SUMMARY

PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein-1) is a T cell-intrinsic checkpoint regulator of exhaustion with an unknown mechanism of action. Here, we show that PSGL-1 acts upstream of PD-1 and requires co-ligation with the T cell receptor (TCR) to attenuate activation of mouse and human CD8+ T cells and drive terminal T cell exhaustion. PSGL-1 directly restrains TCR signaling via Zap70 and maintains expression of the Zap70 inhibitor Sts-1. PSGL-1 deficiency empowers CD8+ T cells to respond to low-affinity TCR ligands and inhibit growth of PD-1-blockade-resistant melanoma by enabling tumor-infiltrating T cells to sustain an elevated metabolic gene signature supportive of increased glycolysis and glucose uptake to promote effector function. This outcome is coupled to an increased abundance of CD8+ T cell stem cell-like progenitors that maintain effector functions. Additionally, pharmacologic blockade of PSGL-1 curtails T cell exhaustion, indicating that PSGL-1 represents an immunotherapeutic target for PD-1-blockade-resistant tumors.

In brief

In this study, Hope et al. reveal intrinsic mechanisms through which the cell surface molecule PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein-1) modulates T cell responses and drives differentiation to terminal exhaustion in chronic virus infection and melanoma. Their study highlights the targetability of PSGL-1 as an emerging immune checkpoint blockade strategy.

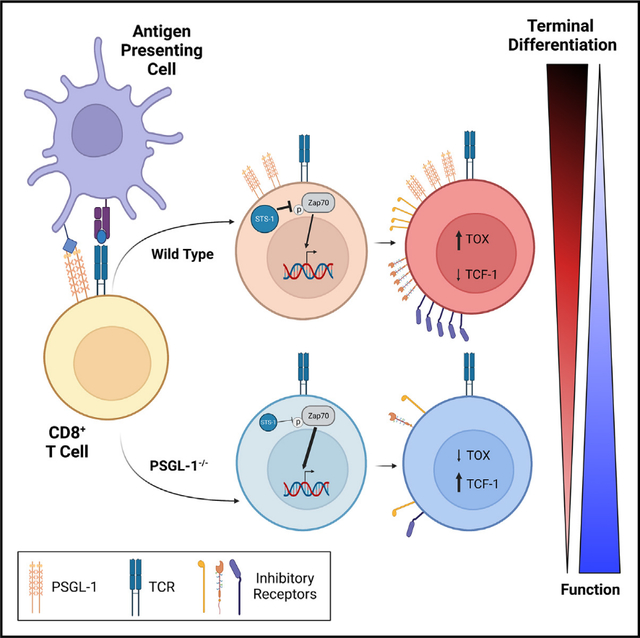

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

CD8+ effector T cells (TEFF) are vital in protecting against and clearing virally infected cells and tumor cells. However, in settings of chronic viral infection and cancer, multiple factors including sustained antigen exposure promote T cell exhaustion. Accompanied by progressive decline in effector functions and proliferative capacity, this state is linked to increased co-expression of multiple inhibitory receptors including PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG3, and TIM-3.1 The discovery of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) monoclonal antibody therapy to promote anti-tumor immunity by inhibiting CTLA-4 and/or PD-1 on T cells is one of most significant cancer therapeutic breakthroughs of the last decade, with efficacy shown across many cancers.2 Despite dramatic success in some patients, a significant population fails to respond to ICB. It is therefore essential to identify novel mechanisms regulating the differentiation of exhausted T cells (TEX) that could expand ICB’s applicability to more patients. In particular, it will be critical to develop ICB strategies that support the development and maintenance of stem cell-like (TSC) or progenitor TEX (TPEX) that retain the capacity for proliferation and TEFF function.3

PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1) is expressed on most hematopoietic cells, including T cells.4,5 We identified that genetic deletion of PSGL-1 prevented development of TEX and supported viral clearance in the chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) clone 13 (Cl13) model6 due to increased TEFF function that was accompanied by decreased inhibitory receptor expression. PSGL-1 deficiency also supported growth control of a PD-1-blockade-resistant melanoma tumor.6 Furthermore, PSGL-1 deficiency with acute LCMV Armstrong infection promoted greater TEFF and memory progenitor T cell formation,7 underscoring the fundamental role PSGL-1 plays as a regulator of T cell responses. In this study, we investigated cellular and molecular mechanisms by which PSGL-1 signaling intrinsically regulates TEX differentiation including the impact of PSGL-1 on T cell receptor (TCR) signaling, glycolysis, and the promotion of TSC and TPEX. We demonstrate herein that PSGL-1 ligation concomitant with TCR ligation drives TEX differentiation in human and mouse CD8+ T cells. Critically, we show that blockade of PSGL-1 recapitulates PSGL-1 deficiency in antitumor and antiviral responses, and its distinct mechanism of T cell inhibition underscores the translational potential of targeting PSGL-1 by ICB.

RESULTS

PSGL-1 restrains TCR signaling magnitude and duration

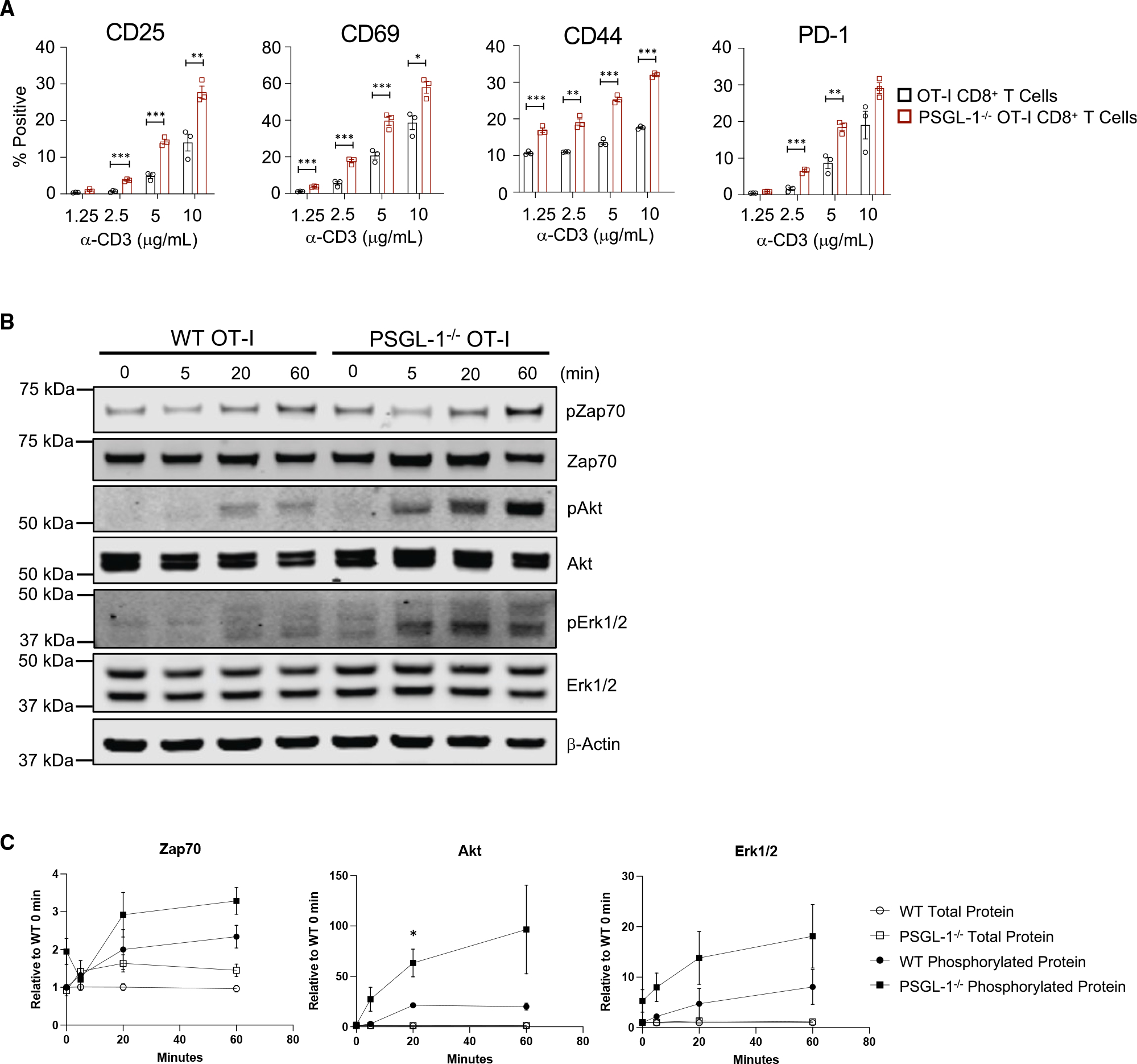

Since PSGL-1 deficiency enhanced TEFF responses, we addressed whether PSGL-1 modulates CD8+ T cell responses to TCR engagement. TCR stimulation of naive wild-type (WT) and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells showed that PSGL-1 deficiency enabled higher expression of the T cell activation markers CD25, CD69, CD44, and PD-1 (Figure 1A)8–11 and greater functionality (Figure S1A). To directly evaluate TCR signaling, we assessed phosphorylation of Zap70, Erk1/2, and Akt by western blot (Figure 1B) and found greater activation of each of these signaling molecules in PSGL-1−/− T cells (Figure S1B), with the greatest effect on pAkt levels in PSGL-1−/− compared with WT T cells (Figure 1C), demonstrating that PSGL-1 expression inherently limits T cell activation from the time of initial TCR engagement.

Figure 1. PSGL-1 restrains TCR signaling.

(A) Frequencies of OT-I WT and PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells expressing activation markers at 18 h stimulation with anti-CD3ε antibody. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Experiments were performed 2×.

(B) Western blot of phosphorylated and total levels of Zap70, Erk1/2, AKT, and GAPDH in WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells stimulated for the indicated time with anti-CD3ε antibody.

(C) Relative levels of phosphorylated Zap70, Erk1/2, and AKT, normalized to β-actin and relative to the specific protein of interest value in WT samples at 0 min for each blot.

Experiments were performed 3×, 3 mice pooled/genotype, per experiment. (A–C) All data are parametric data except pAkt at 5 min. For parametric data, unpaired t tests were performed; Mann-Whitney test used for non-parametric data. Error bars are SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

See also Figure S1.

To address intrinsic TCR signaling regulation by PSGL-1 under conditions of T cell exhaustion, we used an in vitro model12 comparing OT-I in vitro TEFF (iTEFF) with OT-I in vitro TEX (iTEX). Since PSGL-1 deficiency enabled responsiveness to lower levels of TCR stimulation, we hypothesized that PSGL-1 deficiency may increase TCR sensitivity to lower-affinity ligands. iTEX and rested iTEFF were generated with the SIINFEKL ovalbumin (OVA)(257–264) peptide (N4) or with the lower OT-I TCR affinity variants13 SIIQFEKL (Q4), SIITFEKL (T4), or SIIVFEKL (V4), and we evaluated early CD8+ T cell activation by assessing CD69,8 CD25,14 and CD4411 expression. 18 h after peptide stimulation (Figure 2A), similar levels of CD69 were observed between WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells activated by N4, Q4, and T4, while significantly more CD69 was observed in PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells activated by V4. Significantly more CD25 and CD44 were observed in PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells under all conditions (Figures 2B and 2C).

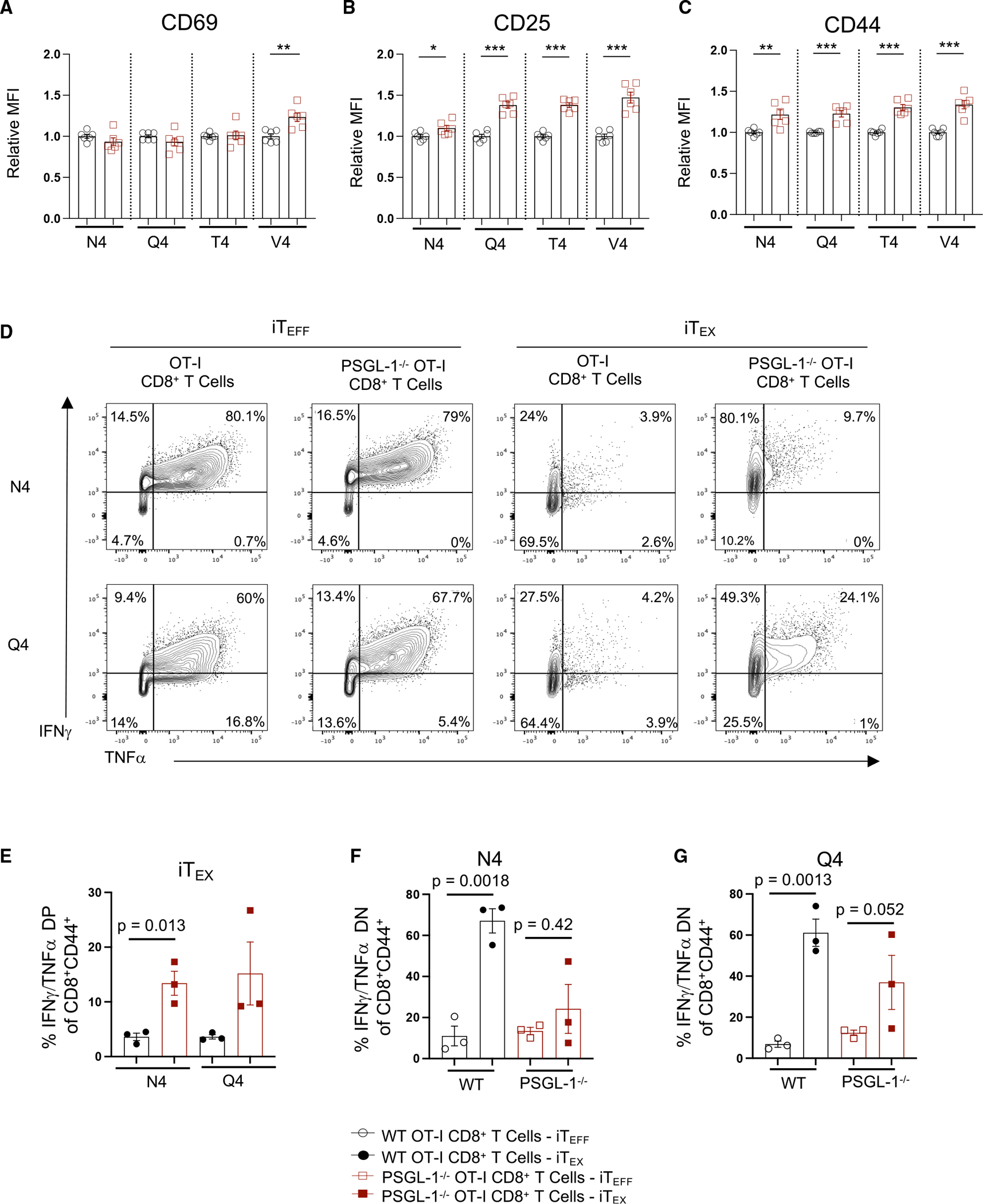

Figure 2. PSGL-1 deficiency promotes increased TCR signaling sensitivity.

WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells were stimulated with ovalbumin (OVA) peptide-pulsed activated splenocytes.

(A–C) Expression of (A) CD69, (B) CD25, and (C) CD44 was assessed by flow cytometry. OVA peptides of varying TCR affinities were used for stimulation: N4 (SIINFEKL), Q4 (SIIQFEKL), T4 (SIITFEKL), or V4 (SIIVFEKL).

(D–F) WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells were cultured under effector (single stimulation; iTEFF) or exhaustion conditions (repeated stimulation; iTEX) with N4, Q4, T4, or V4 OVA peptides.

(D) Flow cytometry plots of IFNγ and TNF-α production by cultured WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells restimulated on day 5 with SIINFEKL for 5 h.

(E) Frequency of double-positive IFNγ- and TNF-α-producing OT-I cells from WT (black circles) or PSGL-1−/− mice (red squares) following iTEX culture with either SIINFEKL or SIIQFEKL peptide.

(F) Frequency of double-negative (non-IFNγ- or -TNF-α-producing) OT-I cells from WT or PSGL-1−/− mice following iTEFF (open symbols) or iTEX (closed symbols) culture with N4 peptide.

(G) Frequency of double-negative (non-IFNγ- or TNFα-producing) OT-I cells from WT or PSGL-1−/− mice following iTEFF (open symbols) or iTEX (closed symbols) culture with Q4 peptide.

(A–F) Each dot represents an individual experiment from a pooling of 1–2 mice/genotype/experiment, experiments were performed 3×. Data are parametric; unpaired t tests were performed. Error bars are SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

We also assessed T cell function in WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I iTEFF and iTEX generated with the N4 or Q4 peptides (Figure 2C). WT and PSGL-1−/− iTEFF generated with either peptide had comparable frequencies of interferon γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) cytokine-producing cells, and most were double producers. As expected, WT iTEX generated with these peptides were highly exhausted, with few cytokine producers (Figures 2D and 2E). However, PSGL-1−/− iTEX elicited with N4 showed increased co-production of IFNγ and TNF-α (4.2-fold) (Figures 2D and 2E) compared with WT iTEX, with fewer non-cytokine-producing cells overall (Figure 2F). Notably, PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells induced with the lower affinity Q4 retained an increased capacity for cytokine co-production (Figures 2D and 2F) with a 3.8-fold increase over WT iTEX. These results show that PSGL-1 restrains early T cell activation. Further, with iTEX conditions, PSGL-1 limits responses to lower levels of TCR signals and lower-affinity antigens, which would be detrimental to T cell responses, particularly in the context of lower-affinity tumor cell antigens.

To further interrogate PSGL-1-mediated regulation of TCR signaling, we performed total and phospho-proteomics analysis of naive and stimulated WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells. Relative expression levels of 7,014 total and 9,294 phosphorylated proteins were evaluated. After activation, 576 phosphorylated proteins were significantly differentially expressed between WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (Figure S2A). Pathway analysis identified 22 significantly enriched pathways, including “T cell receptor signaling” (Figure S2B). Phosphorylation of several proteins associated with regulation of T cell signaling was significantly upregulated in PSGL-1−/− T cells (Figure S2C). Also notable were changes in proteins regulating proliferation and survival (Figure S2D), calcium signaling, and metabolism (Figure S2E). Gene set enrichment analysis confirmed greater activation of the ERK1/2 pathway in PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (Figure S2F). These data indicate that PSGL-1 signals play a critical role in regulating the T cell response to TCR engagement. Importantly, few changes were observed in total protein expression in naive WT cells compared with naive PSGL-1−/− cells (30 up, 14 down). Of the 576 differentially expressed phosphoproteins, only 127 were similarly differentially expressed in naive cells.

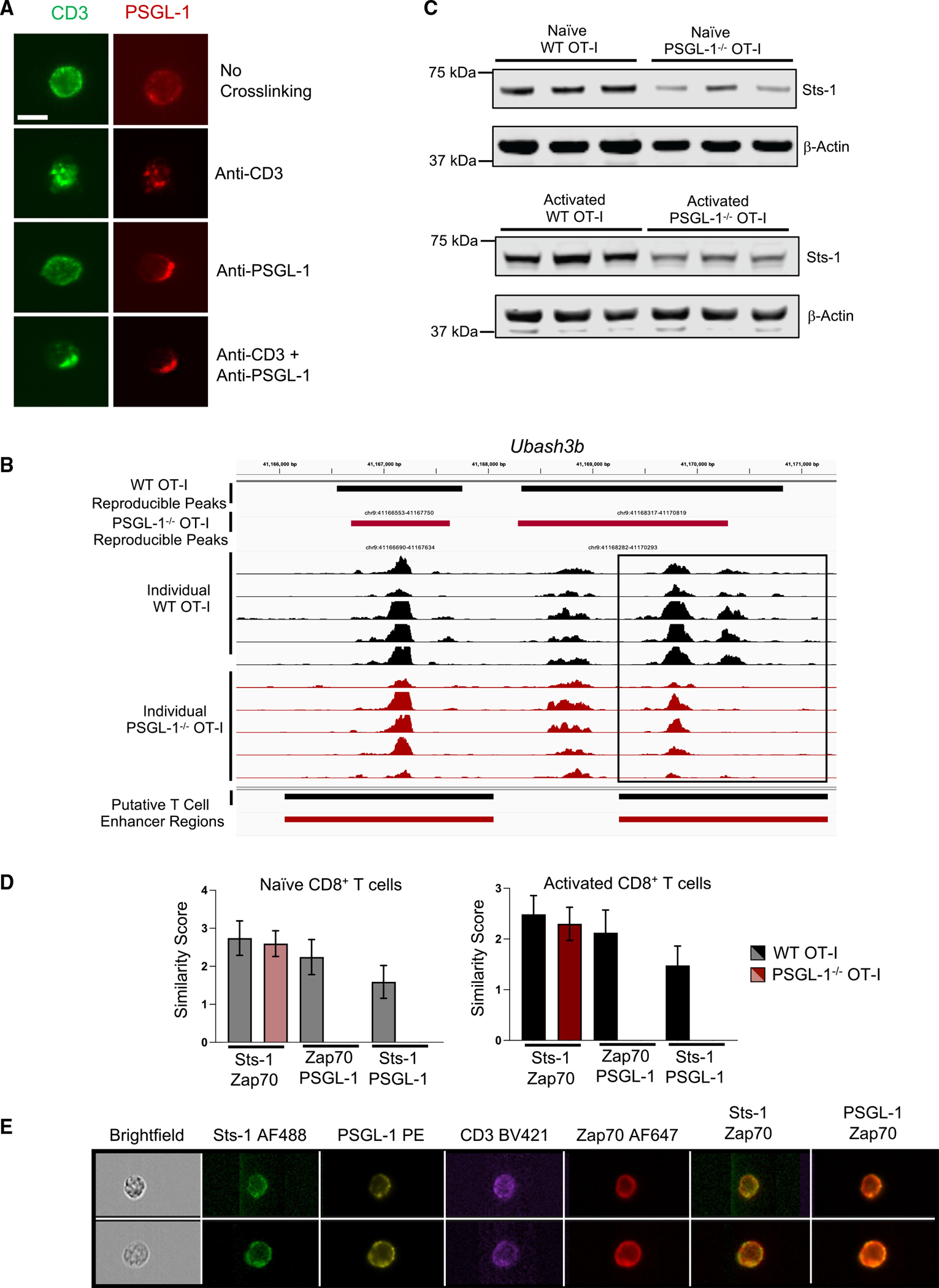

Previous studies of T cells showed that PSGL-1, a large, glycosylated protein, migrates to the uropod that forms at the back of cells during polarized movement.15 PSGL-1 was therefore hypothesized to be outside the region of TCR/peptide contact. To address the spatial relationship of the TCR complex and PSGL-1, we analyzed their distribution by microscopy. Without crosslinking of TCR (CD3) or PSGL-1, both molecules were evenly distributed over the cell (Figure 3A). Upon TCR ligation, CD3 formed punctate staining indicative of clustering and co-clustered with PSGL-1. However, upon ligation with anti-PSGL-1 alone, PSGL-1 clustered to one side of the T cell, while CD3 remained dispersed. When both CD3 and PSGL-1 were ligated simultaneously, they co-localized and migrated to one region of the cell. Co-localization of CD3 and PSGL-1 on primary CD8+ T cells was quantified by analysis of 10,000 CD8+ T cells via imaging flow cytometry. This approach confirmed that co-localization of CD3 and PSGL-1 was greatest following co-ligation of both molecules (Figures S3A–S3C; similarity score, 2.4 ± 0.3 median absolute deviation [MAD]), showing that PSGL-1 is optimally positioned to directly regulate TCR signals, particularly when PSGL-1 is concomitantly engaged.

Figure 3. PSGL-1 co-localizes with the TCR, Zap70, and the Zap70 inhibitor Sts-1.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining (40× magnification, scale bar of 10 μm) of CD3 (green) and PSGL-1 (red) on CD8+ TK-1 cells before or after crosslinking with CD3 and/or PSGL-1 antibodies. Experiments were performed 2×.

(B) Chromatin accessibility within the Ubash3b gene region in WT OT-I cells (black) or PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (red). Biological replicates prepared from 2 separate experiments.

(C) Western blot of Sts-1 and β-actin expression in naive (top) or 2 day activated (bottom) WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells. Each band is a biologic replicate. Experiments were performed 2×.

(D and E) Imaging flow cytometry analysis of Sts-1, PSGL-1, CD3, and Zap70 localization and co-localization in 10,000 naive and activated WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells.

(D) Similarity scores of Sts-1, Zap70, and PSGL-1 expression in naive (left) or 20 min activated (right) WT (gray/black) and PSGL-1−/− (light red, red) OT-I cells. Error bars are median absolute deviation (MAD).

(E) Representative images from (D) in two WT OT-I CD8+ T cells.

We previously analyzed GP(33–41) LCMV Cl13 virus-specific CD8+ T cells from WT and PSGL-1−/− mice by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) 8 days post infection (dpi).6 Reanalysis of these data identified the significant downregulation of the gene Ubash3b (3.25-fold change, p ≤ 0.05) in PSGL-1−/− T cells (GEO: GSE80113). Ubash3b encodes the protein Sts-1 (suppressor of T cell signaling-1), a phosphatase shown to be a potent negative regulator of TCR signaling by inhibiting Zap70.16,17 Ubash3b expression is increased in CD8+ TEFF compared with naive cells (ImmGen RNA-seq dataset), suggesting that Sts-1 levels may limit the extent of T cell activation to prevent hyperresponsiveness.16 What regulates Sts-1 expression in T cells has yet to be established. Since PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells demonstrated increased TCR signaling, we hypothesized that the epigenetic landscape would reflect this enhanced state of activation. ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing) tracings identified an enhancer region within Ubash3b with significantly less open chromatin in PSGL-1−/− T cells compared with WT T cells after TCR stimulation (Figures 3B and S3D–S3G). Protein analysis confirmed that naive and activated PSGL-1−/− OT-I T cells express less Sts-1 (Figures 3C and S3H). Imaging flow cytometry identified a high correlation in localization of Sts-1 and Zap70 in naive and activated WT and PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells, as well as between PSGL-1 and Zap70 (Figures 3D and 3E). Together, these data suggest that greater availability and activation of Zap70 (pZap70) may be in part due to decreased levels of Sts-1 leading to enhanced TCR signaling in PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells.

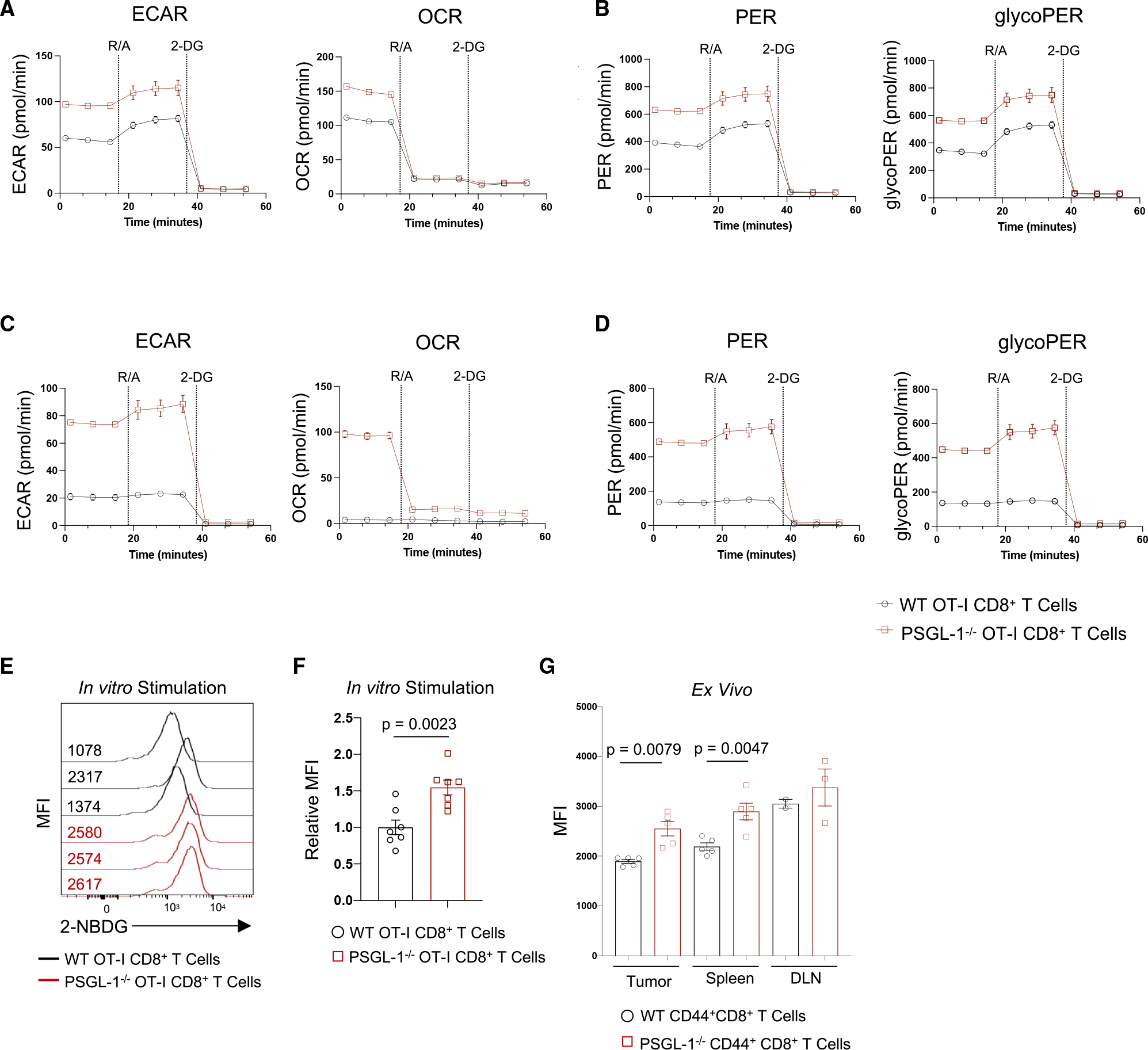

PSGL-1 restrains glycolysis in CD8+ T cells

Given the inhibitory effects of PSGL-1 on CD8+ T cell activation, we addressed its impact on glycolytic metabolism, which underlies TEFF development after TCR engagement.18 Using the Seahorse Glycolytic Rate Assay, glycolysis was assessed in WT or PSGL-1−/− OT-I T cells after activation for 3 days (Figures 4A and 4B). Both baseline and maximal glycolysis levels were significantly elevated in PSGL-1−/− T cells. Thus, we hypothesized that PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells retain glycolytic activity under exhaustion conditions. To test this, we assessed glycolysis in in vitro-generated PSGL-1−/− and WT OT-I iTEX. As expected, exhausted WT OT-I iTEX have low levels of extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) at baseline and upon mitochondrial uncoupling (Figure 4C). Comparatively, PSGL-1−/− OT-I iTEX retained high levels of ECAR and OCR (Figure 4C), corresponding to higher levels of proton efflux rate (PER) and glycolic PER (glycoPER) than WT OT-I iTEX (Figure 4D). The results show that PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells remain more glycolytically active under conditions of chronic TCR stimulation.

Figure 4. PSGL-1 restrains glycolysis in CD8+ T cells.

(A) Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) were assessed using the Seahorse Glycolytic Rate Assay in 3 day activated WT or PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells.

(B) Proton efflux rates (PERs) and glycolytic PER (glycoPER) calculated based on (A).

(C) ECAR and OCR were assessed for iTEX OT-I cells or PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells on day 5.

(D) PER and glycoPER calculated based on (C).

(A)–(D) are representative of >3 experiments.

(E and F) Histograms (E) and graph (F) of 2-NBDG uptake in OT-I or PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells after 2 h stimulation with SIINFEKL peptide; each line/dot represents an individual mouse. Data are normally distributed.

(G) Graph of ex vivo 2-NBDG MFI values in CD44+CD8+ T cells from tumors, spleens, or tumor draining lymph nodes (DLNs) of WT or PSGL-1−/− mice bearing YUMM1.5 tumors.

Data in (D) and (G) are parametric except for WT tumors and DLN. For parametric data, unpaired t tests were performed; Mann-Whitney test used for non-parametric data. Error bars are SEM. Each dot in tumors and spleens represents an individual mouse; DLN represents a pool. Experiments were performed 2×.

We confirmed that increased glycolysis of PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells was accompanied by greater glucose utilization by quantifying 2-NBD glucose analog (2-NBDG) uptake by WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells after stimulation with OVA257–264 (Figures 4E and 4F). No differences in glucose uptake by naive WT or PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells were observed. We reported that PSGL-1−/− mice exhibit significant control of the PD-1-blockade-resistant YUMM1.5 melanoma tumor line,6 which does not express PSGL-1 (Figure S4). To assess whether differences in glucose uptake could contribute to an enhanced anti-tumor response, we assessed 2-NBDG uptake by activated (CD44hi) CD8+ T cells from YUMM1.5-bearing mice. In CD44hi CD8+ T cells from YUMM1.5 tumors, spleens, and tumor draining lymph nodes (DLNs) assessed immediately ex vivo, we observed significantly greater glucose uptake by PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells compared with WT CD8+ T cells (Figure 4G). The data show that PSGL-1−/− CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) maintain a greater capacity for glucose uptake and enhanced glycolytic capabilities under exhaustive conditions.

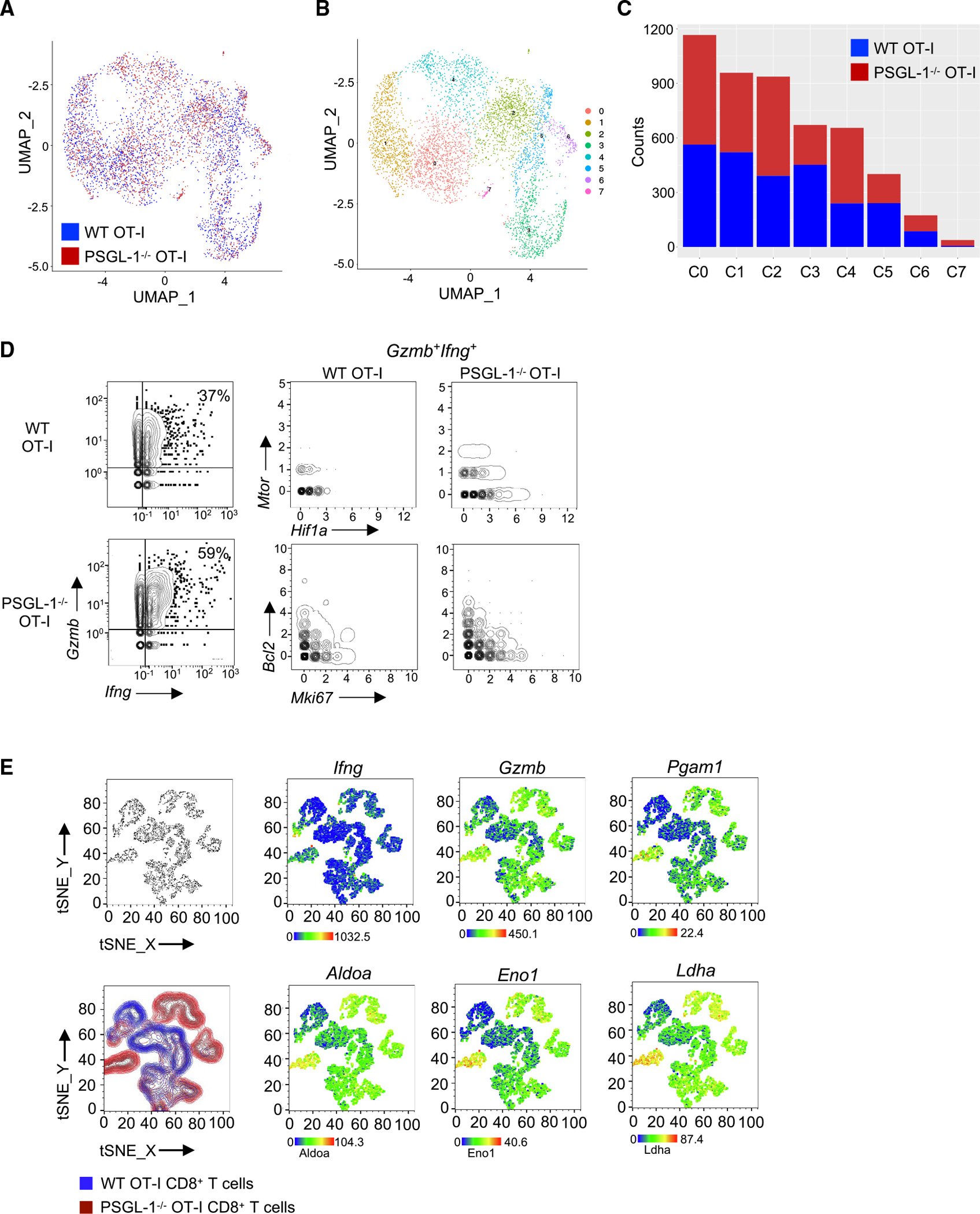

scRNA-seq reveals an enhanced metabolic state of PSGL-1-deficient CD8+ TILs

Adoptively transferred PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells enable greater control of B16-OVA melanoma in mice than WT OT-I cells.6 To assess intrinsic transcriptional differences between WT and PSGL-1−/− T cells in vivo, we used single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) and the B16-OVA model with adoptive transfer of WT or PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (Figure S5A). To account for an uneven capture rate, data were down-sampled to an equal number of cells for analysis. Unbiased clustering of donor OT-I cells revealed a high level of overlap between WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (Figures 5A–5C). We identified genes that were globally differentially expressed in PSGL-1−/− cells (e.g., Rpl35, Tmsb10) as well as cluster-specific gene alterations (e.g., Hist1h2ap, H2afv, Malat1) (Figure S5B). Overall, more PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells expressed genes associated with CD8+ TEFF (Ifng, Gzma, Gzmb, Gzmc, Tbx21) compared with WT cells (Figure S5C). We evaluated T cell functionality on a per-cluster basis (Figure S5D). Overall, more PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells expressed Ifng across the clusters, with significantly greater levels in clusters 0, 1, 2, and 4. Differences in GzmA were found in clusters 3, 4, and 5, while Gzmb expression was largely comparable across all clusters. Using SeqGeq to “gate” and evaluate gene expression within subsets, we identified OT-I cells co-expressing granzyme B (Gzmb) and IFNγ (Ifng). In PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells, co-expression of Gzmb and Ifng was linked to greater expression of Mtor and Hif1a as well as engagement in cell cycle (Mki67) but without changes in cell survival (Bcl2) (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Single-cell sequencing reveals enhanced metabolic state of intratumoral PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells.

1 × 106 activated WT OT-I (CD45.1+) or PSGL-1−/− OT-I (CD90.1+) T cells were injected into C57BL/6 mice 7 days after B16-OVA injection, and donor OT-I cells were sorted from tumors 6 days later for single-cell RNA sequencing.

(A) UMAP analysis (Seurat) of TILs.

(B and C) Composition analysis showing the breakdown of WT OT-I cells (pink) vs. PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (green) overlaying the UMAP (B) and the number of counts of each per cluster (C).

(D) SeqGeq analysis of Gzmb and Ifng expression in WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (left). Top right: gene expression of Mtor and Hif1a in Gzmb+Ifng+ WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells. Bottom right: gene expression of Bcl2 and Mki67 in Gzmb+Ifng+ WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells.

(E) SeqGeq tSNE clustering of WT (blue) and PSGL-1−/− (red) OT-I cell libraries. Gene expression overlays of Ifng, Gzmb, Pgam1, Aldoa, Eno1, and Ldha in 1,000 single cells per condition from 6 mice per genotype.

See also Figure S5.

As we identified greater glycolytic capacity with PSGL-1 deficiency in OT-I cells, we assessed expression of genes that regulate glycolysis in WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells by overlaying gene expression on a SeqGeq-generated t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plot (Figure 5E). Individual Ifng and Gzmb expression was largely localized in PSGL-1−/− OT-I T cell clusters. Furthermore, greater expression of the genes Pgam1, Aldoa, Eno1, and Ldha, which regulate glycolysis, was co-localized with these TEFF PSGL-1−/− OT-I T cells. These analyses underscore that PSGL-1 deficiency confers greater glycolytic capacity in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and that this greater metabolic capacity is linked to greater TEFF function. Thus, PSGL-1 deficiency releases metabolic constraints that are essential for efficient CD8+ T cell effector function in the TME.

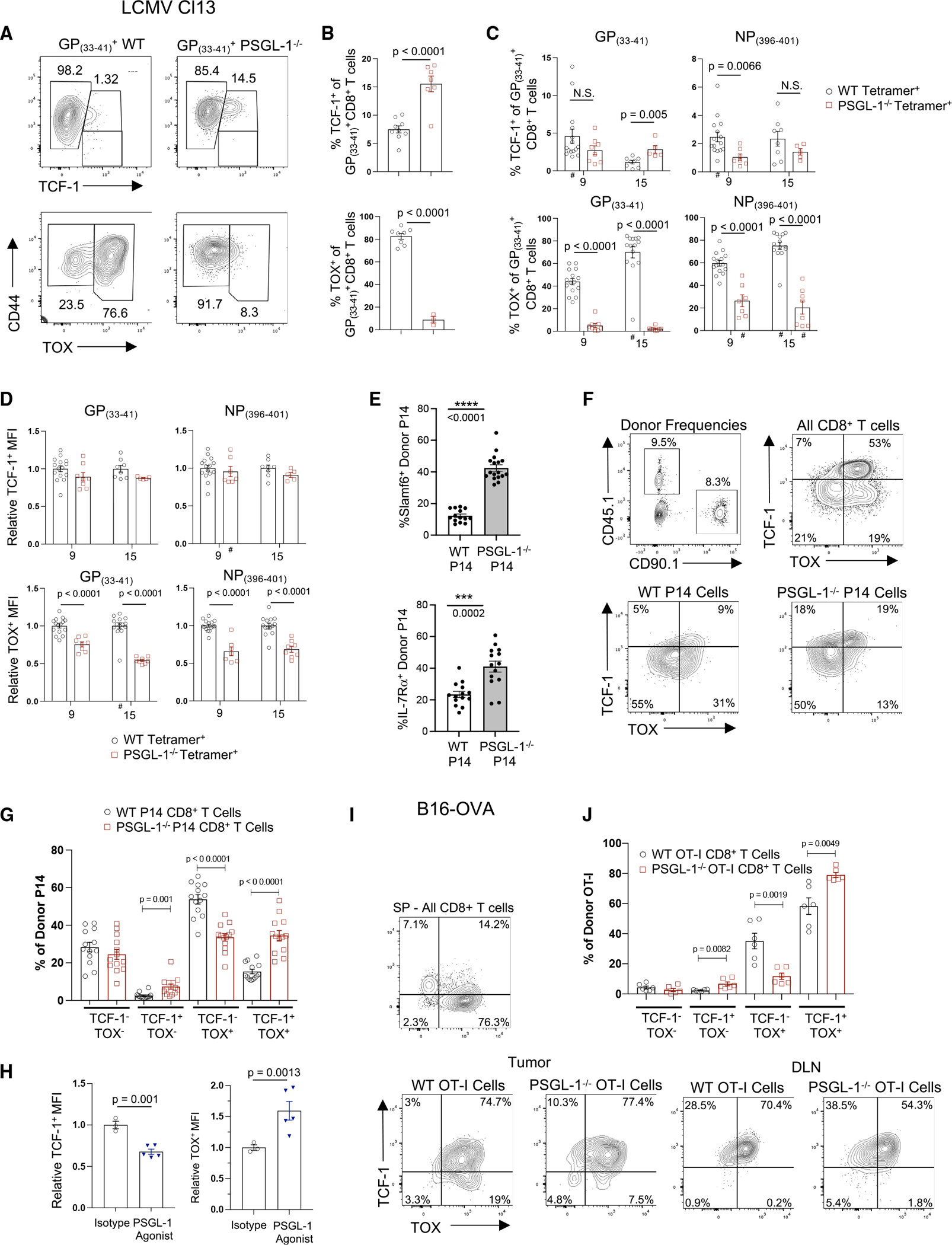

PSGL-1 suppresses persistence of TSC/TPEX

Many studies have now defined that TSC with a capacity for self-renewal, expansion, and development of effector function express the transcription factor TCF-1.19–21 In metastatic melanoma, TCF-1+CD8+ T cells from patient tumors are associated with objective responses to PD-1 blockade.22 Conversely, the transcription factor TOX is a fundamental regulator of a T cell’s fate of irreversible exhaustion.23–26 However, co-expression of TOX and TCF-1 can distinguish less terminally differentiated TEX that retain effector function.24,26 To address if enhanced functionality of PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells was a result of altered differentiation, we assessed TCF-1 and TOX expression in WT and PSGL-1−/− GP(33–41)+ virus-specific T cells from spleens at 15 dpi (Figures 6A and 6B), when the virus is cleared from the sera of PSGL-1−/− mice.6 TCF-1+ cells were increased in PSGL-1−/− mice compared with WT mice; conversely, a large fraction of WT T cells expressed TOX compared with PSGL-1−/− T cells. In virus-specific GP(33–41)+ and NP(396–404)+ T cells in the blood at 9 dpi of WT and PSGL-1−/− mice when the virus loads are comparable, the frequencies of TCF-1+ cells were indistinguishable; the majority of virus-specific CD8+ T cells lacked expression of both TCF-1 and TOX (Figure S6A). However, dramatically fewer GP(33–41)+ T cells from PSGL-1−/− mice expressed TOX (Figure 6C). At 15 dpi, the phenotype of GP(33–41)+ T cells from PSGL-1−/− mice showed a moderate increase in TCF-1+ cells but a drastic decrease in TOX+ cells (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. PSGL-1 limits TCF-1 and promotes TOX expression in CD8+ T cells during chronic virus infection and cancer.

(A) TCF-1 or TOX vs. CD44 expression in GP(33–41)-specific CD8+ T cells from spleens of WT or PSGL-1−/− mice 15 dpi with LCMV Cl13.

(B) Frequencies of TCF-1+ (top) or TOX+ (bottom) GP(33–41)+ CD8+ T cells in spleens of WT or PSGL-1−/− mice 15 dpi.

(C) Frequencies of TCF-1+ (top) or TOX+ (bottom) GP(33–41)+ or NP(396–404)+ CD8+ T cells in blood of WT or PSGL-1−/− mice on 9 and 15 dpi.

(D) The relative per-cell expression (MFI) of TCF-1+ (top) or TOX+ (bottom) GP(33–41)+ or NP(396–404)+ CD8+ T cells in blood of WT or PSGL-1−/− mice on 9 and 15 dpi.

(E) WT mice received a 1:1 mix of WT and PSGL-1−/− CD8+ P14 cells and infected with LCMV Cl13. Slamf6 and IL-7Rα expression on donor T cells in blood was assessed 60 dpi.

(F) Frequency of donor WT P14 and PSGL-1−/− P14 T cells within CD8+ T cells in blood on 60 dpi (top left). TCF-1 and TOX staining in CD8+ T cells (top right), WT P14 cells (bottom left), and PSGL-1−/− P14 cells (bottom right).

(G) Frequency of donor P14 cells expressing combinations of TCF-1 and TOX.

(H) Relative per-cell expression (MFI) of TCF-1+ (top) or TOX+ (bottom) GP(33–41)+ or NP(396–404)+ CD8+ T cells in spleens 15 dpi with LCMV Cl13 following in vivo ligation of PSGL-1 or isotype control antibody.

(I and J) TCF-1 and TOX expression in CD44hi donor OT-I cells in tumors and inguinal tumor DLNs of WT mice inoculated with B16-OVA melanoma cells. Donor cells were in vitro activated, transferred on day 14 of tumor growth, and analyzed 6 days later.

(A–J) Each dot represents a biological replicate. Data are parametric except those noted by a hash symbol (#). For parametric data, unpaired t tests were performed; Mann-Whitney test used for non-parametric data. Error bars are SEM. The experiment was performed 1× (B, TOX; E–G), 2× (A and B, TCF-1; H–J), or 33 (C and D).

See also Figure S6.

Differential interleukin-7 receptor α (IL-7Rα) and KLRG-1 expression by CD8+ T cells classically delineates short-lived effector cells (SLECs) and memory precursor cells (MPECs),27 and LCMV Arm infection skews GP(33–41)-specific PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells toward the MPEC phenotype.7 Previous studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between TOX and KLRG-1 expression during LCMV Cl13 infection.28 We observed that all KLRG-1+ cells were within the TOX− population for both WT and PSGL-1−/− GP(33–41)+ T cells. In TOX−GP(33–41)+ T cells, there were fewer IL-7Rα−/KLRG-1− cells in PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells and an increased representation of the IL-7Rα+/KLRG-1− and IL-7Rα+/KLRG-1+ populations (Figures S6A and S6B), further indicating decreased exhaustion.

Unlike GP(33–41)+ T cells, which persist throughout LCMV Cl13 infection, CD8+ T cells recognizing the higher avidity epitope NP(396–404) are deleted,29,30 yet these cells are retained in PSGL-1−/− mice.6 Within NP(396–404)+ T cells, fewer PSGL-1−/− T cells expressed TOX at both 9 and 15 dpi, whereas fewer PSGL-1−/− T cells expressed only TCF-1 at 9 dpi (Figure 6C). While expression levels of TCF-1 were indistinguishable for GP(33–41)+ or NP(396–401)+ T cells, TOX expression levels were consistently lower in PSGL-1−/− virus-specific T cells (Figure 6D). These data indicate that PSGL-1 deficiency prevents terminal differentiation of TEX in part by limiting the expression of TOX. To confirm that this is a cell-intrinsic effect, we performed co-transfer experiments. At 60 dpi with LCMV Cl13, the frequencies of WT and PSGL-1−/− P14 CD8+ T cells were comparable, yet more PSGL-1−/− P14 CD8+ T cells displayed Slamf6 (which is highly co-expressed with TCF-1 on TPEX31) and IL-7Rα (Figure 6E). Evaluation of TCF-1 and TOX expression in co-transferred donor P14 cells revealed that more PSGL-1−/− P14 CD8+ T cells were single positive (SP) for TCF-1 as well as double positive (DP) for TCF-1 and TOX compared with WT P14 CD8+ T cells (Figures 6F and 6G). Conversely, more WT P14 CD8+ T cells expressed TOX only (Figures 6F and 6G). Taken together, these data demonstrate that PSGL-1 signaling intrinsically regulates CD8+ T cell differentiation in response to repeated antigen exposure.

To assess whether PSGL-1 engagement is a driver of TOX and TEX differentiation, we assessed TCF-1 and TOX expression in virus-specific GP(33–41)+ T cells from LCMV Cl13-infected WT mice following PSGL-1 agonist antibody treatment. PSGL-1 ligation reduced the expression of TCF-1 by 25%, while TOX expression was increased by 50% (Figure 6H). To address T cell intrinsic effects of PSGL-1 regulation on TCF-1 and TOX expression in response to melanoma, we analyzed adoptively transferred activated WT and PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells in B16-OVA tumor-bearing WT mice. The frequencies of TCF-1+CD44+OT-I+ T cells was modestly increased with intrinsic PSGL-1 deficiency (Figure 6I, left panels). In the tumor DLN, essentially all donor OT-I cells were TCF-1+, but fewer cells co-expressed TOX in PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells (Figure 6I, right panels). Evaluation of TCF-1 and TOX showed that PSGL-1−/− OT-I TILs displayed a modest increase in TCF-1+ SP cells but decreased TOX+ SP cells and increased TCF-1/TOX DP cells (Figure 6J). These data show that PSGL-1 deficiency restrains the progressive differentiation toward terminal exhaustion by infiltrating tumor-specific TEX.

As adoptive transfer of a sufficient number of activated PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells can significantly reduce tumor growth,6 we performed adoptive co-transfers with doses of OT-I cells that are unable to inhibit B16-OVA to assess the intrinsic ability of PSGL-1 to impact T cell differentiation in the same TME. Unlike in single-transfer experiments, PD-1 and TIM-3 co-expression on donor OT-I CD8+ T cells was largely equivalent in a co-transfer setting (Figure S6C). 7 days after donor cell injection, there was no significant difference in the frequency of TCF-1-expressing OT-I CD8+ T cells, while there was a trend toward decreased frequency of TOX-expressing cells in PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells (Figure S6D). However, the overall expression of TOX on a per-cell basis was significantly decreased in PSGL-1−/− T cells compared with WT T cells in the same animals (Figure S6E). As differential TCF-1 and TOX expression in murine CD8+ T cells can denote cells that are the least and most terminally differentiated, we sought to identify cells that have recently differentiated from progenitors. Thus, we evaluated expression of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1, which distinguishes highly functional effector CD8+ T cells differentiated from TCF-1+ progenitor cells.32 Significantly more PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells expressed CX3CR1 (Figures S6F and S6G) and also expressed more CX3CR1 on a per-cell basis (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) (Figure S6H), indicating less differentiation of the PSGL-1−/− OT-I cells toward terminal exhaustion when in the same TME. As decreased TOX expression consistently distinguished PSGL-1−/− T cells in the settings of melanoma and chronic antigen stimulation, while PSGL-1 ligation enhanced TOX expression, our data confirm a fundamental and intrinsic role for PSGL-1 in regulating TEX differentiation.

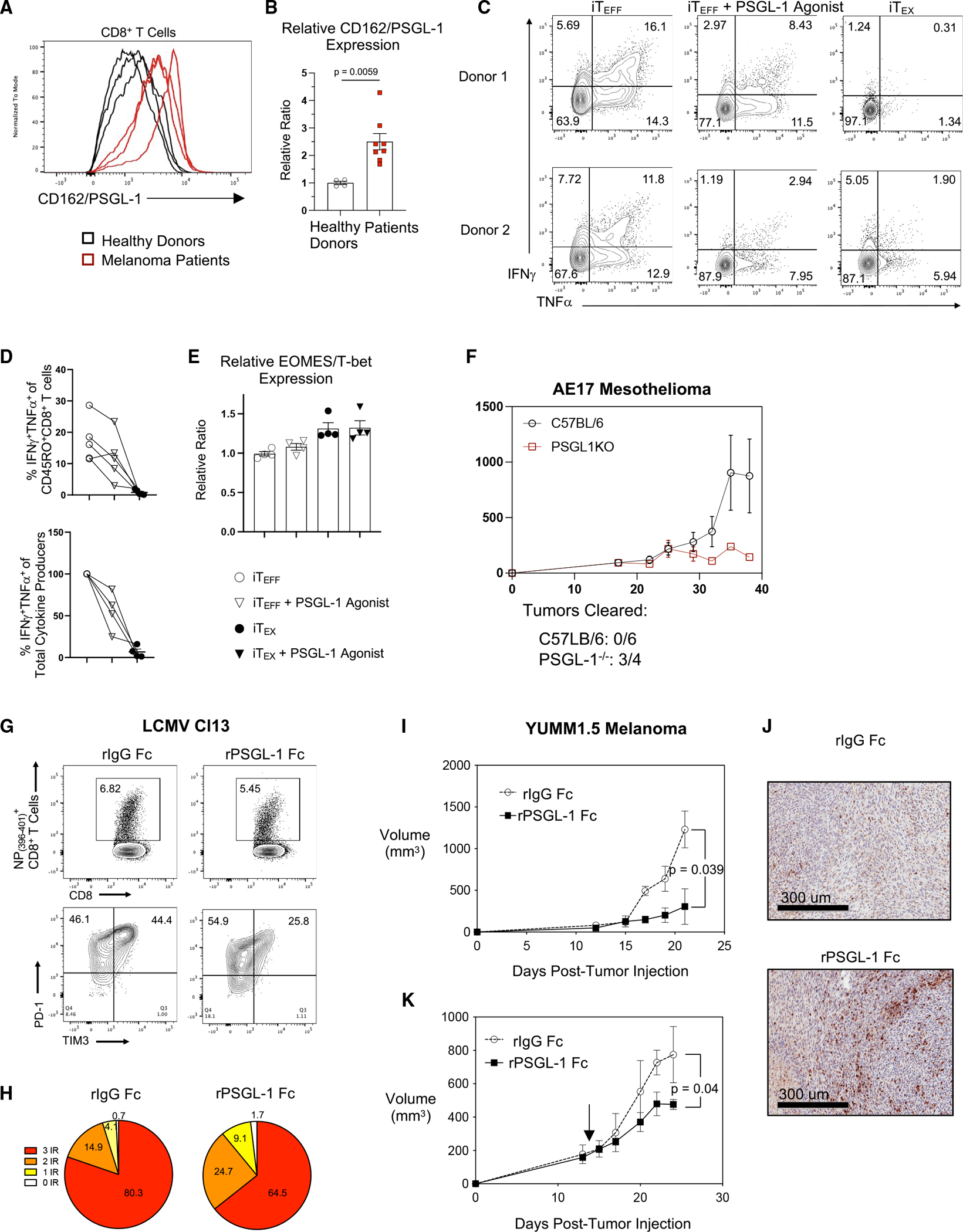

PSGL-1 signaling promotes exhaustion in human CD8+ T cells

As PSGL-1 promotes TEX differentiation, we hypothesized that PSGL-1 expression would be increased on CD8+ T cells from patients with melanoma similarly to PD-1 or CTLA-4 expression. PSGL-1 (CD162) expression and cytokine production were evaluated with stimulated CD8+ T cells from healthy donors and from patients with melanoma. Patient CD8+ T cells, which demonstrated increased PD-1/TIM-3 expression and decreased cytokine production (Figures S7A and S7B), showed a 2.5-fold increase in PSGL-1 expression (Figures 7A and 7B). Of note, increased PSGL-1 expression was observed on all activated CD8+ T cells, which may be reflective of “bystander” CD8+ T cell activation, a form of antigen-independent T cell activation previously observed in some virus infections and cancers.33 As previous studies have reported systemic inflammation in patients with metastatic melanoma,34 the level of PSGL-1 expression on patient CD8+ T cells may correlate with systemic inflammation and/or responses to immunostimulatory treatments.

Figure 7. Pharmacological inhibition of PSGL-1 promotes decreased T cell exhaustion and functional T cell responses.

(A) Histograms of CD162/PSGL-1 expression on activated CD8+ T cells from 3 healthy donors and 3 patients with melanoma.

(B) Relative expression of PSGL-1 on CD8+ T cells from healthy donors and patients with melanoma.

(C–E) PBMCs from healthy donors were assessed for transcription factor expression or restimulated to assess cytokine production.

(C) Flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and TNF-α production by CD8+ T cells from two different healthy donor PBMCs after iTEFF or iTEX culture and restimulated on day 9; pre-gated on live, CD8+CD45RO+ cells.

(D) Top: frequencies of IFNγ and TNF-α double-producing CD8+CD45RO+ cells cultured under iTEFF, iTEFF + PSGL-1 agonist, or iTEX conditions. Lines are connecting data from the same donor under the different culture conditions. Bottom: relative reduction of IFNγ and TNF-α double-producing CD8+CD45RO+ cells upon PSGL-1 ligation under iTEFF conditions (4 out of 5 donors).

(E) EOMES/T-bet expression ratio in CD8+CD45RO+ cells from donors in (D).

(A–E) Each dot represents a unique donor. Experiments were performed 2× (A and B) or 3× (C–E). Data are parametric data; unpaired t tests were performed. Error bars are SEM.

(F) Growth (volume) of AE17 mesothelioma tumors in C57BL/6 and PSGL-1−/− mice.

(G) Top: splenic NP(396–404)-specific CD8+ T cells of control- and recombinant PSGL-1-human Fc protein (rPSGL-1 Fc)-treated LCMV Cl13-infected mice assessed on 8 dpi. Bottom: PD-1 and TIM-3 expression on NP(396–404)-specific CD8+ T cells.

(H) Co-expression of PD-1, LAG3, and TIM-3 on NP(396–404) specific CD8+ T cells assessed via Boolean gating.

(I) Growth of YUMM1.5 tumors in control C57BL/6 mice and mice treated with rPSGL-1 Fc beginning on day 0.

(J) Representative H&E histology with anti-CD3 staining of YUMM1.5 tumor sections collected on day 21. (K) YUMM1.5 tumor volumes following therapeutic treatment with rPSGL-1 Fc beginning on day 14.

(F–J) Experiments were performed 2× with >3 mice/group per experiment.

See also Figure S7.

Given that PSGL-1 ligation promotes CD8+ T cell exhaustion during LCMV Cl13 infection and increased YUMM1.5 tumor growth, we addressed whether PSGL-1 similarly regulates human CD8+ T cells by establishing an in vitro model of human TEFF and TEX differentiation from healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using single (iTEFF) or repeated (iTEX) TCR stimulation. These conditions generate polyfunctional IFNγ- and TNF-α-producing iTEFF and iTEX that fail to produce cytokines upon restimulation. Restimulation of iTEFF after 9 days of culture resulted in CD45RO+CD8+ T cells with a robust capacity to individually produce and co-produce IFNγ and TNF-α (Figures 7C and 7D), while iTEX failed to produce significant amounts of either cytokine (Figures 7C and 7D).

Terminally exhausted TEX express lower levels of T-bet and increased levels of Eomes (compared with TEFF) in chronic LCMV Cl13 infection,35 in patients with HIV,36 and in the context of cancer.37 In our in vitro model, relative Eomes/T-bet expression increased in iTEX compared with iTEFF (Figure 7E). Combined with decreased function, our results indicate that these in-vitro-generated cells have a phenotype reflective of TEX from patients. This is particularly relevant for human T cells, as TOX expression is not limited to TEX.38 To address how PSGL-1 signaling in human T cells may contribute to CD8+ T cell differentiation, iTEX were cultured in the presence of a PSGL-1 agonist antibody. In 4 out of 5 donors assessed, one-time activation of T cells and addition of anti-PSGL-1 resulted in the decreased ability of these cells to produce and co-produce IFNγ and TNF-α (Figures 7C and 7D). For donors in which cytokine production dropped, capacity for co-production was ~55% of the effector cells (Figure 7D, bottom). Consistent with an incomplete differentiation of iTEX from iTEFF due to PSGL-1 ligation, we observed a modest increase in the relative Eomes/T-bet expression ratio (Figure 7E). When combined with repeated TCR stimulation, the Eomes/T-bet expression ratio of iTEX-treated CD8+ T cells increased to a similar level as iTEFF without PSGL-1 ligation (Figure 7E). These data indicate that signaling via PSGL-1 concomitant with TCR stimulation can intrinsically orchestrate the development of TEX from TEFF in human CD8+ T cells.

Therapeutic PSGL-1 blockade limits T cell exhaustion and promotes tumor control

To evaluate whether the impact of PSGL-1 deficiency extended to cancers beyond melanoma, we tested AE17 mesothelioma tumor growth in WT vs. PSGL-1−/− mice. Like YUMM1.5, AE17 tumors are resistant to ICB treatment.39 PSGL-1−/− mice demonstrated significantly increased control of AE17 tumors (Figure 7F), suggesting the potential for PSGL-1 as a pan-cancer ICB target. We therefore tested therapeutic blockade of PSGL-1. As the available anti-PSGL-1 antibody (Clone 4RA10) acts as an agonist, we reasoned that this may occur via crosslinking via Fc receptor binding on APCs. Thus, monovalent F(ab)s were generated and used to treat LCMV Cl13-infected mice. At 30 dpi, treatment with F(ab) antibodies did not influence the frequency of NP(396–404)+ CD8+ T cells (Figure S7C) but did increase the frequency of cytokine-producing NP(396–401)-specific (Figure S7D) and GP(33–41)-specific (Figure S7E) CD8+ T cells 8 dpi. Additionally, co-expression of the inhibitory receptors PD-1, LAG3, and TIM-3 was decreased in the 4RA10 F(ab)-treated group (Figures S7F and S7G).

Since F(ab)s have a limited half-life, which could account for the modest effects on T cell exhaustion, we generated a recombinant PSGL-1 with human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) Fc (rPSGL-1 Fc) and evaluated virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in LCMV Cl13-infected mice treated with rPSGL-1 Fc or control recombinant human IgG1 Fc (rIgG Fc). Although the frequencies of NP(396–404)+ T cells in the spleens were comparable between rIgG Fc- and rPSGL-1 Fc-treated mice, PD-1+ and TIM-3+ DP cells were significantly diminished after rPSGL-1 Fc treatment (Figure 7G). Further, overall co-expression of inhibitory receptors was reduced, consistent with reduced levels of exhaustion (3 inhibitory receptors: 80.3% vs. 64.5%) (Figure 7H). Similar results were observed when WT (CD45.2+) mice that received WT P14 (CD45.1+) CD8+ T cells were treated with rPSGL-1 Fc, as well as decreased TOX expression (Figure S7H) and increased IFNγ production (Figure S7I).

Finally, to evaluate whether PSGL-1 blockade using rPSGL-1 Fc could promote T cell responses to cancer, we evaluated YUMM1.5 tumor growth in mice administered rPSGL-1 Fc or rIgG Fc control at the time of tumor cell inoculation (Figures 7I and 7J) or after tumor growth was established 14 days later (Figure 7K). Treatment with rPSGL-1 Fc at the time of tumor cell injection resulted in significantly reduced tumor growth that was comparable to that achieved in PSGL-1 deficient mice,6 and T cell infiltration assessed by anti-CD3 staining indicated that rPSGL-1 treatment enhanced the infiltration and/or expansion of T cells within the tumors (Figures 7I and 7J). With established tumors, we found that PSGL-1 blockade reduced tumor growth (Figure 7K), demonstrating the feasibility of achieving inhibition of PSGL-1 signaling at a time when the growth of PD-1 ICB-resistant cancers is uncontrolled.

DISCUSSION

Here, we investigated mechanisms contributing to the function of PSGL-1 as an intrinsic T cell checkpoint inhibitor that we now show acts upstream of PD-1. We demonstrate that PSGL-1 engagement limits responses to TCR signaling that promote T cell activation and TEFF development by inhibiting proximal TCR signaling. Importantly, this was demonstrated in the absence of CD28 co-stimulation. As PD-1 blockade requires CD28 co-stimulation to reinvigorate CD8+ T cells,40 PSGL-1 blockade therefore represents a potential mechanism to restore exhausted CD8+ T cells in patients non-responsive to PD-1 ICB. Notably, PSGL-1 inhibits T cell activation to low levels of TCR stimulation and low-affinity TCR ligands, indicating that PSGL-1 is a fundamental regulator that plays an essential role in preventing excessive T cell responses. Our finding that Sts-1 is diminished but not absent in PSGL-1−/− T cells suggests that although TCR signaling is enhanced, terminal T cell differentiation is curtailed, supporting greater development of TSC and progenitors with TEFF capacity under conditions of repeated antigen stimulation that otherwise promote TEX development. Our results, which show greater Zap70 activation and enhanced downstream T cell signaling in the absence of PSGL-1, demonstrate that these events support effector functions, which rely upon enhanced glycolytic metabolism and glucose uptake. Further, single-cell analyses of TILs demonstrate that metabolic reprogramming in PSGL-1-deficient T cells enhances the gene expression of multiple enzymes that regulate glycolysis. These results demonstrate that PSGL-1-dependent regulation of TCR signal strength constrains CD8 T cell metabolic activity to limit antitumor responses, providing a mechanism by which PSGL-1 acts as an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Our data show that PSGL-1 is a regulator of terminal TEX differentiation and that, in its absence, CD8+ T cells can retain stemness as well as TEFF responses in the context of chronic antigen stimulation. In contrast, PD-1 deletion enhances TEFF functions at the expense of stemness.41 In the B16-OVA model, most PSGL-1−/− T cells were DP for TCF-1 and TOX, whereas with LCMV Cl13, the vast majority of PSGL-1−/− T cells were TOX−. It is likely that the extent of T cell responses varies in these different models due to differences in inflammation and the strength of TCR engagement, but in all of these settings, PSGL-1 deficiency curtailed terminal TEX differentiation. Our studies also demonstrate that although ligation of PSGL-1 promotes T cell exhaustion and high expression of inhibitory receptors, PSGL-1 does not directly regulate PD-1 expression. Instead, our results support a conclusion that promoting increased responses to low-level TCR engagement or low-affinity ligands is the fundamental mechanism by which PSGL-1 deficiency curtails exhaustion.

A key outstanding question regarding PSGL-1 signaling and T cell differentiation is the ligand driving T cell exhaustion. Like early studies of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway using PD-142 or PD-L1 deficiency43 that highlighted the potential for PD-1 blockade to inhibit T cell exhaustion,44 our studies of PSGL-1-deficient CD8+ T cells reveal that its underlying mechanisms of TCR inhibition could be subverted by ICB of this receptor. Although administration of rPSGL-1 in vivo had profound effects on limiting the development of T cell exhaustion with LCMV Cl13 infection and promoted enhanced YUMM1.5 melanoma tumor control, in vitro addition of rPSGL-1 to T cell culture assays did not limit T cell exhaustion. This may reflect the lack of (or insufficient) ligand expression (e.g., on another immune cell or tumor cell not included in the culture) or additional factors that support binding (e.g., pH selectiveness45). It is also possible that rPSGL-1 employs additional mechanisms or requires specialized niche microenvironments46 to reduce CD8+ T cell exhaustion, which will require further investigation.

Although we previously excluded selectin binding to PSGL-1 as a significant contributor to T cell exhaustion in LCMV Cl13,6 we have not performed these studies in tumor models. We have similarly excluded the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 as relevant ligands in the LCMV Cl13 model.6 Moreover, their interaction with PSGL-1 is inhibited by the anti-PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) 4RA10,47 whereas chemokine-mediated chemotaxis is not ablated by PSGL-1-deficiency or by 4RA10 blockade47 and therefore is unlikely to be a major driver of T cell exhaustion in tumors. The more recently identified PSGL-1 ligand, VISTA, may be of greater relevance in the context of T cell responses and differentiation in tumors. VISTA (B7H5, also called PD-1H) is an inhibitory receptor with high homology to PD-L148 and, independently of PSGL-1, has been identified as a novel target for modulating T cell responses and tolerance.49 However, although VISTA−/− mice are resistant to some tumor models in a CD4+ T cell-dependent manner,50 VISTA blockade therapy in preclinical models has largely shown efficacy only in immunotherapy combination approaches.51 Current studies have so far shown PSGL-1 binding of VISTA in a pH-dependent manner (pH < 6.2) only in vitro, and binding in vivo has yet to be confirmed. Our ongoing studies seek to confirm if VISTA-mediated signaling through PSGL-1 drives T cell exhaustion in vivo in the context of cancer and if other yet-to-be-identified ligands contribute to T cell exhaustion through PSGL-1 binding.

Critically, our blocking studies in the LCMV Cl13 and YUMM1.5 models validate that ICB can recapitulate many aspects of PSGL-1 deficiency and can limit exhaustion in a therapeutic setting with delayed treatment when tumors are established. Our study also suggests a role for the development of PSGL-1-blocking therapies across many types of cancer. Further studies will be required to determine whether PSGL-1 blockade affects the responses of other PSGL-1-expressing cells in our models. Importantly, we show elevated PSGL-1 expression on melanoma patient T cells and that agonism of PSGL-1 signaling in the context of repeated TCR stimulation intrinsically promotes exhaustion in both human and mouse T cell responses. Our results highlight that a key, highly conserved function of PSGL-1 is that of a negative regulator of T cell responses and suggest that targeting PSGL-1 could enhance the potential of achieving more sustained antitumor T cell responses.

Limitations of the study

Our study primarily uses a model of genetic PSGL-1 deficiency. As such, there is the potential for developmental alterations in PSGL-1−/− CD8+ T cells that contribute to the phenotype observed. Since the recombinant PSGL-1 protein that we developed promotes enhanced T cell responses and limits T cell exhaustion in chronic LCMV infection and models of melanoma tumors, interfering with PSGL-1 signaling is sufficient to alter T cell differentiation. However, we did not find that addition of recombinant PSGL-1 protein to in vitro T cell assays impacts T cell responses. Future studies investigating how recombinant PSGL-1 effectively limits T cell exhaustion will provide further insight into the in vivo interactions of PSGL-1 expressed on T cells with potential ligands.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Linda Bradley (lbradley@sbpdiscovery.org).

Materials availability

There are restrictions to the availability of recombinant PSGL-1 protein due to a pending patent. There are licensing restrictions for PSGL-1−/− mice crossed to transgenic lines.

Data and code availability

Single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE226523) and ATAC-seq data (GSE226521) have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. Original western blot images, proteomics data, microscopy data, and flow cytometry data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data (GSE80113, GSE89036). These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| BUV395 Mouse Anti-Human CD4 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563550; RRID: AB_2738273 |

| BUV395 Rat Anti-Mouse CD8a | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563786; RRID: AB_2732919 |

| BUV496 Mouse Anti-Human CD8 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612942; RRID: AB_2870223 |

| BUV737 Mouse Anti-Human CD45RA | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612846; RRID: AB_2870168 |

| BUV737 Mouse Anti-Mouse CD45.1 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612811; RRID: AB_2870136 |

| BUV737 Rat Anti-Mouse CD11a | BD Biosciences | Cat# 741727; RRID: AB_2871097 |

| BUV737 Rat Anti-Mouse CD223 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 741820; RRID: AB_2871155 |

| BV421 Mouse Anti-Mouse CD244.2 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 740015; RRID: AB_2739787 |

| BV421 Rat Anti-Mouse CD244.1 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 744284; RRID: AB_2871568 |

| BV480 Mouse Anti-Human CD44 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 746479; RRID: AB_2743781 |

| BV605 Mouse Anti-Mouse Ly-108 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 745250; RRID: AB_2742834 |

| R718 Rat Anti-Human CCR7 (CD197) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 751861 |

| R718 Rat Anti-Mouse CD4 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 566939; RRID: AB_2869957 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-human CD101 (BB27) | BioLegend | Cat# 331010; RRID: 2562145 |

| APC/Fire™ 750 anti-human CD45RO | BioLegend | Cat# 304250; RRID: AB_2616717 |

| APC/Fire™ 750 anti-mouse CD38 | BioLegend | Cat# 102738; RRID: AB_2876402 |

| Apotracker™ Green | BioLegend | Cat# 427403 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-human CD38 | BioLegend | Cat# 303526; RRID: AB_10900230 |

| Brilliant Violet 605™ anti-human CD25 | BioLegend | Cat# 302632; RRID: AB_11218989 |

| Brilliant Violet 605™ anti-rat CD90/mouse CD90.1 (Thy-1.1) | BioLegend | Cat# 202537; RRID: AB_2562644 |

| Brilliant Violet 711™ anti-human CD366 (Tim-3) | BioLegend | Cat# 345024; RRID: AB_2564046 |

| Brilliant Violet 711™ anti-mouse CD366 (Tim-3) | BioLegend | Cat# 119727; RRID: AB_2716208 |

| Brilliant Violet 785™ anti-human CD223 (LAG-3) | BioLegend | Cat# 369322; RRID: AB_2716127 |

| Brilliant Violet 785™ anti-mouse CD279 (PD-1) | BioLegend | Cat# 135225; RRID: AB_2563680 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD25 | BioLegend | Cat# 101916; RRID: AB_2616762 |

| APC anti-mouse CD69 | BioLegend | Cat# 104514; RRID: AB_492843 |

| BUV496 Rat Anti-Mouse CD44 | BD Bioscience | Cat# 741057; RRID: AB_2870671 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-mouse CX3CR1 | BioLegend | Cat# 149023; RRID: AB_2565706 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD45.1 | BioLegend | Cat# 110706; RRID: AB_313495 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD49d | BioLegend | Cat# 103606; RRID: AB_313037 |

| Human TruStain FcX™ | BioLegend | Cat# 422302; RRID: AB_2818986 |

| PE anti-human CD39 | BioLegend | Cat# 328208; RRID: AB_940429 |

| PE anti-mouse CD160 | BioLegend | Cat# 143004; RRID: AB_10960743 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-human CD160 | BioLegend | Cat# 341212; RRID: AB_2562876 |

| PE/Dazzle™ 594 anti-human CD279 (PD-1) | BioLegend | Cat# 367434; RRID: AB_2783284 |

| PE/Dazzle™ 594 anti-mouse CD62L | BioLegend | Cat# 104448; RRID: AB_2566163 |

| PE/Dazzle™ 594 anti-mouse CD90.2 (Thy-1.2) | BioLegend | Cat# 140329; RRID: AB_2650965 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-human CD69 | BioLegend | Cat# 310926; RRID: AB_2074956 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD107a (LAMP-1) | BioLegend | Cat# 121626; RRID: AB_2572055 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD223 (LAG-3) | BioLegend | Cat# 125212; RRID: AB_2561517 |

| Purified anti-mouse CD16/32 | BioLegend | Cat# 101302; AB_312801 |

| CD101 PECy7 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 25–1011-82; RRID: AB_2573378 |

| H2-D(b) GP(33–41) APC or BV421 Tetramer | NIH Tetramer Core | N/A |

| H2-D(b) NP(396–401) BV421 Tetramer | NIH Tetramer Core | N/A |

| PE Mouse Anti-TCF-7/TCF-1 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564217; RRID: AB_2687845 |

| PE Mouse Anti-TCF-7/TCF-1 | BD Biosciences | 564217 |

| APC anti-human TNF-α | BioLegend | Cat# 502912; RRID: AB_315264 |

| APC anti-mouse IFN-γ | BioLegend | Cat# 505810; RRID: AB_315404 |

| APC anti-mouse Perforin | BioLegend | Cat# 154304; RRID: AB_2721463 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-human IFN-γ | BioLegend | Cat# 502532; RRID: AB_2561398 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-human/mouse Granzyme B | BioLegend | Cat# 396414; RRID: AB_2810603 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-T-bet | BioLegend | Cat# 644816; RRID: AB_10959653 |

| PE anti-human IL-2 | BioLegend | Cat# 500307; RRID: AB_315094 |

| PE anti-mouse IL-2 | BioLegend | Cat# 503808; RRID: AB_315302 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse TNF-α | BioLegend | Cat# 506324; RRID: AB_2256076 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Mouse Anti-ZAP70 | BioLegend | Cat# 691205; RRID: AB_2721438 |

| Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-Mouse CD3 | BioLegend | Cat# 100228; RRID: AB_2562553 |

| CD162 (PSGL-1) PE | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 12–1621-82; RRID: AB_2848256 |

| EOMES PECy7 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 25–4875-82; AB_2573454 |

| EOMES PerCP-eFluor710 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 46–4877-42; RRID: AB_2573759 |

| Ki67 PerCP-eFluor710 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 46–5698-82; RRID: AB_11040981 |

| T-bet eFluor 450 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 48–5825-82; RRID: AB_2784727 |

| TOX eFluor 660 | eBioscience/ThermoFisher | Cat# 50–6502-82; RRID: AB_2574265 |

| UBASH3B/STS 1 polyclonal Rabbit IgG antibody | Proteintech | Cat# 19563–1-AP; RRID: AB_10643379 |

| B-actin Mouse mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 3700; RRID: AB_2242334 |

| IRDye800CW Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody | Licor | Cat# 926–32211; RRID: AB_621843 |

| IRDye680RD Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody | Licor | Cat# 926–68070; RRID: AB_10956588 |

| Zap70 Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2705; RRID: AB_2273231 |

| Phospho-Zap-70 (Tyr319)/Syk (Tyr352) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2717; RRID: AB_2218658 |

| Akt (pan) Mouse mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2920; RRID: AB_1147620 |

| Phospho-Akt (Ser473) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9271; RRID: AB_329825 |

| p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) Mouse mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4696; RRID: AB_390780 |

| Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Thyr204) XP Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4370; RRID: AB_2315112 |

| Fab anti-mouse CD162 (PSGL-1) | mAb from BioXcell, Fab fragments custom made by Ab Lab (University of Vancourer, BC) | mAb: Cat# BE0186; RRID: AB_10950305 |

| Anti-mouse CD3e | BioXCell | Cat# BE0001–1; RRID: AB_1107634 |

| Anti-mouse CD28 | BioXCell | Cat# BE00015–1 |

| ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activator | StemCell | Cat# 10971 |

|

| ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

|

| ||

| LCMV Clone 13 | This lab | N/A |

|

| ||

| Biological samples | ||

|

| ||

| Human PBMCs, melanoma patients | University of California San Diego, Moore's Cancer Center | N/A |

| Human PBMCs, healthy controls | iXCells | 10HU-003-CR50M |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| SIINFEKL (OVA, N4) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| SIIQFEKL (OVA, Q4) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| SIITFEKL (OVA, T4) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| SIIVFELK (OVA, V4) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| KAVYNFATM (LCMV GP33–41) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| FQPQNGQFI (LCMV NP396–404) | GenScript, Custom Order | N/A |

| Recombinant PSGL-1 | This lab, Aragen Life Sciences | N/A |

|

| ||

| Critical commercial assays | ||

|

| ||

| eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | ThermoFisher | 00–5523-00 |

| 2-NBDG | Cayman Chemical | 11046 |

| Miltenyi Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | 130–096-730 |

| APEX AF488 Microscale Protein Labeling Kit | ThermoFisher | A30006 |

| Seahorse Glycolytic Rate Assays | Agilent Technologies | 103346–100 |

| 10X Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits v2 | 10X Genomics | Multiple |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| WT vs PSGL-1-/- CD8+ T cells, LCMV Cl13 | Reference #6 (Tinoco) | GEO: GSE80113 |

| Epigenetics of CD8+ T cells during differentiation | Reference #59 (Yu) | GEO: GSE89036 |

| Raw and analyzed scRNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE226523 |

| Raw and analyzed ATAC-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE226521 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

|

| ||

| YUMM1.5 melanoma | Marcus Bosenburg | N/A |

| B16-OVA melanoma | Ananda Goldrath | N/A |

| TK-1 T cell lymphoblast | ATCC | CRL-2396 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

|

| ||

| C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| B6.Cg-Selplgtm1Fur/J (PSGL-1-/-) | The Jackson Laboratory | 004201 |

| C57BL/6 Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I) | The Jackson Laboratory | 003831 |

| B6.Cg-Tcratm1MomTg(TcrLCMV)327Sdz/TacMmjax (P14) | The Jackson Laboratory | 025408 |

| B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) | The Jackson Laboratory | 000686 |

| B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ (CD90.1/Thy1.1) | The Jackson Laboratory | 000406 |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| FlowJo v10 | FlowJo, BD | N/A |

| INSPIRE V200.1.388.0 | Amnis | N/A |

| IDEAS V6.2.183.0 | Amnis | N/A |

| SeqGeq | FlowJo, BD | N/A |

| WAVE | Agilent Technologies | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism 9 | GraphPad | N/A |

| MSstats TMT Bioconductor | Bioconductor | N/A |

| IntegrateData | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| RunUMAP | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| FindClusters | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| FindAllMarkers | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| DoHeatmap | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| VlnPlot | Seurat V4.1.1. | N/A |

| Stat_compare_means | ggpubr V0.4.0. | N/A |

| IGV Genome Browser V2.9.2. | Broad Institute | N/A |

| IPA Pathway Analysis | Qiagen | N/A |

| 10X Genomics Cell Ranger V2.2.0. | 10X Genomics | N/A |

| MaxQuant Software 1.6.11.0 | MaxQuant | N/A |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

Mice

C57BL/6J, B6.Cg-Selplgtm1Fur/J (PSGL-1−/−), C57BL/6 Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I), and B6.Cg-Tcratm1MomTg(TcrLCMV)327Sdz/TacMmjax (P14) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Wild type OT-I and P14 mice were backcrossed to the CD45.1 background (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ). PSGL-1−/− were backcrossed to the Thy1.1 background (B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ), and further crossed with OT-I mice or P14 mice to establish these lines with PSGL-1 deficiency. All mice were kept in a barrier facility (certified by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) on acidic water at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Research Institute. After LCMV infection, mice are maintained in BSL2 containment. All lines in the Bradley mouse colony are backcrossed to parental C57BL/6J or B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ lines annually. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations and approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Infection and tumor studies

For tumor initiation, 6–8-week-old male or female mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane gas, their hind flank was shaved, and tumor cells (resuspended in Matrigel (Corning):1X PBS at a 1:1 ratio) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in a volume of 100 μL PBS. For B16-OVA experiments, mice received 1×106 B16-OVA tumor cells. For YUMM1.5 experiments, mice received 5×104 YUMM1.5 tumor cells. For adoptive cell transfers, recipient mice received a tail vein injection of T cells in a volume of 100 μL PBS as indicated for the individual experiments. When naïve T cells were transferred, cells were first mixed 1:10 with C57BL/6 splenocytes obtained from uninfected/non-tumor-bearing wildtype mice. For co-transfer studies with LCMV Cl13, mice received 5×104 each of naïve WT (CD45.1+) and PSGL-1−/− (CD90.1+) CD8+ T cells prior to LCMV Cl13 infection. For experiments where T cells were activated prior to transfer, naïve WT (CD45.1+) or PSGL-1−/− (CD90.1+) OT-I CD8+ T cells were activated with immobilized anti-CD3ε (145–2C11, BioXcell) and anti-CD28 (37.51, BioXcell)(5 μg/mL, each) for 3 days prior to transfer. 1×106 activated WT or PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells were then injected I.V. into tumor-bearing C57BL/6 (CD45.2+/CD90.2+) mice. For co-transfer studies with B16-OVA, B16-OVA tumor bearing mice received 5×105 each of activated WT (CD45.1+) and PSGL-1−/− (CD90.1+) CD8+ T cells on day 14. Tumor growth was assessed three times per week by an investigator blinded to the experiment hypothesis. For YUMM1.5 studies, only male mice were used due to the presence of male antigen on the YUMM1.5 tumors. At the indicated time points, tumors, spleens, and inguinal draining and non-draining lymph nodes were collected. For LCMV Clone 13 infection, 6–8-week-old male and female mice received an intravenous injection of 2.5×106 FFU in a final volume of 100 μL PBS. At the indicated time points, spleens were collected.

PSGL-1 signaling inhibition treatment

(A) Anti-PSGL-1 F(ab) antibody treatment. Commercially available anti-PSGL-1 antibody (4RA10, BioXCell) and control rat IgG were enzymatically digested into F(ab) and purified by Ab Lab (University of Vancouver, British Columbia). C57BL/6 mice infected with LCMV Cl13 were treated with 100 μg of rat IgG F(ab) (control F(ab)) or anti-PSGL-1 F(ab) via intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection twice (AM and PM) on days 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 of virus infection. (B) Recombinant PSGL-1 treatment. For LCMV Cl13 infection studies: C57BL/6 mice infected with LCMV Cl13 were treated with 100 μg of recombinant human Fc protein (control Fc) or recombinant PSGL-1-human Fc protein (rPSGL-1 Fc) via intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection on days 0, 3, and 6 of infection. For YUMM1.5 melanoma studies: YUMM1.5-tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice were treated with 100 μg of recombinant human Fc protein (control Fc) or recombinant PSGL-1-human Fc protein (rPSGL-1 Fc) via I.P. 3x/week beginning at the indicated time (day 0 or day 14).

Tissue processing

Tumors were processed using the Miltenyi Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit and gentleMACS C tubes (Miltenyi) according to manufacturer’s instructions, except with the intentional exclusion of enzyme R (due to cleavage of PSGL-1 and CD44). Spleens and lymph nodes were processed into single-cell suspensions by manual dissociation through a 70μM filter (Falcon) using a cell strainer pestle (CELLTREAT). Tumors, spleens, and lymph nodes were processed and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Corning) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin/L-glutathione. Tumors and spleens were treated with RBC lysis buffer (0.145 M NH4Cl, 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.2) for ~1 minute at room temperature.

Human subjects

All human PBMC samples were obtained in line with the Declaration of Helsinki principles and with prior Institutional Review Board approval. Cryopreserved healthy donor PBMCs were purchased from iXCells Biotechnology (San Diego) and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Melanoma patient samples were obtained in association with the UCSD Moores Cancer Center under the UCSD Moores Cancer Center Biorepository IRB (protocol number 090401). All participants provided written informed consent before the study. Patient samples were deidentified and no clinical data beyond diagnosis of melanoma was provided, ensuring the confidentiality of the subject’s protected health information. Peripheral blood was obtained via venipuncture into a sodium heparin coated vacutainer (BD Green Top). PBMCs were isolated using SepMate PBMC Isolation Tubes (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, CA) pre-filled with 15 mL of Lymphoprep (StemCell) and following manufacturer’s instruction. Isolated PBMCs were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until use.

Viruses

LCMV C13 propagation

LCMV Cl13 virus was propagated using BHK-21 cells. BHK-21 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptamycin (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco), and 5% tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco). BHK-21 cells were infected with a MOI of 0.01 of LCMV Cl13 virus stocks (kind gift of Juan Carlos de la Torres) and gently rocked for 1 hour before removal of virus and replacement of media. After 48 hours of virus propagation, viral supernatant was collected, aliquoted and stored. Quantification of virus stocks was completed using the focus forming assay and Vero cells.

Cell lines

Tissue culture

YUMM1.5 tumor cells were confirmed to lack PSGL-1 expression by qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis. The YUMM1.5 melanoma tumor cell line (male) were cultured in Iscove’s Modified DMEM (IMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 105 I.U. Penicillin, 105 μg/mL Streptomycin, and 292 mg L-glutamine (Corning Cellgro). B16-OVA melanoma tumor cells (female) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning), 105 I.U. Penicillin, 105 μg/mL Streptomycin, 292 mg L-glutamine, and 2 μg/mL Geneticin. Cells were maintained in vitro at 37°C, 5% CO2. For in vivo experiments, tumor cell aliquots from the same passage were thawed one week and passaged 3 times prior to injection. For culturing of primary human and mouse T cells and TK-1 mouse T cells, cells were cultured in complete T cell media: RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 105 I.U. Penicillin (Gibco), 105 μg/mL Streptomycin (Gibco), [10 mM] HEPES buffer (Gibco), [1 mM] Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), 1X MEM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), and [0.55 mM] betamercaptoethanol (Gibco). Cell lines were not authenticated.

Primary cell cultures

Naïve T cell enrichment

For all experiments in which isolated CD8+ T cells were used, untouched naïve (CD44−CD62L+) CD8+ T cells were enriched via negative selection using biotinylated antibodies at the concentrations indicated in Table 1 and using MojoSort Streptavidin Nanobeads (BioLegend). For total T cell enrichment, biotinylated CD4 was not included. Enrichments were completed in 1X HBSS (Ca2+ and Mg2+ free) containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA at a cell concentration of 1×108/mL. CD8+ T cells enriched in this manner were on average >98% pure and depleted of CD44-expressing CD8+ T cells. In all experiments, naïve CD8+ T cells were enriched from 6–8-week-old male or female mice (depending on the experiment and matching the host recipients in the case of adoptive T cell transfers).

Mouse in vitro T Cell exhaustion

Cells were cultured in complete T cell media supplemented with 5 ng/mL each of recombinant murine IL-7 and IL-15 (PeproTech). One day prior to activation of OT-I cells, C57BL/6 splenocytes were made into a single-cell suspension and treated overnight with IFNγ (5 ng/mL) to induce expression of CD80 and CD86 on antigen presenting cells. Splenic OT-I and PSGL-1−/− OT-I CD8+ T cells were isolated by negative selection with magnetic beads from uninfected female mice 8–10 weeks of age. Cells were cultured at a 1:1 ratio of CD8+ T cells and IFNγ-treated splenocytes at 1 × 106/mL with either one-time stimulation with 50 ng/mL OVA(257–264) peptide for 48 hours (single stim), or with daily peptide stimulation with 50 ng/mL of OVA(257–264) peptide for 5 days (repeated stim). In experiments using SIINFEKL variant peptides, cells received either a one-time stimulation or daily peptide stimulation with 50 ng/mL of the indicated peptide. For all conditions, after 48 hours of culture, cells were washed twice and re-seeded at 0.5×106 cells/mL in complete T cell media. On days two and five, all conditions were harvested and the cells were counted. CD8+ T cells were stained as described below (flow cytometry) to measure activation marker, inhibitory receptor, and transcription factor expression and cytokine production following restimulation with OVA(257–264). Additional activation analysis was performed at 18 hours. N4 = SIINFEKL, cognate peptide; Q4 = SIIQFEKL, ~18-fold decreased affinity; T4 = SIITFEKL, ~70-fold decreased affinity; V4 = SIIVFEKL, ~700-fold decreased affinity.

Human in vitro T Cell exhaustion

Cells were cultured in complete T cell media supplemented with 5 ng/mL each of recombinant human IL-7 and IL-15 (PeproTech) and 10 U/mL recombinant human IL-2. Cryopreserved healthy donor human PBMCs (purchased from iXcells Biotech) were thawed then rested for five hours at 37°C. After resting, cells were cultured at a concentration of 1 × 106 CD3+ cells/mL and stimulated with 6.25 μL/mL of ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T cell activator (StemCell). For PSGL-1 agonist, tissue culture plates were coated with 5 μg/mL of anti-human CD162 (KPL, Biolegend) throughout the experiment (days 0–9). On day three of activation, cells were washed and reseeded at 1×106 cells/mL. Cells were then divided into either iTEFF or iTEX conditions. iTEFF conditions did not receive additional ImmunoCult after the initial 72 h; iTEX conditions received an additional 6.25 μL/mL of ImmunoCult each day on days three through eight. All conditions were harvested, washed and re-seeded as above on day 6. On day 9, T cells were stained for assessment by flow cytometry as described below to measure activation marker, inhibitory receptor, and transcription factor expression and cytokine production following restimulation with ImmunoCult overnight in the presence of Brefeldin A and monensin.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of reagents

Recombinant PSGL-1

Recombinant PSGL-1 (rPSGL-1) was generated using the pCR3 plasmid backbone and mouse PSGL-1 and human Fc sequences. rPSGL-1 was produced by Aragen under a MTA agreement for the Bradley Lab using transient transfection of plasmid DNA into HEK 293F cells. Expressed protein in supernatants was collected and purified using single-pass chromatography, analyzed for purity and endotoxin levels, and formulated for storage in 1X PBS.

Biological assays

2-NBDG uptake assays

All solutions were prepared in glucose-free, serum-free RPMI. 2-NBDG (Cayman Chemical) uptake was performed with a 200μM solution. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes before proceeding with staining. Cells were resuspended in FACS wash and analyzed within 30 minutes of completion of FACS staining.

T cell activation assays and signaling (mouse)

Naïve CD8+ T cells or total T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) were enriched from WT or PSGL-1−/− splenocytes as above. After enrichment, 1×106 naïve OT-I CD8+ T cells were activated with immobilized anti-CD3ε (145–2C11, BioXcell) in 24-well plates at the anti-CD3ε concentration or for the time indicated. For analysis of activation status, cells were stained for assessment by flow cytometry as described below at 18 hours. For analysis of metabolism, cells were analyzed using the Agilent Seahorse Assays as described below.

For Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total expression levels of signaling molecules, activated cells (and non-activated controls) were washed twice with 1X HBSS and 3–5×106 cells were pelleted for lysis in mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER, Fisher). Protein concentration was normalized for loading based on a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay and mixed with NuPage LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies) before loading. Samples were run on a 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gel (Life Technologies) using the Xcell Mini-cell electrophoresis system in 1X MES SDS Running Buffer (Life Technologies). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the Xcell II Blot Module and 1X Bolt Transfer Buffer with 20% methanol (Life Technologies). Blots were blocked with blocking buffer (LICOR) then incubated overnight with the indicated primary antibody, washed with TBS-T (Cell Signaling), and incubated for 1 hour with appropriate secondary antibodies in blocking buffer (LICOR). Blots were imaged using a LICOR Odyssey and quantified using ImageJ. For phosflow flow cytometry analysis of phosphorylated signaling molecules, naïve WT (CD45.1+) and PSGL-1−/− (CD90.1+) OT-I CD8+ T cells were mixed 1:1 with each other and then with C57BL/6 splenocytes generated from uninfected female mice. T cells were activated in FACS tubes (BD Falcon) by the addition of 10 μM SIINFEKL peptide (GenScript) for the indicated time at 37°C. After activation, pre-warmed 1X BD Phosflow Fix Buffer I (BD) was immediately added to cells and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed with BD Phosflow Perm Wash and permeabilized by the addition of cold BD Phosflow Perm Buffer III while vortexing. After permeabilization, both surface markers and phosphorylated signaling molecules were stained simultaneously in BD Phosflow Perm Wash for 45 minutes. Cells were washed and fixed with 1% formaldehyde prior to data acquisition on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo v10 software (BD).

T Cell activation (human)

Cryopreserved healthy donor human PBMCs (purchased from iXcells Biotech) were thawed then rested for five hours at 37°C. After resting, cells were cultured in complete T cell media supplemented with 5 ng/mL each of recombinant human IL-7 and IL-15 (PeproTech) and 10 U/mL recombinant human IL-2 at a concentration of 1 × 106 CD3+ cells/mL and stimulated with 6.25 μL/mL of ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T cell activator (StemCell) for two days. On day 2, T cells were stained for assessment by flow cytometry as described and cytokine production was assessed following overnight restimulation with ImmunoCult in the presence of Brefeldin A and monensin.

Sts-1 western blot analysis

For Sts-1 Western blot analysis, cells were lysed in M-PER buffer (Thermo Scientific) containing protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration was measured using a BCA assay (Pierce). Equivalent amounts of each sample were loaded on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with antibodies against Sts-1 (Proteintech #19563–1-AP) and β-Actin (Cell Signaling #3700). IRDye®800-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye®680-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR) secondary antibodies were used and detected on an Odyssey CLxsystem.

Flow Cytometry

In all stains, cells were pre-treated with 2.5 μg/mL anti-CD16/32 (Fc Block; 2.4G2; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 15 minutes before continuing with surface staining. For surface stains, 2×106 cells were stained for 20 min on ice. Cells were stained with the fluorochrome conjugated monoclonal antibodies as indicated (Table S1). Where indicated, cells were also stained with APC labeled-tetramers of H-2b major histocompatibility complex class I loaded with GP(33–41), or BV421 labeled-tetramers of H-2Db major histocompatibility complex class I loaded with NP(396–404) provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. After staining, cells were washed twice with 1X HBSS containing 3% FBS and 0.02% sodium azide and fixed with 1% formaldehyde. For staining of intracellular transcription factors, 2×106 cells were stained as above for surface markers. Following the surface stain, cells were permeabilized with eBioscience FoxP3 fixation buffer (ThermoFisher) overnight at 4°C, washed using eBioscience 1X Perm Wash (ThermoFisher), followed by intracellular staining for 45 minutes. Cells were then washed 2 times with 1X Perm Wash containing 0.02% sodium azide and fixed with 1% formaldehyde. Cells were stained with the fluorochrome conjugated monoclonal antibodies indicated in the table below. For staining of intracellular cytokines, 2×106 cells were stimulated with the indicated peptide (OVA: 5 μg/mL SIINFEKL peptide; GP(33–41): 2 μg/mL KAVYNFATM peptide; NP(396–404):2 μg/mL FQPQNGQFI; all from Genscript) or ImmunoCult (for human PBMCs, StemCell) overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences), Monensin (BioLegend), and 10 U/mL recombinant human IL-2. Cells were surface stained as above then fixed overnight at 4°C with FoxP3 fixation buffer (eBioscience), washed using Perm/Wash buffer (eBioscience) and stained for intracellular cytokines for 45 minutes at 4°C. Cells were stained with the fluorochrome conjugated monoclonal antibodies indicated in the table below. 1X Perm Wash containing 0.02% sodium azide and fixed with 1% formaldehyde. All data was acquired on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo v10 software (BD). When protein expression ratios were calculated, they were calculated using the relative median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the indicated proteins.

Fluorescence microscopy and Amnis Imaging Flow Cytometry

CD3 and PSGL-1 localization studies: for Amnis imaging flow cytometry, naive OT-I CD8+ T cells were enriched from WT or PSGL-1−/− splenocytes from 6–8 week old female mice using magnetic bead enrichment. For crosslinking, naïve OT-I cells or TK-1 cells were incubated with anti-CD3ε (145–2C11, BioXcell), anti-PSGL-1 (4RA10, BioXcell), or both for 15 minutes at 4°C. After washing, cells were crosslinked with biotinylated anti-hamster IgG (for anti-CD3; BD Pharmingen) and/or goat anti-rat IgG (for anti-PSGL-1, Sigma Aldrich) and incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde. CD3 localization was detected using FITC conjugated streptavidin (CALTAG Laboratories) and PSGL-1 localization was detected using anti-Rat IgG-PE (BioLegend) following a 30 minute incubation at 4°C. For fluorescence microscopy, stained TK-1 cells were plated on slides pre-coated with CellTak (Corning). For Amnis imaging flow cytometry, cells were imaged immediately using an Amnis Imaging Flow Cytometer.

PSGL-1, Zap70, and Sts-1 localization studies: naïve cells were incubated on plate-bound anti-CD3ε for 20 minutes at 37°C. After washing, cells were stained with anti-Sts-1 AF488 (19563–1-AP, Proteintech; in-house conjugated using APEX AF488 antibody labeling kits, ThermoFisher), anti-CD162 (4RA10, eBioscience), anti-CD3 BV421 (17A2, BioLegend), and anti-Zap70 (A15114B, BioLegend) before fixation in 1% formaldehyde.

For quantification by Amnis Imaging Flow Cytometry, samples were acquired using an ImageStreamX Mk11 (2 cameras) and INSPIRE v200.1.388.0 software. Images were assessed at a 40X objective in high resolution/low speed mode. 10,000 gated events (Hoechst+FITC+, in focus, single cells) were acquired per condition. For analysis, IDEAS v6.2.183.0 software was used and compensation and nuclear localization were calculated using the IDEAS wizard. The Amnis similarity score (a transformed Pearson’s correlation coefficient52) was calculated from these data.

Seahorse

Assays were conducted in Seahorse XF RPMI Medium, pH 7.4 (Agilent) supplemented with sodium pyruvate [1 mM], L-glutamine [2 mM], and glucose [5 mM]. Seahorse XF plates were pre-coated with 22.4 ug/mL of Cell-Tak solution (Corning) as per manufacturer’s instructions on the same day as the assay and 0.3×106 cells were seeded per well. For glycolytic rate assays: rotenone [0.0013 mM]/antimycin A [0.013 mM], and 2-DG [500 mM] prepared in supplemented Seahorse XF RPMI Medium were injected sequentially as indicated. Assays were conducted using an XFp (8 well) system and analyzed using WAVE software (Agilent).

Single-cell RNA-sequencing