Abstract

The simian immunodeficiency virus macC8 (SIVmacC8) variant has been used in a European Community Concerted Action project to study the efficacy and safety of live attenuated SIV vaccines in a large number of macaques. The attenuating deletion in the SIVmacC8 nef-long terminal repeat region encompasses only 12 bp and is “repaired” in a subset of infected animals. It is unknown whether C8-Nef retains some activity. Since it seems important to use only well-characterized deletion mutants in live attenuated vaccine studies, we analyzed the relevance of the deletion, and the duplications and point mutations selected in infected macaques for Nef function in vitro. The deletion, affecting amino acids 143 to 146 (DMYL), resulted in a dramatic decrease in Nef stability and function. The initial 12-bp duplication resulted in efficient Nef expression and an intermediate phenotype in infectivity assays, but it did not significantly restore the ability of Nef to stimulate viral replication and to downmodulate CD4 and class I major histocompatibility complex cell surface expression. The additional substitutions however, which subsequently evolved in vivo, gradually restored these Nef functions. It was noteworthy that coinfection experiments in the T-lymphoid 221 cell line revealed that even SIVmac nef variants carrying the original 12-bp deletion readily outgrew an otherwise isogenic virus containing a 182-bp deletion in the nef gene. Thus, although C8-Nef is unstable and severely impaired in in vitro assays, it maintains some residual activity to stimulate viral replication.

Studies with the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) macaque model have shown that an intact nef gene is critical for efficient replication and the development of AIDS (23). Premature stop codons in the nef open reading frame (ORF) reverted to open forms within the first 2 weeks after infection, resulting in subsequent disease progression. In contrast, nef-deleted forms did not induce disease, showed very low levels of p27 plasma viremia during the acute phase of infection, and an approximately 100- to 1,000-fold reduced cell-associated viral load in the postacute phase (23). Under certain experimental conditions, however, when neonatal monkeys born to unvaccinated mothers are infected with extremely high doses of virus soon after delivery, even nef-defective SIV variants are pathogenic (6, 46). Several studies have demonstrated that some long-term nonprogressors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection harbor nef-defective forms of HIV-1, suggesting that an intact nef gene is of similar importance for human AIDS pathogenesis (13, 25, 36).

Although an intact nef gene has a drastic effect on viral replication in vivo, it is dispensable for efficient replication in most in vitro cell culture systems. It is largely unclear how Nef enhances viral replication in vivo. However, several in vitro activities of Nef that may potentially play a role in the pathogenesis of AIDS have been established. Nef increases the infectivity of viral particles (8, 27, 28, 42). This effect may involve a modification of the virions that results in more-efficient reverse transcription (2, 8, 31, 37). Furthermore, Nef stimulates viral replication in primary lymphocytes and in the T-lymphoid 221 cell line (3, 27, 42). The enhancement of viral particle infectivity or the activation of the large pool of quiescent T lymphocytes in vivo could directly enhance viral spread in vivo. Nef downregulates the cell surface expression of CD4 (1, 15, 17) and of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (9, 38). Downregulation of CD4 may prevent superinfection, promote viral particle release, and impair T-helper-cell functions, and downmodulation of MHC class I molecules may allow evasion of cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) lysis by HIV-1-infected cells.

The important role of nef in pathogenesis has made it an important target for the development of live attenuated AIDS vaccines. Rhesus macaques that were infected with nef-deleted forms of SIVmac239 were fully protected against subsequent challenge with high doses of heterologous pathogenic SIV (11). The efficacy of live attenuated SIV vaccines has been confirmed in a number of independent studies (4, 40, 46). An SIVmac variant containing a large deletion of 182 bp in the nef-unique region was used in the initial study to minimize the risk of reversion and to ensure that nef function is completely disrupted (23). Subsequent studies showed that more than 300 bp of upstream regulatory U3 sequences of the long terminal repeat (LTR) serve mainly as a Nef coding region (21, 24). The multiple deleted SIV mutants currently used for the development of a life attenuated AIDS vaccine in the United States contain deletions of 182 bp in the nef-unique region and of approximately 300 bp in the U3 region (46), thus removing about 66% of the entire nef gene.

In studies of the European Community Concerted Action project designed to examine the mechanism of immune protection and the safety of live attenuated vaccines, a naturally occurring SIVmac variant (C8) has been commonly used (5, 10, 14, 30, 39, 43, 44). The SIVmacC8 clone was derived from the pathogenic SIVmac32H isolate (34). The major difference of the attenuated C8 variant from the pathogenic J5 clone, which was obtained from the same animal infected with the 32H isolate, is an in-frame deletion of just 12 bp in the nef gene (35). In the deduced C8-Nef sequence amino acids (aa) 143 to 146 (DMYL) are missing. It has been shown, that this deletion can be repaired in vivo by a sequence duplication of 12 bp (14, 43, 45). Subsequently, the duplicated region continues to evolve until it is virtually indistinguishable from the functional wild-type sequence (4-aa deletion → EKIL → EIYL → DIYL; wild type, DMYL) (45). The reversions in nef are associated with increased virulence and with the development of immunodeficiency, indicating that this region in nef is important for the full replicative potential in vivo (14, 43, 45).

Studies in a great number of rhesus macaques have established that the SIVmacC8 Nef variant has an attenuated phenotype in vivo (5, 10, 14, 30, 39, 43–45). However, 98.5% of the nef ORF is still intact, and an almost full-length Nef protein could be expressed. It is unknown whether the SIVmacC8 variant is fully attenuated, or whether it expresses a Nef protein that is partly active. Therefore, we have investigated C8-Nef variants containing the original deletion of aa 143 to 146, as well as forms with the predicted repaired sequences EKIL, EKFL, EIYL, DIYL, and DMYL, in well-established in vitro assay systems for Nef function. Protein stability and the ability of Nef to downregulate CD4 and MHC class I surface expression and to enhance virion infectivity and viral replication were impaired by the 4-aa deletion, and functional activity was gradually restored by the duplication and point mutations evolving in infected macaques. However, our results also demonstrate that the C8-nef allele still provides a replicative advantage in a T-lymphoid cell line, suggesting that it maintains some activity in promoting viral replication in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA analysis.

SIV nef genes were amplified by nested PCR (24) directly from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) DNA derived from two macaques infected with the SIVmacC8 clone, Mm1820 (at 15 and 42 weeks postinfection) and Mm1823 (at 15, 20, and 42 weeks postinfection), which had developed signs of immunodeficiency (14, 43). For the first round of PCR amplification, primers p90 (5′-CTATCGAGAGTATACCAGATCC-3′ positions 9230 to 9251) and p41 (5′-TCTGCCAGCCTCTCCGCAGAGCG-3′, positions 10239 to 10261) were used. For the second round of amplification, 5 μl of the 100-μl reaction mixture was used with primers p91 (5′-ATACTCCAGAGGCTCTCTGC-3′, positions 9260 to 9279) and p42 (5′-CGACTGAATACAGAGCGAAATGC-3′, positions 10218 to 10240). The numbering corresponds to the SIVmac239 sequence (33). PCR fragments were gel purified with the Quiaquick gel extraction kit (Diagen, Basel, Switzerland) and sequenced directly or after cloning into an expression vector. Sequencing was performed with the Prism sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and with an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer according to the protocols of the manufacturers. Sequences were analyzed by using the GCG sequence analysis software-package (Genetics Computer Corp.).

Construction of SIVmac239ΔC8 and SIVmacC8 Nef variants.

Site-directed mutagenesis to generate the C8 variants EKIL, EIYL, and DMYL and the deletion mutant 239ΔC8 was performed by spliced overlap extension PCR with mutagenic internal primers (19). Briefly, the env-nef region was amplified with primers P1 (5′-ACCTATCTAGAATATGGGTGGAGC-3′, positions 9333 to 9343; boldface letters indicate an XbaI restriction site) and P3 (5′-TAAGATTCTATGTCTTCTTGC-3′, positions 9737 to 9758). The nef-LTR region was amplified with primers P2 (5′-GTCCCTACGCGTCAGCGAGTTTCCTTCTTG-3′), which binds to bases 10106 to 10124 of the SIVmac239 sequence and contains an MluI restriction site (indicated in boldface), and P4 EKIL (5′-GACATAGAATCTTAGAGAAGATCTTAGAAAAGGAGG-3′, positions 9745 to 9780), P4 EIYL (5′-GACATAGAATCTTAGAGATTTACTTAGAAAAGGAGG-3′, positions 9745 to 9780), P4 DMYL (5′-GACATAGAATCTTAGACATGTACTTAGAAAAGGAGG-3′; positions 9745 to 9780), or P4 ΔC8 (5′-GAAGACATAGAATCTTAGAAAAGGAAGAAGGCATC-3′), which bind to nucleotides 9741 to 9758 and nucleotides 9771 to 9788. Mm1823 K1 recovered at 20 weeks postinfection was used as template to generate the EKIL, EIYL, and DMYL variants. Numbers refer to the published SIVmac239 sequence (33), and mutated positions are underlined. The left- and right-half PCR products were gel purified, mixed at equimolar amounts, subjected to a second PCR with primers P1 SIV XbaI and P2 SIV MluI, and then gel purified. For Nef expression in Jurkat T cells, the nef variants were inserted into a T-cell-specific pCD3-β expression vector by using the unique XbaI and MluI sites. Sequence analysis of the PCR-derived inserts confirmed that only the intended changes were present. To construct the proviral clones, the PCR products were inserted into a modified pBR322 vector containing the full-length SIVmac239 proviral DNA by using the unique NheI and EcoRI sites in the SIV envelope and the vector sequences flanking the 3′ end of the provirus as described elsewhere (26). Two nef-defective controls were used, SIVmac239 nef* contains a premature in-frame TAA stop signal at the 93rd codon of nef and SIVmac239 ΔNef contains a 182-bp deletion in nef (23).

Production of virus stocks.

Generation of virus stocks was performed by the calcium phosphate method essentially as described earlier (12). Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with 5 μg of the full-length proviral SIVmac239 constructs differing only in the nef gene. After overnight incubation, the medium was changed and virus was harvested 24 h later. Viral stocks were aliquoted and frozen at −80°C; p27 antigen concentrations of viral stocks were then quantitated by using a commercial HIV-1–HIV-2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immunogenetics, Zwijndrecht, Belgium).

Cell culture, infectivity, and viral replication.

293T and sMAGI cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Infection of sMAGI cells was performed as described previously (7), except that no DEAE-dextran was added. Viral infectivity was quantitated with the Galacto-Light Plus Chemoluminescence Reporter Assay Kit (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) as recommended by the manufacturer. The Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed T-cell line 221 (3) was maintained in the presence of 100 U of interleukin-2 (IL-2) per ml (Boehringer, Heidelberg, Germany) and 20% FCS, and infections were performed in the presence of 50 U of IL-2 per ml and with 5% FCS as described previously. Supernatants were collected at 3- or 4-day intervals, and virus production was measured by reverse transcriptase assay as described previously (32).

Nef expression in infected CEMx174 cells.

CEMx174 cells were infected with virus containing 10 ng of p27 core antigen derived from transfected 293T cells. When cytopathic effects were observed, cells were pelleted and lysates were generated as described previously (29) and then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 12% polyacrylamide. Nef proteins were detected by Western blot analysis with rabbit anti-Nef-serum. For detection of p27 core protein an anti-gag serum derived from SIVmac p27 hybridoma cells (55-2F12) was used (18). For enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used.

Nef expression in transfected 293T cells.

293T cells were cotransfected with 20 μg of expression plasmid encoding for the different Nef variants and 5 μg of β-galactosidase reporter plasmid. Nef expression was detected by ECL immunoblotting with rabbit anti-Nef serum. β-Galactosidase activity in the lysed cellular extracts was quantitated with the Galacto-Light Plus Chemoluminescence Reporter Assay Kit as recommended by the manufacturer.

Functional analysis.

Dose-response analysis of the effect of Nef on CD4 and MHC class I cell surface expression were assayed as described previously (16, 20, 41). Briefly, the JJK subline of Jurkat T cells was cotransfected by electroporation with a CD20 expression plasmid and various amounts of Nef expression plasmid and carrier DNA. The cell surface expression of CD4, CD20, and MHC class I was analyzed 30 to 36 h after transfection by using an Epics-Elite flow cytometer.

Coinfection of 221 cells.

To detect even modest differences in the replication of SIVmac Nef variants, 2.5 million 221 cells were seeded into 24-well plates, coinfected with two virus stocks (each containing 10 ng of p27 antigen), and cultured in the presence of 50 U of IL-2 per ml. In weekly intervals, 50 μl of cell-free supernatant was used to infect a fresh 221 cell culture, and the infected cells were pelleted to extract genomic DNA. Subsequently, the nef-LTR region was amplified, and the PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose gels and then sequenced as described previously (26).

RESULTS

Repair of the 12-bp deletion in vivo.

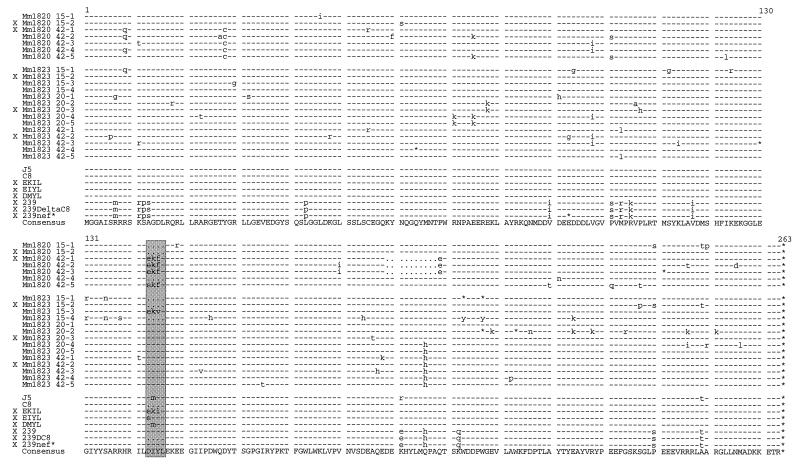

Two of eight rhesus macaques inoculated with the SIVmacC8 variant at the German Primate Center developed signs of immunodeficiency at weeks 38 (Mm1820) and 28 (Mm1823) after infection (14, 43). The other six monkeys, two preinfected for 42 weeks and four preinfected for 22 weeks, resisted challenge with pathogenic SIV and remained asymptomic, with low viral loads, throughout the 2-year observation period (14, 43). We amplified the entire nef genes from sequential PBMC samples drawn from the progressing macaques in order to obtain nef alleles similar to that of the input C8 provirus and repaired forms selected in vivo for functional analysis. No changes in the deleted region were detected in proviral nef sequences recovered from Mm1820 at 15 weeks postinfection. However, four of five nef sequences derived from Mm1820 at 42 weeks postinfection contained an almost perfect 12-bp repeat, substituting the 4-aa deletion with the predicted sequence EKFL (Fig. 1). Three of these four sequences also contained a downstream deletion of 30 bp, predicting deletion of aa 189 to 198. From the second animal, Mm1823, three sequential PBMC samples obtained at 15, 20, and 42 weeks postinfection were analyzed. Three of four nef sequences obtained from the earliest time point still contained the deletion, and one contained an almost perfect 12-bp duplication, with the predicted amino acid sequence EKVL. In contrast, all nef sequences derived from the 20- and 42-weeks-postinfection time points contained an amino acid sequence (DIYL) identical to the SIVmac239 Nef (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the predicted Nef amino acid sequences analyzed. In the upper part of the figure Nef sequences detected in Mm1820 and Mm1823 are shown. The animal number is indicated in the left column. The two-digit numbers in the right column give the number of weeks postinfection, and the number after the dash specifies the individual clone. The predicted amino acid sequences of the J5- and C8-Nef variants; the constructed EKIL-, EIYL-, and DMYL-Nef mutants; and the 239wt, 239ΔC8, and nef* variants are shown underneath. The consensus sequence is given on the bottom line. Symbols: −, identity with the consensus Nef sequence; · , gaps introduced to optimize the alignment; *, a stop signal; and X, nef alleles selected for functional analysis. The deleted region of aa 143 to 146, which is repaired in vivo, is shaded.

Selection of nef alleles for functional analysis.

Two sets of nef alleles were selected to assess the functional relevance of the 4-aa deletion and the duplications and point mutations that evolved in vivo. The first set consisted of representative nef alleles obtained for each time point of sampling from Mm1820 and Mm1823 (Fig. 1). This set included the Mm1820 15-1 Nef, which contains the original 4-aa deletion (1820ΔC8); the Mm1820 42-1Nef, which contains the sequence EKFL in conjunction with a deletion of aa 189 to 198 (1820EKFLΔ10); the Mm1823 15-2Nef, which also contained the 4-aa deletion (1823ΔC8); and the Mm1823 20-3Nef (1823DIYL20) and the 42-2 Nef (1823DIYL42), which contain the same amino acid sequence (DIYL) as the wild-type Nef. The second set included three C8-Nef variants with the predicted repaired sequences EKIL, EIYL, and DMYL that have been observed in a previous study (45). These three variants were constructed by mutagenesis. As an additional control, the region corresponding to the 12-bp deletion in the C8 nef was removed from the nef gene of the pathogenic SIVmac239 clone (239ΔC8) (Fig. 1).

Deletion of aa 143 to 146 reduces Nef steady-state expression levels.

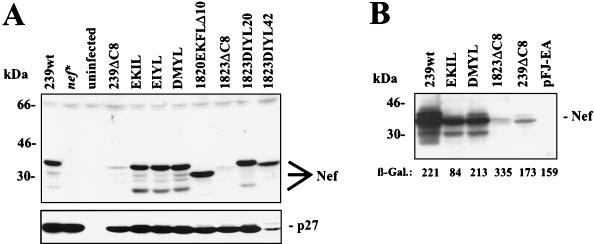

The deletion in the C8-Nef is located in the highly conserved core of the Nef protein and may affect stability. To investigate whether the mutated Nef proteins are expressed in infected cells, the virus stocks generated by transient transfection of 293T cells were used to infect the T/B hybrid CEMx174 cell line. The wild-type (239wt) Nef protein was efficiently synthesized in the infected cells, whereas no Nef-specific signal could be detected in cells infected with the nef* control virus (Fig. 2A). Only low amounts of Nef could be detected in cells infected with the SIVmac239ΔC8 and 1823ΔC8 nef variants carrying the 12-bp deletion. In contrast, comparable amounts of p27 capsid antigen were detected, indicating that all cell cultures were efficiently infected. All six nef alleles containing duplications (EKIL, EIYL, DMYL, 1820EKFLΔ10, 1823DIYL20, and 1823DIYL42) were efficiently expressed (Fig. 2A). To confirm these results in an independent assay, 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids expressing Nef and β-galactosidase. Western blot analysis revealed efficient expression of the 239Nef and the EKIL- and DMYL-Nef proteins (Fig. 2B). In contrast, only very low amounts of the 1823ΔC8 and 239ΔC8 Nef proteins could be detected. The low levels of the 1823ΔC8 and 239ΔC8 Nef proteins in the 293T cells did not result from low transfection efficiencies, since the quantities of β-galactosidase activity in the cellular extracts were comparable to those observed in the cells transfected with the 239Nef expression vector (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Deletion of aa 143 to 146 reduces Nef steady-state expression levels. (A) Detection of viral proteins in CEMx174 cells infected with SIVmac239 containing wild-type or mutant nef genes. CEMx174 cells were infected with viral stocks containing 10 ng of p27 core antigen (derived from 293T cells transiently transfected with the proviral Nef mutant constructs indicated) and cultured until cytopathic effects were observed. Uninfected CEMx174 cells were used as negative control. (B) 293T cells were cotransfected with 20 μg of expression plasmid encoding the indicated Nef proteins and 5 μg of β-galactosidase reporter plasmid. As a negative control, empty pFJ-EA vector was used. ECL immunoblot and quantitation of β-galactosidase activity were performed as described in the Materials and Methods.

Repair of the 12-bp deletion gradually restores the ability of Nef to stimulate viral replication and to enhance virion infectivity.

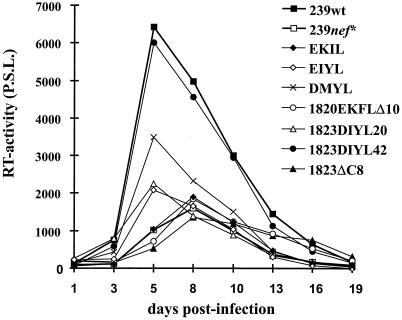

Replication of SIVmac in the Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed T-lymphoid rhesus cell line 221 in the absence of IL-2 depends on the presence of an intact nef gene, and this cell culture system may represent a model for evaluating the ability of Nef to cause lymphoid-cell activation (3). At low levels of IL-2 in the culture medium, Nef variants containing a premature stop codon (239nef*), the 12-bp deletion (Mm1823ΔC8), or the initial duplication (EKIL) replicated very inefficiently (Fig. 3). Variants carrying the 1823DIYL20 and EIYL nef alleles showed marginally increased replication. In contrast, the DMYL-Nef showed an intermediate phenotype, and the form selected late in infection of Mm1823 (1823DIYL42) was fully active (Fig. 3). Results obtained with different preparations of rhesus PBMC, which were infected at a low multiplicity of infection and stimulated 3 or 6 days later, were similar to those obtained with 221 cells but were more variable (data not shown). In contrast, all Nef variants replicated with comparable efficiency in CEMx174 cells (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Growth of SIVmac239 and SIVmacC8 Nef variants in the Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed rhesus monkey T-cell line 221. Cells were propagated in the presence of a low amount of IL-2 (50 U/ml). Virus stocks containing 10 ng of p27 antigen were used for infection, and production was monitored by reverse transcriptase assay at the indicated days postinfection. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. P.S.L. = photo-stimulated light emission.

TABLE 1.

Functional relevance of SIVmacC8 nef mutations

| Nef variant | Sequence (aa 143 to 146)a | Replicationb

|

sMAGI (%) | Activityb

|

Expressionc

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 221 | CEMx174 | CD4 | MHC-I | CEMx174 | 293T | |||

| 239wt | DIYL | +++ | +++ | 100 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| nef* | (DIYL) | (+) | +++ | 10 ± 1 | NDd | ND | − | ND |

| Δnef | (DIYL) | (+) | +++ | 13 ± 2 | NAe | NA | − | NA |

| 239ΔC8 | Deleted | (+) | +++ | 17 ± 2 | ND | ND | (+) | (+) |

| EKIL | EKIL | (+) | +++ | 48 ± 9 | (+) | + | ++ | + |

| EIYL | EIYL | + | +++ | 67 ± 6 | ++ | +++ | ++ | ND |

| DMYL | DMYL | ++ | +++ | 96 ± 2 | ++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| 1820ΔC8 | Deleted | ND | ND | 16 ± 6 | (+) | (+) | ND | ND |

| 1820EKFLΔ10 | EKFL | (+) | +++ | 50 ± 7 | (+) | (+) | ++ | ND |

| 1823ΔC8 | Deleted | (+) | +++ | 23 ± 5 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 1823DIYL20 | DIYL | + | +++ | 63 ± 2 | + | ++ | ++ | ND |

| 1823DIYL42 | DIYL | +++ | +++ | 108 ± 14 | ++ | +++ | ++ | ND |

The Nef amino acid sequences are shown in Fig. 1. The nef gene region coding for aa 143 to 146 is present but is not expressed in the SIVmac239 nef* and Δnef variants; hence, aa 143 to 146 for these two variants are placed in parenthesis.

Replication or activity was as follows: +++, comparable to 239wt; ++, slightly reduced; +, strongly reduced; (+), comparable to nef-defective controls.

Amount of Nef protein detected in infected CEMx174 and transiently transfected 293T cells. Levels of Nef expression were as follows: ++, high; (+), low; and −, not detectable.

ND, not done.

NA, not applicable.

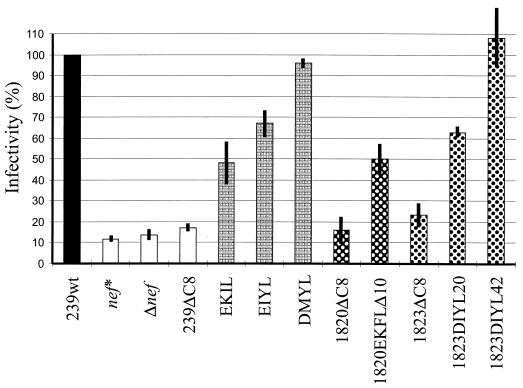

The same virus stocks were used to assess the influence of the 4-aa deletion and the reversions on virion infectivity in sMAGI cells. This cell line is a derivative of a rhesus macaque mammary tumor cell line engineered to express human CD4 and containing an integrated copy of a truncated HIV-1 LTR fused to the β-galactosidase gene (7). As shown in Fig. 4, defects in the nef gene decreased viral infectivity for sMAGI cells by approximately 8- to 10-fold (239nef*, 11.6 ± 1.4%; Δnef, 13.6 ± 2.3%). Nef alleles carrying the 12-bp deletion (239ΔC8, 1820ΔC8, and 1823ΔC8) increased virion infectivity only marginally to 16 to 23% of the level of the SIVmac239wt control (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The initial duplications resulted in an intermediate phenotype, and the additional amino acid substitutions selected in Mm1823 later in infection fully restored the ability of Nef to increase virion infectivity (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Infectivity of SIVmac239 and SIVmacC8 Nef variants. sMAGI cells were infected in triplicate with virus containing 100 ng of p27 antigen derived from transient transfection of 293T cells. β-Galactosidase activities were assayed at 3 days postinfection. The average values relative to wild type obtained from five experiments performed with different virus stocks are shown.

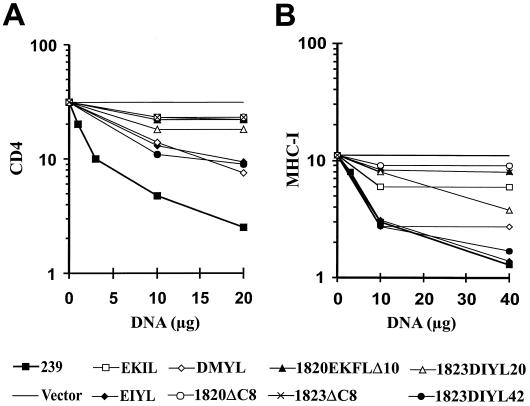

Restoration of CD4 and MHC-I downmodulation.

The nef alleles were cloned into a T-cell-specific expression vector. Transient transfection of the 293Nef expression plasmid into Jurkat T cells resulted in a dose-dependent downregulation of CD4 cell surface expression (Fig. 5A). At the highest amount (20 μg) of expression plasmid, an approximately 20-fold effect was observed. In contrast, nef alleles carrying the 12-bp deletion or an early duplication (EKIL) showed only marginal activity even at the highest concentrations (Fig. 5A). It remains to be elucidated whether the EKIL-Nef is impaired in CD4 internalization or in subsequent sorting to the lysosome. However, nef alleles that evolved later in infection (EIYL, DMYL, and 1823DIYL42) were able to downregulate CD4 surface expression, albeit with reduced efficiency compared to the 239wt Nef. The 1820EKFLΔ10 nef, carrying a downstream deletion of 30 bp in addition to the 12-bp duplication, was inactive in CD4 downregulation.

FIG. 5.

Downmodulation of CD4 (A) and MHC class I (B) surface expression by SIVmacC8 variants. Jurkat T cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of vectors expressing the SIVmac239 and C8 nef genes. CD4 and MHC class I expression on the cell surface was determined by flow-cytometric analysis.

Similar to the results obtained upon CD4 downmodulation, the 1823ΔC8 and 1820EKFLΔ10 Nef proteins were unable to downregulate MHC-I surface expression (Fig. 5B). In contrast, EIYL, DMYL, and 1823DIYL42 showed an activity comparable to 239wt Nef and resulted in a reduction of MHC-I surface expression of up to 10-fold. The EKIL and 1823DIYL20 nef alleles showed an intermediate activity (Fig. 5B).

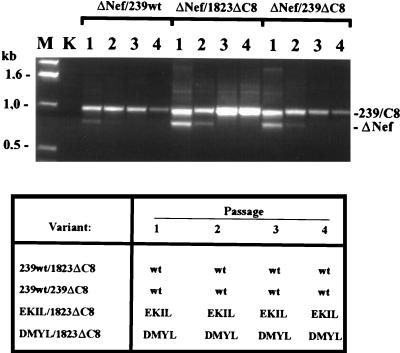

The 12-bp deletion does not completely disrupt the ability of Nef to increase viral replication in 221 cells.

Our results showed that deletion of aa 143 to 146 impairs Nef expression and has pleiotropic effects on in vitro activities (summarized in Table 1). However, it seemed that even the nef alleles containing the 12-bp deletion still maintained some marginal activity in infectivity enhancement as well as in CD4 and MHC-I downmodulation. In particular, viral replication and infectivity assays are somewhat variable and modest differences are difficult to demonstrate. To detect subtle differences in replicative capacity in vitro, 221 cells were coinfected with SIVmacC8-Nef variants and viruses carrying a deleted or a full-length nef. As shown in Fig. 6, the SIVmac239wt variant rapidly outgrew the isogenic nef-deleted forms. After coinfection of 221 cells with SIVmac239 ΔNef and the 239ΔC8 or 1823ΔC8 Nef variants, both the forms carrying the 12-bp deletion and the 182-bp deletion in nef were detected after the first passage (Fig. 6, upper panel). After the second passage, however, the 12-bp deletion mutants became predominant, and for the last two passages the nef allele with the 182-bp deletion was not detected (Fig. 6). In contrast, when 221 cells were coinfected with SIVmac239wt and the forms with the 12-bp deletions, only the wild-type 239nef could be detected by direct sequence analysis of PCR fragments (Fig. 6, lower panel). Similarly Nef variants containing duplications (EKIL and DMYL) outgrew the virus containing the nef gene with the original 12-bp deletion. These results show that the variants containing the duplications selected for in vivo have a higher replicative potential than the C8-Nef variant. However, even the nef alleles carrying the original 12-bp deletion maintained some residual activity to stimulate SIV replication in this T-lymphoid cell line.

FIG. 6.

Coinfection of 221 cells with SIVmac239 and SIVmacC8 Nef variants. 221 cells were infected with equal amounts of p27 antigen (10 ng) of the mutants indicated. At weekly intervals the supernatant was used to infect a new culture (passages 1 to 4), and the cells were used for extraction of genomic DNA. The nef gene was amplified from 221 cells coinfected with the ΔNef variant and the other variants indicated, and the PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel (upper panel). In the lower panel, the results of direct sequence analysis of DNA fragments spanning nef are shown. Sequence analysis was performed as described previously (26). Levels of nef alleles carrying the ΔC8 deletion were always below 10%. The results are shown for 221 cells that were grown in the presence of 50 U of IL-2 per ml. Abbreviations: K, uninfected CEMx174 cells; ΔNef, SIVmac239 ΔNef.

DISCUSSION

We have found that the deletion of aa 143 to 146 in SIVmacC8-Nef, which clearly attenuates SIV replication in vivo (4, 5, 10, 14, 30, 34, 39, 43–45), disrupts Nef function in vitro. The deletion also impaired Nef expression, thus explaining the pleiotropic effects on functional activity. The early 12-bp duplications (EKFL and EKIL) selected in vivo resulted in stable Nef protein expression but had only marginally restorative effects on the ability of Nef to stimulate viral infectivity and replication and to downmodulate CD4 and MHC-I. This indicates that the deleted region in Nef is important for proper folding of the Nef molecule. In vivo, additional amino acid substitutions were selected and the evolution of the 4-aa region to sequences similar or identical to that present in the Nef proteins of the pathogenic SIVmac239 and SIVmacJ5 variants was associated with increasing viral loads and disease progression (14, 43, 45). In agreement with the selective pressure observed in vivo, functional analysis revealed that these amino acid substitutions gradually almost fully restored all of the in vitro Nef activities investigated. The restorative effects of the various duplications varied slightly between the different in vitro assay systems. This can best be compared for the constructed EKIL-, EIYL-, and DMYL-Nef variants that are otherwise isogenic to each other and to the C8-Nef. The initial duplication (EKIL) had a moderate restorative effect on infectivity and on MHC-I downregulation but not on the downmodulation of CD4. A replicative advantage of the EKIL-Nef variant, compared to the C8-Nef variant, in 221 cells could only be demonstrated by coinfection experiments. With the exception of two amino acid substitutions, K181R and A249T, the constructed DMYL-Nef is identical to that of the J5 clone but differs at 15 aa positions from the 239Nef (Fig. 1). The DMYL-Nef showed an activity comparable to the 239Nef in the enhancement of infectivity and in MHC-I downregulation but was less active in CD4 downmodulation and in its ability to stimulate viral replication. In contrast to the highly pathogenic SIVmac239 clone (22), the J5 virus has been reported to be only moderately pathogenic (35). It seems possible that the higher pathogenicity of SIVmac239 is due to a more active nef allele.

Our results show that even the 12-bp deletion nef variants have some residual activity to stimulate viral replication, although only very low amounts of the deleted Nef protein could be detected in infected cells. Similarly, these variants seemed to retain some marginal activity in other in vitro assay systems for Nef function. These findings may explain why, in contrast to macaques infected with SIV nef variants containing a 182-bp deletion in nef (24), no additional large deletions in the U3 region have been found in macaques infected with the C8 variant. The residual activity may provide a selective advantage over forms in which the nef gene is completely disrupted. It has been described that the C8-Nef can be detected in infected cells (45) and that it can induce CTL responses (14). Macaques infected with the C8 variant seem to be more rapidly protected against challenge with pathogenic SIV than are animals vaccinated with the SIVmac239 variant containing the 182-bp deletion in nef (30, 43). Since protection is linked to the replicative capacity of the vaccine virus (46), these previous results also suggested that the C8-Nef may not be entirely inactive.

In one of the animals infected with the C8-Nef variant (Mm1823) our findings were similar to those of Whatmore et al. (45). They noted an almost perfect 12-bp duplication event and a subsequent evolution to forms that are indistinguishable from the wild-type Nef. In this animal functional Nef activity was also fully restored, and most nef genes detected at later time points were intact. Mm1823 showed declining CD4/CD8 ratios by between 20 and 32 weeks postinfection and progressing peripheral lymphadenopathy beginning at week 42 (14, 43). The 1823DIYL20 Nef, which was obtained when the animal started to develop signs of immunodeficiency (14, 43), showed an intermediate phenotype in in vitro assays for Nef function (summarized in Table 1). The 1823DIYL42 nef allele, obtained when more severe clinical alterations were observed, was almost fully active. This form contains the same 4-aa repair as the 1823DIYL20 Nef, but it differs at 8 other amino acid positions (Fig. 1). Thus, the higher functional activity of the 1823DIYL42 Nef may be due to the presence of these additional amino acid substitutions. In particular, the Q196H change may be relevant for Nef function and increased viral pathogenicity, since this change is also present in the Nef protein of the highly pathogenic SIVmac239 Nef and has been observed in other C8-infected macaques (45). Surprisingly, three of four “repaired” nef alleles derived from the second animal, Mm1820, at 42 weeks postinfection contained a downstream deletion of 30 bp, predicting deletion of Nef aa 189 to 198. We have not observed similar in-frame deletions in the nef gene of 14 SIVmac239wt-infected animals (25a). However, Sharpe et al. (39) have observed a similar deletion of 33 bp (removing aa 193 to 203), which evolved after the 12-bp duplication. The nef allele carrying the 30-bp deletion together with a 12-bp duplication (1820EKFLΔ10) was largely inactive in functional assays, and it remains to be elucidated why short in-frame deletions close to the 3′ end of the nef gene are selected in some animals infected with the C8 variant. Mm1823 developed more-severe alterations than did Mm1820 that were indicative of an immunodeficiency (14, 43). Our observation that Nef function was fully restored in Mm1823, but not in Mm1820, is in agreement with these previous findings.

In summary, we have shown than an attenuated SIVmac variant that has been broadly used for studies on live attenuated SIV vaccines throughout Europe contains a nef gene that is largely defective in in vitro assay systems. In addition to the previous observation that the 12-bp deletion can be repaired to forms that are indistinguishable from wild-type nef alleles (and thus also from the challenge virus), our finding that the C8-Nef still has some residual activity, at least in the stimulation of viral replication, raises even more questions concerning the use of this variant for studies of live attenuated AIDS vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mandy Krumbiegel for technical assistance, Bernhard Fleckenstein for support and encouragement, and Klaus Überla for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Martin P. Cranage and E. W. Rud for providing the C8 virus, Julie Overbaugh and Bryce Chackerian for sMAGI cells, and Lou Alexander and Ronald C. Desrosiers for the 221 cells. The SIVmac p27 hybridoma cells (55-2F12) were kindly provided by Niels Petersen through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program.

This work was supported by the Public Health service grant TA-42561 to J.S., the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Wilhelm-Sander Stiftung, and the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau N R, Lenburg M E, Trono D. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1994;76:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C, Trono D. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1995;69:5048–5056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5048-5056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander L, Du Z, Rosenzweig M, Jung J J, Desrosiers R C. A role for natural SIV and HIV-1 nef alleles in lymphocyte activation. J Virol. 1997;71:6094–6099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6094-6099.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almond N, Kent K, Cranage M, Rud E, Clarke B, Stott E J. Protection by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques against challenge with virus-infected cells. Lancet. 1995;345:1342–1344. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almond N, Rose J, Sangster R, Silvera P, Stebbings R, Walker B, Stott E J. Mechanisms of protection induced by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. Protection cannot be transferred with immune serum. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1919–1922. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba T W, Jeong Y S, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, Ruprecht R M. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science. 1995;267:1820–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.7892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chackerian B, Haigwood N L, Overbaugh J. Characterization of a CD4-expressing macaque cell line that can detect virus after a single replication cycle and can be infected by diverse simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. Virology. 1995;213:386–394. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowers M Y, Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Fitch N J, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. Optimal infectivity in vitro of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires an intact nef gene. J Virol. 1994;68:2906–2914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2906-2914.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins K L, Chen B K, Kalams S A, Walker B D, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:397–401. doi: 10.1038/34929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cranage M P, Whatmore A M, Sharpe S A, Cook N, Polyanskaya N, Leech S, Smith J D, Rud E W, Dennis M J, Hall G A. Macaques infected with live attenuated SIVmac are protected against superinfection via the rectal mucosa. Virology. 1997;229:143–154. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel M D, Kirchhoff F, Czajak S C, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dittmer U, Nisslein T, Bodemer W, Petry H, Sauermann U, Stahl-Hennig C, Hunsmann G. Cellular immune response of rhesus monkeys infected with a partially attenuated nef deletion mutant of the simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1995;212:392–397. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350:508–511. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg M E, Iafrate A J, Skowronski J. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class I MHC complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2777–2789. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guy B, Kieny M P, Riviere Y, Le Peuch C, Dott K, Girard M, Montagnier L, Lecocq J P. HIV F/3′ orf encodes a phosphorylated GTP-binding protein resembling an oncogene product. Nature. 1987;330:266–269. doi: 10.1038/330266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J R, Sutjipto S, Marx P A, Pedersen N C. Shared antigenic epitopes of the major core proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. J Med Primatol. 1992;21:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton R M, Hunt H D, Ho S N, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iafrate A J, Bronson S, Skowronski J. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:673–684. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilyinskii P O, Daniel M D, Simon M A, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. The role of upstream U3 sequences in the pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus-induced AIDS in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1994;68:5933–5944. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5933-5944.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kestler H W, Kodama T, Ringler D J, Marthas M, Pedersen N, Lackner A, Regier D, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kestler H W, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchhoff F, Kestler H W, Desrosiers R C. Upstream U3 sequences in SIV are selectively deleted in vivo in the absence of nef function. J Virol. 1994;68:2031–2037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.2031-2037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term, nonprogressing survivor of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Kirchhoff, F., and C. Stahl-Hennig. Unpublished observations.

- 26.Lang S M, Iafrate A J, Stahl-Hennig C, Kuhn E M, Nisslein T, Haupt M, Hunsmann G, Skowronski J, Kirchhoff F. Association of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef with cellular serine/threonine kinases is dispensable for the development of AIDS in rhesus macaques. Nat Med. 1997;3:860–865. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller M D, Warmerdam M T, Gaston I, Greene W C, Feinberg M B. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–114. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M D, Warmerdam M T, Page K A, Feinberg M B, Greene W C. Expression of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) nef gene during HIV-1 production increases progeny particle infectivity independently of gp160 or viral entry. J Virol. 1995;69:579–584. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.579-584.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison H G, Kirchhoff F, Desrosiers R C. Effects of mutations in constant regions 3 and 4 of envelope of simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1995;210:448–455. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norley S, Beer B, Binninger-Schinzel D, Cosma C, Kurth R. Protection from pathogenic SIVmac challenge following short-term infection with a nef-deficient attenuated virus. Virology. 1996;219:195–205. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandori M W, Fitch N J, Craig H M, Richman D D, Spina C A, Guatelli J C. Producer-cell modification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Nef is a virion protein. J Virol. 1996;70:4283–4290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4283-4290.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potts B J. “Mini” reverse transcriptase assay. In: Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton; 1990. pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of SIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1989;6:1221–1231. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rud E W, Jon J R, Larder B A, Clarke B E, Cook N, Cranage M P. Infectious molecular clone of SIVmac32H: nef deletion controls ability to reisolate virus from rhesus macaques. Vaccines. 1992;92:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rud E W, Cranage M, Yon J, Quirk J, Ogilvie L, Cook N, Webster S, Dennis M, Clarke B E. Molecular and biological characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus macaque strain 32H proviral clones containing nef size variants. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:529–543. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-3-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvi R, Garbuglia A R, Di Caro A, Pulciani S, Montella F, Benedetto A. Grossly defective nef gene sequences in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-seropositive long-term nonprogressor. J Virol. 1998;72:3646–3657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3646-3657.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Danos O, Heard J M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef increases the efficiency of reverse transcription in the infected cell. J Virol. 1995;69:4053–4059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4053-4059.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard J M. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharpe S A, Whatmore A M, Hall G A, Cranage M P. Macaques infected with attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus resist superinfection with virulence-revertant virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1923–1927. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibata R, Siemon C, Czajak S C, Desrosiers R C, Martin M A. Live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines elicit potent resistance against a challenge with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric virus. J Virol. 1997;71:8141–8148. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8141-8148.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skowronski J, Mariani R. Transient assay for Nef-induced down-regulation of CD4 antigen expression on the cell surface. In: Rickwood D, Hames B D, Karn J, editors. HIV-1: a practical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press/Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Chowers M Y, Guatelli J C, Richman D D. The importance of nef in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication from primary quiescent CD4 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:115–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stahl-Hennig C, Dittmer U, Nisslein T, Petry H, Jurkiewicz E, Fuchs D, Wachter H, Matz-Rensing K, Kuhn E M, Kaup F J, Rud E W, Hunsmann G. Rapid development of vaccine protection in macaques by live-attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2969–2981. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Titti F, Sernicola L, Geraci A, Panzini G, Di-Fabio S, Belli R, Monardo F, Borsetti A, Maggiorella M T, Koanga-Mogtomo M, Corrias F, Zamarchi R, Amadori A, Chieco-Bianchi L, Verani P. Live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus prevents super-infection by cloned SIVmac251 in cynomolgus monkeys. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2529–2539. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-10-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whatmore A M, Cook N, Hall G A, Sharpe S, Rud E W, Cranage M P. Repair and evolution of nef in vivo modulates simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Virol. 1995;69:5117–5123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5117-5123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyand M S, Manson K H, Garcia-Moll M, Monfiori D, Desrosiers R C. Vaccine protection by a triple deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1996;70:3724–3733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3724-3733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]