Abstract

Insomnia disorder (chronic sleep continuity disturbance) is a debilitating condition affecting 5–10% of the adult population worldwide. To date, researchers have attempted to model insomnia in animals through breeding strategies that create pathologically short-sleeping individuals or with drugs and environmental contexts that directly impose sleeplessness. While these approaches have been invaluable for identifying insomnia susceptibility genes and mapping the neural networks that underpin sleep-wake regulation, they fail to capture concurrently several of the core clinical diagnostic features of insomnia disorder in humans, where sleep continuity disturbance is self-perpetuating, occurs despite adequate sleep opportunity, and is often not accompanied by significant changes in sleep duration or architecture. In the current review, we discuss these issues and then outline ways animal models can be used to develop approaches that are more ecologically valid in their recapitulation of chronic insomnia’s natural etiology and pathophysiology. Conditioning of self-generated sleep loss with these methods promises to create a better understanding of the neuroadaptations that maintain insomnia, including potentially within the infralimbic cortex, a substrate at the crossroads of threat habituation and sleep.

Introduction

Insomnia is a disturbance of sleep continuity (trouble falling or staying asleep) that occurs despite adequate sleep opportunity and is associated with sleep-related daytime impairments (Perlis et al., 2022). While transient episodes of insomnia are common (~ 30% incident rates per annum), 10–15% of individuals will experience sustained sleep continuity problems that merit classification as insomnia disorder (Morin et al., 2015). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) and International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3), chronic insomnia is defined as difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep that occur on 3 or more nights per week for at least 3 months (Riemann et al., 2017). Though quantitative severity criteria for insomnia disorder are lacking (i.e., thresholds for what constitutes abnormal sleep latencies, wake after sleep onset times, duration of early mornings awakenings, or total sleep times), illness severity is often quantified in terms of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and/or the degree of impairment experienced by the patient in their mood, cognition, and emotion regulation (Morin & Benca, 2012; Shekleton, Rogers, & Rajaratnam, 2010). Some experts argue that objective short sleep duration should also factor into the formal nosologies for insomnia given its utility to predict the severity of insomnia-related biological outcomes (e.g., cardiometabolic morbidity) (Vgontzas & Fernandez-Mendoza, 2013).

History of Animal Models

Preclusion of Sleep by Environmental and Drug-Induced Arousal

The medical, psychiatric, and societal costs of insomnia have long motivated attempts to model sleep continuity disturbance in laboratory animals in the hopes of uncovering more specific details with respect to the etiology and pathophysiology of insomnia and/or for the purposes of developing and testing new treatments for humans (Revel, Gottowik, Gatti, Wettstein, & Moreau, 2009; Toth & Bhargava, 2013). A key aspect of insomnia is the expression of dissatisfaction with sleep but no methods to date have devised ways that would enable animals to communicate this. Experimenters have interfered with the sleep continuity of rodents, the most prolific model, by directly manipulating the environment or the brain’s sleep-wake regulatory circuitry. In rats, decreases and fragmentation of non-REM or REM (rapid eye movement) sleep are achieved through the sudden introduction of environmental noise or continuous high intensity white-noise stimulation (Rabat et al., 2004; Velluti, 1997), reductions in ambient temperature below the thermoneutral zone (cold exposure from −10 to 10 °C for 24–48 hours) (Alfoldi, Rubicsek, Cserni, & Obal, 1990; Amici et al., 1994; Cerri et al., 2005), and by the perfusion of odors associated with food (Gervais & Pager, 1979), predators (Cattarelli & Chanel, 1979), or conspecifics (Cattarelli, Pager, & Chanel, 1977). Other approaches promote sleeplessness through pharmacological means using caffeine (Wang & Deboer, 2022; Yanik, Glaum, & Radulovacki, 1987), an adenosine receptor antagonist that blocks the accumulation of sleep pressure (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997), psychostimulants (e.g., cocaine or amphetamine) (Hill, Mendelson, & Bernstein, 1977; Okuma, Matsuoka, Matsue, & Toyomura, 1982), or a mix of drugs that enhance the activity of the dorsal and ventral branches of the reticular activating system (RAS) (Saper, Scammell, & Lu, 2005). Wake-promoting nuclei within the RAS offer a number of entry points by which to increase physiological and behavioral arousal, including the orexin-secreting cells of the lateral hypothalamus (Bourgin et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001) and noradrenaline-secreting cells of the locus coeruleus (Singh & Mallick, 1996). By virtue of its projections to the latero-dorsal and pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei, artificial activation of the locus coeruleus during sleep fragments REM generation (Tononi, Pompeiano, & Pompeiano, 1989).

Genetic Approaches to Sleeplessness in Animals

Externally applied perturbations, such as those described above, enable investigators to create sleeplessness in animals, usually in rodents. For the most part, these models are not representative of the factors that are thought to trigger or maintain sleep continuity disturbance in humans. What’s more, they introduce potential confounds. When interpreting the health effects of sleeplessness after pharmacologic stimulation, for example, one is unable to know whether the health effects resulting from poor sleep are due to the other (non-sleep related) biological actions of the drug-induced insomnia. Investigators have tried to overcome these limitations by using a Mendelian approach (breeding strategies) that select for lines of animals with different sleep abilities (Harbison, 2022). The approach assumes there are common genetic components to insomnia disorder related to sleep-stability factors that are heritable in both humans and animals. One of the most successful examples of this strategy can be found in the Shaw Drosophila Model, which is based on a normative dataset collected from wild-type Canton-S (Cs) flies (Figure 1). Starting from a larger, sleep-diverse population of diurnal flies, Shaw identified individuals that slept less, took longer to fall asleep, and were awake more intermittently during the typical sleep period at night (Andretic & Shaw, 2005). These flies were selectively bred over dozens of successive generations, forming a stable insomnia-like line referred to as ins-l. By the 65th generation, ins-l flies obtained less than 60 minutes of sleep per day (as opposed to several hours per day in wild-type flies) and, analogous to people with insomnia disorder, had significant difficulties maintaining sleep through longer uninterrupted bouts (Seugnet et al., 2009). They also exhibited the typical daytime consequences of insomnia. Relative to longer sleeping animals in the colony, ins-l flies performed poorly on such tasks as aversive phototaxic suppression and fell more when spontaneously walking through an obstacle-free environment, thus evincing signs of fatigue (Seugnet et al., 2009). The drawback for this model is that by selecting for a pathologically short sleeping animal and condensing it to a single line, one may be isolating genes operating in only one of many potential biological pathways for insomnia. It is likely that independent selections, starting fresh from other colony-wide screens, would yield alternative signaling pathways relevant to human insomnia. The other drawback is that, like with any breeding strategy, one may also be selecting for a number of unknown traits that have biological consequences outside of sleep. This said, a major advantage of the model is that, like human insomnia, the approach sets in place a mismatch between sleep ability and sleep opportunity that is thought to behaviorally maintain insomnia as a chronic condition. This perspective naturally lends itself to the question “what would happen if sleep opportunity was matched to ability with sleep restriction therapy?” This issue is addressed later in a discussion of the Belfer-Kayser Model.

Figure 1.

The Shaw Drosophila Model. The figure represents the lab selection process responsible for the creation of short-sleeping insomnia flies (ins-l) from a colony of Canton-S (Cs) females. Histograms represent sleep time across 60-min bins from 0 to 1360 min. Most females from the original colony met experimental criteria for sleep for 9 hours or more. After repeated rounds of selection for short-sleeping individuals, those in the ins-l line generally slept less than 5 hours, with many not sleeping more than 1 hour.

Prolonged Sleep Deprivation in Rats

Many investigators have attempted to model sleep continuity disturbance with long-term sleep deprivation techniques collectively referred to as the disc-over-water method (Rechtschaffen & Bergmann, 1995). Here, an animal, typically a rat, is housed on an unsteady platform raised above a shallow pool of water. Sleep loss is incurred whenever the rat enters REM, owing to the loss of muscle tone (van Luijtelaar & Coenen, 1986). Besides the obvious issue that the disc-over-water paradigm creates REM-specific sleep deficits (leaving NREM sleep relatively intact) (Mendelson, Guthrie, Frederick, & Wyatt, 1974), the method does not align with many cases of human insomnia where objective sleep duration and sleep architecture are unchanged from normative values (Buysse, 2013). The model also runs counter to a basic diagnostic criterion for human insomnia disorder: namely that difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep should occur despite adequate opportunity for sleep. The disc-over-water method thus is not an ideal analog of insomnia disorder as it occurs in humans. Additionally, this method imposes sleeplessness by forcing the animal to stay awake in an environment hostile to sleep when chronic insomnia is—by its very definition—self-generating and reinforcing. Given these particulars, the model may be more appropriate for modeling the acute insomnia that occurs in association with stress.

Animal Models of Insomnia: End-State Versus Pathway Modeling

Stepping back to look at the larger picture of how insomnia has been previously modeled in the lab, one realizes that many methods impose sleeplessness in animals who otherwise would sleep normally without the laboratory interventions. These animals do not experience insomnia in a genuine clinical sense (though this may be the case for animals selected on the basis of their short sleep and accompanying daytime dysfunction). This raises a key issue for future efforts looking to simulate the progression of human insomnia disorder in animals. Can we move beyond the superficial similarities of sleep loss, the end-state of insomnia, and develop models that are more ecologically valid in their recapitulation of insomnia’s natural etiology and pathophysiology (e.g., conditioned sleeplessness)? This possibility is discussed after first reviewing what is acknowledged to be the most veridical of the etiology pathways in humans.

The Etiology of Chronic Insomnia in Humans: Three-Factor (3P) Models

The Spielman or “3P” model describes how sleep continuity disturbance occurs acutely and then becomes chronic and self-perpetuating, leading to insomnia disorder (i.e., chronic insomnia) (Spielman, Caruso, & Glovinsky, 1987). The model involves three factors. The first two, predisposing and precipitating factors, represent a stress-diathesis conceptualization of how insomnia disorder develops. The third, so-called perpetuating factor, describes how behavioral factors transition and reinforce sleep continuity disturbance from its acute to chronic forms (Spielman, Caruso, et al., 1987).

Predisposing factors for insomnia can be biological, psychological, or social in nature (Harvey, Gehrman, & Espie, 2014; Watson, Goldberg, Arguelles, & Buchwald, 2006). People predisposed to insomnia may have genetic predispositions that make their sleep more reactive to stress or alterations in brain circuits that make stable transitions between wake and sleep more difficult (Kalmbach, Cuamatzi-Castelan, et al., 2018; Riemann et al., 2010). They may also be more psychologically prone to worry or rumination (Lemyre, Belzile, Landry, Bastien, & Beaudoin, 2020), or have a bed partner or children with incompatible sleep schedules (Sprajcer, Stewart, Miller, & Lastella, 2022). Together, a mix of these considerations may make the individual susceptible to precipitating factors that trigger acute sleep continuity disturbance. The primary “triggers” are related to life stress events (real or perceived) (Drake, Pillai, & Roth, 2014), including medical and psychiatric illness (Kalmbach, Anderson, & Drake, 2018). Only a small fraction of those experiencing stress-induced sleep continuity disturbance will progress to insomnia disorder. Current estimates place this figure at 5–10% (Perlis et al., 2020).

Perpetuating factors are patterns of behavior that ultimately maintain an individual’s insomnia. Initially, these behaviors are thought to be largely related to “sleep extension”, i.e., those related to the individual’s attempt to recover lost sleep by sleeping in, going to bed early, or by napping (Ellis et al., 2021). The behaviors run the risk of creating mismatches between one’s sleep ability and sleep opportunity. The greater (or higher the incident rate of) the mismatch, the more likely the bedroom will become associated with wake while other areas and times-of-day become associated with sleep, thus increasing the chances the individual’s insomnia will endure (Birling et al., 2020; Spielman, Saskin, & Thorpy, 1987). Notably, Spielman’s original model has been adapted over the years to consider other perpetuating factors, including the conditioning of somatic and/or cortical arousal to sleep-related stimuli such that wakefulness becomes an elicited response (Espie, 2007; Rasskazova, Zavalko, Tkhostov, & Dorohov, 2014).

Two 3P extensions, referred to as the Neurocognitive and Neurobiological models, have provided additional critical insights into how chronic insomnia is expressed and maintained in the brain (Buysse, Germain, Hall, Monk, & Nofzinger, 2011; Perlis, Giles, Mendelson, Bootzin, & Wyatt, 1997). A synthesis of the two suggests that life stressors, when fleetingly present, create a state of cognitive/cortical arousal (i.e., vigilance) (Freedman, 1986; Lamarche & Ogilvie, 1997). This enhanced vigilance increases sensory and information processing at sleep onset and during cortically defined NREM sleep (Merica, Blois, & Gaillard, 1998; Perlis, Smith, Andrews, Orff, & Giles, 2001), resulting in persistent patterns of mixed wake-like and sleep-like activity in the prefrontal and parietal cortices, paralimbic cortex, thalamus, and hypothalamic-brainstem arousal centers (Nofzinger et al., 2004). Local activation within these regions (local wakefulness) during what is otherwise more globally sleep is thought to facilitate persistent “threat” monitoring of the environment (Colombo et al., 2016). These neuroadaptive changes further perpetuate sleep continuity disturbance and, in addition to sleep extension, may make it increasingly difficult for the individual to perceive their sleep as “sleep” (Krystal, Edinger, Wohlgemuth, & Marsh, 2002; Xu et al., 2022); instead they are left with the impression that they have difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep (Corsi-Cabrera, Rojas-Ramos, & del Rio-Portilla, 2016). Presently, the time course for conditioning insomnia-related neuroadaptive changes is unknown, but presumed to require extended periods of time (i.e., weeks to months). Ultimately, chronic insomnia may be like “sleeping with one eye open” (Van Someren, 2021). As, or more important, the continued perceptual engagement at sleep onset or during NREM sleep, together with extended periods of nocturnal wakefulness, may set the stage for abnormal mood and cognition during the habitual sleep period (Tubbs, Fernandez, Grandner, Perlis, & Klerman, 2022; Tubbs, Fernandez, Johnson, Perlis, & Grandner, 2021; Tubbs, Fernandez, Perlis, et al., 2021).

Insomnia Etiology: The Current State of Pathway Modeling in Animals

Life stressors are precipitating factors for sleep continuity disturbance. Recognition of this gateway to insomnia disorder has motivated extensive study regarding the effects of acute stress on rodent sleep in the lab. Subtle stressors, such as cage changes or exposure to new objects, increase the latency to NREM and REM sleep and decrease total sleep duration (Michaud et al., 1982; Tang, Xiao, Parris, Fang, & Sanford, 2005). Mice genetically predisposed to anxiety exhibit more pronounced sleep reductions after these environmental changes compared to less anxious strains (Tang, Xiao, Liu, & Sanford, 2004; Tang et al., 2005), in keeping with observations in humans that predisposing and precipitating factors may interact to determine the probability of developing insomnia disorder (Palagini, Biber, & Riemann, 2014).

Exposure to intermittent electric shock, a more severe psychological stressor, is also broadly associated with increased wake and less sleep in mice and rats (Jha, Brennan, Pawlyk, Ross, & Morrison, 2005; Kant et al., 1995; Liu, Tang, & Sanford, 2003; Palma, Suchecki, & Tufik, 2000). When electroshocks are delivered in the context of salient cues, simply reintroducing animals to situational reminders of that context—whether they be auditory tones, specific lighting intensity, or the bedding that was slept in that day—increases the amount of time spent awake and fragments sleep continuity, reducing sleep efficiency and the total time spent in REM sleep (Jha et al., 2005; Pawlyk, Jha, Brennan, Morrison, & Ross, 2005; Sanford, Tang, Ross, & Morrison, 2003; Sanford, Yang, & Tang, 2003). The ability of fear-conditioning cues to produce long-standing sleep continuity disturbance and REM sleep deficits in rodents (weeks after the stress exposure) provides a compelling laboratory parallel of how insomnia may be perpetuated in humans.

To be fully relevant to the human condition, stress-perpetuation models of insomnia in rodents should evince individual variability in the degree to which one animal or another will suffer prolonged sleep continuity disturbance after termination of an acute stressor. This appears to be the case. While the issue has not been assessed with foot-shock paradigms, related experiments have been done where groups of rats were submitted to environmental noise for a week (Rabat et al., 2004; Rabat, Bouyer, Aran, Le Moal, & Mayo, 2005; Rabat, Bouyer, George, Le Moal, & Mayo, 2006). Auditory stimulation was designed to be representative of a noisy location for humans. It was composed of a background (70 dB) that was punctuated by several loud unpredictable noise events. The duration of the noise events and the interstimulus interval between them were randomized so that the rats could not habituate to the sound environment. Once free of this stressful situation, many rats showed long-lasting decreases and fragmentation of NREM and REM sleep. However, there was another subpopulation that was resistant to the chronic deleterious effects of environmental noise on sleep continuity (Rabat et al., 2005). The natural segregation of sleep-reactive versus non-reactive animals in stress paradigms such as these (or those employing electric shock) provide alternative tracks by which to examine cases where stress-induced sleep continuity disturbances linger or resolve themselves and how each track is represented in the brain over time.

A related consideration for the development of stress-perpetuation models is that they show the hypothesized patterns of local wakefulness in cortical and subcortical structures of humans with insomnia disorder. Cano and Saper found striking evidence for such changes in the cage exchange paradigm, a rat model of insomnia that creates psychological stress through manipulation of the social context (Cano, Mochizuki, & Saper, 2008). Here, a male rat is transferred to a soiled cage previously occupied by another male rat. Because rats are very territorial, exposure to the olfactory and visual cues of a competitor induces a stress response, including activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis and autonomic nervous system. Several hours later, even when physiologic indicators of acute stress are no longer evident, the circumstances generate sleep disturbance: increased sleep latency, decreased NREM and REM sleep, and decreased sleep continuity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) A representation of the Cano-Saper Model. In this model, stress-naïve male rats are temporarily placed in a cage that had been occupied for a week by another male rat. Acute insomnia is triggered within 5 hours of this placement (2:00–3:00 pm). Relative to control rats moved to a clean cage, those moved to a dirty donor cage show increases in percent time spent awake and number of wake bouts. Significant reductions in both nREM and REM sleep are observed. (B) Changes in the brain resulting from stress-induced insomnia. During normal sleep, circadian and homeostatic drives enhance the activity of the brain’s sleep-promoting centers while also inhibiting the arousal network, favoring the sleep state (the homeostatic effect is mediated in part by adenosine acting on A1 and A2a receptors). Stress activates parts of the arousal system (e.g., LC, TMN) by way of cortical and limbic inputs, thus opposing promotion of the sleep state by the circadian and homeostatic drives. During stress-induced insomnia, cortical and limbic-mediated arousal persists, but homeostatic sleep pressure is stronger than usual because the rats are partially sleep-deprived; On balance, the circadian drive still favors the sleep state. Because these forces are opposing and strong, the sleep-wake switch wavers in an unstable position, leading to an intermediate state in which both sleep and wake circuitries are activated simultaneously. Each state is unable to sufficiently inhibit the other to prevent it from firing. One of the end results of this instability is the increased presence of high frequency EEG activity in the cerebral cortex during what is otherwise global sleep.

A1R, A1 receptor; his, histamine; LC, locus coeruleus; NE, norepinephrine; NREM, non–rapid eye movement; REM, rapid eye movement; TMN, tuberomammillary nucleus; VLPOc, ventrolateral preoptic nucleus core; VLPOex, ventrolateral preoptic nucleus extended.

Cano and Saper measured localized brain activity during the sleep period through immunohistochemical detection of the immediate-early gene c-Fos protein (Cano et al., 2008). This regulatory transcription factor is anatomically distributed throughout the brain. It is rapidly increased from low basal levels by specific forms of patterned spike firing coincident with information processing, and has been employed over the past few decades as a histological record of circuit excitability (Morgan & Curran, 1986; Sagar, Sharp, & Curran, 1988). This readout suggested that the rat brain had assumed a vigilant, mixed sleep-wake state after exposure to the psychological stressor. Sleep-promoting regions like the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) and arousal-promoting regions like the locus coeruleus were simultaneously active, with some elements of the arousal system exhibiting a level of activation commensurate with wakefulness—not sleep. Increased excitability during sleep extended into the cerebral cortex and parts of the limbic system mediating fear learning and threat detection (Canto-de-Souza et al., 2021; Giustino & Maren, 2015; Kim et al., 2013), including the infralimbic cortex (ILC), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST). Interestingly, the cortical cFos signal that proliferated under NREM sleep correlated with high-frequency EEG activity in the gamma band, which is characteristic of focused behavioral arousal in rodents and has been shown in humans experiencing insomnia (Maloney, Cape, Gotman, & Jones, 1997; Perlis et al., 2001). Subsequent experiments by Cano and Saper showed that lesions of the ILC could restore aspects of sleep continuity disrupted by the cage-exchange stress (e.g., wake after sleep onset), while CeA and BST lesions normalized sleep latency. These data were among the first to suggest that: (1) discrete brain areas are required to maintain chronic insomnia in humans; and (2) the ILC and CeA-BST may offer therapeutic routes by which to reverse the prolonged effects of acute stress on sleep continuity.

Optimizing Stress-Perpetuation Models of Insomnia in the Lab

An important point about stress and sleeplessness needs to be addressed before further discussing stress-perpetuation models of insomnia. That point concerns the potentially beneficial nature of acute stress-induced sleep loss. Current prevalence numbers suggest that every adult in the global population will experience three or more nights of insomnia for two or more weeks, if monitored over a three-year period. The near universality of acute insomnia in today’s world suggests that overriding the homeostatic/circadian drive to sleep in the face of perceived danger has been an evolutionary advantage promoting human survival (Nunn, Samson, & Krystal, 2016; Perogamvros, Castelnovo, Samson, & Dang-Vu, 2020). This line of thinking has been aptly summarized in the following sayings:

“It may be the case that we live with insomnia today, because at some point in our evolutionary history insomnia allowed us to live”

“No matter how important sleep may be, it was adaptively deferred when the mountain lion entered the cave”

Indeed, across mammals, predation risk correlates negatively with sleep duration, and is one of the only unifying principles that can explain species-wide divergences in the amount of time animals spend sleeping (Allison & Cicchetti, 1976; Capellini, Barton, McNamara, Preston, & Nunn, 2008). Given this larger evolutionary perspective, it may not be surprising that a single night of total sleep deprivation produces both antidepressant effects (Boland et al., 2017) and memory impairments in people (Yoo, Hu, Gujar, Jolesz, & Walker, 2007). An individual experiencing post-trauma sleeplessness may benefit, for example, from the mood elevations that acute insomnia promotes and might recover faster if they were less responsive to, or less able to recall, the specific details of trauma-related experiences.

Sleep continuity disturbance triggered by the direct presence of stress accommodates behavioral and physiological activities linked to short-term survival, thereby offering advantages for both people and animals in the wild. To understand the pathological processes that contribute to chronic insomnia, however, requires focus on perpetuation models—those where circumscribed exposure to a stressor results in long-term, non-adaptive changes in local wakefulness during sleep that last despite the continuing absence of the stressor. Several rodent models meet this standard on some level, including those involving sleep continuity disturbances produced by random, uncontrollable noise, foot shock, and psychosocial threat. To optimize these models further, the field may want to consider employing longer experimental schedules that chain stronger stress stimuli to more subtle situational cues (e.g., second-order conditioning with the sleep environment itself or specific cues via, in the case of rodents, odor). Even under normal circumstances without imposed stress, rodents actively survey their environment during sleep for smells that could pose a risk to their safety. For example, behavioral and EEG-related arousals from sleep in stress-naïve rats are precipitated by odor cues found in the excrement of predators (foxes) but not from the excrement of unrelated species (lions) (Cattarelli & Chanel, 1979). This raises the possibility of pairing a stressor such as foot shock or social challenge with a previously neutral odor (citrus) and then re-introducing the odor alone whenever the animal falls asleep during its scheduled rest period. After a few weeks, the odor will likely elicit patterns of local wakefulness in the brains of insomnia-vulnerable animals that can be maintained over a consequential period without any further introduction of the odor (perhaps over several months).

How might such a paradigm help us better understand human insomnia disorder? First, it would enable investigators to study a late step in the progression of chronic insomnia that has never really been studied in the lab before: the point at which threat-monitoring during sleep persists even after the situational reminders of a stressor have been removed, i.e., when sleep continuity disturbances are truly self-generated by the animal. Second, it would enable visualizing the progression of acute → chronic insomnia in the brain. Such a progression would likely entail not only “neuroadaptations” in the basic regulatory circuitry underlying sleep/wake transitions but also putative circuits that ensure the lasting deleterious impact of a previously encountered stressor on sleep continuity.

One candidate structure that may continue to signal threat during sleep after all signs of stress have been removed is the ILC (infralimbic cortex), the foremost subdivision of the prefrontal cortex mediating consolidation and retrieval of extinction learning related to classical fear conditioning (Baldi & Bucherelli, 2015; Furlong, Richardson, & McNally, 2016; Santini, Quirk, & Porter, 2008; Sohn et al., 2020). If the ILC fails to link the absence of stress to safety (Corches et al., 2019; Kreutzmann, Jovanovic, & Fendt, 2020; Lehmann & Herkenham, 2011), it is in position to fragment sleep by virtue of its projection fields. Layer 5 of the ILC maintains some of the most prominent afferents to the VLPO “sleep center” that have been documented in the mammalian brain (Chou et al., 2002) and sends discrete projections to all major regions comprising the ascending arousal system, including the lateral hypothalamus, dorsal raphe nuclei, lateral parabrachial nucleus, and locus coeruleus (Flores et al., 2014; Takagishi & Chiba, 1991). This pattern resembles the kinds of connectivity usually only shown by classic components in sleep-wake regulation.

The ILC is also interconnected with the amygdala complex (Bukalo et al., 2021; Khalaf & Graff, 2019), BST (bed nucleus of stria terminalis) (Glover et al., 2020), and lateral septum (Chen et al., 2021), which are other brain structures critical for fear learning and the physiological/behavioral expression of anxiety. Remarkably, these areas maintain prominent afferents of their own with the VLPO and the lateral hypothalamus (Chou et al., 2002; Sakurai et al., 2005; Yoshida, McCormack, Espana, Crocker, & Scammell, 2006). While the ILC has been studied mostly with respect to fear extinction learning, its projections to the BST may subserve specific functions related to limiting fear to uncertain danger (Bayer & Bertoglio, 2020; Glover et al., 2020). If the ILC-BST circuitry fails to keep fear in check under ambiguous circumstances (e.g., perhaps when a stressor has been removed but a few situational reminders linger), then threat-monitoring during sleep is primed to trigger sporadic transitions from deeper to lighter stages of NREM sleep or from NREM sleep to wakefulness (Kodani, Soya, & Sakurai, 2017). These transitions cannot be prevented by even potent methods of arousal suppression such as administration of orexin antagonists (Kodani et al., 2017). By and large, the aforementioned data suggest the ILC is centered at a crossroads that–when taxed—might enable strong fear associations to overcome attempts at extinction, and in doing so, trigger bursts of arousal during both sleep and wake (Chang, Chen, Qiu, & Lu, 2014; Nofzinger, Mintun, Wiseman, Kupfer, & Moore, 1997). In turn, it can be argued that impaired fear extinction learning lies at the root of the progression from acute insomnia to insomnia disorder. Future efforts aimed at mitigating insomnia symptoms might thus be directed at understanding the original stressor that precipitated sleeplessness and helping the patient to resolve the direct and tangential issues associated with the stressor.

Rodent stress-perpetuation models would enable a detailed longitudinal dissection of how chronic local wakefulness in the brain during sleep slowly elicits maladaptive changes that may make uniform states of wake or sleep difficult (e.g., through changes in among other areas the ILC network). They would also provide a template to study interventions for insomnia disorder that center on correcting the mismatch between an individual’s sleep ability and sleep opportunity—a gulf that opens as one attempts to expand the time allocated for sleep but that ends up reinforcing and perpetuating their insomnia. The only animal model that has previously addressed this etiological factor of insomnia was developed by Belfer and Kayser, who used the light-dark cycle to control the length of sleep opportunity given each night to various short-sleeping Drosophila mutants (Belfer, Bashaw, Perlis, & Kayser, 2021). By shortening the dark period and restricting sleep opportunity, the researchers found that they could decrease the flies’ sleep latency and reduce the amount of intermittent wake that occurred after sleep had started, thus increasing sleep continuity (Figure 3). The alignment of sleep ability and opportunity was associated with extended lifespan in sleep-deficient flies genetically designed to exhibit the molecular pathology of Alzheimer disease (Belfer et al., 2021). Generalizing study of this part of the 3P model to rodent stress-perpetuation models would enable investigation in a mammalian system of the neurobiological basis for sleep restriction therapy, an intervention that is highly effective for treating insomnia disorder in humans but whose effects on the brain remain unknown.

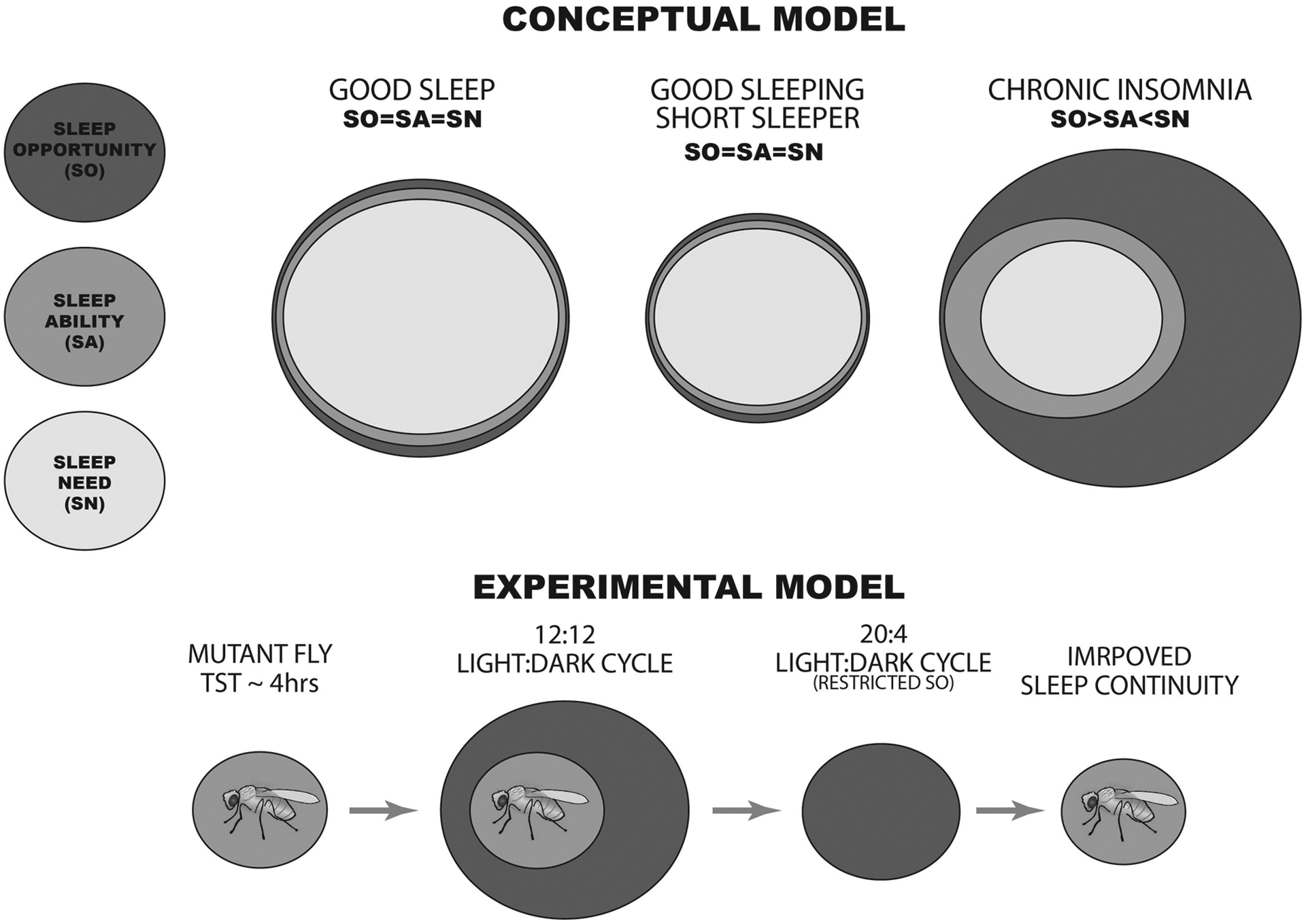

Figure 3.

(Conceptual Model) The top panel represents the three measures that factor into “good and bad” sleep continuity: sleep opportunity (SO), sleep ability (SA), and sleep need (SN). For short sleepers, sleep continuity is optimized when these factors are closely matched (SO=SA=SN). However, chronic insomnia can result when one’s sleep opportunity exceeds their need and ability to sleep. (Experimental Results) The bottom panel summarizes experimental observations made by Belfer and Kayser using short-sleeping mutant flies averaging 4 hours of total sleep time (TST) per 24-hour day. Sleep continuity was poor in these diurnal animals when they were maintained under a light:dark cycle providing 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness (12:12). It was significantly improved, however, when the animals were housed under a photoperiod that provided only 4 hours of darkness, affording a length of sleep opportunity that matched the flies’ sleep ability.

Summary

We have reviewed existing animal models of insomnia, highlighting particular models that do not just force sleeplessness on normally sleeping animals but that recreate the putative etiological pathway thought to contribute to insomnia disorder in humans. As part of this effort, we have provided suggestions on improving the way that stress and sleep continuity disturbance are investigated in the lab so that acute stress gives way to a stress-free period in which sleep problems persist. Self-generated sleep loss, while potentially related to many neuroadaptive changes, may be underpinned by failed attempts by parts of the prefrontal cortex to defuse the salience of the original stressor that precipitated insomnia. Neurobiologic regions likely associated with such a phenomenon include the ILC (infralimbic cortex), where enhanced threat-monitoring during what is otherwise more globally sleep may perpetuate sleep continuity disturbance and concurrently result in sleep-state misperception. By virtue of the ILC’s direct and secondary connectivity with sleep/arousal centers, the cortex, limbic system and brain stem, patterns of local wakefulness spill over into the locus coeruleus, thereby fragmenting NREM and REM sleep and undermining the potential of REM-related emotional regulation. The stress-perpetuation models proposed here would offer a granular look at these processes once a state of chronic insomnia is reached and a model for testing behavioral and pharmacologic interventions that restore sleep continuity. All these considerations would create closer parallels between human and animal insomnia, which will be imperative for addressing the wider health effects stemming from the current global insomnia epidemic.

Acknowledgements

FXF acknowledges support from the Velux Stiftung (Proj. No. 1360). MLP is supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (K24AG055602, R01AG054521).

References

- Alfoldi P, Rubicsek G, Cserni G, & Obal F Jr. (1990). Brain and core temperatures and peripheral vasomotion during sleep and wakefulness at various ambient temperatures in the rat. Pflugers Arch, 417(3), 336–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00371001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, & Cicchetti DV (1976). Sleep in mammals: ecological and constitutional correlates. Science, 194(4266), 732–734. doi: 10.1126/science.982039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici R, Zamboni G, Perez E, Jones CA, Toni II, Culin F, & Parmeggiani PL (1994). Pattern of desynchronized sleep during deprivation and recovery induced in the rat by changes in ambient temperature. J Sleep Res, 3(4), 250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1994.tb00139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andretic R, & Shaw PJ (2005). Essentials of sleep recordings in Drosophila: moving beyond sleep time. Methods Enzymol, 393, 759–772. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93040-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi E, & Bucherelli C (2015). Brain sites involved in fear memory reconsolidation and extinction of rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 53, 160–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer H, & Bertoglio LJ (2020). Infralimbic cortex controls fear memory generalization and susceptibility to extinction during consolidation. Sci Rep, 10(1), 15827. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72856-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfer SJ, Bashaw AG, Perlis ML, & Kayser MS (2021). A Drosophila model of sleep restriction therapy for insomnia. Mol Psychiatry, 26(2), 492–507. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0376-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birling Y, Li G, Jia M, Zhu X, Sarris J, Bensoussan A, … Fahey P (2020). Is insomnia disorder associated with time in bed extension? Sleep Sci, 13(4), 215–219. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20200089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland EM, Rao H, Dinges DF, Smith RV, Goel N, Detre JA, … Gehrman PR (2017). Meta-Analysis of the Antidepressant Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation. J Clin Psychiatry, 78(8), e1020–e1034. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16r11332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin P, Huitron-Resendiz S, Spier AD, Fabre V, Morte B, Criado JR, … de Lecea L (2000). Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurosci, 20(20), 7760–7765. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11027239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukalo O, Nonaka M, Weinholtz CA, Mendez A, Taylor WW, & Holmes A (2021). Effects of optogenetic photoexcitation of infralimbic cortex inputs to the basolateral amygdala on conditioned fear and extinction. Behav Brain Res, 396, 112913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ (2013). Insomnia. JAMA, 309(7), 706–716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Germain A, Hall M, Monk TH, & Nofzinger EA (2011). A Neurobiological Model of Insomnia. Drug Discov Today Dis Models, 8(4), 129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano G, Mochizuki T, & Saper CB (2008). Neural circuitry of stress-induced insomnia in rats. J Neurosci, 28(40), 10167–10184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1809-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto-de-Souza L, Demetrovich PG, Plas S, Souza RR, Epperson J, Wahlstrom KL, … McIntyre CK (2021). Daily Optogenetic Stimulation of the Left Infralimbic Cortex Reverses Extinction Impairments in Male Rats Exposed to Single Prolonged Stress. Front Behav Neurosci, 15, 780326. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.780326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capellini I, Barton RA, McNamara P, Preston BT, & Nunn CL (2008). Phylogenetic analysis of the ecology and evolution of mammalian sleep. Evolution, 62(7), 1764–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00392.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattarelli M, & Chanel J (1979). Influence of some biologically meaningful odorants on the vigilance states of the rat. Physiol Behav, 23(5), 831–838. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90186-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattarelli M, Pager J, & Chanel J (1977). [Modulation of the multiunit responses of the olfactory bulb and respiratory activity as a function of the significance of odors in freely moving rats]. J Physiol (Paris), 73(7), 963–984. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/614410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerri M, Ocampo-Garces A, Amici R, Baracchi F, Capitani P, Jones CA, … Zamboni G (2005). Cold exposure and sleep in the rat: effects on sleep architecture and the electroencephalogram. Sleep, 28(6), 694–705. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.6.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Chen MC, Qiu MH, & Lu J (2014). Ventromedial prefrontal cortex regulates depressive-like behavior and rapid eye movement sleep in the rat. Neuropharmacology, 86, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Wu JL, Hu NY, Zhuang JP, Li WP, Zhang SR, … Gao TM (2021). Distinct projections from the infralimbic cortex exert opposing effects in modulating anxiety and fear. J Clin Invest, 131(14). doi: 10.1172/JCI145692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Bjorkum AA, Gaus SE, Lu J, Scammell TE, & Saper CB (2002). Afferents to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. J Neurosci, 22(3), 977–990. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11826126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo MA, Ramautar JR, Wei Y, Gomez-Herrero G, Stoffers D, Wassing R, … Van Someren EJ (2016). Wake High-Density Electroencephalographic Spatiospectral Signatures of Insomnia. Sleep, 39(5), 1015–1027. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corches A, Hiroto A, Bailey TW, Speigel JH 3rd, Pastore J, Mayford M, & Korzus E (2019). Differential fear conditioning generates prefrontal neural ensembles of safety signals. Behav Brain Res, 360, 169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.11.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi-Cabrera M, Rojas-Ramos OA, & del Rio-Portilla Y (2016). Waking EEG signs of non-restoring sleep in primary insomnia patients. Clin Neurophysiol, 127(3), 1813–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CL, Pillai V, & Roth T (2014). Stress and sleep reactivity: a prospective investigation of the stress-diathesis model of insomnia. Sleep, 37(8), 1295–1304. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JG, Gehrman P, Espie CA, Riemann D, & Perlis ML (2012). Acute insomnia: current conceptualizations and future directions. Sleep Med Rev, 16(1), 5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JG, Perlis ML, Espie CA, Grandner MA, Bastien CH, Barclay NL, … Gardani M (2021). The natural history of insomnia: predisposing, precipitating, coping, and perpetuating factors over the early developmental course of insomnia. Sleep, 44(9). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie CA (2007). Understanding insomnia through cognitive modelling. Sleep Med, 8 Suppl 4, S3–8. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores A, Valls-Comamala V, Costa G, Saravia R, Maldonado R, & Berrendero F (2014). The hypocretin/orexin system mediates the extinction of fear memories. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(12), 2732–2741. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RR (1986). EEG power spectra in sleep-onset insomnia. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 63(5), 408–413. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90122-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong TM, Richardson R, & McNally GP (2016). Habituation and extinction of fear recruit overlapping forebrain structures. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 128, 7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais R, & Pager J (1979). Combined modulating effects of the general arousal and the specific hunger arousal on the olfactory bulb responses in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 46(1), 87–94. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90053-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustino TF, & Maren S (2015). The Role of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in the Conditioning and Extinction of Fear. Front Behav Neurosci, 9, 298. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover LR, McFadden KM, Bjorni M, Smith SR, Rovero NG, Oreizi-Esfahani S, … Holmes A (2020). A prefrontal-bed nucleus of the stria terminalis circuit limits fear to uncertain threat. Elife, 9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison ST (2022). What have we learned about sleep from selective breeding strategies? Sleep. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsac147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CJ, Gehrman P, & Espie CA (2014). Who is predisposed to insomnia: a review of familial aggregation, stress-reactivity, personality and coping style. Sleep Med Rev, 18(3), 237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Mendelson WB, & Bernstein DA (1977). Cocaine effects on sleep parameters in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 51(2), 125–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00431727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZL, Qu WM, Li WD, Mochizuki T, Eguchi N, Watanabe T, … Hayaishi O (2001). Arousal effect of orexin A depends on activation of the histaminergic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98(17), 9965–9970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181330998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha SK, Brennan FX, Pawlyk AC, Ross RJ, & Morrison AR (2005). REM sleep: a sensitive index of fear conditioning in rats. Eur J Neurosci, 21(4), 1077–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03920.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmbach DA, Anderson JR, & Drake CL (2018). The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J Sleep Res, 27(6), e12710. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmbach DA, Cuamatzi-Castelan AS, Tonnu CV, Tran KM, Anderson JR, Roth T, & Drake CL (2018). Hyperarousal and sleep reactivity in insomnia: current insights. Nat Sci Sleep, 10, 193–201. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S138823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant GJ, Pastel RH, Bauman RA, Meininger GR, Maughan KR, Robinson TN 3rd, … Covington PS (1995). Effects of chronic stress on sleep in rats. Physiol Behav, 57(2), 359–365. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00241-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf O, & Graff J (2019). Reactivation of Recall-Induced Neurons in the Infralimbic Cortex and the Basolateral Amygdala After Remote Fear Memory Attenuation. Front Mol Neurosci, 12, 70. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Adhikari A, Lee SY, Marshel JH, Kim CK, Mallory CS, … Deisseroth K (2013). Diverging neural pathways assemble a behavioural state from separable features in anxiety. Nature, 496(7444), 219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani S, Soya S, & Sakurai T (2017). Excitation of GABAergic Neurons in the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis Triggers Immediate Transition from Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep to Wakefulness in Mice. J Neurosci, 37(30), 7164–7176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0245-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzmann JC, Jovanovic T, & Fendt M (2020). Infralimbic cortex activity is required for the expression but not the acquisition of conditioned safety. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 237(7), 2161–2172. doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05527-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal AD, Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, & Marsh GR (2002). NREM sleep EEG frequency spectral correlates of sleep complaints in primary insomnia subtypes. Sleep, 25(6), 630–640. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12224842 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche CH, & Ogilvie RD (1997). Electrophysiological changes during the sleep onset period of psychophysiological insomniacs, psychiatric insomniacs, and normal sleepers. Sleep, 20(9), 724–733. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9406324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann ML, & Herkenham M (2011). Environmental enrichment confers stress resiliency to social defeat through an infralimbic cortex-dependent neuroanatomical pathway. J Neurosci, 31(16), 6159–6173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0577-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemyre A, Belzile F, Landry M, Bastien CH, & Beaudoin LP (2020). Pre-sleep cognitive activity in adults: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev, 50, 101253. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Tang X, & Sanford LD (2003). Fear-conditioned suppression of REM sleep: relationship to Fos expression patterns in limbic and brainstem regions in BALB/cJ mice. Brain Res, 991(1–2), 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney KJ, Cape EG, Gotman J, & Jones BE (1997). High-frequency gamma electroencephalogram activity in association with sleep-wake states and spontaneous behaviors in the rat. Neuroscience, 76(2), 541–555. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00298-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson WB, Guthrie RD, Frederick G, & Wyatt RJ (1974). The flower pot technique of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep deprivation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 2(4), 553–556. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(74)90018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merica H, Blois R, & Gaillard JM (1998). Spectral characteristics of sleep EEG in chronic insomnia. Eur J Neurosci, 10(5), 1826–1834. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JC, Muyard JP, Capdevielle G, Ferran E, Giordano-Orsini JP, Veyrun J, … Mouret J (1982). Mild insomnia induced by environmental perturbations in the rat: a study of this new model and of its possible applications in pharmacological research. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther, 259(1), 93–105. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6891203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JI, & Curran T (1986). Role of ion flux in the control of c-fos expression. Nature, 322(6079), 552–555. doi: 10.1038/322552a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, & Benca R (2012). Chronic insomnia. Lancet, 379(9821), 1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Drake CL, Harvey AG, Krystal AD, Manber R, Riemann D, & Spiegelhalder K (2015). Insomnia disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 1, 15026. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, & Kupfer DJ (2004). Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry, 161(11), 2126–2128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofzinger EA, Mintun MA, Wiseman M, Kupfer DJ, & Moore RY (1997). Forebrain activation in REM sleep: an FDG PET study. Brain Res, 770(1–2), 192–201. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00807-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn CL, Samson DR, & Krystal AD (2016). Shining evolutionary light on human sleep and sleep disorders. Evol Med Public Health, 2016(1), 227–243. doi: 10.1093/emph/eow018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuma T, Matsuoka H, Matsue Y, & Toyomura K (1982). Model insomnia by methylphenidate and caffeine and use in the evaluation of temazepam. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 76(3), 201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00432545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palagini L, Biber K, & Riemann D (2014). The genetics of insomnia--evidence for epigenetic mechanisms? Sleep Med Rev, 18(3), 225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma BD, Suchecki D, & Tufik S (2000). Differential effects of acute cold and footshock on the sleep of rats. Brain Res, 861(1), 97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlyk AC, Jha SK, Brennan FX, Morrison AR, & Ross RJ (2005). A rodent model of sleep disturbances in posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of context after fear conditioning. Biol Psychiatry, 57(3), 268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Giles DE, Mendelson WB, Bootzin RR, & Wyatt JK (1997). Psychophysiological insomnia: the behavioural model and a neurocognitive perspective. J Sleep Res, 6(3), 179–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Posner D, Riemann D, Bastien CH, Teel J, & Thase M (2022). Insomnia. Lancet, 400(10357), 1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00879-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Smith MT, Andrews PJ, Orff H, & Giles DE (2001). Beta/Gamma EEG activity in patients with primary and secondary insomnia and good sleeper controls. Sleep, 24(1), 110–117. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Vargas I, Ellis JG, Grandner MA, Morales KH, Gencarelli A, … Thase ME (2020). The Natural History of Insomnia: the incidence of acute insomnia and subsequent progression to chronic insomnia or recovery in good sleeper subjects. Sleep, 43(6). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perogamvros L, Castelnovo A, Samson D, & Dang-Vu TT (2020). Failure of fear extinction in insomnia: An evolutionary perspective. Sleep Med Rev, 51, 101277. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, & McCarley RW (1997). Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science, 276(5316), 1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabat A, Bouyer JJ, Aran JM, Courtiere A, Mayo W, & Le Moal M (2004). Deleterious effects of an environmental noise on sleep and contribution of its physical components in a rat model. Brain Res, 1009(1–2), 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabat A, Bouyer JJ, Aran JM, Le Moal M, & Mayo W (2005). Chronic exposure to an environmental noise permanently disturbs sleep in rats: inter-individual vulnerability. Brain Res, 1059(1), 72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabat A, Bouyer JJ, George O, Le Moal M, & Mayo W (2006). Chronic exposure of rats to noise: relationship between long-term memory deficits and slow wave sleep disturbances. Behav Brain Res, 171(2), 303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasskazova E, Zavalko I, Tkhostov A, & Dorohov V (2014). High intention to fall asleep causes sleep fragmentation. J Sleep Res, 23(3), 295–301. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtschaffen A, & Bergmann BM (1995). Sleep deprivation in the rat by the disk-over-water method. Behav Brain Res, 69(1–2), 55–63. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00020-t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revel FG, Gottowik J, Gatti S, Wettstein JG, & Moreau JL (2009). Rodent models of insomnia: a review of experimental procedures that induce sleep disturbances. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 33(6), 874–899. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis JG, … Spiegelhalder K (2017). European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res, 26(6), 675–700. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Voderholzer U, Berger M, Perlis M, & Nissen C (2010). The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev, 14(1), 19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Sharp FR, & Curran T (1988). Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science, 240(4857), 1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y, … Yanagisawa M (2005). Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron, 46(2), 297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford LD, Tang X, Ross RJ, & Morrison AR (2003). Influence of shock training and explicit fear-conditioned cues on sleep architecture in mice: strain comparison. Behav Genet, 33(1), 43–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1021051516829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford LD, Yang L, & Tang X (2003). Influence of contextual fear on sleep in mice: a strain comparison. Sleep, 26(5), 527–540. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Quirk GJ, & Porter JT (2008). Fear conditioning and extinction differentially modify the intrinsic excitability of infralimbic neurons. J Neurosci, 28(15), 4028–4036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Scammell TE, & Lu J (2005). Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature, 437(7063), 1257–1263. doi: 10.1038/nature04284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet L, Suzuki Y, Thimgan M, Donlea J, Gimbel SI, Gottschalk L, … Shaw PJ (2009). Identifying sleep regulatory genes using a Drosophila model of insomnia. J Neurosci, 29(22), 7148–7157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5629-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekleton JA, Rogers NL, & Rajaratnam SM (2010). Searching for the daytime impairments of primary insomnia. Sleep Med Rev, 14(1), 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, & Mallick BN (1996). Mild electrical stimulation of pontine tegmentum around locus coeruleus reduces rapid eye movement sleep in rats. Neurosci Res, 24(3), 227–235. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00998-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn JMB, de Souza STF, Raymundi AM, Bonato J, de Oliveira RMW, Prickaerts J, & Stern CA (2020). Persistence of the extinction of fear memory requires late-phase cAMP/PKA signaling in the infralimbic cortex. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 172, 107244. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman AJ, Caruso LS, & Glovinsky PB (1987). A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am, 10(4), 541–553. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3332317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman AJ, Saskin P, & Thorpy MJ (1987). Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep, 10(1), 45–56. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3563247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprajcer M, Stewart D, Miller D, & Lastella M (2022). Sleep and sexual satisfaction in couples with matched and mismatched chronotypes: A dyadic cross-sectional study. Chronobiol Int, 39(9), 1249–1255. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2022.2093213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagishi M, & Chiba T (1991). Efferent projections of the infralimbic (area 25) region of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tracer PHA-L study. Brain Res, 566(1–2), 26–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91677-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Xiao J, Liu X, & Sanford LD (2004). Strain differences in the influence of open field exposure on sleep in mice. Behav Brain Res, 154(1), 137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Xiao J, Parris BS, Fang J, & Sanford LD (2005). Differential effects of two types of environmental novelty on activity and sleep in BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav, 85(4), 419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Pompeiano M, & Pompeiano O (1989). Modulation of desynchronized sleep through microinjection of beta-adrenergic agonists and antagonists in the dorsal pontine tegmentum of the cat. Pflugers Arch, 415(2), 142–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00370584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth LA, & Bhargava P (2013). Animal models of sleep disorders. Comp Med, 63(2), 91–104. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23582416 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs AS, Fernandez FX, Grandner MA, Perlis ML, & Klerman EB (2022). The Mind After Midnight: Nocturnal Wakefulness, Behavioral Dysregulation, and Psychopathology. Front Netw Physiol, 1. doi: 10.3389/fnetp.2021.830338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs AS, Fernandez FX, Johnson DA, Perlis ML, & Grandner MA (2021). Nocturnal and Morning Wakefulness Are Differentially Associated With Suicidal Ideation in a Nationally Representative Sample. J Clin Psychiatry, 82(6). doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs AS, Fernandez FX, Perlis ML, Hale L, Branas CC, Barrett M, … Grandner MA (2021). Suicidal ideation is associated with nighttime wakefulness in a community sample. Sleep, 44(1). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Luijtelaar EL, & Coenen AM (1986). Electrophysiological evaluation of three paradoxical sleep deprivation techniques in rats. Physiol Behav, 36(4), 603–609. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90341-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Someren EJW (2021). Brain mechanisms of insomnia: new perspectives on causes and consequences. Physiol Rev, 101(3), 995–1046. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00046.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velluti RA (1997). Interactions between sleep and sensory physiology. J Sleep Res, 6(2), 61–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, & Fernandez-Mendoza J (2013). Insomnia with Short Sleep Duration: Nosological, Diagnostic, and Treatment Implications. Sleep Med Clin, 8(3), 309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, & Deboer T (2022). Long-Term Effect of a Single Dose of Caffeine on Sleep, the Sleep EEG and Neuronal Activity in the Peduncular Part of the Lateral Hypothalamus under Constant Dark Conditions. Clocks Sleep, 4(2), 260–276. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep4020023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NF, Goldberg J, Arguelles L, & Buchwald D (2006). Genetic and environmental influences on insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and obesity in twins. Sleep, 29(5), 645–649. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.5.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Cai Q, Mai R, Liang H, Huang J, & Yang Z (2022). Sleep EEG characteristics associated with total sleep time misperception in young adults: an exploratory study. Behav Brain Funct, 18(1), 2. doi: 10.1186/s12993-022-00188-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanik G, Glaum S, & Radulovacki M (1987). The dose-response effects of caffeine on sleep in rats. Brain Res, 403(1), 177–180. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90141-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SS, Hu PT, Gujar N, Jolesz FA, & Walker MP (2007). A deficit in the ability to form new human memories without sleep. Nat Neurosci, 10(3), 385–392. doi: 10.1038/nn1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, McCormack S, Espana RA, Crocker A, & Scammell TE (2006). Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol, 494(5), 845–861. doi: 10.1002/cne.20859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]