ABSTRACT

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the efficacy of nebulised magnesium in the treatment of acute exacerbation of COPD. PubMed and Embase databases were searched for randomised controlled trials comparing any dose of nebulised magnesium sulphate with placebo for treatment of acute exacerbation of COPD, published from database inception till 30 June 2022. Bibliographic mining of relevant results was performed to identify any additional studies. Data extraction and analyses were done independently by review authors and any disagreements were resolved through consensus. Meta-analysis was done using a fixed-effect model at clinically significant congruent time points reported across maximum studies to ensure comparability of treatment effect. Four studies met the inclusion criteria, randomly assigning 433 patients to the comparisons of interest in this review. Pooled analysis showed that nebulised magnesium sulphate improved pulmonary expiratory flow function at 60 minutes after initiation of intervention compared to placebo [median difference (MD) 9.17%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.94 to 15.41]. Analysis of expiratory function in terms of standardised mean differences (SMD) revealed a small yet significant positive effect size (SMD 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.43). Among the secondary outcomes, nebulised magnesium sulphate reduced the need for ICU admission (risk ratio 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.95), amounting to 61 fewer ICU admissions per 1000 patients. No difference was noted in the need for hospital admission, need for ventilatory support, or mortality. No adverse events were reported. Nebulised magnesium sulphate improves pulmonary expiratory flow function and reduces the need for ICU admission in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD.

KEY WORDS: Bronchial asthma, COPD, intensive care, magnesium, mechanical ventilation, nebulizer

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an inflammatory condition of the lung characterised by the destruction of lung parenchyma and expiratory air-flow limitation. Acute worsening of the clinical symptoms in a patient of COPD, manifesting as an increase in cough, sputum production or dyspnoea, is termed as an acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD). Inhaled bronchodilators (long- and short-acting beta-agonists and muscarinic antagonists), corticosteroids alone or in various combinations and antibiotics form the mainstay of management of AECOPD. In addition, for special patient profiles, methylxanthines and alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy may be considered. Other non-pharmacological interventions including pulmonary rehabilitation, special exercise training, nutritional modifications, and vaccination against respiratory pathogens form the current management principles for COPD.[1]

Magnesium is a smooth muscle relaxant and has bronchodilating properties, possibly by antagonizing calcium-mediated smooth muscle contraction.[2,3] Intravenous magnesium has been shown to improve bronchospasm in patients with asthma and COPD.[4,5] Intravenous magnesium administration, however, is not without potential adverse effects. The main concerns include hypotension, respiratory depression, and bradyarrhythmias. These may be especially dangerous in elderly patients with compromised cardio-pulmonary reserve. Nebulised magnesium, by acting directly on the airways, can potentially alleviate bronchospasm at a much lower risk of systemic toxicity.[6]

Despite its potential advantages, current guidelines do not recommend the use of nebulised magnesium in the treatment of AECOPD.[1] We have therefore conducted this meta-analysis to explore the utility of nebulised magnesium sulphate as an adjunct to the standard care of AECOPD. The primary review question was does nebulized magnesium sulphate compared to placebo improve pulmonary expiratory flow function in patients with AECOPD.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in both English and the non-English language, in the peer-reviewed journal, were included in this meta-analysis. Data from ongoing un-published trials were not included. Studies on adult patients presenting to the hospital with a provisional diagnosis of AECOPD were included. Trials comparing any dose of inhaled or nebulized magnesium sulphate versus placebo, as an adjunct to standard therapy for AECOPD, were included. Patients with AECOPD often receive different pharmacological agents as a part of standard treatment. We included studies that followed various treatment protocols, provided that all pharmacological agents, apart from nebulized magnesium, were received by both groups. The primary outcome was a change in pulmonary expiratory flow function following nebulization with magnesium sulphate. Secondary outcomes included the need for hospitalization, need for ICU admission, need for non-invasive or invasive ventilation, perceived dyspnoea score, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, serum magnesium level, adverse events, and mortality.

Electronic searches

PubMed and Embase data bases were searched, from database inception up to 30 June 2022, with the following keyword algorithm string:

#1: (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[Title/Abstract] OR COPD[Title/Abstract] OR chronic obstructive lung disease[Title/Abstract] OR chronic obstructive airway disease[Title/Abstract])

#2: (nebulised[Title/Abstract] OR nebulized[Title/Abstract] OR nebulisation[Title/Abstract] OR nebulization[Title/Abstract] OR inhaled[Title/Abstract])

#3 (‘magnesium[Title/Abstract] OR MgSO4[Title/Abstract])

#4 #1 AND #2 AND #3

Trials meeting inclusion criteria were identified and included.

Searching other sources

Reference lists of included articles, and any systematic reviews and meta-analyses identified through this keyword search, were also scanned for possible trial candidates that may have been missed in the initial search.

Study selection

Two review authors (PKD, SN) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify eligible studies meeting the inclusion criteria. A third review author (DD) was approached in the event of any disagreement regarding the inclusion of a study. Full texts of the studies were retrieved and scanned in detail to ensure eligibility for inclusion. Citations of included studies were screened to ensure that no eligible study on the topic of interest was overlooked during the initial search.

Data collection

Study characteristics and outcome data were recorded by all review authors independently. Disagreements were resolved by reaching a consensus through discussion. Data were compiled and transferred into the Review Manager {(RevMan) [Computer program] version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020} file. The accuracy of data entry was double-checked independently by two review authors (AA, SRC).

Data synthesis and analysis of outcomes

Continuous data were analysed as mean differences (MDs) and dichotomous variables were expressed as risk ratios (RRs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When different measurement modalities were used to assess the same quantitative functional parameter, pooled data were analysed as standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI. Meta-analysis was done at the clinically significant congruent time points reported across maximum studies to ensure comparability of treatment effect. Qualitative data were analysed using M-H test (Mantel–Haenszel) and quantitative data were analysed using inverse variance (I-V) methods.

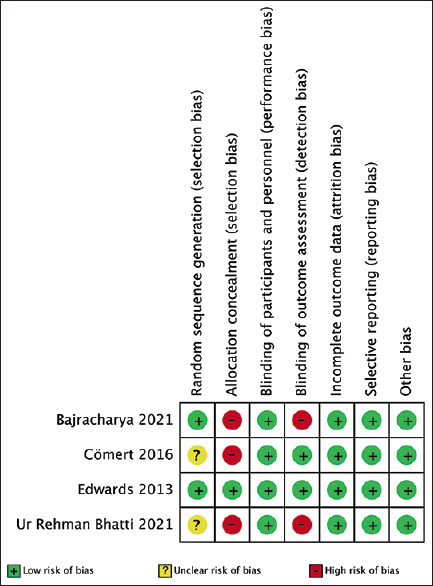

Risk of bias was independently assessed by all review authors using criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The risk of bias was assessed with respect to the following domains: random sequence generation (selection bias); allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective outcome reporting (reporting bias); and other bias (e.g. bias due to conflict of interest, source of trial funding, etc.). Each potential source of bias was graded as high, low, or unclear, based on the disclosures and information available from the main text of the included studies. The risk of biased judgements across different studies for each of the domains was summarised.

In case data regarding a particular parameter at a specific time point were not reported in a study, but data at time points before and after the concerned time point were reported, then the average of the pre- and post-values was taken.

Heterogeneity and/or inconsistencies were reported as I2 values.

Funnel plot was created to explore the possibility of publication bias. Fixed-effect model was used to meta-analyse the data in case a number of studies was 5 or less.[7] In case studies used different pulmonary function parameters to assess expiratory flow function, such as forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), sensitivity analysis was done for each parameter separately.

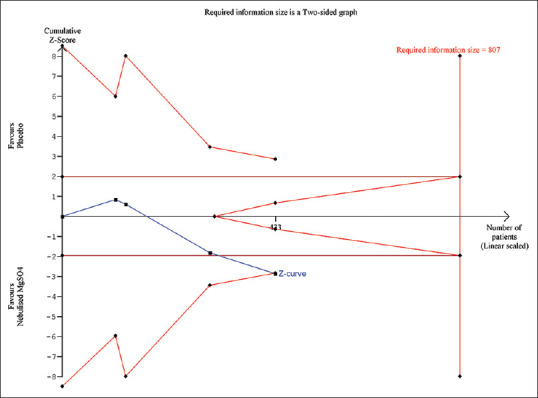

Trial sequential analysis

To assess the robustness of the meta-analysis, a trial sequential analysis (TSA) was performed for the primary outcome using TSA program version 0·9.5·10 Beta (www.ctu.dk/tsa). Positive and negative conventional boundaries were added assuming a two-sided alfa error of 5%. Meta-analysis monitoring boundaries for definite benefit and harm, diversity-adjusted required information size (RIS), and boundaries for futility were identified assuming an overall type I error of 5%, power of 80%, and pooled effect size obtained from the actual meta-analysis.

A summary of findings table was created for main outcomes that could be combined across studies using GRADEpro GDT (GRADE Profiler Guideline Development Tool; McMaster University and Evidence Prime; 2022; www.gradepro.org). The quality of evidence obtained regarding each outcome in relation to the studies that contributed data towards it was assessed using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) independently by all review authors. Disagreements were resolved by reaching a consensus through discussion.

RESULTS

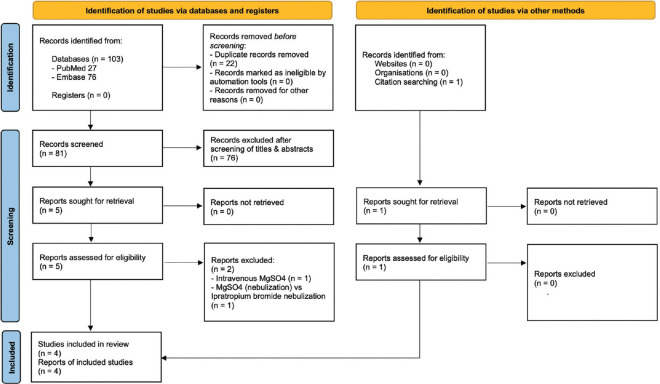

Electronic searches yielded at a total of 103 references (27 references in PubMed, 76 references in Embase). After filtering out duplicates, 81 items remained. Primary screening of titles and abstracts resulted in the exclusion of 76 items. Full texts of the remaining five studies, along with their reference lists, were retrieved and screened to identify trials that meet our inclusion criteria.[8,9,10,11,12] Bibliographic mining revealed one additional study of interest that was missed in the initial electronic database search.[13] Of the six studies trials that underwent full-text screening, one trial involved the use of magnesium sulphate through the intravenous route (not earlier specified in the abstract),[8] while another compared magnesium sulphate (nebulisation along with intravenous) versus ipratropium bromide nebulisation.[10] Therefore, these two studies were excluded. Of the four RCTs finally selected, the full text of one trial was in Turkish.[11] Google Translate tool was used to translate the manuscript into English. The translated manuscript was read its legibility was confirmed independently by two review authors (PKD, AA). Search, screening, and selection of studies were conducted as per PRISMA statement [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of selection of studies

Four studies met the inclusion criteria,[9,11,12,13] that randomly assigned 433 patients with AECOPD to receive either nebulised magnesium or placebo (normal saline) along with standard treatment for AECOPD. Standard treatment provided to the patients in the trials included bronchodilator nebulisation, systemic glucocorticoids, antibiotics and oxygen therapy. Number of participants in the trials ranged from 20 to 172 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Details and characteristics of the included studies in this meta-analysis

| Author (Year) | Setting | Patient population | Number of participants | Intervention (blinding) | Outcomes assessed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwards et al.[9] (2013) | Emergency department of two centres in New Zealand | Age ≥35 years, FEV1/FVC <70% & FEV1 ≤50% predicted 20 min after initial treatment with 2.5 mg salbutamol & 500 mg ipratropium bromide | Magnesium: 52 (48 analysed) Control: 64 (61 analysed) | Nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg with either 2.5 ml isotonic MgSO4 or placebo (NS), three times at 30 min intervals (Double blinded) | Primary: FEV1 at 90 min Secondary: FEV1 At 30 & 60 min, need for NIV/IV, hospital admission, ICU admission | No difference in FEV1 at 90 min No difference in FEV1 At 30 & 60 min, need for NIV/IV, hospital admission, and ICU admission. |

| Cömert et al.[11] (2016) | Outpatient clinic, single centre in Turkey | Age not mentioned, patients with infective COPD exacerbation | Magnesium: 10 Control: 10 | Nebulised ipratropium bromide 500 mcg with either 2.5 ml isotonic MgSO4 or placebo (NS), every 6 hours for 2 days (Double blinded) | Primary: FEV1 at 24 & 48 hr Secondary: PEFR at 10, 30, 60 & 120 min after each nebulisation, dyspnoea score, PaCO2 levels, need for NIV/IV, length of hospital stay, serum Mg level. | No difference in FEV1 at 24 & 48 hr Greater improvement in PEFR at 10 & 30 min, lower dyspnoea score at 24 in magnesium group. No difference in PaCO2 levels, need of NIV/IV, or length of hospital stay, higher serum Mg in magnesium group. |

| Bajracharya et al.[13] (2021) | Emergency department, single centre in Nepal | Age >40 years, AECOPD with PEFR <300 L/min 20 min after initial treatment with nebulised salbutamol 5 mg, ipratropium bromide 250 mcg & intravenous hydrocortisone 200 mg | Magnesium: 86 Control: 86 | Nebulised salbutamol 5 mg with either 3 ml isotonic MgSO4 or placebo (NS), three times at 30 min intervals (Single blinded) | Primary: PEFR at 30, 60 & 90 min Secondary: Need for NIV/V, ICU admission, mortality. | Higher PEFR at 30 min in magnesium group No difference in need for NIV/IV, ICU admission or mortality. |

| Ur Rehman Bhatti et al.[12] (2021) | Department of medicine, single centre in Pakistan | Age >40 years, AECOPD with PEFR <300 L/min 20 min after nebulised salbutamol 5 mg, ipratropium bromide 250 mcg & intravenous hydrocortisone 200 mg | Magnesium: 66 Control: 66 | Nebulised salbutamol 5 mg with either 3 ml isotonic MgSO4 or placebo (NS), three times at 30 min intervals (Single blinded) | Primary: PEFR at 30, 60 & 90 min Secondary: Need for NIV/V, ICU admission, mortality. | Higher PEFR at 30 min in magnesium group No difference in need for NIV/IV, ICU admission or mortality. |

AECOPD=Acute exacerbation of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NS=normal saline, FEV1=forced expiratory volume at 1 minute, PEFR=peak expiratory flow rate, NIV/IV=non-invasive or invasive ventilation, PaCO2=partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood

The included studies in this review were randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Three of the studies were performed on patients with AECOPD presenting to the emergency department.[9,12,13] One study was performed on hospitalised patients with a diagnosis of AECOPD.[11] In three of the studies, the dose was 2.5–3 ml of isotonic magnesium sulphate nebulised every 30 minutes for three doses (0, 30, 60 minutes).[9,12,13] In one study, 2.5 ml of isotonic magnesium sulphate was nebulised every 6 hours (4 doses a day) for 2 days.[11] In the control groups, an equivalent volume of normal saline nebulisation was administered as a placebo. In three of the studies, patients received initial treatment with nebulised salbutamol, nebulised ipratropium bromide, and intravenous corticosteroid prior to enrolment.[9,12,13] Only those patients with persistent expiratory flow limitation (Edwards 2013 – FEV1 <50% predicted; Bajracharya 2021, Ur Rehman Bhatti 2021 – PEFR <300 L/min) 20 minutes after initial treatment were enrolled in these studies.[9,12,13] In one study, initial treatment was given with intravenous methylprednisolone and antibiotics.[11] Co-treatment was in the form of nebulised salbutamol (2.5 mg) with each dose of magnesium sulphate in three studies,[9,12,13] and nebulised ipratropium bromide (0.5 mg) in one study.[11]

Risk of bias for judgement for individual studies and domains has been performed. [Figure 2] Two studies did not specify the mode of randomisation.[11,12] Three of the included studies lacked formal allocation concealment,[11,12,13] while two of the studies were prone to detection bias due to lack of blinding of the outcome assessors.[12,13]

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary (green—low risk of bias, yellow—unclear risk of bias, red—high risk of bias)

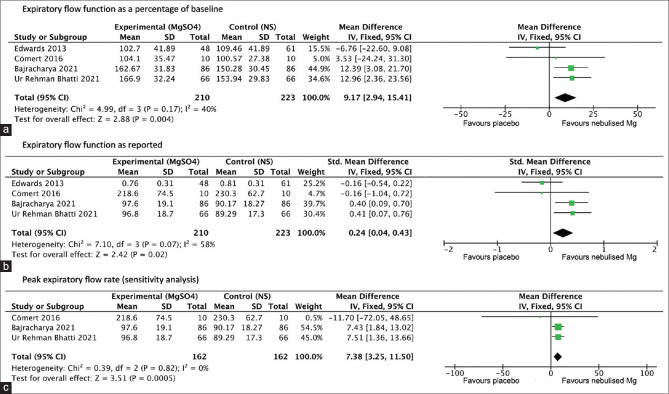

Expiratory flow function was reported as FEV1 in one study and as PEFR in the other three studies.[9,11,12,13] As previous studies have demonstrated a strong linear co-relation between FEV1 and PEFR of the order of Spearman co-efficient 0.75–0.83,[14,15] results from all four studies were combined using two different models—expiratory flow function as a percentage of baseline, and standardised mean difference. A sensitivity analysis was also performed after excluding the trial that reported expiratory flow function as FEV1,[9] only including those that reported PEFR.[11,12,13] Three of the studies reported expiratory flow function at baseline followed by 30, 60, and 90 minutes after initiation of intervention,[9,12,13] while one study recorded expiratory flow function at baseline followed by 10, 30, 60, and 120 minutes after each nebulisation.[11] As expiratory flow function at 60 minutes after initiation of intervention was common to all studies, this time point was chosen for pooled analysis of the effect of nebulised magnesium sulphate on expiratory flow function.

Need for hospitalisation from the emergency department depending on clinical status was reported in only one trial.[9] One trial was performed in already hospitalised patients.[11] In the two remaining trials, all patients were admitted to the hospital from the emergency department.[12,13]

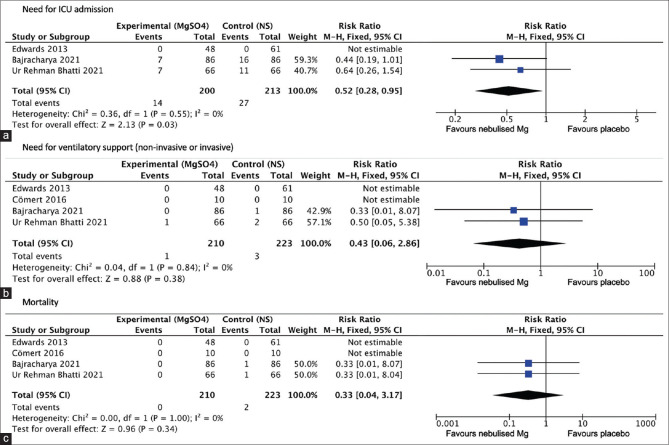

Requirement of ICU admission was reported in three of the four studies.[9,12,13] Results were combined to obtain a pooled relative risk. One study did not specify whether any of the participants needed ICU admission.[11]

Perceived dyspnoea score, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, and serum magnesium levels, reported in only one study (Cömert 2016), were compared between the arms at the end of the therapeutic intervention period (48 hours).[11] Incidence of reported adverse events attributed to the intervention was compared between the two groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Summary of different outcomes after using nebulized magnesium sulphate in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD

| Outcomes | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| With normal saline | Difference with nebulised MgSO4 | ||||

| Expiratory flow function as percentage of baseline | 433 (4 RCTs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderatea | - | The mean expiratory flow function as a percentage of baseline was 138.0% | MD 9.17% higher (2.94 higher to 15.41 higher) |

| Expiratory flow function as reported | 433 (4 RCTs) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa,b | - | - | SMD 0.24 higher (0.04 higher to 0.43 higher) |

| PEFR (sensitivity analysis) | 324 (3 RCTs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderatea | - | The mean PEFR (sensitivity analysis) was 98.5 L/min | MD 7.38 L/min higher (3.25 higher to 11.5 higher) |

| ICU admission | 413 (3 RCTs) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa,c | RR 0.52 (0.28-0.95) | 127 per 1,000 | 61 fewer per 1,000 (91 fewer to 6 fewer) |

| Need for ventilatory support | 433 (4 RCTs) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowd | RR 0.43 (0.06-2.86) | 13 per 1,000 | 8 fewer per 1,000 (13 fewer to 25 more) |

| Mortality | 433 (4 RCTs) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowd | RR 0.33 (0.04-3.17) | 9 per 1,000 | 6 fewer per 1,000 (9 fewer to 19 more) |

| Need for hospital admission | 109 (1 RCT) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderatee | RR 0.98 (0.86-1.10) | 918 per 1,000 | 18 fewer per 1,000 (129 fewer to 92 more) |

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. aBajracharya 2021 and Ur Rehman Bhatti 2021 were single-blinded studies and may have significant detection bias. bSubstantial heterogeneity present. I2 58%. cOIS for a 30% RRR from an expected incidence of 13% is nearly 2000. dOIS for a 30% RRR from an expected incidence of 1% is nearly 30000. eCI does not exclude clinically appreciable benefits or harm

Primary outcome

Pulmonary expiratory flow function

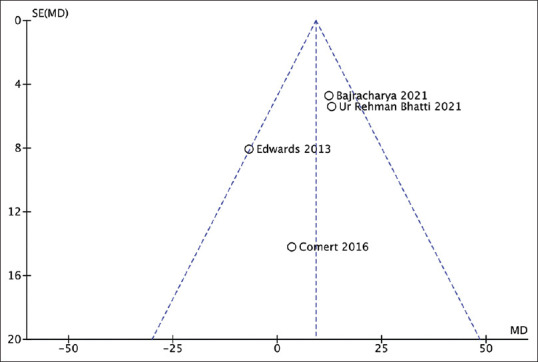

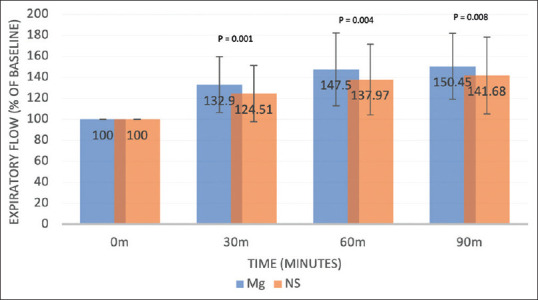

Combining results from all four studies (n = 433) revealed significantly better expiratory flow function (as a percentage of baseline) at 60 minutes in patients receiving nebulised magnesium sulphate compared to placebo (MD of magnesium vs placebo group 9.17%, 95% CI 2.94 to 15.41; moderate quality of evidence—Figure 3a). Heterogeneity was moderate and not statistically significant (I2 = 40%, P value 0.17). The funnel plot was symmetrical [Figure 4]. The difference in post-nebulization expiratory flow function was also significant when analysed in terms of standardised mean difference (SMD of magnesium vs placebo group 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.43; low quality of evidence—Figure 3b), with substantial but statistically insignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 58%, P value 0.07). The reason behind this heterogeneity may be the difference in the patient populations, the various risk factors among patients from developed and developing countries and the different pre-treatments the patients received in different studies. One study that reported expiratory flow function as FEV1 showed no significant difference at 90 minutes (MD of magnesium vs placebo group 0.026 L, 95% CI -0.15 to 0.095; the high quality of evidence).[9] Sensitivity analysis (n = 324) performed after excluding the study that reported expiratory flow function as FEV1 revealed significantly higher PEFR at 60 minutes in patients receiving nebulised magnesium sulphate compared to placebo (MD of magnesium vs placebo group 7.38 L/min, 95% CI 3.25 to 11.5; moderate quality of evidence—Figure 3c). Heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 0%, P value 0.82). [Figure 5]

Figure 3.

Forest plots: (a) Expiratory flow function as a percentage of baseline (b) Expiratory flow function as reported (c) Peak expiratory flow rate (sensitivity analysis) [NS = normal saline; SD = standard deviation; IV = inverse variance; CI = confidence intervals]

Figure 4.

Funnel plot: pulmonary expiratory flow function as a percentage of baseline [MD = mean difference; SE (MD) = standard error of mean difference]

Figure 5.

Progression of expiratory flow function with time (pooled weighted means from all 4 studies as a percentage of baseline flow; error bars denote proportional standard deviation; (P = 0.001 at 30 mins, P = 0.004 at 60 min, P = 0.008 at 90 min, two-sample t-test)

TSA revealed the cumulative Z-curve crossing the boundary for the benefit favouring nebulized MgSO4 [Figure 6]. Thus, although the RIS is 807 whereas our final sample size is 433 excluding drop-outs, as the z-curve has crossed the trial monitoring boundary for benefit, the RIS becomes inconsequential. A retrospective power analysis revealed a power of 82.4% with the achieved sample size.

Figure 6.

Trial sequential analysis of expiratory flow function as a percentage of baseline. The uppermost and lowermost curves represent trial sequential monitoring boundary lines for harm and benefit, respectively. Horizontal lines represent the traditional boundaries for statistical significance. Triangular lines represent the futility boundary. The cumulative Z curve represents the trial data

Secondary outcomes

Need for hospital admission

The one study that reported the need for hospital admission from the emergency department based on clinical status at the end of intervention showed no difference in admission rates (RR for magnesium vs placebo group 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.10; moderate quality of evidence).[9]

Need for ICU admission

Combining results from the three studies (Edwards 2013, Bajracharya 2021, Ur Rehman Bhatti 2021) that reported the need for ICU admissions revealed a significant reduction in the need for ICU admission (RR for magnesium vs placebo group 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.95; low quality of evidence—Figure 7a). Heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 0%, P value 0.55).[9,12,13]

Figure 7.

Forest plot—a meta-analysis of different qualitative outcomes : (a) Need for ICU admission (b)Need for ventilatory support (c) Mortality (NS = normal saline; SD = standard deviation; M-H = Mantel–Haenszel; CI = confidence intervals)

Need for ventilatory support (non-invasive or invasive)

Among the four studies, there was no significant difference in the need for ventilatory support between the 2 arms (RR for magnesium vs placebo group 0.43, 95% CI 0.06 to 2.86; low quality of evidence—Figure 7b). Heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 40%, P value 0.84).

Mortality

Among the four studies, there was no significant difference in mortality between the two arms (RR for magnesium vs placebo group 0.33, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.17; low quality of evidence—Figure 7c). Heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 0%, P value 1).

Other outcomes

The one study that reported perceived dyspnoea scale (VAS: visual analogue scale 0–100), arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide levels, and serum magnesium levels showed no significant difference in VAS scores (MD of magnesium vs placebo group -13.7, 95% CI -35.66 to 8.26; low quality of evidence), no significant difference in arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (MD of magnesium vs placebo group 3.8 mm Hg, 95% CI -3.72 to 11.32; moderate quality of evidence), but significantly higher serum magnesium levels in the magnesium group (MD of magnesium vs placebo group 0.10 mmol/L, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.17, P = 0.005; high quality of evidence) at the end of 48 hours.[11] No adverse events attributed to the therapeutic intervention were reported in any of the 4 studies.

Risk of bias for judgment for individual studies and domains has been performed. [Figure 2] Two studies did not specify the mode of randomization. Three of the included studies lacked formal allocation concealment, while two of the studies were prone to detection bias due to the lack of blinding of the outcome assessors.

DISCUSSION

Four studies randomly assigning 433 adult patients with AECOPD to receive either nebulised magnesium sulphate or placebo along with standard treatment, met the inclusion criteria. Two recently published trials provided a large portion of the total number of participants (304 out of 433).[12,13] Mean age of patients in all the studies was more than 60 years. The dose of isotonic magnesium sulphate used in each of the studies was approximately 2.5–3 ml (150–180 mg). The frequency of administration varied from three doses at 30 minutes intervals in three of the studies to once every 6 hours for 2 days in one study.[9,11,12,13]

The primary analysis, with pooled data from all four studies, showed that nebulised magnesium sulphate improved pulmonary expiratory flow function at 60 minutes after initiation of intervention compared to placebo. TSA showed that the meta-analysis had crossed the threshold of definite benefit.

Analysis of expiratory function in terms of standardised mean differences revealed a small but significant positive effect size. The effect remained consistent even when sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding the study the reported expiratory function as FEV1 (Edwards 2013) and including only those that measured PEFR.[9]

Among the secondary outcomes, nebulised magnesium sulphate reduced the need for ICU admission, amounting to 61 fewer ICU admissions per 1000 patients. No difference was noted in the need for hospital admission, need for ventilatory support or mortality. No adverse events attributable to the intervention were reported.

Evidence with respect to expiratory flow function was downgraded mainly due to the single-blinded nature of two of the studies which may have resulted in detection bias.[12,13] Evidence regarding the need for ICU admission, need for ventilatory support, and mortality, had to be downgraded as the total number of participants available for each analysis was inadequate compared to the predicted optimal information size.

Out of the four studies included in this review, two studies[12,13] showed improvement in expiratory flow function with nebulised magnesium sulphate while the remaining two studies showed no difference.[9,11] This difference in outcome may be attributed to several factors. The schedule of magnesium sulphate nebulisation was different in the study by Cömert et al.[11] compared to the other studies. The predominant aetiology of exacerbation may have been different in various studies. The studies that show the benefit of nebulised magnesium sulphate come from low-income counties with higher air and indoor pollution levels (Bajracharya 2021—Nepal,[13] Ur Rehman Bhatti 2021—Pakistan[12]) where the predominant cause of exacerbation may have been exposure pollutants.[16,17] In comparison, studies that show no benefit come from medium to high income countries (Edwards 2013—New Zealand,[9] Cömert 2016—Turkey[11]) where the predominant cause of exacerbation is infective.[18] Patients requiring non-invasive ventilation (NIV) support at presentation were excluded from all the studies. However, it is possible that due to the shortage of available resources, patients, who would have otherwise been offered NIV support and as a result excluded from the trials, are managed with conventional oxygen therapy in low-income countries. Thus, the severity of the disease may have been different across the studies. A clue to this disparity can be found in the striking difference in baseline PEFR values between the studies from low-income countries (Bajracharya 2021—60 L/m,[13] Ur Rehman Bhatti 2021—58 L/m[12]) and the study from Turkey (Cömert 2016—195 L/m).[11] The difference in equipment used to assess expiratory flow, and the difference in reported parameters, may have been confounding factors. In the study from New Zealand,[9] none of the patients in either group required ICU admission. This further raises the possibility that the included patients in this study were of lesser severity compared to patients included in the studies by Bajracharya et al. (8% ICU admission)[13] and Bhatti et al. (10.6% ICU admission).[12] On the other hand, this disparity in ICU admission rates could also be explained by differences in infrastructure available in the emergency departments and wards, and differences in ICU admission criteria.[19]

Our literature search revealed 1 systemic review with meta-analysis comparing use of nebulised magnesium sulphate vs. placebo in AECOPD.[5] The main outcomes analysed were hospital admissions, ICU admissions, and the need for ventilatory support. It included three of the studies included in the current review with a total of 301 participants.[9,11,13] The most recent study, by Ur Rehman Bhatti et al.,[12] had not been included in the earlier review. The outcomes explored were need for hospitalization, ICU admission and ventilatory support, dyspnoea grade, and mortality. However, unlike the present review, the earlier review did not assess the effect of nebulised magnesium sulphate on expiratory flow parameters. The meta-analysis concluded that nebulised magnesium may have little to no impact on hospital admission (very low certainty of the evidence) or need for ventilatory support (very low certainty of the evidence). It may reduce dyspnoea and the need for ICU admissions (very low certainty evidence). In concurrence with the previous review, the current review found no difference in the need for hospitalisation or ventilatory support. Also, in keeping with the previous review, the current review found lesser need for ICU admission with nebulised magnesium sulphate (low quality of evidence). Compared to the previous review, our confidence in the overall quality of evidence was improved due to the incorporation of a fourth trial in the review that increased overall sample size by 44%.[12] Unlike the present review that found improvement in expiratory flow function with nebulised magnesium sulphate, the previous review did not draw any conclusion regarding lung function outcomes due to limited evidence.

Our review had some limitations. We mainly focused on the assessment of the effect of nebulised magnesium sulphate on pulmonary expiratory flow function as all the included studies included were primarily powered for this outcome. As two different expiratory flow parameters (either FEV1 or PEFR) were reported in the studies, reasonable assumptions and conversions had to be made to perform a pooled analysis of the results. The fixed-effect model had to be used due to the low number of available studies. Most of the evidence generated in the review was of moderate to low quality owing mainly to deficiencies study design (single-blinded nature of two of the included studies) and small overall sample size with respect to the optimal information size (OIS) required for various secondary outcomes.

SUMMARY

This review provides moderate to low-quality evidence that nebulised magnesium sulphate as an adjunct to the standard treatment improves pulmonary expiratory flow function and reduces the need for ICU admission in patients with AECOPD, without any adverse effects. Evidence relating to other outcomes was limited. Future well-designed large-scale multi-centric trials are needed to definitively assess the benefit of nebulised magnesium sulphate in patients of AECOPD. Studies should clearly define and stratify baseline severity, and criteria for escalation of support. The dose and frequency of nebulisation should be standardised, as should be the spirometric parameters used to assess response.

This review and meta-analysis did not receive any external funding and the authors have no potential conflict of interest to declare.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.2022 GOLD Reports. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. [[Last accessed on 2022 Jul 08]]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2022-goldreports/

- 2.Magnesium Sulfate-an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [[Last accessed on 2022 Jul 08]]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/magnesium-sulfate .

- 3.Noppen M, Vanmaele L, Impens N, Schandevyl W. Bronchodilating effect of intravenous magnesium sulfate in acute severe bronchial asthma. Chest. 1990;97:373–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kew KM, Kirtchuk L, Michell CI. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating adults with acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010909. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010909.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni H, Aye SZ, Naing C. Magnesium sulfate for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013506. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013506.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coates AL, Leung K, Vecellio L, Schuh S. Testing of nebulizers for delivering magnesium sulfate to pediatric asthma patients in the emergency department. Respir Care. 2011;56:314–8. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Fixed or random effects meta-analysis?Common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13:196–207. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skorodin MS, Tenholder MF, Yetter B, Owen KA, Waller RF, Khandelwahl S, et al. Magnesium sulfate in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:496–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards L, Shirtcliffe P, Wadsworth K, Healy B, Jefferies S, Weatherall M, et al. Use of nebulised magnesium sulphate as an adjuvant in the treatment of acute exacerbations of COPD in adults:A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2013;68:338–43. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouira S, Bouida W, Grissa MH, Beltaief K, Trimech MN, Boubaker H, et al. Magnesium sulfate versus ipratropium bromide in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation:A randomized trial. Am J Ther. 2014;21:152–8. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182459a8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cömert Ş, Kıyan E, Okumuş G, Arseven O, Ece T, İşsever H. Efficiency of nebulised magnesium sulphate in infective exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Tuberk Toraks. 2016;64:17–26. doi: 10.5578/tt.9854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatti HU, Mushtaq Z, Arshad A, Khanum N, Joher I, Masood A. Nebulized Magnesium Sulphate vs Normal Saline as an Adjunct in Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2021;15:3694–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajracharya M, Acharya RP, Neupane RP, Sthapit R, Tamrakar AR. Nebulized magnesium sulphate versus saline as an adjuvant in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a tertiary centre of Nepal:A randomized control study. J Inst Med. 2021;43:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautrin D, Carlos D'Aquino L, Gagnon G, Malo J-L, Cartier A. Comparison between Peak Expiratory Flow Rates (PEFR) and FEV1 in the monitoring of asthmatic subjects at an outpatient clinic. Chest. 1994;106:1419–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.5.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pothirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, Liwsrisakun C, Bumroongkit C, Deesomchok A, et al. Peak expiratory flow rate as a surrogate for forced expiratory volume in 1 second in COPD severity classification in Thailand. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1213–8. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S85166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggappa DR, Rao GV, Kannan S. Anaesthesia for patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:574–83. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.165859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhome AB. COPD in India:Iceberg or volcano? J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:298–309. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.03.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burge S, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations:Definitions and classifications. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:46s–53s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00078002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matic I, Majeric-Kogler V, Šakic-Zdravcevic K, Jurjevic M, Mirkovic I, Hrgovic Z. Comparison of invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation for patients with COPD:Randomised prospective study. Indian J Anaesth. 2008;52:419–27. [Google Scholar]