Abstract

Background & Aims

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a telomere biology disorder caused primarily by mutations in the DKC1 gene. Patients with DC and related telomeropathies resulting from premature telomere dysfunction experience multiorgan failure. In the liver, DC patients present with nodular hyperplasia, steatosis, inflammation, and cirrhosis. However, the mechanism responsible for telomere dysfunction–induced liver disease remains unclear.

Methods

We used isogenic human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) harboring a causal DC mutation in DKC1 or a CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9)–corrected control allele to model DC liver pathologies. We differentiated these iPSCs into hepatocytes (HEPs) or hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) followed by generation of genotype-admixed hepatostellate organoids. Single-cell transcriptomics were applied to hepatostellate organoids to understand cell type–specific genotype-phenotype relationships.

Results

Directed differentiation of iPSCs into HEPs and stellate cells and subsequent hepatostellate organoid formation revealed a dominant phenotype in the parenchyma, with DC HEPs becoming hyperplastic and also eliciting a pathogenic hyperplastic, proinflammatory response in stellate cells independent of stellate cell genotype. Pathogenic phenotypes in DKC1-mutant HEPs and hepatostellate organoids could be rescued via suppression of serine/threonine kinase AKT (protein kinase B) activity, a central regulator of MYC-driven hyperplasia downstream of DKC1 mutation.

Conclusions

Isogenic iPSC-derived admixed hepatostellate organoids offer insight into the liver pathologies in telomeropathies and provide a framework for evaluating emerging therapies.

Keywords: Dyskeratosis Congenita, Telomere, DKC1, Hepatocyte, Stellate Cell, Organoid, Liver Organoid, iPS Cell

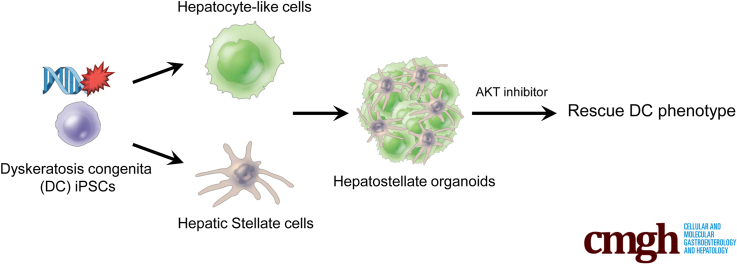

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Critical telomere shortening in dyskeratosis congenita hepatocytes induces cell-autonomous hyperplasia and elicits activation of hepatic stellate cells in hepatostellate organoids. Dyskeratosis congenita phenotypes can be rescued by serine/threonine kinase AKT (protein kinase B) inhibition.

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a telomere biology disorder (telomeropathy) initially characterized by a clinical triad of pathologies including nail dystrophy, oral leukoplakia, and abnormal skin pigmentation associated with bone marrow failure. DC frequently presents with additional pathologies including lung and liver fibrosis, intestinal barrier failure and inflammation, and osteopenia.1, 2, 3 DC is caused by mutations in various genes involved in telomere capping or elongation, most commonly X-linked DKC1. DKC1 encodes dyskerin—an integral component of the telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex.4,5 DC patients with loss-of-function mutations in DKC1 have shorter telomeres than age-matched control subjects,6 and human pluripotent cell–based DC models harboring mutations in DKC1 exhibit attenuated telomerase enzymatic activity, shorter telomeres, and hallmarks of telomere dysfunction.3,7,8 Although dyskerin has additional roles in RNA pseudouridylation and ribosomal function,2 its dysfunction in telomere elongation is causal in DC, as DC phenotypes caused by DKC1 mutations are consistent with phenotypes caused by mutations in at least 10 other genes whose shared function is telomere maintenance. Furthermore, any ribosomal defects are mild and not correlated with the severity of DC phenotypes.9 Moreover, restoration of telomere capping is sufficient to rescue DC phenotypes.3,10, 11, 12

In highly proliferating tissues such as the bone marrow and intestinal epithelium, critical telomere shortening causes stem cell failure. However, lower turnover tissues such as the lung and liver present primarily with fibrosis.4 In the liver, DC patients frequently exhibit inflammation, steatosis, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia, all of which are linked to cirrhosis.13, 14, 15 Human studies also have shown frequent telomerase mutations and critically short telomeres in otherwise idiopathic cirrhosis patients.16,17 Consistent with a causal role for telomere dysfunction in these liver phenotypes, telomerase RNA component (Terc) knockout mice exhibit cirrhosis upon carbon tetrachloride injury, and subsequent adenoviral delivery of Terc is sufficient to reactivate telomerase, inhibit telomere shortening, and prevent cirrhosis.18 Thus, cumulative evidence indicates that telomere failure is causal for liver pathologies associated with DC and potentially more broadly in idiopathic cirrhosis patients without a diagnosed telomeropathy.

Currently, no therapeutic options address liver phenotypes associated with DC. This is due, in part, to a lack of understanding of the cellular basis and molecular mechanisms underlying the observed phenotypes. Interestingly, in cirrhosis patients, telomere shortening and senescence are limited to hepatocytes (HEPs) and are not observed in nonparenchymal cell types such as stellate cells and lymphocytes,19 suggesting that cirrhotic progression may result from HEP-specific telomere dysfunction.

Experiments in human embryonic stem (ES) cell–derived HEPs harboring DKC1 mutations revealed aberrant P53 activation in response to telomere shortening, leading to HNF4α suppression and impaired HEP differentiation.7 Counterintuitively, telomere dysfunction and the subsequent P53 response in ES cell–derived HEPs does not elicit apoptosis or senescence, but rather results in hyperproliferation.7 This indicates that telomere capping plays an important cell-autonomous role in HEPs. However, cirrhosis is largely driven by the pathologic activation of nonparenchymal cells, specifically hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which undergo proliferative expansion and contribute to inflammation and fibrotic scar formation.20 Whether telomere dysfunction cell-autonomously affects stellate cells or whether telomere dysfunction in HEPs promotes a pathogenic response in stellate cells remains unknown.

Here, we model liver phenotypes associated with telomere dysfunction using DC patient–derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and isogenic control cells with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology–directed repair of the disease-causing DKC1 mutation. Differentiation of these cells into HEPs or HSCs reveals that telomere dysfunction primarily affects HEPs. We develop an admixed hepatostellate organoid model that further reveals that mutant HEPs exert dominant effects on HSCs, inducing hallmarks of stellate cell activation regardless of stellate cell genotype. Interestingly, mutant hepatostellate organoids also contain PLVAP+ endothelial cells reminiscent of scar-associated endothelium observed in non-DC cirrhosis patients.21 Ultimately, we demonstrate that inhibition of serine/threonine kinase AKT (protein kinase B)—a central signaling hub involved in HEP maturation and function—can rescue the liver pathologies in both iPSC-derived HEPs and 3-dimensional (3D) hepatostellate organoids. Our findings provide insight into the mechanisms underlying and potential treatments for liver disease driven by telomere dysfunction.

Results

Generation and Characterization of DC Patient–Derived iPS Cell–Based HEP and HSC Models

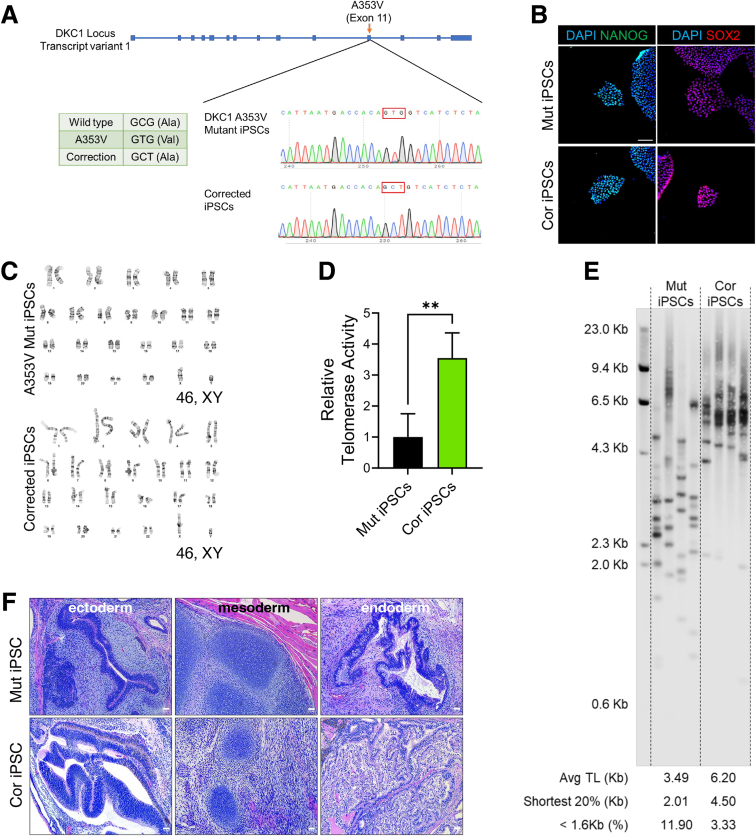

We initially corrected a DKC1 A353V mutation (which accounts for approximately 40% of X-linked DC) in DC patient–derived iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9-driven homology–directed repair (Figure 1A).11 We verified that the resulting isogenic mutant and corrected iPSCs maintained expression of pluripotency markers and remained karyotypically normal (Figure 1B and C). As expected, correction of the DKC1 mutation resulted in higher telomerase activity and longer telomere length compared with isogenic mutants (Figure 1D and E). Complete loss of telomerase activity is incompatible with pluripotency; thus, we examined the developmental potential of isogenic iPSC lines via teratoma formation assays. Mutant iPSCs retained the ability to form ectodermal, endodermal, and mesodermal derivatives, consistent with the hypomorphic DKC1 mutations reducing but not eliminating telomerase activity (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Generation of isogenic iPSC lines. (A) Sanger DNA sequencing tracks showing correction of the DKC1 mutation in patient-derived iPSCs. The PAM sequence for the RNA was mutated by using a GCT codon at A353 instead of the wild-type codon (GCG) for the correction. (B) Immunostaining of pluripotency markers Nanog and Sox2 in the isogenic iPSC pair. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Karyotyping of metaphase iPSCs. (D) Telomerase activity in iPSCs measured by qTRAP assay (n = 3). ∗∗P < .01. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (E) Telomere length in iPSCs measured by TeSLA. (F) Teratoma formation from iPSCs showing ectodermal derivatives (neuroepithelium), mesodermal derivatives (cartilaginous condensations), and endodermal derivatives (glandular/secretory epithelium) in both corrected and mutant tumors. Scale bar: 50 μm. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

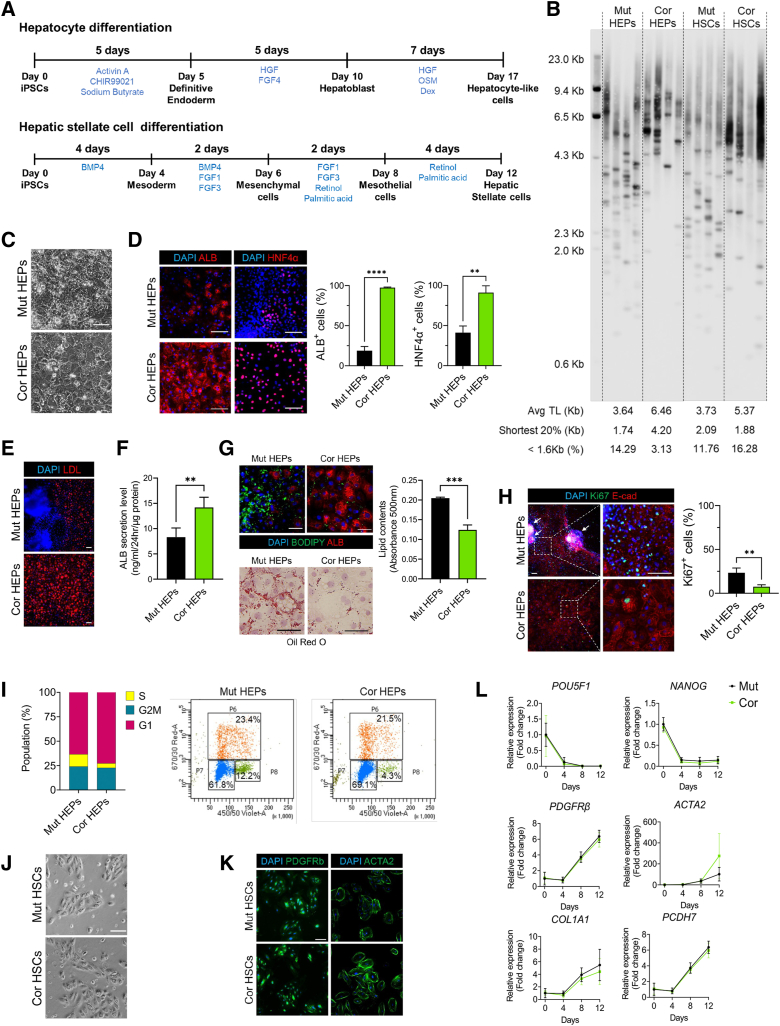

To model hepatic phenotypes associated with DC, iPSCs were differentiated into HEP-like cells using established protocols22,23 with some modification (Figure 2A). At the final stage of differentiation, corrected HEPs exhibited longer telomeres relative to isogenic mutants (Figure 2B). Corrected HEPs exhibited typical HEP morphology (large and polygonal), while mutant HEPs were smaller with unclear boundaries (Figure 2C). We assessed hepatic differentiation and function in these cultures. Mutant HEPs had fewer HNF4α-positive (the master HEP transcriptional regulator) and albumin (ALB)-positive cells and decreased hepatic function (ALB secretion and low-density lipoprotein uptake) (Figure 2D–F). As prior studies reported that telomerase mutations can induce steatosis,14,18 we also confirmed that mutant HEP cultures exhibited significantly higher lipid accumulation (Figure 2G). Interestingly, cell-dense, nodule-like structures developed in mutant cultures (Figure 2E and H). Nodular hyperplasia is reported in human DC patients,13,24 and assessing proliferation revealed that mutant HEPs were hyperplastic relative to isogenic control cells (Figure 2H and I). These results indicate that telomerase dysfunction results in disrupted hepatic development and abnormal HEP proliferation. Together, our findings are largely consistent with a recent study modeling DC phenotypes in human ES cell–derived HEPs.7

Figure 2.

Differentiation of HEPs and HSCs from isogenic DC iPSCs. (A) Schematic of differentiation scheme for iPSC-derived HEPs and HSCs. (B) Telomere length measurement in HEPs and HSCs by TeSLA. (C) Representative morphologic differences in HEPs on day 17. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence images of ALB and HNF4α in HEPs on day 17. Scale bar: 100 μm. Graphs showing quantification of images (n = 3). (E) Acetylated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake assay in HEPs. Scale bar: 100 μm. (F) ALB secretion by HEPs was analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (n = 4). (G) Lipid accumulation in HEPs analyzed by BODIPY staining and Oil Red O staining. Scale bars: 100 μm. (H) Ki67 and E-cadherin staining in HEPs. White arrows indicate nodule-like structures, quantified at right (n = 3). Scale bar: 100 μm. (I) EdU cell proliferation assays using flow cytometry analysis. (J) Representative morphology of HSCs during the expansion stage (p1). Scale bar: 100 μm. (K) Staining of HSC cultures for stellate cell markers PDGFRβ and ACTA2. Scale bar: 100 μm. (L) qRT-PCR analysis of pluripotency markers and stellate cell marker genes in HSC cultures. For all panels, error bars indicate means ± SD. ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant; TL, telomere length.

Next, we sought to determine if the DKC1 mutation also affects the development of nonparenchymal liver cells. We induced differentiation of the isogenic iPSCs into HSCs following a recently published protocol (Figure 2A).25 Mutant HSCs had shorter telomeres than corrected HSCs, but these differences were less dramatic than those observed in HEPs (Figure 2B). In contrast to the clear pathologies observed during hepatic differentiation, HSC differentiation revealed no apparent phenotypic differences between the mutant and corrected cultures (Figure 2J–L), suggesting that the DKC1 mutation and consequent telomere shortening primarily affect the parenchymal HEPs.

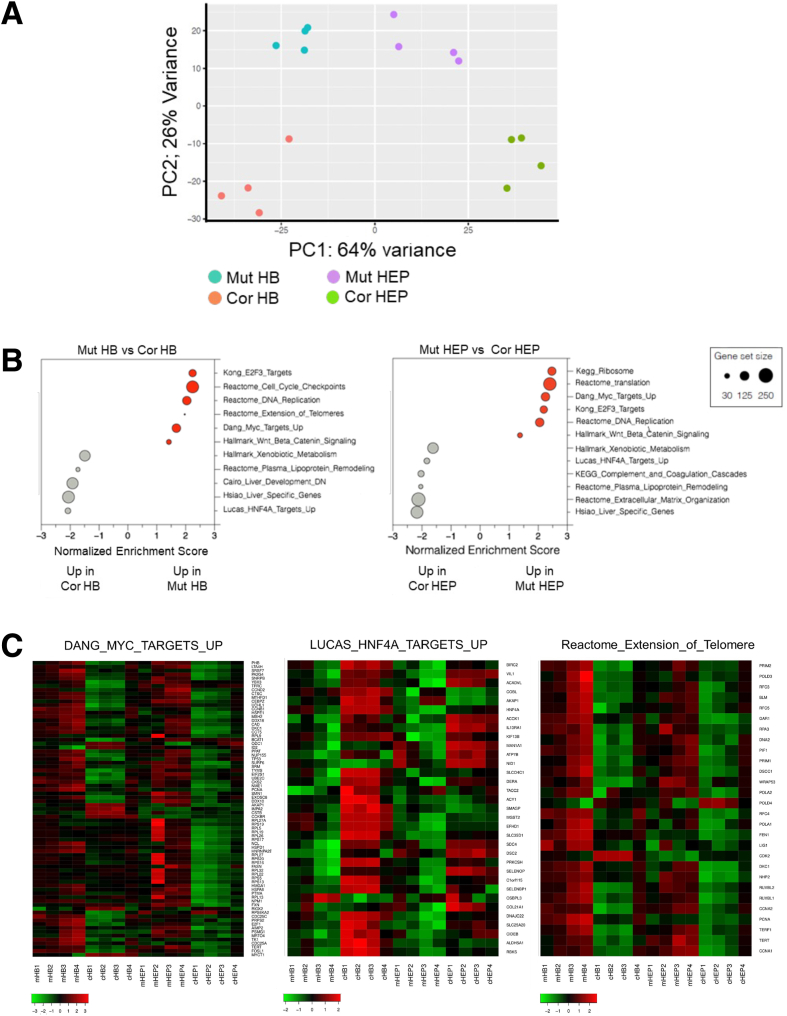

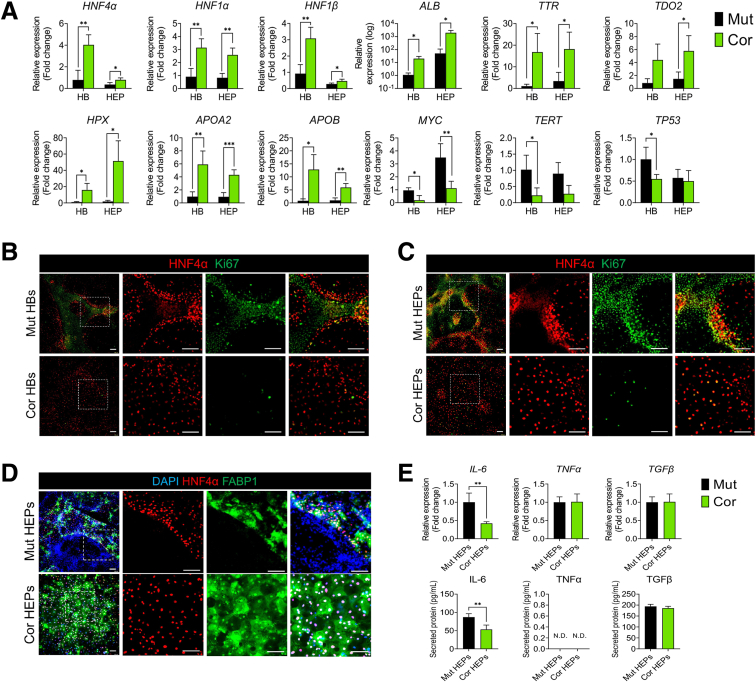

We next performed bulk RNA sequencing with hepatoblast (HB) and HEP-stage cultures. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the primary (PC1) transcriptional differences are driven by differentiation state, while secondary (PC2) differences are driven by genotype (Figure 3A). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that in both mutant HBs and HEPs, genes involved in cell proliferation and translation are highly upregulated (Figure 3B, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). In particular, MYC target genes were highly expressed in mutant cultures, while HNF4α target genes were strongly suppressed (Figure 3B and C). Conversely, corrected cultures exhibited enrichment for gene sets related to hepatic differentiation and function. This was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), in which HNF4α, additional HEP nuclear factors, HEP functional markers (ALB, TTR, and TDO2), and apolipoproteins are significantly suppressed in mutant HBs and HEPs relative to corrected control cells (Figure 4A). We confirmed that MYC and its target genes (including TERT and TP53) were more highly expressed in mutants (Figure 4A). Immunofluorescence revealed an inverse correlation between proliferating cells and differentiated cells in the mutant cultures (HNF4α/FABP1-positive cells are Ki67-negative and vice versa), suggesting that proliferation and proper HEP differentiation are mutually exclusive (Figure 4B–D). HNF4α is a master regulator of liver development, in which it regulates target gene expression in a manner antagonistic to MYC.26 Our data suggest that the inability of mutant cells to suppress MYC underlies their failure to activate HNF4α and undergo proper HEP differentiation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of HBs and HEPs derived from isogenic DC iPSCs. (A) Comparison of global gene expression in HBs and HEPs by PCA of transcriptome profiles (n = 4). (B) GSEA of differentially expressed genes between mutant and corrected in HB and HEPs. Gray shows enrichment in mutant HBs or HEPs; red shows enrichment in corrected HBs or HEPs. (C) Heatmaps showing differences in gene expression within indicated gene sets during hepatic differentiation. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

Figure 4.

Abnormal hepatic differentiation in DKC1-mutant cultures. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of hepatic transcription factors, hepatic marker genes, MYC, and MYC target genes (n = 4). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (B) HNF4α and Ki67 staining of mutant HBs and corrected HBs. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) HNF4α and Ki67 staining of mutant HEPs and corrected HEPs. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Immunostaining of HNF4α and FABP1 in mutant HEPs and corrected HEPs. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Expression of cytokines in HEPs analyzed by qRT-PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (n = 4). ∗∗P < .01. Error bars indicate means ± SD. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

Analysis of proinflammatory cytokine expression linked to liver fibrosis revealed high interleukin 6 (IL-6) expression in mutant HEPs but no differences in tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and transforming growth factor β (TFGβ) expression (Figure 4E). Taken together, these results further confirm that DKC1 mutation induces abnormal hepatic differentiation and that these abnormal HEPs may signal to the microenvironment to promote liver pathologies.

Modeling DC Liver Pathologies in Hepatostellate Organoids

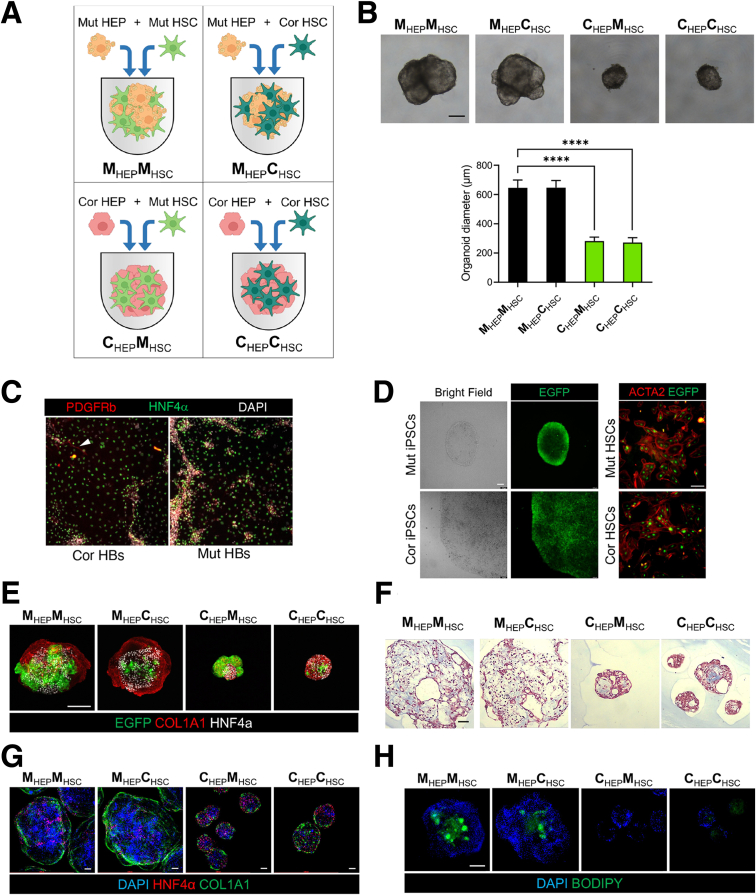

Given that DC mutant HEPs exhibit aberrant differentiation, hyperproliferation, and produce proinflammatory IL-6, we sought to model the hepatic phenotypes observed in DC patients that involve nonparenchymal cell types, particularly HSCs. We therefore set out to generate hepatostellate organoids by admixing HEPs::HSCs or HBs::HSCs at a 5:1 ratio to approximate the HEP::stellate cell ratio found in vivo.27 While HEP::HSC organoids failed to coalesce and grow as 3D structures, HB::HSC mixtures successfully generated 3D hepatostellate organoids followed by final differentiation into mature HEPs (hereafter referred to as HEP::HSC organoids) (Figure 5A and B). To evaluate potential non–cell-autonomous effects of the DKC1 mutation, we generated HEP::HSC organoids of different genotypes (Mut::Cor, Mut::Mut, Cor::Cor, and Cor::Mut) (Figure 5A). To ensure that HSCs in hepatostellate organoids were derived from the HSC directed differentiation cultures and were not off-target cells appearing in HB/HEP cultures, we examined 2-dimensional (2D) HB cultures prior to forming admixed organoids for the presence of stellate cells and found few, if any (Figure 5C). Additionally, to easily distinguish cells derived from HEP differentiation from those derived from HSC differentiation in the admixed organoids, we targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) into the AAVS1 locus of iPSCs28 and then induced HSC differentiation and hepatostellate organoid formation (Figure 5D). We confirmed that eGFP-expressing HSCs were clearly distinguishable from HEPs, and mutant HSCs appeared consistently larger and/or more abundant in admixed organoids (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Modeling DC-associated liver phenotypes in hepatostellate organoids. (A) Schematic depicting the strategy for generating genotype-admixed hepatostellate organoids. HBs are combined with terminally differentiated stellate cells to form organoids, followed by terminal hepatocyte differentiation in 3D organoid culture. (B) Representative morphology of HEP::HSC organoids. Scale bar: 200 μm. Quantification of hepatostellate organoid diameter (n = 15). ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (C) 2D HB cultures prior to introduction into hepatostellate organoid stained for stellate cell marker PDGFRβ and HB/hepatocyte marker HNF4α. Arrowhead indicates presence of a stellate cell in the corrected control culture. (D) Images of eGFP expression in iPSC colonies after targeting to the endogenous AAVS1 locus in iPSCs (left) and in iPSC-derived HSCs (right). Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Whole-mount immunofluorescent staining of HNF4α and COL1A1 in organoids. eGFP is constitutively expressed from the AAVS1 locus in the HSCs. Scale bar: 200 μm. (F) Masson's trichrome stain in organoid sections. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G) Whole-mount immunofluorescent staining of COL1A1 and HNF4α in organoids. Scale bar: 100 μm. (H) Whole-mount BODIPY stainingof organoids. Scale bar: 200 μm. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

Strikingly, hepatostellate organoid size dramatically increased in the presence of mutant HEPs, regardless of HSC genotype (Figure 5B and E–H). Organoids containing mutant HEPs had more lipid accumulation compared with those containing corrected HEPs (Figure 5H), consistent with phenotypes observed in 2D cultures.

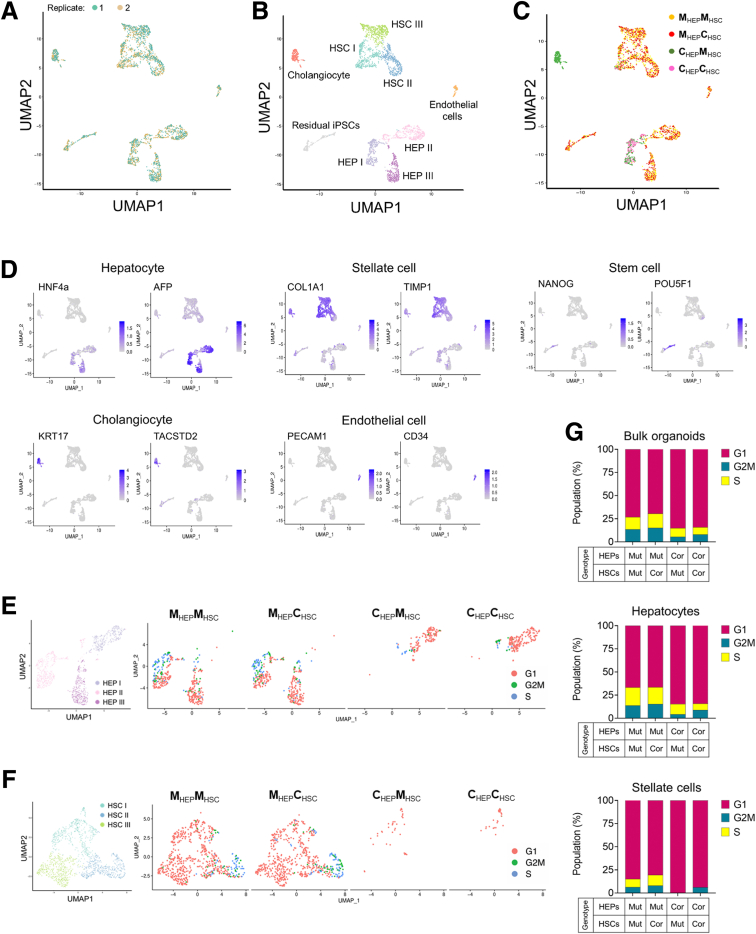

To further characterize the hepatostellate organoids, their cell type–specific gene expression, and the potential for paracrine or juxtacrine interactions between HEPs and HSCs, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) on the 4 combinations of admixed organoids (Figure 5A). Data between replicates were highly congruent (Figure 6A), and replicates were aggregated for analysis.

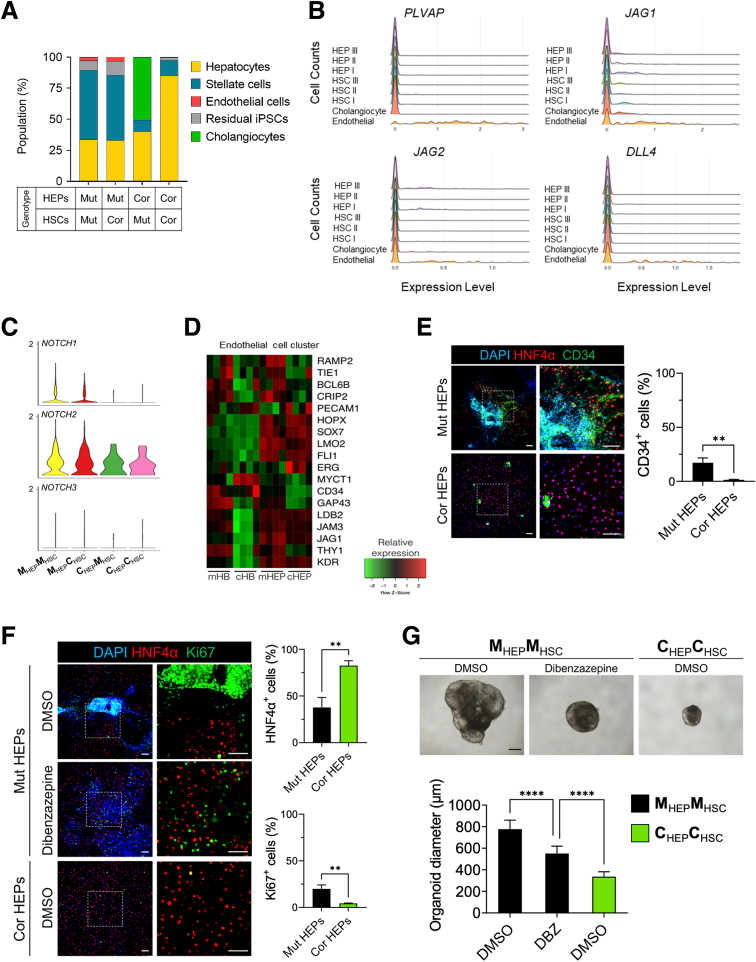

Figure 6.

Single-cell transcriptomics in hepatostellate organoids. (A–C) Uniform Manifold Approximation Projection or Dimensional Reduction (UMAP) of 2991 single-cell transcriptomes from the 4 admixed hepatostellate organoid cultures, annotated by (A) replicate, (B) cell type, and (C) organoid genotype. (D) UMAPs showing expression of the indicated marker genes for each cell type. (E and F) Cell cycle phase analysis in hepatocyte clusters and stellate cell clusters. (G) Quantification of cell cycle distribution in hepatostellate organoids, and more specifically in hepatocyte and stellate cell clusters, as indicated. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

Clustering of roughly 3000 cells identified 9 populations (Figure 6B and C). HEPs resided in 3 clusters (HEP I, HEP II, and HEP III) and expressed classic markers including HNF4α and AFP (Figure 6B and D). Stellate cell markers such as COL1A1 and TIMP1 were broadly expressed across 3 stellate cell clusters (HSC I, HSC II, and HSC III). We also identified a cholangiocyte cluster, an endothelial cell cluster, and some residual undifferentiated stem cells in the organoids (Figures 6B, 6D, and 7B). Cholangiocytes expressed the biliary cell markers KRT17 and TACSTD2 and were found exclusively in corrected HEP::mutant HSC organoids (Figure 6C and D). Endothelial cells were identified only in organoids containing mutant HEPs, regardless of HSC genotype, and expressed endothelial cell markers such as PECAM1 and CD34 (Figure 6C and D). Similarly, residual stem cells were found almost exclusively in organoids with mutant HEPs, possibly related to their inability to efficiently induce HNF4α to promote proper HEP commitment and differentiation (Figure 6C and D). Strikingly, organoids containing mutant HEPs exhibited increased proliferation not only in the HEP compartment, but also in HSCs, regardless of the HSC genotype, indicating that DKC1 mutations in HEPs promote stellate cell activation/proliferation (Figure 6E-G).

Figure 7.

Single-cell transcriptomics of hepatostellate organoids reveals that DCK1-mutant hepatocytes elicit pathologic responses in stellate cells. UMAP projections for HEPs annotated by (A) cluster or (B) organoid genotype. UMAP projections for stellate cells (HSCs) annotated by (C) cluster or (D) organoid genotype. (E) The fraction of cells within each of the 3 HEP and HSC clusters by organoid genotype. (F) Violin plots showing expression of hepatocyte marker genes and MYC across 3 HEP clusters. (G) Expression of activated stellate cell marker genes across 3 HSC clusters. (H) GSEA of HEP I vs HEP II and HEP I vs HEP III. (I) GSEA of HSC I vs HSC II and HSC I vs HSC III. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

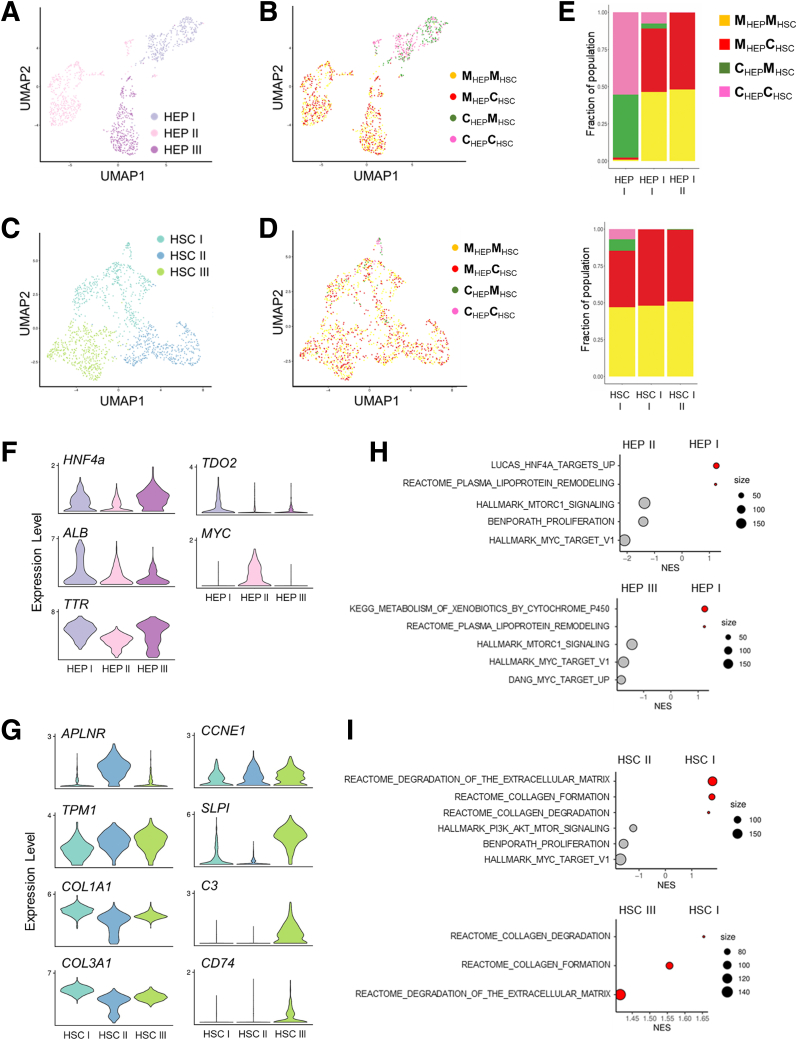

We next examined the 3 HEP and stellate cell clusters more closely (Figures 6B and 7A–D). The HEP I cluster was composed primarily of corrected HEPs, regardless of the stellate cell genotype (Figure 7A, B, and E). In contrast, HEP II and HEP III were composed almost entirely of mutant HEPs, and their identity was also unaffected by stellate cell genotype (Figure 7A, B, and E). HEP I and HEP III express markers of mature HEP differentiation (Figure 7F). In contrast, HEP II is an actively proliferating population with high expression of MYC (Figure 6E and 7F). We thus asked what characterizes the difference between the noncycling wild-type HEP I cluster and the mutant HEP II/HEP III clusters. GSEA on differentially expressed genes between clusters (Supplementary Table 3) revealed that mutant HEP II/III clusters activate MYC targets, along with gene expression programs associated with proliferation and Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (MTORC1) activity (Figure 7H, Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, the HEP I cluster where corrected HEPs reside was enriched for gene sets associated with normal liver physiology, such as metabolism of xenobiotics, lipoprotein remodeling, and HNF4α target gene expression (Figure 7H, Supplementary Table 4). Thus, DKC1-mutant HEPs within hepatostellate organoids exhibited hyperplasia and failed terminal differentiation regardless of the genotype of admixed stellate cells, and differentially expressed genes between corrected and mutant HEPs were consistent between hepatostellate organoids and 2D HEP cultures (compare Figures 7 and 3).

In the stellate cell clusters, cells from all admixed organoid conditions could be found in HSC I, including all HSCs (both mutant and corrected) cocultured with corrected HEPs, which are found primarily at the base of the HSC I cluster (Figures 6F and 7C–E). HSCs cultured with corrected HEPs were rare in our data set due to their low input ratio (1 HSC per 5 HEPs) and lack of proliferation (Figure 6F). HSC clusters II and III were composed exclusively of cells from hepatostellate organoids containing mutant HEPs, further supporting the notion that HEP genotype is the primary driver of HSC phenotype. Relative to HSC II and III, cells in HSC I expressed higher levels of genes encoding extracellular matrix components (COL1A1 and COL3A1) (Figure 7G), and were enriched for processes related to the deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix (Figure 7I). Cells in HSC II (from organoids harboring mutant HEPs) exhibited hallmarks of stellate cell activation. For example, HSC II expressed high levels of APLNR, a gene induced in human cirrhotic livers and involved in vascular remodeling.29,30 HSC II was also highly proliferative, indicating that mutant HEPs induce a proliferative response in nearby stellate cells (Figure 6F). HSC III (also from organoids containing mutant HEPs) also expressed high levels of genes associated with stellate cell activation and inflammation, including TPM1, SLPI, C3, and CD74.31,32 Interestingly, both HSC II and HSC III expressed CCNE1 (Figure 7G), a proliferating cell marker induced in stellate cells by cMyc-overexpressing HEPs in an Alb-Myctg mouse model of fibrosis.33 GSEA results support this notion, with gene sets associated with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/MTOR signaling, MYC targets, and proliferation all enriched in HSC II relative to the “wild-type” HSC I cluster where HSCs associated with corrected HEPs reside (Figure 7I, Supplementary Table 4), independent of HSC genotype. Taken together, these data demonstrate that DKC1 mutations in HEPs induce activation of stellate cells, likely through paracrine or juxtacrine mechanisms. This includes a proliferative and a proinflammatory response associated with hepatic cirrhosis, regardless of stellate cell genotype.

Beyond parenchymal HEPs and stromal stellate cells, a recent single-cell survey of cirrhotic human livers identified endothelial cell populations associated with fibrotic scarring. These scar-associated endothelial populations were marked by PLVAP or ACKR1 positivity and NOTCH ligand expression.21 Therefore, we performed additional analysis of organoids containing mutant HEPs in which endothelial cells were observed (Figure 8A). Strikingly, these endothelial cells expressed high levels of PLVAP and NOTCH ligands JAG1, JAG2, and DLL4, reminiscent of the scar-associated state observed in vivo (Figure 8B).21 Indeed, HEPs and HSCs in hepatostellate organoids expressed NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 receptors, indicating that endothelial-derived NOTCH ligands might contribute to pathologies in HEPs and HSCs (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Endothelial cells associated with DKC1-mutant hepatocytes exhibit proinflammatory phenotypes. (A) Cell composition distribution within hepatostellate organoids. (B) Expression histograms of PLVAP and Notch ligands (JAG1, JAG2, and DLL4) in indicated cell cluster from hepatostellate organoid cultures. (C) Violin plot showing Notch receptor expression across hepatostellate organoid genotypes. (D) Gene expression heatmap visualizing highly expressed genes from the endothelial cell cluster in bulk 2D HB and HEP cultures. (E) Staining of HNF4α and CD34 in 2D HEP cultures (scale bar = 100 μm); CD34-positive cells were quantified at right (n = 3). (F) Immunofluorescence images of HNF4α and Ki67 in HEP cultures of indicated genotypes treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor dibenzazapine (DBZ, (10 μmol/L). Scale bar: 100 μm. Graphs show quantification of images (n = 3). (G) Representative morphology of hepatostellate organoids and quantification of organoid diameter (n = 20). Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗∗P < .01 ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Error bars indicate means ± SD. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

Endothelium is traditionally believed to be a mesoderm-derived tissue. In our datasets, endothelial appearance is correlated with mutant HEP genotype, regardless of the mesodermal-derived stellate cell genotype (Figure 8A), suggesting that either mutant endodermal HEPs instruct endothelial formation within the mesodermal stellate coculture or that endothelium appears as an off-target cell type in the directed differentiation of endodermal HEPs. Interestingly, several prior studies reported that endothelial cells can arise during HEP specification from endoderm, both in human pluripotent-based cultures and in mouse models.34,35 Endothelium also plays an important instructive role during liver development.36

We therefore examined our bulk transcriptome datasets from mutant and corrected 2D HEP cultures for evidence of off-target endothelial differentiation and found genes identified in the endothelial scRNAseq cluster to be expressed at higher levels in mutant cultures at both HB and HEP stages vs isogenic control cells (Figure 8D). This finding was further supported by staining for endothelial marker CD34 (Figure 8E). Thus, it is most likely that the DKC1 mutant endodermal HEP cultures promote off-target differentiation of endothelial cells expressing cirrhotic scar-associated genes. Given that activation of the NOTCH pathway has been implicated in liver fibrosis,37 we asked whether NOTCH inhibition via the γ-secretase inhibitor dibenzazepine could rescue phenotypes in DKC1-mutant HEPs and hepatostellate organoids. Indeed, dibenzazepine was able to reduce abnormal nodule formation and organoid size and reduce but not fully abrogate abnormal proliferation in mutant HEPs (Figure 8F and G). Taken together, these data indicate that endothelial cells may contribute to the liver pathologies in DC patients via NOTCH pathway stimulation.

Pharmacologic Rescue of DC-Associated Liver Phenotypes

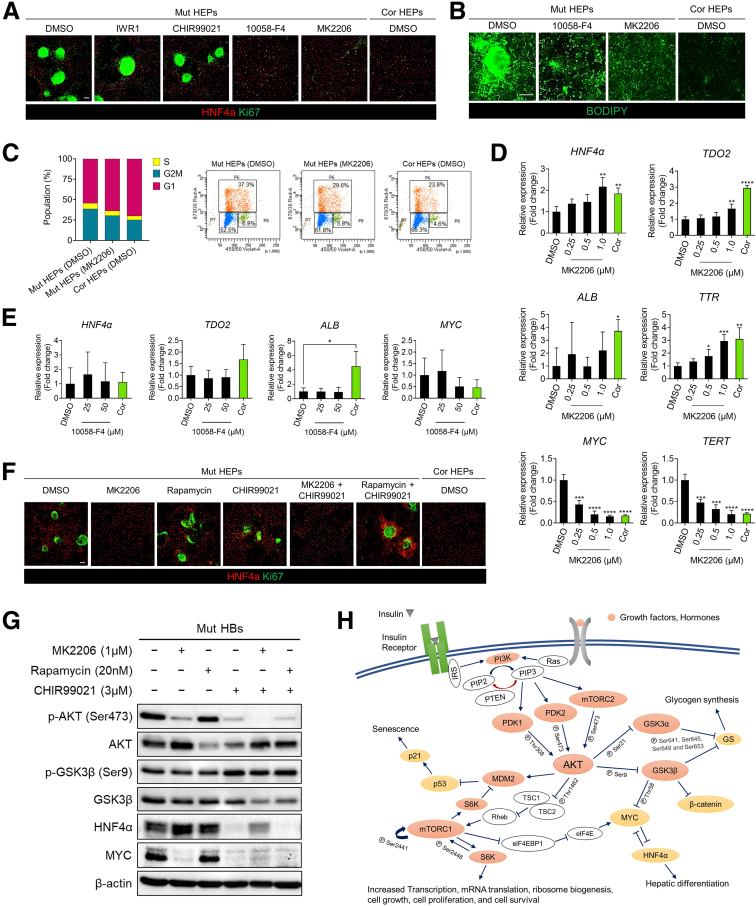

To more effectively rescue abnormal hepatic differentiation and hepatostellate phenotypes associated with DKC1-mutant HEPs, we screened several small molecules targeting dysregulated pathways identified in our transcriptomic analyses (Figures 3B and 7H and I, Supplementary Tables 2 and 4) for their ability to reverse abnormal phenotypes in mutant HEPs. These include inhibitors of GSK3β (a kinase that negatively regulates WNT and MTORC1)38 and of MYC, AKT, and MTORC1. Of these, the AKT inhibitor MK2206 efficiently inhibited nodule formation, proliferation, and lipid accumulation, along with restoring HEP gene expression (including HNF4α) dose dependently in mutant HEPs (Figure 9A–D). The MYC inhibitor 10058-F4 also inhibited nodule formation, proliferation, and lipid accumulation in mutant HEPs (Figure 9A and B). However, it did not re-establish hepatic gene expression as effectively as AKT inhibition (Figure 9E). AKT can negatively regulate GSK3β and positively regulate MTORC1. Interestingly, MTORC1 inhibition with rapamycin was insufficient to suppress MYC expression, and while GSK3β inhibition in combination with AKT inhibition maintained MYC suppression, the addition of GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 abrogated the robust HNF4α activation achieved with AKT inhibition alone (Figure 9F and G).39 Thus, it appears pleiotropic effects downstream of AKT inhibition contribute to the phenotypic rescue observed with MK2206 (Figure 9H).

Figure 9.

AKT inhibition rescues DC phenotypes in hepatocytes.(A) Immunofluorescence images of HNF4α and Ki67 in HEPs treated with dibenzazepine (10 μmol/L), IWR-1-endo (10 μmol/L), CHIR99021 (3 μmol/L), 10058-F4 (50 μM), MK2206 (1.0 μmol/L), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle control starting at the definitive endoderm stage (day 5) and continuing until terminal HEP differentiation (day 17). Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Lipid accumulation in HEPs analyzed by BODIPY staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of cell-cycle distribution in HEP cultures of indicated genotype and treatment. (D) Expression of hepatic marker genes (HNF4α, TDO2, ALB, and TTR), MYC, and TERT in 2D HEP cultures treated with AKT inhibitor MK2206 (n = 4). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (E) Gene expression analysis of hepatic marker genes and MYC in 2D HEP cultures treated with MYC inhibitor 10058-F4 (n = 4). ∗P < .05. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (F) Immunofluorescence staining for HNF4α and Ki67 in 2D HEP cultures treated with indicated small molecules. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G) Western blot analysis of proteins involved in the AKT signaling pathway. (H) Schematic illustration of AKT signaling in hepatocytes. Cor, corrected; Mut, mutant.

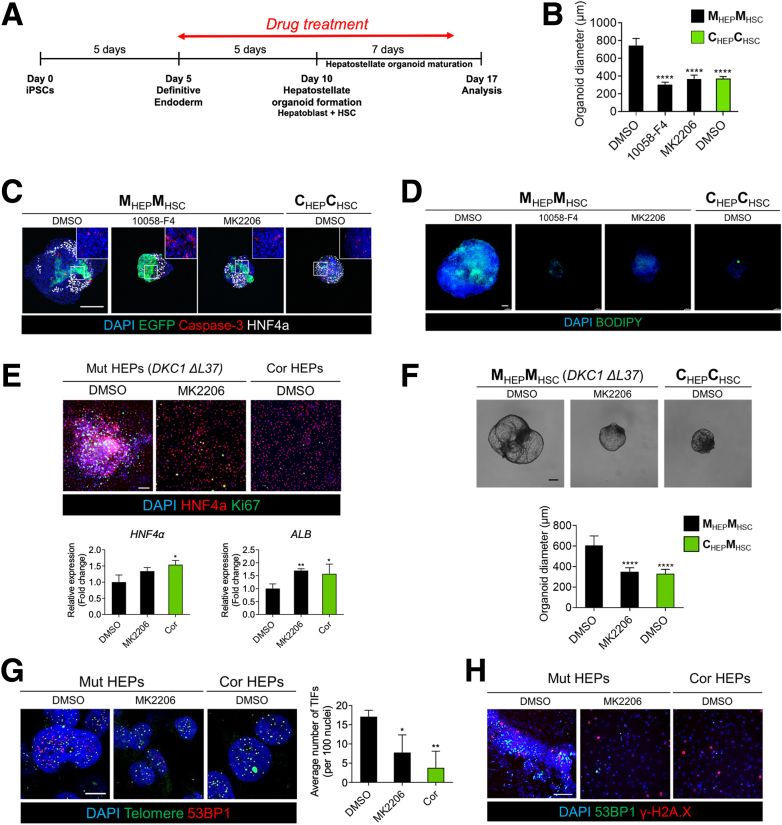

Finally, we generated mutant HEP::mutant HSC hepatostellate organoids using HBs pretreated with AKT or MYC inhibitors (MK2206 or 10058-F8, respectively) followed by further hepatic specification (Figure 10A). Organoid size and lipid accumulation decreased concomitant to an increase in HNF4α expression in response to treatment with either drug (Figure 10B–D). However, MYC inhibition with 10058-F8 appeared to increase apoptosis relative to AKT inhibition or control hepatostellate organoids (CorHEP::CorHSC) (Figure 10C). To ensure that these phenotypes and their pharmacologic rescue were not unique to the DKC1 A353V mutation, we used a second isogenic iPSC pair harboring a less common DKC1 ΔL37 mutation or its corrected DKC1 isogenic counterpart. ΔL37 iPSC-derived HEPs and organoids exhibited phenotypes consistent with the A353V mutation, and AKT inhibition could similarly rescue these phenotypes (Figure 10E and F). Ultimately, we asked whether the phenotypes observed in mutant hepatostellate organoids and their rescue upon AKT inhibition were correlated with the presence of telomere dysfunction–induced foci (TIFs) (defined by colocalization of 53BP1 foci with telomeres). Indeed, we observed TIFs in MutHEP::MutHSC organoids that were markedly reduced upon treatment with MK2206, indicating that AKT inhibition and associated suppression of MYC and activation of HNF4α may be able to feed back to the telomere and promote capping despite the DKC1 mutation (Figure 10G and H).

Figure 10.

Pharmacological rescue of DC phenotypes in hepatostellate organoids. (A) Schematic of drug treatment period during organoid induction. (B) Quantification of organoid diameter in response to indicated drug treatment (n = 20). Error bars indicate mean ± SD. (C) Whole-mount staining of Cleaved Caspase-3 and HNF4α in hepatostellate organoids. Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) BODIPY staining of hepatostellate organoids. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Gene expression analysis and immunofluorescence staining in DKC1 ΔL37 mutant HEPs treated with AKT inhibitor. (n = 4). Error bars indicate mean ± SD. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E) Quantification of DKC1 ΔL37 pair organoid diameter in response to AKT inhibitor (n = 30). Error bars indicate mean ± SD. (G) Representative images showing Telomere Dysfunction Induced Foci (TIFs), quantified at right (n = 3). Scale bar: 10 μm. (H) Representative images showing 53BP1 and γ-H2A.X staining in HEP cultures. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Ultimately, these results indicate that AKT inhibition may represent a viable intervention for preventing DC-associated liver pathologies and demonstrate the utility of the hepatostellate organoid system for modeling these pathologies.

Discussion

The impact of telomere dysfunction on liver development and physiology in humans is poorly understood. While it is well established that patients with liver cirrhosis or chronic inflammatory conditions exhibit shorter telomeres than healthy age-matched control subjects, it is unclear as to whether such telomere shortening is a consequence of disease or whether such telomere shortening may causally contribute to the disease phenotypes. Recent data suggest a causal role for telomere dysfunction in several liver pathologies: 120 patients with known or suspected telomere disorders (telomeropathies)40 presented with liver involvement in 40% of the cohort, many presenting with hepatomegaly and increased echogenicity.1 The fragility of these patients and risks associated with invasive sampling procedures, however, represent significant barriers to tissue acquisition for detailed histologic or molecular analyses. In the few instances in which biopsied tissue has been analyzed, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, steatohepatitis, steatosis, and cirrhosis are reported.1,14,41 These complex liver phenotypes may involve several cell types, including HEPs, HSCs, and endothelial cells. However, it is less clear which of these distinct cell populations are intrinsically affected by telomere dysfunction and which are responding to signals derived from neighboring cells with telomere dysfunction.

Data in mice support HEP-specific telomere dysfunction as causal in several liver diseases.42 An interesting exception is that HEP-specific deletion of Trf2/Terf2 in vivo in adult mice is compatible with normal liver function, which may be explained by the fact that HEPs can tolerate the genome endoreduplication that follows the end–end chromosome fusions that reprotect chromosome termini after loss of Trf2. Regardless, this model may not reflect the consequences of telomere uncapping caused by telomere shortening, as happens in DC.43 Mice and humans also exhibit differences in their telomere biology, complicating interpretation of cross-species comparisons. Mice generally express higher levels of telomerase and respond less robustly to telomere dysfunction. Additionally, laboratory mice harbor much longer telomeres than humans, necessitating several generations of breeding before exhibiting phenotypes related to telomere dysfunction upon genetic ablation of Terc or Tert.44, 45, 46 In contrast, human embryos with complete loss of telomerase activity are not viable, and thus human telomeropathies are generally considered to result from hypomorphic loss-of-function alleles, and human phenotypes may be related to developmental failures, telomere dysfunction occurring after development, or a combination.

Here, we utilize isogenic human iPSCs harboring a hypomorphic loss-of-function mutation in DKC1, which results in telomere dysfunction and DC, and their gene-edited normal isogenic control cells. The directed differentiation of these lines into HEP-like cells and HSCs provides evidence for cell-autonomous phenotypes in HEPs, including lipid accumulation and hyperproliferative nodule formation that may be a correlate to the nodular hyperplasia observed in vivo.13,24 Although dyskerin plays roles in ribosome biogenesis, the DKC1 mutations that cause DC (including the A353V mutation studied here) do not appear to significantly impact this aspect of dyskerin function.11,12 Indeed, rather than observing evidence for ribosome-related defects, we instead observed a broad upregulation of genes encoding translation factors in mutant HEP-like cells, consistent with their hyperproliferative nature. Little to no phenotypic changes were observed in stellate cells alone. However, hepatostellate organoids generated by admixing HEPs and stellate cells from either DKC1 mutant or isogenic control cultures revealed an instructive role for mutant HEPs in inducing a hyperplastic, proinflammatory response in stellate cells. Interestingly, off-target endothelial cells expressing genes linked to scar-associated endothelium in cirrhotic human livers21 were observed in cultures containing mutant HEPs. Thus, our findings indicate that HEPs, and possibly endothelial cells, contribute to the liver phenotypes associated with DC, and possibly with telomeropathies more broadly. They further suggest that the DKC1 mutation may also influence aberrant developmental establishment of these tissues, even if overt phenotypes do not manifest until sometime after birth. The notion that telomere dysfunction in HEPs may be causal in cirrhotic phenotypes may even extend to idiopathic liver fibrosis, in which telomerase mutations are often observed.16,17

Our model ultimately provides a framework for identifying and testing potential interventions in telomere-associated liver disorders. Indeed, inhibition of Notch, which is stimulated by scar-associated endothelial cells and linked to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis,21,37 was able to rescue hyperproliferative phenotypes in hepatostellate organoids. Similarly, aberrant AKT activity (a positive regulator of MYC) in HEP-like cells appears to underly several of the phenotypes we observe both in 2D and hepatostellate organoid cultures. The ability of small-molecule inhibitors of AKT to inhibit MYC expression, hyperproliferation, and lipid accumulation and restore HNF4α activity may point to a preventative approach to DC-associated liver phenotypes. However, the extent to which such interventions might reverse liver pathologies once they are established remains unclear.

Taken together, organoid-based models of telomeropathies provide a valuable resource for understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying pathologies in these deadly and largely untreatable diseases. We hope that the hepatostellate organoid model described here provides a framework for vetting future therapeutic approaches targeting the liver pathologies associated with telomere dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Male DC patient–derived DKC1 mutant iPSCs were kindly provided by Dr. Timothy S. Olson (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia). Every iPSC line (DKC1 A353V iPSCs, DKC1 A353V mutation–corrected iPSCs, DKC1 ΔL37 iPSCs, DKC1 ΔL37 mutation–corrected iPSCs, DKC1 A353V [AAVS1-EGFP] iPSCs and DKC1 A353V mutation–corrected [AAVS1-EGFP] iPSCs) were maintained on vitronectin (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) coated plates using StemMACS iPSC-Brew XF medium (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and passaged with 0.5 mmol/L EDTA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). iPSCs were cultured at 37 °C in 4% CO2 and 5% O2 and the medium was replaced every day.

Correction of DKC1 Mutation in iPS Cells

The plasmid, pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (pX458), was obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA). Guide RNAs (gRNAs) for correction of DKC1 A353V mutations were designed using the gRNA design tool from Benchling (https://www.benchling.com/crispr). Designed gRNAs and single-stranded DNA donor oligos were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). gRNAs are inserted into the plasmid and sequenced using the U6 primer (5′-ACTATCATATGCTTACCGTAAC-3′). Patient-derived iPSCs were electroporated with plasmids and single stranded DNA donor oligos using Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 1 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). After 36 hours, transfected cells were selected by GFP-positive cell sorting. Sorted cells were plated onto Matrigel (Corning, Corning, NY) coated 100-mm dishes in StemMACS iPSC-Brew XF medium with 10 μmol/L Y-27632 (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX). When cell colonies were large enough to be picked, colonies were subcloned and replated into individual wells of Matrigel-coated 96-well plates in StemMACS iPSC-Brew XF medium with 10 μmol/L Y-27632. During replating, some iPSCs from each subclone were collected for genomic DNA isolation. After PCR amplification of the targeted region from purified genomic DNA, Sanger sequencing analysis was performed to select DKC1 mutation–corrected clones. The sequences of gRNAs and homology-directed repair templates are presented in Supplementary Table 6. The efficiencies of DKC1 A353V (57.1%) and ΔL37 (33.3%) correction were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

iPS Cell Karyotyping and Teratoma Formation

Karyotyping was performed by Cell Line Genetics (Madison, WI) on 20 G-banded metaphase cells from both A353V mutant iPSCs and their isogenic corrected control cells, at passage 59. Cultures maintained karyotypic stability. Teratoma formation was carried out by implanting 1 × 105 iPSCs suspended in Matrigel subcutaneously into the flank of immune-compromised NSG mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; Jax 005557). After 6 weeks, teratomas were isolated and processed for histology.

HEP Differentiation

iPSCs were differentiated into HEPs following previous protocols22,23 with modification as follows: iPSCs were replated onto Matrigel-coated plates at 0.8 × 105 cells/cm2 in StemMACS iPSC-Brew XF medium (Miltenyi Biotec) with 10 μmol/L Y-27632 (Selleck Chemicals). After 1 day, the medium was changed to RPMI-1640 (Lonza) containing 50 ng/mL Activin A (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), B27 supplement (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 0.5 mmol/L sodium butylate (Sigma). The concentration of sodium butylate was reduced to 0.1 mmol/L for 4 days to induce definitive endoderm differentiation. For HB induction, the definitive endoderm was cultured in RPMI-1640 (Lonza) supplemented with 10 ng/mL HGF (PeproTech) and 10 ng/mL FGF4 (PeproTech), 0.5 mg/mL BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), and B27 supplement (Gibco) for 5 days. HB stage cells were then cultured in Hepatocyte Culture Medium (without epidermal growth factor (EGF) supplement; Lonza) with 10 ng/mL HGF, 10 ng/mL OSM (PeproTech), and 0.1 mmol/L dexamethasone (Dex) for final differentiation.

HSC Differentiation and Expansion

HSCs were differentiated and maintained as previously described.25 Briefly, to prepare HSC differentiation medium, 57% Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium low glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 40% MCDB-201 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) were mixed and supplemented with 0.25× linoleic acid–BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25× insulin-transferrin-selenium (Sigma), 1% penicillin streptomycin (Lonza), 100 μmol/L L-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5 mmol/L Dex, and 50 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). On days 0–4, cells were cultured in HSC differentiation medium containing 20 ng/mL BMP4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for mesoderm induction. At day 4, growth factors in the medium were changed to 20 ng/mL BMP4, 20 ng/mL FGF1 (R&D Systems), and 20 ng/mL FGF3 (R&D Systems). At day 6, differentiating cells were maintained in HSC differentiation medium with 20 ng/mL FGF1, 20 ng/mL FGF3, 5 mmol/L retinol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 mmol/L palmitic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). On days 8–12, the medium was switched into HSC differentiation medium with 5 mmol/L retinol and 100 mmol/L palmitic acid.

After final differentiation, HSCs were incubated in cell recovery solution (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 30 minutes on ice for recovery. Then, cells were harvested using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and replated on plates coated with Matrigel. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium high glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 mmol/L retinol, and 100 mmol/L palmitic acid. Medium was refreshed every 2 days. HSCs used in this study were not passaged more than once.

Transcriptome Profiling

Transcriptome sequencing was performed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ). All samples had RNA integrity number of at least 9.5. Libraries were prepared by Poly A selection from total RNA and sequenced using HiSeq 2 × 150 bp sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA). FASTQ files from Genewiz were used for further analysis using the statistical computing environment R (v4.0.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), RStudio (v1.1.456; RStudio, Boston, MA), and the Bioconductor suite of packages for R.47 FASTQ files were mapped to the human transcriptome (EnsDb.Hsapiens.v86) using Salmon.48 Reads were annotated with EnsemblDB and EnsDb.Hsapiens.v86, and Tximport49 was used to summarize transcripts to genes. Limma50 was used to control for batch effects on PCA visualization. For differential gene expression analysis, data were filtered to remove unexpressed and lowly expressed (<10 transcripts across all samples). Differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate, <0.05; absolute log2 fold change, ≥0.59) were identified using DESeq2.51 Heatmaps were created and visualized using gplots. GSEA was used for enrichment analysis.52 Raw data are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession number: 174018).

Hepatostellate Organoid Induction

HBs at day 10 and fully differentiated HSCs were detached by Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies) and 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, respectively. HBs and HSCs were mixed in a 5:1 ratio, then seeded into a 96-well U-bottom plate coated with Nunclon Sphera (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a density of 3000 cells per well. Organoids were cultured in Hepatocyte Culture Medium with 10 ng/mL HGF, 10 ng/mL OSM, and 0.1 mmol/L Dex for 7 days.

Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Hepatostellate organoids at day 17 were treated with dissociation buffer (1:1:1 mixture of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, Accutase [STEMCELL Technologies], and Collagenase IV [1 mg/mL; Gibco]) at 37 °C for 20 minutes. Cells were filtered through a 40-μm Flowmi cell strainer (Bel-Art, Wayne, NJ) before flow sorted using Aria B (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Sorted cells were encapsulated using the Chromium Controller and the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library & Gel Bead Kit (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA) following the standard manufacturer’s protocols. All libraries were quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and pooled for sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Applied Genomics. Targeted median read depth was 50,000 reads per cell from total gene expression libraries and 10,000 reads per cell for hashtag barcode libraries.

Cell Ranger (version 3.1.0; 10x Genomics) was used to align reads to the GRCh38-3.0.0 transcriptome and quantify read and hashtag counts.53 Seurat (version 4.0.1) was used for standard quality control, hashtag doublet removal, log normalization, regression of difference between S and G2M phase cells, and multiple clustering techniques (PCA, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) following the appropriate Seurat workflows and their parameters.54 VisCello (version 1.1.1) was used for visualization of cell clusters, differential expression, gene ontology, and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analyses using default parameters.55 PHATE clustering was performed using the PhateR (version 1.0.7) package.56 Raw data are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession number 188987).

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with 5% serum in PBS. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (antibodies used in this study listed in Supplementary Table 7) and subsequently incubated with secondary antibody (1:500 dilution) for an hour at room temperature. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for nuclei staining. Stained cells were imaged by Leica DMI8. Fiji (ImageJ2 2.9.0/1.53t, National Institutes of Health) was used for quantification of immunostaining.

qTRAP Assay

To measure telomerase activity, the qTRAP (qPCR-based telomeric repeat amplification protocol) was performed as previously described.57 Briefly, cells were harvested and resuspended at a concentration of 1000 cells/μL in NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40). Then, cells were incubated on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4 °C. BCA protein assay (Pierce, Appleton, WI) was performed using the supernatant to determine concentration of the protein. qPCR was conducted using 1 μg lysate. HEK 293 cells were used as telomerase-positive sample for generating a standard curve.

Telomere Shortest Length Assay

Telomere length was investigated using the Telomere Shortest Length Assay (TeSLA) as described.58 DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA concentrations were quantified with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen). Fifty nanograms of each sample were ligated with telorette adapters. The samples were digested with CviAII, followed by a mixture of BfaI, MseI, and NdeI. The samples were then dephosphorylated and ligated with the TeSLA AT/TA adaptors. 20 ng of each sample were PCR amplified using the FailSafe PCR system with PreMix H (Lucigen, Middleton, WI). Southern blot–based detection of telomere PCR products was modified from previous protocols.59,60 PCR-amplified samples were run on a 0.7% agarose gel at 0.83 V/cm for 44 hours at 4 °C. The gel was depurinated and denatured, then transferred to a Hybond-XL membrane (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) overnight with denaturation buffer. The blot was then neutralized with saline–sodium citrate (SSC) and hybridized with a DIG-labeled telomere probe prepared as described59 in DIG Easy Hyb (Sigma-Aldrich) solution overnight at 42 °C. The blot was washed and exposed with CDP-Star (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and visualized in an ImageQuant LAS 4000 (Cytiva). TeSLA quantification was performed using the MATLAB 2016b (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) analyzer program, TeSLAQuant.

TIF Assay

Cells were hybridized with a Cy3-labeled PNA telomere repeat probe (Panagene [5′-CCCTAA-3′]) and anti-53BP1 antibodies as described61 with slight modifications. Briefly, 4% PFA-fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 minute at room temperature, then washed with PBS for 3 minutes. Cells were then blocked in 4% BSA/0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature, incubated with rabbit anti-53BP1 antibodies (NB100-304, 1:100 dilution; Novus, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours at 37 °C in a humidified chamber, washed with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (A-21244, 1:500 dilution; Invitrogen) for 1 hour at 37 °C. After washing with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, cells were incubated with 4% PFA in PBS for 20 minutes to fix antibody in place, followed by quenching of the formaldehyde with 0.25 mmol/L glycine. The cells were subsequently dehydrated with ethanol and air dried. Cy3-conjugated telomere specific PNA probe was applied in hybridization mix (per 100 μL, mix 70 μL of freshly deionized formamide, 15 μL PNA buffer [80 mmol/L Tris-Cl pH 8, 33 mmol/L KCl, 6.7 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.0067% Triton X-100], 10 μL 25 mg/mL acetylated BSA, 5 μL 10 μg/mL PNA probe). Cells were covered with a glass coverslip, denatured at 83 °C for 4 minutes on a heating block, and incubated in the dark in a humidified chamber overnight at room temperature. Cells were then washed sequentially with 3 times with 70% formamide/2× SSC, 2× SSC, and PBS, then blocked and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated donkey anti-goat antibodies (A-21447, 1:500 dilution; Invitrogen), stained with DAPI and mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent (P36935; Invitrogen). Confocal images were obtained with the inverted Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) laser-scanning confocal microscope (TCS SP8) and TIFs were counted by an observer blind to the identity of the samples.

qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qPCR was performed using QuantStudio 6 Flex real-time PCR system with power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). All gene expression data were normalized by GAPDH using the comparative CT method (2-ΔΔCt). Primer sequences used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Cell Proliferation Assay

EdU incorporation assays were performed to analyze proliferation in HEPs. Briefly, fully differentiated HEPs were cultured with 10 μmol/L Edu for 2 hours. After 2 days, dead cells were labeled with eFluor 780 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell proliferation assays were performed using Click-iT Plus Edu Flow cytometry assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then fixation, permeabilization, and Edu detection were conducted using Click-iT Plus Edu flow cytometry assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA contents were stained with FxCycle Violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were analyzed using LSRFortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Acetylated-Low-Density Lipoprotein Uptake

After final differentiation, HEPs were cultured with 10 μg/mL 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindo-carbocyanine labeled acetylated-low-density lipoprotein (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C for 5 hours. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS and imaged by a Leica DMI8.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) containing protein inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Protein concentration was estimated by BCA protein assay (Pierce). A total of 30 μg protein was separated by gel electrophoresis, followed by transfer to membranes. Blots blocked with 5% BSA were incubated with primary antibodies for overnight. After washing with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Peroxidase activity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce).

Accumulated Lipid Staining

Intracellular lipid accumulation was detected using BODIPY and Oil Red O staining. HEPs and hepatostellate organoids were fixed with 4% PFA solution in PBS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For BODIPY staining, fixed cells or HEPs prestained with ALB were incubated with BODIPY 493/503 (1 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI for 30 minutes. For Oil Red O staining, fixed HEPs were washed with 60% isopropanol and incubated with 0.5% Oil Red O solution for 30 minutes. To quantify intracellular lipids, extract Oil Red O stain with 100% isopropanol were measured by scanning with microplate reader (Optical density = 500 nm).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ALB and Cytokines)

To measure ALB and cytokine secretion level from HEPs, medium was collected after 24 hours (for ALB) or 72 hours (for cytokines) of culture with HEPs and stored at –80 °C until use. Human Albumin ELISA Quantitation Kit (Bethyl Laboratory, Montgomery, TX) and IL6, tumor necrosis factor α, and transforming growth factor β Quantikine ELISA Kits (R&D Systems) were used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Organoid Staining

For whole-mount immunofluorescence staining and imaging of admixed organoids, the organoids were fixed for 30 minutes at room temperature in 4% PFA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After washing with PBS, the organoids were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at room temperature, blocked with blocking buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 10% donkey serum (Abcam) for 1 hour at room temperature, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer at 4°C. Primary antibodies included goat anti-GFP (Abcam), rabbit anti-Ki67 (Abcam), rabbit anti-Collagen I (Abcam), rabbit anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti–HNF-4-α (Abcam). The following day, antibodies were removed and the organoids were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. Organoids were then incubated in the dark with secondary antibodies diluted at 1:500 in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled using DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For imaging, organoids were mounted on a glass-bottom dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA) in 1.5% low-melt agarose (Lonza) and cleared overnight using Ce3D.62 Fluorescence images were obtained using the inverted Leica laser-scanning confocal microscope (TCS SP8). Images were processed and brightness and contrast were enhanced using Fiji (ImageJ2 2.9.0/1.53t, National Institutes of Health).

Generation of eGFP-Expressing iPS Cells

The pX330-SpCas9 and AAVS1-Pur-CAG-EGFP plasmid were acquired from Addgene. gRNAs were designed as previously described28 and cloned into BbsI digested Cas9 plasmid. DKC1 A353V mutant and corrected iPSCs were transfected with the gRNA-Cas9 vector and the knock-in vector and plated onto plate coated with Matrigel. After 24 hours, puromycin selection was performed for additional 3 days to select for positively transfected cells. Surviving colonies were picked and expanded. eGFP knock-in was confirmed by PCR analysis using AAVS1-specific primers.28

Masson’s Trichrome Staining

For Masson’s trichrome staining, hepatostellate organoids were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS and transferred into 2% agarose. Then, organoids in agarose gel were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 micron. Collagens in the organoids were stained using Masson's Trichrome Stain Kit (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Small Molecule Treatment

For small molecule rescue assays, day 5 definitive endoderm stage cells were cultured with inhibitors such as dibenzazepine (10 μmol/L; Selleck Chemicals), IWR-1-endo (10 μmol/L; Selleck Chemicals), CHIR99021 (3 μmol/L; Tocris, Bristol, United Kingdom), 10058-F4 (25 and 50 μmol/L; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), MK2206 (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μmol/L; Selleck Chemicals), or dimethyl sulfoxide until final differentiation (day 17). All inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as the arithmetic means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using the Student t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical parameters, including numbers and significance, are shown in the legend for each figure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Johnson and Lengner laboratories, as well as Dr. Rebecca Wells, Dr. Foteini Mourkioti, and the Mourkioti laboratory, for discussions on the study and manuscript. The authors thank Team Telomere for their continued support of this research. The authors thank the Cell and Developmental Biology Microscopy Core for access to the confocal microscopy equipment used in their work. Cell lines generated and used in this study are available upon request from the lead contact (Christopher J. Lengner). The accession number for the RNA-sequencing data reported in this article is GEO: GSE 174018. The accession number for single-cell RNA sequencing seq data is GEO: GSE 188987. A previous version of this manuscript was posted to bioRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.19.469258.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Young-Jun Choi (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Lead; Project administration: Lead; Visualization: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Melissa S. Kim (Formal analysis: Equal; Project administration: Equal; Visualization: Equal)

Joshua H. Rhoades (Formal analysis: Equal; Software: Equal; Visualization: Equal)

Nicolette M. Johnson (Formal analysis: Supporting; Software: Supporting; Validation: Supporting)

Corbett T. Berry (Data curation: Supporting; Software: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Sarah Root (Project administration: Supporting)

Qijun Chen (Project administration: Supporting)

Yuhua Tian (Project administration: Supporting)

Rafael J. Fernandez III (Project administration: Supporting)

Zvi Cramer (Project administration: Supporting)

Stephanie Adams-Tzivelekidis (Project administration: Supporting)

Ning Li (Project administration: Supporting; Software: Supporting)

F. Brad Johnson (Conceptualization: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Lead; Supervision: Supporting)

Christopher J. Lengner (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01HL148821, R21AG054209, and 2T32HD083185-06A1 (F.B.J., C.J.L., and M.S.K.), and by grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (Health Research Formula Fund), Team Telomere, and the Penn Orphan Disease Center. This work was additionally supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases grant P30DK050306 and its core facilities.

Contributor Information

F. Brad Johnson, Email: johnsonb@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Christopher J. Lengner, Email: lengner@upenn.edu.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Kapuria D., Ben-Yakov G., Ortolano R., et al. The spectrum of hepatic involvement in patients with telomere disease. Hepatology. 2019;69:2579–2585. doi: 10.1002/hep.30578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirwan M., Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita, stem cells and telomeres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo D.H., Chen Q., Yang T.L.B., et al. Enhancing a Wnt-telomere feedback loop restores intestinal stem cell function in a human organotypic model of dyskeratosis congenita. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armanios M., Blackburn E.H. The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savage S.A. Human telomeres and telomere biology disorders. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;125:41–66. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397898-1.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vulliamy T.J., Knight S.W., Mason P.J., et al. Very short telomeres in the peripheral blood of patients with X-linked and autosomal dyskeratosis congenita. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:353–357. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munroe M., Niero E.L., Fok W.C., et al. Telomere dysfunction activates p53 and represses HNF4α expression leading to impaired human hepatocyte development and function. Hepatology. 2020;72:1412–1429. doi: 10.1002/hep.31414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez RJ, Gardner ZJG, Slovik KJ, et al. GSK3 inhibition rescues growth and telomere dysfunction in dyskeratosis congenita iPSC-derived type II alveolar epithelial cells. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.28.358887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Roake C.M., Artandi S.E. Regulation of human telomerase in homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:384–397. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagpal N., Wang J., Zeng J., et al. Small-molecule PAPD5 inhibitors restore telomerase activity in patient stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:896–909.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu B.W., Apicella M., Mills J., et al. Impaired telomere maintenance and decreased canonical WNT signaling but normal ribosome biogenesis in induced pluripotent stem cells from X-linked dyskeratosis congenita patients. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thumati N.R., Zeng X.L., Au H.H.T., et al. Severity of X-linked dyskeratosis congenita (DKCX) cellular defects is not directly related to dyskerin (DKC1) activity in ribosomal RNA biogenesis or mRNA translation. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:1698–1707. doi: 10.1002/humu.22447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patnaik M.M., Kamath P.S., Simonetto D.A. Hepatic manifestations of telomere biology disorders. J Hepatol. 2018;69:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calado R.T., Regal J.A., Kleiner D.E., et al. A spectrum of severe familial liver disorders associate with telomerase mutations. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calado R.T., Young N.S. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2353–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann D., Srivastava U., Thaler M., et al. Telomerase gene mutations are associated with cirrhosis formation. Hepatology. 2011;53:1608–1617. doi: 10.1002/hep.24217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calado R.T., Brudno J., Mehta P., et al. Constitutional telomerase mutations are genetic risk factors for cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53:1600–1607. doi: 10.1002/hep.24173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolph K.L., Chang S., Millard M., et al. Inhibition of experimental liver cirrhosis in mice by telomerase gene delivery. Science. 2000;287:1253–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiemann S.U., Satyanarayana A., Tsahuridu M., et al. Hepatocyte telomere shortening and senescence are general markers of human liver cirrhosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:935–942. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0977com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou W.C., Zhang Q.B., Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7312–7324. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran P., Dobie R., Wilson-Kanamori J.R., et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature. 2019;575:512–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai J., Zhao Y., Liu Y., et al. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into functional hepatic cells. Hepatology. 2007;45:1229–1239. doi: 10.1002/hep.21582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H.J., Choi Y.J., Kim J.W., et al. Differences in the epigenetic regulation of cytochrome P450 genes between human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes and primary hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorgy A.I., Jonassaint N.L., Stanley S.E., et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome is a frequent cause of dyspnea in the short telomere disorders. Chest. 2015;148:1019–1026. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coll M., Perea L., Boon R., et al. Generation of hepatic stellate cells from human pluripotent stem cells enables in vitro modeling of liver fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:101–113.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang-Verslues W.W., Sladek F.M. Nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α1 competes with oncoprotein c-Myc for control of the p21/WAF1 promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:78–90. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman S.L. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oceguera-Yanez F., Kim S.-I., Matsumoto T., et al. Engineering the AAVS1 locus for consistent and scalable transgene expression in human iPSCs and their differentiated derivatives. Methods. 2016;101:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melgar-Lesmes P., Pauta M., Reichenbach V., et al. Hypoxia and proinflammatory factors upregulate apelin receptor expression in human stellate cells and hepatocytes. Gut. 2011;60:1404–1411. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokomori H., Oda M., Yoshimura K., et al. Overexpression of apelin receptor (APJ/AGTRL1) on hepatic stellate cells and sinusoidal angiogenesis in human cirrhotic liver. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X., Rosenthal S.B., Meshgin N., et al. Primary alcohol-activated human and mouse hepatic stellate cells share similarities in gene-expression profiles. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:606–626. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krenkel O., Hundertmark J., Ritz T., et al. Single cell RNA sequencing identifies subsets of hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts in liver fibrosis. Cells. 2019;8:503. doi: 10.3390/cells8050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nevzorova Y.A., Hu W., Cubero F.J., et al. Overexpression of c-myc in hepatocytes promotes activation of hepatic stellate cells and facilitates the onset of liver fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1765–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman O., Han S., Hamou W., et al. Endoderm generates endothelial cells during liver development. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gouon-Evans V., Boussemart L., Gadue P., et al. BMP-4 is required for hepatic specification of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived definitive endoderm. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1402–1411. doi: 10.1038/nbt1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han S., Tan C., Ding J., et al. Endothelial cells instruct liver specification of embryonic stem cell-derived endoderm through endothelial VEGFR2 signaling and endoderm epigenetic modifications. Stem Cell Res. 2018;30:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geisler F., Strazzabosco M. Emerging roles of Notch signaling in liver disease. Hepatology. 2015;61:382–392. doi: 10.1002/hep.27268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermida M.A., Dinesh Kumar J., Leslie N.R. GSK3 and its interactions with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling network. Adv Biol Regul. 2017;65:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang M., Li S.N., Anjum K.M., et al. A double-negative feedback loop between Wnt-β-catenin signaling and HNF4α regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5692–5703. doi: 10.1242/jcs.135053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holohan B., Wright W.E., Shay J.W. Telomeropathies: an emerging spectrum disorder. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:289–299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carulli L., Dei Cas A., Nascimbeni F. Synchronous cryptogenic liver cirrhosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a clue to telomere involvement. Hepatology. 2012;56:2001–2003. doi: 10.1002/hep.26089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin S., Nascimento E.M., Gajera C.R., et al. Distributed hepatocytes expressing telomerase repopulate the liver in homeostasis and injury. Nature. 2018;556:244–248. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0004-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denchi E.L., Celli G., de Lange T. Hepatocytes with extensive telomere deprotection and fusion remain viable and regenerate liver mass through endoreduplication. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2648–2653. doi: 10.1101/gad.1453606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calado R.T., Dumitriu B. Telomere dynamics in mice and humans. Semin Hematol. 2013;50:165–174. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smogorzewska A., de Lange T. Different telomere damage signaling pathways in human and mouse cells. EMBO J. 2002;21:4338–4348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng D., Wang S., Jia W., et al. Regulation of human and mouse telomerase genes by genomic contexts and transcription factors during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16764-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huber W., Carey V.J., Gentleman R., et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat Methods. 2015;12:115–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patro R., Duggal G., Love M.I., et al. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soneson C., Love M.I., Robinson M.D. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: Transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res. 2016;4:1521. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7563.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng G.X.Y., Terry J.M., Belgrader P., et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hao Y., Hao S., Andersen-Nissen E., et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573–3587.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Packer J.S., Zhu Q., Huynh C., et al. A lineage-resolved molecular atlas of C. Elegans embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science. 2019;365 doi: 10.1126/science.aax1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moon K.R., van Dijk D., Wang Z., et al. Visualizing structure and transitions in high-dimensional biological data. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1482–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0336-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herbert B.S., Hochreiter A.E., Wright W.E., et al. Nonradioactive detection of telomerase activity using the telomeric repeat amplification protocol. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1583–1590. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai T.P., Zhang N., Noh J., et al. A method for measuring the distribution of the shortest telomeres in cells and tissues. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1356. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai T.P., Wright W.E., Shay J.W. Generation of digoxigen in incorporated probes to enhance DNA detection sensitivity. BioTechniques. 2016;60:306–309. doi: 10.2144/000114427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura M., Stone R.C., Hunt S.C., et al. Measurement of telomere length by the southern blot analysis of terminal restriction fragment lengths. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1596–1607. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]