Abstract

We previously constructed a large set of mutants of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) regulatory protein Tat with conservative amino acid substitutions in the activation domain. These Tat variants were analyzed in the context of the infectious virus, and several mutants were found to be defective for replication. In an attempt to obtain second-site suppressor mutations that could provide information on the Tat protein structure, some of the replication-impaired viruses were used as a parent for the isolation of revertant viruses with improved replication capacity. Sequence analysis of revertant viruses frequently revealed changes within the tat gene, most often first-site reversions either to the wild-type amino acid or to related amino acids that restore, at least partially, the Tat function and virus replication. Of 30 revertant cultures, we identified only one second-site suppressor mutation. The inactive Y26A mutant yielded the second-site suppressor mutation Y47N that partially restored trans-activation activity and virus replication. Surprisingly, when the suppressor mutation was introduced in the wild-type Tat background, it also improved the trans-activation function of this protein about twofold. We conclude that the gain of function measured for the Y47N change is not specific for the Y26A mutant, arguing against a direct interaction of Tat amino acids 26 and 47 in the three-dimensional fold of this protein. Other revertant viruses did not contain any additional Tat changes, and some viruses revealed putative second-site Tat mutations that did not significantly improve Tat function and virus replication. We reason that these mutations were introduced by chance through founder effects or by linkage to suppressor mutations elsewhere in the virus genome. In conclusion, the forced evolution of mutant HIV-1 genomes, which is an efficient approach for the analysis of RNA regulatory motifs, seems less suited for the analysis of the structure of this small transcription factor, although protein variants with interesting properties can be generated.

X-ray crystallography is a powerful tool for the study of protein structure and function. However, the use of this method is limited to proteins that crystallize. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat protein is essential for virus replication and is a unique transcriptional trans-activator protein. Tat is recruited to the HIV-1 long-terminal-repeat (LTR) promoter by binding to an RNA hairpin structure termed TAR, which is formed at the 5′ end of viral mRNA (7, 13). Tat is encoded on two exons and is 86 to 101 amino acids in length, depending on the viral isolate. The first 72 amino acids encoded by the first exon are sufficient for the trans-activation function (17, 22, 28, 33, 39). In addition to its essential role in LTR transcription, Tat has been suggested to be involved in other steps of the virus life cycle. Tat has been reported to stimulate the process of reverse transcription (16) and to increase the translational efficiency of HIV-1 mRNAs (8, 34, 36, 44). Despite intensive research for over 10 years, this protein of biological and medical importance has resisted attempts to determine its structure by X-ray crystallography. Furthermore, only limited resolution was obtained by nuclear magnetic resonance studies (3, 14, 26).

In this study, we assess the potential of a genetic approach termed “forced evolution” (3a) for the analysis of the Tat protein structure and function. The systematic analysis of revertant virus genomes is particularly useful for the dissection of sequence and structural determinants of RNA signals that control a variety of steps in the viral replication cycle (6, 21, 29, 30). In addition, intragenic suppressor mutations in revertant HIV-1 viruses have been described for the envelope glycoprotein (43) and the integrase enzyme (37). The tat gene of an infectious HIV-1 genome was mutated to introduce single amino acid changes within the cysteine-rich trans-activation domain. We identified several Tat-mutated viruses that exhibit a severe replication defect in T-cell lines and primary cells (41). In this study, some of the replication-impaired viruses were used as starting material for long-term cultures to allow the generation of faster-replicating revertant viruses. Such virus revertants may have compensated for the introduced mutation by second-site changes elsewhere in the protein, and putative interaction sites can be revealed by this genetic technique.

Two replication-impaired HIV-1 variants with a severely inactivated Tat protein (mutants Y26A and F32A) and two poorly replicating viruses with a partially active Tat protein (F38W and Y47H) were cultured for a prolonged period in multiple, independent evolution experiments. We were able to generate fast-replicating revertant viruses in 30 cultures, of which 21 contained an additional, nonsilent mutation within the tat gene. Of these 21 revertants, 11 first-site revertants were obtained that had replaced the mutant amino acid, either by true first-site reversion to the wild-type amino acid or by mutation to a residue different from that observed in the wild-type Tat protein. Several putative second-site suppressor mutations were observed in Tat, but only one demonstrated improved Tat activity in transient-transfection assays.

The Y26A Tat mutant regained partial activity by inclusion of the Y47N change, and a concomitant increase in virus replication was measured. Surprisingly, when this second-site change was introduced as an individual mutation in the wild-type Tat protein, it improved the activity of this protein to merely 200%. Thus, the Y47N mutation represents a more general manner to make a more active Tat protein, which argues against a specific amino acid contact between Tat positions 26 and 47. We will discuss potential reasons for the absence of a 200% active Tat protein in natural HIV-SIV isolates. The other second-site mutations did not improve the Tat trans-activation function but could have restored a putative additional function of Tat in the viral life cycle. We tested this for some of the revertants in virus replication studies, but none of the revertants demonstrated enhanced fitness compared with the corresponding mutants. We propose that these second-site mutations represent either natural Tat variation or changes that were linked to mutations elsewhere in the HIV-1 genome that did contribute to the reversion event. These results indicate that the systematic analysis of mutant-revertant viruses is not a particularly efficient method for gaining insight into the structure of this small, regulatory viral protein, although this method yielded some Tat variants with intriguing properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, virus infections, and DNA transfection.

The construction of the Tat-mutated HIV-1 LAI proviral clones was described previously (41). The Y47H mutant that was used in this study corresponds to the Y47H2 mutant (codon CAC) described in that study. SupT1 and C8166 T cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml and transfected by means of electroporation (11). For the selection of revertant viruses in forced evolution experiments, we used 30 μg of mutant pLAI plasmid to transfect 5 × 106 SupT1 or C8166 cells. One day after transfection, the cells were split 1 into 6 and divided over a 6-well culture plate to obtain independent reversion events. These cells were cultured for up to 160 days after transfection, splitting the culture 1 into 10 every 4 days. Once virus spread was evident by the appearance of syncytia, we passaged the virus-containing culture supernatant at the peak of infection onto fresh T cells. We initially used 100 μl of cell-free supernatant to infect a 5-ml T-cell culture, but this amount was gradually reduced to 0.1 μl. At regular intervals, infected cells were taken from the culture and frozen for subsequent analysis of the proviral DNA.

Transient transfection of SupT1 cells for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays or viral replication studies has been described previously (41). C33A cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium medium with supplements as described earlier (11) and transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. Briefly, cells were grown to 60% confluency in 60-mm culture dishes. Unless indicated otherwise, we used 1 μg of LTR-CAT reporter plasmid and 100 ng of pTat in transient transfections. The total amount of DNA in the transfection was adjusted to 6 μg with pcDNA3 carrier plasmid in 132 μl of H2O, mixed with 150 μl of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.1)–250 mM NaCl–1.5 mM Na2HPO4 and 18 μl of 2 M CaCl2, incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and added to the culture medium (4 ml). The cells were washed the next day, and fresh culture medium was added.

CAT assays and CA-p24 ELISA.

Transiently transfected cells were collected by trypsinization (adherent cell types) or centrifugation (nonadherent cell types) at 3 days posttransfection. CAT assays were performed on whole-cell lysates by using the phase-extraction protocol (32). The CA-p24 level in cell-free supernatant from virus cultures was determined by antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (2).

Proviral DNA analysis and cloning of revertant sequences.

The Tat expression vector pTat used in this study is a derivative of pcDNA3-Tat (41). A 61-bp HindIII-HindIII fragment in the polylinker of pcDNA3-Tat was deleted to remove an Asp718I site for subsequent cloning purposes. This modified Tat expression vector pTat was used throughout this study. Total cellular DNA from infected cells was isolated as described previously (11). Proviral tat sequences were amplified from total cellular DNA by a standard 35-cycle PCR reaction by using sense primer KV1 (5′-CCATCGATACCGTCGACATAGCAGAATAGG-3′) and the antisense primer WS3 (5′-TAGAATTCTTGATCCCATAAACTGATTA-3′). The 797-bp product was cleaved at the 5′ terminus with ClaI (the recognition site in the primer is underlined) and with Asp718I downstream of the first Tat coding exon and cloned into pTat, thus replacing the wild-type tat gene. Several pTat clones derived from an individual culture were sequenced to determine the sequence variation in the virus population. Sequence analysis was performed with a T7 DYEnamic Direct cycle sequencing kit (Amersham) on an automated DNA sequencer (ABI). Several revertant Tat sequences were subsequently cloned from the pTat vector into the pLAI infectious molecular clone by exchange of a 2.6-kb SalI-BamHI fragment. The Y47N mutation was introduced into wild-type and F32A pTat by PCR mutagenesis (25) with mutagenic primer Y47N (5′-CTTCTTCCTGCCATTGGAGATGCCTAA-3′ [the mismatching nucleotide is underlined]). Cloning of Y47N into the pLAI plasmid was performed as described above. All constructs were verified by sequence analysis.

RNA isolation and primer extension assay.

As an internal control for primer extension analysis, we constructed a modified LTR-CAT reporter plasmid by filling in the HindIII site that fuses the HIV-1 LTR promoter to the cat gene, thus creating transcripts with a 4-nucleotide (nt) insertion (LTR-CAT+4). Transfections of C33A cells for primer extension analysis contained equal amounts of LTR-CAT and LTR-CAT+4. Cells were harvested 2 days after transfection, and total RNA was isolated by the hot phenol method (4), ethanol precipitated, and dissolved in 20 μl of TE. Then, 1 μl of RNA was used for primer extension analysis as described previously (10), with some minor modifications. A new primer, complementary to the 5′ end of the cat open reading frame, was used (Sp6CATAUGrev, 5′-CGATTTAGGTGACACTATAGCTCCATTTTAGCTTCCTTAGC-3′). Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, denatured in the presence of formamide, and analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The cDNA products were quantitated on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Western blotting.

Subconfluent COS cells (60-mm dish) were transfected with 10 μg of the Tat expression vectors by the DEAE-dextran method. The cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer 2 days after transfection, and the proteins were resolved on a 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Mouse monoclonal anti-Tat antibody 4 was used to detect Tat protein in a Western blot analysis as described previously (40).

RESULTS

Tat-mutated HIV-1 and the selection of revertant viruses.

We previously constructed a set of Tat mutants in the HIV-1 LAI isolate (41). Substitution of the aromatic amino acids tyrosine at position 26 and phenylalanine at position 32 by alanine (mutants Y26A and F32A) resulted in replication-impaired viruses. Other mutants include a tryptophane for phenylalanine substitution at position 38 (F38W) that is reduced in Tat activity and virus growth and mutant Y47H. Tat codon 47 (UAU) is special in that it overlaps the Rev translation initiation codon by two nucleotides (…UAUG…). Although the Y47H Tat protein is partially active, virus replication is abrogated because the Rev translation initiation codon is disrupted (…CACG…) (41). This set of four Tat mutants was used in this study to select for revertant viruses in prolonged cultures. Some other Tat mutants that are defective in replication were also subjected to forced evolution, but we failed to obtain revertant viruses. In particular, other Tat codon 47 Rev− mutants could not be reactivated except for a single Y47H culture. Reversion of these virus mutants may be particularly difficult because both the Tat activity and Rev expression need to be restored. In the design of the other Tat mutants, the codon was changed such that it would be relatively difficult for the mutant virus to revert to the wild-type amino acid. For instance, we used the alanine codon GCC to substitute for the phenylalanine codon UUU at position 32. Reversion to the wild-type codon requires mutation of all three nucleotides, whereas only two changes would be required if the alanine codon GCU was used. In other words, we tried to optimize the chances of selecting for Tat revertants with second-site mutations by restricting the ability to generate wild-type revertants.

Forced evolution was initiated by massive transfection of the mutant molecular clones into the SupT1 T-cell line. The cultures were maintained to allow virus spread until any replication-competent variant could expand to a significant portion of the cells, as indicated by CA-p24 production in the culture supernatant and the appearance of virus-induced multinucleated cells (syncytia). Once virus production was apparent, we passaged the cell-free supernatant onto uninfected SupT1 cells, initially with a large inoculum (up to 100 μl of supernatant), but this amount was gradually decreased (e.g., 0.1 μl to infect 106 T cells in a 5-ml culture). To determine the range of mechanisms by which these mutant viruses could restore replication, we attempted to recover revertant viruses in multiple, independent cultures of the Y26A mutant (32 cultures), the F32A mutant (21 cultures), and the Y47H mutant (8 cultures). The cultures in which we succeeded to select for a fast-replicating HIV-1 variant are listed in Table 1. Indicated is the original Tat mutation, the culture number, and the time that this evolution experiment was maintained (in days posttransfection). We obtained fast-replicating virus in a significant number of the evolution experiments with mutant Y26A (9 cultures) and in almost all F32A infections (19 cultures). Infections started with the Y47H mutant did yield only one positive virus culture. We also analyzed viruses in one long-term culture of the poorly replicating but not completely defective F38W mutant.

TABLE 1.

Overview of Tat mutants and revertants

| Tat mutant (% activity) | Culture no. | Evolution time (days) | Tat amino acid changea | Tat codon change | % Tat activityb | Improved replicationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y26A, UAU → GCC (7) | K8 | 45 | A26W (4/4) | GCC → UGG | 86 | Yes |

| K9 | 161 | Y47N (6/6) | UAU → AAU | 23 | Yes | |

| Z1-2 | 58 | |||||

| Z1-3 | 58 | |||||

| Z1-5 | 62 | A26Y (3/3) | GCC → UAU | 100 | Yes | |

| A5 | 77 | |||||

| Y-2 | 104 | |||||

| Y-5 | 137 | A26F (2/2) | GCC → UUC | 103 | Yes | |

| 6.5 | 47 | K50R (1/1) | AAG → AGG | 5 | No | |

| F32A, UUU → GCC (4) | V1d | 98 | K29R (10/10) | AAG → AGG | 5 | No |

| Z4-1 | 58 | A32V (4/4) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| Z4-2 | 58 | A32V (4/4) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| Z4-3 | 62 | K29R (2/5) | AAG → AGG | 5 | No | |

| Z4-4 | 55 | |||||

| Z4-5 | 62 | |||||

| Z4-6 | 62 | A32V (1/2) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| A1 | 104 | Q54R (4/4) | CAG → CGG | 4 | No | |

| A2 | 101 | A32V (3/3) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| A3 | 21 | A32F (3/4) | GCC → UUC | 100 | Yes | |

| 49 | A32F (5/5) | GCC → UUC | 100 | Yes | ||

| A4 | 77 | |||||

| A5 | 77 | |||||

| A6 | 21 | A32F (3/4) | GCC → UUU | 100 | Yes | |

| 49 | A32F (5/5) | GCC → UUU | ||||

| A1 NS | 68 | S70P (2/4) | UCA → CCA | 6 | ND | |

| A2 NS | 68 | C27Y (1/2) | UGU → UAU | 1 | ND | |

| A3 NS | 68 | |||||

| A4 NS | 68 | A32V (3/4) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| A5 NS | 68 | A32V (4/4) | GCC → GUC | 15 | No | |

| A6 NS | 68 | K29R (2/3) | AAG → AGG | 5 | No | |

| F38W, UUC → UGG (42) | Q1.2 | 55 | K29R (12/12) | AAG → AGG | 46 | ND |

| Y47H, UAU → CAC (43) | V4d | 128 | Q17K (2/2) | CAG → AAG | 35 | ND |

First-site mutations are in boldface. The ratios of clones containing the Tat mutation are given in parentheses.

Measured in LTR-CAT+pTat cotransfection of SupT1 cells; wild type = 100%.

Revertant tat gene was reconstructed in the wild-type HIV-1 background. ND, not determined.

Evolution in the C8166 T-cell line.

Sequence analysis of revertant viruses.

The SupT1 cells of cultures containing a replicating virus variant were harvested at the day indicated in Table 1, and the total cellular DNA was isolated. A portion of the integrated HIV-1 proviral genome, including the first Tat coding exon, was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pTat expression plasmid for sequence analysis and transient expression of the variant Tat protein. At least two independent clones were sequenced for each revertant to recognize mutations that may have been introduced during PCR amplification of the proviral genome. In some cultures, Tat sequences were analyzed at multiple times during evolution (e.g., F32A culture A3, days 21 and 49 posttransfection; Table 1). The amino acid changes observed within the first Tat coding exon and the corresponding codon changes are listed in Table 1. In general, it is obvious that some of the revertant viruses did not acquire any mutations in Tat, and these viruses may have improved their replication fitness by other means (see Discussion). We will focus below on those revertants that do contain an additional amino acid substitution in Tat, either at the site of mutation (first site) or at other positions (second sites).

(i) Y26A mutant.

We analyzed all nine revertant cultures of the total of 32 infections that were started with the Y26A mutant. Five cultures acquired a nonsilent mutation in the first Tat coding exon, three at the first site (marked in boldface in Table 1) and two at a second site. Thus, two putative second-site Tat revertants were obtained, Y26A-Y47N and Y26A-K50R, and both will be analyzed in further detail below.

In the three first-site Tat revertants, the mutated A26 residue was changed either back to the wild-type amino acid (tyrosine) or to other aromatic residues (phenylalanine and tryptophane). In fact, the latter two Tat variants were tested previously as part of a large mutational study (41). Efficient LTR-CAT trans-activation was measured for the 26F and 26W variants (103 and 86% of the wild-type level, respectively). Furthermore, efficient virus replication was demonstrated for these two variants, thus confirming that these changes cause the reversion phenotype. These functional Tat data are included in Table 1. It is interesting that relatively difficult mutations were used to change the mutant alanine codon GCC into the codons for these aromatic residues, requiring three transversions (UGG, tryptophane), one transversion and one transition (UUC, phenylalanine), or two transversions and one transition for the wild-type revertant (UAU, tyrosine). Obviously, other possible codons could be generated by a more simple 1-nt substitution, including codons for threonine, serine, proline, aspartic acid, valine, and glycine. The absence of such nonaromatic amino acids in the revertant cultures suggests that these residues do not support Tat function and viral replication. Consistent with this result, nonaromatic residues are not observed at position 26 in the Tat protein of natural HIV-1 isolates, exception for histidine which, like aromatic residues, has a large ring structure (Table 2). These combined results demonstrate the importance of an aromatic side chain at position 26 of the Tat protein.

TABLE 2.

Natural amino acid variation at Tat positions discussed in this studya

| Tat mutation (position) | Amino acid occurrenceb |

|---|---|

| First site | |

| 26 | 51 Y, 4 H, 1 F |

| 32 | 25 F, 20 Y, 7 L, 4 W |

| 38 | 56 F |

| 47 | 56 Y, 1 H |

| Second site | |

| 17 | 52 Q, 2 K, 1 T |

| 27 | 55 C, 1 G |

| 29 | 40 K, 7 R, 3 V, 2 I, 1 L, 1 A, 1 C, 1 Q |

| 50 | 57 K |

| 54 | 48 Q, 3 R, 2 P |

| 70 | 31 S, 26 P |

(ii) F32A mutant.

It was relatively easy to improve the fitness of the replication-impaired F32A mutant. We observed 19 reversions in a total of 21 cultures, and the corresponding viruses were analyzed. Five revertants did not show any amino acid change in the Tat protein. Of the remaining 14 cultures, 8 contained a first-site change (indicated in boldface in Table 1) and a putative second-site change was detected in 6 cultures: K29R (observed three times), C27Y, Q54R, and S70P (each observed once). Some of these changes were not present in all of the clones that were sequenced per reversion event. For instance, C27Y was present in only one of the two clones, and S70P was observed in two of the four sequences (Table 1). Because Tat changes that determine the reversion phenotype are expected to become fixated in the virus population, these changes represent less likely candidates for a mutation that triggered the reversion. In contrast, the K29R mutation in culture V1 became fully fixated (10 of 10 sequences), and this mutation also appeared in two other independent evolution experiments (cultures Z4-3 and A6 NS), suggesting that this Tat variation represents a true revertant. The putative F32A-K29R and F32A-Q54R second-site revertants were chosen for further analysis (see below).

Of the first-site changes of mutant F32A, we observed two mutations back to the wild-type residue phenylalanine and six mutations to valine. The two wild-type revertants were generated by different codon changes (from GCC to UUC and UUU), which demonstrates the independent nature of these evolution experiments. The fact that the wild-type F32 revertant was obtained twice and that no tryptophane or tyrosine variants were selected at this position may indicate that, in contrast to position 26, other aromatic residues cannot replace F32. Indeed, the 32W variant was constructed previously and demonstrated reduced Tat activity (74%), coinciding with a substantial loss of virus fitness (41).

It was surprising that valine was observed six times as an alternative amino acid at position 32 because this residue is not present in natural isolates (Table 2). Frequent observation of the valine revertant may be caused in part by the relative ease of the corresponding nucleotide change (1-nt transition from GCC to GUC). Nevertheless, it is obvious that valine should at least partially restore Tat activity and virus replication. Indeed, we measured improved transcriptional activity for the 32V revertant compared with the 32A mutant in transient LTR-CAT assays (15 and 4% of the wild-type Tat activity, respectively; see Table 1). Introduction of the 32V mutation into pLAI demonstrated that this variation slightly improved virus replication (Fig. 3C). We measured previously that the 15% Tat activity is below the threshold for efficient virus replication (41).

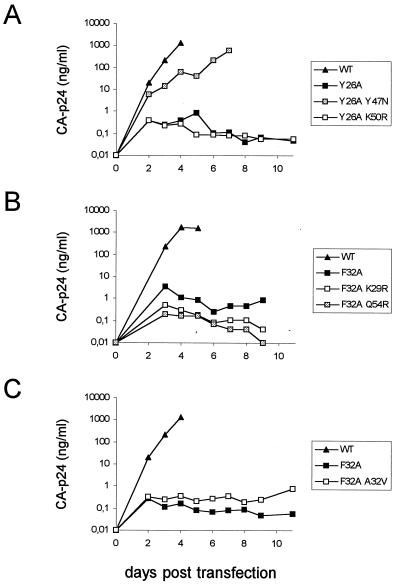

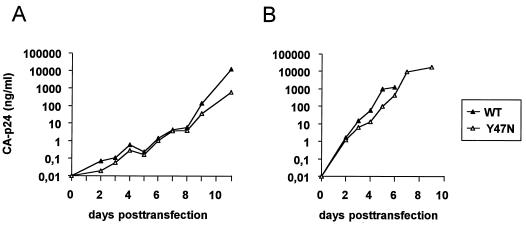

FIG. 3.

Replication kinetics of Tat-mutated HIV-1 viruses and revertants thereof. The SupT1 cell line was transfected with 5 μg of the wild-type, mutant, or revertant pLAI constructs, and virus production was measured by CA-p24 ELISA at several times posttransfection. A slight drop in CA-p24 values was observed in some experiments due to dilution of the culture in order to sustain cell viability and virus replication.

(iii) F38W and Y47H mutants.

The single revertant culture of both the F38W and Y47H mutants was analyzed. The F38W virus maintained the original mutation and acquired a second-site mutation at position 29. This K29R mutation, which was also observed repeatedly in the context of the F32A mutant (see above), was present in all 12 clones that were sequenced, indicating that this amino acid substitution was fixated in the virus population. The Y47H Tat/Rev− mutant acquired the Q17K mutation as a putative second-site Tat adaptation, but this mutation does not repair the Rev start codon.

Functional tests of second-site Tat mutations.

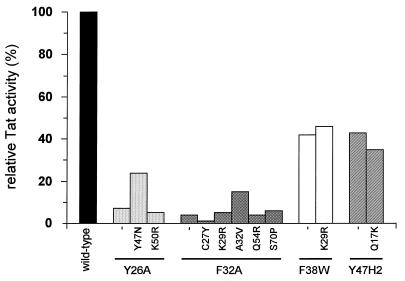

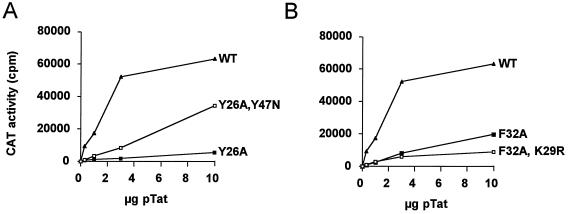

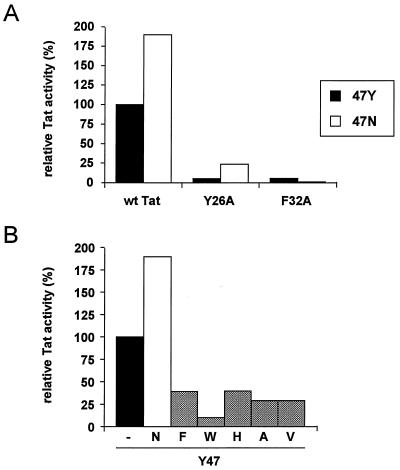

Several putative second-site changes were observed in the Tat protein of revertant viruses. To test which Tat changes represent true second-site suppressor mutations, we analyzed them for recovery of Tat activity in transient LTR-CAT transfection assays. In Fig. 1 we summarize the data of several independent transfection experiments. Wild-type Tat activity was set at 100% (corresponding to approximately 160-fold induction of LTR promoter activity), and the mutant and revertant Tat proteins were tested in parallel for activation of HIV-1 gene expression. Mutant Y26A acquired two independent second-site mutations, Y47N and K50R. Whereas the K50R mutation did not improve the Tat activity, the Y47N mutation increased the activity of the Y26A mutant from 7 to 23% (Fig. 1). We also prepared Tat dose-response curves to see if the trans-activation plateau reached with wild-type Tat can be accomplished with this revertant protein. The Y26A-Y47N double mutant trans-activated the HIV-1 promoter to levels exceeding the 23% activity that was measured in the linear range of trans-activation by the wild-type Tat protein (Fig. 2B). In fact, at even higher Tat levels we measured trans-activation levels that approximated the wild-type trans-activation plateau (not shown). Thus, Y26A-Y47N represents a true second-site Tat revertant. As a final test for the reversion phenotype, we inserted the Y26A-Y47N genotype in the pLAI molecular clone. Note that the AAU codon for asparagine at position 47 does not disrupt the overlapping AUG start codon of the rev gene. Indeed, Y47N was able to rescue the replication defect caused by the Y26A mutation (Fig. 3A). Thus, Y26A-Y47N is a bona fide second-site Tat revertant that partially restores the trans-activation function of Tat, leading to a concomitant increase in virus fitness.

FIG. 1.

Transcriptional activity of mutant Tat proteins and putative revertants. Cotransfections were performed with the LTR-CAT reporter and the indicated Tat variants in the SupT1 T-cell line. The trans-activation activity obtained with wild type was set at 100%. The results represent the average of two to eight transfection experiments.

FIG. 2.

trans-Activation of LTR-CAT in response to increasing amounts of Tat. We used 1 μg of LTR-CAT and 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 μg of Tat expression plasmid in transient transfections of SupT1 cells. (A) Wild-type Tat, mutant Y26A, and revertant Y26A-Y47N. (B) Wild-type Tat, mutant F32A, and revertant F32A-K29R.

Second-site mutations that were observed in the F32A virus (C27Y, K29R, Q54R, and S70P) did not improve the level of Tat-mediated LTR-CAT expression (Fig. 1). This result was somewhat unexpected because the K29R mutation was selected in three independent reversions of the F32A mutant. We also tested Tat activity at various levels of this trans-activator protein, but no gain of function was apparent (Fig. 2B). Likewise, the second-site changes observed in the F38W and Y47H viruses (F38W-K29R and Y47H-Q17K) did not improve the trans-activation capacity of the mutant Tat proteins (Fig. 1). Thus, the majority of putative Tat second-site revertants, including Y26A-K50R, F32A-K29R, and F32A-Q54R, did not improve the Tat activity in LTR-CAT transcription assays.

It remains possible that these second-site Tat mutations rescue virus replication through an effect on another function that Tat may have in the HIV-1 replication cycle, e.g., in the process of reverse transcription (16, 18). Thus, some of the adaptive changes within Tat may have been selected to improve such a nontranscriptional function. To critically test this, some of the yet-unexplained second-site Tat mutations were introduced into HIV-1 LAI to screen for improved replication in comparison with the original mutant. However, we did not observe increased virus replication for the Y26A-K50R virus (Fig. 3A) and the F32A-K29R and F32A-Q54R viruses (Fig. 3B), ruling out a role of these second-site changes in the reversion event.

The Y47N suppressor mutation functions at the transcriptional level.

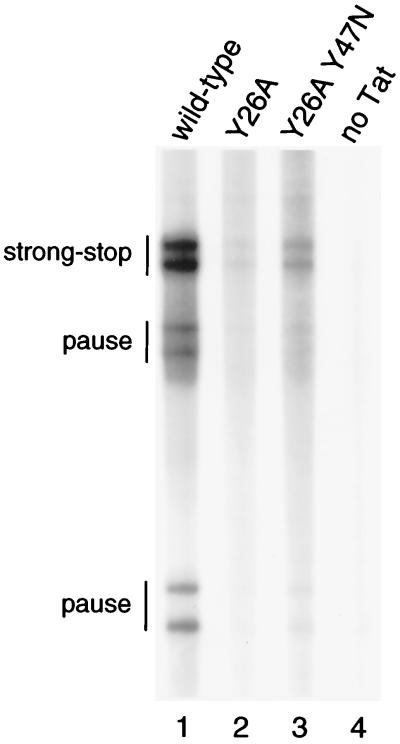

The LTR-CAT trans-activation results obtained with the Y26A-Y47N double mutant do not discriminate between an effect of this second-site Tat revertant at the level of transcription or translation. To test the transcription function of the Tat revertant, we performed direct RNA analyses on extracts of cells that were transiently transfected with the LTR-CAT reporter construct and a Tat expression vector. Total RNA was isolated 2 days after transfection and used in primer extension assays (Fig. 4). In this assay, we used equimolar amounts of the wild-type LTR-CAT construct and a modified LTR-CAT vector with a neutral 4-nt insertion at position +77 of the HIV-CAT fusion transcript. This control plasmid is used as an internal standard for LTR activity in case mutant LTRs are tested. Here, activation of both LTRs will produce a double signal in primer extension assays. No RNA transcripts were detectable in the absence of Tat (Fig. 4, lane 4), but a dramatic upregulation of the two LTR-CAT reporter constructs was caused by the wild-type protein (lane 1). The Y26A Tat mutant demonstrated only 7% activity of the wild-type activity (lane 2), but this value was significantly improved to 17% for the Y26A-Y47N revertant (lane 3). This result is consistent with the CAT assays (Fig. 1) and indicates that this Tat revertant has restored the transcriptional function of the Tat protein. We used Western blot analysis (Fig. 5) to demonstrate that the wild-type, mutant, and revertant Tat proteins are expressed at similar levels.

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis of Tat-induced transcripts. RNA was isolated from C33A cells that were transfected with two different LTR-CAT reporter constructs (see Materials and Methods) and wild-type Tat (lane 1), mutant Y26A (lane 2), revertant Y26A-Y47N (lane 3), or the control vector (lane 4). Indicated are the full-length cDNA products and pause products that are due to stalling of the reverse transcriptase enzyme.

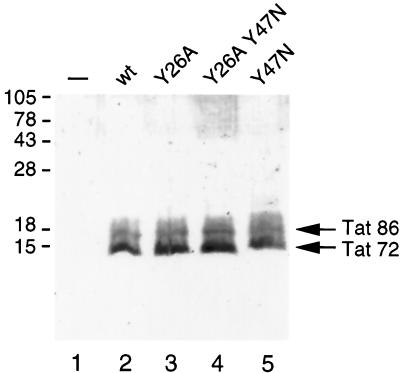

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of wild-type and variant Tat proteins. COS cells were transfected with 10 μg of the indicated Tat expression vectors (lanes 2 to 5). Lane 1 contains a mock-transfected COS cell sample. Total cell extracts were prepared at 2 days posttransfection and analyzed on a Western blot that was stained with Tat monoclonal antibody. The two Tat forms of 72 and 86 amino acids are indicated (41). The positions of the molecular-mass marker proteins are indicated on the left.

The Y47N mutation also improves the function of the wild-type Tat protein.

It is of interest to test whether the Y47N mutation does uniquely improve the function of the Y26A mutant. Such a specificity may be indicative of a direct interaction of amino acids 26 and 47 in the three-dimensional structure of Tat. We therefore introduced the Y47N mutation in the context of the wild-type Tat protein and the inactive F32A mutant. Surprisingly, LTR-CAT transfections revealed that the Y47N mutation does also improve the function of wild-type Tat to merely 200% (Fig. 6A). Thus, the Y47N mutation seems to improve the Tat function in a more general manner, independent of the Y26A mutation. Western blotting demonstrated that the Y47N Tat protein is expressed at a normal level in transfected cells (Fig. 5). The positive effect of the Y47N change is even more striking if one considers the negative effects of many alternative amino acid substitutions that were tested previously at this position (summarized in Fig. 6B). The Y47N mutation was not able to rescue the function of the inactive F32A mutant (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

(A) trans-Activation activity of several Tat proteins. (A) Effect of the Y47N mutation in the context of wild-type Tat, the Y26A mutant, and the F32A mutant. (B) Activities of several codon 47 Tat mutants (some of the data have been published previously ([41]). Wild-type Tat activity is set at 100%.

Although the Y47N mutation improves the activity of the wild-type Tat protein about twofold, this amino acid is not observed in natural HIV-1 isolates (Table 2). We introduced the Y47N mutation in the wild-type LAI virus to test whether the viral replication rate can be improved by a more potent Tat trans-activator. In replication assays, we repeatedly measured a small replication disadvantage of the Y47N mutant compared to the wild-type control (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Replication kinetics of wild-type HIV-1 and the Y47N mutant virus. SupT1 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg (A) or 5 μg (B) of the molecular clones. Virus replication was monitored by measuring CA-p24 antigen production in the culture supernatant at several days posttransfection. In panel A, the culture was split at days 4 and 7 posttransfection, causing a small drop in the CA-p24 values.

DISCUSSION

Long-term cultures were performed with different Tat-defective HIV-1 mutants to screen for second-site reversion events within the tat gene. Fast-replicating virus variants were observed in 30 cultures, and we subsequently analyzed the tat gene. We describe one Tat variant with a second-site amino acid change that restored the activity of the mutant protein. The activity of the Y26A Tat mutant was increased more than threefold by an additional mutation at position 47, where a tyrosine residue was replaced by asparagine (Y47N). Primer extension assays revealed that the suppressor mutation within Tat acted at the transcriptional level. It is demonstrated that the Y47N change can rescue the replication of the Y26A mutant virus. Thus, a tyrosine (Y47) was removed in response to mutation of another tyrosine (Y26). This is somewhat striking because both residues are highly conserved in natural Tat sequences, and replacement by alanine and asparagine as seen in this study is never observed in virus isolates (Table 2). Furthermore, a previous mutational analysis of the wild-type Tat protein indicated that both tyrosines are important for Tat function (41).

A surprising result was obtained when the Y47N suppressor mutation was introduced as an individual mutation in the wild-type Tat context. This Y47N mutant was two times more active than wild-type Tat in transient assays, but the corresponding virus did not replicate more efficiently than wild-type HIV-1 LAI. Apparently, increased trans-activation of the HIV-1 promoter does not increase the viral replication capacity. Several explanations for this phenomenon can be envisaged. First, Tat function may not be limiting in HIV-1 replication, such that an improved Tat protein will not lead to a concomitant increase in virus replication. Second, superactive Tat may be toxic for the host cell and thereby neutralize the positive effect on viral transcription. Third, the Y47N mutation may influence the efficiency of Rev translation because the sequence context of the Rev initiation codon is changed (…UAUG…to…AAUG…). Because Rev production is delicately balanced to coordinate the expression of spliced and unspliced HIV-1 mRNA species, a slightly altered level of Rev protein will disturb this regulation (31). The finding that the Y47N mutation does not enhance virus fitness is consistent with the almost invariant occurrence of a tyrosine residue at this position in natural virus isolates (Table 2). Thus, the analysis of revertant viruses may demonstrate how to improve individual virus functions, but unwanted side effects are likely due to the complexity of this retroviral genome.

The loss of function that is observed for the Y26A mutant may result from aberrant folding of the mutant protein and/or from a loss of interaction of Tat with either TAR RNA or cellular cofactors. In the former scenario, the Y47N suppressor mutation could function to restore the Tat protein structure. However, since the Y47N mutation also increased the trans-activation activity of wild-type Tat, we do not think that the putative effect on the Tat structure is specific for the Y26A mutation. Preliminary structure-probing experiments by limiting protease digestion of recombinant GST-Tat fusion proteins did not reveal gross differences in the degradation pattern of the wild-type Tat protein, the Y26A mutant, and the Y26A-Y47N revertant (results not shown). It is not likely that TAR RNA binding is affected by the Y26A mutation, since the RNA-binding domain of Tat localizes to the basic domain (positions 49 to 57 [38]). However, it remains possible that the Y47N suppressor mutation, which is positioned close to the RNA-binding domain, could enhance TAR RNA binding of the Y26A mutant (and wild-type Tat). We performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays to study the TAR RNA interaction of the mutant and revertant Tat proteins, but no difference was observed (results not shown). Thus, we currently have no molecular explanation for the Y47N reversion event, but it is most likely that this amino acid change does influence the interaction of Tat with cellular cofactors, e.g., the PTEF-b or TFIIH complexes (15, 19, 23, 42, 45) or the Sp1 transcription factor (9, 20). The mechanism of action of the Y47N suppressor mutation is not specific for the SupT1 cells used in these experiments because the same results were obtained in the C33A cell line (results not shown).

Other second-site changes observed in the Tat protein of revertant viruses did not contribute to Tat function but could theoretically improve secondary functions of Tat in the virus life cycle and thus rescue virus replication. We therefore tested several putative second-site revertants in virus replication assays, but no increase in replication capacity was apparent. Thus, no evidence for a role of Tat in processes other than transcription was found. In general, these results underscore the notion that the Tat trans-activation function closely parallels the viral replication rate (41). It is most likely that these second-site Tat mutations represent spontaneous sequence variation within the HIV-1 genome that became fixated in some of these long-term infection experiments. Fixation of the new sequences is possible by nonrandom sampling effects during passage of the crippled mutants (bottleneck passage or founder effect). Alternatively, these fixated mutations may represent “bystander mutations” that were linked to another mutation that did improve replication and which formed the target for selection. Such a random genetic linkage is unlikely to explain the K29R mutation, which was observed three times in independent F32A reversions and in the F38W revertant. It is possible that this particular mutation represents a frequent Tat variation. Consistent with this idea is the fact that both basic amino acids are present in natural HIV-1 isolates (7/56 R, 40/56 K [Table 2]). Similarly, some of the other Tat changes that do not represent true second-site revertants are observed frequently in natural isolates (e.g., Q54R 5/56).

We do not understand how the Y47H virus has gained replication capacity since this particular mutant is also Rev defective. The fixated second-site Tat mutation Q17K seems unable to restore Rev expression, but analysis of the more important second coding exon of Rev in the revertant virus may provide more information. Alternatively, this revertant virus may actually represent a Rev-independent HIV-1 variant. These possibilities are currently under investigation.

A surprising result of this evolution study with Tat-mutated viruses is that virus replication can apparently be restored by changes that map outside the Tat first coding exon. This is not only the case for revertant viruses that do not contain compensatory mutations within Tat but also true for Tat proteins with second-site mutations that do not improve virus fitness. We cannot exclude that suppressor mutations are present in the second Tat coding exon that encodes the C-terminal 14 amino acids. However, we do not expect such mutations in this part of the protein, since the C terminus of Tat contributes only marginally to virus replication (28, 39). It would seem, a priori, to be possible to repair a defect in the Tat transcriptional activator by second-site changes in the LTR promoter. In particular, one would expect LTR changes that improve the basal promoter activity, thus rendering the virus less dependent on Tat. We have described such an LTR adaptation in the culture with the Y26A-Y47N Tat revertant (41a). It is also possible that improvement of other, unrelated viral functions can partially restore the replication of Tat-mutated viruses. For instance, we reported recently that a translation-impaired HIV-1 mutant can dramatically improve its replication by optimizing the mechanistically unrelated Env function (12). This example underscores the notion that the outcome of virus evolution studies can sometimes be very complex and yet intriguing.

One could argue that the forced-evolution approach used here for the recovery of spontaneous revertant viruses is not very effective, since only one true second-site Tat revertant was obtained from 30 cultures that harbored a fast-replicating virus revertant. However, we did isolate 11 first-site Tat revertants, and some were generated by relatively difficult types of mutation (e.g., multiple transversions). These results suggest that there may be very few single amino acid changes at secondary sites that can render the Tat mutants active. This finding suggests the importance of specific residues at these positions, and these amino acids may be involved in interactions with cellular cofactors or the TAR RNA element. Alternatively, these amino acids may be required to form the specific tertiary structure of the Tat activation domain. In this scenario, the conformation apparently cannot be restored by any amino acid change elsewhere in the protein. In addition, the presence of overlapping reading frames (vpr or rev) and RNA signals (splice acceptors or splicing silencers [1]) may put additional constraints on the evolutionary flexibility of the tat gene (28). Thus, the evolutionary approach may not be an efficient method to study structure-function relationships in small proteins with a high information density. Obviously, we cannot exclude the possibility that the activity of these Tat mutants can be restored by multiple amino acid changes at secondary sites, but the probability of finding such hypermutated variants is remote. Perhaps the virus evolution experiment can benefit from strategies to introduce random mutations within the gene under selection (24, 35). Alternatively, part of the tat gene can be provided as a randomized nucleotide sequence (5), such that the search for second-site revertants will occur in a much broader section of sequence space. A major disadvantage of these approaches is that a significant fraction of viral genomes that are manipulated in this way will contain additional mutations that interfere with virus replication.

The forced-evolution approach should be applicable to other virus genes, and perhaps larger proteins and enzymes are more amenable to second-site repair (37, 43). We and others demonstrated previously that this approach is ideally suited for studying RNA elements, in particular structured motifs that play critical roles in virus replication (6, 21, 29, 30). The enormous genetic flexibility of structured RNA motifs is due to the fact that completely different sequences can form very similar base-pair structures. The relative inflexibility of the Tat protein may make it an excellent target for the development of potent anti-HIV drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wim van Est for assistance in preparation of the figures, Benjamin Rowland for assistance with the TAR-RNA binding and protease digestion assays, Jeroen van Wamel for the Western blot analysis, and Tamara Prinsenberg and Rogier Sanders for help with sequence analysis and LTR-CAT transfections. Christine Debouck kindly provided anti-Tat reagents.

This study was supported in part by the Dutch AIDS Foundation, an EMBO short-term fellowship (K.V.), and the European Community (EU 950675).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amendt B A, Si Z, Stolzfus C M. Presence of exon splicing silencers within human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat exon 2 and tat-rev exon 3: evidence for inhibition mediated by cellular factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4606–4615. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Back N K T, Nijhuis M, Keulen W, Boucher C A B, Oude Essink B B, van Kuilenburg A B P, Van Gennip A H, Berkhout B. Reduced replication of 3TC-resistant HIV-1 variants in primary cells due to a processivity defect of the reverse transcriptase enzyme. EMBO J. 1996;15:4040–4049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer P, Kraft M, Ejchart A, Westendorp M, Frank R, Rosch P. Structural studies of HIV-1 Tat protein. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:529–535. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Berkhout, B., and A. T. Das. Functional analysis of RNA signals in the HIV-1 genome by forced evolution. In J. Barciszewski and B. F. C. Clark (ed.), RNA biochemistry and biotechnology, in press. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 4.Berkhout B, Gatignol A, Silver J, Jeang K T. Efficient trans-activation by the HIV-2 Tat protein requires a duplicated TAR RNA structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1839–1846. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkhout B, Klaver B. In vivo selection of randomly mutated retroviral genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5020–5024. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.22.5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkhout B, Klaver B, Das A T. Forced evolution of a regulatory RNA helix in the HIV-1 genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:940–947. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkhout B, Silverman R H, Jeang K T. Tat trans-activates the human immunodeficiency virus through a nascent RNA target. Cell. 1989;59:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braddock M, Thorburn A M, Chambers A, Elliot G D, Anderson G J, Kingsman A J, Kingsman S M. A nuclear translational block imposed by the HIV-1 U3 region is relieved by the Tat-TAR interaction. Cell. 1990;62:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90389-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun R F, Semmes O J, Neuveut C, Jeang K-T. Modulation of Sp1 phosphorylation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. J Virol. 1998;72:2615–2629. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2615-2629.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A T, Klaver B, Berkhout B. Reduced replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants that use reverse transcription primers other than the natural tRNA3Lys. J Virol. 1995;69:3090–3097. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3090-3097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das A T, Klaver B, Klasens B I F, van Wamel J L B, Berkhout B. A conserved hairpin motif in the R-U5 region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA genome is essential for replication. J Virol. 1997;71:2346–2356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2346-2356.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das A T, van Dam A P, Klaver B, Berkhout B. Improved envelope function selected by long-term cultivation of a translation-impaired HIV-1 mutant. Virology. 1998;244:552–562. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait M J, Green S M, Heaphy S, Karn J, Lowe A D, Singh M, Skinner M A, Valerio R. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 tat protein binds trans-activating-responsive region (TAR) RNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6925–6929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freund J, Vertesy L, Koller K P, Wolber V, Heintz D, Kalbitzer H R. Complete 1H nuclear magnetic resonance assignments and structural characterization of a fusion protein of the alpha-amylase inhibitor tendamistat with the activation domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:672–688. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Martinez L F, Mavankal G, Neveu J M, Lane W S, Ivanov D, Gaynor R B. Purification of a Tat-associated kinase reveals a TFIIH complex that modulates HIV-1 transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:2836–2850. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrich D, Ulich C, Garcia-Martinez L F, Gaynor R B. Tat is required for efficient HIV-1 reverse transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:1224–1235. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauber J, Malim M, Cullen B. Mutational analysis of the conserved basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein. J Virol. 1989;63:1181–1187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1181-1187.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L M, Joshi A, Willey R, Orenstein J, Jeang K T. Human immunodeficiency viruses regulated by alternative trans-activators: genetic evidence for a novel non-transcriptional function of Tat in virion infectivity. EMBO J. 1994;13:2886–2896. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeang K-T. Tat, Tat-associated kinase, and transcription. J Biomed Sci. 1998;5:24–27. doi: 10.1007/BF02253352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeang K T, Chun R, Lin N H, Gatignol A, Glabe C G, Fan H. In vitro and in vivo binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein and Sp1 transcription factor. J Virol. 1993;67:6224–6233. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6224-6233.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klaver B, Berkhout B. Evolution of a disrupted TAR RNA hairpin structure in the HIV-1 virus. EMBO J. 1994;13:2650–2659. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuppuswamy M, Subramanian T, Srinivasan A, Chinnadurai G. Multiple functional domains of Tat, the trans-activator of HIV-1, defined by mutational analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3551–3561. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancebo H S Y, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, Peng J, Blau C, Hazuda D, Price D, Flores O. P-TEFb kinase is required for HIV Tat transcriptional activation in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2633–2644. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez M A, Vartanian J P, Wain-Hobson S. Hypermutagenesis of RNA using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and biased dNTP concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11787–11791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikaelian I, Sergeant A. A general and fast method to generate multiple site-directed mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:376. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mujeeb A, Bishop K, Peterlin B M, Turck C, Parslow T G, James T L. NMR structure of a biologically active peptide containing the RNA-binding domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8248–8252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers G, Wain-Hobson S, Henderson L E, Korber B, Jeang K T, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1994. A compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Theoretical biology and biophysics. Los Alamos, N.M: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuveut C, Jeang K-T. Recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes with Tat unconstrained by overlapping reading frames reveal residues in Tat important for replication in tissue culture. J Virol. 1996;70:5572–5581. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5572-5581.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsthoorn R C L, Licis N, van Duin J. Leeway and constraints in the forced evolution of a regulatory RNA helix. EMBO J. 1994;13:2660–2668. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsthoorn R C L, van Duin J. Evolutionary reconstruction of a hairpin deleted from the genome of an RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12256–12261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabson A B, Graves B J. Synthesis and processing of viral RNA. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 205–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seed B, Sheen J Y. A simple phase-extraction assay for chloramphenicol acyltransferase activity. Gene. 1988;67:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seigel L J, Ratner L, Josephs S F, Derse D, Feinberg M B, Reyes G R, O’Brien S J, Wong-Staal F. Trans-activation induced by human T-lymphotrophic virus type III (HTLV-III) maps to a viral sequence encoding 58 amino acids and lacks tissue specificity. Virology. 1986;148:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SenGupta D N, Berkhout B, Gatignol A, Zhou A M, Silverman R H. Direct evidence for translational regulation by leader RNA and Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7492–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siderovski D P, Matsuyama T, Frigerio E, Chui S, Min X, Erfle H, Sumner Smith M, Barnett R W, Mak T W. Random mutagenesis of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 trans-activator of transcription (HIV-1 Tat) Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5311–5320. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverman R H, SenGupta D N. Translational regulation by HIV leader RNA, TAT, and interferon-inducible enzymes. J Exp Pathol. 1990;5:69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taddeo B, Carlini F, Verani P, Engelman A. Reversion of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutant at a second site restores enzyme function and virus infectivity. J Virol. 1996;70:8277–8284. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8277-8284.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan R, Brodsky A, Williamson J R, Frankel A D. RNA recognition by HIV-1 Tat and Rev. Semin Virol. 1997;8:186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verhoef K, Bauer M, Meyerhans A, Berkhout B. On the role of the second coding exon of the HIV-1 Tat protein in virus replication and MHC class 1 downregulation. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1553–1559. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verhoef K, Klein A, Berkhout B. Paracrine activation of the HIV-1 LTR promoter by the viral Tat protein is mechanistically similar to trans-activation within a cell. Virology. 1996;225:316–327. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verhoef K, Koper M, Berkhout B. Determination of the minimal amount of Tat activity required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Virology. 1997;237:228–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.Verhoef K, Sanders R W, Fontaine V, Kitajima S, Berkhout B. Evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat promoter by conversion of an NF-κB enhancer element into a GABP binding site. J Virol. 1999;73:1331–1340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1331-1340.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei P, Garber M E, Fang S-M, Fisher W H, Jones K A. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willey R L, Ross E K, Buckler-White A J, Theodore T S, Martin M A. Functional interaction of constant and variable domains of human immunodeficiency virus type gp120. J Virol. 1989;63:3595–3600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3595-3600.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao H, Neuveut C, Benkirane M, Jeang K-T. Interaction of the second coding exon of Tat with human EF-1 delta delineates a mechanism for HIV-1-mediated shut-off of host mRNA translation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;17:384–389. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang X, Gold M O, Tang D N, Lewis D E, Aguilar-Cordova E, Rice A P, Herrmann C H. TAK, an HIV Tat-associated kinase, is a member of the cyclin-dependent family of protein kinases and is induced by activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes and differentiation of promonocytic cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]