and home environment are known to increase the risk of parental harshness and intrusiveness,7,8 therefore threatening future health and development.4,9 Parenting behavior during mealtime is of specific importance in understanding the relationships between parent-infant interactions and obesity. In a systematic review of parenting behavior during mealtime with toddlers, parent use of negative statements and discouragement were associated with higher weight status.10 Non-responsive feeding practices (defined by the lack of appropriate response to a child’s hunger/satiety cues) are shown to lead to the development of child eating behaviors that increase obesity risk, such as emotional overeating.11,12 Fostering high-quality parent-child interactions, especially during mealtime, may be a strategy for early obesity prevention in infancy, defined as 0- to 24-months of age.13,14

In the past, strategies to reduce obesity risk in early childhood have primarily consisted of changing feeding routines such as the extension of breastfeeding duration, minimizing early introduction of solid foods, and limiting intake of nutrient-poor foods.15,16 Recent interventions have shifted to include improving the quality of parent-child interactions during feeding.17,18 A study examining mothers of term infants during a 6-session interactive education group compared early feeding practices to a usual care control condition. This study reported that mothers in the intervention group increased their use of responsive feeding, but there were no differences in weight outcomes between groups.18 Furthermore, a longitudinal study compared the feeding interactions of mothers assigned to a responsive parenting intervention and mothers in a child safety control group over the first year of life. Mothers in the responsive parenting group were less likely to use non-responsive techniques linked to higher infant weight gain, such as propping the bottle and pressuring their infant to finish the bottle.19 While these intervention approaches demonstrate a promising link between the quality of parent-child interactions during mealtime and obesity, none have achieved lasting impacts on obesity risk.18,19 Previous studies have also relied on parental self-reports of parenting behaviors rather than the objective observation of parent-child interactions during feeding which provide further insight into the bidirectional relationship.17,19 Interventions that focus only on changing the parents’ behavior through education and training may not achieve the desired long-term results due to barriers such as difficulty with parent engagement or follow-through.20 Thus, there is a need for innovative intervention strategies that provide opportunities for positive parent-infant interactions and aim to enhance the quality of parent behaviors during feeding for long-term health benefits.

Across all cultures, music plays a significant role in the early parent-child relationship. Parents sing lullabies to lull infants to sleep, and the use play songs draw the infants’ attention into a shared experience. Even the characteristics of infant-directed speech, the way that caregivers often talk to infants, are described as musical due to exaggerated pitch contours, elongated vowels, and rhythmic cadences.21,22 Sharing musical experiences (e.g., singing, dancing) is associated with eliciting positive interactions between parents and infants.23-25 Community-based music enrichment programs, such as Music Together ®, are available in many communities and allow parents and infants to engage in musical activities such as singing, dancing, and playing instruments together. Increased parenting sensitivity, engagement, acceptance, responsiveness, and self-efficacy have been reported in studies investigating community music classes for parents and infants.26,27 Parents who participated in music classes with their infant also reported high levels of satisfaction and use of music at home, further indicating the potential effectiveness of community music classes as a feasible approach to improve parent-child interactions over the long-term and in turn, impacting health outcomes such as obesity.26,28 The purpose of the current study was to examine the effects of the music enrichment program, Music Together ®, on the quality of parent-child interactions during feeding and child weight. We hypothesized that: 1) there will be differences in parental variables between groups with those participating in the intervention demonstrating greater warmth, lower negative affect, and lower intrusiveness compared to the control participants, and 2) child weight gain trajectories will be moderated by parental warmth, negative affect, intrusiveness.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants consisted of parent-child dyads (n = 90, child ages 9- to15- months at baseline) recruited for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine the effects of a music enrichment program on relative motivation to eat versus engage in music among young children who were highly motivated to eat. Infants with a high motivation for food at baseline, defined by responding relatively more for food than music during a computerized task were included (NCT02936284) (see Kong et al., 2022 for full protocol). Since this was the first study conducted to test a new paradigm, families were recruited using convenience sampling for ease of recruitment. Data collection occurred at baseline, 6-months (child ages 15- to 21- months), 12- months (child ages 21- to 27-months), and 24-months (child ages 33- to 39-months). Families residing in Western New York were recruited through flyers, social media ads, and an existing database of participants from previous studies. Infants were excluded from the study if: they were preterm (< 37 weeks’ gestation), they had a low birth weight (< 2,500 g), the pregnancy was considered high-risk (e.g., mother had gestational diabetes, placental abruption, pre-eclampsia), they had developmental delay(s) as reported by their parents, their mothers were < 18 years of age at time of delivery, their mothers reported substance use, tobacco use and/or ingested ≥ 4 alcoholic drinks on a single occasion or an average of > 1 alcoholic beverage daily during pregnancy.

2.2. Study design

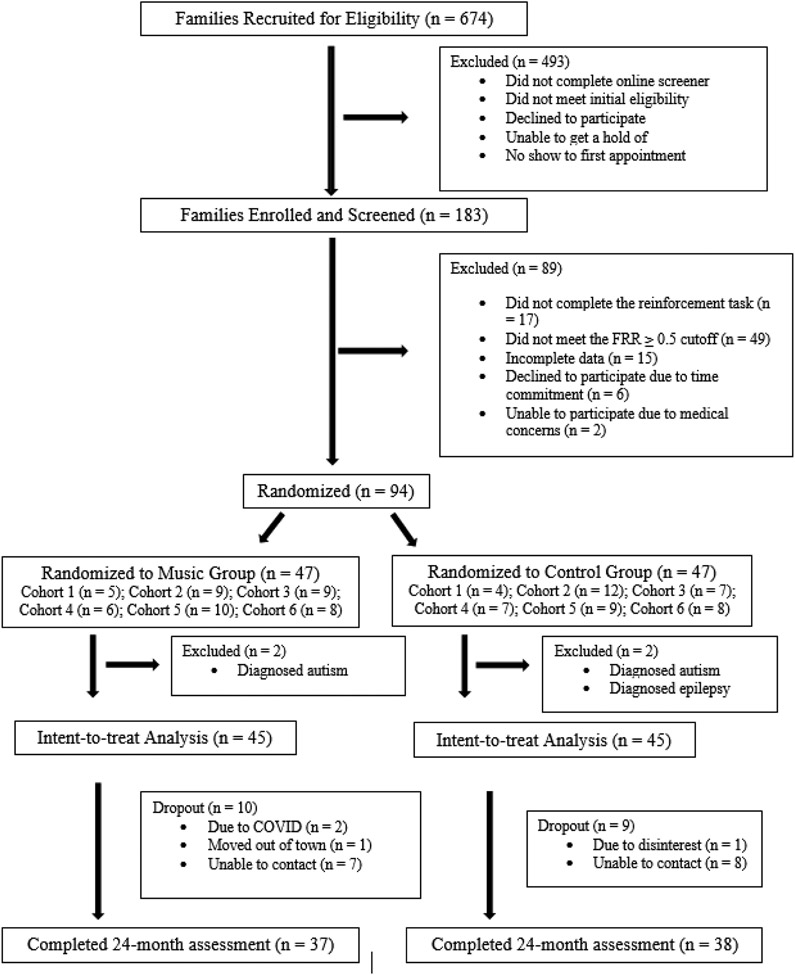

The present study is an RCT to assess the effects of a non-food alternative enrichment program (Music Together ®; the music group) versus an attention placebo play date program (the control group) on parent-infant interactions during feeding, which is one of the specific aims of the proposal. The program consisted of a 12-month intensive intervention phase of weekly group meetings and a 12-month maintenance phase of monthly group meetings. This study is a mixed design with the group as the between-subject factor and the baseline 6-, 12-, and 24- month assessments as the within-subject factor. Eligible infants were randomly assigned to the music (n = 47) or control (n = 47) groups, comprising six cohorts of families (refer to Figure 1 participant flow chart). We excluded four families from the final analysis due to physician-diagnosed autism (n = 3) and epilepsy (n= 1), which yielded n = 45 for the music group and n = 45 for the control group.

Figure 1:

Participant flow chart.

2.3. Sample size calculation

Our sample size was based on effect sizes from pilot data on an enriched music experience versus play dates for relative food reinforcement (Cohen’s D = 0.978) and standardized weight-for-length z-score (D = 0.712) (Kong et al., 2016), which could be observed at 80% power and alpha = 0.05 with 32 participants per group. To account for attrition, we recruited an additional ~25% of caregiver-infant dyads at baseline. This increased our participants number to 47 dyads per group or 94 dyads in total.

2.4. Procedures

The Institutional Review Board at the State University of New York at Buffalo approved the procedures of this study. All parents were given a description of study protocols and signed a consent form for their infant’s participation in the study. Before arrival, parents were instructed to bring their infant a meal that was similar to one eaten at home, so no standardized foods were provided. Upon arrival, parents were brought to the laboratory playroom furnished to mimic a living room with a sectional couch, bookshelf, rug, and highchair. Parents were instructed to place the infant in the highchair and feed them as they normally would at home for approximately 10 minutes. These observations were video recorded for later coding. Parents were informed that the adult completing the visit must be the primary caregiver who cares for the child on a regular basis (mother, n = 85; father, n = 6; grandparent, n = 2; other, n = 1). The term ‘parent’ is used throughout to refer to the primary caregiver participating with the infant.

2.5. Measurements

2.5.1. Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment

The Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA), is a collection 26 items assessed on 5-point global rating scales measuring affective and behavioral characteristics of the parent and child during videotaped interactions. These interactions include feeding, structured tasks, and freeplay.19,20 Since the scale is designed to be used in multiple settings, behaviors and cues are not context specific. For example, a coder might observe a parent’s contingent response to a child’s hunger cue during feeding or a child’s interest in a toy during free play. Although 26 items were assessed during the feeding interaction, only 24 items were included in the subscales, as described below. Principal components analysis with varimax rotation was conducted for data reduction purposes and factors with an eigenvalue > 1. Items that loaded onto those factors were used in subscale construction. Maternal warmth or sensitivity subscale (Cronbach’s α = .94) comprised of 10 items pertaining to warm tone of voice, positive affect and mood, contingent responsiveness to child behaviors, quality of positive verbalizations, and involvement and connectedness with the child. Maternal negative affect or harshness subscale (Cronbach’s α = .95) evaluated 4 items pertaining to disapproval/criticism, negative affect and angry/hostile tone of voice, and angry/hostile mood. Maternal intrusiveness subscale (Cronbach’s α = .86) consisted of 3 items pertaining to intrusiveness, rigidity, and negative physical contact. A research staff member, blind to group assignment, was trained by an experienced coder with over two decades of experience coding parent-infant interactions using the PCERA to reach a reliability criterion of over 80%. Interrater reliability conducted on a random selection of 20% of the videos had an ICC > .90 for all the aforementioned subscales.

2.5.2. Anthropometrics

Trained staff members collected anthropometrics of participating parents and infants. Parents’ weights were assessed using a calibrated digital weight scale measured to the nearest 0.1 kg (Tanita, Arlington Heights, IL). Parents’ heights were assessed using a calibrated stadiometer measured to the nearest 0.01 cm (SECA, Hamburg, Germany). Height measurements were taken three times by the staff member, and the median value was used for analysis. Parents’ BMIs were calculated as kg/m2 by using their measured heights and weights.

Infants’ lengths were obtained by placing the infant in a supine position on an infantometer (SECA, Hamburg, Germany). Two independent length measurements were taken by the staff member, and the mean value was used. Infants’ weights were measured to the nearest 0.001 kg with a calibrated scale (SECA, Hamburg, Germany). During the 12 and 24-month assessments, infants who were 24-months of age and older had weights assessed using a calibrated digital weight scale measured to the nearest 0.1 kg (Tanita, Arlington Heights, IL), and these infants had their heights assessed using a calibrated stadiometer measured to the nearest 0.01 cm (SECA, Hamburg, Germany). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) infant growth chart was used to calculate the infants’ weight-for-length, length-for-age, and weight-for-age z-scores. Infants’ birth weight and birth length, as well as maternal pre-pregnancy height and weight, were reported by the parent during the initial screening.

2.5.3. Demographics

Sociodemographic data were obtained using a standard questionnaire. We collected data on parents’ age, education, race, ethnicity, household income, marital status, and employment, as well as breastfeeding duration.

2.5.4. Group Status

Following baseline data collection, all eligible families were randomly assigned to either a music group or control group. The music group completed a Music Together ® program designed in collaboration with a local music studio, Betty’s Music Together ®. Participating infants and parents attended 45-minute classes as a group during which they would sing, move, and play musical instruments. Families in the intervention group were also provided with a CD and instructional songbook. They were further encouraged to listen and sing together during everyday home activities.

Families in the control group engaged in 45-minute group play dates at the same intervals as the music group. The advantage of the active play date control was that it controlled for attention and the other aspects of treatment (i.e., socialization). This allowed us to attribute any between group differences to specifics of the interventions rather than attention or other aspects of treatment. The play dates took place in a child-proofed room set-up with age-appropriate toys (excluding musical toys) at the University at Buffalo Division of Behavioral Medicine. The participating parents were encouraged to interact with other parents and infants during the play time. The families in the play date group were provided with eight different toys throughout the first year, and they were encouraged to play together during everyday home activities. A research staff member was present during the music group and play dates for the purpose of video recording and taking attendance. Research staff members did not interact with parents or children unless a concern arose.

2.6. Data Analytic Strategy

Group baseline characteristics were compared using analysis of variance or Pearson’s chi-square test for frequency data. We performed a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis using all non-excluded and randomized subjects. The primary outcomes were analyzed using population averaged marginal models in SAS PROC MIXED, which handles missing data by using maximum likelihood estimation and retains all randomized subjects in the analysis. We selected a reasonably fitted model satisfying the model assumptions; the residual plots and the residual-based fit statistics Akaike’s Information Criterion for various covariance structures were examined. The models included group, months, and the group*month interaction as class variables using an autoregressive (AR1) covariance structure and accounted for the clustering of multiple observations within participants. Models included baseline scores of primary outcome variables, children’s sex, children’s age and a 2-level caregiver categorical covariate indicating which families had the same or different caregiver at each assessment timepoint. In addition to the omnibus group*month effect, planned comparisons and contrasts tested for group differences from baseline to each follow-up assessment (6, 12, and 24 months) based on the fitted mixed models.

To examine for associations between change in parent-child interaction and child zWFL trajectories, we conducted a mixed regression model. Each model limited the trajectory range to that of the predictor change, so (6, 12 or 24) month changes predicted 6-, 12-, or 24-month zWFL trajectory accordingly. These models utilized autoregressive AR1 covariance structure and random effects of intercept and months while accounting for within individual clustering of multiple observations. We also examined the effect of child’s sex on the change in parent-child interactions and zWFL trajectories at all timepoints. All mixed models were performed using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.4 (copyright © 2020 y SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All values in tables and figures are estimates based on the models presented.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and Attrition

Ninety-four parent-infant dyads were randomized. The final sample consisted of 90 parent-infant dyads. Of the 90 dyads, 69 completed the post-intensive intervention phase assessment after 12-months (76.7%), and 71 completed the post-follow-up phase assessment after 24-months (78.8%). Attrition at 24 months did not differ between groups (music = 20.0%, control = 22.2%, chi-square = 0.07, p = 0.80). No significant difference between groups was observed in demographic and anthropometric parameters of parent-infant dyads at baseline (Table 1). Our sample consisted of primarily highly educated (college graduate or higher = 71.1%), mid-upper income (≥ $50,000 = 81.5%) White families (mother’s race = 86.7%). There was a significant group difference in class attendance (music = 75.9%, control = 50.1%, p = 0.00).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Music Group (n=45) | Control Group (n=45) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) |

| Child | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 21 (46.7) | 22 (48.9) | ||

| Age, month | 12.10 (1.69) | 11.93 (2.05) | ||

| Baseline ZWFL | 0.60 (0.87) | 0.57 (0.92) | ||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| American Indian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Asian | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| White | 35 (77.7) | 37 (82.2) | ||

| Multiracial | 9 (20.0) | 4 (8.9) | ||

| No Response | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic (single race) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Hispanic (multiracial) | 4 (8.9) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| Mother | ||||

| Age, year | 31.6 (3.9) | 33.2 (4.1) | ||

| Baseline BMI | 30.2 (7.9) | 30.1 (7.6) | ||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| American Indian | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| Asian | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| White | 39 (86.7) | 39 (86.7) | ||

| Multiracial | 4 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No Response | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.24) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic (single race) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Hispanic (multiracial) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Some college or less | 13 (28.9) | 13 (28.9) | ||

| College graduate or more | 32 (71.1) | 32 (71.1) | ||

| Household | ||||

| Total income, $ | ||||

| < $50 000 | 7 (15.5) | 9 (20.0) | ||

| ≥ $50 000 | 35 (77.8) | 35 (77.8) | ||

| No response | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | ||

SD=Standard Deviation

3.2. Changes in Parental Warmth, Negative Affect, and Intrusiveness During Feeding

We examined changes in parental warmth, negative affect, and intrusiveness across time for the music and control groups from baseline to month 6 (mid-intensive intervention phase), month 12 (post-intensive intervention phase) and month 24 (post-intervention maintenance phase). The change scores for parental warmth, negative affect, and intrusiveness at all assessment time points are presented in Tables 2-4 respectively. Given the significant group difference in class attendance, we conducted a supplementary analysis on the influence of attendance on the parenting outcomes. We observed no attendance effects.

Table 2.

Change scores for parental warmth during feeding at all time points (±SEM)

| Music | Control | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to Month 6 | 0.314 ± 0.109 | 0.147 ± 0.119 | 0.3024 |

| Baseline to Month 12 | 0.180 ± 0.119 | 0.137 ± 0.132 | 0.8121 |

| Baseline to Month 24 | 0.246 ± 0.128 | 0.203 ± 0.128 | 0.812 |

| Month 6 to Month 12 | −0.134 ±0.112 | −0.010 ± 0.130 | 0.4688 |

| Month 6 to Month 24 | −0.067 ±0.128 | 0.057 ±0.136 | 0.509 |

| Month 12 to Month 24 | 0.067 ± 0.118 | 0.066 ± 0.129 | 0.9972 |

Significant difference in change score (p<0.05)

Table 4.

Change scores for intrusiveness during feeding at all time points (±SEM)

| Music | Control | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to Month 6 | +0.060 ± 0.118 | −0.203 ± 0.129 | 0.135 |

| Baseline to Month 12 | −0149. ± 0.127 | ±0.124 ± 0.141 | 0.153 |

| Baseline to Month 24 | −0.144 ± 0.136 | −0.084 ± 0.136 | 0.758 |

| Month 6 to Month 12 | −0.209 ± 0.121 | ±0.326 ± 0.141 | 0.005* |

| Month 6 to Month 24 | −0.203 ±0.137 | 0.118 ±0.146 | 0.109 |

| Month 12 to Month 24 | ±0.005 ± 0.128 | −0.208 ± 0.140 | 0.2619 |

Significant difference in change score (p<0.05)

3.2.1. Warmth.

Overall, we did not observe a significant difference between groups at any timepoint for parental warmth during feeding (group*month; p = 0.76).

3.2.2. Negative affect.

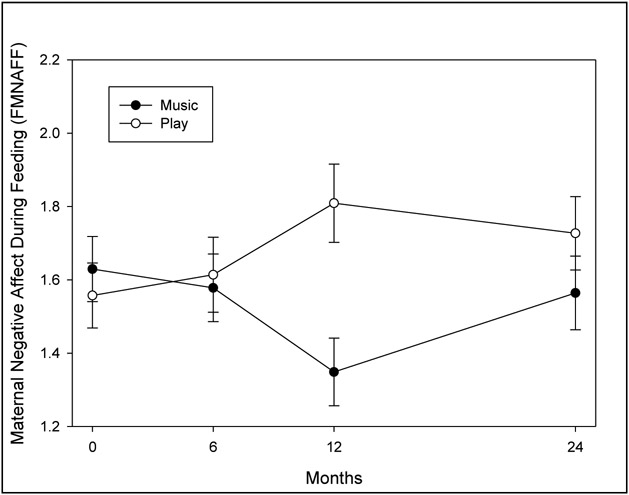

Changes in parental negative affect during feeding at each timepoint are shown in Figure 2, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. There were significant differential group changes across time for negative affect during feeding (group*month; p = 0.02). Parents in the music group significantly decreased their negative affect score in comparison to the control group from baseline to month 12 (music change= −0.279 ± 0.129; control change= +0.254 ± 0.131.; p = 0.00). The difference between groups was also observed from month 6 to month 12 (music change = −0.229 ± 0.114; control change = +0.195 ± 0.133; p = 0.02). We did not observe a group difference at month 24.

Figure 2:

Changes in maternal negative affect during feeding at all assessment time points (baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months) during the 12-month intensive intervention and 12-month follow-up maintenance phase. Ninety 9-15-month-old infants were randomized to either the music enrichment program (music) or a play date program (control) group. Model adjusted for covariates is present and data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

3.2.3. Intrusiveness.

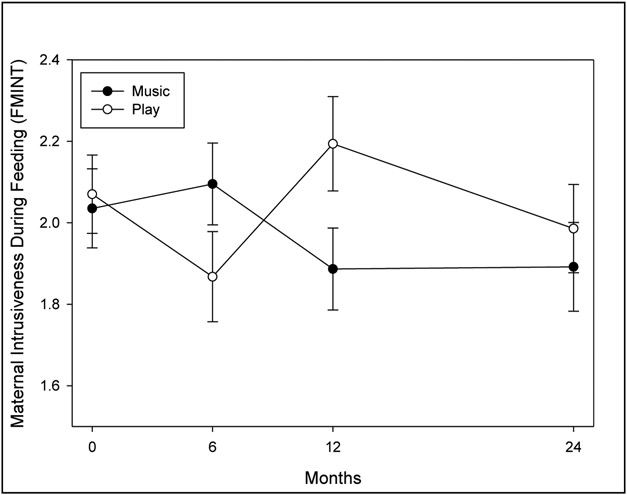

Changes in parent intrusiveness during feeding at each timepoint are shown in Figure 3. There were significant differential group changes across time for parent intrusiveness during feeding (group*month; p = 0.04). Parents in the music group significantly decreased their intrusiveness score in comparison to the control group from month 6 to month 12 (music change = −0.209 ± 0.121; control change = 0.326 ± 0.141; p = 0.01). The difference between groups was not observed at any of the other timepoints.

Figure 3:

Changes in maternal intrusiveness during feeding at all assessment time points (baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months) during the 12-month intensive intervention and 12-month follow-up maintenance phase. Ninety 9-15-month-old infants were randomized to either the music enrichment program (music) or a play date program (control) group. Model adjusted for covariates is present and data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

3.3. Change in parental warmth, negative affect, and intrusiveness during feeding with zWFL trajectories.

We examined change in parent-child interactions and zWFL trajectories at all timepoints. We did not find significant association between any of the changes in parental warmth, negative affect, and intrusiveness with child zWFL trajectories in both non-adjusted and covariate-adjusted models (Table 5). We also examined child’s sex on the change in parent-child interactions and zWFL trajectories at all timepoints and found no significant effect.

Table 5.

Moderation of child weight-for-length z-score trajectories over time by parent-child interaction variables (moderator*month)

| Epoch | Moderator | df | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to Month 6 | Warmth | 1,69 | 0.24 | 0.622 |

| Baseline to Month 12 | Warmth | 1,134 | 1.99 | 0.161 |

| Baseline to Month 24 | Warmth | 1,186 | 0.54 | 0.464 |

| Baseline to Month 6 | Negative affect | 1,69 | 0.37 | 0.547 |

| Baseline to Month 12 | Negative affect | 1,134 | 0.65 | 0.422 |

| Baseline to Month 24 | Negative Affect | 1,186 | 0.03 | 0.868 |

| Month 6 to Month 12 | Intrusiveness | 1,69 | 1.05 | 0.309 |

| Month 6 to Month 24 | Intrusiveness | 1,134 | 0.01 | 0.937 |

| Month 12 to Month 24 | Intrusiveness | 1,186 | 0.11 | 0.742 |

4. Discussion

In the current study, we examined the effects of a music enrichment program, Music Together ®, on the quality of parent-child interactions during feeding. Parents who participated with their child in the music enrichment program displayed significantly less negative affect and intrusiveness during feeding at the completion of the intensive phase of the intervention (12 months post-intervention) compared to parents in the control group. However, these group effects were not maintained over time at the maintenance phase (24 months post-intervention). The observed improvement in parental negative affect and intrusiveness were not associated with a reduction in child weight gain trajectories from baseline to 24 months post-intervention.

Research suggests that promoting positive relationships between parents and young children may be a promising new avenue in preventing childhood obesity,13,29,30 including a systematic review published by our team.3 One explanation for this may be through the development of self-regulation, which in part relies on the quality of parent-infant interactions. Prior to an infant’s ability to self-regulate, parents develop patterns of interaction with their infants that promote external regulation.31 Consistent and predictable responses to infant cues support the development of self-regulatory ability.32 Poor self-regulation skills are related to obesogenic behaviors such as using food to regulate and emotional overeating.13 Inappropriate parenting behaviors such as using food to soothe, or feeding in the absence of hunger cues, might heighten children’s emotional arousal or promote maladaptive eating behaviors that can lead to obesity later in life.33 Results from our study show that parental negative affect and intrusiveness assessed during infant/toddler feeding can be reduced through participation in a music enrichment program. Although we did not find an association between changes in parent intrusiveness and child zWFL trajectories, these findings may be an important step to further understanding the relationship between feeding practices and early childhood obesity.34

There is a need for interdisciplinary collaboration on intervention approaches that focus on the improvement of positive parenting behavior during infancy.17,35,36 Our findings support that the novel use of a community-based music enrichment class reduces parental negative affect and intrusiveness. This finding indicates that readily available music programs in many communities may be a feasible way to improve parenting and modify the development of obesogenic eating behaviors later in life. Although the mechanisms through which music enrichment programs can influence positive parenting behaviors are not yet known, one possible pathway may be through positive parent-child experiences facilitated by music activities. Evolutionary perspectives on the role of music in human life focus in part to the unique ability of music to draw a parent and child into a shared experience.37 The characteristic way parents sing to their child, known as infant-directed singing, has been demonstrated to capture and sustain a child’s attention to the parent better than infant directed speaking or reading.38,39 Unlike other interventions to improve parenting behaviors that focus on educational materials and teaching strategies, musical experiences naturally facilitate enjoyable interactions between parent and infant.40 Shared positive experiences, such as those that occur during music engagement, can increase oxytocin levels in both parents and infants. This is associated with prosocial behaviors, reward center activation, and higher motivation for future positive engagement .41,42 Furthermore, synchrony and music listening have been shown to increase oxytocin in both children and adults, supporting the indication of a positive correlation between parent-infant music classes and increased oxytocin.43,44 Still, additional research on the measurements of oxytocin levels in parents and infants during a music class is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Another possible explanation for the unique effectiveness of music enrichment programs on improving parental behaviors is through rhythm. During musical activities, rhythm (external timing) helps to coordinate parent-infant interactions.45 This can be observed in the way dyads move together while listening to music. Synchronous experiences, moving together in time, have been shown to support positive interactions between adults and infants as young as 14 months.27 In the Music Together ® classes, simple, repetitive songs with strong rhythmic pulses paired with rhythmic motions, such as clapping and patting, provided a rich context for parent-child shared rhythmic experiences. Building positive interactions through synchronous rhythmic engagement during class may motivate parents to replicate rhythmic activities at home, embedding them into everyday routines that may help to extend the benefits into the longer-term.

In our study, the improvement of parental negative affect and intrusiveness were not associated with lower weight gain among children in the music group. It is possible that early intervention may provide a layer of protection against obesity related behaviors; however, the age at which these behavioral changes affect weight differences is yet to be known. Additionally, the results of this paper are similar to findings from our primary outcome paper (see Kong et al., 2022) in that participation in the music intervention was not associated with changes in child zWFL. The majority of research investigating eating behaviors and weight status in children involve school age children and older.46,47 For example, Harris and colleagues (2020) investigated the effects of a responsive parenting intervention at age 30 months on child emotional overeating, a behavior linked to obesity development. The researchers found that participants in the responsive parenting intervention perceived lower child emotional overeating at age three to be a result of parents’ less frequent use of food to soothe the child during infancy, which further indicates a promising link to obesity prevention.17 While we did observe significant reductions in parental negative affect and intrusiveness, future research is needed to examine the association between change in parenting and change in obesity risk from infancy through school-age in order to further understand the impact of the early parent-child relationship on the development of childhood obesity. It may be that participation in the music intervention did not change the parenting behaviors enough to have an impact across multiple contexts beyond feeding which may also play an important role in how the parent-child relationship protects against obesity.

Our results showed that the initial significant changes in parent-child interactions were not sustained after the 24-month maintenance phase. Other intervention studies involving parenting behavior change have similarly observed difficulty with long-term results.48 The transition from infancy to toddlerhood, which coincided with the maintenance phase of our intervention, involves an increase in child independence and oppositional behaviors.49,50 Parenting during this period shifts from a primarily nurturing role to one that includes the formation of boundaries and providing guidance.49 These changes in the parent-child relationship may require a longer intervention period to support adapting to the onset of expanding developmental skills. Future research should investigate treatment duration in order to sustain beneficial parent behavior change over the longer-term.

Despite being a novel intervention to improve parent-child interaction during mealtime, there are several limitations in the present study. First, while these results indicate that the intervention may be effective in changing parenting behavior, the intervention did not work to change infant weight trajectories. Quality of parenting is a proximal obesity-related behavior; however, our sample size and duration of the program may not be enough to detect weight differences in this study. Second, both the music and control conditions were in a group setting where parents and infants could engage socially with one another. Therefore, it is unclear how the social aspect of both programs may have influenced the treatment effect. Third, the current study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention in a population of healthy, typical-developing infants. As such, infants with a diagnosed developmental delay, who may have a higher risk of challenges related to the parent-infant relationship, were excluded. Similarly, our study cannot be generalized to other more diverse populations who may be at risk for high quality parent-child interactions or obesity development due to sociodemographic backgrounds (i.e., low-income families). Our lack of significant findings for the parental warmth subscale may also be due to the low-risk sample as participants in our study had high parental warmth scores at baseline. Future research should specifically investigate the effects of this early intervention strategy on at-risk infants (i.e., low SES household). Lastly, while negative parenting behaviors and harshness are important components of parent-infant interaction related to obesity risk, the use of additional parent-infant relationship measures such as predictability, flexibility, and synchrony in future research could extend our understanding on how the parent-child relationship may be enhanced through music enrichment programs.51,52

In conclusion, participating in a music enrichment program from an early age may promote positive parent-child interactions during feeding, although this improvement in the quality of parent-child interactions during feeding was not associated with weight gain trajectories.

Table 3.

Change scores for negative affect during feeding at all time points (±SEM)

| Music | Control | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to Month 6 | −0.050 ± 0.112 | +0.058 ± 0.121 | 0.513 |

| Baseline to Month 12 | −0.279 ± 0.129 | +0.254 ± 0.131 | 0.003* |

| Baseline to Month 24 | −0.064 ± 0.125 | +0.171 ± 0.125 | 0.186 |

| Month 6 to Month 12 | −0.229 ±0.114 | +0.195 ± 0.133 | 0.017* |

| Month 6 to Month 24 | −0.014 ±0.127 | 0.113 ±0.135 | 0.494 |

| Month 12 to Month 24 | −0.215 ± 0.123 | −0.082 ± 0.132 | 0.098 |

Significant difference in change score (p<0.05)

Funding:

This work was supported by the Nation Institutes of Health R01 (HD087082)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethics Statement

The procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the State University of New York at Buffalo. All parents were given a description of study protocols and signed a consent form for their infant’s participation in the study.

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Raby KL, Roisman GI, Fraley RC, Simpson JA. The enduring predictive significance of early maternal sensitivity: Social and academic competence through age 32 years. Child development. 2015;86(3):695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiden RD, Molnar DS, Granger DA, Colder CR, Schuetze P, Huestis MA. Prenatal tobacco exposure and infant stress reactivity: role of child sex and maternal behavior. Developmental psychobiology. 2015;57(2):212–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong KL, Anzman-Frasca S, Burgess B, Serwatka C, White HI, Holmbeck K. Systematic Review of General Parenting Intervention Impacts on Child Weight as a Secondary Outcome. Childhood Obesity. 2022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters SF, Virmani EA, Thompson RA, Meyer S, Raikes HA, Jochem R. Emotion regulation and attachment: Unpacking two constructs and their association. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment. 2010;32(1):37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollenstein T, Tighe AB, Lougheed JP. Emotional development in the context of mother–child relationships. Current opinion in psychology. 2017;17:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeon H-J, Peterson CA, DeCoster J. Parent–child interaction, task-oriented regulation, and cognitive development in toddlers facing developmental risks. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2013;34(6):257–267. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burchinal M, Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M, Investigators KFLP. Cumulative social risk, parenting, and infant development in rural low-income communities. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2008;8(1):41–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eiden RD, Godleski S, Colder CR, Schuetze P. Prenatal cocaine exposure: the role of cumulative environmental risk and maternal harshness in the development of child internalizing behavior problems in kindergarten. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2014;44:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong KL, Shisler S, Eiden RD, Anzman-Frasca S, Piazza J. Examining the Relationship between Infant Weight Status and Parent–Infant Interactions within a Food and Nonfood Context. Childhood Obesity. 2022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmeier H, Skouteris H, Hetherington M. Systematic research review of observational approaches used to evaluate mother-child mealtime interactions during preschool years. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2015;101(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.KI DiSantis, Hodges EA Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). Apr 2011;35(4):480–92. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller N, Mallan KM, Byrne R, de Jersey S, Jansen E, Daniels LA. Non-responsive feeding practices mediate the relationship between maternal and child obesogenic eating behaviours. Appetite. Aug 1 2020;151:104648. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson SE, Keim SA. Parent-Child Interaction, Self-Regulation, and Obesity Prevention in Early Childhood. Current obesity reports. Jun 2016;5(2):192–200. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0208-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schore AN. Back to basics: attachment, affect regulation, and the developing right brain: linking developmental neuroscience to pediatrics. Pediatr Rev. Jun 2005;26(6):204–17. doi: 10.1542/pir.26-6-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Askie LM, Espinoza D, Martin A, et al. Interventions commenced by early infancy to prevent childhood obesity—The EPOCH Collaboration: An individual participant data prospective meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials. Pediatric obesity. 2020;15(6):e12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mihrshahi S, Jawad D, Richards L, et al. A review of registered randomized controlled trials for the prevention of obesity in infancy. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(5):2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris HA, Anzman-Frasca S, Marini ME, Paul IM, Birch LL, Savage JS. Effect of a responsive parenting intervention on child emotional overeating is mediated by reduced maternal use of food to soothe: The INSIGHT RCT. Pediatric obesity. Oct 2020;15(10):e12645. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D, Magarey A. Outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e109–e118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage JS, Hohman EE, Marini ME, Shelly A, Paul IM, Birch LL. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant feeding practices: randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2018;15(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AL, Miller SE, Clark KM. Child, caregiver, family, and social-contextual factors to consider when implementing parent-focused child feeding interventions. Current nutrition reports. 2018;7(4):303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernald A, Kuhl P. Acoustic determinants of infant preference for motherese speech. Infant behavior and development. 1987;10(3):279–293. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trehub SE, Trainor L. Singing to infants: Lullabies and play songs. Advances in infancy research.1998;12:43–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cirelli LK, Einarson KM, Trainor LJ. Interpersonal synchrony increases prosocial behavior in infants. Developmental science. Nov 2014;17(6):1003–11. doi: 10.1111/desc.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persico G, Antolini L, Vergani P, Costantini W, Nardi MT, Bellotti L. Maternal singing of lullabies during pregnancy and after birth: Effects on mother-infant bonding and on newborns' behaviour. Concurrent Cohort Study. Women Birth. Aug 2017;30(4):e214–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wetherick D. Music in the family: music making and music therapy with young children and their families. J Fam Health Care. 2009;19(2):56–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teggelove K, Thompson G, Tamplin J. Supporting positive parenting practices within a community-based music therapy group program: Pilot study findings. Journal of Community Psychology. 2019;47(4):712–726. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson JM, Berthelsen D, Abad V, Williams KE, Bradley J. Impact of music therapy to promote positive parenting and child development. Journal of Health Psychology. April/01 2008;13:226–38. doi: 10.1177/1359105307086705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong KL, Eiden RD, Feda DM, et al. Reducing relative food reinforcement in infants by an enriched music experience. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). Apr 2016;24(4):917–23. doi: 10.1002/oby.21427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard K, Frost A, Jelinek C, Dozier M. Secure attachment predicts lower body mass index in young children with histories of child protective services involvement. Pediatric obesity. Jul 2019;14(7):e12510. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Holland ML, Slade A, Close N, Mayes LC. A Home Visiting Parenting Program and Child Obesity: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. Feb 2018;141(2)doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman R. Parent-infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. Mar-Apr 2007;48(3-4):329–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sameroff A. A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child development. 2010;81(1):6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul IM, Williams JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. The intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories (INSIGHT) study. BMC pediatrics. 2014;14(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ardic C, Usta O, Omar E, Yıldız C, Memis E. Effects of infant feeding practices and maternal characteristics on early childhood obesity. Arch Argent Pediatr. Feb 1 2019;117(1):26–33. Efectos de las prácticas alimentarias durante la lactancia y de las características maternas en la obesidad infantil. doi: 10.5546/aap.2019.eng.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson SE, Gooze RA, Lemeshow S, Whitaker RC. Quality of early maternal-child relationship and risk of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. Jan 2012;129(1):132–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergmeier H, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J, et al. Early mother-child dyadic pathways to childhood obesity risk: A conceptual model. Appetite. 2020;144:104459–104459. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trehub SE. Nurturing infants with music. International Journal of Music in Early Childhood. 2019;14(1):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shannon K. Infant behavioral responses to infant-directed singing and other maternal interactions. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29(3):456–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trainor LJ, Clark ED, Huntley A, Adams BA. The acoustic basis of preferences for infant-directed singing. Infant Behavior and Development. 1997;20(3):383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harvey AR. Links Between the Neurobiology of Oxytocin and Human Musicality. Review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2020-August-26 2020;14doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scatliffe N, Casavant S, Vittner D, Cong X. Oxytocin and early parent-infant interactions: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2019/October/10/ 2019;6(4):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldman R. PARENT–INFANT SYNCHRONY: A BIOBEHAVIORAL MODEL OF MUTUAL INFLUENCES IN THE FORMATION OF AFFILIATIVE BONDS. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012;77(2):42–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00660.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feldman R. Sensitive periods in human social development: New insights from research on oxytocin, synchrony, and high-risk parenting. Development and psychopathology. 2015;27(2):369–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ooishi Y, Mukai H, Watanabe K, Kawato S, Kashino M. Increase in salivary oxytocin and decrease in salivary cortisol after listening to relaxing slow-tempo and exciting fast-tempo music. PloS one. 2017;12(12):e0189075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mössler K, Schmid W, Aßmus J, Fusar-Poli L, Gold C. Attunement in Music Therapy for Young Children with Autism: Revisiting Qualities of Relationship as Mechanisms of Change. J Autism Dev Disord Nov 2020;50(11):3921–3934. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04448-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omar OM, Massoud MN, Ibrahim AG, Khalaf NA. Effect of early feeding practices and eating behaviors on body composition in primary school children. World Journal of Pediatrics. 2022;18(9):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayine P, Selvaraju V, Venkatapoorna CM, Bao Y, Gaillard P, Geetha T. Eating behaviors in relation to child weight status and maternal education. Children. 2021;8(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahlweg K, Heinrichs N, Kuschel A, Bertram H, Naumann S. Long-term outcome of a randomized controlled universal prevention trial through a positive parenting program: is it worth the effort? Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health. 2010;4(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verhoeven M, Junger M, Van Aken C, Deković M, Van Aken MA. Parenting during toddlerhood: Contributions of parental, contextual, and child characteristics. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(12):1663–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwon K-A, Han S, Jeon H-J, Bingham GE. Mothers' and fathers' parenting challenges, strategies, and resources in toddlerhood. Early Child Development and Care. 2013;183(3-4):415–429. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leerkes EM, Nayena Blankson A, O'Brien M. Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child development. May-Jun 2009;80(3):762–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lobo FM, Lunkenheimer E. Understanding the parent-child coregulation patterns shaping child self-regulation. Developmental psychology. Jun 2020;56(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037/dev0000926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]