Abstract

After pivoting to emergency remote instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic, medical educators have added new techniques to their toolbox. As we welcome a “new normal,” we may be able to teach even more effectively than we did before by adapting some of these techniques. This paper provides an evidence-based decision-making process for faculty to consider what should stay and what should go as they revise and enhance instruction from one semester to another. The SISoSIG process provides opportunities to reflect on lessons learned and discuss how to build on that learning to become even more effective practitioners.

Keywords: Evidence-based practices, Decision-making, COVID-19, Medical education, Teaching practices

Background

Medical education has traditionally balanced theory-based educational practices, including various teaching methodologies, active learning, educational technology, and innovation. Typically, diffusion of innovations can take years to occur [1]. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic forcing medical educators, like all other educators, to move all teaching and learning activities online literally almost overnight, faculty had to learn new tools and teaching techniques quickly. Now that the pandemic is still a long-term presence in our educational environment, faculty need to consider what the “new normal” will look like in regard to their teaching practices. Faculty reflection on the affordances that teaching during the pandemic made commonplace and consideration of how these techniques and artifacts could be used and improved moving forward is a critical aspect of the reflective teaching practitioner as an opportunity to “reimagine campus life” [2].

This paper is intended to help medical educators and staff navigate the decision-making process. The proposed process is evidence-based and provides faculty and staff with techniques and considerations which together provide a powerful tool to reimagine their teaching toolkit. While initially conceived to address the pandemic, it is a process that is useful to implement as faculty prepare their courses from one semester to another.

This systematic and evidence-based approach to decision-making allows medical educators to determine what teaching tools, materials, and techniques should stay and what should go. This process is called “Should It Stay or Should It Go?” (SISoSIG). It ties together theories presented in the literature on decision-making [3], effective teaching practices [4–7], instructional approaches in undergraduate medical education [5, 8–13], evidence-based practices in online learning [14, 15], instructor presence [16], and effective educational media implementation [11, 17–20], in order to present a cohesive approach to making decisions about instruction. In developing the guidelines, the authors drew upon these sources as well as extensive experience in instructional design, instructional technology, teacher education, and curriculum development in order to identify practices that are both technologically and instructionally sound.

Considering this evidence-based process for decision-making supports a university moving forward by engaging in deliberate and thoughtful use of technology, thinking strategically to solve problems in a program or department, maintaining regular and substantive interaction (RSI), considering the changing landscape of accreditation standards and also being ready for a future emergency or a pivot back to online [18, 21, 22].

The guidance offered here is intended to help faculty and institutions navigate the SISoSIG process, enabling them to consider student needs as they implement teaching tools, materials, and techniques that support student learning [23, 24].

The SISoSIG Process

Activity

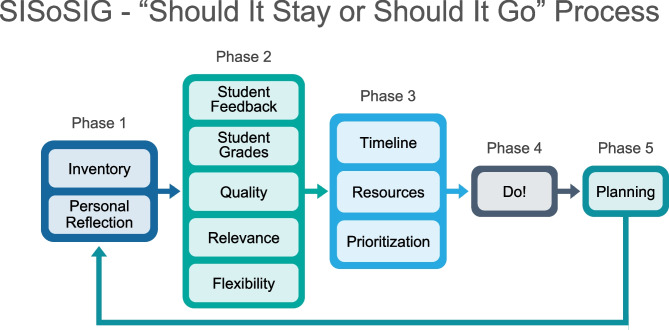

The SISoSIG process contains five phases.

Phase 1

The first phase consists of taking inventory and conducting personal reflection. This is in keeping with the approach of Hall and Hord [25], who stress moving slowly and purposefully from current methods to the new methods rather than leaping from one to the other. When taking inventory, gather all of the teaching tools, materials, and techniques you used during the pivot. You are likely to have recorded lecture videos, recordings of synchronous online classes (Google Meet, Zoom, etc.), online discussion boards, online tests and quizzes, digital versions of handouts, readings, and presentations, and materials for online learning activities (labs, simulations, and case studies, etc.). Once you know what you have, then it is time to reflect on what worked and what did not, what did you like or not like, and why. Also as part of this step, consider if the teaching tool, material, or technique supports your objectives, learning activities, content, and assessment. Course alignment is important for success [4]. Hall and Hord [25] also provide a resource within the Concerns Based Adoption Model (CBAM) to look at “levels of use,” which can help provide observations about the impact of the curricular change. Finally, consider what you can use now or in another emergency situation.

Also remember that you may have hidden, covert, or overt curriculum and instructional elements that should be part of your inventory. Before updating or changing any curricular elements, it is important to ensure that any changes are appropriate to the context of the medical school organization and align to any applicable accreditation standards, talk to your leadership, and use any available tools to ensure that you align with the school’s mission and vision and maintain RSI requirements [22]. It is also important to consider any larger institutional curricular changes or leadership initiatives that may affect your instruction, such as the move to competency-based medical education (CBME) or project-based learning.

During this phase, you should consider developing a project plan for completing this process and create milestones and timelines to ensure you stay on target. Your plan should include elements of communication. Hall and Hord’s [25] CBAM can help in communication as well as identifying attitudes and beliefs of a possible change. When you involve other stakeholders in planning, your reflection on what tools, materials, and techniques support ongoing and upcoming initiatives can be more integrated into an institution’s larger strategic planning.

Phase 2

The second phase of the SISoSIG process is when you engage in an analysis of the artifacts and the data you have to examine their effectiveness, quality, relevance, and flexibility. Start with student feedback and grades. What does student feedback say about the teaching tool, material, or technique; the engagement with content; and the amount of work? What do your students’ grades or performance on subsequent learning activities tell you about learning related to your teaching tools, materials, and techniques? Recent research reports that grades are slightly higher when recorded videos are used than when traditional classroom methods with comparable interactivity are used [19], and blended learning has been shown to result in better student performance than either face-to-face or online alone [15].

Scrutinize whether the teaching tool, material, or technique allows you to provide academic feedback to support student success, maintain RSI, and support robust assessment protocol(s) [22]. Formative pre-class assessments have been shown to be effective in guiding class focus [9].

Next, consider quality. Does this teaching tool, material, or technique:

Show the university and/or you in a professional, positive light?

Have any copyright or accessibility issues?

Provide digestible content?

Use active, interactive, and/or collaborative techniques?

Promote consistency?

Quality considerations for instructional materials include:

The extent to which the materials can help students manage “their own cognitive load” — for example, by enabling them to pause and rewind videos [19].

Their length — for example, chunking content to keep the length short, is more effective for student learning and engagement than longer videos [11, 18].

The level and type of interactivity — for example, standardized patients and online simulations, are effective [13]. Likewise, virtual case studies and virtual whiteboards can enhance instruction in positive ways [20].

Examine if the teaching tools, materials, and techniques are still relevant. Can they stand the test of time? Perennial content is better than topics that may change often. Can they be used by future generations of faculty or other departments? Or, do they provide students with access to content that is too difficult, dangerous, or expensive to do in a lab or on their own [17]? It is also important to determine if the software or tools used will be available and accessible in the future. You do not want to spend time revising content in a tool that the university may only have licensed short-term or is very expensive to maintain.

The last component of this section of the SISoSIG process is flexibility. Does your teaching tool, material, or technique allow for more flexibility in scheduling of class time or access to materials? Does it allow you more time to focus on important work or to be more efficient? Artifacts such as recordings of virtual didactics or demonstrations of technical skills can allow you to use class time for active learning or case studies, but they also offer new flexibility in scheduling, eliminate travel, promote mental health, and validate a work-life balance [5, 6, 8, 11, 16, 20, 23, 26].

Phase 3

The third phase of the SISoSIG process is when you begin to think about allocating the time and resources to what should stay. It takes time to create and edit digital resources and content. How much time do you have to review and revise your teaching tools, materials, and techniques?

As described earlier, teaching tools make up quite a bit of the course’s inventory. You may need to take a deep dive into analytics to identify which tools, materials, and techniques are worth your time. For example, analytics can help you determine which recorded lecture videos are the most important to review. Likewise, now that you are a bit removed from the running of the actual class, reviewing both the discussion board prompts and responses will help you determine if some rate higher on the priority list for modification or if they need to be dropped. In addition to analytics, review items with an eye to whether or not they helped students meet the goals/objectives of the lesson or course.

Conducting a systematic review of your online tests and quizzes for both validity and reliability is also crucial during this phase. It will help you to ensure assessments measure intended outcomes. You can then use this information to review your questions and quiz settings and develop new ones if necessary.

Another consideration during the prioritization phase is that before reusing digital versions of handouts, readings, and presentations, you will need to confirm that all materials and images are compliant with copyright and fair use guidelines. Those that are not usable will need to be recreated from scratch or replaced with ones that you are permitted to use. One way to find images or other content is to use advanced search features in most web browsers. Consider using search filters to ensure the content is labeled for reuse either explicitly or with Creative Commons (https://creativecommons.org/) licenses. The specifics of each of the licenses can be reviewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ [27]. You can use search tools within Google, Flickr, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, and other websites to find Creative Commons licensed products.

Online labs, simulations, and case studies will require further prioritization based on use and student feedback. Look specifically at case studies to ensure currency with both medical guidelines and current techniques.

All of these factors figure into how to prioritize what should stay as is, what should stay and be revised, and what should be let go. Additional factors to consider are:

Do students or faculty need training or support to be successful?

Is it worth revising to make it better?

Does it provide opportunities to develop transferable, real-world skills?

Does it improve/maintain connectedness of the student to the instructor, the student to other students, and/or the student to content?

Does it help you develop a back-up plan [14]?

Faculty have limited time. It is important to be sure that when priorities are set that the most time and effort are spent on the work that will have the largest impact on student success and attainment of the course objectives.

When you think about time and priorities, remember that you are not in this alone. Can you enlist help to complete the work in the time available? The availability of a faculty support team or learning center can assist in the creation of professional materials and help shape what is possible and influence priorities. At the end of your prioritization, take time to reach out to any support teams available to you at your institution. Getting their feedback on your plan will help you to identify its strengths and weaknesses. You may also be able to work with faculty support teams for any updates you need that require specialized skills, such as the creation of unique images, videos, or other options. Keep in mind that these teams need plenty of time to create your new items, so it is best to give them as much lead time as possible or consider development in phases.

Once your priorities are determined, there is a clear plan for action. This work is your first iteration of improvements. You have prioritized current and future work. You may not be able to tackle everything you want to improve immediately, but the key is to move from the planning and prioritization phases into the implementation phase so that lasting improvements can be realized.

Phase 4

The fourth phase of the process is when you get to implement your priorities. This is the phase where you actually do the work to edit or update the artifacts and materials that you prioritized. Focus your efforts on aspects that improve instruction such as effective communication and interaction, multiple modes for content, student support, and meaningful evaluation. Consider the whole student as you design and work. Also consider the data you need to collect to ensure your changes can be reviewed and impacts can be determined when you review your materials in the future.

There are many instructional and curricular paradigms (models) you can turn to in order to do this work. The study of learning theories and instructional/curricular paradigms (models) can help you begin to conceptualize learning in concrete ways; a grounding in theory is the difference between an instructor and an effective educator. By studying theories and paradigms, you can begin to explore the process of learning and how students develop knowledge. It is important for faculty to explore differing approaches by systematically reviewing different paradigms that have the potential to enhance student learning and to construct effective learning experiences [28, 29]. Three seminal works of instructional/curricular paradigms (models) can help in this phase of the process. They are Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction [30], the Dick and Carey instructional design model [28], and Kern’s six-step model [29]. Faculty can use elements of these theories during this implementation phase to ensure what is designed is grounded in best practices. These models take a phased approach to the design of instruction and emphasize design and revision that is critical to the SISoSIG process.

The conditions of learning developed by Gagne [30] is a theory that describes the learning process and posits that there are different types of knowledge and different phases of learning which require different types of instruction. Gagne [30] identifies five major categories of learning: verbal information, intellectual skills, cognitive strategies, motor skills, and attitudes. Different internal and external conditions are necessary for each type of learning. Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction align with the learning processes and conditions of learning and can be used to help guide the design of the learning environment and learning activities for all modalities and types of knowledge though the focus of the theory is on cognitive skills. It is especially helpful for designing online and blended courses, because in these courses, you need to develop the order of events more intentionally and in advance. In the classroom, you may instinctively do this already, but when building a course online, you need to think through what you are actually doing step-by-step so you can actualize it.

The Dick and Carey [28] instructional design model is a nine-step process for planning and designing effective and united curricular components. The model helps to maintain focus on alignment of objectives, activities, and assessment to ensure that revised materials fit well within the course.

Kern’s six-step curriculum design model [29] provides another process to designing instruction. During the implementation phase of the model, it is educational intervention and its evaluation that converts a mental exercise to reality. This model highlights the need to identify and procure resources, address barriers to implementation, and also refine the curriculum over time. The Dick and Carey and Kern models focus on an overarching design process; they do not specifically break down the conditions of learning or the actual learning activities and delivery as Gagne’s model does.

By incorporating facets of these models, you will be able to create learning experiences that support, motivate, and inspire your students to succeed. There are many other instructional/curriculum design models, and it is important to review all models that will inform instruction. While these models are similar, they each take a different approach to the curricular problem at hand and allow for different insights into the instructional design process.

Phase 5

The final phase of the SISoSIG process is planning. Once you have implemented your tools, materials, and techniques, it is time to begin the SISoSIG process again and plan for new and continuous improvements to your course. The process repeats itself over time so that continuous long-term planning can result in increased student achievement and better outcomes. Another model that provides support for continuous planning and improvement is the PDSA cycle [3] of plan, do, implement, and act. No matter which approach you take or which model you follow, ensure you are using evidence-based instructional/curricular paradigms to achieve your goals and objectives for course improvement.

In this final planning phase, you should also look into those longer term ideas that you or your team did not have time for in previous iterations. This is the time to get more information about what it would take to implement such ideas and who will be able to help bring these ideas and plans to fruition. If you are able to work with specialists such as medical illustrators, graphic designers, video studio personnel, and curricular/instructional support teams, remember that they will need lead time to implement advanced projects. Students today expect quality, professional products, so be sure to check in with all the specialists who are available to you so that you can work with them to create the highest quality and most professional product.

Now is also the time to ensure that you have the proper amount of instructional support in place for your students and plan for the development of new support opportunities. Theorist Lev Vygotsky contended that “properly organized learning results in mental development” [31, p. 90]. Drawing on Vygotsky’s work can help you organize learning by identifying opportunities for instructional scaffolding that can assist students in implementing new tasks and concepts that they could not do on their own. Vygotsky [31] posited a Zone of Proximal Development, which depends upon the relationship between what students:

Cannot do

Can do with assistance

Can do without help

Vygotsky described the zone of proximal development as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” [31]

Finally, when implementing the SISoSIG process, be sure to revisit the alignment of objectives, activities, and assessment in phase 1; examine data for effectiveness in phase 2; implement the what, where, why, and how in phase 3; and decide on how to proceed for the future in phase 4 to determine what to keep, what to revise, or what to let go in phase 5.

Conclusion

The SISoSIG process integrates different theories and approaches that necessitate careful consideration of and reflection on your teaching methodologies and techniques, course content, materials, and artifacts. Your role as an instructor is key in delivering quality educational experiences that promote regular/substantive interaction and support accreditation standards [21]. By considering theories and approaches such as decision-making [3], effective teaching practices [4–6, 19], instructional approaches in undergraduate medical education [5, 8–13], evidence-based practices in online learning [14, 15], instructor presence [16], and effective educational media implementation your inventory becomes an opportunity to take stock of all you have done, how you interacted with your students, and what content, materials, and artifacts you have available. Then, reflecting on the effectiveness of those techniques and materials and using data to inform decisions on what to keep, what to revise and what to let go, will enhance the next iteration of the course. Setting clear priorities for the modifications needed for that next iteration is key to maintaining focus on the most important changes and those that will have the most impact. When you move on to implementing the desired changes, students will appreciate and benefit from your making them as professional as possible, which you can do by allocating plenty of time for following established instructional design and curricular models and partnering with faculty support teams. Lastly, planning for continuous improvement is critical. By engaging purposefully in decision-making through the SISoSIG process, faculty are better prepared for the future, while also enhancing their current teaching tools, materials, and techniques.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Douglas Onufro for his work on the graphical representation of the SISoSIG Framework and Dr. Karen Marcellas for her reviews.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily representative of those of the government of the United States, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense (DoD), or the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Health, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Linda S. Macaulay, Email: linda.macaulay.ctr@usuhs.edu

Dina Kurzweil, Email: dina.kurzweil@usuhs.edu.

References

- 1.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amoruso S, Elliott B. Reimagining higher education for the age of flexible work. Inside Higher Ed. 2021, June 2. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/06/02/colleges-shouldnt-expect-their-employees-work-same-ways-they-did-pandemic-opinion.

- 3.Chandarana Tandon S. Lessons and strategies for educators on how to thrive in a redefined post pandemic world. In: REMOTE conference. 2021, June 9. https://www.theremotesummit.org/. Accessed 23 June 2021.

- 4.Biggs J, Tang C. Teaching for quality learning at university. 4. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fatima SS. Flipped classroom instructional approach in undergraduate medical education. Pak J of Med Sciences. 2017;33(6):1424–1428. doi: 10.12669/pjms.336.13699.PMC5768837.PMID29492071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynn J. The effects of a flipped classroom on achievement and student attitudes in secondary chemistry (PDF). In: Montana State University. 2013, July. https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1/2882/GlynnJ0813.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 7.Motz BA, Quick JD, Wernert JA, Miles TA. A pandemic of busywork: increased online coursework following the transition to remote instruction is associated with reduced academic achievement. Online Learning. 2021. 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2475.

- 8.Brian R, Stock P, Syed S, Hirose K, Reilly L, O’Sullivan P. How COVID-19 inspired surgical residents to rethink educational programs. The American J of Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elnicki DM, Drain P, Null G, Rosenstock J, Thompson A. Riding the rapids: COVID-19, the three rivers curriculum, and the experiences of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. FASEB bioAdvances. 2021 doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan K, Adams E, Elsobky T, Darr A, Brackbill M. Moving assessment online: experiences within a school of pharmacy. Online Learning. 2021. 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2580 .

- 11.Rafi AM, Varghese PR, Kuttichira P. The pedagogical shift during COVID 19 pandemic: online medical education, barriers and perceptions in central Kerala. J of Med Education and Curric Development. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2382120520951795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweller J, van Merriënboer J. Instructional design for medical education. In: Walsh K, editor. Oxford textbook of medical education. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- 13.Whited TM, Stickley K, de Gravelles P, Steele T, English B. Using telehealth to enhance pediatric psychiatric clinical simulation: rising to meet the COVID-19 challenge. Online Learning. 2021. 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2485.

- 14.Kim J. 4 reasons why every course should be designed as an online course. Inside Higher Ed. 2020, November 3. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/learning-innovation/4-reasons-why-every-course-should-be-designed-online-course. Accessed 28 June 2021.

- 15.Means B. Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: a meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education; 2009.

- 16.Conklin S, Garrett Dikkers A. Instructor social presence and connectedness in a quick shift from face-to-face to online instruction. Online Learning. 2021. 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2482 .

- 17.Bates T. Post-pandemic lesson 6. We are beginning to see the advantages of media and open educational resources for teaching and learning. In: Online learning and distance education resources. 2020, November 5. https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/11/05/post-pandemic-lesson-6-we-are-beginning-to-see-the-advantages-of-media-and-open-educational-resources-for-teaching-and-learning/. Accessed 25 June 2021.

- 18.Mayer RE. Multimedia learning. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noetel M, Griffith S, Delaney O, Sanders T, Parker P, del Pozo CB, Lonsdale C. Video improves learning in higher education: a systematic review. Rev of Educational Res. 2021 doi: 10.3102/0034654321990713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley E, Capps N, Ward N, McCormack L, Staley J. Maintaining academic performance and student satisfaction during the remote transition of a nursing obstetrics course to online instruction. Online Learning. 2021. 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2474.

- 21.Distance Education and Innovation. 85 Fed. Reg. 54742. 2020, September 2. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-09-02/pdf/2020-18636.pdf.

- 22.Regular and substantive interaction: background, concerns, and guiding principle. (ED593878). ERIC. 2019. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED593878.pdf.

- 23.Kelly R. Survey: what students want to retain post-pandemic. Campus Technology. 2021, June 4. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2021/06/04/survey-what-students-want-to-retain-post-pandemic.aspx. Accessed 25 June 2021.

- 24.Kim J. Avoiding the “snapback”. Inside Higher Ed. 2021, April 14. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/learning-innovation/avoiding-%E2%80%98snapback. Accessed 28 June 2021.

- 25.Hall GE, Hord SM. Implementing change: patterns, principles and potholes. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2015.

- 26.Miyagawa S, Perdue M. What will remain? Inside Higher Ed. 2021, June 9. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/06/09/survey-faculty-way-pandemic-has-permanently-transformed-teaching-opinion. Accessed 24 June 2021.

- 27.Creative Commons. About CC licenses. 2019. https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/. Accessed 5 Jan 2022.

- 28.Dick W, Carey L. The systematic design of instruction. 4th ed. Boston; Pearson; 2015.

- 29.Kern DE. Curriculum development for medical education: a six step approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagne R. The conditions of learning. 4. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vygotsky L. Mental development of children and the process of learning. In: Cole M., John-Steiner V., Scribner S., Souberman E., editors. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press; 1935/1985.