Abstract

Among the various components of the protozoan Plasmodium mitochondrial respiratory chain, only Complex III is a validated cellular target for antimalarial drugs. The compound CK-2-68 was developed to specifically target the alternate NADH dehydrogenase of the malaria parasite respiratory chain, but the true target for its antimalarial activity has been controversial. Here, we report the cryo-EM structure of mammalian mitochondrial Complex III bound with CK-2-68 and examine the structure–function relationships of the inhibitor's selective action on Plasmodium. We show that CK-2-68 binds specifically to the quinol oxidation site of Complex III, arresting the motion of the iron-sulfur protein subunit, which suggests an inhibition mechanism similar to that of Pf-type Complex III inhibitors such as atovaquone, stigmatellin, and UHDBT. Our results shed light on the mechanisms of observed resistance conferred by mutations, elucidate the molecular basis of the wide therapeutic window of CK-2-68 for selective action of Plasmodium vs. host cytochrome bc1, and provide guidance for future development of antimalarials targeting Complex III.

Keywords: antimalarials, complex III, CK-2-68, quinolone inhibitors, NDH2

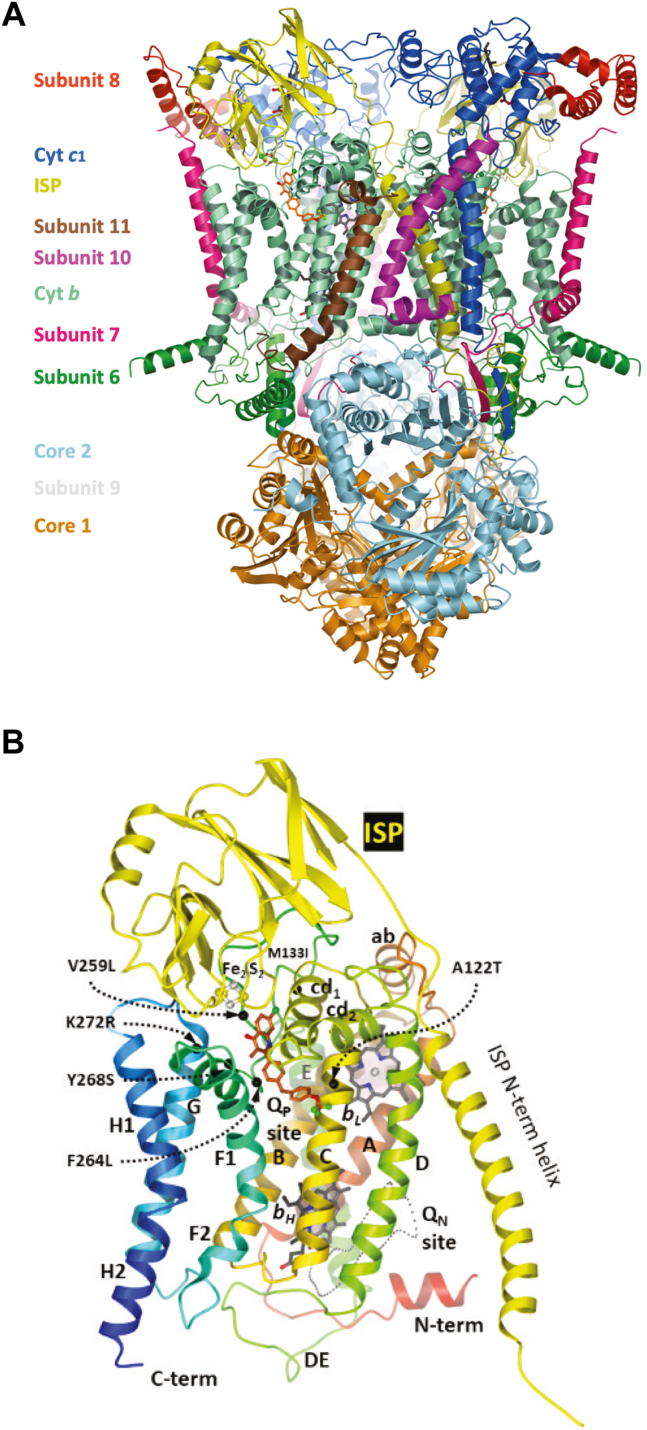

Decades of international efforts in research and development of malaria treatments and prevention have supported a steady decline in the incidents and death toll of this disease. However, this trend was reversed in recent years for reasons including the rise in resistance to front-line therapy (1). New drug discoveries and novel targets are continually needed to counter these evolutionary adaptations. The Plasmodium electron transport chain (ETC) is a validated target, meaning it is sufficiently distinct from that of host cells for useful therapeutic attack. One component of the Plasmodium falciparum ETC, Complex III, also known as cytochrome bc1 complex or Pfbc1, is already an important target for the antimalarial drug atovaquone, as well as several drug candidates. Occupying the center of the mitochondrial ETC, Complex III is a favorable target, both for natural antibiotics and synthetic drugs, featuring two active sites (Fig. 1): the quinol oxidation site (Qo or QP site) and the quinone reduction site (Qi or QN site). However, with the evolution of parasite strains carrying resistance mutations in Complex III, research interests have been rising to target Complex III differently and to search for other components of the Plasmodium ETC as effective and uncompromised drug targets (2, 3).

Figure 1.

The cryo-EM structure of Bos taurus cyt bc1with CK-2-68 bound.A, view of the homodimeric enzyme rendered as a cartoon with 11 different subunits labeled and uniquely colored. B, the cyt b and iron-sulfur-protein subunits from the experimentally derived structure of bovine cyt bc1 complex are presented in ribbon representation with labeled secondary structure elements (cyt b only) (24). The locations of the two active sites are labeled with QP for the quinol oxidation site (QP/Qo) and QN for the quinone reduction site (QN/Qi). The QP site contains the model of CK-2-68 based on the EM density. The QN site remains unoccupied. The light gray dotted line delineates the area where the quinone substrate or QN-site inhibitors would bind. Mutations (PF: K272R, Y268S, V259L, F264L, M133I, A122T) that led to CK-2-68 resistance in Plasmodium parasites are mapped to the structure and indicated by black dots near the QP site.

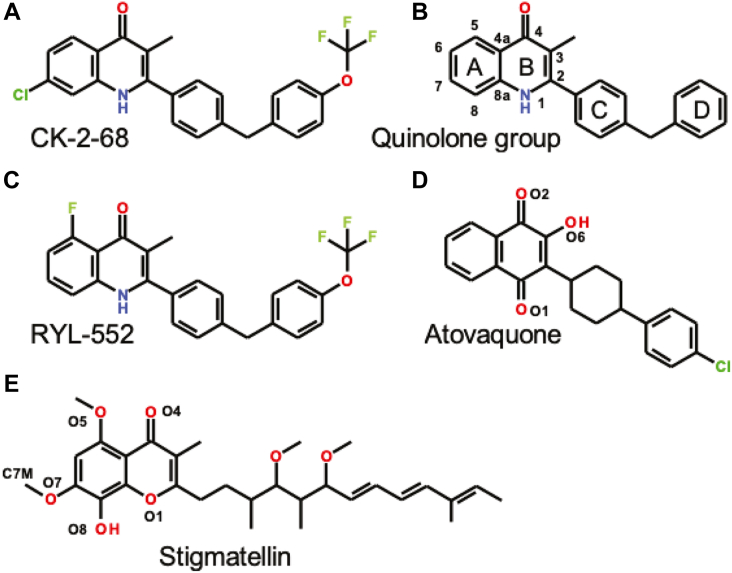

A distinct feature of the Plasmodium species' ETC is the lack of a classic mitochondrial Complex I (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase), which typically feeds two electrons into the quinone/quinol pool of the mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM) and couples the electron transfer (ET) to proton translocation across the MIM. Instead, the Plasmodium ETC uses an alternate NADH dehydrogenase, also known as NADH dehydrogenase type 2 (NDH2), to reduce the quinol/quinone pool. However, unlike the classic Complex I, NDH2 does not couple this process to proton pumping (4, 5). Conceivably, Plasmodium NDH2 could be an alternate target in the ETC for antimalarials. In fact, the antimalarial compound CK-2-68 (Fig. 2A) was specifically designed to inhibit NDH2 of P. falciparum (PfNDH2) (6, 7) instead of mitochondrial Complex III. Parasite growth and proliferation were shown to be inhibited effectively by this compound. A subsequent crystal structure determination of PfNDH2 (PDB:5JWC) with bound RYL-552 (Fig. 2C), a close analog of CK-2-68, demonstrated binding to two distinct regions apart from the catalytic site, leading to the proposal of an allosteric mechanism for the compound’s action on the enzyme (8).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of a few cyt bc1inhibitors.A, CK-2-68, (B) nomenclature for quinolone-type compounds, (C) RYL-552, (D) atovaquone, and (E) stigmatellin.

However, evidence has been accumulating that contradicts NDH2 as the principal target for P. species for growth inhibition by CK-2-68 and RYL-522. Selection experiments with each of these compounds on P. falciparum yielded surviving blood-stage parasites with mutations in Complex III but not in PfNDH2 (9). These mutations were found to be clustered around the QP site of the cyt b subunit (Fig. 1B). Further, a dispensable role of PfNDH2 in the blood-stage parasites was demonstrated when a knockout of the gene did not impede the parasites' survival (10, 11). Together, these findings indicate that the lethal antiparasitic action of CK-2-68 and RYL-522 is achieved by inhibition of Complex III, even though the compounds bind to PfNDH2 as well. Surprisingly, in a recent crystal structure of bovine Complex III with CK-2-68 (Protein Data Bank release PDB: 6ZFT), the bound inhibitor was modeled at the QN site of cyt b subunit of bovine mitochondrial cyt bc1 (Btbc1). However, the overall size and shape of the inhibitor CK-2-68, including its electron-rich aryl chloride moiety, correlated poorly with the map (Fig. S3). The binding of CK-2-68 at the QN site is also difficult to reconcile with the observed resistance mutations that cluster around the QP site (Fig. 1B) (9).

Plasmodium mitochondrial Pfbc1 has not been overexpressed and made available in purified form for biochemical and structural studies. In lieu of this highly desirable enzyme for screens and assessments of antimalarial compounds, isolated bovine heart mitochondria, its membranes, or isolated yeast Complex III have often been used (12, 13, 14, 15). Here we present a cryo-EM structure of CK-2-68 bound to Btbc1. The inhibitor CK-2-68 binds to the QP site of Complex III and arrests the extrinsic domain of ISP subunit (ISP-ED) at the cyt b subunit or b-site. These findings, along with the development of a corresponding model for Pfbc1 with CK-2-68, provide insights into the inhibitor’s wide therapeutic window as well as the effects of resistance mutations that can be selected by CK-2-68 and related compounds.

Results and discussion

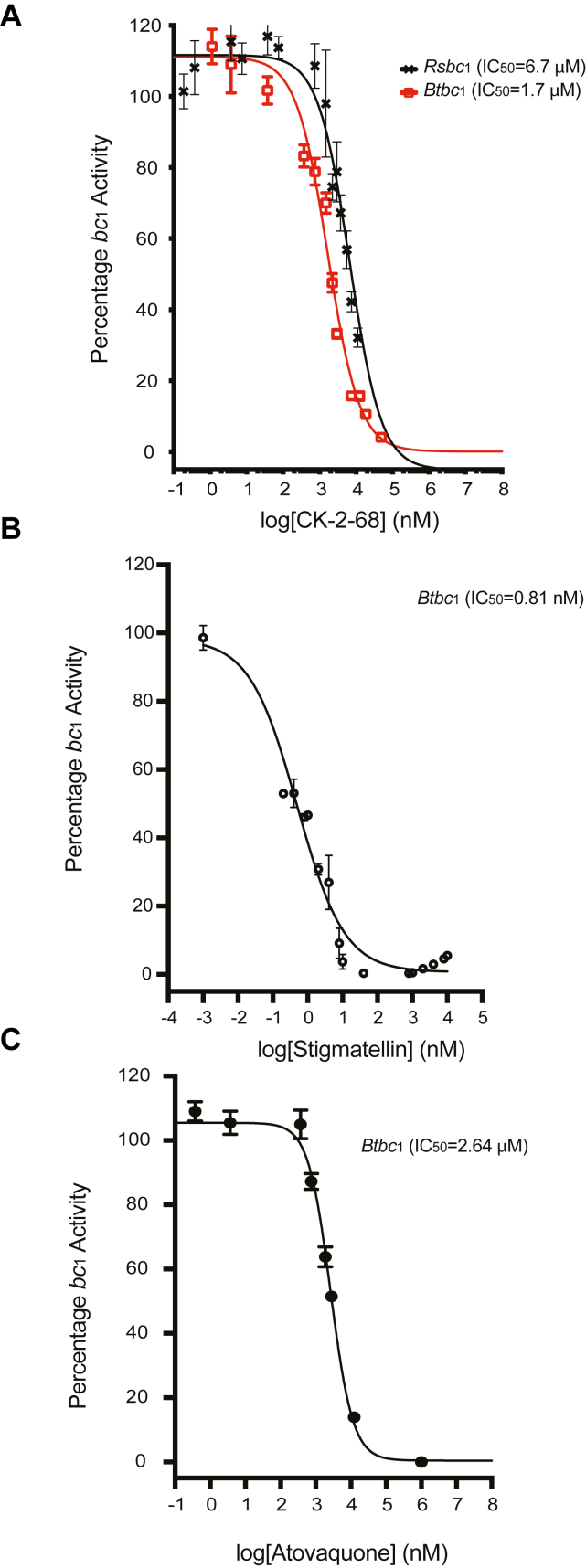

Inhibition of mitochondrial and bacterial cyt bc1 complexes by CK-2-68

In our previous work (16), we showed that bovine heart mitochondrial cyt bc1 (Btbc1) serves as a good proxy for human Complex III, whereas cyt bc1 from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Rsbc1) often represents fungal pathogens well. Consistent with the deep evolutionary differences between these complexes, Btbc1 and Rsbc1, yielded half-maximum inhibition (IC50) values of 418 nM and 1.4 nM, respectively, with the well-established fungicide famoxadone (16). For the present study, we tested CK-2-68 against Btbc1 and Rsbc1 and obtained IC50 values of 1.7 μM and 6.7 μM, respectively (Fig. 3A). Compared to the inhibition of Btbc1 by the classic respiratory inhibitor stigmatellin (Fig. 2E), which has an IC50 value of 1 nM (Fig. 3B), CK-2-68 is a much weaker inhibitor of Btbc1. In addition, CK-2-68 was slow to reach full inhibitory capacity in our assay against Btbc1 requiring an incubation time of >20h as compared to classic compounds like myxothiazol, stigmatellin, and UHDBT (5-n-undecyl-6-hydroxy-4,7-dioxobenzothiazole), which typically required less than 5 min (16, 17).

Figure 3.

Dose-dependent inhibition of Btbc1and Rsbc1activities by Complex III inhibitors. The activities of Btbc1 and Rsbc1 were assayed following the reduction of substrate cyt c. The effect of bc1 inhibitors was measured by pre-incubating bc1 with various concentrations of inhibitors for a specific amount of time prior to the measurement of cyt bc1 activity. The IC50 value for each inhibitor was calculated from at least three replicates by a least-squares procedure fitting the equation (Y = Amin + (Amax – Amin)/(1 + ) implemented with Prism software, with Amax and Amin indicating maximal and minimal activities, respectively. (A) CK-2-68, (B) stigmatellin, and (C) atovaquone.

Although an assay to test the inhibition of isolated Pfbc1 is yet to be developed, it is clear from the mutations obtained by selection experiments that Pfbc1 is a major target of CK-2-68. Its efficacy falls into the 40 nM range for wild-type P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes (9). This suggests that CK-2-68 may have a ∼100 times higher affinity for Pfbc1 than for Btbc1 or Rsbc1. Considering this difference, we measured the inhibition of Btbc1 by atovaquone resulting in an IC50 value of 2.6 μM, which is in the same range as that for CK-2-68 and reflective of its potentially wide therapeutic window (Fig. 3C). Given that atovaquone inhibits P. falciparum wild-type lines at ∼13 nM (IC50) (18), questions for further exploration are whether similarly wide IC50 differences may also be obtained with CK-2-68 against P. falciparum and important flora of the human microbiome, and whether both drugs share a common mechanism favoring binding to Pfbc1.

Structure of Btbc1 with bound CK-2-68 determined by cryo-EM

We carried out cryo-EM experiments to determine the structure of dimeric Btbc1 in complex with CK-2-68 (Table 1). Isolated Btbc1 was incubated with CK-2-68 in a molar ratio of 1:10 overnight. The complex was then transferred to EM grids for imaging under cryogenic conditions. A data set of 6960 movies was collected. 2D and 3D classifications allowed the selection of one class (454,182 particles) for further analysis (Fig. S1A and Table 1). Multiple rounds of 3D classifications were performed manually by limiting the alignment resolution progression stepwise from 12 Å to 4.8 Å, resulting in better resolved EM density for the bound inhibitors (Fig. S1B). The structure of Btbc1 was determined initially with imposed C2 symmetry, which was later relaxed. All subunits were clearly resolved in the final EM map that was determined to have an overall resolution of 2.9 Å resolution (Fig. S2) and has estimated local resolutions in the range between 4.0 to 2.8 Å (Fig. S1, C and D).

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics for Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex

| Data collection | |

| Grid type | Quantifoil R1.2/1.3400 mesh copper |

| Microscope | FEI Titan Krios |

| Detector | Gatan K2 Summit (4K x 4K) |

| Magnification | 58,275 |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 |

| Energy filter slit (eV) | None |

| Image mode | Super resolution |

| Electron dosage (e-/Å2) | 50.24 |

| Electron dose per frame (e-/Å2) | 1.0048 |

| Defocus range (μm) | −1.25 to −2.5 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.858/0.429 |

| Raw micrographs | 6960 |

| Data processing | |

| Extracted initial particles (no.) | 883,119 |

| Selected final particles (no.) | 454,182 |

| Particles for final map (no.) | 454,182 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 2.88 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial model used (PDB code) | 1SQX |

| Model resolution (Å) | 2.88 |

| Map sharpening B-factor (Å2) | −90.0 |

| Model composition | |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 32,742 |

| Protein residues | 4126 |

| Ligands | 10 (2 for inhibitors) |

| B-factors (Å) | |

| Protein | 72.4 |

| Ligand | 64.2 |

| Rms deviation | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (o) | 0.711 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 97.31 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.65 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.04 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 1.03 |

| Clashscore | 1.52 |

| Poor rotamers | 0.26 |

| PDB ID | 7TZ6 |

| EMDB ID | 26,203 |

The present 2.88 Å cryo-EM map of the homo-dimeric Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex exhibits clear density for the inhibitor (Fig. 4, A and B) bound at the distal pocket of both QP sites. Even though C2 symmetry was not enforced during refinement and reconstruction, inhibitors at both QP sites feature the same density, indicating symmetry-induced bias does not apply in the reconstruction. The structure of CK-2-68, as a member of the quinolone family of compounds, consists of four aromatic rings (Fig. 2B): the A and B rings forming the quinolone moiety, the middle C ring, and the terminal D ring made of trifluoromethoxy benzene. The QP pocket is made of a highly conserved, hydrophobic active site and a connecting, less conserved access portal. While the quinolone toxophore (A and B rings) of CK-2-68 is deeply embedded in the conserved part of the active site, its tail (C and D rings) remains at the access portal (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Binding of CK-2-68 to the QPsite revealed by the structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex.A, binding of CK-2-68 to the cyt b subunit of bovine Complex III. Cyt b and adjacent subunits ISP and cyt c1 are shown as molecular surfaces and are colored light gray, pale yellow, and pale blue, respectively. To reveal the entire inhibitor in the QP pocket, part of the molecular surface is cut away. The experimental electron density for the inhibitor is shown as a wire cage contoured at 5σ and colored in blue, into which a stick model of CK-2-68 was fit. B, view of CK-2-68 binding from the access portal to the QP pocket. When the surface of the cyt b subunit is kept intact, only the tail portion (C and D rings) of the bound CK-2-68 can be seen with the view of the quinolone moiety obscured. The surface is colored qualitatively by hydrophobicity from black (hydrophobic) to blue (hydrophilic). C, side view of the cyt b subunit showing the sequence conservation of the access portal to the QP site with bound CK-2-68. The cyt b is rendered as a semi-transparent calculated electron density by Chimera overlaid with the stick model. Residues that are conserved between Btbc1 and Pfbc1 are colored gray, while those that differ are colored red. The surface around the access portal is not conserved. D, top view (as seen from IMS with ISP removed) of the same surface as in (C) showing the conserved binding environment for the quinolone moiety of the CK-2-68.

The atomic model of the Btbc1 dimer built into the EM density reveals that the extrinsic domains of the iron-sulfur-protein (ISP-ED) are firmly docked at the cyt b subunit (b-site) between the ef-loop and the cd1 helix (Figs. 1B and S2). In the active enzyme, the docking of ISP-ED at the b-site is required as the 2Fe-2S cluster needs to be in proximity (H-bond distance) to the substrate (ubiquinol/ubisemiquinone) (19). Inhibitors like stigmatellin, famoxadone, jg144, UHDBT, and 2-n-nonyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide (NQNO) that cause ISP-ED to stay fixed at the b-site are Pf-type inhibitors (20). Thus, CK-2-68 qualifies as a Pf-type inhibitor. Conversely, Pm-type inhibitors for example azoxystrobin, myxothiazol, MOA-stilbene, and even the absence of inhibitor (apo form) cause increased mobility of the ISP-ED (20, 21). In general, when ISP-ED is not docked at cyt b, it is only restrained by its N-terminal TM helix but otherwise free to adopt a multitude of conformations along the pathway between cyt b and cyt c1 (22).

A so far unpublished 3.30 Å resolution crystal structure of CK-2-68 bound to Btbc1 (PDB:6ZFT) (23), deposited by Amporndanai et al. and released by the Protein Data Bank (PDB), contains a CK-2-68 molecule modeled at the QN site (Fig. S3A). At the same time, no substrate/inhibitor is bound at the QP site, and the ISP-ED is close to cyt c1 subunit (the c1-site). At the QN site, CK-2-68 binds via its 4-oxo group to the highly conserved cyt bHis201. This histidine is a critically important residue that is situated close to the high-potential heme bH. In our structure, however, we did not observe density compatible with the shape and size of the inhibitor at the QN site (Fig. S3B). Careful inspection of the deposited diffraction data shows that the observed experimental density (contoured at 1σ) extends only across the quinolone ring (Fig. 2B, rings A and B) but fails to cover rings C and D of CK-2-68. Thus, the electron density map calculated with deposited diffraction data does not support the presence of the inhibitor at the QN site with sufficient certainty. Furthermore, the fact that the observed resistance mutations in Plasmodium occur exclusively in the QP site calls into question the placement of the inhibitor at QN site. In fact, in numerous crystal structures, density in the vicinity of the catalytic histidine residue (cyt bHis201) was commonly interpreted as endogenous ubiquinone or fragments of it (24).

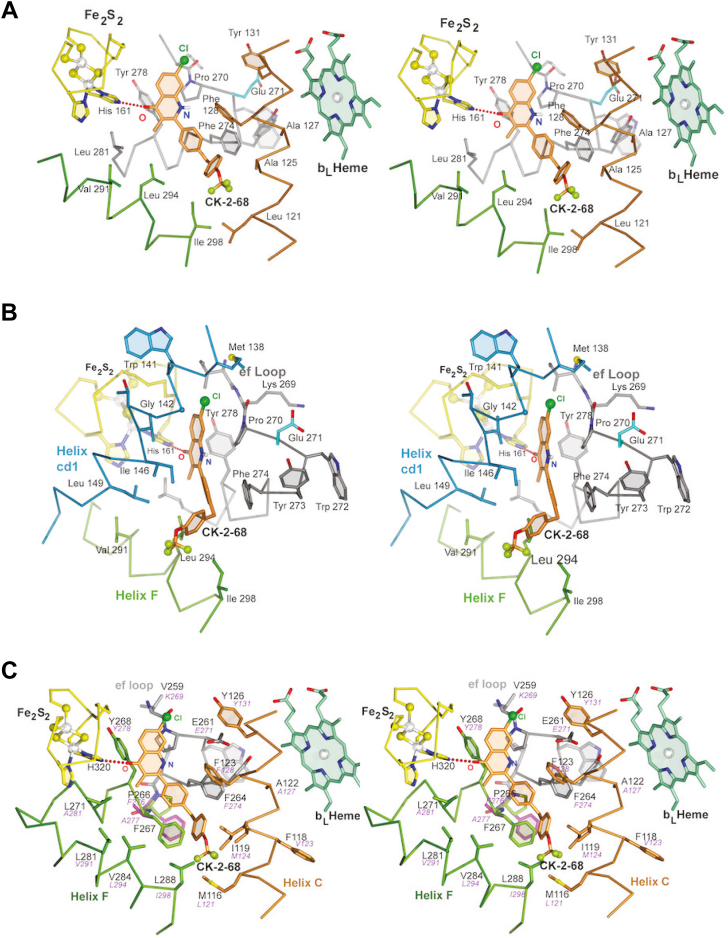

The binding environment of CK-2-68 in the cyt b subunit

In our structure, CK-2-68 binds to the BTcyt b subunit in the QP pocket with its 4-oxo atom of the quinolone moiety serving as an acceptor of a hydrogen bond (2.77 Å) from a likely protonated ISPHis161BT (Figs. 1 and 5, A, and B). In contrast to stigmatellin (Fig. 2E), CK-2-68 has no functional group in position eight of the quinolone group (see Fig. 2B), which could directly engage cyt bGlu271BT (cyt bGlu261PF, Figs. 6 and 5, A, and B). The acidic residue Glu271 is part of the highly conserved PEWY sequence and is largely considered to aid with the removal of a proton from the substrate ubiquinol. The side chain of Glu271 adopts two dramatically different conformations. Consistent with its function, the carboxylate side chain may exist in the "in-conformation" induced for instance by stigmatellin, which inserts between cyt bGlu271 and the ISPHis161 (Fig. S4A), or the "out-conformation" induced by inhibitors like UHDBT (20) or atovaquone (Fig. S4B). In the cryo-EM structure, the side chain of Glu271 is clearly in the out-conformation (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, there is no indication of a water-mediated interaction between the amine in position one of the inhibitor and the glutamate residue. The present conformation of Glu271 is reminiscent of the analogous 3.04 Å crystal structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyt bc1 (Scbc1)/atovaquone that clearly shows Glu272SC in the out-conformation, that is, pointing away from the carbonyl atom O1 of atovaquone (15) (Fig. S4B).

Figure 5.

Binding environment of Complex III inhibitors targeting the QPsite. The QP pocket of the cyt b subunit is represented by stereographic pairs with Cα-atom traces (47, 48) of the Helix C (residues 109–133) in brown, the cd1 helix (residues 137–155) in blue, the Helix F (residues 287–308) in green, and the ef loop (residues 245–287) in gray. Residues that are interacting with the inhibitor are rendered as stick models and have labels attached. The heme bL is also shown as a stick model in green. The ISP subunit near the Fe2S2 cluster is shown as a stick model in yellow. A, the CK-2-68 binding environment revealed by cryo-EM Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex structure. The bound CK-2-68 is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, oxygen in red, fluorine in yellow-green, and chlorine in dark green. B, the CK-2-68 binding environment as viewed from (A) by a 90° vertical rotation. C, a model of Pf cyt b with CK-2-68 placed at its QP site generated by superimposing the solved structure of Btbc1:CK-2-68 (this work), focusing on the inhibitor binding environment. Residues that are in contact with the inhibitor are labeled with those from Pfbc1 in black and those from Btbc1 in magenta. Note that residues interacting with the rings C and D of CK-2-68 are less conserved. Also, the side chains of F266 BT and A277BT are drawn in magenta to highlight the sharp contrast between P266 PF and F267PF. This pair of residues are close enough to influence the binding of CK-2-68.

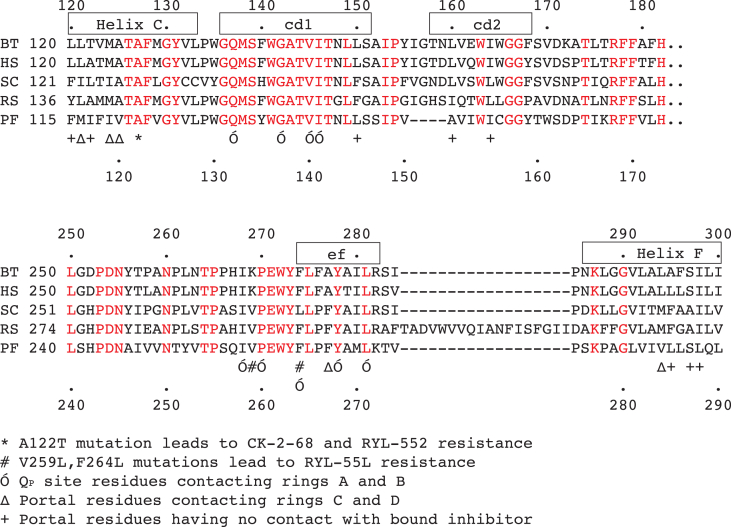

Figure 6.

Alignment of cyt b sequences around the QPpocket. Sequences from the cyt b subunits of Btbc1 (BT, Bos taurus), Hsbc1 (HS, Homo sapiens), Scbc1 (SC, Saccharomyces cerevisiae), Rsbc1 (RS, Rhodobacter sphaeroides), and Pfbc1 (PF, Plasmodium falciparum) were aligned based on the structures. Only a portion of the alignment is shown that focuses on the QP pocket. Conserved residues in the alignment are colored in red. Helical secondary structural elements are indicated by rectangles above the alignment and are labeled.

The chlorine atom in position seven of CK-2-68 is matched with the methoxy group (O7-C7M) of stigmatellin and is well positioned in a hydrophobic pocket allowing it to maximize van-der-Waals interactions. This is consistent with the observation that bulky groups are more readily accommodated in position seven than in position six (Fig. 2B), where bulky groups might collide with cyt b Ile268BT (cyt bIle258PF) or even clash with the docked ISP head domain specifically with the disulfide bridge ISPCys144-Cys160 (Fig. 5B). In CK-2-68, position five remains unsubstituted and differs here from RYL-552 and stigmatellin, which have a fluoro or methoxy group, respectively (Fig. 2, C and E). Inhibitory efficacy may be sensitive to the bulk or chemical nature of a group in position five. However, the methyl group in position three is well accommodated in a hydrophobic and aliphatic environment.

The C and D rings of CK-2-68 also contribute interactions to the binding to Btbc1. The C-ring (Fig. 2B) makes a 40° angle with the 4-quinolone ring and finds optimal support provided by cyt bPhe274BT (cyt bPhe264PF) through π-π aromatic interactions (Fig. 5B). Notably, in the sequence of Scbc1, this aromatic residue is replaced by the aliphatic cyt bLeu275SC, eliminating the possibility of π-π interactions (Figs. 6 and S4B). Finally, in our structure, the inhibitor’s para-OCF3 phenyl ring (D-ring) leans against cyt bMet124BT (cyt bIle119PF). The terminal trifluoromethoxy group remains at the entrance of the portal and is supported by cyt bAla125BT (cyt bVal120PF), albeit weakly, as the density is fading out.

While quinolone (CK-2-68), hydroxy naphthoquinone (atovaquone), and chromone (stigmatellin) toxophores are quite similar, the supporting tails of these inhibitors differ substantially in composition and complexity. The tails of inhibitors generally occupy space provided by the QP site’s access portal which appears capable of modulating the binding affinities by providing species-specific surface contacts (16). The importance of the terminal substitution of the inhibitors may go beyond a mere supporting role of the toxophore but rather determine directly how inhibitors discriminate cyt bc1 complexes between the pathogen and host and indirectly influence the development of resistance mutations as will be discussed below.

Model of Plasmodium falciparum cyt bc1 suggests differential interactions with CK-2-68 are important for a wide therapeutic window

The fact that the measured IC50 value of CK-2-68 binding to Btbc1 is only 1.7 μM compared to that of 40 nM for its growth inhibition of Plasmodium parasites indicates that the interactions observed in the structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 should be different from those in Pfbc1/CK-2-68. Since the structure of Pfbc1 was not available, we used AlphaFold 2 (25) to generate a model of the catalytic core of Pfbc1 consisting of cyt b, cyt c1, and ISP only. The resulting Pfbc1 model matches the structure of Btbc1 quite well, giving rise to a root-mean-square (rms) deviation of 1.468 Å for 376 aligned residues of the cyt b subunits (Fig. S5). The superposed structures allowed the modeling of CK-2-68 binding to the Pfbc1 (Fig. 5C). Careful inspection of the CK-2-68 molecule bound to Btbc1 and Pfbc1 revealed that, while the quinolone moiety (A and B rings) is deeply embedded in the QP active site and surrounded by conserved residues, the C and D rings of the inhibitor remain mostly in the access portal outside the active site, where residues are much less conserved (Figs. 4, C and D, 5C and 6). A similar observation was previously reported for atovaquone bound to Scbc1, where its chlorophenyl-cyclohexyl tail occupies the less conserved part of the QP pocket (15). Thus, we expect that the major difference in binding affinity should derive from C and D rings interacting differently with residues lining the access portals of Btbc1 and Pfbc1, presumably providing more favorable interactions for Pfbc1. It is possible that the D ring may adopt a very different conformation in Pfbc1 than what we observed in the current Btbc1/CK-2-68 structure. This type of conformational adaptation to the various portal environments was previously seen in the differential binding of famoxadone to Btbc1 and Rsbc1 (16).

A structure-based sequence alignment of the cyt b subunits from Btbc1, Hsbc1, and Pfbc1 allowed mapping of sequence conservation onto the structure (Fig. 4, C and D), which demonstrated nearly complete sequence conservation in the QP pocket (Fig. 4D) except in its portal (Fig. 4C). Thus, the sequence and structure conservation in the QP site likely leads to binding of the toxophores, the A and B rings (Fig. 2) of CK-2-68 and atovaquone, to be identical for both Pfbc1 and Hsbc1. However, the lack of structural (and sequence) conservation in the portal region, where the C and D rings of CK-2-68 or the chlorophenyl-cyclohexyl tail of atovaquone bind, allows for differentiation in inhibitor binding between Pfbc1 and Hsbc1, enabling the observed wide therapeutic windows for both compounds. This observation is in complete agreement with the analyses of structure–activity relationship (SAR) during drug development. For example, most of the compounds synthesized in the SAR study of atovaquone were those having changes in the tail to reduce toxicity, while the toxophore (hydroxynaphthoquinone) remained relatively stable from the beginning (26). Similarly, SAR optimization of CK-2-68 focused predominantly on the tail part, whereas the quinolone moiety remained fixed (6, 7).

Further insights into the molecular interactions of resistance mutations in the cyt b subunit of Pfbc1

The cryo-EM structure of the Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex and the structural model of Pfbc1 set the stage for further understanding of the PfcytB mutations and their roles in drug resistance. The great similarity of the quinolone inhibitors (CK-2-68 and RYL-552, Fig. 2) prompted us to look into the differential effects caused by resistance mutations after imposing RYL-552 selection pressure (9). Clones obtained with either mutation cyt bF264LPF (cyt bF274BT) or cyt bV259LPF (cyt bK269BT) exhibited somewhat greater or approximately the same relative increase in resistance to RYL-552 than to CK-2-68 (9). Of these, the cyt bF264LPF mutation likely causes a loss of interactions (π−π) with ring C of RYL-522 and similar compounds (Fig. 5, A and B). While a phenylalanine residue at this position immediately following the PEWY motif is largely conserved in many species, this residue is naturally a leucine (cyt bL275SC, Fig. 6) in yeast. This observation may help explain why the F->L mutation causes only a relatively small, ∼3 - 4-fold, increase in the EC50 values of RYL-552- and CK-2-68-resistant Plasmodium mutants. We note that this change from F->L plays an important role in the binding of a series of oxazolidine-type antifungals such as famoxadone, where it alters a network of π−π aromatic interactions. For example, in yeast, the cyt bL275FSC mutation gives rise to a 20-fold reduction in the IC50 value of famoxadone (27, 28, 29).

More subtle is the effect of the cyt bV259LPF (cyt bK269BT) mutation immediately before the conserved PEWY motif. It is a residue in the vicinity of the binding site, but its side chain points away from the active site toward the aqueous mitochondrial intermembrane space (Fig. 5B). The equivalent residues are cyt bK269BT, cyt bV270SC or cyt bV293RS of the ef loop (Fig. 6). A change from valine to the slightly larger leucine may exert some strain on the backbone, causing the proline residue cyt bP260PF (cyt bP270BT) to diminish its support for ring A of the inhibitor (or the natural substrate). A better understanding of the cyt bV259LPF mutation will require additional insights into the structure-function relationships of P. falciparum complex III as a dynamic system.

Clones were also obtained with a cyt bA122TPF (cyt bA127BT) mutation after exerting selection pressure with either RYL-552 or CK-2-68. These clones exhibited low to moderate increase in EC50 of ∼3 to 4 fold but interestingly showed relatively higher levels of resistance against CK-2-68 than against RYL-552. The cyt bA127BT residue resides in the highly conserved C-helix of the cyt b subunit (Figs. 5A and 6), where it is not involved in direct contact with CK-2-68 but is rather a part of the heme bL environment. This observation suggests that the cyt bA122TPF mutation may alter the binding environment for the quinolone toxophore. In our model (Fig. S6), the replacement of cyt bA127BT with threonine may enable the formation of a hydrogen bond with the OH atom of a nearby cyt bY273BT (cyt bY263PF). Dislodging the aromatic side chain of cyt bY273BT could lead to a destabilized cyt bF274BT (cyt bF264PF) and loss of the π−π interactions with ring C of RYL-552 as well as CK-2-68. Another possible way that a cyt bA127TBT (cyt bA122TPF) mutation might confer resistance is by forming a hydrogen bond triad from cyt bT127 BT via cyt bY273BT to cyt bE271BT (Fig. S6), which could influence the position of the preceding residue cyt bP270BT. The very highly conserved residue cyt bP270BT forms, together with cyt bG142BT of the cd1 helix, a narrow gap that accommodates ring A of the inhibitor (Figs. S7 and S5). A glycine-to-alanine mutation is frequently observed in plant pathogens in response to commercial fungicides like azoxystrobin (30). This change incurs a performance penalty emphasizing the importance of the Gly-Pro gap even for the native substrate ubiquinol.

Comparison of resistance mutations against CK-2-68 and atovaquone

The superposition of the cyt b subunits of the structures of Btbc1/CK-2-68 and Scbc1/atovaquone (PDB:4PD4) shows that CK-2-68 and atovaquone occupy nearly the same space within the QP pocket (Figs. 5A, S4B, and S8). The toxophore of atovaquone is pulled deeper into the distal part of the QP pocket with its deprotonated hydroxyl group (O6) binding to ISPHis181SC (Figs. 2D, S4B, and S8) (15). The carbonyl group (O2) of atovaquone appears to be outside the range of hydrogen bonds. This contrasts with CK-2-68 which has no equivalent hydroxyl group but instead uses its carbonyl oxygen atom (O4) to engage ISPHis161BT (Fig. 5A). It is interesting to note the very different atovaquone and CK-2-68 responses of P. falciparum containing the cyt bY268SPF mutation (cyt bY278BT, cyt bY279SC)- a mutation in cyt b subunit of Plasmodium identified in infected patients undergoing atovaquone treatment (31). Residue Y278 is highly conserved (Fig. 6) and known to form an H-bond with the main chain carbonyl oxygen atom of ISPC160 (Fig. S8). While atovaquone suffers a dramatic loss in inhibitory efficacy, with an EC50 rising from 1.1 nM in wild-type to over 6760 nM in cyt bY268SPF mutant parasites of the 106/1 line, CK-2-68 gained some efficacy against these same mutant parasites (9). Remarkably, an inspection of the superposed structures reveals that both atovaquone and CK-2-68 are well within the range of beneficial aromatic π-π interactions (Fig. S8). The rigid tyrosine residue contacts the B-ring of atovaquone or CK-2-68 through edge-to-edge interactions. In the superposition, the B-rings of the inhibitors are in the same plane but due to the deeper penetration of atovaquone into the QP site, they are off-set by ∼1.7 Å (Figs. 5A, S4B, and S8). In fact, CK-2-68 seems to benefit more from the stabilizing influence of this aromatic ring and the H-bonding system. Yet, the cyt bY268SPF mutation is devastating for the binding or inhibitory action of atovaquone even as it has very little effect on the relative efficacy of the quinolone-type inhibitors. Thus, the difference may lie with the introduction of the disruptive serine-based hydrogen bond. Although the hydroxyl group of serine may H-bond to atovaquone's O6 hydroxyl group as well as O4 of CK-2-68 (Fig. S8), the phenolic hydroxyl group (O6) of atovaquone was shown to be deprotonated for binding (15) with no equivalent requirement for CK-2-68. The negatively charged atovaquone may interact with K272 (R282 in Btbc1) directly in the Y278S (Y268SPF) mutant with enough strength to alter the inhibitor's orientation and hinder it from engaging the histidine residue of Fe2S2-cluster.

Differences in the conformations of the tail sections of the inhibitors may play a role in how strongly the inhibitor reacts to changes in the environment. In contrast to the larger and curved system of methylene-linked C and D rings in CK-2-68, atovaquone has a relatively short, rigid tail, which does not follow the curvature of the channel very well but stays mostly straight. This reduction in support through a mostly rigid tail portion may make atovaquone more sensitive to losses in the portions that stabilize the toxophore.

Relationship of CK-2-68 with its close relatives and active site switching

Compounds with quinolone templates have been considered potential antimalarials since 1947 (32). These compounds closely resemble the substrate ubiquinone, potentially enabling them to target either the QN or QP site or both. Indeed, crystallographic studies of the quinoline-type cyt bc1 inhibitor NQNO revealed its ability to bind to both QN and QP sites (20). Other quinolones and pyridones have also been investigated for their potential antimalarial activities, and in crystal and cryo-EM structures, several of these compounds were found to specifically bind to the QN site of cyt bc1 (33, 34, 35, 36). The results of our present study show that a dramatic and complete switch of binding from the QN to the QP site can be attributed to the single chlorine atom that was introduced at position seven of the quinolone moiety in compound CK-2-67 to produce CK-2-68(12). Indeed, the halogen-free CK-2-67 and its isomer WDH-1U-4 (Fig. S9) have been shown to be QN-site inhibitors by crystal structure analysis (34), although it was speculated that they may fit into both sites. However, it should be noted that WDH-1U-4 has the bulky aryl side chain attached to position 3, instead of position 2, of the quinolone moiety, which makes it less likely for the toxophore to properly bind in a classic way (Fig. S6).

In our structure with bound CK-2-68, the 7-chloro-quinolone moiety binds in a conserved environment forming π−π interaction between side chains of cyt bY278BT (cyt bY268Pf) and the A and B rings. The chlorine atom penetrates deeply into the active site and is surrounded by backbone atoms from residues cyt bW141BT, cyt bMET138BT, and cyt bK269BT (cyt bW136Pf, cyt bMET133Pf, and cyt bV259Pf, Fig. 5, A and B). In a previous report investigating the QP and QN preference by quinolone-type inhibitors (37), it was shown that QN site inhibition was associated with compounds containing halogen atoms in position six or aryl groups in position 3, while QP site inhibition was favored by 5,7-dihalogen groups or 7-position substituents. Additionally, it was suggested that the 4(1H)-quinolone scaffold is compatible with binding to either site of cyt b and that minor chemical changes can influence QP or QN site selection.

Implications for further development of antimalarials

Our results show dose-dependent inhibition of Btbc1 and Rsbc1 by CK-2-68, with IC50 values of 1.7 and 6.7 μM, respectively (Fig. 3A), which are much weaker than those of the classic cyt b inhibitor stigmatellin (Fig. 3B). By contrast, the inhibition of wild-type malarial parasites by CK-2-68 at ca. 40 to 70 nM levels indicates effective discrimination between Pfbc1 and Btbc1, just as the FDA-approved antimalarial agent atovaquone, which is effective on Plasmodium Complex III at nanomolar levels while it binds weakly to Btbc1 (IC50 = 2.63 μM) (Fig. 3C). Since Btbc1 is a good proxy for human Complex III, compounds inspired by CK-2-68 and the models of Pfbc1/Btbc1 pair may help to find novel leads with wide therapeutic windows.

Despite its relatively low affinity toward Btbc1, CK-2-68 formed a stable complex with bovine Complex III and allowed a structure determination by cryo-EM with the inhibitor bound at the highly conserved QP site. The structure lends support to the idea that CK-2-68 might target both enzymes PfNDH2 and Pfbc1. Consistent with the locations of resistant mutations described in the literature (9), our structure shows the binding of CK-2-68 at the QP site of Complex III. Thus, our findings contrast that of PDB entry 6ZFT which shows CK-2-68 modeled at the QN site. Our structure also offers new information with respect to inhibitor binding including those that involve π−π aromatic and H-bond interactions with cyt b and ISP subunits. The existence of these interactions provides new insights into the results from extensive SAR studies available in the literature (6, 7, 12) and provide guidance for prospective antimalarial drug development. Future drug screenings might involve more compounds with the alternate, aromatic tautomer (quinolines), as well as derivatives with functional groups in position 8. It should be noted that some investigations into the proposed set of compounds were previously done by Pidathala et al. with promising results (IC50 ranging from 27 - 60 nM) from hetero-aromatic core B compounds (7). It may also be useful to introduce a methoxy group or halogen atom in position seven or five to increase the resemblance of interesting hits to stigmatellin.

The structure and sequence comparisons between Btbc1 and our Pfbc1 model illuminate the reasons for the wide therapeutic window of CK-2-68. In particular, the way CK-2-68 binds to Btbc1 vs. the Pfbc1 model differs in important interactions between the tail part of the inhibitor and residues lining the access portals to the enzymes’ QP sites. At the same time, the interactions of the quinolone toxophore with both enzymes are identical. By focussing on optimizing the terminal C and D rings while leaving the toxophore largely unchanged, future development of antimalarials may yield compounds with even wider therapeutic windows. New opportunities for drug design may also arise from an improved understanding of the subtleties arising from new substitution patterns on the quinolone toxophore and their ability to impose binding preferences on the QP or QN sites. Furthermore, the discovery of inhibitors that bind equally well to both sites would pose an especially steep challenge for the pathogenic organism to develop resistance as multiple simultaneous mutations may be required.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals

Cyt c (from horse heart, type III) and stigmatellin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-(10-bromodecyl)-1,4-benzoquinol (Q0C10BrH2) was prepared in-house as previously reported (38). N-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) and N-octyl-β-D-glucoside (β-OG) were purchased from Affymetrix. Sucrose mono-caprate was purchased from Fluka. All other chemicals were obtained commercially of the highest grade available.

Preparations of Rsbc1 and Btbc1

Btbc1 complex from beef heart was prepared starting from solubilization by deoxycholate the highly purified succinate-cyt c reductase, as previously reported (39). Contaminants were removed by a 15-step ammonium acetate fractionation. Purified Btbc1 complex in oxidized form was recovered from the precipitates formed between 18.5% and 33.5% ammonium acetate saturation. The final product was dissolved in 50 mM Tris•HCl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 0.66 M sucrose reaching a protein concentration of 30 mg/ml and frozen at −80 °C until use. The concentrations of cyt b and c1 were determined spectroscopically using millimolar extinction coefficients of 28.5 and 17.5 mM-1 cm-1 for cyt b and c1, respectively.

The purification procedure of wild-type Rsbc1 was the same as published earlier (40). Briefly, R. sphaeroides cells harboring the plasmid pRKDfbcFBCHQ coding for the wild-type Rsbc1 protein with a hexahistidine tag at the C-terminus of the cyt c1 subunit were grown photosynthetically. Chromatophore membranes were prepared by disrupting cells with a French press followed by differential centrifugations. To purify the His6-tagged Rsbc1, the chromatophore suspensions were adjusted to a cyt b concentration of 25 μM with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris•Cl (pH 8.0 at 4 °C), 20% glycerol, 1 mM MgSO4 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). DDM solution (10% w/v) was added dropwise to a final detergent-to-protein ratio of 0.57 (mg/mg). After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA column, which was washed with six column volumes of buffer A (50 mM Tris•HCl, pH 8.0 at 4 °C, 200 mM NaCl, 0.01% DDM), six column volumes of buffer A in the presence of 5 mM histidine and four column volumes of buffer B (50 mM Tris•HCl, pH 8.0 at 4 °C, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% β-OG) in the presence of 5 mM histidine. The protein was eluted with buffer B containing 200 mM histidine and the desired fraction was concentrated with a Centriprep-50 to yield a final cyt b concentration of 800 μM.

Measurement of inhibition of Btbc1 and Rsbc1 by CK-2-68 and other complex III inhibitors

Either Btbc1 or wild-type Rsbc1 was incubated with CK-2-68 at different concentrations at 4 °C for at least 20 h. Incubation time of 5 minutes for the runs with stigmatellin or atovaquone was used, whereas that for CK-2-68 was ∼20 h at 4 °C. Specific activities of Btbc1 and Rsbc1 were assayed following the reduction of substrate cyt c. The cyt bc1 preparations were diluted to a final concentration of 0.1 μM and 1 μM, respectively, for Btbc1 and Rsbc1 based on cyt b concentration in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris•HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.01% DDM. To a 2 ml assay mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.3 mM EDTA, and 100 μM cyt c, Q0C10BrH2 was added to a final concentration of 25 μM and the solution was split evenly into two cuvettes. To one cuvette, 3 μl of diluted cyt bc1 solution was added and recording of the cyt c reduction was started immediately at a wavelength of 550 nm for 60 s in a two-beam Shimadzu UV-2550 PC spectrophotometer at room temperature. The amount of cyt c reduced within 60 s was calculated using a millimolar extinction coefficient of 18.5 mM-1 cm-1. To measure the effect of inhibitors, cyt bc1 was pre-incubated with various concentrations of inhibitors for a specific amount of time prior to the measurement of cyt bc1 activity. The IC50 value for each inhibitor was calculated by a least-squares procedure fitting the equation (Y = Amin + (Amax – Amin)/(1 + ) implemented in a commercial package Prism, where Amax and Amin are maximal and minimal activities, respectively.

Cryo-EM grid preparation and data collection of Btbc1/CK-2-68

To prepare samples of Btbc1 in complex with CK-2-68 for cryo-EM study, the final concentration of purified Btbc1 complex was adjusted to 1 mg/ml in a solution containing 50 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.8, 20 mM ammonium acetate, 0.16% sucrose monocaprate (SMC) and 20 μM CK-2-68. This solution was incubated at 4 °C overnight. The Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex at 0.4 mg/ml was diluted in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.16% SMC, 20 μM CK-2-68 and centrifuged prior to grid freezing. Grids were glow discharged for 30 s at 15 mA current using an easyGlow discharge cleaning system (PELCO, TED PELLA, Inc). An aliquot of 3 μl of protein was dispensed onto Quantifoil R1.2/1.3400 mesh copper grids with 2 nm continuous carbon over holes (Quantifoil) followed by plunging into a liquid ethane bath.

Two datasets were collected in an automatic manner utilizing Latitude automated data acquisition software (Gatan Inc) on an FEI Titan Krios transmission electron microscope operating at 300 kV with a K2 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan Inc.). 2.5 s exposures were recorded in super-resolution mode (0.429 Å pixel-1) at the nominal magnification of 582,75× corresponding to a physical pixel size of 0.858 Å pixel-1 as 50-frame image stacks with a dose rate of 1.0048 e- Å-2 per frame for a total accumulated dose of ∼50.24 e- Å-2.

Image processing, map reconstruction, and structure refinement

Raw movies were imported as image stacks followed by gain reference correction and motion correction with dose filtering using the cisTEM package (41). CTF parameters were determined using the raw movie frames instead of aligned images. 883,119 particles were extracted (Fig. 3). Following 2D and 3D classifications, a data set was obtained and proceeded to refinement. The initial model was generated ab initio and was subjected to 3D auto-refinement with no imposed symmetry. Multiple rounds of 3D classification were performed manually by limiting the alignment resolution from 12 Å progressing stepwise to 8 Å, 7 Å, 5.95 Å, 5.5 Å, and finally to 4.8 Å. Using a lower resolution limit at 4.8 Å instead of 3.9 Å in auto refine led to a much better-resolved density of the inhibitor. The best class is extracted from the dataset and continued to be refined to 2.9 Å with 454,182 particles. An iterative model building and refinement procedure was carried out with the program Phenix (42, 43) and Coot (44), allowing stepwise extension of model resolution.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and an EM map have been deposited with EMD (45) with the ID code EMD-26203 and with the RCSB Protein Data Bank (46) with the PDB ID code of 7TZ6, for the Btbc1/CK-2-68 structure.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. The cryoEM work utilized resources supported by the NCI/NIH Intramural CryoEM Consortium (NICE). For this study, we utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. (https://hpc.nih.gov).

Author contributions

L. E., F. Z., A. Z., W. W., R. H., D. X. Investigation; L. E., R. H. Formal analysis; L. E., D. X. Writing – Original Draft; L. E. Visualization; C-A. Y., K. D. L. Resources; K. D. L., T. E. W. Writing – Review & Editing; T. E. W., D. X. Conceptualization; D. X. Methodology, Investigation; D. X. Supervision, D. X. Project Administration.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Phillip A. Cole

Supporting information

Data processing and statistics for the structure determination of Btbc1 in complex with CK-2-68 by cryo-EM. (a) A panel of selected representative 2D classes. (b) Workflow for the EM data processing and local resolution map of dimeric Btbc1/CK-2-68 structure contoured at 4σ level. (c) A local resolution map. The color code is given by the side strip. (d) Gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves of the final density map. The reported resolution for this structure was based on the FSC=0.143 criterion.

A representative view of the electron density map of Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex. Cryo-EM density at 2.88 Å resolution (blue) was contoured at 5σ level, containing refined stick models of cyt b (light gray), the inhibitor (brown) and the ISP (yellow) with its fixed extrinsic domain. The ISP-ED is seen in the fixed b-position as it interacts with CK-2-68 at the QP site.

Detailed comparisons of CK-2-68 binding sites: QN vs QP. (a) Depiction of the binding of CK-2-68 to the QN site in 6ZFT. The electron density calculated from a deposited X-ray diffraction data set 6zft_2fofc.dsn6 downloaded from the PDB databank was contoured at two levels: 1σ (blue) and 3σ (white). At the 1σ contour level, the rings A and B are covered by density, but the tail of the modeled CK-2-68 is not covered. At the higher contour level of 3σ, ring A has lost substantial portions of density whereas surrounding residues are still well covered. While the conformations of H201 and D228 would favour the presence of a QN occupant, it is more likely that residual and/or disordered ubiquinone was mistaken for CK-2-68. (b) The cryo-EM density for 7TZ6 (this work) showed in the same pocket as in (a) no sign of a bound inhibitor. The presence of spurious density is typical for this region when it is unoccupied. (c) The view of the QP site in 6ZFT showed no density for an inhibitor. The presence of additional density in the hydrophobic active site was modeled with a hydrophilic PEG-4 (polyethylene glycol fragments). The ISP is close to cyt c1 and therefore absent from the QP site. (d) The QP site of 7TZ6 (this work) shows clear density for CK-2-68, surrounding residues, and for the fixed ISP head domain (green).

Binding environment of two types of Complex III inhibitors targeting the QP site. The QP pocket is drawn as stereographic illustration. (a) The binding environment for stigmatellin is shown in the same orientation as seen in Fig. 5a. This structure was determined by X-ray crystallography for Btbc1/stigmatellin complex (PDB:1SQX)(20). The bound stigmatellin is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, and oxygen in red. The highly conserved residue E271 (side chain carbon atoms are cyan for emphasis) is in the “in-conformation”. The carboxylate group is forming a hydrogen bond (dotted lines) with stigmatellin (atom O8). (b) The binding environment of atovaquone is in the same orientation as seen above. This structure was determined for Scbc1/atovaquone complex by X-ray crystallography (PDB:4PD4)(15). Here the inhibitor atovaquone was rendered as stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, and oxygen in red and chlorine atom in green. The glutamic acid residue E272 (Sc numbering equiv. BTE271) is in the “out-conformation” despite the presence of atom O1 of atovaquone. However, atom O1 may still be too far away to engage the glutamate residue.

Superposition of the structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 with the model of Pfbc1 generated with AlphaFold 2. Two orthogonal views of the superposition are given. The structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex determined by cryo-EM is shown as a cartoon model in magenta. The hemes bL and bH are rendered as stick models with carbon atoms colored red, oxygen red and nitrogen blue. The bound CK-2-68 is also rendered as stick model with carbon in brown, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue and chlorine in green. The model structure of Pfbc1 in cartoon model is color green.

Potential changes to the QP site affecting binding of CK-2-68. The bound CK-2-68 is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue, chlorine in deep green and fluorine in light green. The QP site is depicted as CA traces with the cd1 helix (142-149) shown in blue, part of the Helix C (124-129) in green, and the ef loop (268-279) in gray. Side chains of important residues are shown as stick models and labeled. The highly conserved residue E271 is in the “out-conformation”. The A127T (A122T in Pfbc1) mutation is shown, which is not in direct contact with bound CK-2-68 but participates as part of the binding environment. Arrows in magenta are drawn to indicate potential interactions that might bring changes to the inhibitor binding environment.

The narrow opening of the QP pocket with bound CK-2-68. The Van der Waals surface of the QP pocket is overlaid with residues, shown in stick models, forming the narrow path for the quinolone moiety of the inhibitor CK-2-68, also shown as stick model. The narrowest part of the path is formed by residue P270 on one side and the G142 on the other side. The G142A is a common mutation identified in many pathogenic fungi. The Cβ atom of A142 is drawn as a cyan (transparent) van der Waals sphere and equivalently the chlorine atom of CK-2-68 is shown as a green sphere. The severe clashes are shown in red hashes suggesting that a hypothetical G137APF mutant would resist CK-2-68.

Superposition of cyt b subunits of CK-2-68 and atovaquone bound Complex III. Superposed cyt b subunits between Btbc1/CK-2-68 (PDB:7TZ6, this work) and Scbc1/atovaquone (PDB:4PD4) are shown as cartoon in green. The superposition brings CK-2-68 and atovaquone to overlap. Inhibitors are rendered as stick models with CK-2-68 in black and atovaquone in cyan. Oxygen atoms are colored in red and nitrogen atoms in blue. The ISP subunit is colored yellow with the 2Fe2S cluster, H161, and C160 shown as stick models and labeled. Y278 and its serine mutation are also shown as stick models. R282 (K272 for Pfbc1) that is shielded by Y278 becomes exposed to the bound inhibitors in the Y278S mutant.

Shapes of Inhibitors in comparison. Famoxadone (top) is a typical QP site inhibitor and so is CK-2-68 (Fig. 2a) owing to a very similar topology. Surprisingly, CK-2-67 (middle), which is lacking a chlorine atom in position 7, is a QN site inhibitor. It is speculated that it has the potential to bind to the QP site still, but its isomeric form WDH-1U-4 (bottom) is prevented from binding in the QP site due to a bulky group in position 3 (35).

References

- 1.Organization World Health. World Health Organization; Geneva (Switzerland): 2021. Global Malaria Programme. World Malaria Report 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava I.K., Morrisey J.M., Darrouzet E., Daldal F., Vaidya A.B. Resistance mutations reveal the atovaquone-binding domain of cytochrome b in malaria parasites. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:704–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessl J.J., Hill P., Lange B.B., Meshnick S.R., Meunier B., Trumpower B.L. Molecular basis for atovaquone resistance in Pneumocystis jirovecii modeled in the cytochrome bc(1) complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2817–2824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evers F., Cabrera-Orefice A., Elurbe D.M., Kea-Te Lindert M., Boltryk S.D., Voss T.S., et al. Composition and stage dynamics of mitochondrial complexes in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3820. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23919-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biagini G.A., Viriyavejakul P., O'Neill P M., Bray P.G., Ward S.A. Functional characterization and target validation of alternative complex I of Plasmodium falciparum mitochondria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1841–1851. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1841-1851.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung S.C., Gibbons P., Amewu R., Nixon G.L., Pidathala C., Hong W.D., et al. Identification, design and biological evaluation of heterocyclic quinolones targeting Plasmodium falciparum type II NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (PfNDH2) J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1844–1857. doi: 10.1021/jm201184h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pidathala C., Amewu R., Pacorel B., Nixon G.L., Gibbons P., Hong W.D., et al. Identification, design and biological evaluation of bisaryl quinolones targeting Plasmodium falciparum type II NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (PfNDH2) J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1831–1843. doi: 10.1021/jm201179h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y., Yu Y., Li X., Li J., Wu Y., Yu J., et al. Target elucidation by cocrystal structures of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase of Plasmodium falciparum (PfNDH2) with small molecule to eliminate drug-resistant malaria. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:1994–2005. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane K.D., Mu J., Lu J., Windle S.T., Liu A., Sun P.D., et al. Selection of Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome B mutants by putative PfNDH2 inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:6285–6290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804492115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boysen K.E., Matuschewski K. Arrested oocyst maturation in Plasmodium parasites lacking type II NADH:ubiquinone dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:32661–32671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ke H., Ganesan S.M., Dass S., Morrisey J.M., Pou S., Nilsen A., et al. Mitochondrial type II NADH dehydrogenase of Plasmodium falciparum (PfNDH2) is dispensable in the asexual blood stages. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biagini G.A., Fisher N., Shone A.E., Mubaraki M.A., Srivastava A., Hill A., et al. Generation of quinolone antimalarials targeting the Plasmodium falciparum mitochondrial respiratory chain for the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:8298–8303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205651109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biagini G.A., Fisher N., Berry N., Stocks P.A., Meunier B., Williams D.P., et al. Acridinediones: selective and potent inhibitors of the malaria parasite mitochondrial bc1 complex. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73:1347–1355. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capper M.J., O'Neill P.M., Fisher N., Strange R.W., Moss D., Ward S.A., et al. Antimalarial 4(1H)-pyridones bind to the Qi site of cytochrome bc1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416611112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birth D., Kao W.C., Hunte C. Structural analysis of atovaquone-inhibited cytochrome bc1 complex reveals the molecular basis of antimalarial drug action. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4029. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esser L., Zhou F., Zhou Y., Xiao Y., Tang W.K., Yu C.A., et al. Hydrogen bonding to the substrate is not required for rieske iron-sulfur protein docking to the quinol oxidation site of complex III. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:25019–25031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thierbach G., Reichenbach H. Myxothiazol, a new inhibitor of the cytochrome b-c1 segment of th respiratory chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;638:282–289. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(81)90238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsen A., LaCrue A.N., White K.L., Forquer I.P., Cross R.M., Marfurt J., et al. Quinolone-3-diarylethers: a new class of antimalarial drug. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:177ra37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elberry M., Xiao K., Esser L., Xia D., Yu L., Yu C.A. Generation, characterization and crystallization of a highly active and stable cytochrome bc1 complex mutant from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esser L., Quinn B., Li Y.F., Zhang M., Elberry M., Yu L., et al. Crystallographic studies of quinol oxidation site inhibitors: a modified classification of inhibitors for the cytochrome bc(1) complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esser L., Gong X., Yang S., Yu L., Yu C.A., Xia D. Surface-modulated motion switch: capture and release of iron-sulfur protein in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13045–13050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izrailev S., Crofts A.R., Berry E.A., Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics simulation of teh rieske subunit motion in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1753–1768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77022-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amporndanai K., O'Neill P.M., Hong W.D., Amewu R.K., Pidathala C., Berry N.G., et al. Worldwide Protein Data Bank; 2021. Crystal Structure of Bovine Cytochrome Bc1 in Complex with Quinolone Inhibitor CK-2-68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia D., Yu C.A., Kim H., Xia J.Z., Kachurin A.M., Zhang L., et al. Crystal structure of the cytochrome bc1 complex from bovine heart mitochondria. Science. 1997;277:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson A.T. Atovaquone - a novel broad-spectrum anti-infective drug. Parasitol. Today. 1993;9:66–68. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90040-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan D.B., Kranis K.T., Picollelli M.A., Schwartz R.S., Sternberg J.A., Sun K.M. Famoxadone and oxazolidinones: potent inhibitors of cytochrome bc1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1999;27:577–580. doi: 10.1042/bst0270577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan D.B., Livingston R.S., Bisaha J.J., Duncan K.E., Pember S.O., Picollelli M.A., et al. Mode of action of famoxadone. Pestic. Sci. 1999;55:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao X., Wen X., Yu C., Esser L., Tsao S., Quinn B., et al. The crystal structure of mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 in complex with famoxadone: the role of aromatic-aromatic interaction in inhibition. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11692–11702. doi: 10.1021/bi026252p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gisi U., Sierotzki H., Cook A., McCaffery A. Mechanisms influencing the evolution of resistance to Qo inhibitor fungicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002;58:859–867. doi: 10.1002/ps.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korsinczky M., Chen N., Kotecka B., Saul A., Rieckmann K., Cheng Q. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome b that are associated with atovaquone resistance are located at a putative drug-binding site. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2100–2108. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2100-2108.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephen J.M., Tonkin I.M., Walker J. Tetrahydroacridones and related compounds as antimalarials. J. Chem. Soc. 1947:1034–1039. doi: 10.1039/jr9470001034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amporndanai K., Johnson R.M., O'Neill P.M., Fishwick C.W.G., Jamson A.H., Rawson S., et al. X-ray and cryo-EM structures of inhibitor-bound cytochrome bc1 complexes for structure-based drug discovery. IUCrJ. 2018;5:200–210. doi: 10.1107/S2052252518001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amporndanai K., Pinthong N., O'Neill P.M., Hong W.D., Amewu R.K., Pidathala C., et al. Targeting the ubiquinol-reduction (Qi) site of the mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex for the development of next generation quinolone antimalarials. Biology (Basel) 2022;11:1109. doi: 10.3390/biology11081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.David Hong W., Leung S.C., Amporndanai K., Davies J., Priestley R.S., Nixon G.L., et al. Potent antimalarial 2-pyrazolyl quinolone bc 1 (Qi) inhibitors with improved drug-like properties. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:1205–1210. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McPhillie M.J., Zhou Y., Hickman M.R., Gordon J.A., Weber C.R., Li Q., et al. Potent tetrahydroquinolone eliminates apicomplexan parasites. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:203. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stickles A.M., de Almeida M.J., Morrisey J.M., Sheridan K.A., Forquer I.P., Nilsen A., et al. Subtle changes in endochin-like quinolone structure alter the site of inhibition within the cytochrome bc1 complex of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1977–1982. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04149-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu C.A., Yu L. Syntheses of biologically active ubiquinone derivatives. Biochemistry. 1982;21:4096–4101. doi: 10.1021/bi00260a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu L., Yang S., Yin Y., Cen X., Zhou F., Xia D., et al. Chapter 25 Analysis of electron transfer and superoxide generation in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Met. Enzymol. 2009;456:459–473. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04425-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao Y.M., Esser L., Zhou F., Li C., Zhou Y.H., Yu C.A., et al. Studies on inhibition of respiratory cytochrome bc1 complex by the fungicide pyrimorph suggest a novel inhibitory mechanism. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant T., Rohou A., Grigorieff N. cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.35383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., et al. Phenix: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., et al. Phenix: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawson C.L., Patwardhan A., Baker M.L., Hryc C., Garcia E.S., Hudson B.P., et al. EMDataBank unified data resource for 3DEM. Nucl. Acids Res. 2016;44:D396–D403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., et al. The protein Data Bank. Nucl. Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraulis P.J. Molscript - a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esnouf R.M. Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1999;55:938–940. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998017363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data processing and statistics for the structure determination of Btbc1 in complex with CK-2-68 by cryo-EM. (a) A panel of selected representative 2D classes. (b) Workflow for the EM data processing and local resolution map of dimeric Btbc1/CK-2-68 structure contoured at 4σ level. (c) A local resolution map. The color code is given by the side strip. (d) Gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves of the final density map. The reported resolution for this structure was based on the FSC=0.143 criterion.

A representative view of the electron density map of Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex. Cryo-EM density at 2.88 Å resolution (blue) was contoured at 5σ level, containing refined stick models of cyt b (light gray), the inhibitor (brown) and the ISP (yellow) with its fixed extrinsic domain. The ISP-ED is seen in the fixed b-position as it interacts with CK-2-68 at the QP site.

Detailed comparisons of CK-2-68 binding sites: QN vs QP. (a) Depiction of the binding of CK-2-68 to the QN site in 6ZFT. The electron density calculated from a deposited X-ray diffraction data set 6zft_2fofc.dsn6 downloaded from the PDB databank was contoured at two levels: 1σ (blue) and 3σ (white). At the 1σ contour level, the rings A and B are covered by density, but the tail of the modeled CK-2-68 is not covered. At the higher contour level of 3σ, ring A has lost substantial portions of density whereas surrounding residues are still well covered. While the conformations of H201 and D228 would favour the presence of a QN occupant, it is more likely that residual and/or disordered ubiquinone was mistaken for CK-2-68. (b) The cryo-EM density for 7TZ6 (this work) showed in the same pocket as in (a) no sign of a bound inhibitor. The presence of spurious density is typical for this region when it is unoccupied. (c) The view of the QP site in 6ZFT showed no density for an inhibitor. The presence of additional density in the hydrophobic active site was modeled with a hydrophilic PEG-4 (polyethylene glycol fragments). The ISP is close to cyt c1 and therefore absent from the QP site. (d) The QP site of 7TZ6 (this work) shows clear density for CK-2-68, surrounding residues, and for the fixed ISP head domain (green).

Binding environment of two types of Complex III inhibitors targeting the QP site. The QP pocket is drawn as stereographic illustration. (a) The binding environment for stigmatellin is shown in the same orientation as seen in Fig. 5a. This structure was determined by X-ray crystallography for Btbc1/stigmatellin complex (PDB:1SQX)(20). The bound stigmatellin is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, and oxygen in red. The highly conserved residue E271 (side chain carbon atoms are cyan for emphasis) is in the “in-conformation”. The carboxylate group is forming a hydrogen bond (dotted lines) with stigmatellin (atom O8). (b) The binding environment of atovaquone is in the same orientation as seen above. This structure was determined for Scbc1/atovaquone complex by X-ray crystallography (PDB:4PD4)(15). Here the inhibitor atovaquone was rendered as stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, and oxygen in red and chlorine atom in green. The glutamic acid residue E272 (Sc numbering equiv. BTE271) is in the “out-conformation” despite the presence of atom O1 of atovaquone. However, atom O1 may still be too far away to engage the glutamate residue.

Superposition of the structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 with the model of Pfbc1 generated with AlphaFold 2. Two orthogonal views of the superposition are given. The structure of Btbc1/CK-2-68 complex determined by cryo-EM is shown as a cartoon model in magenta. The hemes bL and bH are rendered as stick models with carbon atoms colored red, oxygen red and nitrogen blue. The bound CK-2-68 is also rendered as stick model with carbon in brown, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue and chlorine in green. The model structure of Pfbc1 in cartoon model is color green.

Potential changes to the QP site affecting binding of CK-2-68. The bound CK-2-68 is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms in light brown, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue, chlorine in deep green and fluorine in light green. The QP site is depicted as CA traces with the cd1 helix (142-149) shown in blue, part of the Helix C (124-129) in green, and the ef loop (268-279) in gray. Side chains of important residues are shown as stick models and labeled. The highly conserved residue E271 is in the “out-conformation”. The A127T (A122T in Pfbc1) mutation is shown, which is not in direct contact with bound CK-2-68 but participates as part of the binding environment. Arrows in magenta are drawn to indicate potential interactions that might bring changes to the inhibitor binding environment.

The narrow opening of the QP pocket with bound CK-2-68. The Van der Waals surface of the QP pocket is overlaid with residues, shown in stick models, forming the narrow path for the quinolone moiety of the inhibitor CK-2-68, also shown as stick model. The narrowest part of the path is formed by residue P270 on one side and the G142 on the other side. The G142A is a common mutation identified in many pathogenic fungi. The Cβ atom of A142 is drawn as a cyan (transparent) van der Waals sphere and equivalently the chlorine atom of CK-2-68 is shown as a green sphere. The severe clashes are shown in red hashes suggesting that a hypothetical G137APF mutant would resist CK-2-68.

Superposition of cyt b subunits of CK-2-68 and atovaquone bound Complex III. Superposed cyt b subunits between Btbc1/CK-2-68 (PDB:7TZ6, this work) and Scbc1/atovaquone (PDB:4PD4) are shown as cartoon in green. The superposition brings CK-2-68 and atovaquone to overlap. Inhibitors are rendered as stick models with CK-2-68 in black and atovaquone in cyan. Oxygen atoms are colored in red and nitrogen atoms in blue. The ISP subunit is colored yellow with the 2Fe2S cluster, H161, and C160 shown as stick models and labeled. Y278 and its serine mutation are also shown as stick models. R282 (K272 for Pfbc1) that is shielded by Y278 becomes exposed to the bound inhibitors in the Y278S mutant.

Shapes of Inhibitors in comparison. Famoxadone (top) is a typical QP site inhibitor and so is CK-2-68 (Fig. 2a) owing to a very similar topology. Surprisingly, CK-2-67 (middle), which is lacking a chlorine atom in position 7, is a QN site inhibitor. It is speculated that it has the potential to bind to the QP site still, but its isomeric form WDH-1U-4 (bottom) is prevented from binding in the QP site due to a bulky group in position 3 (35).

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and an EM map have been deposited with EMD (45) with the ID code EMD-26203 and with the RCSB Protein Data Bank (46) with the PDB ID code of 7TZ6, for the Btbc1/CK-2-68 structure.