Abstract

International student exchange programs have gained popularity as a means to increase enrollments, support international academic partnerships, and improve student preparedness for globalized work environments. However, the relationships between English language proficiency, cultural intelligence, teamwork, self-efficacy, academic success, and other factors within these programs are not clear. This study investigates the correlations among international accounting students’ English language proficiency, accounting knowledge, and academic performance in a transnational education program in mainland China. Data were obtained from academic records of 104 accounting students enrolled in the program. A quantitative measuring of the Pearson correlation statistical tests were employed to measure the relationships between English language proficiency and academic performance, as well as between previous accounting knowledge and academic success. The results indicate a statistically significant relationship between English language proficiency and academic performance, and between previous accounting knowledge and academic success. This study has significant implications for transnational education programs, academic institutions, and policymakers and provides insights into effective strategies for enhancing the quality of transnational education programs and promoting the internationalization of higher education.

Keywords: International management education, Collaborative instruction, Partnerships, Cross-cultural issues in management educations, Cross-national education

1. Introduction

Transnational higher education (TNHE) has emerged as a significant form of internationalization in higher education organizations. TNHE refers to post-secondary institutions that offer educational programs or services to students from other countries [1]. Knight [2] terms TNHE as cross-border or borderless higher education. The primary forms of TNHE are franchised or partnership programs, joint- or double-degree programs, distance or online education, and international branch locations.

Many universities in developed countries, including the United States and Canada, offer transnational education programs also known as offshore programs in Asian countries like China. The number of international students studying in developed countries has grown tremendously. Globally, international student enrollment has increased from 1.3 million in 1990 to 5 million in 2015. This number increased by 70% between 2001 and 2015 [3]. The number of international students studying at colleges and universities in the United States has increased to 948,519 in the 2021–2022 academic year [4]. International student enrollments are expected to reach more than 8 million by 2025 [5]. Many colleges and universities depend heavily on overseas student revenue for their continuing operations [2,6].

International students bring tuition revenue to host higher education institutions. In the United States, for instance, international students have brought around US$ 13.5 billion to higher education institutions and local communities from 2005 to 2006 [5]. On average, international students pay tuition fees of US$ 25,000 [7]. The expansion of overseas student programs can bring considerable economic and financial benefits to developed countries [5,8,9] and is vital to higher education sustainability.

In franchised or partnership programs, the home institution arranges the curricula, accredits the degree awarded, and is accountable for education quality, while learners receive education at a local university in the host country [10]. In joint- or double-degree programs, students start the degree program at a local university and then finish the program at a partner foreign education provider, receiving two degrees—one from each partner university.

Virtual and distance education programs refer to massive open online courses (MOOCs) and Internet-based programs. Technology development influences the faculty's approach to delivering instruction and enriches students' learning experiences. International branch campuses (IBC) are overseas branches of higher education institutions that honor degrees of home universities [1]. The internationalization of higher education dominates university campuses worldwide [11].

Chinese accounting and business students constitute a significant proportion of international students. In 2017, Canada reported 140,530 Chinese students, accounting for 28% of the total number of international students enrolled. Among these Chinese students, 74,260 were enrolled in university programs, while 16,895 were college students [12]. China is the leading source of foreign students in the United States’ higher education sector [4,[12], [13], [14]] with 290,086 students in the 2021–2022 academic year. Approximately 15.5% international students chose to study in business and management programs during the 2021–2022 academic year [4].

Accounting is a popular and practical major in transnational education programs owing to the increasing phenomenon of globalization in recent years. Multinational companies transfer resources, goods, knowledge, skills, and information across borders [15]. Accounting is necessary for all types of international entities, including non-profit organizations, for-profit companies, and governmental agencies, making it globally applicable [16]. Accounting graduates with international backgrounds are in high demand by international companies, making the focus on accounting education's transnational dimensions significant.

However, some international accounting majors face challenges when studying abroad. Specifically, they have problems with their English language proficiency, which is essential for understanding course materials in a foreign language that they may not have mastered while overseas [17]. Some struggle with accounting foundations, which can lead to difficulties in understanding accounting materials abroad. The lack of foundational knowledge of accounting practices in the host country can cause students to struggle with learning the theoretical and regulatory content, leading to learning issues for international students [12].

To succeed academically, international students are encouraged to develop English language proficiency, primarily verbal and writing communication skills, and have a solid accounting foundation [18]. There is limited study on accounting students' preparedness for English language proficiency and accounting education under transnational education programs' context, although numerous studies have indicated that these are key factors associated with academic success. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate accounting students' preparedness for studying abroad with regard to English language proficiency and accounting knowledge in a transnational education program in China. We will determine the correlations among preparedness for English language proficiency, accounting knowledge, and academic performance. This study will select accounting students enrolled in a transnational education program who have undergone English skills training and foundational accounting coursework before going abroad.

1.1. Theoretical framework

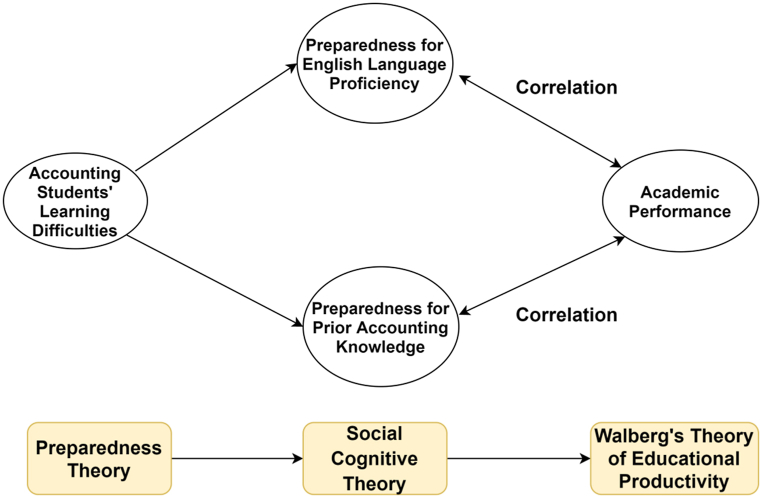

This research adopts preparedness theory, social cognitive theory, and the theory of educational productivity (as shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework.

Prior knowledge and learning experiences in English language and accounting foundations play a crucial role in the academic success of international students [8,19]. This study focuses on accounting students' preparedness for English language proficiency and accounting knowledge, and how these factors relate to academic performance in transnational education programs. According to Seligman's preparedness theory [20], individuals are biologically predisposed to develop selective and conditioned fear responses, which may represent planned learning processes. Hence, accounting students are more likely to prepare for English language proficiency and build a solid accounting foundation before studying abroad.

Social cognitive theory [21] posits that individuals' behavior, environment, and previous experiences influence learning. Reinforcement behavior and expectations are shaped by previous experiences, and self-efficacy refers to individuals' belief in their ability to achieve their goals [22]. Accounting students prepare for English language proficiency and accounting foundations and believe that they can achieve academic success. Social cognitive theory helps explain whether accounting students engage in previous learning and why they achieve later academic success.

Walberg's theory of educational productivity identifies key variables that affect learning outcomes, including students' previous academic success, the quantity and quality of teaching, studying environments, and age. Standardized examinations are used to evaluate students' abilities and previous success. A strong correlation exists between past achievements and later learning [23]. Walberg's theory of educational productivity provides the foundation for the relationship between prior experience and academic success. Hence, this study assumes that accounting students' previous academic preparedness is statistically significantly associated with their academic performance in transnational education programs.

Many overseas students encounter difficulties after arriving in different countries [21]. Findlay and Findlay [8] explore the learning experience of a cohort of Chinese accounting students who have completed two years of study in colleges or universities in China and then transferred their credits to a Scottish University to earn an undergraduate degree. Their findings indicate that international students' learning experiences focus on language, accounting terminology, and theories. English language proficiency and business or accounting knowledge are the key factors associated with academic achievement. Understanding the factors related to academic success and failure [24] can enhance participation in higher education in international accounting. However, research determining the correlations among Chinese accounting students’ preparedness for English language proficiency, accounting knowledge, and academic performance in transnational education programs is limited.

1.2. English language proficiency

English is considered a global language [25]. In the United States, English proficiency refers to “the different degree of fluency in the English language” [26, p.7]. The four language skills—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—are used to assess English language proficiency [25,26].

The ability to communicate effectively in English is crucial to maximizing cross-border productivity, and language competence is essential to integrating knowledge [26,27]. However, international graduates consider English speaking and listening skills to be major challenges in today's globalized world [19,25,28]. Despite high scores on standardized tests such as TOEFL, IELTS, and GRE, many international students from China, Japan, Vietnam, and Indonesia face difficulties communicating in the classroom, leading to reduced confidence and hindered learning [5,25,28].

English is taught with limited attention to conversational skills in some Asian countries, and students have few opportunities to use English outside the classroom [25]. Although universities have minimum language proficiency requirements, many international students do not sufficiently practice speaking in English. They may feel too afraid or hesitant to speak in class or participate in class discussions, which negatively affects their learning [27,28]. Inability to comprehend English owing to different accents, speaking speed, and clarity further exacerbate these challenges, making it difficult for international students to understand professors in class. Taking notes, participating in class discussions, or writing assignments may also prove difficult. Slang, idioms, and local jokes used by lecturers can further increase these language barriers [27,28]. Cultural differences between host and home countries may also contribute to communication difficulties [28]. To prepare for English communication before embarking on higher education exchange programs, international students should evaluate their language proficiency and learn to adapt to different accents used by professors [28].

Chinese students often have fewer problems with reading, but encounter difficulties in writing essays across academic disciplines when studying abroad [19,27,29,30]. The previous learning experiences of international students may affect their learning difficulties [25,29,31]. Lack of confidence in their language proficiency often results in memorizing course content, which may lead to negative outcomes [27,31]. Poor grammar can also affect the academic success of international students, as Asian students tend to focus on grammar and reading skills rather than developing effective communication skills [25]. International students should familiarize themselves with different teaching and learning methods to overcome poor English language proficiency and effectively adapt to academic requirements in English-speaking countries [27,31]. However, little attention has been paid to enhance their preparation for English language skills before embarking on studies in English-speaking countries [25,31].

Owing to the significance of English language proficiency in studying abroad, many researchers have studied the relationship between English language proficiency and business or accounting academic performance. Some results demonstrate that English language proficiency has no significant relationship with accounting academic performance [[32], [33], [34], [35]].

Cai et al. [32] examine whether English language proficiency influences academic understanding of accounting content and explore the factors that may impact accounting education. They show that English majors do not perform better in accounting courses than those who are not English majors, suggesting that there is no significant relationship between English language proficiency and performance in accounting courses. Krausz et al. [33] use TOEFL scores to measure students’ English language proficiency and find that the scores have no significant relationship with academic performance in the graduate accounting courses for international MBA students.

Syafinaz et al. [34] investigate the factors, such as class presence, course activities, work experience, and English language proficiency, affecting student failures in advanced financial accounting courses. They reveal that English language proficiency does not significantly influence the student failure rate in advanced financial accounting courses. Understanding the content of the courses rather than English language proficiency is more important for students who want to pass the course. Further analysis reveals that English language proficiency and curricular activities are important factors for students to succeed in advanced financial accounting courses, whereas accounting work experience and class presence are unimportant factors [34].

Wong and Chia [35] examine the interaction between English language proficiency and academic performance in mathematics among first-year accounting students in a financial accounting course. Mathematics abilities represent numerical skills, whereas English language proficiency represents communication competence. Their findings reveal that higher mathematics proficiency is associated with a higher grade in financial accounting courses for accounting students with advanced English language proficiency.

By contrast, Ghenghesh [36] and Martirosyan, Hwang, and Wanjohi [37] find a significant relationship between English language proficiency and academic performance. Ghenghesh [36] finds significant differences between self-perceived English language proficiency and the academic success of international students majoring in engineering, informatics and computer science, economics, political science, and business administration. Ghenghesh [36] also examines international students who speak several languages and their academic success. Students with the highest average GPA could speak in more than three languages with English as their third language. Students with the lowest average GPA considered English as their second language.

Martirosyan et al. [37] find a significant moderate positive relationship between English language proficiency and the GPA of preparatory-year students majoring in business and two other non-business-related courses. Martirosyan et al. [37] also reveal that an improvement in students’ English language proficiency leads to enhanced academic performance in both English and related degree courses.

1.3. Prior accounting knowledge

With the enactment of updated accounting standards by the International Accounting Standards Board, universities need to work together to broaden accounting education, equipping undergraduates and graduates with new professional skills [[38], [39], [40]]. Additionally, the International Accounting Education Standards Board has released eight standards that establish international benchmarks for accounting education and professional development. International education standards focus on quality and consistency in international accounting education and offer standards for the professional growth of accountants and auditors. These standards apply directly to professional accounting bodies that influence universities and other organizations, linking universities with professional requirements [41].

In the United States, accounting academic programs require international accounting coursework. Accounting graduates need to have knowledge of international business and accounting to understand multinational corporations’ financial statements in an international context. Students with a background in international accounting education are in demand. The challenge in accounting education and practice is how to globalize the entire accounting system [42].

Because accounting students' awareness, motivation, and readiness are critical for their careers, Samsuddin et al. [43] examine these aspects for professional accounting education in Malaysia. The Malaysian government has built a professional accounting center to increase the number of professional accountants in the country. The center provides professional accounting trainings for students who want to obtain certification from the “Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), Certified Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), and Malaysian Institute of Certified Public Accountants (MICPA)” [43, p. 125]. Samsuddin et al. [43] find that students’ awareness, motivation, and readiness influence them to enroll in professional accounting education programs.

Accounting education focuses on improving students’ learning quality in the accounting discipline [44] and other professional competencies, such as teamwork, interpersonal skills, oral and written communication skills, computing knowledge and Excel, PowerPoint presentations, database access, online research skills, ethical awareness, problem-solving, and critical evaluation [43].

Studies have found that motives and readiness for higher education significantly impact students' academic performance in college [[44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]]. Byrne and Flood [44] explore the following factors that influence accounting students' learning quality: a) motives for higher education, b) rationale for studying accounting, and c) preparedness for continuing study and expectations. Their findings reveal that career and educational aspirations are the primary reasons for pursuing higher education. A combination of intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientations directs students' decisions to study accounting. Parents and teachers may also influence students’ higher education decisions. Many accounting students feel that prior learning has prepared them for learning tasks in their accounting programs and are confident about in-class discussions, completion of work, written assignments, their study responsibilities, and assessment of their progress. However, few students comprehend academic expectations and the need to work within teams [44].

Byrne et al. [46] compare the motivations, expectations, and preparedness of accounting students in Ireland, the U.K., Spain, and Greece to identify opportunities to align their processes. Students' motives for higher education are strongly associated with their expectations of the outcomes of higher education, which are formed by their previous educational experiences, academic perception of themselves, and promotional information. Accounting students’ perception of their preparedness for higher education significantly influences their transition to studying abroad.

Manganaris and Spathis [49] investigate Greek students' insights into an introductory accounting course and the accounting profession. They determine whether students' first-semester accounting studies correlate with their interest in accounting. The results demonstrate that students’ perceptions of the accounting profession are more positive after completing an introductory accounting course during their first semester. When students have a more favorable view towards accounting, they are more likely to stay with the program and graduate.

Arquero et al. [45] examine the relationship of motives, expectations, and preparedness for accounting education with academic performance in the first financial accounting module. Many students underestimate the effort required for academic success. Motives for accounting higher education, including intrinsic and extrinsic aspects that influence students' option to study accounting at a university, can impact students’ academic success. High school (or equivalent) preparation can provide a good foundation for learning abilities in universities [45,47,48].

The success of students in advanced accounting coursework is impacted by their previous accounting knowledge [43,44,46,[50], [51], [52]]. Previous accounting education experiences of accounting students affect their preparedness for more independent learning settings, because when they are optimistic about their previous accounting knowledge, they feel more confident about further collegiate learning. Moreover, they study independently, take responsibility for their studies, and effectively manage or plan their work. Accounting students are expected to improve their skills and competencies as they progress through accounting programs [43].

Byrne and Flood [24] further indicate that previous accounting knowledge has a significant relationship with academic success. They examine the associations between different background variables and accounting students' academic performance. The background variables include previous academic achievement, previous accounting knowledge, motives, expectations, and preparedness for higher education. Academic performance has three measures: overall academic performance, financial accounting performance, and management accounting performance. The findings suggest that previous academic achievement and accounting knowledge has a significant relationship with accounting students' academic performance. Previous academic achievement is the most vital variable in determining accounting students’ academic performance and is significantly associated with overall academic performance, financial accounting performance, and management accounting for students from non-English-speaking countries [27].

Transnational education programs in China use curriculum, including textbooks, that are developed in other countries with minimal alterations [9]. Thus, Chinese students have difficulty understanding accounting theories in the context of other countries. Their English proficiency is sufficient to learn some subjects, including finance, accounting information systems, management accounting, and statistical analysis. They have difficulty learning theoretical and regulatory content, which could be because of a lack of understanding of the local context and influence. Subject relevance and the lack of different experiences, standpoints, and frameworks of knowledge can lead to learning problems [9]. Studies indicate that international students’ previous accounting knowledge is vital for their academic success.

To address these issues, international accounting majors can enroll in classes taught by American or native English-speaking professors to improve their accounting terminology, education system, and cultural understanding in the United States [28]. International students can also benefit from online accounting education, which can provide long-term benefits to universities or colleges that offer international business programs to students from different countries [53]. Bridge courses that provide prior accounting knowledge are another option for students to ensure academic success at the university [47]. However, there is limited research on accounting students’ preparedness before studying abroad at transnational cooperative universities in China [43].

This study contributes to the current literature in two ways. First, it determines whether English language proficiency and accounting knowledge correlate with accounting students’ academic performance. Second, it examines transnational education programs in China as there is limited research in this field.

1.4. Research questions and hypotheses

Research Question 1

Is English language proficiency correlated with accounting students' academic performance in transnational education programs?

Research Question 2

Is preparedness for accounting knowledge correlated with accounting students' academic performance in transnational education programs?

1.5. Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1a

: There is no statistically significant correlation between English language proficiency and accounting students’ academic performance in transnational education programs.

Hypothesis 1b

: There is a statistically significant correlation between English language proficiency and accounting students’ academic performance in transnational education programs.

Hypothesis 2a

There is no statistically significant correlation between preparedness for accounting knowledge and accounting students' academic performance in transnational education programs.

Hypothesis 2b

There is a statistically significant correlation between preparedness for accounting knowledge and accounting students' academic performance in transnational education programs.

2. Methodology

This study employs a quantitative design. It consists of accounting students in a transnational education program in Jiangsu, China. It is assumed that the population has English language proficiency and accounting knowledge before studying abroad. According to official records from the Ministry of Education of China, there are 100 transnational educational programs or universities in Jiangsu [54]. The sample in this research comprises 104 accounting students enrolled in a transnational education program at a university in Jiangsu. The university has partnerships with a Canadian College and a university in Midwestern United States. The transnational education program has an accounting course. Accounting majors in their sophomore, junior, and senior years can attend either the school in Canada or the United States. Accounting students who have finished two years of study in China can choose the partner college in Canada and earn a Canadian diploma. After three years of study in China, students who attend the partner university in the United States can earn a U.S. bachelor's degree. Only seniors are selected to participate in this program because they have more time to prepare before going abroad. Currently, there are four classes for senior students majoring in accounting.

To ensure academic success in study abroad programs, students need to prepare and consider relevant factors, including English language proficiency and accounting foundations, before going overseas [55]. The English seminar course scores are used to measure students' English language proficiency. Students typically do not take the TOEFL in the transnational education program; to obtain the degree they must pass English exams designed by the partner university in Canada. The organization only records pass or fail, with no specific scores for English exams. Hence, the researchers choose the English seminar course score to measure the students’ English language proficiency. The English seminar course is the highest English level course and the last course that accounting students take in the first semester of their junior year.

The Canadian partner college has designed the English seminar course in the transnational cooperative program to measure accounting students' language proficiency. Accounting students need to take nine English courses, including the following four courses where English is used as the primary language: a) English for Academic Purposes, b) Business English Skills I, c) Business English Skills II, and d) English Seminar. English seminar is the highest level and last course that senior accounting students take in the first semester of their junior year. The English seminar course is intended to develop students’ reading, writing, speaking, critical thinking, research, and presentation skills. Students discuss and write about the selected topics in the course as well as learn and analyze the cultural differences between China, Canada, and the United States [56].

Accounting students take an accounting principles course titled Accounting Theory and Practice I in the second semester of their freshman year. The scores of this course are used to measure students’ previous accounting knowledge. The course introduces students to the fundamentals of accounting theory and standard record-keeping methods. Manufacturing, services, and merchandising companies prepare financial statements based on accounting principles and concepts. The topics discussed in the course include internal control procedures for cash, receivables, inventory, and payroll. This course is designed for accounting and business administration students [57].

Accounting students take an advanced financial accounting course titled Financial Accounting in the first semester of their senior year. It is considered the most advanced accounting course in college studies. Students’ scores in this course are used to measure their academic performance. The course includes topics on business consolidations, interim and segment reporting, foreign currency transactions, the translation of foreign currency financial statements, and governmental and not-for-profit accounting [58].

The research is affected by specific threats to internal validity. The threats recognized in this quantitative study include selection bias, history, maturation, and the Hawthorne effect to avoid behavioral changes in participants with the knowledge that they are participating in the research. Selection bias is mitigated by selecting all senior accounting students in a transnational education program. The study uses all available participants that the researchers could access. The study duration is limited to the spring semester of 2020, which runs from February–July 2020, to reduce the threat of history and maturation. Accounting students are not informed of this study to minimize the Hawthorne effect.

The study was approved by the ethics committee board at the university where the research was conducted. One of the researchers, an adjunct faculty member at the selected organization, contacted the academic administration office to obtain the data needed for the research. After signing a confidentiality agreement, the academic administration office released the students' records to the researcher. The researchers have no relationship with the faculty of the three courses and have signed an agreement to protect the confidentiality of the data. The transnational education program has also signed a cooperation agreement and provided permission to access the data. The protocols were followed in this study. The independent variables in this study are preparedness for English language proficiency (X1) and prior accounting knowledge (X2), while the dependent variable is academic performance (Y). The dataset for preparedness for English language proficiency (X1) is the English seminar test scores. Accounting principle scores are used to measure previous accounting knowledge (X2). Advanced financial accounting scores measure accounting students’ academic performance (Y). The Pearson correlation test is used to investigate the relationships among these three variables.

The Pearson r correlation coefficient ranges from −1.00 to +1.00, and this research follows the general guidelines for the interpretation of correlation coefficients by Cohen et al. [59]. A non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis implies that a Pearson coefficient may be either negative or positive. After calculating Pearson r, the researchers compared the r with the critical r in the correlation table. Assuming a type 1 error α = 0.05, if r ≥ critical r, the null hypothesis is rejected, and we are 95% confident that x and y are correlated. If r ≤ critical r, the null hypothesis is accepted, and we are not 95% confident that x and y are correlated. If the p-value <0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, and if the p-value >0.05, the null hypothesis is accepted.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics for the participants are as follows. We performed the Pearson correlation test for 105 raw scores of the English seminar course. A higher score was chosen for two students with two scores in the English seminar course because they were factored into the accounting students’ GPA calculations. One senior student who had no score in this English course was removed from the dataset. A total of 98 English seminar scores were used in the Pearson correlation test to evaluate the correlation between English language proficiency and academic performance. The English seminar scores ranged from 0 to 100. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of English seminar scores. The mean score was 81, and the minimum and maximum scores were 51 and 100, respectively. The median and mode scores were 82.5 and 94.0, respectively.

Table 1.

English seminar scores’ summary descriptive statistics.

|

English Seminar Scores' Descriptive Statistics |

Value |

|---|---|

| Mean | 80.62244898 |

| Standard Error | 1.142812527 |

| Median | 82.5 |

| Mode | 94 |

| Standard Deviation | 11.31326683 |

| Sample Variance | 127.9900063 |

| Kurtosis | −0.383017474 |

| Skewness | −0.576312803 |

| Range | 49 |

| Minimum | 51 |

| Maximum | 100 |

| Sum | 7901 |

| Count | 98 |

| Confidence Level (95.0%) | 2.26816652 |

3.1. Accounting principle scores

A total of 177 official accounting principle scores were obtained. Forty-seven participants took this course one to four times. For participants with 2–4 scores, the researchers used the highest scores for the GPA calculation. A total of 98 accounting principle scores were used in the Pearson correlation test to assess the relationship between previous accounting knowledge and academic success. The accounting principle scores ranged from 0 to 100. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of accounting principle scores. The minimum and maximum scores were 50 and 97, respectively, while the mean score was 70. The median and mode scores were 70 and 50, respectively.

Table 2.

Accounting principle scores’ summary descriptive statistics.

|

Accounting Principle Scores' Descriptive Statistics |

Value |

|---|---|

| Mean | 69.87755102 |

| Standard Error | 1.26153548 |

| Median | 70 |

| Mode | 50 |

| Standard Deviation | 12.48856409 |

| Sample Variance | 155.9642331 |

| Kurtosis | −0.903699708 |

| Skewness | 0.098659028 |

| Range | 47 |

| Minimum | 50 |

| Maximum | 97 |

| Sum | 6848 |

| Count | 98 |

| Confidence Level (95.0%) | 2.503798716 |

The advanced financial accounting course had 104 raw scores. Six senior accounting students had two scores in the course. Thus, the higher score was used in the Pearson test because the GPA calculation only needs the higher score. Six participants who had no scores were excluded from this study. A total of 98 advanced financial accounting scores were used to match the accounting principle scores and English seminar scores. The advanced financial accounting scores ranged from 0 to 100. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of advanced financial accounting scores. The mean score was 79; the minimum and maximum scores were 62 and 96, respectively. The median and mode scores were 79.5 and 80, respectively.

Table 3.

Advanced financial accounting scores’ summary descriptive statistics.

|

Advanced Financial Accounting Scores' Descriptive Statistics |

Value |

|---|---|

| Mean | 79.25510204 |

| Standard Error | 0.729774805 |

| Median | 79.5 |

| Mode | 80 |

| Standard Deviation | 7.224401983 |

| Sample Variance | 52.19198401 |

| Kurtosis | −0.254462717 |

| Skewness | 0.005384535 |

| Range | 34 |

| Minimum | 62 |

| Maximum | 96 |

| Sum | 7767 |

| Count | 98 |

| Confidence Level (95.0%) | 1.448400975 |

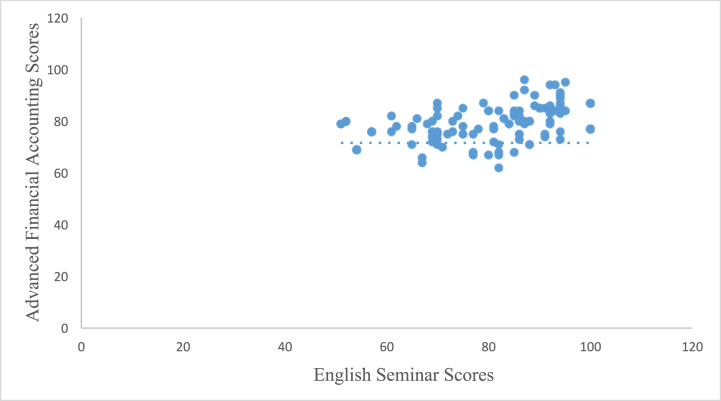

The researchers matched 98 English seminar scores with advanced financial accounting scores to perform a Pearson correlation test. The data analysis indicated a moderate positive correlation between the two variables. In this study, the degrees of freedom were df = N-2 = 98-2 = 96 [60]. Pearson r (df) = Pearson r (96) = 0.4029. P-value = 3.89802E-05, <0.05, indicating a statistically significant correlation between English language proficiency and academic performance. As English seminar scores increased, advanced financial accounting scores correspondingly increased. Table 4 shows a moderate positive correlation between English seminar scores and advanced financial accounting scores.

Table 4.

Correlation between English seminar scores and advanced financial accounting scores.

| English Seminar Scores | ||

|---|---|---|

| Accounting Score | Pearson r Correlation | 0.4029a |

| P-value | 3.89802E-05 | |

| N | 98 | |

Statistically Significant Correlation p < 0.05.

The scatter plot diagram in Fig. 2 shows the relationship between English seminar scores and advanced financial accounting scores. The trend line in the scatter plot shows a moderate positive correlation, which indicates that as English seminar scores increase, advanced financial accounting scores correspondingly rise. Hence, the first null hypothesis is rejected, and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. There is a statistically significant correlation between preparedness for English language proficiency and accounting students’ academic performance in transnational education programs.

Fig. 2.

English seminar/advanced financial accounting scores scatter plot.

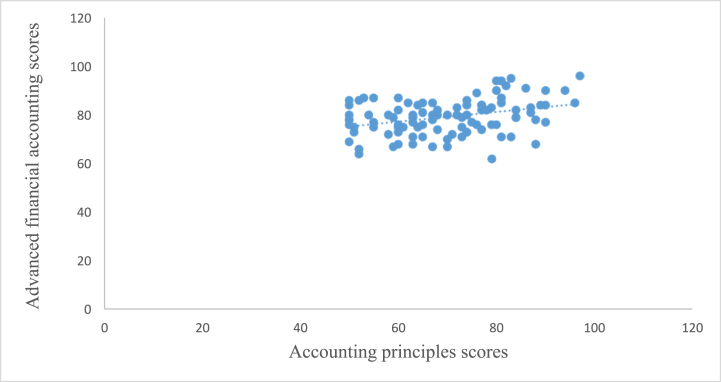

A total of 98 accounting principle scores were matched with advanced financial accounting scores to perform the Pearson correlation test. The results suggest a moderate positive correlation between these two variables. Pearson's r (df) = Pearson's r (96) = 0.3443. P-value = 0.00052, <0.05, which indicates a statistically significant correlation between accounting principle scores and advanced financial accounting scores. As accounting principle scores increased, advanced financial accounting scores subsequently increased. Table 5 shows a moderate positive correlation between accounting principle scores and advanced financial accounting scores.

Table 5.

Correlation between accounting principle scores and advanced financial accounting scores.

| Accounting Principle Scores | ||

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Financial Accounting Scores | Pearson r Correlation | 0.3443a |

| P-value | 0.00052 | |

| N | 98 | |

Note. The timeframe of the study was from February 2020 to July 2020 (spring semester, 2020).

Statistically Significant Correlation p < 0.05.

The scatter plot diagram in Fig. 3 shows the relationship between accounting principle scores and advanced financial accounting scores. The trend line in the scatter plot shows a moderate positive correlation between these two variables. It illustrates that as accounting principle scores increase, advanced financial accounting scores correspondingly increase. Therefore, the second null hypothesis is rejected, and the second alternative hypothesis is accepted. There is a statistically significant correlation between preparedness for accounting knowledge and accounting students’ academic performance in transnational education programs.

Fig. 3.

Accounting principles scores/advanced financial accounting scores scatter plot.

4. Discussion

This study confirms the first alternative hypothesis, which demonstrates a statistically significant correlation between English language proficiency and accounting students’ academic performance in transnational education programs. The results reveal a moderate positive correlation between accounting principles scores and advanced financial accounting scores. This indicates that, as the English seminar scores increase, the advanced financial accounting scores also increase. This correlation is probably rooted in the fact that the organization selected for this study uses English as the primary language to teach accounting-related courses. These results are consistent with those of Ghenghesh [36] and Martirosyan et al. [37]. Ghenghesh [36] have found a significant positive relationship between English language proficiency and the academic success of international students majoring in engineering, informatics, computer science, economics, political science, and business administration. This is because English is the primary language of instruction and students must have an appropriate level of English proficiency before entering university. Martirosyan et al. [37] have also found a significantly positive relationship between English language proficiency and the academic performance of international students at a university in the United States. Students who have mastered more than one foreign language and overcome language barriers are more likely to achieve academic success. Similarly, several studies have emphasized that English language proficiency can affect the academic performance of international students. International students often focus on English reading and grammar [25]. However, they may face difficulties in communication and writing skills, which reduces their confidence in class and hampers the learning results [5,28]. Therefore, students should overcome poor English language proficiency through various learning methods and effectively adapt to the English academic environment [27,31].

This study also supports the second alternative hypothesis that suggests a significant relationship between preparedness for accounting knowledge and the academic performance of accounting students in transnational education programs. The results show a moderately positive correlation between accounting principles and advanced financial accounting scores. This indicates that, as the accounting principles scores increase, the advanced financial accounting scores also increase. This is because having accounting readiness contributes to academic success. Similarly, several studies have indicated that higher education readiness can significantly impact students' academic success in universities [[47], [48], [49]]. Arquero et al. [45] have demonstrated that motives can impact students' academic performance. High school or equivalent preparedness can provide a foundation for developing learning abilities in university [47,48]. Previous learning experience can instill confidence in students for in-class discussions and written essays [44]. When students have a positive attitude toward accounting, they are more likely to persist in completing the accounting program [49]. Accounting students' perception of readiness influences their enrollment in professional accounting education programs [43] and significantly impacts the transition to studying overseas [46]. Some studies have reported that previous accounting knowledge can impact students' academic success [[50], [51], [52]]. Previous accounting education experiences can affect students’ preparedness for developing more independent learning skills and competencies [43]. These research results are consistent with previous research conducted by Byrne and Flood [24] and Robertson et al. [27]. It has been found that previous accounting knowledge and academic achievement have significant relationships with academic performance. Previous academic achievement is significantly associated with the overall academic performance of international students.

5. Conclusion

International accounting students studying abroad may face challenges with their English language proficiency or accounting knowledge. Transnational education programs are vital in providing students with foundational accounting knowledge and improving their English language skills. This study examined the correlation between English language proficiency and academic success, and between prior accounting knowledge and academic performance in a transnational education program in China. The findings suggest that there are significant relationships between English language proficiency and academic performance, as well as between prior accounting knowledge and academic success. Additionally, there are positive correlations between English language proficiency and later academic success, and between previous accounting knowledge and academic performance.

5.1. Practical implications

This study has practical implications for transnational education programs, academic communities, and agencies that assist students in finding schools. The positive correlations identified in this study offer guidance for transnational education programs. They should consider hiring more international English instructors, increasing English coursework, and supporting curriculum development and policies that enhance the rigor of accounting foundation coursework. Accounting students should prioritize developing their English language skills and building a solid accounting foundation before going abroad. Accounting and business faculty should use English textbooks, teach in English, and emphasize the importance of foundational accounting knowledge. Additionally, students, parents, and college selection agencies should consider high-quality transnational education programs that can help students hone their English skills and develop accounting knowledge before going abroad. Lastly, academic evaluators should use English language proficiency and accounting knowledge as criteria for assessing the quality of transnational education programs.

5.2. Future research and limitations

This study provides a framework for future research. Future research should focus on these constructs among students majoring in non-accounting business or non-business majors. Confounding variables such as teaching methods, student effort, student motivation, faculty engagement, student engagement, student intelligence quotient (IQ), household income or parents' wealth, first-generation college student status, access to English tutoring, class attendance, and grade inflation should be investigated. Future research should examine accounting students’ preparedness for transnational education programs in countries other than Canada and the United States. Moreover, little is known about the impact of different types of transnational education programs (i.e., franchised, distance/online education, MOOCs, and international branch locations) on student success.

This study has some limitations. First, it only involves partnership programs; thus, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Second, the study only examines transnational education programs in China; hence, the results may not apply to transnational education programs in other countries with different learning/teaching approaches. Lastly, the study relies on correlation tests with two variables and does not predict causality. Positive correlations among English language proficiency, previous accounting knowledge, and academic performance do not prove that a high level of English proficiency and a solid prior accounting foundation lead to academic success. However, the correlation test is sufficient for this study.

Author contribution statement

Hui Wang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Jennifer Lynn Schultz: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ziyuan Huang: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Wilkins S., Juusola K. The benefits & drawbacks of transnational higher education: myths and realities. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2018;60(2):68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knight J. Transnational education remodeled: towards a common TNE framework and definitions. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2016;20:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamene E., Lou S., Wan X. International student mobility (ISM) in China in the new phase of internationalization of higher education (IHE): trends and patterns. J. Educ. Pract. 2017;8(30) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of International Education . 2023. Open Doors Report. IIE.Org. IIE Open Doors/International Students (opendoorsdata.Org) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J.J. International students' experiences and attitudes at a US host institution: self- reports and future recommendations. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2010;9(1):66–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel C., Millanta B., Tweedie D. Is international accounting education delivering pedagogical value? Account. Educ. 2016;25(3):223–238. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudaha R. A third wave of international student mobility: global competitiveness and American higher education. Research & Occasional Paper Series: CSHE.8.18. Center for Studies in Higher Education; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findlay R.S.M., Findlay R. 2017. International Student Transitions in Higher Education: Chinese Students Studying on a Professionally Accredited Undergraduate Accounting Degree Programme at a Scottish University (Doctoral Dissertation, Edinburgh Napier University) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H. Western concepts, Chinese context: a note on teaching accounting offshore. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning. 2012;7(1):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK HE International Unit . International Unit; London: UK HE: 2016. International Higher Education in Facts and Figures. June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoof Van, B H., Verbeeten M.J. Wine is for drinking, water is for washing: student opinions about international exchange programs. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2005;9(1):42–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) International students in Canada. 2018. https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/International- Retrieved from. (Students-in-Canada-ENG.pdf)

- 13.Ge Y. Internationalisation of higher education: new players in a changing scene. Educ. Res. Eval. 2022;27(3–4):229–238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Textor C. Number of Chinese students in the U.S. 2011/12–2021/22. Statista. 2023 https://www.statista.com/statistics/372900/number-of-chinese-students-that-study- Retrieved from. (in-the-us/) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill C. International business: competing in the global marketplace. Strat. Dir. 2008;24(9) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helliar C. The global challenge for accounting education. Account. Educ. 2013;22(6):510–521. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby J.R., Woodhouse R.A., Ma Y. Studying in a second language: the experience of Chinese students in Canada. The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological, and Contextual Influences. 1996:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeoh J.S.W., Terry D.R. International research students' experiences in academic success. Universal Journal of Educational Research. 2013;1(3):275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Mi Y. Another look at the language difficulties of international students. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2010;14(4):371. 38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman M.E. Phobias and preparedness. Behav. Ther. 1971;2(3):307–320. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser B.J., Walberg H.J., Welch W.W., Hattie J.A. Syntheses of educational productivity research. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1987;11(2):147–252. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne M., Flood B. Examining the relationships among background variables and academic performance of first year accounting students at an Irish University. J. Account. Educ. 2008;26(4):202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawir E. Language difficulties of international students in Australia: the effects of prior learning experience. Int. Educ. J. 2005;6(5):567–580. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H., Li B., Fleisher B.M. 2015. Language Skills Are Critical for Workers' Human Capital Transferability Among Labor Markets. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson M., Line M., Jones S., Thomas S. International students, learning environments and perceptions: a case study using the Delphi technique. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2000;19(1):89–102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo Y.H. Language challenges faced by international graduate students in the United States. J. Int. Stud. 2011;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yafei K.A., Ayoubi R.M., Crawford M. The student experiences of teaching and learning in transnational higher education: a phenomenographic study from a British-Qatari partnership. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2022;27(3):408–426. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van der Rijst R.M., Lamers A.M., Admiraal W.F. Addressing student challenges in transnational education in Oman: the importance of student interaction with teaching staff and Peers. Compare. 2022:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brutt-Griffler J., Nurunnabi M., Kim S. International Saudi arabia students' level of preparedness: identifying factors and maximizing study abroad experience using a mixed-methods approach. J. Int. Stud. 2020;10(4):976–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai H., Wang M., Yang Y. Teaching accounting in English in higher education—does the language matter? Engl. Lang. Teach. 2018;11(3):50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krausz J., Schiff A., Schiff J., Hise J.V. The impact of TOEFL scores on placement and performance of international students in the initial graduate accounting class. Account. Educ. 2005;14(1):103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syafinaz N., Ahmad M., Iskandar S., Idris Z.S., Fadhilah R., Ghani E.K. Factors influencing accounting students under-performance: a case study in a Malaysian public university. Int. J. Educ. 2019;7(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong D.S., Chia Y.M. English language, mathematics and first-year financial accounting performance: a research note. Account. Educ. 1996;5(2):183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghenghesh P. The relationship between English language proficiency and academic performance of university students–should academic institutions really be concerned? Int. J. Appl. Ling. Engl. Lit. 2015;4(2):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martirosyan N.M., Hwang E., Wanjohi R. Impact of English proficiency on academic performance of international students. J. Int. Stud. 2015;5(1):60–71. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le T., Tran T., Nguyen T., Dao N., Ngo N., Nguyen N. Determining factors impacting the application of IFRS in teaching: evidence from Vietnam. Accounting. 2022;8(3):323–334. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucianelli G., Citro F. Accounting education for professional accountants: evidence from Italy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018;13(8):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vysotskaya A., Senyigit Y.B. Practical issues in education and adoption of IFRS: evidence from Russia. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics. 2021;14(28):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Needles B. International education standards (IES): issues of implementation. Accounting Education London. 2008;17(Suppl.):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezaee Z., Szendi J.Z., Elmore R.C. International accounting education: insights from academicians and practitioners. Int. J. Account. 1997;32(1):99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samsuddin M.E., Khairani N.S., Wahid E.A., Sata F.H.A. Awareness, motivations and readiness for professional accounting education: a case of accounting students in UiTM Johor. Procedia Econ. Finance. 2015;31:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byrne M., Flood B. A study of accounting students' motives, expectations and preparedness for higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2005;29(2):109–124. doi: 10.1080/03098770500103176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arquero J.L., Byrne M., Flood B., González J.M. Motives, expectations, preparedness and academic performance: a study of students of accounting at a Spanish university. Rev. Contab. - Spanish Accounting Rev. 2009;2:279. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrne M., Flood B., Hassall T., Joyce J., Montaño Arquero, L J., González J.M., Tourna-Germanou E. Motivations, expectations and preparedness for higher education: a study of accounting students in Ireland, the UK, Spain and Greece. Account. Forum. 2012;36(2):134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joynt C. How to assess the effectiveness of accounting education interventions: evidence from the assessment of a bridging course before introductory accounting. Meditari Account. Res. 2022;30(7):237–255. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papageorgiou E., Carpenter R. Prior accounting knowledge of first-year students at two South African universities: contributing factor to academic performance or not? S. Afr. J. High Educ. 2019;33(6):249–264. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manganaris P., Spathis C. Greek students' perceptions of an introductory accounting course and the accounting profession. Adv. Account. Educ.: Teaching and Curriculum Innovations. 2012;13:59–85. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gul F.A., Fong Cheong, C S. Predicting success for introductory accounting students: some further Hong Kong evidence. Account. Educ. 1993;2(1):33. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papageorgiou E. Lecture attendance versus academic performance and prior knowledge of accounting students: an exploratory study at a South African university. S. Afr. J. High Educ. 2019;33(1):262–282. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rohde F.H., Kavanagh M. Performance in first year university accounting: quantifying the advantage of secondary school accounting. Account. Finance. 1996;36(2):275–285. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pimpa N. E-Business Education: a phenomenographic study of online Engagement among accounting, finance and international business students. iBusiness. 2010;2(4):311. [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Ministry of education of China (n.d.) Chinese-foreign cooperation in running schools. http://www.crs.jsj.edu.cn//aproval/orglists/2 Retrieved from.

- 55.Abhayawansa S., Fonseca L. Conceptions of learning and approaches to learning-a phenomenographic study of a group of overseas accounting students from Sri Lanka. Account. Educ. 2010;19(5):527–550. [Google Scholar]

- 56.English Seminar Syllabus, Collected from the Administrator from the Selected University.

- 57.Accounting Theory and Practice I Syllabus, Collected from the Administrator from the Selected University.

- 58.Advanced Accounting Syllabus, Collected from the Administrator from the Selected University.

- 59.Cohen L., Manion L., Morrison K. sixth ed. Routledge; 2007. Research Methods in Education. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinberg W.J. second ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2010. Statistics Alive! [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.