Abstract

Conventional and regulatory T cells (Treg) are dynamic mediators of maternal immune tolerance to the developing fetoplacental unit. Functional evaluation of T cells at the maternal-fetal interface is crucial to elucidate the immunologic basis of obstetric complications. Our objective was to define the T cell phenotype and function of uterine intervillous blood (IVB) in pregnancy with and without preeclampsia. We hypothesize that preeclampsia is associated with impaired immune tolerance and a pro-inflammatory uterine T cell microenvironment. In this cross-sectional study, maternal peripheral blood (PB) and uterine IVB (obtained from the surgical sponge used to clean the placental bed during cesarean delivery) were collected from participants with and without preeclampsia. Proportion, activation, and cytokine production of T cell subsets were quantified by flow cytometry. T cell parameters were compared by tissue source and by preeclampsia status. Sixty participants, 26 with preeclampsia, were included. Induced Treg made up a greater proportion of IVB T cells compared to PB and had greater cytokine-producing capacity. Preeclampsia was associated with increased ratio of pro-inflammatory IL-17α to suppressive IL-10 cytokine production by CD4 T cell subsets in IVB, but not in PB. Human uterine IVB is composed of activated, cytokine-producing T cell subsets distinct from maternal PB. Preeclampsia is associated with a pro-inflammatory IVB profile, with increased IL-17α /IL-10 ratio in all CD4 T cell subsets. IVB sampling is a useful tool for investigating human T cell biology at the maternal-fetal interface that may inform immunotherapeutic strategies for preeclampsia.

Keywords: Maternal-fetal interface, Preeclampsia, Regulatory T cells, IL-17

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a common, multi-organ disease of late pregnancy and is the leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in the USA [1, 2]. Treatment options are limited primarily to delivery, often resulting in prematurity and related consequences. Dysregulated angiogenesis and immune dysregulation both have been hypothesized to contribute to the pathogenesis [3, 4]. Prior studies suggest an immune-mediated component to preeclampsia pathogenesis [5]. While healthy pregnancy development depends on minimizing maternal immune responses to the “foreign” placenta and fetus, which is genetically and antigenically different from the mother, healthy placentation also requires active tolerance by immune cells at the maternal-fetal interface. Regulatory T cells (Treg) are specialized immunosuppressive CD4 T helper cells that mediate immune tolerance in transplantation, tumors, and autoimmune disease [6, 7]. Treg are numerically increased in maternal peripheral blood and gain additional suppressive functionality as pregnancy progresses [8, 9]. Treg are important mediators of maternal tolerance in pregnancy through inhibition of harmful anti-fetal effector T cell (Teff) responses.

Two subsets of Treg exist: (1) natural Treg (nTreg), which develop centrally in the thymus and express high levels of transcription factor FoxP3, and (2) induced Treg (iTreg), which are induced in peripheral tissues in response to peripheral tissue antigens and express high levels of PD-1 and low FoxP3 [7, 10]. iTreg, also identified in the literature as type 1 regulatory cells, are suppressive CD4 T cells that express IL-10 and TGF-β and do not constitutively express FoxP3, the transcription factor traditionally believed to identify suppressive T cells [10, 11]. Very little is understood about the mechanism of iTreg, aside from IL-10 gene activation, and, interestingly, they have some transcriptional overlap with pro-inflammatory Th17 and Th1 T cell lineages [10]. Recently, both Treg subsets have been isolated from first-trimester termination samples and enzymatically digested, term placentas [12]. Specimens collected from early trimester non-continuing pregnancies provide a convenient source of discarded tissue [11, 12]; however, this method precludes the ability to correlate immunologic findings in early pregnancy with late obstetric outcomes such as preeclampsia. Diminished maternal Treg composition in the decidua has been reported in preeclampsia using immunohistochemistry of uterine placental site biopsies at cesarean delivery, but this sampling is rather invasive [13, 14]. An alternative method for sampling decidua leukocytes is enzymatic digestion of the placenta, but that technique can result in a variable number of viable cells and loss of cell surface marker integrity [15–18].

We utilized a non-invasive method of collecting the maternal uterine intervillous blood from a surgical sponge used routinely to clean the uterine cavity after placental delivery in cesarean delivery to investigate T cell activity in preeclampsia. The objective of our study was to illustrate how a non-invasive and efficient method of sampling the human uterine intervillous blood (IVB) described previously [19, 20] allows for identification of immune cells that interface directly with the placenta with unique characteristics from systemic peripheral blood (PB). The secondary objective was to compare the Treg and Teff profile of the maternal-fetal interface in preeclampsia to healthy pregnancy.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study of participants who were at least 18 years old, undergoing cesarean delivery for live born infant(s) without diagnosis of chorioamnionitis, and able to provide written informed consent. This protocol was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board (protocol #2016P000360). The cases were participants with preeclampsia (including preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension or preeclampsia with severe features) and the controls were participants with pregnancies without a diagnosis of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia was defined by new onset of hypertension >140/90 over greater than 4 h and proteinuria >300 mg in 24 h or worsening hypertension and proteinuria superimposed on chronic hypertension in accordance with ACOG guidelines [21]. At the time of delivery, maternal PB was collected in EDTA-coated tubes after standard venipuncture technique, typically at the time of clinical blood draw or intravenous line start. Infant cord blood was collected from the umbilical cord after delivery of the infant, but prior to placental separation in sterile-packed EDTA-coated tubes. As part of standard protocol during cesarean delivery, a surgical sponge is used to clean out the uterine cavity after separation and removal of the placenta. This uterine surgical sponge was rinsed in 100 mL sterile PBS and the diluted IVB from the sponge collected in 50 mL conical tubes.

Mononuclear Cell Isolation

The three samples obtained at delivery: uterine IVB, maternal PB, and infant cord blood were centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min. The supernatant or plasma was aspirated and the pellet was resuspended in HBSS media (Mediatech) and mononuclear cells were isolated by gradient centrifugation over Ficoll Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare). The mononuclear cells were washed with HBSS and viable cell count and frozen in 10% DMSO (Fisher Scientific) in FBS (Sigma) at 107 cells/mL and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining and Flow Cytometry

Frozen leukocytes were thawed and rested overnight in media. 106 viable mononuclear cells from IVB and PB were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with media, 10 pg/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), and 1 μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were then supplemented with monensin (GolgiStop; BD Biosciences), brefeldin A (GolgiPlug; BD Biosciences) and then incubated at 37 °C for an additional 5 h. The cells were then stained with predetermined titers of monoclonal surface antibodies (Table S1) at RT in the dark for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with 2% FBS/DPBS buffer and incubated for 30 min with 1× FoxP3 permeablization buffer (eBiosciences) and then stained with predetermined titers of monoclonal antibodies with intracellular targets for 30 min. Cells were washed with 1× Perm Wash buffer (BD Biosciences) and stained intracellularly with monoclonal antibodies (Table S1) for 30 min. Cells were fixed with 250 μL freshly prepared 1.5% formaldehyde. Fixed cells were analyzed by BD FACSymphony TM system.

Statistical Analysis

We collected and stored data using REDCap [22], a HIPAA compliant, secure, web-based data collection tool. Analysis and display of immunologic data was performed using GraphPad Prism v9.4.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). Tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Descriptive data is presented as proportion, or median (interquartile range). Comparisons were made using non-parametric tests for continuous variables, based on data distribution. The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center institutional review board approved this study (protocol #2016P-000360).

Results

Enrollment

Sixty participants, including 26 with the exposure of preeclampsia and 34 unexposed controls, were enrolled and analyzed from February 2017 to August 2019. Self-reported race and ethnicity were collected as well as medical and obstetric data from the electronic medical record. Baseline demographics of the participants, along with obstetric and neonatal characteristics, are presented in Table 1. Samples from all participants were analyzed using flow cytometry, and a subset (11 preeclampsia and 13 control) of participants had sufficient cells cryopreserved to have additional intracellular cytokine profiling (Table S2). As anticipated based on known risk factors for preeclampsia, participants in the preeclampsia group were more likely to be nulliparous, had a higher median body mass index and earlier median gestational age at delivery, and had a higher prevalence of chronic hypertension and pre-gestational diabetes.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics for T cell phenotyping

| Preeclampsia n = 26 | Control n = 34 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Maternal age (year; median [range]) | 34 [27, 40] | 36 [25, 43] |

| Self-reported race | ||

| White | 14 (54) | 18 (53) |

| Black | 3 (12) | 2 (6) |

| Asian | 0 | 6 (18) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 8 (31) | 7 (21) |

| Self-reported ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0 | 3 (9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 25 (96) | 30 (88) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Medical characteristics | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) at delivery | 33 [30, 41] | 29 [26, 33] |

| In vitro fertilization | 8 (31) | 13 (38) |

| Chronic hypertension | 7 (27) | 2 (6) |

| Pre-gestational diabetes | 8 (31) | 3 (9) |

| Autoimmune disease | 4 (15) | 3 (9) |

| Obstetric characteristics | ||

| Nulliparous | 17 (65) | 13 (38) |

| Fetal growth restriction | 4 (15) | 4 (18) |

| Severe features of preeclampsia | 16 (62) | 0 |

| Multifetal gestation | 8 (31) | 8 (24) |

| Gestational age at delivery (week) | 36 [34, 38] | 38 [37, 39] |

| Labor preceding cesarean | 9 (35) | 5 (15) |

| Female infant sex* | 13 (37) | 25 (58) |

Reported as median [interquartile range] or n (percent) unless otherwise specified

Due to multifetal gestation, percent (n) of female infants is not equal to the column total N

Identification of Intervillous Blood T Cell Subsets Using Intracellular Flow Cytometry

We first sought to define T cell profiles from IVB specimens using similar intracellular and surface markers to those used in prior studies evaluating iTreg and nTreg populations [11, 12, 23, 24]. Using our multi-parameter flow cytometry panel, we identified 4 live CD3+ T cell populations from human IVB: (1) FoxP3+ and Helios+ nTreg; (2) PD-1 high FoxP3− iTreg; (3) conventional CD4 T cells (Tconv) defined as CD4 T cells without PD-1 or FoxP3 expression; and (4) CD8+ effector T cells (Fig. 1). These four T cell subsets exhibited different proportions of CD45RO memory, activation marker CD69, co-inhibitory marker CTLA-4, and exhaustion marker TIM-4. Upon stimulation with T cell mitogens PMA and ionomycin, each T cell subset demonstrated a unique profile of immune suppressive IL-10, and immune stimulatory IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17α cytokine production. Although maternal PB and infant cord blood contamination with this IVB sampling cannot completely be excluded, we collected maternal and cord blood simultaneously for direct comparison of the uterine IVB sample. The high proportion of CD45RO (memory phenotype) and PD-1 display in IVB was very distinct from the high proportion of CD45RA (naïve phenotype) and low PD-1 display in infant cord blood and the moderate proportion of CD45RO and low PD-1 display in maternal PB (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Identification and characterization of four T lymphocytes populations in human uterine intervillous blood. A Singlet, size, and viable cell gating for flow cytometry of human uterine intervillous blood (IVB) T cells. B Gating strategy for identification of C D3+ T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and induced regulatory T cells (iTreg), natural regulatory T cells (nTreg), and conventional effector CD4 T cells (CD4+ Tconv) using PD-1 and FoxP3 staining. Dot plots demonstrating relative proportion of CD45RO+ CD45RA− memory phenotype T cells, intracellular H elios+, surface CD25, CD69, CTLA-4, TIM-3, and stimulated intracellular cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-17α, and IL-10 production by nTreg (C), iTreg (D), CD4+ Tconv (E), and CD8+ T cells (F). Dot plots from a representative IVB sample

Proportion and Phenotype of Intervillous Blood T Cell Subsets Compared to Peripheral Blood

We compared the relative proportion of nTreg, iTreg, Tconv, and CD8 cells in the unstimulated IVB and PB samples obtained at delivery. nTreg and Tconv in IVB were present in similar proportions and exhibited similar CD45RO memory phenotype in IVB and PB (Fig. 2A, C). The proportion of iTreg in IVB was higher than the proportion of iTreg in systemic circulating PB (p = 0.0001, Fig. 2B). All 4 T cell subsets displayed significantly greater display of activation marker CD69 in the IVB (all p < 0.05). nTreg in the IVB displayed lower baseline proliferation (Ki67) than in PB (p = 0.006).

Fig. 2.

Proportion and phenotype of intervillous blood T cells compared to peripheral blood T cells. Proportion of CD3+ T cells, CD45RO+ CD45RA− memory phenotype, C D69+ activated phenotype, and proliferation by intracellular Ki67+ among A FoxP3-expressing natural regulatory T cells (nTreg); B PD-1hi-expressing induced regulatory T cells (iTreg); C FoxP3− PD-1lo conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconv); and D CD8+ T cells in IVB compared to peripheral blood (PB). Data is from unstimulated T cells. Median displayed with red bar. p value from Wilcoxon signed-rank paired test

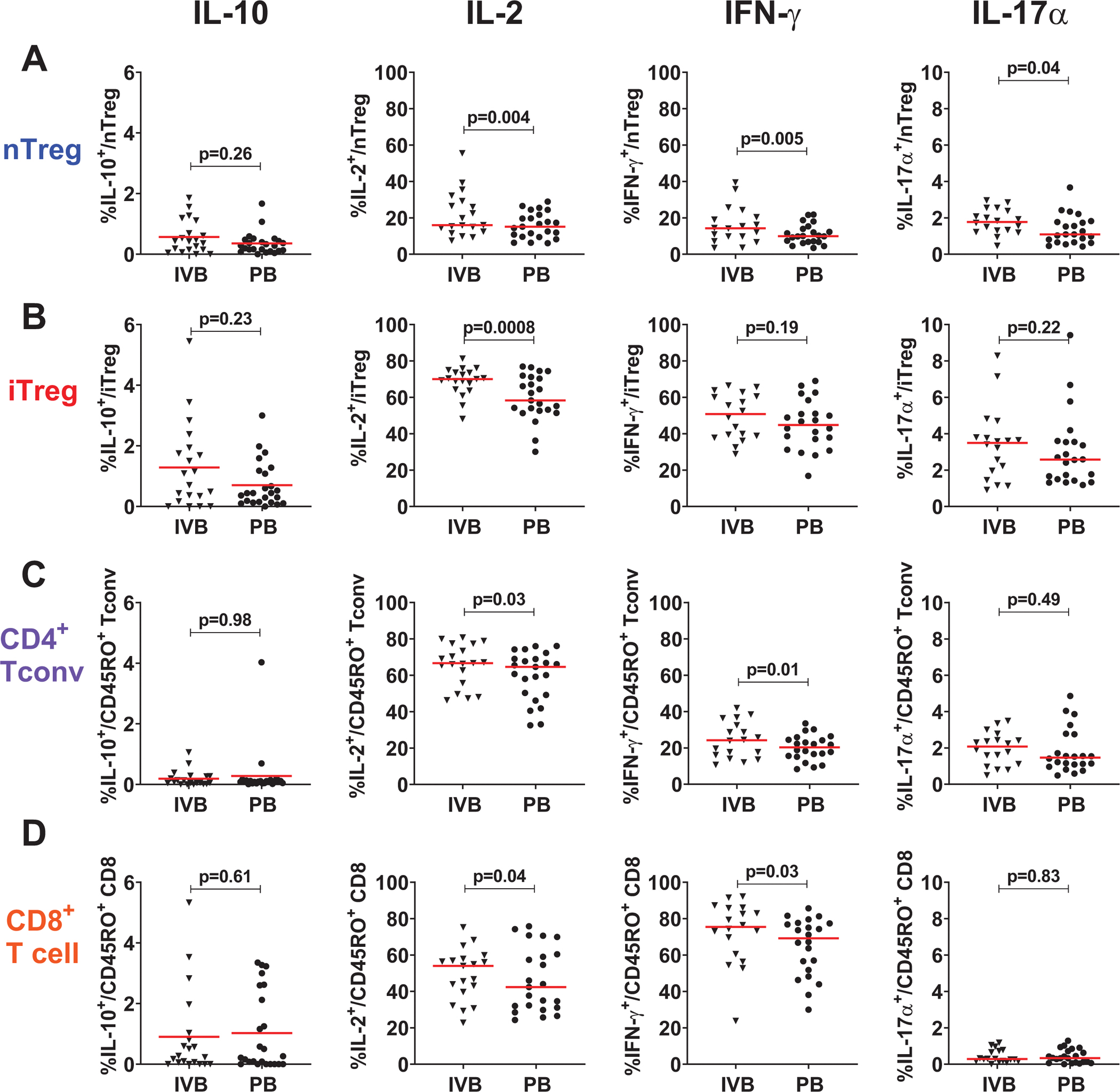

Suppressive and Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Production

We cultured the thawed mononuclear cells from IVB and PB in the presence of PMA and ionomycin to measure cytokine production after antigen-independent T cell stimulation. This method has been used to identify excessive and insufficient cytokine responses that can contribute to physiologic and pathologic responses in a range of diseases [25]. All T cell subsets displayed significantly higher IL-2 responses in IVB compared to PB (Fig. 3). iTreg from IVB secreted more suppressive IL-10 (median 0.90%; interquartile range (IQR) 0.21–1.9) compared to PB (0.44, IQR: 0.14–1.2), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.23). nTreg, Tconv, and CD8 T cells from IVB all secreted more IL-2 and IFN-γ compared to PB. IL-17α responses were greater in IVB than PB in the nTreg subset (p = 0.04) but similar in all other T cell subsets. Overall, IVB T cells exhibit a greater capacity for cytokine production compared to PB.

Fig. 3.

Cytokine production by intervillous blood T cell subsets compared to peripheral blood. Log proportion of cells producing suppressive cytokine IL-10, proportion of cells IL-2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17α, and in A FoxP3-expressing natural regulatory T cells (nTreg); B PD-1hi-expressing induced regulatory T cells (iTreg); C FoxP3− PD-1lo conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconv); and D CD8+ T cells in IVB compared to peripheral blood (PB). Data is from T cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. Mean (red bar) and p value from paired t test displayed for log-transformed IL-10 values. Other cytokines have median (red bar) and p value from Wilcoxon signed-rank paired test displayed for IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17α

Proportion and Phenotype of Intervillous Blood T Cells in Preeclampsia

Given that we observed a unique T cell phenotype in the uterine IVB T cells compared to PB, we then evaluated whether preeclampsia was associated with reduced T cell proportions or activation. The proportion of T cell subsets, the %CD45RO memory phenotype, %CD69, and %proliferation status by Ki67 was no different between PE and controls in either IVB or PB, aside from a modest increase in median %CD45RO+ nTreg in IVB for preeclampsia (p = 0.04, Fig. S2).

Suppressive and Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Production in Preeclampsia

We next evaluated the function of IVB T cells in preeclampsia by evaluating cytokine production following stimulation in culture with PMA and ionomycin. Here we noted a reduction, albeit not statistically significant, in median IL-10 production in all T cells compared to controls in the IVB only and not PB (Fig. 4). Preeclampsia was associated with a greater median IL-17α production than controls in IVB for nTreg (preeclampsia: 2.0% (1.7–2.9); control: 1.4% (1.2–2.0)), iTreg (preeclampsia 3.6% (2.6–4.8); control: 1.7 (1.1–3.5)), and Tconv (preeclampsia: 2.4% (1.8–2.4); control: 1.4 (0.84–2.5); Fig. 4A,B,C), though this was not statistically significant. No other significant alteration in IL-2 or IFN-γ production was observed in preeclampsia. We further evaluated the Th17/Treg bias by computing the ratio of %IL-17α to %IL-10 proportion in T cell subsets and found that preeclampsia was associated with a significantly elevated IL-17α/IL-10 ratio in all CD4 T cell subsets in the IVB (all p ≤ 0.02, Fig. 5). This was despite a lower ratio in PB nTreg (p = 0.046).

Fig. 4.

Production of suppressive and pro-inflammatory cytokines in preeclampsia by intervillous blood and peripheral blood T cell subsets. Log proportion of cells producing suppressive cytokine IL-10, proportion of cells IL-2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17α, and in A FoxP3-expressing natural regulatory T cells (nTreg); B PD-1hi-expressing induced regulatory T cells (iTreg); C FoxP3− PD-1lo conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconv); and D CD8+ T cells. Participants with preeclampsia (PE) shown in blue compared to control (ctl) in black in IVB (triangles) compared to peripheral blood (PB, circles). Data is from T cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. Median (red bar) and p value from Wilcoxon test displayed for each cytokine

Fig. 5.

Ratio of pro-inflammatory IL-17α and suppressive IL-10 cytokine production by T cell subsets in preeclampsia. Ratio of IL-17α to IL-10 staining in FoxP3-expressing natural regulatory T cells (nTreg); PD-1hi-expressing induced regulatory T cells (iTreg); FoxP3− PD-1lo CD45RO+ conventional memory CD4+ T cells (Tconv); and CD45RO+ memory CD8+ T cells. Participants with preeclampsia (PE) shown in blue compared to control (ctl) in black in IVB (triangles) compared to peripheral blood (PB, circles). Data is from T cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. Median displayed with red bar

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that T cells homing to the human maternal-fetal interface are uniquely enriched in iTreg cells with activated memory phenotype and have enhanced capacity to express both pro-inflammatory and inhibitory cytokines. Using this method of isolating uterine T cells from the uterine surgical sponge as previously reported [19, 20], we characterized two distinct regulatory T cell subtypes (nTreg and iTreg) that exhibit similar phenotype and cytokine production to that has been described in first-trimester and term uterine blood sampling [12]. The IVB samples in pregnancy are significantly enriched for both CD45RO (memory phenotype), PD-1 (Fig. S1), and CD69 (a T cell activation marker; Fig. 2). Interestingly, CD69 also is a marker of tissue resident memory cells [26–28], which are non-circulating T cells typically located in mucosal tissues. Greater CD69 expression on IVB T cells suggests this sample is enriched for tissue resident memory. The fact that a tissue resident memory phenotype is present in our uterine T cell sampling method further validates the method as a reliable means of non-invasive sampling of T cells populating the maternal-fetal interface without the need for invasive uterine tissue biopsy or placental dissociation.

Other groups have reported reduced circulating nTreg and reduced decidua nTreg in association with preeclampsia [8, 14]. We did not observe a difference in %nTreg for either the uterine or systemic compartments in preeclampsia, despite having comparable sample size and power in our study. This may be attributed to a difference in technique for collecting and enumerating nTreg—immunohistochemical staining of decidua bed biopsy compared to flow cytometry surgical sponge IVB elution. Treg are heterogeneous and dynamic and can switch to Th17 phenotype, making their exact quantification difficult to compare across studies [9]. Despite the proportions of iTreg and nTreg in the IVB of preeclampsia and controls being similar, we observed an increase, albeit not statistically significant, in the production of pro-inflammatory IL-17α by IVB iTreg and nTreg in preeclampsia. These findings are complementary to prior studies demonstrating that IL-17α elevation was a key mediator of preeclampsia symptoms in an animal model [29]. Given our finding of significantly increased ratio of IL-17α/IL-10 in IVB, our study provides justification for future “bedside to bench” reverse translation efforts to engineer animal models [30, 31] targeting the IL-17α/IL-10 pathway to mimic immune-mediated preeclampsia. This data highlights the importance of a Th17/Treg (IL-17α/IL-10) bias at the maternal-fetal interface in association with PE, rather than Th1/Th2 (IFN-γ/IL-4) imbalance.

Strengths of this study include our method of sampling uterine IVB, which allows for study of human pregnancy T cell activity at the site of immunologic importance without invasive biopsy or loss of T cell integrity from prolonged tissue disruption processes. In addition, the use of high-definition multi-parameter flow cytometry for phenotypic profiling of multiple T cell subtypes coupled with functional cytokine secretion assays adds to existing literature in human pregnancy, which has been mostly limited to enumeration of nTreg cells without exploring other cell subsets or function. This protocol for T cell isolation is compatible with scRNAseq platforms that may allow correlation of cytokine dysfunction seen in our study with impaired Treg clonal expansion of T cells in preeclampsia described by Tsuda et al. [32, 33].

A limitation of this study is the single time point of sampling with both the outcome (preeclampsia) and exposure (immune cell dysfunction) measured concurrently, which precludes assessment of causality. Future studies will need to explore earlier decidua samples from ongoing pregnancies (potentially from first-trimester chorionic villus sampling) or preconception uterine environment and the association with later obstetric complications. Again, reverse translation to create an animal model to evaluate the causal pathway may be a good approach. Because we are not mechanically or enzymatically digesting the decidua tissue to obtain the T cell samples, we have named this uterine sponge sample maternal intervillous blood, though others may consider this method more representative of uterine decidua T cells.

Our exposed and unexposed groups are heterogeneous with varying severity of preeclampsia, introducing potential confounding by obstetric characteristics such as labor, prematurity, multiparity, baseline autoimmune disease, and multifetal gestation. However, this lack of restriction to broaden the generalizability of our findings. In future studies, selection of participants that fall into the “immunologic” mediated cluster of preeclampsia [34, 35] with associated fetal growth restriction, placental histology, and placental transcriptional profile could be utilized to obtain a more homogenous group with preeclampsia. Despite the heterogeneity and potential dilution of the effect by less immune-mediated phenotypes of preeclampsia, we observed significant altered IVB T cell proportion.

In conclusion, T cells have a more activated memory phenotype in the local uterine environment than in the periphery and have greater cytokine-producing capacity. An imbalance in pro-inflammatory and suppressive cytokine production by IVB T cells is associated with preeclampsia and supports an immune-mediated pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Future work should focus on defining the functional and transcriptional regulation of T cells (including tissue resident memory) and the T cell antigen specificity present at the human maternal-fetal interface in both healthy pregnancy and preeclampsia. This method of sampling and studying IVB lymphocytes has wide application and will be a useful tool to investigate other immunologically mediated obstetric complications such as fetal growth restriction, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and idiopathic preterm birth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the participants. We would like to thank members of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, especially Labor and Delivery staff, for assistance with specimen collection. The authors thank Barouch Lab members and Victor Cox for assistance with human specimen processing and Jinyan Liu and CVVR Flow Cytometry Core director Michelle Lifton for assistance with developing and optimizing the flow cytometry panel.

Funding

We acknowledge NIH grants (AI124377, AI128751), the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard.

A.Y.C. received support from the grant K12HD000849, awarded to the Reproductive Scientist Development Program by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

M.R.H. received support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL 1TR002541) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University, and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Code Availability N/A.

Declarations

Ethics Approval This study was conducted with approval of the BIDMC Institutional Review Board protocol #2016P000360.

Consent to Participate All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication Written informed consent included the consent to publish de-identified information resulting from the study and medical record for research purposes.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-023-01165-4.

Availability of Data and Material

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary material. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.Y.C. (acollier@bidmc.harvard.edu).

References

- 1.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):366–73. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maric-Bilkan C, Abrahams VM, Arteaga SS, et al. Research recommendations from the National Institutes of Health Workshop on predicting, preventing, and treating preeclampsia. Hypertens Dallas Tex. 2019;73(4):757–66. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia: pathophysiology, challenges, and perspectives. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1094–112. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim MY, Buyon JP, Guerra MM, et al. Angiogenic factor imbalance early in pregnancy predicts adverse outcomes in patients with lupus and antiphospholipid antibodies: results of the PROMISSE study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):108.e1–108.e14. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito S, Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Nakashima A, Shiozaki A. Inadequate tolerance induction may induce pre-eclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2007;76(1–2):30–9. 10.1016/j.jri.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30(6):899–911. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himmel ME, MacDonald KG, Garcia RV, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Helios+ and Helios- cells coexist within the natural FOXP3+ T regulatory cell subset in humans. J Immunol Baltim Md. 2013;190(5):2001–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112(1):38–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redman CWG, Sargent IL. Immunology of pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N. 2010;63(6):534–43. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Bacchetta R, Battaglia M, Gagliani N. The biology of T regulatory type 1 cells and their therapeutic application in immune-mediated diseases. Immunity. 2018;49(6):1004–19. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagliani N, Magnani CF, Huber S, et al. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nat Med. 2013;19(6):739–46. 10.1038/nm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvany-Celades M, van der Zwan A, Benner M, et al. Three types of functional regulatory T cells control T cell responses at the human maternal-fetal interface. Cell Rep. 2019;27(9):2537–2547. e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito S, Shiozaki A, Nakashima A, Sakai M, Sasaki Y. The role of the immune system in preeclampsia. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28(2):192–209. 10.1016/j.mam.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki Y, Darmochwal-Kolarz D, Suzuki D, et al. Proportion of peripheral blood and decidual CD4(+) CD25(bright) regulatory T cells in pre-eclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149(1):139–45. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krop J, van der Zwan A, Ijsselsteijn ME, et al. Imaging mass cytometry reveals the prominent role of myeloid cells at the maternal-fetal interface. iScience. 2022;25(7):104648. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raffetseder J, Lindau R, van der Veen S, Berg G, Larsson M, Ernerudh J. MAIT cells balance the requirements for immune tolerance and anti-microbial defense during pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:718168. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.718168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vazquez J, Chavarria M, Li Y, Lopez GE, Stanic AK. Computational flow cytometry analysis reveals a unique immune signature of the human maternal-fetal interface. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;79(1). 10.1111/aji.12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Plazyo O, Romero R, Hassan SS, Gomez-Lopez N. Isolation of leukocytes from the human maternal-fetal interface. J Vis Exp. 2015;99:e52863. 10.3791/52863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TA, Kahn DA, Loewendorf AI. Maternal-fetal rejection reactions are unconstrained in preeclamptic women. PloS One. 2017;12(11):e0188250. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewendorf AI, Nguyen TA, Yesayan MN, Kahn DA. Normal human pregnancy results in maternal immune activation in the periphery and at the uteroplacental interface. PloS One. 2014;9(5):e96723. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Practice Bulletin No ACOG. 222: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;133(1):1. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhairavabhotla R, Kim YC, Glass DD, et al. Transcriptome profiling of human FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol. 2016;77(2):201–13. 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Chikina M, Dadey RE, et al. Interferon-γ drives Treg fragility to promote anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 2017;169(6):1130–1141.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ai W, Li H, Song N, Li L, Chen H. Optimal method to stimulate cytokine production and its use in immunotoxicity assessment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):3834–42. 10.3390/ijerph10093834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan X, Rudensky AY. Hallmarks of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Cell. 2016;164(6):1198–211. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller SN, Gebhardt T, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Memory T cell subsets, migration patterns, and tissue residence. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31(1):137–61. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masopust D, Soerens AG. Tissue-resident T cells and other resident leukocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:521–46. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scroggins SM, Santillan DA, Lund JM, et al. Elevated vasopressin in pregnant mice induces T-helper subset alterations consistent with human preeclampsia. Clin Sci Lond Engl. 2018;132(3):419–36. 10.1042/CS20171059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy FP, Kingdom JC, Kenny LC, Walsh SK. Animal models of preeclampsia; uses and limitations. Placenta. 2011;32(6):413–9. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffett A, Loke C. Immunology of placentation in eutherian mammals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(8):584–94. 10.1038/nri1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuda S, Zhang X, Hamana H, et al. Clonally expanded decidual effector regulatory T cells increase in late gestation of normal pregnancy, but not in preeclampsia, in humans. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1934. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuda S, Nakashima A, Shima T, Saito S. New paradigm in the role of regulatory T cells during pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:573. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leavey K, Benton SJ, Grynspan D, Kingdom JC, Bainbridge SA, Cox BJ. Unsupervised placental gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subclasses of human preeclampsia. Hypertens Dallas Tex. 2016;68(1):137–47. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leavey K, Grynspan D, Cox BJ. Both “canonical” and “immunological” preeclampsia subtypes demonstrate changes in placental immune cell composition. Placenta. 2019;83:53–6. 10.1016/j.placenta.2019.06.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary material. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.Y.C. (acollier@bidmc.harvard.edu).